Abstract

Background

High rates of long-term antidepressant prescribing have been identified in the older population.

Aims

To explore the attitudes of older patients and their GPs to taking long-term antidepressant therapy, and their accounts of the influences on long-term antidepressant use.

Design of study

Qualitative study using in-depth semi-structured interviews.

Setting

One primary care trust in North Bradford.

Method

Thirty-six patients aged ≥75 years and 10 GPs were interviewed. Patients were sampled to ensure diversity in age, sex, antidepressant type, and home circumstances.

Results

Participants perceived significant benefits and expressed little apprehension about taking long-term antidepressants, despite being aware of the psychological and social factors involved in onset and persistence of depression. Barriers to discontinuation were identified following four themes: pessimism about the course and curability of depression; negative expectations and experiences of ageing; medicine discontinuation perceived by patients as a threat to stability; and passive (therapeutic momentum) and active (therapeutic maintenance) decisions to accept the continuing need for medication.

Conclusion

There is concern at a public health level about high rates of long-term antidepressant prescribing, but no evidence was found of a drive for change either from the patients or the doctors interviewed. Any apprehension was more than balanced by attitudes and behaviours supporting continuation. These findings will need to be incorporated into the planning of interventions aimed at reducing long-term antidepressant prescribing in older people.

Keywords: antidepressants, prescribing, attitudes

INTRODUCTION

A previous study of antidepressant prescribing in the UK reported high rates of long-term prescribing. For patients aged ≥75 years, 14% were being prescribed an antidepressant, while the rate in those aged <75 years was less than half that (6%).1 Among patients aged ≥75 years prescribed an antidepressant, almost half (48%) had been in receipt of a prescription for more than 2 years. Few patients' records had evidence of medication review or discussion of possible withdrawal.

Depression is common in later life,2,3 but it is not clear why the rates of prescribing, and of long-term prescribing in particular, appear to be so much higher in patients aged ≥75 years.4 Most older patients with depression are managed in primary care by their GP. Guidance regarding the management of depression in the UK is provided by the National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence,5 which recommends withdrawal after 6 months' effective treatment, although long-term treatment may be appropriate if the illness is chronic or relapsing. Not all older patients experience relapsing or chronic depression, and many will experience a favourable prognosis,6 yet long-term prescribing remains high and is related to a small increase in repeat prescribing of antidepressants.7 A possible reason for long-term prescribing may be patients' difficulties (actual or anticipated) with discontinuing antidepressant treatment because of unpleasant withdrawal reactions.8,1

GPs managing late-life depression have articulated several obstacles to its effective management, including a lack of agencies to which they can refer patients, and concerns about their own skills and capabilities.9 GPs and patients may have different goals associated with the long-term treatment of depression. Patients emphasise the value of listening and GPs acknowledge its importance,10 but we know little about how patients or GPs think about treatment with long-term medicines or about the strategies used to manage patients receiving long-term antidepressant therapy.

This study explores the beliefs and behaviours of patients and GPs who have experience of long-term (≥2 years) antidepressant prescription.

METHOD

Design

A qualitative evaluation was undertaken of data derived from interviews with individual patients and GPs.

Participants

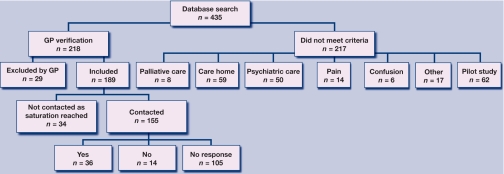

Patients were recruited from eight practices in one primary care trust in north Bradford, an area of mixed housing type and socioeconomic status. The population is predominately white. Potential participants were those aged ≥75 years whose records indicated they had been prescribed an antidepressant continuously for at least the previous 2 years. Potential participants were screened by the GP, who helped identify those patients who would be excluded from the study as a result of: living in a care home; terminal illness; receiving current treatment from a psychiatrist; having significant cognitive impairment; and using antidepressants exclusively to manage pain. Figure 1 shows the numbers recruited to the study.

Figure 1.

Flow chart of recruitment from general practice database search to interview.

How this fits in

High rates of long-term prescribing of antidepressants have been identified in the older population and little is known about the reasons for this. This study demonstrates how older people receiving a prescription for long-term antidepressants attribute positive effects to their treatment, and identifies several barriers to the discontinuation of long-term antidepressant treatment. This suggests there is a role for regular recorded mental health review for patients on long-term antidepressants and this should include a review of patient knowledge, understanding, and concerns about antidepressants.

GPs were recruited after the patient interviews had been conducted, and were doctors whose patients had participated in the study. Fifteen GPs were identified and 10 agreed to be interviewed. Out of five GPs who were not interviewed, one had retired and worked only part-time, therefore had limited mutually available time, as did another two GPs, and two did not give any reason.

Recruitment procedure

GPs wrote to patients meeting the inclusion criteria to inform them of the study. Interested patients sent a reply slip to the researchers, who then arranged an interview date. In total, 155 patients from eight practices were contacted; 23% (36/155) responded positively and were recruited into the sample group. A further 9% (14/155) contacted the researcher or the GP practice to decline involvement and 68% (105/155) did not respond to the invitation letter. Written consent was taken before the interview, which was offered at the patient's home or the practice; all patients chose interview at home.

Patients were purposively sampled to include a mix of the following six variables: antidepressant type (tricyclic; selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor [SSRI]; other); duration of treatment (≥5 years; <5 years); documented medication review (review with change to dosage or antidepressant type; review with no change; no review); indication (depression; anxiety; insomnia; combination); home circumstances (living alone; living with partner/spouse; living with other relatives); and sex. Participant characteristics are summarised in Table 1.

Table 1.

Participant characteristics.

| Patients | GPs | |

|---|---|---|

| n | 36 | 10 |

| Age range, years | 75–91 | 34–60 |

| Females/Males | 26/10 | 6/4 |

| Antidepressant type | 22 tricyclic, 12 SSRI, 2 other antidepressants | n/a |

| Prescription of ≥5 years/<5 years | 22/11 | n/a |

| Self-reported ethnic group | 36 white European | – |

| Habitation | 21 lived alone, 14 lived with partner, 1 lived with son | n/a |

| Indication | 17 depression, 8 anxiety, 9 sleeplessness/insomnia, 2 unclear | n/a |

| Medication review | 13 recorded review with change, 3 recorded review no change, 20 no recorded review or unclear | n/a |

n/a = not applicable. SSRI = selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor.

GPs were approached by letter if they worked at one of the eight practices and a participating patient had named them as their doctor.

Data collection and analysis

Individual semi-structured depth interviews were conducted. See Appendix 1 for topic guides. All interviews were audio recorded and transcribed. Field notes were collected to complement the transcripts; for example, where a participant had made relevant comments after the formal interview. Transcripts were checked for accuracy against audiotapes and further field notes taken, before being imported into NVivo 7. Data were analysed according to framework analysis. Framework analysis was used for its anastomotic processes which explicitly elicit patient experience from large amounts of qualitative data in a systematic manner, while remaining true to patients' descriptions of their lives.11 Three authors were involved in developing the codes and resulting themes. Regular team update meetings were held where findings were discussed and any discrepancies in analysis were resolved by consensus.

RESULTS

Three main themes were identified from the interviews:

the benefits of antidepressants;

ambiguities and dissonances in the understanding of depression and its treatment; and

barriers to the discontinuation of antidepressants.

The benefits of antidepressants

Both patients and GPs talked about the benefits of antidepressants as a means of alleviating distressing symptoms. Patients tended to have few concerns about commencing antidepressant treatment. Several had expected a medication to be prescribed and many were willing to accept any help the GP could provide:

‘At that time [commencement of treatment] I didn't really care! If he'd have said take some rat poison I would have probably taken it, you know, I was that down so I didn't bother; and then gradually … it got better.’ (Patient 33)

Many participants responded positively to antidepressants and attributed their effects to helping alleviate their symptoms and contributing to a return to function:

‘It seemed as if some fairy had waved a wand and got me this [drug] which brought me round. I swear by it.’ (Patient 4)

‘My worst point was when I woke in the morning. I just didn't see any point in going on and it certainly helped very much indeed.’ (Patient 18)

GPs considered antidepressants to be beneficial irrespective of their precise action, placebo or otherwise. They allow the doctor and the patient a feeling of doing something in the face of insolvable problems:

‘If the cause is a social factor I can't get rid of that … but I might alleviate their symptoms a little bit.’ (GP 5)

‘If it makes them feel even a bit better it's worth it. Because at the end of the day a lot of them don't cost a huge amount, they are quite cheap.’ (GP 8)

Ambiguities and dissonances in the understanding of depression and its treatment

The term depression is ambiguous with patients applying different identities to their condition, commonly ‘anxiety’, ‘sleeplessness’, and ‘pain’. Use of vague terms which linked a patient's perception of their condition with their physical health was also common. Several participants attributed their condition to failing physical health, identifying with symptoms such as excessive tiredness. By the same token, patients appeared more at ease treating their condition with a medication than with a social or emotional intervention:

‘After that I started to get tired spells where I was abnormally tired, not sleepy, physically tired … it's an effort to walk about and that was when [the GP] said that this was depression, although I'll say I didn't feel depressed. But as far as I know not being very knowledgeable on medical matters you could be what you call clinically depressed without being mentally depressed. That's how I understand it, so although I didn't feel depressed I accepted the fact that it could well be.’ (Patient 4)

The GPs also acknowledged a difficulty in providing a solid diagnosis of depression and understanding and treating its causes:

‘We have to keep figures of who is depressed, but of course loads of people come in and it says“depressed”, but they are not actually clinically depressed. They are depressed because someone has just died … and that's where our figures have been mucked up … I think for all our patients who have coded as depression, maybe 10%, if that, actually have depression.’ (GP 6)

This ambiguity in understanding depression as an emotional or physical condition influences GPs' views of antidepressants:

‘In emotional medicine you are much more predisposed to the individual patient. In cardiology where essentially every patient comes into the sausage factory and gets an aspirin and a beta blocker and an ACE inhibitor and they all come out at the other end, you can't do that with the emotional illness.’ (GP 7)

‘Statins, yes I have my concerns about statins. But I suppose the gain from that is more tangible and more … easy to sell. The problem with general practice is that the perception of psychiatric illness is one where it's still not seen necessarily as a biological condition. I happen to believe it is.’ (GP 10)

GPs acknowledged the difficulties in providing treatments other than pharmaceuticals:

‘We have … a 10 to 11 month waiting list here for CBT [cognitive behavioural therapy], by which time the crisis has gone. People come to us in extremis really, they are usually in a very, very distressed, disturbed state.’ (GP 5)

‘The majority of [patients] have lived through the Second World War and they have an antipathy to counselling.’ (GP 1)

‘I think [antidepressants] do have a place, partly because it's not a lot of other things that help mild to moderately depressed elderly, the CBT has got a very limited place. Counselling; its always very difficult to get them to engage, so we are often stuck with just prescribing, so it's a bit “best of a bad bunch” really.’ (GP 4)

Patients often echoed this antipathy to non-drug treatments such as counselling. Although, where available, they were open to social, rather than psychological, interventions tailored to their needs. Overall, while patients often appeared more comfortable accepting a physical cause and intervention for their condition, GPs tended to acknowledge social and emotional causes that required non-drug interventions they could not always provide, and although antidepressants offered a solution to some patient's problems, there appeared to be sense of unease about prescribing a medical intervention for a social cause:

‘The GP said “Well, do you want to go for bereavement counselling?” Well I didn't and I don't because with my faith and my family, I don't need anyone else. He didn't offer anything else, poor lad, what else could he offer? You feel that they're embarrassed about it sometimes. He's only a youngish man … no, I haven't ever spoken to anybody about it really.’ (Patient 11)

‘I've been offered one or two [alternatives] … and I said“Well I'll see”and let them know. In the meantime I've been missing my little walks. I was offered walks from home but they had to close because no funds. I was offered people to come and have conversation with me … no funds; no volunteers and that's the problem whatever I've been offered.’ (Patient 21)

‘Nowadays there is medicalisation of life, really. There are problems that we all have in our life. Some people need to have it turned into a medical problem to make it more valid or something. Rather than say I'm struggling to cope with my divorce or whatever, they come and say I'm depressed.’ (GP 2)

Both GPs and patients noted some dissonance in defining and treating depression in an analogous way to physical illness. While an illness may be easier to understand in physical terms, the subjective nature of depression can make it difficult to manage:

‘I don't think it's right to prescribe something that they don't necessarily need, so we prescribe for social issues, but should we prescribe … lifestyle drugs? I don't think we should … But it's difficult when you can't measure an outcome. If someone has high blood pressure I can measure that and it's a definite.’ (GP 6)

Barriers to discontinuation of antidepressants

Both patients and GPs described barriers to discontinuing antidepressants. Some were explicit and widely acknowledged by the patient, but others were implicit and difficult for the patient to identify and define.

GPs adopted strategies to facilitate discontinuation. For example, pre-warning the patient of the limited duration of prescription, tapering the dose with support, and timing any discontinuation around springtime. However, discontinuation remains a challenge for doctors who feel their persuasive power less effective in getting people off antidepressants than when initiating them. Four main barriers to discontinuation were identified:

pessimism about the course and curability of chronic depression;

negative expectations and experiences relating to ageing;

discontinuation as a threat to stability; and

therapeutic momentum and maintenance as desirable.

Pessimism

Among the patients there were some for whom antidepressant treatment had been extensive and complex; characterised by repeated and multiple prescriptions for antidepressants, anxiolytics and hypnotics, these patients had a lengthy medical history and multiple medical contacts over many years:

‘It's a part of my life really and I've just got to cope with it.’ (Patient 20)

‘I never get really well … where I can do without these things. I've lived on them all my life.’ (Patient 19)

‘I don't think now at my age … I think I'll be on them for the rest of my life because they can't do nothing for me so I think I will be taking them for the rest of my life.’ (Patient 1)

These thoughts were present even when responders understood their condition to be caused by external factors, such as recurrent bereavement or physical ill-health. Patients felt unable to plan to remove obstacles to achieving a better condition and as a result accepted and internalised their condition as inevitable. Medication was seen as a long-term solution; it was better to take antidepressants as they provided some minor benefit. These participants did not envisage a bright future, instead spoke of ‘plodding on’:

‘He coped with that very well and then was diagnosed with cancer … so that was a big shock to me … we coped with that very well, got over that. And I think I came off the first antidepressant, or whatever they call them … and then 2000 my eldest son was diagnosed with cancer so they put me back on them again … and he died in June 2001 but that was expected, I coped with that quite well, and after a while came off the antidepressants; and then 2003 my youngest son collapsed and died … so my GP put me back on them again …‘ (Patient 5)

‘I'm normally tired and now you see my situation, my wife should have had her hip replacement but her blood pressure is far too high and she can't have it. So it can only get worse so for the last few years I've had to take on more and more to help her like I've had to do all the shopping and … it doesn't bug me and … physically nor emotionally I just do and … we just accept it, it's just another thing that's come over that we have to cope with …‘ (Patient 21)

Patients acknowledged that often this was also a challenge for their doctor:

‘Oh I have done very well with this [recent reduction to antidepressant regimen], in fact I have done better with these people than I have ever done. With the other people, well I think they were just … I don't think they knew what to give me … I mean more than once I've been told “just get on with you” you know. I do get on with it but it can be very debilitating.’ (Patient 19)

GPs also acknowledged the intractability of some patient's situations:

‘I think they have horrible lives, a lot of them … I think it's a combination of all things, their health, their social circumstances … I think a lot of people are on antidepressants because of everything put together. And you can't … change most of the factors that cause it.’ (GP 8)

For others it validates the illness and sends a message to the family. It is the least a patient can do to be seen to be managing their illness:

‘They feel that unless they are on a tablet for it then they are not having any treatment. There are a lot of those kinds of people.’ (GP 2)

Negative perceptions of ageing

Responders spoke of negative associations with ageing that influenced their decisions to remain on long-term antidepressants:

‘They didn't say anything about why I was depressed or anything … they just seemed to think it was a general condition for my age.’ (Patient 20)

As the responders aged many felt significant deteriorations in their physical and mental health. Poor health exacerbated their condition and limited their activities of daily living, contributing to low mood and symptoms of depression:

‘With old age every year you sort of get something which as you get older is expected. I mean if my eyes go they go. You see that doesn't bother me, my legs bother me, yes because I can't use them properly. I was a great walker at one time and I can't do that now.’ (Patient 19)

Paradoxically, as old age and ill-health became more integrally associated with depression and its treatment, the latter was less often mentioned in consultations:

‘[Doctors] are more bothered about blood tests, liver tests, breathing operations. No, the depression has gone into the bottom drawer … I think according to the state of my health and what the doctors think about me … I suppose if I brought it up in conversation they would talk about depression, but if there is no need to talk … why not leave it alone!’(Patient 4)

‘I'm summoned to the surgery once a year because of my age, where I have blood tests and urine tests, and a general talk about my health. But I don't think that either the [antidepressant] or the depression has been mentioned in those talks.’ (Patient 17)

Doctors also acknowledged this phenomenon:

‘I think it's well known that depression is often overlooked in the elderly and people who have got physical disabilities and whose life has been significantly impaired by their illness …‘ (GP 2)

‘There are some bigger battles I think out there, than persuading them to stop their [antidepressant treatment].’(GP 8)

The GPs recognised this state of affairs: many older people do not view depression as an orthodox illness, and they have low expectations, expect to be unwell, and do not actively seek help. Consequently depression, remains under-diagnosed and requires greater vigilance from doctors:

‘Elderly people are generally more self effacing, and they don't make demands on us for treatment. They say “oh I know it's old age”, you know, they expect that they are going to feel low because they are old. They have lower expectations of what can be achieved, I think, and they are wary of antidepressants, but I think antidepressants do work in elderly people.’ (GP 9)

‘It's always difficult to assess because there are so many more layers with elderly people, they tell you what they think you want them to say … I think it takes a lot more detective work.’ (GP 4)

Discontinuation as a threat to stability

Participants were asked about their experiences with changing and reducing antidepressant medication. Some patients are willing to accept some degree of change. Many expressed that ‘less is more’ when it comes to medication, but a reluctance to withdraw entirely was common. For many participants reluctance to discontinue was influenced by previous experiences of withdrawing from antidepressants:

‘I'm not coming off these because every time I come off, something else happens; but these, these are more for a panic attack.’ (Patient 5)

‘I sort of take half of one for so long and then I think “oh blow this I'll get rid of it” and then of course I get the collywobbles then.’ (Patient 19)

It was unclear whether these participants were experiencing discontinuation effects, or returning to their previously depressed state, however these participants now accepted antidepressant treatment as a long-term option and plans to withdraw were seen as potentially threatening to their currently stable situation:

‘I still don't know whether I would sleep if I came off them … I don't want to try!’ (Patient 32)

‘When [the GP] was there she said“well, we could get you off them slowly”, and I was in fear of her doing that because I suppose they're a crutch really.’ (Patient 34)

Concerns about disruption to the status quo were also reinforced by negative perceptions of ageing:

‘I'm not being funny but … would it make any different at my age? I mean why bother changing something now?’ (Patient 6)

‘I think at my age I would just think “well carry on as I am with them”. I think it's too late to change now.’ (Patient 20)

If a patient is stable, GPs were also reluctant to disturb the equilibrium:

‘It's scary to stop a medication that's been going for a long time, because you kind of think am I opening a can of worms here, because I don't know what the reasons were for them starting that medication. To explore all that will take, you know, I can't do all that now, I will have to do that at another time.’ (GP 9)

‘They're frightened of coming off, because they don't want to feel like they did initially. And you can understand that.’ (GP 8)

Doctors felt that most patients could be persuaded to discontinue antidepressants but require extra support. In many circumstances it is easier to follow the path of least resistance and let them be. However, if there are genuine concerns then the GPs did not view discontinuation as a challenge they cannot overcome:

‘I don't agree with this treatment, it's not the best thing to do, but at the end of the day it depends whether harm outweighs benefit and is it worth having that major fall out with the patient and if I'm really stuck and I really want them off it I would send them to psychiatry to get someone else to try and do it for me. I've never had to do that.’ (GP 5)

GPs felt many received inadequate or sub-therapeutic doses, used as a ‘crutch’. They expressed some uncertainty regarding the consequences of long-term antidepressant use, but in the absence of evidence of specific adverse effects there was little concern. Doctors appear to be more willing to let patients decide whether or not they should continue on antidepressants. The goal of both doctor and patient appears to be not to ‘rock the boat’:

‘There are some patients who need that little bit of a crutch, almost a placebo effect, the kind of people who sometimes feel they want to be on a low dose more permanently because they feel it keeps them on an even keel.’ (GP 2)

‘The long-term patients generally are on probably sub-therapeutic doses really, how much actual effect it has on their mental health is probably minimal but it gives them psychological support. If somebody did become more symptomatic then we would up the dose.’ (GP 2)

Therapeutic momentum and therapeutic maintenance

Two broad pictures were identified in relation to continuation of antidepressant prescription: a passive situation, or ‘therapeutic momentum’, where the prescribing and taking of a medication becomes a constant, an action neither subject to impetus nor acted on by an outside force, such as change or medication review. A more active situation, where the repeated prescription is based on appraisal of the risks and benefits of continuation, is described as ‘therapeutic maintenance’. When questioned about their antidepressants, patients in the therapeutic momentum group responded with vague answers about both the effectiveness and future expectations of their medication:

‘But I just do. I take them … I just take them thinking well if they do me good …‘ (Patient 23)

Interviewer (I): ‘Do you think you will continue with the medication?’

Patient (P): ‘Oh I think so. I think now I've got to this age anyway that you know I'll just go on.’ (Patient 26)

A small number of participants were completely unaware of the reason for their prescription and when their medical records were checked a specific diagnosis was not recorded and no review ever present.

Several participants accepted antidepressants as a long-term intervention and prior to interview appeared to have given little attention to the reasons why they continued taking them:

‘I don't really know. The doctors will keep an eye on things and if the time was appropriate then they would take me off it but… having kept me on it I assume they are happy for me to go on taking it so I take it but … with all this medication I would come off it if I could. If I can't come off it then I accept it.’ (Patient 21)

The perpetuation of this steady state of therapeutic momentum can be characterised by long-term prescription, passive acceptance of medication, and lack of meaningful review by either doctor or patient.

Other participants made a more conscious decision to continue on a long-term prescription of antidepressants. Their acceptance of the medication as long-term is not passive in the same way as the patients who describe a state of therapeutic momentum. Instead there is a steady state of therapeutic maintenance, an active situation where the prescribing and taking of a medication becomes a constant, subject to informal review, which seeks to maintain the status quo:

‘As I feel now I feel like I'll be taking them for the rest of my life … after 4 years I can't see it improving, as I say it keeps it in check.’ (Patient 1)

This group of participants had considered their expectations of long-term antidepressant medication, attributed some benefit to them, and expected a course of treatment that would maintain the status quo. They had experienced review by their doctor, but had no desire to stop their treatment or expect repeated and frequent review in the future. Acceptance of therapeutic momentum was also reinforced by patients' thoughts on ageing:

‘Well, I won't be here long so I think I'll keep on it ‘til I go.’ (Patient 27)

‘It would be a marvellous thing if you didn't have to take anything at all, but I think that is asking a bit too much at my age. I think you have to have something to help you along.’ (Patient 29)

One patient described how therapeutic maintenance was a desirable situation and how this state was reinforced by the acceptance of his actions by his doctor:

P: ‘I was called in to see the doctor because I think at that time they were a little concerned about what the long-term effects of taking it would be. And we chatted and the doctor said to me “I think you're taking these as a sophisticated sleeping pill, and if that is the case, I've no objection to that”. And I said “Well, they do help me to sleep, that's the reason why I keep taking them”.’

I: ‘How would you feel if the GP had made a suggestion about that?’

P: ‘I would be disappointed. I feel it's one that suits me and I'd be reluctant either to change or stop it.’

I: ‘Would you have any questions for your GP after this interview about the medication?’

P: ‘No, I don't think so. As I say I'm reasonably happy with taking the … well very happy with taking the drug; it seems to be working and unless I suddenly get an attack of depression, I don't think I would mention it to the GP.’ (Patient 17)

DISCUSSION

The value of antidepressant therapy was expressed by both the patients and the GPs interviewed. These views were held despite recognition of the dissonance between social and medical models of depression, and the apparent paradox of subscribing to a largely psychosocial view of cause and persistence while using medication as the main treatment. One frequently cited reason for the favouring of antidepressants was the inadequacy or unavailability of alternative treatments, but it was also clear that when such help was available patients were likely to reject social and psychological interventions in favour of long-term pharmacological solutions.

Barriers to discontinuation are significant. Feelings of pessimism, negative associations with ageing, deteriorating health, and fear of relapse all reinforce a patient's desire to continue using long-term antidepressants. Concerned not to distance their patients, GPs were inclined to perpetuate prescriptions. Neither patients nor GPs had concerns about side effects and this provides little apprehension in the initiation and maintenance of antidepressants. With few concerns about side-effects, relatively small financial costs, and a widespread belief in (at least partial) efficacy, a system was encountered where there is little pressure for change from the current practice of extensive prescription of long-term antidepressant medication to older patients.

Strengths and limitations of the study

The use of in-depth interviews and a multidisciplinary and reflective approach provided strength to the data collection and analysis. Obtaining an accurate patient narrative was difficult on occasions due to limited patient recall.

The purposive approach to sampling aimed to ensure that those who did respond were representative and shared similar characteristics to the typical population, but those who agreed to participate are inherently self-selecting.

Although the study only covered one geographical location in the UK, it did encompass several general practices in a socioeconomically diverse population. The study did not specifically address sex, ethnic, or class differences.

Comparison with existing literature

Previous research into antidepressant use has tended to focus on initiation and reports high levels of aversion and non-adherence.12–15 Contrary to this finding, this study suggests that at least those patients who are on long-term medication have little apprehension in taking antidepressants. As attitudes to antidepressants are not fixed and can change over time, it is possible that any initial apprehension is forgotten as antidepressants become an accepted treatment.16 Long-term users have been identified as reporting more positive effects with antidepressants.17

Similar accounts of dissonance between the medical and social model of depression have been recorded.6,7,18,19 Research examining late-life depression suggests that patients are more comfortable accepting depression and taking antidepressants for a ‘normal’ chronic condition rather than a social or psychiatric condition, hence the predilection to understand the condition in physical terms.18

Barriers to discontinuation, such as fear of withdrawal, discontinuation symptoms, and a lack of alternative treatments have been attested.5,20Research has not previously focused on an older population, thus the influence of attitudes towards ageing have not been widely explored in the context of long-term antidepressant-taking behaviour.

Associations of depression with poor health expectations and ageing are commonly documented.21,22 GPs and patients perceive it an accepted part of ageing to become depressed.23 Late-life depression is viewed as ‘justifiable’ and understandable.9 Low expectations of treatment and therapeutic nihilism have been documented. This notion of nihilism mirrors the pessimism felt by many patients and their low expectations for recovery.

The fear of relapse and withdrawal from antidepressants, in particular SSRIs, are recognised as significant barriers to discontinuation.8 Similarly there is a large body of literature examining the challenges faced with the discontinuation of anxiolytics.24,25 Other barriers, such as those associated with ageing, have been explored here in more detail than previously. It is apparent that negative expectations and experiences of ageing can reinforce perceptions that antidepressants are long-term treatments, and that discontinuation is undesirable.

Implications for future research and clinical practice

This study's results suggest that GPs feel limited when considering alternative treatments for older patients experiencing depression. Older patient's themselves often feel that psychological and social treatments are unsuitable. More research might elicit older patients' views on different social and psychological treatments for the often social problems that contribute to depression.

These results emphasise the difficulties that are likely to be encountered in attempts to discontinue antidepressants that have already been prescribed for a substantial period. Therefore, preventive action is likely to be a more effective strategy for reducing inappropriate long-term prescribing in older patients. Prescribers need to consult with patients to plan an ‘exit strategy’ when considering antidepressant treatment and address patients' understanding about the long-term need for treatment.

In a recent meta-ethnography of patients' experiences of antidepressants, three time points were identified when it was suggested patients may benefit from a practitioner's intervention.26 The three time points (return to function; experience of adverse effects; latency period) would certainly be appropriate times to review and explore a patient's preferences and understanding of long-term antidepressants.

Despite experiencing considerable distress, many of the participants spoke positively about the future. Exploring experiences of depression and recovery and identifying future goals with patients may help to combat the low expectations experienced by many. Prescribers need to be aware that a patient's age need not be a barrier to plans for discontinuation.

Acknowledgments

Thanks are due to all the participants who gave up their time and shared their experiences of depression and to the GPs who agreed to the research being undertaken in their practices and who agreed to interview.

Appendix 1. Topic guides.

Patients

Introduction

I am doing some research looking at long-term prescribing of medication.

I see you are on ……………………

Can you tell me what this medication is for?

Why did you start taking the medication?

A: Condition

Tell me a bit about your condition:

When did these feelings start?

What was happening in your life at this time?

What brought on these feelings?

Where were you living? Who were you living with?

Any illnesses/losses/life events?

How did you initially cope with these feelings?

Did you ask for any help or advice from others about coping with these feelings?

Did you talk to anybody?

Did you take any alternative treatments?

What type of ways did you try to improve the way you were feeling? Did any of these help?

Have you had depression before?

B: Starting prescription

Tell me a bit about what happened when you first went to the doctors about the condition:

What particular thing made you make an appointment to see a GP about this for the first time?

What did you think the doctor would do?

Can you remember what you asked the doctor?

What did the GP say?

When did the prescription start? How long have you taken this medication?

What did your doctor tell you about your illness?

Can you remember how much time you spent with your doctor?

How long did you think you would be taking the medicine? Can you remember what the doctor said?

Did you think you would take a course of medication like you would with say, antibiotics?

B1: Continuing prescription

What happened to your nerves after taking the medication?

Did the medication help?

How long did it take to help?

How did you feel after taking the medication? Did you experience any side effects?

Did anything else happen to make you feel better or worse? Illness/loss/life events/changes?

Have you always taken the medication as prescribed? Do you take the medication yourself? Do you use a Dosett box? Does a

friend or family member help you with your medication?

Did you discuss your medication with your friends and family? What did they think?

Do you ever get any information about your medication from anywhere else? TV, radio, pharmacy, internet?

Can you remember when the medication was next reviewed? How often?

What happened in the review? Medication increased? Stayed the same? Changed to another antidepressant? Do you know why?

Was this the GP's suggestion? Did you suggest this to the GP?

Have your friends and family given any advice about taking your medication?

C: Period of no change

Does the doctor ever talk to you about your medication?

Have they ever changed your medication? Who suggested this? Doctor, family member, you?

At any time was it suggested that the antidepressant be slowly reduced and then stopped? Was there a plan?

How did you feel when the dose was reduced?

What stops you coming off the medication?

How do feel about your medication? Are you satisfied with it?

Would you have liked anything to be done differently? See your doctor more often? For longer periods? Try a different intervention?

Counselling? Support?

Do you intend on continuing your medication?

Do you feel any apprehension in continuing your medication?

Have you discussed this with your doctor? Have you discussed this with friends and family?

D: Contact with GP

Since being on this medication how often have you seen your doctor about any health related issue?

And how often have you seen your doctor about this specific medication and the condition it treats?

How satisfied are you with the treatment you have received for this condition?

Any questions?

Thank you and close

GPs

General

In all GP practices there are many patients who have taken antidepressants for more than 2 years without being withdrawn. We are doing research into long-term antidepressant prescribing and would like to know more about how patients are started on antidepressants and how decisions are made about whether to continue patients on medication or whether to withdraw them.

When you see a patient on long-term antidepressants how do you assess their continuing need?

Tell me about your experience of stopping antidepressants in patients on long-term treatment.

What do you see as the risks of stopping long-term treatment?

What do you see as the benefits of stopping long-term treatment?

How do you feel about withdrawing antidepressants that have been started by psychiatrists?

Is this different from how you feel about stopping antidepressants started by yourself?

How do patients tend to react to suggestions that you may withdraw long-term antidepressants?

Do you sometimes regret withdrawing long-term treatment?

How do you decide whether to attempt withdrawal of long-term antidepressants?

Could you guess how often patients who stop long-term antidepressants end up going back on them?

Patient-specific questions

Can you easily tell from the records why this patient started on antidepressants?

Has anyone tried to withdraw this patient's antidepressants?

If so, with what result?

Do you plan now to withdraw?

Why?/Why not?

In a patient like this, whose role should it be to consider continuing/withdrawing long-term antidepressants?

Thank you and close

Funding body

The study was funded by Department of Health Priorities and Needs funding from Leeds Mental Health Trust and YReN.

Ethics committee

Ethical approval was granted by Bradford Research Ethics Committee (reference 06/Q1202/112).

Competing interests

The authors have stated that there are none.

Discuss this article

Contribute and read comments about this article on the Discussion Forum: http://www.rcgp.org.uk/bjgp-discuss

REFERENCES

- 1.Petty D, House A, Knapp P, et al. Prevalence, duration and indications for prescribing of antidepressants in primary care. Age Ageing. 2006;35(5):523–526. doi: 10.1093/ageing/afl023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Beekman AT, Copeland JR, Prince MJ. Review of community prevalence of depression in later life. Br J Psychiatry. 1999;174:307–311. doi: 10.1192/bjp.174.4.307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Meltzer H, Gill B, Petticrew M, et al. Office of Population Census and Surveys (OPCS). Surveys of psychiatric morbidity in Great Britain report 1: The prevalence of psychiatric morbidity amongst adults living in private households. London: HMSO; 1995. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Percudani M, Barbui C, Fortino, et al. Antidepressant drug prescribing among elderly subjects: population based study. Int J Geri Psych. 2005;20(2):113–118. doi: 10.1002/gps.1259. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence. Depression: management of depression in primary and secondary care — NICE guideline December 2004. London: NICE; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Henderson A, Korten P, Jacomb P, et al. The course of depression in the elderly: a longitudinal community-based study in Australia. Psych Med. 1997;27(1):119–129. doi: 10.1017/s0033291796004199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Moore M, Ming Yuen H, Dunn N, et al. Explaining the rise in antidepressant prescribing: a descriptive study using the general practice research database. BMJ. 2009;399:b3999. doi: 10.1136/bmj.b3999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Leydon GM, Rodgers L, Kendrick T. A qualitative study of patient views on discontinuing long-term selective reuptake inhibitors. Fam Pract. 2007;24(6):570–575. doi: 10.1093/fampra/cmm069. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Burroughs H, Lovell K, Morely M, et al. ‘Justifiable depression’: how primary care professionals and patients view late-life depression? A qualitative study. Fam Pract. 2006;23(3):369–377. doi: 10.1093/fampra/cmi115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Johnston O, Kumar K, Kendall K, et al. Qualitative study of depression management in primary care: GP and patient goals, and the value of listening. Br J Gen Pract. 2007;57(544):872–879. doi: 10.3399/096016407782318026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ritchie J, Spencer L. Qualitative data analysis for applied policy research. In: Bryman A, Burgess R, editors. Analysing qualitative data. London: Routledge; 2000. pp. 173–194. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Givens J, Datto C, Ruckdeschel K, et al. Older patients' aversion to antidepressants: a qualitative study. J Gen Intern Med. 2006;21(2):146–151. doi: 10.1111/j.1525-1497.2005.00296.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Aikens J, Nease D, Nau D, et al. Adherence to maintenance-phase antidepressant medication as a function of patient beliefs about medication. Ann Fam Med. 2005;3(1):23–30. doi: 10.1370/afm.238. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sirey JS, Bruce ML, Alexopoulos GS, et al. Stigma as a barrier to recovery: perceived stigma and patient-rated severity of illness as predictors of antidepressant drug adherence. Psychiatr Serv. 2001;52(12):1615–1620. doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.52.12.1615. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Maidment R, Liningston G, Katona C. ‘Just keep taking the tablets’: adherence to antidepressant treatment in older people in primary care. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2002;17(8):752–757. doi: 10.1002/gps.688. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Grime J, Pollock K. Patients' ambivalence about taking antidepressants: a qualitative study. Pharm J. 2003;271:516–519. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Clifford S, Barber N, Horne R. Understanding different beliefs held by adherers, unintentional adherers and intentional adherers: application of the Necessity-Concerns Framework. J Psychosom Res. 2008;64(1):41–46. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychores.2007.05.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Rogers A, May C, Oliver Experiencing depression, experiencing the depressed: the separate world of patient and doctors. J Ment Health. 2001;10(3):317–333. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Conford C, Hill A, Reilly J. How do patients with depressive symptoms view their condition: a qualitative study? Fam Pract. 2001;24(4):358–364. doi: 10.1093/fampra/cmm032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lassare A, Younès N, Blanchon T, et al. Psychotropic drug use among older people in general practice: discrepancies between opinion and practice. Br J Gen Pract. 2010 doi: 10.3399/bjgp10X483922. DOI: 10.3399/bjgp10X483922. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Bond J, Peace S, Dittmann-Kohli F, Westerhof G. Ageing in society: European perspectives on gerontology. 3rd edn. London: Sage Publications; 2007. p. 236. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Birren J, Schaie K, Abeles RP. Handbook of the psychology of aging. 6th edn. San Diego, CA: Academic Press; 2006. p. 387. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Sarkisan C, et al. Do older adults expect to age successfully? The association between expectations regarding ageing and beliefs regarding healthcare seeking among older adults. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2002;50(11):1837–1843. doi: 10.1046/j.1532-5415.2002.50513.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Cook J, Biyanova T, Masci C, Coyne J. Older patient perspectives on long-term anxiolytic benzodiazepine use and discontinuation: a qualitative study. J Gen Intern Med. 2007;22(8):1094–1100. doi: 10.1007/s11606-007-0205-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Cook J, Marshall R, Masci C, Coyne J. Physicians' perspectives on prescribing benzodiazepines for older adults: a qualitative study. J Gen Intern Med. 2007;22(8):303–307. doi: 10.1007/s11606-006-0021-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Malpass A, Shaw A, Sharp D, et al. ‘Medication career’ or ‘Moral career’? The two sides of managing antidepressants: a meta-ethnography of patients' experience of antidepressants. Soc Sci Med. 2009;68(1):154–168. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2008.09.068. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]