Abstract

Nanoparticles have become more and more prevalent in reports of novel contrast agents, especially for molecular imaging, the detection of cellular processes. The advantages of nanoparticles include their potency to generate contrast, the ease of integrating multiple properties, lengthy circulation times and the possibility to include high payloads. As the chemistry of nanoparticles has improved over the past years more sophisticated examples of nano-sized contrast agents have been reported, such as paramagnetic, macrophage targeted quantum dots or αvβ3-targeted, MRI visible microemulsions that also carry a drug to suppress angiogenesis. The use of these particles is producing greater knowledge of disease processes and the effects of therapy. Along with their excellent properties, nanoparticles may produce significant toxicity, which must be minimized for (clinical) application. In this review we discuss the different factors that are considered when designing a nanoparticle probe and highlight some of the most advanced examples.

Keywords: Nanotechnology, molecular imaging, magnetic resonance imaging, drug delivery, gene therapy

Introduction

One of the main current focuses of research in medical diagnostics is molecular imaging, as described in an accompanying article in this issue by Choudhury et al. Molecular imaging can facilitate early diagnosis, identify the stage of disease, provide fundamental information on pathological processes and can be applied to follow the efficacy of therapy. Molecular imaging heavily relies on the development of sophisticated probes needed to detect biological processes on the cellular and molecular level.1–5 Nanoparticulate probes have shown noteworthy advantages over single molecule-based contrast agents. These advantages include producing excellent contrast (e.g. quantum dots6), integrating multiple properties such as several types of contrast generating materials,7 lengthy circulation time8, 9 and the possibility to include high payloads.10 Importantly, nanoparticles allow the components of a molecular imaging contrast agent to be easily assembled in an efficient ratio. As a result, very exciting molecular imaging results are being reported, such as agents that can be detected by multiple imaging techniques,7 agents that also deliver therapeutics,11 agents that detect particular cell types12 or agents that allow new imaging systems to be developed.3, 13 Other articles in this issue will expound upon the progress that has been made by applying nanoparticles for molecular imaging in cardiovascular disease; we will confine our discussion to nanoparticle design.

The design of effective nanoparticle contrast agents for molecular imaging requires careful consideration of the properties required for the application in question. Once the required properties have been established, candidate nanoparticle platforms may be identified. The particle synthesis can then be optimized to generate an assembly with the appropriate contrast/therapeutics included, optimized surface coating, targeting properties, defined size and a high degree of biocompatibility. In this review we will first discuss the current state of the art in nanoparticle contrast agent design and give some examples of agents whose design is very advanced. This is followed by a discussion about the available options and factors influencing nanoparticle design.

State of the art nanoparticle contrast agent design

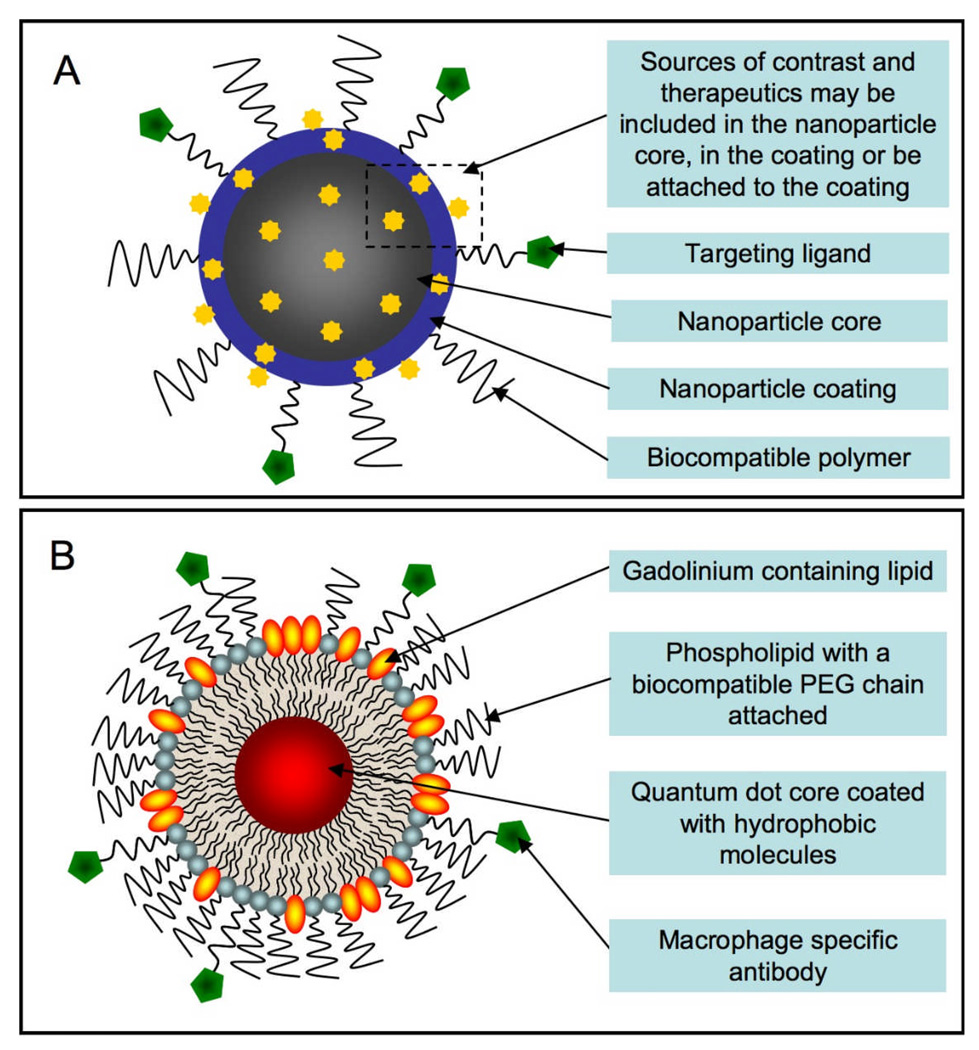

The latest designs of nanoparticulate molecular imaging contrast agents incorporate the appropriate contrast generating materials (e.g. fluorescent, radioactive, paramagnetic, superparamagnetic or electron dense), targeting groups, a biocompatible coating and the possibility for other functionalities such as a therapeutic.2 A schematic of a generalized nanoparticle is shown in Figure 1A. Sources of contrast enhancing materials or therapeutics can be included in the particle core, within the coating or attached to the surface. This flexibility allows the inclusion of multiple types of contrast agents or a combination of contrast and therapeutic agents. This is an especially important feature for pre-clinical contrast agents so that they can be detected with a clinical imaging modality (e.g. MRI) and fluorescence techniques to confirm the localization of the agent in the target tissues or cell types. The combination of contrast and therapeutic agents is known as ‘theranostics’14 and is attractive as it allows imaging of drug, protein or gene delivery. An important aspect of nanoparticles is that multiple properties can be easily integrated at the desired ratios of contrast and/or therapeutic agents, fluorescence and targeting groups.

Figure 1.

A Generalized schematic of a nanoparticle-based molecular imaging contrast agent. B Schematic of a quantum dot based paramagnetic contrast agent targeted to macrophages via CD204 antibodies.

Mulder et al recently reported a multifunctional nanoparticle for the imaging of macrophages in atherosclerosis.15 This agent is comprised of a micellular coating that encloses a quantum dot core, as depicted in Figure 1B. The micelle is formed around the quantum dot by hydrating a mixed film that contains quantum dots, polyethylene glycol (PEG) modified phospholipids, gadolinium labeled lipids (for MRI contrast) and a PEG-phospholipid that has a reactive group to enable functionalization. The relative proportions of gadolinium to fluorophore to targeting moiety can be controlled by the lipid/amphiphile inputs; these properties are combined in the particle in only two steps, which is followed by a single purification step. This methodology is much simpler and more efficient than a multi-step synthesis of one molecule that contains the targeting group, contrast agent and fluorophore.

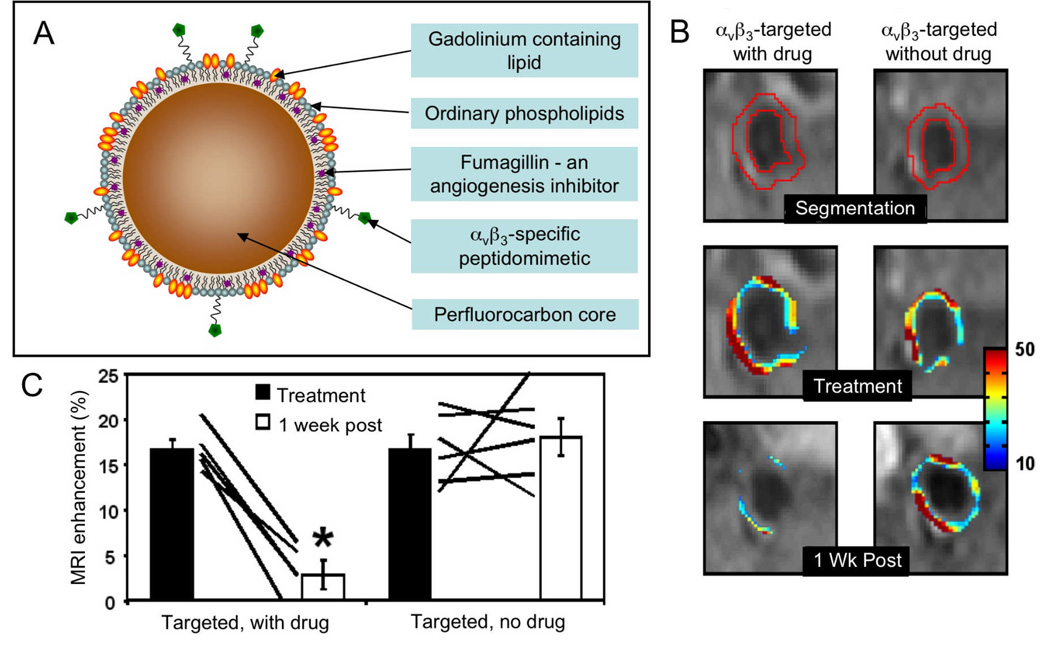

A team from Washington University has extensively investigated perfluorocarbon based microemulsions as contrast agents targeted to atherosclerotic plaque components such as αvβ3-integrin,11, 16 fibrin17 or collagen III.18 The perfluorocarbon core allows ‘hotspot’ MR imaging using systems tuned to the 19F nucleus19, 20 and the inclusion of hydrophobic drugs. In this highlighted example, the anti-angiogenesis drug fumagillin was included in the particle, along with gadolinium chelates in the phospholipid coating in order to provide contrast for conventional MRI (Figure 2A).11 The particle was targeted using a peptidomimetic specific for the αvβ3-integrin, which is overexpressed in angiogenesis. In a theranostic approach, the authors applied the agent twice to a rabbit model of atherosclerosis in which angiogenesis is pronounced in the adventitia of the arteries. When MR images were acquired 4 hours after the first injection there was a significant increase in the intensity of the aorta due to accumulation of the contrast agent, while after the second injection, one week later, the increase in intensity of the aorta was scant (Figure 2B and C). This effect was ascribed to the anti-angiogenic effect of the fumagillin delivered in the first injection, hence reducing microvessel density and therefore accumulation of the agent after the second microemulsion application.

Figure 2.

A schematic depiction of a microemulsion based contrast agent/drug delivery nanoparticle. B MR images of the aortas of hyperlipidemic rabbits injected with the microemulsion contrast agent with or without the anti-angiogenesis drug fumagillin. The superimposed color maps denote the percent signal enhancement in the aorta. C quantification of enhancement upon agent injection pre and one week post-treatment showing reduction of angiogenesis when the drug was included in the particle. Parts of this figure reproduced, with permission, from reference 11.

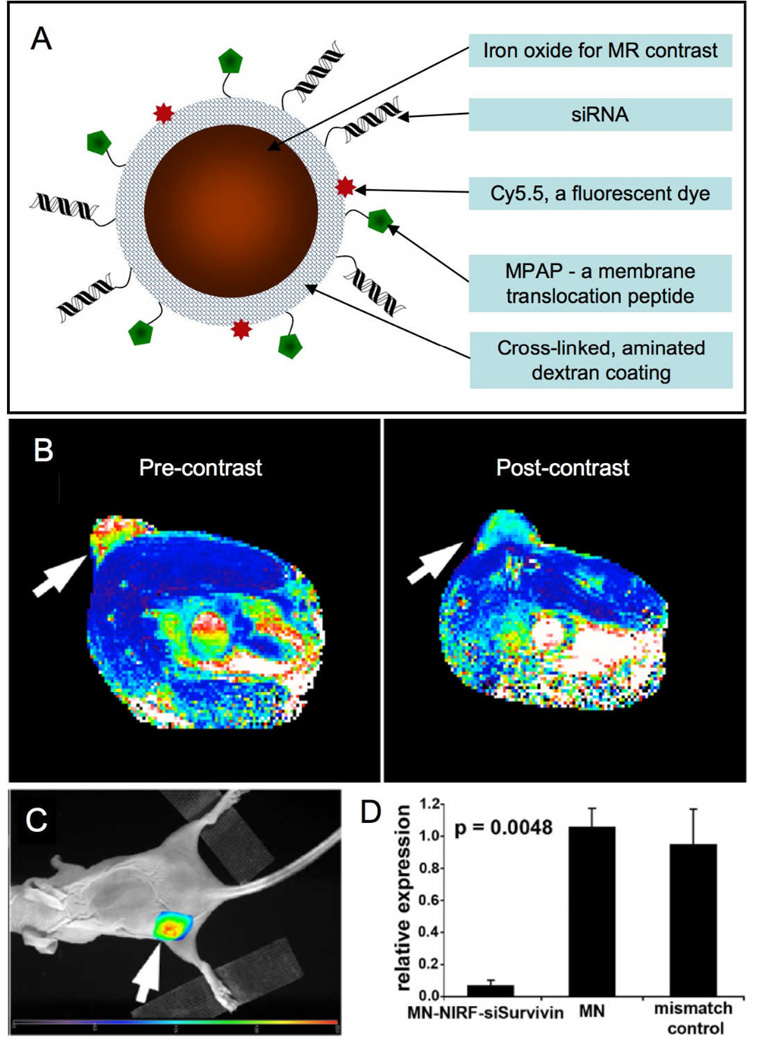

Iron oxide nanoparticles are sensitive contrast agents for MRI. A highly sophisticated iron oxide particle has recently been reported to knock out gene expression for therapeutic intervention.21 The nanoparticle has a cross-linked aminated dextran shell, to which was first attached the near-infrared dye Cy5.5, then the membrane translocation myristoylated polyarginine peptide (MPAP), and lastly siRNA for gene silencing (Figure 3A). The particle design allows its detection by both MR and fluorescence techniques, enables efficient uptake by cells and can silence specific genes. In initial experiments, the siRNA used was antisense to green fluorescence protein (GFP). Mice were inoculated with two tumors, one expressing GFP, the other red flurorescent protein (RFP). Uptake of the particle in these tumors was established by MR and fluorescence methods both in vitro and in vivo. Fluorescence imaging revealed that expression of GFP was knocked down by the siRNA-iron oxide particle by as much as 85%, while red fluorescent protein expression remained unaffected. Furthermore, a therapeutic version of the particle was created where the siRNA attached was antisense to survivin, an inhibitor of apoptosis proteins. In this case also, nanoparticle uptake was established using MR and fluorescence imaging performed 24 hrs post administration of the agent (Figure 3B and C). After four injections of the agent over two weeks, survivin levels in the tumors of these mice were knocked down to 3% of the levels in control animals (Figure 3D). In addition, apoptosis and necrosis was increased in the tumors of treated mice, as found via immunofluorescence and histology, hence this iron oxide-siRNA agent is an effective therapeutic for cancer.

Figure 3.

A Schematic depiction of an iron oxide based MR contrast agent that can deliver siRNA. B MR image of a mouse pre- and 24 hrs post-administration of the agent. Change in pixel color in the tumor (arrow) from red-yellow to blue indicates accumulation of the agent. C Fluorescence image of the mouse with emission seen from the tumor (arrow), also indicating agent accumulation. D Silencing of the Birc5 gene by the siRNA labeled nanoparticle (MN-NIRF-siSurvivin) reduces Survivin expression in the tumor and leads to apoptosis in this tissue. Parts of this figure reproduced, with permission, from reference 21.

Aspects of nanoparticle contrast agent design

Nanoparticle selection

A wide range of nanoparticles has been proposed for use as contrast agents with each imaging modality requiring nanoparticles of different properties for contrast production. In this section we will briefly describe the nanoparticles that have been applied for each modality.

Gadolinium-labeled nanoparticles such as liposomes,22 micelles,12 microemulsions,23 lipoproteins,24 viruses25 and carbon nanotubes26 are suitable for providing contrast for T1-weighted MRI via the paramagnetism of this element. Superparamagnetic iron oxides have been widely exploited to induce contrast for T2(*)-weighted MRI.1 As both types of MRI can be carried out using any MRI system, one can choose between iron or gadolinium as the basis of contrast, depending on the application. While the sensitivity of detection of gadolinium chelate enriched nanoparticles is generally lower than that of iron oxide nanoparticles,27 gadolinium produces positive contrast that is easy to assign to agent accumulation in that tissue. Iron oxides induce negative contrast or signal loss and since there are many sources of signal loss in MR images other than iron oxide accumulation, it may be hard to ascribe signal loss to the iron contrast agent with certainty. New image acquisition sequences that produce positive contrast from iron oxides may mitigate this difficulty.28, 29 There are several factors to weigh when deciding whether to use iron oxides or gadolinium based nanoparticles. For example, if the target to be imaged is expressed in very low concentrations, the sensitivity of iron oxide is very useful. Iron oxides are also well suited for imaging in tissues that produce homogenous MRI signals and have predictable structures, such as the brain.30 In regions of the body where the structure is less predictable and signal voids commonly occur, such as the abdomen, gadolinium based agents have an advantage as they produce positive contrast.

Quantum dots provide excellent contrast for fluorescent imaging. They have wide excitation windows,31 narrow emission windows,32 they fluoresce with high efficiency6 and are not prone to photobleaching.33 When applying fluorescent labels to other kinds of nanoparticles, using fluorophores that both absorb and emit light in the near-infrared window (650–900 nm), where the absorbance of tissue is low, is advocated.34 This is important for fluorescence tomography, where light has to pass through substantial tissue thickness, but not important if the application is confocal microscopy, for example, as light only has to penetrate tissue sections around 10 µm thick.

The nanoparticles that have been proposed as CT contrast agents tend to be based on electron dense and high atomic number elements such as iodine,35 bismuth36 or gold.37 Since contrast in computed tomography requires high payloads of such elements to be delivered, most researchers have based their agents on solid nanoparticles, but some have proposed liposomes in whose aqueous interior iodinated molecules are trapped.38 Gold nanoparticles are becoming a popular choice for CT,39 although it is unclear as yet whether this is the optimal material to use; other elements have superior X-ray attenuation at clinical energies.40 Recently Hyafil et al reported a solid, iodine-based nanoparticle that was specifically taken up by macrophages in a rabbit model of atherosclerosis.35 This report demonstrated the possibility of molecular imaging in vivo using CT, an application for which CT had been thought to be too insensitive.41

Ultrasound requires contrast agents that provide backscatter of sound waves to the scanner head. This is normally achieved using micron-sized bubbles (and hence not technically nanoparticles) of a water insoluble gas such as decafluorobutane.42 The bubbles require coatings to make them stable, but coatings that produce excellent stability reduce the particle flexibility needed to yield good contrast. As a consequence, the coatings currently used often compromise between stability and flexibility.43 Multi-layer vesicles have also been used as ultrasound contrast agents, although it has been shown that the echogenic response they generate may be due to entrapped gas pockets.44 In addition, microemulsions have been reported to act as ultrasound contrast agents.45

Conceptually, it is possible to include drugs in any nanoparticle, as drugs may be attached to surfaces, incorporated in coatings or stowed in cores. It is worth noting the hydrophobic/hydrophilic nature of the drug, however, when making the choice of nanoparticle for drug delivery. Hydrophobic drugs are more easily and more stably incorporated into nanoparticles with a hydrophobic compartment, than those without11 and the corresponding concept holds true for hydrophilic drugs.46

Coating types

A lot of functionally active materials used to generate contrast for molecular imaging have a very low biocompatibility, which leads to fast excretion, low circulating half-life, decreased stability and potential toxicity. Therefore great efforts have been undertaken to render these materials bioapplicable. A variety of different approaches have been reported, using materials such as phospholipids,27 dextran,47 polyvinylpyrrolidone,48 polyethylene glycol (PEG)49 or silica as coatings.50 Furthermore, it is now common practice to incorporate additional functional labels in the coating corona, rendering the nanoparticles multimodal.2 These coatings increase the hydrophilicity of nanoparticles, thereby decreasing aggregation, but as well as this improvement in physical properties there are beneficial biological effects as well. By coating nanoparticles that are otherwise foreign to the body, considerably enhanced blood half-lives are produced, by avoiding opsonization and ‘fooling’ the defence mechanism of the body to some extent.

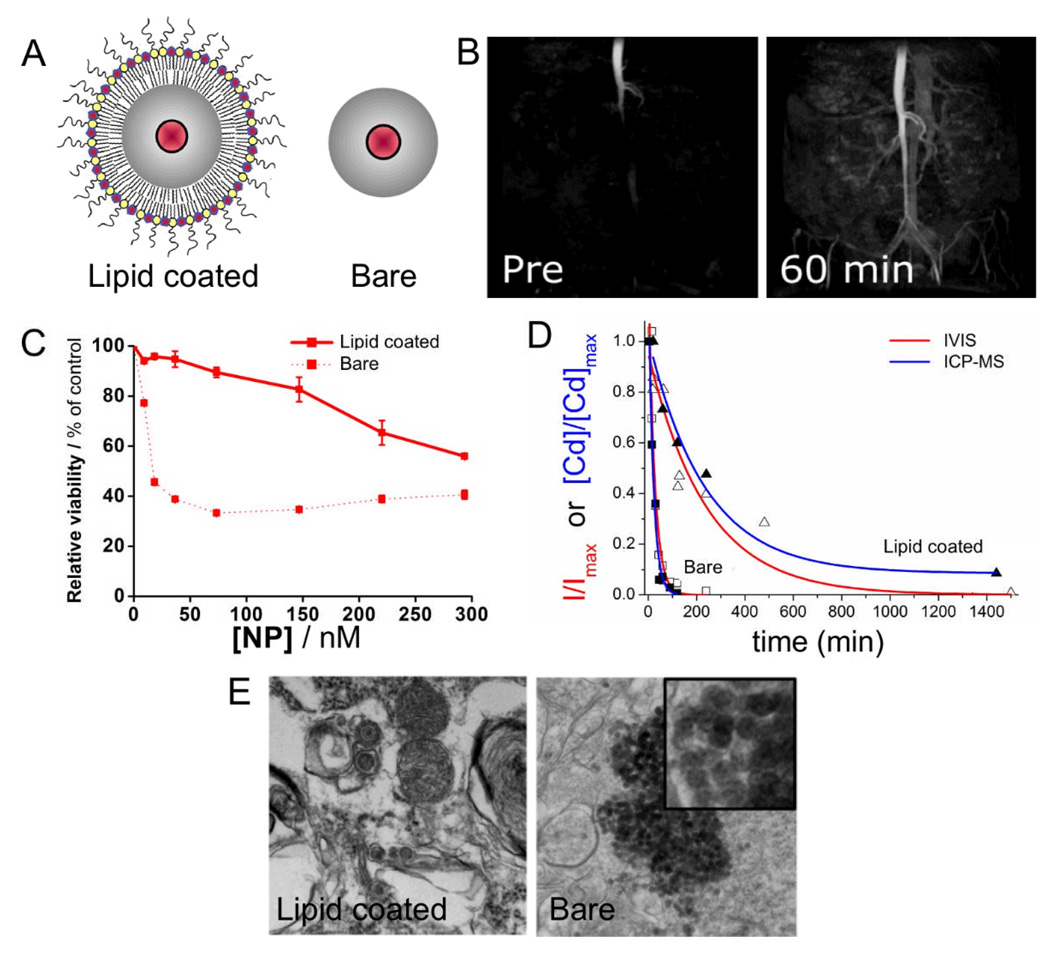

PEGylation has been very widely used as a coating strategy for nanoparticles to enhance their circulation half-life by avoiding fast removal by the reticuloendothelial system.9, 51 Such prolonged circulation half-lives can be advantageous as they allow an increased amount of the injected material to reach and bind the desired sites. Silica has been used as a nanoparticle delivery platform for a variety of cargoes such as drugs,52 genes,53 proteins54 or contrast generating materials.50 Recently it has been shown by van Schooneveld et al. how quantum dot-containing silica particles can be coated with PEGylated lipids to improve their biocompatibility, as compared to silica particles with unmodified surfaces (Figure 4A).55 The lipid-coated particles had paramagnetic lipids included in this coating as well and hence could be used to visualize the vasculature (Figure 4B). These lipid-coated particles displayed lower cytotoxicity, exhibited a 10-fold increase in circulation half-life and did not form aggregates in the lungs (Figure 4C–E). In summary, the lipid-coating caused a spectacular improvement in short term biocompatibility, however it remains to be investigated how silica is metabolized and excreted from the body over longer periods.

Figure 4.

A Schematic depictions of lipid-coated and bare silica particles that have a quantum dot in their cores. B MRI of the vasculature of a mouse before and after administration of the paramagnetic, PEG-lipid coated silica particles. C Cell viability assays indicating lowered cytotoxicity of the lipid-coated particles. D Blood clearance profiles of the silica particles showing the enhanced circulation half-life of the coated particles. E Transmission electron micrographs of mouse lungs after injection with silica particles. Large aggregates of the particles were found in the lungs of mice injected with bare particles. The images in this figure are reproduced, with permission, from reference 55.

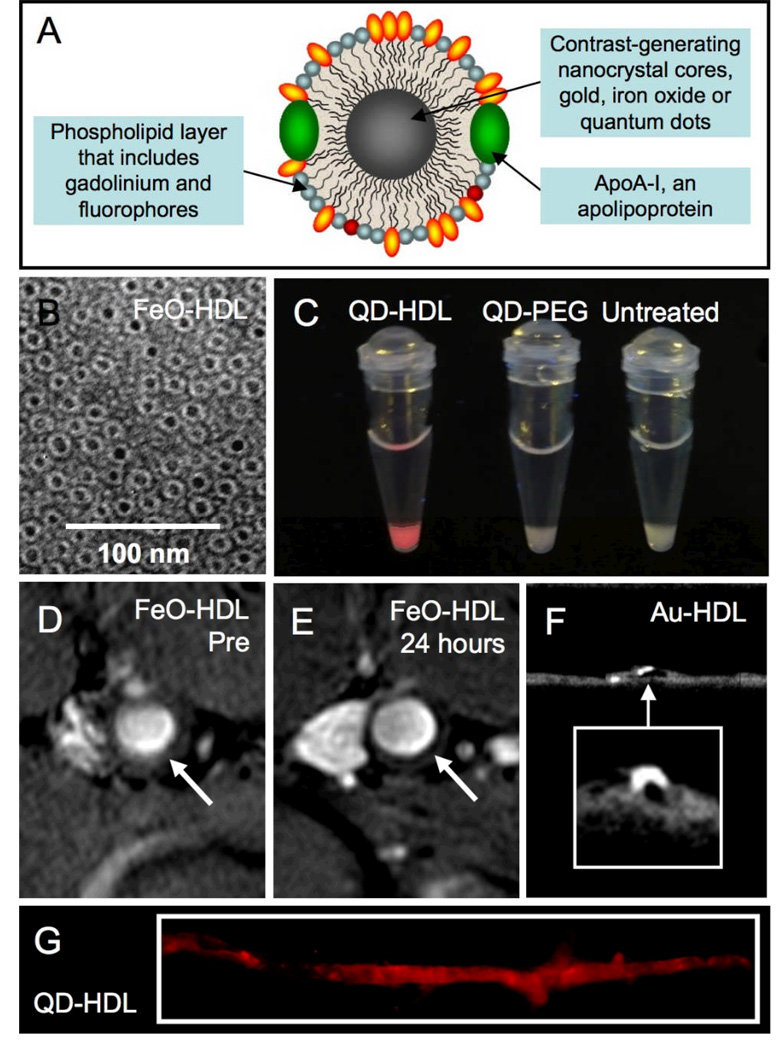

An alternative strategy to synthetic coatings is the use of natural nanoparticles such as viruses or lipoproteins thereby evading recognition by the body’s defense systems. To this aim, two routes have been pursued. Firstly, the exterior/surface of the natural nanoparticle can be modified to contain contrast generating ions and dyes.25, 56 The second approach forms novel blends of inorganic and natural materials by including inorganic nanoparticles in the core of the virus or lipoprotein.57–59 The latter approach was recently exemplified by a study by Cormode et al, where iron oxides, quantum dots or gold nanoparticles were incorporated into HDL (Figure 5A), as shown by negative stain transmission electron microscopy (TEM) in Figure 5B.59 The iron oxide, quantum dot and gold HDL nanoparticles were termed FeO-HDL, QD-HDL and Au-HDL, respectively. Paramagnetic and/or fluorescent phospholipids were incorporated into the particles so that each particle provided contrast for MRI and fluorescence techniques, as well as for CT in the case of Au-HDL. These particles were shown to be taken up by macrophage cells in vitro and in a mouse model of atherosclerosis with MRI, fluorescence imaging and computed tomography (Figure 5C–G).

Figure 5.

A Schematic depiction of nanocrystal-core high density lipoprotein (HDL). B Negative stain TEM of FeO-HDL. C Photograph of pellets of cells incubated with QD-HDL, QD-PEG or without a contrast agent taken under UV irradiation. MR images of the aorta of an apoE KO mouse taken D before and E 24 hours after injection of FeO-HDL. F Micro-CT image of an excised aorta of a mouse injected 24 hours previously with Au-HDL. G Fluorescence image of an excised aorta of a mouse injected 24 hours previously with QD-HDL. Parts of this figure reproduced, with permission, from reference 59.

Targeting strategies

There are numerous methods of targeting nanoparticles. In tissues where there is significant angiogenesis, such as in cancer and inflammatory diseases like atherosclerosis,60 the consequent leaky and chaotic vasculature results in an increased accumulation of particles with a long circulation half-life due to the enhanced permeability and retention (EPR) effect.22, 61 Therefore, in cases when angiogenic tissues are the pathologies of interest no targeting ligands are required, but it must be ensured that the nanoparticle coating engenders a long blood half-life. Another passive form of targeting utilizes dextran as the particle coating. Iron oxide nanoparticles coated with dextran are avidly taken up by macrophages.62 Several different types of molecules can be attached to nanoparticles to yield active targeting, including antibodies,12 antibody fragments,63 proteins,27, 64 peptides,65 peptidomimetics,11 aptamers66, sugars67 and small molecules.68 It is important that the targeting ligand exhibits a high degree of specificity, but there are other factors to consider as well. For example, although antibodies are very specific, they are expensive and their attachment may increase the size of the particle by as much as 10 nm.69 Furthermore, antibodies are species specific and may generate immunological responses. Smaller ligands can also be specific, are cheaper, but may not be available for the target in question. Consequently, phage display has been a boon to the field by identifying short peptidic sequences for specific targeting.65 Furthermore, techniques such as that reported by Weissleder et al, where a large library of small molecule-targeted nanoparticles were screened against several cell types, are useful for identifying cheap, simple targeting ligands.70 After identifying the appropriate ligand its linkage with the nanoparticle has to be taken into consideration. The biotin-streptavidin linkage has been frequently exploited,71 but gives immunogenic responses in patients.72 To avoid this immunogenic response, ligands may be covalently attached to nanoparticles using a variety of methods.73

Effect of size

Nanoparticle size plays a critical role for a number of aspects, including the cell types that can be targeted, payload, clearance/excretion and the strength/quality of contrast produced. The size of nanoparticles has a considerable impact on the biodistribution of the particles and thus plays a prominent role in the ability to target different cells. Inflamed pathological tissues that possess highly permeable vasculature, such as tumors or atherosclerotic plaques, can be infiltrated by nanoparticles. This infiltration is more likely if the nanoparticles are small.

The size range of nanoparticles is determined by the components used for synthesis and considerable efforts have been devoted to developing procedures that produce particles of a defined size. As a consequence the size and shape of inorganic nanocrystals such as iron oxide, gold nanoparticles, silica or quantum dots as well as lipid-based nanoparticles can now be precisely controlled.74–77 Nevertheless, the total diameter of a particle using the same core can widely differ depending on the coating used.

Furthermore, the sizes of nanoparticles are important in the excretion of the particles form the body. Choi et al showed recently that there is a cut-off point in which nanoparticles are cleared from the body via the renal system.78 With fluorescence techniques the authors showed that nanoparticles equal or smaller than 5.5 nm are excreted through the renal system, while particles larger than that are mainly taken up by the reticuloendothelial system where they end up in the liver and spleen. Here they are metabolized and excreted or they accumulate, and potentially become toxic for the body. On the other hand, if particles are small enough to be renally excreted, their half-life is reduced.

Altering the size of nanoparticles may tune the contrast they generate. For example, the fluorescent emission of quantum dots (QDs) increases in wavelength with increasing size.79 Therefore the emission of these particles can be tuned to the desired wavelength by control of the size synthesized. Iron oxide particles give excellent contrast for MRI in a very wide size range (1 nm-1 µm),27, 80 but are only useful as contrast agents in the nascent magnetic particle imaging (MPI) technique when larger than 20 nm.81 Larger particles can carry high payloads, which may be advantageous.

As we have now discussed, size has an impact on biodistribution, clearance and contrast produced. An important question scientists face is, therefore, how to determine the size of their particles.82 Many different techniques are currently available, but proper use of them is critical, since each of the techniques return different information. For example, transmission electron microscopy will give the diameter of inorganic cores, but often not the coating, scanning electron microscopy will return the diameter including the coating, while dynamic light scattering gives the hydrodynamic diameter. However, the hydrodynamic diameter will vary depending on the concentration of the sample and the buffer used.

Synthetic strategies

It is advantageous to be able to synthesize and coat (with a biocompatible material) nanoparticles in a one step, aqueous process, as the United States Food and Drug Administration (USFDA) approval process is easier in this case. The type of coating in these situations is normally a water-soluble polymer. Nanoparticles such as liposomes or micelles do not need a coating to be applied, as they are largely biocompatible as is. Organic phase syntheses of solid nanoparticles lead to better control of the size and hence contrast properties, in many cases.74, 79, 83 Nanoparticles synthesized in the organic phase are usually insoluble in water and require a second coating step to render them bioapplicable. Fortunately, there are several efficient methods for doing this, normally using amphiphilic polymers or molecules such as phospholipids.55, 84, 85

Another crucial consideration prior to synthesis is how additional functionalities such as targeting groups or fluorophores will be attached to the surface. In the case of cross-linked iron oxides, the dextran coating of these particles is modified with amine groups,86 which can then be conjugated with targeting groups, fluorophores or chelates for metal ions.7 In the example featured before, where there is a quantum dot at the core of a micelle (Figure 1B), the biocompatible phospholipid/PEG coating is self-assembled around the nanoparticle. In order to attach targeting moieties using this type of strategy, a small amount of a phospholipid with a reactive functionality is included. In that particular example maleimide was used,15 but various others are available, such as amines, carboxylic acids, pyridyl dithiopropionate (PDP) and biotin.

Minimizing toxicity

Nanoparticles are subject to the normal strictures with regards to toxicity as other drugs or contrast agents applied to humans. There may eventually be additional restrictions on their use, however, as larger particles will remain in the body, primarily in the liver and spleen.55 How these particles break down and how the body reacts to them will determine if they can eventually be used in humans. The fact that the USFDA has not issued guidelines or standards for nanoparticles,87 despite calls for it to do so,88 is further complicating the picture. Nevertheless, impressive efforts are being made to determine the type of interactions nanoparticles will have in the body.89 For example, Shaw et al used an array of 64 in vitro assays to elucidate the effect of nanoparticles on a variety of cellular processes.90

Certain nanoparticles break down into non-toxic materials and thus can be considered safe. Iron oxide particles are injected at a dose of iron that, if injected as free ions, would be toxic due to the body’s limited ability to process iron. As the iron oxide is injected in a crystalline form it is non-toxic and breaks down slowly to release iron ions at a rate that is manageable.1 Another option is that the injected material will not break down, which could be the case for gold nanoparticles as that element is quite inert. If the particles break down into highly toxic substances, as is the case for quantum dots (which release cadmium), it is unlikely they can seriously be considered for clinical use.91 Particles such as these are very useful in preclinical settings, however.

Conclusions

Extremely effective molecular imaging contrast agents can be synthesized using nanoparticles as their basis. The design of these probes has improved significantly over the past decade, with multifunctionality, more efficient targeting, better biocompatibility and agents suited to each available imaging modality being among these improvements. At the current stage of development, generally speaking, a nanoparticle contrast agent possessing the required attributes can be synthesized for any desired application. However there is scope for significant enhancements in biocompatibility, efficacy, specificity and detection of further disease targets. Furthermore, standardized nanoparticle platforms that can be used for preclinical/clinical disease investigations need to be developed. Lastly, nanotechnology will continue to produce new particles that possess novel and interesting properties and will be exploited in medical imaging, as will medical imaging continue to be developed, requiring new nanoparticle formulations as contrast agents.

Acknowledgements

We thank the Danish Heart Association for studentship 07-10-A1655-22406 (TS).

References

- 1.Corot C, Robert P, Idee J-M, Port M. Recent advances in iron oxide nanocrystal technology for medical imaging. Adv. Drug Deliv. Rev. 2006;58:1471–1504. doi: 10.1016/j.addr.2006.09.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Mulder WJM, Griffioen AW, Strijkers GJ, Cormode DP, Nicolay K, Fayad ZA. Magnetic and fluorescent nanoparticles for multimodality imaging. Nanomedicine. 2007;2:307–324. doi: 10.2217/17435889.2.3.307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Huang X, Jain PK, El-Sayed IH, El-Sayed M. Gold nanoparticles: interesting optical properties and recent applications in cancer diagnostics and therapy. Nanomedicine. 2007;2:681–693. doi: 10.2217/17435889.2.5.681. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Azzazy HME, Mansour MMH, Kazmierczak SC. From diagnostics to therapy: Prospects of quantum dots. Clin. Biochem. 2007;40:917–927. doi: 10.1016/j.clinbiochem.2007.05.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wickline SA, Neubauer AM, Winter PM, Caruthers SD, Lanza GM. Molecular imaging and therapy of atherosclerosis with targeted nanoparticles. J. Magn. Reson. Imaging. 2007;25:667–680. doi: 10.1002/jmri.20866. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Medintz IL, Uyeda HT, Goldman ER, Mattoussi H. Quantum dot bioconjugates for imaging, labelling and sensing. Nat. Mater. 2005;4:435–446. doi: 10.1038/nmat1390. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Nahrendorf M, Zhang H, Hembrador S, Panizzi P, Sosnovik DE, Aikawa E, Libby P, Swirski FK, Weissleder R. Nanoparticle PET-CT imaging of macrophages in inflammatory atherosclerosis. Circulation. 2008;117:379–387. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.107.741181. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Klibanov AL, Maruyama K, Torchilin VP, Huang L. Amphipatic polyethyleneglycols effectively prolong the circulation time of liposomes. FEBS Lett. 1990;268:235–238. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(90)81016-h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Allen TM, Hansen C, Martin F, Redemann C, Yau-Young A. Liposomes containing synthetic lipid derivatives of poly(ethylene glycol) show prolonged circulation half-lives in vivo. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 1991;1066:29–36. doi: 10.1016/0005-2736(91)90246-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Schmieder AH, Winter PM, Caruthers SD, Harris TD, Williams TA, Allen JS, Lacy EK, Zhang HY, Scott MJ, Hu G, Robertson JD, Wickline SA, Lanza GM. Molecular MR imaging of melanoma angiogenesis with alpha(nu)beta(3)-targeted paramagnetic nanoparticles. Magn. Res. Med. 2005;53:621–627. doi: 10.1002/mrm.20391. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Winter PM, Neubauer AM, Caruthers SD, Harris TD, Robertson JD, Williams TA, Schmieder AH, Hu G, Allen JS, Lacy EK, Zhang HY, Wickline SA, Lanza GM. Endothelial alpha(v)beta(3) integrin-targeted fumagillin nanoparticles inhibit angiogenesis in atherosclerosis. Arterioscler. Thromb. Vasc. Biol. 2006;26:2103–2109. doi: 10.1161/01.ATV.0000235724.11299.76. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Amirbekian V, Lipinski MJ, Briley-Saebo KC, Amirbekian S, Aguinaldo JG, Weinreb DB, Vucic E, Frias JC, Hyafil F, Mani V, Fisher EA, Fayad ZA. Detecting and assessing macrophages in vivo to evaluate atherosclerosis noninvasively using molecular MRI. Proc. Natl. Acad Sci. USA. 2007;104:961–966. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0606281104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Durr NJ, Larson T, Smith DK, Korgel BA, Sokolov K, Ben-Yakar A. Two-photon luminescence imaging of cancer cells using molecularly targeted gold nanorods. Nano Lett. 2007;7:941–945. doi: 10.1021/nl062962v. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Del Vecchio S, Zanneti A, Fonti R, Pace L, Salvatore M. Nuclear imaging in cancer theranostics. Quart. J. Nucl. Med. Mol. Im. 2007;51:152–163. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Mulder WJM, Strijkers GJ, Briley-Saeboe KC, Frias JC, Aguinaldo JGS, Vucic E, Amirbekian V, Tang C, Chin PTK, Nicolay K, Fayad ZA. Molecular imaging of macrophages in atherosclerotic plaques using bimodal PEG-micelles. Magn. Res. Med. 2007;58:1164–1170. doi: 10.1002/mrm.21315. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Winter PM, Caruthers SD, Zhang H, Williams TA, Wickline SA, Lanza GM. Antiangiogenic synergism of integrin-targeted fumagillin nanoparticles and atorvastatin in atherosclerosis. JACC: Cardiovasc. Im. 2008;1:624–634. doi: 10.1016/j.jcmg.2008.06.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Winter PM, Cai K, Chen J, Adair CR, Kiefer GE, Athey PS, Gaffney PJ, Buff CE, Robertson JD, Caruthers SD, Wickline SA, Lanza GM. Targeted PARACEST nanoparticle contrast agent for the detection of fibrin. Magn. Reson. Med. 2006;56:1384–1388. doi: 10.1002/mrm.21093. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Cyrus T, Abendschein DR, Caruthers SD, Harris TD, Glattauer V, Werkmeister JA, Ramshaw JAM, Wickline SA, Lanza GM. MR three-dimensional molecular imaging of intramural biomarkers with targeted nanoparticles. J. Cardiovasc. Magn. Reson. 2006;8:1–7. doi: 10.1080/10976640600580296. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ahrens ET, Flores R, Xu H, Morel PA. In vivo imaging platform for tracking immunotherapeutic cells. Nat. Biotech. 2005;23:983–987. doi: 10.1038/nbt1121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bulte J. Hot spot MRI emerges from the background. Nat. Biotech. 2005;23:945–946. doi: 10.1038/nbt0805-945. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Medarova Z, Pham W, Farrar C, Petkova V, Moore A. In vivo imaging of siRNA delivery and silencing in tumors. Nat. Med. 2007;13:372–377. doi: 10.1038/nm1486. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Mulder WJM, Douma K, Koning GA, van Zandvoort MA, Lutgens E, Daemen MJ, Nicolay K, Strijkers GJ. Liposome-enhanced MRI of neointimal lesions in the apoE-KO mouse. Magn. Res. Med. 2006;55:1170–1174. doi: 10.1002/mrm.20883. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lanza GM, Winter PM, Caruthers SD, Hughes MS, Cyrus T, Marsh JN, Neubauer AM, Partlow KC, Wickline SA. Nanomedicine opportunities for cardiovascular disease with perfluorocarbon nanoparticles. Nanomedicine. 2006;1:321–329. doi: 10.2217/17435889.1.3.321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Frias JC, Williams KJ, Fisher EA, Fayad ZA. Recombinant HDL-like nanoparticles: a specific contrast agent for MRI of atherosclerotic plaques. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2004;126:16316–16317. doi: 10.1021/ja044911a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Anderson EA, Isaacman S, Peadbody DS, Wang EY, Canary JW. Kirshenbaum K Viral nanoparticles donning a paramagnetic coat: conjugation of MRI contrast agents to the MS2 capsid. Nano Lett. 2006;6:1160–1164. doi: 10.1021/nl060378g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Sitharaman B, Kissell KR, Hartman KB, Tran LA, Baikalov A, Rusakova I, Sun Y, Khant HA, Ludtke SJ, Chiu W, Laus S, Toth W, Helm L, Merbach AE. Superparamagnetic gadonanotubes are high-performance MRI contrast agents. Chem. Commun. 2005:3915–3917. doi: 10.1039/b504435a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.van Tilborg GAF, Mulder WJM, Deckers N, Storm G, Reutelingsperger CPM, Strijkers GJ, Nicolay K. Annexin A5-functionalized bimodal lipid-based contrast agents for the detection of apoptosis. Bioconjate Chem. 2006;17:741–749. doi: 10.1021/bc0600259. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lipinski MJ, Briley-Saebo KC, Mani V, Fayad ZA. "Positive contrast" inversion-recovery with oxide nanoparticles-resonant water suppression magnetic resonance imaging: a change for the better. Journal of the American College of Cardiology. 2008;52:492–494. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2008.03.062. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Briley-Saebo KC, Mulder WJM, Mani V, Hyafil F, Amirbekian V, Aguinaldo JGS, Fisher EA, Fayad ZA. Magnetic resonance imaging of vulnerable atherosclerotic plaques: Current imaging strategies and molecular imaging probes. J. Magn. Reson. Imaging. 2007;26:460–479. doi: 10.1002/jmri.20989. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Walczak P, Zhang J, Gilad AA, Kedziorek DA, Ruiz-Cabello J, Young RG, Pittenger MF, Van Zijl PCM, Huang J, Bulte JWM. Dual-modality monitoring of targeted intraarterial delivery of mesenchymal stem cells after transient ischemia. Stroke. 2008;39:1569–1574. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.107.502047. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Leatherdale CA, Woo W-K, Mikulec FV, Bawendi MG. On the absorption cross section of CdSe nanocrystal quantum dots. J. Phys. Chem. B. 2002;116:7619–7622. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Bruchez M, Jr, Moronne M, Gin P, Weiss S, Alivisatos AP. Semiconductor Nanocrystals as Fluorescent Biological Labels. Science. 1998;281:2013–2016. doi: 10.1126/science.281.5385.2013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Sukhanova A, Devy M, Venteo L, Kaplan H, Artemyev M, Oleinikov V, Klinov D, Pluot M, Cohen JHM. Nabiev I Biocompatible fluorescent nanocrystals for immunolabeling of membrane proteins and cells. Anal. Biochem. 2004;324:60–67. doi: 10.1016/j.ab.2003.09.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Sosnovik D, Weissleder R. Magnetic resonance and fluorescence based molecular imaging technologies. Progress Drug Res. 2005;62:86–114. doi: 10.1007/3-7643-7426-8_3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Hyafil F, Cornily JC, Feig JE, Gordon R, Vucic E, Amirbekian V, Fisher EA, Fuster V, Feldman LJ, Fayad ZA. Noninvasive detection of macrophages using a nanoparticulate contrast agent for computed tomography. Nat. Med. 2007;13:636–641. doi: 10.1038/nm1571. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Rabin O, Perez JM, Grimm J, Wojtkiewicz G, Weissleder R. An X-ray computed tomography imaging agent based on long-circulating bismuth sulphide nanoparticles. Nat. Mater. 2006;5:118–122. doi: 10.1038/nmat1571. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Hainfeld JF, Slatkin DN, Focella TM, Smilowitz HM. Gold nanoparticles: a new X-ray contrast agent. Brit. J. Radiol. 2006;79:248–253. doi: 10.1259/bjr/13169882. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Mukundan S, Ghaghada KB, Badea CT, Kao C-Y, Hedlund LW, Provanzale JM, Johnson GA, Chen E, Bellamkonda RV, Annapragada A. A liposomal nanoscale contrast agent for preclinical CT in mice. AJR. 2006;186:300–307. doi: 10.2214/AJR.05.0523. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Kim D, Park S, Lee JH, Jeong YY, Jon S. Antibiofouling polymer-coated gold nanoparticles as a contrast agent for in vivo x-ray computed tomography imaging. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2007;129:7661–7665. doi: 10.1021/ja071471p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Lumbroso P, Dick CE. X-ray attenuation properties of radiographic contrast media. Med. Phys. 1987;14:752–758. doi: 10.1118/1.595999. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Weissleder R, Mahmood U. Molecular Imaging. Radiology. 2001;219:316–333. doi: 10.1148/radiology.219.2.r01ma19316. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Villanueva FS, Jankowski RJ, Klibanov S, Pina ML, Alber SM, Watkins SC, Brandenburger GH, Wagner WR. Microbubbles targeted to intercellular adhesion molecule-1 bind to activated coronary artery endothelial cells. Circulation. 1998;98:1–5. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.98.1.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Klibanov AL. Microbubble contrast agents targeted ultrasound imaging and ultrasound-assisted drug-delivery applications. Invest. Radiol. 2006;41:354–362. doi: 10.1097/01.rli.0000199292.88189.0f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Huang SL, Hamilton AJ, Pozharski E, Nagaraj A, Klegerman ME, McPherson DD, MacDonald RC. Physical correlates of the ultrasonic reflectivity of lipid dispersions suitable as diagnostic contrast agents. Ultrasound Med. Biol. 2002;28:339–348. doi: 10.1016/s0301-5629(01)00512-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Lanza GM, Wallace KD, Scott MJ, Cacheris WP, Abendschein DR, Christy DH, Sharkey AM, Miller JG, Gaffney PJ, Wickline SA. A novel site-targeted ultrasonic contrast agent with broad biomedical application. Circulation. 1996;94:3334–3340. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.94.12.3334. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Schiffelers RM, Banciu M, Metselaar JM, Storm G. Therapeutic application of long circulation liposomal glucocorticoids in auto-immune diseases and cancer. J. Liposome Res. 2006;16:185–194. doi: 10.1080/08982100600851029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Berry CC, Wells S, Charles S, Curtis ASG. Dextran and albumin derivatised iron oxide nanoparticles: influence on fibroblasts in vitro. Biomaterials. 2003;24:4551–4557. doi: 10.1016/s0142-9612(03)00237-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Liu HL, Ko SP, Wu JH, Jung MH, Min JH, Lee JH, An BH, Kim YK. One-pot polyol synthesis of monosize PVP-coated sub-5nm Fe3O4 nanoparticles for biomedical applications. J. Magnetism Magnetic Mater. 2007;310:E815–E817. [Google Scholar]

- 49.Zhang Y, Kohler N, Zhang M. Surface modification of superparamagnetic magnetite nanoparticles and their intracellular uptake. Biomaterials. 2002;23:1553–1561. doi: 10.1016/s0142-9612(01)00267-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Selvan ST, Tan TT, Ying JY. Robust, non-cytotoxic, silica-coated CdSe quantum dots with efficient photoluminescence. Adv. Mater. 2005;17:1620–1625. [Google Scholar]

- 51.Otsuka H, Nagasaki Y, Kataoka K. PEGylated nanoparticles for biological and pharmaceutical applications. Adv. Drug Deliv. 2003;55:403–419. doi: 10.1016/s0169-409x(02)00226-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Vallet-Regi M, Balas F, Arcos D. Mesoporous materials for drug delivery. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2007;46:7548–7558. doi: 10.1002/anie.200604488. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Chowdhury EH, Akaike T. Bio-functional inorganic materials: An attractive branch of gene-based nano-medicine delivery for 21st century. Curr. Gene Ther. 2005;5:669–676. doi: 10.2174/156652305774964613. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Slowing II, Trewyn BG, Lin VSY. Mesoporous silica nanoparticles for intracellular delivery of membrane-impermeable proteins. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2007;129:8845–8849. doi: 10.1021/ja0719780. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.van Schooneveld MM, Vucic E, Koole R, Zhou Y, Stocks J, Cormode DP, Tang CY, Gordon R, Nicolay K, Meijerink A, Fayad ZA, Mulder WJM. Improved biocompatibility and pharmacokinetics of silica nanoparticles by means of a lipid coating: a multimodality investigation. Nano Lett. 2008;8:2517–2525. doi: 10.1021/nl801596a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Cormode DP, Mulder WJM, Fisher EA, Fayad ZA. Modified lipoproteins as contrast agents for molecular imaging. Future Lipidol. 2007;2:587–590. [Google Scholar]

- 57.Huang X, Bronstein LM, Retrum J, Dufort C, Tsvetkova I, Aniagyei S, Stein B, Stucky G, McKenna B, Rennes N, Baxter D, Kao CC, Dragnea B. Self-assembled virus-like particles with magnetic cores. Nano Lett. 2007;7:2407–2416. doi: 10.1021/nl071083l. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Sun J, DuFort C, Daniel M-C, Murali A, Chen C, Gopinath K, Stein B, De M, Rotello VM, Holzenburg A, Kao CC, Dragnea B. Core-controlled polymorphism in virus-like particles. Proc. Natl. Acad Sci. USA. 2007;104:1354–1359. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0610542104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Cormode DP, Skajaa T, van Schooneveld MM, Koole R, Jarzyna P, Lobatto ME, Calcagno C, Barazza A, Gordon RE, Zanzonico P, Fisher EA, Fayad ZA, Mulder WJM. Nanocrystal core high-density lipoproteins: A multimodal molecular imaging contrast agent platform. Nano Lett. 2008;8:3715–3723. doi: 10.1021/nl801958b. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Sanz J, Fayad ZA. Imaging of atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease. Nature. 2008;451:953–957. doi: 10.1038/nature06803. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Kwon GS, Kataoka K. Block copolymer micelles as long-circulating drug vehicles. Adv. Drug Deliv. Rev. 1995;16:295–309. [Google Scholar]

- 62.Ruehm SG, Corot C, Vogt P, Kolb S, Debatin JF. Magnetic resonance imaging of atherosclerotic plaque with ultrasmall superparamagnetic particles of iron oxide in hyperlipidemic rabbits. Circulation. 2001;103:415–422. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.103.3.415. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Kang HW, Weissleder R, Bogdanov A. Targeting of MPEG-protected polyamino acid carrier to human E-selectin in vitro. Amino Acids. 2002;23:301–308. doi: 10.1007/s00726-001-0142-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Schellenberger EA, Sosnovik D, Weissleder R, Josephson L. Magneto/optical annexin V, a multimodal protein. Bioconjugate Chem. 2004;15:1062–1067. doi: 10.1021/bc049905i. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Nahrendorf M, Jaffer FA, Kelly KA, Sosnovik DE, Aikawa E, Libby P, Weissleder R. Noninvasive vascular cell adhesion molecule-1 imaging identifies inflammatory activation of cells in atherosclerosis. Circulation. 2006;114:1504–1511. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.106.646380. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Javier DJ, Nitin N, Levy M, Ellington A, Richards-Kortum R. Aptamer-targeted gold nanoparticles as molecular-specific contrast agents for reflectance imaging. Bioconjugate Chem. 2008;19:1309–1312. doi: 10.1021/bc8001248. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Villanueva FS, Lu EX, Bowry S, Kilic S, Tom E, Wang JJ, Gretton J, Pacella JJ, Wagner WR. Myocardial ischemic memory imaging with molecular echocardiography. Circulation. 2007;115:345–352. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.106.633917. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Zheng G, Chen J, Li H, Glickson JD. Rerouting lipoprotein nanoparticles to selected alternate receptors for the targeted delivery of cancer diagnostic and therapeutic agents. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2005;102:17757–17762. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0508677102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Frangioni JV. New technologies for human cancer imaging. J. Clin. Oncol. 2008;26:4012–4021. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2007.14.3065. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Weissleder R, Kelly K, Sun EY, Shtatland T, Josephson L. Cell-specific targeting of nanoparticles by multivalent attachment of small nanoparticles. Nat. Biotech. 2005;23:1418–1423. doi: 10.1038/nbt1159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Serda RE, Adolphi NL, Bisoffi M, Sillerud LO. Targeting and cellular trafficking of magnetic nanoparticles for prostate cancer imaging. Mol. Imaging. 2007;6:277–288. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Paganelli G, Chinol M, Maggiolo M, Sidoli A, Corti A, Baroni S, Siccardi AG. The three-step pretargeting approach reduces the human anti-mouse antibody response in patients submitted to radioimmunoscintigraphy and radioimmunotherapy. Eur. J. Nucl. Med. 1997;24:350–351. doi: 10.1007/BF01728778. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Torchilin VP. Recent advances with liposomes as pharmaceutical carriers. Nat. Rev. Drug. Discov. 2005;4:145–160. doi: 10.1038/nrd1632. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Gupta AK, Gupta M. Synthesis and surface engineering of iron oxide nanoparticles for biomedical applications. Biomaterials. 2005;26:3995–4021. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2004.10.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Hostetler MJ, Wingate JE, Zhong CJ, Harris JE, Vachet RW, Clark MR, Londono JD, Green SJ, Stokes JJ, Wignall GD, Glish GL, Porter MD, Evans ND, Murray RW. Alkanethiolate gold cluster molecules with core diameters from 1.5 to 5.2 nm: core and monolayer properties as a function of core size. Langmuir. 1998;14:17–30. [Google Scholar]

- 76.van Helden AK, Jansen JW, Vrij A. Preparation and characterization of spherical monodisperse silica dispersions in nonaqueous solvents. J. Colloid Interface Sci. 1980;78:354–368. [Google Scholar]

- 77.Murray CB, Norris DJ, Bawendi MG. Synthesis and characterization of nearly monodisperse CdE (E=S, Se, Te) semiconductor nanocrystallites. J. Am Chem. Soc. 1993;115:8706–8715. [Google Scholar]

- 78.Choi HS, Liu W, Misra P, Tanaka E, Zimmer JP, Ipe BI, Bawendi MG, Frangioni JV. Renal clearance of quantum dots. Nat. Biotech. 2007;25:1165–1170. doi: 10.1038/nbt1340. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Michalet X, Pinaud FF, Bentolila LA, Tsay JM, Doose S, Li JJ, Sundaresan G, Wu AM, Gambhir SS, Weiss S. Quantum dots for live cells, in vivo imaging, and diagnostics. Science. 2005;307:538–544. doi: 10.1126/science.1104274. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.McAteer MA, Sibson NR, von zur Muhlen C, Schneider JE, Lowe AS, Warrick N, Channon KM, Anthony DC, Choudhury RP. In vivo magnetic resonance imaging of acute brain inflammation using microparticles of iron oxide. Nat. Med. 2007;13:1253–1258. doi: 10.1038/nm1631. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Gleich B, Weizenecker J. Tomographic imaging using the nonlinear response of magnetic particles. Nat. Biotech. 2005;435:1214–1217. doi: 10.1038/nature03808. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Gaumet M, Vargas A, Gurny R, Delie F. Nanoparticles for drug delivery: the need for precision in reporting particle size parameters. Eur. J. Pharm. Biopharm. 2008;69:1–9. doi: 10.1016/j.ejpb.2007.08.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Brust M, Walker M, Bethell D, Schiffrin DJ, Whyman R. Synthesis of thiol-derivatised gold nanoparticles in a two-phase liquid-liquid system. Chem. Commun. 1994:801–802. [Google Scholar]

- 84.Kim BS, Qiu JM, Wang JP, Taton TA. Magnetomicelles: composite nanostructures from magnetic nanoparticles and cross-linked amphiphilic block copolymers. Nano Lett. 2005;5:1987–1991. doi: 10.1021/nl0513939. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Yu WW, Chang E, Falkner JC, Zhang J, Al-Somali AM, Sayes CM, Johns J, Drezek R, Colvin VL. Forming biocompatible nonaggregated and nanocrystals in water using amphiphilic polymers. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2007;129:2871–2879. doi: 10.1021/ja067184n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.McCarthy JR, Kelly KA, Sun EY, Weissleder R. Targeted delivery of multifunctional magnetic nanoparticles. Nanomedicine. 2007;2:153–167. doi: 10.2217/17435889.2.2.153. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87. http://www.fda.gov/nanotechnology/

- 88.Davies JC. Nanotechnology Oversight: An Agenda for the New Administration. Woodrow Wilson International Center for Scholars, Project on Emerging Nanotechnologies. 2008 PEN 13. [Google Scholar]

- 89. http://nanoehsalliance.org/

- 90.Shaw SY, Westly EC, Pittet MJ, Subramanian A, Schreiber SL, Weissleder R. Perturbational profiling of nanomaterial biologic activity. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2008;105:7387–7392. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0802878105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Mancini MC, Kairdolf BA, Smith AM, Nie S. Oxidative quenching and degradation of polymer-encapsulated quantum dots: new insights into the long-term fate and toxicity of nanocrystals in vivo. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2008;130:10836–10837. doi: 10.1021/ja8040477. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]