Abstract

Background & Aims

The loss of parietal cells from the fundic mucosa leads to the emergence of metaplastic lineages associated with an increased susceptibility to neoplastic transformation. Both intestinal metaplasia (IM) and spasmolytic polypeptide (TFF2/SP) expressing metaplasia (SPEM) have been identified in human stomach, but only SPEM is present in most mouse models of gastric metaplasia. We previously determined that loss of amphiregulin (AR) promotes SPEM induced by acute oxyntic atrophy. We have now examined whether SPEM in the AR−/− mouse predisposes the stomach to gastric neoplasia.

Methods

Gross pathology of 18-month-old wild-type, AR−/−, and TGF-α −/− mice were examined. Ki-67, β-catenin, Pdx-1, TFF3, and TFF2/SP expression was analyzed by immunohistochemistry. Metaplastic gastric mucosa was analyzed by dual immunostaining for TFF2/SP with MUC2 or TFF3.

Results

By 18 months of age, more than 70% of AR−/− mice developed SPEM while 42% showed goblet cell IM labeled with MUC2, TFF3, and Pdx-1. A total of 28% had invasive gastric lesions in the fundus. No antral abnormalities were observed in AR−/− mice. Metaplastic cell lineages in AR−/− mice showed increases in cell proliferation and cytosolic β-catenin expression. Dual staining for TFF2/SP with MUC2 or TFF3 showed glands containing both SPEM and IM with intervening cells expressing both TFF2/SP and MUC2 or TFF2/SP and TFF3.

Conclusions

AR−/− mice develop SPEM, which gives rise to goblet cell IM and invasive fundic dysplastic lesions. The AR−/− mouse represents the first mouse model for spontaneous development of fundic SPEM with progression to IM.

The gastric epithelium is geographically heterogeneous, containing functionally distinct pyloric and fundic mucosal lineages. The normal fundic mucosa is assembled from a diverse group of cell lineages responsible for luminal secretion of mucins, intrinsic factor, acid, and pepsinogen. While pyloric mucosal lineages, similar to intestinal mucosal units, arise from basally located proliferative zones, lineages in the fundic mucosa arise from a progenitor zone located in the luminal third of the glands.1 Surface cells migrate toward the lumen. A small number of differentiating parietal cells migrate toward the lumen in the mouse, whereas most parietal cells progress toward the base of the gland.2 In humans, the loss of parietal cells is a prerequisite step for the development of intestinal-type gastric cancer.3 Active chronic gastritis, most often caused by Helicobacter pylori infection, progresses to multifocal atrophic gastritis with loss of parietal cells and chief cells and the appearance of metaplastic lineages that are predisposed to neoplastic transformation. Thus, oxyntic atrophy, the loss of parietal cells, represents the critical alteration of the gastric mucosal most associated with gastric preneoplasia.

The loss of parietal cells leads to the development of 2 identifiable metaplasias associated with gastric cancer: intestinal metaplasia (IM) and spasmolytic polypeptide-expressing metaplasia (SPEM). Goblet cell IM has received the most consideration as the most prominent candidate for origination of gastric cancer.4,5 The presence of cells with goblet cell morphology in the stomach represents a clear example of a metaplastic process with intestinal phenotype cells expressing MUC2 and trefoil family factor (TFF) 3.6 – 8 A second gastric metaplasia, designated SPEM,9,10 is characterized by the presence of TFF2 (or spasmolytic polypeptide) immunoreactive cells in the base of gastric fundus, showing oxyntic atrophy with morphologic characteristics similar to those of deep antral gland cells or Brunner’s gland cells.8 Thus, while IM expresses MUC2 and TFF3, MUC6 and TFF2 are useful markers for SPEM.11,12 Both of these metaplasias have been associated with the development of gastric cancer in humans,5,13 but there remains a lack of direct evidence linking specific gastric metaplasias with the neoplastic process. In addition, the relationship between SPEM and IM remains obscure.

Epidermal growth factor (EGF) receptor ligands are critical regulators of epithelial cell differentiation. Parietal cells secrete a number of EGF receptor ligands, including transforming growth factor (TGF)-α, amphiregulin (AR), and heparin-binding EGF.14 –17 In addition, surface mucous cells and enterochromaffin-like cells are also a source of at least TGF-α.18 Previous studies have documented the influence of EGF receptor ligands on the differentiation of gastric cell lineages. While loss of TGF-α expression has little effect on gastric lineages, overexpression of TGF-α in surface mucous cells leads to foveolar hyperplasia and loss of glandular lineages and is responsible for the pathological phenotype of Ménétrier’s disease in humans.19 Previous investigations have also shown that AR levels are elevated in the stomachs of insulin-gastrin mice infected with Helicobacter felis20 or following hypoxia/reoxygenation in gastric cells in culture.21 Recently, we elucidated evidence for a definitive role for parietal cell– derived peptides in regulating SPEM lineage development.22 We showed in 8-week-old mice that, while TGF-α– deficient mice developed SPEM along a similar time course as wild-type (WT) mice, AR-deficient mice developed SPEM at an accelerated rate in response to acute oxyntic atrophy. In addition to a more accelerated development of SPEM, AR-deficient mice also showed a greater expansion of SPEM. We have now sought to determine whether SPEM in the AR-deficient mouse predisposes the stomach to gastric neoplasia. The current results show that AR-null mice develop oxyntic atrophy and SPEM spontaneously by 10 months of age. By 18 months of age, SPEM in turn gives rise to goblet cell IM and invasive fundic mucosal lesions. Thus, the AR-null mouse model represents the first mouse model for spontaneous development of fundic SPEM with progression to IM and neoplasia.

Materials and Methods

Animals

The generation of AR-null mice, heterozygous AR+/− mice, and TGF-α–null mice has been described previously in detail.22 Mice were maintained on the C57BL/6 background under specific pathogen-free conditions in individual, sterile microisolator cages in non-barrier mouse rooms. C57BL/6 mice were obtained from Jackson Laboratories (Bar Harbor, ME). During the experiments, the mice were maintained with regular mouse chow and water ad libitum in a temperature-controlled room under a 12-hour light/dark cycle. The care, maintenance, and treatment of animals in these studies followed protocols approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of Vanderbilt University.

Study Design

Mice were divided into 4 groups: AR deficient (AR−/−, n = 17), AR heterozygous (AR+/−, n = 14), TGF-α deficient (TGF-α−/−, n = 21), and WT (n = 16). Each group of mice was examined at 10 months (AR−/−, n = 10; AR+/−, n = 6; TGF-α −/−, n = 13; WT, n = 10) and 18 months (AR−/−, n = 7; AR+/−, n = 8; TGF-α −/−, n = 8; WT, n = 6) of age without any treatment. Immediately after the mice were killed, their stomachs were opened along the greater curvature. One half of the glandular stomach was fixed for histologic examination, and the other half was homogenized in sterile phosphate-buffered saline, plated on selective blood agar plates, and incubated for 5–7 days for Helicobacter sp. culture to test for infection. The excised stomachs were fixed in neutral buffered 10% formalin and cut into approximately 6 strips, processed by standard methods, embedded in paraffin, and sectioned at 5 μm.

Details of methods for staining tissue sections and serum and tissue cytokine expression assays are described in the Supplementary Methods.

Results

Spontaneous Tumors Develop in the Gastric Fundus, But Not in the Antrum, of AR−/− Mice

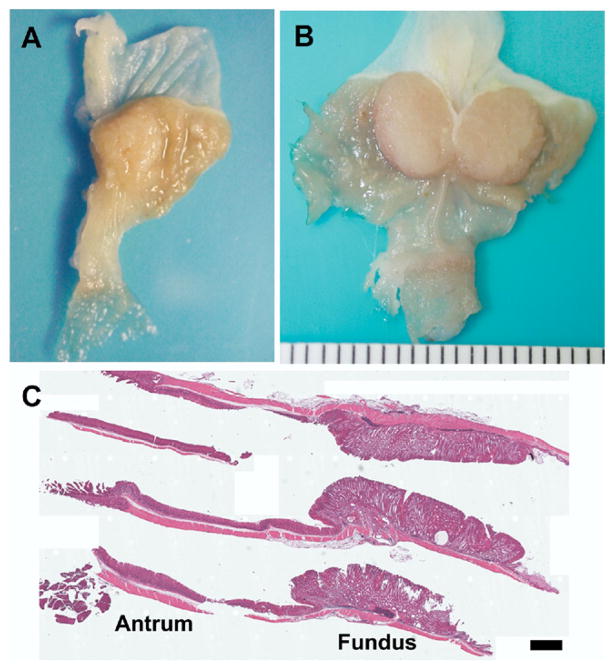

We recently found that AR deficiency caused more extensive induction of SPEM in response to acute oxyntic atrophy, suggesting differential roles of respective EGF ligand in cell lineage differentiation in the gastric unit.22 To evaluate the long-term effects of AR deficiency, we systemically evaluated the stomachs of AR−/− mice at 10 and 18 months of age compared with age-matched WT mice. To examine the long-term effects of other EGR ligands produced by parietal cells, TGF-α – deficient mice were also evaluated at 10 and 18 months of age. Examination of AR−/− mouse stomachs at 10 months of age revealed the presence of macroscopically visible tumors in 3 out of the 10 mice examined (Figure 1A), while stomachs from all AR+/−, TGF-α −/−, and WT mice exhibited normal gastric morphology. All 3 of the tumors observed were in the fundic region of the AR−/− mouse stomach. Notably, in 18-month-old AR−/− mice, we observed large macroscopically visible tumors in 5 (71%) of the 7 mice examined (Figure 1B), while stomachs from all AR+/−, TGF-α −/−, and WT mice exhibited normal gastric morphology. All 5 of the tumors observed were in the fundic region of the AR−/− mouse stomach. In contrast to the fundic area, the antral mucosa in AR−/− mice maintained a normal appearance even at the demarcation between the fundus and antrum (Figure 1B). Histologic examination of the stomach showed a vastly expanded fundic mucosa in the 18-month-old AR−/− mice. However, histologic examination of the antrum revealed a normal mucosal morphology (Figure 1C).

Figure 1.

AR-deficient mice develop gross fundic tumors. Gross appearance of (A) a 10-month-old AR-deficient mouse stomach and (B) an 18-month-old AR-deficient mouse stomach. (A) The 10-month-old mice showed visible nodules arising in the fundic area, while (B) 18-month-old mice showed grossly visible tumors in the fundic area. (C) H&E staining of the stomach of an 18-month-old AR-deficient mouse. Note the vastly expanded fundic mucosa (Fundus) in contrast to the normal antral (Antrum) morphology in the histologic sections of the stomach. Bar = 1 mm.

Fundic Mucosa in AR−/− Mice Was Expanded by Development of SPEM

To evaluate further the characteristics of the expanded fundic area in AR−/− mice, we examined the metaplastic and hyperplastic response in the fundic mucosa of these mice. The fundic mucosa in AR−/− mice demonstrated marked expansion of metaplastic glands. Morphologically, the expanded fundic mucosa in AR−/− mice showed extensive replacement of the oxyntic glands by elongated columnar epithelial cells, often with mixed mucin expression (Figure 2C and E). The metaplastic glands of the fundic mucosa were hyperplastic and contained Alcian blue–positive glands abnormally invading into the muscularis mucosa with prominent cystic structures within the submucosa of the gastric wall (Figure 2C and D). To identify parietal cells, we immunostained AR−/− stomach sections with antibodies against the α-subunit of the H+/K+–adenosine triphosphatase. In the expanded fundic region, the number of parietal cells was markedly decreased. The few remaining parietal cells appeared atrophic and were scattered through the glands (Figure 2E). To identify columnar metaplastic cells in the AR−/− mouse fundic mucosa, we immunostained gastric tissue with antibodies against TFF2/SP. The elongated fundic metaplastic mucosal glands were dominated by intensely stained TFF2/SP-expressing cells (Figure 2F). This staining pattern was similar to that previously described for TFF2/SP staining in SPEM cells.22,23

Figure 2.

Characterization of expanded fundic glands in 18-month-old AR-deficient mice. (A and B) Histologic sections of normal fundus stained with either (A) H&E or (B) periodic acid–Schiff/Alcian blue. (C–F) Histologic sections of fundus from an 18-month-old AR-deficient mouse stained with (C) H&E, (D) periodic acid–Schiff/Alcian blue, (E) anti–H/K-adenosine triphosphatase, or (F) anti-TFF2. AR-deficient mice showed extensive replacement of the normal gland cell lineages by columnar mucous cells that were both periodic acid–Schiff and Alcian blue positive. Note the invasion of the metaplastic glands into muscle layer with cystically dilated glands (arrows in C). (E and F) Staining in serial sections of fundic gland region outlined in the white box in C showed severe loss of parietal cells (E) and replacement of virtually the entire mucosal gland length with intensely staining TFF2/SP-expressing cells. Bar = 100 μm.

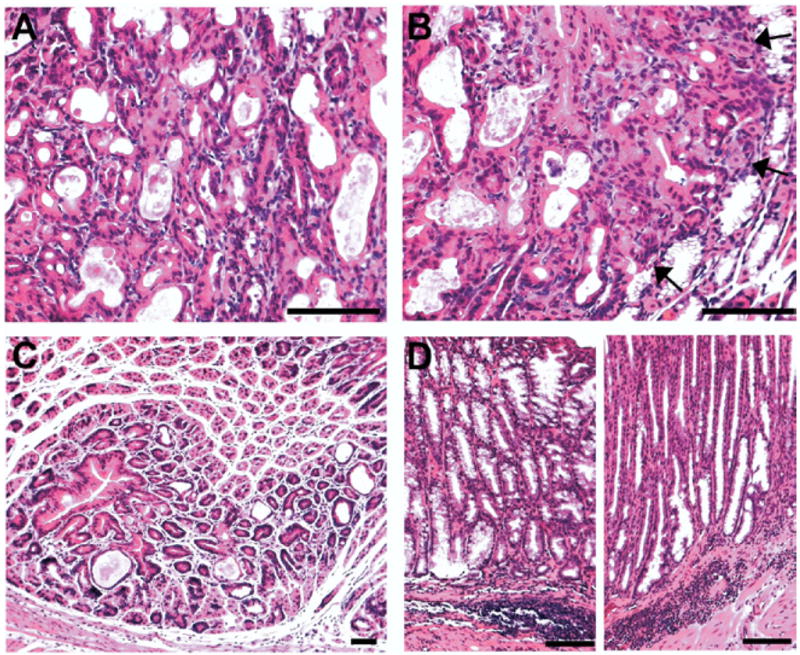

Characteristics of Invasive Fundic Mucosal Lesions in AR−/− Mice

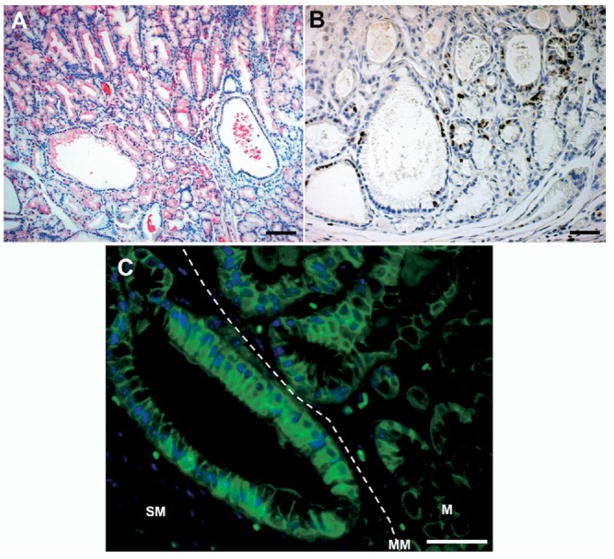

To investigate the characteristics of the submucosal invasive fundic lesions, we immunostained gastric tissue for markers associated with neoplastic transformation with antibodies against Ki-67 and β-catenin. TFF2/SP-positive metaplastic glands were present in the invasive fundic gland area in AR−/− mice (Figure 3A). In cells at the bases of the fundic glands, including cystically dilated glands, we detected proliferating cells by Ki-67 staining (Figure 3B). To define the possible activation of the Wnt signaling pathway in the region of submucosal gland invasion, we determined the subcellular localization of β-catenin by immunohistochemical staining. Membrane-localized β-catenin was detected in cells within the gland mucosal area (M), but we observed numerous cells containing cytoplasmic staining with some cells also showing nuclear β-catenin in invading submucosal glands, oriented perpendicular to the muscularis mucosa (MM) (Figure 3C).

Figure 3.

Characteristics of invasive fundic glands in 18-month-old AR-deficient mice. To characterize the invasive regions of the metaplastic mucosa, sections were stained for (A) TFF2/SP, (B) Ki-67, and (C) β-catenin. (A) TFF2/SP-positive glands also were present in the invasive fundic gland area. (B) Note the Ki-67–positive cells in the invasive area, especially in cystic lesions. (C) Membrane localized β-catenin was detected in the glands within the mucosal area (M), but note the number of cells containing cytoplasmic β-catenin in submucosal (SM) invasive glands deep to the muscularis mucosa (MM). Bar = 50 μm.

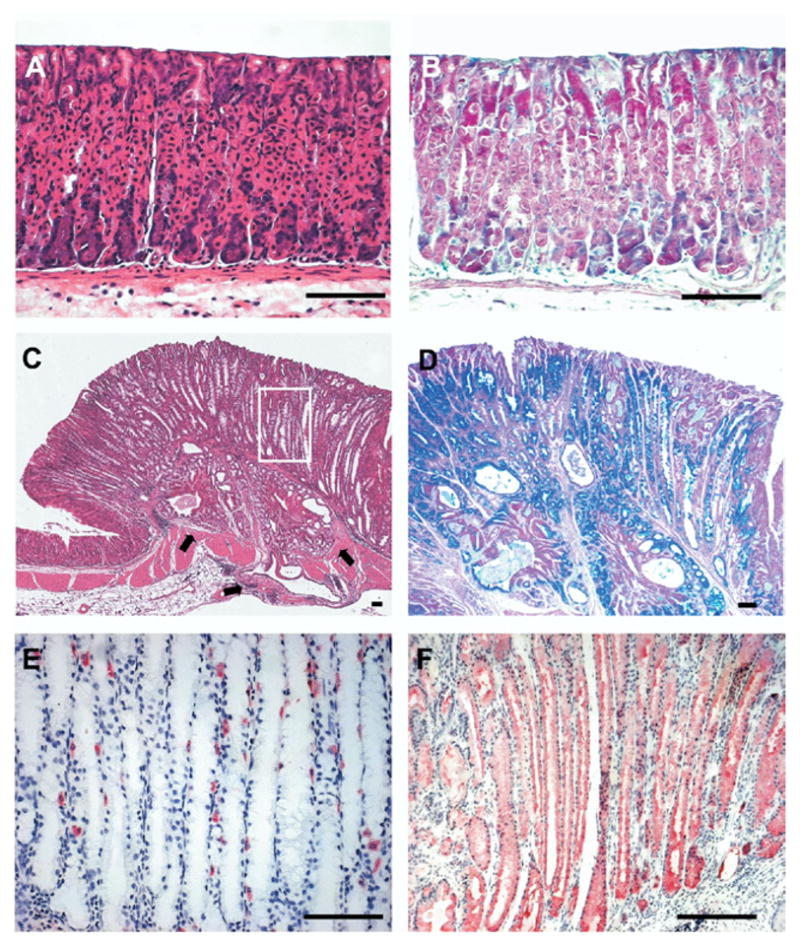

To analyze the characteristics of the fundic area in AR−/− mice, morphologic changes were examined at different ages by a pathologist (Table 1). Figure 4 summarizes representative criteria for the pathologic findings present in the AR−/− mice showing dysplasia, fundic hyperplasia, SPEM, and persistent submucosal inflammatory cell infiltration. Dysplasia was defined as dissociation of normal mucosal architecture and the presence of epithelial cells that display hyperchromatic nuclei, pleomorphic atypical shape, and a disorganized appearance (Figure 4A). In another area of fundic tumor, we observed expanding dysplasia invading into surrounding SPEM (Figure 4B). Fundic hyperplasia was characterized by a polypoid growth pattern of foveolar cells and irregular small compact glandular growths composed of cells with hyperchromatic nuclei within the mucosa (Figure 4C). Interestingly, mice with fundic hyperplasia did not show evidence for SPEM.

Table 1.

Histopathologic Analysis According to Experimental Group

| 10-Month group |

18-Month group |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Histopathologic findings | AR−/− (n = 10) | AR+/− (n = 6) | TGF-α−/− (n = 13) | WT (n = 10) | AR−/− (n = 7) | AR+/− (n = 8) | TGFα−/− (n = 8) | WT (n = 6) |

| Metaplasia | ||||||||

| SPEM | 3 (30) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 5 (71) | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| IM | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 3 (43) | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Fundic hyperplasia | 6 (60) | 1 (17) | 0 | 0 | 3 (43) | 3 (38) | 0 | 0 |

| Dysplasia | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 (29) | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Submucosal invasion | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 (29) | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Submucosal infiltration of inflammatory cell | 3 (30) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 5 (71) | 0 | 0 | 0 |

NOTE. All values are expressed as n (%).

Figure 4.

Histopathologic analysis of representative fundic lesions in AR-deficient mice. Sections of fundic stomach from 18-month-old AR-deficient mice were stained with H&E and examined for histopathologic findings. (A and B) Invasive areas with histologic features of dysplasia. (B) Note the expanding dysplasia invading into the adjacent SPEM regions (arrows). (C) Fundic hyperplasia. Note the polypoid growth pattern of foveolar cells. Parietal cells around the polyp were normal. (D) Submucosal infiltration of inflammatory cells. Note the inflammatory cells were locally infiltrated in the submucosa only. There were no inflammatory infiltrates observed in the mucosa. Bar = 50 μm.

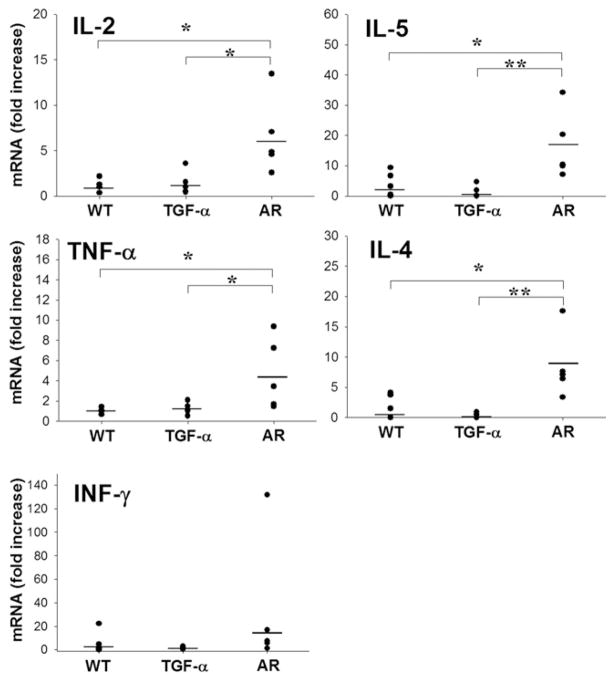

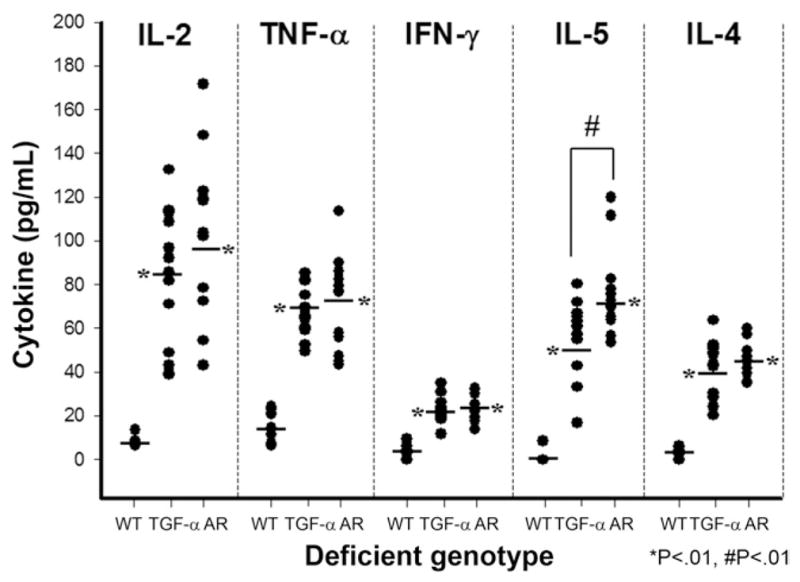

In AR−/− mice, we observed that regions of the mucosa with severe SPEM were generally associated with submucosal infiltration of inflammatory cells (Table 1). The inflammatory cells, chiefly polymorphonuclear leukocytes, were locally infiltrated in the submucosa only, and there were no inflammatory infiltrates in the mucosa (Figure 4D). Given the pattern of submucosal infiltrates, we sought to characterize the nature of the inflammatory response by comparing both serum cytokine levels and tissue cytokine messenger RNA (mRNA) expression in 10-month-old WT mice as well as both TGF-α and AR knockout mice. Figure 5 shows that, compared with WT mice, both TGF-α– deficient and AR-deficient mice showed significant increases in the serum levels of the 5 cytokines assayed: interleukin (IL)-2, IL-4, IL-5, tumor necrosis factor (TNF)-α, and interferon gamma. However, levels of IL-5, a Th2 cytokine, were elevated to a significantly higher level in AR−/− mice compared with TGF-α −/− mice (Figure 5).

Figure 5.

Serum levels of cytokines determined in AR- and TGF-α–deficient mice. Serum levels of IL-2, TNF-α, interferon gamma (IFN-γ), IL-5, and IL-4 were determined in 10-month-old WT, AR-deficient, and TGF-α–deficient mice. Both TGF-α and AR knockout mice showed significant elevations in all 5 cytokines compared with WT mice (*P < .01). In addition, levels of IL-5 were significantly elevated in AR−/− mice compared with TGF-α −/− (#P < .01).

To examine cytokine levels more directly in the gastric tissues, we also assessed mRNA levels for these cytokines in the stomachs of WT, TGF-α– deficient, and AR-deficient mice. Figure 6 shows that gastric tissue mRNA levels for the 5 cytokines were not significantly different in TGF-α knockout mice compared with WT controls. However, mRNA for IL-2, IL-4, IL-5, and TNF-α were all elevated in AR knockout mice compared with both WT and TGF-α– deficient mice. These results suggest that AR knockout mice demonstrate elevations in both Th1 and Th2 cytokine production in the gastric mucosa.

Figure 6.

Cytokine mRNA expression levels in gastric tissue from AR-and TGF-α–deficient mice. Total RNA was prepared from gastric tissue of 10-month-old WT, AR-deficient, and TGF-α–deficient mice. Cyto-kine mRNA expression was determined by quantitative reverse-transcription polymerase chain reaction for IL-2, IL-4, IL-5, TNF-α, and interferon gamma (INF-γ). No significant differences were observed between WT and TGF-α–deficient mice. However, significant elevations in IL-2, IL-4, IL-5, and TNF-α expression were observed in the gastric mucosa of AR-deficient mice compared with WT and TGF-α–deficient mice (*P < .05, **P < .01).

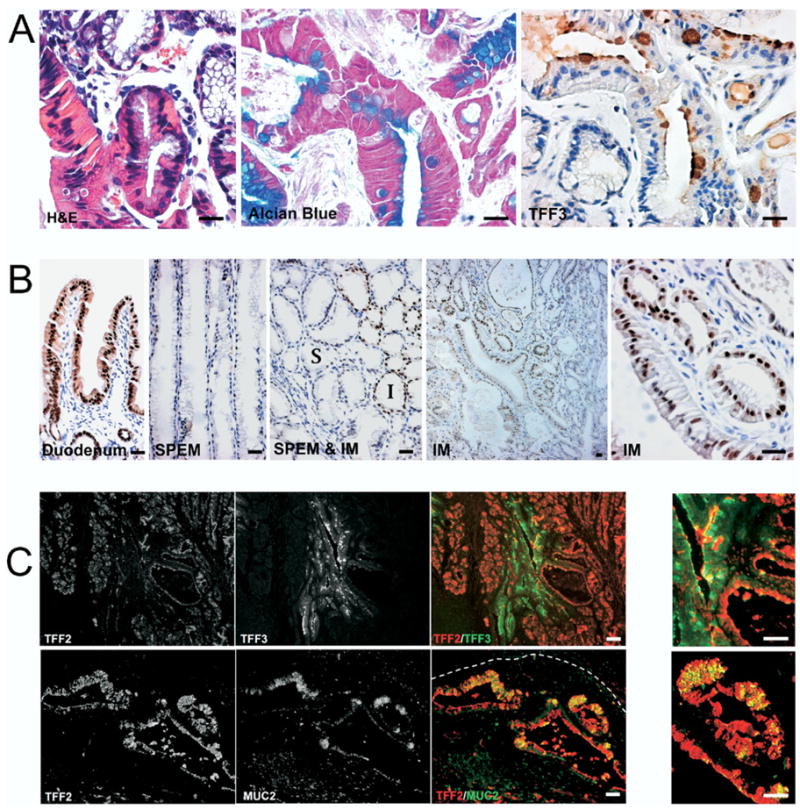

SPEM Progressed Into IM in AR-Deficient Mice

In contrast to humans, mice rarely develop goblet cell IM in response to loss of parietal cells in the fundus and only manifest SPEM lineages in the atrophic stomach.9 While we have described SPEM associated with a number of animal models of oxyntic atrophy,9,23–25 none of these animals developed goblet cell IM in fundus. Nevertheless, in AR−/− mice, we observed progression of SPEM to goblet cell IM. Alcian blue–staining goblet cells were present in the fundic mucosa of 18 month-old AR−/− mice in proximity to regions of gastritis cystica profunda (Figure 7A). To confirm the identification of goblet cell IM, we immunostained sections of fundus with antibodies against TFF3. In the mucosal glands of 18-month-old AR−/− mice, TFF3-positive goblet cells were observed (Figure 7A). We have previously noted that in humans IM expresses the duodenal transcription factor Pdx-1, while Pdx-1 is not expressed in SPEM.26 We therefore examined Pdx-1 staining in the fundus of 18-month-old AR−/− mice. While Pdx-1 was not expressed in the fundus of WT or TGF-α– deficient mice (data not shown), IM regions in AR knockout mice showed cells with prominent nuclear expression of Pdx-1 (Figure 7B). Of note, however, SPEM in the surrounding regions of the metaplastic mucosa did not demonstrate Pdx-1 expression. These results indicate that the AR-deficient mice are recapitulating many of the aspects of human gastric IM. Interestingly, we did not detect Cdx-2 immunostaining in either the duodenum or areas of IM in the fundus (data not shown).

Figure 7.

SPEM progresses to intestinal metaplasia in 18-month-old AR-deficient mice. (A) To identify goblet cell IM, sections of fundic stomach from 18 month-old AR-deficient mice were stained for H&E, Alcian blue, and TFF3 immunohistochemistry in adjacent sections. The stains show Alcian blue and TFF3-positive goblet cells within the mucosa. (B) To investigate the characteristics of goblet cell IM in stomach, sections from AR-deficient mice fundic mucosa were immunostained for the duodenal transcription factor Pdx-1. While Pdx-1 was not expressed in the SPEM regions, IM regions showed cells with prominent nuclear expression of Pdx-1. Note that no expression of Pdx-1 was observed in SPEM (S) in the surrounding regions of the IM (I). (C) To investigate IM development in the setting of SPEM, fundic sections from 18-month-old AR-deficient mice were dual stained for immunofluorescence labeling of TFF2/SP with TFF3 or TFF2/SP with MUC2. Note the TFF3-positive goblet cells appeared within TFF2/SP-positive glands (upper panels). In the invasive area (white dashed line indicates the position of the muscularis mucosa), cells staining for both TFF2/SP and MUC2 were observed in cystically dilated glands (lower panels). Panels at the far right show higher-magnification views of merged fluorescence images showing cells with dual labeling for either TFF2 with TFF3 or TFF2 with MUC2. Bar = 25 μm.

Because goblet cell IM in AR−/− mice always developed in the setting of the mucosa with marked SPEM, we hypothesized that metaplastic SPEM cells may progress into IM goblet cells. To investigate the relationship of goblet cell IM to SPEM, we used dual immunofluorescence labeling to examine staining for TFF2/SP with TFF3 or TFF2/SP with MUC2. Dual staining of TFF2/SP and TFF3 showed the presence of glands containing both TFF2/SP-positive SPEM cells and TFF3-positive IM (Figure 7C, upper panel). In many instances, cells within both branching glandular structures as well as within cystic glands showed dual staining for both TFF2/SP and TFF3. Similar results were observed with dual staining for TFF2/SP and MUC2. In particular, in invasive areas of gastritis cystica profunda, cells staining for both TFF2/SP and MUC2 were widely distributed in the dilated cystic glands (Figure 7C, lower panel). These results suggested that SPEM glands may give rise to IM.

Discussion

Gastric adenocarcinoma can be categorized by 2 histologic characteristics. The diffuse type is remarkable for its poorly differentiated phenotype in which the glandular architecture is completely lost. Recent investigations in cohorts of familial diffuse gastric cancer as well as in some patients with sporadic diffuse cancer have shown a causal association of carcinogenesis with mutations in cadherins and catenins.27–29 Mutations in E-cadherin or β-catenin lead to a loss of polarity and promote dysplastic transition.30 Intestinal-type tumors, which make up the majority of sporadic tumors worldwide, appear to evolve through a series of discrete steps originally described by Correa.4 Intestinal-type cancers are strongly associated with oxyntic atrophy3 as well as a number of metaplastic lineages.31–33 The original description of the metaplasia-to-cancer scenario in gastric cancer focused on the role of goblet cell IM as a putative precursor to gastric neoplasia. It is now clear that a second metaplastic lesion, SPEM, is also associated with gastric cancer. Although SPEM accompanied by gastric atrophy is associated more commonly with gastric cancer than IM, the exact relationship between the 2 metaplasias and intestinal-type cancer remains unclear.

The roles of specific metaplasias in gastric cancer have not been clarified by studies using mouse models of Helicobacter spp infection, where IM was not observed but SPEM appeared as a prominent precursor to gastric neoplasia.9 Indeed, with the exception of forced ectopic in the stomach expression of the master regulating transcription factor Cdx2,34 none of the mouse models of gastric atrophy and metaplasia have developed goblet cell IM. It is notable, however, that mice with forced expression of Cdx2 in the stomach do develop goblet cells in the gastric mucosa and progress to dysplastic lesions.35 In contrast to the mouse, H pylori infection in Mongolian gerbils does produce goblet cell IM. Importantly, however, recent investigations have documented that SPEM develops in infected gerbils long before IM and that IM develops in the setting of a fundic mucosa already showing SPEM as the predominant metaplasia.36 In the present studies, AR−/− mice developed oxyntic atrophy and SPEM by 10 months of age, which was followed by goblet cell IM arising in the context of SPEM. Importantly, we observed that goblet cells were present in the luminal region of glands that also contained SPEM at their bases. Furthermore, at the interface of the SPEM and IM regions, we observed cells that dually expressed either TFF2 and MUC2 or TFF2 and TFF3. Similar dual lineage glands were also observed in H pylori–infected Monogolian gerbils.36 These results suggest that IM can arise from foci of TFF2-expressing metaplastic cells within SPEM glands. This type of metaplastic lineage conversion has also been observed in the ulcer-associated cell lineage described by Wright et al in association with Crohn’s disease in the colon.37,38 The results here indicate that a dynamic process of metaplasia may give rise first to SPEM in the setting of oxyntic atrophy followed by evolution of IM.

We have previously reported that AR-deficient mice develop SPEM more quickly and to a greater extent following induction of acute oxyntic atrophy with administration of the parietal cell protonophore DMP-777.22 Nevertheless, while those original studies were performed in 8-week-old animals, the present investigations indicate that AR-null mice progress to oxyntic atrophy and SPEM after 10 months of age without drug treatment. Because of the prominent changes in these mice, we examined the stomachs for the presence of Helicobacter spp infection but were unable to identify any Helicobacter present in the AR-deficient mice. Thus, while we cannot rule out other possible inciting infections,11,39 it appears that the AR-null mice can progress to oxyntic atrophy and metaplastic lesions spontaneously. Such spontaneous progression to oxyntic atrophy and metaplasia has previously been observed in insulin-gastrin transgenic mice,40 although those mice developed SPEM but not IM. One possible explanation for the development of metaplasia and neoplasia in AR knockout mice may relate to the accompanying chronic inflammatory response. While Helicobacter felis–infected mice develop SPEM in the setting of marked intramucosal and submucosal infiltrates, we observed only moderate submucosal infiltrates in AR−/− mice. Importantly, however, these submucosal infiltrates were often associated with regions of SPEM in the mucosa. While Helicobacter infection has generally been associated with a Th1 immune response,41,42 we observed a mixed picture of elevations of both Th1 and Th2 cytokine expression in the gastric tissue of AR−/− mice compared with both age-matched WT and TGF-α −/− mice. Additionally, the submucosal infiltrates were comprised predominantly of polymorphonuclear leukocytes. Based on recent published data, AR secreted by hematopoietic (probably Th2) cells significantly enhances the expulsion of intestinal parasites.43 Comparing AR-deficient and WT C57BL/6 mice after infection with Trichuris muris, worm clearance was significantly delayed in AR-deficient mice. In a reconstitution experiment, AR-expressing bone marrow cells significantly restored parasite clearance in AR-deficient mice. The exact cause for inciting a chronic submucosal inflammatory response in AR-deficient mice is not clear but could be related to a response to chronic injury or autoimmunity.

As noted in our previous studies,22 the phenotypes for AR-deficient and TGF-α–null mice were markedly different. TGF-α–null mice did not develop any significant mucosal lesions in the fundus, in comparison with the prominent changes in the AR-deficient mice. These results indicate that, while both AR and TGF-α exert their influences on mucosal cells through the EGF receptor, the actions of these peptides on cell physiology must be distinct. Parietal cells are known to secrete several EGF receptor ligands, including TGF-α, AR, and heparin-binding EGF.14 –17 Other gastric mucosal cells can secrete at least TGF-α and EGF. Recent investigations have suggested that EGF receptor ligands may compete for occupancy of the EGF receptor.44,45 Thus, alterations in the levels of certain EGF receptor ligands may lead to increased signaling by others. The net effect of the loss of AR may therefore reflect a cascade of signaling through EGF receptor occupancy by other receptor ligands. Over time, these changes might be expected to regulate both inflammatory response and long-term lineage differentiation.

In conclusion, these studies show that SPEM is an early metaplastic change in the fundus of the stomach in the setting of AR deficency. We observed both SPEM IM as well as evidence of early invasive neoplasia in AR-deficient mice. IM evolved in the setting of precedent SPEM, suggesting that IM arises from SPEM. These findings in AR-null mice represent the first mouse model of both SPEM and IM induction associated with eventual neoplasia. Collectively, these results indicate that atrophic gastritis leads to the generation of a dynamic scenario of metaplastic changes that predispose to the development of gastric neoplasia.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Drs Adam Smolka, Nicholas Wright, Christopher Wright, Daniel Podolsky, and David Alpers for the gifts of antibodies.

Funding

Supported by a Department of Veterans Affairs Merit Review Award (to J.R.G.); a pilot project grant from the Vanderbilt Specialized Program of Research Excellence in Gastrointestinal Cancer (P50 CA95103 to J.R.G.); the American Gastroenterological Association Funderburg Award in Gastric Biology Related to Cancer (to J.R.G.); a Discovery Grant from the Vanderbilt-Ingram Cancer Center and National Institutes of Health grant DK071590 (to J.R.G.); National Institutes of Health grants DK73902, DK58587, and DK77955 (to R.M.P.); and a grant from the Vanderbilt Digestive Diseases Research Center (DK058404 to R.M.P.).

Abbreviations in this paper

- AR

amphiregulin

- EGF

epidermal growth factor

- IL

interleukin

- IM

intestinal metaplasia

- SPEM

spasmolytic polypeptide-expressing metaplasia

- TGF

transforming growth factor

- TFF

trefoil factor family

- TNF

tumor necrosis factor

- WT

wild-type

Footnotes

Conflicts of interest

The authors disclose no conflicts.

Supplementary Data

Note: To access the supplementary material accompanying this article, visit the online version of Gastroenterology at www.gastrojournal.org, and at doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2008.12.037.

References

- 1.Karam SM, Leblond CP. Dynamics of epithelial cells in the corpus of the mouse stomach. I. Identification of proliferative cell types and pinpointing of the stem cell. Anat Rec. 1993;236:259–279. doi: 10.1002/ar.1092360202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Karam SM, Leblond CP. Dynamics of epithelial cells in the corpus of the mouse stomach. III. Inward migration of neck cells followed by progressive transformation into zymogenic cells. Anat Rec. 1993;236:297–313. doi: 10.1002/ar.1092360204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.El-Zimaity HM, Ota H, Graham DY, et al. Patterns of gastric atrophy in intestinal type gastric carcinoma. Cancer. 2002;94:1428–1436. doi: 10.1002/cncr.10375. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Correa P. A human model of gastric carcinogenesis. Cancer Res. 1988;48:3554–3560. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Filipe MI, Munoz N, Matko I, et al. Intestinal metaplasia types and the risk of gastric cancer: a cohort study in Slovenia. Int J Cancer. 1994;57:324–329. doi: 10.1002/ijc.2910570306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Reis CA, David L, Correa P, et al. Intestinal metaplasia of human stomach displays distinct patterns of mucin (MUC1, MUC2, MUC5AC, and MUC6) expression. Cancer Res. 1999;59:1003–1007. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Taupin D, Pedersen J, Familari M, et al. Augmented intestinal trefoil factor (TFF3) and loss of pS2 (TFF1) expression precedes metaplastic differentiation of gastric epithelium. Lab Invest. 2001;81:397–408. doi: 10.1038/labinvest.3780247. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Goldenring JR, Nomura S. Differentiation of the Gastric Mucosa III. Animal models of oxyntic atrophy and metaplasia. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol. 2006;291:G999–G1004. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.00187.2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wang TC, Goldenring JR, Dangler C, et al. Mice lacking secretory phospholipase A2 show altered apoptosis and differentiation with Helicobacter felis infection. Gastroenterology. 1998;114:675–689. doi: 10.1016/s0016-5085(98)70581-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Schmidt PH, Lee JR, Joshi V, et al. Identification of a metaplastic cell lineage associated with human gastric adenocarcinoma. Lab Invest. 1999;79:639–646. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kang W, Rathinavelu S, Samuelson LC, et al. Interferon gamma induction of gastric mucous neck cell hypertrophy. Lab Invest. 2005;85:702–715. doi: 10.1038/labinvest.3700260. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Oshima M, Oshima H, Matsunaga A, et al. Hyperplastic gastric tumors with spasmolytic polypeptide-expressing metaplasia caused by tumor necrosis factor-alpha-dependent inflammation in cyclooxygenase-2/microsomal prostaglandin E synthase-1 transgenic mice. Cancer Res. 2005;65:9147–9151. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-05-1936. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Halldorsdottir AM, Sigurdardottrir M, Jonasson JG, et al. Spasmolytic polypeptide-expressing metaplasia (SPEM) associated with gastric cancer in Iceland. Dig Dis Sci. 2003;48:431–441. doi: 10.1023/a:1022564027468. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Akagi M, Yokozaki H, Kitadai Y, et al. Expression of amphiregulin in human gastric cancer cell lines. Cancer. 1995;75:1460–1466. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Beauchamp RD, Barnard JA, McCutchen CM, et al. Localization of transforming growth factor alpha and its receptor in gastric mucosal cells. Implications for a regulatory role in acid secretion and mucosal renewal. J Clin Invest. 1989;84:1017–1023. doi: 10.1172/JCI114223. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Dempsey PJ, Goldenring JR, Soroka CJ, et al. Possible role of transforming growth factor alpha in the pathogenesis of Ménétrier’s disease: supportive evidence form humans and transgenic mice. Gastroenterology. 1992;103:1950–1963. doi: 10.1016/0016-5085(92)91455-d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Murayama Y, Miyagawa J, Higashiyama S, et al. Localization of heparin-binding epidermal growth factor-like growth factor in human gastric mucosa. Gastroenterology. 1995;109:1051–1059. doi: 10.1016/0016-5085(95)90562-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Tang LH, Modlin IM, Lawton GP, et al. The role of transforming growth factor alpha in the enterochromaffin-like cell tumor autonomy in an African rodent mastomys. Gastroenterology. 1996;111:1212–1223. doi: 10.1053/gast.1996.v111.pm8898635. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Nomura S, Settle SH, Leys CM, et al. Evidence for repatterning of the gastric fundic epithelium associated with Ménétrier’s disease and TGFalpha overexpression. Gastroenterology. 2005;128:1292–1305. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2005.03.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Takaishi S, Cui G, Frederick DM, et al. Synergistic inhibitory effects of gastrin and histamine receptor antagonists on Helicobacter-induced gastric cancer. Gastroenterology. 2005;128:1965–1983. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2005.03.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Katada K, Naito Y, Mizushima K, et al. Gene expression profiles on hypoxia and reoxygenation in rat gastric epithelial cells: a high-density DNA microarray analysis. Digestion. 2006;73:89–100. doi: 10.1159/000094039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Nam KT, Varro A, Coffey RJ, et al. Potentiation of oxyntic atrophy-induced gastric metaplasia in amphiregulin-deficient mice. Gastroenterology. 2007;132:1804–1819. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2007.03.040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Nomura S, Yamaguchi H, Ogawa M, et al. Alterations in gastric mucosal lineages induced by acute oxyntic atrophy in wild-type and gastrin-deficient mice. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol. 2005;288:G362–G375. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.00160.2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Yamaguchi H, Goldenring JR, Kaminishi M, et al. Identification of spasmolytic polypeptide expressing metaplasia (SPEM) in remnant gastric cancer and surveillance postgastrectomy biopsies. Dig Dis Sci. 2002;47:573–578. doi: 10.1023/a:1017920220149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Goldenring JR, Ray GS, Coffey RJ, et al. Reversible drug-induced oxyntic atrophy in rats. Gastroenterology. 2000;118:1080–1093. doi: 10.1016/s0016-5085(00)70361-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Leys CM, Nomura S, Rudzinski E, et al. Expression of Pdx-1 in human gastric metaplasia and gastric adenocarcinoma. Hum Pathol. 2006;37:1162–1168. doi: 10.1016/j.humpath.2006.04.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Guilford P, Hopkins J, Harraway J, et al. E-cadherin germline mutations in familial gastric cancer. Nature. 1998;392:402–405. doi: 10.1038/32918. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Guilford PJ, Hopkins JB, Grady WM, et al. E-cadherin germline mutations define an inherited cancer syndrome dominated by diffuse gastric cancer. Hum Mutat. 1999;14:249–255. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1098-1004(1999)14:3<249::AID-HUMU8>3.0.CO;2-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kim HS, Hong EK, Park SY, et al. Expression of beta-catenin and E-cadherin in the adenoma-carcinoma sequence of the stomach. Anticancer Res. 2003;23:2863–2868. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lowy AM, Knight J, Groden J. Restoration of E-cadherin/beta-catenin expression in pancreatic cancer cells inhibits growth by induction of apoptosis. Surgery. 2002;132:141–148. doi: 10.1067/msy.2002.125168. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Smith VC, Genta RM. Role of Helicobacter pylori gastritis in gastric atrophy, intestinal metaplasia, and gastric neoplasia. Microsc Res Tech. 2000;48:313–320. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-0029(20000315)48:6<313::AID-JEMT1>3.0.CO;2-Y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Dixon MF, Genta RM, Yardley JH, et al. Classification and grading of gastritis. The updated Sydney System. International Workshop on the Histopathology of Gastritis, Houston 1994. Am J Surg Pathol. 1996;20:1161–1181. doi: 10.1097/00000478-199610000-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Hattori T. Development of adenocarcinomas in the stomach. Cancer. 1986;57:1528–1534. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(19860415)57:8<1528::aid-cncr2820570815>3.0.co;2-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Silberg DG, Sullivan J, Kang E, et al. Cdx2 ectopic expression induces gastric intestinal metaplasia in transgenic mice. Gastroenterology. 2002;122:689–696. doi: 10.1053/gast.2002.31902. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Mutoh H, Sakurai S, Satoh K, et al. Development of gastric carcinoma from intestinal metaplasia in Cdx2-transgenic mice. Cancer Res. 2004;64:7740–7747. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-04-1617. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Yoshizawa N, Takenaka Y, Yamaguchi H, et al. Emergence of spasmolytic polypeptide-expressing metaplasia in Mongolian gerbils infected with Helicobacter pylori. Lab Invest. 2007;87:1265–1276. doi: 10.1038/labinvest.3700682. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Wright NA, Pike C, Elia G. Induction of a novel epidermal growth factor-secreting cell lineage by mucosal ulceration in human gastrointestinal stem cells. Nature. 1990;343:82–85. doi: 10.1038/343082a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Wright NA, Poulsom R, Stamp GW, et al. Epidermal growth factor (EGF/URO) induces expression of regulatory peptides in damaged human gastrointestinal tissues. J Pathol. 1990;162:279–284. doi: 10.1002/path.1711620402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Merchant JL. Inflammation, atrophy, gastric cancer: connecting the molecular dots. Gastroenterology. 2005;129:1079–1082. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2005.07.038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Wang TC, Koh TJ, Varro A, et al. Processing and proliferative effects of human progastrin in transgenic mice. J Clin Invest. 1996;98:1918–1929. doi: 10.1172/JCI118993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Fox JG, Blanco M, Murphy JC, et al. Local and systemic immune responses in murine Helicobacter felis active chronic gastritis. Infect Immun. 1993;61:2309–2315. doi: 10.1128/iai.61.6.2309-2315.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Mohammadi M, Czinn S, Redline R, et al. Helicobacter-specific cell-mediated immune responses display a predominant Th1 phenotype and promote a delayed-type hypersensitivity response in the stomachs of mice. J Immunol. 1996;156:4729–4738. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Zaiss DM, Yang L, Shah PR, et al. Amphiregulin, a TH2 cytokine enhancing resistance to nematodes. Science. 2006;314:1746. doi: 10.1126/science.1133715. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Luetteke NC, Qiu TH, Fenton SE, et al. Targeted inactivation of the EGF and amphiregulin genes reveals distinct roles for EGF receptor ligands in mouse mammary gland development. Development. 1999;126:2739–2750. doi: 10.1242/dev.126.12.2739. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Riese DJ, II, Komurasaki T, Plowman GD, et al. Activation of ErbB4 by the bifunctional epidermal growth factor family hormone epiregulin is regulated by ErbB2. J Biol Chem. 1998;273:11288–11294. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.18.11288. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.