INTRODUCTION

Gastrointestinal manifestations are common in patients with systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE), and the incidence of these conditions varies according to the methods of evaluation and the type of manifestation; the incidence of gastrointestinal manifestations varied between 15% and 75% in the majority of previously published studies.1,2 The clinical picture may vary from minor symptoms, such as oral ulcers, dysphasia, nausea and vomiting, to more serious conditions, including pancreatitis, hepatitis and mesenteric vasculitis.

Mesenteric vasculitis is uncommon among gastrointestinal complications (2.2–9.7%) but may cause enhanced complications and mortality if it is not carefully diagnosed and promptly treated.1

Gastrointestinal vasculitis is characterized by ischemia of the digestive tract; this ischemia is caused by the deposition of circulating immune complexes. Clinically, this vasculitis presents with diffuse abdominal or colonic pain, vomiting and fever. The physical examination demonstrates abdominal pain upon touching, which may indicate peritoneal irritability. Gastrointestinal vasculitis does not usually appear as an isolated manifestation but is generally associated with other clinical manifestations of the illness and SLE activity. Consequently, the Systemic Lupus Erythematosus Disease Activity Index (SLEDAI) score is generally high in patients with gastrointestinal vasculitis.1,3–7

In the present study, we describe an unusual case of a lupus patient with mesenteric vasculitis who presented without any evidence of the illness, which is usually found in this clinical situation.

CASE DESCRIPTION

In 1986, a 45-year-old female with two sisters who had suffered and died from SLE presented with symptoms of fatigue, fever, alopecia, facial edema, Raynaud’s phenomenon, malar rash, polyarthritis of the great and small joints, leukopenia and lymphopenia. The patient had positive antinuclear antibody levels > 1:200, with a speckled pattern, and also had positive anti-ENA and anti-Sm antibodies. Thus, she was diagnosed with SLE. Treatment was initiated with chloroquine diphosphate (250 mg/day) and prednisone (30 mg/day). All manifestations regressed, except for the leukopenia and lymphopenia. The leukopenia continued and was not linked with the illness. The results of a myelogram were normal.

In January, 2001, the patient visited the clinic complaining of abdominal pain, nausea, anorexia, vomiting and abdominal distension. At the time, the patient was only receiving prednisone (5 mg/day) and was suffering from arterial hypotension. After expanding the vascular volume with crystalloids, she promptly recovered. After several days, she returned to the hospital for follow up but did not present with any abdominal pain. Physical examination showed the patient to be without fever, any evidence of cutaneous lesions, arthritis or cutaneous vasculitis, and her abdomen was normal. On that occasion, laboratory tests showed the following: hemoglobin 10.7 g/dL, hematocrit 32%, leukocytes 2,600/mL (neutrophils, – 1,700/mL, lymphocytes – 600/mL), platelets 177,000/mL, amylase 156 U/L (normal value < 100 U/L), lipase 419 U/L (normal value < 190 U/L), aspartate amino transferase (AST) 15 U/L, alanine amino transferase (ALT) 25 U/L, gamma glutamyl transferase (GGT) 21 U/L, alkaline phosphatase 86 U/L, bilirubin 0.9 mg/dL and albumin 4.1 g/L. The urine examination showed isolated proteinuria without hematuria, leukocyturia or cylindruria. The protein quantity in urine collected over a 24-hour period was 1.48 g. Urea (31 mg/dL) and creatinine (0.9 mg/dL) levels were normal. The erythrocyte sedimentation rate was 26 mm/1st hour. C-reactive protein, gamma-globulin and complement were within the normal ranges. Anti-dsDNA antibodies, anti-cardiolipin IgG and IgM, lupus anticoagulant, anti-beta-2-glycoprotein I IgG and IgM, cryoglobulinemia, and anti-endothelial cell antibodies were not detected. The SLEDAI score on this occasion was low (two) because of the new proteinuria; the leukopenia was already chronic. Because the complement levels were normal, anti-dsDNA antibodies were not present, urine sedimentation was inactive, and creatinine levels and blood pressure were normal, enalapril was initiated and the abdominal pain was investigated. An abdominal x-ray was normal, and an abdominal ultrasound verified a right pyelo-ureteral distention without any evidence of nephrolithiasis. These results were confirmed by an abdominal computerized tomography (CT) scan. The patient was well and was discharged for a follow up at the outpatient clinic.

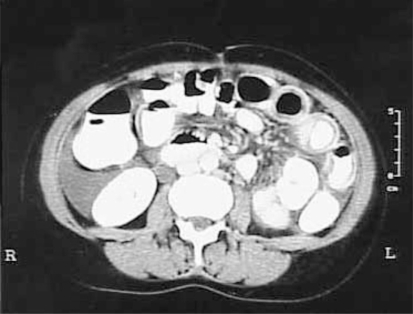

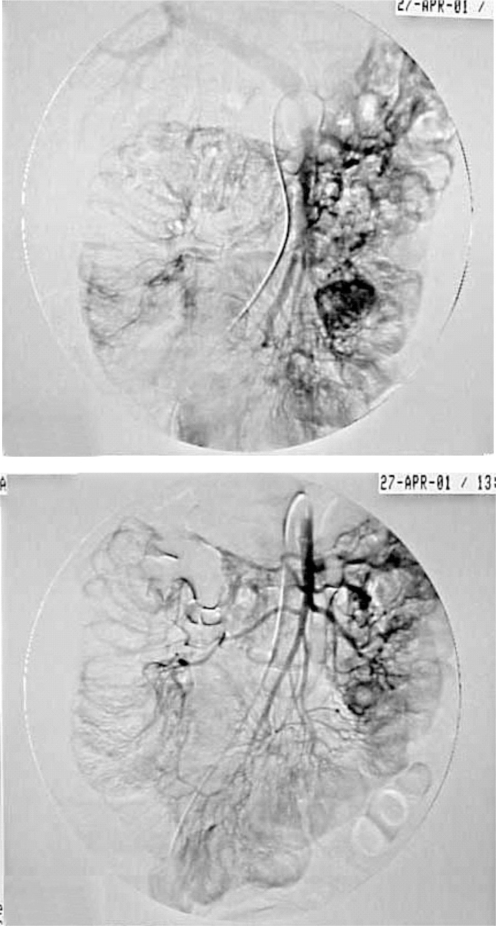

The patient continued to suffer from sporadic episodes of light abdominal pain and was again hospitalized in April, 2001. At this time, she presented sensitivity to abdominal touching, without peritonism. She did not show any evidence of clinical SLE activity. The laboratory tests showed increased levels of the pancreatic enzymes amylase (135 U/L) and lipase (469 U/L). Urine analysis showed no alterations. Complement levels were reduced, with undetectable C4 and C3. Anti-dsDNA antibodies were present (1:80), and at this time, her SLEDAI was four. The new abdominal CT showed discrete ascites and diffuse jejunoileal thickening, with the “target sign,” suggestive of an ischemic process that takes place in the microvasculature (Figure 1). Radiological examination of intestinal transit showed a delay in the transit time in the small bowel and distension of the handles, suggesting an intestinal occlusion. A digital arteriography scan was performed and showed microaneurysmatic distal distensions and zones of hypervascularization, suggestive of vasculitis in the superior mesenteric artery territory (Figure 2); the proximal region of this artery, the celiac trunk and the inferior mesenteric artery were normal. In its delayed phase, right hydronephrosis was evident (Figure 3). Thus, the diagnosis of mesenteric vasculitis was confirmed.

Figure 1.

Abdominal computerized tomography showing dilated bowel, focal or diffuse bowel wall thickening, and abnormal bowel wall enhancement (a double halo or target sign).

Figure 2.

Digital arteriography showing hypervascularization and multiple microaneurysms in the branches of the superior mesenteric artery, which is compatible with vasculitis.

Figure 3.

Delayed arteriography phase showing hydronephrosis on the right pyelocaliceal renal system.

Methylprednisolone (50 mg/day, intravenous) was initiated, and the patient showed clinical improvement and became asymptomatic after four days. A new abdominal CT was performed to evaluate her progress, and the results were normal. After two weeks of corticosteroid therapy, intravenous cyclophosphamide (1 g) was given monthly for one year. The patient had a gradual and complete control of illness, thereby allowing the tapering of corticosteroid therapy. She also received cyclophosphamide pulse therapy twelve times in a period of one year. Currently, she is well and in SLE remission.

DISCUSSION

Mesenteric vasculitis is an extremely serious complication and is highly lethal (50%)2 during the course of SLE. Quickly recognizing mesenteric vasculitis changes the prognosis, as the fast introduction of therapy changes the course of the illness.

From a histopathological point of view, mesenteric vasculitis is an inflammatory process of the vascular wall, with fibrinoid necrosis that drives regional ischemia and dysfunction of the intrinsic intestinal musculature. This condition is characterized by the deposition of complement, fibrinogen and immune complexes.6

Clinically, mesenteric vasculitis can present as abdominal angina, pain in the colon, distension and pseudo-blockage. Laboratory tests show increased inflammatory symptoms. The x-rays and abdominal transit results can be compatible with bowel pseudo-obstruction, as in the present case.

Abdominal CT with contrast is employed to help with the diagnosis and was used in the present case to show favorable progress. In 1997, Ko et al.8 demonstrated the importance of CT as a basic and decisive diagnostic instrument in lupus patients with abdominal pain. The authors studied 15 SLE patients for up to 4 days from the initiation of pain. Of 15 patients, 11 patients presented signs that suggested mesenteric vasculitis; the prominent mesenteric vessels were pale (comb sign), the focal or diffuse handles showed distension and the ascites and intestinal wall thickening were indicated by a double halo (target sign). The authors emphasized that the comb sign reflects an active vascular inflammatory reaction and can be extremely useful for confirming the diagnosis of mesenteric vasculitis in an initial phase of the disease. An early diagnosis is associated with a better prognosis.8 Other authors have also confirmed these findings.9

The vasculitis can be demonstrated by mesenteric vasculature arteriography, which shows the irregularity of the vascular branches, mainly in the region of the superior mesenteric artery. Angioresonance and scintigraphy with gallium are methods that can also be used to do the diagnosis ofmesenteric vasculitis. Rheumatic evaluation and follow up with a surgeon are extremely important so the patient can avoid abdominal surgical emergencies when the abdominal tomography indicates the presence of vasculitis. In addition, other diverse abdominal pathologies must be excluded, such as acute cholecystitis, appendicitis, intestinal occlusion, a perforated peptic ulcer, pancreatitis, bacterial peritonitis and intestinal infection by cytomegalovirus, tuberculous colitis, pelvic inflammatory illness and pyelonephritis. Causes of intestinal vascular ischemia, such as atherosclerosis, embolism and anti-phospholipids syndrome, must also be excluded.10

The absence or delayed appearance of clinical manifestations associated with lupus, the production of anti-dsDNA antibody and the reduction of complement in the present patient makes this case note-worthy. The literature affirms that mesenteric vasculitis occurs in individuals showing lupus activity in other organs and systems, generally with a SLEDAI above eight.11,12 In the current patient’s situation, evaluation by non-invasive imaging was imperative because emergency abdominal surgery must be readily excluded in the presence of a low SLEDAI score. In fact, among 51 patients with SLE who presented with acute abdominal pain, the 19 patients with mesenteric vasculitis had a SLEDAI score higher than that of the other 14 lupus patients with acute abdominal pain unrelated to the illness (17.5 versus 8.2). The authors emphasized the importance of using laparotomy in lupus patients who presented with acute abdominal pain and a higher SLEDAI index.11

The hydronephrosis as found in our patient was previously described in the literature. Mesenteric vasculitis is associated with pyelo-ureteral smooth musculature alterations in 67% of cases involving pyelo-ureteral hydronephrosis.13 Treatment improves the prognosis, and methylprednisolone (1 mg/kg/ day) is employed along with intestinal rest. Generally, a quick and effective response is achieved with this treatment. In those cases that clinical response is not achieved, surgical re-evaluation is mandatory to remove the bowel segment having ischemia or intestinal perforation away from the digestive tract.2 Pulse therapy with methylprednisolone may be required in some cases. The use of immunosuppressive drugs generally manages disease, but no controlled and randomized studies have been performed to demonstrate which drugs are most effective or what the best application scheme is. In the present case, cyclophosphamide was chosen due to the gravity of the clinical picture.

The present case calls attention to the presence of mesenteric vasculitis in lupus patients without systemic activity or excessive illness. The use of CT scans in lupus patients with abdominal pain is basic, can exclude surgical pathologies and aids in making the diagnosis of intestinal vasculitis.

Acknowledgments

Carvalho JF received grants from the Federico Foundation and CNPq (300665/2009-1).

REFERENCES

- 1.Hallegua DS, Wallace DJ. Gastrointestinal manifestations of systemic lupus erythematosus. Cur Op Rheumatol. 2000;12:379–85. doi: 10.1097/00002281-200009000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hoffman BI, Warren AK. The gastrointestinal manifestations of systemic lupus erythematosus: a review of the literature. Sem Arthritis Rheum. 1980;9:237–44. doi: 10.1016/0049-0172(80)90016-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wallace DJ. Gastrointestinal manifestations and related liver and biliary disorders. Dubois’Lupus Erythematosus. (4th ed) 1993;42:410–7. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Mazin SA, Marvin AM. Evaluation of abdominal pain in systemic lupus erythematosus. Am J Surg. 1998;176:291–4. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9610(98)00155-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Turner HE, Myszor MF, Bradlow A, David J. Lupus or lupoid hepatitis with mesenteric vasculitis. Br J Rheumatol. 1996;35:1309–11. doi: 10.1093/rheumatology/35.12.1309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ju JH, Min JK, Jung CK, Oh SN, Kwok SK, Kang KY, et al. Lupus mesenteric vasculitis can cause acute abdominal pain in patients with SLE. Nat Rev Rheumatol. 2009;5:273–81. doi: 10.1038/nrrheum.2009.53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kwok SK, Seo SH, Ju JH, Park KS, Yoon CH, Kim WU, et al. Lupus enteritis: clinical characteristics, risk factor for relapse and association with anti-endothelial cell antibody. Lupus. 2007;16:803–9. doi: 10.1177/0961203307082383. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ko SF, Lee TY, Cheng TT, Ng SH, Lai HM, Cheng YF, et al. CT findings at lupus mesenteric vasculitis. Acta Radiologica. 1997;38:115–20. doi: 10.1080/02841859709171253. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Byun JH, Ha HK, Yu YS, Min JK, Park SH, Kim HY, et al. CT features of Systemic Lupus Erythematosus in patients with acute abdominal pain: emphasis on ischemic bowel disease. Radiology. 1999;211:203–9. doi: 10.1148/radiology.211.1.r99mr17203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Grimbacher B, Huber M, von Kempis J, Kalden P, Uhl M, Köhler G, et al. Successful treatment of gastrointestinal vasculitis due to systemic lupus erythematosus with intravenous pulse cyclophosphamide: a clinical case report and review of the literature. Br J Rheumatol. 1998;37:1023–8. doi: 10.1093/rheumatology/37.9.1023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Mazin SA, Marvin AM. Evaluation of abdominal pain in systemic Lupus erythematosus. Am J Surg. 1998;176:291–4. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9610(98)00155-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Buck AC, Serebro LH, Quinet RJ. Subacute abdominal pain requiring hospitalization in a systemic lupus erythematosus patient: a retrospective analysis and review of the literature. Lupus. 2001;10:491–5. doi: 10.1191/096120301678416051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Mok MY, Wong RW, Lau CS. Intestinal pseudo-obstruction in systemic lupus erythematosus: an uncommon but important clinical manifestation. Lupus. 2000;9:11–8. doi: 10.1177/096120330000900104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]