Abstract

Nervous tissue engineering in combination with other therapeutic strategies is an emerging trend for the treatment of different CNS disorders and injuries. We propose to use poly (N-isopropylacrylamide)-co-poly (ethylene glycol) (PNIPAAm-PEG) as a minimally invasive, injectable scaffold platform for the repair of spinal cord injury (SCI). The scaffold allows cell attachment, provides mechanical support and a sustained release of neurotrophins. In order to use PNIPAAm-PEG as an injectable scaffold for treatment of SCI it must maintain its mass and volume over time in physiological conditions. To provide mechanical support at the injury site, it is also critical that the engineered scaffold matches the compressive modulus of the native neuronal tissue. This study focused on studying the ability of the scaffold to release bioactive neurotrophins and on matching the material properties to those of the native neuronal tissue. We found that the release of both BDNF and NT-3 was sustained for up to four weeks, with a minimal burst exhibited for both neurotrophins. The bioactivity of the released NT-3 and BDNF was confirmed after four weeks. In addition, our results show that the PNIPAAm-PEG scaffold can be designed to match the desired mechanical properties of the native neuronal tissue, with a compressive modulus in the 3–5kPa range. The scaffold was also compatible with bone marrow stromal cells, allowing their survival and attachment for up to 31 days. These results indicate that PNIPAAm-PEG is a promising multifunctional scaffold for the treatment of SCI.

Keywords: spinal cord injury, hydrogel, injectable, neurotrophins

Introduction

Spinal cord injury (SCI) affects nearly 250,000 Americans with an estimated additional 10,000 cases per year (NIH, 2001). The vast majority of these cases are young adults in their early twenties, who face enormous physical challenges with no treatment currently available. In addition, long-term care of these patients creates an overwhelming financial burden on the healthcare system. In order to successfully repair the lost and damaged tissue following SCI and promote functional recovery, a number of problems need to be solved: (1) Survival of nervous tissue needs to be increased and lost cells need to be replaced; (2) The glial scar which is created after the injury and serves as a barrier to axonal growth must be dissolved; (3) The fluid-filled cyst created at the site of injury must be filled with a matrix that supports axonal growth; (4) The immune reaction that follows the initial injury and leads to inflammation and secondary injury has to be modulated and finally, (5) Regenerating axons must be guided to their target cells to form functional synapses.

For successful recovery of function, a design must address these problems and creating a permissive environment for axonal growth and repair. A variety of strategies have been proposed to create such an environment, including using trophic factors, cellular transplants, polymeric scaffolds, and combinations of these treatments [1–26]. Tissue engineering is an emerging field in biomaterial research with great therapeutic potential but the greatest challenge facing this field is to translate engineering approaches to the clinic. There are large numbers of designs proposed in current literature that focus on microstructure design of porous scaffolds or channels that must be conditioned ex vivo prior to implantation (reviewed in [26]). This approach is not only complicated at the engineering level, but also challenging for surgical implantation. The ideal solution would be to create a scaffold that is designed more simply and robustly, can be easily transplanted and adapt to different injury types.

Common biodegradable materials for scaffold designs are either poly (lactic acid) PLA, PLA-based copolymers, alginate or collagen [17, 25, 27–32]. All these materials degrade over time and degradation rates can be adjusted by copolymerization with different polymer blocks. These designs provide only temporary mechanical support to the injury site and do not guarantee injured axons a stable platform for regeneration. If the degrading scaffold loses its stabilization ability before the axons sufficiently regenerated, the injury site will be subject to compressive stresses leading to more cell death and inflammation [33]. As the scaffold degrades it creates a moving boundary layer between the tissue and biomaterial that can lead to an increased inflammatory response and glial scar formation [34]. Furthermore, if the scaffolds are designed to increase cellular attachment and biocompatibility, then the removal of such a supportive environment for the regenerating tissue could be detrimental.

Some researchers have begun to investigate injectable scaffolds that can fill the site of injury and be delivered in a minimally invasive surgery [2]. These scaffolds also have the desirable property of molding to the irregularly shaped injury site. However, most of these scaffolds require gelation (crosslinking) in vivo which could lead to complications from unreacted monomer or excess reactants [2]. In the past several years, temperature sensitive and in situ-forming hydrogel systems have gained extensive interest for biomedical and pharmaceutical applications. One such polymer is poly (N-isopropyl acrylamide) or PNIPAAm. PNIPAAm-based systems have been one of the most commonly used thermosensitive materials for two major reasons: (1) Its phase transition conveniently occurs between ambient and body temperature and (2) Copolymers of PNIPAAm with different types of monomers can result in materials with a range of different properties [35]. For example, the incorporation of hydrophilic co-monomers tends to increase the swelling capacity of PNIPAAm networks [36]–[37] allowing them to become more macroporous to accommodate cells. Cho et al. encapsulated human mesenchymal stem cells in a matrix made from PNIPAAm grafted with chitosan [10]. The cell-thermosensitive gel complex was injected into the submucosal layer of the bladder of a rabbit, resulting in cartilage growth [38]. This study shows that PNIPAAm gels are not only biocompatible, but also good substrates for cell attachment and growth. PNIPAAm-based hydrogels can also be used to immobilize drugs, enzymes, antibodies, and other biomolecules, which can then be released in an initial burst followed by drug release from within the matrix via diffusion [39]. The most desirable property of PNIPAAm-based hydrogels is, however, that these gels form in situ and do not require cross-linking in vivo. This eliminates the risk of excess reactants and allows the gels to mold to the irregularly shaped injury site.

Many polymeric scaffolds do not address another key design obstacle –mechanical mismatch. If matrices are not correctly engineered, their use can lead to implant failure [40]. Ozawa et al, have performed extensive mechanical analysis of the white and gray matter of spinal cord tissue. They have found that the compressive modulus of the spinal cord white matter is on the order of 3–5kPa [41, 42] providing a baseline magnitude that could be used in mechanical analyses of neural tissue engineered constructs.

Although many different hydrogel-based scaffolds have been evaluated for spinal cord repair this study is testing a novel injectable polymeric design. We propose that the thermally responsive poly (N-isopropyl)-graft-poly (ethylene glycol) (PNIPAAm-PEG) can function as an injectable multifunctional scaffold for tissue engineering applications. Below its lower critical solution temperature (LCST), typically around 29–32°C, the polymer forms a miscible solution with water, but above its LCST, it becomes hydrophobic, separating from water and forming a semi-porous gel. Since the polymeric scaffold is semi-porous, cell can be easily incorporated. Cells and therapeutic factors such as neurotrophins can be mixed with the polymer at room temperature or below and then delivered in a minimally invasive fashion to provide a space-filling multifunctional scaffold that molds itself to the site of injury.

Previously attempted cellular scaffolds have included Schwann cells, olfactory ensheathing cells, fibroblasts, marrow stromal cells, and neural precursor cells[13, 30, 43–47]. Using cellular scaffolds is of great interest because a small number of cells could potentially fill a large “gap”. Transplanted cells provide not only matrices for growing axons, but they may also provide the necessary trophic factors and extracellular cues necessary for axonal regeneration. Cellular scaffolds, although biologically advantageous, do not meet a lot of the biomechanical requirements. Since cellular bridges lack the full design requirements, the combination of a polymeric- cellular could be advantages.

Marrow stromal cells (MSCs, also known as mesenchymal stem cells) are easily accessible compared to most other proposed transplanted cell lines, and are found largely in the bone marrow. Transplanted MSC in injured mice models show they are capable of migrating to the injured tissue[48]. Transplanted MSCs have also shown the ability to attract host cells to the transplantation site[49]. It is believed that greatest benefit of using these transplanted cells is the ability to express and secret different cytokines and growth factors[50]. The transplantation of these cells into injured rat spinal cords yielded locomotor improvements as measured on the BBB scale, and can be attributed to the release of growth promoting factors from the MSCs [50].

Since the goal of these studies was to find a scaffold that was best suited for moving forward to testing in animal models, it was critical to evaluate the effect of physiological salts and serum proteins on scaffold properties. Consequently the PNIPAAm-PEG scaffold was created using three different aqueous solutions. The ability of the scaffold to release bioactive trophic factors was also evaluated in order to determine its ability to function as a scaffold for spinal cord repair. To our knowledge, this is the first proposed use of a PNIPAAm-based polymeric hydrogel for neural tissue engineering, and one of a limited number of injectable designs proposed [2].

Methods

Polymer synthesis

Poly ethylene glycol dimethacrylate (PEGDM, Mw=8000) was synthesized by reacting poly ethylene glycol (PEG Mw=8000) diol with an excess of methacylrylol chloride under anhydrous conditions as described by Bryant et al [51]. The efficiency of this reaction was assessed using 1H NMR (Varian 300, Palo Alto, CA) by comparing the integral area under the peak for the vinyl protons to area of the PEG protons [52]. The PNIPAAm-PEG copolymer was polymerized as previously described by Vernengo, et al [52]. Briefly, the NIPAAm monomer was mixed with PEGDM (8000) at a 700:1 monomer ratio in methanol and the free radical polymerization was thermally initiated by azobisisobutylnitrile (AIBN) at 65°C. The reaction was allowed to go until completion (48hrs) prior to removal of excess methanol through evaporation. The copolymer was ground and purified by washing with hexane and then dried. The molar ratio of PNIPAAm:PEG was assessed using proton NMR.

Lower critical solution temperature determination

The lower critical solution temperature (LCST) of the PNIPAAm-PEG solutions was found using a Differential Scanning Calorimeter (DSC) from TA Instruments (Model # 2010, Wilmington, DE). A 10mg sample was placed in an allodized aluminum pan that was hermetically sealed then heated from 10 to 60°C at 10°C per minute. The onset temperature for the endothermic phase transition on the DSC thermograph was taken to be the LCST.

Swelling properties of PNIPAAm-PEG in different immersion media

PNIPAAM-PEG aqueous solutions were made at 10-wt% using either Dulbecco’s phosphate buffered saline (PBS), DMEM/F12 (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA, “media”), or DMEM/F12 with 20% fetal bovine serum (FBS; Hyclone, Logan, UT, “media with serum”). Hydrogel samples were made by adding 2mL of 10-wt% aqueous copolymer solution to a 24 well tissue culture dish and heating to 37°C for 1 hour. Samples were then removed and an initial wet mass in air and heptane prior to immersion was taken for each sample as the initial value (t=0). Samples were then immersed in 15mL of PBS, media or media with serum at 37°C. At desired time points, samples were removed and massed in air (Mair) and in n-heptane (Mheptane) in order to determine the density (°) and volume (V) over time. The mass and volume retention were taken to be the ratio of mass (or volume) at time t to mass (or volume) at time zero.

The resulting polymeric hydrogel morphology was evaluated using scanning electron microscopy (SEM). SEM samples were lyophilized and coated with platinum using a SCS G3P-8 spin coater (SCS Inc, Indianapolis, IN) prior to viewing on a FEI XL30 Environmental SEM (FEI Company, Hillsboro, OR), at 10 kV, spot size 3, and 1.4×10−4kPa.

Mechanical testing

The compressive modulus of all samples was evaluated using an Instron mechanical testing system (Model 4100, Series IX software, Park Ridge, IL). Cylindrical scaffold samples were tested in a custom made immersion bath that allowed for samples to remain immersed in aqueous media at 37°C during testing. Samples were compressed at a strain rate of 100% per minute and load versus displacement data were collected. The load and displacement could be converted to stress versus strain by using the pre-measured dimensions of each sample. The compressive modulus was taken as the slope of the linear region of the stress-strain curve (from 0–15% strain).

Release and Bioactivity of trophic factors from the scaffold

Polymer scaffolds made from 10-wt% aqueous PNIPAAm-PEG (8000 Mw, 700:1) in DMEM/F12 media were molded in 12-well dishes and maintained at 37°C and 5% CO2 with DMEM/F12. Neurotrophic factors were added to the aqueous polymer solution prior to molding. Medium was conditioned for 3 days prior to analysis for neurotrophin bioactivity. The samples tested were control (0.5mL of copolymer only), brain derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF, 25 μg in 0.5mL copolymer solution) and neurotrophin-3 (NT-3, 25μg in 0.5mL copolymer solution). DMEM/F12 media with 100ng/mL of both BDNF and NT-3 was used as positive control, DMEM/F12 media alone served as negative control.

To assess if neurotrophins released from the scaffold were biologically active, a chick dorsal root ganglion (DRG) explant bioassay was used to evaluate neurite outgrowth. Fertilized eggs obtained from SPAFAS (Preston, CT) were incubated in a humidified incubator at 37°C for 8 days. Eggs containing E10 embryos were opened, and the embryo removed to a sterile Petri dish containing pre-warmed DMEM with 0.1% heat-inactivated goat serum. Meninges and connective tissue were removed and lumbar DRG dissected out. DRG explants were cultured in poly-L-lysine-coated 24-well dishes for bioactivity assays. BDNF- and NT-3-induced neurite extension were tested as described previously [23]. The assay was done 3 days and 4 weeks after loading the scaffold. DRG explants were exposed to 500 μl of each sample media (n=6 DRG for each condition); After 48 hours of incubation in 37°C at 5% CO2 DRGs were fixed in 0.25% glutaraldehyde and neurite outgrowth was examined. Images were obtained using an Olympus CK40 microscope (Hitech Instruments, Edgemont, PA) with a 10x phase objective connected to a Nikon Coolpix 990 digital camera (Nikon Instruments, Melville, NY). To determine the average length of axons extended from each DRG, the distance from the edge of the explant to the main field of growth cones was measured in four places around the perimeter using a micrometer slide. The average of four measurements and the standard error were calculated for each experiment [57].

Samples of conditioned media were taken each time fresh media was added to the hydrogel samples and quick frozen for storage. After collection, samples were thawed and run on a sandwich enzyme linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) for BDNF and NT-3 concentrations (R&D Systems, Minneapolis, MN). Kits were used per manufacturer’s instructions.

Marrow Stromal Cell Culture

Human bone marrow stromal cells were obtained from the Tulane Center for Gene Therapy (New Orleans, LA). The donor of these cells was a female, age 20, and all cells were either passage 2 or 3. Cryopreserved MSC were thawed quickly at 37°C and plated in α-MEM (Invitrogen) supplemented with 20% FBS and 4 mM l-glutamine (Invitrogen) on 100-mm plastic dishes. The following day, cells were washed two times with HBSS and then removed from the culture plates using 0.1% trypsin/EDTA (Cellgro, Herndon, VA). Cells were then re-suspended in the PNIPAAm-PEG copolymer solution.

Polymer-Cell viability assay

Cells were added at 1 million cells per 1 mL sample. The cell count of viable cells was found using trypan blue (Invitrogen) and a hemocytometer. Cells were washed in PBS and pelleted prior to resuspending in the 10 wt% aqueous polymer solution, made from DMEM-F12 cell culture media with 20% FBS. The scaffolds were molded in 12 well culture dishes at 37°C and then transferred to a larger culture dish with excess culture media in order to support the cell growth. The media added to scaffold systems also included penicillin-streptomycin as used routinely in cell culture. The viability of the cells within the scaffold was assessed over time with a dual fluorescent stain (LIVE- DEAD assay) for both live and dead cells. This allowed the cells to be viewed while in the opaque solid hydrogel. Briefly, the media was removed from the desired sample, and it was washed once with warm cell culture grade phosphate buffer. The staining solution was mixed per the manufacturers (Invitrogen) directions and the sample was incubated in the stain for 2 hours at 37°C and 5% CO2 prior to imaging on an inverted fluorescent microscope.

Results

Polymer synthesis and characterization

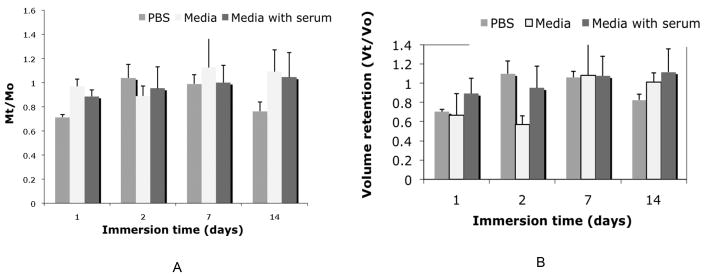

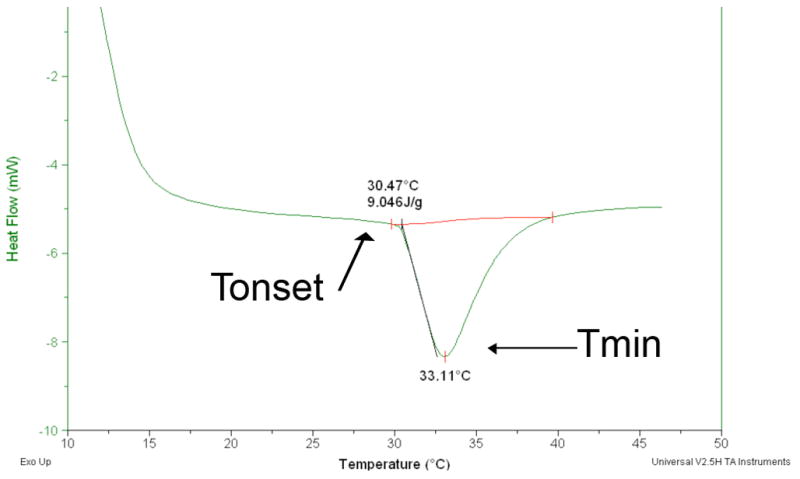

PEGDM was successfully synthesized, as verified by proton NMR shown in Figure 1A, and polymerized with NIPAAm monomer to make PNIPAAm-PEG with a monomer ratio of 700:1 (as verified by NMR, Figure 1B). The resulting polymer was made into aqueous solutions using a 10-wt% aqueous solution in one of the following solvents: PBS, DMEM/F12 media or DMEM/F12 media with 20% FBS. The lower critical solution temperature (LCST) of these solutions was determined by taking the onset temperature for the endothermic phase change from an aqueous solution to a phase separated polymeric hydrogel. The typical DSC thermogram for this phase transition is shown in Figure 2. We found that changing the immersion media for the aqueous solution had no effect of the LCST of the PNIPAAm-PEG copolymer.

Figure 1. Conformation of polymer synthesis.

The PEGDM synthesis as well as the PNIPAAm-PEG synthesis was confirmed using 1H NMR. (A) PEGDM methyacrylation efficiency was evaluated by comparing the ratio of the peaks for protons at A and protons a B. (B) The ratio of the NIPAAm:EG was calculated by comparing the areas of the peaks at marked A and B.

Figure 2. Typical DSC thermogram.

The DSC thermogram above indicates the heat flow over temperature for PNIPAAm_PEG in PBS, where the phase transition shown is the liquid to solid transition. The two temperatures marked are the onset temperature (Tonset) of the transition and the minimum transition temperature (Tmin). The onset temperature is taken to be the lower critical solution temperature (LCST) since it is the temperature at which the solid gel begins to form.

Swelling and mechanical properties of the PNIPAAm-PEG scaffold

PNIPAAm-PEG scaffolds were made in 3 different solvents as described above. The scaffolds were molded by adding 2mL of aqueous polymer solution to a 24-well tissue culture plate and incubating the solutions for 1 hr at 37°C. Scaffolds were then immersed in the same aqueous media they were prepared in to determine their swelling and mechanical properties. All samples were tested at n=6 with the average reported plus the standard deviation.

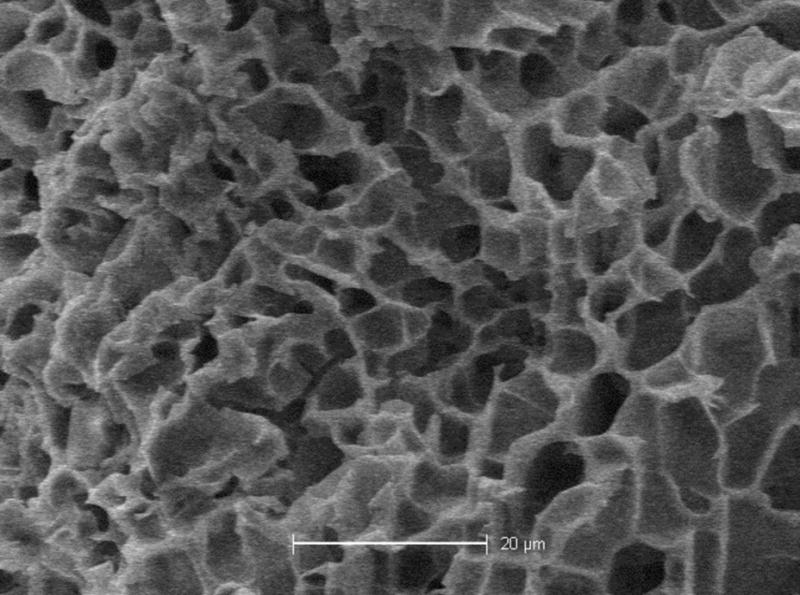

In order to assess the pore morphology, scaffolds were removed after seven days of immersion, flash frozen in liquid nitrogen and then lyophilized. The scaffolds were viewed using a scanning electron microscope and a representative image of a PNIPAAm-PEG scaffold immersed in PBS is shown in Figure 3. The scaffold shows a macroporous structure; however, these pores do not appear to be interconnected as commonly seen in polymeric hydrogels. A similar morphology was seen in scaffolds made from DMEM/F12 media and DMEM/F12 media plus 20% FBS aqueous solutions. Pore diameters ranged around 10 microns in all scaffolds.

Figure 3. The morphology of a PNIPAAm-PEG scaffold.

The scanning electron microscope image shows a PNIPAAm-PEG scaffold made using PBS after 14 days immersion at 37°C. The scaffold exhibits a macroporous structure, but no evidence of interconnectivity. The scale bar equal 20 microns.

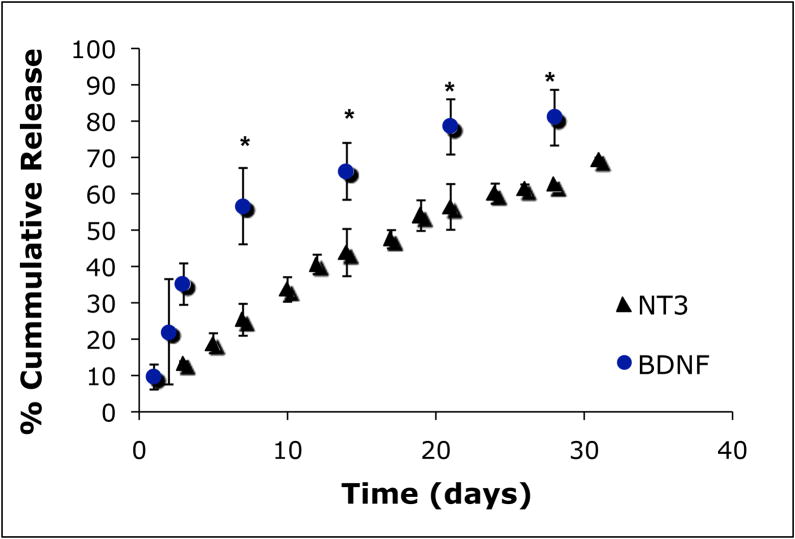

In order to determine the mass retention for the PNIPAAm-PEG scaffold immersed in different media, the initial wet mass was taken immediately after molding and prior to immersion, and then compared to the final wet mass at desired time points. The ratio of the final to initial wet mass indicates mass retention with a value of one signifying no change in mass, and values below one indicating a loss in mass. The results for the PNIPAAm-PEG scaffold mass retention over time in the three different immersion media can be seen in Figure 4A. Perfect retention of mass is presented as one. It is obvious that in all three immersion media, the sample mass is retained over time. Similarly, the volume retention over time was found by comparing the final volume of the scaffold to the initial volume. The volume was found using equation 1, where Mair is the wet mass found in air, while Mheptane is the mass found while immersed in n-heptane. The density of heptane was taken to be 0.684.

Figure 4. PNIPAAm-PEG scaffolds swelling properties in different immersion media.

Mass (A) and volume (B) retention over immersion time are show in part (A) and (B) respectively for scaffolds immersed in DMEM/F12 media (media) with and without 20% fetal bovine serum (serum) as compared to PBS. Data is presented as the average of n=6 + STDEV. In the presence of media with serum as well as PBS the mass and volume retention over time is close to 100% making these scaffolds acceptable for tissue engineering implants.

| (1) |

The volume retention of the PNIPAAm-PEG scaffold in different immersion media (Figure 4B) decreases immediately after injection, but remains at this level for the remainder of 14 days in all cases.

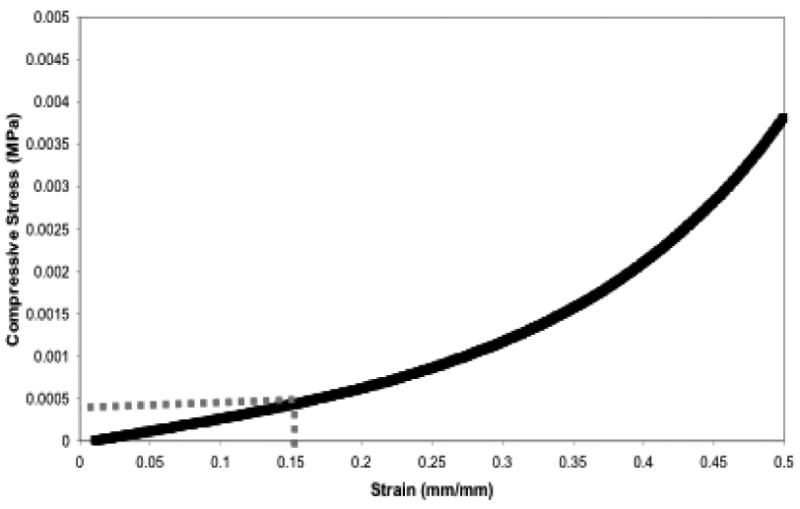

Another set of scaffolds was similarly prepared and immersed in the three different immersion media for seven days prior to mechanical testing. The scaffolds were compressed at a constant strain rate to determine the compressive modulus while immersed in aqueous media at 37°C (physiological conditions). A representative stress-strain curve generated from these scaffolds is seen in Figure 5. The compressive modulus was determined as the slope of the linear region of the generated stress-strain curve, which for these scaffolds was taken to be 0–15% strain. The resulting modulus, shown in Table 1, reached equilibrium within fourteen days, and was found to be similar for both PBS and DMEM/F12 media; however, the addition of 20% serum to the media increased the scaffold modulus.

Figure 5. Stress-stain curve for PNIPAAM-PEG scaffolds post swelling.

Shown is a typical stress-strain curve for PNIPAAm-PEG scaffolds while immersed at physiological conditions. Samples were uni-axially compressed at 100% strain per minute while measuring compressive force and displacement that was converted to stress versus strain.

Table 1. The material properties of PNIPAAm-PEG(8000) in different immersion media.

Scaffolds were prepared by injecting a known mass of 10wt% polymer solution (made from one of the three immersion media) then immersed in the same media for seven days prior to uniaxially compressing to find the compressive moduli. The moduli were taken as the slope from 0–15% strain. The LCST was found from the onset temperature of the phase transition in the DSC thermogram.

| Immersion media | Compressive modulus (kPa) | LCST(°C) |

|---|---|---|

| PBS | 2.2 +/− 0.6 | 31 +/− 0.5 |

| Media | 3.8 +/− 0.7 | 31 +/− 1.3 |

| Media with serum | 1.4 +/− 0.7 | 30 +/− 1.8 |

Trophic factor release from the PNIPAAm-PEG scaffold

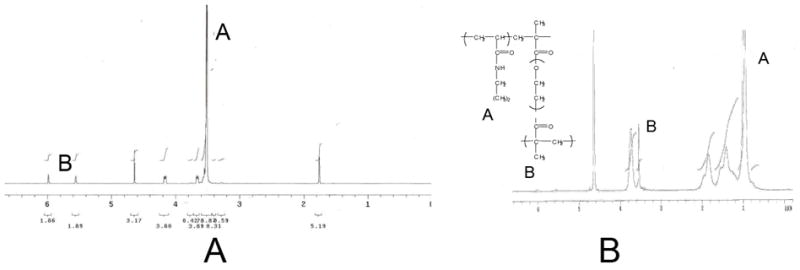

In order to determine the release profile from the in vitro scaffold system, scaffolds were loaded with NT-3 (25μg) or BDNF (25 μg). Scaffolds were immersed in 2mL of the appropriate media and fresh media was added every 2–3 days, while removed media samples were collected and analyzed using NT-3 or BDNF specific enzyme linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA). ELISA results showed that the scaffold provides a minimal burst of 17% in the first 24 hours followed by a controlled, almost linear release of the trophic factor for up to four weeks (Figure 6). If the release is modeled as linear, then 100% release is predicted to be completed at 6 weeks.

Figure 6. Trophic factor release from scaffold.

The cumulative release of neurotrophins (NT-3 (triangles), BDNF (circles)) over time was found using ELISA. Both neurotrophins exhibit a minimal burst (~17%) followed by a slow linear release of approximately 80% of the total neurotrophin at four weeks (n=5). Release samples at the same time point that were statistically significant (p<0.05) are indicated with *.

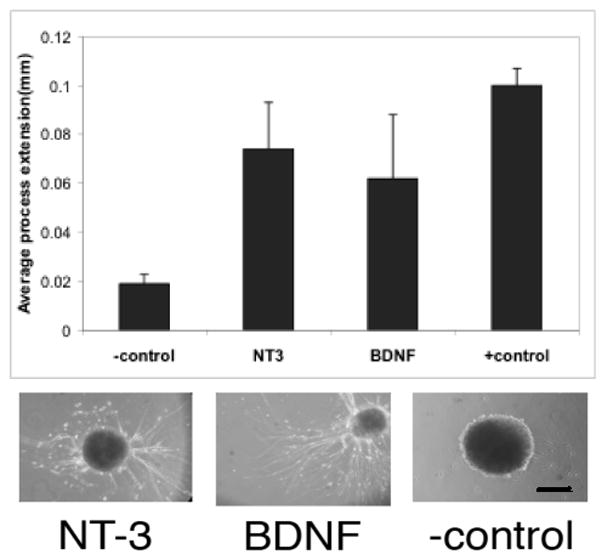

In order to determine if the released trophic factors were biologically active, media samples from the previous release study were taken and immediately applied to cultured DRG explants for two days. Two days is sufficient time for the cultured DRG to extend processes if there is enough active trophic factor present (at least 1–10ng/mL). Representative DRG cultures from the NT-3 group, BDNF group and negative control can be seen in Figure 7A, while the process growth averaged for the different samples is shown in Figure 7B. The DRG exposed to supernatant from NT-3-scaffolds and BDNF-scaffolds both showed significant growth compared to the media alone, suggesting that the trophic factors released were still biologically active after 31 days in the PNIPAAm-PEG scaffolds kept at physiological conditions.

Figure 7. Bioactivity of the released trophic factors.

The bioactivity of the released neurotrophic factors was evaluated using DRG explants. When explants extended processes in the presence of the 4 week release media, the trophic factor was considered to be bioactive. Scale bar in image is 200μm. Media alone was used as negative control; 100ng/ml of nerve growth factor in the media was used as positive control. Data is presented as average process extension + SDEV (n=6 for each condition). NT-3 and BDNF both remained bioactive after 4 weeks.

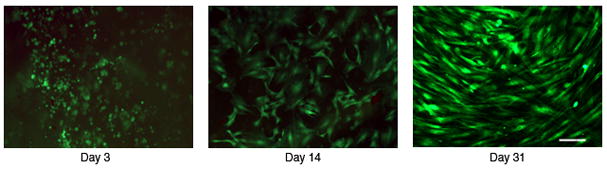

Polymer-Cell Viability

MSCs were loaded into the scaffold and cell survival evaluated at day 2, 14 and 31 (Figure 3). On day 3, a large number of live cells (green) and a limited number of dead cells (red) were observed. At this time point, the surviving cells had not yet attached to the scaffold and displayed a rounded morphology. By day 14, cells had attached and displayed their normal morphology. After 31 days in culture, the incorporated cells were alive, attached and appeared to have proliferated within the scaffold.

Discussion

Injectable scaffolds for neural tissue engineering are of great interest since they provide a minimally invasive way to deliver cells and trophic factors to the tissue. Use of such a scaffold could easily be translated to the clinic for treatment of SCI and other CNS disorders. The first step in evaluating PNIPAAm-PEG as an injectable polymeric scaffold for neural tissue engineering was to verify the copolymer synthesis. The 1H NMR results show that not only was the PEG successfully di-methacrylated, but also that the PNIPAAm-PEG copolymer was within reasonable error of the estimated 700:1 monomer ratio (NIPAAm:EG).

Since the copolymer scaffold was designed to incorporate cells, the effect on material properties of physiological media salts, peptides and serum proteins necessary for cell growth were evaluated. In vitro testing was modified by using DMEM/F12 cell culture media with 20% FBS instead of simply using phosphate buffer. This allowed characterization of the scaffold in the presence of media components and also served as a better model for the osmotic conditions of the native neural tissue post SCI where different cell types, proteins, and cell debris are present in the local tissue.

Since the proposed scaffold allows for minimally invasive surgical delivery, the effects of modeled in vivo conditions on the lower critical solution temperature (LCST) were critical to determine. The LCST of PNIPAAm-PEG made at 10 wt% aqueous solution with PBS was found to be 30.74°C +/− 0.45, which corresponds to the value previously reported by our laboratory using 15 wt% aqueous solutions in PBS [52]. The presence of salts, peptides and serum proteins found in DMEM/F12 media and DMEM/F12 media with 20% serum did not have any effect on the LCST exhibited by the PNIPAAm-PEG copolymer. This is a positive result suggesting that the in vivo conditions will also not affect the LCST exhibited by this copolymer. This should allow successful injection into spinal cord tissue where it will form a stable hydrogel.

Since stable hydrogels could be formed in all three immersion media, the morphology of these scaffolds was examined using scanning electron microscopy. The results indicated that in all cases, the hydrogel exhibited a porous structure; however, the pores did not appear to create the large interconnected macroporous structure typically exhibited by swollen hydrogels. It has been shown by our laboratory that viewing under SEM post lyophilization distorts the pore structure of the scaffold, especially when compared to environmental SEM, where scaffolds can be viewed in their natural hydrated state [53]. However, since the temperature control of this system does not allow the thermoreversible PNIPAAm-PEG scaffold to be viewed above its LCST, we were unable to determine the hydrated scaffold morphology of PNIPAAm-PEG. The traditional SEM images indicated the presence of a pore structure, the inability to view them at a hydrated state, however, does not allow us to infer if these pores are interconnected in a hydrated state. The size of the pores seen in the SEM images suggests that inclusion of cells will be possible and it is unlikely that cell inclusion will interfere with the pore structure.

Once the morphology of the scaffold was established the swelling and mechanical properties were evaluated. The PNIPAAm-PEG scaffold is a nonbiodegradable design and therefore should not exhibit a loss in mass overtime. It is critical in this design that the scaffold remains intact since it serves not only as a mechanical stabilizer, but also as a substrate for the regenerating axons. In order to test the scaffold’s ability to retain its mass over time it was immersed in solution (PBS, DMEM/F12 or DMEM/F12 + 20% FBS) at physiological conditions and the samples mass was recorded over time. The scaffolds were able to maintain mass (Mt/Mo equal to 1 would be perfect mass retention), as seen in Figure 4A post injection. This result was expected, since none of the bonds in the PNIPAAm-PEG backbone are highly susceptible to hydrolytic cleavage.

Since the PNIPAAm-PEG will be injected into a fluid-filled cyst created post SCI, it is critical for the stabilization of the injury site that the scaffold will be space-filling. Swelling of the scaffold (increase in volume) could lead to detrimental effects as a result of increased pressure on the local tissue, while shrinkage of the gel over time would limit the scaffolds ability to provide mechanical stabilization and create a permissive environment for regeneration. In order to assess the scaffolds ability to maintain volume post injection, scaffold volumes were calculated by determining the density of the scaffold over immersion time at physiological conditions. An initial loss in volume immediately upon injection of the scaffold is exhibited in all cases due to the expulsion of water during the hydrophilic collapse of the polymer chains. However, once the scaffold is molded (Vo), it is capable of retaining the water content over time. The ability of the scaffold to maintain its volume within 90% of its original volume (Vt/V equal to 1 would be perfect retention of volume) was seen in all three cases. This result is critical in both the ability of the scaffold to function as a biomechanical device, but also for future use as scaffold for cell transplants.

A critical material design element, often overlooked in tissue engineering applications, is the mechanical match of the implant material with the native tissue. In the case of the spinal cord white matter, it is critical that the implanted material be appropriately soft in order to prevent mechanical mismatch. Adult rat spinal cord white matter has been shown to have a compressive modulus in the range of 3–5kPa [41, 42], which is considered to be the target range of these designs. The compressive modulus was evaluated for PNIPAAm-PEG scaffolds after seven days immersion at physiological conditions because previous studies by our laboratory have shown that the PNIPAAm-PEG scaffold reaches equilibrium within this time frame [52]. Results for the modulus testing in the different immersion media show that the scaffold’s modulus, in all cases, is in the correct order of magnitude; however, the inclusion of serum proteins results in a decrease of the scaffolds compressive modulus. The compressive strength of hydrogels is controlled largely by their cross-linking and water content. In the case of PNIPAAm-PEG hydrogels in different solvents like PBS and DMEM/F12 +20% FBS, there is no significant difference in their water content as determined in swelling studies. This suggests that the difference exhibited in their compression moduli is a result of decreased cross-linking in the presence of serum proteins (20% FBS). The serum proteins act as a plasticizer in the solution, impeding the polymer chains from physically entangling during their phase transition to form the solid hydrogel. The effect of excess serum proteins from cell incorporation and cell debris post injury in the spinal cord tissue has to be taken into consideration because of its potential to decrease the cross-linking ability of the polymer upon injection.

Finally, we evaluated the release kinetics of neurotrophic factors (NTFs) from the PNIPAAm-PEG scaffold in vitro. The release profile of NT-3 and BDNF from the PNIPAAm-PEG scaffold exhibited a minimal burst (~17%) followed by a linear release for four weeks to ~80% of total cumulative release. If the curve is modeled as a linear controlled release, total release is projected to take six weeks. This result was somewhat unexpected from a hydrogel scaffold. Since most hydrogels have such large water contents and large macropores, release is most often diffusion through the aqueous solution leading to a large burst release with a total release time on the order of hours to days. In the case of the PNIPAAm-PEG scaffold, the immediate burst release is a result of the expulsion of some of the water (and therefore neurotrophic factors) during the polymeric chain collapse to a solid hydrogel. However, the neurotrophic factors that become entrapped within the hydrogel are released slowly over a prolonged time because the scaffold itself appears to provide a barrier to the release. As confirmed by previous SEM images, the PNIPAAm-PEG scaffold does not have a large interconnected porous structure. The lack of interconnected pores along with the hydrophobic nature of the polymer chains may prevent the water from rapidly diffusing through the scaffold and taking the neurotrophic factors along with it. This delayed water transport also delays the transport of hydrophilic drugs from the scaffold, creating an ideal scaffold for drug delivery of therapeutic proteins.

The controlled release from the PNIPAAm-PEG scaffold is therapeutically promising; however, the most exciting result is the confirmed bioactivity of released trophic factors. Neurite outgrowth assays using chick embryo DRG show that released NT-3 and BDNF are still biologically active since they promote process extension after 31 days incubation in the PNIPAAm-PEG scaffold. Since entrapment of neurotrophic factors into the scaffold does not require the use of extreme temperatures or solvents, it is not surprising that these proteins remain intact; however, incubation at 37°C for 31 days could have resulted in inactivation of these neurotrophic factors [54]. Previous studies have reported that neurotrophic factors can lose their bioactivity after 5+ days at physiological conditions [54], therefore the ability of the PNIPAAm-PEG scaffold to protect the bioactivity of neurotrophic factors prior to their release is of great therapeutic potential. We propose that the PNIPAAm-PEG scaffold can be used as a controlled delivery device for different therapeutic proteins. This strategy is highly advantageous because of its ability to control the release profile, and because it can protect the proteins biological activity at physiological conditions.

Since the PNIPAAm-PEG scaffold can be designed to match the material properties of the neural tissue, and provided a sustained release of biological active trophic factors, the next question is whether the scaffold can support cells for possible transplantation therapies. The addition of MSCs to the scaffold prior to molding allowed for a disperse incorporation throughout the entire polymeric matrix. The MSCs survived for 31 days within the scaffold in vitro and were able to attach to the scaffold at 14 days. The delayed attachment compared to plastic cell culture dishes is a result of the three dimensional structure of the hydrogel making it more difficult for the cells to attach. Survival and attachment of the MSC cells within the scaffold is a promising result for in vivo cell transplantation using the PNIPAAm-PEG scaffold.

Conclusions

These studies have shown that a PNIPAAm-PEG copolymer can be successfully synthesized, and made into a stable hydrogel exhibiting unique pore morphology. This hydrogel scaffold can be made and immersed in aqueous media containing salts, peptides and serum proteins. The PNIPAAm-PEG scaffold can retain its mass and volume over time, and can be designed to match the mechanical stiffness of the native neural tissue. Release of neurotrophic factors from the PNIPAAm-PEG scaffold is possible for up to six weeks and the biological activity of the released neurotrophic factors was confirmed after 4 weeks incubation. The PNIPAAm_PEG scaffold is able to support the survival and attachment of MSCs that resemble their normal morphology after 7 days incubation within the polymer matrix. The PNIPAAm-PEG therefore is a novel multifunctional scaffold for minimally invasive surgical delivery of therapeutic proteins and cells for neural tissue engineering applications.

Figure 8. Polymer-cell viability with MSCs.

Human bone marrow stromal cells (MSCs) were mixed with the scaffold prior to molding and stained for viability at varying timepoints. Images were all taken at 20x phase objective, scale bar shown is 100μm. The images show the cell viability (live cells (green), dead cells (red)) at 3, 14 and 31 days of incubation in the polymer scaffold in vitro. After 14 days it is clear that the cells not only survive but resemble their normal morphology.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Lee Silver, and Dr. Gianluca Gallo for their assistance in the DRG cultures, and Maryla Obracka for assistance with the bone marrow stromal cell cultures as well as technical assistance with ELISA. The authors would also like to thank Layla Houshmand, Dexter Jacobs and Lawrence Matthews for their assistance with material testing.

References

- 1.Taylor L, Jones L, Tuszynski M, Blesch A. Neurotrophin-3 Gradients Established by Lentiviral Gene Delivery Promote Short-Distance Axonal Bridging beyond Cellular Grafts in the Injured Spinal Cord. J Neurosci. 2006;26(38):9713–9721. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0734-06.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Piantino J, Burdick JA, Goldberg D, Langer R, Benowitz LI. An injectable, biodegradable hydrogel for trophic factor delivery enhances axonal rewiring and improves performance after spinal cord injury. Exp Neurol. 2006 Oct;201(2):359–367. doi: 10.1016/j.expneurol.2006.04.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Dhar SD, Radulescu N, Gharibjan DJ, Hayes GRD. Evans. Regulated Nerve Growth Factor Delivery on Novel Polymers by hNGF-EcR-293-TK Cells. Journal of reconstructive microsurgery. 2006:22. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chen Q, Zhou L, Shine HD. Expression of Neurotrophin-3 Promotes Axonal Plasticity in the Acute but Not Chronic Injured Spinal Cord. Journal of neurotrauma. 2006;23(8):1254–1260. doi: 10.1089/neu.2006.23.1254. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Burdick JA, Ward M, Liang E, Young MJ, Langer R. Stimulation of neurite outgrowth by neurotrophins delivered from degradable hydrogels. Biomaterials. 2006 Jan;27(3):452–459. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2005.06.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Mitsui T, Fischer I, Shumsky JS, Murray M. Transplants of fibroblasts expressing BDNF and NT-3 promote recovery of bladder and hindlimb function following spinal contusion injury in rats. Exp Neurol. 2005 Aug;194(2):410–431. doi: 10.1016/j.expneurol.2005.02.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Tuszynski MH, Grill R, Jones L, Brant A, Blesch A, Low K, Lacroix S, Lu P. NT-3 gene delivery elicits growth of chronically injured corticospinal axons and modestly improves functional deficits after chronic scar resection. Exp Neurology. 2003;181:47–56. doi: 10.1016/s0014-4886(02)00055-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Tobias CA, Shumsky JS, Shibata M, Tuszynski MH, Fischer I, Tessler A, et al. Delayed grafting of BDNF and NT-3 producing fibroblasts into the injured spinal cord stimulates sprouting, partially rescues axotomized red nucleus neurons from loss and atrophy, and provides limited regeneration. Exp Neurol. 2003 Nov;184(1):97–113. doi: 10.1016/s0014-4886(03)00394-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Woerly S. Hydrogels for neural tissue reconstruction and transplantation. Biomaterials. 1993 Nov;14(14):1056–1058. doi: 10.1016/0142-9612(93)90205-g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Woerly S, Plant GW, Harvey AR. Neural tissue engineering: from polymer to biohybrid organs. Biomaterials. 1996 Feb;17(3):301–310. doi: 10.1016/0142-9612(96)85568-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Fischer I, Seil FJ. Progress in Brain Research. Elsevier; 2000. Candidate cells for transplantation into the injured CNS; pp. 253–257. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hobson MI, Green CJ, Terenghi G. VEGF enhances intraneural angiogenesis and improves nerve regeneration after axotomy. Journal of anatomy. 2000 Nov;197(Pt 4):591–605. doi: 10.1046/j.1469-7580.2000.19740591.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Oudega M, Gautier SE, Chapon P, Fragoso M, Bates ML, Parel JM, et al. Axonal regeneration into Schwann cell grafts within resorbable poly(alpha-hydroxyacid) guidance channels in the adult rat spinal cord. Biomaterials. 2001 May;22(10):1125–1136. doi: 10.1016/s0142-9612(00)00346-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Blesch A, Lu P, Tuszynski MH. Neurotrophic factors, gene therapy, and neural stem cells for spinal cord repair. Brain Research Bulletin. 2002;57(6):833–838. doi: 10.1016/s0361-9230(01)00774-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Dalton PD, Flynn L, Shoichet MS. Manufacture of poly(2-hydroxyethyl methacrylate-co-methyl methacrylate) hydrogel tubes for use as nerve guidance channels. Biomaterials. 2002;23(18):3843–3851. doi: 10.1016/s0142-9612(02)00120-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Friedman JA, Windebank AJ, Moore MJ, Spinner RJ, Currier BL, Yaszemski MJ. Biodegradable polymer grafts for surgical repair of the injured spinal cord. Neurosurgery. 2002 Sep;51(3):742–751. discussion 751–742. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Geller HM, Fawcett JW. Building a Bridge: Engineering Spinal Cord Repair. Experimental Neurology. 2002;174(2):125–136. doi: 10.1006/exnr.2002.7865. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Teng YD, Lavik EB, Qu X, Park KI, Ourednik J, Zurakowski D, et al. Functional recovery following traumatic spinal cord injury mediated by a unique polymer scaffold seeded with neural stem cells. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2002 Mar 5;99(5):3024–3029. doi: 10.1073/pnas.052678899. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Iannotti CLH, Yan P, Lu X, Wirthlin L, Xu XM. Glial cell line-derived neurotrophic factor-enriched bridgin transplants promote propriospinal axonal regeneration and enhance myelination after spinal cord injury. Experimental Neurology. 2003;183:379–393. doi: 10.1016/s0014-4886(03)00188-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Schmidt C, Leach Jennie Baier. Neural Tissue Engineering: Strategies for Repair and Regeneration. Annual review of biomedical engineering. 2003;5:293–347. doi: 10.1146/annurev.bioeng.5.011303.120731. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lepore AC, Bakshi A, Swanger SA, Rao MS, Fischer I. Neural precursor cells can be delivered into the injured cervical spinal cord by intrathecal injection at the lumbar cord. Brain Research. 2005;1045(1–2):206–216. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2005.03.050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Mitsui T, Fischer I, Shumsky JS, Murray M. Transplants of fibroblasts expressing BDNF and NT-3 promote recovery of bladder and hindlimb function following spinal contusion injury in rats. Experimental Neurology. 2005;194(2):410–431. doi: 10.1016/j.expneurol.2005.02.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Neuhuber B, Timothy Himes B, Shumsky JS, Gallo G, Fischer I. Axon growth and recovery of function supported by human bone marrow stromal cells in the injured spinal cord exhibit donor variations. Brain Research. 2005;1035(1):73–85. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2004.11.055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Zhang N, Yan H, Wen X. Tissue-engineering approaches for axonal guidance. Brain Research Reviews. 2005;49(1):48–64. doi: 10.1016/j.brainresrev.2004.11.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Klapka NMH. Collagen matrix in spinal cord injury. Neurotrauma. 2006;23:422–435. doi: 10.1089/neu.2006.23.422. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Samadikuchaksaraei A. An overview of tissue engineering approaches for managment of spinal cord injuries. J of NeuroEngineering and Rehabilitation. 2007;4(15) doi: 10.1186/1743-0003-4-15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Heller J, Himmelstein KJ. Poly(ortho ester) biodegradable polymer systems. Methods in enzymology. 1985;112:422–436. doi: 10.1016/s0076-6879(85)12033-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Shive MS, Anderson JM. Biodegradation and biocompatibility of PLA and PLGA microspheres. Adv Drug Deliv Rev. 1997 Oct 13;28(1):5–24. doi: 10.1016/s0169-409x(97)00048-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hoffman AS. Hydrogels for biomedical applications. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences. 2001 Nov;944:62–73. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.2001.tb03823.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lavik E, Teng YD, Snyder E, Langer R. Seeding neural stem cells on scaffolds of PGA, PLA, and their copolymers. Methods in molecular biology (Clifton, NJ) 2002;198:89–97. doi: 10.1385/1-59259-186-8:89. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Langer R, Tirrell DA. Designing materials for biology and medicine. Nature. 2004 Apr 1;428(6982):487–492. doi: 10.1038/nature02388. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Novikova L, Mosahebi A, Wiberg M, Terenghi G, Kellerth JO, Novikova LN. Alginate hydrogel and matrigel as potential cell carriers for neurotransplantation. Journal of biomedical materials research. 2006;77:242–252. doi: 10.1002/jbm.a.30603. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Bakshi A, Fisher O, Dagci T, Himes BT, Fischer I, Lowman A. Mechanically engineered hydrogel scaffolds for axonal growth and angiogenesis after transplantation in spinal cord injury. Journal of neurosurgery. 2004 Oct;1(3):322–329. doi: 10.3171/spi.2004.1.3.0322. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Sung HJCM, Johnson C, Galis Z. The effect of scaffold degradation rate on three-dimensional cell growth and angiogenesis. Biomaterials. 2004 November;25(26):5735–5742. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2004.01.066. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Yoshioka H, Mori Y, Tsukikawa S. Kubota hermoreversible gelation on cooling and on heating of an aqueous gelatin–poly(Nisopropylacrylamide)conjugate. Polymers for Advanced Technologies. 1998;9:155–158. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Huang X, Lowe TL. Biodegradable thermoresponsive hydrogels for aqueous encapsulation and controlled release of hydrophilic model drugs. Biomacromolecules. 2005;6:2131–2139. doi: 10.1021/bm050116t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Lin H, Cheng Y. In-situ thermoreversible gelation of block and star copolymers of poly(ethylene glycol) and poly(N-isopropylacrylamide) of varying architectures. Macromolecules. 2001;34:3710–3715. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Choa JH, Kimb S, Parkc KD, Jungc MC, Yangd WI, Hane SW, Nohe JY, Leeb JW. Chondrogenic differentiation of human mesenchymal stem cells using a thermosensitive poly(N-isopropylacrylamide) and water-soluble chitosan copolymer. Biomaterials. 2004;25:5743–5751. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2004.01.051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Hoffman AS. Applications of thermally reversible polymers and hydrogels in theraputics and diagnostics. Journal of Controlled Release. 1987;6:297–305. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Dalton PD, Flynn L, Shoichet MS. Manufacture of poly(2-hydroxyethyl methacrylate-co-methyl methacrylate) hydrogel tubes for use as nerve guidance channels. Biomaterials. 2002 Sep;23(18):3843–3851. doi: 10.1016/s0142-9612(02)00120-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Ozawa H, Matsumoto T, Ohashi T, Sato M, Kokubun S. Comparison of spinal cord gray matter and white matter softness: measurement by pipette aspiration method. J Neurosurg. 2001 Oct;95(2 Suppl):221–224. doi: 10.3171/spi.2001.95.2.0221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Ozawa H, Matsumoto T, Ohashi T, Sato M, Kokubun S. Mechanical properties and function of the spinal pia mater. Journal of neurosurgery. 2004 Jul;1(1):122–127. doi: 10.3171/spi.2004.1.1.0122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Liu Y, Himes BT, Solowska J, Moul J, Chow SY, Park KI, et al. Intraspinal delivery of neurotrophin-3 using neural stem cells genetically modified by recombinant retrovirus. Exp Neurol. 1999 Jul;158(1):9–26. doi: 10.1006/exnr.1999.7079. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Liu Y, Kim D, Himes BT, Chow SY, Schallert T, Murray M, et al. Transplants of fibroblasts genetically modified to express BDNF promote regeneration of adult rat rubrospinal axons and recovery of forelimb function. J Neurosci. 1999 Jun 1;19(11):4370–4387. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.19-11-04370.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Lombello CB, Malmonge SM, Wada ML. Morphology of fibroblastic cells cultured on poly(HEMA-co-AA) substrates. Cytobios. 2000;101(397):115–122. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Murray M, Kim D, Liu Y, Tobias C, Tessler A, Fischer I. Transplantation of genetically modified cells contributes to repair and recovery from spinal injury. Brain research. 2002 Oct;40(1–3):292–300. doi: 10.1016/s0165-0173(02)00211-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Wu S, Suzuki Y, Kitada M, Kitaura M, Kataoka K, Takahashi J, et al. Migration, integration, and differentiation of hippocampus-derived neurosphere cells after transplantation into injured rat spinal cord. Neuroscience letters. 2001 Oct 26;312(3):173–176. doi: 10.1016/s0304-3940(01)02219-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Lee JKS, Shichinohe H, Ikeda J, Seki T, Hida K, et al. Migration and differentiation of nuclear fluorescence-labeled bone marrow stromal cells after transplantation into cerebral infarct and spinal cord injury in mice. Neuropathology. 2003;23:169–180. doi: 10.1046/j.1440-1789.2003.00496.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Wu S, Suzuki Y, Ejiri Y, Noda T, Bai H, Kitada M, et al. Bone marrow stromal cells enhance differentation of coculture neurosphere cells and promote regeneration of injured spinal cord. J Neurosci Res. 2003;72:343–351. doi: 10.1002/jnr.10587. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Neuhuber B, Timothy Himes B, Shumsky JS, Gallo G, Fischer I. Axon growth and recovery of function supported by human bone marrow stromal cells in the injured spinal cord exhibit donor variations. Brain Res. 2005 Feb 21;1035(1):73–85. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2004.11.055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Byrant Crosslinking Density Influences Chondrocyte Metabolism in Dynamically Loaded Photocrosslinked Poly(ethylene glycol) Hydrogels. Annals of Biomedical Engineering. 2003;32(3):407–417. doi: 10.1023/b:abme.0000017535.00602.ca. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Vernengo AJ, Fussell G, Smith NG, Lowman AM. Evaluation of Novel Injectable Hydrogels for Nucleus Pulposus Replacment. Journal of biomedical materials research. 2007 doi: 10.1002/jbm.b.30844. (accpeted) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Spiller KL, Laurencin SJ, Charlton D, Maher SA, Lowman AM. Superporous hydrogels for cartilage repair: Evaluation of the morphological and mechanical properties. Acta Biomaterialia. 2008 Jan;4(1):17–25. doi: 10.1016/j.actbio.2007.09.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Shibayama MSH, Himes BT, Murray M, Tessler A. Neurotrophin-3 prevents death of axotomized Clarke’s nucleus neurons in adult rat. The Journal of comparative neurology. 1997;390(1):102–111. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]