Abstract

Desmosterolosis is a rare, autosomal recessive, human disease characterized by multiple congenital anomalies in conjunction with grossly elevated levels of desmosterol and markedly reduced levels of cholesterol in all bodily tissues. Herein, we evaluated retinal sterol composition, histology, and electrophysiological function in an animal model that exhibited the biochemical features of desmosterolosis, produced by treating pregnant rats and their progeny with U18666A, an inhibitor of desmosterol reductase. Treated rats had cataracts, were substantially smaller, and had markedly high levels of desmosterol and profoundly low levels of cholesterol in their retinas and other tissues compared to age-matched controls. However, their retinas were histologically normal and electrophysiologically functional. These results suggest that desmosterol may be able to replace cholesterol in the retina, both structurally and functionally. These findings are discussed in the context of “sterol synergism”.

Keywords: Cholesterol, desmosterol, electroretinogram, rat, retina, sterol, U18666A

INTRODUCTION

The primary focus of research in our lab concerns the biological functions of cholesterol and other isoprenoid lipids in the retina, particularly as they are involved in the process of retinal rod outer segment (ros) membrane renewal and the maintenance of photoreceptor cell structure, viability, and function (reviewed in (1)). Pharmacological perturbation of the de novo pathway of cholesterol biosynthesis can produce cataracts (reviewed in (2)) as well as teratogenic anomalies in animals (3-6). In humans, there are two known hereditary diseases caused by defects in cholesterol biosynthesis that involve penultimate enzymes in the de novo pathway: the Smith-Lemli-Opitz syndrome (7)(SLO; reviewed in (8,9), and desmosterolosis (10,11). Unlike most hereditary metabolic diseases, these disorders affect anabolic, rather than catabolic, metabolism and follow an autosomal recessive inheritance pattern. Both of these diseases are often lethal, and involve multiple, dysmorphic, congenital anomalies, profound mental retardation, and failure to thrive.

The distinguishing biochemical hallmark of desmosterolosis is the accumulation of excessive levels of desmosterol and severely reduced levels of cholesterol in bodily tissues, consistent with a genetic defect in desmosterol reductase (3β-hydroxysterol-Δ24-reductase) (10,11). Phenotypic defects associated with this disease include macrocephaly, ambiguous genitalia, osteosclerosis, craniofacial abnormalities, and short limbs. The existing literature does not address the occurrence of any ocular abnormalities (e.g., cataracts, retinal dystrophy, etc.) associated with this disease. Desmosterol reductase can be inhibited with experimental drugs, such as triparanol (12-14), 20,25-diazacholesterol (14,15), and U18666A (3-β(2-diethylaminoethoxy) androst-5-en-3-one hydrochloride) (16-18) (see Fig. 1), resulting in accumulation of desmosterol and reduction of cholesterol levels in treated cells and tissues. At very high concentrations, U18666A also can inhibit oxidosqualene cyclase, which also would result in reduced cholesterol levels and accumulation of squalene-2,3-epoxide and other polar lipid products in treated cells and tissues (17-19). Postnatal treatment of neonatal rats with U18666A causes cataracts as well as epileptic-like brain dysfunction (20-22), while triparanol treatment can cause similar abnormalities as well as profound teratogenic effects, particularly in the developing nervous system, during embryogenesis (3, 23-25) However, recent studies in our lab have shown no apparent cytological effects in the retinas of rats treated postnatally for three weeks with U18666A (26).

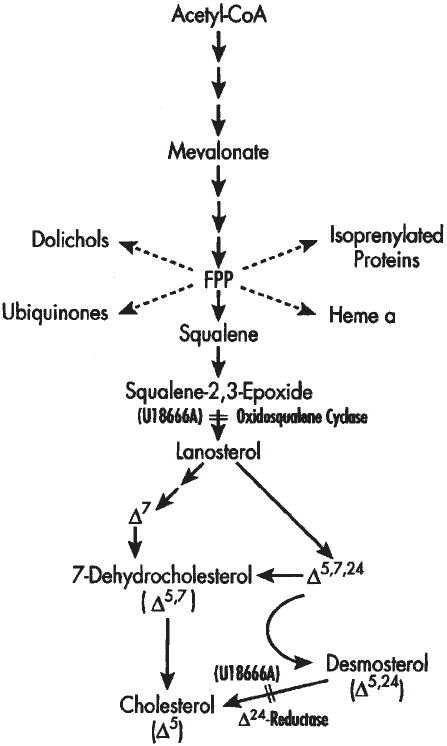

Fig. 1.

Simplified schematic of the de novo pathway of cholesterol biosynthesis. At relatively low concentrations, U18666A inhibits cholesterol synthesis at the level of a penultimate enzyme in the pathway, desmosterol (Δ24) reductase. A secondary site of action (at high concentrations of U18666A) is at the level of oxidosqualene cyclase.

In the present study, we sought to examine the structure and function of the retina under conditions that mimicked the biochemical features of desmosterolosis, using pre- and postnatal administration of U18666A in rats to produce elevated desmosterol concentrations and reduced cholesterol levels. Using this animal model of the disease, we found that the retina exhibited remarkable resilience to any structural or functional consequences that might be predicted to occur from such gross alteration of its normal biochemistry.

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURE

Materials

Unless otherwise stated, all reagents and lipid standards were of analytical reagent grade or higher, and used as purchased from Sigma Chemical Co. (St. Louis, MO). Desmosterol (cholesta-5,24-dien-3β-ol; Δ5,24) was from Steraloids, Inc. (Wilton, NH). 7-Dehydrodesmosterol (cholesta-5,7,24-trien-3β-ol; Δ5,7,24) was a generous gift from Dr. W. David Nes (Texas Tech University, Lubbock, Tx). 8-Dehydrocholesterol (cholesta-5,8-dien-3β-ol; Δ5,8) was a generous gift from Dr. George J. Schroepfer, Jr. (Rice University, Houston, TX). 7-Dehydrocholesterol (cholesta-5,7-dien-3β-ol; Δ5,7) was purchased from Research Plus, Inc. (Bayonne, NJ). U18666A was a generous gift from The Upjohn Co. (Kalamazoo, MI). All organic solvents were HPLC grade (Burdick & Jackson, McGraw Park, IL). Microscopy supplies were obtained from Electron Microscopy Sciences (Fort Washington, PA) and from Polysciences, Inc. (Warrington, PA).

Animals

All procedures performed on animals were in compliance with the NIH Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals and with the ARVO Resolution on the Use of Animals in Research. Female Sprague-Dawley rats (200–250 g; Harlan Sprague Dawley, Inc., Indianapolis, IN) and their litters (11–14 pups each) were maintained under cyclic lighting (12 h light, 12 h dark; standard fluorescent room illumination) in clear plastic cages, at 70–75°C ambient temperature, with ad lib access to water. Animals were euthanised by lethal intraperitoneal injection with sodium pentobarbital (Beuthanasia®).

U18666A Treatment

U18666A was mixed with cholesterol-free, powdered rat chow (Ralston Purina, St. Louis), 1 mg U18666A per 100 g of chow. Pregnant rats were fed 40 g of chow per day throughout the time course of the experiment (gestational day 6 through postnatal day 28); control dams received the same chow, minus U18666A. In addition, starting at postnatal day one (P1), surviving pups in the treatment group were injected subcutaneously every other day with U18666A (15 mg/kg), prepared as an olive oil suspension, for four weeks (see Fig. 2). Control pups received olive oil vehicle injections alone. In this series, all of the treated animals developed dense nuclear cataracts by P21, whereas cataracts were not observed in any of the control animals.

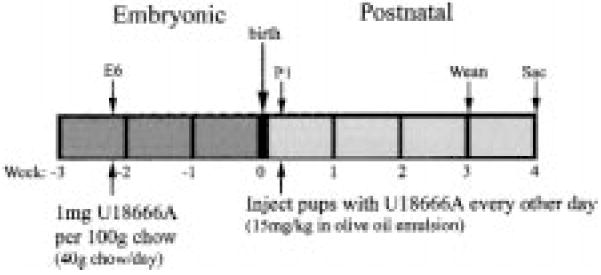

Fig. 2.

Protocol for treatment of rats with U18666A. (See “Experimental Procedure” for details).

Lipid Analysis

These procedures are essentially as described previously (27). In brief, retinas and lenses from P28 animals were harvested in pairs, pooling the tissues from both eyes of a given animal. Intracardiac blood (ca. 1-2 ml) was drawn, allowed to clot, and serum was obtained by centrifugation. Conditions for saponification, extraction of nonsaponifiable lipids, and analysis of the nonsaponifiable lipids by HPLC were as described previously (27,28). For these analyses, we employed a Phenomenex IB-SIL 3 C18 BDS (150 × 4.6 mm) reverse-phase column, with a Waters/Millipore NovaPak C18 guard column (mobile phase, MeOH at 1 ml/min; detection at 205nm). Using this system, relative retention times (relative to that of cholesterol (Δ5), 1.00) for the following authentic isoprenoid lipid reference standards were obtained: 7-dehydrocholesterol, 0.70; demosterol, 0.79; 8-dehydrocholesterol, 0.83; 7-dehydrocholesterol, 0.89; squalene, 1.21; HPLC peak assignments were made in comparison with these reference standards, and each sterol was quantified by integrated peak area analysis in comparison with the empirically determined response factor (integration units per nmol) for the given standard compound. The relative response actors (relative to cholesterol, 1.00) were as follows: cholesta-5,7,24-trien-3β-ol, 2.78; desmosterol, 2.53; 7-dehydrocholesterol, 1.10; squalene, 12.89.

Subcellular fractionation

Purified ros membranes and a “residual retina” membrane fraction (ros-depleted retinal membranes) were prepared from two groups of four pooled rat retinas each by discontinuous sucrose gradient ultracentrifugation, using a minor modification (28) of a procedure originally designed for frog retina (27). Sucrose solutions of 36%, 32%, and 26% sucrose (by wt) were employed, and ros membranes were harvested from the 26%/32% interface.

Histology

Eyes from P1 and P28 treated and control animals were fixed by immersion in 10% neutral-buffered formalin (2–4 days), processed by automated paraffin embedment, and whole eye tissue sections (4–6 μm thickness) were collected onto glass microscope slides and stained with hematoxylin/eosin (H & E) (29). Tissue processing was performed in the Histopathology Laboratory, Department of Pathology, Saint Louis University School of Medicine. Sections were examined and photographed with an Olympus BH-2 photomicroscope, using either a 2.5X or 20X magnification objective.

Electroretinography

To assess the electrophysiological competence of the retina, animals were tested by electroretinography. Following dark adaptation overnight, rats were anesthetized (intraperitoneal injection of a ketamine (60 mg/kg)-xylazine (7 mg/kg) mixture) and placed on a heating pad. Electroretinograms (ERGs) were recorded as described in detail elsewhere (30). The a-wave amplitude was measured from the pre-stimulus baseline to the trough of the a-wave. The b-wave amplitude was measured to the positive peak, either from the trough of the a-wave or (if no a-wave was present) from the baseline. Implicit times were measured from the time of stimulus presentation to the a-wave trough or the b-wave peak. The data were analyzed statistically, using a two-way, repeated measure analysis of variance (ANOVA).

RESULTS

Gross Phenotypic Features and Ocular Histology

Neonatal rats in both the control and treated groups appeared generally healthy at birth and did not exhibit any obvious gross anatomical abnormalities. At P1, the mean body weights of pups in the treated group (7.2 ± 0.6 g, N=11) and control group (7.0 ± 0.5, N=14) were not significantly different. Over the four-week postnatal treatment course, however, the growth rate of animals in the treated group significantly lagged behind that of control animals. By P28, mean body weight of treated animals was only ca. 36% of controls (36.1 ± 1.7 g compared to 99.1 ± 5.7 g, respectively). Also, there was only an 18% survival of the treated animals by P28, compared with 100% in the control group. However, no dysmorphic features were apparent in either group.

The gross ocular anatomy and retinal histology of treated and control animals at P1 are shown in Figure 3. The eyes of treated animals exhibit morphological and histological features comparable to those in the age-matched controls, indicating that U18666A did not disrupt the normal patterns of ocular development under the conditions employed. Also, while the lens is relatively well-formed even at this early postnatal stage, no evidence of cataracts is present. At this stage of development, the majority of the neural retina consists of thick neuroblastic layer of mitotic, migrating cells (asterisk, Fig. 3C), although a ganglion cell layer (gcl) and an incipient inner plexiform layer (ipl) already are clearly evident (Fig. 3C and 3D). Importantly, there are no indications of disrupted cell fate or cytological abnormalities, such as increased pyknosis, dysplastic features (e.g., rosettes), or abnormal inclusions (e.g., “myelin figures”), as a consequence of exposure to U18666A.

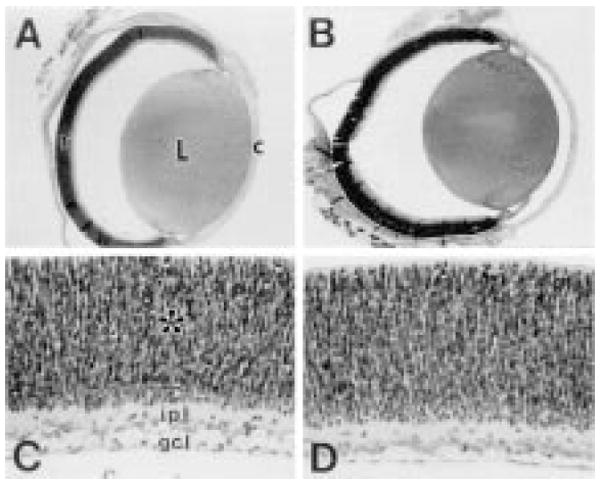

Fig. 3.

Gross ocular anatomy and retinal histology of P1 control and U18666A-treated rats. (A, C) control; (B, D) U18666a-treated. Upper panels: vertical cross-sections of paraffin-embedded eyes (hematoxylin/eosin stain), illustrating the comparable gross anatomical features of control and treated eyes, including the lens (L), cornea (c), and neural retina (r). Lower panels: Corresponding histological sections of retinas from pericentral region of each eye, exhibiting the normal cytological features and organization of the P1 rat retina. The ganglion cell layer (gcl), inner plexiform layer (ipl), and neuroblastic layer (asterisk) are indicated.

By P28, the normal rat neural retina has undergone dramatic differentiation and is matured almost to completion. Fig. 4 shows the histological appearance of a control (Fig. 4A) and a U18666A-treated rat retina (Fig. 4B) at P28. At the light microscopic level, the two images are virtually identical in most respects. Normal retinal histological organization and cytology are observed; there is no evidence of increased cell death, gliosis, or other pathological features. Qualitatively, the thickness of the retinal cell layers are comparable between treated and control retinas. The rod outer segments appear to be of normal length (ca. 25–28 μm) and exhibit a characteristic orderly alignment. The normalcy of retinal structure is in striking contrast to the profound disruption of normal lens cytology, as evidenced by the fact that all of the treated animals had dense lenticular opacities (cataracts) at P28.

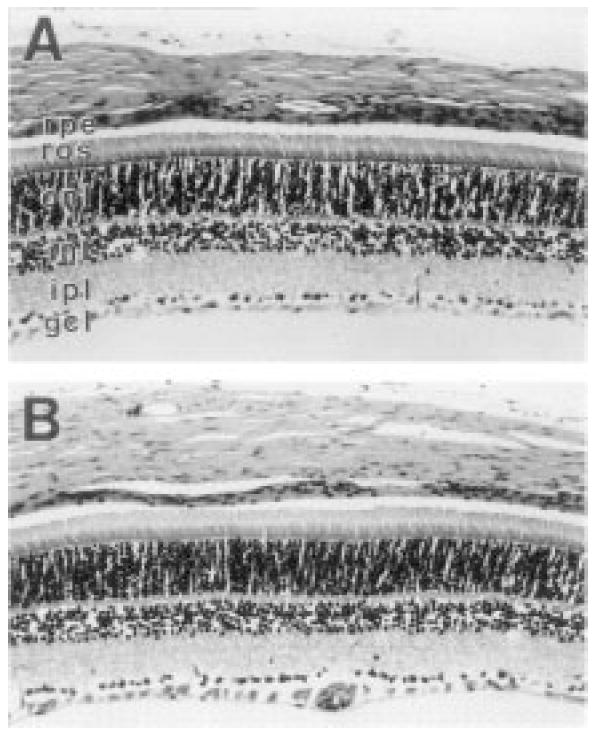

Fig. 4.

Histology of retina from P28 control and U18666A-treated rats. (A) Control; (B) U18666a-treated. Longitudinal sections (4-μm thickness, paraffin), hematoxylin/eosin stain. Normal, lamellar stratification and thickness of retinal cells layers is observed in both specimens: rpe, retinal pigment epithelium; ros, rod outer segment layer; onl, outer nuclear layer; inl, inner nuclear layer; ipl, inner plexiform layer; gcl, ganglion cell layer.

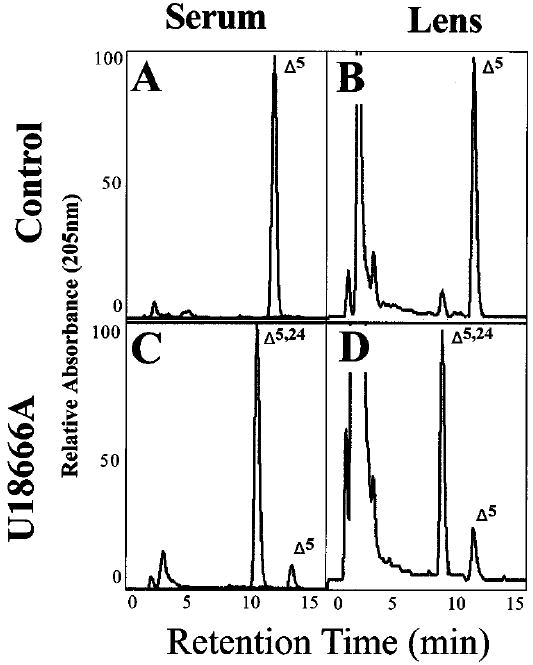

Effects of U18666A on Tissue Sterol Composition

The reverse-phase HPLC chromatograms obtained from representative samples of sera and lenses of P28 treated and control animals are shown in Fig. 5. Monitoring the sterol profile of the serum is a good way to determine the “global”, systemic effects of a drug like U18666A (which was administered systemically). The dominant peak, by far, in the chromatogram of serum from treated animals (Fig. 5C) corresponds to desmosterol (Δ5,24), whereas the cholesterol peak (Δ5) is diminutive. In contrast, cholesterol is virtually the only sterol detected in control serum (Fig. 5A). Hence, marked alterations in the serum sterol profile of treated animals were observed, as expected. Similarly, profound differences in the sterol profiles of lenses from treated rats (Fig. 5D) were observed, compared to controls (Fig. 5B), although desmosterol is an appreciable, but minor, component in the normal lens. These striking biochemical differences are at least consistent with the results of prior studies that have employed U18666A under similar conditions (16,17,21,26).

Fig. 5.

Reverse-phase HPLC chromatograms of the nonsaponifiable lipids from P28 control and U18666A-treated rats. Left-hand panels (A, C), serum lipids; right-hand panels (B, D), lens lipids. Upper panels (A, B) from controls; lower panels (C, D) from treated animals. Full-scale relative absorbance (at 205 nm) is adjusted to the predominant sterol component. The elution positions of cholesterol (Δ5) and desmostero1 (Δ5,24) are indicated.

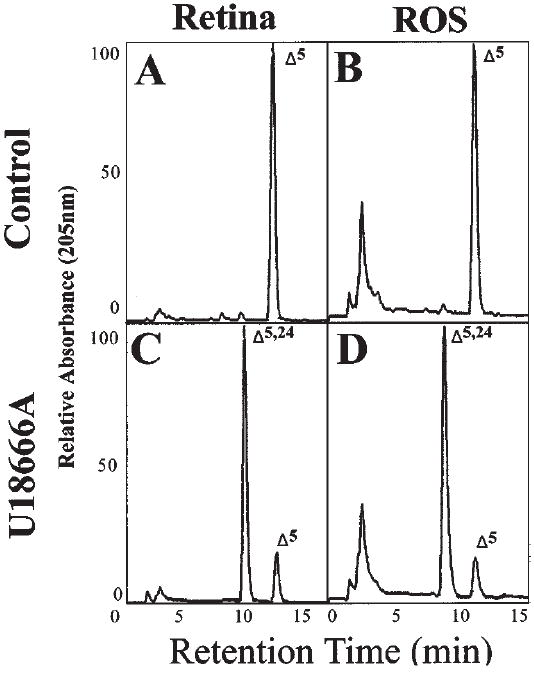

The dominance of desmosterol again is evident in the HPLC profiles obtained from retinal ros membranes and the “residual retina” membrane fraction of U18666A-treated P28 rats (Fig. 6D and 6C, respectively). This is in striking contrast to control ros membranes (Fig. 6B) and the corresponding residual retina membrane fraction (Fig. 6A), where cholesterol is, by far, the predominant sterol component. Qualitatively, there appears to be little or no enrichment of desmosterol in one or the other membrane fraction under either condition.

Fig. 6.

Reverse-phase HPLC chromatograms of retina nonsaponifiable lipids from P28 control and U18666A-treated rats. Left-hand panels (A, C), residual retina; right-hand panels (B, D), rod outer segment (ROS) membranes. Upper panels (A, B) from controls; lower panels (C, D) from treated animals. Full-scale relative absorbance (at 205 nm) is adjusted to the predominant sterol component. The elution positions of cholesterol (Δ5) and desmostero1 (Δ5,24) are indicated.

It should be noted that one cannot make a direct semi-quantitative comparison of the relative amounts of desmosterol and cholesterol on the basis of peak heights, since the molar response factor (absorption coefficient at 205 nm) for desmosterol is about 2.5-times that of cholesterol (see “Experimental Procedure”). Taking the molar response factors into account, the quantitative sterol composition data obtained from the HPLC analyses are shown in Table I. Serum cholesterol levels in treated animals were only about 5% of control levels and the total serum sterol levels were only one-third of control levels. The desmosterol content of serum from treated animals was more than five-fold that of cholesterol on a molar basis. These results are consistent with the known pharmacology of U18666A (16-21,26). In lenses of treated animals, the cholesterol content was only 11.5% of control values, while desmosterol levels were 635 times greater than in controls. Hence, the average value for the desmosterol/cholesterol mole ratio of control lenses was 0.037, compared to 2.08 for lenses from the treated animals. Also, the total sterol content of lenses in treated animals was only about one-third of control values (34.1%). The desmosterol/cholesterol mole ratio in control ros and residual retina membranes is 0.012 (i.e., cholesterol accounts for ca. 99% of the total sterol), as compared to values of 3.17 and 2.50, respectively, in ros and residual retina membranes from U18666A-treated rats. These latter data indicate a somewhat selective enrichment of desmosterol in ROS membranes in the treated animals, compared to other retinal membranes (contrary to the qualitative assessment of their HPLC chromatograms described above), and show that only about one-fourth of the total sterols in the ros of treated animals is cholesterol. Although the total sterol content of retinas (“residual retina” plus ros membranes) from the P28 treated animals (ave. 31.6 nmol/retina) is only about 63% that of age-matched control retinas (ave. 50.1 nmol/retina), the majority of this difference may be accounted for by the substantially smaller eye size of the treated animals, compared to controls.

Table I.

Sterol Composition of Tissues from U18666A-Treated and Control Rats (P28)

| Sterol |

Mol Ratio | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cholesterol (Δ5) | Desmosterol (Δ5,24) | Total | Δ5,24/Δ5 | |

| Serum (μmol/ml) | ||||

| Control (4) | 1.90 ± 0.16 | 0 | 1.90 ± 0.16 | 0 |

| +U18666A (4) | 0.10 ± 0.02 | 0.54 ± 0.16 | 0.64 ± 0.18 | 5.4 |

| % control | 5.3 | — | 33.7 | — |

| Lens (nmol/lens) | ||||

| Control (3) | 5.32 ± 0.33 | 0.20 ± 0.04 | 5.52 ± 0.38 | 0.037 |

| +U18666A (3) | 0.61 ± 0.08 | 1.27 ± 0.14 | 1.88 ± 0.21 | 2.08 |

| % control | 11.5 | 635 | 34.1 | 5,622 |

| Residual Retina (nmol/retina) | ||||

| Control (2) | 47.7 | 0.57 | 48.3 | 0.012 |

| +U18666A (2) | 8.6 | 21.5 | 30.1 | 2.50 |

| % control | 18.2 | 3,772 | 62.3 | 20,833 |

| ROS Membranes (nmol/retina) | ||||

| Control (2) | 1.73 | 0.02 | 1.75 | 0.012 |

| +U18666A (2) | 0.36 | 1.14 | 1.50 | 3.17 |

| % control | 20.8 | 5,700 | 85.7 | 26,417 |

Tissues from 28-day old rats were harvested, saponified, and the nonsaponifiable lipids were extracted with petroleum ether and analyzed by reverse-phase HPLC. Identity and quantity of each sterol were determined in comparison with retention times and molar response factors of authentic sterol standards. Numbers in parentheses indicate number of independent samples.

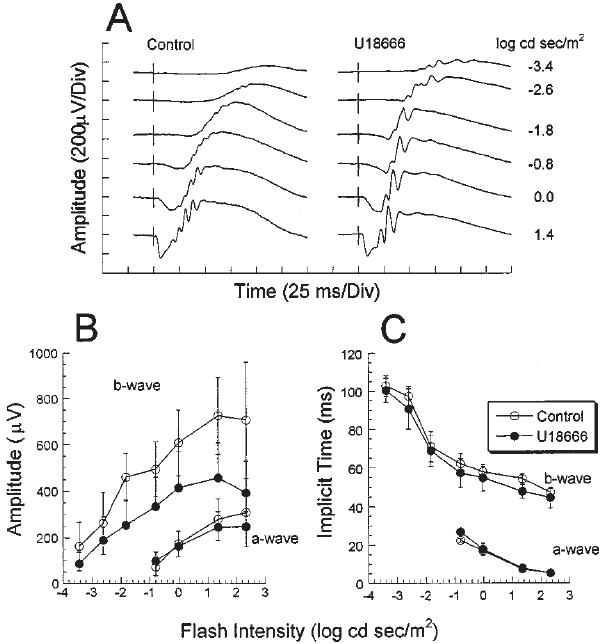

Electrophysiological Effects of U118666A Treatment

As shown in Fig. 7, a scotopic (dark-adapted) series of electroretinograms (ERGs) was obtained as a function of increasing light stimulus intensity (Fig. 7A) for both the treated and control groups of P28 rats (N = 4 each). U18666A treatment did not appear to cause any gross changes in ERG waveform and did not alter the manner in which the ERG response changes with stimulus intensity. In Fig. 7B, the response amplitudes of the major ERG components are plotted as a function of stimulus intensity. Although the b-wave response amplitudes in the treated group appear smaller than the corresponding control b-wave responses, ANOVA indicated there were no statistically significant amplitude differences between treated and control rats for either the a-wave (F(1,6) = 0.2) or the b-wave (F(1,6) = 4.6). As shown in Fig. 7C, no statistically significant differences were observed between the implicit times of ERG responses in treated and control rats for either the a-wave (F(1,6) = 3.4) or the b-wave (F(1,6) = 1.9). These data demonstrate that U18666A treatment did not compromise the electrophysiological competence of the retina, under the conditions employed.

Fig. 7.

Electroretinographic data from P28 control and U18666A-treated rats. (A) Dark-adapted electroretinograms (ERGs) from a representative control (left panel) and a treated rat (right panel). Flash intensities are given at the right-hand margin. (B) Intensity-response functions for a- and b-wave amplitudes from control (○) and treated rats (●). Data represent average value ± one standard deviation (N = 4). (C) ERG a- and b-wave implicit times, plotted as a function of stimulus intensity.

DISCUSSION

In the course of the present study, we have altered pharmacologically the sterol metabolism and steady-state sterol composition of the retina and other bodily tissues in rats, thereby creating an animal model that mimics the biochemical features of desmosterolosis. Remarkably, despite replacement of the majority of the cholesterol in the neural retina and its ros membranes with desmosterol, the histological organization, development, and electrophysiological function of the retina were comparable to those of normal, age-matched control animals. In contrast, the overall systemic physiology of the treated animals appeared compromised, since those animals exhibited reduced growth rates (lower body weight) and viability, and obvious tremors, compared to age-matched controls. Also, treated animals developed dense cataracts, indicative of gross alterations in the cytological organization of the lens, yet the alterations in lens sterol composition were similar to those seen in the retina. This latter finding suggests that, even within the eye, there are tissue-specific differences in the relative tolerance of a given tissue to marked alterations in steady-state sterol composition. The retina appears to be remarkably resilient to such metabolic and compositional changes, even under conditions where three out of four cholesterol molecules are replaced with desmosterol (as found in this study).

These results are fully consistent with our prior results obtained by treatment of neonatal rats during the first three weeks of life with U18666A (26), using a protocol originally shown to produce cataracts in rats (20). In that study, we found that postnatal retinal development, histological organization, cellular ultrastructure, rhodopsin biosynthesis, and ros membrane renewal rates were comparable to controls, even though approximately half of the cholesterol in the retina and ros membranes was replaced with desmosterol. In the present study, the exposure of the animals to U18666A during embryonic development as well as the additional postnatal week of drug exposure resulted in even more pronounced alterations in tissue sterol metabolism and composition changes. It also apparently resulted in decreased viability of the animals, since we observed 95–100% viability using the postnatal treatment protocol alone (at 15 mg/kg body wt.), whereas the combined prenatal-postnatal treatment protocol resulted in >80% mortality by the end of the fourth week of postnatal treatment. The apparent toxicity of U18666A also may be related to the generation of alternate, polar metabolites derived from squalene-2,3-epoxide, since it is well known that high concentrations of U18666A can inhibit oxidosqualene cyclase (17-19). While we did not observe the formation of squalene-2,3-epoxide (which would have eluted with a relative retention time of ca. 0.74 on this type of reverse-phase HPLC system (31)) or other relevant, identifiable polar components, the marked reduction in total sterols in affected tissues of U18666A-treated animals may indicate inhibition of an earlier enzymatic step in the de novo pathway prior to desmosterol reduction.

The results of the present study also are comparable to our recently published findings obtained with an animal model of the Smith-Lemli-Opitz syndrome (28). In that study, we employed a treatment protocol very similar to the one used in the present study; however, we substituted AY9944 (an inhibitor of 3β-hydroxysterol-Δ7-reductase (32,33), the affected enzyme in SLO (34-36)) for U18666A. Such treatment resulted in profound reductions in the steady-state levels of cholesterol and extraordinary elevation of 7-dehydrocholesterol (and other 7-dehydrosterols) in the retina and other tissues (replacing up to 80% of the cholesterol with 7-dehydrosterols), yet no appreciable abnormalities in retinal development, histological organization, ultrastructure, or electrophysiological function (with the minor exception of slightly delayed ERG implicit times) were observed (28).

Although retinal structure remains normal following treatment with either AY9944 (28) or U18666A (26), the functional consequences of these pharmacological regimens may be distinguished. Whereas response amplitudes were significantly increased following AY9944 treatment (28), in U18666A-treated rats the amplitude of the two major ERG components were either unchanged (a-wave) or reduced in amplitude (b-wave), when compared to controls (see Fig. 7). This difference is unlikely to be related to the smaller eye size found in U18666A-treated rats; in humans, eye size is inversely proportional to ERG amplitude, with smaller (hyperopic) eyes generating the largest responses (37,38). Assuming that this relationship applies to the rat eye, then U18666A-treated animals would generate abnormally large amplitude ERGs, which was not observed. With respect to response kinetics, while ERGs of U18666A-treated animals had normal implicit times, responses of AY9944-treated rats were slower than controls. In evaluating the AY9944 data, we suggested that the ERG changes might reflect an alteration in the deactivation kinetics of the G-protein mediated cascades that underlie the ERG a- and b-waves (28). While the mechanism underlying these ERG changes has not been identified, these ERG data indicate that the biochemical changes associated with cholesterol depletion by U18666A or AY9944 have different implications for response generation in the outer retina.

Notably, our animal model does not replicate the multiple phenotypic abnormalities associated with human desmosterolosis (10,11), despite the fact that comparable biochemical hallmarks were achieved pharmacologically. This may be a consequence of the fact that we waited six days into the gestational period before introducing the sterol-altering drug, and used a U18666A concentration that would not result in gestational or early neonatal death. Clearly, in the human disease, the recessive gene defect is expressed from the outset of embryogenesis, and stillbirth or early neonatal death is observed. Our goal in this study was to produce viable animals with profoundly altered retinal sterol composition that would develop to an age where ocular maturation (particularly of the photoreceptor cells) was nearly complete and electrophysiological function could be assessed with relative facility. That goal was achieved by judicious choice of the appropriate time window for drug exposure and the appropriate drug dosage. Prior studies have shown that these factors are critical to the teratogenic and lethal potential of various hypolipidemic drugs, particularly those that affect the de novo cholesterol pathway (3-6).

Our results suggest that desmosterol can replace cholesterol, both structurally and functionally, in the developing and early neonatal retina. One possible explanation for this may be “sterol synergism”—the ability of a sterol normally not present as a quantitatively significant component of a cell or tissue to supplement or act in concert with sub-threshold levels of the endogenous (“physiological”) sterol normally present, in order to promote and maintain normal biological structure and function. Sterol synergism has been observed widely in nature (39-45), most notably in microorganisms. In the present study, it is possible that the unusually high levels of desmosterol that accumulate in the retina in response to U18666A treatment can somehow compensate for the drastically reduced levels of cholesterol (the endogenous, physiological sterol), and that the two act together to fulfill the sterol requirements of retinal cells. In addition, it has been shown that such alterations in sterol composition can be accompanied by compensatory alterations in other aspects of lipid metabolism, resulting in changes in phospholipid class composition and/or fatty acid composition (42,44, 45). Presumably, this may represent the tendency of a cell or tissue to maintain what may be referred to as “fluidity homeostasis” in its membranes, thereby providing the optimal environment for functionality of membrane-associated receptors, enzymes, ion channels, and the like (46-52).

It is important to note that cholesterol only accounts for approximately 10 mol %, on average, of the total lipid in vertebrate retinas and their ros membranes (53), which is substantially lower than the level of cholesterol found in most other vertebrate tissues and plasma membranes (54,55). Thus, this relatively low level of cholesterol may be close to the threshold level necessary to support sterol-dependent biological functions in photoreceptors and other retinal cells. If true, one would expect that the retina would be even more sensitive than other tissues to any significant decrease in the level of cholesterol, unless there was some compensatory mechanism to preserve normal structure and function. Since the retina appears to exhibit a rather striking resilience to alterations in sterol composition, this is consistent with the hypothesis that alternate sterols, such as desmosterol, can replace cholesterol both structurally and functionally in the retina. The exact nature of cholesterol’s role in the retina remains to be determined, and is a focus of our continued research efforts.

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by U.S.P.H.S. grants EY07361 (SJF), EY02568 (RJC), and grants from the Department of Veterans Affairs (NSP). This publication is dedicated in honor of Prof. Nicolas G. Bazan, in recognition of his numerous, outstanding contributions to the fields of neuroscience, lipobiology, and vision research.

Footnotes

Special issue dedicated to Dr. Nicolas G. Bazan.

References

- 1.Fliesler SJ, Keller RK. Isoprenoid metabolism in the vertebrate retina. Int J Biochem Cell Biol. 1997;29:877–894. doi: 10.1016/s1357-2725(97)00018-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Cenedella RJ. Cholesterol and cataracts. Survey Ophthalmol. 1996;40:320–337. doi: 10.1016/s0039-6257(96)82007-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Roux C. Action teratogéne du triparanol chéz l’animal. Arch Franc Pediatr. 1964;21:451–464. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Roux C, Aubry M. Action teratogéne chez le rat d’un inhibiteur de la synthese due cholesterol, AY9944. Compt Rend Seances Soc Biol Filiales. 1966;160:1353–1357. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Barbu V, Roux C, Dupuis R, Gardette J, Maziere JC. Teratogenic effect of AY9944 in rats: importance of the day of administration and maternal plasma cholesterol level. Proc Soc Exp Biol Med. 1984;176:54–59. doi: 10.3181/00379727-176-41842. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Roux C, Horvath C, Dupuis R. Teratogenic action and embryo lethality of AY9944: Prevention by a hypercholesterolemia-provoking diet. Teratology. 1979;19:35–38. doi: 10.1002/tera.1420190106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Smith DW, Lemmli L, Opitz JM. A newly recognized syndrome of multiple congenital anomalies. J Pediatr. 1964;64:210–217. doi: 10.1016/s0022-3476(64)80264-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Tint GS, Batta AK, Xu G, Shefer S, Honda A, Irons M, Elias ER, Salen G. The Smith-Lemli-Opitz syndrome: a potentially fatal birth defect caused by a block in the last enzymatic step in cholesterol biosynthesis. In: Bittman R, editor. Subcellular Biochemistry. Vol. 28. Plenum Press; New York: 1997. pp. 117–144. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kelley RI. RSH/Smith-Lemli-Opitz syndrome: mutations and metabolic morphogenesis. Am J Hum Genet. 1998;63:322–326. doi: 10.1086/301987. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Clayton P, Mills K, Keeling J, FitzPatrick DR. Desmosterolosis: a new inborn error of cholesterol metabolism. Lancet. 1996;348:404. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(05)65020-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.FitzPatrick DR, Keeling JW, Evans MJ, Kan AE, Bell JE, Porteous MEM, Mills K, Winter RM, Clayton PT. Clinical phenotype of Desmosterolosis. Am J Med Genet. 1998;75:145–152. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Avigan J, Steinberg D, Vroman HE, Thompson MJ, Mossettig E. Studies of cholesterol biosynthesis. I. The identification of desmosterol in serum and tissues of animals and men treated with Mer-29. J Biol Chem. 1960;235:3123–3126. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Steinberg D, Avigan J. Studies on cholesterol biosynthesis. II. The role of desmosterol in the biosynthesis of cholesterol. J Biol Chem. 1960;235:3127–3129. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Fumagalli R, Grossi-Paoletti E, Paoletti P, Paoletti R. Lipids in brain tumours. II. Effect of triparanol and 20,25-diazacholesterol on sterol composition in experimental and human brain tumours. J Neurochem. 1966;13:1005–1010. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.1966.tb10298.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Suzuki K, Zagoren JC, Chen SM, Suzuki K. Effects of triparanol and 20,25-diazacholesterol in CNS of rat: morphological and biochemical studies. Acta Neuropathol (Berl) 1974;29:141–156. doi: 10.1007/BF00684773. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Phillips WA, Avigan J. Inhibition of cholesterol biosynthesis in the rat by 3β-(2-diethylamino-ethoxy)androst-5-en-17-one, hydrochloride. Prod Soc Exp Bio Med. 1963;112:233–236. doi: 10.3181/00379727-112-28003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Cenedella RJ. Concentration-dependent effects of AY-9944 and U18666A on sterol synthesis in brain. Biochem Pharmacol. 1980;29:2751–2754. doi: 10.1016/0006-2952(80)90006-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Sexton RC, Panini SR, Azran F, Rudney H. Effects of 3β-[2-(diethylamino) ethoxy]androst-5-en-17-one on the synthesis of cholesterol and ubiquinone in rat intestinal epithelial cell cultures. Biochemistry. 1983;22:5687–5692. doi: 10.1021/bi00294a001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Duriatti A, Bouvier-Nave P, Benveniste P, Schuber F, Delprino L, Balliano G, Cattel L. In vitro inhibition of animal and higher plants 2,3-oxidosqualene-sterol cyclases by 2-aza-2,3-dihydrosqualene and derivatives, and by other ammonium-containing molecules. Biochem Pharmacol. 1985;34:2765–2777. doi: 10.1016/0006-2952(85)90578-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Cenedella RJ, Bierkamper GG. Mechanism of cataract production by 3-β(2-diethylaminoethoxy)androst-5-en-17-one hydrochloride, U18666A: An inhibitor of cholesterol biosynthesis. Exp Eye Res. 1979;28:673–688. doi: 10.1016/0014-4835(79)90068-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Cenedella RJ. Source of cholesterol for the ocular lens, studied with U18666A: A cataract-producing inhibitor of lipid metabolism. Exp Eye Res. 1982;37:33–43. doi: 10.1016/0014-4835(83)90147-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bierkamper GG, Cenedella RJ. Induction of chronic epileptiform activity in the rat by an inhibitor of cholesterol biosynthesis, U18666A. Brain Res. 1978;150:343–351. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(78)90285-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.von Sallmann L. Triparanol-induced cataracts in rats. Trans Amer Ophthalmol Soc. 1963;61:49–60. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kirby TJ. Cataracts produced by triparanol. (MER-29) Trans Am Ophthalmol Soc. 1967;65:494–543. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Harris JE, Graber L. The reversal of triparanol-induced cataracts in the rat. Doc Ophthalmol. 1969;26:324–333. doi: 10.1007/BF00943994. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Fliesler SJ, Richards MJ, Miller C-Y, Cenedella RJ. Cholesterol synthesis in the vertebrate retina: Effects of U18666A on rat retinal structure, photoreceptor membrane assembly, and sterol metabolism and composition. Lipids. 2000;35:289–296. doi: 10.1007/s11745-000-0525-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Fliesler SJ, Florman R, Keller RK. Isoprenoid lipid metabolism in the retina: Dynamics of squalene and cholesterol incorporation and turnover in frog rod outer segment membranes. Exp Eye Res. 1995;60:57–69. doi: 10.1016/s0014-4835(05)80084-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Fliesler SJ, Richards MJ, Miller C-Y, Peachey NS. Marked alteration of sterol metabolism and composition without compromising retinal development or function. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 1999;40:1792–1801. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Carson F. Histotechnology- A Self Instruction Text. Chicago, IL: American Society for Clinical Pathologists Press; 1990. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Goto Y, Peachey NS, Ziroli NE, Seiple WH, Gryczan C, Pepperberg DR, Naash MI. Rod phototransduction in transgenic mice expressing a mutant opsin gene. J Opt Soc Amer A. 1996;13:577–585. doi: 10.1364/josaa.13.000577. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Fliesler SJ, Keller RK. Metabolism of [3H]farnesol to cholesterol and cholesterogenic intermediates in the living rat eye. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1995;210:695–702. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.1995.1715. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Dvornik D, Kraml M, Dubuc J, Givner M, Gaudry R. A novel mode of inhibition of cholesterol biosynthesis. J Am Chem Soc. 1963;85:3309. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Givner ML, Dvornik D. Agents affecting lipid metabolism-XV. Biochemical studies with the cholesterol biosynthesis inhibitor AY-9944 in young and mature rats. Biochem Pharmacol. 1965;14:611–619. doi: 10.1016/0006-2952(65)90233-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Irons M, Elias ER, Salen G, Tint GS, Batta AK. Defective cholesterol metabolism in Smith-Lemli-Opitz syndrome. Lancet. 1993;341:1414. doi: 10.1016/0140-6736(93)90983-n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Tint GS, Salen G, Batta AK, Shefer S, Irons M, Ampola M, Frieden R. Abnormal cholesterol and bile acid biosynthesis in an infant with a defect in 7-dehdrocholesterol (7-DHC)-Δ7 reductase. Gastroenterology (Abstract) 1993;104:A1008. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Tint GS, Irons M, Elias ER, Batta AK, Frieden R, Chen TS, Salen G. Defective cholesterol biosynthesis associated with the Smith-Lemli-Opitz syndrome. N Eng J Med. 1994;330:107–113. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199401133300205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Chen J-F, Elsner AE, Burns SA, Hansen RM, Lou PL, Kwong KK, Fulton AB. The effect of eye shape on retinal responses. Clin Vis Sci. 1992;6:521–530. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Pallin O. Influence of axial length of the eye on the size of the recorded b-potential in the clinical single-flash electroretinogram. Acta Ophthal (Suppl) 1969;47:1–57. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Dahl JS, Dahl CE, Bloch K. Sterols in membranes: Growth characteristics and membrane properties of Mycoplasma capricolum cultured on cholesterol and lanosterol. Biochemistry. 1980;19:1467–1472. doi: 10.1021/bi00548a032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Dahl JS, Dahl CE, Block K. Effect of cholesterol on macromolecular synthesis and fatty acid uptake by Mycoplasma capricolum. J Biol Chem. 1981;256:87–91. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Ramgopal M, Block K. Sterol synergism in yeast. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1983;80:712–715. doi: 10.1073/pnas.80.3.712. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Parks LW, Casey Wm. Physiological implications of sterol biosynthesis in yeast. Ann Rev Microbiol. 1995;49:95–116. doi: 10.1146/annurev.mi.49.100195.000523. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Whitaker BD, Nelson DL. Sterol synergism in Paramecium tetraurelia. J Gen Microbiol. 1988;134:1441–1447. doi: 10.1099/00221287-134-6-1441. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Rujanavech C, Silbert DF. LM cell growth and membrane lipid adaptation to sterol structure. J Biol Chem. 1986;261:7196–7203. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Baldassare JJ, Saito Y, Silbert DF. Effect of sterol depletion on LM cell sterol mutants. Changes in the lipid composition of the plasma membrane and their effects on 3-O-methyl glucose transport. J Biol Chem. 1979;254:1108–1113. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Yeagle PL. Role of cholesterol in cellular functions. In: Esfahani M, Swaney JB, editors. Advances in Cholesterol Research. The Telford Press; New Jersey: 1990. pp. 111–132. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Bastiaanse EM, Hold KM, Van der Laarse A. The effects of membrane cholesterol on ion transport in plasma membranes. Cardiovasc Res. 1997;33:272–283. doi: 10.1016/s0008-6363(96)00193-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.LeGrimellec C, Friedlander G, el Yandouzi EH, Zlatkine P, Giocondi MC. Membrane fluidity and transport properties in epithelia. Kidney Intl. 1992;42:825–836. doi: 10.1038/ki.1992.357. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Lenaz G. Lipid fluidity and membrane protein dynamics. Bio Sci Rep. 1987;7:823–837. doi: 10.1007/BF01119473. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Demel RA, Bruckdorfer KR, van Deenen LLM. The effect of sterol structure on the permeability of liposomes to glucose, glycerol, and Rb+ Biochim Biophys Acta. 1972;255:321–330. doi: 10.1016/0005-2736(72)90031-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Vemuri R, Philipson KD. Influence of sterols and phospholipids on sarcolemmal and sarcoplasmic reticular cation transporters. J Biol Chem. 1989;264:8680–8685. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Nes WR, Sekula BC, Nes WD, Adler JH. The functional importance of structural features of ergosterol in yeast. J Biol Chem. 1978;253:6218–6225. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Fliesler SJ, Anderson RE. Chemistry and metabolism of lipids in the vertebrate retina. Progr Lipid Res. 1983;22:79–131. doi: 10.1016/0163-7827(83)90004-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Bloch K. Sterol structure and membrane function. Crit Rev Biochem. 1983;14:47–92. doi: 10.3109/10409238309102790. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Yeagle PL. Cholesterol and the cell membrane. In: Yeagle PL, editor. Biology of Cholesterol. CRC Press; Boca Raton: 1988. pp. 121–145. [Google Scholar]