Abstract

Background: A prospective phase II study was conducted to evaluate the efficacy and toxicity of oral gimatecan in patients with recurrent epithelial ovarian, fallopian tube or peritoneal cancer.

Patients and methods: Patients had a maximum of three prior chemotherapy lines with no more than two prior platinum-containing regimens and a progression-free interval after the last dose of platinum <12 months. A total dose of 4 mg/m2/cycle (0.8 mg/m2/day from day 1 to day 5) was administered, repeated every 28 days.

Results: From June 2005 to December 2005, 69 assessable patients were enrolled. The best overall response to study treatment by combined CA-125 and RECIST criteria was partial response in 17 patients (24.6%) and disease stabilization in 22 patients (31.9%). The median time to progression and overall survival were 3.8 and 16.2 months, respectively. A total of 312 cycles were administered. Neutropenia grade 4 and thrombocytopenia grade 4 occurred in 17.4% and 7.2% of patients, respectively. Diarrhea grade 4 was never observed. Asthenia and fatigue were reported by 36.2% and 18.8% of patients, but were all grade 2 or less.

Conclusion: Gimatecan is a new active agent in previously treated ovarian cancer with myelosuppression as main toxicity.

Keywords: camptothecin, gimatecan, ovarian cancer recurrence

introduction

Ovarian cancer is the fifth most frequent cause of cancer death in women and the leading cause of death from gynecologic malignancies. The fact that most patients are diagnosed with advanced-stage disease contributes to a poor 5-year survival of ∼30%.

Extensive surgical resection followed by platinum-based combination chemotherapy results in a high initial response rate, including complete clinically and radiologically confirmed responses. Even so, a distressingly high percentage of women with a complete response (CR) experience relapse. Although there are several active agents for the treatment of women with relapsed ovarian cancer, there is no predictably curative therapy for this stage of the disease. In the palliative phase of disease management, quality of life and the disease- and symptom-free period are of great importance, as well as the tolerability of the drugs used. One of the most important factors predictive of response to therapy for recurrent disease is the interval following last administration of platinum-based chemotherapy. Patients who relapse within 6 months are considered to have resistant disease and have a poorer prognosis, while patients relapsing later have more sensitive tumors and longer progression-free and overall survival [1].

Several nonplatinum agents have demonstrated activity in recurrent disease, such as the topoisomerase II inhibitor liposomal doxorubicin, the topoisomerase I inhibitor topotecan, the antimetabolite gemcitabine and trabectedin, a drug isolated from the marine organism Ecteinascidia turbinata. However, these drugs have a limited activity, with a response rate within a narrow range of 10%–30% [2–5].

Gimatecan (7-[(E)-tert-butyloxyminomethyl]-camptothecin) (ST1481) is a novel orally active compound belonging to the camptothecin (CPT) class. It is a potent topoisomerase I inhibitor, exerting a stronger and more persistent DNA cleavage than other members of the CPT family. Gimatecan was highly active in ovarian cancer models. In several experimental models, gimatecan showed activity in all schedules studied and a better therapeutic index than the reference CPTs [6].

Pharmacokinetic studies have shown that gimatecan is rapidly absorbed without a clear linear relationship between dose and systemic exposure; its half-life is very long, with a mean value of ∼90 h and, as a consequence, drug plasma accumulation was observed depending on frequency of dosing. The elimination of gimatecan is mediated by hepatic and extrahepatic cytochromes CYP3A4/5 and CYP1A1, respectively. Clinical outcome or side-effects of gimatecan did not correlate with any pharmacokinetic parameter (gimatecan investigator’s brochure, data on file).

A phase I study in patients with solid tumors has been completed [6]. Gimatecan was administered daily for 5 days for 1 week, 2 weeks or 3 weeks. Thrombocytopenia and neutropenia were the major dose-limiting toxic effects. The optimal dose for phase II testing was determined to be 4.0, 5.0 and 5.6 mg/m2 as total doses for the 1-, 2- and 3-week schedule, respectively. Six confirmed and peer-reviewed partial responses (PRs) were observed that lasted from 3.5 to 8.2 months: non-small-cell lung cancer (2), endometrial (2), cervical (1) and breast cancer (1). A decrease in CA-125 was observed in one of two patients with ovarian cancer treated with the 1-week schedule. On the basis of this, a phase II study of oral gimatecan in progressing or recurring patients with advanced epithelial ovarian, fallopian tube or peritoneal cancer, previously treated with platinum and taxanes, was initiated in Europe.

patients and methods

eligibility

Patients eligible for the study were those with histological diagnosis of epithelial ovarian, fallopian tube or peritoneal cancer; who had progressing or recurring disease; had measurable disease according to RECIST criteria and/or increase in CA-125 [7]; were previously treated with platinum and taxanes; had a maximum of three prior chemotherapy lines, with no more than two prior platinum-containing regimens, of which at least one containing taxanes; had a progression-free interval (PFI) after the last dose of platinum <12 months; aged ≥18 years; with an Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group (ECOG) performance status of zero or one and with an adequate bone marrow, hepatic and renal function. Moreover, all previous therapies for ovarian cancer had to be discontinued for ≥4 weeks before study entry and all acute toxic effects (excluding alopecia or peripheral neuropathy) of any prior therapy had to be recovered; life expectancy had to be ≥3 months and all patients needed to sign informed consent.

Approval to conduct the study was obtained from the ethical committee at each participating institution before the start of the trial.

The main reasons for not being eligible for the study were as follows: any investigational agent received ≤4 weeks before study entry and/or concurrent enrollment in another clinical trial; any prior topotecan or irinotecan treatment or any regimen containing an investigational inhibitor of topoisomerase I; previous major gastrointestinal surgery or diseases that could alter gastrointestinal absorption or motility (i.e. active peptic ulcer, inflammatory bowel disease, known intolerance to lactose and malabsorption syndromes); inability to swallow; any serious cardiac, infectious, neurological or psychiatric disorders; previous (past 5 years) or concomitant malignancy at another site; symptomatic brain metastases; previous treatment with mouse antibodies or previous medication and/or surgery that would interfere with peritoneum or pleura during the previous 28 days, in patients assessable by CA-125 only [8].

treatment plan and adjustments

Gimatecan was supplied by sigma-tau as oral gelatin capsules. It was administered orally at a total dose of 4 mg/m2/cycle (0.8 mg/m2/day from day 1 to day 5), repeated every 28 days. The administration was once daily, in the morning before breakfast. A 1-h post-administration interval was recommended before any food consumption. Patients were instructed to swallow each capsule (without chewing them) with water.

In case of hematological toxicity, growth factors were to be used as per the American Society of Clinical Oncology guidelines [9]. Medications known to be cytochrome P450 enzymes’ substrates/inducers like enzyme inducing anticonvulsant drugs and which have shown to increase the clearance of gimatecan were prohibited during the study. This includes phenytoin, carbamazepine, phenobarbital, primidone and oxcarbazepine.

The dose was reduced from 4.0 to 3.2 mg/m2/cycle on the basis of the worst hematological and non-hematological toxic effects in the previous cycle. A cycle could be delayed, depending on the type and severity of toxic effects that occurred during the previous cycle.

study assessments

To be assessable, each patient had to receive at least two treatment cycles, unless there was unacceptable toxicity, progressive disease (PD) or patients’ request for withdrawal.

Tumor response was the primary efficacy parameter. For patients with measurable disease, tumor response was assessed every two cycles according to RECIST criteria [10]. Response status was reviewed by a panel of independent experts. This assessment of the independent experts was the basis for the analysis. In patients without measurable disease, the evaluation of response to therapy was on the basis of changes in CA-125 as per the Gynecologic Cancer Intergroup criteria [8, 11]. A response was defined as a reduction from the pretreatment level of CA-125 of at least 50%, confirmed 4 weeks apart.

Secondary efficacy parameters were response duration, time to progression (TTP) and overall survival.

The qualitative and quantitative toxic effects were graded in agreement with National Cancer Institute—Common Toxicity Criteria version 2.0. This included all adverse events (AEs), whether volunteered by the patient, discovered by questioning or detected through physical examination, laboratory test or other means.

statistical methods and study design

The trial was carried out according to the Simon’s two-stage optimal design [12]. The assumptions were as follows: α = 0.05; β = 0.2 (power = 0.80); a level of the true rate of success that would cause an early refusal of the treatment at stage 1 equal to 5%; a level of the true rate of success that would cause the acceptance of the treatment in stage 2 equal to 15%. These assumptions required a sample size of 23 patients in the first stage and an additional 33 patients (i.e. 56 patients in total) in the second one.

After the study drug was tested on 23 assessable patients in the first stage, the trial was to be terminated if one or no patient responded. In the final analysis, if there were at least six responses of 56 assessable patients, it would be considered that the drug deserved further evaluation.

TTP was calculated from the first day of treatment to the date of the first documented tumor progression/recurrence or start of a new antitumor therapy or death; duration of response was defined as the time between the date of first documented response (i.e. overall response equal to CR or PR) to the first date of tumor progression/recurrence or start of a new antitumor treatment or death and applied only to responding patients; duration of stable disease (SD) was measured from the first day of treatment to the date of disease progression.

An information was censored in case of death unrelated to the tumor, if the last visit occurred in nonprogressing patients and in lost-to-follow-up nonprogressing patients.

Survival [time to death (TTD)] and its 95% confidence interval (CI) were assessed using Kaplan–Meier methods. Median survival time is presented.

TTD was obtained by computing (date of death − date of first treatment administration + 1). Patients alive or lost-to-follow-up are treated as right-censored information (censoring on last available visit date).

The intention-to-treat (ITT) population was defined as all registered patients who received at least one dose of study treatment. The efficacy evaluable (EE) population included all patients who received at least one dose of the investigational drug, were not major protocol violators, and had at least one on-study tumor assessment, besides baseline, or experienced early progression or toxicity.

Patients discontinued from the study that had no other tumor or CA-125 evaluation besides baseline assessment were classified as ‘PD’ if discontinued for early progression of the disease; as ‘Unknown’ (and therefore counted as nonresponders in the primary analysis) if discontinued for toxicity or were excluded if discontinued for a different reason than progression and/or toxicity (for example, withdrawal of consent).

Dose intensity was calculated as the weekly rate of therapy per cycle. The theoretical value was 1 mg/m2/week.

All statistical analyses were carried out using SAS®.

The statistical analysis was carried out by Debioclinic S.A. (Charenton le Pont, France).

results

patient characteristics

From 20 June 2005 to 21 December 2005, 72 patients were enrolled in 10 centers. Sixty-nine patients were assessable for efficacy and safety, while three patients did not receive treatment because two had a progression of disease (intestinal occlusion and brain metastases) precluding their inclusion into the trial and one withdrew her consent before therapy start.

Six patients had minor protocol violations and were included in the ITT/EE population.

Where appropriate, results are presented by PFI, calculated as the time elapsing from the last dose of platinum to the start of any subsequent therapy. The calculation of the interval was independent whether a nonplatinum regimen was given as last treatment before gimatecan started. Two PFI intervals were determined, <6 months or ≥6 months (up to 12 months as per protocol inclusion criteria), as it is generally accepted that patients with a PFI <6 months have a less favorable response rate to chemotherapy.

One patient had a PFI beyond 12 months (13.17 months) but due to allergy to carboplatinum could not be retreated with a platinum compound and was therefore included into the trial in the PFI ≥6 months group.

The baseline characteristics of the patients are presented in Table 1.

Table 1.

Patient baseline characteristics

| Statistics | PFI* |

Overall (N = 69) | ||

| <6 months (n = 50) | ≥6 months (n = 19) | |||

| Age (years) | Median | 59 | 65 | 62 |

| Minimum to maximum | 37 to 79 | 47 to 78 | 37 to 79 | |

| ECOG performance status | 0a, n (%) | 37 (74.0) | 13 (68.4) | 50 (72.5) |

| 1b, n (%) | 12 (24.0) | 6 (31.6) | 18 (26.1) | |

| NDc, n (%) | 1 (2.0) | 0 | 1 (1.4) | |

| PFI | Median (months) | 2.32 | 8.71 | 3.48 |

| Minimum to maximum | −0.07 to 5.98 | 6.08 to 13.17 | −0.07 to 13.17 | |

| Primary epithelial tumor type | ||||

| Ovarian | n (%) | 45 (90.0) | 16 (84.2) | 61 (88.4) |

| Peritoneal | n (%) | 5 (10.0) | 3 (15.8) | 8 (11.6) |

| Assessable by RECIST, n (%) | Yes | 40 (80.0) | 14 (73.7) | 54 (78.3) |

| No | 10 (20.0) | 5 (26.3) | 15 (21.7) | |

| Assessable by CA-125, n (%) | Yes | 41 (82.0) | 17 (89.5) | 58 (84.1) |

| No | 9 (18.0) | 2 (10.5) | 11 (15.9) | |

| Number of previous chemotherapy lines, n (%) | 1 | 9 (18.0) | 10 (52.6) | 19 (27.6) |

| 2 | 25 (50.0) | 8 (42.1) | 33 (47.8) | |

| 3 | 16 (32.0) | 1 (5.3) | 17 (24.6) | |

| Type of previous chemotherapy, n (%) | Platinum compounds | 50 (100) | 19 (100) | 69 (100) |

| Taxanes | 50 (100) | 19 (100) | 69 (100) | |

| Anthracyclines | 30 (60.0) | 3 (15.8) | 33 (47.8) | |

| Other | 14 (28.0) | 7 (36.8) | 21 (30.4) | |

PFI (after the last dose of platinum) calculated as time from the last dose of platinum to start of any subsequent therapy and independent whether a nonplatinum regimen was given as last treatment before gimatecan start.

a0: Able to carry out all normal activity without restriction.

b1: Restricted in physically strenuous activity but ambulatory and able to carry out light work.

cND: Not determined.

PFI, progression-free interval; ECOG, Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group.

All patients were Caucasians. There was a predominance of patients with resistant disease (72.5%), of whom 22% were refractory, having presented PD (8%) or SD (14%) during a prior platinum therapy. The main demographic characteristics were similar between the patients with PFI <6 months and those with PFI ≥6 months.

Most of the patients (72.4%) were pretreated with two or three prior therapy lines.

Bulky disease (tumor mass >5 cm) was present at baseline in 12 patients (11 with a PFI <6 months and 1 with a PFI ≥6 months).

extent of exposure

A total of 312 cycles was administered with a median of four cycles per patient (range 1–12). Eight patients stopped therapy after one cycle only, either because of PD (four patients) or AE/toxicity (four patients). Twenty-five patients (36.2%) were treated with six or more cycles of therapy; of these patients, 15 had as best response PR and 10 SD.

The achieved median dose intensity was 0.87 mg/m2/week (range 0.57–1.00) corresponding to 87% of planned dose-intensity.

response to treatment

As shown in Table 2, the best overall response to study treatment by combined CA-125 and RECIST criteria was PR in approximately one-quarter of the patients overall (17 patients, 24.6%). As expected, response rates were lower in the short (<6 months) PFI subgroup than in the longer (6–12 months) PFI subgroup. Almost one-third of the patients had SD, overall as well as per PFI subgroup. PD occurred in 24 patients overall (34.8%), clearly more in the PFI <6 months subgroup (42%) than in the PFI ≥6 months subgroup (16%).

Table 2.

Summary of best overall response by combined CA-125 and/or RECIST criteria, final assessment after radiology expert’s review (ITT/EE population)

| Best response after radiology expert’s review | PFI (N = 69) |

Overall (N = 69) | |

| <6 months (n = 50) | ≥6 months (n = 19) | ||

| Best overall responsea | |||

| CR, n (%) | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| PR, n (%) | 8 (16.0) | 9 (47.4) | 17 (24.6) |

| SD, n (%) | 16 (32.0) | 6 (31.6) | 22 (31.9) |

| PD, n (%) | 21 (42.0) | 3 (15.8) | 24 (34.8) |

| UK, n (%) | 5 (10.0) | 1 (5.3) | 6 (8.7) |

| Response rate | |||

| CR + PR, n (%) | 8 (16.0) | 9 (47.4) | 17 (24.6) |

Best overall response is the combined analysis of CA-125/RECIST criteria in the assessment of all target/nontarget lesions.

ITT, intention-to-treat; EE, efficacy evaluable; PFI, progression-free interval; CR, complete response, PR, partial response; SD, stable disease; PD, progressive disease; UK, unknown.

Results are quite similar when considering only the patients assessable by RECIST, as displayed in Table 3. Of the 14 patients who achieved PR, only four had received one prior therapy line, while seven had received two and the rest three prior therapy lines. Five patients had liver metastasis (one of them with bulky disease). All showed responses in liver lesions with two of them achieving complete disappearance of target and nontarget liver lesions.

Table 3.

Best overall response by RECIST criteria after radiology expert’s review (ITT/EE population)

| Investigator and/or expert assessment | PFI (N = 54) |

Overall response (N = 54) | |

| <6 months (n = 40) | ≥6 months (n = 14) | ||

| CR, n (%) | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| PR, n (%) | 7 (17.5) | 7 (50.0) | 14 (25.9) |

| SD, n (%) | 11 (27.5) | 4 (28.6) | 15 (27.8) |

| PD, n (%) | 15 (37.5) | 3 (21.4) | 18 (33.3) |

| UK, n (%) | 7 (17.5) | 0 | 7 (13.0) |

ITT, intention-to-treat; EE, efficacy evaluable; PFI, progression-free interval; CR, complete response, PR, partial response; SD, stable disease; PD, progressive disease; UK, unknown.

Twelve patients had normalization of CA-125 for at least 4 weeks; nine of them were also assessable by RECIST with six PR and three SD; the three remaining patients were responders by CA-125 only. A 50% CA-125 decrease was already observed at cycle 1 in 14 patients, which was then confirmed at least 4 weeks later.

Drug activity was maintained when results were analyzed by number of prior therapies or prior use of liposomal doxorubicin with, respectively, a response rate of 21% (7 of 33 patients) and 29% (5 of 17 patients) when gimatecan was given as third or fourth therapy line and 17% (4 of 23 patients) or 50% (5 of 10 patients) when gimatecan was administered after a prior liposomal doxorubicin given as second or third therapy line.

Table 4 summarizes the median TTP, response duration and SD duration (CR/PR/SD as best response).

Table 4.

TTP, response duration and SD duration

| PFI (N = 69) |

Overall | ||

| <6 months | ≥6 months | ||

| Median TTP (months) (95% CI) | 2.9 (2.0–3.9) (n = 50) | 6.3 (4.6–8.3) (n = 19) | 3.8 (2.8–5.7) (N = 69) |

| Median time with CR/PR (months) (95% CI) | 7.6 (3.6–9.9) (n = 8) | 6.9 (5.7–NR) (n = 9) | 7.6 (6.2–9.9) (n = 17) |

| Median time with SD (months) (95% CI) | 5.9 (4.0–6.9) (n = 24) | 7.4 (5.1–12.2) (n = 15) | 6.3 (5.7–7.2) (n = 39) |

TTP, time to progression; SD, stable disease; PFI, progression-free interval; CI, confidence interval, CR, complete response, PR, partial response, NR, not reached.

Time to response ranged between 26 days and 113 days, with a median value of 56 days.

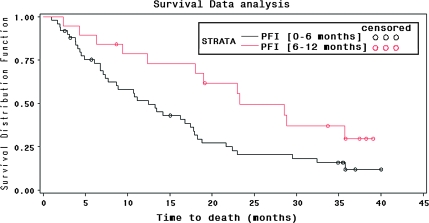

Survival results are shown in Figure 1 for the subgroups with PFI <6 and ≥6 months. Median overall survival time was 16.2 months (95% CI 11.2–19.0). Median survival time was longer, as expected, in the PFI ≥6 months subgroup, being 23.3 months, while the time observed in the PFI <6 months subgroup was 12.4 months.

Figure 1.

Kaplan–Meier survival curves by progression-free interval (PFI).

toxicity

All patients included experienced at least one AE, with a mean of 4.5 AEs per patient. Unsuspected and suspected AEs were reported in 81.2% and 95.7% of patients, respectively. Table 5 lists the suspected grade 3 and grade 4 AEs as well as the suspected AEs reported in >15% of patients.

Table 5.

Most relevant suspected AEs by worst NCI-CTC grade

| System organ class preferred term | Safety population (N = 69) |

||||

| Grade 1, n (%) | Grade 2, n (%) | Grade 3, n (%) | Grade 4, n (%) | Total, n (%) | |

| Anemia | 7 (10.1) | 21 (30.4) | 6 (8.7) | 3 (4.3) | 37 (53.6) |

| Febrile neutropenia | 0 | 0 | 1 (1.4) | 1 (1.4) | 2 (2.9) |

| Leukopenia | 3 (4.3) | 10 (14.5) | 9 (13.0) | 4 (5.8) | 26 (37.7) |

| Neutropenia | 1 (1.4) | 9 (13.0) | 14 (20.3) | 12 (17.4) | 36 (52.2) |

| Thrombocytopenia | 9 (13.0) | 6 (8.7) | 10 (14.5) | 5 (7.2) | 30 (43.5) |

| Constipation | 8 (11.6) | 6 (8.7) | 0 | 0 | 14 (20.3) |

| Diarrhea | 13 (18.8) | 8 (11.6) | 4 (5.8) | 0 | 25 (36.2) |

| Nausea | 25 (36.2) | 22 (31.9) | 1 (1.4) | 0 | 48 (69.6) |

| Vomiting | 25 (36.2) | 9 (13.0) | 2 (2.9) | 0 | 36 (52.2) |

| Abdominal pain upper | 3 (4.3) | 5 (7.2) | 1 (1.4) | 0 | 9 (13) |

| Asthenia | 8 (11.6) | 17 (24.6) | 0 | 0 | 25 (36.2) |

| Fatigue | 10 (14.5) | 3 (4.3) | 0 | 0 | 13 (18.8) |

| Anorexia | 9 (13.0) | 3 (4.3) | 0 | 0 | 12 (17.4) |

| Bone pain | 0 | 0 | 1 (1.4) | 0 | 1 (1.4) |

| Osteonecrosis | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 (1.4) | 1 (1.4) |

| Epistaxis | 2 (2.9) | 0 | 1 (1.4) | 0 | 3 (4.3) |

| Alopecia | 8 (11.6) | 4 (5.8) | 0 | 0 | 12 (17.4) |

AEs, adverse events; NCI CTC, National Cancer Institute Common—Toxicity Criteria.

The majority of suspected AEs were gastrointestinal toxic effects affecting 82.6% of patients. Grade 3 diarrhea was reported in only 5.8% of patients while no grade 4 events were recorded. A withdrawal from the study was observed in 4.3% of patients for nausea and in 2.9% for vomiting.

The second most frequent AEs were myelosuppression (69.6% of patients), leading to complications (febrile neutropenia) only in 2.9% of cases. A withdrawal from the study was observed in 5.8% of patients for thrombocytopenia, in 2.9% for neutropenia and in one for febrile neutropenia (1.4%).

The third most frequently observed suspected AEs were asthenia (36.2% of patients) and fatigue (18.8% of patients), but these were all considered mild to moderate (grade 2 or less).

No drug-related deaths occurred. Most of the deaths during the study were due to disease progression.

Dose reductions due to neutropenia or thrombocytopenia occurred in 11 (16%) patients, while dose delays for hematological toxicity were recorded in 28 patients (41%).

Treatment with growth factors during the study period involved 25 patients (36%) and 58 of 312 (18.6%) cycles administered. Twelve patients (17.4%) required transfusion with either red blood cells (11.6%) or platelets (10.1%).

Hemoglobin, neutrophils and platelets decreases were the most frequent hematological abnormalities. The median nadir for neutrophils was 1.65 × 109/L (range 0.01–8.17) and for platelets was 141 × 109/L (range 2–457). The median time to nadir for these parameters was 22 days at cycle 1 and ∼20 to 22 days when all cycles of treatment are considered.

The ECOG performance status was zero in almost three-quarters of the patients (73%) at baseline, in 69% of patients at cycle 1 and in 63% of patients at the end of the last cycle. The proportion of patients with ECOG performance status of one remained practically constant at baseline, cycle 1 or last cycle.

discussion

Our study showed that gimatecan is an active drug in patients with epithelial ovarian, fallopian tube or peritoneal cancer, progressing or recurring during or after prior treatment with platinum compounds and taxanes and whether or not previously treated by anthracyclines. An overall response of 16% in patients with PFI <6 months and 47.4% in those with PFI ≥6 months was found by combining CA-125 and RECIST criteria and assessed by an independent radiology expert’s review. These responses were obtained after a median of 56 days and were maintained for a median of 7.6 months in the cohort of patients with PFI <6 months and 6.9 months for those with a PFI ≥6 months, while median TTP in both cohorts were 2.9 months and 6.3 months, respectively. These results were obtained at the cost of manageable toxicity.

Activity as expressed by a PR by CA-125 and/or RECIST criteria was three times higher in the subgroup of patients with PFI ≥6 months compared with those with a PFI <6 months (47.4% versus 16%). Similarly, the proportion of patients with PR or disease stabilization was much higher among patients with a PFI ≥6 months (78% versus 48%). Among the patients who showed a decrease in CA-125, almost half achieved a marker normalization.

As expected, the proportion of responders was very much influenced by the interval after platinum therapy, being more clear-cut in the subgroup of patients with PFI ≥6 months versus those with PFI <6 months.

Interestingly, the duration of response was independent from the PFI, being of at least 6 months in almost 73% and 75% of the patients with PFI <6 months and PFI ≥6 months, respectively. However, SD duration was longer among patients with PFI ≥6 months (7.4 versus 5.9 months, respectively). Correspondingly, the median TTP was longer for the subgroup with PFI ≥6 months.

The median survival of 1 year observed in the PFI <6 months subgroup seems interesting, especially considering that 82% of this population had received at least two or three prior chemotherapy regimens and that 22% of these patients were refractory (presenting PD or SD) to a prior platinum therapy. The median survival of 2 years in the PFI >6 months subgroup is also interesting for a future development of the product in this indication.

The durable responses and disease stabilization observed in the study could potentially transform in a clinical benefit for the patients.

All patients were included in the analysis of safety. A number of cycles equal or greater than six was administered in 25 patients (36.2%), and all together 312 cycles were delivered, showing that the oral therapy with gimatecan was well tolerated. The lack of an evident ECOG performance status deterioration during treatment seems to confirm the good safety profile of gimatecan.

At least one dose reduction or dose delay were observed in 31.9% or 59.4% of patients, respectively. Hematological toxicity, mainly neutropenia, was the most frequent reason for dose reduction in 16% of patients, and for dose delay in 41%. Despite dose reduction or delays, a rather high-dose intensity could be maintained during the study, with a median value of 0.87 mg/m2/week versus a theoretical value of 1 mg/m2/week. Growth factor use affected 18.6% of cycles.

The main toxicity was myelosuppression (neutropenia and thrombocytopenia). However, the incidence of febrile neutropenia was quite low (two patients, 2.9%), one patient interrupted treatment because of this event and the other had dose reduced to 3.2 mg/m2.

Although the AEs reported in this study were those expected with this therapeutic class, there seems to be a low incidence of myelosuppression and diarrhea grade 3 and 4. Neutropenia grade 4 occurred in 17.4% of patients treated with gimatecan, while it is reported in 77% of patients receiving topotecan. The rate of grade 4 neutropenia with fever/infection was 1.4% in this study and may be as high as 23% in patients receiving topotecan [13].

Diarrhea grade 4 was never observed with gimatecan, while grade 4 late diarrhea occurred in ∼10% of irinotecan-treated patients [14]. The presence of diarrhea never caused treatment interruption. Gastrointestinal AEs such as nausea and vomiting were overall manageable, never precluding therapy administration except in one case. Gimatecan did not produce hepatotoxicity or sensory neuropathy, which are observed with, respectively, trabectedin and the new epothilones [5, 15, 16].

These observations are particularly relevant since 42% of patients in this study were elderly, and 72.4% had received two or three prior therapy lines, making them more likely to present enhanced toxicity related to myelosuppression.

With the limitation that interpretation of activity and safety from this trial is not on the basis of comparative data, the conclusion that may be driven is that gimatecan has shown to be active in previously treated ovarian cancer, with a manageable safety profile. The high proportion of patients who achieve durable responses and disease stabilization, together with the lack of deterioration of performance status and the observed tolerability profile, with myelosuppression as main toxicity, may justify further evaluations of this new oral drug in the proposed indication.

funding

sigma-tau Industrie Farmaceutiche Riunite S.p.A.

disclosure

The following coauthors have declared a conflict of interest: PB and PC, sigma-tau employees. The other coauthors report no conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

The trial has been presented in part at the 42nd Annual Meeting of American Society of Clinical Oncology, Atlanta, GA, 2–6 June 2006 and at the 11th International Gynecologic Cancer Society Meeting, Santa Monica, CA, 14–18 October 2006. We wish to thank Eliette Sudriez-Zazzi, Debioclinic S.A., France, for study management and Patrice Bacquet, Debioclinic S.A., France, for data management and statistical analysis.

References

- 1.Markman M, Markman J, Webster K, et al. Duration of response to second-line, platinum-based chemotherapy for ovarian cancer: implications for patient management and clinical trial design. J Clin Oncol. 2004;22:3120–3125. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2004.05.195. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Gordon AN, Fleagle JT, Guthrie D, et al. Recurrent epithelial ovarian carcinoma: a randomized phase III study of pegylated liposomal doxorubicin versus topotecan. J Clin Oncol. 2001;19(14):3312–3322. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2001.19.14.3312. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bokkel Huinink W, Gore M, Carmichael J, et al. Topotecan versus paclitaxel for the treatment of recurrent epithelial ovarian cancer. J Clin Oncol. 1997;15(6):2183–2193. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1997.15.6.2183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Pfisterer J, Plante M, Vergote I, et al. Gemcitabine plus carboplatin compared with carboplatin in patients with platinum-sensitive recurrent ovarian cancer: an intergroup trial of the AGO-OVAR, the NCI CTG, and the EORTC GCG. J Clin Oncol. 2006;24(29):4699–4707. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2006.06.0913. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sessa C, De Braud F, Perotti A, et al. Trabectedin for women with ovarian carcinoma after treatment with platinum and taxanes fails. J Clin Oncol. 2005;23(9):1867–1874. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.09.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sessa C, Cresta S, Cerny T, et al. Concerted escalation of dose and dosing duration in a phase I study of the oral camptothecin gimatecan (ST1481) in patients with advanced solid tumors. Ann Oncol. 2007;18:561–568. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdl418. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Vermorken JB, Parmar MKB, Brady MF, et al. Clinical trials in ovarian carcinoma: study methodology. Ann Oncol. 2005;16(Suppl 8):viii20–viii29. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdi963. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Rustin GJS, Quinn M, Thigpen T, et al. New guidelines to evaluate the response to treatment in solid tumors (ovarian cancer) J Natl Cancer Inst. 2004;96(6):487–488. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djh081. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ozer H, Armitage JO, Bennet CL, et al. 2000 update of recommendations for the use of hematopoietic colony-stimulating factors: evidence-based, clinical practice guidelines. J Clin Oncol. 2000;18(20):3558–3585. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2000.18.20.3558. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Therasse P, Arbuck SG, Eisenhauer EA, et al. New guidelines to evaluate the response to treatment in solid tumors. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2000;92(3):205–216. doi: 10.1093/jnci/92.3.205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Rustin GJS. Can we now agree to use the same definitions to measure response according to CA-125? J Clin Oncol. 2004;22(20):4035–4036. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2004.06.628. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Simon R. Optimal two-stage designs for phase II clinical trials. Control Clin Trials. 1989;10:1–10. doi: 10.1016/0197-2456(89)90015-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Topotecan Summary of Product Characteristics http://www.emea.europa.eu/humandocs/Humans/EPAR/hycamtin/hycamtin.htm(21 October 2009, date last accessed) [Google Scholar]

- 14. Irinotecan Prescribing Information, revised July 2008 http://www.pfizer.com/files/products/uspi_camptosar.pdf (21 October 2009, date last accessed) [Google Scholar]

- 15.Monk BJ, Herzog T, Kaye S, et al. A randomized phase III study of trabectedin with pegylated liposomal doxorubicin (PLD) versus PLD in relapsed, recurrent ovarian cancer. Ann Oncol. 2008;19(Suppl 8):viii1–viii4. doi: 10.1016/j.ygyno.2012.06.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Thomas E, Tabernero J, Fornier M, et al. Phase II clinical trial of ixabepilone (BMS-247550), an epothilone B analogue, in patients with taxane-resistant metastatic breast cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2007;25(23):3399–3406. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2006.08.9102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]