Abstract

This qualitative study examined how Native Hawaiian youth from rural communities utilized cultural practices to promote drug resistance and/or abstinence. Forty-seven students from 5 different middle schools participated in gender specific focus groups that focused on the cultural and environmental contexts of drug use for Native Hawaiian youth. The findings described culturally specific activities that participants used in drug related problem situations. The findings also suggested that those youth with higher levels of enculturation were able to resist drugs more effectively than those youth who were disconnected from their culture. The implications of these findings for social work practice are discussed.

KEYTERMS: Hawaiian, youth, drugs, culture, enculturation

INTRODUCTION

Over the past decade, there has been an increase in research focused on cultural context and drug use, including studies focused on Mexican/Mexican American and African American youth (Hecht et al., 2003; Kulis et al., 2005) and American Indian youth (Moran & Bussey, 2007; Schinke, Tepavac, & Cole, 2000). Further, there have been theoretical examinations of culture and drug use, in an effort to understand the relationship between the two constructs (Oetting, Donnemeyer, Trimble, & Beauvais, 1998; Bates, Beauvais, & Trimble, 1997). Implicit in this research is the acknowledgement that culture plays a significant role in behaviors, including decisions to use or resist drugs. However, none of this research has examined youth populations in the Pacific, such as Native Hawaiian youth. Understanding the cultural context of drug use for Hawaiian youth is an important step in alleviating health disparities for Native Hawaiians. It may also have implications for understanding the culturally specific etiology of drug use for other indigenous youth populations as well as youth populations of the Pacific.

This paper describes how Hawaiian youth from selected rural communities utilized cultural values and practices to promote drug resistance and/or abstinence. Specifically, it seeks to understand how the Hawaiian culture—through its way of life, and cultural practices, values, or activities—affects the repertoire of relevant drug resistance skills and risk for drug use for these youth. Implications of cultural practices for drug prevention with rural Hawaiian communities are discussed.

LITERATURE REVIEW

Native Hawaiian Youth and Drug Use

Among youth ethnic groups in Hawai‘i, drug use rates are the highest for Native Hawaiian youth. In school-based surveys, Native Hawaiian youth reported the highest lifetime and 30-day rates of using alcohol, tobacco, and other drugs (ATOD) compared with other youth ethnic groups (Wong, Klingle, & Price, 2004; Lai & Saka, 2005). Compared to their non-Hawaiian counterparts, they also have reported the earliest age of substance use onset (Ramisetty-Mikler, Caetano, Goebert, & Nishimura, 2004). Higher rates of drinking problems, such as binge and chronic drinking (Johnson, Nagoshi, Ahern, Wilson, & Yuen, 1987), as well as the highest need for drug related treatment (Wong et al., 2004) have been found for Native Hawaiian youth compared with other youth ethnic groups. These findings suggest that drug use is a serious problem within Hawaiian communities, and that there is a need for culturally relevant, use-inspired research to alleviate its effects on Hawaiian youth and their families.

Enculturation/Ethnic Pride

Enculturation is the process by which individuals learn about and identify with their culture of origin (Zimmerman, Ramirez-Valles, Washienko, Walter, & Dyer, 1996). For Native American youth populations, cultural affinity (ethnic pride), Native identity, and family involvement in traditional activities have been found to adequately represent the construct of enculturation (Zimmerman et al., 1996). These findings are consistent with culturally specific theories of socialization (Oetting et al., 1998). For example, Oetting et al. describes how the process of learning occurs predominantly through primary socialization sources (i.e., the family, the school, and peer clusters). For Native Hawaiian youth, this process serves true as Native Hawaiians identify and understand themselves through social relationships (Pukui, Haertig, & Lee, 1972).

Based on sociohistorical similarities and modern day issues, the construct of enculturation, as defined by Zimmerman et al. (1996) for Native American youth, is most likely applicable to Native Hawaiian youth as well. Similar to Native Americans, Native Hawaiians are indigenous people to their homeland, and both populations experienced heavy western colonization which resulted from promulgation of the European culture through missionaries and political domination by the United States of America (Nicols, 1990–1991; Yuen, Nahulu, Hishinuma & Miyamoto, 2000). The process of enculturation can be viewed as an outgrowth from these shared traumatic events. It is distinct from acculturation, which results from sustained contact between two or more distinct cultures and often results in one culture being dominated and/or assimilated by the other (Huriwai, 2002). Unlike acculturation, enculturation does not define itself against the norms of another culture, but represents the effort that Native peoples make to regain their ancestral cultures (Napoli, Marsiglia, & Kulis, 2003).

The resurgence of cultural practices, values, and beliefs has been shown to promote psychosocial health and decreased substance use among Native populations. Research suggests that revitalization of culture-related factors (e.g., family support systems, healing rituals) plays a role in the reduction of suicide rates and alcohol abuse among Native American youth (Canda & Yellow Bird, 1997). The same can be said for Native Hawaiian youth, as “greater self-esteem” (a protective factor against drug use) was found among Native Hawaiians who took Hawaiian language classes (Gaughen, 1996). In a study examining alcohol, tobacco, other drug use, and violent behavior among Native Hawaiians, the findings indicated that those who had a greater sense of ethnic pride reported to be “significantly happier” than those who did not (Austin, 2004). High reports of ethnic pride were also associated with those who had less exposure to witnessing or being a perpetrator of violence, and/or being a victim of violence.

Hawaiian Enculturation

Defining Hawaiian Culture

In order to understand Hawaiian enculturation, it is important to understand the social and behavioral constructs that define Hawaiian culture. Rezentes (1993) identified these constructs in the development of the Nā Mea Hawai‘i (“Hawaiian Ways”) scale, which was designed to measure “how culturally Hawaiian a person is by contemporary Hawaiian standards” (p. 384). Using an adult sample, Rezentes found that the most salient concepts related to Hawaiian culture (i.e., those which differentiated Hawaiians from non-Hawaiians) included language, food, cultural customs or events (e.g., net fishing, baby lū ‘au), and religious or spiritual beliefs. Hishinuma et al. (2000) examined the applicability of these findings for Native Hawaiian adolescents. They found that Hawaiian youth identified core constructs of Hawaiian culture that were similar to the adult respondents in Rezentes’ study. In particular, Hawaiian activities, such as hula or canoe paddling, differentiated Native Hawaiian from non-Hawaiian youth in their study. Hishinuma et al. also found that Native Hawaiian youth had a more positive ethnic identity when the Hawaiian way of life was taught through the family. The importance of the family in the Hawaiian culture is suggested to be the reason for this (Hishinuma et al., 2000; McCubbin, Ishikawa, & McCubbin, 2007). The family oriented value system (i.e., ‘ohana system) that is pervasive within the Native Hawaiian culture promotes interdependence among immediate and extended family members, and influences their values, beliefs, and behaviors (Miike, 1996). Lastly, Hishinuma et al. recommended that more research is needed to link the constructs that define Hawaiian culture to indicators of psychological adjustment, such as depression, anxiety, and substance abuse.

Hawaiian Value of Pono

Native Hawaiian cultural beliefs and practices are deeply rooted in values that perpetuate the idea of living pono, or living righteously (Pukui et al., 1972). Historically, Native Hawaiians believed in the connection between themselves (kanaka maoli), the god(s) (ke akua), and nature (‘āina) (Dudley, 1990; McGregor, 2007). In maintaining this connection, they made sure they were in lokahi (or harmony) with all elements, and that they lived by the standard of being pono (Kanahele, 1986; Streltzer, Rezentes, & Arakaki, 1996). In other words, it was important that they lived justly and valued everything in nature as a living being. What was taken from the land (or the ocean) was for subsistence purposes, and when it occurred, it was within a strict protocol (McGregor, 2007). Pono also extends into the very being of the person. This means that the individual is expected to “behave in a pono way,” that is, to do things that are “right” and “just,” and to extend that thinking and goodness to their relationship with others (McCubbin et al., 2007). Along with pono and lokahi, other important Hawaiian values such that of aloha (affection, love), and kōkua (helping others), are key cultural values that are significant in understanding the Native Hawaiian culture (McCubbin, 2003; McCubbin et al., 2007). This study examined how these traditional cultural practices and values are manifested in the lives of modern-day Native Hawaiian youth within rural communities, and how they used these concepts to cope with difficult or challenging drug related problem situations in their homes, schools, and communities.

METHOD

This study focused on two research questions: (1) In what way(s) do Native Hawaiian youth in rural communities utilize cultural practices, values, and beliefs in drug related problem situations? and (2) How do rural Hawaiian youth who regularly draw upon these cultural practices, values, and beliefs qualitatively differ in their perceptions of drug related problem situations from those youth who do not draw upon them? Because of the exploratory nature of this study, qualitative methods were used to examine the relationship between Hawaiian cultural practices, values, and beliefs, and drug resistance. These methods have recently been used in similar studies in rural areas of Hawai‘i, because they promote community participation (Affonso et al., 2007) and investment (Withy et al., 2007).

Data Collection and Participants

Five rural middle schools participated in the study—four schools on the island of Hawai‘i (also known as the “Big Island”) plus one pilot study school from a different island. Fourteen focus “mini” groups (Morgan, 1997) with 2–5 Native Hawaiian middle school students per group were conducted (n = 47). Smaller (versus larger) groups were selected, because of the sensitive nature of the research and because they were more consistent with cultural norms of rural Hawaiian communities. In order to promote participants’ comfort in disclosing drug related information, homogeneity of group composition (Morgan, 1996; Zeller, 1993) was built into the research design. This was achieved in two ways. First, separate groups were held for girls (n = 26) and boys (n = 21), with group facilitators matching the gender of the youth participants. Second, efforts were made to create groups using naturally formed social cliques. Participants were in grades 6 (9%), 7 (53%) and 8 (38%). The average age of participating youth was 12.2 years. All students self-identified primarily as Native Hawaiian, even though all of them were of mixed ethnocultural backgrounds. In addition to Hawaiian ancestry, students were also from Pacific (e.g., Tahitian, Samoan), Asian American (e.g., Japanese, Korean), Euro-American (e.g., Portuguese), and American Indian ethnocultural groups.

Interviews were held at school, either during lunch, recess, or after school, and lasted from 40–60 minutes. The groups began with a discussion “starter” question (Morgan, 1997), in which students were asked to imagine a scenario where someone important to them had offered them drugs or alcohol. This question led students to describe real situations in which drugs had been offered to them or someone they knew, and to share their views on the extent of the drug problem in their school or community and what could be done about it. Particular attention was given to the time, place, drug offerer, and drugs used in specific situations described by the youth. In several groups, students were directly asked about the ways in which cultural values, practices, and beliefs helped middle school youth resist alcohol, marijuana, cigarettes, and other drugs.

Participants were informed to keep all youth disclosures in the group setting confidential. Because we audio recorded the interviews, we asked youth to use self-selected pseudonyms to refer to one’s self and others in the group discussions, as well as to refer to individuals in their stories. Active parental consent and student assent were obtained for all participants in the study. All research procedures were approved by the Institutional Review Boards at Hawai‘i Pacific University, University of Hawai‘i at Mānoa, and the State of Hawai‘i Department of Education.

Data Analysis

All interviews were audio recorded and transcribed verbatim by a member of the research team. Transcripts were then reviewed for accuracy by a different research team member. Because little is known about the etiology of drug use for Native Hawaiian youth, this study used a grounded theory approach to data analysis in order to examine the relationship between cultural practices and drug use with this population. A comprehensive set of open codes (Strauss & Corbin, 1990) based on emergent themes in the narratives were identified by the Principal and Co-Principal Investigators, and were imported into a qualitative research data analysis program (QSR NVivo). QSR NVivo is one of several code-based theory-building programs that allow the researcher to represent relationships among codes or build higher-order classifications (Weitzman, 2000). In order to establish intercoder reliability and validity, all members of the research team collectively coded one transcript, in order to clarify the definition and parameters of all of the codes. Then, all subsequent interview transcripts were separately coded by at least two different research team members. Narrative segments that were not identically coded by the team members were identified, discussed, and justified for inclusion or exclusion in the data set. Upon establishing intercoder reliability and validity, axial and selective coding were conducted, which focused on respondents’ perceptions and practices of their culture and attitudes toward drug use. As described by Strauss and Corbin, axial and selective coding focus on specifying a phenomenon (in this case, substance use or resistance) in terms of its antecedent conditions (e.g., cultural practices), in order to understand the phenomenon at a higher level of analysis.

RESULTS

Of the 14 focus groups, 11 of them referenced Hawaiian cultural practices. For these groups, the mean percentage of coverage for the code was 6.801. Participants in the focus groups who described references to Hawaiian cultural beliefs, values, and/or practices fell into two categories. The first category included participants who utilized cultural practices and values to help in resisting drug offers. These participants also described an understanding of their culture in a way that illustrated drug use as being in opposition to their cultural values and beliefs. The data suggested that participants in this category possessed culturally specific skills to resist to drug offers, and were able to use them in difficult situations. The second category included participants who had a superficial or surface understanding of their culture and were unable to identify specific cultural values and/or practices to help in drug resistance. Participants in this category disclosed exposure to drug and alcohol offers, and appeared at higher risk for drug and alcohol use than their enculturated counterparts.

Cultural Identity as Drug Resistance

The participants’ narratives suggested that a strong connection to Hawaiian culture, demonstrated through cultural practices, functioned as a form of drug resistance for rural Hawaiian youth. For example, “Don” described the use of an indigenous form of fishing (“throwing net”) as a way in which he was able to resist a drug offer made by his friend’s uncle.

Don: Well, [we were] at a beach, and my friends’ uncle was drunk and was offering all kinds of beer. And, we said no. ‘Cause we know he was drunk and we didn’t wanna follow anything, or else somebody [was] going to get hurt.

Facilitator: So who [was] he offering it to?

Don: Just me and my friend.

Facilitator: So, his uncle offered both him and you what kind of alcohol?

Don: It was Bud Light or Budweiser.

Facilitator: So what did you do in that situation?

Don: We said no, and [were] trying to get him off the subject. Like, we [went to] go “throw net” in that area, so he would get [beer] off of [his] mind and then try to focus on what to do.

Facilitator: How did that work?

Don: It worked just fine. Once we caught fish, he forgot all about it.

Similarly, a group of female participants identified specific cultural practices that helped them to abstain from drug use.

Facilitator: [Do] you have [any] thoughts about any Hawaiian values or practices that help you stay healthy and resist drugs, alcohol, and tobacco.

Jane: What do you mean? You have to be Hawaiian? Because like there are a lot of other cultures that don’t do drugs, and don’t do tobacco, don’t do drink, or don’t smoke.

Dana: But she’s talking about Hawaiian kids and, [Jane: Yeah, their values] how we stay away from drugs

Facilitator: Yeah, do you have any specific cultural values or practices that help you?

Dana: Oooh, I do [Jane: Yeah]. Like hula.

Jane: We dance Tahitian, or we paddle.

Dana: Yeah, like stuff to keep me away from drugs, when I used to do them. Like, I’m getting into paddling; I’m dancing, and just doing stuff to keep me occupied, [so I won’t] turn back to drugs and stuff like that.

Some youth described how Hawaiian cultural values contribute to drug resistance. The youth in the following focus group described their ability to resist or abstain from drug use utilizing not only Hawaiian cultural practices, but Hawaiian values as well. These participants mentioned how the use of drugs and alcohol are in complete contrast to being “pono.” “Gabby” and “Sherry” acknowledged this relationship.

Gabby: ‘Cause if [you’re] smoking and stuff like that, it’s not being Hawaiian

Sherry: [You’re] not being pono.

Gabby: Yeah, that’s not being pono.

They then described how being “pono” extends to peer relationships.

Sherry: If you use drugs, you can go to jail, you [are] going to die, [and] you [are] not going to have that [many] friends. Or, if you [have] friends, [they’re] not really friends, ‘cause [if they were], they would tell you that it’s wrong for [you to] do that and [that] you should stop.

Gabby: [That’s] not being [a] pono friend.

Facilitator: So, a pono friend would do what?

Sherry: [They] would tell you [to] stop and [that] it’s not pono to be smoking pot, ‘cause you [are] going [to] hurt yourself and hurt others, too.

Gabby: A pono friend means that they would [not] risk your life for them and they wouldn’t give you pot and stuff like that…’cause your pono friend will help you out when you fall down. And, your friends that [are like] the “pakalolo people”, they [are] the ones hurting you. They [are] the ones [to] trip you.

“Gabby” and “Sherry” also identified the values of kuleana, laulima, and ho‘ihi, as well as caring for the ‘āina (land), as ways to promote drug resistance for Hawaiian youth.

Facilitator: How do you bring the Hawaiian cultural values or practice into keeping kids from using drugs?

Tehani: They should make schools like back in [another community across town]. They have three values: Kuleana, laulima, ho’ihi. That’s like [focusing on] the three values: Kuleana means responsibility, laulima is like working together and ho’ihi is respect.

Gabby: Yeah, like [if] you take care [of] the land [Tehani: the land going take care of you]. Yeah, but if you take care the land, that means that you[‘re] not littering, you[‘re] watering, you[‘re] helping the native plants and like you[‘re] [Sherry: Not giving them disease]. Yeah, not putting disease and chemicals inside the earth just for make ‘em grow.

Later, “Sherry” clarifies the relationship between caring for the ‘āina (land) and drug use. Specifically, she describes how the use of natural resources to cultivate drugs damages and disrespects the ‘āina.

Facilitator: So how does drugs play into that?

Sherry: If you use drugs, then [they are] going [to take away from] the earth and [they are] going like waste the earth, and you [are] not taking care of the earth or the land. So if you take care [of] the ‘āina, then [it’s] going [to] take care back to you. Like, you know how, when you take care [of] the ‘āina and stuff, and all the stuff [that] live[s] here, and you plant banana and stuff, and [it] help[s] you survive, after the thing [is] giving back to you. If you give to the ‘āina and you plant all stuff like that, the thing [is] going [to] give back by giving to you.

Lack of Connection to Culture and Drug Use

While some participants described ways in which cultural connection promoted drug resistance, others described how a lack of connection might promote drug use. For example, the following group of female youth, who resided in a community at high risk for drug and alcohol use, were unable to identify cultural values and or practices to help in drug resistance.

Facilitator: So is there something in the Native Hawaiian culture, that would be useful to [you], like you could say or do, in [drug related] situations?

Chrissy: Mmm, not really. Well, there might be, but I wouldn’t know about it, or I don’t know about it.

Facilitator: Ok. What about Kari, are you aware of any kind of Hawaiian cultur[al] things that would help you get out of [these] kinds of pressure situations?

Kari: No.

Similarly, another group of female participants described how they did not see the connection between cultural context (including Hawaiian culture) and drug resistance. The participants in this group all reported to be active users of drugs and alcohol. They were not connected to their culture in any meaningful way and were unable to identify any values or practices to help them resist drugs.

Facilitator: What about when you guys are choosing not to use drugs or alcohol in these situations. Is there something that you can rely on in the Hawaiian culture that you think about that helps you say, “oh no, I’m not going do stuff”? Or something about Hawaiian culture, values, or beliefs or things that Hawaiians’ do that are helpful for you in these situations?

Sunny: I haven’t really thought of it in that way.

Wilma: Yeah, I don’t know

Sunny: [Drug use] really has nothing to do with Hawaiian culture.

Wilma: It’s like a lot of Hawaiians are doing it nowadays.

These respondents also described limited and superficial descriptions of Hawaiian cultural values and beliefs.

Notetaker: [Are] Native Hawaiian values taught at all?

Sunny: No.

Wilma: Yeah.

Facilitator: What do they teach you at home? Wilma: They teach me to do my chores.

Sunny: Basic [things].

Wilma: Like, not [to] talk back to our parents, and stuff like that.

Later in the interview, the participants described being disconnected to or having a negative perception of the Hawaiian language, despite several participants’ exposure to the language from their parents.

Sunny: I can’t speak Hawaiian

Wilma: My mom, she’s a Hawaiian teacher, and she teaches about the Hawaiian stuff. She grumbles in Hawaiian.

Alana: My dad does that.

Facilitator: What does you dad do?

Alana: He yells at me, groans and whines like a little baby in Hawaiian. Or, like when I’m at my auntie’s house, if they don’t want me to hear what they’re saying, they talk in Hawaiian.

In some cases, drug-using participants described observations about their culture, but were unable to articulate the ways in which they were relevant in their lives. For example, several of the youths’ cultural quotes exemplified surface structure, such as canoe paddling or dancing hula; but did not elaborate on the deep structure of these practices. The following quote typifies this, in which “Sunny” describes Hawaiian spirituality, but is unable to connect how it is antithetical to drug use within the Hawaiian culture.

Facilitator: What do they teach you at home about Hawaiian stuff? Is it something you talk about at home as much, [or] not as much?

Sunny: It teaches you about your Hawaiian neighbors, what you do. My aunty guys, they’re really spiritual, not spiritual but like into that ‘kine of stuff. So like she’s involved in all these Hawaiian groups and she takes me with her. And [she takes me] when she makes leis for lei stands so she can make money, stuff like that. That’s all I know about Hawaiians.

DISCUSSION

The findings from this study suggested that Hawaiian youth participants who identified with their culture through beliefs, values, and practices resisted the use of drugs and alcohol. This was shown through the utilization of cultural practices as a way to draw attention away from a drug offer (e.g., “Don’s” use of “throwing net”) and participating in cultural activities to decrease opportunities for drug use (e.g., “Dana’s” participation in paddling and hula). It should be noted that these practices and activities functioned beyond their role as drug resistance strategies. A cultural practice such as hula is deeply rooted in the Hawaiian culture and embodies the very core of Hawaiian values and traditions. In this sense, these practices also may create a stronger cultural identity for the youth that participated actively in them.

Conversely, the findings also suggested that Hawaiian youth who were not as connected to their culture—through its language, customs, or activities—may be at higher risk for drug and alcohol use than those who were strongly connected to their culture. In some cases, exposure to and teachings of Hawaiian practices and traditions did not create the same deeper understanding or identity to the Hawaiian culture (e.g., “Alana’s” negative perception of the Hawaiian language, despite exposure to the language from her father). In other cases, participants expressed only a surface understanding of their culture (e.g., “Sunny’s” views on Hawaiian spirituality). These factors may have influenced the participants’ drug use on multiple levels. On the individual level, these youth may not have possessed culturally and regionally specific skills to resist drugs in difficult situations. On the family and community level, they may have been unable to draw upon social networks to help them abstain from drug use.

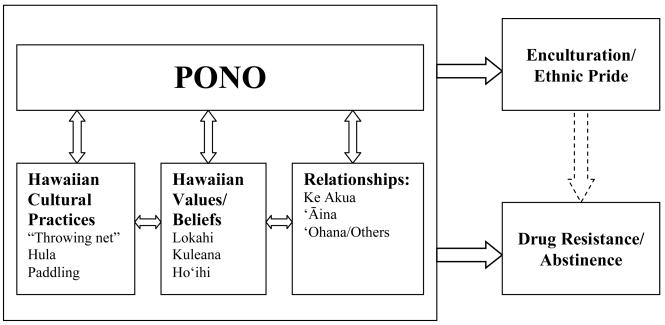

The findings presented in the study contribute to the understanding of culture and its relationship to drug use for Hawaiian youth. Participants described specific cultural practices, values and beliefs, and relationships to ‘āina (land) and ‘ohana (family), which are all conceptually interconnected to one another and are a part of the larger concept of living pono, or living righteously (see Figure 1). Specifically, Hawaiian cultural practices are deeply rooted in Hawaiian values and beliefs, which shape and are shaped by the relationships that are valued by the culture. The cultural practice of “throwing net,” for example, has the value of kuleana (responsibility), and represents a relationship with the ‘āina. In effect, Hawaiian fishermen are expected to know which parts of the ocean have been fished previously, and to only take what is needed. Living pono embodies this type of cultural framework; however, because of the cultural breadth and significance of the concept, it also is consistent with higher levels of enculturation/ethnic pride and inconsistent with drug use. Viewed in this way, living pono is a holistic and salient construct that influences both enculturation/ethnic pride and drug resistance. In the proposed model, enculturation/ethnic pride and drug resistance do not have any direct relationship with one another. As such, the model reflects research that has failed to find a direct relationship between certain cultural variables (e.g., acculturation) and drug use (Oetting et al., 1998).

FIGURE 1.

The Pono Model

Implications for Social Work Practice

The findings from this study have direct implications for social work practice with Native Hawaiian youth in rural communities. Specifically, the findings suggest that training in drug resistance should incorporate real world cultural practices of rural Hawaiians (e.g., “throwing net”) in order to develop relevant and meaningful skills to avoid drug use. For example, these skills could be introduced within the context of rural Hawaiian cultural practices in order to allow youth to practice drug resistance in real world settings. They could also be introduced within the context of the Hawaiian value of pono, which would promote enculturation and prevent drug use for Hawaiian youth. In other words, drug resistance skills might be best addressed using a holistic approach, encompassing the values of pono, for rural Hawaiian youth.

From a broader perspective, prevention programs built upon real world drug resistance strategies of rural Hawaiian youth and the value of pono have the potential to contribute to the development of evidence based practices for Hawaiian youth, other youth populations in the Pacific, and/or other Indigenous youth populations. There is a need for these types of programs. Rehuher, Hiramatsu, and Helm (in press) conducted a detailed examination of national registers of evidence-based youth drug prevention programs, and found a lack of these programs designed by or for Native Hawaiians. Further, Matsuoka (2007) argued that existing evidence based practices are “decontextualized,” and therefore have limited applicability to the Hawaiian population. The present study is an attempt to infuse Hawaiian culture and context into the “core” of drug prevention efforts, thereby enhancing both the fidelity and fit of these interventions (Castro, Becerra, & Martinez, 2004) and building culture deeper into the structure of these interventions (Ringwalt & Bliss, 2006). In terms of the latter issue, Ringwalt and Bliss emphasize how cultural context should be built into the “deep structure” of prevention programs for indigenous youth populations in order for them to be accepted and adopted by these populations This is particularly true for populations in rural Hawai‘i, as communities and local funders have recently questioned the validity and relevance of universal prevention programs for rural Hawaiian youth, and have been receptive to organic efforts to build their own prevention programs based on findings such as those presented in this study (Helm et al., in press).

Limitations of the Study

There were several limitations of this study. First, a comparison between the drug use risk of two groups of youth (culturally connected/enculturated versus culturally disconnected/non-enculturated) were made through qualitative methods. Typically, these comparisons are made using quantitative methods, in order to examine how enculturation and drug use covary with each other. Quantitative methods offer a level of measurement precision that was lacking from this study. Second, students were not directly asked if they used drugs or not in the focus group interviews. In effect, the analysis was limited to those students who voluntarily disclosed their drug use history. Third, a convenience sample was used in this study, which may not have been representative of the Hawaiian youth population in the sampled communities. Because of this, the findings may lack transferability to rural Hawaiian youth not participating in the study, particularly to those in communities outside of the sampling frame.

CONCLUSION

Research examining the relationship between levels of cultural connectedness and drug use has illustrated mixed findings, prompting the development of complex models to explain the relationship between the two constructs (Oetting et al., 1998). Despite its limitations, this study informs the theoretical literature on the relationship between culture and drug use by illustrating how rural Hawaiian youth use their cultural values and practices to resist drugs and to behave “in a pono way.” Future research might quantitatively examine the relationship between cultural values and practices, levels of enculturation, and drug use, in order to validate the preliminary findings described in this study. Finally, this study suggests that specific cultural practices may have a role in the content and/or delivery of prevention programs for rural Hawaiian youth.

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by funding from the National Institutes of Health/National Institute on Drug Abuse (K01 DA019884).

Footnotes

In N VIVO, “coverage” refers to the amount of text in a transcript that is devoted to a specific code.

References

- Affonso DD, Shibuya JY, Frueh BC. Talk-story: Perspectives of children, parents, and community leaders on community violence in rural Hawaii. Public Health Nursing. 2007;24(5):400–408. doi: 10.1111/j.1525-1446.2007.00650.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Austin AA. Alcohol, tobacco, other drug use, and violent behavior among Native Hawaiians: Ethnic pride and resilience. Substance Use & Misuse. 2004;39(5):721–746. doi: 10.1081/ja-120034013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bates SC, Beauvais F, Trimble JE. American Indian adolescent alcohol involvement and ethnic identification. Substance Use & Misuse. 1997;32(14):2013–2131. doi: 10.3109/10826089709035617. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Canda ER, Yellow Bird MJ. Another view: Cultural strengths are crucial. Families in Society. 1997;78(3):248. [Google Scholar]

- Castro FG, Barrera M, Martinez CR. The cultural adaptation of prevention interventions: Resolving tensions between fidelity and fit. Prevention Science. 2004;5:41–45. doi: 10.1023/b:prev.0000013980.12412.cd. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dudley MK. Hawaiian nation: Man, gods, and nature. Honolulu: Na Kane O Ka Malo Press; 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Gaughen K. Effects of participating in a Hawaiian language class on Hawaiian adolescents’ self-esteem and ethnic identity. University of Hawai‘i; Mānoa: 1996. Unpublished master’s thesis. [Google Scholar]

- Hecht ML, Marsiglia FF, Elek E, Wagstaff DA, Kulis S, Dustman P. Culturally-grounded substance use prevention: An evaluation of the keepin’ it REAL curriculum. Prevention Science. 2003;4(4):233–248. doi: 10.1023/a:1026016131401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Helm S, Okamoto SK, Medieros H, Chin CIH, Kawano KN, Po‘a-Kekuawela K, Nebre LH, Sele FP. Participatory drug prevention research in rural Hawai‘i with Native Hawaiian middle school students. Progress in Community Health Partnerships: Research, Education, and Action. doi: 10.1353/cpr.0.0042. in press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hishinuma ES, Andrade NN, Johnson RC, McArdle JJ, Miyamoto RH, Nahulu LB, et al. Psychometric properties of the Hawaiian Culture Scale-Adolescent Version. Psychological Assessment. 2000;12(2):140–157. doi: 10.1037//1040-3590.12.2.140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huriwai T. Re-enculturation: Culturally congruent interventions for Maori with alcohol-and drug-use-associated problems in New Zealand. Substance Use & Misuse. 2002;37:1259–1268. doi: 10.1081/ja-120004183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson RC, Nagoshi CT, Ahern FM, Wilson JR, Yuen SLH. Cultural factors as explanations for ethnic group differences in alcohol use in Hawaii. Journal of Psychoactive Drugs. 1987;19:67–75. doi: 10.1080/02791072.1987.10472381. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kanahele GHS. Ku Kanaka, stand tall: A search for Hawaiian values. Honolulu: University of Hawai‘i Press; 1986. [Google Scholar]

- Kulis S, Marsiglia FF, Elek E, Dustman P, Wagstaff DA, Hecht M. Mexican/Mexican American adolescents and keepin’ it Real: An evidence-based substance use prevention program. Children and Schools. 2005;27(3):133–145. doi: 10.1093/cs/27.3.133. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lai M, Saka S. Hawaiian students compared with non-Hawaiian students on the 2003 Hawaii Youth Risk Behavior Survey. 2005 Retrieved April 14, 2008 from http://www.ksbe.edu/spi/PDFS/Reports/Demography_Well-being/yrbs/

- Matsuoka JK. How changes in the Pacific/Asian region are shaping social work education and practice in Hawai‘i. Social Work. 2007;52(3):197–199. doi: 10.1093/sw/52.3.197. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCubbin LD. Resilience among Native Hawaiian adolescents: Ethnic Identity, psychological distress and well-being. University of Wisconsin; Madison: 2003. Unpublished doctoral dissertation. [Google Scholar]

- McCubbin LD, Ishikawa M, McCubbin HI. Kanaka Maoli: Native Hawaiians and their testimony of trauma and resilience. In: Marsella AJ, Johnson JL, Watson P, Gryczynski J, editors. Ethnocultural perspectives on disaster and trauma: Foundations, issues and applications. Springer; New York, NY: 2007. pp. 271–298. [Google Scholar]

- McGregor DP. Nā Kua‘āina: Living Hawaiian culture. Honolulu: University of Hawai‘I Press; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Miike L. Health and related services for Native Hawaiian adolescents. In: Kagawa-Singer M, Katz PA, Taylor DA, Vanderryn JHM, editors. Health issues for minority adolescents. Lincoln, NE: University of Nebraska Press; 1996. pp. 168–187. [Google Scholar]

- Moran JR, Bussey M. Results of an alcohol prevention program with urban American Indian youth. Child and Adolescent Social Work Journal. 2007;24(1):1–21. [Google Scholar]

- Morgan DL. Focus groups. Annual Review of Sociology. 1996;22:129–152. [Google Scholar]

- Morgan DL. Focus groups as qualitative research. 2. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Napoli M, Marsiglia FF, Kulis S. Sense of belonging in school as a protective factor against drug abuse among Native American urban adolescents. Journal of Social Work Practice in the Addictions. 2003;3(2):25–41. doi: 10.1300/J160v03n02_03. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nicols RL. Native American survival in an integrationist society. Journal of American Ethnic History. 1990–1991;10:87–93. [Google Scholar]

- Oetting ER, Donnermeyer JF, Trimble JE, Beauvais F. Primary socialization theory: Culture, ethnicity, and cultural identification. The links between culture and substance use. IV. Substance Use & Misuse. 1998;33(10):2075–2107. doi: 10.3109/10826089809069817. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pukui MK, Haertig EW, Lee CA. Nana I Ke Kumu: Look to the Source. Honolulu: Hui Hanai; 1972. [Google Scholar]

- Ramisetty-Mikler S, Caetano R, Goebert D, Nishimura S. Ethnic variation in drinking, drug use, and sexual behavior among adolescents in Hawaii. Journal of School Health. 2004;74:16–22. doi: 10.1111/j.1746-1561.2004.tb06596.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rehuher D, Hiramatsu T, Helm S. Nationally endorsed evidence-based youth drug prevention: A critique with implications for practice-based contextually relevant prevention in Hawai‘i. Hawai‘i: Journal of Public Health; in press. [Google Scholar]

- Rezentes WC. Nā Mea Hawai‘i: A Hawaiian acculturation scale. Psychological Reports. 1993;73:383–393. [Google Scholar]

- Ringwalt C, Bliss K. The cultural tailoring of a substance use prevention curriculum for American Indian youth. Journal of Drug Education. 2006;36(2):159–177. doi: 10.2190/369L-9JJ9-81FG-VUGV. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schinke SP, Tepavac L, Cole KC. Preventing substance use among Native American Youth: Three-year results. Addictive Behaviors. 2000;25:387–397. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4603(99)00071-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Strauss A, Corbin J. Basics of Qualitative Research. Newbury Park, CA: Sage Publications; 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Streltzer J, Rezentes WC, Arakaki M. Does acculturation influence psychosocial adaptation and well being in Native Hawaiians? International Journal of Social Psychiatry. 1996;42(1):28–37. doi: 10.1177/002076409604200104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weitzman EA. Software and qualitative research. In: Denzin NK, Lincoln YS, editors. Handbook of qualitative research. 2. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Withy K, Andaya JM, Mikami JS, Yamada S. Assessing health disparities in rural Hawaii using the Hoshin facilitation method. The Journal of Rural Health. 2007;23(1):84–88. doi: 10.1111/j.1748-0361.2006.00072.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wong MM, Klingle RS, Price RK. Alcohol, tobacco, and other drug use among Asian American and Pacific Islander adolescents in California and Hawaii. Addictive Behaviors. 2004;29:127–141. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4603(03)00079-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yuen NC, Nahulu LB, Hishinuma ES, Miyamoto RH. Cultural identification and attempted suicide in Native Hawaiian adolescents. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry. 2000;39:360–267. doi: 10.1097/00004583-200003000-00019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zeller RA. Focus group research on sensitive topics: Setting the agenda without setting the agenda. In: Morgan DL, editor. Successful focus groups: Advancing the state of the art. Newbury Park, CA: Sage; 1993. pp. 167–183. [Google Scholar]

- Zimmerman MA, Ramirez-Valles J, Washienko KM, Walter B, Dyer S. The development of a measure of enculturation for Native American youth. American Journal of Community Psychology. 1996;24(2):295–310. doi: 10.1007/BF02510403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]