Abstract

Atomoxetine is a central norepinephrine reuptake inhibitor used to treat attention deficit hyperactivity disorder. We tested the effects of atomoxetine upon the heart rate (HR) and mean arterial blood pressure (mBP) response to aversive conditioning. In Protocol 1 the mBP and HR responses to a stress (15 sec. tone followed by shock) were tested in 8 Sprague Dawley rats given saline pretreatment for 3 days; the rats’ responses were then tested for 3 additional days following atomoxetine (1 mg/kg, sc). Atomoxetine decreased (p < 0.05) baseline mBP from 128 ± 11 mm Hg (mean ± SD) to 117 ± 19 mm Hg; baseline HR slowed from 380 ± 23 bpm to 351 ± 21 bpm. The mBP increase to acute stress was similar after saline vs. after drug, but the peak was attained more slowly. After atomoxetine HR tended to slow during stress rather than accelerate. In Protocol 2 the cardiovascular responses were tested (n=6) for 3 days post-saline and for 3 days after a higher dose of atomoxetine (2 mg/kg, sc). The average HR acceleration during the last 10 seconds of the stress after saline (+7.5 ± 14.7 bpm) was replaced by a HR slowing (−6.2 ± 10.5 bpm). We conclude that drug treatment (a) decreases baseline sympathetic tone and/or elevates cardiac parasympathetic tone; (b) slows sympathetic arousal to acute stress without changing its magnitude; and, (c) enables the emergence of elevated parasympathetic tone during the stress. These autonomic consequences are consistent with atomoxetine’s anxiolytic and transient sedative effects.

Keywords: attention deficit hyperactivity disorder, ADHD, classical Pavlovian conditioning

INTRODUCTION

Drugs that have specific central nervous system effect(s) as well as demonstrable, clinically desirable therapeutic actions upon disruptive behaviors have attracted a great deal of attention. Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder (ADHD) is one such behavior that reportedly is found in up to 7% of school age children (American Psychiatric Association, 2000). This condition is associated with increased motor activity, distraction, restlessness, and inattention to task. Alterations of central dopamine and norepinephrine (NE) metabolism are thought to be causally involved in the etiology of ADHD. Traditional pharmacotherapy of ADHD relies heavily upon psychostimulants (e.g., d-amphetamine), but more recently the selective, centrally-acting NE reuptake inhibitor, atomoxetine, has been reported to be efficacious in the treatment of ADHD (reviewed in Barton, 2005; see also Bymaster, et al., 2002; Gehlert, et al., 1995; Simpson and Plosker, 2004). Despite the widespread clinical use of this agent in children, adolescents and adults, assessments of atomoxetine’s effects on autonomic control of arterial blood pressure (BP) and heart rate (HR) at rest and during acute stress are virtually lacking. This study examines quantitatively the effects of atomoxetine upon the cardiovascular response to a classically conditioned stress response in rat, and interprets these findings in the light of what is known of the autonomic control of the conditional response pattern. A preliminary report of these findings has been published (Li, et al., 2006).

METHODS

Animals

Sprague-Dawley rats obtained from Harland Industries (Indianapolis, IN) weighing 428 ± 49 g. (mean ± SD) were used in protocols 1 (n=16) and 2 (n=6). Each animal was allowed free access to water and regular rat chow except during the time of behavioral training and testing. The protocol was performed in accordance with the guidelines for animal experimentation described in the “Guiding Principles for Research Involving Animals and Human Beings” (American Physiological Society, 2002), and was approved by the University of Kentucky Animal Care and Use Committee.

Protocols

Protocol 1 tested the stability of the BP and HR response to acute behavioral stress over time and the effects of a 1 mg/kg dose of atomoxetine on that response. Radio telemetry units were implanted to measure aortic BP (see below), and the animals allowed at least 2 weeks to recuperate. Next, they were trained in the behavioral conditioning procedure (see below), and then randomly assigned to a vehicle control group (Group 1; n=8) or a drug group (Group 2; n=8). In an initial series of trials rats in both groups were given saline for three consecutive days (i.e., days 1-3) in a volume (1 ml/kg, sc) equal to that eventually given to the drug group (see below); the saline was given each day 10 minutes before a set of conditioning trials for which the BP and HR conditional response was assessed. Animals in the drug group were then given atomoxetine (1 mg/kg in a 1 mg/ml solution, sc) for three more consecutive days (i.e., days 4-6). As above, the drug was given 10 minutes before onset of the daily conditioning trials. The BP and HR responses were again determined. Conversely, the control rats were given saline, as before, prior to their second series of conditioning tests (i.e., days 4-6).

Protocol 2 was conducted as a follow-up to the findings from the first protocol which, in fact, established stability of the learned BP and HR response pattern over time and indicated that investigating the consequences of a higher dose of atomoxetine would be informative (see “Results”). Telemetry devices were implanted, as before. Once trained, the animals were given either saline or atomoxetine (2 mg/kg, 2 mg/ml, sc) on each of three days; saline or drug was given 10 minutes before the behavioral tests. On the ensuing three days the animals previously given saline were injected with the drug, and vice versa. Three rats were given saline first, while three were initially given atomoxetine.

Behavioral conditioning to stressful stimuli

Animals were behaviorally trained using classical (i.e., Pavlovian) conditioning according to a previously described technique (Randall, et al., 1994). Briefly, the animals were habituated for 1-2 hours daily for several days to handling and restraint in a comfortable cloth sock. Each rat was then exposed daily to five trials of a 15-second pulsed tone (CS+; on for 0.064 s, off for 0.16 s) and another five trials of an uninterrupted tone (i.e., non-pulsed; CS−) that was otherwise identical to the pulsed-sound. CS+ and CS− were presented in pseudorandom pairs (e.g., …CS+, CS−,CS−, CS+…). On this initial training day only the last (i.e., 5th) pulsed tone was reinforced with the 0.5 sec. shock (i.e., to establish that the tone itself was “neutral”); the shock was delivered via bipolar electrodes held by a plastic cuff placed around the subject’s tail prior to each day’s trials. The shock was adjusted to the lowest value that caused the rat to flinch and squeak which was usually 0.2 mA and never exceeded 0.3 mA. Training continued for two additional days, but with each CS+ shock reinforced. A minimum of five minutes was allowed between presentations of successive trials to allow the studied variables to return to baseline. Each rat was removed from the sock at the end of each daily session and was returned to the animal quarters.

Surgery

All surgical procedures were performed under pentobarbital anesthesia (65 mg/kg ip) with aseptic techniques appropriate for rodent survival surgery. The abdominal aorta was exposed via a laparotomy. The tip of the catheter of the Data Science International (DSI) probe (model TA11PA-C40) was inserted into the aorta via puncture such that its tip pointed toward the heart; the catheter was secured in the vessel by a spot of surgical glue. The body of the probe was sutured to the interior abdominal wall. The incision was closed and the rat returned to its home cage after it aroused and became mobile.

Data Acquisition

Data were acquired and analyzed using software developed by ViiSoftware (Lexington, KY). During data sessions mean arterial BP and HR were calculated from the pulsatile BP signal digitized at 500 Hz. Individual files were created for each conditioning trial starting 15 seconds before tone onset and terminating 15 seconds after the end of a tone. Data were recorded over at least five trials of each tone. Individual CS+ trials were ensemble averaged for each rat to construct a “high resolution” analysis of the conditional response for that animal (Randall, et al., 1994); likewise, CS− trials were ensembled for each animal. Finally, a group average was constructed by averaging these high resolution files for each condition (e.g., saline trials or drug trials) for each tone (i.e., CS+ or CS−) across each rat in a given treatment. For example, the assessment of the HR and BP response to the CS+ condition after atomoxetine for Group 1 trials was ultimately derived from a total of 120 individual trials (i.e., 8 rats × 3 days testing/rat × 5 CS+ trials/day). This process reliably assesses quantitative and temporal aspects of the response (Randall, et al., 1993).

Data analysis

The amplitude of the BP and HR conditional response was calculated relative to the beat-by-beat average BP (or HR) during the pre-tone baseline period. The various facets of the conditional response are defined below and in Figure 1. An initial, short-latency increase in BP (i.e., the “first component” or C1) was assessed in terms of the peak change during the initial ~2 seconds of the tone (pk C1) as well as the average change during C1 (avg C1). To quantify the time course of the arterial BP response the time at which pk C1 was attained (tpkC1) was determined from the high resolution analyses for each rat; time was measured relative to the beginning of a trial (i.e., t=0, beginning of pre-tone baseline). The smaller amplitude, but more sustained C2 pressor response, was taken as the average change during the last 10 sec. of the tone. Finally, we assessed the peak BP after shock delivery (i.e., the unconditional response, or UR). The average HR change during C2 was determined as well as the peak HR change vs control during C2. Data are expressed as mean ± standard deviation. A three-way analysis of HR or mean BP findings was performed for the conditioning data [ANOVA: Trial (CS+/CS−) by Condition (baseline, C1 avg, C2) by Drug (saline/atomoxetine)] with post-hoc analyses to parse out specific aspects of the response, as is explained in “Results” for the respective tests. Statistical significance was accepted for p < 0.05.

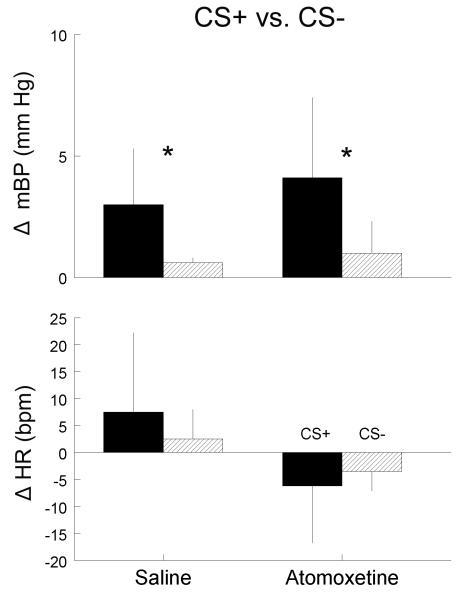

Figure 1.

Group average (n=8 rats) of change (△) in mean arterial blood pressure (mBP; top panel) and in heart rate (HR, bottom panel) before (0-15 sec), during CS+ tone (15-30 sec.; dark bar on abscissa) and after ½ second shock (given at 30 sec.) in Protocol 1 rats following saline on days 1, 2 and 3 (black) and again following saline on days 4, 5 and 6 (blue). For each rat mBP and HR data files from each of 15 CS+ trials were ensembled to create a “high resolution file” for that animal. The high resolution files were then ensembled across the 8 animals. For C1, the point where mBP initially peaks (pk C1) and the time span over which the change in mBP is averaged (avg C1) are indicated. The thin blue arrow extending downward to the X-axis from pk C1 (i.e., blue line: days 4,5 and 6) indicates the time at which peak C1 was attained (tpkC1) for the second set of trials; this value was not significantly different for the two sets of trials (see Table 1). The time range for the C2 components of the mBP conditional response and the C2 component of the HR response are also demarcated, as is the unconditional response (UR) to the shock. Note that there were no significant changes in the response pattern across time.

RESULTS

General Observations

Each individual who worked with the rats independently noted that the animals were quieter and less fidgety in the restraint sock following atomoxetine administration. Conversely, there was no subjective evidence that the subjects were disoriented or otherwise behaviorally abnormal after drug administration.

Protocol 1

The control animals in Protocol 1 that were given saline each of the first 3 days, and then, again, saline for days 4-6 were tested to establish whether pre-tone (i.e., baseline) BP and HR changed significantly across time and to test for the stability of the conditional response across repeated presentations of CS+ and CS−. Pre-tone (i.e., baseline) mean arterial blood pressure (mBP) and HR did not differ between Days 1-3 and Days 4-6 (Table 1). Figure 1 is the group average for CS+ for rats given saline on both Days 1-3 (black) and Days 4-6 (blue); data are plotted as changes (△) relative to the average pre-tone value. The figure indicates the peak C1 (pk C1). The tip of the arrow indicates the precise time at which the peak value was achieved; this time (i.e., tpkC1) was determined for each rat separately for both saline and drug trials. The figure also indicates the time range over which average C1 (avg C1) and C2 mBP were calculated, as well as the average C2 HR; finally, it also shows the unconditional mBP response (UR) to the shock. Table 1 gives the numerical values for each of these changes. There were no significant differences in any measured aspect of the conditional or unconditional response across time (i.e., repetition of the conditioning routine).

Table 1.

Baseline, Conditional and unconditional changes ± SD in mBP and HR for CS+ for Control Group in Protocol 1

| Days 1 - 3 (Saline) | Days 4 - 6 (Saline) | |

|---|---|---|

| mean Arterial BP (mm Hg) | ||

| pre-tone baseline | 123 ± 12 | 117 ± 9 |

| peak initial change (pk C1) | +6.1 ± 4.0 | +7.0 ± 4.4 |

| avg. initial change (avg. C1) | +1.7 ± 1.6 | +3.9 ± 2.2 |

| avg. time to peak C1 (tpkC1, sec) | 16.4 ± 0.5 | 16.5 ± 1.1 |

| avg. sustained change (C2) | +2.3 ± 3.4 | +3.1 ± 3.5 |

| unconditional response (UR) | +23.6 ± 13.2 | +28.0 ± 9.2 |

| Heart Rate (bpm) | ||

| pre-tone baseline | 392 ± 28 | 372 ± 25 |

| peak change during C2 | +11.9 ± 26.5 | +22.5 ± 17.1 |

| avg. sustained change (C2) | +1.4 ± 12.3 | +11.1 ± 13.4 |

See Figure 1 for definitions of pk C1, avg C1, C2 and UR

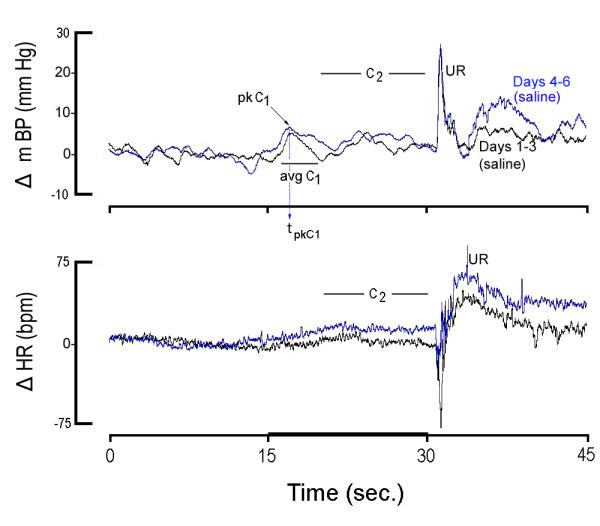

The drug group in Protocol 1 was given saline before each set of 5 CS+ and 5 CS− trials on days 1-3 and atomoxetine (1 mg/kg, sc) before the sets of trials on days 4-6. Pre-tone (i.e., baseline) mean arterial pressure decreased (paired-t7 = 2.35; Table 2) post-saline vs. post-atomoxetine (left panel, Figure 2). Likewise, drug administration significantly (t7 = 3.26) decreased baseline HR (Table 2 and right panel, Figure 2). Table 2 also summarizes the conditional cardiovascular response (changes vs. baseline) and the time to peak C1 BP (tpkC1). There were no differences in the magnitude of the conditional arterial BP response in the animals after saline vs. after drug administration. Conversely, the time required to reach the peak C1 arterial pressure increased from 16.7 ± 0.9 sec (i.e., 1.7 sec. from the start of the tone) for saline trials to 17.5 ± 1.1 sec. (t7 = 2.654) for drug trials. The longest and largest component of the HR conditional response is the change concurrent with the C2 BP change (see Figure 1 for time delineation). The average HR during the last 10 sec. of the CS+ tone (i.e., C2) tended to slow following atomoxetine relative to baseline during this time (−2.3 ± 10.7 bpm), rather than the usual acceleration (+7.4 ± 17.8 bpm), but this difference (i.e., between saline vs. drug conditions) was not significant. Conversely, the change in peak HR change during C2 from acceleration to deceleration was significant (paired-t7 = 4.42; Table 2).

Table 2.

Conditional and unconditional changes ± SD in mBP and HR for CS+ for Drug Group in Protocol 1

| Days 1 - 3 (Saline) | Days 4 - 6 (Atomoxetine) | |

|---|---|---|

| mean Arterial BP (mm Hg) | ||

| pre-tone baseline | 128 ± 11 | 117 ± 19* |

| peak initial change (pk C1) | +9.4 ± 7.5 | +10.1± 4.2 |

| avg. initial change (avg. C1) | +4.0 ± 3.7 | +3.8 ± 4.2 |

| avg. time to peak C1 (tpkC1, sec) | 16.7 ± 0.9 | 17.5 ± 1.1* |

| avg. sustained change (C2) | +4.6 ± 3.5 | +4.2 ± 3.8 |

| unconditional response (UR) | +27.5 ± 12.5 | +25.7 ± 8.7 |

| Heart Rate (bpm) | ||

| pre-tone baseline | 380 ± 23 | 351 ± 21* |

| peak change during C2 | +23.0 ± 15.2 | −26.3 ± 26.5* |

| avg. sustained change (C2) | +7.4 ± 17.8 | −2.3 ± 10.7 |

= p < 0.05, saline vs. atomoxetine See Figure 1 for definitions of pk C1, avg C1, C2 and UR.

Figure 2.

Baseline mean arterial blood pressure (mBP, left) and heart rate (HR, right) during 15 sec. preceding tone for trials conducted in each of the 8 rats in Protocol 1. Data are taken after saline and after atomoxetine administration. Atomoxetine induced a significant decrease in both baseline mBP and in HR. * = p < 0.05, saline vs. atomoxetine

Protocol 2

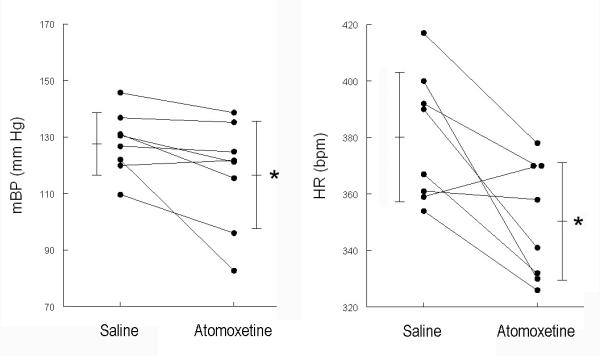

Because protocol 1 demonstrated stability of the response over time, protocol 2 was simplified by using each rat as its own control (i.e., each rat received saline prior to three daily sessions and atomoxetine prior to 3 daily sessions). A higher dose of drug (2 mg/kg) was tested in these animals to determine if trends observed in Protocol 1 might emerge as significant with a higher dose. Figure 3 is analogous to Figure 2, and uses the same ordinate scales for ease of comparison. Resting HR decreased (Table 3; paired-t5 = 4.142) relative to saline treatment following drug treatment. The difference in mean arterial pressure across the two conditions was not significant (i.e., it is apparent from Figure 3 that arterial BP increased in one of the 6 animals after receiving the drug).

Figure 3.

Baseline mean arterial blood pressure (mBP, left) and heart rate (HR, right) during 15 sec. preceding tone for trials conducted in each of the 6 rats in Protocol 2. Data are taken after saline and after atomoxetine administration. Atomoxetine induced a significant decrease in baseline HR; change in mBP was not statistically significant. * = p < 0.05, saline vs. atomoxetine.

Table 3.

Conditional and unconditional changes ± SD in mBP and HR for CS+ for Saline and Drug Groups in Protocol 2

| Saline | Atomoxetine | |

|---|---|---|

| mean Arterial BP (mm Hg) | ||

| pre-tone baseline | 111 ± 12 | 107 ± 9 |

| peak initial change (pk C1) | +6.6 ± 1.7 | +8.0 ± 4.5 |

| avg. initial change (avg. C1) | +3.4 ± 1.1 | +4.0 ± 2.6 |

| avg. time to peak C1 (tpkC1, sec) | 16.1 ± 0.8 sec | 17.1 ± 1.1* |

| avg. sustained change (C2) | +3.0 ± 2.3 | +4.1 ± 3.3 |

| unconditional response (UR) | +27.2 ± 15.2 | +25.1 ± 8.8 |

| Heart Rate (bpm) | ||

| pre-tone baseline | 372 ± 20 | 345 ± 12* |

| peak change during C2 | +13.3 ± 18.3 | −17.2 ± 8.0* |

| avg. sustained change (C2) | +7.5 ± 14.7 | −6.2 ± 10.5* |

= p < 0.05, saline vs. atomoxetine See Figure 1 for definitions of pk C1, avg C1, C2 and UR.

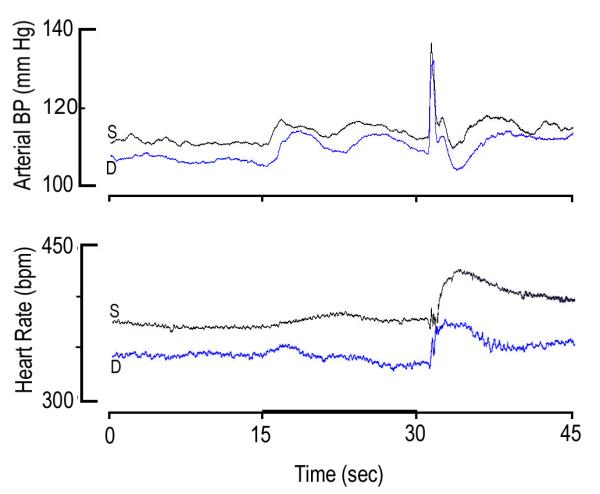

Figure 4 plots the mBP (top) and HR (bottom) conditional response to CS+ in the rats following treatment with saline (S; black) or drug (D; blue). Each line in this figure is an average across all 6 rats tested in Protocol 2. The corresponding changes for the various components of the cardiovascular conditional response are given in Table 3. Aside from the overall pressure difference in the two states, there were no visually obvious differences in the magnitudes of the various components of the mBP conditional response and, in fact, three-way ANOVA found no significant interactions. As in Protocol 1, however, the initial peak in mBP, tpkC1, following saline was achieved later (17.1 ± 1.1 sec.) following atomoxetine than it was following saline (16.1 ± 0.8 sec.; paired-t5 = 5.423). Visual inspection of the bottom portion of the figure reveals that HR increased relative to baseline during CS+ in the saline tests, but that it decreased following atomoxetine. [The initial cardio-acceleration probably results from a sudden, short-lived, but intense, burst in SNA (Li, et al., 1997; Randall, et al., 1994).] This HR slowing post-atomoxetine occurred despite the obvious overall decrease in baseline HR in the drug condition: it cannot be an “initial value” effect. This visual impression is confirmed in that there were significant findings for a three-way analysis on HR change [ANOVA: Trial (CS+/CS−) by Condition (C1 avg, C2) by Drug (saline/atomoxetine)] with a significant Trial × Condition × Drug interaction (F1,1,5 = 17.8). By way of parsing these findings, a two-way analysis [Drug (Saline/atomoxetine) by condition (pre-tone, C1 avg, C1 peak, C2)] yielded a significant drug effect (F4,20 = 54.9) and drug × condition interaction (F4,20 = 7.25). In fact, comparison of the average change in HR relative to baseline during C2 for the saline trials (+7.5 ± 14.7 bpm ) to that following drug (−6.2 ± 10.5 bpm) was significant (paired-t5 = 4.20). Recall that these are 10 sec. averages, not peak changes. Not surprisingly, therefore, the difference in the peak change during C2 from acceleration after saline vs. deceleration after drug (Table 3) was also significant (paired-t5 = 4.95). Finally, the amplitude and dynamics of the unconditional cardiovascular response were similar after saline vs. after drug.

Figure 4.

Group average (n=6 rats) of actual values of mean arterial blood pressure (mBP; top panel) and of heart rate (HR, bottom panel) before (0-15 sec), during CS+ tone (15-30 sec.; dark bar on abscissa) and after ½ second shock (given at 30 sec.) in rats in Protocol 2 following saline (S; black) on days 1, 2 and 3 (S; black) and following drug (D; blue) on days 4, 5 and 6 (D, 2 mg/kg; blue). Overall mBP was lower following atomoxetine, but there were no significant differences in the amplitudes of the components of the conditional or unconditional arterial blood pressure response. Conversely, it is clear that the initial peak in mBP was attained later after drug (blue) than after saline (black). In addition, HR was significantly lower following drug, and HR slowed during last 10 seconds of tone (dark bar, abscissa) after atomoxetine (blue), rather than the usual acceleration (black).

Discrimination

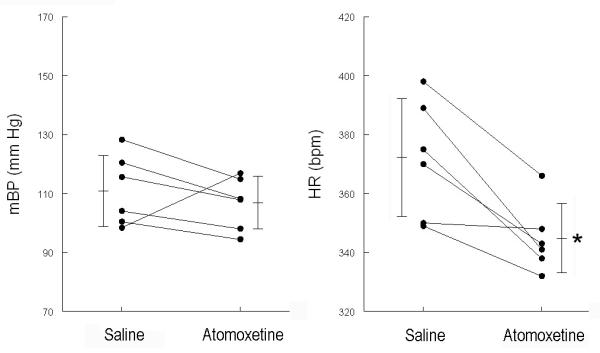

The only difference between the CS+ and the CS− is that the former is pulsed, while the latter is steady (i.e., the tones are of the same frequency and intensity). The animals, therefore, cannot tell whether a given trial will be shock-reinforced until > ca. 0.06 second after the beginning of any given trial, so there is at least an initial cardiovascular response to CS− (Randall, et al., 1993, 1994). A well-trained animal is able to discriminate between CS+ and CS−; this discrimination typically is most reliably seen in larger C2 BP change to CS+ vs. CS− (El-Wazir, et al., 2005; Randall, et al., 1993, 1994), though we examined here the C2 HR change as well. Figure 5 affirms that the C2 BP component showed discrimination both after saline and after atomoxetine. In fact, ANOVA on these data with main effects for CS+/CS− and for saline/drug showed significant findings only for the former (F1,5 = 7.94). The C2 HR component failed to achieve significant discrimination, though post-saline and post-drug the change during CS− tended to be smaller than during CS+. Conversely, though the ANOVA findings for CS+/CS− were not significant, that for saline/drug was (F1,5 = 13.47), as was the interaction (F1,5 = 8.76).

Figure 5.

Average (n=6 rats) ± SD change in mean arterial blood pressure (mBP, top panel) and in heart rate (HR, bottom panel) during C2 component for CS+ (black) and CS− (cross hatched) trials. Data on left are for rats in Protocol 2 after saline administration; data on right are after atomoxetine (2 mg/kg, right). Drug had no effect on discrimination between shock reinforced CS+ tone and neutral CS− tone. * = p < 0.05, CS+ vs. CS−.

DISCUSSION

Prior studies of drugs such as atomoxetine have understandably focused upon effects on behavior, but the possible consequences of exposure to such drugs upon autonomic function are also important. In that context, while some attention has been given in the literature to effects of long-term atomoxetine treatment upon baseline BP and HR (reviewed in Simpson and Plosker, 2004; see also Michelson, et al., 2003; Wernicke, et al., 2003), virtually no attention has been given to possible effects upon regulation of circulatory function. We report here for the first time that acute administration of atomoxetine significantly (a) decreases baseline arterial pressure and heart rate; (b) slows the dynamics of the initial mBP increase in response to the acute stress; and (c) changes the HR conditional response from acceleratory to deceleratory. As we explain below, the most remarkable finding in this study is that the drug appears to change the rat’s autonomic response to the acute behavioral challenge during the last 10 seconds of the conditional stimulus (i.e., during C2). We further suggest that the changes a to c, above, are the heretofore unappreciated autonomic counterparts of the commonly recognized sedative and anxiolytic actions of the drug.

Interpretation of Unchanged Amplitudes of Arterial BP Components of Stress Response

Interpretation of these findings in light of autonomic function is possible because of insights from our previous studies that were conducted using identical paradigms and equipment, and personnel common across all experiments. We have reported that C1 is preceded by a short-latency, large-amplitude, but transient “sudden burst” in SNA (Randall, et al., 1994). This is an “open loop” response; as such, it appears not to be influenced by the biofeedback mechanism of the baroreflex, and can be used to assess the functional relationship between changes in SNA and BP (Burgess, et al., 1997). In fact, the C1 BP increase is proportional to the sudden burst (Burgess, et al., 1997; Randall, et al., 1994), and is the result of an increase in peripheral vascular resistance with cardiac output essentially unchanged (Li, et al., 1998). We may reliably infer, therefore, from the similarity in the amplitude of C1 in the saline vs. drug-treated state that atomoxetine had little or no effect on the amplitude of the SNA burst. The longer delay in attaining pk C1 following atomoxetine with little to no effect on the size of the mBP change, in turn, suggests that the dynamics of the rat’s arousal to the suddenly perceived stress, including the sympathetic component thereof, are slowed by the drug, though the magnitude is unchanged. We suggest that the increase in the time at which pk C1 was attained (tpkC1) is an autonomic correlate of atomoxetine’s blunting arousal to external stimuli when used clinically to treat ADHD. We should also note that the similarity of the mBP unconditional response after saline vs. after drug suggests that atomoxetine did not alter the rat’s perception of the shock.

SNA is modestly elevated over control throughout C2 in the Sprague Dawley rat (Randall, et al., 1994). As with the C1 pressor change, the similarity in size between the C2 BP change following saline and following drug is consistent with a similarity in SNA increase in the two states. The lowering of baseline BP, with the similarity in the amplitudes of both the C1 and the C2 BP increase, suggest that resting sympathetic tone is decreased, but the amplitude of the sympathetic arousal to the acute stress is essentially unchanged.

Interpretation of Change in HR response to Acute Stress from Acceleration to Deceleration

The direction of the C2 HR change differs across rat strains: it is modestly acceleratory in Sprague Dawley (Randall et al., 1993, 1994), and deceleratory in Wistar-Kyoto, the spontaneously hypertensive rat (Li, et al., 1997), the borderline hypertensive rat (Brown, et al., 1999), and in the lean and obese Zucker strains (El-Wazir, et al., 2008). Strain differences in the psychophysiological response to behavioral situations have been documented (e.g., in passive-avoidance; see Paré, 1993), but a shift in the physiological response to a behavioral challenge within a given strain, such as we report here, is remarkable. What, then, might account for the change in the HR response during the last 2/3 of the tone? The robust C2 HR slowing in the 9-11 week old lean strain of the Zucker rat is essentially eliminated by atropine, but it is not significantly altered by β-adrenergic blockade (El-Wazir, et al., 2008). Extending this observation to our present preparation, and allowing that the SNA arousal was relatively unchanged (see above), the HR slowing seen after atomoxetine must have resulted from the emergence of an increase in parasympathetic influence during the latter seconds of the CS+.

The overall lowering of baseline BP and HR after atomoxetine suggests that the drug drops baseline sympathetic tone and / or increased baseline parasympathetic tone. This may be explained most parsimoniously as secondary to the overall decrease in activity we subjectively discerned after drug administration, which is consistent with earlier observations that the drug has a “transient sedative effect” in rat (Moran-Gates, et al., 2005) as well as the belief that it combats increased anxiety that often accompanies ADHD (Geller, et al., 2005; Kratochvil, et al., 2005).

While the interpretation of the effects of atomoxetine in terms of autonomic function are immediate extensions of our previous work, further interpretation of the ultimate mechanism is inferential. The most reasonable explanation of the basis of the increased parasympathetic tone during C2 is activation of the baroreflex by the concomitant sympathetically mediated increase in arterial BP. In fact, we have suggested that the C2 pressor event is secondary to an upward resetting of the baroreflex (Randall, et al., 1994). Accordingly, HR slowing is largest (for those strains we have tested) in the SHR, which also manifests the largest C2 pressor change (Li, et al., 1997).

Lack of Effect of Atomoxetine on Discrimination

Autonomic function aside, one might anticipate that atomoxetine treatment would enhance discrimination between CS+ and CS−. A decrease in the relative amplitude of the C2 BP change during CS− in the drug-treated vs. saline-treated subjects would indicate enhanced discrimination, but no such difference was observed (Figure 5). However, we tested the drug in rats after they had been fully trained in the discriminative paradigm. It will be necessary to test discrimination when the animals are given the agent during the acquisition phase of the study to make more definitive conclusions in this regard.

Perspectives

The magnitude of the HR change to the behavioral arousal (i.e., CS+) in the Sprague-Dawley rat is modest, and the effects of atomoxetine, though statistically significant, on baseline HR and on the conditional response are not large. We argue that the physiologic significance resides not in the magnitude of the cardiovascular effects, but in the apparent shift in the animal’s physiologic status from relatively high baseline sympathetic tone (e.g., higher HR) and sympathetic arousal during acute stress (e.g., cardio-acceleration, despite the BP increase) in the control state to a decreased sympathetic / increased parasympathetic basal state (lower baseline HR) and emergence of the expression of an increase in parasympathetic / decreased sympathetic response during arousal (i.e., an HR slowing to arousal - despite the lower baseline HR) after atomoxetine. Clinical use of the drug in the treatment of ADHD reportedly reduces inattentive and hyperactive and impulsive symptoms (e.g., Michelson, et al., 2003), but much less has been reported on its effects on autonomic function. To the degree that the rat is a viable model of the human (e.g., the quieting and the delay in time to peak response), it is possible that similar autonomic effects attend the drug’s use in humans. If so, this could be an important secondary consequence of the drug’s use worthy of additional attention.

In summary, we suggest the following new insights into the actions of atomoxetine: Acute administration of the agent in rat (a) decreases baseline sympathetic tone and / or elevates cardiac parasympathetic tone; (b) slows the emergence of sympathetic arousal secondary to acute behavioral stress without significantly altering the ultimate magnitude of that response; and, (c) allows the expression of elevated parasympathetic tone during the stress, possibly secondary to changes in baroreflex function. These autonomic consequences of the drug are consistent with atomoxetine’s affective actions of blunting behavioral arousal via its anxiolytic and transient sedative effects.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

Supported by grants RO1 NS39774 and T32 HL 072743 from the National Institutes of Health.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

REFERENCES

- American Physiological Society Guiding principles for research involving animals and human beings. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol. 2002;283:R281–R283. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.00279.2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- American Psychiatric Association . Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders. 4th Ed American Psychiatric Association; Washington, DC: 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Barton J. Atomoxetine: a new pharmacotherapeutic approach in the management of attention deficit/hyperactivity disorder. Arch. Dis. Child. 2005;90(Suppl 1):i26–i29. doi: 10.1136/adc.2004.059386. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown DR, Li S-G, Lawler JE, Randall DC. Sympathetic control of BP and BP variability in borderline hypertensive rats on high- vs. low-salt diet. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol. 1999;277:R650–R657. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.1999.277.3.R650. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burgess DE, Hundley JC, L,i S, Randall DC, Brown DR. Multifiber renal sympathetic nerve activity recordings predict mean arterial blood pressure in unanesthetized rat. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol. 1997;273:R851–R857. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.1997.273.3.R851. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bymaster FP, Katner JS, Nelson DL, Hemrick-Luecke SK, Threlkeld PG, Heiligenstein JH, Morin SM, Gehlert DR, Perry KW. Atomoxetine increases extracellular levels of norepinephrine and dopamine in prefrontal cortex of rat: a potential mechanism for efficacy in attention deficit / hyperactivity disorder. Neuropsychopharm. 2002;27:699–711. doi: 10.1016/S0893-133X(02)00346-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- El-Wazir YM, Li S-G, Williams DT, Sprinkle AG, Brown DR, Randall DC. Differential acquisition of specific components of a classically conditioned arterial blood pressure response in rat. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol. 2005;289:R784–R7898. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.00018.2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- El-Wazir YM, Li S-G, Smith R, Silcox DL, Brown DR, Randall DC. Parasympathetic Response to Acute Stress is Attenuated in Young Zucker Obese Rats. Autonomic Neuroscience: Basic and Clinical. 2008;143:33–39. doi: 10.1016/j.autneu.2008.07.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gehlert DR, Schober DA, Hemrick-Luecke SK, Krushinski J, Howbert JJ, Robertson DW, Fuller RW, Wong DT. Novel halogenated analogs of tomoxetine that are potent and selective inhibitors of norepinephrine uptake in brain. Neurochem Int. 1995;26:47–52. doi: 10.1016/0197-0186(94)00113-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Geller D, Donnelly C, Lopez F, Rubin R, Newcorn J, Sutton V, Bakken R, Paczkowski M, Kelsey D, Sumner C. Atomoxetine treatment of pediatric patients with attention-deficit / hyperactivity disorder with comorbid anxiety disorder. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2005;44:1119–1127. doi: 10.1097/chi.0b013e3180ca8385. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kratochvil CJ, Newcorn JH, Arnold LE, Duesenberg D, Emslie GJ, Quintana H, Sarkis EH, Wagner KD, Gao H, Michelson D, Biederman J. Atomoxetine alone or combined with fluoxetine for treating ADHD with comorbid depressive or anxiety symptoms. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2005;44:915–924. doi: 10.1097/01.chi.0000169012.81536.38. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li S, Lawler JE, Randall DC, Brown DR. Sympathetic nervous activity and arterial pressure responses during rest and acute behavioral stress in SHR vs. WKY rats. J. Autonom. Nerv. Sys. 1997;62:147–154. doi: 10.1016/s0165-1838(96)00119-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li S-G, Randall DC, Brown DR. Roles of cardiac output and peripheral resistance in mediating blood pressure response to stress in rats. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol. 1998;274:R1065–R1069. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.1998.274.4.R1065. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li WY, Silcox DL, Brown DR, Randall DC. Effects of CNS norepinephrine reuptake inhibition upon the arterial blood pressure conditional response in rat. FASEB J. 2006;20:A367. [Google Scholar]

- Michelson D, Adler L, Spencer T, Reimherrr FW, West SA, Allen AJ, Kelsey D, Wernicke J, Dietrich A, Milton Denái. Atomoxetine in adults with ADHD: two randomized placebo-controlled studies. Biol. Psychiatry. 2003;53:112–120. doi: 10.1016/s0006-3223(02)01671-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moran-Gates T, Zhang K, Baldessarini RJ, Tarazi FI. Atomoxetine blocks motor hyperactivity in neonatal 6-hydorxydopamine-lesioned rats: implications for treatment of attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder. Int J Neuropsychopharmacol. 2005;8:439–444. doi: 10.1017/S1461145705005249. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paré WP. Passive-avoidance behavior in Wistar-Kyoto (WKY), Wistar and Fischer-344 rats. Physiol Behav. 1993;54:845–852. doi: 10.1016/0031-9384(93)90291-m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Randall DC, Brown DR, Brown LV, Kilgore JM, Behnke MM, Moore SK, Powell KR. Two-component arterial blood pressure conditional response in rat. Integrative Physiol. Behav. Sci. 1993;28:258–269. doi: 10.1007/BF02691243. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Randall DC, Brown DR, Brown LV, Kilgore JM. Sympathetic nervous activity and arterial blood pressure control in conscious rat during rest and behavioral stress. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol. 1994;267:R1241–R1249. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.1994.267.5.R1241. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simpson D, Plosker GL. Atomoxetine: a review of its use in adults with attention deficit hyperactivity disorder. Drugs. 2004;64:205–222. doi: 10.2165/00003495-200464020-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wernicke JF, Faries D, Girod D, Brown JW, Gao H, Kelsey D, Quintana H, Lipetz R, Michelson D, Heiligenstein J. Cardiovascular effects of atomoxetine in children, adolescents, and adults. Drug Safety. 2003;26:729–740. doi: 10.2165/00002018-200326100-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]