Abstract

We examined the distribution of EE and its indices in a sample of 224 family caregivers of individuals with schizophrenia pooled from 5 studies, three reflecting a contemporary sample of Mexican Americans (MA 2000, N = 126), one of an earlier study of Mexican Americans (MA 1980, N = 44, Karno et al., 1987), and the other of an earlier study of Anglo Americans (AA, N = 54, Vaughn et al., 1984). Chi-square and path analyses revealed no significant differences between the two MA samples in rates of high EE, critical comments, hostility, emotional over-involvement (EOI). Only caregiver warmth differed for the two MA samples; MA 1980 had higher warmth than MA 2000. Significant differences were consistently found between the combined MA samples and the AA sample; AAs had higher rates of high EE, more critical comments, less warmth, less emotional over-involvement, and a high EE profile comprised more of criticism/hostility. We also examined the relationship of proxy measures of acculturation among the MA 2000 sample and found that lower acculturation was related to less criticism. Overall, the findings support the earlier observations of Jenkins (1991) regarding the cultural variability of expressed emotion for Mexican Americans. The only exception is that EOI may be more prominent among these largely immigrant caregivers than previously noted. Implications are discussed regarding the cross-cultural measurement of expressed emotion and the focus of family interventions for those with close family ties.

Keywords: Expressed emotion, Mexican Americans, schizophrenia, culture

The study of family factors as they relate to the course of schizophrenia has found that individuals with schizophrenia who return to families high in criticism, hostility or emotional over-involvement (EOI) are more likely to relapse than those who return to families low in these characteristics (Hooley, 2007). A growing number of studies point out that ethnicity and nationality can play an important role in the expression of these family attitudes and emotional reactions (Bhurga & McKenzie, 2003). Jenkins and Karno (1992) argue that significant differences in expressed emotion across national and ethnic groups indicate that culture shapes how families respond to schizophrenia. Moreover, Jenkins (1991, 1992) identifies nuanced ways in which culture can shape the expression of criticism and emotional over-involvement.

Much of the evidence of cross-ethnic and cross-national differences in expressed emotion is based on one-sample studies of a particular ethnic or national group that is different from the original British studies carried out in the late sixties and early seventies (e.g., Brown et al., 1972). Typically an investigator applies the Camberwell Family Interview (CFI) and finds that the distribution of the global measure of EE or one of its indices varies from the original studies. The authors then interpret the observed EE differences as due to culture. It is argued that the different “cultural” group tends to be more critical or more involved because of their cultural background. The consideration of culture is a welcomed addition to the expressed emotion literature because it challenges universalistic assumptions about families and psychopathology (Jenkins & Karno, 1992). However, there are a number of factors that limit the contribution of this line of research.

The Meaning of Cross-Ethnic and Cross-National Differences in Expressed Emotion

First of all, it is not clear what the meaning is of cross-ethnic and cross-national differences. Any observed difference is likely to reflect some degree of cultural influence on how families relate to their ill relative and some degree of measurement variance given the new context (translation limitations and response style differences). Most investigators recognize both factors, however, some focus more on the presumed cultural differences in family processes. Those who focus on cultural differences assume that the CFI and its rating scales function in a similar manner across cultural contexts, and in turn, measure expressed emotion sufficiently well in the new setting. Accordingly, any observed difference in EE ratings is primarily thought to be a function of the phenomena under study. Okasha and associates (1995), for example, found that Egyptians expressed more critical comments toward their ill relatives with affective disorders than previous studies and argued that “criticism seems to be an accepted component of interpersonal relations in our culture…” (p. 1004).

Other investigators are less inclined to assume that the CFI and its ratings scales have the same meaning across cultural contexts. Jenkins (1992) argued that it is important to adapt the measures because “analytic norms derived elsewhere (i.e., England) could not be expected to be of direct cultural relevance or meaning among a Mexican-descent population” (p. 208). From this perspective, observing cross-ethnic and cross-national differences may not necessarily reflect “cultural” differences in expressed emotion, but instead may reflect, at least in part, an artifact of applying an instrument that inadequately measures the given construct in a new cultural context. For example, Jenkins related an incident in which a family caregiver brought home-cooked food daily to her ill relative at the hospital. Jenkins argued that in England this might be judged as overly devoted behavior and thus indicative of emotional overinvolvement, but for some Mexican Americans, particularly those who are recent immigrants and unfamiliar with the institutional context, this would not be an indicator of EOI. From this perspective, failing to adapt the measures to the specific cultural context would likely result in the over-identification of EE. What is considered a normative degree of family involvement may be judged as over-involvement. Thus, the observed cross-ethnic or cross-national differences may not necessarily reflect actual group differences in the rates of expressed emotion but instead reflect the incongruities of the non-adapted measure when applied in a new cultural context.

To avoid the category fallacy (Kleinman, 1988), that is, assuming that a given construct or category applies cross-culturally, some investigators have suggested that the original EE indices and their ratings may require some adaptation (e.g., Jenkins, 1992; Phillips & Xiong, 1995). It should be noted that all investigators make at least some modifications given a new cultural context, particularly those who translate the CFI into a language other than English. However, there are potential limitations in adapting the original rating scale, particularly early on in the research. First of all, modifying the metric makes it difficult to compare the findings with other studies that make little or no adjustments. For example, returning to Jenkins earlier example of emotional overinvolvement, if adjustments were made to the ratings of EOI it is possible that they could serve to attenuate or obscure actual group differences, the very differences that would support the need for adjustment. To date the literature is not clear about when and how cultural adjustments should be made. We believe that identifying clear ethnic or national differences with the unadjusted original scales is important before adapting the scales to a given sociocultural context. Doing so will help clarify whether cultural adjustments are needed.

Possible Differences in Profiles of High Expressed Emotion Across Ethnic Groups

Another limitation of cross-ethnic or cross-national comparative studies is that they refer to group differences in either the percentage of caregivers who are high EE or in the mean number of critical comments or the mean rating of emotional over-involvement (Mino et al., 1995). These two approaches consider the entire sample of caregivers, both high and low EE caregivers. Another way to identify group differences is to examine the subtypes or profiles of only the high EE caregivers, in other words whether high EE is due to criticism/hostility or to emotional overinvolvement. This approach is worth considering because two samples could have virtually the same rates of high EE, yet the type of high EE represented could be markedly different. One group could primarily reflect the dimension of criticism/hostility whereas another group could primarily reflect the dimension of emotional over-involvement. To date, group differences in high EE profiles or subtypes have received little attention. A more complete assessment of cross-cultural differences would do best to examine high EE profiles as well as examine the distributions of specific EE ratings across the entire sample.

Evidence for the Intracultural Variability of Expressed Emotion

Proxy measures of culture such as place of birth (foreign born vs. native born), language dominance (Spanish or English), and acculturation level could also serve to buttress cultural interpretations of cross-ethnic or cross-national findings. Consider the cultural hypothesis that criticism is not well accepted by some Mexican immigrant families, as suggested by the prior Mexican American – Anglo American difference in critical comments (Jenkins, 1991). If this is indeed the case, then the proxy cultural measures would demonstrate that critical comments are lower for caregivers who were born in Mexico, who speak Spanish, or who are lower on an acculturation index than those caregivers who were born in the United States, who speak English, or who are higher on the acculturation index. The lack of association between the proxy measures of culture and the EE indices would suggest that cultural processes may not be as relevant in explaining the cross-national and cross-ethnic group differences. Tests of the relationship between expressed emotion and proxy cultural measures could help further assess the cultural basis of expressed emotion.

Overview

The overall objective of the current study was to advance our understanding of the cultural nature of the manifestation of expressed emotion and its indices, primarily with a contemporary sample of Mexican American family caregivers recruited from 1999 to 2004. To obtain this sample, we pooled the data from three related projects of Mexican Americans (Dorian et al., 2008, Kopelowicz et al., 2006, Lopez et al., 2008). We refer to this sample as Mexican American (MA) 2000, as most of the recruitment was carried out in the early part of 2000. Although the principal investigators and teams of interviewers differed, the same team of raters coded the Camberwell Family Interviews. We then compared the global construct of EE and its specific indices for this sample with two earlier samples: (a) Mexican Americans recruited from 1980 to 1984 which we refer to as MA 1980 (Karno et al., 1987); and (b) Anglo Americans recruited from the late 1970s through the early 1980s which we refer to as AA (Vaughn et al., 1984).

The first specific aim was to test the replicability of the two decade old findings of Mexican American family caregivers regarding their level of global EE (high versus low) and their specific EE indices. To accomplish this, we tested whether there were differences between the MA 1980 and MA 2000 samples.

The second specific aim was to assess the cultural nature of expressed emotion and its indices for the entire sample. To accomplish this, we tested for cross-ethnic differences in global EE and specific EE indices by comparing both MA 1980 and MA 2000 with AA. Based on prior research pointing out ethnic differences in EE, criticism (Jenkins, 1991), and warmth (as related to relapse; Lopez et al., 2004), we expected Mexican Americans to have lower global EE, lower critical comments, and lower hostility, as well as higher warmth than Anglo Americans. Based on Mexican American caregivers’ high tendency to live with their ill relatives (Ramírez García, Wood, Hosch, & Meyer, 2004; Snowden, 2007), we expected greater emotional overinvolvement for the MA samples than the AA sample. We also tested for ethnic differences in the high EE profiles. Consistent with the previously identified ethnic differences in specific EE indices, we expected that Mexican American caregivers would have less critical profiles and more emotional over-involvement profiles than Anglo American caregivers.

As a second approach to assess the cultural basis of expressed emotion, we tested the hypothesis that acculturation among Mexican Americans would be related to expressed emotion. Specifically, we expected that lower acculturation would be associated with lower rates of high EE, less criticism, less hostility, more emotional overinvolvement and more warmth.

Method

Participants

We summarize in Table 1 the key study characteristics of each of the original five studies that were pooled together to comprise the sample for this study. Participants were 224 key relatives and 224 patients with schizophrenia or schizoaffective disorder (one relative for each patient). The MA 2000 sample of 126 Mexican Americans was comprised of three recent studies of expressed emotion: Santa Fe Springs/Granada Hills (n = 60, Lopez et al., 2008), El Paso (n = 44, Dorian et al., 2008), and Granada Hills (n = 22, Kopelowicz et al., 2006). The MA 1980 sample of 44 Mexican American caregiver-patient dyads was obtained from the Karno et al., (1987) study and the AA sample of 54 Anglo American caregiver-patient dyads was obtained from the first replication study in the United States (Vaughn et al., 1984).

Table 1.

Origin of Samples, Years of Recruitment, Sample Sizes, and Research Site

| Mexican Americans 2000s | ||||

| Kopelowicz et al., 2006 | 1999-2002 | 22 | Outpatient | Granada Hills, CA |

| Dorian et al., 2008 | 2000-2003 | 44 | Outpatient | El Paso, Texas |

| Lopez et al., 2008 | 2003-2006 | 60 | Outpatient | Santa Fe Springs & Granada Hills, CA |

| Mexican Americans 1980s | ||||

| Karno et al., 1987 | 1979-1983 | 44 | Inpatient | Southern California |

| Anglo Americans 1970s-1980s | ||||

| Vaughn et al., 1984 | 1978-1982 | 54 | Inpatient | Southern California |

| Total | 224 | |||

Key relatives were defined as adult family members living with or having regular contact with the ill relative. They included parents (70%), siblings (13%), spouses/partners (12%), or other relatives (5%). All patients met the following selection criteria: (a) 17-60 years of age; (b) of Mexican American or Anglo American descent; (c) living with or in regular contact with a close relative; and (d) diagnosed as having schizophrenia or schizoaffective disorder based on the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV (First et al., 2002) or the Present State Examination (PSE; Wing, Cooper, & Sartorious, 1974).

Measures

Expressed emotion

An abbreviated form of the Camberwell Family Interview (CFI) was used to classify the key relatives as high or low EE. The CFI is a one to two hour semi-structured interview administered to family members to assess the circumstances in the home three months prior to the patient’s admission to the hospital (Leff & Vaughn, 1985) or three months prior to the day of the interview for outpatients who were not recently hospitalized (e.g., Kopelowicz, et al., 2006). All interviews were audiotaped for later analysis. For the MA 2000 studies, the Spanish language CFI translated by Jenkins et al. (1986) and the English language CFI used by Vaughn et al. (1984) served as the templates for the interviews.

The original CFI criteria (Leff & Vaughn, 1985) for scoring the key relatives’ criticism, hostility, EOI, and warmth were used. We do not report the results for positive remarks as very few studies have found an association between positive remarks and clinical outcome. Six or more critical comments, a score of 1-3 on the four-point hostility scale, or a score of 4-5 on a six-point scale for EOI results in a high EE rating (Leff & Vaughn, 1985).

For the MA 1980 and AA studies, we were given permission to use the original data from the investigators. The reliabilities of the CFI and specific rating scales were reported as adequate. For the MA 2000 studies, a separate team of seven coders rated the interviews. The initial team of four coders was trained by Karen Snyder, one of the key investigators of the AA study. Our training tapes were taken largely from the earlier Anglo American study. The range of the reliabilities (intraclass correlation coefficients) for this team was: criticism (0.73 - .97), hostility (0.74 - 1.0), emotional over-involvement (0.69 - 0.95) and warmth (0.73 - 0.94).

The raters for the MA 1980 and AA studies had no knowledge that their CFI ratings would be compared with one another. Therefore they were blind to the hypotheses. The raters for the MA 2000 studies varied with regard to their knowledge of the culture and expressed emotion literature. Some were aware of and some were unaware of the ethnic differences in EE. However, the main purpose of coding was to relate EE to relapse, not to compare EE ratings with other studies and other ethnic groups. In fact, the current analyses were conceptualized after the CFI ratings were completed. As a result, it seems unlikely that even the raters with knowledge of the EE literature could have biased their ratings in favor of the hypotheses and swayed their peers who were not knowledgeable of the EE literature.

Proxy Measures of Acculturation

For the MA samples, place of birth was primarily asked during the direct inquiry of sociodemographic background. Primary language of the participants was determined largely by the language they preferred in carrying out their assessments. To assess U.S. acculturation, the 12 items that assess English language use and media preferences of the Bidimensional Acculturation Scale (BAS; Marin & Gamba, 1996) were used in the Santa Fe Springs/Granada Hills study and the El Paso study. The responses to these 12 items were summed and divided by 12 to generate a U.S. acculturation score. This measure possessed excellent reliability for our sample (Cronbach’s alpha = 0.96).

Procedures

For the MA 2000 sample, individuals were recruited through outpatient clinics whereas for the MA 1980 and the AA samples, individuals were recruited from recent admissions to inpatient facilities. In the MA 1980 and AA samples, as well as the Granada Hills subsample of the MA 2000 sample, there were occasions when more than one family member (e.g., two parents) was interviewed for a given patient. In those cases, the higher of the two relatives’ scores was used to determine the EE classification of the household. In the Santa Fe Springs/Granada Hills and the El Paso sample only one CFI was administered for each patient. Efforts were made to identify the caregiver who had the greatest contact with the ill relative.

Results

We first present the findings from chi-square analyses and t-tests regarding the socio-demographic and clinical background of the MA 2000, MA 1980, and AA samples. Second, we carried out chi-square analyses to assess whether there were differences across the three samples regarding global expressed emotion. Third, a series of path analysis models were conducted to test the ethnic and acculturation hypotheses of the indices of expressed emotion. Fourth, we conducted chi-square analyses to assess whether the profiles of high EE caregivers differ across the samples.

Sociodemographic and Clinical Background

Across the three samples of the MA 2000, the MA 1980, and the AA studies, the caregivers were primarily women (range: 70% to 83%) and primarily parents (range: 62% to 89%). (See Table 2 for the background characteristics by sample.) The gender distribution did not differ between the three samples, χ2 (2) = 3.89, p = 0.14, however, there were significant differences across the samples in the proportion of parental caregivers, χ2 (2) = 12.70, p = .002. This difference is due to the two Mexican American samples (MA 2000 = 62.4%; MA 1980 = 70.5%) having a lower proportion of parental caregivers than the Anglo American sample (88.9%, MA 2000-AA: χ2 [1] = 12.69, p < .0001; MA 1980-AA χ2 [1] = 5.27, p = .02). There were no differences in the proportion of parental caregivers between the two Mexican American samples, χ2 (1) = 0.94, p = 0.33. Caregiver age was only available for the two Mexican American samples. The MA 2000 sample tended to be older (M = 52.74) than the MA 1980 sample (M = 47.89), t [164] = 1.94, p = .05). After implementing a Bonferroni correction to maintain an alpha of .05 (α/6 = .008), the difference in the proportion of parental caregivers across the three samples of caregivers and between the MA 2000 and AA samples remained significant.

Table 2.

Social and Clinical Characteristics by Sample

| Mexican Americans 2000s |

Mexican Americans 1980s |

Anglo Americans 1970-80s |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N |

M or % |

SD | N |

M or % |

SD | N |

M or % |

SD | |

| Caregivers | |||||||||

| Age | 122 | 52.74 | 14.74 | 44 | 47.89 | 12.71 | |||

| Women | 126 | 83% | 44 | 80% | 54 | 70% | |||

| Parents | 125 | 62% | 44 | 71% | 54 | 89% | |||

| Born in Mexico | 100 | 72% | 44 | 68% | |||||

| Mainly Spanish | 126 | 60% | 44 | 68% | |||||

| Patients | |||||||||

| Age | 126 | 37.67 | 11.03 | 44 | 25.5 | 6.96 | 54 | 26.06 | 7.16 |

| Years Ill | 117 | 14.99 | 10.96 | 44 | 4.21 | 3.40 | 54 | 4.59 | 4.24 |

| Hospitalizations | 121 | 3.02 | 1.96 | 44 | 3.16 | 2.80 | 51 | 2.98 | 2.12 |

| Men | 126 | 66% | 44 | 57% | 54 | 76% | |||

| Born in Mexico | 121 | 56% | 44 | 59% | |||||

| Mainly Spanish | 126 | 42% | 44 | 39% | |||||

An examination of patient characteristics indicates that the MA 2000 patients were significantly older than the other two samples of patients--12 years older than the MA 1980 sample (t [119.73] = 8.46, p < .0001) and nearly 12 years older than the AA sample (t [149.93] = 8.39, p < .0001). The patients’ ages for the earlier studies were nearly identical (MA 1980 M = 25.50 years; AA M = 26.06 years). Given the older patient age of the MA 2000 sample, they also report a significantly longer time period of having been ill than their counterparts, MA 2000 M = 14.99 years, MA 1980 M = 4.21 years, and AA M = 4.59; MA 2000 - MA 1980 (t [155.49] = 9.50, p < .0001) and MA 2000-AA (t [165.42] = 8.92, p < .0001). The reported number of hospitalizations (Ms = 3.02, 3.16, and 2.98), however, did not differ for the three patient groups F (2,213) = 0.09, p = 0.92. The patient’s gender was also not significantly different across the 3 samples, χ2 (2) = 4.01, p = 0.13, though the AA sample had the greatest proportion of men (76%) and the MA 1980 had the lowest proportion of men (57%). The observed background differences in the patients’ age and the years of illness remain significant even with a Bonferonni correction (α/6 = .008).

Chi-square analyses of the two Mexican American caregiver and patient samples revealed no differences with regard to place of birth and primary language (ps = 0.35 to 0.74). Over two-thirds of both caregiver samples were born in Mexico and at least 60% reported speaking primarily Spanish. Over half of the two patient samples were born in Mexico and about 40% spoke primarily Spanish.

Ethnic Comparisons of Global Expressed Emotion

A set of chi-squares were performed to examine whether the distribution of the global measure of expressed emotion varied across samples. A significant difference was observed in the distributions of high and low EE by sample, χ2 (2) = 14.63, p = .001, Φ = 0.26. The two Mexican American samples were nearly identical with regard to the proportion of high EE caregivers (MA 2000 = 36.5%, MA 1980 = 38.6%) whereas the Anglo American sample contained a much larger proportion of caregivers designated as high EE (66.7%). Follow-up chi-square tests indicated no differences between the Mexican American samples (χ2 [1] = 0.06, p = 0.80) and significant differences between each of the Mexican American samples and the Anglo American sample (MA 2000 χ2 [1] = 13.86, p < .0001, Φ = .28; MA 1980 χ2 [1] = 7.67, p = .006, Φ = 0.28). The observed differences remained significant with Bonferonni corrections (α/4 = .0125).

Ethnic Comparisons of EE Indices

A series of path analysis models were estimated to test whether differences in the indices of expressed emotion can be accounted for by sample and demographic characteristics (caregiver relationship, patient age, and duration of illness). In these models the samples were coded by creating two new dummy variables with contrast coding (Keppel & Wickens, 2004). One variable compared the MA samples versus the AA sample and the other variable compared the two MA samples. For each hypothesis, a model was first estimated with only the two variables that were coded to represent type of sample as predictors of the indices of expressed emotion (criticism, hostility, EOI, and warmth). Significant path coefficients for these paths indicate that the samples differ. Then, this model was compared to a model that contained both the primary hypothesized paths as well as the three demographic characteristics (nonparental or parental caregiver, patient’s age, years ill). These models were compared using a chi square difference test. There was evidence to support the statistical assumptions underlying path analysis (Ullman, 2007). Twelve cases contained missing data. There was evidence that these data were missing at random and therefore missing data was estimated using ML techniques in EQS (Bentler, 2007). The models were estimated with ML estimation and evaluated for fit using the chi square test statistic as well as with the confirmatory fit index (CFI).

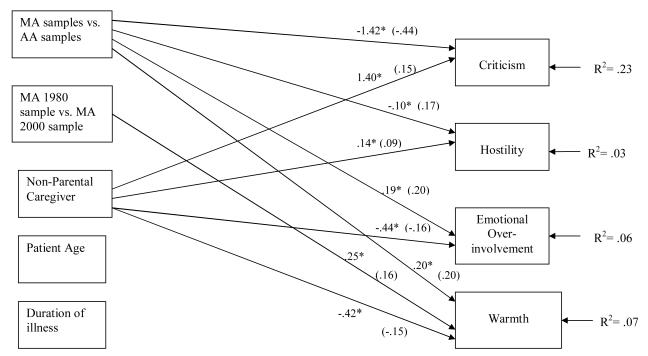

A path analysis model was estimated that predicted criticism, hostility, EOI, and warmth from the three samples of MA 1980, MA 2000, and AA. This grouping variable was divided into two predictors: MA 1980 v. MA 2000 and MA samples combined vs. AA. There was evidence that the model fit the data, χ2 (N=225, 13) = 21.67, p = .06, CFI = .98. MA 1980 was higher in warmth than MA 2000. There was no difference between the MA groups in terms of criticism, hostility, or EOI. The combined MA samples were less critical, less hostile, had greater EOI and greater warmth than the AA sample. (See Table 3 for the means of the EE indices.)

Table 3.

Expressed Emotion Indices by Sample

| MA | 2000 | MA | 1980 | AA | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | = 126 | N | = 43 | N | = 54 | |

| EE Index | M | SD | M | SD | M | SD |

| Criticism | 3.10 | 2.98 | 3.86 | 3.20 | 7.59 | 5.13 |

| EOI | 2.29 | 1.32 | 2.42 | 1.07 | 1.89 | 1.37 |

| Warmth | 2.78 | 1.21 | 3.26 | 1.35 | 2.50 | 1.26 |

A second model was tested that predicted criticism, hostility, EOI, and warmth from type of sample Mexican American 1980 (MA 1980), Mexican American 2000 (MA 2000) and Anglo American (AA) and added three additional prediction paths from relationship of caregiver to patient (nonparental or parental), patient’s age, and number of years the patient was ill. The model did not significantly improve with the addition of these variables, χ2difference (N=225, 12) = 18.90, p > .05. This model also fit the data well, χ2 (N=225, 1) = 2.77, p = .09, CFI = .99.

After the inclusion of relationship of caregiver to patient (non-parent or parent), patient’s age, and number of years the patient was ill, the MA 1980 group was still higher in warmth than MA 2000 and there continued to be no difference between the MA groups in terms of criticism, hostility, or EOI. MAs continued to be less critical, less hostile, had greater EOI and greater warmth than the AA sample. The relationship of the caregiver to the patient predicted differences in the outcome variables. Relative to parental caregivers, non-parental caregivers were more critical and hostile and less emotionally overinvolved and warm. Age of the patient and the number of years the patient had been ill did not predict any of the outcome variables.

A final model was estimated in which the non-significant paths were dropped. This model fit the data χ2 (N=225, 12) = 13.21, p = .35. CFI = .99. Deletion of the nonsignifcant paths did not significantly degrade the model, χ2difference (N=225, 10) = 10.43, p > .05. See Figure 1 for the final model for which squares represent measured variables and lines connecting the variables represent hypothesis. The arrow points to the dependent variable. Also, although residuals were estimated and all the predictors were allowed to covary, these paths are not included in the figure for ease of interpretability.

Figure 1.

Path model for prediction of Expressed Emotion Indices. Note unstandardized coefficients and significance levels (p <. .05) are indicated for each path. Standardized regression coefficients are indicated with parenthesis.

Mexican American Families’ Acculturation Levels and Expressed Emotion Indices

A second set of models was estimated to test the hypothesis that for Mexican Americans expressed emotion indices (criticism, hostility, EOI, and warmth) can be predicted by level of caregiver acculturation as measured by caregiver’s place of birth (US or Mexico), caregiver’s primary language (Spanish or English), and the acculturation index. Additionally it was hypothesized that these predictive relationships would be maintained even after the inclusion of the relationship of the caregiver to the patient (nonparent or parent), age of the patient, and number of years the patient had been ill. The acculturation data were not normally distributed, Yuan, Lambert, and Fouladi’s (2004) normalized coefficient = 6.46, p < .001. Therefore, these models were estimated with Yuan-Bentler Scaled Chi Square. The first model included only the three acculturation predictors. This model fit the data, Yuan-Bentler, χ2 (N=127, 14) = 22.34, p = .07, CFI = .97. The set of acculturation predictors explained 4.8% of the variance in criticism. Lower acculturation as measured by the acculturation index predicted less criticism, unstandardized coefficient for acculturation = .97, p < .05. Birthplace and language were not significant predictors of the expressed emotion components.

A second model was tested that added regression paths predicting the expressed emotion components from the acculturation indicators as well as the caregiver and patient characteristics (relationship of the caregiver to the patient, age of the patient, and number of years the patient had been ill). This model also fit the data well, Yuan-Bentler, χ2 (N=127, 2) = 8.82, p = .01, CFI = .98. This model was not a significant improvement over the model without the family/patient characteristics perhaps due to the significant correlation (r(125) = .23, p < .05) between familial status of caregiver (nonparental vs. parental caregiver) and the acculturation index. When both are included as predictors, acculturation no longer predicts criticism. Within the context of this model parental caregivers have more EOI and more warmth (unstandardized coefficient for EOI = −.58, p < .05, unstandardized coefficient for warmth = −.63, p < .05.).

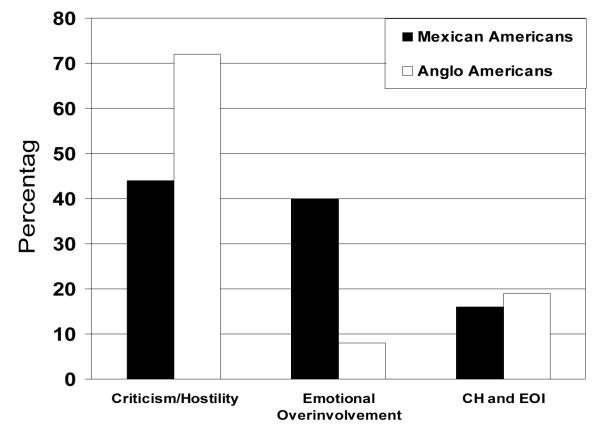

Ethnicity and High Expressed Emotion Profiles

The prior analyses examined the predictors and distribution of expressed emotion and its indices across all caregivers regardless of EE designation. To examine whether high expressed emotion (excluding low EE) manifested itself differently for the two ethnic groups, we tested for ethnic differences in the distribution of the three high EE profiles (a) high criticism, hostility or both (CH), (b) high emotional over-involvement (EOI), and (c) mixed (high in criticism or hostility and high in emotional over-involvement). We included criticism and hostility within the same group because they are highly correlated (r = 0.51 in our sample). We combined the two Mexican American samples as the prior analyses identified no significant within-group differences in the three main EE indices. The 2 (ethnicity) × 3 (profile types) chi-square analysis was significant, χ2 (2) = 11.37, p = .003, Φ = 0.34. An examination of the distribution of high EE profiles (see Figure 2) shows that there are clear ethnic differences in the high EE profiles of criticism/hostility (MAs = 44%; AAs = 72%) and emotional over-involvement (MAs = 40%; AAs = 8%), but no ethnic differences for the mixed subtype (MAs = 16%; AAs = 19%). The two high EE profiles are evenly distributed among Mexican American caregivers whereas the high EE-criticism/hostility profile is dominant among Anglo American caregivers

Figure 2.

High Expressed Emotion Profiles by Ethnicity

Discussion

We found considerable similarity in the distribution of expressed emotion and its indices across the two Mexican American samples. The percentage of high EE caregivers was nearly identical for the earlier sample and the contemporary sample (38.6% and 36.5%). We also found no Mexican American group differences in the specific indices of criticism, hostility, emotional overinvolvement, but did find differences in warmth. The Mexican American (MA) 1980 sample was rated significantly higher in warmth than the MA 2000 sample. Other than the warmth difference, the overall similarity is remarkable when considering the significant differences between both samples: (a) independent teams of CFI interviewers and coders, (b) the patient sample was recruited from inpatient facilities for the earlier study and outpatient clinics for the contemporary study, (c) the patients differed in the number of years they had been ill, and (c) over 20 years had lapsed between the data collection for the two studies. Replicating the previous pattern of findings points out the robust nature of how expressed emotion is manifested for these Mexican American caregivers. Given that both groups of caregivers were largely Spanish-speaking immigrants this pattern of EE likely reflects the groups’ similar local social worlds (Kleinman, 1995) of leaving ones home community and adapting to a foreign home. Family connections are invaluable in surviving in a new and sometimes hostile environment. Note that we are not arguing that the EE pattern reflects something about a presumed monolithic Mexican American culture.

In addition to the considerable similarity of expressed emotion for the two Mexican American samples, we observed ethnic differences between the Mexican American and Anglo American samples on each of the EE indices. The two Mexican American samples expressed a significantly lower number of critical comments, less hostility, more emotional overinvolvement, and more warmth than did the Anglo American sample. This is very much in line with Jenkins et al.’s (1986) observations that Mexican American caregivers tend not to view their ill relatives in a judgmental manner but rather express considerable empathy for their condition, as suggested by greater references to feeling sad (see also Weisman et al., 1993). These findings are also consistent with other findings that Mexican American family caregivers are more involved in the lives of their ill relatives than Anglo American family caregivers (Ramirez Garcia et al., 2004; Snowden, 2007).

In addition, an examination of only the high EE caregiver profiles reflects significant ethnic differences. What is most striking is that among Anglo American caregivers nearly three-fourths (72%) were high EE due to criticism and hostility and only 8% were high EE due to emotional overinvolvement. This is consistent with earlier studies in which criticism/hostility has been the dominant mode of expressed emotion (e.g., Brown, Birley & Wing, 1972). Among Mexican Americans, however, the high EE profile is more evenly distributed among the criticism/hostility (44%) and emotional overinvolvement (40%) dimensions. Although the predominance of the criticism/hostility profile for Anglo Americans is most striking, the significant percentage of high emotionally overinvolved Mexican American families is a novel finding.

Similar to previous research, the identification of cross-ethnic differences suggests that culture plays an important role in the expression of these family attitudes and emotional reactions. Our study extends this research in important ways. First, it helps to rule out rival methodological explanations. One such explanation is that the previously observed MA 1980 – AA differences in global EE and criticism is a function of methodological differences between the two studies, particularly in the administration and coding of the CFI. Changes in the administration and coding of the semi-structured interview can go undetected from one study to the next, especially if the interviews are carried out in a language other than English. The fact that we found similar ethnic differences for both the global EE index and the four specific indices across two largely independent research teams argues against the rival hypothesis of administration and coding differences. A second alternative hypothesis is that the earlier ethnic difference reflects something about the time period under study, such as mental health services received by the two ethnic groups. Observing the same ethnic differences when using a sample obtained in the 1980s and a sample obtained in the 2000s suggests that the findings are independent of the time period under study. Our findings also rule out key sample characteristics as plausible explanations for the ethnic differences, specifically the parental status of caregivers, the patient’s age, and their years of illness.

In addition to ruling out competing methodological explanations, we also assessed the relationship of proxy cultural measures (acculturation) with the expressed emotion indices among the Mexican American 2000 sample. We found additional evidence for the cultural nature of criticism. Specifically, the caregivers’ lower acculturation level as measured by an acculturation index was found to be associated with less critical comments. This is consistent with the observed ethnic difference of less critical comments among Mexican Americans than Anglo Americans. However in the context of other caregiver and patient characteristics such as the caregiver’s relationship to the ill relative (nonparent versus parent), age of patient, and length of illness, acculturation was no longer associated with criticism. The caregiver’s parental status appears to account for the acculturation-criticism association as nonparental caregivers were more acculturated and more critical than parental caregivers. It should be noted that the acculturation measure predicted only criticism, not any of the other EE indices. Moreover, neither of the other two proxy measures of culture, the caregiver’s place of birth and preferred language predicted components of expressed emotion. Overall, the within-group proxy measures of culture tended not to be significant predictors of the expressed emotion indices.

Implications

Our findings add to the growing support of the cultural nature of expressed emotion (Bhurga & McKenzie, 2003). The results are also consistent with prior research that highlighted important cultural differences regarding criticism (Jenkins, 1991). In addition, the current findings of ethnic differences in the degree of warmth complement past research that found family warmth predicted relapse for Mexican Americans with schizophrenia (Lopez et al., 2004). In that study we did not examine ethnic group differences in the EE indices. The consistent ethnic difference regarding emotional overinvolvement is probably the most significant finding. Both sets of findings using EOI as a continuous measure and as a profile of high EE indicate that emotional overinvolvement is a more salient indicator of expressed emotion for Mexican Americans than Anglo Americans. These findings suggest that greater attention be given to the study of emotional over-involvement, at least among primarily immigrant Mexican Americans and other groups that promote high involvement with ill relatives.

The robust ethnic differences support cultural explanations for the observed ethnic differences. Nevertheless, questions regarding the meaning of the measures are still likely to be raised. Some may even argue that the observed ethnic differences call for adjustments to be made in the rating of Mexican Americans and other ethnic or national groups in which findings deviate from those of the seminal studies. From our view, the observation of group differences in global EE or in the specific indices tell us little about the meaning of expressed emotion and whether adjustments in the measures are needed. The relationship of the indices to relapse is much more telling about the meaning of expressed emotion. Until further evidence is provided that a given index is not related to the course of illness, we think it is best not to adjust such ratings. However, if adjustments are made it would be wise to document specifically how such modifications were carried out and to test whether the culturally adjusted EE domain measures have incremental predictive validity compared to the unadjusted measure.

A final implication concerns family treatment. The current evidence-based family interventions largely emphasize reduction in family negativity through psychoeducation, problem solving, communication training, or some combination of these components (e.g., McFarlane, 2002). Our current and previous research suggests that greater attention be given to emotional over-involvement in family interventions. Not only is EOI high among Mexican Americans as demonstrated here but in a previous analysis of the MA 1980 sample, we found a curvilinear relationship between EOI and relapse. When compared to existing levels of relapse across EE studies, a moderate degree of involvement is associated with less relapse whereas a high degree of involvement is associated with more relapse (Breitborde, 2007). In addition, recent behavioral interaction studies shed light on the important role of emotional overinvolvement. Kopelowicz et al. (2006) found that porous boundaries and enmeshed family involvement between caregivers and their ill relatives predicted a greater risk for relapse. Furthemore, Dorian et al (2008) found that Mexican American caregivers who engaged in problem solving with ill relatives from a balanced vantage point (neither withdrawing nor overtly blaming) had lower levels of EOI. Taken together these findings suggest that a caregiving approach that manages close ties without becoming overly involved deserves close attention in family interventions with largely immigrant Mexican American caregivers and other caregivers with close family ties.

Limitations

Although the results advance the view that expressed emotion and its indices are influenced by cultural processes, there are weaknesses in this interpretation. First of all, there may be differences between the groups in variables not accounted for in our analyses that may largely or partly account for ethnic differences in EE and its indices. For example, the Mexican origin participants were from the lower socioeconomic strata whereas the Anglo American sample included participants from both middle and lower socioeconomic backgrounds. The lack of comparable measures across the three main samples limited our ability to examine the role of socioeconomic status. Another consideration is not having a contemporary sample of Anglo Americans. Consistent findings of the older Anglo American sample with a more contemporary sample would have strengthened the cultural interpretations.

Another limitation is the use of the proxy measures of culture. The acculturation index was based largely on language use, which overlapped with the dichotomous variable of primary language. Both of these measures, along with birthplace, are at best distal measures of culture. Future research that examines the local social worlds of caregivers’ and their ill relatives will advance our understanding of culture and expressed emotion beyond the distal indicators of acculturation.

Conclusions

Our findings add to the growing support for the role of culture in the manifestation of expressed emotion. Our consideration of within ethnic group comparisons across time and between ethnic group comparisons together point out the relative stability of cultural variations in expressed emotion among Mexican Americans who are primarily immigrants. Steps to test culture and to rule out alternative hypotheses will serve to strengthen the empirical base of the study of culture, expressed emotion, and the course of schizophrenia.

Footnotes

The definitive version is available at www.blackwell-synergy.com

Contributor Information

Steven R. López, University of Southern California

Jorge I. Ramírez García, University of Illinois, Urbana Champaign

Jodie B. Ullman, California State University, San Bernardino

Alex Kopelowicz, University of California, Los Angeles

Janis Jenkins, University of California San Diego

Nicholas J. K. Breitborde, Yale University

Perla Placencia, Center for Immigrant Families

References

- Bhugra D, McKenzie K. Expressed emotion across cultures. Advances in Psychiatric Treatment. 2003;9:342–348. [Google Scholar]

- Breitborde NJK, López SR, Wickens TD, Jenkins JH, Karno M. Toward specifying the nature of the relationship between expressed emotion and schizophrenic relapse: The utility of curvilinear models. International Journal of Methods in Psychiatric Research. 2007;16:1–10. doi: 10.1002/mpr.194. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown GW, Birley JL, Wing JK. Influence of family life on the course of schizophrenic disorders: A replication. British Journal of Psychiatry. 1972;121:241–258. doi: 10.1192/bjp.121.3.241. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dorian M, Ramírez García JI, López SR, Hernández B. Acceptance and expressed emotion in Mexican American caregivers of relatives with schizophrenia. Family Process. 2008;47:215–228. doi: 10.1111/j.1545-5300.2008.00249.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- First MB, Spitzer RL, Gibbon M, Williams JBW. Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV-TR Axis I disorders, Research version, Patient edition with psychotic screen. Biometrics Research, New York State Psychiatric Institute; New York: 2002. (SCID-I/P W/PSY SCREEN) [Google Scholar]

- Hooley J. Expressed emotion and relapse of psychopathology. Annual Review of Clinical Psychology. 2007;3:329–352. doi: 10.1146/annurev.clinpsy.2.022305.095236. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jenkins JH. Conceptions of schizophrenia as a problem of nerves: A cross-cultural comparison of Mexican-Americans and Anglo-Americans. Social Science and Medicine. 1988;26:1233–1244. doi: 10.1016/0277-9536(88)90155-4. Jenkins, J. H. (1988) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jenkins JH. Too close for comfort: Schizophrenia and emotional overinvolvement among Mexicano families. In: Gaines AD, editor. Ethnopsychiatry: The cultural construction of professional and folk psychiatries. State University of New York Press; Albany: 1992. pp. 203–221. [Google Scholar]

- Jenkins JH. Anthropology, expressed emotion, and schizophrenia. Ethos. 1991;19:387–431. [Google Scholar]

- Jenkins JH, Karno M. The meaning of expressed emotion: Theoretical issues raised by cross-cultural research. American Journal of Psychiatry. 1992;149:9–21. doi: 10.1176/ajp.149.1.9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jenkins JH, Karno M, de la Selva A, Santana F. Expressed emotion in cross-cultural context: Familial responses to schizophrenic illness among Mexican Americans. In: Goldstein MJ, Hand I, Hahlweg K, editors. Treatment of schizophrenia: Family assessment and intervention. Springer-Verlag; New York: 1986. pp. 35–49. [Google Scholar]

- Karno M, Jenkins JH, de la Selva A, Santana F, Telles C, López S, Mintz J. Expressed emotion and schizophrenic outcome among Mexican-American families. Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease. 1987;175:143–151. doi: 10.1097/00005053-198703000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keppel G, Wickens TD. Design and Analysis: A researcher’s handbook. 5th Ed Pearson; New Jersey: [Google Scholar]

- Kleinman A. Rethinking psychiatry: From cultural category to personal experience. Free Press; New York: 1988. [Google Scholar]

- Kleinman A. Writing at the margin: Discourse between anthropology and medicine. University of California Press; Berkeley, CA: 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Kopelowicz A, López SR, Zarate R, et al. Expressed emotion and family interactions in Mexican-Americans with schizophrenia. Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease. 2006;194:330–334. doi: 10.1097/01.nmd.0000217880.36581.6b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leff J, Vaughn C. Expressed emotion in families: Its significance for mental illness. The Guilford Press; New York: 1985. [Google Scholar]

- López SR, Kopelowicz A, Breitborde N, Aguilera A, Cervantes M. Prosocial processes in Mexican American caregivers’ relations with family members with schizophrenia: Culture and course of illness. Research in process. 2008 [Google Scholar]

- López SR, Hipke KN, Polo JA, Jenkins JH, et al. Ethnicity, expressed emotion, attributions, and course of schizophrenia: Family warmth matters. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 2004;113:428–439. doi: 10.1037/0021-843X.113.3.428. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marín G, Gamba RJ. A new measurement of acculturation for Hispanics: The bidirectional acculturation scale for Hispanics (BAS) Hispanic Journal of Behavioral Sciences. 1996;18:297–316. [Google Scholar]

- McFarlane WR. Multifamily groups in the treatment of severe psychiatric disorders. Guilford Press; New York: 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Mino Y, Tanaka S, Inoue S, Tsuda T, Babazono A, Aoyama H. Expressed emotion components in families of schizophrenic patients in Japan. International Journal of Mental Health. 1995;24:38–49. [Google Scholar]

- Okasha A, El Akabawi AS, Snyder KS, et al. Expressed emotion, perceived criticism, and relapse in depression: A replication in an Egyptian community. American Journal of Psychiatry. 1995;151:1001–1005. doi: 10.1176/ajp.151.7.1001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Phillips MR, Xiong W. Expressed emotion in Mainland China: Chinese families with schizophrenic patients. International Journal of Mental Health. 1995;24:54–75. [Google Scholar]

- Ramírez García JI, Wood JM, Hosch HM, Meyer LM. Predicting psychiatric rehospitalizations: The role of Latino versus European American ethnicity. Psychological Services. 2004;1:147–157. [Google Scholar]

- Snowden LR. Explaining mental health treatment disparities: Ethnic and cultural differences in family involvement. Culture, Medicine and Psychiatry. 2007;31:389–402. doi: 10.1007/s11013-007-9057-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ullman JB. Structural Equation Modeling. In: Tabachnick BG, Fidell LS, editors. Using Multivariate Statistics. 5th Ed Allyn Bacon; New York: 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Vaughn CE, Snyder KS, Jones S, et al. Family factors in schizophrenic relapse: Replication in California of British research on expressed emotion. Archives of General Psychiatry. 1984;41:1169–1177. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1984.01790230055009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weisman A, Lopez SR, Karno M, Jenkins J. An attributional analysis of expressed emotion in Mexican-American families with schizophrenia. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 1993;102:601–606. doi: 10.1037//0021-843x.102.4.601. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wing JK, Cooper JE, Sartorius N. The measurement and classification of psychiatric symptoms. Cambridge University Press; London: 1974. [Google Scholar]

- Yuan K-H, Lambert PL, Fouladi RT. Mardia’s Multivariate Kurtosis with Missing Data. Multivariate Behavioral Research. 2004;39:413–437. [Google Scholar]