Abstract

Background

Women’s long-term patterns of evidence-based preventive medication utilization following a coronary heart disease (CHD) diagnosis have not been sufficiently studied.

Methods

Postmenopausal women 50–79 years were eligible for randomization in the Women’s Health Initiative’s (WHI) hormone trials if they met inclusion and exclusion criteria and were >80% adherent during a placebo-lead-in period and in the dietary modification trial if they were willing to follow a 20% fat diet. Those with adjudicated myocardial infarction or coronary revascularization after the baseline visit were included in the analysis (n=2627). Baseline visits occurred between 1993 and 1998, then annually until the trials ended in 2002 through 2005; medication inventories were obtained at baseline and years 1, 3, 6 and 9.

Results

Utilization at the first WHI visit following a CHD diagnosis increased over time for statins (49% to 72%; p<0.0001), beta-blockers (49% to 62%; p=0.003), and angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors/angiotensin-II receptor blockers (ACEI/ARBs ) [26 to 43%; p<0.0001]. Aspirin use remained stable at 76% (p=0.09). Once women reported using a statin, aspirin, or beta-blocker, 84–89% reported use at 1 or more subsequent visits, with slightly lower rates for ACEI/ARBS (76%). Statin, aspirin, beta-blocker, or ACEI/ARB use was reported at 2 or more consecutive visits by 57%, 66%, 48%, and 28% respectively. These drugs were initiated or resumed at a later visit by 24%, 17%, 15%, and 17%, respectively, and were never used during the period of follow-up by 19%, 10%, 33%, and 49% respectively.

Conclusions

Efforts to improve secondary prevention medication utilization should target both drug initiation and restarting drugs in patients who have discontinued them.

Keywords: Secondary prevention, Adherence, Statins, Women, Coronary heart disease

Extensive clinical trial evidence demonstrates that statins, aspirin, beta-blockers, angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors (ACE) and angiotensin-II receptor blockers (ARB) in patients with coronary heart disease (CHD) can substantially reduce the risk of heart attack, stroke, and all-cause mortality by 16% to 63%.1 Declining cardiovascular mortality in the elderly is largely attributed to these evidence-based therapies.2 Current guidelines recommend statins and low-dose aspirin for the vast majority of patients with CHD as well as other vascular disease.3 Beta-blockers are indicated following MI and acute coronary syndromes. For hypertensive CHD patients, blood pressure control with beta-blockers, ACE inhibitors, and other drugs such as thiazides is recommended. ACE-inhibitors are further recommended for those with impaired left ventricular function, diabetes, or chronic kidney disease.

The long-term survival advantages associated with improved statin and beta-blocker adherence after acute myocardial infarction appear to be mediated by drug effects rather than an epiphenomenon of “healthy adherer” behavioral attributes.4 Although substantial progress has been made over the past four decades,5 significant treatment gaps still exist in the use of secondary prevention medications. The highest risk patients, those with coronary heart disease (CHD) over age 65, experience the largest treatment gaps.6 Since drug utilization rates decline significantly over time, long term control of multiple risk factors is rare.7

Some data suggest women with CHD have lower rates of secondary prevention medication use than men.8 We therefore evaluated the large cohort of women with CHD participating in the Women’s Health Initiative (WHI) Clinical Trials in order to describe trends in long-term utilization of secondary prevention medications. These studies provided a unique opportunity to describe drug utilization patterns over 9 years in older women selected for adherence before enrollment in the WHI hormone and/or dietary modification trials. Women were randomized in the hormone trials if, after meeting eligibility criteria, they were >80% adherent by pill count during a 28-day placebo lead-in period. 9 Women were randomized in the dietary modification trial if t they met eligibility criteria and were willing to change their eating patterns by greatly reducing dietary fat intake and increasing fruit/vegetable and grain intake.10

Methods

Study population

This was a post hoc analysis of data collected for the WHI clinical trials. Details of the study design, eligibility criteria, recruitment methods, methodology, and baseline characteristics have been previously published for the WHI’s hormone and Dietary Modification clinical trials.9–11 Briefly, between 1993 and 1998, 40 clinical centers throughout the United States recruited a multiethnic population of postmenopausal women aged 50 to 79 years for participation in trials of postmenopausal hormone therapy, dietary modification, and calcium and vitamin D supplementation. Participants were recruited primarily through mass mailings to age-eligible women. Major exclusions for the hormone trials included conditions related to safety, competing risk, and adherence and retention concerns. Eligible women (n=10,739) who had undergone a hysterectomy were randomly assigned to receive 0.625 mg/d of oral conjugated equine estrogen (CEE) [Premarin; Wyeth, St. Davids, Pa] or a matching placebo (E-Alone trial).12 Eligible women (n=16,608) with an intact uterus were randomized to receive 0.625 mg of oral CEE and 2.5 mg of medroxyprogesterone acetate (MPA) [Prempro; Wyeth, St. Davids, Pa] or 0.625 mg of CEE alone or a matching placebo (E+P trial). The Diet Modification trial randomized 48,835 women to a low-fat eating pattern (40%) or a self-selected dietary behavior (60%).10 Major exclusions from the dietary modification trial were a diet <32% fat, incompatible medical conditions, frequent restaurant dining, and a history of breast or colon cancer. A total of 8,050 women participated in both the diet and hormone trials. The protocol and consent forms were approved by the institutional review boards for all participating institutions. We analyzed baseline and annual visits 1, 3, 6, and 9 as of the termination dates for the Hormone Trials (July, 2002 for the E+P trial; February 29, 2004 for the E-alone trial; and March, 2005 for the Diet Modification trial). Baseline and annual visits occurred in overlapping time intervals (baseline: 9/14/1993 to 8/4/1998; visit 1: 11/1/1994 to 11/22/2000; visit 3: 11/11/1996 to 2/21/2003; visit 6: 11/1/1999 to 2/1/5/2005; and visit 9: 11/14/2002 to 11/8/2004). Women in the E+P trial were followed for an average of 5.2 years, those in the E-alone trial for 6.8 years, and the Diet Modification for 8.1 years.12–14

Women without self-reported CHD at baseline who experienced an adjudicated CHD event prior to their last WHI visit were included in the main analysis. CHD events were defined as the first of either a myocardial infarction or coronary revascularization (percutaneous transluminal coronary angioplasty/stent or coronary artery bypass surgery). Methods for CHD event ascertainment have been described elsewhere.14 In brief, medical records including electrocardiograms, cardiac enzymes, procedure reports and discharge summaries from women reporting an overnight hospitalization were reviewed by local or central adjudicators. The first myocardial infarction or revascularization outcome was centrally adjudicated by trained physicians using standard diagnostic criteria in the hormone trials; non-hormone trial Diet Modification events were locally adjudicated.15 Additional analyses in all first MIs and in all first revascularizations evaluated medication utilization.

An additional analysis evaluated medication utilization patterns in women reporting incident CHD to their last WHI visit. Self-reported CHD was defined as a “yes” answer to one of the questions, “Has your doctor ever told you that you had heart problems?”; If yes, “Please mark the conditions or procedures below that your doctor said you had: cardiac arrest (where your heart stopped and needed to be restarted)/heart failure or congestive heart failure/cardiac catheterization/heart bypass operation or coronary bypass surgery for blocked or clogged arteries in your heart/angioplasty of the coronary arteries (opening of the arteries of the heart with a balloon or other device, sometimes called a PTCA)”; “Did your doctor ever say that you had a heart attack? This is sometimes called a coronary, myocardial infarction, or MI.”; or “Did your doctor ever say you had angina (chest pains from a heart problem)?”. Self-report of CHD was considered to be the more appropriate measure of a woman’s perception of her health status and need for medications.

Women were asked to bring all current prescription and nonprescription medications in their original containers to the baseline and year 1, 3, 6, and 9 clinic visits. Trained personnel entered the product or generic name of the medications on the label into the study database and then matched it to the corresponding item in a pharmacy database [Master Drug Data Base: Medi-Span, Indianapolis, IN]. The 7 classes of cardiovascular medications evaluated in this analysis were aspirin, statins, beta-blockers, angiotensin-converting enzyme (ACE) inhibitors, angiotensin II receptor blockers (ARB), calcium channel blockers, and other antihypertensive agents (including thiazide-type diuretics, antiadrenergic agents, and thiazide-combinations and other antihypertensive combinations). Aspirin use was defined as ≥80 mg per day for at least 30 days. Visits subsequent to the first CHD event were evaluated for medication use. Use at 2 consecutive visits was evaluated only in those attending 2 or more visits after the first CHD event.

Statistical analysis

The purpose of this paper is primarily descriptive. Baseline characteristics were compared across the three mutually exclusive WHI trial groups using chi-square tests and F-tests for differences within the category. Trends in medication use over the follow-up period are displayed graphically using only the first visit after the CHD diagnosis. Frequency of each type of medication use was determined at all available visits after the CHD self-report. Frequencies were computed as the number of women with CHD reporting medication use, divided by the total number of women with CHD at a given visit. Statistical comparisons were made within a drug class, but not between drug classes since many participants were taking more than one drug. Similarly no statistical comparisons were made between those with myocardial infarctions and those with revascularizations, since 33% had both. Ninety-five percent confidence intervals for each reported percentage were based on a binomial distribution. P-values <0.05 were considered significant. SAS version 9.1 was used for the analysis.16

Results

Baseline characteristics of the 2627 participants with incident CHD in each of the 3 clinical trials are presented in Table 1. More than half of the women with incident CHD were enrolled only in the Diet Modification trial. The greatest proportion of minority women were in the E-alone trial. Other baseline demographic characteristics were modestly different among the 3 studies. Risk factor levels differed significantly among the 3 trials, with women in the E-alone trial having the highest frequency of risk factors and women in the E+P trial having the lowest risk factor burden. Women in the Diet Modification trial had the highest rates of insurance, doctor visits in the past year, income level, and number of total medications. The rates of medication utilization at each visit, persistence of use, and discontinuation were very similar for women in the hormone and the diet modification trials (data not shown), supporting the combination of the 3 trials for the analysis.

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics of older women with adjudicated CHD during participation in the Women’s Health Initiative Hormone and Diet Modification Trials

| All N=2627 N (%) |

E+P N=659 (25%) N (%) |

E-Alone N=528 (20%) N (%) |

Diet only N=1440 (55%) N (%) |

p-value | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age | 50–59 | 494 (19) | 128 (19) | 90 (17) | 276(19) | 0.60 |

| 60–69 | 1283 (49) | 317 (48) | 254 (48) | 712 (49) | ||

| 70–79 | 850 (32) | 214 (32) | 184 (35) | 452 (31) | ||

| Region | Midwest | 621 (24) | 181 (27) | 140 (27) | 300 (21) | <0.0001 |

| Northeast | 652 (25) | 156 (24) | 110 (21) | 386 (27) | ||

| South | 710 (27) | 171 (26) | 168 (32) | 371 (26) | ||

| West | 644 (25) | 151 (23) | 110 (21) | 383 (27) | ||

| Race/ethnicity | American Indian | 10 (0.4) | 1 (0.1) | 3 (1) | 6 (0.4) | <0.0001 |

| Asian/Pacific Islander | 33(1) | 10 (2) | 5 (1) | 18 (1) | ||

| Black | 228 (9) | 40 (6) | 58 (11) | 130 (9) | ||

| Hispanic | 71 (3) | 26 (4) | 24 (5) | 21 (1) | ||

| White | 2248 (86) | 568 (86) | 431 (82) | 1249 (87) | ||

| Unknown | 37 (1) | 14 (2) | 7 (1) | 16 (1) | ||

| Stroke | 59 (2) | 12 (2) | 18 (3) | 29 (2) | 0.13 | |

| Peripheral arterial disease | 75 (3) | 17 (3) | 17 (3) | 41 (3) | 0.80 | |

| Diabetes | 439 (17) | 110 (17) | 114 (22) | 215 (15) | 0.002 | |

| Hypertension | Yes - treated | 957 (42) | 206 (35) | 190 (41) | 561 (45) | 0.002 |

| Yes - untreated | 221 (10) | 68 (12) | 50 (11) | 103 (8) | ||

| Smoking | Current | 304 (12) | 96 (15) | 88 (17) | 120 (8) | <0.0001 |

| Never | 1240 (48) | 290 (45) | 262 (50) | 688 (48) | ||

| Past | 1047 (40) | 261 (40) | 172 (33) | 614 (43) | ||

| BMI | <25 | 552 (21) | 164 (25) | 102 (19) | 286 (20) | 0.08 |

| 25–<30 | 951 (36) | 234 (36) | 192 (36) | 525 (37) | ||

| ≥30 | 1120 (43) | 261 (40) | 234 (44) | 625 (44) | ||

| Insurance coverage | 2481 (95) | 611 (93) | 479 (93) | 1391 (97) | <0.0001 | |

| Doctor visit in past year | 2106 (83) | 509 (79) | 396 (79) | 1201 (86) | <0.0001 | |

| Income | <$10,000 | 144 (6) | 27 (4) | 55 (11) | 62 (6) | <0.0001 |

| $10,000–<20,000 | 528 (21) | 149 (24) | 146 (29) | 233 (17) | ||

| $20,000–<35,000 | 728 (29) | 197 (32) | 134 (26) | 397 (29) | ||

| $35,000–<50,000 | 500 (20) | 112 (18) | 82 (16) | 306 (22) | ||

| $50,000–<75,000 | 376 (15) | 86 (14) | 69 (14) | 221 (16) | ||

| ≥$75,000 | 213 (9) | 50 (8) | 20 (4) | 143 (11) | ||

| Number of medications | 0 | 341 (13) | 124 (19) | 75 (14) | 142 (10) | <0.0001 |

| 1 | 419 (16) | 122 (19) | 93 (18) | 204 (14) | ||

| 2 | 470 (18) | 127 (19) | 103 (20) | 240 (17) | ||

| 3 | 378 (14) | 91 (14) | 70 (13) | 217 (15) | ||

| 4 | 355 (14) | 82 (12) | 68 (13) | 205 (14) | ||

| 5 | 230 (9) | 42 (6) | 43 (8) | 145 (10) | ||

| 6–7 | 261 (10) | 43 (7) | 48 (9) | 170 (12) | ||

| ≥8 | 173 (7) | 28 (4) | 28 (5) | 117 (8) |

E+P = Estrogen plus Progestin trial

E-Alone = Estrogen only trial

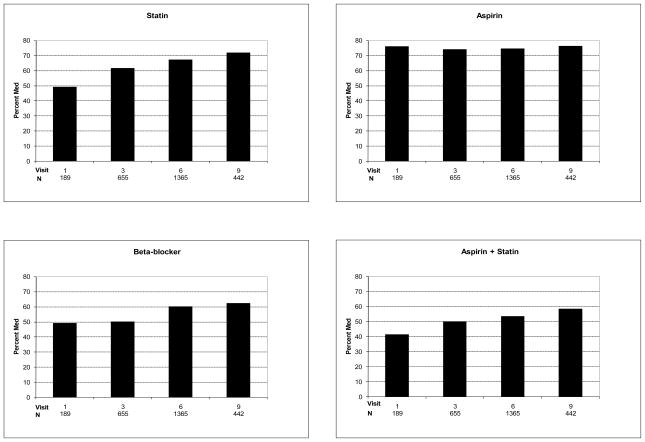

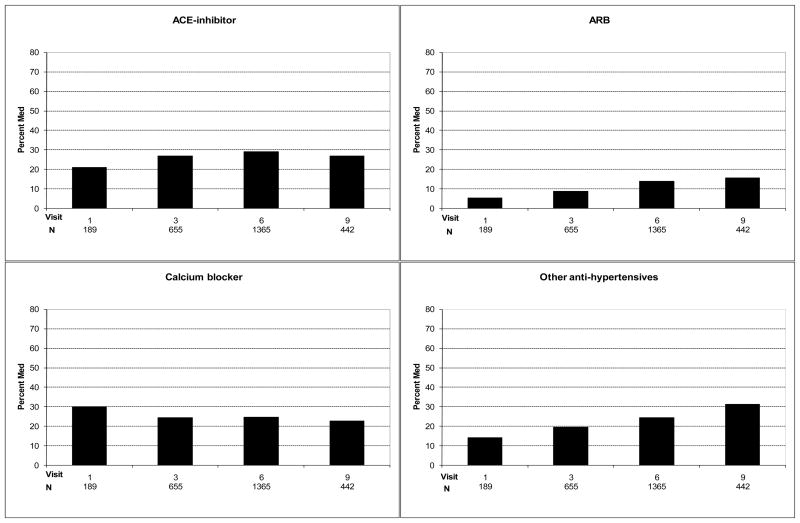

Trends in the prevalence of statin, aspirin, and beta-blocker use at the first visit after CHD diagnosis from1994 to 2004 are presented in Figure 1. Statin use increased from 49% (95% CI 42–57%) to 72% (95% CI 68–76%) over the period of follow-up (47% increase; p for trend <0.0001)), aspirin use stayed stable at 76% (95% CIs 70–82% and 72–80%; p=0.09), and beta-blocker use increased from 49% (95% CI 42–57%) to 62% (95% CI 58–67%) [27% increase; p for trend=0.003]. The concomitant use of a statin and aspirin increased from 41% (95% CI 34–49%) to 58% (54–63%) [41% increase; p for trend <0.0001]. Trends in the use of ACE inhibitors, ARBs, calcium blockers, and other antihypertensives are presented in Figure 2. ACE inhibitor use did not significantly increase [21 (95% CI 16–28%) to 27% (95% CI 23–31%); p for trend 0.39], ARB use increased from 5% (95% CI 3–10%) to 16% (95% CI 12–19%) (220% increase; p for trend <0.0001), and the use of either an ACE or ARB increased from 25% (95% CI 20–38%) to 42% (95% CI 37–47%) [68% increase; p for trend <0.0001]. The use of other antihypertensives increased from 14% (95% CI 10–20%) to 31% (95% CI 30–36%) (121% increase; p for trend <0.0001). Calcium channel blocker use remained stable over time, 30% (95% CI 24–37%) and 23% (95% CI 19–27%) [p for trend 0.35].

Figure 1.

Aspirin, statin, and beta-blocker utilization at first visit following an adjudicated CHD diagnosis

Figure 2.

ACE-inhibitor, ARB, calcium channel blocker and other antihypertensive use at first visit following an adjudicated CHD diagnosis

Table 2 shows the proportion of women at each visit who were taking or not taking a medication. For the 2nd and 3rd visit following CHD diagnosis, the proportion of women attending the visit is displayed to reflect use of the drug at the previous visit and drug use at that visit. Of those on a statin, aspirin, or beta-blocker at the first visit after CHD diagnosis, use was reported in 88%, 84%, and 86%, respectively, at the next visit 2–3 years later (Table 2). Although relatively few of these women had a third visit after CHD diagnosis, 90%, 84%, and 88% were still using a statin, aspirin, or beta-blocker, respectively, at the third visit. Use of an ACE inhibitors or ARB at both the first and second visits was slightly lower at 75–76%.

Table 2.

Proportion of women at each visit who were taking or not taking a secondary prevention medication following an adjudicated CHD diagnosis. For the 2nd and 3rd visit after the first visit following a CHD diagnosis, the proportion of women attending the visit is displayed to reflect use of the drug at the previous visit and drug use at that visit.

| Drug class | On drug at 1st visit after Diagnosis | n/N* Percent (95% CI) attending 1st visit |

On drug at 2nd visit after diagnosis | n/N* Percent (95% CI) attending 2nd visit |

On drug at 3rd visit after diagnosis | n/N* Percent (95% CI) Attending 3rd visit |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Statin | Yes | 1039/1669 62.3 (59.9, 64.6) |

Yes | 371/423 87.7 (84.2, 90.7) |

Yes | 86/96 89.6 (81.7, 94.9) |

| No | 10/96 10.4 (5.1, 18.3) |

|||||

| No | 52/423 12.3 (9.3, 15.8) |

Yes | 10/15 66.7 (38.4, 88.2) |

|||

| No | 5/15 33.3 (11.8, 61.6) |

|||||

| Statin | No | 630/1669 37.8 (35.4, 40.1) |

Yes | 134/298 45.0 (39.2, 50.8) |

Yes | 43/51 84.3 (71.4, 93.0) |

| No | 8/51 15.7 (7.0, 28.6) |

|||||

| No | 164/298 55.0 (49.2, 60.8) |

Yes | 26/65 40.0 (28.0, 52.9) |

|||

| No | 39/65 60.0(47.1, 72.0) |

|||||

| Aspirin | Yes | 1240/1669 74.3 (72.1, 76.4) |

Yes | 456/542 84.1 (80.8, 87.1) |

Yes | 123/147 83.7 (76.7, 89.3) |

| No | 24/147 16.3 (10.8, 23.3) |

|||||

| No | 86/542 15.9 (12.9, 19.2) |

Yes | 16/25 64.0 (42.5, 82.0) |

|||

| No | 9/25 36.0 (18.0, 57.5) |

|||||

| Aspirin | No | 4297/1669 25.7 (23.6, 27.9) |

Yes | 94/179 52.5 (44.9, 60.0) |

Yes | 22/25 88.0 (68.8, 97.5) |

| No | 3/25 12.0 (2.6, 31.2) |

|||||

| No | 85/179 47.5 (40.0, 55.1) |

Yes | 13/30 43.3 (25.5, 62.6) |

|||

| No | 17/30 56.7 (37.4, 74.5) |

|||||

| Beta-blocker | Yes | 965/1669 57.8 (55.4, 60.2) |

Yes | 330/385 85.7 (81.8, 89.1) |

Yes | 88/100 88.0 (80.0, 93.6) |

| No | 12/100 12.0 (6.4, 20.0) |

|||||

| No | 55/385 14.3 (11.0, 18.2) |

Yes | 5/15 33.3 (11.8, 61.6) |

|||

| No | 10/15 66.7 (38.4, 88.2) |

|||||

| Beta-blocker | No | 704/1669 42.2 (39.8, 44.6) |

Yes | 84/336 25.0 (20.5, 30.0) |

Yes | 13/18 72.2 (46.5, 90.3) |

| No | 5/18 27.8 ( 9.7, 53.5) |

|||||

| No | 252/336 75.0 (70.0, 79.5) |

Yes | 17/94 18.1 (10.9, 27.4) |

|||

| No | 77/94 81.9 (72.6, 89.1) |

|||||

| ACEI/ARB | Yes | 667/1669 40.0 (37.6, 42.4) |

Yes | 186/245 75.9 (70.1, 81.1) |

Yes | 39/52 75.0 (61.1, 86.0) |

| No | 13/52 25.0 (14.0, 39.0) |

|||||

| No | 59/245 24.1 (18.9, 29.9) |

Yes | 2/9 22.2 (2.8, 60.0) |

|||

| No | 7/9 77.8 (40.0, 97.2) |

|||||

| ACEI/ARB | No | 1002/1669 60.0 (57.6, 62.4) |

Yes | 90/476 18.9 (15.5, 22.7) |

Yes | 17/26 65.4 (44.3, 82.8) |

| No | 9/26 34.6 (17.2, 55.7) |

|||||

| No | 386/476 81.1 (77.3, 84.5) |

Yes | 29/140 20.7 (14.3, 28.4) |

|||

| No | 111/140 79.3 (71.6, 85.7) |

ACEI/ARB=Angiotensin converting enzyme inhibitor/angiotensin-II receptor blocker

n/N = number meeting criteria/number attending that visit

In the 38% women not on a statin after the first visit following CHD diagnosis, 40–45% were taking a statin at the next visit, and 84% continued use at the third visit (Table 2). Of the 26% of participants not on aspirin after the first visit following CHD diagnosis, 43–53% were taking aspirin by the next visit, and 88% continued use at a third visit. In the 42% of women who were not on a beta-blocker after the first visit following CHD diagnosis, 18–25% were taking a beta-blocker by the next visit, and 72% continued use at a third visit. In the 60% of women who were not on an ACE inhibitors or ARBs after the first visit following CHD diagnosis, 19–22% were on a drug in this class by the next visit and 65% continued use at a third visit.

Only 60% of women with incident CHD women were using a statin at 2 or more visits, with a slightly higher rate for aspirin (66%) and a slightly lower rate (48%) for beta-blockers (Table 3); 12% were using none of the 4 drug classes, 20% used just one drug class, 33% were using 2 drug classes, 27% were using 3 drug classes, and 8% were taking all 4 drug classes. Of women not on a statin at the first visit following CHD diagnosis, or who had discontinued the statin by the 2nd visit, only 23% initiated or resumed a statin at a subsequent visit. Similar low rates of initiation or resumption at a subsequent visit occurred for aspirin (17%), beta-blockers (15%) and ACE inhibitor/ARBs (17%). Looked at in another way, of women with incident CHD, fewer women reported never using a statin (20%) or aspirin (10%) than a beta-blocker (33%) or an ACE inhibitor or ARB (49%).

Table 3.

Continued use, later initiation or resumption of use, and never use of secondary prevention medications following adjudicated CHD diagnosis (mean percent with 95% confidence intervals)

| Drug class | % on med at 2 or more consecutive visits* | % initiating drug at 2nd or 3rd visit after CHD diagnosis or resumed med use after discontinuation | % who did not receive med at any visit following CHD diagnosis |

|---|---|---|---|

| Statin | 57.3 (53.7, 61.0) | 23.7 (20.7, 27.0) | 19.1 (16.3, 22.1) |

| Aspirin | 65.6 (62.0, 69.0) | 16.9 (14.2, 19.8) | 10.3 (8.2, 12.7) |

| Beta-blocker | 47.6 (43.9, 51.3) | 14.7 (12.2, 17.5) | 32.9 (29.5, 36.5) |

| ACE I/ARB | 28.4 (25.2, 31.8) | 17.0 (14.4, 19.9) | 49.4 (45.7, 53.1) |

ACEI/ARB=Angiotensin converting enzyme inhibitor/angiotensin-II receptor blocker

Of women with 2 or more visits following CHD diagnosis

Use of statins, aspirin, beta-blockers, and ACE/ARBs at each visit was almost identical in those with myocardial infarction as the first CHD event (n=1369) as in those with revascularization as the first CHD event (n=2118) [data not shown]. Use at 2 or more consecutive visits, respectively for myocardial infarction and revascularization first events, was 54% and 61% for statins, 65% and 67% for aspirin, 49% for both for beta-blockers, and 30% and 29% for ACE/ARBs. Later initiation or resumption, and never use, were also similar for the 2 types of first events.

Women with self-reported incident CHD (n=4537), were less likely to report use of a secondary prevention medication at the first visit following CHD diagnosis [45% (95% CI 44–47%) for statin, 60% (95% CI 58–61%%) for aspirin, 45% (95% CI 43–47%) for beta-blockers, and 34% (95% CI 32–36) for ACE/ARB. However, rates of persistent use (85–89% for statins, 80–81% for aspirin, 86–88% for beta-blockers, and 75–79% for ACE/ARBs) were similar to women with adjudicated CHD.

Discussion

Statins, aspirin, beta-blockers, ACE inhibitors, and ARBs use at the first WHI visit after CHD diagnosis increased markedly between 1993 and 2004. In this analysis of women who were pre-selected for adherence as a requirement for clinical trial participation, use at the first visit following CHD diagnosis had a major impact on long-term utilization. If a woman reported use at the first visit following CHD diagnosis, about 85% remained on a statin, aspirin, or a beta-blocker at a subsequent visits, and about 75% remained on an ACE/ARB. The second striking finding was the low rate of starting a medication after the first visit following CHD diagnosis, or restarting a medication class once it was discontinued–only 24% of those not previously on a statin started one during the period of follow-up, and about 16% for the other major prevention medication drug classes. Both findings underscore the importance that physician prescribing practices can play in maintaining long-term utilization of secondary prevention medication.

The rates of statin and aspirin use in our analysis of women with chronic CHD were higher than those reported at 30 days post-MI for large Medicare database during the same period. In this analysis of over 21,000 post-MI Medicare patients, 73% were women and the mean age was 80 years.2 By 2004, use of statins had increased to 51% (versus 72% in our analysis) and antiplatelet agents to 51% (versus 76% in our analysis). As would be expected in a purely post-MI population, the rate of beta-blocker use was higher at 72% (versus 62% in our analysis) as was ACE inhibitor/ARBs use 50% (versus 43% in our analysis). In a database of almost 100,000 patients from hospitals participating in the Get With The Guidelines-CAD hospital performance improvement program between 2000 and 2005, men were more 25% more likely to receive a statin at discharge than women.8 However, another analysis confined to Medicare patients aged ≥65 years, found no evidence of a gender difference in post MI use of statins, beta-blockers, and ACE inhibitors or ARBs.17

Suboptimal rates of secondary prevention medication use in WHI participants may include disparities in medication prescription at hospital discharge18–20 or medication discontinuation prior to the first WHI visit following CHD diagnosis, both of which have been reported to occur disproportionately in women with advancing age.7 Most drug discontinuations appear to occur within one month of hospital discharge with rates relatively stable over the remaining 1 year.7 These data further supports systematic efforts to increase rates of medication prescription at discharge, such as the American Heart Association’s Get With The Guidelines program. Our data suggest these efforts may result in higher rates of medication utilization long-term.

Continuous use of secondary prevention medications was disappointingly low in this cohort of health conscious older women thought generally to be adherent. Rates of continuous use at 2 consecutive visits of a statin (57%), aspirin (66%), or beta-blocker (48%) were suboptimal. Some women did, however, initiate or restart a drug at a later visit. This finding is consistent with an analysis of a Canadian insurance database in which 53% of new statin users had a period of nonadherence of at least 90 days, with 48% restarting treatment within 1 year and 60% by 2 years.21 Adverse hepatic or muscle events were reported in <1% of patients who discontinued statin therapy in the Canadian database. A 6-fold increase in restarting a statin was associated with visits to the physician who initiated statin treatment, a 3-fold increase was associated with visits to another physician, a 3.6-fold increase was associated with a cardiovascular disease hospitalization, and a 1.5-fold increase was associated with a cholesterol test. Other studies have found higher rates of statin and beta-blocker discontinuation over time. These studies were comprised predominantly of men, without data presented separately for women. The Duke Databank for Cardiovascular Disease (≥1 cardiac procedure with at least 2 follow-up surveys returned between 1995 and 2002; 70% male; and without CHF) found at the first follow-up survey in 2002 that the rate of aspirin use was 83%, lipid-lowering agents was 63%, beta-blockers was 61%, and all 3 drugs was 39%.22 Consistent use of aspirin over the next 2 annual surveys was reduced to 71%, beta-blockers to 46%, and lipid-lowering agents to 43%, while 21% reported consistent use of all 3 medications. Taken together, these findings suggest that interventions to improve continuous drug use by patients need to be accompanied by interventions to encourage physicians and patients to initiate or restart a secondary prevention medications after discontinuation. Routine cholesterol testing in patients with CHD along with routine medication inventories may be strategies for increasing continuous medication use.

Rates of ACE inhibitor and ARB use were lower than that of aspirin, statins, and beta-blockers, as might be expected given the more limited indications for use during this time period for hypertension, post-myocardial infarction patients with impaired left ventricular dysfunction or diabetic patients.23,24

Limitations of this study include that the WHI clinical trials were not a population-based sample. Women participating in the WHI clinical trials had several characteristics that may have enhanced long-term secondary prevention drug use. Not only were they more health conscious than average, they were also willing to regularly take hormone pills or adhere to a low fat diet in a long-term clinical trial. Nevertheless, one might expect that this greater health consciousness might have selected a sample of “ideal patients” in whom prescribing patterns might be expected to be better than average. As such, our findings are a cause for even greater concern. As discussed above, rates of persistence of drug use may differ in more typical populations, where factors such as competing demands for economic resources could play a bigger role.22,26

Although we cannot definitively separate lack of prescribing from patient adherence, our findings are highly suggestive that prescribing plays an important role, since once a women reported using a medication, she had at least an 80% probability of being on a drug in that class at the each subsequent visit. Support for this hypothesis also comes from the analysis of self-reported CHD. Although utilization of secondary prevention medications at the first visit following self-report of CHD was lower than for adjudicated CHD, utilization at subsequent visits was still about 80% or more. It should also be noted that the method of CHD documentation should therefore be considered when comparing studies of medication utilization.

By selecting a population of generally adherent individuals, we were able to provide additional support that physician prescribing behavior plays a major role not just in starting a secondary prevention medication but in continued long-term use. Future efforts to modify physician prescribing patterns should focus on re-prescribing discontinued drugs at later visits, in addition to initiating therapy following a CHD event. Effective interventions to enhance patient adherence are necessary as well. Such strategies are likely to have a substantial impact on long-term survival of women with CHD.

Conclusion

Healthcare providers should take the opportunity at every follow-up visit to encourage patients to continue secondary prevention medications, and to restart discontinued secondary prevention medications.

Acknowledgments

This project was also supported (or supported in part) by an Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ) Centers for Education and Research on Therapeutics cooperative agreement #5 U18 HSO16094.

List of abbreviations

- ACE/ARB

angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors/angiotensin-II receptor blockers

- CEE

conjugated equine estrogen

- CHD

coronary heart disease

- CI

confidence interval

- MI

myocardial infarction

- MPA

medroxyprogesterone acetate

- WHI

Women’s Health Initiative’s

Appendix

Program Office: (National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute, Bethesda, Maryland Barbara Alving, Jacques Rossouw, Linda Pottern.

Clinical Coordinating Center: (Fred Hutchinson Cancer Research Center, Seattle, WA) Ross Prentice, Garnet Anderson, Andrea LaCroix, Charles L. Kooperberg, Ruth E. Patterson, Anne McTiernan; (Wake Forest University School of Medicine, Winston-Salem, NC) Sally Shumaker; (Medical Research Labs, Highland Heights, KY) Evan Stein; (University of California at San Francisco, San Francisco, CA) Steven Cummings.

Clinical Centers: (Albert Einstein College of Medicine, Bronx, NY) Sylvia Wassertheil-Smoller; (Baylor College of Medicine, Houston, TX) Jennifer Hays; (Brigham and Women’s Hospital, Harvard Medical School, Boston, MA) JoAnn Manson; (Brown University, Providence, RI) Annlouise R. Assaf; (Emory University, Atlanta, GA) Lawrence Phillips; (Fred Hutchinson Cancer Research Center, Seattle, WA) Shirley Beresford; (George Washington University Medical Center, Washington, DC) Judith Hsia; (Harbor-UCLA Research and Education Institute, Torrance, CA) Rowan Chlebowski; (Kaiser Permanente Center for Health Research, Portland, OR) Evelyn Whitlock; (Kaiser Permanente Division of Research, Oakland, CA) Bette Caan; (Medical College of Wisconsin, Milwaukee, WI) Jane Morley Kotchen; (MedStar Research Institute/Howard University, Washington, DC) Barbara V. Howard; (Northwestern University, Chicago/Evanston, IL) Linda Van Horn; (Rush-Presbyterian St. Luke’s Medical Center, Chicago, IL) Henry Black; (Stanford Prevention Research Center, Stanford, CA) Marcia L. Stefanick; (State University of New York at Stony Brook, Stony Brook, NY) Dorothy Lane; (The Ohio State University, Columbus, OH) Rebecca Jackson; (University of Alabama at Birmingham, Birmingham, AL) Cora E. Lewis; (University of Arizona, Tucson/Phoenix, AZ) Tamsen Bassford; (University at Buffalo, Buffalo, NY) Jean Wactawski-Wende; (University of California at Davis, Sacramento, CA) John Robbins; (University of California at Irvine, Orange, CA) Allan Hubbell; (University of California at Los Angeles, Los Angeles, CA) Howard Judd; (University of California at San Diego, LaJolla/Chula Vista, CA) Robert D. Langer; (University of Cincinnati, Cincinnati, OH) Margery Gass; (University of Florida, Gainesville/Jacksonville, FL) Marian Limacher; (University of Hawaii, Honolulu, HI) David Curb; (University of Iowa, Iowa City/Davenport, IA) Robert Wallace; (University of Massachusetts/Fallon Clinic, Worcester, MA) Judith Ockene; (University of Medicine and Dentistry of New Jersey, Newark, NJ) Norman Lasser; (University of Miami, Miami, FL) Mary Jo O’Sullivan; (University of Minnesota, Minneapolis, MN) Karen Margolis; (University of Nevada, Reno, NV) Robert Brunner; (University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill, NC) Gerardo Heiss; (University of Pittsburgh, Pittsburgh, PA) Lewis Kuller; (University of Tennessee, Memphis, TN) Karen C. Johnson; (University of Texas Health Science Center, San Antonio, TX) Robert Brzyski; (University of Wisconsin, Madison, WI) Gloria E. Sarto; (Wake Forest University School of Medicine, Winston-Salem, NC) Denise Bonds; (Wayne State University School of Medicine/Hutzel Hospital, Detroit, MI) Susan Hendrix.

Footnotes

Disclosures

Jennifer G. Robinson, MD, MPH in the past year has received:

Grants: Abbott, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Hoffman La Roche, Merck, and Merck Schering-Plough

Consultant/Advisory Board: Astra-Zeneca, Wellmark

Robert Wallace, MD

Grants/research: NIH, Pfizer

Consultant: Merck and Co.

Clinical Trial Monitoring Board: Novartis

Monika Safford, MD

None.

Barbara Cochrane, PhD

None.

Mary Pettinger, MS

None.

Marcia G. Ko, MD

None.

M J O’Sullivan, MD

None.

Kamal Masaki, MD

Speaker’s bureau: Pfizer

Helen Peterovich, MD

None.

Clinical Trial Identifier: NCT00000611

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Contributor Information

Jennifer G Robinson, Email: jennifer-g-robinson@uiowa.edu, Departments of Epidemiology & Medicine, University of Iowa, Iowa City IA.

Robert Wallace, Email: robert-wallace@uiowa.edu, Departments of Epidemiology, University of Iowa, Iowa City IA.

Monika M. Safford, Email: msafford@uab.edu, Deep South Center on Effectiveness at the Birmingham VA Medical Center and the University of Alabama, Birmingham, AL.

Mary Pettinger, Email: mpetting@WHI.org, Fred Hutchinson Cancer Center, Seattle, WA.

Barbara Cochrane, Email: barbc@u.washington.edu, University of Washington, Seattle, WA.

Marcia G. Ko, Email: ko.marcia@mayo.edu, Division of Women’s Health, Mayo Clinic, Scottsdale, AZ.

Mary Jo O’Sullivan, Email: mosullivan@med.miami.edu, University of Miami, Miller School of Medicine, Miami FLA.

Kamal Masaki, Email: khmasaki@phrihawaii.org, Department of Geriatric Medicine, John A. Burns School of Medicine and School of Public Health, University of Hawaii, Manoa, HI.

Helen Petrovich, Email: hpetrovitch@phrihawaii.org, John A. Burns School of Medicine and School of Public Health, University of Hawaii, Manoa, HI.

References

- 1.Robinson JG, Maheshwari N. A “poly-portfolio” for secondary prevention: A strategy to reduce subsequent events by up to 97% over five years. Am J Cardiol. 2005;95:373–378. doi: 10.1016/j.amjcard.2004.09.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Setoguchi S, Glynn RJ, Avorn J, Mittleman MA, Levin R, Winkelmayer WC. Improvements in long-term mortality after myocardial infarction and increased use of cardiovascular drugs after discharge: A 10-year trend analysis. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2008;51:1247–1254. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2007.10.063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Smith JSC, Allen J, Blair SN, Bonow RO, Brass LM, Fonarow GC, Grundy SM, Hiratzka L, Jones D. AHA/ACC guidelines for secondary prevention for patients with coronary and other atherosclerotic vascular disease: 2006 update: Endorsed by the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2006;47:2130–2139. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2006.04.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Rasmussen JN, Chong A, Alter DA. Relationship between adherence to evidence-based pharmacotherapy and long-term mortality after acute myocardial infarction. JAMA. 2007;297:177–186. doi: 10.1001/jama.297.2.177. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. Effectiveness: Heart Disease. Rockville, MD: US Department of Health and Human Services; 2003. National Healthcare Quality Report; pp. 59–74. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Federman AD, Adams AS, Ross-Degnan D, Soumerai SB, Ayanian JZ. Supplemental insurance and use of effective cardiovascular drugs among elderly Medicare beneficiaries with coronary heart disease. JAMA. 2001;286:1732–1739. doi: 10.1001/jama.286.14.1732. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ho PM, Spertus JA, Masoudi FA, Reid KJ, Peterson ED, Magid DJ, Krumholz HM, Rumsfeld JS. Impact of medication therapy discontinuation on mortality after myocardial infarction. Arch Intern Med. 2006;166:1842–1847. doi: 10.1001/archinte.166.17.1842. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Albert NM, Birtcher KK, Cannon CP, Goff DC, Jr, Mulgund J, Liang L, Fonarow GC. Factors associated with discharge lipid-lowering drug prescription in patients hospitalized for coronary artery disease (from the Get With the Guidelines Database) Am J Cardiol. 2008;101:1242–1246. doi: 10.1016/j.amjcard.2007.12.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Stefanick ML, Cochrane BB, Hsia J, Barad DH, Liu JH, Johnson SR. The Women’s Health Initiative postmenopausal hormone trials: overview and baseline characteristics of participants. Ann Epidemiol. 2003;13:S78–S86. doi: 10.1016/s1047-2797(03)00045-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ritenbaugh C, Patterson RE, Chlebowski RT, Caan B, Fels-Tinker L, Howard B, Ockene J. The Women’s Health Initiative Dietary Modification Trial: Overview and baseline characteristics of participants. Ann Epidemiol. 2003;13:S87–S97. doi: 10.1016/s1047-2797(03)00044-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.The Women’s Health Initiative Study Group. Design of the Women’s Health Initiative clinical trials and observational study. Control Clin Trials. 1998;19:61–109. doi: 10.1016/s0197-2456(97)00078-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Writing Group for the Women’s Health Initiative Investigators. Risks and benefits of estrogen plus progestin in healthy postmenopausal women: Principal results from the Women’s Health Initiative randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2002;288:321–333. doi: 10.1001/jama.288.3.321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hsia J, Langer RD, Manson JE, Kuller L, Johnson KC, Hendrix SL, Pettinger M, Heckbert SR, Greep N, Crawford S, Eaton CB, Kostis JB, Caralis P, Prentice R for the Women’s Health Initiative Investigators. Conjugated equine estrogens and coronary heart disease: The Women’s Health Initiative. Arch Intern Med. 2006;166:357–365. doi: 10.1001/archinte.166.3.357. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Howard BV, Van Horn L, Hsia J, Manson JE, Stefanick ML, Wassertheil-Smoller S, Kuller LH, LaCroix AZ, Langer RD, Lasser NL, Lewis CE, Limacher MC, Margolis KL, Mysiw WJ, Ockene JK, Parker LM, Perri MG, Phillips L, Prentice RL, Robbins J, Rossouw JE, Sarto GE, Schatz IJ, Snetselaar LG, Stevens VJ, Tinker LF, Trevisan M, Vitolins MZ, Anderson GL, Assaf AR, Bassford T, Beresford SAA, Black HR, Brunner RL, Brzyski RG, Caan B, Chlebowski RT, Gass M, Granek I, Greenland P, Hays J, Heber D, Heiss G, Hendrix SL, Hubbell FA, Johnson KC, Kotchen JM. Low-fat dietary pattern and risk of cardiovascular disease: The Women’s Health Initiative randomized controlled dietary modification trial. JAMA. 2006;295:655–666. doi: 10.1001/jama.295.6.655. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Curb JD, Mctiernan A, Heckbert SR, Kooperberg C, Stanford J, Nevitt M, Johnson KC, Proulx-Burns L, Pastore L, Criqui M, Daugherty S. Outcomes ascertainment and adjudication methods in the Women’s Health Initiative. Ann Epidemiol. 2003;13:S122–S128. doi: 10.1016/s1047-2797(03)00048-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.SAS version 9.1. Cary, NC: SAS Institute, Inc; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Setoguchi S, Solomon DH, Levin R, Winkelmayer WC. Gender differences in the management and prognosis of myocardial infarction among patients >= 65 years of age. Am J Cardiol. 2008;101:1531–1536. doi: 10.1016/j.amjcard.2008.02.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Jani SM, Montoye C, Mehta R, Riba AL, DeFranco AC, Parrish R, Skorcz S, Baker PL, Faul J, Chen B, Roychoudhury C, Elma MAC, Mitchell KR, Eagle KA for the American College of Cardiology Foundation Guidelines Applied in Practice Steering Committee. Sex differences in the application of evidence-based therapies for the treatment of acute myocardial infarction: The American College of Cardiology’s Guidelines Applied in Practice Projects in Michigan. Arch Intern Med. 2006;166:1164–1170. doi: 10.1001/archinte.166.11.1164. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Spencer FA, Lessard D, Yarzebski J, Gore JM, Goldberg RJ. Decade-long changes in the use of combination evidence-based medical therapy at discharge for patients surviving acute myocardial infarction. Am Heart J. 2005;150:838–844. doi: 10.1016/j.ahj.2004.11.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Vaccarino V, Rathore SS, Wenger NK, Frederick PD, Abramson JL, Barron HV, Manhapra A, Mallik S, Krumholz HM the National Registry of Myocardial Infarction I. Sex and racial differences in the management of acute myocardial infarction, 1994 through 2002. N Engl J Med. 2005;353:671–682. doi: 10.1056/NEJMsa032214. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Brookhart MA, Patrick AR, Schneeweiss S, Avorn J, Dormuth C, Shrank W, van Wijk BLG, Cadarette SM, Canning CF, Solomon DH. Physician follow-up and provider continuity are associated with long-term medication adherence: A study of the dynamics of statin use. Arch Intern Med. 2007;167:847–852. doi: 10.1001/archinte.167.8.847. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Newby LK, Allen LaPointe NM, Chen AY, Kramer JM, Hammill BG, DeLong ER, Muhlbaier LH, Califf RM. Long-term adherence to evidence-based secondary prevention therapies in coronary artery disease. Circulation. 2006;113:203–212. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.105.505636. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Smith SC, Jr, Blair SN, Bonow RO, Brass LM, Cerqueira MD, Dracup K, Fuster V, Gotto A, Grundy SM, Miller NH, Jacobs A, Jones D, Krauss RM, Mosca L, Ockene I, Pasternak RC, Pearson T, Pfeffer MA, Starke RD, Taubert KA. AHA/ACC guidelines for preventing heart attack and death in patients with atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease: 2001 update: A statement for healthcare professionals from the American Heart Association and the American College of Cardiology. Circulation. 2001;104:1577–1579. doi: 10.1161/hc3801.097475. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Smith SC, Jr, Allen J, Blair SN, Bonow RO, Brass LM, Fonarow GC, Grundy SM, Hiratzka L, Jones D, Krumholz HM, Mosca L, Pasternak RC, Pearson T, Pfeffer MA, Taubert KA. AHA/ACC guidelines for secondary prevention for patients with coronary and other atherosclerotic vascular disease: 2006 update: Endorsed by the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute. Circulation. 2006;113:2363–2372. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.106.174516. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Pahor M, Psaty BM, Alderman M, Applegate W, Williamson J, Cavazzini C, Furberg C. Health outcomes associated with calcium channel antagonists compared with other first-line antihypertensive therapies: a meta-analysis of randomised controlled trials. Lancet. 2000;356:1949–1954. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(00)03306-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Soumerai SB, Pierre-Jacques M, Zhang F, Ross-Degnan D, Adams AS, Gurwitz J, Adler G, Safran DG. Cost-related medication nonadherence among elderly and disabled Medicare beneficiaries: A national survey 1 year before the Medicare Drug Benefit. Arch Intern Med. 2006;166:1829–1835. doi: 10.1001/archinte.166.17.1829. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]