Abstract

OBJECTIVE

Leptin acts via its receptor (LepRb) to signal the status of body energy stores. Leptin binding to LepRb initiates signaling by activating the associated Janus kinase 2 (Jak2) tyrosine kinase, which promotes the phosphorylation of tyrosine residues on the intracellular tail of LepRb. Two previously examined LepRb phosphorylation sites mediate several, but not all, aspects of leptin action, leading us to hypothesize that Jak2 signaling might contribute to leptin action independently of LepRb phosphorylation sites. We therefore determined the potential role in leptin action for signals that are activated by Jak2 independently of LepRb phosphorylation (Jak2-autonomous signals).

RESEARCH DESIGN AND METHODS

We inserted sequences encoding a truncated LepRb mutant (LepRbΔ65c, which activates Jak2 normally, but is devoid of other LepRb intracellular sequences) into the mouse Lepr locus. We examined the leptin-regulated physiology of the resulting Δ/Δ mice relative to LepRb-deficient db/db animals.

RESULTS

The Δ/Δ animals were similar to db/db animals in terms of energy homeostasis, neuroendocrine and immune function, and regulation of the hypothalamic arcuate nucleus, but demonstrated modest improvements in glucose homeostasis.

CONCLUSIONS

The ability of Jak2-autonomous LepRb signals to modulate glucose homeostasis in Δ/Δ animals suggests a role for these signals in leptin action. Because Jak2-autonomous LepRb signals fail to mediate most leptin action, however, signals from other LepRb intracellular sequences predominate.

Adipose tissue produces the hormone, leptin, in proportion to fat stores to communicate the status of long-term energy reserves to the brain and other organ systems (1–4). In addition to moderating food intake, adequate leptin levels permit the expenditure of energy on myriad processes including reproduction, growth, and immune responses, as well as regulating nutrient partitioning (4–6). Conversely, lack of leptin signaling due to null mutations of leptin (e.g., Lepob/ob mice) or the leptin receptor (LepR) (e.g., Leprdb/db mice) results in increased food intake in combination with reduced energy expenditure (and thus obesity), neuroendocrine dysfunction (including hypothyroidism, decreased growth, infertility), decreased immune function, and hyperglycemia and insulin insensitivity (1,7–9). Many of the effects of leptin are attributable to effects in the central nervous system, particularly in the hypothalamus, but leptin also appears to act directly on some other tissues (2,3).

Alternative splicing generates several integral-membrane LepR isoforms that possess identical extracellular, transmembrane, and membrane-proximal intracellular domains. LepR intracellular domains diverge beyond the first 29 intracellular amino acids, however, with the so-called “short” isoforms (e.g., LepRa) containing an additional 3–10 amino acids, and the single “long” isoforms (LepRb) containing a 300–amino acid intracellular tail (10). Like other type I cytokine receptors (11), LepRb (which is required for physiologic leptin action) contains no intrinsic enzymatic activity, but associates with and activates the Janus kinase 2 (Jak2) tyrosine kinase to mediate leptin signaling. The intracellular domain of LepRb possesses membrane-proximal Box1 and Box2 motifs, both of which are required for association with and regulation of Jak2; although LepRa and other short LepRs contain Box1, they lack Box2 and thus fail to bind and activate Jak2 under physiologic conditions (12).

Leptin stimulation promotes the autophosphorylation and activation of LepRb-associated Jak2, which phosphorylates three LepRb tyrosine residues (Tyr985, Tyr1077, and Tyr1138). Each LepRb tyrosine phosphorylation site recruits specific Src homology 2 (SH2) domain–containing effector proteins: Tyr985 recruits Src homology phosphatase-2 (SHP-2) and suppressor of cytokine signaling 3 and attenuates LepRb signaling, but does not appear to play other roles in leptin action in vivo (13–15). Tyr1077 recruits the latent transcription factor, signal transducer, and activator of transcription 5 (STAT5), and Tyr1138 recruits STAT3 (16–18). Mice in which LepRbS1138 (mutant for Tyr1138 and thus specifically unable to recruit STAT3) replaces endogenous LepRb exhibit hyperphagic obesity, with decreased energy expenditure, but increased growth, protection from diabetes, and preservation of several aspects of hypothalamic physiology (19–21). These results thus suggest roles for Tyr1077 and/or Jak2-dependent signals that are independent of LepRb tyrosine phosphorylation (“Jak2-autonomous signals”) in mediating Tyr985/Tyr1138-independent leptin actions. Although others have examined the effect of mutating all three LepRb tyrosine phosphorylation sites in mice (22), revealing potential tyrosine phosphorylation–independent roles for LepRb in leptin action, that study did not examine several aspects of leptin action and could not distinguish potential effects of nonphosphorylated LepRb motifs from effects due to LepRb/Jak2 interactions specifically.

RESEARCH DESIGN AND METHODS

Cell culture studies.

The plasmids pcDNA3LepRbΔ65 and pcDNA3LepRa were generated by mutagenesis of pcDNA3LepRb (23) using the QuikChange kit (Stratagene). The absence of adventitious mutations was confirmed by DNA sequencing for all plasmids. Cell culture, transfection, lysis, and immunoblotting were conducted as reported previously using αJak2(pY1007/8) from Cell Signaling Technology and αJak2 from our own laboratory (24). Leptin was the generous gift of Amylin Pharmaceuticals (La Jolla, CA).

Mouse model generation.

The targeting vector encoding LepRbΔ65 was generated by inserting a Stop codon (QuikChange kit) after the 65th intracellular amino acid of LepRb in the 5′ targeting arm in the pBluescript plasmid; this modified 5′-arm was subsequently subcloned into the previously described pPNT-derived targeting vector that contained the 3′ arm (19,25,26). The resulting construct was linearized and transfected into murine embryonic stem (ES) cells with selection of clones by the University of Michigan Transgenic Animal Model Facility. Correctly targeted clones were identified and confirmed with real-time PCR and Southern blotting as performed previously (15,21,26) and were injected into embryos for the generation of chimeras and the establishment of germ-line LeprΔ65/+ (Δ/+) animals. Δ/+ animals were intercrossed to generate +/+ and Δ/Δ mice for the determination of hypothalamic Lepr expression or were backcrossed onto the C57BL/6J background (The Jackson Laboratory) for six generations prior to intercrossing to generate +/+ and Δ/Δ animals for the collection of other data.

Experimental animals.

C57BL/6J wild-type, Lepob/+, and Leprdb/+ breeders were purchased from The Jackson Laboratory. All other animals and progeny from these purchased breeders were housed and bred in our colony and were cared for and used according to guidelines approved by the University of Michigan Committee on the Care and Use of Animals. After weaning, all mice were maintained on 5011 LabDiet chow. Mice were given ad libitum access to food and water unless otherwise noted. For body weight, food intake, glucose monitoring, and estrous monitoring, animals were weaned at 4 weeks and housed individually. Body weight and food intake were recorded weekly from 4 to 8 weeks. Whole venous blood from the tail vein was used to determine blood glucose (Ascensia Elite glucometer) and to obtain serum, which was frozen for later hormone measurement. A terminal bleed was also collected at the time of killing. Commercial ELISA kits were used to determine insulin (Crystal Chem), leptin (Crystal Chem), and C-peptide (Millipore) concentrations.

In females, vaginal lavage was used to assess estrous cycling daily from 4 to 8 weeks. Animals intended for glucose tolerance tests, insulin tolerance tests, and body composition were weaned at 4 weeks and group housed. Body composition was determined using an NMR Minispec LF90II scanner (Bruker Optics) in the University of Michigan Animal Phenotyping Core.

Analysis of hypothalamic RNA.

Hypothalami were isolated from ad libitum–fed mice and snap-frozen. Total RNA was isolated using Trizol RNA reagent (Invitrogen) and converted to cDNA using SuperScript reverse transcriptase (Invitrogen). For comparison of relative LepRb expression, total hypothalamic cDNA was subjected to PCR with LepRb-specific primers and subjected to gel electrophoresis (21). For determination of relative neuropeptide expression, total hypothalamic cDNA was subjected to automated fluorescent RT-PCR on an ABI Prism 7700 Sequence Detection System (Applied Biosystems) (21).

Immunologic cell analysis.

For counting total splenocytes and splenic T-cells, splenic T-cells were magnetically separated from the spleen by autoMACS (Miltenyi Biotech, Bergisch Gladbach, Germany) as previously described and counted by flow cytometry (27). For proliferation assays, T-cells were separated using CD90 microbeads, and 2 × 105 of these were incubated with 2 × 104 B6 bone marrow–derived dendritic cells for 48, 72, and 96 h. Cells were stimulated with soluble anti-CD3e (1 mg/ml). Incorporation of 3H-thymidine (1 μCi/well) by proliferating cells during the last 12 h of culture was measured.

Immunohistochemical analysis of hypothalamic brain sections.

+/+, db/+, and Δ/+ were intercrossed with heterozygous AgrpLacZ mice expressing LacZ from the Agrp locus (28,29) before recrossing to the parent Lepr strain to generate experimental animals. For immunohistochemical analysis, ad libitum–fed animals remained with food in the cage until the time of death. Perfusion and immunohistochemistry were performed as described (30).

RESULTS

LepRbΔ65 and gene targeting to generate LeprΔ65.

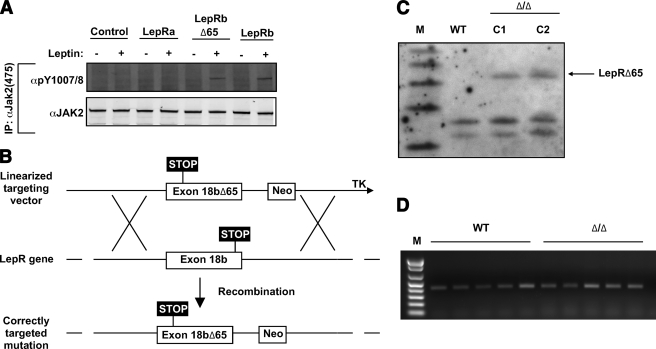

To examine physiologic signals generated by LepRb-associated Jak2 in the absence of LepRb tyrosine phosphorylation sites and other LepRb motifs (Jak2-autonomous signals), we used a COOH-terminal truncation mutant of LepRb (LepRbΔ65) that contains all motifs required for Jak2 association and regulation, but which is devoid of other intracellular LepRb sequences (12). Because we previously demonstrated the function of this mutant intracellular domain in the context of an erythropoietin receptor (extracellular domain)/LepRb (intracellular domain) chimera (12), we initially examined signaling by the truncated intracellular domain within the context of LepRbΔ65 in transfected 293 cells (Fig. 1A). Leptin stimulation promoted the phosphorylation of Jak2 on the activating Tyr1007/1008 sites in LepRbΔ65- and LepRb-expressing cells but not in LepRa-expressing or control cells (Fig. 1A), confirming that LepRb and LepRbΔ65, but not LepRa, contain the necessary sequences to mediate Jak2 activation in response to leptin.

FIG. 1.

Generation of mice expressing LepRbΔ65. A: HEK293 cells were transfected with plasmids encoding the indicated LepR isoforms, made quiescent overnight, incubated in the absence (−) or presence (+) of leptin (625 ng/ml) for 15 min before lysis, and immunoprecipitated with αJak2 (24). Immunoprecipitated proteins were resolved by SDS-PAGE, transferred to nitrocellulose, and immunoblotted with the indicated antibodies. The figures shown are typical of multiple independent experiments. B: Diagram of gene-targeting strategy to replace wild-type exon 18b with that encoding the COOH-terminally truncated LepRbΔ65. C: Southern blotting of control (wild-type) and correctly targeted (D/+, C1, C2) LeprΔ65 ES lines, using a Lepr-specific probe. M indicates marker lane. D: Image of gel electrophoresis of Lepr-specific RT-PCR products from hypothalamic mRNA of five wild-type and five Δ/Δ animals.

To understand the potential roles for Jak2-autonomous LepRb signals in leptin action, we used homologous recombination to replace the genomic Lepr with LeprΔ65 (henceforth referred to as the Δ allele, encoding LepRbΔ65) in mouse ES cells (Fig. 1B). Correctly targeted ES cell clones were confirmed by Southern blotting (Fig. 1C). This strategy mediates LepRbΔ65 expression from the native Lepr locus, ensuring correct patterns and levels of LepRbΔ65 expression, as previously for other homologously targeted LepRb alleles (15,21,26). Indeed, RT-PCR analysis of hypothalamic mRNA confirmed similar Lepr mRNA expression in homozygous Δ/Δ animals and wild-type animals (Fig. 1D). Prior to subsequent study, we backcrossed heterozygous Δ/+ animals to C57BL/6J mice for six generations to facilitate direct comparison with Leprdb/db (db/db) animals on this background.

Energy homeostasis in Δ/Δ mice.

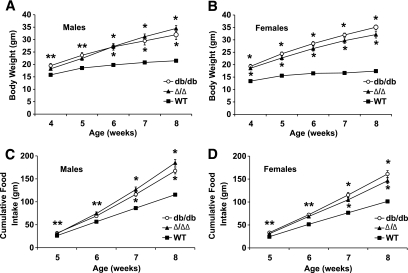

Because our previous analysis suggested some role for Tyr985/Tyr1138-independent LepRb signals in regulating energy balance, we initially examined parameters of energy homeostasis in Δ/Δ compared with db/db animals (15,19,21). We weaned and singly housed Δ/Δ, db/db, and control mice from 4 to 8 weeks of age for the longitudinal determination of body weight and food intake (Fig. 2A–D). Compared with age- and sex-matched db/db animals, Δ/Δ mice displayed similar body weights and food intake over the study period. Furthermore, age- and sex-matched Δ/Δ and db/db mice displayed similar proportions of fat and lean mass (Table 1), revealing that Δ/Δ and db/db mice are similarly obese. Core body temperature in Δ/Δ and db/db animals was also similarly reduced compared with control animals (Table 1). Thus, LepRbΔ65 fails to alter major parameters of energy homeostasis compared with entirely LepRb-deficient db/db mice, suggesting that Jak2-autonomous LepRb signals are not sufficient to modulate energy balance in mice.

FIG. 2.

Similar hyperphagia and obesity in Δ/Δ and db/db mice. Wild-type (■), db/db (○), and Δ/Δ (▴) mice of the indicated age (n = 8–10 per genotype) were weaned at 4 weeks and body weight (A and B) and food intake (C and D) were monitored weekly from 4 to 8 weeks of age. Food intake represents cumulative food intake over the time course. Data are plotted as means ± SEM. *P < 0.05 compared with wild type (WT) by one-way ANOVA and Tukey post-test.

TABLE 1.

Phenotypic data for mice expressing mutant LepRb

| Genotype | Wild type | db/db | Δ/Δ |

|---|---|---|---|

| Fat content (%) | |||

| Male | 6.0 ± 0.7 (10) | 47.0 ± 1.1* (8) | 47.8 ± 0.9* (8) |

| Female | 6.4 ± 0.5 (8) | 51.0 ± 0.9* (8) | 54.1 ± 0.7* (11) |

| Lean content (%) | |||

| Male | 80.0 ± 0.4 (10) | 43.7 ± 1.1* (8) | 42.6 ± 0.8* (8) |

| Female | 76.0 ± 3.0 (8) | 39.5 ± 0.7* (8) | 37.5 ± 0.6* (10) |

| Body temperature (°C) | |||

| Male | 34.6 ± 0.2 (10) | 33.0 ± 0.2* (9) | 33.4 ± 0.2* (8) |

| Female | 34.4 ± 0.3 (8) | 33.8 ± 0.2 (9) | 33.5 ± 0.3 (12) |

| Snout-anus length (mm) | |||

| Male | 88.5 ± 0.8 (9) | 82.6 ± 2.7* (8) | 83.0 ± 1.0* (9) |

| Femur length (mm) | |||

| Male | 13.9 ± 0.1 (9) | 11.8 ± 0.1* (8) | 12.0 ± 0.1* (9) |

| Femur mass (mg) | |||

| Male | 42.4 ± 0.6 (9) | 34.8 ± 0.8* (8) | 35.3 ± 0.9* (9) |

Fat and lean content were determined at 10 weeks and are expressed as a percentage of body weight. Body temperature was determined at 11 weeks. Snout-anus length, femur length, and femur weight were determined at 9 weeks. Data are means ± SE;

*P < 0.05 compared with wild type by Student unpaired, two-tailed t test. Sample size noted in parentheses.

Linear growth and reproductive function in Δ/Δ mice.

In addition to modulating metabolic energy expenditure, leptin action permits the use of resources on energy-intensive neuroendocrine processes, such as growth and reproduction. Whereas db/db and ob/ob animals that are devoid of leptin action thus display decreased linear growth and infertility, animals lacking Tyr985 or Tyr1138 of LepRb display normal or enhanced linear growth and preserved reproductive function, suggesting a role for other LepRb signals in mediating these leptin actions (15,19,21). Similar to db/db mice, Δ/Δ males displayed decreased snout-anus length and femur length relative to control animals (Table 1), however, suggesting the inability of Jak2-autonomous LepRb signals to mediate linear growth in the absence of other LepRb signals.

To determine the potential role for Jak2-autonomous LepRb signals in the regulation of reproductive function, we monitored estrous cycling from 4 to 8 weeks of age in female mice, along with their ability to deliver pups after housing with wild-type males. In addition to examining Δ/Δ, db/db, and wild-type females in these assays, we included mice homozygous for Leprtm1mgmj (a.k.a., Leprs1138 or s/s mice; mutant for Tyr1138→STAT3 signaling) (21) as a positive control for our ability to detect residual reproductive function in obese mice with altered leptin action (Table 2). Whereas essentially all wild-type females and approximately half of the s/s females displayed vaginal estrus when housed in the absence of males and delivered pups after cohabitation with male mice, Δ/Δ females, like db/db animals, failed to undergo estrus or deliver pups. Gross examination also revealed the reproductive organs of Δ/Δ females were atrophic and similar to those of db/db females (data not shown). Thus, Jak2-autonomous LepRb signals are not sufficient to mediate leptin action on the reproductive axis.

TABLE 2.

Fertility data for mice expressing mutant LepRb

| Genotype | Wild type | db/db | Δ/Δ | s/s |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Estrus | 8/9 | 0/9 | 0/8 | 3/8 |

| Litters | 9/9 | 0/7 | 0/8 | 5/8 |

Individually housed females were examined daily from 4 to 8 weeks of age. Cytologic examination of vaginal lavage was used to monitor estrus. Females were paired with one wild-type male and monitored daily for 6 weeks for the production of offspring.

Regulation of the hypothalamic ARC in Δ/Δ animals.

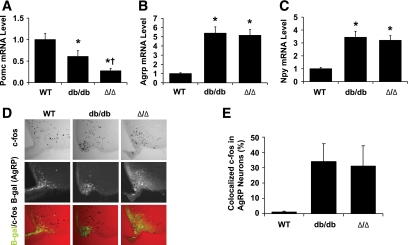

A number of aspects of leptin action in the hypothalamus are beginning to be unraveled, including the role of leptin in regulating arcuate nucleus (ARC) LepRb/proopiomelanocortin (POMC)-expressing neurons and their opposing LepRb/agouti-related protein/neuropeptide Y (AgRP/NPY)-expressing neurons (2,3,31,32). Leptin promotes anorectic POMC expression, while inhibiting the expression of orexigenic AgRP and NPY and attenuating the activity of AgRP/NPY neurons. Although LepRb Tyr1138→STAT3 signaling is required to promote Pomc mRNA expression, signals independent of Tyr985 and Tyr1138 contribute to the suppression of Agrp and Npy mRNA expression, and to the inhibition of AgRP neuron activity (15,21,29). To determine the potential role for Jak2-autonomous LepRb signals in the regulation of these ARC neurons, we examined the mRNA expression of Pomc, Npy, and Agrp in the hypothalamus and examined c-fos immunoreactivity (c-fos-IR) as a surrogate for activity in AgRP neurons (29) of male Δ/Δ, db/db, and wild-type mice (Fig. 3). As expected based on the known role for Tyr1138 in regulating Pomc, Δ/Δ and db/db mice exhibited significantly diminished Pomc mRNA expression compared with wild-type controls (Fig. 3A); Pomc levels in Δ/Δ mice were lower even than those in db/db mice. We found similarly elevated Npy and Agrp mRNA expression in Δ/Δ and db/db mice compared with wild-type mice (Fig. 3B and C).

FIG. 3.

ARC neuropeptide expression and AgRP neuron c-fos-IR in wild-type (WT), db/db, and Δ/Δ mice. A–C: mRNA was prepared from the hypothalami of 10- to 11-week-old male mice. Quantitative PCR was used to determine (A) Pomc, (B) Npy, and (C) Agrp mRNA levels (n = 14–19 per genotype). D: c-fos-IR in AgRP neurons of ad libitum–fed wild-type, db/db, and Δ/Δ animals. All mouse groups were bred onto a background expressing LacZ under the AgRP promoter, enabling the identification of AgRP neurons by staining for β-gal. Representative images showing immunofluorescent detection of c-fos (top), β-gal (middle), and merged c-fos/β-gal (bottom). E: Quantification of double-labeled c-fos/AgRP-IR neurons. Double-labeled AgRP neurons are plotted as percentage of total AgRP neurons ± SEM. A–C and E: *P < 0.05 compared with wild type; †P < 0.05 compared with db/db by one-way ANOVA with Tukey post-test. (A high-quality digital representation of this figure is available in the online issue.)

To analyze c-fos-IR in AgRP neurons, we generated +/+, Δ/Δ, and db/db animals heterozygous for AgrpLacZ, in which β-galactosidase (β-gal) is expressed from the Agrp locus, facilitating the detection of AgRP-expressing neurons by β-gal immunofluorescence (29). Although fed wild-type animals displayed c-fos-IR in few AgRP neurons, a similarly large percentage of AgRP neurons in Δ/Δ and db/db animals contained c-fos-IR, suggesting their activity (Fig. 3D and E). Thus, Jak2-autonomous LepRb signals are not sufficient to mediate either the normal regulation of ARC neuropeptide gene expression or the suppression of c-fos-IR/activity in AgRP neurons.

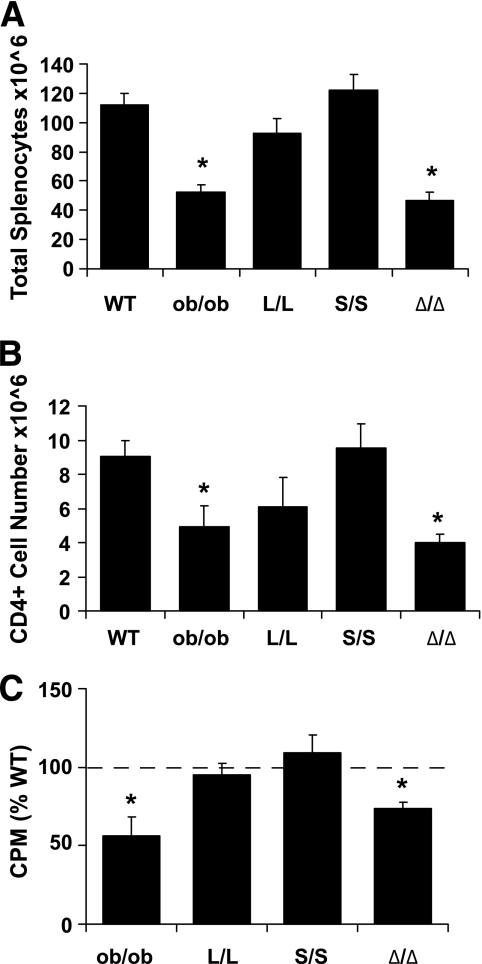

Regulation of T-cell function by LepRb signals.

Leptin signals the status of energy stores to the immune system, as well as to the brain systems that control energy balance and neuroendocrine function. Leptin deficiency results in thymic hypoplasia, reduced T-cell function, and consequent immune suppression (6,33). Although we previously examined thymocyte numbers in young s/s mice deficient for LepRb Tyr1138 signaling, suggesting improved immune function in s/s compared with db/db mice (23), many other parameters of immune function in these and other models of altered LepRb signaling remain poorly understood. To better understand the signaling mechanisms by which LepRb modulates the immune system, we thus determined the numbers of total and CD4+ splenocytes, as well as the ex vivo proliferative capacity of splenic CD4+ cells from a panel of mouse models of altered LepRb signaling. In addition to examining wild-type, ob/ob, Δ/Δ, and s/s animals, we also studied mice homozygous for Leprtm2mgmj (a.k.a., Leprl985 or l/l) mutant for LepRb Tyr985 (15) (Fig. 4). Note that ob/ob animals were used as the control for the absence of leptin action in this study, as sufficient numbers of age-matched db/db animals were not available at the time of assay. In addition to revealing the expected decrease in total and CD4+ splenocytes and their proliferation in ob/ob animals relative to wild-type controls, we found decreases in these parameters in Δ/Δ animals, and normal parameters of immune function in s/s animals. Interestingly, although l/l animals exhibit increased sensitivity to the anorexic action of leptin (15), these parameters of immune function actually trended down (albeit not significantly) compared with wild-type animals. Thus, these data suggest that although Tyr985 and Tyr1138 are not required for the promotion of splenic T-cell function by leptin, Jak2-autonomous LepRb signals are not sufficient to mediate these aspects of leptin action.

FIG. 4.

Reduced numbers and proliferation of splenic T-cells in Δ/Δ and ob/ob but not s/s or l/l mice. Spleens were isolated from the indicated genotypes of male mice, separated using autoMACS, and counted for (A) total splenocytes and (B) CD4+ cells using a flow cytometer (n = 7–22 per genotype). Data are plotted as means ± SEM; *P < 0.05 compared with wild type by one-way ANOVA and Tukey post-test. C: For proliferation assays, CD4+CD25− naive T-cells were isolated by autoMACS (n = 4–7 per genotype), incubated in the presence of bone marrow–derived dendritic cells from C57BL/6J mice and stimulated with anti-CD3e. Incorporation of H3-thymidine (1 mCi/well) by proliferating cells was measured during the last 6 h of culture. Proliferation is expressed as a percentage of a paired wild-type sample analyzed concurrently (dashed line) and is plotted as mean ± SEM; *P < 0.05 by one-way ANOVA and Tukey post-test.

Glucose homeostasis in Δ/Δ mice.

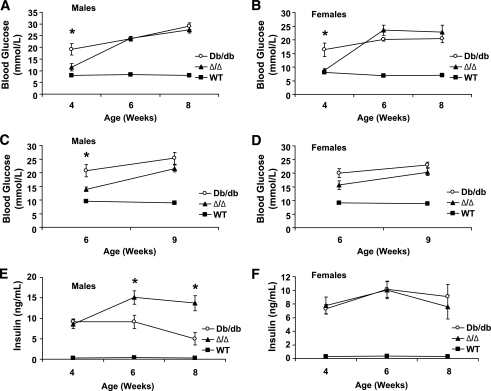

Given the role for leptin in modulating long-term glucose homeostasis (2,20,34), we examined glycemic control in Δ/Δ mice. Interestingly, we found that at 4 weeks of age, the blood glucose levels in male and female Δ/Δ mice were normal, whereas db/db mice were already significantly diabetic (Fig. 5A and B). At later time points, however, Δ/Δ animals exhibited elevated blood glucose levels similar to those of db/db mice. Similarly, male Δ/Δ mice displayed significantly lower fasting glucose levels than db/db mice at 6 weeks of age (Fig. 5C), and fasted females, although not significantly different from db/db animals, also tended to have decreased blood glucose at this early age. Fasted blood glucose in Δ/Δ animals of both sexes was elevated and not significantly different from db/db levels at older ages, however (Fig. 5D). These data suggest that Jak2-autonomous LepRb signals in Δ/Δ mice suffice to delay the onset of diabetes compared with db/db mice, but cannot reverse the later progression to diabetes.

FIG. 5.

Delayed onset of hyperglycemia in Δ/Δ compared with db/db mice. A–D: Blood glucose was determined for ad libitum–fed (A and B) or fasted (5 h) (C and D) animals of the indicated genotype (wild type [WT], ■; db/db, □; and Δ/Δ, ▴) and sex at the indicated ages (n = 8–12 per genotype). E and F: Serum was collected from mice of the indicated genotype and sex at the indicated ages (n = 8–10 per genotype), and insulin content was determined by ELISA. All panels: Data are plotted as means ± SEM; *P < 0.05, db/db compared with Δ/Δ at the indicated time points by one-way ANOVA and Tukey post-test.

For female mice, there was no difference in serum insulin levels between db/db and Δ/Δ mice at any age. In male mice, insulin was also similar between db/db and Δ/Δ mice at 4 weeks of age, but older Δ/Δ males displayed increased circulating insulin levels compared with age-matched db/db males. To discriminate potential alterations in insulin clearance, we also examined serum C-peptide levels, which mirrored insulin concentrations (supplementary Fig. 1, available in an online appendix at http://diabetes.diabetesjournals.org/cgi/content/full/db09-1556/DC1). These data suggest that the relative euglycemia of Δ/Δ compared with db/db animals at 4 weeks of age is not due to differences in insulin secretion (because insulin and C-peptide levels are similar between genotypes, but Δ/Δ animals have decreased blood glucose at this age), but must be secondary to modest improvements in hepatic glucose output and/or insulin sensitivity. This difference is transient, however, as the increased insulin levels in older male Δ/Δ animals fail to decrease blood glucose levels relative to those observed in db/db animals. No difference in β-cell mass was detected between 12-week-old Δ/Δ and db/db mice (supplementary Fig. 2).

In addition, we performed glucose and insulin tolerance tests in the Δ/Δ and db/db animals (supplementary Fig. 3). Although 6-week-old female Δ/Δ animals displayed a diminished hyperglycemic response to the glucose tolerance test relative to db/db controls, no other differences between Δ/Δ and db/db mice were observed. This suggests that the difference in glucose homeostasis between Δ/Δ and db/db animals is small and not sufficient to reveal differences in the face of a substantial glucose load and/or the increased insulin resistance of advancing age.

DISCUSSION

To determine the potential roles for Jak2-autonomous LepRb signals in leptin action in vivo, we generated a mouse model in which LepRb is replaced by a truncation mutant (LepRbΔ65) that contains within its intracellular domain only the sequences required to associate with and activate Jak2. We found that the hyperphagia, obesity, linear growth, ARC physiology, and immune function of these Δ/Δ mice closely resembled that of entirely LepRb-deficient db/db mice. Δ/Δ and db/db animals did demonstrate some modest differences in glucose homeostasis; however, both male and female Δ/Δ mice exhibited a delayed progression to frank hyperglycemia compared with db/db mice. Taken together, these findings demonstrate that Jak2-autonomous LepRb signals may contribute modestly to the modulation of glucose homeostasis by leptin, but emphasize the necessity of signals emanating from the COOH-terminus of LepRb (beyond the Jak2-associating Box1 and Box2 motifs) for most leptin action.

The finding that 4-week-old Δ/Δ mice display similar insulin and C-peptide levels as db/db animals, but exhibit improved blood glucose levels, suggests improved glucose disposal or decreased glucose production in the Δ/Δ mice independent of insulin production. This is consistent with data suggesting that central nervous system leptin action suppresses hepatic glucose production, and with our previous finding that some portion of this is mediated independently of Tyr1138→STAT3 signaling (2,20,34). The Δ/Δ mice progress rapidly (by 6 weeks of age) to dramatic hyperglycemia and parameters of glucose homeostasis indistinguishable from db/db animals, however. Indeed, even at 5 weeks of age, the response to a glucose bolus is comparably poor in male Δ/Δ and db/db animals and barely improved in female Δ/Δ compared with db/db animals. Furthermore, the increased insulin production of Δ/Δ relative to db/db males at 6 weeks of age and beyond fails to ameliorate their hyperglycemia. Thus, the improvement in glucose homeostasis mediated by Jak2-autonomous LepRb signals in Δ/Δ mice compared with db/db animals is very modest, as it is easily overwhelmed by a large glucose load and/or the increasing insulin resistance and diabetes of advancing age. No difference in β-cell mass was detected between Δ/Δ and db/db males. The mechanism(s) mediating the increased insulin production of the Δ/Δ relative to db/db males is unclear, but could represent an improvement in β-cell function due to the later time at which Δ/Δ animals become diabetic or to some residual leptin action in the Δ/Δ β-cell (35).

Although the overall similarity of ARC gene expression and physiology between Δ/Δ and db/db mice indicates little role for Jak2-autonomous LepRb signals in ARC leptin action, the finding of decreased (worsened) Pomc mRNA expression in Δ/Δ compared with db/db mice was surprising. One possible explanation for this observation is that some residual signal mediated by LepRbΔ65 modestly attenuates Pomc expression and that this attenuating signal is overwhelmed under normal circumstances by the LepRb signals that enhance Pomc expression. Unfortunately, the low Pomc content of db/db and Δ/Δ animals and low activity of these neurons at baseline rendered the examination of POMC c-fos uninformative.

Although the molecular mechanisms underlying Jak2-autonomous LepRb action remain unclear, several pathways could contribute. In cultured cells, the activation of Jak2 by LepRbΔ65 and similar receptor mutants mediates some activation of the extracellular signal–related kinase pathway (13,36). Indeed, chemical inhibitor studies have suggested a role for extracellular signal–related kinase signaling in the regulation of autonomic nervous system function by leptin, and the autonomic nervous system underlies a major component of the leptin effect on glucose homeostasis (37). Phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase (PI 3-kinase) also plays a role in the regulation of glucose homeostasis by leptin (38–41). As we have been unable to observe the regulation of PI 3-kinase by leptin in cultured cells and the analysis of this pathway in the hypothalami of obese, hyperleptinemic mice remains problematic, the molecular mechanism by which LepRb engages this pathway remains unclear. Although difficult to test directly, it is thus possible that Jak2-autonomous LepRb signals might modulate this pathway in vivo. We have previously demonstrated that the major regulation of hypothalamic mammalian target of rapamycin (mTOR), including in response to nutritional alteration, occurs indirectly, via neuronal activation (42). We examined this pathway (along with the phosphorylation of STAT3) in the hypothalamus of Δ/Δ animals (supplementary Fig. 4), revealing the expected absence of STAT3 signaling and increased mTOR activity (secondary to the activation of orexigenic neurons) in the mediobasal hypothalamus of db/db and Δ/Δ animals. Thus, the regulation of mTOR is similar in these mouse models.

A potential intermediate linking Jak2 activation to PI 3-kinase activation is SH2B1, a SH2 domain–containing protein that binds phosphorylated Tyr813 on Jak2 (43). Cell culture studies show that SH2B1 binds directly to Jak2, augments its kinase activity, and couples leptin stimulation to insulin receptor substrate activation, a well-known activator of PI 3-kinase (44). Indeed, SH2B1-null mice display hyperphagia, obesity, and diabetes (45). SH2B1 could also mediate other, unknown Jak2-autonomous LepRb signals.

Importantly, the phenotype of mice expressing LepRbΔ65 differs significantly from a mouse model in which LepRbY123F (mutated for the three tyrosine phosphorylation sites, but with an otherwise intact intracellular domain) replaces LepRb (22). Unlike Δ/Δ animals, these LeprY123F mice display improved energy homeostasis and more dramatic improvements in glucose homeostasis (both of which are sustained into adulthood), compared with db/db animals. Unfortunately, the C57 genetic background strain used to study the LeprY123F mice not only differs compared with the C57BL/6J background that we used to study our Δ/Δ and db/db animals, but also diverges from that of the db/db animals used as comparators for the LeprY123F mice (22). Similarly, it is also possible that minor differences between the incipient C57BL/6J backgrounds of db/db and Δ/Δ mice could contribute to the modest distinctions observed between these two models.

Aside from the background strain, the intriguing possibility arises that the intracellular domain of LepRb may mediate heretofore unsuspected signals independently from tyrosine phosphorylation. As it is, future studies will be needed to carefully compare the phenotype of LeprY123F, Δ/Δ, and db/db animals within the same facility and on the same genetic background; should these differences remain, further work will be necessary to confirm the importance and determine the identity of the underlying signaling.

In summary, our findings reveal the insufficiency of Jak2-autonomous LepRb signals for the bulk of leptin action. These finding do not rule out the possibility that Jak2-autonomous signals may be required to support the action of LepRb phosphorylation, however. Indeed, our present findings suggest a modest role for Jak2-autonomous LepRb signals in the regulation of glucose homeostasis by leptin. Understanding collaborative roles for Jak2-autonomous signals in leptin action and deciphering the mechanisms underlying these signals and potential tyrosine phosphorylation–independent signals mediated by the COOH-terminus of LepRb will represent important directions for future research.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This work was supported by National Institutes of Health (NIH) DK-57631 (M.G.M.), NIH DK-67536 (R.N.K.), the American Diabetes Association, and the American Heart Association (M.G.M. and S.R.). Core support was provided by The University of Michigan Cancer and Diabetes Centers: NIH CA-46592 and NIH DK-20572.

No potential conflicts of interest relevant to this article were reported.

We thank Amylin Pharmaceuticals for the generous gift of leptin, Mark Sleeman of Regeneron Pharmaceuticals for AgrpLacZ mice, and Diane Fingar, PhD (University of Michigan) for antibodies.

Footnotes

The costs of publication of this article were defrayed in part by the payment of page charges. This article must therefore be hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 U.S.C. Section 1734 solely to indicate this fact.

REFERENCES

- 1.Friedman JM, Halaas JL: Leptin and the regulation of body weight in mammals. Nature 1998; 395: 763– 770 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Elmquist JK, Coppari R, Balthasar N, Ichinose M, Lowell BB: Identifying hypothalamic pathways controlling food intake, body weight, and glucose homeostasis. J Comp Neurol 2005; 493: 63– 71 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Morton GJ, Cummings DE, Baskin DG, Barsh GS, Schwartz MW: Central nervous system control of food intake and body weight. Nature 2006; 443: 289– 295 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bates SH, Myers MG, Jr: The role of leptin receptor signaling in feeding and neuroendocrine function. Trends Endocrinol Metab 2003; 14: 447– 452 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ahima RS, Prabakaran D, Mantzoros C, Qu D, Lowell B, Maratos-Flier E, Flier JS: Role of leptin in the neuroendocrine response to fasting. Nature 1996; 382: 250– 252 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lord GM, Matarese G, Howard JK, Baker RJ, Bloom SR, Lechler RI: Leptin modulates the T-cell immune response and reverses starvation-induced immunosuppression. Nature 1998; 394: 897– 901 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Elmquist JK, Maratos-Flier E, Saper CB, Flier JS: Unraveling the central nervous system pathways underlying responses to leptin. Nat Neurosci 1998; 1: 445– 450 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Montague CT, Farooqi IS, Whitehead JP, Soos MA, Rau H, Wareham NJ, Sewter CP, Digby JE, Mohammed SN, Hurst JA, Cheetham CH, Earley AR, Barnett AH, Prins JB, O'Rahilly S: Congenital leptin deficiency is associated with severe early-onset obesity in humans. Nature 1997; 387: 903– 908 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Clément K, Vaisse C, Lahlou N, Cabrol S, Pelloux V, Cassuto D, Gourmelen M, Dina C, Chambaz J, Lacorte JM, Basdevant A, Bougnères P, Lebouc Y, Froguel P, Guy-Grand B: A mutation in the human leptin receptor gene causes obesity and pituitary dysfunction. Nature 1998; 392: 398– 401 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lee GH, Proenca R, Montez JM, Carroll KM, Darvishzadeh JG, Lee JI, Friedman JM: Abnormal splicing of the leptin receptor in diabetic mice. Nature 1996; 379: 632– 635 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Huising MO, Kruiswijk CP, Flik G: Phylogeny and evolution of class-I helical cytokines. J Endocrinol 2006; 189: 1– 25 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kloek C, Haq AK, Dunn SL, Lavery HJ, Banks AS, Myers MG, Jr: Regulation of Jak kinases by intracellular leptin receptor sequences. J Biol Chem 2002; 277: 41547– 41555 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Banks AS, Davis SM, Bates SH, Myers MG, Jr: Activation of downstream signals by the long form of the leptin receptor. J Biol Chem 2000; 275: 14563– 14572 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bjorbak C, Lavery HJ, Bates SH, Olson RK, Davis SM, Flier JS, Myers MG, Jr: SOCS3 mediates feedback inhibition of the leptin receptor via Tyr985. J Biol Chem 2000; 275: 40649– 40657 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Björnholm M, Münzberg H, Leshan RL, Villanueva EC, Bates SH, Louis GW, Jones JC, Ishida-Takahashi R, Bjørbaek C, Myers MG, Jr: Mice lacking inhibitory leptin receptor signals are lean with normal endocrine function. J Clin Invest 2007; 117: 1354– 1360 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gong Y, Ishida-Takahashi R, Villanueva EC, Fingar DC, Münzberg H, Myers MG, Jr: The long form of the leptin receptor regulates STAT5 and ribosomal protein S6 via alternate mechanisms. J Biol Chem 2007; 282: 31019– 31027 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Villanueva EC, Myers MG, Jr: Leptin receptor signaling and the regulation of mammalian physiology. Int J Obes (Lond) 2008; 32( Suppl. 7): S8– S12 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Vaisse C, Halaas JL, Horvath CM, Darnell JE, Jr, Stoffel M, Friedman JM: Leptin activation of Stat3 in the hypothalamus of wild-type and ob/ob mice but not db/db mice. Nat Genet 1996; 14: 95– 97 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bates SH, Dundon TA, Seifert M, Carlson M, Maratos-Flier E, Myers MG, Jr: LRb-STAT3 signaling is required for the neuroendocrine regulation of energy expenditure by leptin. Diabetes 2004; 53: 3067– 3073 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bates SH, Kulkarni RN, Seifert M, Myers MG, Jr: Roles for leptin receptor/STAT3-dependent and -independent signals in the regulation of glucose homeostasis. Cell Metabolism 2005; 1: 169– 178 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Bates SH, Stearns WH, Dundon TA, Schubert M, Tso AW, Wang Y, Banks AS, Lavery HJ, Haq AK, Maratos-Flier E, Neel BG, Schwartz MW, Myers MG, Jr: STAT3 signaling is required for leptin regulation of energy balance but not reproduction. Nature 2003; 421: 856– 859 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Jiang L, You J, Yu X, Gonzalez L, Yu Y, Wang Q, Yang G, Li W, Li C, Liu Y: Tyrosine-dependent and -independent actions of leptin receptor in control of energy balance and glucose homeostasis. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2008; 105: 18619– 18624 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Dunn SL, Björnholm M, Bates SH, Chen Z, Seifert M, Myers MG, Jr: Feedback inhibition of leptin receptor/Jak2 signaling via Tyr1138 of the leptin receptor and suppressor of cytokine signaling 3. Mol Endocrinol 2005; 19: 925– 938 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Robertson SA, Koleva RI, Argetsinger LS, Carter-Su C, Marto JA, Feener EP, Myers MG, Jr: Regulation of Jak2 function by phosphorylation of Tyr317 and Tyr637 during cytokine signaling. Mol Cell Biol 2009; 29: 3367– 3378 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Leshan RL, Bjornholm M, Munzberg H, Myers MG, Jr: Leptin receptor signaling and action in the central nervous system. Obesity (Silver Spring) 2006; 14( Suppl. 5): 208S– 212S [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Soliman GA, Ishida-Takahashi R, Gong Y, Jones JC, Leshan RL, Saunders TL, Fingar DC, Myers MG, Jr: A simple qPCR-based method to detect correct insertion of homologous targeting vectors in murine ES cells. Transgenic Res 2007; 16: 665– 670 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Tawara I, Maeda Y, Sun Y, Lowler KP, Liu C, Toubai T, McKenzie AN, Reddy P: Combined Th2 cytokine deficiency in donor T cells aggravates experimental acute graft-vs-host disease. Exp Hematol 2008; 36: 988– 996 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Wortley KE, Anderson KD, Yasenchak J, Murphy A, Valenzuela D, Diano S, Yancopoulos GD, Wiegand SJ, Sleeman MW: Agouti-related protein-deficient mice display an age-related lean phenotype. Cell Metab 2005; 2: 421– 427 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Münzberg H, Jobst EE, Bates SH, Jones J, Villanueva E, Leshan R, Björnholm M, Elmquist J, Sleeman M, Cowley MA, Myers MG, Jr: Appropriate inhibition of orexigenic hypothalamic arcuate nucleus neurons independently of leptin receptor/STAT3 signaling. J Neurosci 2007; 27: 69– 74 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Munzberg H, Flier JS, Bjorbaek C: Region-specific leptin resistance within the hypothalamus of diet-induced-obese mice. Endocrinology 2004; 145: 4880– 4889 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Gao Q, Horvath TL: Neurobiology of feeding and energy expenditure. Annu Rev Neurosci 2007; 30: 367– 398 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Berthoud HR: Interactions between the “cognitive” and “metabolic” brain in the control of food intake. Physiol Behav 2007; 91: 486– 498 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.La Cava A, Matarese G: The weight of leptin in immunity. Nat Rev Immunol 2004; 4: 371– 379 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Barzilai N, Wang J, Massilon D, Vuguin P, Hawkins M, Rossetti L: Leptin selectively decreases visceral adiposity and enhances insulin action. J Clin Invest 1997; 100: 3105– 3110 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Morioka T, Asilmaz E, Hu J, Dishinger JF, Kurpad AJ, Elias CF, Li H, Elmquist JK, Kennedy RT, Kulkarni RN: Disruption of leptin receptor expression in the pancreas directly affects beta cell growth and function in mice. J Clin Invest 2007; 117: 2860– 2868 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Bjørbaek C, Buchholz RM, Davis SM, Bates SH, Pierroz DD, Gu H, Neel BG, Myers MG, Jr, Flier JS: Divergent roles of SHP-2 in ERK activation by leptin receptors. J Biol Chem 2001; 276: 4747– 4755 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Rahmouni K, Sigmund CD, Haynes WG, Mark AL: Hypothalamic ERK mediates the anorectic and thermogenic sympathetic effects of leptin. Diabetes 2009; 58: 536– 542 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Hill JW, Williams KW, Ye C, Luo J, Balthasar N, Coppari R, Cowley MA, Cantley LC, Lowell BB, Elmquist JK: Acute effects of leptin require PI3K signaling in hypothalamic proopiomelanocortin neurons in mice. J Clin Invest 2008; 118: 1796– 1805 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Morton GJ, Gelling RW, Niswender KD, Morrison CD, Rhodes CJ, Schwartz MW: Leptin regulates insulin sensitivity via phosphatidylinositol-3-OH kinase signaling in mediobasal hypothalamic neurons. Cell Metab 2005; 2: 411– 420 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Rother E, Könner AC, Brüning JC: Neurocircuits integrating hormone and nutrient signaling in control of glucose metabolism. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab 2008; 294: E810– E816 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Morrison CD, Morton GJ, Niswender KD, Gelling RW, Schwartz MW: Leptin inhibits hypothalamic Npy and Agrp gene expression via a mechanism that requires phosphatidylinositol 3-OH-kinase signaling. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab 2005; 289: E1051– E1057 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Villanueva EC, Münzberg H, Cota D, Leshan RL, Kopp K, Ishida-Takahashi R, Jones JC, Fingar DC, Seeley RJ, Myers MG, Jr: Complex regulation of mammalian target of rapamycin complex 1 in the basomedial hypothalamus by leptin and nutritional status. Endocrinology 2009; 150: 4541– 4551 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Kurzer JH, Argetsinger LS, Zhou YJ, Kouadio JL, O'Shea JJ, Carter-Su C: Tyrosine 813 is a site of JAK2 autophosphorylation critical for activation of JAK2 by SH2-B beta. Mol Cell Biol 2004; 24: 4557– 4570 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Li Z, Zhou Y, Carter-Su C, Myers MG, Jr, Rui L: SH2B1 enhances leptin signaling by both Janus kinase 2 Tyr813 phosphorylation-dependent and -independent mechanisms. Mol Endocrinol 2007; 21: 2270– 2281 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Ren D, Li M, Duan C, Rui L: Identification of SH2-B as a key regulator of leptin sensitivity, energy balance, and body weight in mice. Cell Metab 2005; 2: 95– 104 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.