Abstract

OBJECTIVE

This study assessed the effects of balance/strength training on falls risk and posture in older individuals with type 2 diabetes.

RESEARCH DESIGN AND METHODS

Sixteen individuals with type 2 diabetes and 21 age-matched control subjects (aged 50–75 years) participated. Postural stability and falls risk was assessed before and after a 6-week exercise program.

RESULTS

Diabetic individuals had significantly higher falls risk score compared with control subjects. The diabetic group also exhibited evidence of mild-to-moderate neuropathy, slower reaction times, and increased postural sway. Following exercise, the diabetic group showed significant improvements in leg strength, faster reaction times, decreased sway, and, consequently, reduced falls risk.

CONCLUSIONS

Older individuals with diabetes had impaired balance, slower reactions, and consequently a higher falls risk than age-matched control subjects. However, all these variables improved after resistance/balance training. Together these results demonstrate that structured exercise has wide-spread positive effects on physiological function for older individuals with type 2 diabetes.

Older individuals with type 2 diabetes often exhibit greater impairments in posture and gait and are typically at increased risk of falling (1,2). This study was designed to assess whether type 2 diabetic individuals exhibited differences in balance, reaction time, and falls risk compared with control subjects and to examine the effects of training on these measures.

RESEARCH DESIGN AND METHODS

Sixteen type 2 diabetic individuals (62.3 ± 5.5 years; average diabetes duration 15.2 ± 2.4 years) and 21 age-matched control subjects (64.7 ± 7.1 year) participated. Exclusion criteria included cardiovascular disease, unstable proliferative retinopathy, end-stage renal disease, uncontrolled hypertension, and/or participation in balance/resistance training during the previous year. All procedures complied with institutional review board guidelines.

Initial assessment included a complete history, physical examination, and full neurologic evaluation that included assessment for somatic/autonomic neuropathy (3). Warm-cold thermal perception, 128-Hz vibration perception, touch, pressure, and prickling pain perception were evaluated. An overall total neuropathy score was also calculated. The average A1C for the type 2 diabetic group was 7.5 ± 0.3%. Following screening, a record of previous falls, balance, reaction time, and falls risk assessments were completed. Individuals then completed a 6-week, thrice-weekly exercise program followed by posttraining evaluations.

Each exercise session consisted of a balance/posture component (e.g., lower-limb stretches and leg, abdominal, and lower-back exercises) and a resistance-/strength-training component (e.g., lower-/upper-limb exercises performed using strength-training machines). Participants performed 1–2 sets of 10–12 repetitions, with rests between exercises.

Falls risk

Risk of falling was determined using the long-form physiological profile assessment (PPA). This validated tool (4) assesses vision, sensation, proprioception, lower-limb strength, postural sway/coordination, and cognitive function.

Participants completed a simple reaction time (SRT) task where upper-limb (finger) and lower-limb (foot) responses were assessed. Individuals responded to a visual cue by depressing a timing switch. Fifteen trials were completed with each segment.

A repeated-measures, generalized linear model was used to assess for group and training effects. Significant effects were further examined using planned contrasts (one-way ANOVAs). Analyses were performed using SAS statistical software (SAS Institute) with P < 0.05.

RESULTS

Clinical assessment

Diabetic individuals exhibited significant differences in total neuropathy scores (left foot F1,35 = 9.87; right foot F1,35 = 8.86; all P < 0.05), BMI (F1,35 = 22.50; P < 0.05), and percent body fat (F1,35 = 7.11; P < 0.05). There were no significant group/exercise differences in blood pressure measurements for either sitting (pretraining: control subjects 128.2 ± 3.4/73.4 ± 2.3 mmHg, type 2 diabetes 133.0 ± 4.2/69.1 ± 2.7 mmHg; posttraining: control subjects 123.6 ± 2.8/70.7 ± 2.2 mmHg, type 2 diabetes 130.0 ± 4.6/67.4 ± 3.2 mmHg) or standing (pretraining control subects 125.8 ± 2.8/73.8 ± 2.2 mmHg, type 2 diabetes 133.4 ± 4.1/72.14 ± 3.3 mmHg; posttraining control subjects 119.8 ± 2.9/74.6 ± 2.5 mmHg, type 2 diabetes 127.7 ± 6.0/68.8 ± 3.2 mmHg). No significant group/exercise differences were found for the following measures of autonomic function: expiration-to-inspiration (E:I) ratio (control subjects 1.13 ± 0.02; type 2 diabetes 1.15 ± 0.02), Valsalva maneuver (control subjects 1.25 ± 0.03; type 2 diabetes 1.25 ± 0.07), and stand ratio (control subjects 1.36 ± 0.16; type 2 diabetes 1.48 ± 0.29).

Falls history

A significant group difference was found for the average number of falls (F1,35 = 4.44; P < 0.05), with type 2 diabetic subjects experiencing more falls over the past year. No group difference in falls was observed posttraining.

Falls risk

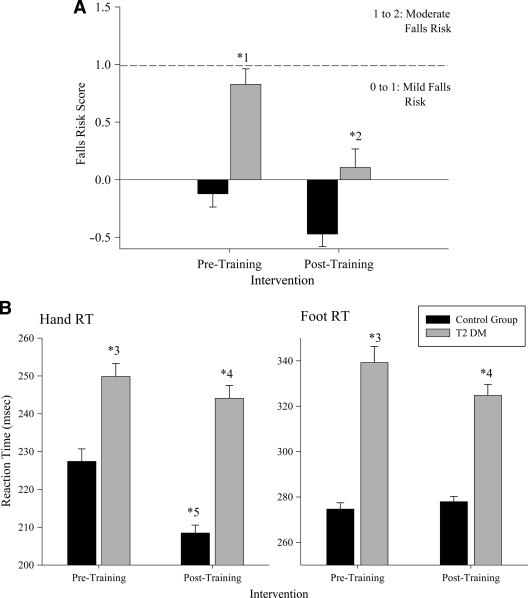

As shown in Fig. 1, type 2 diabetic subjects had a significantly higher falls risk score compared with control subjects (F1,35 = 20.24; P < 0.05). Following training, both groups exhibited reduced falls risk, but this was only significant for type 2 diabetic individuals (F1,35 = 33.03; P < 0.05). While no age effects were observed, correlation analysis revealed a significant falls risk–age relationship for the type 2 diabetic group (r = 0.519; P < 0.05).

Figure 1.

Changes in the falls risk (A) and average hand and foot simple reaction times (B) between control and type 2 diabetic groups. Mean values are shown for each group prior to and following the exercise intervention. Error bars represent 1 SE of the mean. For the falls risk, significant differences were observed between the groups prior to exercise (*1) and, for the type 2 diabetic group only, following training (*2). For the reaction time (RT) results, significant differences were observed in the hand and foot reaction time values between the groups prior to exercise (*3). Following training, the type 2 diabetes exhibited a significant reduction in both foot and hand reaction time values (*4). For the control subjects, only the hand reaction time values showed a decrease after training (*5).

Analysis of the individual PPA measures showed that type 2 diabetic individuals exhibited reduced proprioception (F1,35 = 5.89; P < 0.05), sensation (F1,35 = 5.78; P < 0.05), and ankle strength (F1,35 = 4.17; P < 0.05) compared with control subjects. Following training, a significant group-by-exercise effect was seen for proprioception (F1,35 = 4.54; P < 0.05), quadriceps (F1,35 = 9.11; P < 0.05), and hamstring strength (F1,35 = 5.07; P < 0.05). Planned contrasts revealed that both groups showed improvements in strength and proprioception postexercise.

Reaction time

There was a significant group difference for hand (F1,35 = 7.22; P < 0.05) and foot SRT (F1,35 = 9.64; P < 0.05), with the diabetic group being significantly slower (Fig. 1). Posttraining, a significant improvement in both SRT measures (hand F1,35 = 11.87; foot F1,35 = 14.52; all P < 0.05) was found. Planned contrasts revealed that both groups recorded faster hand SRT following exercise. However, only the type 2 diabetic group exhibited significantly faster foot SRT posttraining.

CONCLUSIONS

Normal aging is associated with slower cognitive processing (5), slower postural reactions (6), and decreased muscle strength (7), all of which are essential for optimal balance (8). The current study demonstrated that all older individuals showed a decline in SRT and strength, although the decrement was more pronounced for those with diabetes. The decline in function for older diabetic individuals was further compounded since they had a higher previous history of falls and all exhibited mild-to-moderate neuropathy, the latter being associated with increased falls risk (9). Consequently, the type 2 diabetic group was at greater falls risk, confirming the view that increasing age, previous falls history, increased postural sway, and presence of diabetes are major risk factors for falling (1,2,8,10–12).

Following training, the diabetic group exhibited a significant decline in falls risk, dropping from a mild-to-moderate to a low-to-mild risk of falling. This decline was reflected by improved proprioception and increased hamstring/quadriceps strength. While increasing physical activity can lead to enhanced joint proprioception, a learning effect cannot be ruled out as a contributing factor for the improved lower-limb proprioception. Both groups also demonstrated significant improvements in SRT. The ability to respond quickly to any external perturbation is essential for correcting oneself to avoid possible falls (4,6,11). Unfortunately, many older individuals exhibit slower reaction times (5,11) and are at increased risk of falling since they respond slower under postural situations (6). The improved reaction time with exercise has obvious implications for individuals at high falls risk to correct themselves during balance-threatening situations. While hypoglycemia could be one reason for slower reaction times for the diabetic group (13), any decreased glucose levels would not explain the significantly improved SRTs seen postexercise. While increased strength correlates highly with improved balance and decreased falls risk (14,15), our results show that the benefits of exercise are not limited to muscle function. Rather, training resulted in improvements in a range of falls risk factors, impacting positively on sensory, motor, and cognitive processes.

Overall, this study demonstrated that older type 2 diabetic individuals are at increased falls risk. Following training, the type 2 diabetic group demonstrated improvements in balance, proprioception, lower-limb strength, reaction time, and, consequently, decreased risk of falling. The results support the practice of prescribing mild-to-moderate exercise to individuals with type 2 diabetes to alleviate falls risk.

Acknowledgments

No potential conflicts of interest relevant to this article were reported.

Footnotes

The costs of publication of this article were defrayed in part by the payment of page charges. This article must therefore be hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 U.S.C. Section 1734 solely to indicate this fact.

References

- 1. Maurer MS, Burcham J, Cheng H. Diabetes mellitus is associated with an increased risk of falls in elderly residents of a long-term care facility. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci 2005;60:1157–1162 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Schwartz AV, Hillier TA, Sellmeyer DE, Resnick HE, Gregg E, Ensrud KE, Schreiner PJ, Margolis KL, Cauley JA, Nevitt MC, Black DM, Cummings SR. Older women with diabetes have a higher risk of falls: a prospective study. Diabetes Care 2002;25:1749–1754 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Vinik A, Suwanwalaikorn S, Stansberry K, Holland M, McNitt P, Colen L. Quantitative measurement of cutaneous perception in diabetic neuropathy. Muscle Nerve 1995;18:574–584 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Lord SR, Menz HB, Tiedemann A. A physiological profile approach to falls risk assessment and prevention. Physical Ther 2003;83:237–252 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Dhesi JK, Bearne LM, Moniz C, Hurley MV, Jackson SHD, Swift CG, Allain TJ. Neuromuscular and psychomotor function in elderly subjects who fall and the relationship with vitamin D status. J Bone Min Res 2002;17:891–897 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Tucker MG, Kavanagh JJ, Morrison S, Barrett RS. Voluntary sway and rapid orthogonal transitions of voluntary sway in young adults, and low and high fall-risk older adults. Clin Biomech 2009;24:597–605 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Fukagawa NK, Wolfson L, Judge J, Whipple R, King M. Strength is a major factor in balance, gait, and the occurrence of falls. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci 1995;50A:64 67 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Close JCT, Lord SL, Menz HB, Sherrington C. What is the role of falls? Best Pract Res Clin Rheumatol 2005;19:913–935 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Richardson JK, Hurvitz EA. Peripheral neuropathy: a true risk factor for falls. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci 1995;50A:M211 M215 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Uccioli L, Giacomini PG, Pasqualetti P, Di Girolamo S, Ferrigno P, Monticone G, Bruno E, Boccasena P, Magrini A, Parisi L, Menzinger G, Rossini PM. Contribution of central neuropathy to postural instability in IDDM patients with peripheral neuropathy. Diabetes Care 1997;20:929–934 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Lord S, Sherrington C, Menz H, Close J. Falls in Older People: Risk Factors and Strategies for Prevention. 2nd ed. Cambridge, Cambridge University Press, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 12. Schwartz AV, Vittinghoff E, Sellmeyer DE, Feingold KR, Rekeneire Nd, Strotmeyer ES, Shorr RI, Vinik AI, Odden MC, Park SW, Faulkner KA, Harris TB. the Health, Aging, and Body Composition Study. Diabetes-related complications, glycemic control, and falls in older adults. Diabetes Care 2008;31:391–396 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Bremer JP, Jauch-Chara K, Hallschmid M, Schmid S, Schultes B. Hypoglycemia unawareness in older compared with middle-aged patients with type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Care 2009;32:1513–1517 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Barnett A, Smith B, Lord SR, Williams M, Baumand A. Community-based group exercise improves balance and reduces falls in at-risk older people: a randomised controlled trial. Age Ageing 2003;32:407–414 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Buchner DM, Cress ME, de Lateur BJ, Esselman PC, Margherita AJ, Price R, Wagner EH. The effect of strength and endurance training on gait, balance, fall risk, and health services use in community-living older adults. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci 1997;52A:M218 M224 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]