Abstract

Naturally occurring regulatory T cells (Treg) express high levels of glucocorticoid-induced tumour necrosis factor receptor (GITR). However, studies of the role of GITR in Treg biology has been complicated by the observation that upon activation effector CD4+ T (Teff) cells also express the receptor. Here, we dissect the contribution of GITR-induced signaling networks in the expansion and function of FoxP3+ Treg. We demonstrate that a high-affinity soluble Fc-GITR-L dimer, in conjugation with αCD3, specifically enhances in vitro proliferation of Treg, which retain their phenotypic markers (CD25 and FoxP3) and their suppressor function, while minimally affecting Teff cells. Furthermore, Fc-GITR-L does not impair Teff susceptibility to suppression, as judged by cocultures employing GITR-deficient and GITR-sufficient CD4+ T-cell subsets. Notably, this expansion of Treg could also be seen in vivo, by injecting FoxP3-IRES-GFP mice with Fc-GITR-L even in the absence of antigenic stimulation. In order to test the efficacy of these findings therapeutically, we made use of a C3H/HeJ hemophilia B-prone mouse model. The use of liver-targeted human coagulation factor IX (hF.IX) gene therapy in this model has been shown to induce liver toxicity and the subsequent failure of hF.IX expression. Interestingly, injection of Fc-GITR-L into the hemophilia-prone mice that were undergoing liver-targeted hF.IX gene therapy increased the expression of F.IX and reduced the anticoagulation factors. We conclude that GITR engagement enhances Treg proliferation both in vitro and in vivo and that Fc-GITR-L may be a useful tool for in vivo tolerance induction.

Keywords: expansion, gene therapy, glucocorticoid-induced TNF receptor, immune tolerance, TNFR18

Introduction

The immune system has the ability to distinguish self from nonself, which enables it to remove foreign antigens without inducing autoimmunity. Deletion of most self-reactive T-cell clones occurs during development in the thymus and is known as central tolerance. However, because some self-reactive T cells escape this selection process, peripheral tolerance mechanisms are required to effectively prevent autoimmune diseases. Naturally occurring CD4+CD25+ Treg cells represent one of the best documented systems governing peripheral suppression of CD4+ and CD8+ T cells (1, 2). Regulatory T cells (Treg) suppress T cell-induced diseases in animal models of inflammatory bowel diseases (3–5), experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis (EAE) (6–8), autoimmune myocarditis and skeletal muscle myositis (9), and graft-versus-host disease (10, 11), which confirm their regulatory function of adaptive immune responses. These cells have been shown to proliferate in vivo, as judged in a cotransfer model with disease-inducing T cells (12, 13). A variety of different mechanisms have been suggested for Treg-mediated suppressive function (14).

The transcription factor FoxP3 controls the development of naturally occurring Treg, as demonstrated in patients with the immune dysregulation, polyendocrinopathy, enteropathy, X-linked syndrome or in scurfy mutant mice that lack a functional FoxP3 gene and consequently Treg (15–17). Additional evidence is provided by data showing that ectopic expression of FoxP3 by retroviral gene transfer into CD4+CD25− cells endows them with suppressor functions (16). Neither naive nor activated CD4+CD25− T cells express FoxP3, rendering expression of this transcription factor the most specific marker for Treg in contrast to CD25, glucocorticoid-induced tumour necrosis factor receptor (GITR) or cytotoxic T-lymphocyte antigen-4, all of which can be expressed in activated CD4+CD25− T cells. FoxP3+ Treg are not only generated in the thymus (18) but have also been reported to be inducible in the peripheral organs under specific conditions (19, 20).

The GITR-related gene is a member of the tumor necrosis factor (TNF) receptor superfamily (TNFRSF18). This gene was first cloned from a murine T-cell hybridoma as a dexamethasone-inducible molecule (21). GITR is highly expressed on naturally occurring CD4+CD25+ Treg. However, GITR is also expressed at lower levels on the surface of naive T cells, but its expression is up-regulated after activation (5). Its ligand, GITR ligand (GITR-L, TNFSF18), was cloned from both human and mouse cells by several groups (22–25). Mouse GITR-L is expressed at low levels in non-stimulated B cells and bone marrow-derived dendritic cells (BMDCs) and is transiently inducible by LPS (23, 25). Recent structural analyses reveal that unlike human GITR-L and other TNF family members, mouse GITR-L assembles into a functional dimer, which renders its structural and biomedical properties unique within the members of the TNF and TNFRSFs, which form trimers (26, 27).

Administration of αGITR mAb not only abrogates Treg-mediated suppression of CD4+CD25− effector CD4+ T cells (Teff) in vitro but it also breaks immunological tolerance against self-antigen and some types of progressive tumor cells in vivo (5, 24, 25, 28, 29). How GITR ligation regulates T cell-mediated autoimmunity in vivo and what the consequences of GITR–GITR-L interactions are for Treg functions are generally not well understood. In experiments using cocultures of CD4+CD25+ Treg and CD4+CD25− Teff with irradiated antigen-presenting cells (APC), anti-GITR was shown to reduce the suppressive capability of Treg (5). Similar results were also observed using a soluble GITR-L (24). By contrast, a second group using a similar system, but replacing the mAb with a GITR-L-expressing cell line, found that Teff became refractory to Treg-mediated suppression (25).

In an attempt to further elucidate the mechanisms by which GITR signaling regulates T cell-mediated immune responses, we used an Fc-GITR-L fusion protein together with CD4+ T-cell subsets derived from either wild type (wt) or GITR−/− mice and an in vitro system in which magnetic beads are coupled with αCD3ε. Our results indicate that ligation of the co-stimulatory molecule GITR by its soluble ligand induces the in vitro and in vivo proliferation of CD4+CD25+FoxP3+ Treg. The suppressive activity of Treg remains high in the presence of Fc-GITR-L in cocultures or after the in vitro expansion of isolated FoxP3+ Treg. In a gene therapy mouse model, when human coagulation factor (hF.IX) gene was forcefully expressed in C3H/HeJ hemophilia B mice by an adeno-associated virus (AAV) vector, combined treatment of Fc-GITR-L enhanced the human coagulation factor IX (hF.IX) level and inhibited the production of anti-coagulation factors. Taken together, the results indicate that GITR ligation differentially governs immune responses by T-cell subsets and that the preferential induction of Treg makes GITR signaling more pro-tolerant than pro-inflammatory.

Methods

Mice

Pathogen-free B6129SF1 mice were obtained from JaxMice (Bar Harbor, ME, USA). GITR−/− mice were provided by Drs C. Riccardi and P. P. Pandolfi (30). Generation of the FoxP3-IRES-EGFP knock-in mice was described previously (31). FoxP3-IRES-EGFP knock-in C57BL/6 mice were generously provided by Dr V. Kuchroo (32). These animals were housed in the new research building animal facility of Harvard Medical School. The experiments were performed according to the guidelines of Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee at Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center and Harvard. Hemophilia B mice carrying an F9 gene deletion had been repeatedly backcrossed onto C3H/HeJ background (>10 generations) prior to experiments (33). Experiments in hemophilia B mice were in accordance with protocols approved by Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee at the University of Florida, Gainesville.

Reagents

Anti-CD3ε (145-2C11)-biotin was from Biolegend (San Diego, CA, USA). Anti-CD4-PerCP, αCD25-PE, anti-human IgG-PE and IL-2 ELISA kit were products of BD Biosciences (San Jose, CA, USA). Anti-human IgG-FITC was from Jackson ImmunoResearch Laboratory (West Grove, PA, USA). Anti-IκBα was from Cell Signaling Technology (Boston, MA, USA). Anti-β-actin was from Santa Cruz Biotechnology Inc. (Santa Cruz, CA, USA). 4′,6′-Diamidino-2-phenylindole (DAPI) and carboxyfluorescein diacetate, succinimidyl ester (CFSE) were from Invitrogen (Carlsbad, CA, USA). RPMI 1640 was from Cellgro (Manassas, VA, USA). Recombinant granulocyte macrophage colony-stimulating factor (rGMCSF), recombinant interleukin (rIL)-4, rIL-2 and αGITR-FITC were from R&D (Minneapolis, MN, USA). Thymidine labeled with [3H] was from Amersham Biosciences (Piscataway, NJ, USA). Phenylmethylsulfonylfluoride (PMSF) was from Sigma–Aldrich (Saint Louis, MO, USA). Protease inhibitor cocktail was from Roche (Nutley, NJ, USA). Coagulation factor IX was from Wyeth Pharmaceuticals Inc. (Philadelphia, PA, USA). CellTrace™ CFSE Cell Proliferation Kit was from Invitrogen.

Production of Fc-GITR-L

The extracellular domain of the type II transmembrane protein GITR-L (41–173 AA) was amplified by PCR from full-length mouse GITR-L that was cloned previously (24) and fused to the C-terminus of hIgG1 Fc to form a Fc-GITR-L fusion protein, which was placed under the control of the cytomegalovirus promoter in expression vector pCDNA4/myc-HisC from Invitrogen. The κ light chain leader sequence (5′ATGGAGACAGACACACTCCTGCTATGGGTACTGCTGCTC TGGGTTCCAGGTTCCACTGGTGA3′) was introduced in front of the hIgG1 Fc fragment for helping the secretion of the fusion protein. 293F cells transfected with the plasmid expressing Fc-GITR-L were selected with zeocin for stable cell lines. Stable Fc-GITR-L-expressing cells were cultured in Corning spin bottles, and Fc-GITR-L fusion protein was purified with a protein G agarose bead column from the supernatant. Purified Fc-GITR-L fusion protein was typically >95% pure by Coomassie blue staining analysis.

Coupling αCD3ϵ to MACSi Beads

Ten micrograms of biotin-αCD3 antibody was diluted to 500 μl with 1× PBS supplemented with 2 mM of EDTA and 5% of BSA; then the diluted antibody was mixed with 500 μl of anti-biotin MACSi Bead (1 × 108 particles) (Miltenyi Biotec Inc., Auburn, AL, USA) and rotated at 4°C for 2 h. Anti-CD3 beads were washed with RPMI medium (RPMI 1640 supplemented with 10% FCS, 100 U ml−1 of penicillin, 100 μg ml−1 of streptomycin, 2 mM of L-glutamine, 1 mM of sodium pyruvate and 50 μM of β-mercaptoethanol) before being used for T-cell activation.

In vitro CD4+ T-cell expansion

CD3+ T cells were enriched from splenocytes of Foxp3-IRES-EGFP knock-in mice with mouse T-cell enrichment columns (R&D) and stained with PerCP-αCD4 and PE-αCD25 and purified by FACS. CD4+CD25−GFP− Teff or CD4+CD25+GFP+ Treg was of >97% or 99% purity, respectively. 105 cells per well were seeded in a 96-well plate. Cells were stimulated with αCD3-bead (2 x 105 particles per well) and Fc-GITR-L (1 μg ml−1) in the presence of IL-2 (10 ng ml−1) for 1, 2, 3, or 4 days. Total live cell number was counted manually using 0.4% trypan blue under the microscope, which was then normalized to the initial number for the fold of proliferation. To determine the frequency of FoxP3- and CD25-expressing cells, cells were stained with PerCP-αCD4 and PE-αCD25 and DAPI. DAPI-negative cells representing the live cells were gated to analyze the frequency of CD4+, GFP+ (FoxP3+) and CD25+ cells.

Flow cytometry analysis

For analyzing the expression of cell surface molecules, the BD LSRII Flow Cytometer was used to collect flow cytometric data and analyzed with FlowJo Software.

Isolation of CD4+ T cells

CD4+CD25− Teff and CD4+CD25+ Treg were isolated from splenocytes with the mouse CD4+CD25+ Treg isolation kit (Miltenyi Biotec Inc.; unless otherwise noted). Briefly, biotin-conjugated monoclonal anti-mouse antibodies against CD8a, CD11b, CD45R, CD49b and Ter-119 were incubated with splenocytes, then anti-biotin-coupled MACS bead was added to the cell mixture and the CD4+ T cells were eluted off from the MACS bead by negative selection. Anti-CD25-PE- and anti-PE-coupled beads were added to the CD4+ T cells to separate the CD4+CD25+ and CD4+CD25− T cells. The CD4+CD25+ Treg were typically 80% pure and CD4+CD25− Teff were >85% pure.

T-cell proliferation assay and Treg suppression assay using αCD3-beads

Purified CD4+CD25− (2 × 105 cells per well) and/or CD4+CD25+ (5 × 104 cells per well) T cells were stimulated in RPMI medium (supplemented with 10% FCS, 100 U ml−1 of penicillin, 100 μg ml−1 of streptomycin, 2 mM of L-glutamine, 1 mM of sodium pyruvate and 50 μM of β-mercaptoethanol) with αCD3-beads (2 × 105 per well) and Fc-GITR-L (1 μg ml−1) fusion protein for 72 h. Thymidine labeled with [3H] was added at 1 μCi per well for the final 18 h before cells were harvested to the membrane and analyzed with a beta plate reader.

CFSE dilution assay

CD4+CD25− and CD4+CD25+ T cells were FACS-purified from wt and GITR−/− splenocytes and stained with CFSE according to the manufacturer’s protocol. Teff and Treg, in which one of them was labeled with CFSE, were cocultured at 8:1 ratio and stimulated with αCD3-bead. Three days later, cell proliferation was analyzed in the FITC channel.

Cytokine production

Purified CD4+CD25− (2 × 105 cells per well) and/or CD4+CD25+ (5 × 104 cells per well) T cells were stimulated with αCD3-bead (2 × 105 particles per well) and Fc-GITR-L (1 μg ml−1) fusion protein in round-bottom 96-well plate for 72 h. Supernatants were collected and used for measuring IL-2 concentration by ELISA (BD Biosciences).

Generation of BMDCs

Bone marrow cells were flushed from the femurs and tibias; 2 × 106 bone marrow cells were cultured in 10 ml of RPMI 1640 medium supplemented with 20 ng ml−1 of rGM-CSF and 20 ng ml−1 of rIL-4. Fresh medium was added in the culture on days 3 and 6. Non-adherent cells were used for activating CD4+CD25+ Treg.

Immunoblotting assay

Both wt and GITR−/− CD4+CD25+ Treg were pre-activated with 1 μg ml−1 of soluble αCD3ε in the presence of BMDCs for 48 h. Then, BMDCs were depleted with CD11C+ DC isolation kit (Miltenyi Biotec Inc.) and αCD3ε was washed off. After resting for 24 h in the presence of 10 ng ml−1 of rIL-2, cells were washed once with fresh RPMI medium and re-activated with αCD3ε in the presence or absence of Fc-GITR-L for 1 h. Whole-cell lysates were prepared by lysing the cells with RIPA buffer (50 mM Tris–HCl, pH 7.4; 150 mM NaCl; 1% Nonidet P-40; 0.5% sodium deoxycholate; 1 mM EDTA; 1 mM phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride; 1 mM dithiothreitol and one-hundredth volume of a protease inhibitor mixture) as described before (34). Cell lysates were separated by SDS–PAGE and subjected to immunoblot using the indicated antibodies.

In vivo administration of Fc-GITR-L to FoxP3-IRES-GFP mice

FoxP3-IRES-GFP mice of 3 weeks (C57BL/6 or BALB/c) were treated with IgG or Fc-GITR-L (200 μg per mouse per dose, 3–4 days apart for 2 or 4 weeks). We stopped administering Fc-GITR-L 4 days before thymus, spleen and mesenteric lymph node (MLN) were excised from the mice. Total cell numbers were counted using trypan blue. CD4+FoxP3+ frequencies were evaluated by FACS.

AAV vector preparation

AAV vector expresses hF.IX from the hepatocyte-specific ApoE enhancer/hepatocyte control region and human α1-antitrypsin promoter were as published (35). The expression cassette is flanked by AAV-2 inverted terminal repeats. AAV vectors (serotype 2) were produced by triple transfection of HEK-293 cells, purified by CsCl gradient centrifugation, filter-sterilized, and quantified by slot blot hybridization using standard protocols.

Suppression of immune response to hF.IX in hemophilia B mice

Fc-GITR-L (200 μg per mouse per dose) was injected intraperitoneally into hemophilia B (C3H/HeJ F9−/−) mice for a total of seven doses (given 3–4 days apart over a period of 1 month). After four injections, AAV-hF.IX (serotype 2, 1 × 1011 vector genome per mice) was administered via the portal vein. Levels of hF.IX antigen in plasma samples were measured by hF.IX-specific ELISA. Inhibitory antibodies to hF.IX were measured by the Bethesda assay, and activated partial thromboplastin time of plasma samples was measured using a fibrometer as published (33).

Statistical analysis

All data with statistical analysis were graphed and compared for significance using a two-tailed Student’s t-test with Prism 4 for Macintosh, Version 4.0c (GraphPad Software, Inc.).

Results

Engagement by Fc-GITR-L differentially induces proliferation of Treg and Teff

A purified Fc-GITR-L fusion protein generated in 293T cells with a molecular weight of 40 kD under reducing conditions and 92 kD under non-reducing conditions (Supplementary Figure S1A and S1B, available at International Immunology Online) was used for these studies. The molecular weight indicates that the disulfide bond in the hinge of the human Fc fragment dimerizes the fusion protein and that Fc-GITR-L is a dimer. This is a natural configuration of GITR-L as structural analyses show that mouse GITR-L forms a non-disulfide-bonded dimer (26, 27, 36). Fc-GITR-L does detect GITR on the surface of transfected 293F cells (Supplementary Figure S2A, available at International Immunology Online) and low levels of GITR on the surface of resting CD4+ T cells (Supplementary Figure S2B, available at International Immunology Online). As expected (21), upon overnight stimulation with αCD3ε or ConA, high levels of GITR are detected by Fc-GITR-L on the surface of wt CD4+ T cells but not on the surface of activated GITR−/− T cells (Supplementary Figure S2B, available at International Immunology Online). Additionally, freshly isolated CD4+FoxP3+ cells reacted stronger with Fc-GITR-L than CD4+FoxP3− cells (Supplementary Figure S2C, available at International Immunology Online) (9). Thus, the soluble dimer of GITR-L specifically interacts with GITR.

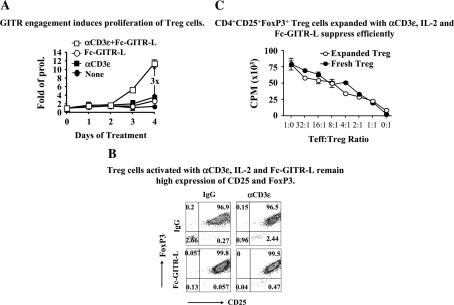

Next, Fc-GITR-L was used to further define the role of GITR as a co-stimulatory molecule on the surface of Treg. To this end, CD4+CD25+FoxP3+ cells were purified from the spleens of FoxP3-IRES-EGFP knock-in mice, either on the C57BL/6 or on the BALB/c background (31, 32). Cells were stimulated with combinations of Fc-GITR-L, IL-2 and αCD3ε and expansion was followed for 4 days by cell counting and flow cytometry. On day 3 of activation of FoxP3+ Treg with Fc-GITR-L, IL-2 and αCD3ε, proliferation became detectable and at day 4, the total cell number had increased by ∼11 times. In the presence of Fc-GITR-L, cells proliferated three times more than when incubated with αCD3 and IL-2. The number of FoxP3+ Treg only doubled upon culturing in the presence of combinations of IL-2 and αCD3ε or IL-2 and Fc-GITR-L (Fig. 1A) (37). Fc-GITR-L, IL-2 and αCD3ε stimulated cells expressing high levels of FoxP3 and CD25 indicating a stable phenotype (Fig. 1B). Importantly, the expanded FoxP3+ Treg suppressed proliferation of CD4+CD25− Teff as effectively as freshly isolated FoxP3+ Treg (Fig. 1C).

Fig. 1.

In vitro expanded CD4+CD25+FoxP3+ Treg suppress efficiently. (A) GITR engagement induces proliferation of Treg. CD4+CD25+FoxP3+ Treg were isolated from splenocytes of FoxP3-IRES-EGFP knock-in C57BL/6 mice by flow cytometry. Cells (105 cells per well) were then stimulated with IL-2 (10 ng ml−1), αCD3ε-beads (2 × 105 particles per well) and Fc-GITR-L (1 μg ml−1) in a round-bottom 96-well plate for 3 days. On days 1, 2, 3 and 4, trypan blue-negative cells were counted. Cell numbers were normalized to the starting number for folds of proliferation. The data, presented as mean ± SEM, are results of three independent experiments. (B) Treg activated with αCD3ε, IL-2 and Fc-GITR-L remain highly expressed on CD25 and FoxP3. Treg were stimulated as in (A). After a 4-day activation, cells were stained with αCD4, αCD25 and DAPI and analyzed by FACS. CD4+DAPI− T cells were gated for analyzing the expression of FoxP3 (as judged by reporter gene GFP) and CD25. The data are representative of three independent experiments. (C) CD4+CD25+FoxP3+ Treg expanded with αCD3ε, IL-2 and Fc-GITR-L suppress efficiently; 2 × 105 of Teff were mixed with different doses of freshly isolated Treg or Treg expanded with Fc-GITR-L, αCD3ε-bead and IL-2 for 4 days. Cell mixtures were activated with αCD3ε-bead (2 × 105 particles per well) in a round-bottom 96-well plate for 3 days; 1 μCi of [3H]-labeled thymidine was added in each sample in the last 18 h before cells were harvested for analyzing thymidine incorporation with beta plate reader. The data, presented as mean ± SEM, are representative of three independent experiments.

Proliferation of CD4+CD25−FoxP3− Teff with Fc-GITR-L, IL-2 and αCD3ε was 1.5 times that of proliferation in the presence of IL-2 and αCD3ε (Fig. 2A). Stimulation with IL-2 and αCD3ε of CD4+CD25−FoxP3− Teff resulted in a much faster proliferation than that of Treg (Fig. 2A). The Teff number was significantly reduced in the presence of IL-2 alone, most likely due to the lack of CD25 expression in their surface. Importantly, the Teff cells did not convert to FoxP3+ upon stimulation under these conditions (Fig. 2B). Taken together, the data show that Fc-GITR-L in concert with IL-2 and αCD3ε induces proliferation of all CD4+ cells. FoxP3+ cells, however, react stronger than FoxP3− cells to ligation of GITR.

Fig. 2.

Fc-GITR-L does not induce FoxP3 expression in CD4+CD25−FoxP3− T cells. (A) GITR engagement marginally enhances proliferation of Teff cells. CD4+CD25−FoxP3− Teff were isolated from splenocytes of C57BL/6 FoxP3-IRES-EGFP knock-in mice by flow cytometry and were stimulated as described in Fig. 1. Live cells were counted after trypan blue staining. Cell numbers were normalized to the starting number for folds of proliferation. The data, presented as mean ± SEM, are results of three independent experiments. (B) Teff cells activated with αCD3ε, IL-2 and Fc-GITR-L express CD25 but not FoxP3. CD4+CD25−FoxP3− Teff were stimulated as in (A). After a 4-day activation, cells were stained with αCD4, αCD25 and DAPI and analyzed by FACS. CD4+DAPI− T cells were gated for analyzing the expression of FoxP3 (as judged by reporter gene GFP) and CD25. The data are representative of three independent experiments.

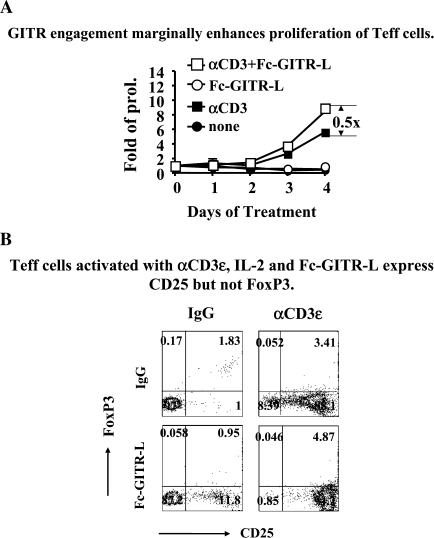

Fc-GITR-L provides a co-stimulatory signal for proliferation of Treg

To further define the role of GITR as a co-stimulatory molecule on the surface of Treg, the IL-2 dependence was quantitated in [3H]-thymidine uptake assays. To this end, CD4+CD25+ cells purified from the spleens of wt mice were stimulated with αCD3ε-coupled beads in the presence or absence of Fc-GITR-L and increasing concentrations of IL-2. In the presence of 7 ng ml−1 of IL-2, αCD3ε-coupled beads and Fc-GITR-L induced the highest level of proliferation of wt natural Treg (Fig. 3A). In the absence of αCD3, Fc-GITR-L and IL-2 induced a substantial activation (Fig. 3A). Conversely, in the absence of IL-2, a combination of αCD3ε-coupled beads and 1 μg Fc-GITR-L induced a low level of proliferation of wt Treg, while control GITR−/− Treg do not respond (Fig. 3B). When the same Treg were re-stimulated with a combination of Fc-GITR-L and αCD3ε, IκBα was almost completely degraded after 1 h (Fig. 3C). This suggests a rapid activation of the canonical NF-κB pathway by engagement of GITR, consistent with our other observations (24, 38).

Fig. 3.

GITR ligation induces Treg proliferation and IκBα degradation. (A) Fc-GITR-L enhances the proliferation of wt Treg in the presence of IL-2. Wt Treg (2 × 105 cells per well) were stimulated with combinations of Fc-GITR-L (1 μg ml−1), αCD3ε-bead (2 × 105 particles per well) and increasing doses of IL-2 in a round-bottom 96-well plate for 3 days; 1 μCi of [3H]-thymidine was added in each sample in the last 18 h before cells were harvested onto the membrane. Thymidine incorporation was analyzed with a beta plate reader. The data, presented as mean ± SEM, are representative of three independent experiments. (B) Fc-GITR-L induces proliferation of wt Treg but not GITR−/− Treg in the absence of IL-2. Wt or GITR−/− Treg (2 × 105 cells per well) were stimulated with αCD3-beads (2 × 105 particles per well) in the presence or absence of Fc-GITR-L (1 μg ml−1) in a round-bottom 96-well plate for 3 days; 1 μCi of [3H]-thymidine was added in each sample in the last 18 h before cells were harvested onto the membrane. Thymidine incorporation was analyzed with a beta plate reader. The data, presented as mean ± SEM, are representative of three independent experiments. (C) Fc-GITR-L induces degradation of IκBα in wt Treg but not GITR−/− Treg. Both wt and GITR−/− Treg were pre-activated with 1 μg ml−1 of soluble αCD3ε in the presence of BMDCs for 2 days. After resting for 24 h by depleting the BMDCs and washing off the αCD3ε, cells were re-activated with αCD3ε and Fc-GITR-L for 1 h. Cell lysates were separated by SDS–PAGE and immunoblotted with anti-IκBα. The same membrane was reprobed with anti-β-actin as a loading control. The data are representative of at least three independent experiments. Statistical significance was determined by the two-tailed Student’s t-test. *P < 0.05; **P < 0.01; ***P < 0.005.

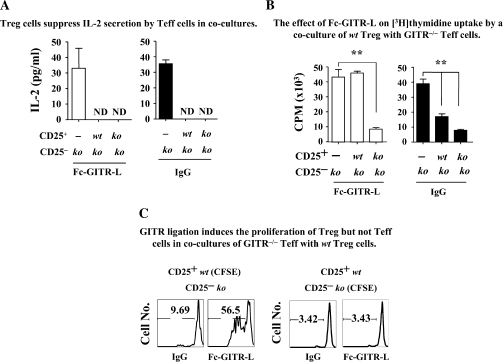

Treg expanded by Fc-GITR-L in cocultures with Teff are functionally competent

Previous studies suggested that αGITR or GITR-L might inhibit the suppressor activity of Treg when cocultured with CD4+CD25− Teff. It was hypothesized that this could be caused either by abrogating Treg-mediated suppression or by rendering the Teff resistant to Treg (5, 24, 25). These interpretations contrasted with our observations in Fig. 1, which indicate that expansion of Treg in the presence of Fc-GITR-L did not abrogate the suppressor function of Treg. To further rule out that a continuous ligation of GITR molecules could attenuate Treg suppression, we cocultured Treg and Teff purified from either wt or GITR−/− mice. Combinations of wt and GITR−/− Treg and Teff were then activated with αCD3-beads in the presence or absence of Fc-GITR-L and suppression was assessed by IL-2 production, [3H]-thymidine uptake or CFSE dilution (2, 25, 39).

When IL-2 secretion by GITR−/− Teff induced by αCD3-beads was used as the readout for suppressor activity, both wt and GITR−/− Treg suppressed equally well (Fig. 4A, right panel). Furthermore, when Fc-GITR-L was added to the cocultures of Teff and Treg, suppression was not abrogated. However, when [3H]-thymidine incorporation in the cocultures of Treg and GITR−/− Teff was used as a readout, proliferation increased in the presence of Fc-GITR-L, if wt Treg were used (Fig. 4B, left panel). There were two interpretations for this Fc-GITR-L-induced [3H]-thymidine uptake in the coculture, namely proliferation of the wt Treg or abrogation of the suppressor activity.

Fig. 4.

Fc-GITR-L engagement does not affect Treg suppressor functions and also induces Treg proliferation in cocultures with Teff cells. (A) Treg suppress IL-2 secretion by Teff cells in cocultures. Cocultures of GITR−/− Teff (2 × 105 cells per well) with either wt or GITR−/− Treg (4 × 104 cells per well) were stimulated with αCD3-beads (2 × 105 particles per well) in the presence or absence of Fc-GITR-L for 3 days. Supernatants were collected for measuring IL-2 by ELISA. ND, not detectable. (B) The effect of Fc-GITR-L on [3H]-thymidine uptake by a coculture of wt Treg with GITR−/− Teff. CD4+CD25− Teff (GITR−/−) and CD4+CD25+ Treg (wt or GITR−/−) were mixed and activated with αCD3-bead for 72 h; 1 μCi of [3H]-labeled thymidine was added in each sample in the last 18 h before cells were harvested for analyzing thymidine incorporation with beta plate reader. Teff were used at 2 × 105 cells per well. Treg were 5 × 104 cells per well. Anti-CD3-beads were 2 × 105 particles per well. Fc-GITR-L was 1 μg ml−1. In these assays, a 96-well round-bottom plate was used. (C) GITR ligation induces the proliferation of Treg but not Teff in cocultures of GITR−/− Teff with wt Treg. CD4+CD25− Teff (GITR−/−) and CD4+CD25+ Treg (wt) were purified by FACS and stained with CFSE. GITR−/− Teff and wt Treg (with or without CFSE) were mixed at 8:1 ratio and stimulated with αCD3-bead in the presence or absence of Fc-GITR-L. Three days later, CFSE-positive cells were gated for evaluating cell proliferation. The data, presented as mean ± SEM, are representative of three independent experiments. Statistical significance was determined by the two-tailed Student’s t-test. **P < 0.01.

To determine which interpretation was correct, cocultures of FACS-purified wt Treg and GITR−/− Teff in which one of the subsets was first loaded with CFSE were set up. As shown in (Fig. 4C) (left panel), Fc-GITR-L induced the proliferation of CFSE-labeled wt Treg in a culture with unlabeled GITR−/− Teff. This demonstrated a direct effect on Treg proliferation, in agreement with the single-cell experiments of Figs 1–3. Because Fc-GITR-L did not affect proliferation of CFSE-labeled GITR−/− Teff cells that were cultured with unlabeled wt Treg (Fig. 4C, right panel), we concluded that Fc-GITR-L did not abrogate Treg suppression.

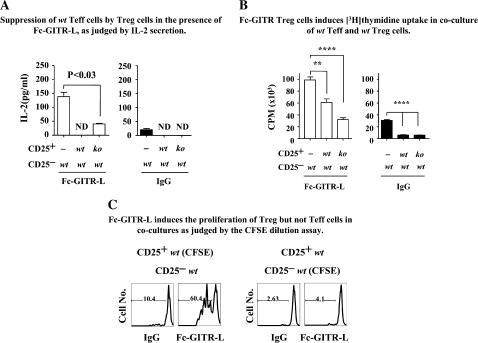

Fc-GITR-L does not render Teff refractory to Treg suppression

We next determined whether Fc-GITR-L-induced triggering of GITR on wt Teff rendered them refractory to Treg suppression. To address this question, cocultures of wt Teff with either wt or GITR−/− Treg were activated with αCD3-beads in the presence or in the absence of Fc-GITR-L and suppression was assessed by IL-2 production, [3H]-thymidine uptake or CFSE.

When IL-2 production by wt Teff was used as the readout for suppression activity, both wt and GITR−/− Treg suppressed equally well (Fig. 5A, right panel) in the absence of Fc-GITR-L. The IL-2 production by wt Teff increased by about five times in the presence of Fc-GITR-L (Fig. 5A, left panel), suggesting that Fc-GITR-L ligation of GITR on wt Teff triggers a strong activation of transcription and/or translation of the IL-2 gene, consistent with previous reports (40). Fc-GITR-L-induced IL-2 production by wt Teff was significantly inhibited by both wt and GITR−/− Treg (Fig. 5A, left panel). Fc-GITR-L-induced IL-2 levels in cocultures of wt Teff and wt Treg were lower than that in wt Teff and GITR−/− Treg, suggesting that GITR ligation on Treg makes them more suppressive (Fig. 5A, left panel).

Fig. 5.

Fc-GITR-L does not affect the susceptibility of Teff cells to suppression by Treg. (A) Suppression of wt Teff cells by Treg in the presence of Fc-GITR-L, as judged by IL-2 secretion. Cocultures of wt Teff with either wt or GITR−/− Treg were stimulated with αCD3ε beads in the presence or absence of Fc-GITR-L in a 96-well round-bottom plate for 3 days. Supernatants were used to measure IL-2 production by ELISA. ND, not detectable. (B) Fc-GITR Treg induces [3H]-thymidine uptake in coculture of wt Teff and wt Treg. Wt Teff and Treg (wt or GITR−/−) were prepared and activated to analyze the T-cell proliferation by [3H]-labeled thymidine as described in Fig. 3A. (C) Fc-GITR-L induces the proliferation of Treg but not Teff in cocultures as judged by the CFSE dilution assay. FACS-purified wt Teff and wt Treg, in which one of the subset was labeled with CFSE, were cocultured at 8:1 ratio. After a 3-day activation with αCD3-bead with or without Fc-GITR-L, CFSE-positive cells were gated for evaluating cell proliferation. The data, presented as mean ± SEM, are representative of more than three independent experiments. Statistical significance was determined by the two-tailed Student’s t-test. ns, P > 0.05; *P < 0.05; **P < 0.01; ****P < 0.001.

When [3H]-thymidine uptake was used as the readout, the proliferation of wt Teff was equally well suppressed by both wt and GITR−/− Treg (Fig. 5B, right panel), consistent with the IL-2 production assay (Fig. 5A, right panel). Fc-GITR-L significantly induced the [3H]-thymidine uptake by wt Teff when Treg were not added (Fig. 5B, left panel). Fc-GITR-L-induced [3H]-thymidine uptake by wt Teff was inhibited by GITR−/− Treg (Fig. 5B, left panel), indicating that Fc-GITR-L ligation on wt Teff alone did not make them refractory to in vitro suppression by GITR−/− Treg. Although Fc-GITR-L-induced [3H]-thymidine uptake in coculture of wt Teff and wt Treg was higher than that in coculture of wt Teff and GITR−/− Treg, it was 40% lower than that of wt Teff alone (Fig. 5B, left panel), suggesting that triggering of GITR by Fc-GITR-L on both wt Teff and wt Treg may not cause proliferation of wt Teff cells.

The notion that wt Teff had not become refractory to suppression upon engagement with Fc-GITR-L was also supported by our CFSE dilution assay. FACS-purified wt Teff and wt Treg, in which one of the subsets was labeled with CFSE, were cocultured at 8:1 ratio and activated with αCD3-beads in the presence or in the absence of Fc-GITR-L for 3 days. As shown in (Fig. 5C) (left panel), Fc-GITR-L induced the proliferation of CFSE-labeled wt Treg in coculture with unlabeled wt Teff. This demonstrated a direct effect on wt Treg proliferation, consistent with the results in Figs 1–4. Because Fc-GITR-L did not induce the proliferation of CFSE-labeled wt Teff in coculture with unlabeled wt Treg (Fig. 5C, right panel), we conclude that Fc-GITR-L ligation on wt Teff does not allow them to escape the suppression by wt Treg.

Taken together, neither suppression by Treg nor susceptibility by Teff is diminished after engagement of GITR and Fc-GITR-L co-stimulation preferentially induced the proliferation of Treg.

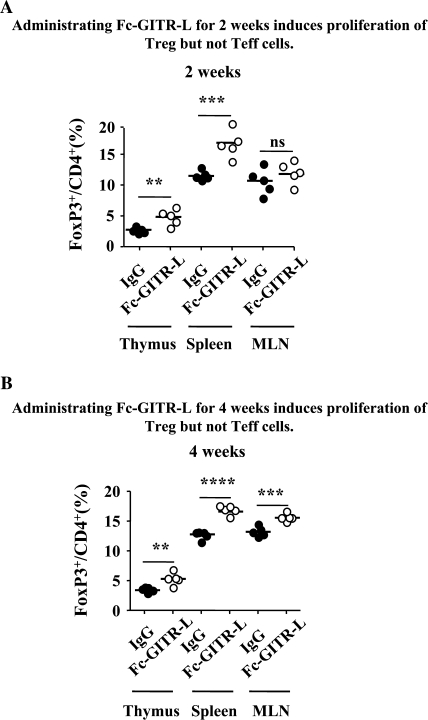

In vivo administration of Fc-GITR-L induces proliferation of CD4+FoxP3+ Treg but not CD4+FoxP3− Teff

As mentioned above, ligation of GITR induces stronger proliferation of functionally competent Treg in vitro. In order to study whether this represents the physiological function of GITR signaling in vivo, we injected Fc-GITR-L intraperitoneally into FoxP3-IRES-EGFP knock-in mice of C57BL/6 background (every 3–4 days for 2 or 4 weeks) in the absence of exogenous antigenic stimulation. The percentages of CD4+FoxP3+ Treg were significantly increased in the thymus and spleen after 2 weeks of Fc-GITR-L administration (Fig. 6A). After 4 weeks of continuous administration of Fc-GITR-L, the frequencies of CD4+FoxP3+ Treg were significantly induced in the thymus, spleen and MLN (Fig. 6B). However, the absolute numbers of CD4+ T cells in the thymus, spleen and MLN were not significantly increased by either 2-week (Supplementary Figure S3A, available at International Immunology Online) or 4-week (Supplementary Figure S3B, available at International Immunology Online) continuous Fc-GITR-L administration (Supplementary Figure S3, available at International Immunology Online). These results suggest that in the absence of exogenous antigenic stimulation, Fc-GITR-L administration specifically induces the proliferation of CD4+FoxP3+ Treg but not of CD4+FoxP3− Teff. Fc-GITR-L-mediated induction of CD4+FoxP3+ Treg was also observed in the BALB/c FoxP3-IRES-EGFP knock-in mouse strain (Supplementary Figure S4, available at International Immunology Online).

Fig. 6.

Fc-GITR-L induces in vivo proliferation of CD4+FoxP3+ but not CD4+FoxP3− cells. (A) Administering Fc-GITR-L for 2 weeks induces proliferation of Treg but not Teff. Fc-GITR-L or IgG control (200 μg per mouse per dose) was injected intraperitoneally into FoxP3-IRES-EGFP knock-in mice for 2 weeks (three doses, given 3–4 days apart). Administration of Fc-GITR-L was stopped 4 days before thymus, spleen and MLN were excised from the mice. Total cell numbers were counted by trypan blue-negative cells. CD4+FoxP3+ frequencies were evaluated by FACS. (B) Administering Fc-GITR-L for 4 weeks induces proliferation of Treg but not Teff. Fc-GITR-L or IgG control (200 μg per mouse per dose) was injected intraperitoneally into FoxP3-IRES-EGFP knock-in mice for 4 weeks (seven doses, given 3–4 days apart). Administration of Fc-GITR-L was stopped 4 days before thymus, spleen and MLN were excised from the mice. Total cell numbers were counted by trypan blue-negative cells. CD4+FoxP3+ Treg frequencies were evaluated by FACS. Each filled or open circle represents one mouse treated with IgG control or Fc-GITR-L, respectively. Statistical significance was determined by the two-tailed Student’s t-test. ns, P > 0.05; **P < 0.01; ***P < 0.005; ****P < 0.001.

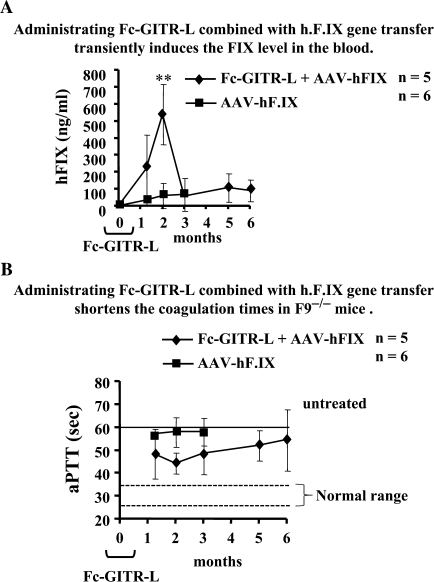

In vivo administration of Fc-GITR-L transiently suppresses immune responses to exogenous antigen upon AAV-mediated hepatic gene delivery

Although AAV2-mediated hepatic gene transfer induces sufficient immune tolerance to hF.IX in several strains of F9−/− mice, an immune response against exogenous hF.IX develops in F9−/− mice of C3H/HeJ background (41, 42). A recent detailed analysis demonstrated that systemic hF.IX expression in this strain is limited by CD8+ T-cell response that eliminates a portion of hF.IX-expressing hepatocytes and, by formation of inhibitory antibodies (inhibitors), albeit that this immune response is substantially weaker compared with other routes of antigen administration/expression (33). Here, we tested whether the induction of CD4+FoxP3+ Treg by in vivo Fc-GITR-L administration could suppress the response, thereby augmenting therapy, in this strain of hemophilia B mice. Consistent with our previous findings (33), C3H/HeJ F9−/− mice expressed only low levels of hF.IX following gene transfer and developed inhibitors of 4–11 Bethesda unit (BU) by 3 months (Fig. 7A and data not shown). In contrast, administration of Fc-GITR-L (every 3–4 days for 4 weeks) combined with gene transfer (which was performed after the fourth Fc-GITR-L injection) directed substantially higher levels of hF.IX expression at 1- and 2-month time points (Fig. 7A). However, expression decreased to the low levels seen in control mice by 3 months (Fig. 7A). In agreement with these data, coagulation times were most shortened by 2 months, i.e. the peak of hF.IX expression, but then gradually increased. As shown in (Fig. 7B), the coagulation time was normally >60 s in untreated F9−/− mice and ∼25–35 s in wt mice (42). The control mice that only received hF.IX gene transfer had marginal correction because of low-level expression (just <60 s on average). The mice that received hF.IX gene transfer and Fc-GITR-L administration had at least initially a more substantial correction. The coagulation time was ∼45 s at the second month, which was the shortest during the whole process, consistent with the hF.IX ELISA levels. Somehow, the effect was transient, and hF.IX levels and clotting times were similar for both groups at late time points. Antibodies against hF.IX were only formed by 5–6 months in 4 of 5 mice (1–1.6 μg ml−1 serum), resulting in low-titer inhibitors of 2–3 BU in 2 of 5 mice by 6 months (data not shown).

Fig. 7.

Fc-GITR-L administration induces expression of hF.IX and reduces anti-coagulation factors in AAV2-mediated FIX transfer to C3H/HeJ hemophilia B mice. (A) Administering Fc-GITR-L combined with hF.IX gene transfer transiently induces the FIX level in the blood. Blood was collected from C3H/HeJ F9−/− mice that received hepatic gene transfer alone with the AAV-hF.IX vector (filled squares, n = 6) or combined gene transfer with Fc-GITR-L administration (filled diamonds, n = 5) at different time points. Human F.IX level in the blood was measured by ELISA. (B) Administering Fc-GITR-L combined with h.F.IX gene transfer shortens the coagulation times in F9−/− mice. Blood was collected from C3H/HeJ F9−/− mice that received hepatic gene transfer alone with the AAV-hF.IX vector (filled squares, n = 6) or combined gene transfer with Fc-GITR-L administration (filled diamonds, n = 5) at different time points. Activated partial thromboplastin time (aPPT) of plasma samples was measured using a fibrometer. The data are represented as mean ± SEM. Statistical significance was determined by the two-tailed Student's t-test. **P < 0.01.

Discussion

In an effort to dissect the influence of GITR signaling on the regulation of immune responses, we produced a fusion protein composed of the extracellular domain of mouse GITR-L instead of using the αGITR mAb. We expected that GITR ligation with Fc-GITR-L would represent the natural condition better than ligation with an mAb and would have a longer in vivo life span than the soluble form of GITR-L that was previously published (24). In order to eliminate the need for other co-stimulatory molecules, αCD3ε-conjugated beads were used as APC surrogates, allowing us to focus on the influence of GITR signaling on T-cell responses. Consistent with previous studies (5, 24, 25, 30), our results confirm that GITR functions as a co-activator for both Teff and Treg when they are cultured separately. GITR ligation does not induce the conversion between FoxP3+ Treg and FoxP3− Teff. CD4+CD25+FoxP3+ Treg expanded with IL-2, αCD3ε and Fc-GITR-L retain the suppressive activity in vitro.

However, when combinations of Teff with Treg purified from either wt or GITR−/− mice were activated with αCD3ε, Fc-GITR-L co-activation only induced proliferation of Treg but not Teff. This demonstrates that a continuous triggering of GITR on wt Teff cells does not allow them to escape suppression by Treg and triggering of GITR on wt Treg does not attenuate their suppression capability in vitro but induces proliferation of functionally competent Treg.

Consistent with the in vitro proliferation and suppression assay results, in vivo administration of Fc-GITR-L continuously for 2 weeks and 4 weeks significantly induced the CD4+FoxP3+ Treg ratio but not the absolute number of CD4+ T cells in the thymus, spleen and MLN. Administration of Fc-GITR-L (every 3–4 days for 4 weeks), combined with AAV-hF.IX-targeted hepatocyte-specific expression of hF.IX in F9−/− mice of C3H/HeJ background, substantially induced higher levels of hF.IX expression and shortened the coagulation times at 1- and 2-month time points. These results indicate that Fc-GITR-L-induced CD4+FoxP3+ Treg are functionally competent and may play a role in inhibiting the elimination of hF.IX-expressing hepoatocytes and the formation of inhibitory antibodies.

The data from both the in vitro proliferation and suppression assays and the AAV-hF.IX gene transfer mouse model strongly argue that GITR signaling in vivo is more likely to enhance rather than break immune tolerance. van Olffen et al. (40) reported that the number of Treg is significantly increased in a CD19 promoter-driven GITR-L transgenic (Tg) mice model. Consistent with the increased number and frequency of Treg, the GITR-L Tg mice show delayed onset of EAE induction and milder disease activity scores.

In support of this notion, Fc-GITR-L co-stimulation triggers significant induction of IL-2 production by wt Teff cells (Fig. 5A). It has been well accepted that IL-2 is important for the hematopoiesis and function of Treg. Mice lacking IL-2 or components of the IL-2 receptor (IL-2Rα and IL-2Rβ) succumb to an aggressive lymphoproliferation and severe autoimmune symptoms (43–45). Fc-GITR-L-induced IL-2 production by Teff cells may cause the increased Treg frequency in vivo. GITR−/− mice, however, have normal FoxP3+ Treg numbers (data not shown) and show no sign of autoimmune diseases, suggesting that GITR is dispensable for IL-2 production.

The concept that GITR signaling might break immune tolerance was based on the application of a widely used anti-GITR (DTA-1) mAb generated by Dr Sakaguchi's laboratory. We also compared the functional activity between Fc-GITR-L fusion protein and DTA-1. Both of them show a similar co-stimulatory ability in inducing the proliferation of Teff and Treg by an in vitro assay (data not shown). In contrast to the increasing FoxP3+ Treg in the presence of Fc-GITR-L, in vivo administration of DTA-1 results in a decreased FoxP3+ Treg percentage in two different models, which ultimately breaks the tolerance and induces the immune response (5, 46). These results suggest that the mAb DTA-1 and Fc-GITR-L may behave differently in vivo due to their differential affinities to the mouse complementary system. Application of DTA-1 may partially deplete the FoxP3+ Treg before the expansion of this population, which activates the immune response against cancer or exogenous protein. Alternatively, Fc-GITR-L can relay a positive signal to induce proliferation of functionally competent Treg rather than cause their depletion, which may be applied for the induction of tolerance.

GITR-L is present on a variety of cells, including B cells, mature and immature dendritic cells (DCs) (23, 25). The expression of GITR is also not only confined to T cells (47). The abundant expression pattern and the bidirectional communication utilized by GITR-L–GITR interaction will undoubtedly increase the complexity for the investigation of GITR function. Administration of Fc-GITR-L may also block the reverse signaling through GITR-L in plasmacytoid DCs, which was reported to activate an indoleamine-2,3-dioxygenase-dependent pathway to inhibit immune response in an allergy model (48). If administering Fc-GITR-L just blocks the reverse signaling through GITR-L in plasmacytoid dendritic cell, it should induce an immune response rather than induce tolerance against the liver-expressed hF.IX by AAV-2 vector in the C3H/HeJ F9−/− strain. So, it is most likely that signaling through GITR, but not though GITR-L, causes the expansion of CD4+FoxP3+ Treg and the subsequent tolerance induction.

Taken together, the results clearly argue the hypothesis that GITR ligation on Teff and/or Treg with GITR expression induces Teff cell proliferation and breaks immune tolerance to foreign antigens. In contrast, GITR ligation preferentially causes the expansion of Treg both in vitro as well as in vivo without breaching their suppressive capability, which may be applied for tolerance induction although the conditions need to be optimized.

Supplementary data

Supplementary Figures S1–S4 are available at International Immunology Online.

Funding

National Institutes of Health (P01 HC078810 to C.T.).

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr C. Riccardi and Dr P. P. Pandolfi for generously sharing the GITR−/− mice and Dr V. Kuchroo for providing the C57BL/6 FoxP3-IRES-GFP reporter mice.

References

- 1.Takahashi T, Kuniyasu Y, Toda M, et al. Immunologic self-tolerance maintained by CD25+CD4+ naturally anergic and suppressive T cells: induction of autoimmune disease by breaking their anergic/suppressive state. Int. Immunol. 1998;10:1969. doi: 10.1093/intimm/10.12.1969. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Thornton AM, Shevach EM. CD4+CD25+ immunoregulatory T cells suppress polyclonal T cell activation in vitro by inhibiting interleukin 2 production. J. Exp. Med. 1998;188:287. doi: 10.1084/jem.188.2.287. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Mottet C, Uhlig HH, Powrie F. Cutting edge: cure of colitis by CD4+CD25+ regulatory T cells. J. Immunol. 2003;170:3939. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.170.8.3939. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.McHugh RS, Shevach EM. Cutting edge: depletion of CD4+CD25+ regulatory T cells is necessary, but not sufficient, for induction of organ-specific autoimmune disease. J. Immunol. 2002;168:5979. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.168.12.5979. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Shimizu J, Yamazaki S, Takahashi T, Ishida Y, Sakaguchi S. Stimulation of CD25(+)CD4(+) regulatory T cells through GITR breaks immunological self-tolerance. Nat. Immunol. 2002;3:135. doi: 10.1038/ni759. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kohm AP, Carpentier PA, Anger HA, Miller SD. Cutting edge: CD4+CD25+ regulatory T cells suppress antigen-specific autoreactive immune responses and central nervous system inflammation during active experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis. J. Immunol. 2002;169:4712. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.169.9.4712. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Liu Y, Teige I, Birnir B, Issazadeh-Navikas S. Neuron-mediated generation of regulatory T cells from encephalitogenic T cells suppresses EAE. Nat. Med. 2006;12:518. doi: 10.1038/nm1402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Yu P, Gregg RK, Bell JJ, et al. Specific T regulatory cells display broad suppressive functions against experimental allergic encephalomyelitis upon activation with cognate antigen. J. Immunol. 2005;174:6772. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.174.11.6772. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ono M, Shimizu J, Miyachi Y, Sakaguchi S. Control of autoimmune myocarditis and multiorgan inflammation by glucocorticoid-induced TNF receptor family-related protein(high), Foxp3-expressing CD25+ and CD25- regulatory T cells. J. Immunol. 2006;176:4748. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.176.8.4748. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ermann J, Hoffmann P, Edinger M, et al. Only the CD62L+ subpopulation of CD4+CD25+ regulatory T cells protects from lethal acute GVHD. Blood. 2005;105:2220. doi: 10.1182/blood-2004-05-2044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Zhao D, Zhang C, Yi T, et al. In vivo-activated CD103+CD4+ regulatory T cells ameliorate ongoing chronic graft-versus-host disease. Blood. 2008;112:2129. doi: 10.1182/blood-2008-02-140277. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Walker LS, Chodos A, Eggena M, Dooms H, Abbas AK. Antigen-dependent proliferation of CD4+ CD25+ regulatory T cells in vivo. J. Exp. Med. 2003;198:249. doi: 10.1084/jem.20030315. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Klein L, Khazaie K, von Boehmer H. In vivo dynamics of antigen-specific regulatory T cells not predicted from behavior in vitro. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 2003;100:8886. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1533365100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Vignali D. How many mechanisms do regulatory T cells need? Eur. J. Immunol. 2008;38:908. doi: 10.1002/eji.200738114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wildin RS, Smyk-Pearson S, Filipovich AH. Clinical and molecular features of the immunodysregulation, polyendocrinopathy, enteropathy, X linked (IPEX) syndrome. J. Med. Genet. 2002;39:537. doi: 10.1136/jmg.39.8.537. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hori S, Nomura T, Sakaguchi S. Control of regulatory T cell development by the transcription factor Foxp3. Science. 2003;299:1057. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wildin RS, Freitas A. IPEX and FOXP3: clinical and research perspectives. J. Autoimmun. 2005;25(Suppl):56. doi: 10.1016/j.jaut.2005.04.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Itoh M, Takahashi T, Sakaguchi N, et al. Thymus and autoimmunity: production of CD25+CD4+ naturally anergic and suppressive T cells as a key function of the thymus in maintaining immunologic self-tolerance. J. Immunol. 1999;162:5317. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Fantini MC, Becker C, Monteleone G, Pallone F, Galle PR, Neurath MF. Cutting edge: TGF-beta induces a regulatory phenotype in CD4+CD25- T cells through Foxp3 induction and down-regulation of Smad7. J. Immunol. 2004;172:5149. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.172.9.5149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Coombes JL, Siddiqui KR, Arancibia-Carcamo CV, et al. A functionally specialized population of mucosal CD103+ DCs induces Foxp3+ regulatory T cells via a TGF-beta and retinoic acid-dependent mechanism. J. Exp. Med. 2007;204:1757. doi: 10.1084/jem.20070590. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Nocentini G, Giunchi L, Ronchetti S, et al. A new member of the tumor necrosis factor/nerve growth factor receptor family inhibits T cell receptor-induced apoptosis. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 1997;94:6216. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.12.6216. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kwon B, Yu KY, Ni J, et al. Identification of a novel activation-inducible protein of the tumor necrosis factor receptor superfamily and its ligand. J. Biol. Chem. 1999;274:6056. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.10.6056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Tone M, Tone Y, Adams E, et al. Mouse glucocorticoid-induced tumor necrosis factor receptor ligand is costimulatory for T cells. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 2003;100:15059. doi: 10.1073/pnas.2334901100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ji HB, Liao G, Faubion WA, et al. Cutting edge: the natural ligand for glucocorticoid-induced TNF receptor-related protein abrogates regulatory T cell suppression. J. Immunol. 2004;172:5823. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.172.10.5823. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Stephens GL, McHugh RS, Whitters MJ, et al. Engagement of glucocorticoid-induced TNFR family-related receptor on effector T cells by its ligand mediates resistance to suppression by CD4+CD25+ T cells. J. Immunol. 2004;173:5008. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.173.8.5008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Chattopadhyay K, Ramagopal UA, Brenowitz M, Nathenson SG, Almo SC. Evolution of GITRL immune function: murine GITRL exhibits unique structural and biochemical properties within the TNF superfamily. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 2008;105:635. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0710529105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Zhou Z, Tone Y, Song X, et al. Structural basis for ligand-mediated mouse GITR activation. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 2008;105:641. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0711206105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ronchetti S, Zollo O, Bruscoli S, et al. GITR, a member of the TNF receptor superfamily, is costimulatory to mouse T lymphocyte subpopulations. Eur. J. Immunol. 2004;34:613. doi: 10.1002/eji.200324804. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ramirez-Montagut T, Chow A, Hirschhorn-Cymerman D, et al. Glucocorticoid-induced TNF receptor family related gene activation overcomes tolerance/ignorance to melanoma differentiation antigens and enhances antitumor immunity. J. Immunol. 2006;176:6434. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.176.11.6434. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ronchetti S, Nocentini G, Riccardi C, Pandolfi PP. Role of GITR in activation response of T lymphocytes. Blood. 2002;100:350. doi: 10.1182/blood-2001-12-0276. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Haribhai D, Lin W, Relland LM, Truong N, Williams CB, Chatila TA. Regulatory T cells dynamically control the primary immune response to foreign antigen. J. Immunol. 2007;178:2961. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.178.5.2961. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Bettelli E, Carrier Y, Gao W, et al. Reciprocal developmental pathways for the generation of pathogenic effector TH17 and regulatory T cells. Nature. 2006;441:235. doi: 10.1038/nature04753. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Cao O, Hoffman BE, Moghimi B, et al. Impact of the underlying mutation and the route of vector administration on immune responses to factor IX in gene therapy for hemophilia B. Mol. Ther. 2009;17:1733. doi: 10.1038/mt.2009.159. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Liao G, Zhang M, Harhaj EW, Sun SC. Regulation of the NF-kappaB-inducing kinase by tumor necrosis factor receptor-associated factor 3-induced degradation. J. Biol. Chem. 2004;279:26243. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M403286200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Cooper M, Nayak S, Hoffman BE, Terhorst C, Cao O, Herzog RW. Improved induction of immune tolerance to factor IX by hepatic AAV-8 gene transfer. Hum. Gene Ther. 2009;20:767. doi: 10.1089/hum.2008.161. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Chattopadhyay K, Ramagopal UA, Mukhopadhaya A, et al. Assembly and structural properties of glucocorticoid-induced TNF receptor ligand: implications for function. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 2007;104:19452. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0709264104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Tang Q, Henriksen KJ, Bi M, et al. In vitro-expanded antigen-specific regulatory T cells suppress autoimmune diabetes. J. Exp. Med. 2004;199:1455. doi: 10.1084/jem.20040139. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Esparza EM, Arch RH. Glucocorticoid-induced TNF receptor, a costimulatory receptor on naive and activated T cells, uses TNF receptor-associated factor 2 in a novel fashion as an inhibitor of NF-kappa B activation. J. Immunol. 2005;174:7875. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.174.12.7875. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Thornton AM, Donovan EE, Piccirillo CA, Shevach EM. Cutting edge: IL-2 is critically required for the in vitro activation of CD4+CD25+ T cell suppressor function. J. Immunol. 2004;172:6519. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.172.11.6519. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.van Olffen RW, Koning N, van Gisbergen KP, et al. GITR triggering induces expansion of both effector and regulatory CD4+ T cells in vivo. J. Immunol. 2009;182:7490. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.0802751. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Mingozzi F, Liu YL, Dobrzynski E, et al. Induction of immune tolerance to coagulation factor IX antigen by in vivo hepatic gene transfer. J. Clin. Invest. 2003;111:1347. doi: 10.1172/JCI16887. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Cao O, Armstrong E, Schlachterman A, et al. Immune deviation by mucosal antigen administration suppresses gene-transfer-induced inhibitor formation to factor IX. Blood. 2006;108:480. doi: 10.1182/blood-2005-11-4668. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Sadlack B, Merz H, Schorle H, Schimpl A, Feller AC, Horak I. Ulcerative colitis-like disease in mice with a disrupted interleukin-2 gene. Cell. 1993;75:253. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(93)80067-o. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Suzuki H, Kundig TM, Furlonger C, et al. Deregulated T cell activation and autoimmunity in mice lacking interleukin-2 receptor beta. Science. 1995;268:1472. doi: 10.1126/science.7770771. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Willerford DM, Chen J, Ferry JA, Davidson L, Ma A, Alt FW. Interleukin-2 receptor alpha chain regulates the size and content of the peripheral lymphoid compartment. Immunity. 1995;3:521. doi: 10.1016/1074-7613(95)90180-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Cao O, Herzog RW. TLR3 signaling does not affect organ-specific immune responses to factor IX in AAV gene therapy. Blood. 2008;112:910. doi: 10.1182/blood-2008-02-137992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Nocentini G, Ronchetti S, Cuzzocrea S, Riccardi C. GITR/GITRL: more than an effector T cell co-stimulatory system. Eur. J. Immunol. 2007;37:1165. doi: 10.1002/eji.200636933. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Grohmann U, Volpi C, Fallarino F, et al. Reverse signaling through GITR ligand enables dexamethasone to activate IDO in allergy. Nat. Med. 2007;13:579. doi: 10.1038/nm1563. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.