Abstract

The Haloalkanoic Acid Dehalogenase (HAD)1 enzyme superfamily is the largest family of phosphohydrolases. In HAD members, the structural elements that provide the binding interactions that support substrate specificity are separated from those that orchestrate catalysis. For most HAD phosphatases a cap domain functions in substrate recognition. However, for the HAD phosphatases which lack a cap domain, an alternate strategy for substrate selection must be operative. One such HAD phosphatase, GmhB of the HisB subfamily was selected for structure-function analysis. Herein, the X-ray crystallographic structures of E. coli GmhB in the apo form (1.6 Å resolution), complexed with Mg2+ and orthophosphate (1.8 Å resolution), and with Mg2+ and Dglycero-D-manno-heptose-1β,7-bisphosphate (2.2 Å resolution) were determined, in addition to the structure of B. bronchiseptica GmhB bound to Mg2+ and orthophosphate (1.7 Å resolution). The structures show that in place of a cap domain, the GmhB catalytic site is elaborated by three peptide inserts or loops that pack to form a concave, semicircular surface around the substrate leaving group. Structure-guided kinetic analysis of site-directed mutants was carried out in parallel with a bioinformatics study of sequence diversification within the HisB subfamily to identify loop residues that serve as substrate recognition elements and that distinguish GmhB from its subfamily counterpart, the histdinol-phosphate phosphatase domain of HisB. We show that GmhB and the histidinol-phosphate phosphatase domain use the same design of three substrate-recognition loops inserted into the cap domain, yet through selective residue usage on the loops, have achieved unique substrate specificity and thus novel biochemical function.

Keywords: GmhB; D-glycero-D-manno-heptose-1,7-bisphosphate phosphatase; histidinol-phosphate phosphatase; HisB; phosphoryl transfer; substrate specificity; HAD superfamily; biochemical function; divergent evolution

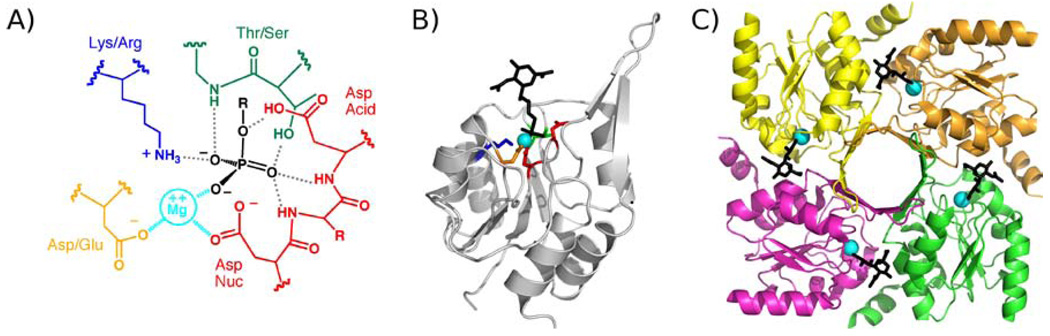

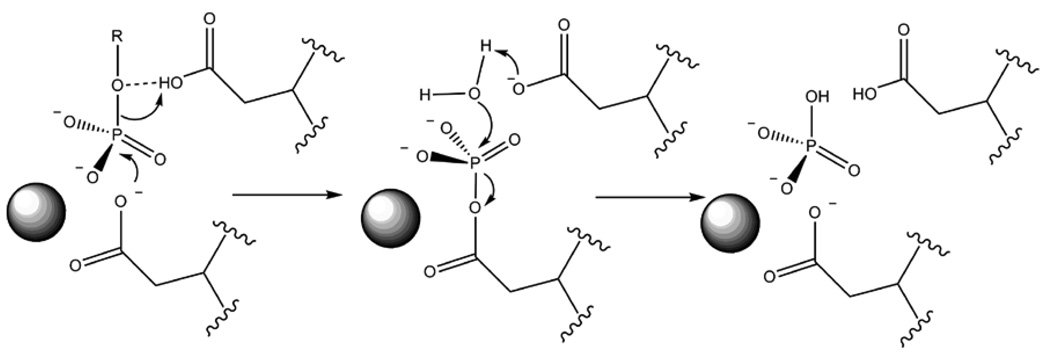

The Haloalkanoic Acid Dehalogenase (HAD)1 enzyme superfamily(7–8) is Nature’s major supplier of organophosphate metabolite phosphohydrolases (phosphatases). The HAD phosphatase catalytic site is housed in the Rossmann-like fold core domain and is comprised by a Mg2+ cofactor, an Asp nucleophile, an Asp acid/base and two conserved hydrogen bond donors (Thr/Ser and Lys/Arg) which function in collaboration with main-chain amide units to bind the substrate phosphoryl group (Fig. 1)(9). The phosphoryl group is transferred to the Asp nucleophile to form an aspartylphosphate intermediate, which is subsequently dephosphorylated by attack of an activated water molecule (Scheme 1). The catalytic site provides only weak binding interaction with the substrate phosphoryl group in the ground state and reserves strong interaction for stabilization of the trigonal bipyramidal phosphorane-like transition states(10–12). With the exception of the catalytic Asp acid residue, which donates a hydrogen bond to the oxygen atom that bridges the organic unit of the leaving group to the phosphorus atom, there is virtually no interaction between the leaving group and the residues that form the catalytic pocket (Fig. 1). Thus, the structural elements that provide the additional binding interaction necessary to secure the physiological substrate are separate from the structural elements of catalysis. Consequently, changes needed for adaptation to a novel substrate can be made to the constellation of residues that interact with the substrate-leaving group (i.e., the substrate specificity residues) without perturbing the catalytic machinery. The autonomy of the structural elements of substrate recognition has allowed the successful adaptation of the HAD phosphatases to a wide variety of biochemical niches(13).

Figure 1.

A) Diagram of the HAD catalytic template depicting the binding interaction between substrate (black), Mg2+ cofactor (cyan), and the conserved catalytic residues of the HAD phosphatase active site. B) The structure of 2-keto-3-deoxy-D-glycero-Dgalactonononate-9-phosphate phosphatase monomer bound with Mg2+ (cyan), vanadate and 2-keto-3-deoxy-5-acetylamine-D-glycero-D-galactonononate-9-phosphate (black) (23). The conserved catalytic residues are colored as in A. C) The tetramer of 2-keto-3-deoxy-D-glycero-D-galactonononate-9-phosphate phosphatase tetramer depicted as ribbons. The subunits are individually colored and ligands colored as in B.

Scheme 1.

The general catalytic mechanism for phosphohydrolase members of the HAD superfamily. The Mg2+ cofactor is depicted as a sphere.

Inspection of the numerous HAD family sequences and structures reveals a multiplicity of ways in which the basic Rossmann-like scaffold has been elaborated, through the course of evolution, with sequence inserts that function in substrate recognition(14–15). For the vast majority of the HAD phosphatases the added sequence forms a separate folding domain known as the cap domain. The cap domain provides a large surface area for interaction with the leaving group of the phosphorylated metabolite, which in turn contributes to the association of the cap domain and catalytic domain in preparation for catalytic turnover (Fig. 2)(16–18). The “capless” HAD phosphatases on the other hand, are well suited to function in the removal of phosphoryl groups from phosphorylated macromolecules because such substrates require a fully accessible active site(19–21). Yet, remarkably, some capless HAD phosphatases are known to be selective for small substrates(22–23). Structure-function analysis of these HAD members are underway in our laboratories in order to determine their mechanisms of substrate recognition.

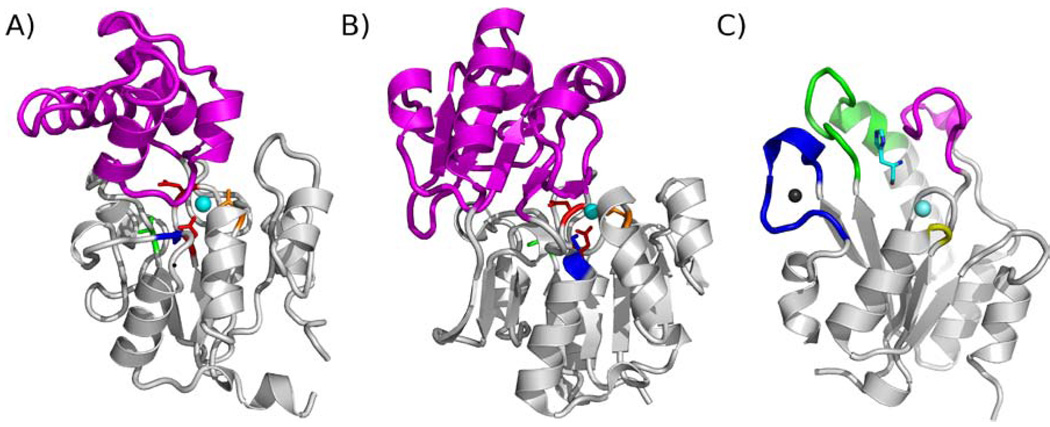

Figure 2.

A) Ribbon diagram of C1 HAD phosphatase Q8A5V9 (Steven Almo, Albert Einstein College of Medicine, unpublished data). The Rossmann fold catalytic domain is colored gray, conserved catalytic residues are shown as sticks and colored as in Fig 1A. The Mg2+ is a cyan sphere and the cap domain is colored magenta. B) The structure of the C2 HAD phosphatase BT4131(39). C) The structure of the histidinol-phosphate phosphatase domain of E. coli HisB(24). The histidinol ligand (shown as sticks) is colored cyan. The Zn2+ and Mg2+ are depicted as black and cyan spheres. The Zn2+ binding loop (blue), loop 1 (magenta), loop 2 (green) and the Mg2+-binding loop (yellow) are colored to coordinate with the structures shown in Figure 4 and Figure 7.

D-glycero-D-manno-heptose-1,7-bisphosphate phosphatase (GmhB) is a member of the HAD HisB subfamily. The subfamily is named after the N-terminal domain of the bifunctional histidine biosynthetic pathway enzyme histidinol-phosphate phosphatase/imidazole-glycerol-phosphate dehydratase known as HisB. The structure of the E. coli histidinol-phosphate phosphatase domain of HisB shows that it is capless and that it possesses a novel Zn2+-binding loop (Fig. 2)(24). However, because the structure is that of one single domain of a two-domain protein, the interactions between the two domains are not known and it is not certain if or how the C-terminal domain may interact with the phosphatase active site.

The fact that GmhB is capless and monomeric, and shows high catalytic efficiency (kcat/Km ~ 1 × 107 M−1 s−1) and substrate specificity (see companion paper(25)), suggested that it might employ a unique strategy in substrate binding compared to members of other subfamilies of capless HAD phosphatases. Herein, we report the apo and liganded structures of GmhB from E. coli K-12 and Bordetella bronchiseptica and present the results from a probe of the structural elements of substrate recognition via site-directed mutagenesis. These findings, together with information derived from bioinformatics analysis, shed new light on the structural basis for the biochemical divergence of GmhB biochemical function among the HAD phosphatases.

EXPERIMENTAL METHODS

X-ray Structure Determination

The B. bronchiseptica GmhB (Swiss Prot accession #Q7WG29) was prepared as described in the companion paper(25). The selenomethionine-substituted E. coli K-12 GmhB (Swiss Prot accession #P63288) was prepared using a methionine auxotroph of E. coli (B-834)) grown in a defined medium containing 40 mg/L selenomethionine and purified using the same protocol as used for the native enzyme(25). The crystallization conditions were screened at 25 °C using the Hampton Index Screen via the hanging-drop vapor-diffusion method. The optimal conditions found for B. bronchiseptica GmhB crystallization are 10 mg/ml protein, 10 mM fructose 1,6-bisphosphate, 0.05 M magnesium formate, 100 mM sarcosine, 5 % dioxane and 25 % PEG 3350 (25 °C). The crystal was protected with paratone-N before flash freezing in a stream of N2 gas at 100 K. The optimal conditions found for E. coli GmhB crystallization are 25 mg/ml of protein, 0.1 M Tris (pH 7.5), 5 mM MgCl2, and 25% PEG 3350 (25 °C). For the apo data set, the GmhB crystal was transferred to a solution consisting of 0.1 M Tris (pH 7.5), 5 mM MgCl2, 35% PEG 3350, and 10% glycerol for 5 min and then transferred to the mother liquor plus 20% glycerol for 5 min before flash-freezing in a gaseous stream of N2 at 100 K. For E. coli GmhB complexed with orthophosphate the crystal of the apo enzyme was transferred to a cryo-protecting solution containing 0.1 M of Tris (pH 7.5), 5 mM MgCl2, 5 mM imidodiphosphate, 25% PEG 3350, and 20% glycerol for 5 min, and flash-frozen in a stream of N2 gas at 100 K. The complex of GmhB with D-glycero-manno-heptose-1β,7-bisphosphate (GmhB-Mg2+-H1β,7bisP) was obtained by soaking crystals of the apo enzyme in a 10 µl drop consisting of 0.1 M Tris (pH 7.5), 5 mM MgCl2, 35% PEG 3350, 30 mM D-glycero-D-manno-heptose-1β-phosphate and 30 mM D-glycero-D-manno-heptose-1β,7-bisphosphate for 15 min. The crystal was protected with paratone-N before flash freezing in a stream of N2 gas at 100 K.

Diffraction data were collected at the National Synchrotron Light Source at the Brookhaven National Laboratory, New York. The diffraction data set was collected on a Rigaku RU300 generator equipped with a Raxis IV++ area detector. All diffraction data were processed in the DENZO/SCALEPACK program package (26). The data set for the E. coli apo GmhB was phased using one subunit of histidinol-phosphate phosphatase (24) (PDB accession code 2FPR; 28% sequence identity with GmhB) as the search model for molecular replacement in the program MOLREP (27) of the CCP4 program package. (28). The initial model was refined by manual rebuilding in COOT (29) with alternating rounds of refinement in CNS (30). The quality of the final model was assessed by MOLPROBITY (31). The E. coli apo GmhB structure was used as the search model for molecular replacement to phase the liganded E. coli GmhB structures (which crystallized in a different space group) as well as the B. bronchiseptica GmhB structure. Refinement of the B. bronchiseptica GmhB data set was debiased by including the phases from selenomethionine. The data collection and refinement statistics are summarized in Table 1.

Table 1.

Data collection statistics. Values in parentheses are for the highest resolution shell.

| Crystal | Ec GmhB apo |

Ec GmhB Mg2+/Pi |

Ec GmhB /Mg2+/ H1β,7bisP |

Bb GmhB Mg2+/Pi |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Space group | P212121 | P21212 | P21212 | P1 |

| Unit cell dimensions (Å) | a = 51.77 b = 63.97 c = 103.20 |

a = 64.48 b = 50.00 c = 51.88 |

a = 63.67 b = 51.57 c = 52.19 |

a = 38.1 b = 58.4 c = 85.7 |

| X-ray source | X12B, NSLS | X25C, NSLS | R AxisIV++ | X29, NSLS |

| Wavelength (Å) | 0.9786 | 1.1000 | 1.5418 | 1.0000 |

| Resolution (Å) | 1.64 (1.64–1.70) | 1.8 (1.79–1.85) | 2.2 (2.18–2.26) | 1.7 (1.68–1.74) |

| Total / unique reflections | 207847/42543 | 109143/16358 | 32412/9183 | 79124/6443 |

| Completeness (%) | 99.4 (98.4) | 99.9 (99.6) | 97.2 (99.0) | 94.6 (77.3) |

| I/σ (I) | 16.7 (2.5) | 33.5 (3.7) | 10.1 (1.9) | 18.4 (3.2) |

| Rmerge | 0.072 (0.491) | 0.048 (0.501) | 0.073 (0.427) | 0.059 (0.253) |

| No. mol/ asymmetric unit | 2 | 1 | 1 | 4 |

| No. ordered/total residues | 372/382 | 182/191 | 182/191 | 716/716 |

| No. of non-solvent atoms per asymmetric unit | 2888 | 1433 | 1457 | 5373 |

| No. of reflections (work/free) | 76862/7540 | 26258/2844 | 8332/420 | 147262/14317 |

| Rwork/Rfree | 0.17 / 0.21 | 0.19 / 0.23 | 0.18/ 0.25 | 0.17/0.20 |

| Total waters | 378 | 110 | 79 | 666 |

| No. Zn2+/Mg2+ | 2/0 | 1/1 | 1/1 | 4/4 |

| No./ligand | 2/acetates | none | 1/H1β,7bisP | 5/Pi 1/fructose |

| Average B-factor (Å2) | ||||

| Amino acid residues | 15.8 | 31.3 | 31.1 | 19.4 |

| Mg2+ ions | - | 35.2 | 21.5 | 14.4 |

| Zn2+ ions | 12.6 | 34.6 | 33.8 | 19.9 |

| water | 26.0 | 41.2 | 33.6 | 26.3 |

| ligands | 12.7 | 39.2 | 42.9 | 20.0 |

| rms deviation | ||||

| Bond lengths (Å) | 0.006 | 0.028 | 0.010 | 0.008 |

| Bond angles (deg) | 1.069 | 2.258 | 1.268 | 1.122 |

| Ramachandran favored/allowed (%) | 98.1/100 | 97.2/100 | 96.7/100 | 97.6/100 |

Native Molecular Weight Determination

The molecular masses of E. coli and B. bronchiseptica GmhB were determined using gravity-flow gel-filtration chromatography. Specifically, the enzyme was chromatographed at 4 °C on a calibrated (Pharmacia Gel Filtration Calibration Kit) 1.5 × 180 cm Sephacryl S-200 column (Pharmacia) using 50 mM K+HEPES/5 mM MgCl2/ 1 mM DTT (pH 7.0 at 25 °C), at a flow rate of 1 mL/min, as eluant. The molecular weight was determined from a plot of log(molecular weight) of a standard protein vs. elution volume as reference.

Preparation of Site Directed Mutants of E. coli GmhB

Mutagenesis was carried out using a PCR based strategy with commercial primers and the wild-type GmhB/pET-23b plasmid serving as template. The purified PCR products were used to transform to BL21(DE3) competent cells. The mutant gene sequences were verified by DNA sequencing. The mutant proteins were prepared in the same manner as used for wild-type GmhB(25).

Ligand Docking Models

Parameters for bond-length, angles and van der Waals interactions for the α- and β- anomers of D-glycero-D-manno-heptose-1,7-bisphosphate substrates were generated based on ideal models. Substrates were placed in the active site such that the phosphoryl group overlayed with the phosphoryl group position in the GmhB complex. Active-site waters were removed from the model. Energy minimization of the complex was carried out in CNS(30), utilizing only bond parameterization and van der Waals contacts.

DNA Binding Assay

DNA binding was assessed via gel-shift assays carried out according to known procedures(32). Solutions containing 0.5–1.0 mM GmhB and 1 molar equivalent of calf thymus DNA (Invitrogen) in 50 mM Tris/100 mM NaCl/2 mM MgCl2 (pH 7.5) were incubated at 25 °C for 30 min. Loading buffer (5X) (50% glycerol, 30 mM Tris pH 6.8) was added and the mixture was subjected to chromatography on a 12% polyacrylamide gel using Tris/glycine running buffer (192 mM glycine, 25 mM Tris, pH 8.3) for 1 h at 25 °C. The gels were stained with R250 coomassie-blue stain in order to visualize the protein.

Bioinformatics

Sequence homology searches against nonredundant sequence data banks were carried out using PSI Blast (http://blast.ncbi.nlm). Multiple alignments were carried out using COBALT (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/tools/cobalt/).

Steady-state Kinetics

Steady-state kinetic constant determinations were carried out at 25 °C using reaction solutions initially containing GmhB, varying concentrations of D-glycero-D-manno-heptose-1,7-bisphosphate (0.5–5 Km), 1 mM MgCl2, 0.2 mM 2-amino-6-mercapto-7-methylpurine ribonucleoside, 1U purine nucleoside phosphorylase and 50 mM Tris-HCl (pH 7.5). Reactions were continuously monitored for phosphate formation at 360 nm (Δε = 11 mM−1 cm−1). Initial velocity data were fitted to the equation: V0 = Vmax [S] / (Km + [S]) with the KinetAsyst I program. The kcat value was calculated from Vmax and [E] according to the equation kcat = Vmax /[E], where [E] is the enzyme concentration.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

The Structure of GmhB

The E. coli and B. bronchiseptica GmhB were shown by size-exclusion column chromatography to have native molecular masses of ~16 kDa and ~20 kDa, respectively, which by comparison to the respective calculated masses of 21, 294 Da and 19,035 Da, indicate that both enzymes exist as monomers in solution.

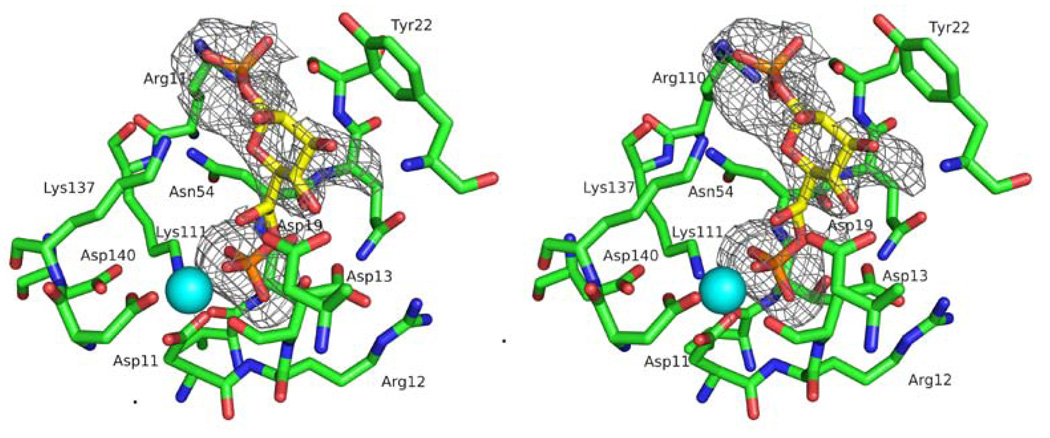

X-ray structures were determined for E. coli GmhB in the apo form (no Mg2+ bound despite the inclusion of 5 mM MgCl2 in the crystallization solution) at 1.6 Å resolution, complexed with Mg2+ and orthophosphate at 1.8 Å resolution, and complexed with Mg2+ and D-glycero-D-manno-heptose-1β,7-bisphosphate at 2.2 Å resolution. In addition, the structure of B. bronchiseptica GmhB bound to Mg2+ and orthophosphate was determined to 1.7 Å resolution. Data collection and refinement statistics for each of the structures are reported in Table 1. All four structures reveal a Zn2+ bound at the predicted Zn2+-binding loop as evidenced by strong X-ray fluorescence at the peak wavelength (Kedge) of Zn2+. The Zn2+ apparently co-purified with the protein as no Zn2+ was added at any stage of the purification or during the crystallization procedure.

The crystalline E. coli GmhB/Mg2+/phosphate complex was formed by soaking crystals of the apo enzyme in a buffered solution of MgCl2 and imidodiphosphate. Activity assays revealed that E. coli GmhB hydrolyzes imidodiphosphate at a slow but detectable rate (estimated turnover rate is ~ 1 × 10−4 s−1). Thus, the phosphate ligand observed in the X-ray crystal structure was generated in situ. In a similar fashion, the crystalline B. bronchiseptica GmhB/Mg2+/phosphate complex was obtained by co-crystallization of the enzyme with MgCl2 and fructose 1,6-bisphosphate. The fructose 1,6-bisphosphate is a slow substrate (kcat = 0.55 ± 0.01 s−1, Km = 680 ± 10 µM) and thus the phosphate was generated by catalyzed hydrolysis of the fructose 1,6-bisphosphate. The crystalline E. coli GmhB/Mg2+/D-glycero-D-manno-heptose-1β,7-bisphosphate complex was formed by soaking crystals of the apo enzyme with MgCl2 plus a 1:1 mixture of D-glycero-D-manno-heptose-1β,7-bisphosphate and D-glycero-D-manno-heptose-1β-phosphate (Fig. 3).2

Figure 3.

Stereoview of the active site of the E.coli GmhB bound complexed with Mg2+ (cyan sphere) and D-glycero-D-manno-heptose 1β,7-bisphosphate. The simulated-annealing Fo-Fc electron density omit map (contoured at 2σ) is shown as gray cages).

The E. coli and B. bronchiseptica GmhB structures reveal a single subunit protein, consistent with the molecular mass determined for the native enzymes in solution. The GmhB orthologs (Fig. 4) possess the HAD enzyme superfamily catalytic domain and, as was predicted from the sequence alignment data, they lack a cap domain. The GmhB backbone trace closely resembles that of the E. coli HisB histidinol-phosphate phosphatase domain (Fig. 2) with an rmsd between common Cα carbons of 1.86 Å. Superposition of the apo E. coli GmhB structure with the liganded structures (not shown) showed that ligand binding does not induce global or local conformational changes. The only significant change observed is the rotomer conformation of the Asp 11 side chain, which in the liganded structure, coordinates to the Mg2+ cofactor.

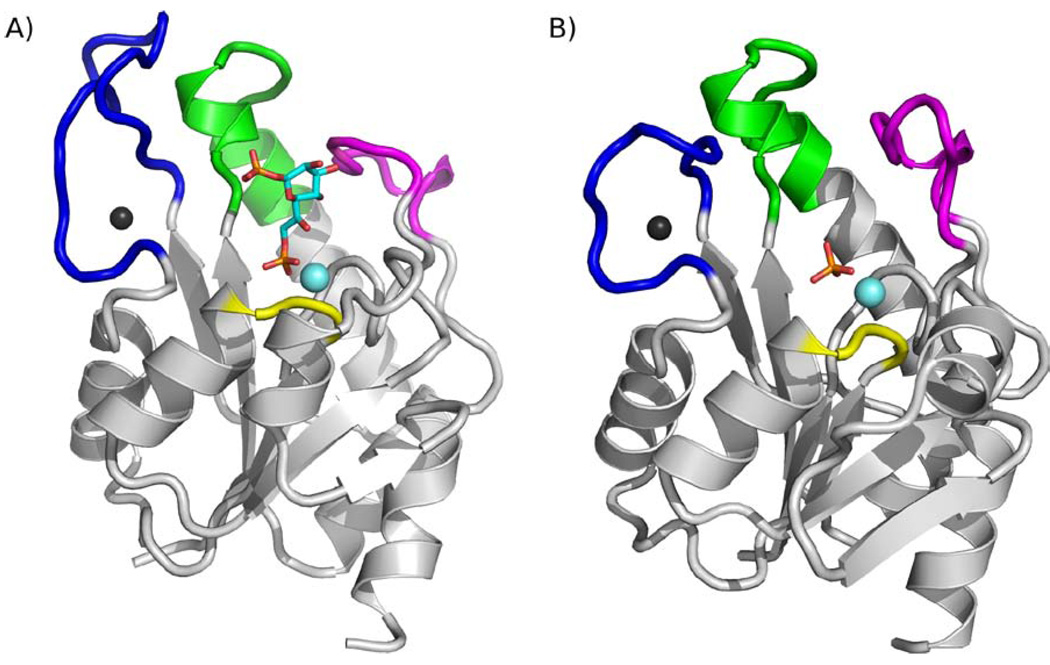

Figure 4.

A) Ribbon diagram of E. coli GmhB bound to Zn2+ and Mg2+ (black and cyan spheres) and the substrate and D-glycero-D-manno-heptose 1β,7-bisphosphate. The Zn2+-binding loop is colored blue, loop 2 green, loop 1 magenta and the Mg2+-binding loop yellow. B) Ribbon diagram of E. coli GmhB bound to Zn2+ and Mg2+ and the product orthophosphate. The loops are colored the same as Figure 2.

The Catalytic Scaffold

The catalytic scaffolds observed in the structures of the E. coli and B. bronchiseptica GmhB/Mg2+/phosphate product complexes (Fig. 5) comprise the Asp nucleophile (Asp11 and Asp7, in E. coli and B. bronchiseptica respectively), Asp acid/base (Asp13 and Asp9), Thr and Lys phosphoryl-binding groups (Thr53 and Thr50; Lys111 and Lys101), and the Asp ligand to the Mg2+ cofactor (Asp136 and Asp126). Together, this conserved constellation of residues comprises the phosphatase catalytic scaffold for the stabilization of the trigonal bipyramidal transition state (compare to Fig. 1). In addition, the residue which performs the role of positioning the Asp acid/base in all HAD phosphatases is present in the two GmhB orthologs as Asn17 (2.7 Å from Asp13) and Asn13 (2.9 Å from Asp9) (Fig. 5). The acid/base catalyst has been identified as critical for catalysis in HAD phosphatases(12). The essential role of this residue is also supported in GmhB as demonstrated by the finding that the E. coli GmhB D13A mutant is devoid of detectable activity toward the physiological substrate D-glycero-D-manno-heptose-1β,7-bisphosphate (Table 2).

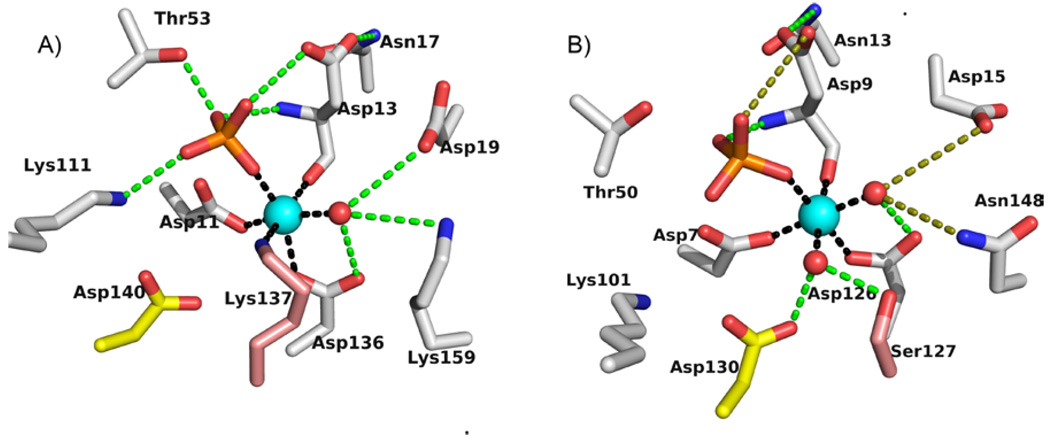

Figure 5.

The active sites from the structures of E. coli GmhB/Mg2+/phosphate (A) and B. bronchiseptica GmhB/Mg2+/phosphate complexes (B). Metal coordination (black), hydrogen bonds (within 3.5 Å; green), and long hydrogen bonds (3.6–3.9 Å; olive) are represented by dashed lines. The Mg2+ is a cyan sphere and water ligand(s) are red spheres. The paired yellow and salmon residues occupy homologous positions in the two active sites.

Table 2.

Steady-state kinetic constants for E. coli GmhB mutant catalyzed hydrolysis of the α and/or β anomer of D-glycerol-D-manno-heptose-1,7-bisphosphate in 50 mM Tris-HCl (pH 7.5, 25 °C) containing 1 mM MgCl2.

| GmhB | Substrate anomer | kcat (sec−1) | Km (µM) | kcat/Km (M−1 s−1) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Wild-type | β | 35.7 ± 0.2 | 5.0 ± 0.1 | 7 × 106 |

| Wild-type | α | 4.6 ± 0.1 | 67 ± 1 | 7 × 104 |

| D13A | β | < 10−4 | --- | ---- |

| K137A | β | 28.0 ± 0.5 | 39 ± 1 | 7 × 105 |

| R110A | β | 6.2 ± 0.1 | 181 ± 6 | 3 × 104 |

| R110A | α | < 10−4 | -- | --- |

| C109A | β | 0.34 ± 0.1 | 68 ± 4 | 5 × 103 |

| C109A | α | 0.057 ± 0.001 | 45 ± 2 | 1 × 103 |

| C107A | β | 0.63 ± 0.01 | 83 ± 4 | 8 × 103 |

| C107A | α | 0.042 ± 0.002 | 320 ± 20 | 1 × 10 |

| C92A | β | 0.63 ± 0.01 | 180 ± 6 | 3 × 104 |

| C92A | α | 0.0017 ± 0.0001 | 300 ± 20 | 5 |

The phosphate ligand in the E. coli GmhB/Mg2+/phosphate complex forms a coordination bond with Mg2+ (2.1 Å) and engages in hydrogen-bond interaction with the side chains of Thr53 (3.5 Å), Lys111 (2.5 Å) and Asp13 (3.4 Å) as well as the backbone amide NH of Asp13 (3.1 Å). The phosphate ligand of the B. bronchiseptica GmhB/Mg2+/phosphate complex forms a coordination bond with the Mg2+ (2.1 Å) and engages in hydrogen bond interaction with the side chains of Thr50 (3.6 Å) and the backbone amide NH of Asp9 (2.8 Å). The side chains of Lys101 (4.3 Å) and Asp9 (4.0 Å) do not form the expected hydrogen bonds with the phosphate ligand due to subtle differences in position of both the phosphate and side chains.

In phosphate complexes of HAD phosphatases(33–34), the six coordination sites of the Mg2+ cofactor are typically filled by two water ligands, one oxygen atom of the phosphate ligand, one oxygen atom from the Asp nucleophile carboxylate group, the backbone C=O of the Asp acid/base, and one oxygen atom from the carboxylate group of an Asp/Glu residue located on the Mg2+-binding loop. The structure of the Mg2+ center of the B. bronchiseptica GmhB/Mg2+/phosphate complex conforms to this model. Aside from the phosphate ligand, there are two water ligands (2.1 and 2.2 Å), the Asp7 carboxylate oxygen atom (2.2 Å), the Asp11 backbone carbonyl oxygen (2.1 Å) and the Asp126 carboxylate oxygen atom (2.0 Å) (Fig. 5). The Mg2+ center of the E. coli GmhB/Mg2+/phosphate complex on the other hand, is unusual in that one coordination position is occupied by the side chain nitrogen atom (2.4 Å) of a Lys residue (Lys137) adjacent to the Asp 136 (2.3 Å) ligand of the Mg2+-binding loop. The five coordination sites that remain are filled by a phosphate oxygen atom (2.0 Å), the Asp 11 carboxylate oxygen atom (2.1 Å), the Asp 13 backbone carbonyl oxygen (2.3 Å), and a water molecule (2.5 Å). The Lys137 residue is not stringently conserved among GmhB orthologs. In B. bronchiseptica GmhB, the corresponding residue is Ser127. As shown in Fig. 5, the Ser127 forms a hydrogen bond with the Mg2+ water ligand that assumes the same coordination position as the Lys137 in the E. coli GmhB/Mg2+/phosphate complex. In addition, the Lys137 does not coordinate to the Mg2+ in the E. coli GmhB Michaelis complex (vide infra), nor does it make a significant contribution to catalysis (Table 2).

Binding Site for the Substrate Leaving Group: Collaboration between Three Loop Extensions

The GmhB catalytic site is elaborated by three extended peptide inserts, which pack to form a concave, semicircular surface around the substrate leaving group (Fig. 6A). Together, with the bulky substrate-leaving group, the three inserts shield the catalytic site from solvent (as demonstrated by using the program Voidoo(35)). All three inserts project from the C-terminal end of the Rossmann-like fold. The first is an elongated loop, which follows the signature DxD catalytic motif containing the Asp nucleophile and Asp general acid/base residue. In the type C1 HAD phosphatases an α-helical cap domain is inserted at this position. The second insert is a helix-turn motif that follows the conserved Thr/Ser located at the terminus of β-strand 2. The third insert is the Zn2+-binding loop, which precedes the conserved catalytic Lys. In the C2 HAD phosphatases an α/β-fold cap domain is inserted at this position. Because the cap domains inserted in these positions provide substrate-binding residues(15), it is not unreasonable to expect that the three loops in GmhB might do the same.

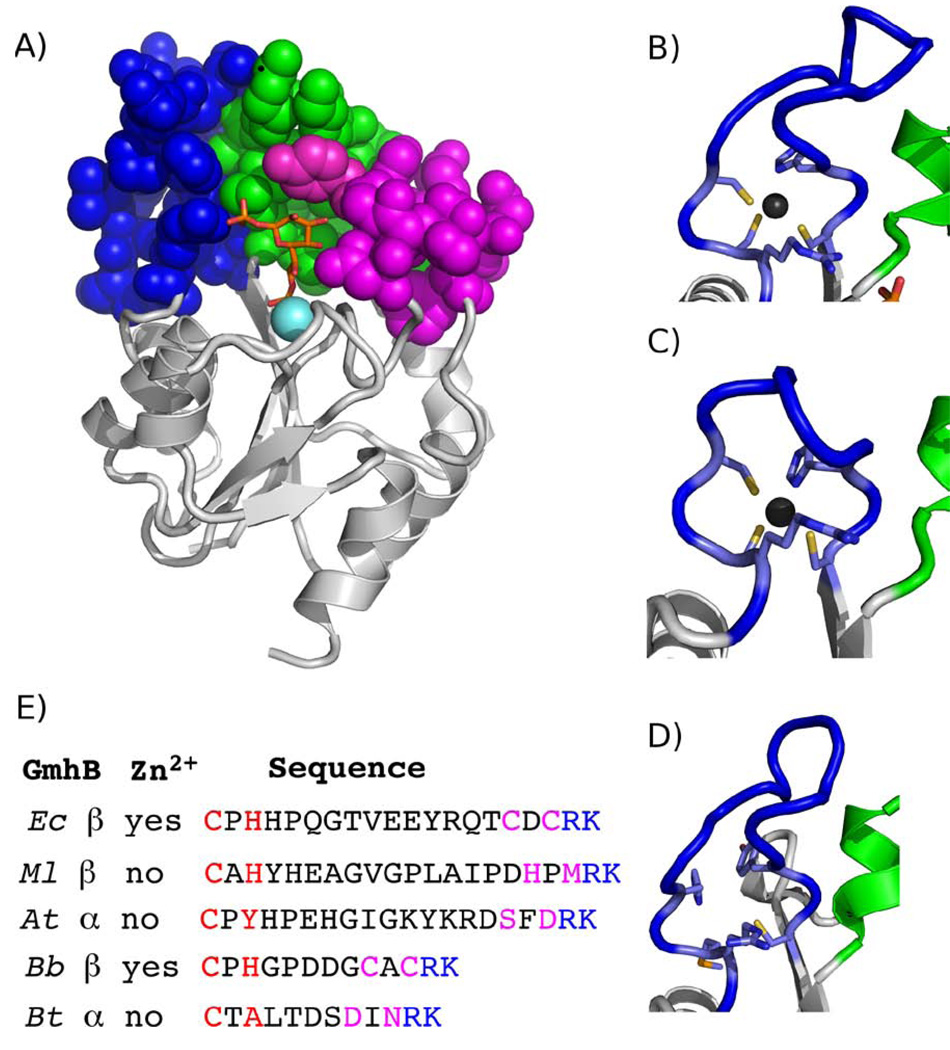

Figure 6.

A. The structure of the E. coli GmhB/Mg2+/D-glycero-D-manno-heptose 1β,7-bisphosphate complex. The Rossmann catalytic unit is depicted as ribbon (grey) with space-filling models for the Zn2+-binding loop (blue), loop 2 (green) and loop 1 (magenta). B, C, and D The Zn2+ (black sphere) bound loops of E. coli, B. bronchiseptica and the homologous, unliganded loop of M. loti GmhB. The Zn2+ ligands are shown as stick. The stringently conserved Arg is also depicted. E) Representative GmhB Zn2+-binding loops. Listed are the species (E. coli (Ec), M. loti (Ml), A. thermoaerophilus (At), B. bronchiseptica (Bb), B. thetaioatamicron (Bt)), preferred anomer (α or β) of D-glycero-D-manno-heptose 1,7-bisphosphate and the presence or absence of a Zn2+-binding motif. The first pair and second pairs of Zn2+ ligands are colored red and magenta, respectively, and the stringently conserved C(1) phosphate binding Arg and catalytic Lys residues are colored blue.

The Zn2-binding loop

The Zn2+-binding loops (Fig. 6B–D) of E. coli and B. bronchiseptica GmhB possesses a classical CxH(x)nCxC motif that coordinates the Zn2+ with square planar geometry. The structure of the E. coli GmhB/Mg2+/D-glycero-D-manno-heptose-1β,7-bisphosphate complex shows that the Zn2+ does not interact with the substrate and therefore, that it does not directly participate in catalysis. Our first impression was that the Zn2+ functions to stabilize the loop conformation. Consistent with this model was the finding that Ala replacement of any one of the four Zn2+ ligands of E. coli GmhB is detrimental. The His94Ala mutant proved to be insoluble, and the three Cys mutants which were soluble, displayed reduced catalytic efficiencies towards catalyzed hydrolysis of the α and β-anomers of D-glycero-l-D-manno-heptose-1,7-bisphosphate (Table 2).

Examination of the multiple alignment of GmhB sequences (Fig. SI1), however revealed the unexpected; the Zn2+-binding loop sequence is not conserved. Moreover, for a significant fraction of the GmhB orthologs (~10 %) two or more of the Zn2+ ligands of the CxH(x)nCxC consensus sequence are absent, which is likely to eliminate Zn2+ binding to the loop. In addition, the number of residues that separate the two pairs of Zn2+ ligands varies from 4 for the “short loop” to 12–14 for the long loop (Fig. 6). The E. coli GmhB provides an example of the CxH(x)nCxC long loop (n = 12), the B. bronchiseptica GmhB and Bacteriodes thetaioatamicron GmhB provide examples of the CxH(x)nCxC short loop (n = 4), whereas the Aneurinibacillus thermoaerophilus GmhB (CxP(x)12SxD) and the Mesorhizobium loti GmhB (CxY(x)14HxM) provide examples of the long loop, both of which have lost the capacity for Zn2+ binding. Each of these GmhB orthologs has been shown by in vitro kinetic analysis to be an effective catalysts of D-glycero-D-manno-heptose-1,7-bisphosphate hydrolysis. The structure of the M. loti GmhB (PDB ID 2O2X) provides a snapshot of the “empty” loop (Fig. 6). The loop is ordered and in fact, the B-factors for loop residues do not differ (relative to the average B-factors of the core) from those of the E. coli and B. bronchiseptica GmhB loop residues. Furthermore, the conformation of the M. loti GmhB loop is similar to that of the long, Zn2+-bound loop of the E. coli GmhB (Fig. 6). Examination of the structure of the M. loti GmhB demonstrated a possible structural feature for stabilization of the loop in the absence of the Zn2+ binding motif, namely, the presence of an N-terminal extension (residues 15–21) which forms an additional β-strand antiparallel to that from which the insert extends. However, inspection of the alignment of GmhB orthologs (Fig. SI1) revealed that no correlation exists between the presence and absence of an extended N-terminus and the presence or absence of a Zn2+-binding site. Thus, the structural significance of the presence of Zn2+ in some GhmB (or HisB, vide infra) orthologs, and its absence in others, is not known.

The finding that the GmhB loop exists in either a “no Zn2+ or a “Zn2+-bound” form prompted the examination of aligned HisB sequences (Fig. SI2). Whereas the HisB orthologs in Proteobacteria (the E. coli HisB is pictured in Fig. 2) contain the Zn2+-binding site, those in Bacterioidetes do not. Thus, both loop types are present in both subfamilies.

Given that Zn2+-binding is not a determinant of catalysis, an alternate role that the Zn2+ might perform was considered, leading to the experimental interrogation of DNA complexation by the E. coli and B. bronchiseptica GmhB. The Zn2+-finger is a common DNA binding motif utilized by transcriptional factors. Although the GmhB Zn2+-binding loop bares limited resemblance to the Zn2+ finger, it nevertheless seemed prudent to rule out DNA binding as a possible function. A standard DNA gel-shift assay (described in Materials and Methods) using “generic” calf-thymus DNA showed no indication of DNA binding. At this point in time the origin and function (if any) of the Zn2+-binding motif remains undefined.

The Zn2+-binding loop, with or without Zn2+, contributes to the sequestration of the substrate. In addition, a stringently conserved Arg residue (Fig SI1) is positioned at the base of the loop, in between the CxH(x)nCxC motif and the catalytic Lys (viz. CxH(x)nCxCRK, Fig. 6). The structure of the E. coli GmhB/Mg2+/D-glycero-D-manno-heptose-1β,7-bisphosphate complex suggests that the Arg contributes to substrate recognition by binding the C(1)phosphate (Fig. 3 and 7). Replacement of the E. coli GmhB Arg110 with Ala resulted in a significant reduction in the catalytic efficiency of hydrolysis of the physiological substrate D-glycerol-D-manno-heptose-1β,7-bisphosphate, reducing kcat 6-fold and increasing Km 36-fold, such that kcat/Km was reduced by 200-fold (Table 2). On the other hand, the Arg110Ala mutant showed no detectable activity towards D-glycerol-D-manno-heptose-1α,7-bisphosphate, which reveals a dramatic reduction in catalytic efficiency compared to the activity of the wild-type enzyme (kcat/Km = 7 × 104 M−1 s−1; Table 2). This finding suggests that the Arg plays a critical role in preserving catalytic activity towards the α-anomer. This residue might be especially important for the GmhB orthologs that function in the D-glycero-D-manno-heptose-1α-GDP pathway, because their physiological substrate is the α-anomer. In principle, the orientation of the Arg can be directed by the backbone conformation, and it by the adjacent Zn2+-binding site. This raised the possibility that the Zn2+-binding site acts as anomeric specificity switch. However this model was eliminated by the finding that there is no correlation between anomeric specificity of the GmhB ortholog and whether or not it possesses a Zn2+-binding site (Fig. 6E).

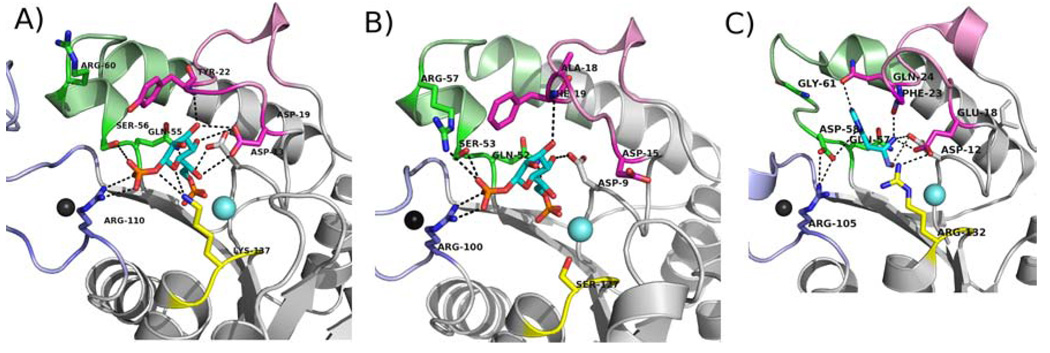

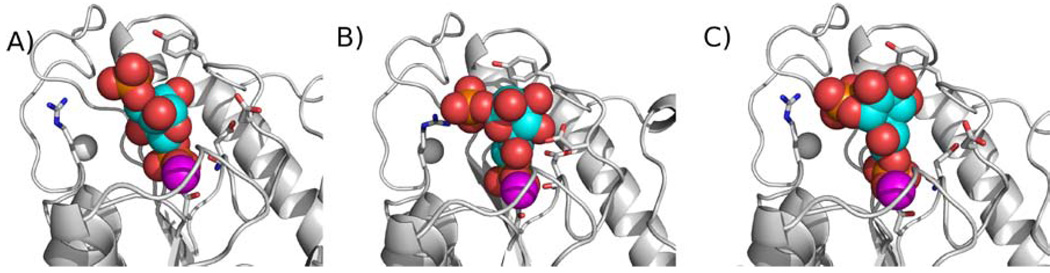

Figure 7.

Ribbon diagram of A) E. coli GmhB, B) B. bronchiseptica GmhB, and C) E. coli HisB with the substrate binding residues shown as sticks. Loops colored as in Figure 4.

Loops 1 and 2

Loops 1 (residues 18–30; Fig. 7) and 2 (residues 55–64; Fig. 7) are extensions from the core Rossmann-like fold that, as with the Zn2+ binding loop, are expected to provide the residues to bind the substrate leaving group. The structure of the E. coli GmhB/Mg2+/D-glycero-D-manno-heptose-1β,7-bisphosphate complex shows that the loop 1 Asp19 makes a hydrogen bond to the heptose C(3)OH (3.2 Å) and C(6) OH (3.6 Å). This residue is conserved in ~80% of all GmhB sequences and is conservatively replaced by Glu in all other GmhB orthologs. Thus, the function of this residue in binding the substrate-leaving group is conserved. Tyr22 makes a hydrogen bond to a water molecule which forms a hydrogen bond to the substrate C1 phosphoryl group. Moreover, the Tyr22 ring sits over the substrate leaving group, shielding the substrate leaving group. Tyr22 is conserved in ~80% of all GmhB sequences and in the remaining sequences it is replaced by a Phe. This finding is consistent with the interpretation that the major role of this Tyr/Phe and the adjoining Loop 1 residues is the shielding of the substrate leaving group and core active site from bulk solvent. There are no additional conserved residues on loop 1.

In loop 2, Ser 56 is found in the motif TNQS wherein the Thr53 is part of the HAD catalytic scaffold (vide infra). Ser56 makes two hydrogen bonds with the substrate C(1) phosphate (3.3 and 3.5 Å), while the adjacent Gln55 in the motif forms a hydrogen bond with the C1(O). Both the Ser56 and Gln55 are stringently conserved.

The Mg2+-binding loop

Although technically a component of the catalytic scaffold, the E. coli GmhB Mg2+-binding loop (Fig. 6) does contribute Lys137 that forms a hydrogen bond with to substrate C(1)phosphate (Fig. 7). However, the residue is not stringently conserved (Fig. 7; Fig. SI1), and furthermore, its replacement with Ala results in only a small reduction in catalytic efficiency (Table 2).

Substrate Specificity

E. coli GmhB is highly specific for D-glycero-D-manno-heptose-1,7-bisphosphate, it shows a 100 : 1 preference for the β-anomer over the α-anomer, it removes the C(7)phosphate and not the C(1)phosphate, and it does not hydrolyze the reaction product, D-glycero-D-manno-heptose-1-phosphate(25). In order to gain insight into the structural basis for this specificity, the structure of the E. coli GmhB/Mg2+/D-glycero-D-manno-heptose-1β,7-bisphosphate complex was used to generate a model in which the D-glycero-D-manno-heptose-1β,7-bisphosphate ligand is docked into the active site, in the reverse orientation, such that the C(1)phosphate rather than the C(7)phosphate is positioned for Mg2+ coordination and in-line attack by the Asp nucleophile (Fig. 8). In general, models are not sufficiently accurate to predict the small changes in orientations in interacting groups that can result in large changes in transition state structure and energy. However, in the present case, the comparison of the experimentally observed substrate complex (Fig. 8) vs. the substrate docked in the reverse orientation (Fig. 8) clearly identifies a major effect that, independent of the more subtle orientation effects, is likely to preclude hydrolysis of the C(1) phosphate. Specifically, in the reverse orientation, the leaving group does not have the correct shape to seal the active site entrance, and thus the electrostatic stabilization of the transition state is likely to be impaired by water molecules that can solvate the catalytic site. In contrast, the model of the D-glycero-D-manno-heptose-1α,7-bisphosphate docked in the catalytic orientation (Fig. 8) predicts that the solvent seal is in place. In addition, an alteration in ring pucker brings the C(1)phosphate of the α-anomer into position to form a salt bridge with Arg110. The 100 : 1 anomeric preference observed for the E. coli GmhB is likely to be determined by subtle orientation effects, which the model cannot predict.

Figure 8.

E. coli GmhB A) modeled with D-glycero-D-manno-heptose 1β,7-bisphosphate (space filling) bound in the reverse orientation (with the C(1)phosphate in the “transferring position”) B) in the orientation experimentally determined, and C) modelled with the α-anomer bound in the correct orientation (with C(7)phosphate in the “transferring position”) Note that the energy minimization used in generating the two models (A and C) altered the side chain conformations of some active site residues)

Divergence of the HisB Histidinol-Phosphate Phosphatase

We have shown(25) that histidinol-phosphate is not a substrate for E. coli GmhB. Although the GmhB substrate, D-glycero-D-manno-heptose 1,7-bisphosphate, was not tested for substrate activity with E. coli HisB, the reported absence of activity towards other phosphate ester metabolites indicates that the histidinol-phosphate phosphatase is not promiscuous(24). Thus, whereas the two sequences share 34% identity, they do not share substrates. In order to identify the structural elements for the substrate specialization that define the respective biochemical functions of GmhB and histidinolphosphate phosphatase, the structures of these two enzymes were compared, within the context of the residue conservation defined by multiple sequence alignments. Accordingly, the E. coli histidinol-phosphate phosphatase domain of the HisB fusion protein was used as query in a Blast search of the nonredundant protein sequence database. The sequences were aligned and curated to remove sequences that did not encode HisB (Fig. SI2). An analogous procedure was carried out to create the multiple sequence alignment of the GhmB homologs identified by Blast searches with the E. coli and M. loti GmhB sequences serving as query (Fig. SI1). No evidence for a “stand alone” HAD family histidinol-phosphate phosphatase was found. Likewise, there was no indication that a homolog possessing a novel catalytic activity is found among the GmhB sequences.

The respective sequence families provide insight into the biological range of HisB and GmhB, which agrees with and expands upon an earlier report(36). The HisB is primarily found in bacterial species of the gamma subdivision of Proteobacter, yet it is also found in numerous species of the Phylum Bacteroidetes/Chlorobi. HisB is believed to have evolved within the gamma subdivision of Proteobacter following its split from the beta division, and is thus a relatively new enzyme(36). A likely scenario is that the GmhB ancestor gene underwent duplication within a gamma subdivision bacterium, and the extra copy evolved to the HisB histidinol-phosphate phosphatase gene. The HisB gene was most probably acquired by Bacteroides via horizontal gene transfer. GmhB has a much greater biological range, which includes a variety of species from each Phylum of Bacteria as well as some species of Archaea. The HisB histidinol-phosphate phosphatase might thus be viewed as an adaptation of the GmhB to a novel biochemical niche (viz. the histidine biosynthetic pathway) within in a small biological sector.

The GmhB sequences have diverged to ~30% similarity and the HisB histidinol-phosphate phosphatase sequences have diverged to ~40% similarity. The two alignments are therefore reliable for use in distinguishing stringently conserved residues. First, it is noteworthy that the Arg110 residue in the E. coli GmhB Zn2+-binding loop, which plays an important role in substrate recognition (vide supra), is stringently conserved among the histidinol-phosphate phosphatase domains of HisB. In E. coli HisB, the Arg105 residue does not bind the substrate, rather it forms a hydrogen bond with an Asp residue of loop 2 (Fig. 7). The E. coli HisB Asp58 residue is stringently conserved in the position that corresponds to the E. coli GmhB Ser56 (Fig. 7) that, like the Arg residue, binds the substrate C(1)phosphate. The counterpart to the stringently conserved sequence motif of GmhB “TNQS” is the HisB TNQD motif (where T is the catalytic Thr53 in E. coli GmhB that is conservatively substituted with Ser in some GmhB orthologs (Fig 5) and Q is the Gln55 in E. coli that forms a long hydrogen bond (3.9 Å) to the substrate C(1)O (not shown). The switch from Ser to Asp allows a clear distinction to be made between GmhB and histidinol-phosphate phosphatase sequences. In the E. coli HisB structure the Asp58 of the TNQD motif forms a long hydrogen bond to the N1H of the histidinol-phosphate ligand and an ion pair with the Zn2+ binding loop Arg105 (Fig. 7).

In the E. coli HisB structure, the stringently conserved residues Gln24 and Glu18 (of loop 1) engage the N3 and C(2)NH3+ of the histidinol ligand in hydrogen bond formation. The homologous residues in E. coli GmhB, Tyr22 and Asp13 function in the respective roles of substrate leaving group desolvation and substrate binding (Fig. 7). The HisB Glu18 forms an ion pair with the catalytic scaffold Arg132, yet neither it, nor its E. coli GmhB counterpart, Lys137 (vide supra) are fully conserved.

Summary and Conclusion

Historically, two of the first capless members of the HAD family to be examined structurally were T4 polynucleotide kinase(21) and magnesium dependent phosphatase-1(19). Although these proteins have active sites that are completely solvent exposed, their large macromolecular substrates (t-RNA and protein, respectively) are expected to act like a cap by binding and protecting the phosphoryl transfer site from bulk solvent. Later, the capless HAD phosphatases, 2-keto-3-deoxy-octulosonate-8-phosphate (KDO-8-P) phosphatase(37–38) and 2-keto-3-deoxy-D-glycero-D-galactonononate-9-phosphate (KDN-9-P) phosphatase(23) were discovered to efficiently and specifically hydrolyze their respective (small molecule) substrates by recruiting a second subunit to act as a “cap” to the active site of the first subunit. The tetramerization of these two enzymes is mediated by a short peptide insert to the Rossmann-like fold at the position corresponding to cap domain of the C1 HADS (Fig. 1).

GmhB provides a unique solution to the problem of substrate discrimination in the capless HAD phosphatases. The GmhB structures show that the catalytic site is elaborated by three loops that form a concave, semicircular surface around the substrate-leaving group. One of the three loops binds Zn2+ in some but not all GmhB orthologs. Each of the three loops position stringently conserved residues that engage in hydrogen bond interaction with the substrate-leaving group, D-glycero-D-manno-heptose 1-phosphate. GmhB and the histidinol-phosphate phosphatase domain of HisB share the same design, yet through selective residue usage on the three substrate-recognition loops, they have achieved unique substrate specificity, and thus novel biochemical function.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

We thank Dr. Mirek Cygler and Dr. Steven Almo for providing the coordinates of HisB and Q8A5V9, respectively, prior to publication.

Footnotes

This work was supported by NIH Grant GM61099 to K.N.A and D.D.-M. Financial support for beamlines X12B, X25C and X29 at Brookhaven National Laboratory comes principally from the Offices of Biological and Environmental Research and of Basic Energy Sciences of the US Department of Energy and the National Center for Research Resources of the National Institutes of Health.

Coordinates for the X-ray structures of Bordatella bronchiseptica D-glycero-D-manno-heptose 1,7-bisphosphate phosphatase complexed with Mg2+ and phosphate, and for E. coli D-glycero-D-manno-heptose 1,7-bisphosphate phosphatase in the apo form and complexed with Mg2+ plus phosphate or D-glycero-D-manno-heptose 1β,7-bisphosphate have been deposited in the Protein Data Bank with accession codes 3L8H, 3L8E, 3L8F, and 3L8G, respectively.

Abbreviations used are: H1β,7bisP; -D-glycero-D-manno-heptose-1 β,7-bisphosphate, H1α,7bisP; D-glycero-D-manno-heptose-1α,7-bisphosphate; D-glycero-D-manno-heptose 1,7-bisphosphate phosphatase, GmhB; Haloalkanoic Acid Dehalogenase, HAD; bifunctional histidinol-phosphate phosphatase/ imidazole-glycerol-phosphate dehydratase, HisB selenomethionine, SeMet; 2-keto-3-deoxy-octulosonate-8-phosphate, KDOP-8-P; 2-keto-3-deoxy-D-glycero-D-galactonononate-9-phosphate, KDN-9-P; DTT, dithiothreitol.

Structures of enzymes bound to substrates Michaelis complexes have been frequently observed by X-ray crystallography (1–2). This is seemingly in conflict with data showing that enzymes are active in the crystalline form (3–4). However, these data can be reconciled by considering the fact that the internal equilibria may differ in the crystalline enzyme versus enzyme in the solution. Becuase crystal structures generally do not detect species in low abundance (<20%) a shift in substrate : product equilibrium to 5:1 would lead to observation of a substrate bound structure. Alternatively, dynamics of the protein are expected to be constrained in the crystal lattice compared to solution. To the extent that the enzyme transition state is formed by the instantaneous and optimal alignment of functional groups at the catalytic site during protein dynamic motion (5) the crystalline enzyme may not have sufficient mobility to attain the catalytic conformation (may not achieve sufficient energy of activation). The resulting complex does not represent an "off path" state but rather one on the reaction coordinate where collapse to the transition state may not proceed. In covalent catalysis as is observed in HAD members, this may also include the case where the nucleophile does not reach the near attack conformation (6). Notably, this scenario is not similar to one in which a large conformational change such as loop closure or domain swiveling is precluded by the crystal lattice becuase the active site in such a complex would not be that of the active form in terms of bulk solvent exposure and/or amino acid composition.

At first glance this conclusion might appear to be inconsistent with the observed reduction in catalytic efficiency in the E. coli GmhB Zn2+ binding loop mutants (Table 2). However, this is not the case as the alteration of a structural motif by mutation is frequently destabilizing to the native conformation enzyme and often manifested in decreased catalytic efficiency. In this case, removal of one of the four Zn2+ ligands might result in misfolding (as appears to be the case for the H94A mutant which is insoluble) or destabilization of the native conformation as the Zn2+ ion incorporates a fourth ligand from solvent, or elsewhere in the protein.

Supporting Information Available

Alignment of representative GmhB and HisB sequences. This material is available free of charge via the Internet at ://pubs.acs.org.

References

- 1.Heine A, DeSantis G, Luz JG, Mitchell M, Wong CH, Wilson IA. Observation of covalent intermediates in an enzyme mechanism at atomic resolution. Science. 2001;294:369–374. doi: 10.1126/science.1063601. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Dalby A, Dauter Z, Littlechild JA. Crystal structure of human muscle aldolase complexed with fructose 1,6-bisphosphate: mechanistic implications. Protein Sci. 1999;8:291–297. doi: 10.1110/ps.8.2.291. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Sygusch J, Beaudry D. Catalytic activity of rabbit skeletal muscle aldolase in the crystalline state. J Biol Chem. 1984;259:10222–10227. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Schlichting I, Chu K. Trapping intermediates in the crystal: ligand binding to myoglobin. Curr Opin Struct Biol. 2000;10:744–752. doi: 10.1016/s0959-440x(00)00158-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Schramm VL. Enzymatic transition states: thermodynamics, dynamics and analogue design. Arch Biochem Biophys. 2005;433:13–26. doi: 10.1016/j.abb.2004.08.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Petrek M, Otyepka M, Banas P, Kosinova P, Koca J, Damborsky J. CAVER: a new tool to explore routes from protein clefts, pockets and cavities. BMC Bioinformatics. 2006;7:316. doi: 10.1186/1471-2105-7-316. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Collet JF, van Schaftingen E, Stroobant V. A new family of phosphotransferases related to P-type ATPases. Trends Biochem Sci. 1998;23:284. doi: 10.1016/s0968-0004(98)01252-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Koonin EV, Tatusov RL. Computer Analysis of Bacterial Haloacid Dehalogenases Defines a Large Superfamily of Hydrolases with Diverse Specificity: Application of an Iterative Approach to Database Search. Journal of Molecular Biology. 1994;244:125–132. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1994.1711. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Allen KN, Dunaway-Mariano D. Phosphoryl group transfer: evolution of a catalytic scaffold. Trends Biochem Sci. 2004;29:495–503. doi: 10.1016/j.tibs.2004.07.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Smith CA, Rayment I. X-ray structure of the magnesium(II).ADP.vanadate complex of the Dictyostelium discoideum myosin motor domain to 1.9 A resolution. Biochemistry. 1996;35:5404–5417. doi: 10.1021/bi952633+. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wang W, Cho HS, Kim R, Jancarik J, Yokota H, Nguyen HH, Grigoriev IV, Wemmer DE, Kim SH. Structural characterization of the reaction pathway in phosphoserine phosphatase: crystallographic "snapshots" of intermediate states. J Mol Biol. 2002;319:421–431. doi: 10.1016/S0022-2836(02)00324-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lu Z, Dunaway-Mariano D, Allen KN. The catalytic scaffold of the haloalkanoic acid dehalogenase enzyme superfamily acts as a mold for the trigonal bipyramidal transition state. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2008;105:5687–5692. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0710800105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Allen KN, Dunaway-Mariano D. Markers of fitness in a successful enzyme superfamily. Curr Opin Struct Biol in press. 2009 doi: 10.1016/j.sbi.2009.09.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Burroughs AM, Allen KN, Dunaway-Mariano D, Aravind L. Evolutionary genomics of the HAD superfamily: understanding the structural adaptations and catalytic diversity in a superfamily of phosphoesterases and allied enzymes. J Mol Biol. 2006;361:1003–1034. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2006.06.049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lahiri SD, Zhang G, Dai J, Dunaway-Mariano D, Allen KN. Analysis of the substrate specificity loop of the HAD superfamily cap domain. Biochemistry. 2004;43:2812–2820. doi: 10.1021/bi0356810. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Zhang G, Dai J, Wang L, Dunaway-Mariano D, Tremblay LW, Allen KN. Catalytic cycling in beta-phosphoglucomutase: a kinetic and structural analysis. Biochemistry. 2005;44:9404–9416. doi: 10.1021/bi050558p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kim HY, Heo YS, Kim JH, Park MH, Moon J, Kim E, Kwon D, Yoon J, Shin D, Jeong EJ, Park SY, Lee TG, Jeon YH, Ro S, Cho JM, Hwang KY. Molecular basis for the local conformational rearrangement of human phosphoserine phosphatase. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:46651–46658. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M204866200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Dai J, Finci L, Zhang C, Lahiri S, Zhang G, Peisach E, Allen KN, Dunaway-Mariano D. Analysis of the structural determinants underlying discrimination between substrate and solvent in beta-phosphoglucomutase catalysis. Biochemistry. 2009;48:1984–1995. doi: 10.1021/bi801653r. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Peisach E, Selengut J, Dunaway-Mariano D, Allen KN. Structure of the Magnesium-Dependent Protein Tyrosine Phosphatase, MDP-1. Biochemistry. 2004;43:12770–12779. doi: 10.1021/bi0490688. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Peisach E, Wang L, Burroughs AM, Aravind L, Dunaway-Mariano D, Allen KN. The X-ray crystallographic structure and activity analysis of a Pseudomonas-specific subfamily of the HAD enzyme superfamily evidences a novel biochemical function. Proteins. 2008;70:197–207. doi: 10.1002/prot.21583. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Galburt EA, Pelletier J, Wilson G, Stoddard BL. Structure of a tRNA repair enzyme and molecular biology workhorse: T4 polynucleotide kinase. Structure (Camb) 2002;10:1249–1260. doi: 10.1016/s0969-2126(02)00835-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Wu J, Woodard RW. Escherichia coli YrbI is 3-deoxy-D-mannooctulosonate 8-phosphate phosphatase. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:18117–18123. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M301983200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lu Z, Wang L, Dunaway-Mariano D, Allen KN. Structure-function analysis of 2-keto-3-deoxy-D-glycero-D-galactonononate-9-phosphate phosphatase defines specificity elements in type C0 haloalkanoate dehalogenase family members. J Biol Chem. 2009;284:1224–1233. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M807056200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Rangarajan ES, Proteau A, Wagner J, Hung MN, Matte A, Cygler M. Structural snapshots of Escherichia coli histidinol phosphate phosphatase along the reaction pathway. J Biol Chem. 2006;281:37930–37941. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M604916200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Wang L, Huang H, Nguyen H, Allen KN, Mariano PS, Dunaway-Mariano D. Divergence of Biochemical Function in the HAD Superfamily: D-Glycero-D-manno-heptose 1,7-bisphosphate Phosphatase, GmhB. Biochemistry companion manuscript. 2010 doi: 10.1021/bi902018y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Otwinowski Z, Minor W. Processing of X-ray Diffraction Data Collected in Oscillation Mode. Methods Enzymol. 1997;276:307–326. doi: 10.1016/S0076-6879(97)76066-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Vagin A, Teplyakov A. An approach to multi-copy search in molecular replacement. Acta Crystallogr D Biol Crystallogr 56 Pt 12. 2000:1622–1624. doi: 10.1107/s0907444900013780. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Collaborative Computational Project Number 4. Collaborative Computational Project Number 4 Acta Cryst. 1994;D50:760–768. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Emsley P, Cowtan K. Coot: model-building tools for molecular graphics. Acta Crystallogr D Biol Crystallogr 60. 2004:2126–2132. doi: 10.1107/S0907444904019158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Brünger AT, Adams PD, Clore GM, DeLano WL, Gros P, Grosse-Kunstleve RW, Jiang JS, Kuszewski J, Nilges M, Pannu NS, Read RJ, Rice LM, Simonson T, Warren GL. Crystallography & NMR system: A new software suite for macromolecular structure determination. Acta Crystallogr D Biol Crystallogr. 1998;54(Pt 5):905–921. doi: 10.1107/s0907444998003254. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Davis IW, Murray LW, Richardson JS, Richardson DC. MOLPROBITY: structure validation and all-atom contact analysis for nucleic acids and their complexes. Nucleic Acids Res. 2004;32:W615–W619. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkh398. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kerr LD. Electrophoretic mobility shift assay. Methods Enzymol. 1995;254:619–632. doi: 10.1016/0076-6879(95)54044-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Wang W, Kim R, Jancarik J, Yokota H, Kim SH. Crystal structure of phosphoserine phosphatase from Methanococcus jannaschii, a hyperthermophile, at 1.8 Å resolution. Structure (Camb) 2001;9:65–71. doi: 10.1016/s0969-2126(00)00558-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Rinaldo-Matthis A, Rampazzo C, Reichard P, Bianchi V, Nordlund P. Crystal structure of a human mitochondrial deoxyribonucleotidase. Nat. Struct. Biol. 2002;10:779–787. doi: 10.1038/nsb846. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kleywegt GJ, Jones TA. Detection, delineation, measurement and display of cavities in macromolecular structures. Acta Crystallogr D Biol Crystallogr. 1994;50:178–185. doi: 10.1107/S0907444993011333. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Brilli M, Fani R. Molecular evolution of hisB genes. J Mol Evol. 2004;58:225–237. doi: 10.1007/s00239-003-2547-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Parsons JF, Lim K, Tempczyk A, Krajewski W, Eisenstein E, Herzberg O. From structure to function: YrbI from Haemophilus influenzae (HI1679) is a phosphatase. Proteins. 2002;46:393–404. doi: 10.1002/prot.10057. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Biswas T, Yi L, Aggarwal P, Wu J, Rubin JR, Stuckey JA, Woodard RW, Tsodikov OV. The tail of KDSC: Conformational changes control the activity of a haloacid dehalogenase superfamily phosphatase. J Biol Chem. 2009 doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109.012278. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Lu Z, Dunaway-Mariano D, Allen KN. HAD superfamily phosphotransferase substrate diversification: structure and function analysis of HAD subclass IIB sugar phosphatase BT4131. Biochemistry. 2005;44:8684–8696. doi: 10.1021/bi050009j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.