Abstract

Objective:

Periosteum is involved in bone growth and fracture healing and has been used as a cell source and tissue graft for tissue engineering and orthopedic reconstruction including joint resurfacing. Periosteum can be induced by transforming growth factor beta (TGF-β) or insulin-like growth factor-I (IGF-I) alone or in combination to form cartilage. However, little is known about the interaction between IGF and TGF-β signaling during periosteal chondrogenesis. The purpose of this study was to determine the effect of TGF-β1 on IGF binding protein-4 (IGFBP-4) and the IGFBP-4 protease pregnancy-associated plasma protein-A (PAPP-A) expression in cultured periosteal explants.

Design:

Periosteal explants from rabbits were cultured with or without TGF-β1. IGFBP-4 and PAPP-A mRNA levels were determined by real-time quantitative PCR. Conditioned medium was analyzed for IGFBP-4 and PAPP-A protein levels and IGFBP-4 protease activity.

Results:

TGF-β1-treated explants contained lower IGFBP-4 mRNA levels throughout the culture period with a maximum reduction of 70 % on day 5 of culture. Lower levels of IGFBP-4 protein were also detected in the conditioned medium from TGF-β1-treated explants. PAPP-A mRNA levels were increased 1.6 fold, PAPP-A protein levels were increased 3 fold, and IGFBP-4 protease activity was increased 8.5 fold between 7 and 10 days of culture (the onset of cartilage formation in this model) in conditioned medium from TGF-β1-treated explants.

Conclusions:

This study demonstrates that TGF-β1 modulates the expression of IGFBP-4 and PAPP-A in cultured periosteal explants.

Keywords: Cartilage, Chondrocyte, Insulin Like Growth Factor I, Periosteum, Transforming Growth Factor Beta, insulin-like growth factor binding protein-4, pregnancy-associated plasma protein-A

1. INTRODUCTION

Periosteum, the connective tissue that surrounds bones, is a versatile tissue that can be used as a whole tissue graft or a cell source for tissue engineering or regeneration of bone and cartilage1-14. The regenerative capacity of periosteum is due to the presence of mesenchymal stem cells capable of differentiating into chondrocytes, osteoblasts, adipocytes, and skeletal myocytes15. This unique tissue contains two discrete layers: the inner cambium, which contains the mesenchymal stem cells, and an outer fibrous layer16, 17. As a whole tissue graft, periosteum can be used to resurface a joint without the need for in vitro culture. One obstacle regarding the use of periosteum, however, is the decrease in the number of mesenchymal stem cells in the cambium that occurs with age18. Using an in vitro periosteal organ culture model, we have demonstrated that periosteal cell proliferation and chondrogenesis can be induced by exogenous treatment with TGF-β1 or IGF-I alone or in combination9, 19-22. Recently we also demonstrated that local injection of TGF-β1 alone or in combination with IGF-I can be used to rejuvenate aged periosteum for the purpose of cartilage regeneration23. However, in order to further exploit the potential benefits of TGF-β1 and IGF-I in cartilage regeneration we need to better understand the interactions between these signaling systems in periosteum.

Previous studies suggest that TGF-β can regulate the bioavailability of IGF-I in chondrocytes and osteoblasts through modulation of IGFBP levels24-28. IGFBP-4, which is expressed in cartilage and bone, is a negative regulator of local IGF action29-31. In bone, IGFBP-4 binds and sequesters IGF-I from its receptors, thereby inhibiting osteoblast proliferation32, 33. IGFBP-4 bioavailability is determined by gene expression and proteolysis31, 34, 35. PAPP-A is an IGF-dependent-IGFBP-4 protease expressed by human fibroblasts and osteoblasts in culture36. Cleavage of IGFBP-4 at Met135-Lys136 reduces its binding affinity for IGF allowing for greater receptor stimulation and subsequent growth response in cultured cells 34, 35, 37, 38. Ortiz et al. demonstrated that TGF-β regulates IGFBP-4 and increases the expression of the IGFBP-4 protease PAPP-A in cultured osteoblasts27. We hypothesized that TGF-β regulates IGF-I bioavailability in periosteum by modulating the expression of IGFBP-4 and its protease PAPP-A. Thus, the objective of this study was to determine the effect of TGF-β1 treatment on IGFBP-4 and PAPP-A expression and IGFBP-4 proteolysis in cultured periosteal explants.

2. MATERIALS AND METHODS

2.1. Periosteal explant harvest and culture

For the gene expression experiments, 352 explants (2 × 3 mm2) were harvested from the medial proximal tibiae of 44 two-month old New Zealand white rabbits using sharp elevation. The explants were cultured in a 0.5 % agarose suspension in Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium (DMEM) (GIBCO, Grand Island, N.Y.) with 1 mM L-proline (Sigma, St. Louis, MO), 50 μg/mL L-ascorbic acid (BDH Chemicals, Toronto, Canada), penicillin-streptomycin (Sigma, St. Louis, MO) (10% fetal bovine serum (FBS) with or without 10 ng/mL TGF-β1 (R&D Systems, Minneapolis, MN) during the first two days of culture as previously described9. The periosteal explants were cultured for 3 to 42 days. At harvest, explants were washed in phosphate buffered saline (PBS) and pooled (2 explants/group) flash frozen in liquid nitrogen and stored at −70°C until RNA isolation.

For conditioned media experiments, 184 explants were cultured as described above for 7 days. After 7 days, the serum containing medium was removed and replaced with serum-free DMEM containing 0.1% BSA for 48, 72, or 96 h. The conditioned medium was collected and centrifuged at 2000 g at 4°C for 15 minutes and stored at −70°C.

2.2. RNA isolation and cDNA synthesis

Cultured periosteal explants were pulverized in liquid nitrogen, homogenized using a QIA shredder (Qiagen, Inc., Valencia, CA, USA), incubated for 20 min. at 55°C in 20 mg/mL with proteinase K (Qiagen, Inc., Valencia, CA, USA) and extracted using the Rneasy Mini Kit (Qiagen, Inc., Valencia, CA, USA) including the “on-column” DNase digestion protocol. A second “off-column” Dnase treatment using RQ1 Rnase-Free Dnase (Promega, Madison, WI, USA) followed by re-purification with the Rneasy Mini Kit was used to eliminate residual genomic DNA contamination. The total RNA yield from two cultured periosteal explants ranged from 1 to 3 μg. Approximately 500 ng of total RNA was reverse transcribed with random hexamer primers at 37°C for 60 min.

2.3. Quantitative real-time PCR

Quantitative real-time PCR was performed using the ABI PRISM 7700 Sequence Detection System and software (PE Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA). Rabbit specific cDNA sequences were obtained using a gene digging technique previously described39. These rabbit sequences were used to generate primer and probe sequences using the Primer Express™ (PE Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA) software (Table 1). Standard curves were generated from synthetic oligonucleotides of the experimental amplicons to obtain copy number data. All samples (n=6) were run in duplicate and quantitated by normalizing the target signal with the GAPDH signal.

Table 1.

Primers, probes and amplicons used in the real-time PCR analyses.

| Gene | Primers | Probe | Amplicon |

|---|---|---|---|

| IGFBP-4 |

Forward: GCACCCACGAGGACCTCTT Reverse: GGGCTGGGTGACACTGCTT |

6FAM- CGACCGCAACGGCAACTTCCAC- MGBNFQ |

GCACCCACGAGGACCTCTTC ATCATCCCCATCCCCAACTGC GACCGCAACGGCAACTTCCAC CCCAAGCAGTGTCACCCAGCCCTG |

| PAPP-A |

Forward: GACTTGCTTTGATCCCGACTCT Reverse: ATGTGTTGATCCATCCAATTTCAG |

6FAM- CTCACAGAGCTTATCTG-MGBNFQ |

GACTTGCTTTGATCCCGACTCT CCTCACAGAGCTTATCTGGATG TTAATGAGCTGAAGAACATTCTG AAATTGGATGGATCAACACAT |

| Aggrecan |

Forward: CTGCTACGGAGACAAGGATGAGT Reverse: CTGCGAAGCAGTACACGTCATAG |

6FAM- CCCTGGCGTGAGAACCTACGGCA- MGBNFQ |

CTGCTACGGAGACAAGGATGAGTT CCCTGGCGTGAGAACCTACGGCAT CCGGGACACCAACGAGA CCTATGACGTGTACTGCTTCGCAG |

| GAPDH |

Forward: GAGACACGATGGTGAAGGTCG Reverse: CTGGTGACCAGGCGCC |

6FAM- CCAATGCGGCCAAATCCGTTCA- MGBNFQ |

GAGACACGATGGTGAAGGTCG GAGTGAACGGATTTGGCCGCA TTGGGCGCCTGGTCACCAG |

2.4. PAPP-A protein levels

PAPP-A protein levels in periosteal conditioned medium samples were measured using an Ultra-sensitive PAPP-A ELISA kindly provided by Diagnostic Systems Laboratories, Inc. (Webster, TX). The minimum sensitivity of the PAPP-A ELISA is 0.24 mIU/L with intra- and inter-assay coefficients of variation of 4.7% and 4.2% respectively.

2.5. IGFBP-4 protease activity

Fifty microliters of periosteal explant conditioned medium were incubated in a microcentrifuge tube containing 125I-IGFBP-4 with or without 5 nM IGF-II at 37 °C for 24 hr, as previously described 36, 37. The IGF-II is added as a cofactor to the cell-free reaction because IGFBP-4 protease activity is dependent on IGF-II binding to IGFBP-440. Reaction products from three different samples for control and TGF-β groups were separated by SDS-PAGE, 7.5-15% gradient and visualized by autoradiography.

2.6. Western ligand blot

Fifty microliters of 48 and 72 h condioned medium samples were separated by SDS-PAGE using a 7.5-15% linear gradient. Separated proteins were blotted onto nitrocellulose filters, blocked, labeled with 125I-IGF-I overnight at 4°C, visualized by autoradiography37, 41, 42 and quantitated using NIH Image™ analysis software.

2.7. Statistical analysis

Quantitative real-time PCR data were analyzed using a 1 or 2-factor ANOVA to determine the effect of time and/or TGF-β1 dosage on the measured mRNA levels. Where appropriate, post-hoc testing using Duncan's Multiple Range test was performed to determine significance (p < 0.05) between specific time points for a given TGF-β1 dosage (i.e. 0 or 10 ng/mL). Significance between TGF-β1 dosage groups for specific time points were determined using means contrast comparisons. PAPP-A protein levels (ELISA) and activity (protease assay) results were analyzed using student t-tests.

3. RESULTS

3.1. IGFBP-4 and PAPP-A mRNA

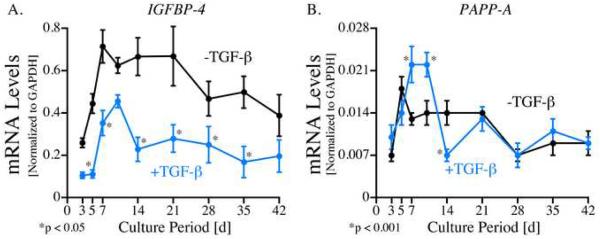

Periosteal explants were cultured for up to 42 days with or without 10 ng/mL TGF-β1 (for the first 48h) and gene expression was analyzed using Real Time PCR with rabbit-specific primers and probes for IGFBP-4, PAPP-A and GAPDH. As shown in Figure 1A, IGFBP-4 mRNA was detected in all periosteal explants. IGFBP-4 mRNA levels increased during the first week of culture in both the TGF-β1-treated and control explants followed by a decrease after peaks on days 10 and 7 respectively. The relative levels of IGFBP-4 mRNA were significantly reduced (p<0.05) in the TGF-β1-treated explants at all time points except day 42. The greatest effect of TGF-β1 was observed on day 5 where IGFBP-4 mRNA levels were 70 % lower (TGF-β1: 0.35 ± .15 vs. control: 0.71 ± 0.19 copies IGFBP-4/copies GAPDH) in the TGF-β1-treated group compared to controls.

Fig. 1.

A) IGFBP-4 and B) PAPP-A mRNA levels in cultured periosteal explants (12 explants/group). Periosteal explants were cultured for up to 42 days with (blue line) or without (black line) 10 ng/mL TGF-β1 (for the first two days). RNA was extracted from the explants (pooled 2 explants/group) after 3, 5, 7, 10, 14, 21, 28, 35 and 42 days of culture, reverse transcribed and analyzed using Real Time PCR with rabbit-specific primers and probes for IGFBP-4, PAPP-A and GAPDH. Standard curves from specific oligonucleotides containing primers and probe sequences were generated to obtain copy number data. All samples (n=6) were run in duplicate and quantitated by normalizing the target signal with the GAPDH signal. The data are presented as means ± standard error. Post-hoc testing using Duncan's Multiple Range test was performed to determine significance between specific times ± TGF-β1.

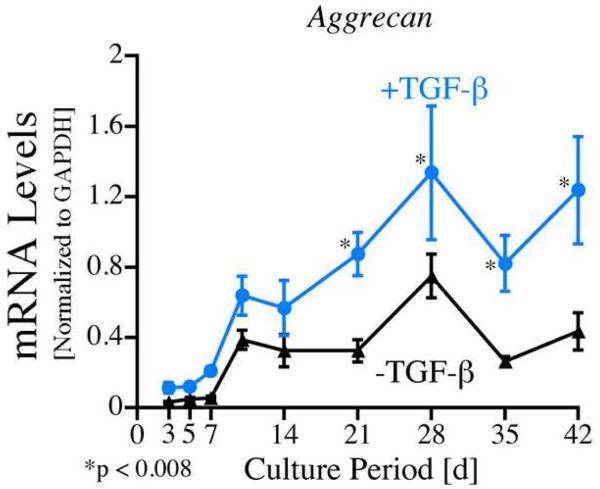

As shown in Figure 1B, PAPP-A mRNA was also detected in periosteal explants throughout the culture period. PAPP-A mRNA levels also increased early during the culture period with peak levels on day 5 in the control group and on days 7 and 10 in the TGF-β1 treated explants. TGF-β1 treated explants also contained 1.7 and 1.6 fold higher levels of PAPP-A mRNA on days 7 and 10 respectively (p<0.001) and 50 % lower levels on day 14 (p<0.001). In order to verify that the explants used in this experiment responded in the expected chondrogenic manner to TGF-β1 treatment, aggrecan mRNA levels were analyzed in the same pool of periosteal explants. As seen in Figure 4, relative aggrecan mRNA levels were significantly increased in the TGF-β1 treated explants compared to controls on days 21-42 of culture (p<0.008).

Fig. 4.

Aggrecan mRNA levels in cultured periosteal explants (12 explants/group). Periosteal explants were cultured for up to 42 days with (blue line) or without (black line) 10 ng/mL TGF-β1 (for the first two days). RNA was extracted from the explants (pooled 2 explants/group) after 3, 5, 7, 10, 14, 21, 28, 35 and 42 days of culture, reverse transcribed and analyzed using Real Time PCR with rabbit-specific primers and probes for aggrecan and GAPDH. Standard curves from specific oligonucleotides containing primer and probe sequences were generated to obtain copy number data. All samples (n=6) were run in duplicate and quantitated by normalizing the target signal with the GAPDH signal. The data are presented as means ± standard error. Post-hoc testing using Duncan's Multiple Range test was performed to determine significance between specific times ± TGF-β1.

3.2. IGFBP-4 and PAPP-A protein levels

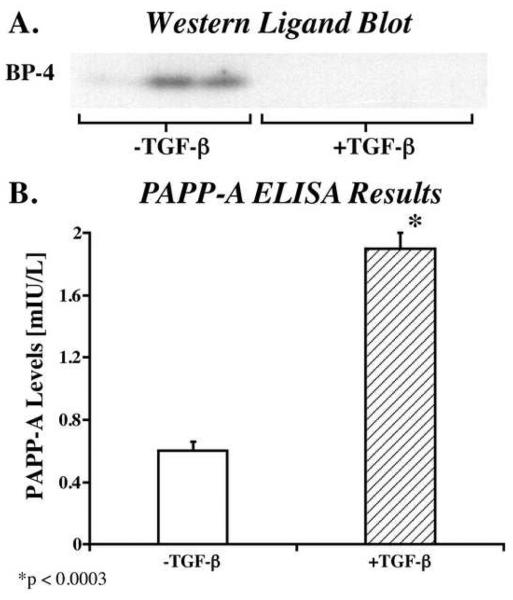

In order to measure IGFBP-4 protein levels, periosteal explants were cultured in serum containing medium until day 7 (with or without 10 ng/mL TGF-β1 for the first 48h). The medium was then changed to serum free medium and conditioned medium was collected 48h later. The conditioned medium was then analyzed by Western ligand blot. As shown in Figure 2A, conditioned medium from control explants contained detectable amounts of intact IGFBP-4 (24 kDa) whereas no IGFBP-4 was detectable in the conditioned medium from TGF-β1-treated explants. A second aliquot of conditioned medium was harvested 24h after the initial sample and similar results were observed in these samples (data not shown).

Fig. 2.

A) Western ligand blot analysis of IGFBP-4 in conditioned medium from cultured periosteal explants. Periosteal explants were cultured in serum containing medium until day 7 (with or without 10 ng/mL TGF-β1 for the first 48h). The medium was then changed to serum free medium and conditioned medium was collected 48h later. The conditioned medium was then analyzed by Western ligand blot. B) PAPP-A secretion from cultured periosteal explants. Periosteal explants were cultured in serum containing medium until day 7 (with or without 10 ng/mL TGF-β1 for the first 48h). The medium was then changed to serum free medium and conditioned medium was collected 96h later. The conditioned medium was then analyzed by ELISA. The data are presented as means ± standard deviation. Two-tailed students t-test was used to determine significance.

The levels of PAPP-A protein between days 7 and 10 of culture were also determined in periosteal conditioned medium by ELISA. Periosteal explants were again cultured in serum containing medium until day 7 (with or without 10 ng/mL TGF-β1 for the first 48h). The medium was then changed to serum free medium and conditioned medium was collected 96h later. As shown in Figure 2B, conditioned medium from TGF-β1 treated explants contained 3 fold more PAPP-A protein (p<0.0003) than conditioned medium from control explants.

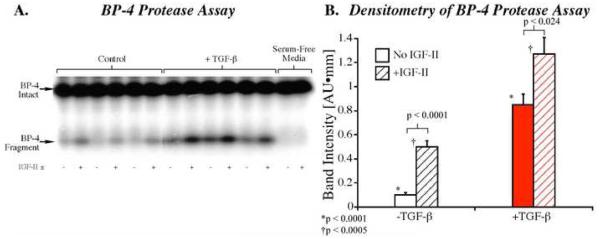

3.3. IGBP-4 proteolysis

IGFBP-4 proteolysis in conditioned medium from cultured periosteal explants was also determined (based on IGFBP-4 fragment production). In this experiment, aliquots of the same conditioned medium used in the PAPP-A ELISA were analyzed using the IGFBP-4 protease assay as described in the Methods. As shown in Figure 3, addition of 5 nM IGF-II significantly increased IGFBP-4 protease activity in both the control (p<0.0001) and TGF-β1 treated (p<0.024) samples. In addition, TGF-β1 treatment enhanced IGFBP-4 protease activity 8.5 fold in the control (p<0.0001) and 2.5 fold in the IGF-II treated (p<0.0005) samples compared to the respective controls.

Fig. 3.

IGFBP-4 proteolysis in conditioned medium from cultured periosteal explants. Periosteal explants were cultured in serum containing medium until day 7 (with or without 10 ng/mL TGF-β1 for the first 48h). The medium was then changed to serum free medium and conditioned medium was collected 96h later. Fifty microliters of periosteal explant conditioned medium were incubated in a microcentrifuge tube containing 125I-IGFBP-4 with or without 5 nM IGF-II at 37 °C for 24 hr, as previously described 36, 37. A) Reaction products from three different samples for control and TGF-β groups were separated by SDS-PAGE, 7.5-15% gradient and visualized by autoradiography. B) Densitometry analysis of the IGFBP-4 fragment bands. The results are presented as means ± standard error. Two-tailed students t-test was used to determine significance.

4. DISCUSSION

In this study we demonstrate that TGF-β1 modulates IGFBP-4 and PAPP-A expression in cultured periosteal explants. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first study to demonstrate the expression of PAPP-A and its regulation during the process of chondrogenesis. Because IGF-I is an important chondrogenic growth factor, regulation of IGF-I bioavailability may be an essential aspect of TGF-β1 action on periosteum. In these experiments a decrease in IGFBP-4 mRNA levels was observed throughout the six week culture after treatment with 10 ng/mL TGF-β1. In TGF-β1 treated periosteal explants, mRNA levels of the IGBP-4 protease, PAPP-A, were also elevated on days 7 and 10 of culture compared to untreated explants. These results were confirmed by protein analysis, as a 3-fold increase in PAPP-A protein was detected in conditioned medium from TGF-β1 treated explants compared to controls. Furthermore, the secreted PAPP-A protein was functional as evident by a significant increase in IGFBP-4 proteolysis in CM from TGF-β1 treated explants. Together these data demonstrate that TGF-β1 increased the level of functional PAPP-A protein between 7 and 11 days of culture. This observation is of particular interest because it occurs during the transition from the proliferation to differentiation stage in this in vitro periosteal chondrogenesis model5. At this time cartilage formation is initiated as chondrocyte precursors begin to differentiate into mature chondrocytes that are capable of matrix synthesis7. Therefore, because IGFBP-4 plays a fundamental role in regulating IGF-I bioavailability, alterations in PAPP-A activity during this period may have a functional role in TGF-β1 induced periosteal chondrogenesis.

The results from the present study are similar to previously reported findings in cultured human osteoblasts27, 43. In these studies, TGF-β treatment also increases PAPP-A expression and IGFBP-4 proteolysis27, 43. In addition, recent studies revealed that fracture healing was delayed, and cartilage formation in the fracture callus was reduced in PAPP-A knock-out mice compared to wild-type mice44. These findings suggest that PAPP-A is needed for optimal cartilage formation from periosteum and support a potential role for PAPP-A in the chondrogenic response of cultured periosteal explants to TGF-β1.

Interestingly, alterations in the IGF-I axis have been reported in synovial fluid from arthritic joints and in osteoarthritic cartilage45-47. Osteoarthritc chondrocytes have been shown to be hyporesponsive to IGF-I despite having increased binding sites48. The response of chondrocytes to IGF-I also decreases with age, and this may be due to increased levels of IGFBPs46, 49. Therefore, IGFBP degradation pathways may be suitable targets for articular cartilage repair especially in patients with elevated synovial IGFBP levels as in older patients or those with RA or OA. Therefore, if even short-term TGF-β1 treatment can produce a sustained inhibition of IGFBP production during cartilage repair, this may provide additional benefit to the initial quality and homeostasis of the repair tissue.

In summary, these studies demonstrate that short-term TGF-β1 treatment of cultured periosteal explants results in modulation of the IGF-I axis, including some sustained affects. These findings are likely to be relevant to the use of periosteal grafts or periosteal cells for the regeneration of musculoskeletal tissues such as articular cartilage especially if short-term TGF-β1 and/or IGF treatment is used to augment growth and cartilage formation23.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This study was funded by NIH grant AR43890 and the Mayo Clinic Rochester, Minnesota. Salary support for Dr. Gonzalez was provided by a scholarship from the Mayo Medical School for Graduate Studies. Salary support for Dr. Auw Yang was provided by a fellowship from the University of Utrecht, The Netherlands. The Mayo Medical School Graduate Studies Orthopedics Master's Program provided salary support for Dr. Schwab.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

REFERENCES

- 1.O'Driscoll SW, Salter RB. The induction of neochondrogenesis in free intra-articular periosteal autografts under the influence of continuous passive motion. An experimental investigation in the rabbit. J Bone Joint Surg. 1984;66A:1248–1257. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.O'Driscoll SW, Keeley FW, Salter RB. Durability of regenerated articular cartilage produced by free autogenous periosteal grafts in major full-thickness defects in joint surfaces under the influence of continuous passive motion. A follow-up report at one year. J Bone Joint Surg. 1988;70A:595–606. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.O'Driscoll SW, Salter RB. The repair of major osteochondral defects in joint surfaces by neochondrogenesis using autogenous osteoperiosteal grafts stimulated by continuous passive motion. An experimental investigation in the rabbit. Clin Orthop. 1986;208:131–140. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.O'Driscoll SW, Keeley FW, Salter RB. The chondrogenic potential of free autogenous periosteal grafts for biological resurfacing of major full-thickness defects in joint surfaces under the influence of continuous passive motion. An experimental investigation in the rabbit. J Bone Joint Surg. 1986;68A:1017–1035. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.O'Driscoll SW. Articular cartilage regeneration using periosteum. Clin Orthop. 1999;367(Suppl):186–203. doi: 10.1097/00003086-199910001-00020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Nakahara H, Bruder SP, Haynesworth SE, Holecek JJ, Baber MA, Goldberg VM, et al. Bone and cartilage formation in diffusion chambers by subcultured cells derived from the periosteum. Bone. 1990;11:181–188. doi: 10.1016/8756-3282(90)90212-h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.O'Driscoll SW, Fitzsimmons JS. The role of periosteum in cartilage repair. Clin Orthop. 2001:S190–207. doi: 10.1097/00003086-200110001-00019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Nakahara H, Goldberg VM, Caplan AI. Culture-expanded human periosteal-derived cells exhibit osteochondral potential in vivo. J Orthop Res. 1991;9:465–476. doi: 10.1002/jor.1100090402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.O'Driscoll SW, Recklies AD, Poole AR. Chondrogenesis in periosteal explants. An organ culture model for in vitro study. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1994;76:1042–1051. doi: 10.2106/00004623-199407000-00013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hutmacher DW, Sittinger M. Periosteal cells in bone tissue engineering. Tissue Eng. 2003;9(Suppl 1):S45–64. doi: 10.1089/10763270360696978. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Stevens MM, Marini RP, Schaefer D, Aronson J, Langer R, Shastri VP. In vivo engineering of organs: the bone bioreactor. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2005;102:11450–11455. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0504705102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.O'Driscoll SW, Salter RB. The repair of major osteochondral defects in joint surfaces by neochondrogenesis with autogenous osteoperiosteal grafts stimulated by continuous passive motion. An experimental investigation in the rabbit. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1986:131–140. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Mardones RM, Reinholz GG, Fitzsimmons JS, Zobitz ME, An KN, Lewallen DG, et al. Development of a biologic prosthetic composite for cartilage repair. Tissue Eng. 2005;11:1368–1378. doi: 10.1089/ten.2005.11.1368. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Knothe UR, Springfield DS. A novel surgical procedure for bridging of massive bone defects. World J Surg Oncol. 2005;3:7. doi: 10.1186/1477-7819-3-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.De Bari C, Pitzalis C, Dell'Accio F. Reparative medicine: from tissue engineering to joint surface regeneration. Regen Med. 2006;1:59–69. doi: 10.2217/17460751.1.1.59. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Tonna EA. An autoradiographic evaluation of the aging cellular phase of mouse skeleton using tritiated glycine. J Gerontal. 1964;19 doi: 10.1093/geronj/19.2.198. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ito Y, Fitzsimmons JS, Sanyal A, Mello MA, Mukherjee N, O'Driscoll SW. Localization of chondrocyte precursors in periosteum. Osteoarthritis Cartilage. 2001;9:215–223. doi: 10.1053/joca.2000.0378. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.O'Driscoll SW, Saris DBF, Ito Y, Fitzsimmons JS. The chondrogenic potential of periosteum decreases with age. J Orthop Res. 2001;19:95–103. doi: 10.1016/S0736-0266(00)00014-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Miura Y, Fitzsimmons JS, Commisso CN, Gallay SH, O'Driscoll SW. Enhancement of periosteal chondrogenesis in vitro: Dose-response for transforming growth factor-beta 1 (TGF-ß1) Clin Orthop. 1994;301:271–280. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Fukumoto T, Sperling JW, Sanyal A, Fitzsimmons JS, Reinholz GG, Conover CA, et al. Combined effects of insulin-like growth factor-1 and transforming growth factor-beta1 on periosteal mesenchymal cells during chondrogenesis in vitro. Osteoarthritis Cartilage. 2003;11:55–64. doi: 10.1053/joca.2002.0869. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Fitzsimmons JS, Sanyal A, Gonzalez C, Fukumoto T, Clemens VR, O'Driscoll S W, et al. Serum-Free Media For Periosteal Chondrogenesis In Vitro. J Orthop Res. 2004;22:716–725. doi: 10.1016/j.orthres.2003.10.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Davis CM, III, Miura Y, Sarkar G, Bolander ME, Fitzsimmons JS, O'Driscoll SW. Expression of cartilage-specific genes during neochondrogenesis in periosteal explants. Biomed Res. 2000;21:9–15. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Reinholz GG, Fitzsimmons JS, Casper ME, Ruesink TJ, Chung HW, Schagemann JC, et al. Rejuvenation of periosteal chondrogenesis using local growth factor injection. Osteoarthritis Cartilage. 2009;17:723–734. doi: 10.1016/j.joca.2008.10.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Morales TI. The role and content of endogenous insulin-like growth factor-binding proteins in bovine articular cartilage. Arch Biochem Biophys. 1997;343:164–172. doi: 10.1006/abbi.1997.0166. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.De Los Rios P, Hill DJ. Expression and release of insulin-like growth factor binding proteins in isolated epiphyseal growth plate chondrocytes from the ovine fetus. J Cell Physiol. 2000;183:172–181. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-4652(200005)183:2<172::AID-JCP4>3.0.CO;2-S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Tsukazaki T, Usa T, Matsumoto T, Enomoto H, Ohtsuru A, Namba H, et al. Effect of transforming growth factor-beta on the insulin-like growth factor-I autocrine/paracrine axis in cultured rat articular chondrocytes. Exp Cell Res. 1994;215:9–16. doi: 10.1006/excr.1994.1307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ortiz CO, Chen BK, Bale LK, Overgaard MT, Oxvig C, Conover CA. Transforming growth factor-beta regulation of the insulin-like growth factor binding protein-4 protease system in cultured human osteoblasts. J Bone Miner Res. 2003;18:1066–1072. doi: 10.1359/jbmr.2003.18.6.1066. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Shimasaki S, Ling N. Identification and molecular characterization of insulin-like growth factor binding proteins (IGFBP-1, -2, -3, -4, -5 and -6) Prog Growth Factor Res. 1991;3:243–266. doi: 10.1016/0955-2235(91)90003-m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Olney RC, Tsuchiya K, Wilson DM, Mohtai M, Maloney WJ, Schurman DJ, et al. Chondrocytes from osteoarthritic cartilage have increased expression of insulin-like growth factor I (IGF-I) and IGF-binding protein-3 (IGFBP-3) and -5, but not IGF-II or IGFBP-4. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 1996;81:1096–1103. doi: 10.1210/jcem.81.3.8772582. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Mohan S, Bautista CM, Wergedal J, Baylink DJ. Isolation of an inhibitory insulin-like growth factor (IGF) binding protein from bone cell-conditioned medium: a potential local regulator of IGF action. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1989;86:8338–8342. doi: 10.1073/pnas.86.21.8338. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Mohan S, Nakao Y, Honda Y, Landale E, Leser U, Dony C, et al. Studies on the mechanisms by which insulin-like growth factor (IGF) binding protein-4 (IGFBP-4) and IGFBP-5 modulate IGF actions in bone cells. J Biol Chem. 1995;270:20424–20431. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.35.20424. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Durham SK, De Leon DD, Okazaki R, Riggs BL, Conover CA. Regulation of insulin-like growth factor (IGF)-binding protein-4 availability in normal human osteoblast-like cells: role of endogenous IGFs. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 1995;80:104–110. doi: 10.1210/jcem.80.1.7530254. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Qin X, Byun D, Strong DD, Baylink DJ, Mohan S. Studies on the role of human insulin-like growth factor-II (IGF-II)-dependent IGF binding protein (hIGFBP)-4 protease in human osteoblasts using protease-resistant IGFBP-4 analogs. J Bone Miner Res. 1999;14:2079–2088. doi: 10.1359/jbmr.1999.14.12.2079. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Durham SK, Kiefer MC, Riggs BL, Conover CA. Regulation of insulin-like growth factor binding protein 4 by a specific insulin-like growth factor binding protein 4 proteinase in normal human osteoblast-like cells: implications in bone cell physiology. J Bone Miner Res. 1994;9:111–117. doi: 10.1002/jbmr.5650090115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kanzaki S, Hilliker S, Baylink DJ, Mohan S. Evidence that human bone cells in culture produce insulin-like growth factor-binding protein-4 and -5 proteases. Endocrinology. 1994;134:383–392. doi: 10.1210/endo.134.1.7506211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Lawrence JB, Oxvig C, Overgaard MT, Sottrup-Jensen L, Gleich GJ, Hays LG, et al. The insulin-like growth factor (IGF)-dependent IGF binding protein-4 protease secreted by human fibroblasts is pregnancy-associated plasma protein-A. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1999;96:3149–3153. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.6.3149. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Conover CA, Kiefer MC, Zapf J. Posttranslational regulation of insulin-like growth factor binding protein-4 in normal and transformed human fibroblasts. Insulin-like growth factor dependence and biological studies. J Clin Invest. 1993;91:1129–1137. doi: 10.1172/JCI116272. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Conover CA, Durham SK, Zapf J, Masiarz FR, Kiefer MC. Cleavage analysis of insulin-like growth factor (IGF)-dependent IGF- binding protein-4 proteolysis and expression of protease-resistant IGF- binding protein-4 mutants. J Biol Chem. 1995;270:4395–4400. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.9.4395. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Sanyal A, O'Driscoll SW, Fitzsimmons JS, Bolander ME, Sarkar G. Gene digging. A method for obtaining species-specific sequence based on conserved segments of nucleotides in open reading frames. Mol Biotechnol. 1998;10:223–230. doi: 10.1007/BF02740842. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Qin X, Byun D, Lau KH, Baylink DJ, Mohan S. Evidence that the interaction between insulin-like growth factor (IGF)-II and IGF binding protein (IGFBP)-4 is essential for the action of the IGF-II-dependent IGFBP-4 protease. Arch Biochem Biophys. 2000;379:209–216. doi: 10.1006/abbi.2000.1872. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Torring O, Firek AF, Heath H, 3rd, Conover CA. Parathyroid hormone and parathyroid hormone-related peptide stimulate insulin-like growth factor-binding protein secretion by rat osteoblast-like cells through a adenosine 3′,5′-monophosphate-dependent mechanism. Endocrinology. 1991;128:1006–1014. doi: 10.1210/endo-128-2-1006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Hossenlopp P, Seurin D, Segovia-Quinson B, Hardouin S, Binoux M. Analysis of serum insulin-like growth factor binding proteins using western blotting: use of the method for titration of the binding proteins and competitive binding studies. Anal Biochem. 1986;154:138–143. doi: 10.1016/0003-2697(86)90507-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Durham SK, Riggs BL, Conover CA. The insulin-like growth factor-binding protein-4 (IGFBP-4)-IGFBP-4 protease system in normal human osteoblast-like cells: regulation by transforming growth factor-beta. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 1994;79:1752–1758. doi: 10.1210/jcem.79.6.7527411. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Miller BS, Bronk JT, Nishiyama T, Yamagiwa H, Srivastava A, Bolander ME, et al. Pregnancy associated plasma protein-A is necessary for expeditious fracture healing in mice. J Endocrinol. 2007;192:505–513. doi: 10.1677/JOE-06-0011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Fernihough JK, Billingham ME, Cwyfan-Hughes S, Holly JM. Local disruption of the insulin-like growth factor system in the arthritic joint. Arthritis Rheum. 1996;39:1556–1565. doi: 10.1002/art.1780390916. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Martel-Pelletier J, Di Battista JA, Lajeunesse D, Pelletier JP. IGF/IGFBP axis in cartilage and bone in osteoarthritis pathogenesis. Inflamm Res. 1998;47:90–100. doi: 10.1007/s000110050288. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Iwanaga H, Matsumoto T, Enomoto H, Okano K, Hishikawa Y, Shindo H, et al. Enhanced expression of insulin-like growth factor-binding proteins in human osteoarthritic cartilage detected by immunohistochemistry and in situ hybridization. Osteoarthritis Cartilage. 2005;13:439–448. doi: 10.1016/j.joca.2004.12.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Dore S, Pelletier JP, DiBattista JA, Tardif G, Brazeau P, Martel-Pelletier J. Human osteoarthritic chondrocytes possess an increased number of insulin-like growth factor 1 binding sites but are unresponsive to its stimulation. Possible role of IGF-1-binding proteins. Arthritis & Rheumatism. 1994;37:253–263. doi: 10.1002/art.1780370215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Martin JA, Ellerbroek SM, Buckwalter JA. Age-related decline in chondrocyte response to insulin-like growth factor-I: the role of growth factor binding proteins. J Orthop Res. 1997;15:491–498. doi: 10.1002/jor.1100150403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]