Abstract

Human embryonic stem (hES) cells are pluripotent, capable of differentiating into any cell type of the body, and therefore have the ability to provide insights into mechanisms of human development and disease, as well as to provide a potentially unlimited supply of cells for cell-based therapy and diagnostics. Knowledge of the adhesion receptors that hES cells employ to engage extracellular matrix (ECM) proteins is of basic biological interest and can enhance the design of cell culture and implantation systems to enable these biomedical applications. Although hES cells express a variety of cell surface receptors, little is known about which integrins are involved during subculture and passage. Matrigel is broadly used as a cell adhesive matrix for hES cell culture. Here, we sought to identify which integrins hES cells exploit for adhesion to Matrigel-coated surfaces in defined medium conditions. Using RT-PCR, flow cytometry, and fluorescence immunochemistry, we found that numerous integrins were expressed by H1 hES cells; however, antibody blocking assays indicated that only αvβ3, α6, β1, and α2β1 played a significant role in the initial adhesion of the hES cells to Matrigel in defined medium conditions. We subsequently identified a cohort of synthetic peptides that, when adsorbed to the culture surface, promoted H1 hES cell attachment and proliferation, as well as maintained a pluripotent phenotype. Peptides designed to engage with αvβ3, α6, β1, and α2β1 integrins and syndecan-1 were tested both individually and in various combinations. A combination of two integrin-engaging peptides (AG-10, C-16) and one syndecan-engaging peptide (AG-73) was sufficient to promote hES cell adhesion, maintenance, and proliferation. We propose that a specific integrin “fingerprint” is necessary for maintenance of hES cell self-renewal, and synthetic culture systems must capture this engagement profile for hES cells to remain undifferentiated.—Meng, Y., Eshghi, S., Li, Y. J., Schmidt, R., Schaffer, D. V., Healy, K. E. Characterization of integrin engagement during defined human embryonic stem cell culture.

Keywords: extracellular matrix, Matrigel, peptide, microenvironment, biointerface, cell adhesion, feeder-free cell culture

Human embryonic stem (hES) cells are distinguished by their capacity for self-renewal and pluripotent differentiation into cells comprising the three germ layers, and subsequently, any cell type in the adult body (1, 2). These cells have accordingly generated a great deal of excitement as a universal source for cell-based therapeutics and diagnostics. The successful integration of hES cells into clinical therapies will hinge on four critical steps: stem cell expansion in number without differentiation (i.e., self-renewal); directed differentiation into a specific cell type or collection of cell types; cell survival post-transplantation; and functional integration into existing tissue. Precisely controlling each of these steps is essential to maximize hES cell therapeutic efficacy, as well as to minimize potential side effects that can occur when cell numbers and phenotypes are not properly controlled.

Currently, it is difficult to precisely control the behavior of hES cells, since microenvironmental conditions that regulate self-renewal and differentiation are incompletely understood. Typically, hES cells are grown on mouse embryonic fibroblasts (MEFs) with soluble factors, such as basic fibroblast growth factor (bFGF or FGF-2), added to the medium (1). However, batch-to-batch variability in MEFs, xenogeneic contaminants, and expression of foreign oligosaccharide residues acquired from mouse feeder cells and culture medium have limited their clinical potential (3). Newer hES cell lines have been derived on human feeder layers, but this system also suffers from similar reproducibility issues and has limits for large-scale hES cell expansion (4,5,6). Progress in identifying soluble factors that feeder cells contribute to hES cell culture medium has improved the development of feeder-free culture systems; however, a completely synthetic system (i.e., both medium and substrata) has not been identified (reviewed in ref. 7) (8,9,10,11,12,13,14,15,16).

All current feeder-free hES cell culture systems employ animal or human-derived extracellular matrix (ECM) proteins to coat the culture substrata and have supported growth in the undifferentiated state (8,9,10,11,12,13,14,15,16). Compared to the cell-based feeder systems, ECM proteins offer several advantages, including reduced risk of pathogen transmission and relative ease of scale-up. The most exploited of these ECM analogues is Matrigel™, an extraction from Engelbreth–Holm–Swarm (EHS) mouse sarcomas, which contains not only basement membrane components (laminin, collagen IV, heparin sulfate proteoglycans, and entactin), but also matrix-degrading enzymes, their inhibitors, numerous growth factors, and a broad variety of other proteins, as recent proteomic data indicate (17, 18). This diversity of ECM molecules and other biologically active factors highlights a number of scale-up challenges, including obtaining large quantities of consistently high-quality Matrigel, developing analogous blends of high-quality human ECM proteins, and potential complications for regulatory approval.

hES cell derivation, maintenance, and differentiation within a completely synthetic environment would offer numerous advantages. In particular, it will be possible to eliminate pathogen transmission associated with mouse or human feeder layers, provide a scalable basis for large-scale production of hES cells, and provide an important system for elucidating the regulation of and ultimately precisely controlling hES cell behavior. It is widely recognized that the microenvironment in which hES cells reside regulates their fate; however, replacing the complex ECM components that feeder cells likely provide with a synthetic matrix has proven challenging (7).

In an attempt to define a substitute for Matrigel for nonconditioned serum-free medium (NC-SFM) hES cell culture systems, we examined the role integrins play in the initial adhesion of hES cells to Matrigel. We targeted these widely conserved cell surface receptors because they are critical regulators of cell adhesion to the ECM and can regulate cell migration, survival, differentiation, and development (19, 20). Recently, integrin signaling has been demonstrated to be a critical regulator of self-renewal of mouse ES cells, a vital component of the developing stem cell niche in Drosophila during gonad morphogenesis, and a participant in the function of the pluripotent inner cell mass from which hES cells are derived (21,22,23). Integrins exist as heterodimers consisting of individual α and β subunits that can be primarily classified into three major groups defined by the β1, β2, and αv subunits. The β1 subunit can form heterodimers with at least 12 distinct α chains, and this group is present on cells derived from all tissue types of the three germ layers and is essential for development of the inner cell mass (24, 25). The β2 integrin functions primarily in immune cells, and αv is the only α chain that can dimerize with several integrin β chains. In addition, all of the αv-containing integrin heterodimers recognize the triple amino acid sequence arginine-glycine-aspartic acid (RGD) as their primary ligand. Furthermore, different α- and β-chain combinations impart distinct ligand-binding capabilities to integrin complexes; some αβ heterodimers bind to single ligands, whereas others bind to several ligands. These myriad combinations create a unique set of signaling complexes that are expressed in spatially discrete patterns during development (20).

Related to our work, integrin-matrix engagement is essential to cell adhesion and has been shown to promote cell survival under conditions of stress or chemically induced apoptosis (26). A unique function of integrin receptors is their bidirectional signaling (i.e., outside-in and inside-out), which makes them sophisticated transducers of physical and chemical stimuli communicated via the ECM (20). Integrin activation can be controlled by the mode of presentation of the ligand, such that a ligand presented from the solid state can function as an agonist, whereas the same ligand can act as an antagonist when presented in a soluble form (27, 28). Furthermore, the lack of integrin engagement by adherent cells leads to caspase-induced apoptosis, suggesting hES culture systems that do not have “proper” integrin engagement will not propagate in culture (29). In concert with this observation, we propose that synthetic culture systems require engagement of a panel of specific integrins to maintain the undifferentiated state.

We characterized the integrin expression of hES cells when cultured on Matrigel-coated substrates in NC-SFM using RT-PCR, flow cytometry, and fluorescence immunocytochemistry, and found that a wide array of integrin receptors were expressed. In addition, using antibody antagonists of integrin function, we determined that a smaller set of integrins—αvβ3, α6, β1, and α2β1—played a significant role in the initial adhesion of the hES cells to Matrigel-coated surfaces in defined medium conditions. These data were critical in designing synthetic peptide agonists that recapitulate the integrin engagement repertoire found on the Matrigel-coated surfaces. Specifically, we subsequently discovered a cohort of synthetic peptides that, when adsorbed to the culture surface, promote hES cell attachment, proliferation, and maintenance of a pluripotent phenotype.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Preparation of cell culture medium and cell adhesion substrates

H1 hES cells (1) were kindly provided by Geron Corp. (Menlo Park, CA, USA). Throughout this work, benchmark cell culture conditions consisted of culturing hES cells on surfaces coated with a 1:30 dilution of Matrigel (growth factor reduced; Becton Dickinson, Bedford, MA, USA) in an NC-SFM system, which consisted of X-Vivo 10 medium (Cambrex, Walkersville, MD, USA) supplemented with 80 ng/ml basic fibroblast growth factor (FGF-2; R&D Systems, Minneapolis MN, USA) and 0.5 ng/ml transforming growth factor-β1 (TGF-β1; R&D Systems). This medium has previously been found to support hES cell self-renewal over extended periods of time (9). Matrigel was thawed at 4°C overnight and diluted 1:30 in serum-free cold knockout Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s medium (KO-DMEM; Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA, USA), and 1 ml/well was added to a 6-well cell culture plate. On the day of subculture, the plates were warmed to 25°C, and the Matrigel was aspirated. hES cells were treated with collagenase IV (crude 200 U/ml; Invitrogen) for 5–10 min and washed twice with Dulbecco’s phosphate-buffered saline (DPBS). Cells were scraped to remove adherent cells and to gently dissociate the colonies. Cells were then diluted to a seeding density of 105 cells/cm2 for a 6-well plate, cultured at 37°C and 5% CO2, and left undisturbed for 48 h, after which the medium was changed daily.

Peptide-coated substrata were created in the following manner. All peptides used in this study were custom synthesized by American Peptide (Sunnyvale, CA, USA). For peptide adsorption to the culture surface, each peptide was dissolved to a final concentration in 1 mg/ml, typically in water, and was diluted to 0 to 30 nmol/cm2 for concentration-dependent studies. All water used in this study was ultrapure American Society for Testing and Materials (ASTM) type I reagent-grade water (18.2 MΩ·cm, pyrogen free, endotoxin <0.03 EU/m). A total volume of 200 μl was added to each well of a 24-well polystyrene culture plate and adsorbed overnight at 4°C. The remaining solution was aspirated, and the plates were washed 3 times with PBS prior to use. The following peptides sequences were tested: AG-10 (CGGNRWHSIYITRFG) and AG-32 (CGGTWYKIAFQRNRK) to engage with the α6β1 integrin (30, 31), C-16 (CGGKAFDITYVRLKF) to engage with αVβ3 and α5β1 integrins (32), and AG-73 (CGGRKRLQVQLSIRT) to purportedly engage with syndecan-1 (CD138) (30, 31, 33). Water was used to dissolve AG-10 and AG-73 peptides, and a solvent of 10% acetonitrile in water was used for C-16.

RNA isolation and RT-PCR

H1 hES cells were maintained under feeder-free conditions as described elsewhere (9). The procedure for total RNA isolation with TRIzol reagent was adopted from the manufacturer’s directions (Invitrogen). Briefly, H1 hES cells were incubated with 1 ml of TRIzol reagent at room temperature to allow complete dissociation. After transfer of the lysate to an RNase-free tube, 0.2 ml of chloroform was added to induce phase separation, and tubes were shaken vigorously and incubated at 15–30°C. After centrifugation, the colorless upper aqueous phase was transferred to a fresh RNase-free tube for isopropyl alcohol addition, incubation, and centrifugation to precipitate and pellet the RNA. The resulting pellet was washed with 75% ethanol, centrifuged, and dissolved in 10–20 μl of RNase-free water.

RT-PCR analysis was then employed to identify integrin mRNA expression by H1 hES cells. To obtain cDNA, RT was conducted using a Thermoscript II kit (Invitrogen), following the manufacturer’s instructions. The forward and reverse oligonucleotide primers chosen to amplify specific cDNAs by PCR are listed in Supplemental Table S1. PCR was performed using a Bio-Rad iCycler in a 20-μl reaction mixture containing 0.5 μl cDNA, 2 μl 10× DNA polymerase reaction buffer, 10 mM dNTP, 10 μM of each forward and reverse primer, and 1.0 U of Taq polymerase (New England Biolabs, Ipswich MA, USA) under the following reaction conditions: denaturation at 95°C (30 s), annealing at 50–65°C (50 s), and extension at 72°C (1 min) for 30–35 cycles, followed by a final extension at 72°C (10 min) to ensure complete product extension. Products were identified by electrophoresis using a 2.5% agarose gel.

Flow cytometry

H1 hES cells at passage 54 were plated at 105 cells/cm2 (6-well plate). On d 4, cells were prepared into a single-cell suspension by treatment with collagenase IV for 10 min. Cells were then washed with DPBS (without Ca2+, Mg2+) and incubated with 0.02% EDTA (Sigma, St. Louis, MO, USA) for 20 min. Cells were further dissociated by gentle pipetting and passed through a cell strainer (40 μm; Falcon, Franklin Lakes, NJ, USA). The EDTA was quenched with DMEM (Invitrogen) + 10% FBS (Hyclone, Logan, UT, USA) and centrifuged. Then cells were resuspended to 107 cells/ml in staining buffer, which consisted of DPBS (Ca2+, Mg2+) + 2% knockout serum replacement (KSR) (Life Technologies, Rockville, MD, USA). Primary antibodies were diluted to 2× in staining buffer, and 50 μl was added to microfuge tube, followed by the addition of 50 μl of cells (0.5×106 cells). Primary antibodies were incubated for 30 min at 4°C. Cells were then washed with 1 ml of DPBS and centrifuged. The blocking step consisted of incubation with blocking buffer DPBS (Ca2+, Mg2+) + 5% FBS for 10–15 min at 4°C. Cells were then washed, centrifuged, incubated with secondary antibodies for 30 min at 4°C in the dark, and subsequently washed and resuspended in 150 μl staining buffer. Propidium iodide (PI) solution (150 μl at 1:500 dilution; Sigma) was added immediately prior to flow cytometry to enable the exclusion of nonviable cells from the data analysis. In this experiment, primary antibodies and isotypes had final a dilution (1×) of 1:50; with the exception of α6, which was diluted 1:25, according to manufacturer’s instructions. Secondary antibodies were diluted 1:100 (see Supplemental Table S2 for antibody source).

Flow cytometry was conducted at the University of California at Berkeley Flow Cytometry Center using a Beckman-Coulter EPICS XL flow cytometer, with an argon ion air-cooled laser (emission at 488 nm/15 mW power), 5 photomultiplier tube detectors for 90° light scatter (90LS) and 4-color detection, and 1 diode detector for forward light scatter (FLS). In this experiment, the fluorescent channel 1 (FL1/FITC) was used to detect the FITC-conjugated integrins, and fluorescent channel 2 (FL2/PI) was used to analyze PI to enable discrimination of live/dead cells.

Immunofluorescence

Expression of the pluripotent hES cell markers Oct4, SSEA-4, and Tra-1–60—as well as that of the integrins α6, β1, α2β1, and αvβ3—was characterized by indirect immunofluorescence. H1 hES cells were cultured, as described above for 7 d, fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde (EMS, Hatfield, PA, USA) for 30 min at room temperature, rinsed with PBS three times for 5 min each, permeabilized with 0.1% Triton X-100 (Fisher Scientific, Fair Lawn, NJ, USA) in PBS for 15 min at room temperature, and rinsed with PBS. Samples were blocked in blocking buffer (5% goat serum and 0.1% Triton X-100 in PBS) for 1 h, then exposed to primary antibody at 4°C overnight. After 3 rinses with PBS, samples were treated with a fluorescein-conjugated secondary antibody for 1 h at room temperature in the dark. After removing the secondary antibody, the samples were rinsed, nuclei were stained with diaminophenylindole (DAPI; Vector Laboratories, Burlingame, CA, USA), and cells were visualized using a Nikon Eclipse TE300 Inverted Microscope (Nikon Instruments, Melville, NY, USA).

For Oct4 immunofluorescence, goat polyclonal antibody (1:50 dilution; Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Santa Cruz, CA, USA) was used as the primary antibody and Alex Fluor 488 donkey anti-goat IgG (1:500; Invitrogen) as the secondary antibody. Mouse anti-Tra-1–60 (1:50; Chemicon International, Temecula CA) and Cy3 conjugated anti-mouse IgM (1:100; Invitrogen) were used as the primary and secondary antibodies, respectively, for Tra-1–60 immunostaining. For SSEA-4 immunofluorescence, mouse monoclonal antibody (1:50; Millipore, Billerica, M, USA) was used as the primary antibody and Alexa Fluor 488 donkey anti-mouse (1:500) as the secondary antibody. For identification of integrins present on H1 hES cells cultured on Matrigel, rat anti-α6, mouse anti-β1, anti-α2β1, and anti-αvβ3 monoclonal antibodies from Chemicon Internationalwere used as primary antibodies for their respective integrins. Alexa Fluor 488 goat anti-rat IgG conjugate and Alexa Fluor 488 goat anti-mouse IgG conjugate were used as secondary antibodies. Antibody specificity was verified by an isotype control.

Cell adhesion and inhibition assays

To identify specific integrin contributions to initial H1 hES cells adhesion, a cell adhesion assay was performed using 24-well polystyrene plates (Falcon) coated with either Matrigel or synthetic peptides. Matrigel coating and peptide adsorption were as described above. Cell adhesion was assayed according to methodology described previously (34). Briefly, coated wells were washed with PBS and incubated with 2 mg/ml heat-inactivated BSA for 60 min to block remaining protein binding sites on the surface. H1 hES cells were harvested by exposure to 0.05% trypsin-EDTA (Invitrogen) for 1–2 min, immediately followed by inhibition medium (10% KSR and KO-DMEM) to terminate trypsin activity, and cells were then physically scraped off the culture surface. The collected hES cells were centrifuged at 1000 rpm for 5 min, washed with PBS, and then suspended in X–VIVO medium. Cells (200 μl/well, 2.5×105 cells/ml) were then seeded onto culture plates and incubated for 1 h at 37°C and 5% CO2 for Matrigel-coated plates, and 3 h for the peptide-coated plates. After the specified time period, wells were rinsed with PBS to remove unattached cells, and the number of attached cells was quantified using the CyQuant assay (Invitrogen). For the integrin antibody blocking assay, cells were preincubated with 10 μg/ml of integrin-specific blocking antibodies (Supplemental Table S2) at 37°C for 30 min. The control group consisted of mock-treated cells.

Embryoid body (EB) formation

H1 hES cells were grown on peptide-coated plates as described above for 5 d and subsequently passaged and plated on fresh peptide-coated plates for another 5 d. The ROCK inhibitor Y-27632 (Calbiochem, La Jolla, CA, USA) was added to the culture medium for the first 2 d after passage at 10 μM to enhance cell survival. On d 5 of the second passage, hES colonies were released with collagenase IV and cultured in X-VIVO medium without growth factors on uncoated bacterial polystyrene plates. Medium was replaced daily. After 4 d of differentiation (35), EBs were harvested in TRIzol, and mRNA isolation and PCR was conducted as described above.

Statistical analysis

All statistical analysis was carried out using ANOVA with a Tukey HSD post hoc test, and results were considered significant at P < 0.05.

RESULTS

Analysis of integrin expression and engagement on hES cells

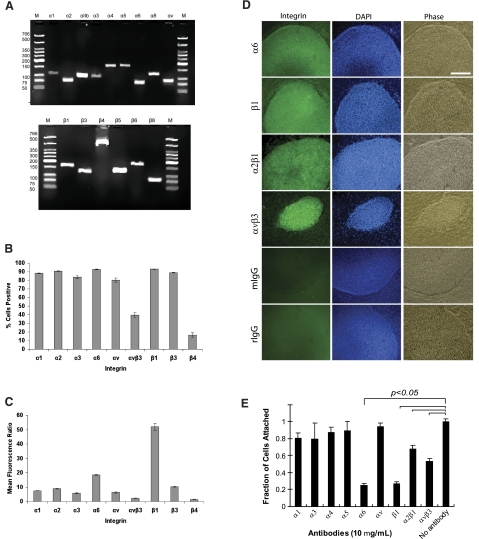

We used RT-PCR, flow cytometry, and fluorescence immunocytochemistry combined with confocal microscopy to analyze the expression of integrin subunits on hES cells (H1 line). The RT-PCR results showed that H1 hES cells expressed mRNA for the integrin subunits α1, α2, αIIb, α3, α4, α5, α6, αV, β1, β3, β4, and β6 (Fig. 1A). Flow cytometry was then used to quantitate integrin protein expression in two ways. First, the percentage of cells expressing each integrin subunit was determined by comparing expression of each integrin to an isotype control. Cells were defined as positive if their fluorescence level was above 95% of the isotype control cells. H1 cells expressed a broad range of integrins: >90% of cells expressed β1 (Supplemental Fig. S1), α6, and α2; >80% of cells expressed β3, α1, α3, and αv; 40% of cells were αvβ3 positive; and <25% of cells expressed the β4 subunit (Fig. 1B). Second, the mean fluorescence ratio was calculated as the quotient of the means of the full distributions for integrin and isotype control samples. Using this metric, we found that the β1 subunit had the highest mean ± sd fluorescence ratio at 52 ± 2, with α6, β3, and α2 having the next highest ratios at 9–16 (Fig. 1C). The remaining integrin subunits had ratios of <9. We then used immunofluorescence to verify integrin expression in situ. H1 hES cells stained positively for the α6, β1, α2β1, and αvβ3 integrins (Fig. 1D).

Figure 1.

Integrin expression and usage of hES cells on Matrigel-coated substrata. A) RT-PCR analysis of integrins expression of H1 ES cells cultured on Matrigel-coated substrata. Top panel: size of individual bands for α integrins: α1 (117 bp); α2 (82 bp); αIIb (104 bp); α3 (103 bp); α4 (168 bp); α5 (171 bp); α6 (81 bp); α8 (110 bp); and αv (84 bp). Bottom panel: size of individual bands for β-integrins: β1 (168 bp); β3 (126 bp); β4 (521 bp); β5 (135 bp); β6 (181 bp); and β8 (84 bp). M, low-molecular-weight DNA ladder. B) Flow cytometry of integrin expression on hES cell surface, demonstrating a broad panel of integrin expression. Percentage of cells positive = percentage positive in sample − percentage positive in isotype control. Error bars = sd (n=3). C) Mean fluorescence ratio of integrin expression on H1 cell surface, where the β1 integrin yielded the highest value. Mean fluorescence ratios were calculated as the quotient of the mean of the region for the integrin and the mean for its isotype control. Error bars = sd (n=3). D) Integrin expression of ES cells cultured on Matrigel-coated surfaces. Immunofluorescence for selected integrins expressed by hES cell cultures on d 7. The α6, β1, α2β1, and αvβ3 integrins were strongly expressed (green); corresponding DAPI staining (blue) and phase contrast images are shown. Mouse and rat IgG were used as negative controls. Scale bar = 500 μm. E) Antibody blocking assay for hES cell attachment to Matrigel-coated substrata. Before seeding, cells were preincubated with various integrin antibodies for 30 min at 37°C. Attachment of cells was significantly inhibited by α6, β1, α2β1, and αvβ3 antibody antagonists. (P<0.05; ANOVA). Cells that were not preincubated with an antibody were used as controls.

Collectively, these results demonstrate that hES cells express a broad range of integrin subunits; however, it was unclear which were functionally used to engage the culture substrate. We therefore investigated which integrins were exploited by hES cells for adhesion to Matrigel-coated substrata under defined culture conditions using an adhesion assay with integrin-blocking antibodies. The results revealed that function-blocking antibodies directed to the α6, β1, α2β1, and αvβ3 integrins resulted in statistically significant reductions in initial cell attachment (Fig. 1E, P<0.05; ANOVA with Tukey HSD), whereas blocking antibodies directed against α1, α3, α4, α5, and αv integrin subunits had little effect. Thus, we developed synthetic substrates that mimicked the integrin engagement profile of Matrigel by focusing ligands that bind to α6, β1, α2β1, and αvβ3 integrins.

Analysis of hES cell adhesion to synthetic peptides

Three synthetic cell adhesion peptides were developed on the basis of integrin-engaging cell adhesion motifs of laminin-111, which is the major ECM component of Matrigel (18, 36). Specifically, AG-10 peptide was chosen to engage with α6β1, C-16 was designed to engage αVβ3 integrins, and AG-73 was utilized to bind with cell surface heparan sulfates. Cell adhesion to each peptide was quantified by varying the input peptide concentrations from 0 to 60 nmol/well, adsorbing peptides on the culture surfaces, and incubating hES cells on these surfaces followed by rinsing. At peptide concentrations >10 nmol/well, AG-10, C-16, and AG-73 mediated significant cell attachment, such that the percentages of cells that bound were 37.8 ± 2.9, 54.1 ± 2.4, and 60.9 ± 1.1%, respectively (Supplemental Fig. S1). The control group of H1 hES cells binding on Matrigel was 69 ± 6.2% (Supplemental Fig. S1).

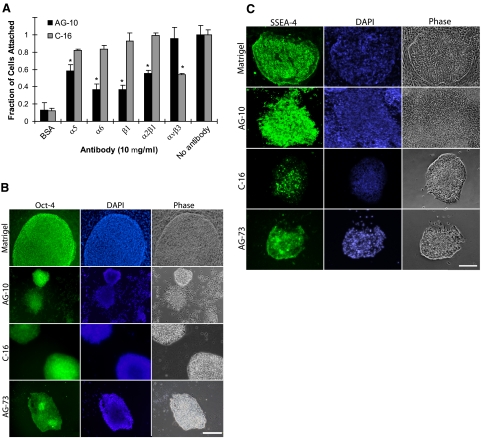

To validate the integrin-engagement profile of each synthetic peptide, the cell adhesion assay was repeated with function-blocking antibodies to integrin subunits as described above. H1 cell adhesion to AG-10 peptide was significantly inhibited by anti-α5, α6, β1, and α2β1 monoclonal antibodies, while only the anti-αvβ3 antibody blocked cell binding to C-16 (Fig. 2A). Since AG-73 engages heparan sulfate side chains of syndecan-1 on cells rather than integrins for cell adhesion (33, 37), its binding ability was not analyzed with integrin-blocking antibodies.

Figure 2.

Synthetic peptides support ES cell adhesion. A) Antibody-blocking assay for hES cell attachment to AG-10 and C-16 peptide-coated surfaces. Before seeding, cells were preincubated with various integrin antibodies for 30 min at 37°C. Attachment of cells on AG-10 was significantly inhibited by α5, α6, β1, and α2β1 antibody antagonists, whereas hES cell adhesion to C-16 was blocked by αvβ3. Cells that were not preincubated with an antibody were used as controls. *P < 0.05; ANOVA. B) Images of Oct4 expression of hES cells on Matrigel-coated, AG-10 peptide-coated, C-16 peptide-coated, and AG-73 peptide-coated substrata. Positive colonies stained green (left panels); nuclei were stained blue by DAPI (center panels); corresponding phase-contrast images are shown (right panels). C) Images of SSEA-4 expression of hES cells on Matrigel-coated, AG-10 peptide-coated, C-16 peptide-coated, and AG-73 peptide-coated substrata. Positive colonies stained green (left panels); nuclei were stained blue by DAPI (center panels); corresponding phase-contrast images are shown (right panels). Scale bars = 500 μm.

Maintenance of self-renewal on the peptide-coated surfaces was assessed by Oct4 and SSEA-4 immunofluorescence (Fig. 2B, C). All of the synthetic peptides tested supported maintenance of Oct4 and SSEA-4 expression at 4 d. However, we observed that these single-peptide interfaces had either low adhesion (Supplemental Fig. S2), a smaller surface area covered by the colonies, fewer colonies, or reduced number of Oct4+ colonies relative to Matrigel-coated surfaces (Supplemental Table S3). Furthermore, we observed some deterioration in colony morphology at later passages, presumably since these surfaces did not support the outgrowth of noncolony stromal cells in a similar fashion as Matrigel-coated surfaces. Although these results suggest that each peptide can mediate initial hES cell attachment and self-renewal, a single peptide interface was not sufficient to maintain hES cell pluripotency in SF-NCM for extended periods of time.

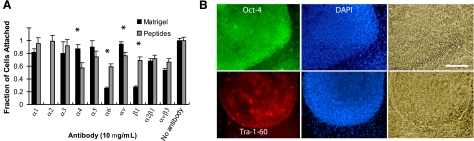

We next explored whether a combination of individual peptides could mimic the multiple adhesion ligands presented by Matrigel and thus better support hES adhesion and maintenance. Various molar ratios of peptides were investigated while maintaining a constant total peptide concentration of 15 nmol/well in a 24-well plate (data not shown). A combination of 60:16:24% (molar ratio of AG-10:C-16:AG-73) was found to support hES cell adhesion at a level similar to that of Matrigel (Fig. 3A and Supplemental Table S3). Using function-blocking antibodies, we found the triple-peptide combination to most accurately mimic the integrin engagement profile of Matrigel (Fig. 3A). H1 hES cell adhesion to triple peptide-coated substrata was functionally inhibited by anti-α4, -α5, -α6, -αv, -β1, -α2β1, and -αvβ3 antibody antagonists (P<0.05; ANOVA; Fig. 3A), similar to Matrigel-coated surfaces. Statistically significant increases in α4 and α5 subunit activity, and decreases in α6 and β1 engagement, were observed compared to Matrigel (P<0.05; ANOVA; Fig. 3A).

Figure 3.

Integrin usage and hES cell fate on multiple peptide-coated substrata. Cell culture substrata were coated with various ratios of AG-10, C-16, and AG-73 peptides, and analyzed for integrin usage and self-renewal. A) Antibody-blocking assay for hES cell attachment to AG-10:C-16:AG-73 (60:16:24%) and Matrigel-coated surfaces. Before seeding, cells were preincubated with various integrin antibodies for 30 min at 37°C. Attachment of hES cells to the AG-10:C-16:AG-73 (60:16:24%) combination was significantly inhibited by α4, α5, α6, β1, α2β1, and αvβ3 antibody antagonists, revealing that the combination selected mimics the pattern of integrin engagement on Matrigel. Cells that were not preincubated with an antibody were used as controls. *P < 0.05; ANOVA. B) For substrata coated with AG-10:C-16:AG-73 (60:16:24%), images of colony morphology and Oct4 and Tra-1-60 immunostaining of hES cells after 7 d of culture. Positive colonies stained green (left panels); nuclei were stained blue by DAPI (center panels); corresponding phase-contrast images are shown (right panels). Oct4 and Tra-1-60 immunostaining demonstrate maintenance of an undifferentiated phenotype. Scale bar = 500 μm.

H1 hES cells cultured on this multiple peptide-coated surface expressed the pluripotency markers Oct4 and Tra-1-60, and exhibited good colony morphology at d 7 compared to individual peptides (Fig. 3B and Supplemental Fig. S3). hES cells on this combination were round multilayered colonies with defined borders surrounded by stromal cells at the colony boundaries. Under high magnification, individual cells had a high nucleus to cytoplasm ratio, and cell colonies exhibited similar morphology as that of cultures on Matrigel after 7 d of culture. We could maintain undifferentiated hES cells on the triple peptide surface for three passages, after which the majority of colonies remained undifferentiated, but some cells began to differentiate.

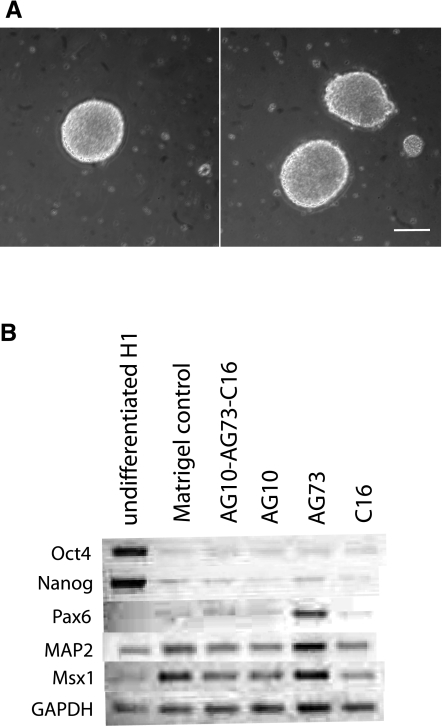

As a functional measure of pluripotency, we next tested the differentiation capacity of H1 hES cells that had been cultured on the synthetic peptides. H1 hES cells were grown on individual and combination peptides for two passages and then differentiated to EBs for 4 d (Fig. 4) (35). EBs formed from cells on the combination peptide surface were morphologically indistinct from those grown on Matrigel (Fig. 4A). To characterize the extent of differentiation, we used RT-PCR to detect genetic markers of the embryonic germ layers. EBs from all surfaces showed down-regulation of the pluripotency genes Oct4 and Nanog similar to those from the Matrigel control (Fig. 4B). The transcription factor Pax6 is an important factor in the specification of tissues in early development, and its expression was used as an indicator of ectodermal differentiation (38). MAP2 was also used as an ectodermal marker, since it encodes a protein important in neurogenesis. MSX1 is a transcription factor that specifies limb development and was used as a marker of mesodermal tissues (38). EBs formed from cells on the combination peptide expressed ectoderm and mesoderm markers similar to control Matrigel EBs (Fig. 4B), indicating multilineage differentiation potential of cells cultured in completely defined conditions.

Figure 4.

EB differentiation. A) Cells grown on surfaces coated with Matrigel (left panel) and a combination of peptides (right panel) for 2 passages were differentiated to EBs. B) After 4 d, markers of embryonic germ layers were assessed by RT-PCR. Scale bar = 250 μm.

DISCUSSION

Genomic data from several hES cell lines, including microarray data, EST analysis, and massively parallel signature sequencing (MPSS) (39, 40) have provided evidence for the expression of different integrin subunits by hES cells. In addition, flow cytometry has been used to validate genomic data for laminin-binding integrin expression on hES cells cultured in MEF-conditioned medium (8). In this work, we report the expression level of a broader panel of integrins expressed by hES cells, as well as analyze integrin expression and function for hES cells grown in a defined system, i.e., culture on Matrigel-coated substrata in NC-SFM conditions. Subsequently, we used this information to define peptide ligands as a tool to dissect which integrin inputs may be involved in hES adhesion with Matrigel. Ultimately, we envisage incorporation of these integrin-engaging peptides into completely synthetic hES cell culture systems.

hES cells expressed a broad range of integrins that use several ECM proteins as their ligands (e.g., laminin, collagen, fibronectin, and vitronectin). Specifically, the RT-PCR results indicated that H1 hES cells expressed mRNA for integrin subunits α1, α2, αIIb, α3, α4, α5, α6, αV, β1, β3, β4, and β6. These data were supported by flow cytometry results that indicated >90% of cells were β1, α6, and α2 positive; >80% of cells were β3, α1, α3, and αv positive; 40% of cells were αvβ3 positive; and <25% of hES cells were β4 positive. Immunofluorescence results confirmed that the colonies were positive for the α6, β1, αvβ3, and α2β1 integrins. These results were similar to previously published work involving culture in serum-containing medium (8), with the difference that the expression levels of the α1 and α3 subunits were much higher in the current study. These differences could be attributed to potentially interesting changes in integrin expression due to the cell culture conditions, such as MEF-conditioned vs. NC-SFM.

Although our results indicated that numerous integrins were expressed by hES cells, studies with antibody antagonists of these integrins showed that only the α6, β1, α2β1, and αvβ3 integrins contributed to hES cell adhesion to Matrigel-coated substrata, which further confirmed the immunostaining data. These integrins are known to bind to laminins, collagens, fibronectin, vitronectin, and other ECM proteins. The usage of the β1 integrin may be critical, as it plays a crucial role in early phases of the development, and β1-null mice are embryonically lethal (23,24,25). The α6 subunit has two variants, α6A and α6B, that differ in their cytoplasmic domains and are expressed throughout development (41, 42). The α6B subunit is expressed exclusively in undifferentiated mouse ES cells and in the inner cell mass (42,43,44), while the α6A subunit’s expression increases significantly in early differentiation. The α6 and β1 subunits, which were strongly inhibited by their respective antibodies, presumably form a heterodimer that plays an important role in hES cell adhesion to Matrigel and is consistent with the high level of laminin-111 in this ECM blend. To a lesser extent, the α2β1 and αvβ3 integrins also mediated hES cell adhesion to Matrigel; however, much less is known regarding their potential function with ES cells and in early organismal development. The αvβ3 integrin was first identified as the “vitronectin receptor,” but it can engage with several other ECM proteins found in Matrigel, including laminin-111 and collagen IV (45, 46), and can promote adhesion, spreading, and locomotion of various cell types. The α2β1 integrin is known as the “collagen receptor,” due to is widespread engagement with various collagens (47), but it has also been shown to couple with laminin in some cell types.

We explored three synthetic peptides AG-10, C-16, and AG-73, all derived from the laminin-111, for their ability to recapitulate the hES cell integrin usage on Matrigel in NC-SFM. Laminin-111 is the major component and cell adhesion protein of the basement membrane matrix, likely plays a role in organizing this structure, and is also present in Matrigel (18). The AG-10 peptide, derived from the COOH–terminal globular domain of the laminin-111 α1 chain, supported considerable hES cell adhesion but could not maintain hES cells in an undifferentiated state. Interference with integrin-blocking antibodies indicated that hES cell adhesion to AG-10 was mediated through α5, α6, β1, and α2β1 integrins. In contrast, C-16 maintained hES cells in an undifferentiated state by engaging the αvβ3 integrin. As the syndecans, a family of transmembrane (type I) heparan sulfate proteoglycans, are capable of stimulating cell adhesion, intracellular signaling, proliferation, and locomotion, we also examined the effect of AG-73 on hES cell culture. The nonintegrin engaging AG-73 peptide was derived from a region of laminin-111 that is highly conserved, suggesting it plays an important biological role. Like AG-10, cell-type-specific attachment activities have been observed for AG-73 (31, 37). We found that AG-73 promoted hES cell adhesion and supported pluripotency similar to the other peptides.

Although all of the individual synthetic peptides could support initial cell attachment and pluripotency, deterioration of the ability to maintain self-renewal hES cells was observed at longer time points. This led us to investigate whether a blend of several peptides could recapitulate the supportive properties of Matrigel. Cell adhesion to a blend of 3 peptides at the molar ratio 60:16:24% (AG-10:C-16:AG-73) was superior to individual peptides and was functionally blocked by anti-α4, -α5, -α6, -αv, -β1, -α2β1, and -αvβ3 antagonists, nearly matching the profile of integrin usage by hES cells on Matrigel. Compared to integrin engagement on Matrigel, notable differences on the triple peptide-coated substrates were the increased reliance on the α4 and α5 subunits and the decreased engagement of the α6 and β1 integrins. Cells grown on this combination exhibited good colony morphology and expression of hES markers at d 7 indistinguishable from those grown on Matrigel.

The triple peptide combination was capable of supporting multilineage differentiation in a manner equivalent to that of Matrigel-coated substrata. EBs from the peptide-cultured cells were morphologically indistinct from those grown on Matrigel and had similar gene expression profiles as well. In our experiments and others that employed a short-term EB differentiation process, it was not possible to detect expression of endodermal markers, even in cells grown on Matrigel-coated plates, indicating that endodermal induction requires a longer differentiation period (48).

We maintained undifferentiated hES cells on the triple peptide surface for three passages, after which the majority of colonies remained undifferentiated, but some cells began to differentiate. We believe the slow progression toward differentiation on the triple peptide surface was due to unligated α6β1 integrins, potentially leading to integrin-mediated apoptosis of hES cells and promotion of the stromal cells derived from the ES cells (29, 49). We are in the process of testing this concept by both defining α6B-positive cells and peptides that ligate that integrin.

CONCLUSIONS

The present studies are the first to address the integrin usage profile of hES cells cultured on Matrigel cultured in NC-SFM, as well as to analyze cell adhesion and maintenance on multiple synthetic peptides designed to mimic hES cell integrin usage on Matrigel. Our aim was to investigate robust synthetic peptides as tools to dissect the functional importance of integrin engagement on hES cell maintenance. In the future, these results can lead to more sophisticated and better-defined peptide interfaces that support hES cell self-renewal and differentiation (50, 51). The translation of hES cells toward regenerative medicine efforts will significantly benefit from the development of these synthetic interfaces and NC-SFM conditions that support cell growth and differentiation. Basic knowledge of integrin receptors and syndecans that hES cells employ to bind to these substrata will also aid in this development.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This work was supported in part by the University of California Discovery Grant program (bio06-10597) and Geron Corporation (Menlo Park, CA, USA), as well as by U.S. National Institutes of Health grants NIH R21DE18044, R21DE018044, and R01GM085754. The authors thank Elizabeth Irwin and Eric Jabart (University of California–Berkeley) for their critical reading of the manuscript. The authors thank Kiichiro Tomoda and Shinya Yamanaka (Gladstone Institute of Cardiovascular Disease, San Francisco, CA, USA) for the pluripotency and germ layer marker PCR primers and reaction conditions. Y.M., S.E., and Y.J.L. were responsible for collection and/or assembly of data, data analysis and interpretation, and manuscript writing. R.S. was responsible for collection and/or assembly of data, and manuscript writing. D.V.S. was responsible for conception and design, financial support, data analysis and interpretation, and manuscript writing. K.E.H. was responsible for conception and design, financial support, data analysis and interpretation, manuscript writing, and final approval of manuscript.

References

- Thomson J A, Itskovitz-Eldor J, Shapiro S S, Waknitz M A, Swiergiel J J, Marshall V S, Jones J M. Embryonic stem cell lines derived from human blastocysts. Science. 1998;282:1145–1147. doi: 10.1126/science.282.5391.1145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reubinoff B E, Pera M F, Fong C Y, Trounson A, Bongso A. Embryonic stem cell lines from human blastocysts: somatic differentiation in vitro. Nat Biotechnol. 2000;18:399–404. doi: 10.1038/74447. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martin M J, Muotri A, Gage F, Varki A. Human embryonic stem cells express an immunogenic nonhuman sialic acid. Nat Med. 2005;11:228–232. doi: 10.1038/nm1181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Richards M, Fong C Y, Chan W K, Wong P C, Bongso A. Human feeders support prolonged undifferentiated growth of human inner cell masses and embryonic stem cells. Nat Biotechnol. 2002;20:933–936. doi: 10.1038/nbt726. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheng L Z, Hammond H, Ye Z H, Zhan X C, Dravid G. Human adult marrow cells support prolonged expansion of human embryonic stem cells in culture. Stem Cells. 2003;21:131–142. doi: 10.1634/stemcells.21-2-131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Genbacev O, Krtolica A, Zdravkovic P, Zdravkovic T, Brunette E, Powell S, Nath A, Caceres E, McMaster M, McDonagh S, Li Y, Mandalam R, Lebkowski J, Fisher S L. Serum-free derivation of human embryonic stem cell lines on human placental fibroblast feeders. Fertil Steril. 2005;83:1517–1529. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2005.01.086. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chase L G, Firpo M T. Development of serum-free culture systems for human embryonic stem cells. Curr Opin Chem Biol. 2007;11:367–372. doi: 10.1016/j.cbpa.2007.06.421. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu C H, Inokuma M S, Denham J, Golds K, Kundu P, Gold J D, Carpenter M K. Feeder-free growth of undifferentiated human embryonic stem cells. Nat Biotechnol. 2001;19:971–974. doi: 10.1038/nbt1001-971. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li Y, Powell S, Brunette E, Lebkowski J, Mandalam R. Expansion of human embryonic stem cells in defined serum-free medium devoid of animal-derived products. Bio/Technol Bioengin. 2005;91:688–698. doi: 10.1002/bit.20536. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beattie G M, Lopez A D, Bucay N, Hinton A, Firpo M T, King C C, Hayek A. Activin A maintains pluripotency of human embryonic stem cells in the absence of feeder layers. Stem Cells. 2005;23:489–495. doi: 10.1634/stemcells.2004-0279. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ludwig T E, Bergendahl V, Levenstein M E, Yu J Y, Probasco M D, Thomson J A. Feeder-independent culture of human embryonic stem cells. Nat Methods. 2006;3:637–646. doi: 10.1038/nmeth902. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ludwig T E, Levenstein M E, Jones J M, Berggren W T, Mitchen E R, Frane J L, Crandall L J, Daigh C A, Conard K R, Piekarczyk M S, Llanas R A, Thomson J A. Derivation of human embryonic stem cells in defined conditions. Nat Biotechnol. 2006;24:185–187. doi: 10.1038/nbt1177. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xiao L, Yuan X, Sharkis S J. Activin A maintains self-renewal and regulates fibroblast growth factor, Wnt, and bone morphogenic protein pathways in human embryonic stem cells. Stem Cells. 2006;24:1476–1486. doi: 10.1634/stemcells.2005-0299. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yao S, Chen S, Clark J, Hao E, Beattie G M, Hayek A, Ding S. Long-term self-renewal and directed differentiation of human embryonic stem cells in chemically defined conditions. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2006;103:6907–6912. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0602280103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu Y X, Song Z H, Zhao Y, Qin H, Cai J, Zhang H, Yu T X, Jiang S M, Wang G W, Ding M X, Deng H K. A novel chemical-defined medium with bFGF and N2B27 supplements supports undifferentiated growth in human embryonic stem cells. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2006;346:131–139. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2006.05.086. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fletcher J M, Ferrier P M, Gardner J O, Harkness L, Dhanjal S, Serhal P, Harper J, Delhanty J, Brownstein D G, Prasad Y R, Lebkowski J, Mandalam R, Wilmut I, De Sousa P A. Variations in humanized and defined culture conditions supporting derivation of new human embryonic stem cell lines. Clon Stem Cells. 2006;8:319–334. doi: 10.1089/clo.2006.8.319. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kleinman H K, McGarvey M L, Liotta L A, Robey P G, Tryggvason K, Martin G R. Isolation and characterization of type-iv procollagen, laminin, and heparan-sulfate proteoglycan from the EHS sarcoma. Biochemistry. 1982;21:6188–6193. doi: 10.1021/bi00267a025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hansen K C, Kiemele L, Maller O, O'Brien J, Shankar A, Fornetti J, Schedin P. An in-solution ultrasonication-assisted digestion method for improved extracellular matrix proteome coverage. Mol Cell Proteomics. 2009;8:1648–1657. doi: 10.1074/mcp.M900039-MCP200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ruoslahti E, Pierschbacher M D. New perspectives in cell adhesion: RGD and integrins. Science. 1987;238:491–497. doi: 10.1126/science.2821619. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hynes R O. Integrins: bidirectional, allosteric signaling machines. Cell. 2002;110:673–687. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(02)00971-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hayashi Y, Furue M K, Okamoto T, Ohnuma K, Myoishi Y, Fukuhara Y, Abe T, Sato J D, Hata R I, Asashima M. Integrins regulate mouse embryonic stem cell self-renewal. Stem Cells. 2007;25:3005–3015. doi: 10.1634/stemcells.2007-0103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tanentzapf G, Devenport D, Godt D, Brown N H. Integrin-dependent anchoring of a stem-cell niche. Nat Cell Biol. 2007;9:1413–1418. doi: 10.1038/ncb1660. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Adjaye J, Huntriss J, Herwig R, BenKahla A, Brink T C, Wierling C, Hultschig C, Groth D, Yaspo M L, Picton H M, Gosden R G, Lehrach H. Primary differentiation in the human blastocyst: Comparative molecular portraits of inner cell mass and trophectoderm cells. Stem Cells. 2005;23:1514–1525. doi: 10.1634/stemcells.2005-0113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fassler R, Pfaff M, Murphy J, Noegel A A, Johansson S, Timpl R, Albrecht R. Lack of β-1 integrin gene in embryonic stem-cells affects morphology, adhesion, and migration but not integration into the inner cell mass of blastocysts. J Cell Biol. 1995;128:979–988. doi: 10.1083/jcb.128.5.979. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stephens L E, Sutherland A E, Klimanskaya I V, Andrieux A, Meneses J, Pedersen R A, Damsky C H. Deletion of β-1 integrins in mice results in inner cell mass failure and periimplantation lethality. Genes Dev. 1995;9:1883–1895. doi: 10.1101/gad.9.15.1883. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ilic D, Almeida E A C, Schlaepfer D D, Dazin P, Aizawa S, Damsky C H. Extracellular matrix survival signals transduced by focal adhesion kinase suppress p53-mediated apoptosis. J Cell Biol. 1998;143:547–560. doi: 10.1083/jcb.143.2.547. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ingber D E. Tensegrity II. How structural networks influence cellular information processing networks. J Cell Sci. 2003;116:1397–1408. doi: 10.1242/jcs.00360. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang N, Butler J P, Ingber D E. Mechanotransduction across the cell-surface and through the cytoskeleton. Science. 1993;260:1124–1127. doi: 10.1126/science.7684161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stupack D G, Puente X S, Boutsaboualoy S, Storgard C M, Cheresh D A. Apoptosis of adherent cells by recruitment of caspase-8 to unligated integrins. J Cell Biol. 2001;155:459–470. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200106070. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nakahara H, Nomizu M, Akiyama S K, Yamada Y, Yeh Y Y, Chen W T. A mechanism for regulation of melanoma invasion—ligation of α(6)β(1) integrin by laminin G peptides. J Biol Chem. 1996;271:27221–27224. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.44.27221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nomizu M, Kim W H, Yamamura K, Utani A, Song S Y, Otaka A, Roller P P, Kleinman H K, Yamada Y. Identification of cell-binding sites in the laminin α-1 chain carboxyl-terminal globular domain by systematic screening of synthetic peptides. J Biol Chem. 1995;270:20583–20590. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.35.20583. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ponce M L, Nomizu M, Kleinman H K. An angiogenic laminin site and its antagonist bind through the alpha v beta 3 and alpha 5 beta 1 integrins. FASEB J. 2001;15:1389–1397. doi: 10.1096/fj.00-0736com. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoffman M P, Engbring J A, Nielsen P K, Vargas J, Steinberg Z, Karmand A J, Nomizu M, Yamada Y, Kleinman H K. Cell type-specific differences in glycosaminoglycans modulate the biological activity of a heparin-binding peptide (RKRLQVQLSIRT) from the G domain of the laminin alpha 1 chain. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:22077–22085. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M100774200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rezania A, Healy K E. Integrin subunits responsible for adhesion of human osteoblast-like cells to biomimetic peptide surfaces. J Orthopaed Res. 1999;17:615–623. doi: 10.1002/jor.1100170423. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li X J, Zhang S C. In vitro differentiation of neural precursors from human embryonic stem cells. Methods Mol Biol. 2006;331:169–177. doi: 10.1385/1-59745-046-4:168. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kleinman H K, Hewitt A T, Murray J C, Liotta L A, Rennard S I, Pennypacker J P, McGoodwin E B, Martin G R, Fishman P H. Cellular and metabolic specificity in the interaction of adhesion proteins with collagen and with cells. J Supramol Struct. 1979;11:69–78. doi: 10.1002/jss.400110108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoffman M P, Nomizu M, Rogue E, Lee S, Jung D W, Yamada Y, Kleinman H K. Laminin-1 and laminin-2 G-domain synthetic peptides bind syndecan-1 and are involved in acinar formation of a human submandibular gland cell line. J Biol Chem. 1998;273:28633–28641. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.44.28633. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takahashi K, Tanabe K, Ohnuki M, Narita M, Ichisaka T, Tomoda K, Yamanaka S. Induction of pluripotent stem cells from adult human fibroblasts by defined factors. Cell. 2007;131:861–872. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2007.11.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brandenberger R, Wei H, Zhang S, Lei S, Murage J, Fisk G J, Li Y, Xu C H, Fang R, Guegler K, Rao M S, Mandalam R, Lebkowski J, Stanton L W. Transcriptome characterization elucidates signaling networks that control human ES cell growth and differentiation. Nat Biotechnol. 2004;22:707–716. doi: 10.1038/nbt971. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miura T, Luo Y Q, Khrebtukova I, Brandenberger R, Zhou D X, Thies R S, Vasicek T, Young H, Lebkowski J, Carpenter M K, Rao M S. Monitoring early differentiation events in human embryonic stem cells by massively parallel signature sequencing and expressed sequence tag scan. Stem Cells Dev. 2004;13:694–715. doi: 10.1089/scd.2004.13.694. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cooper H M, Tamura R N, Quaranta V. The major laminin receptor of mouse embryonic stem-cells is a novel isoform of the alpha-6-beta-1 integrin. J Cell Biol. 1991;115:843–850. doi: 10.1083/jcb.115.3.843. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hierck B P, Thorsteinsdottir S, Niessen C M, Freund E, Iperen L V, Feyen A, Hogervorst F, Poelmann R E, Mummery C L, Sonnenberg A. Variants of the alpha(6)beta(1)-laminin receptor in early murine development - distribution, molecular-cloning and chromosomal localization of the mouse integrin alpha(6)-subunit. Cell Adhes Commun. 1993;1:33–53. doi: 10.3109/15419069309095680. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hogervorst F, Admiraal L G, Niessen C, Kuikman I, Janssen H, Daams H, Sonnenberg A. Biochemical-characterization and tissue distribution of the a-variant and b-variant of the integrin alpha-6 subunit. J Cell Biol. 1993;121:179–197. doi: 10.1083/jcb.121.1.179. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tamura R N, Cooper H M, Collo G, Quaranta V. Cell type-specific integrin variants with alternative alpha-chain cytoplasmic domains. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1991;88:10183–10187. doi: 10.1073/pnas.88.22.10183. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith J W, Cheresh D A. Integrin (alpha-v-beta-3)-ligand interaction-identification of a heterodimeric rgd binding-site on the vitronectin receptor. J Biol Chem. 1990;265:2168–2172. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Horton M. Vitronectin receptor: Tissue-specific expression or adaptation to culture? Intl J Exp Pathol. 1990;71:741–759. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Staatz W D, Walsh J J, Pexton T, Santoro S A. The alpha 2 beta 1 integrin cell surface collagen receptor binds to the alpha 1 (I)-CB3 peptide of collagen. J Biol Chem. 1990;265:4778–4781. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leahy A, Xiong J W, Kuhnert F, Stuhlmann H. Use of developmental marker genes to define temporal and spatial patterns of differentiation during embryoid body formation. J Exp Zool. 1999;284:67–81. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-010x(19990615)284:1<67::aid-jez10>3.0.co;2-o. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stupack D G, Cheresh D A. Get a ligand, get a life: integrins, signaling and cell survival. J Cell Sci. 2002;115:3729–3738. doi: 10.1242/jcs.00071. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li Y J, Chung E H, Rodriguez R T, Firpo M T, Healy K E. Hydrogels as artificial matrices for human embryonic stem cell self-renewal. J Biomed Mat Res A. 2006;79A:1–5. doi: 10.1002/jbm.a.30732. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Derda R, Li L Y, Orner B P, Lewis R L, Thomson J A, Kiessling L L. Defined substrates for human embryonic stem cell growth identified from surface arrays. ACS Chem Biol. 2007;2:347–355. doi: 10.1021/cb700032u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.