Abstract

HIV/AIDS is recognized as affecting and being affected by the family. HIV+ women in drug recovery and their families are particularly at risk due to family disruption and stigma. Yet family research with HIV+ adults is hampered by the challenges of defining the family, engaging family members into research, and tracking changes in family composition. In this paper we describe the family context of 144 HIV+ women in drug abuse recovery who are enrolled in a randomized trial of a family intervention to improve medication adherence and reduce relapse. “Family” was defined to include the women’s household members, romantic partners, children and their caregivers, and others identified as a major source of support. The women reported on a total of 651 family members. We describe the family and household networks, romantic partnerships and parenting arrangements of our participants. We also describe the engagement rate of family member enrollment in the research study, and the stability of romantic partnerships, parenting and living arrangements over one year. We conclude with methodological implications for future family-based clinical research with HIV+ adults.

Keywords: HIV/AIDS, family, substance abuse, women

BACKGROUND

HIV/AIDS, Substance Abuse Recovery, and Family

The destructive impact of HIV/AIDS on the family has been well documented (Boyd-Franklin et al., 1995; Pequegnat & Szapocznik, 2002). HIV/AIDS is a “multigenerational family disease” (Owens, 2003) that has been shown to disrupt parental roles (Boland et al., 1992) and mother-child relationships (Kotchick et al., 1997). Family members of persons living with HIV/AIDS (PLWHA) can be both a source of stress as well as support (Owens, 2003), impacting areas such as medication adherence and psychosocial functioning (DiMatteo, 2004; Dunbar-Jacob & Schlenk, 2001), health care utilization (Knowlton et al., 2005), and sexual risk taking (Niccolai et al., 2006).

A disease often related to HIV/AIDS, substance abuse adds a layer of disruption to the family that can influence family relationships and precipitate cut-offs. Women who are dually diagnosed with HIV/AIDS and substance abuse are particularly vulnerable to family disruption, such as loss of custody (Barroso & Sandelowski, 2004; Conners et al., 2004; Knowlton, et al., 2007). While there is a well-established body of research on substance abuse treatment for women (Ashley et al., 2003) and family-focused interventions for adult substance abusers (Copello et al., 2006), this research has not addressed family functioning and family-based treatment for those who are dually diagnosed with substance abuse and HIV/AIDS.

Family Research Methodology Challenges

There is a growing consensus that family-based techniques can help address the needs of PLWHA (Crepaz et al., 2006; Rotheram-Borus et al., 2005; Author 1, 2004). The richness and complexity of the family networks of adult PLWHA include many strengths and represent an opportunity for intervening in the social context of PLWHA and thus helping to alleviate some of the strains experienced by PLWHA and their family members. Nonetheless, there is limited family-focused research on HIV+ adults, due in part to formidable methodological challenges (Pequegnat et al., 2001).

We identify three challenges for family research with PLWHA. The first challenge in conducting family-based research with HIV+ adults is defining and identifying the family unit. Unlike child-focused research where the family is typically defined as the child, the parents/caregivers, and perhaps siblings, there is no standard approach for defining the family when the “identified patient” is an adult (Bor & du Plessis, 1997). The second challenge is engaging family members to participate in family research to achieve maximum impact in intervention research and so that the picture of the family that is obtained is representative of the family as a whole (Pequegnat et al., 2001). The third challenge, at least for intervention research, is tracking changes in family or household composition over time so that the influence of such major structural changes can be accounted for in analyzing outcomes.

Defining the Family Networks for HIV+ Adults

Researchers need a flexible and operational set of criteria for identifying the family of PLWHA, who disproportionately have complex family networks and live in nontraditional households (Bor & du Plessis, 1997). Family members of PLWHA have been defined by their biological or legal relationships as well by the financial, emotional and functional support they provide (Bor & du Plessis, 1997; Knowlton et al., 2005). The National Institute on Mental Health’s (NIMH) Consortium on Family and HIV/AIDS defined families of PLWHA as “networks of mutual commitment” (Pequegnat et al., 2001). In addition to including significant others, biological relatives and extended family members in their definition of family, these researchers urge consideration of the perceived strength, duration and conflict involved in family member relationships.

An additional argument for a flexible definition of family among PLWHA is that ethnic minority groups, which are disproportionately affected by HIV/AIDS, often have extended family or kinship structures that can take myriad forms. For example, the households of African Americans, the ethnic group that is most affected by HIV/AIDS in the US, include multiple heads of household, multigeneration families, “fictive kin”, and informal adoptions (Boyd-Franklin et al., 1995; McAdoo, 2007).

The definition of family for PLWHA should include the family network that is outside of the home. Women in particular are deeply affected by the extended family networks in which they are embedded and in which they play multiple roles, including reciprocal relationships of social support with family members or friends living outside of the household (Boyd-Franklin et al., 1995). Qualitative studies have documented the dual burden experienced by HIV+ women of being both patient and caregiver (Sandelowski & Barroso, 2003; Bunting, 2001, Hackl et al., 1997). Given the prevalence of single-mother households (12% nationally), with higher proportions of this household type found among African Americans (31%) and Hispanics (18%) (Coles, 2006), it is important for family intervention researchers to reach the larger family network which can be a key resource for support and assistance.

Engaging Family Members in Research

It can be very difficult to engage family members of an adult with HIV to enroll in research. Unlike with child-centered research, family members may not feel as deeply affected by or involved in what the index patient is experiencing or may hesitate to intrude in the woman’s business. The woman herself wields a great deal of influence in whether or not her family members become engaged in the research (Author 2, 2003). Further, engagement of family members is complicated by the stigma and accompanying secrecy of HIV/AIDS. In addition to the difficulty of engaging family members there is the methodological complication that the particular subgroup in the family that becomes engaged in the research is likely determined by non-random factors such as family member’s motivation (Townsend, 2007), their levels of stress and coping (Townsend, 2006; Bor et al., 2004), their support for the HIV+ woman, and whether or not they know of the woman’s HIV status (Bor et al., 2004). These difficulties notwithstanding, at the very least, researchers need to know what elements of the family network they are (and are not) reaching in family studies and should take an inventory of the family network beyond those they enroll in a study.

Family Fluidity

Families affected by HIV/AIDS experience fluctuations in family composition that potentially affect all members of the PLWHA’s extended family. In particular, among communities where the epidemic is pervasive, extended family members are called upon, sometimes on an interim basis, to assume parenting roles (Boyd-Franklin, 2003). The issue of family fluidity is particularly relevant in research with populations that are undergoing a developmental milestone or transition, such as those leaving drug abuse treatment. Tracking entries and exits in the household and family is necessary for understanding the fluidity of the family dynamics of PLWHA, and for understanding and accounting for the impact of family fluidity on intervention outcomes. As recognized by the NIMH Consortium on Family and HIV/AIDS, tracking the entries and exits in the family is necessary but also difficult and further study in this area is merited (Pequegnat et al., 2001).

Aims of the Present Study

In this paper we illustrate these three challenges to family research with PLWHA by describing the family context of a sample of HIV+ women in drug recovery who were enrolled in a randomized trial and in a companion family process study. The specific goals of the present study are to describe the: 1) family networks and households of study participants; 2) patterns related to the enrollment of their family members into the study; and 3) changes in partner relationships, child custody and housing arrangements over a one-year follow-up period.

METHODS

Participants

Participants in this study are from a randomized trial to test the efficacy of Structural Ecosystems Therapy (SET; Author 3, 2000; Szapocznik et al., 2004) for improving medication adherence, and reducing relapse and sexual risk behaviors among HIV+ women in drug recovery. To be eligible for the randomized trial, women had to have been HIV-1 seropositive and met criteria for recommending ART (Carpenter et al., 2000), at least 18 years of age, have met the DSM-IV requirements for abuse or dependence on an illegal substance within the last two years (with cocaine as either the primary or secondary drug of abuse), willing to disclose their HIV status to at least one health care professional and to have at least one family member enroll in a companion study examining the family mechanisms of SET. Women were excluded from the randomized trial if they had a DSM-IV diagnosis of current abuse or dependence on an illegal substance within the 30 days prior to study enrollment, were in a phase of institutionalization in which outside contact was prohibited, or had a CD4 cell count of less than 50 (to minimize mortality within the 12 month period of the study). The study was open to English or Spanish-speaking women of all ethnic/racial groups. After the baseline assessment and a four-month long intervention, women were administered follow-up measures at 4, 8, and 12 months.

Of the 174 women who passed the initial study screening, 126 (72.4 %) were enrolled in the randomized trial and were assigned to either SET or an attention control/HIV Health Group. The reasons for failure to randomize included not meeting the study’s inclusion/exclusion criteria (n=29), refusal to continue (n=1), and failing to complete the family assessment within the window period of enrollment (n=18). For the purposes of this paper, we included the women who failed to complete the family assessment on time but were otherwise eligible in the trial, resulting in a sample of 144 women.

The mean age of women in the current sample was 43.3 years (SD=7.3). The majority (81.3%) were non-Hispanic black, 10.4% Hispanic, 6.9% white, and 1.4% identified as “other.” The mean total annual family income (estimated from last IRS report) was $7,413 (25th percentile $0, 75th percentile $10,428). Just under half (47.9%) reported having less than a high school education, 86.1% were unemployed, and 75.0% were on public assistance. Most women (80.6%) had at least one child, 47.2% had children under 18, and 59.7% had children 18 years old or above.

At baseline the mean T-cell count in the sample was 481.3 (SD=305.4) and log HIV viral load of participants was 2.9 (SD=1.3). The mean self-reported number of years since the women were diagnosed with HIV was 9.8 (SD=5.6). Six women did not report when they were first diagnosed with HIV. All women had at least one lifetime DSM–IV substance use diagnosis (WHO, 1997): 93.8% had a diagnosis of cocaine dependence, 69.4% alcohol dependence, 40.3% cannabis dependence, 20.8% opioid dependence, 16.7% sedative dependence, 4.2% cannabis abuse, 10.4% alcohol abuse, 8.3% sedative abuse, 4.2% cocaine abuse, and 4.2% opioid abuse. Most (77.8%) were diagnosed as dependent on more than one substance and 11.1% were diagnosed with abuse of more than one substance.

The interventions in the clinical trial took place over a 4-month period. Measures were assessed with a full battery 4 times at 4 month intervals: baseline, 4, 8, and 12 months. Randomization began immediately after completion of the baseline assessment. Approval was obtained by an Institutional Review Board and all participants provided informed consent for this study. For the parent randomized trial, enrollment, randomization and treatment are now completed but analyses are ongoing, and therefore treatment outcomes are not yet available.

Identifying and Enrolling the Family

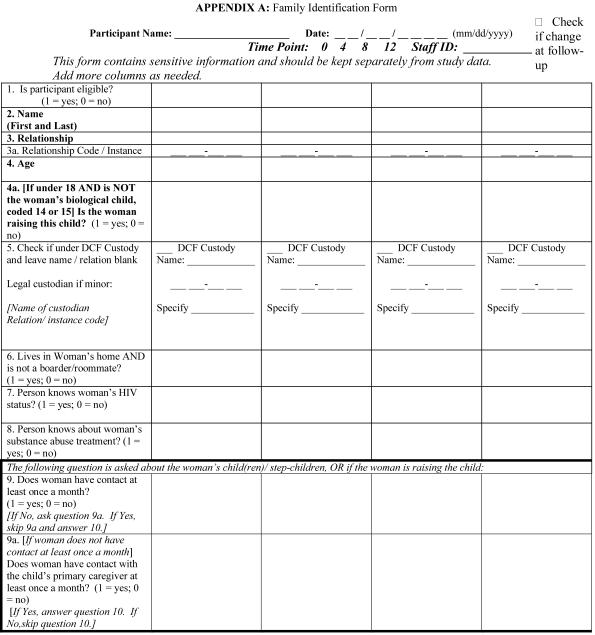

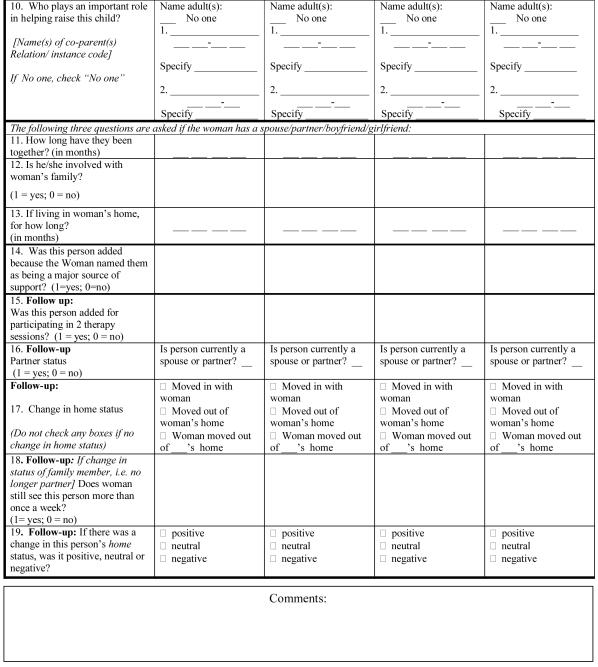

As part of the screening process for family member eligibility for the companion family process study, research associates assessed the membership of the women’s family networks using a Family Identification Form (FIF; see appendix A). Our working definition of family included household members plus others who potentially have either a reciprocal or non-reciprocal influence on the index woman, especially in relation to her health. Our aim was to define the family in a way that was both tractable and allowed us to capture the richness and variety of family constellations among inner city HIV+ women.

The FIF, which is administered to the woman by an interviewer, includes five queries designed to elicit the names of all potential family members, including: 1) all the people in her home; 2) any children who did not live with her; 3) the primary person(s) who helped take care of her children; 4) current spouse, partner, boyfriend or girlfriend; and 5) anyone not yet mentioned who the woman considered a major source of support. Once this list was generated, the interviewer asked a series of questions pertaining to each family member, depending on relationship type. In reference to all family members, the interviewer asked the woman to report age and whether the family member was aware of the woman’s HIV and substance abuse recovery status. In reference to children, the interviewer asked who was the legal custodian of the child, who (if anyone) was helping to raise this child and whether the woman had contact with the child at least once a month. In reference to her partners, the interviewer asked how long the woman and partner had been together and if the partner was involved in family activities. Prior to each follow-up visit (4, 8, and 12 months post-baseline) an interviewer asked the woman if her romantic partnerships had changed and whether or not someone had moved in or out of her household. These FIF follow-up questions were designed to track changes in family/household composition.

All of the family members identified on the FIF were invited to enroll in the family process study, provided that they met eligibility criteria. Among the people identified in FIF, persons living in the home strictly as boarders, casual boyfriend/girlfriends (involved less than 6 months and not cohabitating), children under age 6, wards of the state, children with whom the woman did not have at least monthly contact, and persons who the woman did not want in the study were deemed ineligible for the family study. The women identified 651 family network members through the FIF study screening process. Out of the 651 family members identified via the FIF, 10.8% were ineligible for the family study, leaving 581 eligible family network members. Because we did not expect to succeed in enrolling all eligible family members, we also designed the FIF to provide a representation of the entire family network, including those who did not ultimately enroll in the family process study.

Statistical Analysis

Data were entered into a web-based program developed by study staff and analyzed in STATA 10.0 (College Station, TX 2007). Frequencies were tabulated and descriptive statistics calculated. Bivariate analyses were considered statistically significant if p-values from X2 tests or t-tests were <.05. Household configurations were coded by hand.

RESULTS

Defining and Identifying the Family Unit

Descriptions of the Family Networks

On average, women reported 4.5 (SD=2.7, median=4, IQR=3) family network members, ranging from 1 to 15 members (refer to table 1). Nearly 40% of the network identified by the index women lived in her household. Including herself, women on average lived in a household of 2.8 people (SD=2.0, median=2, IQR=2.5), ranging from 1 to 12 individuals. Just over half of the women (54.2%) reported a current partner and 10.4% were married. One woman reported that her partner was female. Overall, the women’s network was comprised mostly of adults (70.2%), first degree relatives (59.6%), second degree relatives (10.6%), current partners (12.3%), “other” family members (10.3%) and friends (7.2%).

Table 1.

Descriptions of index women’s FIF network and household at baseline, N=144 women

|

Household mean(sd) % (n) |

FIF network mean(sd) % (n) |

% of FIF network enrolleda % (n) |

|

|---|---|---|---|

| Women with current partner (girlfriend, boyfriend or spouse) Women who are married |

37.5 (54/144) 9.7 (14/144) |

54.2 (78/144) 10.4 (15/144) |

|

| Women with any children | 36.1 (52/144) | 80.6 (116/144) | |

| Women with minor children (<18 years old) Mean no. of minor children (of women with minor children) |

22.9 (33/144) 0.9 (1.2), 0-4 |

47.2 (68/144) 2.1 (1.3), 1-7 |

|

| Total no. of minor children | 60 | 143 | 37.2 (35/94) |

| Women with adult children (>17 years old) Mean no. of adult children (of women with adult children) |

18.1 (26/144) 0.4 (0.7), 0-3 |

59.7 (86/144) 1.9 (1.2), 1-6 |

|

| Total number of adult children | 34 | 166 | 24.2 (39/161) |

| Proportion of sample comprised of... | N=257 | N=651 | N=581 |

| Adults | 59.1 (152/257) | 70.2 (457/651) | 38.3 (170/444) |

| First degree relativesb | 45.1 (116/257) | 59.6 (388/651) | 29.0 (96/331) |

| Second degree relativesc | 19.5 (50/257) | 10.6 (69/651) | 45.9 (28/61) |

| Current partners/boyfriend/girlfriend/spouse | 21.4 (55/257) | 12.3 (80/651) | 67.5 (54/80) |

| Friends | 4.7 (12/257) | 7.2 (47/651) | 61.7 (29/47) |

| Other family membersd | 9.3 (24/257) | 10.3 (67/651) | 27.4 (17/62) |

| Total | |||

| Mean size of network (with index woman) | 2.8 (2.0), 1-12 | 5.5 (2.7), 2-16 | |

| Mean size (without index woman) | 1.8 (2.0), 0-11 | 4.5 (2.7), 1-15 | |

| Total number of network | 257 | 651 | 38.6 (224/581) |

Denominator includes only those family members eligible for the family study, so denominators may vary

Includes biological parents, siblings and children

Includes biological grandparents, grandchildren, aunts, uncles, nephews, nieces

Steps, in-laws, exes, church official, god-children, god-parents, god-siblings, “others”

Household Configurations

Two authors (VBM and NWL) employed a qualitative coding methodology to characterize household configurations. Independently of one another, the researchers diagramed the households using symbols similar to a genogram and looked for repetitive patterns among the households. In particular, researchers paid attention to family relationship type, generational status, partner status and other demographic characteristics such as age. The researchers then independently classified the repetitive patterns into family types or configurations. The researchers held multiple meetings to compare their codings and reach consensus on the household types. The most common mutually exclusive household configurations were tabulated and ranked. Nearly half of the women either lived alone (27.8%) or only with their romantic partner (19.4%) (refer to table 2). Fourteen percent of women lived only with children, grandchildren and nephews or nieces. Most of these women were living with minors (80.0%) with the remainder of women living with their adult children. Eleven percent of women lived in “traditional nuclear” families, consisting of a male partner and child(ren) or grandchild(ren).

Table 2.

Index women’s household configurations at baseline, N=144 women

| % (n) | |

|---|---|

| Lives alone | 27.8 (40) |

| Only with partner (spouse, partner, boyfriend or girlfriend) | 19.4 (28) |

| “Traditional” nuclear family (with male partner and child/ren or grandchild/ren) | 11.1 (16) |

| Only with children, grandchildren, nieces, nephews | 13.9 (20) |

| Three-generation household | 9.2 (13) |

| Only with peers | 5.6 (8) |

| Siblings raising child(ren) together | 4.2 (6) |

| Extended family not otherwise categorized | 6.9 (10) |

| Mixed family and friends not otherwise categorized | 2.1 (3) |

|

| |

| Total | 100 (144) |

The remaining 27.8% of the women’s households did not fit neatly into the aforementioned categories. Some women lived in three generation households (9.2%) with most of these women as the middle generation (n=9) and the remainder as the oldest generation (n=4). Other women lived only with peers (5.6%), most of whom lived only with relatives in their own generation (n=5), but some lived only with friends (n=2) or a mixture of friends and family (n=1). Another configuration included siblings raising children together (4.2%). Two percent of women lived in households consisting of both friends and family that could not be otherwise categorized. About seven percent of the sample was categorized as “extended families not otherwise categorized.”

Parenting Arrangements

Of the 68 women with minor children, thirty-five women (51.5%) had custody of at least one of her children. About a third (31.4%) of the women with custody stated that no one was helping them raise their children, 45.7% stated that one person was helping them, and 22.9% stated that 2 people were helping them raise their children (refer to table 3). Viewing this information from the children’s perspective, among the 143 minor children of the index women 42.0% lived with their mother. There were 60 children in their mother’s custody of whom 36.7% were being raised by their mother only, 31.7% had one additional caregiver, and 31.7% had 2 additional caregivers. The co-parents of these children consisted of the woman’s current partner (n=8), the woman’s mother (n=6), the woman’s sister (n=5), the woman’s ex-partner (n=5), the woman’s father (n=2) or another relative (n=4). In addition, 20 women (representing 42 minor children) said that they were helping to raise other people’s children, over half (57.1%) of whom were their grandchildren, 21.4% stepchildren, 19.0% nieces/nephews, and 2.4% god-children.

Table 3.

Parenting status of minor children (<18 year old) at baseline, N=143 children

| All % (n) N=143 |

Ages 0-5 % (n) N=26 |

Ages 6-10 % (n) N=28 |

Ages 11-17 % (n) N=89 |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Children who live with mom | 42.0 (60) | 46.2 (12) | 39.3 (11) | 41.6 (37) |

| Children in mom’s custody | 44.8 (64) | 50.0 (13) | 42.9 (12) | 43.8 (39) |

| Custodians of children not in mom’s custody State Woman’s mother Woman’s ex-partners Woman’s ex-spouse Woman’s ex-boyfriend/girlfriend/partner Woman’s sister Woman’s aunt Woman’s daughter Other family membersb |

N=79a 34.2 (27) 22.8 (18) 15.2 (12) 10.1 (8) 5.1 (4) 3.8 (3) 6.3 (5) 5.1 (4) 8.9 (7) |

N=13 46.2 (6) 23.1 (3) 7.7 (1) 7.7 (1) 0 7.7 (1) 7.7 (1) 0 7.7 (1) |

N=14 42.9 (6) 28.6 (4) 7.1 (1) 0 7.1 (1) 0 14.3 (2) 0 14.3 (2) |

N=50 30.0 (15) 22.0 (11) 20.0 (10) 14.0 (7) 6.0 (3) 4.0 (2) 4.0 (2) 8.0 (4) 8.0 (4) |

Columns don’t add up to 100% due to missing data (n=3)

Other family members include: brother, son, niece, cousin, mother-in-law, sister-in-law, friend, other

Family Enrollment in Research

To determine how many family members ultimately enrolled in the family process study, the proportion of family members who completed baseline consent forms was calculated from the total number of eligible family member participants. Overall, 38.6% (n= 224) of eligible family members enrolled in the family process study. There was a statistically significant difference in enrollment based on whether or not the family member lived with the woman, with 49.4% of eligible household members enrolling compared to only 31.1% of eligible non-household members (p<.0001). There was also a statistically significant difference in family member enrollment based on relationship type with 29.0% of eligible first degree relatives (including parents, siblings and offspring), 45.9% of eligible second degree relatives (including grandparents, grandchildren, uncles, aunts, nieces and nephews), 67.5% of eligible partners, 27.4% of other eligible family members (including steps, in-laws, god-children, god-parents, and god-siblings), and 61.7% of friends identified on the FIF enrolling in the study (refer to table 1).

We examined whether disclosure of the woman’s HIV and drug abuse history had an impact on family members’ enrollment in the study. The majority of persons in the woman’s network were aware of the woman’s status regarding HIV (73.9%) and substance abuse recovery (84.7%) (refer to table 4). Relatively more family members knew about the woman’s being in substance abuse recovery than her HIV status, which was true both for adults (p<.001) and for children ages 6-17 (p<.001). Whether or not family members knew of the women’s HIV status (p=.633) or that she was in substance abuse recovery (p=.560) was not significantly associated with whether or not they enrolled in the family study.

Table 4.

Family member’s knowledge of index woman’s HIV status and substance abuse at baseline, N=651 family members

| HIV status | Substance abuse | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Household members % (n) N=257 |

Non-household members % (n) N=394 |

Household members % (n) N=257 |

Non-household members % (n) N=394 |

|

| All | 67.7 (174) | 77.9 (307) | 80.9 (208) | 87.1 (343) |

| All adults | 87.5 (133) | 87.9 (268) | 96.1 (146) | 97.1 (296) |

| Current partners | 96.4 (53) | 92.0 (23) | 96.4 (53) | 100 (25) |

| Age groups 0-5 years old 6-10 years old 11-17 years old 18-25 years old 26-45 years old 46-64 years old ≥ 65 years old |

0 25.0 (5) 55.4 (36) 83.8 (31) 85.7 (48) 93.2 (41) 86.7 (13) |

0 29.4 (5) 58.6 (34) 86.6 (71) 85.8 (115) 90.4 (66) 100 (16) |

10.0 (2) 55.0 (11) 75.4 (49) 91.9 (34) 98.2 (55) 100 (44) 86.7 (13) |

0 35.3 (6) 70.7 (41) 92.7 (76) 99.3 (133) 97.3 (71) 100 (16) |

Tracking Family and Household Changes

We examined the stability of the family among the 83 women for whom we had FIF data at baseline and 12 months. Of these women, 20.5% were living alone at baseline compared to 24.1% who were living alone at 12 months. Fifty-four percent of women had a partner at baseline (one woman had multiple partners at baseline and was excluded from this analysis, resulting in n=82 for the partner fluidity analyses) and 86.4% of these women were still with the same partner at the end of 12 months. Five women who reported partners at baseline reported an additional partner (while maintaining their original romantic partnership) during the study. Of 31 children who lived with their mother at baseline, 29 lived with her 12 months later. Of 30 children who were not living with their mother at baseline, only one moved in with his/her mother by 12 months later. One woman gained custody of 2 of her 3 children during the 12 month period. No women lost custody of a child during the 12 months of the study. We examined all household changes for 70 women for whom we had FIF data at all four time points. Almost half (48.6%) of the women experienced some change in household composition over the 12 months of the study. Twenty-seven percent of women had at least one household member move in with her, 30.0% had at least one household member move out of her house and 8.6% moved out of the household in which they lived. Of 74 instances of household composition change, 41.9% were described by the women as positive, 9.5% as negative and 48.6% as neutral.

We examined whether family stability was affected by assignment to the intervention conditions in the clinical trial. We did not hypothesize that changes would be significantly affected by intervention because the SET intervention would aim to reinforce existing relationships and structures in some cases and to establish boundaries that might precipitate changes in relationships or household status in other cases. A post hoc analysis of women who experienced partner or household arrangement changes over 12 months revealed no statistically significant difference in women who experienced any change in household composition by treatment type (p=.782). Of the 44 women with partners at baseline, 38 were still with the same partner at 12 months and there was no difference by treatment condition in the number of women stayed with the same partner (p=.685).

DISCUSSION

Descriptive Family Findings

This study describes the family networks in a sample of HIV+ women in drug recovery, which consist of people both inside and outside of the woman’s home, and includes adult members of the extended family and friends. The average household size (2.8) for women and the proportion of households consisting of a person living alone (27.8%) are similar to the U.S. average of 2.6 household members and 26% of persons living alone (Bergman, 2007). The average network size for women was 4.5 which is similar to a study of HIV+ injection drug users (34% of whom were women) in which the average support network was 4.40 (Knowlton et al., 2005). About half of the women had partners, predominantly male, unmarried and cohabiting. These were by and large committed relationships, which had existed for at least 6 months prior to the study and lasted for the one year of follow-up. It should be noted however that this finding regarding relationship stability was among the women who remained in the study for the entire 12 months, a group that probably leads more stable lives than those who dropped out of the research.

We found a mixture of typical and atypical household compositions. A sizable number of women were raising children alone, a subgroup which is doubly burdened with managing their own very challenging medical conditions and caring for children. Some household configurations illustrate structures that are likely to be mutually supportive, particularly around child-rearing, such as sisters raising their respective children together. Similar household arrangements were found by Dorsey et al in their study of both HIV infected and uninfected African American mothers (Dorsey et al., 1999). In their study, roughly half of the women were sole caregivers, approximately a quarter lived with a male partner, and the remaining quarter with other adults. These other adults were mostly female, frequently including the child’s grandmother and/or child’s aunt.

We found some households that if viewed from a distance could be perceived as odd or dysfunctional, such as women living simultaneously with new and ex-partners. However, clinical review of these cases reveals that they provided a supportive context. For example, one woman was taken in by her ex-husband and his new wife and family who were helping the woman to move forward with her drug recovery. Another family consisted of the woman, her physically impaired ex-husband, her young boyfriend, and her daughter and the daughter’s husband and 6 year old daughter. In this case, the index woman was helping to care for her ex-husband who in turn played the role of advisor to the younger members of the family. These observations echo Boyd-Franklin’s suggestion that the litmus test of family function need not be based on what the family composition looks like, but rather on the clarity of the boundaries established within a given family and how well these relationships function within that family structure (Boyd-Franklin, 2003).

Children and Parenting

The findings with regard to minor children vividly show the parenting disruptions that are associated with HIV and substance abuse. The majority of the minors did not live with their mothers and were not in their mother’s custody. Among children not in their mother’s custody, about a third were in the state’s custody. It is impossible to tease out the relative impact of substance abuse and HIV, and for that matter of the other ecological factors of inner-city life that are related to these disruptions in parental functioning. However, a study of over 100 adolescent children of drug and alcohol abusing mothers found no significant differences in rates of family disruption, history of abuse, and mental health problems between the children of HIV infected versus uninfected mothers (Leonard, 2008), suggesting that maternal substance abuse is a particularly disruptive factor.

In their metasynthesis of qualitative studies focusing on women who are dually diagnosed with HIV and substance abuse, Barroso et al. describe several themes related to motherhood: 1) motherhood brings an intensified stigma to the dual diagnosis, 2) regaining custody and bettering relationships with children are strong motivators for drug treatment, and: 3) women express intense feelings of guilt and fear of rejection when faced with reuniting with their children and reestablishing family units (Barroso & Sandelowski, 2004). In light of these challenges, our study found that the family was an important source of parental support both for children out of their mother’s custody and those being raised by their mothers. However, while many women were receiving assistance from family members in raising their children, others were raising their children on their own, and still others helping to raise the children of others.

Methodological Challenges in HIV/AIDS Family Research

This paper illustrates several challenges in conducting family-based research with HIV+ women: 1) defining and identifying the family; 2) engaging family members into research and knowing what parts of the family were missed; and 3) tracking changes in family composition over time. The absence of a standard approach for defining the family and the complexities of measuring family functioning when only part of the family is available and when the composition of the family is itself a moving target seriously complicates behavioral research on family and HIV. Similar concerns were brought up by authors from the NIMH Consortium on Family and HIV/AIDS (Pequegnat et al., 2001) who recognize the paucity of literature on families of PLWHA, the methodological barriers, and the need for instruments tailored for this population.

Defining the Family

Due to the variety of family constellations and the multiple and intersecting roles of women and their family members, family studies with HIV+ women require a set of criteria for delineating the family that allows for both complexity and operationalization. We advocate an approach to defining the family that focuses on those persons who are likely to influence and be influenced by the HIV+ woman’s health and psychosocial functioning, i.e., those who are proximal to the index patient based on roles rather than on biological relationships. We selected our particular set of criteria for defining the family (household members, partners, children, persons helping to raise the children and supportive others) based on our study aims of testing the efficacy of a family intervention for health outcomes (i.e. HIV medication adherence, sexual risk-taking and relapse) and examining reciprocal family processes. The specific criteria used by any particular study will need to be driven by the study’s population, outcomes, predictors, and proposed moderators and mechanisms. For example, our inclusion of persons helping to raise the women’s children is particularly relevant given that we were focused on women age 18 and above in transition subsequent to drug abuse treatment, but would probably not be relevant for a study focused on older women. Further work is needed to perhaps create a set of decision roles for defining inclusion criteria for family research, possibly incorporating considerations suggested by Pequegnat et al (2001) that we did not use in our study, such as conflict and the perceived strength of the relationship.

Engaging Families in Research

Once the family network is defined and identified, researchers who aim to measure family functioning are faced with the challenge of engaging as much of this network as possible. However, as illustrated in this study with an enrollment rate of only 38.6%, even the most diligent recruitment efforts will fall short and researchers can realistically hope to engage only part of the family, rendering an incomplete picture. Moreover, it is likely that this “missingness” of family members will be systematic, such as in our finding regarding different rates of enrollment based on household membership and relationship type. Further, those family members who have the most strained relationship with the index patient, or who shun assessment due to stigma (Sandelowski, et al. 2004) (e.g., substance abusers) are apt to be more difficult to engage.

At the very least, researchers need to have a picture of the composition of the family network pool so that they can report who is missing from their family assessment. Such knowledge can also provide a clue for future studies regarding classes of family members who require special attention with regard to outreach. For example, our relatively low enrollment rates among first-degree relatives highlights the challenge of reaching blood relations and perhaps reflects a prevalence of disengagement from close relatives even when they have an active role in the woman’s life. On the other hand, the strong showing by friends and partners (the majority of whom were unmarried) reflects the relevance of “families of choice” in the lives of HIV+ women (Bor & du Plessis, 1997) and points to the potential of focusing of informal family ties in family research. These differences also have implications for analysis and generalization of findings. Any statistical model that attempts to explore the effect of this “missingness” on study outcomes will require information on those family members who do not engage.

Tracking Family and Household Changes

In longitudinal research, family fluidity, especially entries and exits from the family or the home, is a particularly vexing problem for getting an accurate picture of the family over time. While such physical changes are of interest in and of themselves, they can potentially distort the picture when studying longitudinal effects for family relational factors such as social support or communication. This issue is particularly germane in family research with populations that are experiencing developmental transitions. For some analyses, information on changes in family composition should be incorporated into measurement and analysis strategies. For example, in the current sample we found that nearly half of the women had experienced a change in household composition during the 12 months of the study, a factor that we will have to take into consideration when examining longitudinal effects on relational factors and systemic family-level effects. Child custody, living arrangements, and romantic partners, on the other hand, were relatively stable over the course of the study. Thus we will be able to examine longitudinal changes in mother-child relationships without too much concern that they are over-shadowed by changes in daily physical proximity.

Limitations

The findings from this study need to be interpreted with caution due to some limitations. First, this sample only includes women who at initial screening could identify at least one family member who would be available to enroll in the companion family study, thus this sample may be under-representing the proportion of HIV+ women in drug recovery who are living alone or who have no one to report in their social network. Second, the networks depicted in this study are not an exhaustive census of the women’s family members, only the ones she is actively involved with. Therefore the large proportion of people who know the woman’s HIV status and that she is in substance abuse recovery does not represent the proportion of her relatives who know her status. And, lastly, descriptions of family fluidity may be limited due to low follow-up rates; complete follow-up data were only available for approximately half of our sample (57.6% for partners and children and 48.6% for household composition changes).

Future Research

The findings from this study paint a picture of the family context of urban women who are managing both HIV/AIDS and drug abuse recovery. While this sample illustrates many of the difficulties confronted by these women and their families, it also shows that the women have access to family networks that contain many strengths and that can be the focus of interventions to improve family functioning and supportive resources. Some specific areas for further research suggested by this study include research to support and strengthen parental subsystems for children affected by HIV/AIDS, refinement of methods for identifying and tracking the family, and studies to understand the barriers and facilitators of family member enrollment and retention in research. The challenge for researchers is that the complexity and elasticity of families affected by HIV/AIDS make them a rich focal point for new knowledge and interventions but also renders them difficult to study. Ongoing dialogue and approaches for confronting this dialectic are needed to advance the field of family research of PLWHA.

Appendix

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: The following manuscript is the final accepted manuscript. It has not been subjected to the final copyediting, fact-checking, and proofreading required for formal publication. It is not the definitive, publisher-authenticated version. The American Psychological Association and its Council of Editors disclaim any responsibility or liabilities for errors or omissions of this manuscript version, any version derived from this manuscript by NIH, or other third parties. The published version is available at www.apa.org/pubs/journals/fsh.

Contributor Information

Victoria B. Mitrani, University of Miami

Nomi S. Weiss-Laxer, University of Miami

Christina E. Ow, University of Miami

Myron J. Burns, Nevada State College

Samantha Ross, University of Miami.

Daniel J. Feaster, University of Miami

REFERENCES

- Ashley OS, Mardsen ME, Brady TM. Effectiveness of substance abuse treatment programming for women: A review. The American Journal of Drug and Alcohol Abuse. 2003;29(1):19–53. doi: 10.1081/ada-120018838. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barroso J, Sandelowski M. Substance abuse in HIV-positive women. Journal of the Association of Nurses in AIDS Care. 2004;15(5):48–59. doi: 10.1177/1055329004269086. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bergman M. Single-parent households showed little variation since 1994, Census Bureau reports. U.S. Census Bureau News; Washington, D.C.: 2007. U.S. Department of Commerce. [Google Scholar]

- Boland MG, Czarniecki L, Haiken HJ. Coordinated care for children with HIV infection. In: Stuber, Margaret L, editors. Children and AIDS. American Psychiatric Association; Washington, DC, US: 1992. pp. 165–181. [Google Scholar]

- Bor R, du Plessis P. The impact of HIV/AIDS on families: An overview of recent research. Families, Systems, and Health. 1997;15(4):413–427. [Google Scholar]

- Bor R, du Plessis P, Russell M. The impact of disclosure of HIV on the index patient’s self-defined family. Journal of Family Therapy. 2004;26:167–192. [Google Scholar]

- Boyd-Franklin N, Steiner GL, Boland M. Children, families, and HIVAIDS: Psychosocial and therapeutic issues. Guilford Press; New York: 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Boyd-Franklin N. Black families in therapy: Understanding the African American experience. 2nd ed. Guilford Press; New York: 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Bunting SM. Sustaining the relationship: Women’s caregiving in the context of HIV disease. Health Care for Women International. 2001;22:131–148. doi: 10.1080/073993301300003126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carpenter CC, Cooper DA, Fischl MA, Gatell JM, Gazzard BG, Hammer MD, Hirsch MS, Jacobsen DM, Katzenstein DA, Montaner JS, Richman DD, Saag MS, Schecter M, Schooley RT, Thompson MA, Vella S, Yeni PG, Volberding PA. Consensus statement: Antiretroviral therapy in adults: Updated recommendations on the international AIDS society—USA panel. Journal American Medical Association. 2000;283:381–391. doi: 10.1001/jama.283.3.381. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coles RL. Race & ethnicity: A structural approach. Sage Publications; Thousand Oaks, California: 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Conners NA, Bradley RH, Mansell LW, Liu JY, Roberts TJ, Burgdorf K, Herrell JM. Children of mothers with serious substance abuse problems: An accumulation of risks. The American Journal of Drug and Alcohol Abuse. 2004;30(1):85–100. doi: 10.1081/ada-120029867. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Copello AG, Templeton L, Velleman R. Family interventions for drug and alcohol misuse: is there a best practice? Current Opinion Psychiatry. 2006;19:271–276. doi: 10.1097/01.yco.0000218597.31184.41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crepaz N, Lyles CM, Wolitski RJ, Passin WF, Rama SM, Herbst JH, Purcell DW, Malow RM, Stall R. Do prevention interventions reduce HIV risk behaviors among people living with HIV? A meta-analytic review of controlled trails. AIDS. 2006;20(2):143–157. doi: 10.1097/01.aids.0000196166.48518.a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DiMatteo MR. Social support and patient adherence to medical treatment: A meta-analysis. Health Psychology. 2004;23(2):207–218. doi: 10.1037/0278-6133.23.2.207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dorsey S, Chance MW, Forehand R, Morse E, Morse P. Children whose mothers are HIV infected; who resides in the home and is there a relationship to child psychosocial adjustment? Journal of Family Psychology. 1999;13(1):103–117. [Google Scholar]

- Dunbar-Jacob J, Schlenk E. Patient adherence to treatment regimen. In: Baum A, Revenson TA, Singer JE, editors. Handbook of health psychology. Lawrence Erlbaum Associates; Hillsdate, N.J.: 2001. pp. 571–580. [Google Scholar]

- Hackl KL, Somlai AM, Kelly JA, Kalichman SC. Women living with HIV/AIDS: The dual challenge of being a patient and caregiver. Health and Social Work. 1997;22(1):53–62. doi: 10.1093/hsw/22.1.53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Knowlton AR, Hua W, Latkin C. Social support networks and medical service use among HIV-positive injection drug users: Implications to intervention. AIDS Care. 2005;17(4):479–492. doi: 10.1080/0954012051233131314349. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Knowlton A, Buchanan A, Wissow L, Pilowsky DJ, Latkin C. Externalizing behaviors among children of HIV seropositive former and current drug users: Parent support network factors as social ecological risks. Journal of Urban Health. 2007;85(1):62–76. doi: 10.1007/s11524-007-9236-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kotchick BA, Forehand R, Brody G, Armistead L, Morse E, Simon P, Clark L. The impact of maternal HIV infection on inner-city African American families. Journal of Family Psychology. 1997;11(4):447–461. [Google Scholar]

- Leonard NR, Gwadz MV, Cleland CM, Vekaria PC, Ferns B. Maternal substance use and HIV status: Adolescent risk and resilience. Journal of Adolescent. 2008;31:389–405. doi: 10.1016/j.adolescence.2007.07.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McAdoo HP. Black families. 4th ed. Sage Publications; Thousand Oaks, California: 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Pequegnat W, Szapocznik J, editors. Working with families in the era of HIV/AIDS. Sage Publications; Thousand Oaks, California: 2000. Structural ecosystems therapy with HIV-positive African American mothers; pp. 243–279. Author 3. [Google Scholar]

- Relational factors and family treatment engagement among low-income, HIV-postive African American mothers. Family Process. 2003;42(1):31–45. doi: 10.1111/j.1545-5300.2003.00031.x. Author 2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Niccolai LM, D’Entremont D, Pritchett EN, Wagner K. Unprotected intercourse among people living with HIV/AIDS: The importance of partnership characteristics. AIDS Care. 2006;18(7):801–807. doi: 10.1080/09540120500448018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Identifying the family context surrounding HIV+ women in recovery; Poster presented at the annual meeting of the American Psychological Association; San Francisco, California. 2007; Author 4. [Google Scholar]

- Owens S. African American women living with HIV/AIDS: Families as sources of support and of stress. Social Work. 2003;48(2):163–171. doi: 10.1093/sw/48.2.163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pequegnat W, Bauman LJ, Bray JH, DiClemente R, DiIorio C, Hoppe SK, Jemmott LS, Krauss B, Miles M, Paikoff R, Rapkin B, Rotheram-Borus MJ, Szapocznik J. Measurement of the role of families in prevention and adaptation to HIV/AIDS. AIDS and Behavior. 2001;5(1):1–19. [Google Scholar]

- Pequegnat W, Szapocznik J. The role of families in preventing and adapting to HIV/AIDS: Issues and answers. In: Pequegnat W, Szapocznik J, editors. Working with families in the era of HIV/AIDS. Sage Publications; Thousand Oaks, California: 2002. pp. 3–46. [Google Scholar]

- Rotheram-Borus MJ, Flannery D, Rice E, Lester P. Families living with HIV. AIDS Care. 2005;17(8):978–987. doi: 10.1080/09540120500101690. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Structural ecosystems therapy for HIV-seropositive African American women: Effects on psychological distress, family hassles, and family support. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2004;72(2):288–303. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.72.2.288. Author 1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sandelowski M, Lambe C, Barroso J. Stigma in HIV-positive women. Journal of Nursing Scholarship. 2004;36(2):122–128. doi: 10.1111/j.1547-5069.2004.04024.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Townsend AL, Biegel DE, Ishler KJ, Wieder B, Rini A. Families of persons with substance use and mental disorders: A literature review and conceptual framework. Family Relations. 2006;55:473–486. [Google Scholar]

- WHO . CIDI-Auto 2.1: Administrator’s guide and reference. World Health Organization; Sydney, Australia: 1997. [Google Scholar]