Abstract

We examined the role of physiological regulation (heart rate, vagal tone, and salivary cortisol) in short-term memory in preterm and full-term 6-month-old infants. Using a deferred imitation task to evaluate social learning and memory recall, an experimenter modeled 3 novel behaviors (removing, shaking, and replacing a glove) on a puppet. Infants were tested immediately after being shown the behaviors as well as following a 10-minute delay. We found that greater suppression of vagal tone was related to better memory recall in full-term infants tested immediately after the demonstration as well as in preterm infants tested later after a 10 minute delay. We also found that preterm infants showed greater coordination of physiology (i.e., tighter coupling of vagal tone, heart rate, and cortisol) at rest and during retrieval than full-term infants. These findings provide new evidence of the important links between changes in autonomic activity and memory recall in infancy. They also raise the intriguing possibility that social learning, imitation behavior, and the formation of new memories are modulated by autonomic activity that is coordinated differently in preterm and full-term infants.

Keywords: Vagal Tone, Cortisol, Memory, Imitation, Prematurity

Preterm infants show poorer habituation to sensory stimulation and require longer exposure to test stimuli before demonstrating learning and memory compared to full-term children starting in the neonatal period (e.g., Howard, Parmelee, Kopp, & Littman, 1976; Sigman & Parmelee, 1974), and extending into infancy (e.g., Rose, Feldman, & Wallace, 1988; Rose, Feldman, & Jankowski, 2001) and childhood (e.g., Rose & Feldman, 1996). Moreover, preterm infants display memory difficulties involving recognition (e.g., Gekoski, Fagen, & Pearlman, 1984; Heathcock, Bhat, Lobo, & Galloway, 2004; Haley, Weinberg, & Grunau, 2006) and recall (de Haan, Bauer, Georgieff, & Nelson, 2000; Rose, Feldman, & Jankowski, 2005). Poorer habituation has been related to alterations in physiological response systems in preterm neonates (e.g., Field, Dempsey, Hatch, Ting, & Clifton, 1979; Rose, Schmidt, & Bridger, 1976; Krafchuk, Tronick, & Clifton, 1983; Gardner & Karmel, 1983). Paradoxically, preterm infants exhibit both hypo and hyper cardiac responses to test stimuli during habituation tasks compared to full-term infants (Rose et al., 1978; Field, 1979; Krafchuk, 1983). This response pattern contributes to the widely held view that preterm infants tend to be physiologically dysregulated or disorganized, which is thought to compromise their ability to attend to and process new information (Field, 1981; Tronick, 1990; Mayes, 2000). Beyond the neonatal period, however, it has remained unclear whether learning and memory performance is attributed to physiological differences in preterm and full-term infants.

Memory

Several important differences in cognitive processing have been observed in preterm infants. First, they tend to process novel information more slowly than full-term infants (e.g., Sigman & Parmelee, 1974). This observation is well established and has systematically been demonstrated using experimental designs that independently evaluate encoding speed and habituation performance (e.g., Rose et al., 2001). Second, preterm infants show specific types of memory processing difficulties involving encoding, consolidation, and retrieval (Gekoski et al, 1984; Haley et al., 2006; Heathcock et al., 2004). For example, Gekoski and colleagues (1984) demonstrated that while 3-month-old preterm infants eventually learned to associate foot kicking with a movement of a mobile after two days of training, they failed to remember the kick-mobile association when tested a week later, unlike full-term infants. This work demonstrates that even when encoding speed is controlled by repeated days of exposure and training, the memory trace formed during encoding is not sufficiently stable to be consolidated for later retrieval. A third difference is that preterm infants have difficulty recalling action sequences after brief delays, particularly multiple actions sequences that require encoding of temporal order (de Haan et al., 2000; Rose et al., 2005)—a difference that persists into childhood (e.g., Luciana, Lindeke, Georgieff, Mills, & Nelson, 1999).

Imitation of novel behaviors after a delay is considered to be a test of memory recall (McDonough, Mandler, Mckee, & Squire, 1995). Memory recall has been demonstrated in full-term infants in the first year of life using the deferred imitation paradigm (Barr, Dowden, & Hayne, 1996; Hayne, Boniface, & Barr, 2000; Herbert, Gross, & Hayne, 2006), in which novel actions or sequences of actions are enacted with props by an experimenter and the infant is expected to imitate those actions after a delay. While premature birth did not affect memory recall for individual target actions at 19 months of age, preterm infants did show poorer memory for ordered actions—specifically, the temporal pairing of actions—compared to full-term infants (de Haan et al., 2000). In another study, using a similar memory task but with a larger longitudinal sample, Rose et al (2005) found that preterm infants showed difficulties recalling both individual actions and order of actions at 12, 20, and 24 months compared to full-term infants. Interestingly, memory performance was highly stable across age, suggesting that important individual differences in how preterm and full-term infants recall events appear to be established in the first year of life.

Physiology and Memory

Individual differences in physiology have been linked to individual differences in cognition and emotion. The parasympathetic branch of the autonomic nervous system has been widely studied in infants as a measurement of these differences. In polyvagal theory, Porges (1995) proposes that parasympathetic activity plays an important role in the coordination of physiological and behavioral response systems, which are needed to maintain homeostasis and enhance growth as well as mobilize energy needed to respond to changes in the environment. At rest, when no immediate challenge is present, greater parasympathetic activity supports growth, slows metabolic activity, and inhibits sympathetic activity. A rapid decrease in parasympathetic activity inhibits the expression of growth factors, speeds up metabolic activity, and increases sympathetic activity (e.g., greater blood flow, faster hear rate, and greater secretion of stress hormones). The capacity to withdrawal parasympathetic activity in response to a challenge is thought to be adaptive and has been linked to cognitive performance (e.g., Bornstein & Suess, 2000; Richards, 1987), emotion regulation (e.g., Bazhenova, Plonskaia, & Porges, 2001; Stifter, Spinrad, & Braungart-Rieker, 1999), and temperament (e.g., Huffman et al., 1998).

Vagal tone is an established autonomic index of parasympathetic activity that reflects respiratory sinus arrhythmia (RSA), which is assumed to be regulated by the nucleus ambiguus in the brain stem. Studies on human infants have examined basal vagal tone and changes in vagal tone during cognitive tasks in relation to attention (DeGangi, DiPietro, Greenspan, & Porges, 1991; Huffman, Bryan, del Carmen, Pedersen, Doussard-Roosevelt, & Porges, 1998), habituation (Bornstein & Suess, 2000), memory recognition (Linnemeyer & Porges, 1986), play exploration (DiPietro, Porges, & Uhly, 1992), and contingency learning (Haley, Grunau, Oberlander, & Weinberg, 2007). These studies indicate that higher basal tone and greater suppression of vagal tone during a challenge facilitate cognitive performance.

There is a growing body of work suggesting that vagal activity plays a specific role in memory consolidation (Flood, Smith, & Morley, 1987; Clark, Naritoku, Smith, Browning, & Jensen, 1999). Several recent studies have shown that greater vagal tone suppression during encoding is related to better short-term memory recall in adults (Hansen, Johnsen, & Thayer, 2002; Johnsen, Thayer, Laberg, Wormnes, Raadal, Skaret, Kvale, Berg, 2003). This relationship is thought to be mediated by neurochemical pathways (e.g., Flood et al., 1987), in which activation of the vagus nerve releases catecholamines (Hassert, Miyashita, & Williams, 2004) such as norepinephrine (NE) and stress hormones, which modulate memory consolidation (Cahill & Alkire, 2003; McGaugh, 1966, 2000).

The effects of premature birth on infant autonomic activity are mixed. There is some evidence that the heart rate patterns in preterm infants differ from those of full-term infants in the neonatal period (e.g., Field et al., 1979; Rose et al., 1976) and in the first year of life (Haley et al., 2007; Coles, Bard, Platzman, & Lynch, 1999). For example, preterm infants at 3 months (age adjusted for preterm birth) show higher resting heart rates and greater reactivity to novel stimulation (Haley et al., 2007; Coles et al., 1999) than full-term infants. This pattern of greater sympathetic activity (i.e., faster heart rates) suggests impaired arousal regulation. In contrast, there is relatively little evidence that vagal tone measures differ among healthy preterm and full-term infants. For example, DiPietro et al (1992) found no major effects of premature birth on vagal tone at rest or in response to novelty in 8-month-old infants.

There is mixed evidence, however, with respect to whether the impact of premature birth alters the relationship between vagal tone and cognitive processes. For example, Richards (1994) showed that that sustained attention (look duration) was predicted by the magnitude of resting RSA levels (an index of parasympathetic activity) at 3, 5, and 6 months of age, regardless of preterm status. In contrast, the relationship between vagal tone and complex cognitive or interactive behaviors appears to differ in preterm and full-term neonates (e.g., Lester, Zachariah, & LaGasse, 1996). For example, Lester et al (1996) found that lower basal vagal tone was related to better behavior (i.e., better self-regulation) in preterm neonates. Interestingly, the opposite pattern was found in full-term infants. There is no previous work that has examined the effects of preterm birth on the relationship between vagal tone and memory recall in infancy.

A second physiological system that plays an important role in both learning and memory processes is the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal (HPA) axis. Activation of the HPA causes the secretion of cortisol, a stress hormone that can directly affect brain function. Chronic activation of the HPA axis and exposure to stress hormones adversely affects physical and mental health. However, acute or moderate exposure to stress hormones may be adaptive and may enhance learning and memory. In normal development, cortisol at baseline and in response to mild perturbations declines in the first year of life (Lewis & Ramsay, 1995; Gunnar, Broderson, Krueger, & Rigatuso, 1996). Preterm infants show an altered developmental trajectory of basal cortisol levels at 3, 6, 8, and 18 months of age compared to full-term infants (Grunau, Haley, Whitfield, & Weinberg, 2006). In the same cohort, cortisol levels at 3 months (corrected age) were related to individual differences in memory patterns in preterm and full-term infants. Specifically, preterm infants showed lower basal cortisol levels and secreted smaller quantities of cortisol than full-term infants and showed positive relationships between cortisol secretion and memory recognition after a 24-hour delay. In contrast, full-term infants secreted greater quantities of cortisol than preterm infants and showed an negative relationship between the cortisol secretion and memory performance (Haley, Weinberg, & Grunau, 2006). Further work is needed to examine whether cortisol modulates memory recall in infancy and whether these relationships differ in pretern and full-term infants.

Current Study

The purpose of this study is to better understand how cardiac vagal tone, heart rate, and cortisol responses during learning of novel behavior and retrieval modulate the infant’s ability to imitate the actions of others and form new memories. By examining the physiological correlates of deferred imitation and whether these correlates and their coordination differ in preterm and full-term infants, this study sheds new light on the links between arousal regulation and social cognition as well as the developmental challenges facing low and high risk infants. Because preterm infants show memory recall impairment in the second year of life (Rose, Feldman, & Jankowski, 2005), we wanted to determine whether memory recall difficulties 1) were present in the first year of life, 2) reflect differences in encoding vs. retrieval processes, and 3) were related to individual differences in the regulation of heart rate, vagal tone, and cortisol, and/or the coordination of these physiological systems.

Given that preterm infants are at greater risk for developing social and cognitive difficulties, we examined the infant’s ability to imitate others and form new memories using a deferred imitation paradigm (Barr et al, 1996). We chose not to include a control group (e.g., infants who were not shown target actions during a demonstration) since the design of the study was based on the priority to evaluate group differences between preterm and full-term infants rather than test the validity of a memory paradigm. Accordingly, we selected a memory task that has well established the validity of the paradigm (Barr et al., 1996).

We extended the work of de Haan (2000) and Rose (2005) in two important ways. First, we evaluated preterm infants who were 6 months old, whereas preterm infants tested in previous work were 12 months old or older. Second, we included an immediate as well as a delayed memory test trial so that we could differentiate the effects of encoding from consolidation and retrieval on memory performance. Since our infants were considerably younger, we used a 10-minute rather than a 15-minute delay to evaluate delayed recall memory. Based on previous literature, we hypothesized that preterm infants would show less imitation behavior than full-term infants. Because slower encoding speed and poorer habituation is an established feature of cognitive development in preterm infants, we expected that preterm infants would show less immediate imitation behavior (reflecting encoding) than full-term infants. Second, we expected that preterm infants would show less imitation behavior during testing after a delay (reflecting consolidation and retrieval) than full-term infants, after adjusting for performance on immediate testing.

Based on prior work we expected that preterm infants would show elevated baseline heart rate and greater heart rate responses to the novel action sequences than full-term infants (Haley et al., 2007; Coles et al., 1999), but no mean group differences in vagal tone (Haley et al., 2007). Based on our longitudinal data (Grunau et al., 2007), we did not expect basal cortisol levels to differ in preterm and full-term infants at 6 months. Based on the assumption that physiological systems operate relatively independently to maintain homeostasis during rest and become more coordinated during a challenge or when stressed (Porges, 1995), and given that preterm infants show greater sympathetic activity at rest (Haley et al., 2007; Coles et al. 1999), we hypothesized that preterm infants would show greater coordination of multiple physiological systems at rest than full-term infants.

Based on the polyvagal theory (Porges, 1995), in which the capacity to withdraw vagal tone in response to a challenge is adaptive, we hypothesized that elevated basal vagal tone and greater suppression of vagal tone during memory testing would predict better memory recall immediately after demonstration and after a delay. As an additional measure of autonomic activity, we examined basal heart rate and changes in heart rate. To examine the possible impact of stress hormones on memory recall, we evaluated the associations between basal cortisol and changes in cortisol levels in relation to imitation behavior as well. To examine vagal tone suppression and changes in heart rate during encoding and retrieval conditions, we calculated three change scores (i.e., demonstration minus baseline; immediate testing minus baseline; and delayed testing minus baseline). Given that preterm infants show slower processing of novel information (e.g., Rose et al., 2001) and show greater sympathetic activity at rest than full-term infants (e.g., Field et al., 1982), we hypothesized that preterm infants would not be able to coordinate physiological and behavioral responses during an immediate memory task and would require additional testing before showing this expected relationship compared to full-term infants.

Methods

Participants

Participants were 83 premature infants born ≤ 32 weeks gestational age and 68 full-term infants seen at 6 months of age. We tested each preterm infant at his or her “corrected age”, i.e., age adjusted for weeks of prematurity (Wilson & Cradock, 2004), which is the convention in this population. Preterm infants were recruited through the Neonatal Intensive Care Unit (NICU) at Children’s and Women’s Health Centre of British Columbia as part of an ongoing program of studies on the effects of premature birth and early pain exposure on regulatory processes and development (Grunau, Holsti, Haley, Oberlander, Weinberg, Solimano, Whitfield, Fitzgerald, & Wayne, 2005; Grunau, Weinberg, & Whitfield, 2004). As part of this larger study, chart reviews from birth to term were carried out (see Table 1). The full-term infants were recruited from the regular nursery at Children’s and Women’s Health Centre of British Columbia and St. Paul’s Hospital in Vancouver, British Columbia. Infants with a major congenital anomaly, neurosensory impairment, or reported maternal drug use during pregnancy were excluded from the study. Mothers were primarily Caucasian (80%), married (80%), and college educated (education: M = 15.9 years). Mothers were on average 33 years of age, with 1.7 children (range = 1–4).

Table 1.

Demographic information of sample by Group (preterm vs. full-term) and Vagal Tone (suppressors vs. non-suppressors)

| Preterm Infants | Full-term Infants | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Suppressors | Non-Suppressors | Suppressors | Non-Suppressors | |

| (n = 38) | (n = 45) | (n = 38) | (n = 30) | |

| Gestational Age at Birth (weeks) | 30.36 (2.31) a | 28.77 (2.57) b | 39.85 (1.03) | 40.25 (1.19) |

| [range] | [22.86-32.86] | [23.71-32.86] | [37.29-41.71] | [37.29-42.14] |

| Birth Weight (grams) | 1455 (474.24) a | 1200.62 (451.78) b | 3514.61 (503.26) | 3587.00 (485.54) |

| Gender (male/female) | 18/20 | 26/19 | 14/24 | 18/12 |

| Days on Mechanical Ventilation | 8.25 (16.03) | 13.00 (18.57) | ----- | ----- |

| Number Skin-breaking procedures | 102.43 (96.27) | 129.32 (89.45) | ----- | ----- |

Note: Mean values with different letters differ significantly, p < .05.

Apparatus

Each infant was tested with a hand-held puppet constructed specifically for the Barr et al. (1996) paradigm and supplied to our lab by Barr. The puppet was a pale grey mouse 30 cm in height and made of soft, acrylic fur. A removable felt mitten (8 cm × 9 cm) was placed over the right hand of each puppet. A jingle bell was secured to the back of the puppet during the demonstration condition and removed for the experimental condition.

Procedure

This study was approved by the Clinical Research Ethics Board, University of British Columbia, and the Children’s & Women’s Health Centre of British Columbia Research Review Committee. Infants were tested at home at a time selected by their caregiver when the infant was likely to be awake and alert. Upon arrival, informed consent was obtained from the parent, and then a basal saliva sample was collected from the infant; a second saliva sample was collected 20 minutes after exposure to the puppet task.

Infants were tested with a delayed imitation puppet task using the procedures of Barr et al. (1996). During each session, the infant was placed on the caregiver’s knee, and he or she held the infant firmly by the hips. Prior to puppet task, the experimenter interacted with the infant for approximately 5 minutes. During this time, baseline heart rate data was collected for 2 minutes. Following this initial interaction, the demonstration (30 seconds), immediate testing (120 seconds), and delayed testing (120 seconds) conditions were conducted.

Demonstration

Once the infant appeared comfortable, the experimenter, kneeling at the caregiver’s feet, placed the puppet over her right hand. The puppet was positioned at the infant’s eye level and in front of the experimenter’s face. The jingle bell was attached to the inside of the mitten. The puppet was held in front of the infant, out of reach, for approximately 10 seconds, until the infant oriented itself to the puppet. The experimenter then removed the mitten from the puppet’s right hand, shook it three times, ringing the bell inside, and replaced it on the puppet’s right hand. This sequence was repeated a total of three times. The entire demonstration lasted approximately 30 seconds.

Test

Imitation behaviors were used to measure memory. Immediate recall was evaluated immediately following the demonstration. Infants were tested with the same puppet that they had seen in the demonstration; however, the bell was no longer present. The infant remained seated on the caregiver’s knee, and the puppet was placed, within reach, approximately 30 centimeters in front of the infant. Infants were given 120 seconds in which to respond from the time they first touched the puppet. Following a 10-minute delay, the delayed recall was tested in a manner identical to that of the immediate test session.

Behavioral coding

A video camera was set up to capture the infant’s facial and bodily movements. Event markers signaling the start of each experimental phase in the heart rate file generated inaudible tones that cued events in the video recording. The video tape recordings were later coded using Noldus’ Observer software (version 5.0). Coders were blinded to the group status and all other information about the infants. Coders noted the presence or absence of three target behaviors measuring imitation during the immediate and delayed tests: (1) remove the mitten, (2) shake the mitten, (3) put the mitten back on the puppet (or attempt to put the mitten back on). Memory scores were computed for immediate and delayed testing based on the most complex action completed (e.g., if the infant removed the mitten and then shook it, the infant received a memory score of 2). Inter-rater reliability was kappa = 0.83 and kappa = 0.77 in the immediate and delayed test conditions, respectively.

Cardiac measures

Heart rate data was recorded from two silver chloride (AgCl) gel electrodes, placed on the infant’s chest prior to testing, using a mini-mitter device (Mini Logger Corporation), which was connected by a serial cable to a laptop computer. Cardiac data was collected during baseline, demonstration, immediate retention, delayed retention, and recovery. Cardiac data were stored offline in heart period format. Heart period files were cleaned and checked for artefacts with MX-Edit software using the methodology of Porges and colleagues (e.g., Doussard-Roosevelt, Porges, Scanlon, Alemi, & Scanlon, 1997). To determine the parasympathetic component of the heart period data, an estimate of cardiac Vna was computed using time series analyses. These analyses extract the component of the heart period within the respiratory frequency band of young infants (0.30 Hertz–1.30 Hertz). The natural logarithm of this variance produces the vagal tone statistic. Vagal tone (Vna) and heart rate values were calculated on sequential 30-second epochs and then averaged values were computed for the baseline, demonstration, immediate retention, and delayed retention tests of the puppet task. To examine changes in autonomic activity, difference scores were calculated by subtracting the baseline average values from each condition (demonstration, immediate test, and delayed test) for heart rate and vagal tone values. Negative difference scores indicated Vna suppression and positive difference scores indicated Vna augmentation or non-suppression. To further examine whether the capacity to suppress vagal tone during encoding was related to subsequent memory performance, infants were assigned to Vna suppression or Vna augmentation groups based on whether they showed suppression or augmenation.

Twenty-three infants (14%) had incomplete cardiac data for baseline, demonstration, and/or memory testing trials due to movement artifact and/or fallen electrodes. A chi-square test indicated that the number of preterm infants (n = 17) with missing cardiac data was not different from the number of full-term infants (n = 6) with missing cardiac data. Although subjects with incomplete data did not differ on memory recall during immediate testing, they did show better memory recall during delayed testing and were more likely to fuss during testing than subjects with complete data. These behavioral differences are likely to have contributed to greater movement artifact and fallen electrodes.

Salivary Samples

Two saliva samples were collected: a basal sample prior to the start of testing and a second sample 20 minutes after the demonstration of the puppet. Saliva samples were obtained using a cotton dental roll without stimulant. Saliva was extracted using a needleless syringe, expressed into a vial, and stored at −20 ° Celsius until assayed in the laboratory of J. Weinberg at the University of British Columbia using the Salametrics High Sensitivity Salivary Cortisol Enzyme Immunoassay Kit for quantitative determination of salivary cortisol (Salimetrics LLC, State College, PA). Intra- and inter-assay coefficients of variation were 2.92% and 3.41% respectively.

Thirty-four infants (20%) had missing cortisol data. A chi-square test indicated that the number of preterm infants with missing cortisol data (n = 24) was not different from the number of full-term infants with missing cortisol data (n = 10). Subjects with missing cortisol data did not differ on any measure of memory recall during immediate or delayed testing compared to infants with complete cortisol data. The reasons for missing cortisol data primarily were due to insufficient amount of saliva collected by the experimenter due to infant dry mouth (n = 24) or to the infant becoming upset (n = 4). In addition, there were subjects with cortisol values that were not detectable by the immunoassay (n = 6).

Statistical Analyses

Physiological and behavioral responses were evaluated using repeated measures ANOVA, correlations, and multiple regressions. To evaluate group differences on immediate and delayed recall, a repeated measures ANOVA was conducted on total imitation scores, with group (preterm vs. full-term) as the between subjects factors and test (immediate vs. delayed) as the repeated measure. Similarly, repeated measures ANCOVA was conducted on autonomic measures (heart rate and vagal tone) with group (preterm and full-term infants) as the between subjects and condition (baseline, demonstration, immediate test, and delayed test) as the repeated measure. Next, bi-varriate correlations were conducted to examine coordination among basal and reactivity indices of heart rate, vagal tone, and cortisol, and imitation behavior. To follow-up the bi-varriate correlation analyses, multiple regressions were conducted to examine the independent contribution of basal and reactivity measures of heart rate, vagal tone, and cortisol in preterm and full-term infants. Finally, we tested the hypothesis that the direction of change in vagal tone regulation during demonstration is related to memory by conducting a repeated measures ANCOVA with group (preterm and full-term infants) and vagal tone (suppress and non-suppress) as the between subject factors and trial (immediate and delayed) as the repeated factor.

Results

Physiology by Group

To examine whether cardiac measures changed significantly during demonstration and imitation trials, two repeated measures ANOVA was conducted for heart rate and vagal tone with term status as the between subjects factor and condition (baseline, demonstration, trial 1, trial 2, and recovery) as the repeated measures. As indicated in Table 2, we found a significant condition effect for heart rate, F(4,536) = 17.24, p < .001. Planned contrasts indicated that infants decreased heart rate from baseline to demonstration and increased from demonstration to immediate imitation trial. There was no effect of group or condition on vagal tone (see Table 2).

Table 2.

Descriptive information of heart rate, vagal tone, and cortisol, and memory by group.

| Measure | Means (SD) | |

|---|---|---|

| Preterm | Full-term | |

| (n = 79) | (n = 65) | |

| Heart Rate (bpm) | ||

| Baseline | 143.76 (10.48) | 140.83 (09.40) |

| Demonstration | 139.23 (10.30) | 137.43 (10.11) |

| Immediate Trial | 143.92 (10.54) | 141.13 (09.59) |

| Delayed Trial | 145.51 (15.27) | 143.46 (10.07) |

| Recovery | 147.33 (14.84) | 145.27 (11.12) |

|

| ||

| (n = 79) | (n = 65) | |

| Vagal Tone (ln/ms) | ||

| Baseline | 3.61 (1.12) | 3.44 (0.87) |

| Demonstration | 3.57 (1.16) | 3.38 (0.97) |

| Immediate Trial | 3.63 (1.19) | 3.40 (0.99) |

| Delayed Trial | 3.53 (1.07) | 3.41 (0.84) |

| Recovery | 3.47 (1.11) | 3.38 (0.89) |

|

| ||

| (n = 72) | (n = 61) | |

| Cortisol (μg/dl) | ||

| Pre-Testing | 0.23 (0.21) | 0.26 (0.26) |

| Post-Testing | 0.22 (0.24) | 0.21 (0.20) |

|

| ||

| (n = 86) | (n = 67) | |

| Negative Affect | ||

| Baseline | 0.02 (0.16) | 0.02 (0.10) |

| Demonstration | 0.07 (0.43) | 0.46 (3.0) |

| Immediate Trial | 0.48 (2.54) | 0.76 (4.90) |

| Delayed Trial | 1.50 (4.28) | 3.22 (7.38) |

| Recovery | 1.02 (3.10) | 1.54 (4.94) |

|

| ||

| (n = 96) | (n = 71) | |

| Memory (%) | ||

| Immediate | 1.66 (1.05) | 1.66 (1.04) |

| Delayed | 1.59 (1.08) | 1.55 (1.13) |

Note 1: There were significant changes in heart rate between conditions but not in vagal tone.

To examine whether cortisol levels changed during the procedure, a repeated ANCOVA was conducted for cortisol with term status as the between subject factor and sample (pre- and post-) as the repeated measure and time of day (morning vs. afternoon) as the covariate. There was a trend for cortisol levels to decline from pre to post samples, p<.1 (see Table 2). There were no group differences in cortisol levels.

Affect by Group and Heart Rate

To examine changes in negative affect, a repeated ANOVA was conducted for affect with term status between subject factor and condition (baseline, demonstration, trial 1, trial 2) as the repeated measure. Results indicated that both preterm and full-term infants changed level of negative affect during the procedure, F(3, 453)=13.80, p<.001. Planned contrasts indicated that infants increased negative affect from immediate to delayed trials. There was a trend for full-term infants to show elevated levels of negative affect on average across the procedure, F(1,151)=3.51, p<.1 (see Table 2).

Correlations between negative affect and heart rate during testing conditions were not significant in preterm infants but were significant in full-term infants. Higher levels of negative affect was associated with elevated levels of heart rate during immediate (r = .32, p<.01) and delayed testing (r=.29, p<.05).

Correlations among physiological variables

Greater coordination of physiological responses was observed in preterm than in full-term infants. First, elevated basal heart rate was associated with lower basal vagal tone and elevated basal cortisol level in preterm but not full-term infants (see Tables 3 and 4). Second, accelerations in heart rate were concurrently related to greater suppression of vagal tone in preterm but not full-term infants in response to immediate and delayed conditions (see Table 3 vs. Table 4). In contrast, both preterm and full-term infants showed some evidence of coordination of heart rate and vagal tone in response to the demonstration.

Table 3.

Associations among study variables in preterm infants.

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 | 13 | 14 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Gestational Age | — | |||||||||||||

| 2. Birthweight | .79** | — | ||||||||||||

| 3. Baseline Heart Rate | −.05 | −.10 | — | |||||||||||

| 4. Δ HR 1 (Demonstration – Baseline) |

.10 | .05 | −.60** | — | ||||||||||

| 5. Δ HR 2 (Immediate – Baseline) |

−.01 | −.04 | −.53** | .66** | — | |||||||||

| 6. Δ HR 3 (Delay – Baseline) |

−.03 | .03 | −.40* | .19 | .29* | — | ||||||||

| 7. Baseline Vagal Tone | −.01 | .15 | −.29** | .11 | .02 | .24* | — | |||||||

| 8. Δ VNA 1 (Demonstration – Baseline) |

−.19† | −.23* | .25* | −.19† | −.17 | −.09 | −.36** | — | ||||||

| 9. Δ VNA 2 (Immediate – Baseline) |

−.12 | −.17 | .43** | −.42** | −.48** | −.17 | −32** | .45** | — | |||||

| 10. Δ VNA 3 (Delay – Baseline) |

−.15 | −.11 | −.15 | .04 | .05 | −.23* | −.47** | .33** | .51** | — | ||||

| 11. Baseline Cortisol | −.02 | .01 | .24* | −23* | −.20† | −.25* | −.09 | .02 | .09 | .03 | — | |||

| 12. Δ Cortisol (time 2 – time 1) |

.05 | .07 | −.14 | .13 | .14 | .11 | .01 | .06 | −.04 | .11 | −.44** | — | ||

| 13. Memory—Immediate | .13 | .14 | .03 | .09 | .07 | .07 | −.07 | −.19† | −.12 | −.18 | −.08 | .02 | — | |

| 14. Memory—Delay | .20* | .14 | −.03 | .21† | .06 | .22† | −.05 | −.03 | −.10 | −.25* | −.05 | .04 | .42** | — |

p<.10

p<.05

p<.01

Table 4.

Associations among study variables in full-term infants.

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 | 13 | 14 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Gestational Age | — | |||||||||||||

| 2. Birthweight | .36** | — | ||||||||||||

| 3. Baseline Heart Rate | −.03 | −.17 | — | |||||||||||

| 4. Δ HR 1 (Demonstration – Baseline) |

.05 | .05 | −.25* | — | ||||||||||

| 5. Δ HR 2 (Immediate – Baseline) |

.06 | .17 | −.49** | −.59** | — | |||||||||

| 6. Δ HR 3 (Delay – Baseline) |

.06 | .01 | −.28* | .32** | .64** | — | ||||||||

| 7. Baseline Vagal Tone | −.15 | .02 | .01 | .03 | −.18 | −.18 | — | |||||||

| 8. Δ VNA 1 (Demonstration – Baseline) |

−.17 | .18 | .09 | −.35** | −.07 | −.15 | −.23† | — | ||||||

| 9. Δ VNA 2 (Immediate – Baseline) |

−.01 | −.07 | .11 | −.36** | −.05 | −.08 | −.46** | .31* | — | |||||

| 10. Δ VNA 3 (Delay – Baseline) |

−.08 | .04 | .12 | −.06 | −.15 | −.17 | −.35** | .31* | .43** | — | ||||

| 11. Baseline Cortisol | −.19† | −.17 | .18 | −.11 | −.08 | −.01 | −.02 | −.07 | .09 | .01 | — | |||

| 12. Δ Cortisol (time 2 – time 1) |

.24† | .28* | −.07 | −.04 | .12 | .05 | −.10 | .14 | .08 | −.05 | −.67** | — | ||

| 13. Memory—Immediate | .01 | −.14 | .05 | −.09 | −.23† | −.02 | .21† | −.14 | −.31* | −.09 | .02 | .01 | — | |

| 14. Memory—Delay | .13 | −.07 | −.03 | .10 | .13 | .14 | −.01 | −.29* | −.09 | −.08 | .11 | −.19 | .42** | — |

p<.10

p<.05

p<.01

Memory by Group

Infants in both preterm and full-term groups showed generally approached the imitation task uninhibited showing response levels that were 2 to 3 times higher than the responses of control infants that have been tested in previous studies and who were not shown the demonstration (e.g., Barr et al., 1996).

The memory scores for immediate and delayed testing did not differ between preterm and full-term infants (see Table 1). Correlations between immediate and delayed memory were relatively stable and similar in both preterm and full-term infants (See Tables 3 and 4). Less than 20 percent of the infants failed to imitate any of the target actions during the immediate test (preterm = 16.7% vs. full-term = 16.9%) and delayed test (preterm = 18.8 % vs. full-term = 22.5%). Over 25 percent of the infants reached for the mitten during the immediate (preterm = 28.1% vs. full-term = 25.4%) and delayed tests (preterm = 30.2% vs. full-term = 28.2%). Over 25 percent of the infants removed the mitten from the puppet during the immediate (preterm = 28.1% vs. full-term = 32.4%) and delayed tests (preterm = 24.0% vs. full-term = 21.1%). Finally, over 25 percent of the infants replaced the mitten on the puppet during the immediate test (preterm = 27.1% vs. full-term = 25.4%) and during the delayed test (preterm = 27.1% vs. full-term = 24.5%).

Correlations among physiology and memory by group

Greater gestational age was associated with better memory in preterm infants. Greater suppression of vagal tone during the delayed task was associated with greater delayed memory (see Table 3). In contrast, greater suppression of vagal tone during immediate task was related to better immediate memory in full-term infants. No other significant associations were observed between physiology and memory variables.

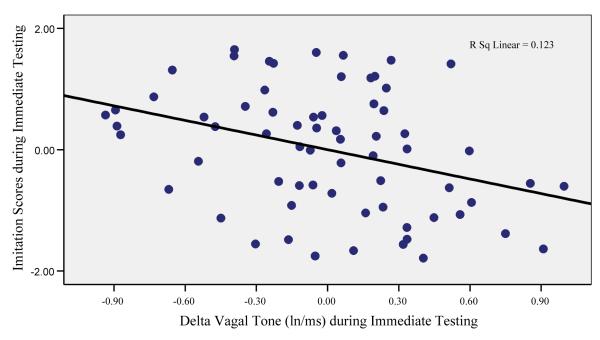

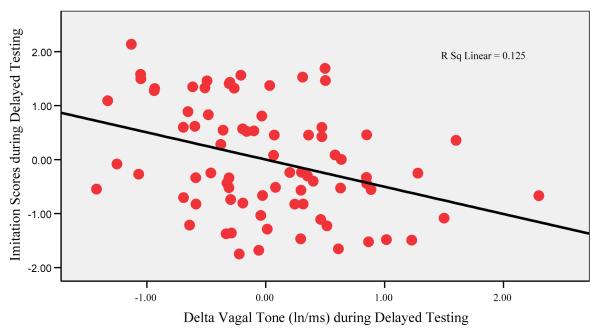

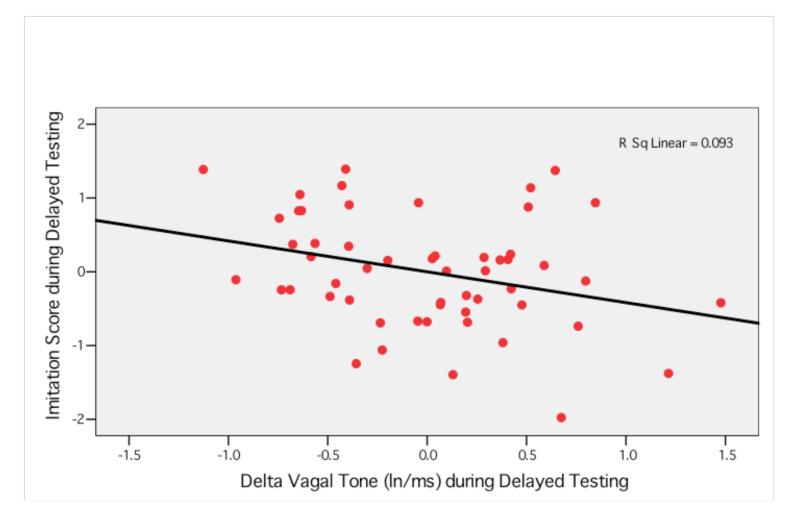

Multiple Regressions by group

To examine the independent contribution of heart rate, vagal tone, and cortisol on immediate and delayed memory, multiple regression analyses were conducted in preterm and full-term infants separately (see Tables 5 and 6). For immediate memory, lower basal vagal tone levels were related to better immediate memory in preterm infants, t = −2.08, p<.05. In full-term infants, greater deceleration in heart rate, t = −2.16, p<.05, and greater suppression of vagal tone, t =−2.20, p<.05, predicted better immediate memory (see Figures 1 and 2). As indicated in Figure 3, greater suppression of vagal tone during immediate testing predicted more imitation behavior during immediate testing. For delayed memory, lower basal vagal tone levels, t = −2.23, p<.05, and greater suppression of vagal tone during delayed testing, t = −3.12, p<.005 (see Figure 3), predicted better delayed memory in preterm infants. There were no significant physiological predictors of delayed memory in full-term infants. Given that the variation in measures of gestational age and birthweight were related to memory performance, we re-ran regression analyses with birthweight entered as covariates and this did not change the earlier results.

Table 5.

Regression models predicting imitation scores during immediate testing in preterm and full-term infants

| Preterm Infants (n = 83, R2 = .06, ns) |

Full-term Infants (n = 67, R2 = .18, p<.05) |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| B | SE | β | B | SE | β | |

| Baseline Vagal Tone | −.12 | .11 | −.14 | .01 | .15 | .01 |

| Δ VNA 2 (Immediate – Baseline) | −.16 | .15 | −.15 | **−.80 | .28 | −.39 |

| Baseline Heart Rate | .01 | .01 | .11 | −.01 | .02 | −.12 |

| Δ HR 2 (Immediate – Baseline) | .01 | .01 | .06 | *−.04 | .02 | −.36 |

| Birthweight | .01 | .01 | .17 | .01 | .01 | −.08 |

p<.05

p<.005

Table 6.

Regression models predicting imitation scores during delayed testing in preterm and full-term infants

| Preterm Infants (n = 79, R2= .16, p<.05 ) |

Full-term Infants (n = 65, R2= .02, ns) |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| B | SE | β | B | SE | β | |

| Baseline Vagal Tone | * −.26 | .12 | −.27 | .03 | .19 | .02 |

| Δ VNA 3 (Delayed – Baseline) | * −.35 | .15 | −.31 | −.10 | .27 | −.05 |

| Baseline Heart Rate | .01 | .01 | .03 | .01 | .02 | .02 |

| Δ HR 3 (Delayed – Baseline) | −.01 | .01 | −.22 | .01 | .02 | .l1 |

| Birthweight | .01 | .01 | .14 | .01 | .01 | −.06 |

p<.05

Figure 1.

Relation between delta vagal tone and imitation behavior during immediate testing in full-term infants.

Note: Greater suppression of vagal tone predicted better imitation scores in full-term infants during immediate testing.

Figure 2.

Relation between delta vagal tone and imitation behavior during delayed testing in preterm infants.

Note: Greater suppression of vagal tone predicted better imitation scores in preterm infants during delayed testing.

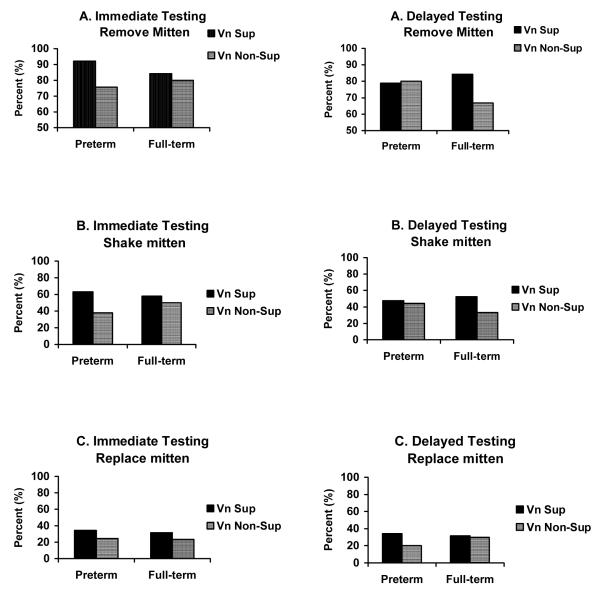

Direction of Vagal Tone Change

To further examine our specific hypothesis that Vna suppression during demonstration would be related to better recall memory, a repeated measures ANCOVA was conducted on the total imitation score with vagal tone (suppressors vs. non-suppressors) and group (preterm and full-term infants) entered as between subject variables and birthweight entered as a covariate. Vna suppressors, regardless of term status, showed greater imitation than non-suppressors, F(1,147) = 4.76, p < .05. We then examined whether vagal tone suppression × group were related to specific imitation behaviors using repeated measures ANOVA. We found a significant group × Vna × condition effect F(1,147) = 5.48, p < .05 (see Figure 4). One-way ANOVAs indicated that preterm Vna suppressors removed the glove more often than preterm Vna non-suppressors during immediate recollection, p < 0.01, and there was a trend for full-term Vna suppressors to remove the glove more than full-term non-suppressors during the delayed imitation, p < .10. For shaking the glove, we found a main effect of vagal tone suppression, F(1,147) = 4.71, p < .05 (see Figure 4). Preterm Vna suppressors removed the glove more often than preterm Vna non-suppressors during immediate recollection, p < .01, and there was a trend for full-term Vna suppressors to remove the glove more than full-term non-suppressors during the delayed imitation, p < .10. No term status or Vna regulation effects were found for replacing the glove.

Figure 4.

The percent of infants who removed the mitten (Panel A), shook the mitten (Panel B), and/or replaced the mitten on the puppet (Panel C) during immediate and delayed testing as a function of group and vagal tone suppression.

Discussion

The goal of this study was to examine the relationships between physiology and memory recall and the extent to which these relationships might differ in preterm and full-term infants at 6 months (corrected for age from conception). The results support several of our hypotheses. First, we found evidence that greater suppression of vagal tone is linked to enhanced memory recall in infancy. Second, we found that full-term infants can suppress vagal tone in relation to memory recall during immediate testing but that preterm infant fail to demonstrate this expected relationship until given a repeated test. We also found that lower basal vagal tone was related to better delayed memory in preterm infants. Finally, we found that vagal tone, heart rate, and cortisol were more tightly coupled in preterm than in full-term infants at rest and during retrieval. Overall, these findings underscore the perspective that important differences in the coordination of physiology alter the concordant relationships between physiology and memory recall in preterm and full-term infants.

Memory

We evaluated immediate and delayed imitation behavior in order to differentiate memory processes related to encoding, consolidation, and retrieval. Performance during immediate testing was assumed to reflect encoding, whereas performance after a delay was assumed to reflect memory consolidation and retrieval. The proportion of infants (preterm and full-term) who showed recall was the same as reported previously with this paradigm in infants of the same age (Barr et al., 1996). We found that memory recall performance did not differ among preterm and full-term infants. While our finding is consistent with de Haan et al (2000), it is not consistent with Rose et al. (2005). One major reason for this discrepancy is that in our study and de Haan (2000) tested immediate as well as delay memory while Rose et al (2005) tested only delay memory. Immediate testing provides an opportunity for infants to practice what they have learned, which may have allowed preterm infants to perform as well as full-term infants on the delay test. The task complexity in the study by Rose et al (2005) was greater than the tasks used by de Haan and the current study. These methodological differences may have made the imitation paradigm used in the current study less sensitive to the differences expected in memory recall in preterm compared to full-term infants.

Despite finding no effects of preterm birth on memory performance, we did find that gestational age was positively related to memory recall after a delay within the group of preterm infants, which is consistent with prior work (e.g., de Haan, 2000). In contrast, Rose et al (2005) found that gestational age was related to memory performance in preterm infants at 24 and 36 months but not at 12 months. This is somewhat surprising given the relative stability in memory performance found from 1 to 2 and 1 to 3 years of age in preterm infants (Rose et al., 2005). Differences in task complexity and variation in the preterm sample among these studies may help explain the disparity among the findings. Unlike the task used in the current study, the task used by Rose et al (2005) is perhaps less sensitive to individual differences in memory recall at 12 months of age. Although the means for gestational age were similar between the two studies, the range in our study included younger infants (e.g., 23-32 weeks vs. 25-36 weeks).

Physiology

We found no group difference on any single physiological parameter. The lack of group differences in our study on heart rate, vagal tone and cortisol are consistent with previous work at this age (e.g., DeGangi et al., 1990; Grunau et al., 2007); however, most studies typically report significant differences between preterm and full-term infants in the first year of life. One major reason for not finding any group differences in physiology is that 6 months of age represents a turning point in biological organization and development. For example, infants show a developmental decline between 4 and 6 months in basal cortisol levels and an increase in basal vagal tone. This normal shift could potentially blur differences between preterm and full-term infants on any single measure of physiology. In addition, there is some evidence in the literature that group differences in heart rate between preterm and full-term infants appear at birth and continue at 2 and 4 months but not 6 months (Richards, 1994).

In contrast with our findings with single measures of physiology, we did find that the pattern of relationships among physiological variables differed in preterm and full-term infants at rest and during retrieval. Faster heart rates were strongly associated with greater suppression of vagal tone and elevated cortisol levels in preterm but not full-term infants. Greater coherence between RSA and heart rate in preterm compared to full-term infants has been reported by Richards (1994). This tighter coupling of physiological responses in the preterm infants might suggest greater sympathetic tone in that group. In previous studies of full-term infants, multiple physiological systems (e.g., autonomic and stress hormones) at rest were weakly or not associated, and only became coordinated (i.e., correlated) during stressful challenges. Further, we found that accelerations in heart rate were associated with greater suppression of vagal tone during immediate (r = −.44, p<.01) and during delayed testing (r= −.22, p<.05) in preterm but not in full-term infants. Again, this co-activation pattern of heart rate and vagal tone during retrieval suggests greater sympathetic activity in preterm than in full-term infants. Does this pattern reflect vagal activity that helps the organism respond to the environment (e.g., vigilance, supported by greater vagal tone suppression), rather than maintaining homeostasis (e.g., recovery, supported by greater basal vagal tone activity)? Is there any cognitive cost associated with this seemingly hyper-alert pattern of autonomic activity in preterm infants?

Physiology and Memory

Based on polyvagal theory (Porges, 1995), we expected that suppression of vagal tone during a challenge would predict better cognitive performance. Previous studies have shown that greater vagal tone suppression during a task is related to better attention (e.g., Porges, 1972), faster habituation (Bornstein 2000), and better recognition memory (Linnmyer, Porges, et al., 1986) in six month olds. The current results extend these past findings by showing that vagal tone suppression during a task is related to better memory recall. Importantly, we also found that preterm infants failed to coordinate vagal tone suppression and imitation behavior until after a 10 minute delay. In contrast, full-term infants were able to demonstrate the expected relationship between vagal tone suppression and enhanced memory immediately after demonstration.

Why were preterm infants unable to coordinate vagal tone and behavior immediately like full-term infants? One possibility is that preterm infants are under greater stress than full-term infants, which compromises their ability to respond physiologically to novel information (Field, 1980; Mayes, 2000; Tronick, 1990). Porges (1995) has proposed that greater coordination of physiological systems at rest may indicate greater stress in high risk populations, which is based on the assumption that physiological systems should be loosely coupled or relatively independent at rest but become more coordinated under challenge. Consistent with these proposals, we found a co-activation pattern in basal physiology in preterm (e.g., faster heart rate, lower vagal tone, and elevated cortisol) but not in full-term infants. Previous studies have shown that behaviorally, children who are born extremely preterm back off from novel cognitive challenges, even after controlling for intellectual ability (Grunau 2003; Whitfield et al 1997). In addition, we found that lower basal vagal tone was related to better delayed memory in preterm infants. This relationship is similar to previous findings. For example, Lester et al (1996) found that lower basal vagal tone was related to better behavior (i.e., better self-regulation) in preterm neonates. Interestingly, the opposite pattern was found in full-term infants. Taken together with our present findings, this suggests that altered autonomic regulation and/or additional stress may limit cognitive capacity independently of possible cognitive impairment in preterm infants.

Another possibility for why full-term infants did not show the relationship between vagal suppression and memory during the delayed testing is that they were more emotionally aroused than the preterm infants. We found that negative affect significantly increased between immediate and delayed testing trials for all infants. In addition, we found that greater levels of heart rate was associated with greater levels of negative affect in the full-term infants and not in the preterm infants. The increase in negative affect could be influencing the full-term infant’s autonomic regulation of visceral state and interfering with their cognitive performance though increases in sympathetic tone. This possibility could also address why full-term infants did not show superior memory performance compared to preterm infants in our study.

A third explanation for these results is that the memory trace that is modulated by vagal activity during encoding is weaker or more fragile in preterm than in full-term infants. For example, we found that suppression of vagal tone during demonstration of the puppet was related to better delayed memory in full-term infants but not in preterm infants (see Figure 4). In contrast, vagal tone suppression during demonstration was related to better immediate memory recall in preterm infants but not in full-term infants. This pattern in full-term infants is consistent with recent work in adults (e.g., Hansen et al., 2003) and therefore we speculate that suppression of the vagal system during encoding of novelty is linked to better short-term memory consolidation and retrieval in full-term infants. In addition, we found that suppression of vagal tone during the puppet demonstration was significantly correlated with an increase in heart rate in the full-term (r = −.35, p<.05) but not in the preterm infants (r = − .19, p<.1). This indicates that preterm infants are less able to coordinate their autonomic responses during the encoding of novel information. Whether this affects long-term memory storage due to a weaker memory trace, and whether preterm infants are slower to coordinate vagal tone and imitation behavior because they are physiologically stressed or because they are cognitively impaired will require further study.

Cortisol

The secretion of stress hormones such as cortisol during a learning task has long been thought to play an important role in the modulation of memory processes (e.g., McGaugh, 1966, 2000). Recent studies in adults (e.g., Abercrombie et al., 2003) and infants (Haley et al., 2006) support this view. In our previous work (Haley et al., 2006), moderate secretion of cortisol during encoding was related to better 24-hour memory at 3 months in preterm and full-term infants. During the learning phase, however, cortisol and cognitive behavior were unrelated, which we interpreted to mean that cortisol plays a relatively specific role in memory consolidation rather than encoding or retrieval. In the current study, cortisol was not related to memory when tested immediately after demonstration of the puppet or after a delay. The brief interval used to test memory after a delay in the puppet task may not be long enough to capture the slow actions of cortisol on memory consolidation. Future work should test the role of cortisol on long-term memory consolidation in infants of this age by extending the time interval of the delay from 10 minutes to several hours or days.

Limitations/Future Directions

Although infants performed within the normal range on the memory task based on prior studies (Barr et al., 1996), it is not possible to claim that this performance reflects processes associated with memory per se given the lack of a control group in the current study. To study memory processes it would be necessary to compare the performance of infants in a control group who are now shown the target action. This would enable the possibility of removing spontaneous behavior unrelated to memory processes in the analysis. Accordingly, the current study provides encouraging support for taking further steps to examine the relationships between physiology and memory in preterm and full-term infants. The goal of the current study, however, was to establish whether any associations among physiology, imitation, and memory exist, and to what extent these relations might differ in preterm and full-term infants. Given that we expected to find memory differences between preterm and full-term infants, the current study indicates that the design of testing memory after a 10-minute delay is insufficient to detect memory differences in preterm and full-term infants. Future studies should use a more challenging memory task to study associations between physiology and memory (e.g., 24 hour delay or greater complexity in the target items to-be-remembered).

Another question raised by our study is why was baseline heart rate and vagal tone not correlated in the full-term infants. It could be that the 90 seconds of baseline data was an insufficient duration for a reliable measure —given the procedure used to compute the estimates of vagal tone. However, this possibility is not supported by the fact that preterm infants showed the expected inverse relationship between heart rate and vagal tone. In prior studies that did not find the expected association it was often during a challenging condition and thought to reflect increased sympathetic tone (e.g., Bazhenova, Stroganova, Doussard-Roosevelt, Posikera, & Porges, 2007). The unfamiliarity of the infant to the experimenter might have been more overly arousing for the full-term infants than for preterm infants. Future studies should be advised to collect a longer duration of baseline heart rate data (e.g., 2-4 minutes) and perhaps to collect baseline data during conditions that are familiar to the infant. Further work is clearly needed to further establish the relationships between regulation of vagal tone and memory in young infants.

Summary

In summary, our primary findings were that vagal suppression was related to enhanced memory performance and that preterm infants showed different concordant patterns of autonmic and behavior responses than full-term infants. Specifically, full-term infants demonstrated the expected relationship between vagal tone suppression and enhanced memory performance during immediate testing in contrast to preterm infants—who failed to demonstrate this relationship until after a 10 minute delay. Further, preterm infants showed tighter coupling of vagal tone, heart rate, and cortisol during rest and retrieval than full-term infants. Although these findings require replication and should be viewed somewhat cautiously due the limitations discussed above, they provide new evidence of the important links between changes in autonomic activity and memory recall in infancy. These findings also raise the intriguing possibility that social learning, imitation behavior, and the formation of new memories are modulated by autonomic activity that is coordinated differently in preterm and full-term infants.

Acknowledgments

This work was primarily funded by the National Institute for Child Health and Human Development grant HD39783 (REG), with additional funding from the Canadian Institutes for Health Research grant MOP42469 (REG) and the Human Early Learning Partnership (HELP) grants 20R41341 (JW) and 2OR31739 (REG) through the B.C. Ministry for Children and Families, and from Michael Smith Foundation for Health Research. Dr. Grunau is supported by a Distinguished Scholar Award from the Child and Family Research Institute, affiliated with the University of British Columbia and the Children’s and Women’s Health Centre of BC. Dr. Oberlander is supported by a HELP Senior Career Award and has the R. Howard Webster Professorship in Early Child Development (UBC, College of Interdisciplinary Studies). We would like to express our appreciation to Drs. Barr and Hayne for providing the test materials and for consultation on the procedures. We are grateful to the families who participated and for the invaluable dedication of the research staff.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Reference

- Abercrombie HC, Kalin NH, Thurow ME, Rosenkranz MA, Davidson RJ. Cortisol variation in humans affects memory for emotionally laden and neutral information. Behavioral Neuroscience. 2003;117:505–516. doi: 10.1037/0735-7044.117.3.505. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anderson P, Doyle LW. Neurobehavioral outcomes of school-age children born extremely low birth weight or very preterm in the 1990s. Journal of American Medical Association. 2003;289:3264–3272. doi: 10.1001/jama.289.24.3264. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barr R, Dowden A, Hayne H. Developmental changes in deferred imitation by 6- to 24-month-old infants. Infant Behavior and Development. 1996;19:159–170. [Google Scholar]

- Barr R, Hayne H. Age-relatedchangesinimitation: Implications for memorydevelopment. In: Rovee-Collier C, Lipsitt LP, Hayne H, editors. Progressininfancyresearch. Vol. 1. Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, Inc.; Mahwah, NJ: 2000. pp. 21–67. [Google Scholar]

- Barr R, Rovee-Collier C, Campanella J. Retrieval protracts deferred imitation by 6-month-olds. Infancy. 2005;7:263–283. doi: 10.1207/s15327078in0703_3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bazhenova OV, Plonskaia O, Porges SW. Vagal reactivity and affective adjustment in infants during interaction challenges. Child Development. 2001;72:1314–1326. doi: 10.1111/1467-8624.00350. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bazhenova OV, Stroganova TA, Doussard-Roosevelt JA, Posikera IA, Porges SW. Physiological responses of 5-month-old infants to smiling and blank faces. International Journal of Psychophysiology. 2007;63:64–76. doi: 10.1016/j.ijpsycho.2006.08.00. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bornstein MH, Suess PE. Physiological self-regulation and information processing in infancy: Cardiac vagal tone and habituation. Child Development. 2000;71:273–287. doi: 10.1111/1467-8624.00143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cahill L, Alkire MT. Epinephrine enhancement of human memory consolidation: Interaction with arousal at encoding. Neurobiology of Learning and Memory. 2003;79:194–198. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7427(02)00036-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clark KB, Naritoku DK, Smith DC, Browning RA, Jensen RA. Enhanced recognition memory following vagus nerve stimulation in human subjects. Nature. 1999;2:94–98. doi: 10.1038/4600. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coles CD, Bard KA, Platzman KA, Lynch ML. Attentional response at eight weeks in prenatally drug-exposed and preterm infants. Neurotoxicology and Teratology. 1999;21:527–537. doi: 10.1016/s0892-0362(99)00023-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Colombo J. On the neural mechanisms underlying individual differences in infant fixation duration: Two hypotheses. Developmental Review. 1995;15:97–135. [Google Scholar]

- DeGangi GA, DiPietro JA, Greenspan SI, Porges SW. Psychophysiological characteristics of the regulatory disorder infant. Infant Behavior and Development. 1991;14:37–50. [Google Scholar]

- De Haan M, Bauer PJ, Georgieff MK, Nelson CA. Explicit memory in low-risk infants aged 19 months born between 27 and 42 weeks of gestation. Developmental Medicine and Child Neurology. 2000;42:304–312. doi: 10.1017/s0012162200000542. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DiPietro JA, Porges SW, Uhly B. Reactivity and developmental competence in preterm and full-term infants. Developmental Psychology. 1992;28:831–841. [Google Scholar]

- Doussard-Roosevelt JA, McClenny BD, Porges SW. Neonatal cardiac Vna and school-age developmental outcome in very low birth weight infants. Developmental Psychobiology. 2001;38:56–66. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Doussard–Roosevelt JA, Porges SW, Scanlon JW, Alemi B, Scanlon KB. Vagal regulation of heart rate in the prediction of developmental outcome for very low birth weight preterm infants. Child Development. 1997;68:173–186. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Field T. Infant arousal, attention, and affect during early interactions. In: Lipsitt L, Rovee-Collier C, editors. Advances in infancy research. Vol. 1. Ablex; Norwood, N.J.: 1981. [Google Scholar]

- Field T, Dempsey JR, Hatch J, Ting G, Clifton RK. Cardiac and behavioral responses to repeated tactile and auditory stimulation in preterm and term neonates. Developmental Psychology. 1979;15:406–416. [Google Scholar]

- Flood JF, Smith GE, Morley JE. Modulation of memory processing by cholecystokinin: Dependence on the vagus nerve. Science. 1987;236:832–834. doi: 10.1126/science.3576201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fox NA, Porges SW. The relation between neonatal heart period patterns and developmental outcome. Child Development. 1985;56:28–37. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gardner J, Karmel B. Attention and arousal in preterm and full-term neonates. In: Field T, Sostek A, editors. Infants born at risk: physiological, perceptual, and cognitive processes. Grune & Stratton; New York: 1983. [Google Scholar]

- Gekoski MJ, Fagen JW, Pearlman MA. Early learning and memory in the preterm infant. Infant Behavior and Development. 1984;7:267–275. [Google Scholar]

- Graham FK, Clifton RK. Heart rate change as a component of the orienting response. Psychological Bulletin. 1966;65:305–320. doi: 10.1037/h0023258. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grunau RE. Self-regulation and behavior in preterm children: Effects of early pain. In: McGrath PJ, Finley GA, editors. Pediatric pain: Biological and social context. Pain research and management. IASP Press; Seattle: 2003. p. 26. [Google Scholar]

- Grunau RE, Haley DW, Weinberg J, Whitfield MF. Re-programming of hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal response in preterm infants. J. Pediatrics. 2007;150:151–156. [Google Scholar]

- Grunau RE, Holsti L, Haley DW, Oberlander T, Weinberg J, Solimano A, Whitfield MF, Fitzgerald C, Yu Wayne Neonatal procedural pain exposure predicts lower cortisol and behavioral reactivity in preterm infants in the NICU. Pain. 2005;113:293–300. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2004.10.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grunau RE, Weinberg J, Whitfield MF. Neonatal procedural pain exposure and preterm infant cortisol response to novelty at 8 months. Pediatrics. 2004;114:e77–e84. doi: 10.1542/peds.114.1.e77. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gunnar MR, Broderson L, Krueger K, Rigatuso J. Dampening of adrenocortical responses during infancy: Normative changes and individual differences. Child Development. 1996;67:877–889. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haley DW, Stansbury K. Infant stress and parent responsiveness: Regulation of behavior and physiology during still-face and reunion. Child Development. 2003;74:1534–1546. doi: 10.1111/1467-8624.00621. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haley DW, Grunau RE, Oberlander TF, Weinberg J. Contingency learning and reactivity in preterm and full-term infants at 3 months. 2007. Manuscript under review. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Haley DW, Weinberg J, Grunau RE. Cortisol, contingency learning, and memory in preterm and full-term infants. Psychoneuroendocrinology. 2006;31:108–117. doi: 10.1016/j.psyneuen.2005.06.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hansen AL, Johnsen BH, Thayer JE. Vagal influence on working memory and attention. International Journal of Psychophysiology. 2003;48:263–274. doi: 10.1016/s0167-8760(03)00073-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hassert DL, Miyashita T, Williams CL. The effects of peripheral vagal nerve stimulation at a memory–modulating intensity on norepinephrine output in the basolateral amygdala. Behavioral Neuroscience. 2004;118:79–88. doi: 10.1037/0735-7044.118.1.79. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hayne H, Boniface J, Barr R. The development of declarative memory in human infants: Age-related changes in deferred imitation. Behavioral Neuroscience. 2000;114:77–83. doi: 10.1037//0735-7044.114.1.77. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heathcock JC, Bhat AN, Lobo MA, Galloway JC. The performance of infants born preterm and full-term in the mobile paradigm: Learning and memory. Physical Therapy. 2004;84:808–821. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herbert J, Gross J, Hayne H. Age-related changes in deferred imitation between 6 and 9 months of age. Infant Behavior & Development. 2006;29:136–139. doi: 10.1016/j.infbeh.2005.08.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Howard J, Parmelee A, Kopp CB, Littman B. A neurologic comparison of preterm and full term infants at term conceptional age. Pediatrics. 1976;88:995–1002. doi: 10.1016/s0022-3476(76)81062-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huffman LC, Bryan YE, del Carmen R, Pedersen FA, Doussard-Roosevelt JA, Porges SW. Infant temperament and cardiac vagal tone: Assessments at twelve weeks of age. Child Development. 1998;69:624–635. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnsen BH, Thayer JF, Laberg JC, Wormnes B, Raadal M, Skaret E, Kvale G, Berg E. Attentional and physiological characteristics of patients with dental anxiety. J. Anxiety Disord. 2003;17:75–87. doi: 10.1016/s0887-6185(02)00178-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krafchuk EE, Tronick EZ, Clifton RK. Behavioral and cardiac responses to a sound in preterm infants varying in risk status: A hypothesis of their paradoxical reactivity. In: Field TM, Sostek A, editors. Infants born at risk: Physiological , perceptual, and cognitive processes. Grune & Stratton; New York: 1983. [Google Scholar]

- Larson MC, White BP, Cochran A, Donzella B, Gunnar M. Dampening of the cortisol response to handling at 3 months in human infants and its relation to sleep, circadian cortsiol activity, and behavioral distress. Developmental Psychobiology. 1998;33:327–337. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lester BM, Boukydis CFZ, LaGasse L. Cardiorespiratory reactivity during the brazelton scale in term and preterm infants. Journal of Pediatric Psychology. 1996;21:771–783. doi: 10.1093/jpepsy/21.6.771. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lewis M, Ramsay DS. Developmental change in infants’ responses to stress. Child Development. 1995;66:657–670. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.1995.tb00896.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Linnemeyer SA, Porges SW. Recognition memory and cardiac Vna in month-old infants. Infant Behavior and Development. 1986;9:43–56. [Google Scholar]

- Luciana M, Lindeke L, Georgieff M, Mills M, Nelson CA. Neurobehavioral evidence for working-memory deficits in school-aged children with histories of prematurity. Developmental Medicine & Child Neurology. 1999;41:521–533. doi: 10.1017/s0012162299001140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mayes LC. A developmental perspective on the regulation of arousal states. Seminars in Perinatology. 2000;24:267–279. doi: 10.1053/sper.2000.9121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McDonough L, Mandler JM, McKee RD, Squire LR. The deferred imitation task as a nonverbal measure of declarative memory. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 1995;92:7580–7584. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.16.7580. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McGaugh JL. Time-dependent processes in memory storage. Science. 1966;153:1351–1358. doi: 10.1126/science.153.3742.1351. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McGaugh JL. Memory—A century of consolidation. Science. 2000;287:248–251. doi: 10.1126/science.287.5451.248. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moore GA, Calkins SD. Infants’ vagal regulation in the still-face paradigm is related to dyadic coordination of mother-infant interaction. Developmental Psychology. 2004;40:1068–1080. doi: 10.1037/0012-1649.40.6.1068. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Porges SW. Physiologic correlates of attention: A core process underlying learning disorders. Pediatrics Clinics of North America. 1984;31:371–385. doi: 10.1016/s0031-3955(16)34573-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Porges SW. Orienting in a defensive world: Mammalian modifications of our evolutionary heritage. A Polyvagal Theory. Psychophysiology. 1995;32:301–318. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-8986.1995.tb01213.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Porges SW, Doussard-Roosevelt JA, Portales AL, Greenspan SI. Infant regulation of the vagal “brake” predicts child behavior problems: A psychobiological model of social behavior. Developmental Psychobiology. 1996;2:697–712. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1098-2302(199612)29:8<697::AID-DEV5>3.0.CO;2-O. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Richards JE. Infant visual sustained attention and respiratory sinus arrhythmia. Child Development. 1987;58:488–496. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Richards JE. Baseline respiratory sinus arrhythmia and heart rate responses during stustained visual attention in preterm infants from 3 to 6 months of age. Psychophysiology. 1994;31:235–243. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-8986.1994.tb02212.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rose SA, Feldman JF, Jankowski JJ. Attention and recognition memory in the first year of life: a longitudinal study of preterms and full-terms. Developmental Psychology. 2001;37:135–151. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rose SA, Feldman JF. Memory processing speed in preterm children at eleven years: A comparison with full terms. Child Development. 1996;67:2005–2021. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rose SA, Schmidt K, Bridger WH. Cardiac and behavioral responsivity to tactile stimulation in premature and full-term infants. Developmental Psychology. 1976;12:311–320. [Google Scholar]

- Rose SA, Feldman JF, Wallace IF. Individual differences in infant’s information processing: reliability, stability, and prediction. Child Development. 1988;59:1177–1197. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rose SA, Feldman JF, Jankowski JJ. Recall memory in the first three years of life: a longitudinal study of preterm and term children. Developmental Medicine & Child Neurology. 2005;41:521–533. doi: 10.1017/S0012162205001349. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rovee-Collier CK, Sullivan MW, Enright M, Lucas D, Fagen JW. Reactivation of infant memory. Science. 1980;208:1159–1161. doi: 10.1126/science.7375924. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sigman M, Parmelee AH. Visual preferences of four-month-old premature and full-term infants. Child Development. 1974;45:959–965. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stolarova M, Whitney H, Webb SJ, deRegnier R, Georgieff MK, Nelson CA. Electrophysiological brain responses of six-month-old low risk premature infants. Infancy. 2003;4:437–450. [Google Scholar]

- Tronick E, Scanlon KB, Scanlon JW. Protective apathy, a hypothesis about the behavioral organization and its relation to clinical and physiologic status of the preterm infant during the newborn period. Clinics in Perinatology. 1990;17:125–135. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilson SL, Cradock MM. Review: Accounting for prematurity in developmental assessment and the use of age-adjusted scores. Journal of Pediatric Psychology. 2004;29:641–650. doi: 10.1093/jpepsy/jsh067. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]