Abstract

Background:

The male Canadian population is aging and more men will be seeking medical care for benign prostatic hyperplasia (BPH). We examined the projected increase in older Canadian males between 2005 and 2018 to evaluate urologic health-care needs.

Methods:

We used Statistics Canada population projections to derive predictions of the male population aged 50 or more from 2005 to 2018 and results from the Olmsted County Study of Urinary Symptoms to estimate numbers of males aged ≥50 with moderate to severe lower urinary tract symptoms (msLUTS) in the same period. Data from the Canadian Institute for Health Information were used to estimate the number of urologists in 2018.

Results:

The number of Canadian men aged ≥50 is projected to rise between 2005 and 2018 by 39.5% and the number with msLUTS by 41.3%. However, the number of practicing urologists in Canada in 2018 is likely to be similar to the 584 practicing in 2007. An increase in the number of urologists proportional to the increase in men aged ≥50 with msLUTS would require 799 urologists in 2018.

Interpretation:

Little opportunity exists to expand the number of trainees in urology. Other alternatives must be sought to deal with increased numbers of older men with msLUTS. Initial management of BPH has moved towards being a responsibility of primary care physicians, but they appear to view BPH as a quality-of-life issue. It is crucial that urologists work closely with primary care physicians to ensure that the management of LUTS progression is optimized.

Résumé

Introduction :

La population masculine canadienne vieillit, et de plus en plus d’hommes consulteront un médecin en raison d’une hyperplasie bénigne de la prostate (HBP). Nous avons étudié le vieillissement prévu de cette population entre 2005 et 2018 afin d’évaluer les besoins en soins urologiques.

Méthodologie :

À l’aide des projections démographiques de Statistique Canada, nous avons formulé des prévisions quant à la population masculine de 50 ans et plus entre 2005 et 2018; les résultats de l’étude du comté d’Olmsted sur les symptômes urinaires nous ont permis d’évaluer le nombre d’hommes de 50 ans et plus qui devraient présenter des symptômes modérés ou graves touchant les voies urinaires inférieures pendant la même période. Des données de l’Institut canadien d’information sur la santé ont permis d’évaluer le nombre d’urologues en 2018.

Résultats :

Le nombre de Canadiens de 50 ans et plus devrait augmenter de 39,5 % entre 2005 et 2018, et le nombre d’hommes présentant des symptômes modérés ou graves touchant les voies urinaires inférieures, de 41,3 %. En revanche, le nombre d’urologues pratiquant en 2018 au Canada devrait être semblable au nombre établi en 2007 (soit 584). Pour que la hausse du nombre d’urologues soit proportionnelle à la hausse du nombre d’hommes de 50 ans et plus qui présenteront des symptômes modérés ou graves touchant les voies urinaires inférieures, il faudrait que ce nombre atteigne 799 en 2018.

Conclusion :

Il est peu probable que le nombre de médecins se spécialisant en urologie augmente. D’autres solutions doivent donc être mises de l’avant afin de faire face au nombre croissant d’hommes âgés au prise avec des symptômes modérés ou graves touchant les voies urinaires inférieures. La prise en charge initiale de l’HBP incombe maintenant aux médecins de premiers recours, mais ces derniers semblent considérer l’HBP comme un problème de qualité de vie. Il est primordial que les urologues collaborent étroitement avec les médecins de soins primaires pour assurer une prise en charge optimale des symptômes touchant les voies urinaires inférieures.

Introduction

As a man matures, his prostate gland goes through two main periods of growth. The first occurs during early puberty when the prostate doubles in size. The second growth phase starts around age 25 and continues slowly for many years. This growth usually does not cause problems until late in life, but can result in clinical benign prostatic hyperplasia (BPH). Symptoms of BPH are rarely seen before age 40, but more than half of men in their 60s and as many as 90% of men in their 70s and 80s have some symptoms.1

The male Canadian population is aging. From 2008 onward, the leading edge of the baby boom generation, those born between 1947 and 1966,2 moved into their 60s, while its youngest members edged into their 40s. Some members of this generation seem to think they are special, but the main exceptional fact about baby boomers is that they constitute almost one-third of the Canadian population, a larger proportion than in the other three countries (Australia, New Zealand and the United States) that experienced the baby boom effect.

We examined the projected increase in Canadian males between 2005 and 2018 with the aim of identifying the potential increase in the need for medical care for BPH and the number of urologists available to satisfy this need. We also assessed actual and projected changes in the number of primary care physicians.

Methods

Based on the 2005 Canadian population, Statistics Canada has projected the national and provincial populations to 2031.3 Using varying estimates of fertility, life expectancy, immigration and interprovincial migration, the agency developed six scenarios for its predictions. The most important one is the “medium growth, medium migration trends” scenario, which is used by Statistics Canada in its own analyses. In previous projections, medium scenarios have been found to be close to reality.3 Data from the medium scenario were used to derive predictions of the male population aged 50 or more from 2005 to 2018; for the years where Statistics Canada does not provide an estimate, linear interpolation was used.

Clinically, BPH is distinguished by the progressive development of lower urinary tract symptoms (LUTS). Results from the Olmsted County Study of Urinary Symptoms, a survey of men residing in the county around the Mayo Clinic, showed a prevalence of moderate to severe LUTS (msLUTS) of 33%, 41% and 46% in men in their sixth, seventh, eighth and older decades of life.4,5 As the severity of LUTS increases, the greater is the likelihood that medical treatment will be sought and, consequently, we focused our analysis on men with msLUTS, rather than men with any degree of LUTS. The Olmsted County Study data, together with the Statistics Canada population predictions, were used to estimate the number of Canadian males aged 50 or more with msLUTS between 2005 and 2018.

Annual data on the number of physicians active in Canada between 1999 and 2007 are available online from the Canadian Institute for Health Information (CIHI).6 The numbers of active physicians are tabulated by several characteristics, such as age, sex, province and specialty, including urology. While CIHI acknowledges that the data are not perfect depending, for example, on whether one includes trainees, semi-retired physicians or physicians serving special populations such as the military, they are widely accepted as reliable. We used these data to project the number of urologists to 2018 using linear regression and also estimated the number of urologists needed to maintain the status quo for the average number of males aged 50 and older estimated to have msLUTS per urologist. In addition, we compared trends in the numbers of urologists and family physicians.

Results

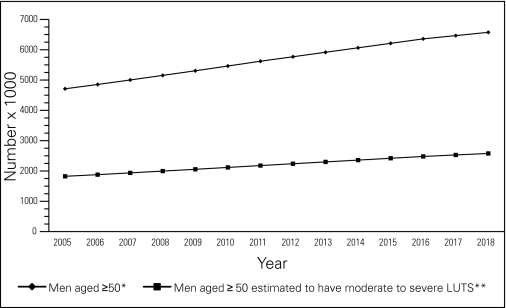

The number of Canadian men aged 50 or more was 4.712 million in 2005 (29.5% of the total male population) and this group is projected to rise to 6.574 million by 2018 (37.1% of the total male population), a 39.5% increase (Fig. 1). The number of men aged 50 and older estimated to have msLUTS in 2005 was 1.824 million. By 2018, this number is predicted to grow to 2.578 million, a rise of 41.3%.

Fig. 1.

Predicted numbers of men aged ≥50 and men aged ≥50 with moderate to severe lower urinary tract symptoms. *Statistics Canada “medium growth, medium migration trends” scenario3 **Estimated from the Olmsted County Study of Urinary Symptoms.4,5

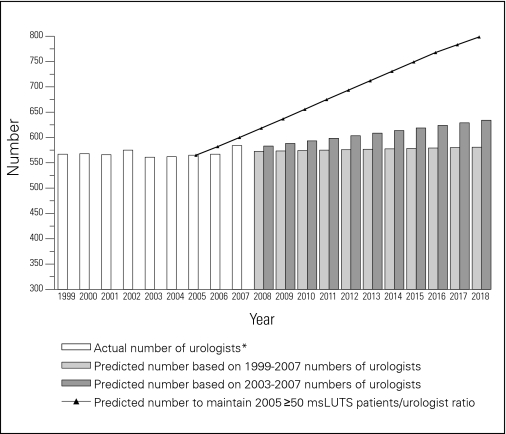

The CIHI data on the number of urologists in practice between 1999 and 2007 show small variation from a low of 561 in 2003 to a high of 584 in 2007. These data were used in a linear regression analysis to project the number of urologists to 2018 (Fig. 2), which would be 581. Since there was a small increase in the number of urologists between 2003 and 2007 from 561 to 584, we also used these figures in a linear regression analysis to provide an alternative, somewhat more aggressive, prediction of 634 in 2018.

Fig. 2.

Actual and predicted numbers of urologists, and number predicted to maintain 2005 patients/urologist ratio. *From Canadian Institute for Health Information.6

Based on the number of urologists in Canada in 2005, the average number of men 50 and older estimated to have msLUTS per urologist was 3229. With an increase of 41.3% in the estimated number of men aged 50 and older with msLUTS by 2018, a proportional rise in the number of urologists to 799 would be required to maintain the 2005 status quo in 2018.

The average number of men aged 50 or more estimated to have msLUTS per urologist in 2005 for Canada as a whole hides variation across the provinces (Table 1). The number varied from 2176 in New Brunswick to 5356 in Newfoundland and Labrador. To maintain the 2005 figure in 2018, the number of urologists would need to rise between 25% in Saskatchewan and 53% in Alberta. The 2005 average number in Ontario and Quebec was just over 3000. The number of urologists needed to achieve this value in each province ranges from no change in New Brunswick to an increase of 133% in Newfoundland and Labrador (Table 1).

Table 1.

Number of urologists in 2005 and projections to 2018

| No. of urologists in 20056 | Estimated no. of men aged ≥50 with msLUTS* per urologist in 2005 | No. of urologists needed in 2018 to maintain 2005 patient ratio | % increase over 2005 | No. of urologists needed in 2018 to achieve Ontario 2005 patient ratio | % increase over 2005 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Canada | 565 | 3229 | 799 | 41 | 858 | 52 |

| British Columbia | 67 | 3849 | 95 | 42 | 122 | 82 |

| Alberta | 45 | 3571 | 69 | 53 | 82 | 82 |

| Saskatchewan | 12 | 4803 | 15 | 25 | 24 | 100 |

| Manitoba | 17 | 3823 | 23 | 35 | 29 | 71 |

| Ontario | 228 | 3006 | 331 | 45 | 331 | 45 |

| Quebec | 150 | 3003 | 204 | 36 | 204 | 36 |

| New Brunswick | 21 | 2176 | 28 | 33 | 21 | 0 |

| Nova Scotia | 17 | 3381 | 23 | 35 | 26 | 53 |

| Prince Edward Island | 2 | 4153 | 3 | 50 | 4 | 100 |

| Newfoundland and Labrador | 6 | 5356 | 8 | 33 | 14 | 133 |

Average number of men aged ≥50 estimated to have moderate to severe LUTS. LUTS = lower urinary tract symptoms; msLUTS = moderate to severe lower urinary tract symptoms.

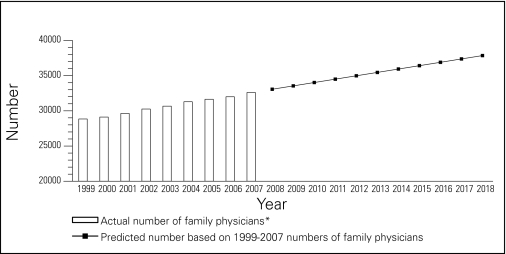

In contrast to the generally flat trend in the number of urologists, the number of family physicians increased linearly between 1999 and 2007 from 28 838 to 32 598, an increase of 13.0% (Fig. 3). If this trend continued to 2018, the number of family physicians would be 37 844, a further 16.1% increase.

Fig. 3.

Actual and predicted numbers of family physicians. *From Canadian Institute for Health Information.6

Discussion

This analysis starkly demonstrates that, as the leading edge of the baby boomer generation moves into their 70s and its youngest members into their 50s in 2018, there will have been a steep increase in the number of Canadian men aged 50 or more and a somewhat sharper rise in those with msLUTS who are likely to require urologic care. However, even under a model where the number of urologists expands to 634, this only represents an increase of 8.6% over the 2007 figure of 584 urologists, whereas a 36.8% increase would be needed simply to maintain the patients to urologist ratio that existed in 2005, a level that was already stretching the system.7

Since 255 (43.7%) of the 584 urologists in practice in 2007 graduated with their MD degrees more than 25 years earlier, an increase in the number of urologists in the next 10 years seems highly unlikely. Moreover, young physicians tend to seek greater balance between professional and non-professional activities, which implies working less hours than physicians have in the past.8 Simply maintaining the present number of urologists to 2018 may be difficult, but no increase would mean that there would be a deficit of nearly 220 (almost 30%) below the number needed to maintain the 2005 estimated number of men aged 50 and older with msLUTS per urologist.

While the number of Canadian urologists was relatively stable between 1999 and 2007, the number of family physicians increased by 13%. The number of urologists is likely to remain the same or even decline over the next decade, whereas if the trend in family physicians were to be maintained, their number would increase by another 16% by 2018. Between 1999 and 2007, the number of all Canadian physicians rose by 12%.6 Important factors behind this growth have been increases in enrolment in Canadian medical schools and the number of MD degrees awarded in these years of 51% and 35%, respectively.9 However, it is questionable whether this growth in new medical graduates is sustainable over the next 10 years without a major expansion in resources for training and physical space in which to do it. Unless there is a large increase in foreign-trained physicians, whose numbers rose between 1999 and 2007 by only 6%,6 the strong linear growth in the number of family physicians is likely to falter.

The predictions presented here are based on Statistics Canada population projections and data on msLUTS prevalence obtained in the Olmsted County Study of Urinary Symptoms.3–5 Statistics Canada has significant experience with such estimates and has produced predicted values in the past that closely match the actual numbers. The Olmsted County Study is well-respected, but it was conducted in the early 1990s and the prevalence of msLUTS in Canada over 10 years later may be different. Linear regression analysis was used to predict numbers of urologists and family physicians based on data available for 1999 to 2007, but this may be an oversimplification of potential trends in these numbers, especially for family physicians.

We have also assumed that the treatment of msLUTS over the next 10 years will remain largely within the domain of urologists. Although pharmacologic therapy has become first-line treatment for BPH and moved responsibility for the initial management of BPH into the primary care setting,7,10 it is reasonable to assume that urologists will retain their role in the treatment of msLUTS, although new surgical technologies that can be used in the outpatient setting may enable them to treat more patients.11,12 Another assumption is that the treatment of BPH/LUTS will remain the same over the next 10 years. Treatments may emerge that further accelerate the management of BPH and render long-term medical therapy unnecessary. To date, these therapies are still being introduced mainly in patients unresponsive to medical therapy and have not been widely adopted. Obviously, the need for long-term medical therapy would likely decrease significantly if a treatment becomes available that is simple, low risk and with long-term efficacy.

Conclusion

Within the framework of these pragmatic assumptions, the findings of our analysis point to steep increases in older men with msLUTS in Canada, together with a significant shortfall in the number of urologists to provide health care to these patients. While young physicians should be encouraged to enter the specialty, there is little opportunity to expand the number of trainees in urology. The anticipated shortage of urologists in Canada is likely to require primary care physicians to manage more men with LUTS and the increasing numbers of family physicians should, at least in the short term, allow them to take on this responsibility. However, primary care physicians appear to view BPH/LUTS as a quality of life issue rather than a progressive condition10,13 making it crucial for urologists to work closely with them to ensure that the management of LUTS progression is optimized.

Footnotes

Competing interests: Dr. Rawson is a full-time employee of GlaxoSmithKline. Dr. Saad is an advisory board member and speaker for GlaxoSmithKline.

This paper has been peer-reviewed.

References

- 1.National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases Prostate enlargement: benign prostatic hyperplasia Bethesda, MD: Department of Health and Human Services; 2006. Available at: http://kid-ney.niddk.nih.gov/kudiseases/pubs/prostateenlargement Accessed February 24, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Foote DK. Boom, Bust and Echo: Profiting from the demographic shift in the 21st century. Toronto: Footwork Consulting; 2004. pp. 24–8. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Belanger A, Martel L, Caron-Malenfant E.Population projections for Canada, provinces and territories, 2005–2031 Ottawa: Minister of Industry (Statistics Canada)2005. Available at: http://www.statcan.gc.ca/pub/91-520-x/91-520-x2005001-eng.pdf Accessed February 24, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chute CG, Panser LA, Girman CJ, et al. The prevalence of prostatism: a population-based survey of urinary symptoms. J Urol. 1993;150:85–9. doi: 10.1016/s0022-5347(17)35405-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wei JT, Calhoun E, Jacobsen SJ. Urologic Diseases in America project: benign prostatic hyperplasia. J Urol. 2005;173:1256–61. doi: 10.1097/01.ju.0000155709.37840.fe. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Supply, distribution and migration of Canadian physicians, 1999, 2000, 2001, 2002, 2003, 2004, 2005, 2006, 2007 Ottawa: Canadian Institute for Health Information; 2000, 2001, 2002, 2003, 2004, 2005, 2006, 2007, 2008. Available at: http://secure.cihi.ca/cihiweb/dispPage.jsp?cw_page=AR_14_E Accessed February 24, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Tanguay S, Awde M, Brock G, et al. Diagnosis and management of benign prostatic hyperplasia in primary care. Can Urol Assoc J. 2009;3(Suppl2):S92–100. doi: 10.5489/cuaj.1116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Crossley TF, Hurley J, Jeon SH. Physician labour supply in Canada: a cohort analysis. Health Econ. 2009;18:437–56. doi: 10.1002/hec.1378. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Canadian medical education statistics. 2008 Ottawa: Association of Faculties of Medicine of Canada; 2008. Available at: http://www.afmc.ca/pdf/cmes2008.pdf Accessed February 24, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Miner MM. Primary care physician versus urologist: how does their medical management of LUTS associated with BPH differ? Curr Urol Rep. 2009;10:254–60. doi: 10.1007/s11934-009-0042-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Stafinski T, Menon D, Harris K, et al. Photoselective vaporization of the prostate for the treatment of benign prostatic hyperplasia. Can Urol Assoc J. 2008;2:124–34. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Elliott SP, Sweet RM. Contemporary surgical management of benign prostatic hyperplasia: what do recent trends imply for urology training? Curr Prostate Rep. 2009;7:19–24. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Quinlan MR, O’Daly BJ, O’Brien MF, et al. The value of appropriate assessment prior to specialist referral in men with prostatic symptoms. Ir J Med Sci. 2009;178:281–5. doi: 10.1007/s11845-009-0337-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]