Abstract

Background Most diarrhoeal deaths can be prevented through the prevention and treatment of dehydration. Oral rehydration solution (ORS) and recommended home fluids (RHFs) have been recommended since 1970s and 1980s to prevent and treat diarrhoeal dehydration. We sought to estimate the effects of these interventions on diarrhoea mortality in children aged <5 years.

Methods We conducted a systematic review to identify studies evaluating the efficacy and effectiveness of ORS and RHFs and abstracted study characteristics and outcome measures into standardized tables. We categorized the evidence by intervention and outcome, conducted meta-analyses for all outcomes with two or more data points and graded the quality of the evidence supporting each outcome. The CHERG Rules for Evidence Review were used to estimate the effectiveness of ORS and RHFs against diarrhoea mortality.

Results We identified 205 papers for abstraction, of which 157 were included in the meta-analyses of ORS outcomes and 12 were included in the meta-analyses of RHF outcomes. We estimated that ORS may prevent 93% of diarrhoea deaths.

Conclusions ORS is effective against diarrhoea mortality in home, community and facility settings; however, there is insufficient evidence to estimate the effectiveness of RHFs against diarrhoea mortality.

Keywords: Oral rehydration solution, oral rehydration therapy, recommended home fluids, diarrhoea, child, systematic review, meta-analysis

Background

Diarrhoeal diseases are a leading cause of mortality in children aged <5 years, accounting for 1.7 million deaths annually.1 Because the immediate cause of death in most cases is dehydration, these deaths are almost entirely preventable if dehydration is prevented or treated. Until 1970s, intravenous (IV) infusion of fluids and electrolytes was the treatment of choice for diarrhoeal dehydration, but was expensive and impractical to use in low-resource settings. In 1960s and 1970s, physicians working in South Asia developed a simple oral rehydration solution (ORS) containing glucose and electrolytes that could be used to prevent and treat dehydration due to diarrhoea of any aetiology and in patients of all ages.2–8

At the time ORS was developed, placebo-controlled trials would have been unethical given the efficacy of IV therapy, and to our knowledge none exists. The randomized controlled trials (RCTs) of ORS conducted to confirm its efficacy instead used a comparator such as IV therapy or alternative formulations of ORS. Similarly, studies conducted in community settings to assess the effectiveness of ORS did not actively withhold ORS from the comparison area but instead evaluated the effectiveness of promotional campaigns or alternative delivery systems compared with routine health system delivery.

In 1970s, the World Health Organization (WHO) recommended that an ORS formulation with total osmolarity 311 mmol/l be used for prevention and treatment of diarrhoeal dehydration. However, alternative formulations continued to be investigated in an attempt to develop an ORS formulation that would decrease stool output or have other clinical benefits. These efforts led, in 2004, WHO to recommend low osmolarity ORS (with total osmolarity of 245 mmol/l and reduced levels of glucose and sodium), which was associated with reduced need for unscheduled IV therapy, decreased stool output and less vomiting when compared with the original formulation.9,10

As countries launched diarrhoeal disease control programmes to roll out ORS, they faced difficulties in ensuring access and achieving high coverage levels, in part due to inadequate manufacturing capacity. In an effort to improve provision of fluids in early diarrhoea episodes to prevent the development of dehydration, diarrhoeal disease control programmes promoted the use of additional fluids and home-made solutions such as rice water and sugar salt solution [collectively referred to as recommended home fluids (RHFs)].11,12 RHFs were eventually incorporated into the WHO recommendations for prevention of dehydration. Unfortunately, over the years, programmes have combined ORS and RHFs into a general and poorly defined oral rehydration therapy (ORT) category in which the respective roles of ORS and RHFs are not well delineated.

Recent Cochrane reviews have estimated the efficacy of ORS compared with IV therapy, and reduced osmolarity ORS compared with original ORS, against treatment failure.10,13 Additionally, in 1998, a Cochrane review examined the effect of rice-based, compared with glucose-based, ORS on stool output and duration of diarrhea.14 However, these reviews focused on RCTs of ORS conducted in hospitals or clinical settings and did not examine mortality as an outcome or the broader category of RHFs as an intervention. To our knowledge, there are no systematic reviews or corresponding meta-analyses assessing the effect of ORS or RHFs on diarrhoea-specific mortality. We present evidence from systematic reviews and meta-analyses drawing upon data from community- and facility-based studies to estimate the effectiveness of ORS, and, separately, RHFs on diarrhoea morbidity and mortality in children aged <5 years. We then correlate the effectiveness estimates with achieved coverage levels to generate an estimate of the effect of each intervention on cause-specific mortality.

Methods

Per CHERG Guidelines, we systematically reviewed published literature from PubMed, the Cochrane Libraries, and the WHO Regional Databases to identify studies examining the effect of oral rehydration strategies on diarrhoea morbidity and mortality in children aged <5 years. Search terms included combinations of diarrhea, dysentery, rotavirus, fluid therapy, oral rehydration solution, oral rehydration therapy, recommended home fluid and sugar salt solution. We limited the search to studies that included children aged <5 years and studies in English, French, Spanish, Portuguese and Italian.

Inclusion/exclusion criteria and definitions

For the purposes of this review, we defined and reviewed three categories of oral rehydration strategies: ORS, RHFs and ORT. We defined ORS as an electrolyte solution containing sodium, chloride, potassium, bicarbonate or citrate and glucose or another form of sugar or starch. Formulations containing small amounts of other minerals, such as magnesium, were included in this category, but solutions containing amino acids such as glycine or alanine were excluded. We also excluded solutions containing zinc, because it was not possible to separate the effects of ORS and zinc on diarrhoea morbidity. Both reduced osmolarity ORS (total osmolarity ≤250 mmol/l, per Hahn10) and higher osmolarity ORS (up to 370 mmol/l) were included in our review.

For RHFs, we included all possible home fluid alternatives in our review, including sugar–salt solution, cereal–salt solution, rice–water solution and additional fluids such as plain water, juice, tea or rice water. If the study intervention was promotion or provision of both ORS and RHF in the same area and the effects and coverage estimates of the two interventions could not be separated, we categorized it as ORT. Such studies were generally large-scale programme evaluations.

We included quasi-experimental, pre/post, observational and randomized and cluster-randomized trials reporting any of the following outcomes for children aged <5 years: all-cause or diarrhoea-specific mortality, diarrhoea hospitalizations, referrals to hospitals or health centres for diarrhoea treatment, or treatment failure. Studies in developed countries were excluded unless conducted in a low-resource setting, such as native American reservations. Treatment failure was generally defined as the need for unscheduled IV therapy, but we accepted other definitions provided that they reflected failure of the therapy to produce or maintain clinical improvement in the subjects’ dehydration state. Studies that defined treatment failure in terms of stool volume or duration of diarrhoea were excluded.

Abstraction

We abstracted all studies meeting our acceptance criteria into standardized tables, categorized by outcome, study design and type of oral rehydration strategy. Abstracted variables included study identifiers and context, design and limitations, population, characteristics of the intervention and control and outcome measures. Based on these data, we graded each study according to the CHERG adaptation of the GRADE technique.15 Scores were decreased by half a grade for each design limitation; observational studies, including pre/post studies, received a very low grade.

Analysis

We summarized the evidence for ORS and RHFs by outcome in a separate table and graded the quality of evidence for each outcome, decreasing the score for observational study designs, heterogeneity of study outcomes or lack of generalizability of the study populations or interventions. We did not produce a summary table for ORT because our goal was to generate estimates of the individual rather than joint effectiveness of ORS and RHFs, as each has different roles in diarrhoea management. For each outcome with more than one study, we conducted both fixed and random effects meta-analyses.

Mortality

For diarrhoea-specific mortality, we included randomized, cluster-randomized and quasi-experimental studies in the meta-analysis. Observational studies (other than quasi-experimental studies) that did not control for confounding were excluded, as were case–control studies and those that did not provide an adequate estimate of coverage in the intervention arm. We defined coverage as the proportion of diarrhoea episodes in children aged <5 years for which the child received ORS or RHFs. We excluded studies in which a comparator or alternative delivery system was used in the comparison arm, because the resulting relative risk did not provide meaningful information on the effect of ORS or RHFs on diarrhoea morbidity or mortality. For ORS and, separately, RHFs, we reported the pooled relative reduction in diarrhoea-specific mortality and 95% confidence interval (CI). In the case of heterogeneity, we reported the DerSimonian–Laird pooled relative reduction and 95% CI.

Treatment failure

Observational studies and RCTs of ORS or RHFs assessing treatment failure, including those that used a comparator, were included in the meta-analysis. For included studies, instead of a relative risk, we analysed the absolute treatment failure rate for each therapy that met our inclusion criteria. We conducted separate and combined meta-analyses for RCTs and observational studies and reported the Mantel–Haenszel pooled failure rate and 95% CI, or the DerSimonian–Laird pooled failure rate and 95% CI if there was evidence of heterogeneity for each.

Hospitalization/referral

The clinical guidelines and processes for hospitalization and referral in the studies we identified were variables and often not well described. Moreover, this outcome can be confounded by differences in care-seeking or referral practices between study arms, particularly in quasi-experimental studies, and the studies included in our review did not adequately address or adjust for this possibility. Given these considerations, a meta-analysis was not appropriate for this outcome, and none was conducted.

Overall effectiveness estimate

Applying the CHERG Rules for Evidence Review,15 for each outcome, we considered the quality of the evidence, number of events and generalizability of the study population and outcome to diarrhoea-specific mortality to estimate the effects of ORS and RHFs on diarrhoea mortality in children aged <5 years.

Results

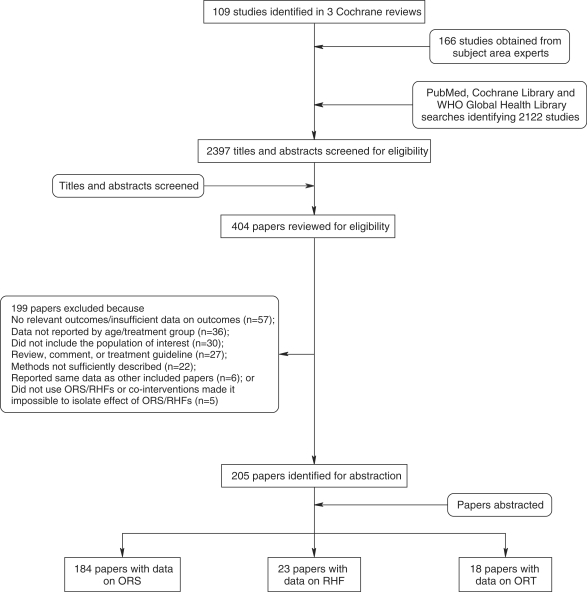

Our searches identified 2397 titles; after screening titles and abstracts, we reviewed 404 papers for our inclusion/exclusion criteria and outcomes of interest (Figure 1). We abstracted 205 papers into our final database: 184 reporting data on ORS, 23 on RHFs and 18 on ORT as defined above. For the outcomes of diarrhoea and all-cause mortality, we excluded many papers in our final database from the meta-analysis because they used observational study designs and did not control for confounding, did not report an adequate coverage indicator, had no relevant comparison group or used a case–control design. These studies are shown in Supplementary tables 1 and 2, but were not included in the meta-analyses or summary tables (Supplementary tables 1 and 2).

Figure 1.

Search process for ORS and RHFs

ORS

We identified 21 papers reporting diarrhoea-specific mortality, 3 reporting all-cause mortality, 20 reporting hospitalization/referral and 155 reporting treatment failure that met our inclusion/exclusion criteria (Supplementary table 1). Of these, three papers reporting diarrhoea mortality and 153 reporting treatment failure were included in the meta-analyses. Table 1 presents the summary characteristics of these studies and meta-analysis results by outcome.

Table 1.

Quality assessment of trials of ORS

| No. of studies |

Quality assessmenta |

Summary of findings |

Comments | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Directness |

No. of events |

Effect | |||||||

| Design | Limitations | Consistency | Generalizability to population of interest | Generalizability to intervention of interest | Intervention | Control | Relative reduction (95% CI) | ||

| Diarrhoea mortality rate: low outcome-specific quality | |||||||||

| Three18–20 | Quasi experimental (−1) | No adjustment for confounding variables (−0.5); ORS used in control arms in most cases, but at a lower rate than in intervention arms | Consistent benefit from all studies | India, Bangladesh and Burma (−0.5) | No studies used reduced osmolarity ORS | 27/11696 child-years | 41/5295 child years | 69% (51–80%) | Fixed effect meta-analysis |

| Treatment failure: moderate outcome-specific quality | |||||||||

| 153 total | RCTs and observational | No true control arm; most studies are hospital based; many observational (−0.5) | Heterogeneity from meta-analysis (−0.5) | South/Southeast Asia, Eastern Mediterranean, Latin America, North/South/East/West Africa, Eastern Europe and Apache reservations in USA | About 26 used low osmolarity ORS About 26 used rice- or cereal-based ORS | 1283/18 084 episodes | NA | 0.2%* (0.1–0.2%) | *Pooled failure rate Random effects meta-analysis |

| 10421−124 | RCTs | No true control arm; most studies hospital based | Heterogeneity from meta-analysis (−0.5) | South/Southeast Asia, Eastern Mediterranean, Latin America and North/West/East Africa | About 22 used low osmolarity ORS (total osmolarity ≤ 250 mmol/L); approximately 26 used rice- or cereal-based ORS | 734/9449 episodes | NA | 0.2%* (0.1–0.2%) | *Pooled failure rate Random effects meta-analysis |

| 49125–172 (DEC Ashley et al., Unpublished, 1980.) | Observational | No adjustment for confounding | Heterogeneity from meta-analysis (−0.5) | Latin America, South/Southeast Asia, Eastern Mediterranean, North/South/East/ West Africa, Eastern Europe and Apache reservations in USA | About four studies used low-osmolarity ORS | 549/8635 episodes | NA | 0.3%* (0.2–0.4%) | *Pooled failure rate Random effects meta-analysis |

aSee Walker et al.15 for a description of the quality assessment and grading methods.

For the outcomes of diarrhoea mortality and treatment failure, there was evidence to support the effectiveness of ORS. A fixed effect meta-analysis showed a 69% (95% CI: 51–80%) pooled relative reduction in diarrhoea mortality in communities in which ORS was promoted compared with comparison areas, with no indication of heterogeneity (Table 1). A random effects meta-analysis similarly showed a very low-pooled treatment failure rate (0.2%; 95% CI: 0.1–0.2%) for ORS. Studies reporting treatment failure were almost universally conducted in hospital or clinic settings.

For the outcome of hospitalization/referral, 6 of 20 studies included a relevant comparison arm: five quasi-experimental studies and one pre/post study. Of the five quasi-experimental studies, two did not clearly report the coverage achieved, one provided regular home visits by nurses and a health education component in the intervention but not comparison arms and none discussed care-seeking practices in intervention and control areas. The outcomes of these studies were mixed, with two studies reporting increases in hospitalization in the intervention relative to the control area, whereas the other studies reported 47–57% relative decrease in hospitalization and 29–89% relative decreases in referrals to health centres in the intervention areas.

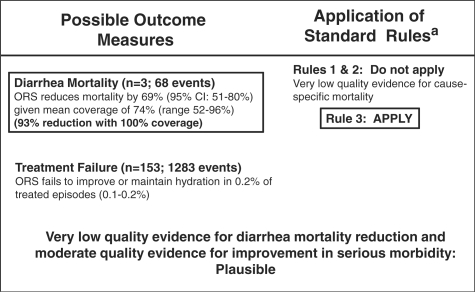

We applied the CHERG Rules for Evidence Review15 to the evidence presented in Table 1. We used the pooled effect size for diarrhoea mortality, as it was more conservative than the effect size for severe morbidity (treatment failure). The mean and median coverage levels in the intervention arms of the diarrhoea mortality studies were 74%; assuming a linear relationship between coverage and mortality reduction, at 100% coverage a 93% relative reduction in diarrhoea mortality would be expected (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Application of standardized rules for choice of final outcome to estimate effect of ORS on the reduction of diarrhoea mortality. aSee Walker et al.15 for a description of the CHERG Rules for Evidence Review

RHFs

We identified and abstracted five studies reporting diarrhoea mortality, one reporting all-cause mortality, five reporting hospitalization or referral and 14 reporting treatment failure for RHFs (Supplementary table 2). For the outcomes of diarrhoea and all-cause mortality, no studies met the required study quality criteria for inclusion in the meta-analyses.

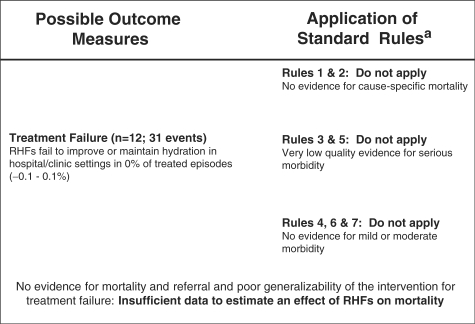

We included 12 studies in the meta-analysis of treatment failure and found a pooled failure rate of 0% (95% CI: −0.1 to 0.1%) (Table 2). However, each of these studies included dehydrated patients and was conducted in a hospital or clinic setting. Studies assessed sugar solution and sugar- or cereal–salt solutions; none assessed other RHFs such as plain water or rice water. Due to the low quality of evidence (i.e. no community-based studies) for serious morbidity and the lack of well-designed studies assessing the effect of RHFs on mortality, we did not estimate an effect of RHFs on diarrhoea mortality (Figure 3).

Table 2.

Quality assessment and summary outcomes of trials of RHFs

|

Quality assessmenta |

Summary of findings |

Comments | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Directness |

No of events |

Effect | |||||||

| No of studies | Design | Limitations | Consistency | Generalizability to population of interest | Generalizability to intervention of interest | Intervention | Control | Relative reduction (95% CI) | |

| Treatment failure: low/very low outcome-specific quality | |||||||||

| 1227,29,39, 40,53,67, 73,87,98, 118,123,173 | RCTs | Studies clinic- or hospital based (−0.5); no true control arm | Heterogeneity from meta- analysis (−0.5) | South/Southeast Asia, North/West/East Africa and Latin America. RHFs not tested in the home (−1) | Nine used cereal/ sugar–salt solution; one used sugar solution; two did not define RHF (−0.5) | 31/784 episodes | NA | 0* (−0.1, 0.1%) | *Pooled failure rate Random effects meta-analysis |

aSee Walker et al.15 for a description of the quality assessment and grading methods.

Figure 3.

Application of standardized rules for choice of final outcome to estimate effect of RHFs on the reduction of diarrhoea mortality (aSee Walker et al.15 for a description of the CHERG Rules for Evidence Review.)

ORT

We found 14 studies reporting diarrhoea mortality, one reporting all-cause mortality and five reporting dehydration or treatment failure for ORT that met our inclusion/exclusion criteria (Supplementary table 3). The studies abstracted are suggestive of an effect of joint promotion of ORS and/or RHF on diarrhoea mortality. Of the studies reporting mortality data with comparison groups (including historical comparison groups), all reported a decline in diarrhoea or all-cause mortality, although the magnitude of the declines, time periods over which they occurred and the associated coverage levels varied greatly. These studies primarily used pre/post designs and in most cases did not adjust for confounding; thus, it is not possible to determine whether the declines were causally associated with the use of ORS and RHFs, or with other interventions and changes occurring in the community during the same time period.

Discussion

We found a large body of evidence evaluating the efficacy and effectiveness of ORS, and a more limited number of studies assessing RHFs. Based on this evidence, we estimated that ORS may reduce diarrhoea mortality by up to 93%, but were unable to estimate the effectiveness of RHFs against diarrhoea mortality because no studies were conducted outside hospital setting, which is inconsistent with the definition of ‘home fluids’ (Figures 2 and 3). Whereas the overall quality of evidence supporting the effectiveness of ORS against diarrhoea mortality was low as a result of non-randomized study designs, our conclusions are strengthened by the consistency of the effect size and direction among the studies included and those excluded from the meta-analysis. Moreover, the biological basis for ORS, co-transport of glucose and sodium across the epithelial layer in the small intestine is well established and supports a protective effect of ORS against fluid losses and electrolyte imbalances.16,17

We correlated ORS effectiveness with coverage, using the absolute coverage levels reported for the intervention arms. However, in most community-based studies, ORS was also available and used at a low level in the comparison arms. The effective coverage level (difference in coverage between the intervention and comparison arms) was thus lower than the absolute coverage level used in our calculations. For this reason, our approach is conservative and likely overestimates the coverage needed to achieve a particular mortality reduction.

RHFs were not designed as an intervention to directly decrease diarrhoea mortality, but were instead intended to be used for home-based fluid management to prevent dehydration, with possible indirect effects on mortality. However, the only well-controlled studies of RHFs were conducted in hospital settings and included only sugar–salt solution and cereal–salt solution. Whereas we included these studies in our meta-analysis of RHF treatment failure, the results cannot be generalized to the administration of RHFs by a caregiver in the home and cannot be assumed to be representative of all current RHFs. Community-based studies of RHFs, which are not only inherently less controlled but also more relevant than hospital-based studies, have been conducted and were abstracted into Supplementary table 2, but either did not include a relevant comparison arm or failed to adequately document the coverage achieved, making it difficult to interpret their results. Moreover, we were unable to find studies meeting our inclusion criteria that assessed other RHFs such as water and rice water. Thus, our findings may not be representative of the full range of RHFs.

ORS is a simple, proven intervention that can be used at the community and facility level to prevent and treat diarrhoeal dehydration and decrease diarrhoea mortality. Whereas ORS is highly effective, coverage levels remain low in most countries. It is essential that ORS coverage be increased to achieve reductions in diarrhoea mortality; to do so, operations and implementation research is needed to better understand how to deliver ORS effectively and promote its use at home and facility level as part of appropriate case management of diarrhoea.

In contrast to ORS, RHFs were designed and recommended as a home-based intervention to prevent diarrhoeal dehydration, but this message has become confused as diarrhoea control programmes have evolved. Moreover, for RHFs to be used appropriately at home, caregivers must be able to assess whether a child is dehydrated and correctly determine whether to provide RHFs or ORS. Thus, whereas there is evidence suggesting that RHFs may be effective in preventing dehydration, its correct implementation and the associated behaviour change communication messages are complex. From a programmatic perspective, promoting the use of ORS for all diarrhoea episodes might, therefore, be both simpler and more effective than promoting ORS and RHFs as a package and teaching caregivers when and how to use each.

Supplementary data

Supplementary data are available at IJE online.

Funding

US Fund for UNICEF from the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation (grant 43386 to ‘Promote evidence-based decision making in designing maternal, neonatal and child health interventions in low- and middle-income countries’). MKM is supported by a training grant from the U.S. National Institutes of Health (grant T32HD046405 for ‘International Maternal and Child Health’).

Acknowledgement

We thank our colleagues at WHO and UNICEF for their review of the manuscript and valuable feedback.

Conflict of interest: none declared.

References

- 1.Bryce J, Boschi-Pinto C, Shibuya K, et al. WHO estimates of the causes of death in children. Lancet. 2005;365:1147–52. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(05)71877-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Cash RA, Nalin DR, Rochat R, et al. A clinical trial of oral therapy in a rural cholera-treatment center. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 1970;19:653–56. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.1970.19.653. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Mahalanabis D, Choudhuri AB, Bagchi NG, et al. Oral fluid therapy of cholera among Bangladesh refugees. Johns Hopkins Med J. 1973;132:197–205. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Mahalanabis D, Wallace CK, Kallen RJ, et al. Water and electrolyte losses due to cholera in infants and small children: a recovery balance study. Pediatrics. 1970;45:374–85. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Nalin DR, Cash RA. Oral or nasogastric maintenance therapy in pediatric cholera patients. J Pediatr. 1971;78:355–58. doi: 10.1016/s0022-3476(71)80028-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Nalin DR, Cash RA, Islam R, et al. Oral maintenance therapy for cholera in adults. Lancet. 1968;2:370–73. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(68)90591-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Pierce NF, Banwell JG, Rupak DM, et al. Effect of intragastric glucose-electrolyte infusion upon water and electrolyte balance in Asiatic cholera. Gastroenterology. 1968;55:333–43. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Pierce NF, Sack RB, Mitra RC, et al. Replacement of water and electrolyte losses in cholera by an oral glucose-electrolyte solution. Ann Intern Med. 1969;70:1173–81. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-70-6-1173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.World Health Organization. . Implementing the New Recommendations on the Clinical Management of Diarrhoea: Guidelines for Policy Makers and Programme Managers. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hahn S, Kim S, Garner P. Reduced osmolarity oral rehydration solution for treating dehydration caused by acute diarrhoea in children. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2002;(1) doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD002847. CD002847. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.World Health Organization. . Oral Rehydration Therapy for Treatment of Diarrhoea in the Home (Report No.: WHO/CDD/SER/86.9) Geneva: WHO1986; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Victora CG, Bryce J, Fontaine O, et al. Reducing deaths from diarrhoea through oral rehydration therapy. Bull World Health Organ. 2000;78:1246–55. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hartling L, Bellemare S, Wiebe N, et al. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. Oral versus intravenous rehydration for treating dehydration due to gastroenteritis in children. 2006;(3):CD004390. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Fontaine O, Gore SM, Pierce NF. Rice-based oral rehydration solution for treating diarrhoea. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2000;(2):CD001264. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD001264. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Walker N, Fischer Walker CL, Bahl R, et al. The CHERG methods and procedures for estimating effectiveness of interventions on cause-specific mortality. Int J Epidemiol. 2010;39(Suppl 1):i21–31. doi: 10.1093/ije/dyq036. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Schedl HP, Clifton JA. Solute and water absorption by the human small intestine. Nature. 1963;199:1264–67. doi: 10.1038/1991264a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Schultz SG, Zalusky R. Ion transport in isolated rabbit ileum. Ii. The interaction between active sodium and active sugar transport. J Gen Physiol. 1964;47:1043–59. doi: 10.1085/jgp.47.6.1043. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kumar V, Kumar R, Datta N. Oral rehydration therapy in reducing diarrhoea-related mortality in rural India. J Diarrhoeal Dis Res. 1987;5:159–64. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Rahaman MM, Aziz KM, Patwari Y, et al. Diarrhoeal mortality in two Bangladeshi villages with and without community-based oral rehydration therapy. Lancet. 1979;2:809–12. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(79)92172-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Thane T, Khin-Maung U, Tin A, et al. Oral rehydration therapy in the home by village mothers in Burma. Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg. 1984;78:581–89. doi: 10.1016/0035-9203(84)90211-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Beneficial effects of oral electrolyte–sugar solutions in the treatment of children's diarrhoea. 1. Studies in two ambulatory care clinics. J Trop Pediatr. 1981;27:62–67. doi: 10.1093/tropej/27.2.62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.International Study Group on Reduced-osmolarity ORS solutions. Multicentre evaluation of reduced-osmolarity oral rehydration salts solution. Lancet. 1995;345:282–85. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Multicenter, randomized, double-blind clinical trial to evaluate the efficacy and safety of a reduced osmolarity oral rehydration salts solution in children with acute watery diarrhea. Pediatrics. 2001;107:613–18. doi: 10.1542/peds.107.4.613. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Akbar MS, Baker KM, Aziz MA, et al. A randomised, double-blind clinical trial of a maltodextrin containing oral rehydration solution in acute infantile diarrhoea. J Diarrhoeal Dis Res. 1991;9:33–37. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Aksit S, Caglayan S, Cukan R, et al. Carob bean juice: a powerful adjunct to oral rehydration solution treatment in diarrhoea. Paediatr Perinat Epidemiol. 1998;12:176–81. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-3016.1998.00093.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Antony TJ, Mohan M. A comparative study of glycine fortified oral rehydration solution with standard WHO oral rehydration solution. Indian Pediatr. 1989;26:1196–201. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Arias MM, Alcaraz GM, Bernal C, et al. Oral rehydration with a plantain flour-based solution in children dehydrated by acute diarrhea: a clinical trial. Acta Paediatr. 1997;86:1047–51. doi: 10.1111/j.1651-2227.1997.tb14804.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Barclay DV, Gil-Ramos J, Mora JO, et al. A packaged rice-based oral rehydration solution for acute diarrhea. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 1995;20:408–16. doi: 10.1097/00005176-199505000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ben Mansour A, Achour A, Chabchoub S, et al. Comparative effects of the WHO solution and of a simplified solution in infants with acute diarrhea. Ann Pediatr. 1985;32(Pt 2):315–20. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Bernal C, Alcaraz GM, Botero JE. [Oral rehydration with a plantain flour-based solution precooked with standardized electrolytes. Biomedica. 2005;25:11–21. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Bernal C, Velasquez C, Garcia G, et al. Oral hydratation with a low osmolality solution in dehydrated children with diarrheic diseases: controlled clinical trial. Biomedica. 2003;23:47–59. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Bhan MK, Ghai OP, Khoshoo V, et al. Efficacy of mung bean (lentil) and pop rice based rehydration solutions in comparison with the standard glucose electrolyte solution. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 1987;6:392–99. doi: 10.1097/00005176-198705000-00016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Bhan MK, Sazawal S, Bhatnagar S, et al. Glycine, glycyl-glycine and maltodextrin based oral rehydration solution. Assessment of efficacy and safety in comparison to standard ORS. Acta Paediatr Scand. 1990;79:518–26. doi: 10.1111/j.1651-2227.1990.tb11506.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Bhargava SK, Sachdev HP, Das Gupta B, et al. Oral rehydration of neonates and young infants with dehydrating diarrhea: comparison of low and standard sodium content in oral rehydration solutions. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 1984;3:500–5. doi: 10.1097/00005176-198409000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Bhargava SK, Sachdev HP, Das Gupta B, et al. Oral therapy of neonates and young infants with World Health Organization rehydration packets: a controlled trial of two sets of instructions. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 1986;5:416–22. doi: 10.1097/00005176-198605000-00014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Bhatnagar S, Bahl R, Sharma PK, et al. Zinc with oral rehydration therapy reduces stool output and duration of diarrhea in hospitalized children: a randomized controlled trial. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2004;38:34–40. doi: 10.1097/00005176-200401000-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Brown KH, Gastanaduy AS, Saavedra JM, et al. Effect of continued oral feeding on clinical and nutritional outcomes of acute diarrhea in children. J Pediatr. 1988;112:191–200. doi: 10.1016/s0022-3476(88)80055-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Chatterjee A, Mahalanabis D, Jalan KN, et al. Oral rehydration in infantile diarrhoea. Controlled trial of a low sodium glucose electrolyte solution. Arch Dis Child. 1978;53:284–89. doi: 10.1136/adc.53.4.284. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Clements ML, Levine MM, Cleaves F, et al. Comparison of simple sugar/salt versus glucose/electrolyte oral rehydration solutions in infant diarrhoea. J Trop Med Hyg. 1981;84:189–94. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Cordero P, Araya M, Espinoza J, et al. Effect of oral rehydration and early re-feeding in the course of acute diarrhea in infants. Rev Chil Pediatr. 1985;56:412–18. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.David CB, Pyles LL, Pizzuti AM. Oral rehydration therapy: comparison of a commercial product with the standard solution. J Diarrhoeal Dis Res. 1986;4:222–26. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Duffau G, Emilfork M, Calderon A. Evaluations of 2 formulas for oral hydration in acute diarrheic syndrome with dehydration in infants. Bol Med Hosp Infant Mex. 1982;39:729–36. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Duffau-Toro G, Hormazabal-Valenzuela J. Oral hydration in infants hospitalized for acute diarrheic syndrome, using formulations of different energy densities. Bol Med Hosp Infant Mex. 1985;42:9–15. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Dutta P, Dutta D, Bhattacharya SK, et al. Comparative efficacy of three different oral rehydration solutions for the treatment of dehydrating diarrhoea in children. Indian J Med Res. 1988;87:229–33. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.el-Mougi M, Hegazi E, Amer A, et al. Efficacy of rice powder based oral rehydration solution on the outcome of acute diarrhoea in infants 1–4 months. J Trop Pediatr. 1989;35:204–5. doi: 10.1093/tropej/35.4.204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.el-Mougi M, Hegazi E, Galal O, et al. Controlled clinical trial on the efficacy of rice powder-based oral rehydration solution on the outcome of acute diarrhea in infants. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 1988;7:572–76. doi: 10.1097/00005176-198807000-00016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.el-Mougi M, Hendawi A, Koura H, et al. Efficacy of standard glucose-based and reduced-osmolarity maltodextrin-based oral rehydration solutions: effect of sugar malabsorption. Bull World Health Organ. 1996;74:471–77. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Faruque AS, Mahalanabis D, Hamadani J, et al. Hypo-osmolar sucrose oral rehydration solutions in acute diarrhoea: a pilot study. Acta Paediatr. 1996;85:1247–48. doi: 10.1111/j.1651-2227.1996.tb18240.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Faure A, de Leon M, Velasquez-Jones L, et al. Oral rehydration solutions with 60 or 90 mmol/L of sodium for infants with acute diarrhea in accord with their nutritional status. Bol Med Hosp Infant Mex. 1990;47:760–66. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Fayad IM, Hashem M, Duggan C, et al. Comparative efficacy of rice-based and glucose-based oral rehydration salts plus early reintroduction of food. Lancet. 1993;342:772–75. doi: 10.1016/0140-6736(93)91540-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Gonzalez-Adriano SR, Valdes-Garza HE, Garcia-Valdes LC. Oral hydration versus intravenous hydration in patients with acute diarrhea. Bol Med Hosp Infant Mex. 1988;45:165–72. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Grange A. Evaluation of malto-dextrin/glycine oral rehydration solution. Ann Trop Paediatr. 1992;12:353–58. doi: 10.1080/02724936.1992.11747599. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Grange AO. Evaluation of cassava-salt suspension in the management of acute diarrhoea in infants and children. J Diarrhoeal Dis Res. 1994;12:55–58. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Guiraldes E, Trivino X, Figueroa G, et al. Comparison of an oral rice-based electrolyte solution and a glucose-based electrolyte solution in hospitalized infants with diarrheal dehydration. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 1995;20:417–24. doi: 10.1097/00005176-199505000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Guiraldes E, Trivino X, Hodgson MI, et al. Treatment of acute infantile diarrhoea with a commercial rice-based oral rehydration solution. J Diarrhoeal Dis Res. 1995;13:207–11. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Gutierrez C, Villa S, Mota FR, et al. Does an L-glutamine-containing, glucose-free, oral rehydration solution reduce stool output and time to rehydrate in children with acute diarrhoea? A double-blind randomized clinical trial. J Health Popul Nutr. 2007;25:278–84. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Hernandez A, Jaramillo C, Ramirez R, et al. Treatment of acute diarrhea in children. Comparative study of 3 oral rehydration solutions and venoclysis in Colombia. Bol Oficina Sanit Panam. 1987;102:606–16. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Hidayat S, Srie Enggar KD, Pardede N, et al. Nasogastric drip rehydration therapy in acute diarrhea with severe dehydration. Paediatr Indones. 1988;28:79–84. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Ibrahim S, Isani Z. Sagodana based verses rice based oral rehydration solution in the management of acute diarrhoea in Pakistani children. J Pak Med Assoc. 1997;47:16–19. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Islam A, Molla AM, Ahmed MA et al. Is rice based oral rehydration therapy effective in young infants? Arch Dis Child. 1994;71:19–23. doi: 10.1136/adc.71.1.19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Islam MR. Can potassium citrate replace sodium bicarbonate and potassium chloride of oral rehydration solution? Arch Dis Child. 1985;60:852–55. doi: 10.1136/adc.60.9.852. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Islam MR. Citrate can effectively replace bicarbonate in oral rehydration salts for cholera and infantile diarrhoea. Bull World Health Organ. 1986;64:145–50. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Islam MR, Ahmed SM. Oral rehydration solution without bicarbonate. Arch Dis Child. 1984;59:1072–75. doi: 10.1136/adc.59.11.1072. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Iyngkaran N, Yadav M. Rice starch low sodium oral rehydration solution (ORS) in infantile diarrhoea. Med J Malaysia. 1995;50:141–44. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Jirapinyo P, Moran JR. Comparison of oral rehydration solutions made with rice syrup solids or glucose in the treatment of acute diarrhea in infants. J Med Assoc Thai. 1996;79:154–60. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Kenya PR, Odongo HW, Oundo G, et al. Cereal based oral rehydration solutions. Arch Dis Child. 1989;64:1032–35. doi: 10.1136/adc.64.7.1032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Kenya PR, Ondongo HW, Molla AM, et al. Maize-salt solution in the treatment of diarrhoea. Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg. 1990;84:595–98. doi: 10.1016/0035-9203(90)90054-i. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Khan AM, Sarker SA, Alam NH, et al. Low osmolar oral rehydration salts solution in the treatment of acute watery diarrhoea in neonates and young infants: a randomized, controlled clinical trial. J Health Popul Nutr. 2005;23:52–57. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Kinoti SN, Wasunna A, Turkish J, et al. A comparison of the efficacy of maize-based ORS and standard WHO ORS in the treatment of acute childhood diarrhoea at Kenyatta National Hospital, Nairobi, Kenya: results of a pilot study. East Afr Med J. 1986;63:168–74. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Lebenthal E, Khin Maung U, Rolston DD, et al. Thermophilic amylase-digested rice-electrolyte solution in the treatment of acute diarrhea in children. Pediatrics. 1995;95:198–202. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Lin SL, Kong MS. Extremely low sodium hypotonic rehydration solution for young children with acute gastroenteritis. Chang Gung Med J. 2001;24:294–99. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Lopez-Leon VM, San Roman-Rivera E, Velasquez-Jones L. Use of a solution for oral hydration with or without intermediate water in children dehydrated by diarrhea. Bol Med Hosp Infant Mex. 1988;45:84–88. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Martinez, Salgado H. Oral rehydration solutions based on cereals. Arch Latinoam Nutr. 1992;42(Suppl 3):56S–67S. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Martinez-Pantaleon O, Faure-Vilchis A, Gomez-Najera RI, et al. Comparative study of oral rehydration solutions containing 90 or 60 millimoles of sodium per liter. Bol Med Hosp Infant Mex. 1988;45:817–22. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Maulen-Radovan I, Fernandez-Varela H, Acosta-Bastidas M, et al. Safety and efficacy of a rice-based oral rehydration salt solution in the treatment of diarrhea in infants less than 6 months of age. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 1994;19:78–82. doi: 10.1097/00005176-199407000-00012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Maulen-Radovan I, Gutierrez-Castrellon P, Hashem M, et al. Safety and efficacy of a premixed, rice-based oral rehydration solution. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2004;38:159–63. doi: 10.1097/00005176-200402000-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Moenginah PA, Suprapto, Soenarto J, et al. Sucrose electrolyte solution for oral rehydration in diarrhea. J Trop Pediatr Environ Child Health. 1978;24:127–30. doi: 10.1093/tropej/24.3.127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Mohan M, Antony TJ, Malik S, et al. Rice powder oral rehydration solution as an alternative to glucose electrolyte solution. Indian J Med Res. 1988;87:234–39. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Mohan M, Sethi JS, Daral TS, et al. Controlled trial of rice powder and glucose rehydration solutions as oral therapy for acute dehydrating diarrhea in infants. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 1986;5:423–27. doi: 10.1097/00005176-198605000-00015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Molina S, Vettorazzi C, Peerson JM, et al. Clinical trial of glucose-oral rehydration solution (ORS), rice dextrin-ORS, and rice flour-ORS for the management of children with acute diarrhea and mild or moderate dehydration. Pediatrics. 1995;95:191–97. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Mota-Hernández F, Gutierrez-Camacho C, Martinez-Aguilar G. Utilidad de una nueva solucion de hidratacion oral de baja osmolaridad en ninos con diarrhea aguda. Bol Med Hosp Infant Mex. 1995;52:553–59. [Google Scholar]

- 82.Mota-Hernández F, Gutierrez-Camacho C, Cabrales-Martinez RG. Ensayo clinico controlado para evaluar eficacia y seguridad de dos soluciones de hidratacion oral con composicion OMS y diferente pH. Bol Med Hosp Infant Mex. 1999;56:429–34. [Google Scholar]

- 83.Mota-Hernandez F, Gutierrez-Camacho C, Cabrales-Martinez RG, Villa-Contreras S. Hidratacion oral continua o a dosis fraccionadas en ninos deshidratados por diarrea aguda. Salud Publica Mex. 2002;44:21–25. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Mota-Hernandez F, Rodriguez-Suarez RS, Perez-Ricardez ML, et al. Treatment of diarrheic disease at home. Comparison of 2 forms of oral solutions: liquid and concentrated in small bags. Bol Med Hosp Infant Mex. 1990;47:324–31. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Nalin DR, Harland E, Ramlal A, et al. Comparison of low and high sodium and potassium content in oral rehydration solutions. J Pediatr. 1980;97:848–53. doi: 10.1016/s0022-3476(80)80287-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Nalin DR, Levine MM, Mata L, et al. Comparison of sucrose with glucose in oral therapy of infant diarrhoea. Lancet. 1978;2:277–79. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(78)91686-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Olusanya O, Olanrewaju DM, Oluwole FA. Studies on the effectiveness, safety and acceptability of fluids from local foodstuffs in the prevention and management of dehydration caused by diarrhoea in children. J Trop Pediatr. 1994;40:360–64. doi: 10.1093/tropej/40.6.360. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Patra FC, Mahalanabis D, Jalan KN, et al. A controlled clinical trial of rice and glycine-containing oral rehydration solution in acute diarrhoea in children. J Diarrhoeal Dis Res. 1986;4:16–19. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Patra FC, Mahalanabis D, Jalan KN, et al. Is oral rice electrolyte solution superior to glucose electrolyte solution in infantile diarrhoea? Arch Dis Child. 1982;57:910–12. doi: 10.1136/adc.57.12.910. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Patra FC, Mahalanabis D, Jalan KN, et al. Can acetate replace bicarbonate in oral rehydration solution for infantile diarrhoea? Arch Dis Child. 1982;57:625–27. doi: 10.1136/adc.57.8.625. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Patra FC, Mahalanabis D, Jalan KN, et al. In search of a super solution: controlled trial of glycine-glucose oral rehydration solution in infantile diarrhoea. Acta Paediatr Scand. 1984;73:18–21. doi: 10.1111/j.1651-2227.1984.tb09891.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Pelleboer RA, Felius A, Goje BS, et al. Sorghum-based oral rehydration solution in the treatment of acute diarrhoea. Trop Geogr Med. 1990;42:63–68. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Pizarro D, Castillo B, Posada G, et al. Efficacy comparison of oral rehydration solutions containing either 90 or 75 millimoles of sodium per liter. Pediatrics. 1987;79:190–95. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Pizarro D, Posada G, Mahalanabis D, et al. Comparison of efficacy of a glucose/glycine/glycylglycine electrolyte solution versus the standard WHO/ORS in diarrheic dehydrated children. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 1988;7:882–88. doi: 10.1097/00005176-198811000-00016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Pizarro DT, Posada GS, Levine MM, et al. Comparison of efficacy of oral rehydration fluids administered at 37 degrees C or 23 degrees C. J Trop Pediatr. 1987;33:48–51. doi: 10.1093/tropej/33.1.48. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Raghupathy P, Ramakrishna BS, Oommen SP, et al. Amylase-resistant starch as adjunct to oral rehydration therapy in children with diarrhea. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2006;42:362–68. doi: 10.1097/01.mpg.0000214163.83316.41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Ribeiro Junior H, Ribeiro T, Mattos A, et al. Treatment of acute diarrhea with oral rehydration solutions containing glutamine. J Am Coll Nutr. 1994;13:251–55. doi: 10.1080/07315724.1994.10718405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Sabchareon A, Chongsuphajaisiddhi T, Kittikoon P, et al. Rice-powder salt solution in the treatment of acute diarrhea in young children. Southeast Asian J Trop Med Public Health. 1992;23:427–32. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Saberi MS, Assaee M. Oral hydration of diarrhoeal dehydration. Comparison of high and low sodium concentration in rehydration solutions. Acta Paediatr Scand. 1983;72:167–70. doi: 10.1111/j.1651-2227.1983.tb09690.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Sachdev HP, Bhargava SK, Das Gupta B, et al. Oral rehydration of neonates and young infants with dehydrating diarrhea. Indian Pediatr. 1984;21:195–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Sack DA, Chowdhury AM, Eusof A, et al. Oral hydration rotavirus diarrhoea: a double blind comparison of sucrose with glucose electrolyte solution. Lancet. 1978;2:280–83. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(78)91687-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Sack DA, Islam S, Brown KH, et al. Oral therapy in children with cholera: a comparison of sucrose and glucose electrolyte solutions. J Pediatr. 1980;96:20–25. doi: 10.1016/s0022-3476(80)80317-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Sack RB, Castrellon J, Della Sera E, et al. Hydrolyzed lactalbumin-based oral rehydration solution for acute diarrhoea in infants. Acta Paediatr. 1994;83:819–24. doi: 10.1111/j.1651-2227.1994.tb13152.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Salazar-Lindo E, Sack RB, Chea-Woo E, et al. Bicarbonate versus citrate in oral rehydration therapy in infants with watery diarrhea: a controlled clinical trial. J Pediatr. 1986;108:55–60. doi: 10.1016/s0022-3476(86)80768-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Santosham M, Burns BA, Reid R, et al. Glycine-based oral rehydration solution: reassessment of safety and efficacy. J Pediatr. 1986;109:795–801. doi: 10.1016/s0022-3476(86)80696-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Santosham M, Daum RS, Dillman L, et al. Oral rehydration therapy of infantile diarrhea: a controlled study of well-nourished children hospitalized in the United States and Panama. N Engl J Med. 1982;306:1070–76. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198205063061802. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Santosham M, Fayad I, Abu Zikri M, et al. A double-blind clinical trial comparing World Health Organization oral rehydration solution with a reduced osmolarity solution containing equal amounts of sodium and glucose. J Pediatr. 1996;128:45–51. doi: 10.1016/s0022-3476(96)70426-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Santosham M, Fayad IM, Hashem M, et al. A comparison of rice-based oral rehydration solution and “early feeding” for the treatment of acute diarrhea in infants. J Pediatr. 1990;116:868–75. doi: 10.1016/s0022-3476(05)80642-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Santosham M, Foster S, Reid R, et al. Role of soy-based, lactose-free formula during treatment of acute diarrhea. Pediatrics. 1985;76:292–98. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Santosham M, Goepp J, Burns B, et al. Role of a soy-based lactose-free formula in the outpatient management of diarrhea. Pediatrics. 1991;87:619–22. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Sarker SA, Mahalanabis D, Alam NH, et al. Reduced osmolarity oral rehydration solution for persistent diarrhea in infants: a randomized controlled clinical trial. J Pediatr. 2001;138:532–38. doi: 10.1067/mpd.2001.112161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Sarker SA, Majid N, Mahalanabis D. Alanine- and glucose-based hypo-osmolar oral rehydration solution in infants with persistent diarrhoea: a controlled trial. Acta Paediatr. 1995;84:775–80. doi: 10.1111/j.1651-2227.1995.tb13755.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Sazawal S, Bhatnagar S, Bhan MK, et al. Alanine-based oral rehydration solution: assessment of efficacy in acute noncholera diarrhea among children. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 1991;12:461–68. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114.Shaikh S, Molla AM, Islam A, et al. A traditional diet as part of oral rehydration therapy in severe acute diarrhoea in young children. J Diarrhoeal Dis Res. 1991;9:258–63. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115.Sharifi J, Ghavami F, Nowrouzi Z, et al. Oral versus intravenous rehydration therapy in severe gastroenteritis. Arch Dis Child. 1985;60:856–60. doi: 10.1136/adc.60.9.856. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116.Sharma A, Pradhan RK. Comparative study of rice-based oral rehydration salt solution versus glucose-based oral rehydration salt solution (WHO) in children with acute dehydrating diarrhoea. J Indian Med Assoc. 1998;96:367–68. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 117.Simakachorn N, Pichaipat V, Rithipornpaisarn P, et al. Clinical evaluation of the addition of lyophilized, heat-killed Lactobacillus acidophilus LB to oral rehydration therapy in the treatment of acute diarrhea in children. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2000;30:68–72. doi: 10.1097/00005176-200001000-00020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 118.Sirivichayakul C, Chokejindachai W, Vithayasai N, et al. Effects of rice powder salt solution and milk-rice mixture on acute watery diarrhea in young children. Southeast Asian J Trop Med Public Health. 2000;31:354–59. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 119.Solar G, Infante JI, Ugarte F. Rehydration in acute diarrhea with sodium 60 oral solution. Rev Child Pediatr. 1988;59:93–95. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 120.Sunoto, Suharyono, Budiarso AD, et al. Oral rehydration therapy in young infants less than 3 months with acute diarrhoea and moderate dehydration. Paediatr Indones. 1988;28:67–78. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 121.Velasquez-Jones L, Becerra FC, Faure A, et al. Clinical experience in Mexico with a new oral rehydration solution with lower osmolality. Clin Ther. 1990;12(Suppl A):95–103. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 122.Velasquez-Jones L, Mota-Hernandez F, Puente M, et al. Effect of an oral rehydration solution with glycine and glycylglycine in infants with acute diarrhoea. J Trop Pediatr. 1989;35:47. doi: 10.1093/tropej/35.1.47. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 123.Yartey J, Nkrumah F, Hori H, et al. Clinical trial of fermented maize-based oral rehydration solution in the management of acute diarrhoea in children. Ann Trop Paediatr. 1995;15:61–68. doi: 10.1080/02724936.1995.11747750. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 124.Yurdakok K, Yalcin S. Comparative efficacy of rice-ORS and glucose-ORS in moderately dehydrated Turkish children with diarrhea. Turk J Pediatr. 1995;37:315–21. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 125.Abdalla S, Helmy N, el Essaily M, et al. Oral rehydration for the low-birthweight baby with diarrhoea. Lancet. 1984;2:818–19. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(84)90749-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 126.Abidin Z, Iyngkaran N, Royan G. Oral rehydration in infantile diarrhoea the optimum carbohydrate–electrolyte composition. J Singapore Paediatr Soc. 1980;22:100–3. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 127.Black RE, Merson MH, Taylor PR, et al. Glucose vs sucrose in oral rehydration solutions for infants and young children with rotavirus-associated diarrhea. Pediatrics. 1981;67:79–83. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 128.Caichac A, Aviles CL, Romero J, et al. [Oral rehydration in infants with acute diarrhea] Rev Child Pediatr. 1985;56:162–64. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 129.Cancio Alvarez M, Interian Dickinson M, Gomez Vasallo A, et al. Uso de la rehidratacion oral en el servicio de gastroenteritis del Hospital Pediatrico de Matanzas. Rev Cub Enf. 1986;2:62–67. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 130.Chatterjee A, Mahalanabis D, Jalan KN, et al. Evaluation of a sucrose/electrolyte solution for oral rehydration in acute infantile diarrhoea. Lancet. 1977;1:1333–35. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(77)92550-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 131.Datta P, Datta D, Bhattacharya SK, et al. Effectiveness of oral glucose electrolyte solution in the treatment of acute diarrhoeas in neonates & young infants. Indian J Med Res. 1984;80:435–38. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 132.Delucchi MA, Guiraldes E, Hirsch T, et al. The use of oral hydration in the treatment of children with acute diarrhea in primary care. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 1989;9:328–34. doi: 10.1097/00005176-198910000-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 133.Dutta P, Bhattacharya SK, Dutta D, et al. Oral rehydration solution containing 90 millimol sodium is safe and useful in treating diarrhoea in severely malnourished children. J Diarrhoeal Dis Res. 1991;9:118–22. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 134.Ferrero FC, Mazzucchelli MT, Voyer LE. Analisis de la terapeutica de rehidratacion oral, Campana estival 1984–85. Arch Arg Pediatr. 1985;83:262–68. [Google Scholar]

- 135.Godoy-Olvera LM, Dohi-Fujii B, de Leon-Sanchez J. Oral hydration in children with prolonged diarrhea. Study of 107 cases. Bol Med Hosp Infant Mex. 1988;45:424–31. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 136.Guzman C, Pizarro D, Castillo B, et al. Hypernatremic diarrheal dehydration treated with oral glucose-electrolyte solution containing 90 or 75 mEq/L of sodium. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 1988;7:694–98. doi: 10.1097/00005176-198809000-00013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 137.Helmy N, Abdalla S, el Essaily M, et al. Oral rehydration therapy for low birth weight neonates suffering from diarrhea in the intensive care unit. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 1988;7:417–23. doi: 10.1097/00005176-198805000-00018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 138.Hirschhorn N, Cash RA, Woodward WE, et al. Oral fluid therapy of Apache children with acute infectious diarrhoea. Lancet. 1972;2:15–18. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(72)91277-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 139.Hirschhorn N, McCarthy BJ, Ranney B, et al. Ad libitum oral glucose-electrolyte therapy for acute diarrhea in Apache children. J Pediatr. 1973;83:562–71. doi: 10.1016/s0022-3476(73)80215-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 140.Kinoti SN, Maggwa AB, Turkish J, et al. Management of acute childhood diarrhoea with oral rehydration therapy at Kenyatta National Hospital, Nairobi, Kenya. East Afr Med J. 1985;62:5–11. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 141.Lopez-Leon VM, Heredia-Moreno OC, Faure-Vilchis AE, et al. 1,144 children with acute diarrhea undergoing oral rehydration therapy with a solution containing 90 mmol/L of sodium. Bol Med Hosp Infant Mex. 1988;45:24–28. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 142.Marin L, Saner G, Sokucu S, et al. Oral rehydration therapy in neonates and young infants with infectious diarrhoea. Acta Paediatr Scand. 1987;76:431–37. doi: 10.1111/j.1651-2227.1987.tb10494.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 143.Marin L, Sokucu S, Gunoz H, et al. Salt and water homeostasis during oral rehydration therapy in neonates and young infants with acute diarrhoea. II. Rehydration with a solution containing 90 mmol sodium per litre (ORS90) Acta Paediatr Scand. 1988;77:37–41. doi: 10.1111/j.1651-2227.1988.tb10594.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 144.Micetic-Turk D. Evaluation of five oral rehydration solutions for children with diarrhea. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 1995;20:358–60. doi: 10.1097/00005176-199504000-00021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 145.Montero Veitia BL, Dager Haber A, Justiz Hernandez S. Oral rehydration in patients with acute diarrheic diseases. Rev Cubana Enferm. 1988;4:131–38. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 146.Nagpal A, Aneja S. Oral rehydration therapy in severely malnourished children with diarrheal dehydration. Indian J Pediatr. 1992;59:313–19. doi: 10.1007/BF02821796. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 147.Nalin DR, Levine MM, Mata L, et al. Oral rehydration and maintenance of children with rotavirus and bacterial diarrhoeas. Bull World Health Organ. 1979;57:453–59. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 148.Ozmert E, Uckardes Y, Yurdakok K, et al. Is a 2:1 ratio of standard WHO ORS to plain water effective in the treatment of moderate dehydration. J Trop Pediatr. 2003;49:291–94. doi: 10.1093/tropej/49.5.291. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 149.Pizarro D, Posada G, Levine MM. Tratamiento oral de la deshidratacion hipernatremica. Acta Med Costa Rica. 1981;24:341–46. [Google Scholar]

- 150.Pizarro D, Posada G, Levine MM. Hypernatremic diarrheal dehydration treated with “slow” (12-hour) oral rehydration therapy: a preliminary report. J Pediatr. 1984;104:316–19. doi: 10.1016/s0022-3476(84)81023-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 151.Pizarro D, Posada G, Levine MM, et al. Oral rehydration of infants with acute diarrhoeal dehydration: a practical method. J Trop Med Hyg. 1980;83:241–45. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 152.Pizarro D, Posada G, Mata L. Treatment of 242 neonates with dehydrating diarrhea with an oral glucose-electrolyte solution. J Pediatr. 1983;102:153–56. doi: 10.1016/s0022-3476(83)80318-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 153.Pizarro D, Posada G, Mohs E, et al. Evaluation of oral therapy for infant diarrhoea in an emergency room setting: the acute episode as an opportunity for instructing mothers in home treatment. Bull World Health Organ. 1979;57:983–86. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 154.Pizarro D, Posada G, Nalin DR, et al. Rehydration by the oral route and its maintenance in patients from birth to 3 months old dehydrated due to diarrhea. Bol Med Hosp Infant Mex. 1980;37:879–91. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 155.Pizarro D, Posada G, Villavicencio N, et al. Oral rehydration in hypernatremic and hyponatremic diarrheal dehydration. Am J Dis Child. 1983;137:730–34. doi: 10.1001/archpedi.1983.02140340014003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 156.Raghu MB, Deshpande A, Chintu C. Oral rehydration for diarrhoeal diseases in children. Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg. 1981;75:552–55. doi: 10.1016/0035-9203(81)90197-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 157.Rai V, Mohan M, Bhargava SK, et al. W.H.O. recommended oral rehydration solution in acute diarrheal dehydration in infants. Indian Pediatr. 1985;22:493–99. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 158.Roy SK, Rabbani GH, Black RE. Oral rehydration solution safely used in breast-fed children without additional water. J Trop Med Hyg. 1984;87:11–13. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 159.Seriki O, Adekunle FA, Gacke K, et al. Oral rehydration of infants and children with diarrhoea. Trop Doct. 1983;13:120–23. doi: 10.1177/004947558301300310. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 160.Sharifi J, Ghavami F. Oral rehydration therapy of severe diarrheal dehydration. Clin Pediatr. 1984;23:87–90. doi: 10.1177/000992288402300204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 161.Sharifi J, Ghavami F, Nowruzi Z. Treatment of severe diarrhoeal dehydration in hospital and home by oral fluids. J Trop Med Hyg. 1987;90:19–24. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 162.Sharma A, Kumar R. Study on efficacy of WHO-ORS in malnourished children with acute dehydrating diarrhoea. J Indian Med Assoc. 2003;101:346, 348, 350. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 163.Sokucu S, Marin L, Gunoz H, et al. Oral rehydration therapy in infectious diarrhoea. Comparison of rehydration solutions with 60 and 90 mmol sodium per litre. Acta Paediatr Scand. 1985;74:489–94. doi: 10.1111/j.1651-2227.1985.tb11015.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 164.Sunakorn P. Oral electrolyte therapy for acute diarrhea in infants. J Med Assoc Thai. 1981;64:401–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 165.Taylor PR, Merson MH, Black RE, et al. Oral rehydration therapy for treatment of rotavirus diarrhoea in a rural treatment centre in Bangladesh. Arch Dis Child. 1980;55:376–79. doi: 10.1136/adc.55.5.376. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 166.Teka T. Analysis of the use of oral rehydration therapy corner in a teaching hospital in Gondar, Ethiopia. East Afr Med J. 1995;72:669–71. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 167.Ugarte JM, Chavez E, Curotto D, et al. Oral rehydration of infants with acute diarrhea in emergency services. Rev Child Pediatr. 1988;59:174–77. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 168.Umana MA, Fernandez J, Pizarro D. Rehydration by the oral route in newborn infants dehydrated by acute diarrheal disease. Bol Med Hosp Infant Mex. 1984;41:460–63. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 169.Uzel N, Ugur S, Neyzi O. Outcome of rehydration of diarrhea cases by oral route. Acta Paediatr Scand. 1991;80:545–56. doi: 10.1111/j.1651-2227.1991.tb11900.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 170.Varavithya W, Sunthornkachit R, Eampokalap B. Oral rehydration therapy for invasive diarrhea. Rev Infect Dis. 1991;13(Suppl 4):S325–31. doi: 10.1093/clinids/13.supplement_4.s325. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 171.Velasquez-Jones L, Llausas-Magana E, Mota-Hernandez F, et al. Ambulatory treatment of the child dehydrated by acute diarrhea. Bol Med Hosp Infant Mex. 1985;42:220–25. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 172.Velasquez-Jones L, Mota-Hernandez F, Kane-Quiros J, et al. Vomiting frequency in children with orally rehydrated diarrhea. Bol Med Hosp Infant Mex. 1986;43:353–58. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 173.Akosa UM, Ketiku AO, Omotade OO. The nutrient content and effectiveness of rice flour and maize flour based oral rehydration solutions. Afr J Med Med Sci. 2000;29:145–49. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]