Developmental interventions are programmatic efforts to influence change in specifically targeted developmental-behavioral processes and thereby alter the developmental trajectories of individuals or groups. Briefly stated, developmental interventions are developmental to the degree that they define individual behavior as a product of organism-context interactions over time, account for the organizational balance between risk and vulnerability factors on one hand and protective and resiliency factors on the other in developmental change, and assess the full profile of adaptive and maladaptive responses to developmental challenges at various life stages (Shirk, 1999). They are interventions to the degree that they promote change from an established or projected developmental pathway toward a more developmentally competent proximal or distal outcome (Ramey and Ramey, 1998).

Developmental interventions can be categorized according to three fundamental intervention goals. Developmental health promotion focuses on facilitating positive outcomes in normative developmental achievement across the life span (Zeldin, 2000). These interventions work by providing social environments that afford task performance or mastery and stimulate existing developmental competencies. Preventive intervention aims to prevent or delay the onset of psychological distress and mental health problems for all members of a given population (universal preventions), members who have empirically established risk characteristics (selective preventions), or members who exhibit subclinical symptoms of a psychological disorder (indicated preventions) (Mrazek and Haggerty, 1994). Treatment intervention focuses on ameliorating symptoms and enhancing ; coping in individuals who experience significant psychological distress or exhibit behavioral symptoms that meet diagnostic criteria for mental health disorder (American Psychiatric Association, 1994).

The Role of Process Research: Developing Developmental Interventions

Assessing program effectiveness is an essential activity of developmental intervention research. However, studies have focused primarily on the front end of evaluation, participant recruitment and baseline assessment, and on the back end, outcome effects and follow-up assessment (Shonkoff, 2000). As a result, there is a significant dearth of empirical knowledge in the middle ground—program implementation and the immediate impact of programs on participants. The assessment of what occurs during the course of implementing a program is generally known as process evaluation. Process evaluations ask not whether but how programs produce effects (Judd and Kenny, 1981; Scheier, 1994). Note that process research can also be used to develop and pilot intervention programs or program components prior to formally implementing them. This kind of process research is often called formative evaluation (Scheier, 1994).

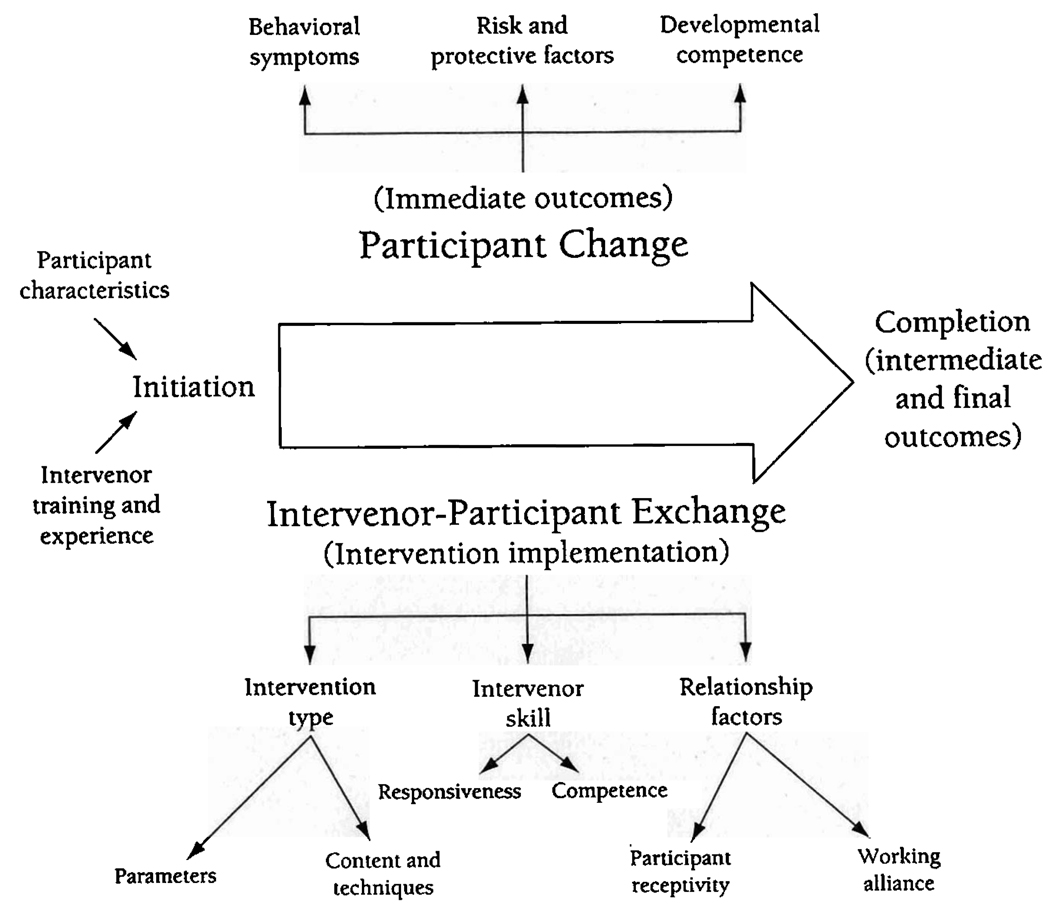

Psychotherapy is one intervention field with a long tradition of research interest in intervention process (Orlinsky, Grawe, and Parks, 1993). The main scientific lessons to be learned from psychotherapy’s experiences with process research fall into two rough categories: method and utility. With regard to method, a schematic summary of developmental intervention process is presented in Figure 6.1. The intervention process is considered to be a collateral endeavor consisting of two interwoven elements: participant change and intervenor-participant exchange (see also Orlinsky, Grawe, and Parks, 1993).

Figure 6.1.

Collateral Elements of Developmental Intervention Process

Participant change refers to the developmental course of participant functioning in one or more behavioral areas during program delivery. Evaluation of participant change might occur at any point during the program, and immediate program impact can be measured within a single meeting or between two or more meetings. Intervenor-participant exchange refers to those aspects of intervention whereby the intervenor interacts directly with the participant in delivering the program. Note that this schematic of intervention process applies only to programs that entail personal delivery of intervention services—that is, to programs that use an intervenor or group of intervenors. It is therefore not applicable to programs that rely exclusively on videotaped protocols, direct mailings, bibliotherapy techniques, and the like. For heuristic purposes, this element of intervention process can be divided into three components: intervention type, intervenor skill, and relationship factors (see also Kazdin, 1993). Intervention type comprises both intervention parameters and intervention content and techniques. Intervenor skill includes responsiveness to participant behavior and competence in executing program goals. Finally, relationship factors include the broad spectrum of interpersonal interactions between intervenor and participant, especially participant receptivity and working alliance.

Process research is aimed at linking aspects of intervenor-participant exchange to targeted participant change both during the program and following its completion. Thus the ultimate utility of process research derives from its multifaceted role in assessing the immediate and cumulative impact of program implementation on developmental changes in participants. Process questions can yield answers that inform a host of issues related to program effectiveness, including intervenor training, mechanisms of program impact, intervenor and participant behaviors that shape outcome, and participant characteristics that predict differential responses. The common thread that binds these various functions of process research is intervention development (Gaston and Gagnon, 1996; Kazdin, 1993). By providing local (that is, program-specific) evidence of how an intervention produces its effects (or lack thereof), process research enables program developers to systematically review, critique, and revise key features of the intervention model. Given good process data, a program can only get better.

Adherence Process Research

Adherence process research is a comprehensive evaluation strategy used to examine one component of intervenor-participant exchange: intervention type (parameters, techniques, content). Specifically, adherence process research assesses program integrity—that is, the degree to which a given program is implemented in accordance with essential theoretical and procedural aspects of the intervention model (Hogue, Liddle, and Rowe, 1996). It has three identifying features. First, it uses quantitative measures to investigate the extent to which program parameters and techniques are implemented, including the intensity and frequency of specific intervenor behaviors. Second, it explores both program-specific intervention characteristics—elements of the theoretical model that are essential and perhaps unique—and generic characteristics endorsed by most programs (such as intervenor warmth and openness). Third, it considers how multiple intervenors and participants within a given program differentially influence the overall integrity of program delivery. That is, it considers how model, intervenor, and participant effects individually contribute to intervention process and outcome.

To produce detail-rich adherence process information, resource-intensive methods such as live or videotape observational ratings of program implementation are required. The quantitative nature of the data allows evaluators to link process assessment directly with program outcomes, thereby providing an avenue for investigating which parts of the program were most effective, and why (Gaston and Gagnon, 1996). Such information is critical not only for improving program efficacy but also for facilitating replicability and transportability to other settings and populations (Waltz, Addis, Koerner, and Jacobson, 1993). In short, adherence process evaluation surpasses the basic dichotomous judgment of most integrity checks—Was the program implemented as planned?—in favor of a multivariate assessment of intervention process—What occurred during program implementation?

Contributions of Adherence Process Research to Intervention

We have completed several adherence process studies in the service of theory building with a family-based developmental intervention for antisocial behavior: multidimensional family therapy, or MDFT (Liddle and others, 1992; Liddle and Hogue, 2001). MDFT is a multicomponent treatment for drug-using and conduct-disordered adolescents that works to change within-family interactions as well as interactions between the family and relevant social systems. MDFT is a highly flexible model that creates individualized treatment plans for each family, and it incorporates basic developmental research on adaptive versus maladaptive adolescent and family functioning into treatment planning designed to reduce or eliminate behavioral problems, repair family attachments, and foster a more prosocial developmental trajectory.

We first conducted adherence process research on the MDFT model for the purposes of model verification and calibration. Hogue and others (1998) compared intervention techniques exhibited by MDFT therapists to those exhibited by therapists practicing individual-based cognitive-behavioral therapy (CBT) during a randomized treatment study of adolescent substance abusers in outpatient treatment. The purposes of the adherence analyses were to verify treatment integrity and differentiation within the larger study and to discover what patterns of intervention techniques were emphasized by each set of therapists in the course of implementing flexible, multimodule treatments with a traditionally difficult-to-serve population.

Naive raters observed ninety videotaped therapy sessions across both models using an adherence process measure that tracks three kinds of therapist techniques: those uniquely endorsed by one of the models (level 1), those jointly endorsed by both models (level 2), and those commonly endorsed by most psychotherapies (level 3). We found that MDFT therapists reliably used the core systemic interventions uniquely prescribed by their governing model (level 1): shaping parenting skills, preparing for and coaching multiparticipant interactions in session, and targeting multiple family members for change. Also, MDFT therapists evidenced few individual differences in adherence. These results verified treatment fidelity within the MDFT condition.

In addition, we found that MDFT therapists employed certain jointly endorsed techniques to a significantly greater degree than their CBT counterparts (levels 2 and 3): establishing a supportive therapeutic environment, encouraging the expression of affect in session, engaging participants in setting a collaborative treatment agenda, and exploring themes related to normative adolescent development. Counter to expectations, family therapists were less likely to explore the details and ramifications of the adolescent's drug use behavior (level 2). These findings helped reshape our understanding of MDFT as an integrative model that works primarily in the attachment and affective domain. They also compelled us to consider the theoretical profits and hazards of comparatively underemphasizing drug use behaviors in favor of concentration on relationship issues. MDFT has since been revised to include directives for incorporating content related to current drug use behavior, as assessed by both self-disclosure and urine screens, into treatment sessions at regular intervals (Liddle, 2000).

We next used adherence process methods in the service of model specification. We adapted MDFT for use in a prevention context with young adolescents at risk for developing substance use and externalizing problems (Hogue, Liddle, and Becker, 2002; Liddle and Hogue, 2000). During the initial model-building phase of converting MDFT into a preventive intervention multidimensional family prevention (MDFP), we delineated a foundation of MDFT goals and techniques that would also anchor MDFP. In addition, we specified some intervention characteristics to be featured more strongly in MDFP than in MDFT, given the younger age range (eleven to fourteen years) and nonclinical status of the target population.

A total of 110 MDFP, MDFT, and CBT sessions were reviewed by a second group of observational raters (Hogue, Johnson-Leckrone, and Liddle, 1999). MDFP counselors were similar to MDFT therapists, and different from CBT therapists, in their use of signature techniques of multidimensional family intervention, such as encouraging the expression of affect and coaching family interactions in session. In addition, MDFP placed the greatest emphasis on enhancing family attachments and communication skills. Contrary to predictions, MDFP counselors were less likely than MDFT therapists to engage in many interventions that we had identified a priori to be primarily preventive in nature: discussing parental monitoring, helping families adopt a future orientation, and encouraging parents to become involved in the extrafamilial activities of their adolescents. In addition, a process examination of MDFP intervention parameters revealed that, in violation of their family-based practice guidelines, MDFP counselors spent as much time in sessions working alone with the adolescents as they did working with parents alone or with parent-adolescent dyads (Singer and Hogue, 2000). These findings underscore particular areas in which the MDFP model, and its training and supervision procedures, should be further articulated to serve high-risk prevention rather than clinical treatment populations.

A third adherence process study (Hogue, Samuolis, Dauber, and Liddle, 2000) was designed to explore process-outcome effects within the MDFT and CBT models. Outcome analyses from the randomized trial comparing MDFT and CBT found that the treatments produced equally successful outcomes at program completion in two critical domains of adolescent functioning: decrease in substance use, and decrease in externalizing behavior (Liddle, Turner, Tejeda, and Dakof, 2000). We then selected fifty sessions (twenty-six MDFT, twenty-four CBT) and identified two underlying process dimensions that captured both therapist technique and session content: family focus (for example, targeting family members for change, working on parental monitoring and family communication, focus on family issues) and adolescent focus (for example, building a working alliance with the adolescent, focus on peer issues, focus on drug use).

No process-outcome links were found for adolescent drug use behavior. However, across the two treatment conditions, level of family focus and level of adolescent focus each predicted outcome in externalizing behavior. Greater use of family-focused interventions predicted fewer conduct problems at posttreatment; in contrast, greater use of adolescent-focused interventions was associated with elevated conduct problems. These contrasting main effects for treatment process suggest that adolescents profited from more emphasis on family-based work and less emphasis on individual-based work. Follow-up analyses found no between-model differences for the negative effects of adolescent focus. However, the two models did receive substantively different benefits for use of family-focused techniques. Surprisingly, it was adolescents in CBT who were helped by greater inclusion of family techniques and issues in therapy; within MDFT, family focus did not predict externalizing outcomes. The overall implications for intervention development appear to be that, on balance, family-centered strategies are preferable to adolescent-centered strategies in reducing antisocial behavior in this population, and therapists applying individual-based models are well advised to integrate family themes into their treatment planning.

Conclusion

Developmental interventions can be greatly enhanced by rigorous evaluation of program implementation and of the diverse intervention processes by which programs achieve their effects. Adherence process research is a flexible methodological tool for assessing the nature and impact of intervention parameters, content areas, and techniques. As such, it plays a central role in the intervention development cycle that follows a course from theory development and program standardization through intervenor training and supervision to program delivery, and finally to evaluation of successes, failures, and surprises in implementing essential program elements.

Acknowledgments

Preparation of this chapter was supported in part by a grant from the National Institute on Drug Abuse (R03 DA12993). The author thanks Leyla Faw for her assistance in preparing the manuscript.

Footnotes

A framework and some practical examples are presented for using rigorous implementation research to inform program outcomes and foster program development for developmental interventions.

References

- American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders. 4th ed. Washington, D.C: American Psychiatric Association; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Gaston L, Gagnon R. The Role of Process Research in Manual Development. Clinical Psychology: Science and Practice. 1996;3:13–24. [Google Scholar]

- Hogue A, Johnson-Leckrone J, Liddle HA. Treatment Fidelity Process Research on a Family-Based, Ecological Preventive Intervention for Antisocial Behavior in High-Risk Adolescents. Paper presented at the annual meeting of the Society for Prevention Research; New Orleans, La. 1999. Jun, [Google Scholar]

- Hogue A, Liddle HA, Becker D. Multidimensional Family Prevention for At-Risk Adolescents. In: Patterson T, editor. Comprehensive Handbook of Psychotherapy, Vol. 2: Cognitive-Behavioral Approaches. New York: Wiley; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Hogue A, Liddle HA, Rowe C. Treatment Adherence Process Research in Family Therapy: A Rationale and Some Practical Guidelines. Psychotherapy: Theory, Research, Practice, and Training. 1996;33:332–345. [Google Scholar]

- Hogue A, Samuolis J, Dauber S, Liddle H. Dimensions of Family Change in Multidimensional Family Therapy for Adolescent Substance Abuse. Paper presented at the annual conference of the American Psychological Association; Washington. D.C. 2000. Aug., [Google Scholar]

- Hogue A, et al. Treatment Adherence and Differentiation in Individual Versus Family Therapy for Adolescent Substance Abuse. Journal of Counseling Psychology. 1998;45:104–114. [Google Scholar]

- Judd CM, Kenny DA. Process Analysis: Estimating Mediation in Treatment Evaluations. Evaluation Review. 1981;5:602–619. [Google Scholar]

- Kazdin AE. Psychotherapy for Children and Adolescents. In: Bergin A, Garfield S, editors. Handbook of Psychotherapy and Behavior Change. 4th ed. New York: Wiley; 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Liddle HA. Cannabis Youth Treatment (CM) Manual, Vol. 5: Multidimensional Family Therapy Treatment (MDFT) for Adolescent Cannabis Users. Rockville, Md: Center for Substance Abuse Treatment, Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Liddle HA, Hogue A. A Family-Based, Developmental-Ecological Preventive Intervention for High-Risk Adolescents. Journal of Marital and Family Therapy. 2000;26:265–279. doi: 10.1111/j.1752-0606.2000.tb00297.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liddle HA, Hogue A. Multidimensional Family Therapy for Adolescent Substance Abuse. In: Wagner EF, Waldron HB, editors. Innovations in Adolescent Substance Abuse Interventions. New York: Pergamon Press; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Liddle HA, Turner RM, Tejeda MJ, Dakof GA. Treating Adolescent Substance Abuse: A Comparison of Cognitive-Behavioral Therapy and Multidimensional Family Therapy. Paper presented at the annual conference of the American Psychological Association; Washington, D.C. 2000. Aug., [Google Scholar]

- Liddle HA, et al. The Adolescent Module in Multidimensional Family Therapy. In: Lawson G, Lawson A, editors. Adolescent Substance Abuse: Etiology, Treatment, and Prevention. Gaithersburg, Md: Aspen; 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Mrazek PJ, Haggerty RJ, editors. Reducing Risks for Mental Disorders: Frontiers for Preventive Intervention Research. Washington, D.C: National Academies Press; 1994. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Orlinsky D, Grawe K, Parks B. Process and Outcome in Psychotherapy: Noch Einmal. In: Bergin A, Garfield S, editors. Handbook of Psychotherapy and Behavior Change. 4th ed. New York: Wiley; 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Ramey CT, Ramey SL. Early Intervention and Early Experience. American Psychologist. 1998;53:109–120. doi: 10.1037//0003-066x.53.2.109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scheier MA. Designing and Using Process Evaluation. In: Wholey JS, Hatry HP, Newcomer KE, editors. Handbook of Practical Program Evaluation. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Shirk SR. Developmental Therapy. In: SiIverman WK, Ollendick TH, editors. Developmental Issues in the Clinical Treatment of Children. Needham Heights, Mass: Allyn & Bacon; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Shonkoff JP. Science, Policy, and Practice: Three Cultures in Search of a Shared Mission. Child Development. 2000;71:181–187. doi: 10.1111/1467-8624.00132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Singer A, Hogue A. Therapist and Independent Observer Ratings of Therapist Adherence to a Family-Based Prevention Model. Paper presented at the annual meeting of the Society for Psychotherapy Research; Chicago. 2000. Jun, [Google Scholar]

- Waltz J, Addis ME, Koerner K, Jacobson NS. Testing the Integrity of a Psychotherapy Protocol: Assessment of Adherence and Competence. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 1993;61:620–630. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.61.4.620. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zeldin S. Integrating Research and Practice to Understand and Strengthen Communities for Adolescent Development: An Introduction to the Special Issue and Current Issues. Applied Developmental Science. 2000;4:2–10. [Google Scholar]