Abstract

The Drosophila Hox gene Ultrabithorax (Ubx) produces a family of protein isoforms through alternative splicing. Isoforms differ from one another by the presence of optional segments—encoded by individual exons—that modify the distance between the homeodomain and a cofactor-interaction module termed the “YPWM” motif. To investigate the functional implications of Ubx alternative splicing, here we analyze the in vivo effects of the individual Ubx isoforms on the activation of a natural Ubx molecular target, the decapentaplegic (dpp) gene, within the embryonic mesoderm. These experiments show that the Ubx isoforms differ in their abilities to activate dpp in mesodermal tissues during embryogenesis. Furthermore, using a Ubx mutant that reduces the full Ubx protein repertoire to just one single isoform, we obtain specific anomalies affecting the patterning of anterior abdominal muscles, demonstrating that Ubx isoforms are not functionally interchangeable during embryonic mesoderm development. Finally, a series of experiments in vitro reveals that Ubx isoforms also vary in their capacity to bind DNA in presence of the cofactor Extradenticle (Exd). Altogether, our results indicate that the structural changes produced by alternative splicing have functional implications for Ubx protein function in vivo and in vitro. Since other Hox genes also produce splicing isoforms affecting similar protein domains, we suggest that alternative splicing may represent an underestimated regulatory system modulating Hox gene specificity during fly development.

HOX genes are key genetic elements for the development of most animals. They encode a family of transcriptional regulators that trigger different developmental programs at specific coordinates along the antero-posterior body axis of animals (McGinnis and Krumlauf 1992; Alonso 2002; Pearson et al. 2005). In addition to their crucial developmental roles, the biological relevance of Hox genes is further emphasized by the fact that changes in the expression and function of Hox genes are associated with the emergence of new structures during animal evolution, suggesting that genetic variation affecting Hox gene activity may have been causal to the generation of morphological diversity (Lewis 1978; Holland and Garcia-Fernandez 1996; Carroll et al. 2001; Galant and Carroll 2002; Hughes and Kaufman 2002; Ronshaugen et al. 2002; Pearson et al. 2005).

In spite of their generality and importance for animal development and evolution, many aspects of Hox gene function remain unclear. One of them concerns the mechanisms underlying their specificity of action within developmental units, such as the individual segments in the insects. The problem could be stated as follows: given that from very early in development all cells within each segment are allocated a unique Hox “code” (Lewis 1978), all the morphogenetic complexity internal to the segment must be derived from a relatively simple Hox input, leading to the question of how Hox activities could be subspecified at the cellular level during the progressive development of segments. Combinatorial control by different Hox genes acting on overlapping target tissues may be one of the mechanisms used to increase regulatory complexity (Struhl 1982); however, in many cases Hox gene products were shown to compete with each other to take control of a developing segment (Gonzalez-Reyes and Morata 1990; Gonzalez-Reyes et al. 1990; Lamka et al. 1992; Akam 1998), arguing for the existence of other mechanisms for Hox specificity. Cell-specific “cofactors” able to modulate Hox transcriptional functions in individual cells could also provide an important contribution to the specificity of Hox genes (Mann 1995; Mann and Chan 1996). Nonetheless, to date, only a very limited number of Hox cofactors have been identified, making it difficult to explain how complex morphogenetic pathways, which rely on the orchestrated behavior of thousands of cells, could be obtained from such a simple Hox/cofactor molecular code. Also, the intricate cis-regulatory regions controlling Hox gene transcriptional patterns as well as the existence of microRNA-dependent regulatory mechanisms could also contribute to Hox gene specificity during development. Alternative splicing, a mechanism able to generate different mRNAs from a single gene (Smith and Valcarcel 2000; Matlin et al. 2005; Wang and Burge 2008), may also play an important role, and here we use the Drosophila Hox gene Ultrabithorax (Ubx) to study to what extent alternative splicing contributes to the diversification of Ubx function during Drosophila development.

Proteins encoded by all Hox genes share a common DNA-binding unit, the homeodomain (McGinnis et al. 1984a,b; Scott and Weiner 1984), comprising three α-helices, with helices 2 and 3 forming a helix-turn-helix motif (Chan and Mann 1993; Branden and Tooze 1999). Interestingly, outside this conserved domain, Hox proteins of different classes show little obvious similarity, other than a few conserved modules. One of these modules is a cofactor-interaction motif termed the “YPWM” or “hexapeptide” motif (Chang et al. 1995; Johnson et al. 1995). Although during development Hox proteins are likely to function in concert with suites of auxiliary factors (see Gebelein et al. 2004), so far the Hox cofactors studied most extensively are the Pbc family of transcription factors. This family includes the Drosophila protein Extradenticle (Exd) and its vertebrate (i.e., Pbx) and nematode (i.e., Ceh-20) relatives (Flegel et al. 1993; Rauskolb et al. 1993; Chang et al. 1995; Popperl et al. 1995; Liu and Fire 2000). These are members of the three-amino-acid loop extension (TALE) class of homeodomain proteins. Crystallographic and NMR studies demonstrate that Exd/Pbx proteins offer a hydrophobic pocket where the Hox hexapeptide is inserted, providing a fine example of “lock and key” binding (Passner et al. 1999; Sprules et al. 2003). The affinity of Hox proteins for certain DNA targets is modulated through cooperative interactions with Pbc proteins (Chan et al. 1994; van Dijk and Murre 1994). Many examples indicate that cofactor interactions increase the specificity of function of Hox proteins (Mann and Chan 1996; Graba et al. 1997; Mann and Affolter 1998). The subcellular location of Exd—whether nuclear or cytoplasmic—is controlled by specific interactions with another protein, Homothorax (Hth) (Aspland and White 1997; Rieckhof et al. 1997; Pai et al. 1998; Abu-Shaar et al. 1999), which also has vertebrate counterparts (the Meis or Prep proteins) (Mercader et al. 1999). Hth has been shown to bind DNA in a complex with Exd and Hox partners and is believed to be another factor refining Hox specificity toward particular targets (Mann and Affolter 1998; Ryoo and Mann 1999; Ryoo et al. 1999; Van Auken et al. 2002).

In Drosophila melanogaster, alternative splicing controls the expression of several Hox genes generating protein products with variation in the architecture of the linker region, the protein segment that separates the homeodomain from the hexapeptide motif. Nonetheless, the functional effects that splicing may have on the modulation of Hox gene function have only been partly explored (Alonso and Wilkins 2005). Ubx is expressed in a specific region along the antero-posterior axis of the Drosophila body: the posterior thorax and anterior abdomen (principally parasegments 5 and 6), where it determines segment-specific characteristics of many different cell lineages, including epidermis, central and peripheral nervous system, and mesodermal tissues (Morata and Kerridge 1981; Struhl 1984; Akam and Martinez-Arias 1985; Akam et al. 1985; Beachy et al. 1985; White and Wilcox 1985). Ubx splicing isoforms differ from one another by the presence or absence of three short optional peptides (9–17 residues) encoded by small exons (termed b, M1, and M2 modules) that separate the Ubx 5′ exon (encoding the hexapeptide) from the 3′ exon, which encodes the homeodomain (Figure 1) (O'Connor et al. 1988; Kornfeld et al. 1989). Ubx isoforms are generated by a mechanism of resplicing (Hatton et al. 1998) that is affected by the rate at which Ubx transcripts are elongated by RNA pol II (de la Mata et al. 2003); the factors involved in Ubx splicing include the products of the Drosophila genes virilizer, fl(2)d, and crooked neck (Burnette et al. 1999). Immunohistochemical staining demonstrates that each isoform has a specific spatiotemporal pattern of expression (Lopez and Hogness 1991). There is also some indication that the phosphorylation pattern of the isoforms may be distinct and developmentally regulated (Lopez and Hogness 1991).

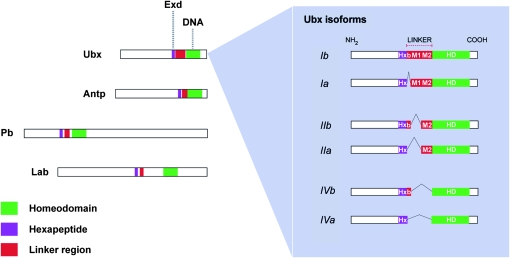

Figure 1.—

Alternative spliced modules in Drosophila Hox proteins. For the four proteins Ultrabithorax (Ubx), Antennapedia (Antp), Proboscipedia (Pb), and Labial (Lab), differential splicing modifies the structure of the linker region (red) that separates the DNA-binding module (green) from the hexapeptide, an Exd interaction motif (purple). The inset details the protein isoforms generated from the Ubx gene through the inclusion/exclusion of alternative exons, i.e., the “b” element (b) and microexons 1 (M1) and 2 (M2) that separate the hexapeptide (Hx) from the homeodomain (HD). Each isoform has a specific pattern of expression that is conserved across evolutionarily distant Drosophila species (Bomze and Lopez 1994). The diagram is approximately to scale, but in the inset, the size of the microexons is exaggerated.

To what extent the different isoforms have different biological functions remains unclear. One study, which focuses on a Ubx mutation (UbxMXI7) that blocks formation of several isoforms, concluded that the different isoforms are of little biological significance (Busturia et al. 1990). However, further investigation of the UbxMXI7 phenotype combined with studies using heat-shock ectopic expression have reported that isoforms have unique functions in defining tissue differentiation and therefore are not interchangeable (Mann and Hogness 1990; Subramaniam et al. 1994). A comparative study provides further evidence suggesting that the isoforms are functionally distinct: Bomze and Lopez (1994) showed that the pattern of optional exon use and the differential expression of the isoforms in different tissues are similar in Drosophila species that diverged at least 60 million years ago. In spite of this, and perhaps due to the contradictions between these latter studies and the earlier work, most recent studies have assumed that alternative splicing is not significant to Ubx function: when testing the participation of Ubx in a given developmental process, the current standard practice is to ignore the effects of alternative splicing altogether and test only one of the Ubx alternative splicing isoforms.

Here we reexamine the problem of the functional specificity of Ubx proteins. First, by using the UAS/Gal-4 mediated induction technique (Brand and Perrimon 1993), we look at the ability of the isoforms to activate a natural Ubx molecular target, the decapentaplegic gene (dpp) (Capovilla et al. 1994), in a specific tissue: the embryonic mesoderm. Second, using the UbxMXI7 mutant, in which the full spectrum of splicing isoforms is reduced to one single Ubx protein (produced within the normal developmental expression domain of Ubx and at endogenous levels), we observe anomalies in the patterning of anterior abdominal muscles. Third, we test the performance of Ubx proteins in in vitro DNA-binding experiments using a Ubx–Exd composite DNA target element. Our results show that alternative splicing modulates Ubx specificity and function in vivo and alters basic Ubx biochemical properties in vitro. On the basis of these findings we discuss the role of alternative splicing as a post-transcriptional regulatory process affecting Hox gene function during fly development.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Genetic engineering and fly lines:

Site-directed mutagenesis was carried out by splicing by overlap extension (SOE) as previously described (Higuchi et al. 1988). Starting DNA materials were kindly provided by S. Greig (pKSUbxIb) and R. Weinzierl (PMR100 versions of Ubx isoforms Ia, IIa, IIb, IVa, and IVb). Final PCR products were gel purified, cloned into the pGEM-T easy cloning vector (Promega, Madison, WI), and subcloned into the pUAST vector (Brand and Perrimon 1993). UAS-Ubx constructs were transformed into Drosophila embryos using standard P-element-mediated germline transformation techniques (Rubin and Spradling 1982; Spradling and Rubin 1982). Other fly stocks employed in this study have been described previously: 24B-Gal4 (Brand and Perrimon 1993), twist-Gal4 (Greig and Akam 1993) [twi Gal4 drives expression in all mesodermal cells from stage 9 to 12, and 24B-Gal4 initiates expression in cardiac and somatic mesoderm at stage 10/11 and continues from that point onward throughout development (Liu et al. 2008a)], dpp674LacZ (Capovilla et al. 1994), and UbxMX17/TM6 (Busturia et al. 1990), which was a kind gift from Gines Morata.

Manipulation of fly embryos, RNA in situ hybridizations, and immunostainings:

All fly stocks were cultured at 25°. Embryo collections were carried out on apple juice plates supplemented with fresh live yeast. For immunodetection, embryos were fixed/devitellinized in a heptane/formaldehyde mix following standard protocols. Ubx protein was detected using the FP3.38, anti-Ubx antibody. Expression of lacZ reporter constructs was detected by commercial anti-β galactosidase antibody (Molecular Probes, Eugene, OR). Enzymatic activity from secondary antibodies was visualized using a Vectastain Elite ABC Kit following manufacturer's instructions (Vector Laboratories, Burlingame, CA). Connectin immunolabeling was performed as in Meadows et al. (1994). In situ hybridization for dpp was perfomed following the protocol of Tautz and Pfeifle (1989), using pNB-40.decapentaplegic as template (a gift from Robert Ray, originally subcloned by Nick Brown), which includes a 3.5-kb dpp fragment; in situs for slouch were performed as in Gould and White (1992), using S59 cDNA as template [kindly provided by Manfred Frasch (Dohrmann et al. 1990)].

Protein expression and quantification:

Ubx cDNAs were modified to encode wild-type and mutagenized full-length Ubx isoforms Ia and IVa and subcloned in pGEM-T Easy. A pRSET plasmid (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) carrying an Exd full-length wild-type cDNA was obtained from Simon Aspland. Ubx and Exd proteins were prepared from T7 or SP6 promoters, using the TnT coupled in vitro transcription and translation system (Promega) in the presence of small amounts of [35S]methionine (Amersham, Piscataway, NJ). This weak labeling approach provided a convenient and reliable strategy for the quantification of each protein batch (see below). For each isoform, 12% PAGE electrophoresis of labeled proteins demonstrated the synthesis of a product of appropriate size (supporting information, Figure S4 A). Quantification of the 35S-labeled proteins was carried out in a PhosphorImager Scanner Unit (BAS-2500), using Image Reader Software (Fujifilm). Signal values corresponding to each protein band were determined by profile scanning using Mac BAS image analysis software (Fujifilm). These values were transformed to comparable protein units by normalization for the number of methionine residues present in each isoform. All protein samples were aliquoted and kept at −80° until use.

Electrophoretic mobility shift assays:

Single-strand oligonucleotides for a Hox-Exd composite element were commercially synthesized (Sigma Genosys). Sequences for each strand were Hox-Exd/A 5′ TTAGCGATGATTTATTGCCTCCTT 3′ and Hox-Exd/B 5′ TTAAGGAGGCAATAAATCATCGCT 3′. Oligonucleotides were resuspended in distilled water, annealed, and labeled with the Klenow fragment of DNA pol I (New England Biolabs, Beverly, MA) and [α-32P]dATP (6000 Ci/mmol) (from Amersham). Labeled oligos were purified from unincorporated nucleotides using molecular filtration columns (Microspin G-25 columns; Pharmacia, Piscataway, NJ). Proteins used in binding experiments were labeled at very low specific activity, quantified as explained above, and used in DNA-binding experiments. Control experiments with unlabeled DNA probes demonstrated that the weak signals from 35S-labeled proteins were beyond the detection limit in our binding experiments, producing results indistinguishable from those obtained with unlabeled “cold” proteins. Therefore, in these conditions, we had absolute certainty on the protein units present in each binding reaction, without affecting the readout of our DNA-binding experiments. Apart from this important difference, conditions for the DNA-binding assay were similar to those previously described (Galant and Carroll 2002). In brief, 5 μl of reticulocyte lysate reaction mixture (containing Exd and/or Ubx in different amounts) was incubated on ice, with nonspecific competitor p[dIdC] (1 μg per reaction) in 1× gel shift buffer [10 mm Tris-Cl (pH 7.5), 75 mm NaCl, 1 mm EDTA, 6% glycerol, 3 mm spermidine, 1 mm DTT] for 15 min. Independently of the protein combination analyzed, the total volume of lysate was kept constant in all reactions. The double-stranded, end-labeled DNA probe (10,000–15,000 cpm) was incubated with each protein mixture for 15 min on ice. For competition experiments, unlabeled oligonucleotides at different molarities were added prior to the addition of the probe. The total reaction volume was 20 μl. Reactions were analyzed in 6% polyacrylamide gels to resolve protein–DNA complexes through retardation of 32P-labeled DNA. Gels were dried and exposed to PhosphorImager plates (MS2040 Fujifilm) and quantified as indicated above (see protein expression). Signal values corresponding to each protein–DNA complex were determined by profile scanning using Mac BAS image analysis software (Fujifilm). Background levels were substracted and signal values for the different complexes were imported into Excel:Mac (Microsoft Excel). In Figure 6A values were used to generate a simple column chart. The maximum binding activity detected in the experiment (i.e., UbxIVa WT, 1.5 protein units) was considered as 100%, and all other values were expressed as a percentage of this maximum value (% of Max). In Figure 6, B–D, signal values for ternary complexes were also expressed as % of Max and were subsequently used to generate scatter plots. A linear regression was calculated for each family of values corresponding to different amounts of each Ubx isoform. Linear equations for these trendlines are displayed at the bottom of each panel. Slope values in these equations are treated in the text as approximations for the affinity constants of the different [isoforms] (as one component) for [Exd/DNA] (as the second component). To facilitate the comparison across charts, we pooled together the values for UbxIVa WT from the experiments in Figure 6, B and C, plotted the average values for each protein concentration, and obtained a trendline. We did the same with the binding values for UbxIa WT in experiments in Figure 6, B and D. We defined 100% binding as the values of the UbxIVa WT trendline at 1.5 protein units (i.e., the highest protein concentration point of UbxIVa WT in our experimental interval). All other values in Figure 6, B–D, were normalized to this calibration.

Figure 6.—

Ubx in vitro interaction with Exd is isoform specific. (A) Equal amounts of different Ubx proteins were incubated in the absence (lanes 1–4) or presence of Exd (lanes 5–8). Ubx proteins alone displayed very low binding activity for the element analyzed (lanes 1–4). Exd was able to interact with all Ubx protein forms although the degree of these interactions was notably different (see below). Doubling the amount of Ubx protein in the reaction (lanes 9–12) proportionally increased the signal detected in ternary complexes, indicating that the differential interaction observed among Ubx proteins represents intrinsic properties of the proteins rather that some other experimental limiting factor. Exd alone is not able to bind to this element in a stable manner (lane 13). The quantification of the experiment is shown to the right. (B) Wild-type UbxIVa/Exd bind the DNA probe more strongly than UbxIa/Exd. Similar amounts of UbxIa and UbxIVa were incubated in the presence of Exd and the relative amount of protein–DNA complexes was quantified (see chart). (C) Ubx “hexapeptide-independent” interaction with Exd on DNA is isoform specific. A similar experiment to that in B shows that for isoform UbxIVa, the elimination of the hexapeptide decreases the interaction with Exd. (D) UbxIa lacking the hexapeptide is able to interact with Exd in the presence of a DNA target. Similar amounts of UbxIa wild type (lanes 1–6) and UbxIa Ala (lanes 7–12) display a similar Exd interaction profile in the presence of a Hox-Exd element, suggesting that UbxIa possesses areas of interaction with Exd other than the hexapeptide. When compared to C, these results also indicate that the linker region is able to affect the strength of Ubx–Exd protein interactions on the DNA element under study. Note that the levels of relative binding in the plots shown in C and D have been normalized to the level of binding of wild-type proteins in experiment B (for further details please see materials and methods).

RESULTS

Function of Ubx proteins in vivo:

Reading Ubx outputs modulated by alternative splicing in ectopic expression experiments:

To test the function of Ubx proteins in vivo, we engineered P-element constructs with Ubx coding sequences placed under the control of the yeast UAS promoter. The resulting transgenes were therefore inducible by the yeast transcriptional activator Gal-4 (Brand and Perrimon 1993).

To corroborate that each line was able to produce Ubx protein and to test the extent to which each line was inducible by Gal-4, we performed a control experiment with the potent ectodermal Gal-4 driver 69B. UAS-Ubx transgenic lines were crossed to the 69B-Gal4 line and the resulting embryos were labeled with FP3.38 anti-Ubx antibody. Embryos from all of the UAS-Ubx lines expressed Ubx protein throughout the ectoderm. To confirm that all Ubx protein variants were functional, we compared cuticle preparations of these embryos (not shown) and looked at the development of the midgut structures after ectopic expression of all Ubx isoforms in the mesoderm (see below). All constructs transformed T3 denticle belts to an abdominal identity following misexpression in the ectoderm and blocked formation of the anterior midgut constriction following expression in the mesoderm (Figure 2).

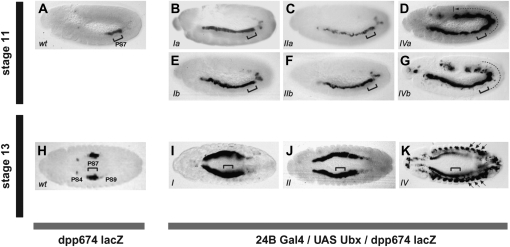

Figure 2.—

Function of ectopically expressed Ubx proteins in the mesoderm. Embryos were stained for β-gal produced from a dpp-lacZ construct, which by stage 15 outlines the forming gut tube. (A) Wild-type embryo displaying the three embryonic midgut constrictions (C1–C3, red arrowheads). (B) 24B-Gal4/UAS-UbxIa embryo. Note that the formation of the anterior midgut constriction is abnormal (asterisk, blue bracket) while the second and third constrictions are normal (C2 and C3). All Ubx protein isoforms from all our transgenic lines produced the same morphological distortion. (Embryos are shown in dorsal view, with anterior end to the left.)

In the embryonic mesoderm, Ubx is expressed from parasegment 6 to parasegment 12. Within this domain, Ubx functions in several mesodermally derived tissues, including the visceral mesoderm, the somatic musculature, the heart, and the fat body (Bienz and Tremml 1988; Michelson 1994; Ponzielli et al. 2002). In the visceral mesoderm, Ubx is expressed only in parasegment 7 (PS7), where it activates the expression of its direct target decapentaplegic (dpp) (Bienz and Tremml 1988; Capovilla et al. 1994; Manak et al. 1994; Sun et al. 1995). Expression of dpp is required for the correct formation of the second midgut constriction (Bienz and Tremml 1988). dpp is not expressed in the other mesodermal derivatives of PS7 (e.g., somatic mesoderm).

Systematic molecular dissection of the dpp genomic region has revealed that a 674-bp fragment of this region is sufficient to drive the expression of a β-galactosidase reporter construct in a pattern that resembles that of dpp in PS7 of the visceral mesoderm (Capovilla et al. 1994; Sun et al. 1995) (Figure 3). Since Ubx binds this sequence and the integrity of the Ubx sites is required for its in vivo expression (Capovilla et al. 1994), this fragment constitutes one of the best-characterized in vivo molecular targets of Ubx. Importantly, the activation of dpp is specific to Ubx. Abd-A, a Hox protein more posteriorly expressed, represses dpp in parasegments 8–12 of the visceral mesoderm (Immergluck et al. 1990; Hursh et al. 1993). dpp activation by Ubx is also specific to the visceral mesoderm. Ubx does not activate dpp in most other mesodermal derivatives where it is expressed (e.g., somatic muscle, fat body, etc.).

Figure 3.—

Isoform-specific functions of Ubx proteins during embryonic development. β-Gal immunostaining is shown of stage 11 (A–G) and stage 13 (H–K) fly embryos carrying a dpp-lacZ reporter construct. (A and H) Wild-type control embryos where dpp-lacZ is activated in a subregion of the midgut corresponding to parasegment 7 (PS7, bracket). In stage 13 embryos (H), signal can also be seen in the primordium of the gastric caeca (visceral mesoderm PS4, labeled PS4) and in the faint rings of PS9 (PS9). (B–G) Effects of Ubx protein expression driven by 24B-Gal4 on the activation of the dpp-lacZ reporter. Isoforms Ia (B), IIa (C), Ib (E), and IIb (F) display similar abilities to activate dpp throughout the midgut visceral mesoderm from parasegment 2 to 7 and in two rather weak rings located approximately on PS9. Notably, isoforms IVa (D) and less strongly, isoform IVb (G) are able to activate dpp-lacZ throughout the midgut visceral mesoderm in a region that extends from parasegment 2 posteriorly to at least parasegment 12 (see dotted lines). By stage 13, isoforms I and II continue to activate the dpp reporter in the midgut visceral mesoderm (I and J, respectively) while isoforms IV (K) are also able to activate the lacZ construct in the somatic musculature (arrows). The square bracket indicates the approximate region of reporter expression in control embryos. Labels at the bottom left corner of each panel indicate the Ubx isoform expressed in each case. I–K show the effects of isoforms “a” only. Variants “b” for each isoform yield comparable results to their “a” counterparts (not shown). [Embryos are shown in lateral view (A–G) or dorsal view (H–K) always with anterior end to the left.]

To test isoform functions in vivo, we examined the ability of various Ubx proteins to activate a dpp reporter element that contains the 674-bp dpp fragment, from here on referred to as dpp-lacZ.

All Ubx isoforms were expressed throughout the mesoderm, using the mesodermal driver line 24B-Gal4 (Brand and Perrimon 1993). All isoforms activated dpp-lacZ in the visceral mesoderm (Figure 3), indicating that every one of the isoforms is capable of direct transcriptional activation and able to recognize a mesoderm-specific target.

Ectopic dpp-lacZ expression is first seen at stage 11. No detectable ectopic Ubx is present prior to stage 11 when driven by 24B-Gal4, in agreement with the previously reported onset for 24B-Gal4 driver activity (Brand and Perrimon 1993). This is the stage when dpp-lacZ is first seen in PS7 in wild-type embryos (Figure 3).

With all of the isoforms, there is strong ectopic expression of dpp-lacZ anterior to PS7, extending to the anterior limit of the midgut visceral mesoderm. There is also ectopic activation posterior to PS7, but in this region the different Ubx isoforms differ noticeably in their effects. With Ubx I and II (in both variants “a” and “b”) dpp-lacZ expression posterior to PS7 is absent or weak, detected in scattered cells that occasionally form an expression ring, and delayed in its appearance (Figure 3). These isoforms never activate the reporter in the most posterior part of the midgut visceral mesoderm (Figure 3). In contrast, UbxIVa and to a lesser degree Ubx IVb activate dpp-lacZ strongly and throughout both anterior and posterior parts of the midgut visceral mesoderm (Figure 3).

Comparing the activation abilities of Ubx proteins at a slightly later stage in development reveals another isoform-specific effect. By stage 13, in wild-type embryos, dpp-lacZ is expressed in two distinct regions of the visceral mesoderm: (i) an anterior domain, where the gastric caeca will later form, and (ii) in a more posterior region where it is activated by the endogenous Ubx gene (Figure 3). Ectopic expression of Ubx isoforms I and II activates dpp-lacZ in only these two sets of cells, at ectopic positions along the anterior posterior axis (Figure 3). However, Ubx IV isoforms (both a and b) also activate dpp-lacZ in the somatic musculature, a tissue where neither dpp nor dpp-lacZ is normally expressed (Figure 3).

Several lines of evidence argue against the possibility that the activation of dpp-lacZ in posterior gut regions and the somatic mesoderm is due to higher induced protein levels in isoform IV lines. First, four independent transgenic lines for UbxIVa drive extensive expression of dpp-lacZ in the somatic mesoderm (including one that shows rather low levels of protein; see lane IVa2 in Figure S1), while none of eight independent UbxIa lines do so. Second, although Western blot experiments with Ubx antibodies show that the various UAS-Ubx lines achieve protein expression levels that differ appreciably, the in vivo abilities to activate the dpp-lacZ reporter do not correlate with these fluctuations in protein level (see Figure S1). Third, confocal microscopy analysis of 24B-driven UbxIa and UbxIVa lines (Figure S2) that displayed similar expression levels in Western blot experiments confirmed that these lines indeed achieve comparable levels of Ubx protein, although they display the isoform-specific patterns of dpp-lacZ discussed above. Fourth, overexpression of UbxIa using a combination of two effective mesodermal drivers (24B-Gal4 and twist-Gal4) does not lead to activation of dpp-lacZ outside the visceral mesoderm (see Figure S3). Altogether, these observations strongly support the conclusion that the differences in target gene activation represent real differences between the Ubx proteins assayed here and not just variations in the level of Ubx protein expression.

We then moved on to examine the ability of the Ubx proteins to regulate the expression of the endogenous dpp gene. Given that the dpp-lacZ experiments described above indicate that the greatest functional differences exist between isoforms I and IV, we decided to focus on the analysis of these two forms, expressing them in the embryonic mesoderm and looking at the resulting patterns of endogenous dpp transcription using RNA in situ hybridization. These experiments revealed that each Ubx isoform had specific abilities to control the expression of the endogenous dpp gene (Figure 4). In wild-type stage 13 embryos, dpp is expressed in the visceral mesoderm in a discrete domain corresponding to PS7 (Figure 4A); expression is also detectable in a smaller domain in the gastric caeca primordium (PS4). When UbxIa is ectopically expressed in the mesoderm, the expression domain of dpp extends anteriorly within the visceral mesoderm all the way to PS4 (Figure 4B). Notably, UbxIa is unable to activate endogenous dpp transcription in regions posterior to its normal expression domain in PS7, showing a sharp posterior boundary (Figure 4B). Generalized expression of UbxIVa in the mesoderm is—like that of UbxIa—able to extend the dpp expression domain to regions anterior to PS7 (Figure 4C); notably, this isoform is also able to activate dpp transcription posterior to PS7 (Figure 4C). In sum, we conclude that UbxIa and UbxIVa are able to regulate the transcription of the dpp gene in an isoform-specific fashion. This could partly be due to the differential abilities of the individual isoforms to compete efficiently with the products of the posterior Hox gene, Abdominal-A (Abd-A) on target regulation (see discussion below). Comparison of the activation profiles of the dpp-lacZ reporter and the endogenous dpp gene under ectopic expression of Ubx splicing isoforms reveals similarities but also some differences. For instance, we note that both target systems indicate that (i) UbxIa and UbxIVa are able to override normal dpp repression anterior to PS7 and (ii) there is an intrinsic ability of UbxIVa to activate dpp transcription in locations posterior to PS7. However, under UbxIVa regulation expression of the endogenous dpp endogenous gene is always confined to the correct tissue—the visceral mesoderm—in contrast to the ability of UbxIVa to activate the dpp-LacZ reporter in the somatic mesoderm. We also note a discrepancy in the timing of the regulatory effects specific to UbxIVa: activation of the dpp-LacZ construct in areas posterior to PS7 is detectable by stage 11 (Figure 3D); however, at this stage endogenous dpp expression seems normal and confined to visceral mesoderm PS7. The inability of UbxIVa to override normal tissue specificity on the dpp endogenous gene might be the consequence of cis-regulatory elements located outside the dpp674 fragment being able to maintain a repressed transcriptional state in spite of the ectopic Ubx regulatory input.

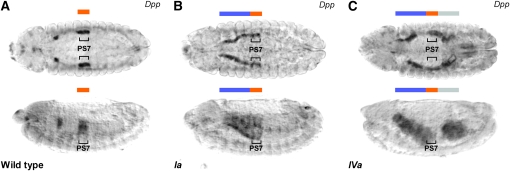

Figure 4.—

Regulation of the endogenous dpp gene by Ubx splicing isoforms in the visceral mesoderm. (A) Wild-type expression of dpp mRNA as judged by RNA in situ hybridization (stage 13 embryos). A discrete domain of dpp expression is detected in the visceral mesoderm PS7 (represented along the antero-posterior axis by an orange rectangle). (B) Regulation of dpp mRNA expression following generalized expression of UbxIa in the mesoderm as driven by twist-Gal4. Note (i) the existence of an anteriorly extended expression domain of dpp mRNA in this condition (blue rectangle) and (ii) the discrete posterior boundary of the UbxIa-induced dpp expression domain with no detectable dpp mRNA signal posterior to PS7. (C) dpp mRNA expression after UbxIVa expression in the mesoderm (driven by twist-Gal4). Note (i) the extended domain of dpp expression anterior to PS7 (blue rectangle) and (ii) a patchy but significant upregulation of dpp mRNA in the visceral mesoderm posterior to PS7 (gray rectangle). (All embryos are oriented with their anterior end to the left; embryos on the top are shown in dorsal view, and bottom embryos are in lateral view.)

Reading Ubx outputs modulated by alternative splicing during normal development:

Our experiments above clearly indicate that the different alternative splicing isoforms of Ubx are not equivalent in their abilities to regulate a natural downstream molecular target of Ubx, in vivo, during Drosophila embryogenesis. Nonetheless, on the basis of these experiments alone, it is difficult to assess the extent to which the different Ubx forms generated by alternative splicing perform isoform-specific functions during normal development.

Therefore, to further advance our functional models on the role played by alternative splicing on the specificity of Ubx function in a physiological context, we decided to analyze the developmental outputs obtained when only a limited spectrum of alternative splicing products is generated from the Ubx locus. For this we employed a Ubx mutant, termed UbxMX17 (Busturia et al. 1990), in which the full spectrum of Ubx splicing isoforms is reduced to one single functional form, UbxIVa (Subramaniam et al. 1994), due to an inversion of the M2 microexon. UbxMX17 mutant flies express UbxIVa within the normal Ubx expression domain at levels that match wild-type Ubx expression levels (see Figure S5); the flies are viable and fertile but adults show a partial transformation of halteres into wings, a characteristic indication of malfunction in Ubx, and embryos have defects in the peripheral nervous system (Subramaniam et al. 1994).

Here we extend the work of Subramaniam et al. (1994) by examining the phenotype of UbxMX17 mutants within a tissue directly related to our ectopic experiments (i.e., somatic mesoderm), focusing on a subset of internal structures, the larval muscles, which are formed during embryogenesis. The muscles are attached to the inner face of the epidermis and form a regular and highly stereotyped metamerically repeated array, with small but “scorable” differences between thoracic and abdominal segments (Figure 5, A and B). In full loss-of-function Ubx mutants, the muscles of the abdominal segments A1 and A2 are transformed toward a thoracic identity, seen as a loss of abdominal-specific muscles and a gain of thoracic-specific ones (Hooper 1986). This provided us with a clean testable hypothesis: if UbxIVa, the only Ubx isoform made in UbxMX17 mutants, was unable to compensate for the other isoforms in the somatic mesoderm of UbxMX17 embryos, then we expected a similar loss-of-function phenotype as described above.

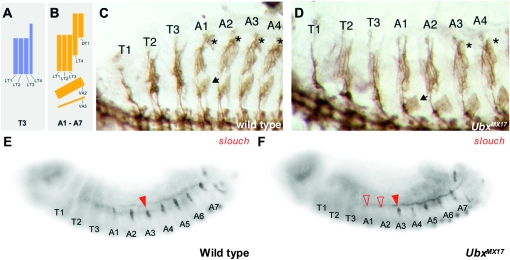

Figure 5.—

UbxMX17 phenotype in somatic mesoderm demonstrates specific in vivo functions of the Ubx isoforms. (A and B) Schematic of the pattern of relevant Connectin-expressing muscles in (A) wild-type third thoracic (T3) segment and in (B) the abdominal segments (A1–A7) (adapted from Nose et al. 1992 and Bate 1993). LT, lateral transverse; DT, dorsal transverse; VA, ventral acute. (C and D) Immunolabeling of Connectin in stage 16 embryo flatpreps. (C) Wild type. The abdominal-specific muscles are indicated; asterisks in A1–A7 indicate muscle DT1 and the arrowhead in A1 indicates VA2. (D) UbxMX17. A1 and A2 show transformation toward thoracic identity with loss of DT1 and thinner thoracic-like LT muscles; asterisks indicate DT1 muscles in A3 and A4. The transformation affects specific muscles as VA2 (arrowhead in A1) is still present in A1 and A2. (E and F) In situ hybridization for slouch mRNAs on stage 14 embryo whole mounts. (E) Wild type. Expression corresponding to the dorsal muscle DT1 is present from A1 to A7 (arrowhead in A3). (F) UbxMX17. A1 and A2 (open arrowheads) lack the DT1 slouch expression (arrowhead in A3). In this embryo, ventral cells expressing slouch are also in focus. (Embryos are shown in lateral view, anterior end to the left.)

To compare the phenotype of UbxMX17 with the wild type we used two molecular markers that show segment-specific expression in the larval muscles. Connectin is a cell surface molecule expressed in a subset of muscles including three abdominal-specific muscles, dorsal transverse 1 and ventral acute 2 and 3 (Figure 5C) (Nose et al. 1992). It is also expressed in the four lateral transverse muscles, which differ in morphology between thoracic and abdominal segments (Figure 5C). The second marker, slouch, encodes a transcription factor required for the specification of a subset of muscles including the abdominal-specific dorsal transverse 1 (Dohrmann et al. 1990). As shown in Figure 5, C–F, both markers show clear transformations in the muscle pattern in abdominal segments A1 and A2. Connectin labeling reveals a lack of the dorsal transverse 1 in segments A1 and A2 and the lateral transverse muscles have a thinner thoracic-like morphology in the UbxMX17 embryos (Figure 5, C and D). RNA in situ hybridization for slouch mRNAs supports the lack of the abdominal-specific dorsal transverse 1 in the A1 and A2 segments (Figure 5, E and F). Although the above features show a transformation of A1 and A2 toward a thoracic identity, this transformation appears only to affect a subset of muscles, as the abdominal-specific ventral acute 2 is still present in the A1 and A2 segments in UbxMX17 embryos (Figure 5, C and D). Overall the UbxMX17 muscle phenotype demonstrates a failure to specify Ubx-dependent abdominal features in A1 and A2, indicating the inability of the UbxIVa isoform to execute some specific functions that are normally performed by other Ubx isoforms.

Function of Ubx proteins in vitro:

The experiments above indicate that the different Ubx isoforms have isoform-specific abilities to regulate a natural molecular target in vivo. In molecular terms, such distinct target regulatory potentials could be dictated by differential binding profiles to DNA target sites, or by isoform-specific regulatory interactions between the individual Ubx proteins and the basal transcriptional apparatus, or by a combination of both mechanisms. To advance our understanding of the mechanistic basis underlying Ubx protein specificity we decided to test whether the different Ubx isoforms were able to bind DNA target elements with specific affinity profiles.

The ectopic in vivo experiments described above indicate that the greatest functional differences exist between isoforms I and IV, proteins that include and exclude the two M microexons, respectively (see Figure 1). Therefore, we focused our attention on the molecular analysis of these two. We employed “a” variants of these two isoforms, because “b” forms are present only at low levels during normal development, whereas both isoforms Ia and IVa represent significant fractions of the normal Ubx expression profile, in ectoderm and central nervous system, respectively (O'Connor et al. 1988; Kornfeld et al. 1989).

Hox protein function depends, in part, on cooperative interactions with cofactors such as Exd, which increase the specificity of DNA binding. Therefore, our experimental approach involved quantification of Ubx binding activities in the presence of Exd. All Ubx and Exd proteins were produced by in vitro translation in a rabbit reticulocyte lysate system (see materials and methods). Protein qualities and amounts were determined by 35S labeling with methionine followed by PAGE analysis and quantification (Figure S4 A). Protein amounts were carefully normalized in all assays (see materials and methods).

To dissect the contribution of protein interaction modules (such as the hexapeptide) within the backbone of different isoforms, we engineered versions of UbxIa and UbxIVa, in which the hexapeptide was replaced by an alanine tract. Mutagenesis of the hexapeptide motif has been previously shown to affect interactions between Hox and Pbc proteins (Chang et al. 1995; Knoepfler and Kamps 1995). Alanine replacement constructs were termed Ubx “ALA” versions.

We tested the behavior of several DNA elements in our binding experiments. From these we selected a composite Hox-Exd element that includes adjacent head-to-tail core sites for Ubx and Exd (Figure S4 B). Ubx/Exd protein complexes bind with high specificity to the Hox-Exd composite element (Figure S4, C and D). This element has been extensively used and validated in a number of previous studies including the crystallographic work that determined the structure of the ternary complex Ubx-Exd-DNA, the testing of DNA binding abilities of Ubx proteins from different species, and the molecular analysis of Ubx functions during haltere development (Passner et al. 1999; Galant and Carroll 2002; Galant et al. 2002). In contrast, other DNA elements, including sequences derived from the dpp regulatory region, produced highly unstable binding patterns even when assayed in a wide range of experimental conditions (i.e., variation in temperature, pH, binding, and running buffer composition) and therefore were not suitable for reliable binding quantification.

When assayed in the absence of Exd, all Ubx isoforms display only weak DNA-binding activity (Figure 6A, lanes 1–4). This binding activity increases greatly in the presence of Exd (Figure 6A, lanes 5–8). Exd alone did not produce any protein–DNA complexes in our assay (Figure 6A, lane 13).

In the presence of Exd, Ubx isoforms Ia and IVa, and their two Ala substitution derivatives, each bind DNA at a characteristic level (Figure 6A, lanes 5–8). When Ubx protein concentrations in the assays are doubled, the binding signals of the different isoforms increase accordingly but maintain their relative affinities (lanes 9–12), showing that these assays are being carried out under conditions where Exd protein is present in excess, and Ubx protein levels are not saturating.

To analyze these differences more precisely, we measured the dependence of binding on Ubx protein concentration for the two Ubx isoforms Ia and IVa (Figure 6B) and for each wild-type isoform in comparison with the corresponding Ala substitution variant (Figure 6, C and D). Comparison of wild-type versions of UbxIa and UbxIVa reveals that, in the presence of Exd, UbxIVa binds DNA more strongly than UbxIa (Figure 6B). Using the slopes of the trendlines for each case as an approximation for the affinity constants of the different isoforms for the Exd/DNA component, we estimate that the binding differences between IVa and Ia wild type are in the range of four- to fivefold (see equations in Figure 6B). This observation indicates that in our experimental conditions, the linker region containing microexons M1 and M2 has a significant role in the interaction of Ubx–Exd protein complexes with DNA.

In the case of UbxIa, replacement of the YPWM motif with (Ala)4 does not appreciably affect the amount of Ubx–Exd–DNA ternary complex formed (Figure 6D), suggesting that, for this isoform, the hexapeptide is not essential for the interaction of Ubx with Exd on DNA targets. However, in the case of UbxIVa, formation of the complex is substantially reduced by 40% when the hexapeptide module is replaced (Figure 6C). These experiments suggest that the linker region plays a significant role in mediating hexapeptide-independent interactions between Ubx and Exd on DNA targets.

DISCUSSION

The experiments described above indicate that the generation of structural differences among Ubx proteins by alternative splicing is relevant for the functional specificity of Ubx in vivo. We also see that these structural features modulate essential biochemical properties of Ubx proteins such as their DNA-binding profiles in the presence of a cofactor.

In vivo differences between Ubx isoforms:

The differential effects of Ubx in vivo are apparent in the posterior visceral mesoderm, but not in the anterior. To understand this we must first note that the mechanism of dpp674 repression is different anterior and posterior to PS7. In the anterior visceral mesoderm, repression requires Exd, since in Exd null mutants, dpp674 is ectopically expressed anterior to PS7 (Rauskolb and Wieschaus 1994). But Hox genes appear to play no role in the normal repression of dpp in this region (Rauskolb and Wieschaus 1994). The same Exd-dependent mechanism may also be acting in the posterior, but it is not necessary, for no posterior ectopic expression is observed in Exd null mutants. The posterior repression depends instead on the Hox protein Abd-A (Capovilla et al. 1994), which is presumably able to repress dpp674 in the absence of Exd as a cofactor.

All Ubx protein isoforms are able to induce dpp ectopically in the anterior, suggesting that they can all override the normal repression mediated by Exd. However, they exert differential effects in the posterior, where Abd-A is the controlling repressor. Abd-A has a very similar DNA-binding specificity to that of Ubx (Capovilla and Botas 1998). It binds to multiple sites in the dpp674 enhancer, including those to which Ubx binds. Through some of these sites it serves as an activator, but through others it acts as a repressor. With Ubx form Ia, the repressing effect by Abd-A is dominant (Capovilla and Botas 1998). Our results suggest that Ubx form IVa is either able to compete more effectively as an activator with the repressing action of Abd-A bound at other sites or able to displace the binding of Abd-A at the sites where it mediates repression.

Ubx form IVa also overrides the normal specificity of the dpp-lacZ enhancer for the visceral mesoderm, activating it ectopically in the somatic mesoderm of most trunk segments. It is not known whether the activity of this enhancer is normally restricted to the visceral mesoderm by a required cofactor that is present only in the visceral mesoderm, by repressors present in other tissues, or by both mechanisms. However, UbxIVa at high levels seems able to override this normal tissue specificity. The more efficient DNA binding of this isoform (in the presence of Exd) may bypass the requirement for a cofactor or displace a repressor more effectively.

Recently, a quantitatively controlled study showed that the levels of Ubx protein are very important to determine the functional outcome of Ubx in vivo (Tour et al. 2005). In this context, our results show that in spite of significant variation across expression levels of UbxIVa protein in different transgenic lines (see above), this isoform is consistently able to produce a similar output in terms of dpp target activation in posterior regions. This suggests that for UbxIVa dpp target activation and protein concentration may relate to one another in the form of a sigmoidal function (Tour et al. 2005) with a narrow protein concentration interval acting as a threshold that is crossed by all UbxIVa lines tested here. Given that UbxIa lines achieving comparable protein expression levels to UbxIVa lines (see Figure S1, Figure S2, and Figure S3) were not able to activate dpp in posterior regions of the embryo, we conclude that qualitative differences in Ubx protein structure as determined by alternative splicing are causal to the observed differential behavior in target activation.

The tissue-specific effects of Ubx isoform ectopic expression emphasize the likely role that the splice isoforms play in mediating specific Ubx functions in different tissues. Indeed, the isoforms have different tissue distributions in embryogenesis with UbxIa expressed predominantly in epidermis, mesoderm, and peripheral nervous system whereas UbxIVa appears to be exclusively expressed in the central nervous system (Lopez and Hogness 1991). Our analysis of the UbxMX17 mutation, which retains the full Ubx expression pattern but generates only isoform UbxIVa, supports the endogenous relevance of splice isoforms for tissue-specific Hox function. Although in UbxMX17 embryos UbxIVa can replace the function of Ubx isoforms I and II in the epidermis with the generation of a normal cuticle pattern (Busturia et al. 1990), the peripheral nervous system is affected (Subramaniam et al. 1994) and here we find clear defects in the segmental specification of somatic muscles (Figure 4). Tissue-specific isoform functions may be mediated by effects on cofactor interaction (as discussed below) or may also involve effects on collaborative regulatory interactions between Hox proteins and tissue-specific regulators (White et al. 2000; Walsh and Carroll 2007).

The roles of the hexapeptide and the linker region in Hox/Exd interactions:

The results of our in vitro binding studies of the Ubx/Exd element show that Ubx isoforms differ in their capacity to interact with DNA in the presence of the cofactor Exd. A possibility that emerges from these results is that different Ubx isoforms display differential levels of interaction with Exd (in the presence of target DNA) and, accordingly, could perform specific functions in vivo as a consequence to the distinct levels of nuclear Exd available in different regions of the embryo.

Our in vitro studies also show that ablation of the YPWM motif has little effect on the ability of Ubx form Ia to form a complex with Exd, but it significantly reduces complex formation by Ubx form IVa.

The observation that mutated forms of the Ubx protein lacking the hexapeptide interact with Exd at all is at first sight surprising, especially in view of the structural studies showing that the YPWM motif provides the major contact between Hox and Exd proteins bound to DNA (Passner et al. 1999). However, this finding is not inconsistent with earlier work. The article that originally described cooperative interactions between Ubx and Exd used Ubx proteins deleted of all sequences located amino-terminal to the homeodomain. These proteins therefore lacked the hexapeptide motif entirely (Chan et al. 1994) (see Figure 1). Interactions with Exd that do not require the hexapeptide have also been reported in a recent study focused on Ubx functions independent from Exd and Hth proteins (Galant et al. 2002). In addition, alanine replacement of the hexapeptide does not affect the way another Hox protein (i.e., Abd-A) interacts with Exd (Merabet et al. 2003). Furthermore, a recent study (Merabet et al. 2007) suggests that Ubx–Exd recruitment may rely not on a single, but on several different mechanisms, some of which require a short evolutionarily conserved motif originally termed UbdA (Chan and Mann 1993). Thus, the hexapeptide is unlikely to be the only Hox protein motif that interacts with Exd.

Crystallographic studies show that the Ubx and Exd homeodomains are closely adjacent, almost touching each other, the extent of this proximity being revealed by a significant reduction in solvent-accessible surface area within the area of putative contact (Passner et al. 1999). In addition, the distance between the Ubx recognition helix C terminus and the Exd recognition helix N terminus is just 9 Å, with one particular residue of Ubx (Lys58) well positioned to form hydrogen bonds with a residue of Exd (Ser48) (Passner et al. 1999). Thus, regions within the Ubx homeodomain may be responsible for additional interactions with Exd. Sequences elsewhere in the proteins may also contribute to these interactions (Chan et al. 1994; Passner et al. 1999). A fine combination of protein mapping and crystallographic studies may be required to reveal the structural details of such interactions.

Our experiments would be consistent with the possibility that the Ubx linker region itself could be a previously uncharacterized region of Ubx that makes contacts with Exd. This would be supported by experiments of protein–protein interaction in yeast, which also suggest that the Ubx linker region could affect the interaction between Ubx and Exd (Johnson et al. 1995), and by the high evolutionary conservation of these sequences across phylogenetically distant species of flies. Our results could also be accommodated in a model in which the Ubx linker region induces a conformational change elsewhere in the Ubx protein, such that—as suggested above—the degree of interaction with Exd is affected. Alternatively, the regulatory potential of the Ubx protein could be affected. In particular, linker-dependent conformational changes may affect the behavior of critical regulatory motifs of Ubx, such as the recently studied QA motif involved in the modulation of Ubx activities in a tissue-specific manner (Hittinger et al. 2005) and the SSYF motif, an evolutionarily conserved motif close to the N terminus of the Ubx protein that is involved in transcriptional activation (Tour et al. 2005).

Other reports have also emphasized that the Hox linker regions are not just passive spacers. One such study shows that mutation of the short linker region in the Hox protein Abd-A specifically disables its capacity to activate wingless, a natural target gene, without affecting its ability to repress dpp (Merabet et al. 2003). When comparing cofactor and DNA-binding properties of this Abd-A mutant protein with those of the wild-type Abd-A on a repressor element of the Distalless gene (DllR), no differences were seen in the interaction between the mutant form of Abd-A and Exd protein; see Figure 1, C and D, in Merabet et al. (2003). (It is perhaps worth noting that these in vitro experiments required the presence of Homothorax protein; on this particular DNA target (DllR), the formation of complexes with Abd-A and Exd alone was below the limit of detection of the assay.) Another report described Ubx isoform-specific functions for the repression of the Dll gene (Gebelein et al. 2002). These studies suggest that sequences within the Hox linker regions may modify the trans-regulatory potential of Hox proteins without necessarily affecting the DNA-binding properties of these proteins. Our results extend these studies, showing that linker regions may at times affect target gene regulation and the DNA binding/cofactor interaction abilities of a Hox protein. Our binding results are consistent with a recent study that integrates DNA-binding tests with computational predictions of ordered and disordered segments of the Ubx protein, proposing that sequences outside the homeodomain can reduce the DNA-binding activities of the Ubx protein by twofold (Liu et al. 2008b).

The general role of alternative splicing on Hox specificity:

Beyond the effects that alternative splicing may have on modulating Hox interactions with cofactors, other possibilities must also be considered. Given that in our experiments we observe a very unstable binding of the Ubx proteins to target DNA in the absence of Exd, it is difficult to advance arguments regarding the affinities of the individual Ubx isoforms for this molecular target on firm grounds. In spite of this, given that in various physiological contexts the binding of Hox proteins to target sites in the absence of cofactors has been demonstrated (Pinsonneault et al. 1997; Pederson et al. 2000), it is pertinent to suggest that alternative splicing might also be influencing Hox DNA binding independently from cofactor interactions, at the level of changing DNA-binding affinities of the individual isoforms for their target DNAs. This possibility would be suitable for experimental investigation in the physiological context of Drosophila adult appendage development, as Ubx is known to act independently from cofactors during the development of these structures (Rauskolb et al. 1995; Abu-Shaar and Mann 1998; Azpiazu and Morata 1998; Casares and Mann 1998, 2000).

Examples from other Drosophila Hox genes further support a more general role of differential splicing in the diversification of Hox function during development, affecting protein modules outside the Ubx linker region discussed above. For instance, genetic dissection of the Abd-B gene demonstrated the existence of two distinct gene functions, originally termed morphogenetic (m) and regulatory (r) (Casanova et al. 1986; Casanova and White 1987). Kuziora and McGinnis (1988) and Zavortink and Sakonju (1989) cloned the spectrum of mRNAs derived from the Abd-B locus and revealed a family of Abd-B transcripts generated by differential promoter use, which, in turn, leads to different splicing variants affecting 5′ sequences of the gene. Two proteins products, called m and r, are produced from the Abd-B transcripts (Celniker et al. 1989); m differs from r in that it encodes an additional large glutamine-rich amino-terminal domain. Furthermore, Kuziora (1993) showed that ectopic expression of each Abd-B protein class leads to specific effects on the larval cuticle, suggesting that the isoforms have specific developmental functions.

Given that in Drosophila several Hox proteins possess alternatively spliced modules modifying the distance between the hexapeptide and the homeodomain (Figure 1), while others produce functionally different isoforms via differential promoter use coupled to alternative splicing (Kuziora and McGinnis 1988; Zavortink and Sakonju 1989; Kuziora 1993), alternative splicing may truly represent a very important, yet underexplored regulatory mechanism modulating the functional specificity of Hox proteins during development.

Acknowledgments

We thank Ron Galant for discussion of DNA-binding experiments and Richard Mann for Exd cDNAs. We also thank the constructive criticisms of two anonymous reviewers whose comments improved the quality of this article. This work was supported by a Medical Research Council (United Kingdom) studentship to H.C.R., by funding from the Medical Research Council (United Kingdom) to R.A.H.W., by a grant from the Wellcome Trust to M.A., and by a New Investigator Grant from the Biotechnology and Biological Sciences Research Council (nos. BB/E01173X/1 and BB/E01173X/2) to C.R.A.

Supporting information is available online at http://www.genetics.org/cgi/content/full/genetics.109.112086/DC1.

References

- Abu-Shaar, M., and R. S. Mann, 1998. Generation of multiple antagonistic domains along the proximodistal axis during Drosophila leg development. Development 125 3821–3830. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Abu-Shaar, M., H. D. Ryoo and R. S. Mann, 1999. Control of the nuclear localization of Extradenticle by competing nuclear import and export signals. Genes Dev. 13 935–945. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Akam, M., 1998. Hox genes, homeosis and the evolution of segment identity: no need for hopeless monsters. Int. J. Dev. Biol. 42 445–451. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Akam, M. E., and A. Martinez-Arias, 1985. The distribution of Ultrabithorax transcripts in Drosophila embryos. EMBO J. 4 1689–1700. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Akam, M. E., A. Martinez-Arias, R. Weinzierl and C. D. Wilde, 1985. Function and expression of ultrabithorax in the Drosophila embryo. Cold Spring Harbor Symp. Quant. Biol. 50 195–200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alonso, C. R., 2002. Hox proteins: sculpting body parts by activating localized cell death. Curr. Biol. 12 R776–R778. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alonso, C. R., and A. S. Wilkins, 2005. The molecular elements that underlie developmental evolution. Nat. Rev. Genet. 6 709–715. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aspland, S. E., and R. A. White, 1997. Nucleocytoplasmic localisation of extradenticle protein is spatially regulated throughout development in Drosophila. Development 124 741–747. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Azpiazu, N., and G. Morata, 1998. Functional and regulatory interactions between Hox and extradenticle genes. Genes Dev. 12 261–273. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bate, M., 1993. The mesoderm and its derivatives, pp. 1013–1090 in The Development of Drosophila melanogaster, edited by M. Bate and A. Martinez-Arias. Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press, Cold Spring Harbor, NY.

- Beachy, P. A., S. L. Helfand and D. S. Hogness, 1985. Segmental distribution of bithorax complex proteins during Drosophila development. Nature 313 545–551. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bienz, M., and G. Tremml, 1988. Domain of Ultrabithorax expression in Drosophila visceral mesoderm from autoregulation and exclusion. Nature 333 576–578. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bomze, H. M., and A. J. Lopez, 1994. Evolutionary conservation of the structure and expression of alternatively spliced Ultrabithorax isoforms from Drosophila. Genetics 136 965–977. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brand, A. H., and N. Perrimon, 1993. Targeted gene expression as a means of altering cell fates and generating dominant phenotypes. Development 118 401–415. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Branden, C., and J. Tooze, 1999. Introduction to Protein Structure. Garland, New York.

- Burnette, J. M., A. R. Hatton and A. J. Lopez, 1999. Trans-acting factors required for inclusion of regulated exons in the Ultrabithorax mRNAs of Drosophila melanogaster. Genetics 151 1517–1529. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Busturia, A., I. Vernos, A. Macias, J. Casanova and G. Morata, 1990. Different forms of Ultrabithorax proteins generated by alternative splicing are functionally equivalent. EMBO J. 9 3551–3555. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Capovilla, M., and J. Botas, 1998. Functional dominance among Hox genes: repression dominates activation in the regulation of Dpp. Development 125 4949–4957. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Capovilla, M., M. Brandt and J. Botas, 1994. Direct regulation of decapentaplegic by Ultrabithorax and its role in Drosophila midgut morphogenesis. Cell 76 461–475. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carroll, S. B., J. K. Grenier and S. D. Weatherbee, 2001. From DNA to Diversity. Blackwell Science, London.

- Casanova, J., and R. A. White, 1987. Trans-regulatory functions in the Abdominal-B gene of the bithorax complex. Development 101 117–122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Casanova, J., E. Sanchez-Herrero and G. Morata, 1986. Identification and characterization of a parasegment specific regulatory element of the abdominal-B gene of Drosophila. Cell 47 627–636. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Casares, F., and R. S. Mann, 1998. Control of antennal versus leg development in Drosophila. Nature 392 723–726. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Casares, F., and R. S. Mann, 2000. A dual role for homothorax in inhibiting wing blade development and specifying proximal wing identities in Drosophila. Development 127 1499–1508. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Celniker, S. E., D. J. Keelan and E. B. Lewis, 1989. The molecular genetics of the bithorax complex of Drosophila: characterization of the products of the Abdominal-B domain. Genes Dev. 3 1424–1436. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chan, S. K., and R. S. Mann, 1993. The segment identity functions of Ultrabithorax are contained within its homeo domain and carboxy-terminal sequences. Genes Dev. 7 796–811. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chan, S. K., L. Jaffe, M. Capovilla, J. Botas and R. S. Mann, 1994. The DNA binding specificity of Ultrabithorax is modulated by cooperative interactions with extradenticle, another homeoprotein. Cell 78 603–615. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chang, C. P., W. F. Shen, S. Rozenfeld, H. J. Lawrence, C. Largman et al., 1995. Pbx proteins display hexapeptide-dependent cooperative DNA binding with a subset of Hox proteins. Genes Dev. 9 663–674. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de la Mata, M., C. R. Alonso, S. Kadener, J. P. Fededa, M. Blaustein et al., 2003. A slow RNA polymerase II affects alternative splicing in vivo. Mol. Cell 12 525–532. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dohrmann, C., N. Azpiazu and M. Frasch, 1990. A new Drosophila homeo box gene is expressed in mesodermal precursor cells of distinct muscles during embryogenesis. Genes Dev. 4 2098–2111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Flegel, W. A., A. W. Singson, J. S. Margolis, A. G. Bang, J. W. Posakony et al., 1993. Dpbx, a new homeobox gene closely related to the human proto-oncogene pbx1 molecular structure and developmental expression. Mech. Dev. 41 155–161. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Galant, R., and S. B. Carroll, 2002. Evolution of a transcriptional repression domain in an insect Hox protein. Nature 415 910–913. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Galant, R., C. M. Walsh and S. B. Carroll, 2002. Hox repression of a target gene: extradenticle-independent, additive action through multiple monomer binding sites. Development 129 3115–3126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gebelein, B., J. Culi, H. D. Ryoo, W. Zhang and R. S. Mann, 2002. Specificity of Distalless repression and limb primordia development by abdominal Hox proteins. Dev. Cell 3 487–498. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gebelein, B., D. J. McKay and R. S. Mann, 2004. Direct integration of Hox and segmentation gene inputs during Drosophila development. Nature 431 653–659. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gonzalez-Reyes, A., and G. Morata, 1990. The developmental effect of overexpressing a Ubx product in Drosophila embryos is dependent on its interactions with other homeotic products. Cell 61 515–522. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gonzalez-Reyes, A., N. Urquia, W. J. Gehring, G. Struhl and G. Morata, 1990. Are cross-regulatory interactions between homoeotic genes functionally significant? Nature 344 78–80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gould, A. P., and R. A. White, 1992. Connectin, a target of homeotic gene control in Drosophila. Development 116 1163–1174. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Graba, Y., D. Aragnol and J. Pradel, 1997. Drosophila Hox complex downstream targets and the function of homeotic genes. BioEssays 19 379–388. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greig, S., and M. Akam, 1993. Homeotic genes autonomously specify one aspect of pattern in the Drosophila mesoderm. Nature 362 630–632. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hatton, A. R., V. Subramaniam and A. J. Lopez, 1998. Generation of alternative Ultrabithorax isoforms and stepwise removal of a large intron by resplicing at exon-exon junctions. Mol. Cell 2 787–796. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Higuchi, R., B. Krummel and R. K. Saiki, 1988. A general method of in vitro preparation and specific mutagenesis of DNA fragments: study of protein and DNA interactions. Nucleic Acids Res. 16 7351–7367. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hittinger, C. T., D. L. Stern and S. B. Carroll, 2005. Pleiotropic functions of a conserved insect-specific Hox peptide motif. Development 132 5261–5270. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holland, P. W., and J. Garcia-Fernandez, 1996. Hox genes and chordate evolution. Dev. Biol. 173 382–395. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hooper, J. E., 1986. Homeotic gene function in the muscles of Drosophila larvae. EMBO J. 5 2321–2329. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hughes, C. L., and T. C. Kaufman, 2002. Hox genes and the evolution of the arthropod body plan. Evol. Dev. 4 459–499. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hursh, D. A., R. W. Padgett and W. M. Gelbart, 1993. Cross regulation of decapentaplegic and Ultrabithorax transcription in the embryonic visceral mesoderm of Drosophila. Development 117 1211–1222. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Immergluck, K., P. A. Lawrence and M. Bienz, 1990. Induction across germ layers in Drosophila mediated by a genetic cascade. Cell 62 261–268. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson, F. B., E. Parker and M. A. Krasnow, 1995. Extradenticle protein is a selective cofactor for the Drosophila homeotics: role of the homeodomain and YPWM amino acid motif in the interaction. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 92 739–743. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Knoepfler, P. S., and M. P. Kamps, 1995. The pentapeptide motif of Hox proteins is required for cooperative DNA binding with Pbx1, physically contacts Pbx1, and enhances DNA binding by Pbx1. Mol. Cell. Biol. 15 5811–5819. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kornfeld, K., R. B. Saint, P. A. Beachy, P. J. Harte, D. A. Peattie et al., 1989. Structure and expression of a family of Ultrabithorax mRNAs generated by alternative splicing and polyadenylation in Drosophila. Genes Dev. 3 243–258. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuziora, M. A., 1993. Abdominal-B protein isoforms exhibit distinct cuticular transformations and regulatory activities when ectopically expressed in Drosophila embryos. Mech. Dev. 42 125–137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuziora, M. A., and W. McGinnis, 1988. Different transcripts of the Drosophila Abd-B gene correlate with distinct genetic sub-functions. EMBO J. 7 3233–3244. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lamka, M. L., A. M. Boulet and S. Sakonju, 1992. Ectopic expression of UBX and ABD-B proteins during Drosophila embryogenesis: competition, not a functional hierarchy, explains phenotypic suppression. Development 116 841–854. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lewis, E. B., 1978. A gene complex controlling segmentation in Drosophila. Nature 276 565–570. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu, J., and A. Fire, 2000. Overlapping roles of two Hox genes and the exd ortholog ceh-20 in diversification of the C. elegans postembryonic mesoderm. Development 127 5179–5190. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu, J., L. Qian, Z. Han, X. Wu and R. Bodmer, 2008. a Spatial specificity of mesodermal even-skipped expression relies on multiple repressor sites. Dev. Biol. 313 876–886. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu, Y., K. S. Matthews and S. E. Bondos, 2008. b Multiple intrinsically disordered sequences alter DNA binding by the homeodomain of the Drosophila hox protein ultrabithorax. J. Biol. Chem. 283 20874–20887. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lopez, A. J., and D. S. Hogness, 1991. Immunochemical dissection of the Ultrabithorax homeoprotein family in Drosophila melanogaster. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 88 9924–9928. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Manak, J. R., L. D. Mathies and M. P. Scott, 1994. Regulation of a decapentaplegic midgut enhancer by homeotic proteins. Development 120 3605–3619. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mann, R. S., 1995. The specificity of homeotic gene function. BioEssays 17 855–863. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mann, R. S., and M. Affolter, 1998. Hox proteins meet more partners. Curr. Opin. Genet. Dev. 8 423–429. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mann, R. S., and S. K. Chan, 1996. Extra specificity from extradenticle: the partnership between HOX and PBX/EXD homeodomain proteins. Trends Genet. 12 258–262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mann, R. S., and D. S. Hogness, 1990. Functional dissection of Ultrabithorax proteins in D. melanogaster. Cell 60 597–610. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matlin, A. J., F. Clark and C. W. Smith, 2005. Understanding alternative splicing: towards a cellular code. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell. Biol. 6 386–398. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McGinnis, W., and R. Krumlauf, 1992. Homeobox genes and axial patterning. Cell 68 283–302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McGinnis, W., R. L. Garber, J. Wirz, A. Kuroiwa and W. J. Gehring, 1984. a A homologous protein-coding sequence in Drosophila homeotic genes and its conservation in other metazoans. Cell 37 403–408. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McGinnis, W., M. S. Levine, E. Hafen, A. Kuroiwa and W. J. Gehring, 1984. b A conserved DNA sequence in homoeotic genes of the Drosophila Antennapedia and bithorax complexes. Nature 308 428–433. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meadows, L. A., D. Gell, K. Broadie, A. P. Gould and R. A. White, 1994. The cell adhesion molecule, connectin, and the development of the Drosophila neuromuscular system. J. Cell Sci. 107(Pt. 1): 321–328. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Merabet, S., Z. Kambris, M. Capovilla, H. Berenger, J. Pradel et al., 2003. The hexapeptide and linker regions of the AbdA Hox protein regulate its activating and repressive functions. Dev. Cell 4 761–768. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Merabet, S., M. Saadaoui, N. Sambrani, B. Hudry, J. Pradel et al., 2007. A unique Extradenticle recruitment mode in the Drosophila Hox protein Ultrabithorax. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 104 16946–16951. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mercader, N., E. Leonardo, N. Azpiazu, A. Serrano, G. Morata et al., 1999. Conserved regulation of proximodistal limb axis development by Meis1/Hth. Nature 402 425–429. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Michelson, A. M., 1994. Muscle pattern diversification in Drosophila is determined by the autonomous function of homeotic genes in the embryonic mesoderm. Development 120 755–768. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morata, G., and S. Kerridge, 1981. Sequential functions of the bithorax complex of Drosophila. Nature 290 778–781. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nose, A., V. B. Mahajan and C. S. Goodman, 1992. Connectin: a homophilic cell adhesion molecule expressed on a subset of muscles and the motoneurons that innervate them in Drosophila. Cell 70 553–567. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O'Connor, M. B., R. Binari, L. A. Perkins and W. Bender, 1988. Alternative RNA products from the Ultrabithorax domain of the bithorax complex. EMBO J. 7 435–445. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pai, C. Y., T. S. Kuo, T. J. Jaw, E. Kurant, C. T. Chen et al., 1998. The Homothorax homeoprotein activates the nuclear localization of another homeoprotein, extradenticle, and suppresses eye development in Drosophila. Genes Dev. 12 435–446. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Passner, J. M., H. D. Ryoo, L. Shen, R. S. Mann and A. K. Aggarwal, 1999. Structure of a DNA-bound Ultrabithorax-Extradenticle homeodomain complex. Nature 397 714–719. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pearson, J. C., D. Lemons and W. McGinnis, 2005. Modulating Hox gene functions during animal body patterning. Nat. Rev. Genet. 6 893–904. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pederson, J. A., J. W. LaFollette, C. Gross, A. Veraksa, W. McGinnis et al., 2000. Regulation by homeoproteins: a comparison of deformed-responsive elements. Genetics 156 677–686. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pinsonneault, J., B. Florence, H. Vaessin and W. McGinnis, 1997. A model for extradenticle function as a switch that changes HOX proteins from repressors to activators. EMBO J. 16 2032–2042. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ponzielli, R., M. Astier, A. Chartier, A. Gallet, P. Therond et al., 2002. Heart tube patterning in Drosophila requires integration of axial and segmental information provided by the Bithorax Complex genes and hedgehog signaling. Development 129 4509–4521. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Popperl, H., M. Bienz, M. Studer, S. K. Chan, S. Aparicio et al., 1995. Segmental expression of Hoxb-1 is controlled by a highly conserved autoregulatory loop dependent upon exd/pbx. Cell 81 1031–1042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rauskolb, C., and E. Wieschaus, 1994. Coordinate regulation of downstream genes by extradenticle and the homeotic selector proteins. EMBO J. 13 3561–3569. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rauskolb, C., M. Peifer and E. Wieschaus, 1993. Extradenticle, a regulator of homeotic gene activity, is a homolog of the homeobox-containing human proto-oncogene pbx1. Cell 74 1101–1112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rauskolb, C., K. M. Smith, M. Peifer and E. Wieschaus, 1995. Extradenticle determines segmental identities throughout Drosophila development. Development 121 3663–3673. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rieckhof, G. E., F. Casares, H. D. Ryoo, M. Abu-Shaar and R. S. Mann, 1997. Nuclear translocation of extradenticle requires homothorax, which encodes an extradenticle-related homeodomain protein. Cell 91 171–183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ronshaugen, M., N. McGinnis and W. McGinnis, 2002. Hox protein mutation and macroevolution of the insect body plan. Nature 415 914–917. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rubin, G. M., and A. C. Spradling, 1982. Genetic transformation of Drosophila with transposable element vectors. Science 218 348–353. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ryoo, H. D., and R. S. Mann, 1999. The control of trunk Hox specificity and activity by Extradenticle. Genes Dev. 13 1704–1716. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]