Abstract

Multicellular organisms utilize cell-to-cell signals to build patterns of cell types within embryos, but the ability of fungi to form organized communities has been largely unexplored. Here we report that colonies of the yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae formed sharply divided layers of sporulating and nonsporulating cells. Sporulation initiated in the colony's interior, and this region expanded upward as the colony matured. Two key activators of sporulation, IME1 and IME2, were initially transcribed in overlapping regions of the colony, and this overlap corresponded to the initial sporulation region. The development of colony sporulation patterns depended on cell-to-cell signals, as demonstrated by chimeric colonies, which contain a mixture of two strains. One such signal is alkaline pH, mediated through the Rim101p/PacC pathway. Meiotic-arrest mutants that increased alkali production stimulated expression of an early meiotic gene in neighboring cells, whereas a mutant that decreased alkali production (cit1Δ) decreased this expression. Addition of alkali to colonies accelerated the expansion of the interior region of sporulation, whereas inactivation of the Rim101p pathway inhibited this expansion. Thus, the Rim101 pathway mediates colony patterning by responding to cell-to-cell pH signals. Cell-to-cell signals coupled with nutrient gradients may allow efficient spore formation and spore dispersal in natural environments.

IN metazoans, the hallmark of cell patterning is the establishment of sharp boundaries between cells of different fates. These boundaries are established and maintained by cell-to-cell signals. Even simple organisms can differentiate into several cell types, and these cell types can be organized into patterns within a larger community. For example, different cell types are organized within biofilms of the pathogenic yeast, Candida albicans (Baillie and Douglas 1999), and within the fruiting body of the slime mold, Dictyostelium discoideum (Kimmel and Firtel 2004; Strmecki et al. 2005). However, in most cases communities of microorganisms have not been shown to contain sharp boundaries between cell types, and the role if any of cell-to-cell signals in organizing cell types within fungal communities is not known.

The yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae may prove a genetically tractable model for fungal cell patterning (reviewed in Palkova and Vachova 2006). For example, periodic ammonia production during colony maturation can subdivide colonies into regions of cell growth and cell death (Vachova and Palkova 2005), colonies can form a skin-like cell layer on their surface (Vachova et al. 2009), and S. cerevisiae can form elaborate biofilm-like structures on agar surfaces (Reynolds and Fink 2001). Finally, yeast colonies preferentially contain sporulated cells at their edge (Purnapatre and Honigberg 2002). Localization of sporulated cells (termed asci) to the edge of colonies may be related to variations in nutrient microenvironments in different regions of the colony. For example, because growth inhibits sporulation (Colomina et al. 1999; Purnapatre et al. 2002), regions of the colony that are more depleted for nutrients might sporulate more efficiently.

In addition to the inhibition of sporulation under growth conditions, sporulation is activated only after fermentable carbon sources such as glucose are fully metabolized to nonfermentable carbon sources such as ethanol (reviewed in Honigberg and Purnapatre 2003; Kassir et al. 2003). Nonfermentable carbon sources stimulate sporulation directly, and metabolism of these carbon sources (via respiration) can also promote sporulation (Jambhekar and Amon 2008). Respiration causes an increase in the pH of the media as a result of cells secreting bicarbonate, and this increased pH may further stimulate sporulation in cultures (Ohkuni et al. 1998). Activation of sporulation by alkaline pH might occur through the highly conserved Rim101/PacC pathway (Penalva and Arst 2004), since this pathway activates transcription of many genes that respond to alkaline pH, including genes required for sporulation (Lamb and Mitchell 2003; Rothfels et al. 2005). However, a direct connection between alkaline pH and the Rim101 pathway in regulating sporulation has not been demonstrated. In the current study, we report on spatial patterns of sporulation that develop as colonies mature and the role of pH signals and the Rim101p pathway in regulating these patterns.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Strains and media:

Yeast strains (supporting information, Table S1) were constructed in the W303 background (Lee and Honigberg 1996) using standard methods (Kaiser et al. 1994); all strains compared in this study contained identical auxotrophies. Construction of genomic LacZ-fusion alleles has been described (Purnapatre et al. 2002). To maximize sporulation, colonies were grown on YNA medium [2% potassium acetate (pH 7.0), 0.25% yeast extract, 2% agar, supplemented with the minimal amino acids necessary to balance auxotrophies]. For experiments with cit1Δ mutants, strains were grown on SPS2-0.3 medium, which contains 0.3% glucose, 2% acetate, 0.25% ammonium sulfate, and 0.09% yeast nitrogen base (no amino acids or ammonium sulfate).

For measurement of LacZ expression, 0.04 mg/ml of X-gal was added to the media after autoclaving. For colonies inoculated from 0.5-μl spots, we employed YNA-2 media [6% potassium acetate (pH 7.0), 0.5% yeast extract, 2% agar], which decreased the time required for color development. To detect increased pH in the colony environment, 20 mg/liter of phenol red was added to YNA-2 medium before autoclaving. To measure the effect of pH on sporulation, 100 mm Tris–HCl at the indicated pH was added to the medium after autoclaving. To change the pH of YNA medium after 3 days of growth, a 6-mm well was made in the center of the plate using a Pasteur pipette and then filled with 130 μl of 1 m NaHPO4 buffer (pH 8.0). Colonies 2–4 cm from the well were analyzed for sporulation patterns. All other media are as described (Rose et al. 1990).

Chimeric colonies:

For colonies started from spot inoculations, here termed “spot colonies,” 1 × 105 cells were spotted on YNA-2 plates containing X-gal in a volume of 0.5 μl. For chimeric spot colonies, equal concentrations of each strain from overnight cultures were mixed, harvested, resuspended in H2O, and spotted as above, except as noted. Plates were incubated for 6 days and photographed (Olympus C-60 camera), and the digital images were analyzed as described below. To determine the proportion of reporter cells in chimeric colonies, we suspended colonies in water, spread ∼500 cells on YPD medium, and replica plated the resulting colonies to sporulation (SP3+) medium for 3 days before overlaying this medium with top agar containing X-gal and incubating for an additional 3 days (Serebriiskii et al. 2000).

Cryosections:

Colonies were grown for various times on YNA medium, and then an agar block containing one colony was frozen in OCT (detailed protocol in File S1). Twenty-micrometer sections were examined by light microscopy and quantified as described below.

Embedded sections:

To embed colonies for sectioning, we modified a previously described method (Scherz et al. 2001), with a major change being the substitution of Spurr's reagent as embedding medium, as described in detail in File S1. We determined the distribution of asci within a colony by superimposing nine equal-sized rectangles on the colony image and counting all cells in each rectangle (200–350 cells).

Image acquisition, processing, and statistical analysis:

All microscope images were captured using a Colorview II camera and AnalySIS software (SIS). Images in Figures 1, 2, and 4 were adjusted for brightness and contrast using Canvas 8. Quantification of prIME-LacZ expression in cryosections and spot colonies used Image J (National Institutes of Health) and a plug-in scripted for this study (color histogram). To achieve the greatest discrimination between blue and white regions in the images, we used the inverse of the signal in the red channel. For the cryosections, the red signal in each bin was subtracted from the bin with the highest red signal. For spot colonies, the signal was subtracted from the signal observed in a control (LacZ−) colony. All data is expressed as mean ± SEM.

Figure 1.—

Patterns of sporulation in wild-type colonies. Approximately 300 cells/plate were inoculated on YNA medium and grown for 8 days at 30°. Isolated colonies were sectioned and then examined by light microscopy. (A) Cross section of embedded colony. Bar, 0.4 mm. (B) Higher magnification of approximately the region indicated by a box in A. The region of sporulation is indicated by a bracket marked “S”, and the unsporulated region indicated by a bracket marked “U”. The arrow indicates representative tetrad asci (four spores) and the arrowhead indicates representative dyad asci (two spores). Bar, 25 μm.

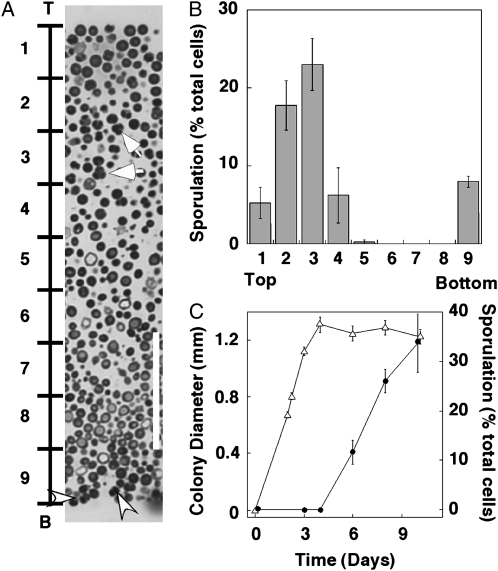

Figure 2.—

Sporulation initiates in central region of colonies. (A) A longitudinal section through the center of the colony, with the top (“T”) and bottom (“B”) of the colony indicated. To the left of the colony are 10 equally spaced marks that subdivide the colony into nine regions. Arrows indicate representative tetrad asci (four spores) and arrowheads indicate representative dyad asci (two spores). Bar, 50 μm. (B) Sporulation distribution in 6-day colonies. Bars represent percentage of sporulation in each of the nine regions of each image, as shown in A, from the top of the colony (left) to the bottom (right) (n = 4). (C) Timing of growth and sporulation in colonies. Colony diameter (open triangles) and percentage of sporulation (solid circles) are shown in colonies (SH1020) grown for various times on YNA medium (n = 5).

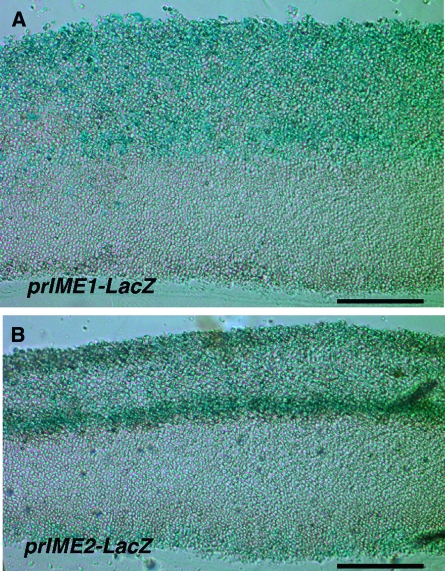

Figure 4.—

Expression of prIME1-LacZ and prIME2-LacZ in colonies. Colonies were sectioned after 12 days incubation on YNA medium containing X-gal. (A) prIME1-LacZ/ime1Δ strain (SH3830); (B) prIME2-LacZ/ime2Δ strain (SH3825). Bar, 0.1 mm.

RESULTS

Colonies contain a sharply delimited layer of sporulated cells:

Because sporulation occurs preferentially at the edge of colonies (Purnapatre and Honigberg 2002), we investigated the pattern of sporulation within colonies. For this purpose, we embedded and sectioned colonies incubated for 8 days on YNA medium (Figure 1A), a medium that allows both growth and sporulation. The most striking feature of these sections was a sharp boundary between an upper layer containing many tetrad and dyad asci and a lower layer completely devoid of asci (Figure 1B). This boundary provides one of the clearest examples of cell patterning within the fungal kingdom.

Sporulation initiates in the interior of colonies and at the agar surface:

The sharp boundary between sporulated and unsporulated regions led us to investigate the development of sporulation patterns after 4, 6, 8, and 10 days. Initially, four distinct layers of alternating sporulating and unsporulated regions were observed. For example, after 6 days, a thin layer of cells (3- to 5-cell widths) at the bottom of the colony contained a high frequency of tetrad and dyad asci (region 9 in Figure 2, A and B). Above this layer was a second layer (25- to 30-cell widths) that contained few if any asci (region 4–8 in Figure 2, A and B). Above this was a third layer, which was of variable size (5- to 10-cell widths) and contained many asci (region 2–3 in Figure 2, A and B). Finally, at the top of the colony was a layer of cells (5- to 10-cell widths) that contained relatively few spores (region 1–2 in Figure 2, A and B).

The interior region of sporulation expands as colonies mature while colony size remains constant:

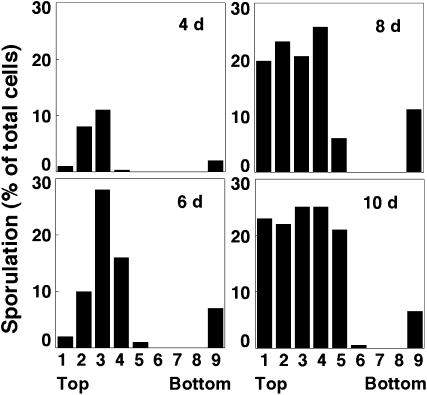

As colonies matured from 4 to 10 days, the interior layer of sporulated cells expanded upward to include the top of the colony (Figure 3). In contrast, the lower band of sporulated cells remained relatively narrow even after 10 days. Despite the expansion of the interior sporulation layer, the boundaries between the interior layer of unsporulated cells and the two surrounding layers of sporulated cells remained sharply defined, even after many days of incubation (Figure 3).

Figure 3.—

Time course of spore distribution in wild-type colonies. Wild-type colonies were sectioned after 4, 6, 8, or 10 days on YNA medium, and the spore distribution was analyzed as in Figure 2. A single colony in the height range of 0.8–1.0 mm was analyzed at each of the indicated times.

It is possible that the changes in sporulation patterns over time described in the previous paragraph result from ongoing cell growth in the colony. However, we found that the diameter of colonies remained constant after 4 days of incubation, and spores began to appear only after this time (Figure 2C). Similarly, the average number of cells per colony did not increase significantly from 4 to 6 days (P = 0.82, n = 3). Thus, it is unlikely that continued cell division plays an important role in the development of sporulation patterns in colonies.

Patterns of IME1-LacZ and IME2-LacZ expression in colonies:

Sporulation in specific regions of colonies could reflect nonuniform expression of sporulation regulators through the colony. Two key activators of sporulation, the Ime1p transcription factor and the Ime2p protein kinase, are not always coregulated, because IME2 expression requires Ime1p-independent signals as well as Ime1p (reviewed in Honigberg and Purnapatre 2003). To investigate the expression patterns of IME1 and IME2 within colonies, we examined colony cryosections expressing either prIME1-LacZ or prIME2-LacZ promoter fusions. For the initial experiments, we measured prIME1-LacZ in an ime1Δ background and prIME2-LacZ in an ime2Δ background to separate induction of these genes from autoregulation by their products (i.e., feedback). Strikingly, the pattern of expression for the two fusion genes was different (Figure 4). After 12 days incubation, both genes were expressed in a narrow band at the bottom of the colony, but prIME1-LacZ was also expressed through a broad region from the top to the center of the colony (Figure 4A), whereas prIME2-LacZ was mainly expressed in a narrow band in the center of the colony (Figure 4B). Because the overlap between IME1 and IME2 expression domains corresponds to the region of the colony in which asci were first observed, the interior layer of sporulation in colonies may reflect a region apical enough to express IME1 and basal enough to express IME2.

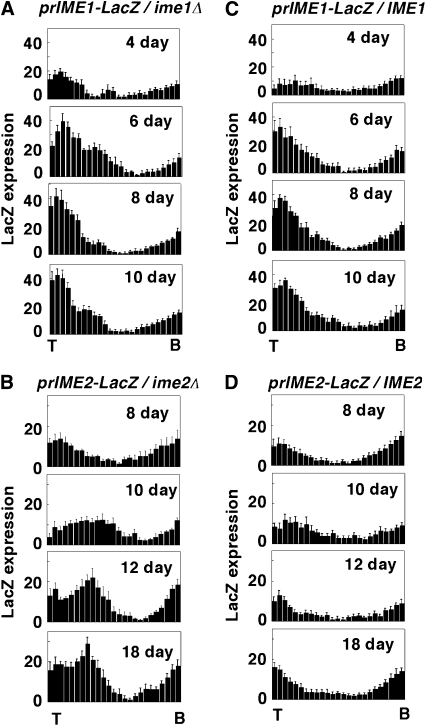

To investigate the development of prIME1-LacZ expression patterns over time, colonies were sectioned at 4, 6, 8, and 10 days. At 4 days, the prIME1-LacZ expression zone was limited to the top approximately one-fourth of the colony, but by 6 days this zone had expanded to include approximately the top half of the colony (Figure 5A). The same pattern of expression was observed in a prIME1-LacZ/IME1+ strain as in the prIME1-LacZ/ime1Δ strain (Figure 5C); this result indicates that Ime1p is not required for the pattern of IME1 transcription in colonies.

Figure 5.—

Time course of prIME1-LacZ and prIME2-LacZ expression patterns and requirement of Ime1p or Ime2p for these patterns. Colonies were incubated for the indicated times on YNA medium containing X-gal and sectioned, and the distribution of LacZ expression was quantified as described in materials and methods (n = 3). Each bar in the distribution from left to right represents the average LacZ expression level in one of 25 bins from the top of the colony (“T”) to the bottom (“B”). (A) prIME1-LacZ expression levels in a prIME1-LacZ/ime1Δ strain; (B) prIME2-LacZ expression levels in a prIME2-LacZ/ime2Δ strain; (C) prIME1-LacZ expression levels in prIME1-LacZ/IME1 strain; (D) prIME2-LacZ expression levels in a prIME2-LacZ/IME2 strain.

Expression of prIME2-LacZ peaked several days after prIME1-LacZ expression (compare Figure 5A and 5B). Interestingly, the LacZ expression pattern was different in prIME2-LacZ/IME2 strains relative to prIME2-LacZ/ime2Δ strains (compare Figure 5B and 5D). Both strains expressed LacZ at the bottom of the colony, but prIME2-LacZ/IME2 colonies (unlike prIME2-LacZ/ime2Δ colonies) expressed LacZ only transiently if at all in the interior of the colony. A likely explanation for this difference is that prIME2-LacZ/IME2 cells rapidly repress the fusion gene as they complete sporulation (negative feedback), whereas prIME2-LacZ/ime2Δ cells continue to express this gene. Thus, the ime2Δ background allowed visualization of the initial expression of prIME2-LacZ in a central region of the colony and also allowed accumulation of the fusion gene product to higher levels.

Signaling within colonies:

Higher expression of prIME2-LacZ in ime2Δ strains relative to IME2+ strains was apparent not only in cryosections (Figure 5, B and D) but also in whole colonies viewed from the top, including colonies inoculated from a drop of culture, termed spot colonies (Figure 6, A and B, compare i and ii; quantification shown in Figure 6C). This observation is consistent with previous studies showing that IME2 is regulated through negative feedback (Mitchell et al. 1990). Negative feedback occurs in part through cell autonomous mechanisms; for example, Ime2p targets Ime1p for degradation, thus repressing transcription of its own gene (Guttmann-Raviv et al. 2002). In addition, negative feedback in the context of colonies could proceed through cell nonautonomous mechanisms; for example, signals secreted by one cell could regulate sporulation in neighboring cells.

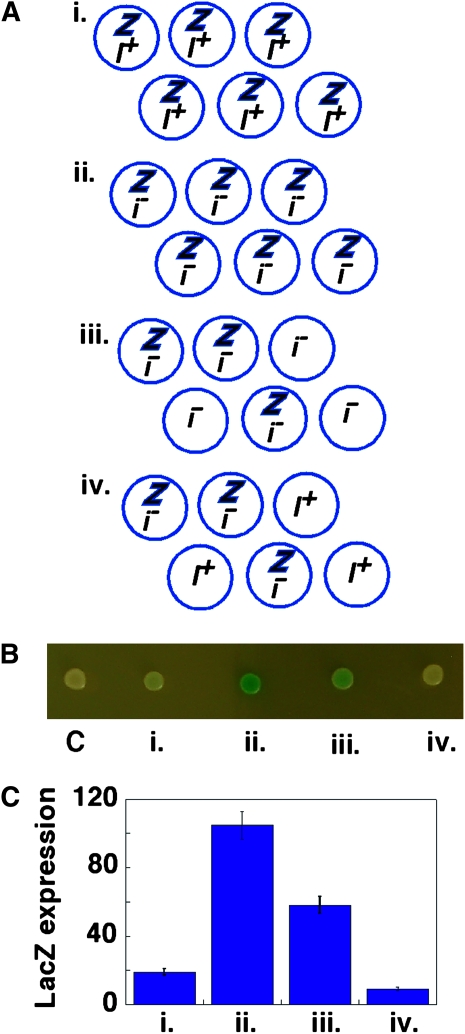

Figure 6.—

Cell-to-cell signaling regulates sporulation efficiency in colonies. (A) Diagram represents chimeric colony experiments, in which prIME2-LacZ expression was compared in four colonies containing the following genotypes: (i) prIME2-LacZ/IME2 (SH3824) alone, (ii) prIME2-LacZ/ime2Δ (SH3825) alone, (iii) equal numbers of prIME2-LacZ/ime2Δ and ime2Δ/ime2Δ (SH3883), and (iv) equal numbers of prIME2-LacZ/ime2Δ and IME2/IME2 (SH3881). Z, prIME2-LacZ/ime2Δ; i−, ime2Δ/ime2Δ; I+, IME2/IME2. (B) Colonies diagrammed in A grown for 6 days in YNA-2 medium. As a control (c), a LacZ− colony (SH3881) was also spotted. (C) Quantification of pr-IME2-LacZ expression in colonies as described above (n = 5).

To distinguish between cell autonomous and nonautonomous mechanisms, we mixed equal numbers of cells from two different strains (a “reporter” and a “signal” strain) and then spotted the mixture on plates to generate “chimeric” colonies. The reporter strain contained the prIME2-LacZ gene, whereas the signal strain lacked the fusion gene; so, if the genotype of the latter strain affects LacZ expression in the chimeric colony, then there must be communication between cells. We verified that the two strains in each chimera were present in an approximately 1:1 ratio after colony growth was complete by resuspending cells, plating for isolated colonies, and determining the genotype of these isolated colonies (see materials and methods). As a control, prIME2-LacZ/ime2Δ reporter cells were mixed with equal numbers of ime2Δ/ime2Δ signal cells (Figure 6, A–C, iii). In these control colonies, LacZ expression in this colony was approximately half that observed in colonies containing only prIME2-LacZ/ime2Δ cells, as would be expected from the 1:1 ratio of genotypes (Figure 6, A–C, compare ii and iii).

We next examined prIME2-LacZ expression in chimeric colonies containing equal mixtures of prIME2-LacZ/ime2Δ and IME2/IME2 cells (Figure 6, A–C, iv). If induction of sporulation is not affected by neighboring cells, then chimeras containing IME2/IME2 signal cells should be the same intensity blue as chimeras containing ime2Δ/ime2Δ signal cells. In contrast, we found that the IME2 chimeras expressed prIME2-LacZ at much lower levels than ime2Δ chimeras (Figure 6, A–C, compare iii and iv). Thus, the genotype of cells within a colony affects the phenotype of neighboring cells in the same colony (i.e., a cell nonautonomous mechanism). The same result was also obtained when an IME2+ reporter strain, IME2, was substituted for the prIME2-LacZ/ime2Δ strain (Figure S1 A). These results indicate that cell-to-cell signals regulate IME2 expression in colonies.

As an independent test of signaling within colonies, we measured spore formation in IME2 + ime2Δ chimeras. Although ime2Δ mutants do not sporulate, increasing the fraction of ime2Δ cells in these chimeras increased the efficiency of spore formation in the IME2 cells (Figure S1 B). Thus, intercellular signals regulate both IME2 expression and spore formation within colonies.

Alkaline pH as both cause and effect of sporulation in colonies:

As described in the Introduction, an alkaline pH environment has been implicated as both a by-product of sporulation and a signal that stimulates sporulation (Ohkuni et al. 1998). Thus, alkaline pH is a candidate for a cell-to-cell signal that regulates sporulation in colonies. To test this hypothesis, we first compared sporulation in wild-type spot colonies grown on medium buffered in the range pH 6.75–8.5. Sporulation in colonies showed a sharp dependence on pH in the range 7.5–8.5 (open triangles, Figure 7A). This result indicates that pH limits sporulation in colonies, consistent with the hypothesis that sporulating cells stimulate sporulation in neighboring cells by secreting alkali.

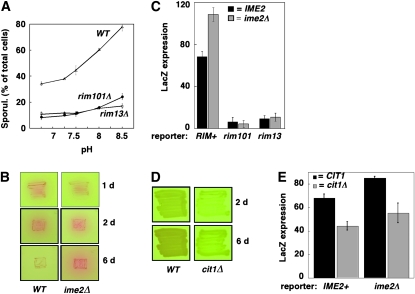

Figure 7.—

Alkaline pH, mediated through the Rim101p/PacC pathway, regulates colony sporulation efficiency. (A) Effect of pH on sporulation levels of wild type (SH3881), rim101Δ (SH4375), and rim13Δ (SH4415). Colonies were grown for 6 days on YNA-2 medium buffered to the indicated pH, and the percentage of cells in colonies that formed spores was assayed by microscopy after resuspending the complete colony (n = 3). (B) Production of alkali in wild type (WT) and ime2Δ mutant grown for 1, 2, or 6 days on YNA-2 media containing the pH indicator, phenol red. Red color in and around the patches of cells indicates an increased secretion of alkali from this strain. (C) RIM101 and RIM13 required to respond to neighboring cells. As indicated, chimeric colonies contained a prIME2-LacZ/ime2Δ reporter strain that is RIM+ (SH3825), rim101Δ (SH4378), or rim13Δ (SH4417) and signal strains that are either IME2+(SH3881) or ime2Δ (SH3883). LacZ expression was quantified after 12 days of growth to detect low rimΔ expression. Black bars indicate chimeras containing IME2+ signal strain, and gray bars indicate chimeras containing ime2Δ signal strain (n = 3). (D) CIT1 is required for alkali production. CIT1 (SH3881) and cit1Δ (SH4436) strains were patched to phenol red indicator medium containing both glucose and acetate (SPS2-0.3) to allow growth of the cit1Δ strain and photographed after 2 or 6 days of incubation. (E) CIT1 is required to stimulate sporulation in neighboring cells. As indicated, chimeric colonies contained prIME2-LacZ/IME2 reporter cells (SH3824) plus either the CIT1 or the cit1Δ strain described in D as signal cells. Black bars indicate chimeras containing CIT1+ signal strain, and gray bars indicate cit1Δ signal strain (n = 3). To ensure approximately equal numbers of cit1Δ and reporter cells in the mature chimeras, all chimeras were grown on medium containing both glucose and acetate (SPS2-0.3). Even in this medium, growth of the cit1Δ mutant is less than that of the wild type, so generation of mature chimeras containing approximately equal numbers of wild-type and cit1Δ strains required inoculating colonies with a 1:6 ratio of IME2 reporter to cit1Δ strain and a 1:10 ratio of ime2Δ reporter to cit1Δ strain; genotyping of 6-day chimeric colonies (see materials and methods) revealed that all contained from 40 to 50% reporter cells.

Given that the ime2Δ mutant stimulates sporulation in neighboring cells more than does the IME2+ control, we next asked whether this mutant produces more alkali than the control. For this purpose, we compared extracellular pH surrounding IME2 and ime2Δ strains using a pH indicator, phenol red. This indicator becomes increasingly red in the pH range 7.0–8.0. After a 1-day incubation, the mutant generated slightly less alkali than the wild type, consistent with higher induction of metabolic genes in sporulation-competent cells relative to sporulation-defective cells (Primig et al. 2000). In contrast, after a 2-day incubation, the pink color surrounding IME2 and ime2Δ patches was almost indistinguishable, and after a 6-day incubation, ime2Δ patches were noticeably redder than IME2 patches. Thus, the wild type initially produced more alkali than the mutant; but over the longer term, the mutant eventually produced more alkali (Figure 7B).

The ime2Δ mutant may produce more alkali than the wild type because IME2 specifically inhibits alkali production or because cells arrested in meiosis produce alkali for a longer period than the wild type. To address these possibilities, we measured alkali production in three other mutants arrested in meiosis: ime1Δ mutants, which like ime2Δ mutants arrest at the initiation of meiosis; hop2Δ mutants, which arrest early in pachytene (Leu et al. 1998); and ndt80Δ mutants, which arrest later in pachytene (Xu et al. 1995). As was seen for the ime2Δ mutant, after 6 days, the meiotic-arrest mutants produced significantly more alkali than the wild type (Figure S2 A). This latter result is consistent with the wild type ceasing alkali production once sporulation is complete; whereas the mutants, which fail to complete sporulation, continue to produce alkali. Interestingly, the hop2Δ and ndt80Δ mutants are somewhat less red on pH indicator plates than the ime1Δ and ime2Δ mutants (Figure 7B and Figure S2 A), so on the basis of this qualitative assay, it may be that mutants arrested early in meiosis produce more alkali than mutants arrested later in the program.

We next tested the ability of the meiotic-arrest mutants to stimulate sporulation in chimeras. Chimeric colonies containing any of these mutants as the signal strain induced prIME2-LacZ in the reporter strain to significantly higher levels than did a wild-type signal strain (Figure S2 B). Given the correlation between alkali production and the ability to stimulate sporulation, we propose that production of alkali during meiosis stimulates sporulation in neighboring cells.

Rim101p and Rim13p are required for response to alkali regulation of sporulation in colonies:

Because the Rim101p pathway responds to alkali and is required for sporulation, we tested the ability of mutants in the Rim101p pathway (rim101Δ and rim13Δ) to respond to neighboring cells. Rim101 is a transcriptional repressor that activates sporulation genes probably by repressing other transcriptional repressors, such as Nrg1 (Lamb and Mitchell 2003; Rothfels et al. 2005); Rim13p is a calpain-like protease required for processing and activation of Rim101p (Li and Mitchell 1997).

We measured the ability of rim101Δ prIME2-LacZ or rim13Δ prIME2-LacZ reporter strains to respond to neighboring cells in chimeric colonies (Figure 7C). As expected given the role of the Rim101p pathway in IME2 transcription, expression of the reporter gene in these rimΔ mutants (Figure 7C, bars 3–6) was considerably less than for RIM+ strains (Figure 7C, bars 1 and 2), although this expression was still easily detectable in the mutants after extended incubation. To measure the ability of the rimΔ reporter strains to respond to neighboring cells we compared expression of the fusion gene in chimeras containing an ime2Δ signal strain, which produces more alkali (Figure 7C, gray bars) to chimeras containing an IME2 signal strain, which produces less alkali (Figure 7C, black bars). We found that rimΔ reporter strains expressed the fusion gene to the same level regardless of whether the signal strain was IME2 or ime2Δ (Figure 7, compare bar 3 to bar 4 and bar 5 to bar 6). These results contrast with the control chimera containing a RIM+ signal strain, where even after extended incubation the signal strain is expressed to significantly higher levels when the signal strain is ime2Δ relative to when it is IME2+ (Figure 7C, compare bar 1 to bar 2, P < 0.003). Thus, rim101Δ and rim13Δ mutants are defective in responding to neighboring cells.

As a further test of the role of the Rim101p pathway in responding to alkaline pH, we measured the effect of pH on sporulation in rimΔ mutants. If the Rim101p pathway stimulates sporulation by responding to extracellular alkali, then rimΔ mutants should be defective in the stimulation of sporulation by alkaline pH. We found that rimΔ mutants sporulated to levels significantly less than the wild type, regardless of the pH (Figure 7A). More importantly, whereas sporulation efficiency increased dramatically for the RIM+ strain over the pH range tested, pH had little or no effect on sporulation efficiency for either rimΔ mutant. This result is consistent with the Rim101p pathway being required for cells to initiate sporulation in response to an alkaline pH environment.

Alkali signaling in colonies depends on respiration:

Sporulating cells secrete alkali, specifically bicarbonate, as a by-product of respiration. To examine the relationship between respiration and cell-to-cell signals, we examined a mutant, cit1Δ, that fails to respire on acetate medium (Kim et al. 1986). Thus, we grew cit1Δ and control strains on medium containing both glucose and acetate, which allows the mutant to grow but not to respire. Not surprisingly, we found that the wild type produced more alkali than did the cit1Δ mutant (Figure 7D). This result allowed an independent test of the role of alkali production in stimulating colony sporulation. To perform this test, chimeric colonies were prepared that contained a prIME2-LacZ/IME2 reporter strain and a signal strain that was either cit1Δ or CIT1+. We found that expression of the reporter was significantly lower (P < 0.02) in the cit1Δ chimeric colony than in the CIT1 chimera (Figure 7E, bars 1 and 2). Similar results (P < 0.04) were obtained when the reporter strain was prIME2-LacZ/ime2Δ rather than prIME2-LacZ/IME2 (Figure 7E, bars 3 and 4). Thus, the cit1Δ mutant is defective both in producing alkali and in stimulating sporulation in neighboring cells, consistent with our model that alkali produced by respiration is a cell-to-cell signal that stimulates sporulation in colonies.

Effect of alkaline pH and rim101Δ mutations on colony patterns:

To examine the effect of pH on colony sporulation patterns, colonies were grown on standard medium for 3 days, and then the pH of the medium was raised by addition of NaHPO4 buffer to a well created in the agar (see materials and methods). After an additional 3 days, the overall level of sporulation in these colonies was higher than in control colonies [26 ± 5% sporulation for the pH-adjusted colonies (n = 4) vs. 16 ± 1% sporulation for unadjusted colonies (n = 6)]. Notably, the region of sporulation in pH-adjusted colonies was much broader than in control colonies (compare Figure 8A and 8B). This result suggests that the upward expansion of the central region of sporulation in colonies is normally limited by extracellular pH.

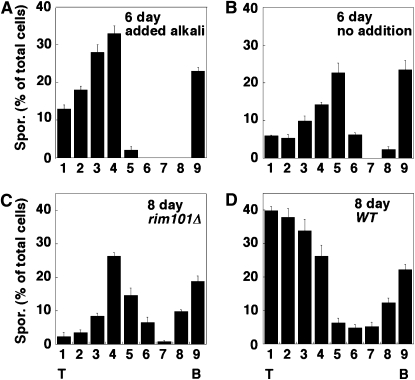

Figure 8.—

Effect of pH and Rim101p on sporulation patterns. (A and B) Addition of alkaline buffer expands sporulation region in colonies. Wild-type colonies (SH3881) were grown on YNA medium for 3 days under standard conditions before 1.0 m sodium phosphate buffer (pH 8.0) was added (A) or not (B) to a well at the center of the plate. Incubation was continued for 3 additional days, and then colonies were sectioned and analyzed for the distribution of sporulated cells in the colony as in Figure 2B (n = 3). (C and D) Rim101p is required for expansion of sporulation region in colonies. Either rim101Δ colonies (C) or wild-type colonies (D) were incubated for 8 days before colonies were sectioned and analyzed for the distribution of sporulated cells in the colony as in Figure 2B (n = 3).

We next measured colony sporulation patterns in a rim101Δ mutant. The pattern of sporulation in rim101Δ colonies, even after 8 days of incubation, was much different from that in the wild type. In particular, the region of sporulation in the mutant colony was limited to a narrow central region of the colony rather than extending through the entire top half of the colony as in the wild type (compare Figure 8C and 8D). These results indicate that Rim101p, like alkaline pH, regulates the expansion of the interior region of sporulation within colonies.

DISCUSSION

The key results reported in this study are as follows: (1) Spore formation occurs in a sharply defined layered pattern in colonies, as does IME1 and IME2 expression, (2) IME2 expression and spore formation within colonies are regulated by cell-to-cell alkali signals, and (3) the Rim101/PacC pathway responds to alkaline pH to regulate both the efficiency and the pattern of sporulation.

Our results suggest a model in which sporulating cells in colonies secrete alkali and this alkali in turn stimulates sporulation in neighboring cells. This model is consistent with an earlier finding that cells in sporulation cultures secrete bicarbonate (an alkali), and this bicarbonate stimulates sporulation in these cultures (Ohkuni et al. 1998). Bicarbonate is produced during sporulation as a result of respiratory metabolism of nonfermentable carbon sources, and it is likely that secretion of alkali is just one of several ways that respiration and nonfermentable carbon sources stimulate sporulation (Treinin and Simchen 1993; Jambhekar and Amon 2008). Our model is strongly supported by the finding that mutants (ime1Δ, ime2Δ, hop2Δ, and ndt80Δ) producing more alkali than the wild type stimulated neighbor cell sporulation more than the wild type, whereas a mutant (cit1Δ) producing less alkali than the wild type stimulated neighbor cell sporulation less than the wild type.

Since IME1 and/or IME2 are required for induction of most or all sporulation genes, it is worth considering why ime1Δ and ime2Δ mutants ultimately produce more alkali than the wild type. Many metabolic genes, including genes required for respiration, are induced under sporulation conditions, but most of these genes are induced under these conditions even in MAT homozygous strains, which cannot initiate sporulation (Primig et al. 2000). Certain respiratory genes are induced to higher levels in sporulation-competent strains than in sporulation-defective strains (Primig et al. 2000), and this higher induction likely explains why at early stages of growth on plates, the wild type produces more alkali than the mutant. In contrast, once cells complete sporulation, metabolism ceases until spores encounter an environment that promotes their germination (Joseph-Strauss et al. 2007); hence, alkali production also would be expected to cease once cells complete sporulation. In summary, the higher production of alkali in meiosis-arrest mutants is very likely because these mutants produce alkali for a longer period than the wild type.

Alkali signaling between cells likely accounts for the upward expansion of the region of sporulation in colonies from a narrow initial band. This conclusion is based on the observations that addition of alkali to the medium accelerates the expansion of this band, whereas the rim101Δ mutant prevents this expansion. The Rim101 pathway is required for yeast and other fungi to respond to moderately alkaline pH environments (7.0–8.0); for example, this pathway allows pathogenic fungi to survive alkaline host environments (Davis 2009). Prior to this study, the Rim101 pathway had not been implicated in cell-to-cell signaling. Our results raise the possibility that pH signals are a general form of communication between cells. For example, pH signals may regulate the organization of extended colony-like structures termed “mats,” since a gradient of acidic pH (4.7–5.8) contributes to variation in cell adhesion through different regions of the mat (Reynolds et al. 2008). Furthermore, alkalinization is also a by-product of the periodic production of ammonia in colonies that triggers repeated cycles of growth and stasis in haploid colonies (Palkova and Vachova 2003).

The bottom layer of cells in a colony inhabits a unique nutrient environment close to the agar surface, which may explain the cells' high sporulation rate relative to more apical cells. In contrast, initiation of sporulation within a narrow interior band of cells cannot be explained by a unidirectional diffusion of nutrients through the colony (Turing 1952). Possibly, this region represents the intersection of two opposing gradients; for example, a gradient of acetate may diffuse upward from the bottom of the colony while a gradient of oxygen diffuses downward from the top. Consistent with this view, IME1 and IME2, which are subject to different nutritional controls (see Introduction), are initially transcribed in different regions: IME1 at the top of the colony and IME2 in the central part of the colony. Because both IME1 and IME2 are required for sporulation, the initial pattern of sporulation observed in the central region of the colony implies that this region may be apical enough to express IME1 and basal enough to also express IME2.

Cell-to-cell signals may be necessary for efficient sporulation within the suboptimal nutrient environment present in developing colonies. Indeed, by limiting meiosis and sporulation to a subset of cells in the colony, colony patterning may maximize the overall survival rate of the colony's population. In the wild, yeast strains outcross with genetically diverse strains, and even though these outcrosses are relatively infrequent, they result in an increase in the genetic heterogeneity of the population (Johnson et al. 2004; Ruderfer et al. 2006; Diezmann and Dietrich 2009). Since communities of yeast in the wild could often contain genetically diverse strains, we speculate that clustering asci of different strains together within these communities would promote outcrossing.

The foundation of pattern formation in metazoans is the combination of long-range and short-range cell signals (Irvine and Rauskolb 2001; Kerszberg and Wolpert 2007); thus, it is interesting that colony sporulation patterns likely involve both long-range gradients of nutrients and short-range cell-to-cell signals. Differences in nutrient microenvironments across the colony could cause sporulation to initiate in specific regions, and pH signals between cells would reinforce these differences to sharpen the sporulation pattern. Nevertheless, pH signals are probably not sufficient to explain the remarkably sharp boundaries between sporulated and unsporulated regions in colonies. By analogy to pattern formation in metazoans, precise boundaries in developing colonies may require multiple signals, including both diffusible and cell-surface ligands. In this respect, yeast colonies may preserve some of the simplest, yet most ancient and most fundamental, mechanisms of cell patterning.

Acknowledgments

We thank Misa Gray [University of Missouri–Kansas City (UMKC)] for strain construction, Jessica Kueker (UMKC) and Jennifer Baumler (UMKC) for help in developing the sectioning protocols, Jeffrey Price (UMKC) for use of equipment, Gerald Wyckoff (UMKC) for suggestions related to image analysis, Justin Fay (Washington University) for helpful discussions, and Daniel Gottschling (Frederick Hutchinson Cancer Center) for advice on colony cryosections. This work was supported by grants from the National Institutes of Health (R15GM80710 and R15GM80710-S1) to S.M.H.

Supporting information is available online at http://www.genetics.org/cgi/content/full/genetics.109.113480/DC1.

References

- Baillie, G. S., and L. J. Douglas, 1999. Role of dimorphism in the development of Candida albicans biofilms. J. Med. Microbiol. 48 671–679. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Colomina, N., E. Gari, C. Gallego, E. Herrero and M. Aldea, 1999. G1 cyclins block the Ime1 pathway to make mitosis and meiosis incompatible in budding yeast. EMBO J. 18 320–329. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davis, D. A., 2009. How human pathogenic fungi sense and adapt to pH: the link to virulence. Curr. Opin. Microbiol. 12 365–370. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Diezmann, S., and F. S. Dietrich, 2009. Saccharomyces cerevisiae: population divergence and resistance to oxidative stress in clinical, domesticated and wild isolates. PLoS One 4 e5317. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guttmann-Raviv, N., S. Martin and Y. Kassir, 2002. Ime2, a meiosis-specific kinase in yeast, is required for destabilization of its transcriptional activator, Ime1. Mol. Cell. Biol. 22 2047–2056. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Honigberg, S. M., and K. Purnapatre, 2003. Signal pathway integration in the switch from the mitotic cell cycle to meiosis in yeast. J. Cell Sci. 116 2137–2147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Irvine, K. D., and C. Rauskolb, 2001. Boundaries in development: formation and function. Annu. Rev. Cell. Dev. Biol. 17 189–214. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jambhekar, A., and A. Amon, 2008. Control of meiosis by respiration. Curr. Biol. 18 969–975. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson, L. J., V. Koufopanou, M. R. Goddard, R. Hetherington, S. M. Schafer et al., 2004. Population genetics of the wild yeast Saccharomyces paradoxus. Genetics 166 43–52. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Joseph-Strauss, D., D. Zenvirth, G. Simchen and N. Barkai, 2007. Spore germination in Saccharomyces cerevisiae: global gene expression patterns and cell cycle landmarks. Genome Biol. 8 R241. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaiser, C., S. Michaelis and A. Mitchell, 1994. Methods in Yeast Genetics: A Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Course Manual. Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press, Cold Spring Harbor, NY.

- Kassir, Y., N. Adir, E. Boger-Nadjar, N. G. Raviv, I. Rubin-Bejerano et al., 2003. Transcriptional regulation of meiosis in budding yeast. Int. Rev. Cytol. 224 111–171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kerszberg, M., and L. Wolpert, 2007. Specifying positional information in the embryo: looking beyond morphogens. Cell 130 205–209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim, K. S., M. S. Rosenkrantz and L. Guarente, 1986. Saccharomyces cerevisiae contains two functional citrate synthase genes. Mol. Cell. Biol. 6 1936–1942. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kimmel, A. R., and R. A. Firtel, 2004. Breaking symmetries: regulation of Dictyostelium development through chemoattractant and morphogen signal-response. Curr. Opin. Genet. Dev. 14 540–549. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lamb, T. M., and A. P. Mitchell, 2003. The transcription factor Rim101p governs ion tolerance and cell differentiation by direct repression of the regulatory genes NRG1 and SMP1 in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Mol. Cell. Biol. 23 677–686. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee, R. H., and S. M. Honigberg, 1996. Nutritional regulation of late meiotic events in Saccharomyces cerevisiae through a pathway distinct from initiation. Mol. Cell. Biol. 16 3222–3232. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leu, J. Y., P. R. Chua and G. S. Roeder, 1998. The meiosis-specific Hop2 protein of S. cerevisiae ensures synapsis between homologous chromosomes. Cell 94 375–386. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li, W., and A. P. Mitchell, 1997. Proteolytic activation of Rim1p, a positive regulator of yeast sporulation and invasive growth. Genetics 145 63–73. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mitchell, A. P., S. E. Driscoll and H. E. Smith, 1990. Positive control of sporulation-specific genes by the IME1 and IME2 products in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Mol. Cell. Biol. 10 2104–2110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ohkuni, K., M. Hayashi and I. Yamashita, 1998. Bicarbonate-mediated social communication stimulates meiosis and sporulation of Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Yeast 14 623–631. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Palkova, Z., and L. Vachova, 2003. Ammonia signaling in yeast colony formation. Int. Rev. Cytol. 225 229–272. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Palkova, Z., and L. Vachova, 2006. Life within a community: benefit to yeast long-term survival. FEMS Microbiol. Rev. 30 806–824. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Penalva, M. A., and H. N. Arst, Jr., 2004. Recent advances in the characterization of ambient pH regulation of gene expression in filamentous fungi and yeasts. Annu. Rev. Microbiol. 58 425–451. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Primig, M., R. M. Williams, E. A. Winzeler, G. G. Tevzadze, A. R. Conway et al., 2000. The core meiotic transcriptome in budding yeasts. Nat. Genet. 26 415–423. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Purnapatre, K., and S. M. Honigberg, 2002. Meiotic differentiation during colony maturation in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Curr. Genet. 42 1–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Purnapatre, K., S. Piccirillo, B. L. Schneider and S. M. Honigberg, 2002. The CLN3/SWI6/CLN2 pathway and SNF1 act sequentially to regulate meiotic initiation in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Genes Cells 7 675–691. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reynolds, T. B., and G. R. Fink, 2001. Bakers' yeast, a model for fungal biofilm formation. Science 291 878–881. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reynolds, T. B., A. Jansen, X. Peng and G. R. Fink, 2008. Mat formation in Saccharomyces cerevisiae requires nutrient and pH gradients. Eukaryot. Cell 7 122–130. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rose, M. D., F. Winston and P. Hieter, 1990. Methods in Yeast Genetics: A Laboratory Course Manual. Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press, Cold Spring Harbor, NY.

- Rothfels, K., J. C. Tanny, E. Molnar, H. Friesen, C. Commisso et al., 2005. Components of the ESCRT pathway, DFG16, and YGR122w are required for Rim101 to act as a corepressor with Nrg1 at the negative regulatory element of the DIT1 gene of Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Mol. Cell. Biol. 25 6772–6788. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ruderfer, D. M., S. C. Pratt, H. S. Seidel and L. Kruglyak, 2006. Population genomic analysis of outcrossing and recombination in yeast. Nat. Genet. 38 1077–1081. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scherz, R., V. Shinder and D. Engelberg, 2001. Anatomical analysis of Saccharomyces cerevisiae stalk-like structures reveals spatial organization and cell specialization. J. Bacteriol. 183 5402–5413. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Serebriiskii, I. G., G. G. Toby and E. A. Golemis, 2000. Streamlined yeast colorimetric reporter activity assays using scanners and plate readers. Biotechniques 29 278–279, 282–284, 286–288. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Strmecki, L., D. M. Greene and C. J. Pears, 2005. Developmental decisions in Dictyostelium discoideum. Dev. Biol. 284 25–36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Treinin, M., and G. Simchen, 1993. Mitochondrial activity is required for the expression of IME1, a regulator of meiosis in yeast. Curr. Genet. 23 223–227. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Turing, A., 1952. The chemical basis of morphogenesis. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. B 237 37–72. [Google Scholar]

- Vachova, L., and Z. Palkova, 2005. Physiological regulation of yeast cell death in multicellular colonies is triggered by ammonia. J. Cell Biol. 169 711–717. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vachova, L., O. Chernyavskiy, D. Strachotova, P. Bianchini, Z. Burdikova et al., 2009. Architecture of developing multicellular yeast colony: spatio-temporal expression of Ato1p ammonium exporter. Environ. Microbiol. 11 1866–1877. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu, L., M. Ajimura, R. Padmore, C. Klein and N. Kleckner, 1995. NDT80, a meiosis-specific gene required for exit from pachytene in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Mol. Cell. Biol. 15 6572–6581. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]