Abstract

Objectives:

Findings have shown that many people do not seek help when experiencing psychological distress. The main aim of this paper was to examine the sociodemographic and health status factors that predict help seeking for self reported mental health problems for males and females from a general practitioner.

Design:

The analysis used data from the HRB National Psychological Wellbeing and Distress Survey – a telephone survey of the population aged 18 years and over.

Methods:

Telephone numbers were selected on a random probability basis. An initial set of random clusters was selected from the Geodirectory. Using these sampling areas, random digit dialling was used to generate a random telephone sample. Data were weighted on key variables. Respondents who reported mental health problems in the previous year were included in the current study (382 / 2674).

Results:

The findings showed gender differences in the models of predictors between males and females with more factors influencing attendance at the GP for males than for females. While only social limitations and access to free healthcare predicted female attendance, a range of sociodemographic and psychological factors influenced male attendance.

Conclusions:

Findings suggest that a ‘gender sensitive approach’ should be applied to mental health policies and mental health promotion and prevention programmes. Acknowledgement and awareness of the factors that influence help seeking will aid the design of gender specific promotion, prevention and treatment programmes at primary care level.

Introduction

Mental health and wellbeing have become important public health issues. It is commonly found that a greater proportion of females report common mental health problems than males (e.g. National Centre for Social Research, 2004; Northern Ireland Statistics and Research Agency, 2002). Furthermore the age pattern evident in males and females with common mental disorders are different (European Commission, 2004). These gender differences have led to the suggestion that “gender is a critical determinant of mental health” and that risks for mental health are gender specific (Courtenay, 2000; World Health Organization, 2001). Taking into account gender differences in mental health, including risk and help seeking, will ensure more “gender sensitive approach” in mental health policies (World Health Organisation, 2004).

While many individuals may be experiencing mental health problems, few consult formal healthcare services. In a European survey only one in four adults with a mental disorder consulted formal healthcare services (The ESEMeD / MHEDEA 2000 Investigators, 2004). The importance of the factors that influence help seeking has been highlighted at the EU level suggesting that the help-seeking behaviour should be measured (WHO, 2005). The majority of those who do receive treatment do so in primary care with only a small minority requiring more specialised mental health services (European Commission, 2006; Tedstone Doherty et al. 2007). It is estimated that 90% of common mental health problems are dealt with by the general practitioner while 10% are dealt with by specialised mental health services (Department of Health and Children, 1984). Furthermore it is estimated that one-third of patients with severe and enduring mental health problems are dealt with solely by the general practitioner (Tylee, 2005).

Factors such as gender, marital status and education have been found to influence help seeking behaviour (Kessler, Brown, & Broman, 1981; Rickwood & Braithwaite, 1994; Parslow & Jorm, 2000; Simon, 2002). One of the most common findings in the literature is that females are more likely to seek help than males. Rogler and Cortez (1993) suggest that gender differences in help-seeking are best explained by different cultural gender roles, with regard to who takes on socioemotional leadership in the family. In cultures where decision-making and performing tasks are role-segregated, women are more likely to take on socioemotional leadership in order to sustain psychological well-being in the family (Rogler & Hollingshead, 1985). This point of view is further supported by the application of the Theory of Planned Behaviour to the male help seeking behaviour due to the gender role conflict of traditional masculinity ideology which is associated with negative attitudes towards help-seeking for psychological problems (Smith, Tran, & Thompson, 2008). The latter study suggests that the relationship between traditional masculinity ideology and help-seeking intentions can be mediated by attitudes to help seeking for emotional problems. Regarding the influence of intimate partners, research suggests that the presence of intimate partners may positively influence help-seeking, especially for men (Tudiver & Talbot, 1999).

Some researchers suggest looking at pathways of seeking help as an interaction between the level of distress, and the psychosocial and cultural environment (Rogler & Cortes, 1993; Jorm et al. 1997). It is argued that a combination of cognitive and social aspects, such as availability of information and resources, willingness to conform to the cultural norms, and social support influence the actual act of help-seeking.

One of the most common reasons for not seeking help could be the stigma surrounding mental illness (Vogel & Wade, 2009). This stigma is associated with the rejection of those with mental illnesses who are perceived as different, unacceptable or dangerous. There is also public stigma associated with seeking help for less severe psychological problems (Jorm & Wright, 2008). More recently it has been argued that there is a much more potent stigma that may be more directly related to help seeking (Vogel & Wade, 2009). Self-stigma is thought to be an internal form of stigma whereby the individual perceives the act of seeking professional help for distress as a threat to their self-worth and as a weakness of character (Vogel et al., 2006). Lin & Pariah (1999) found that embarrassment, and being viewed as unbalanced, prevented people from seeking help for psychological problems. Self stigma is thought to be even more pronounced for those with less severe problems where counselling or therapy is viewed as a voluntary activity rather than mandatory (Vogel & Wade, 2009). Vogel and Wade also argue that self stigma is related to cultural and gender-role norms. Smith et al's. (2008) study argued that masculinity ideology and help seeking intentions can be mediated by attitudes to help seeking which may reflect the extent to which an individual experiences self stigma.

Of primary importance is the identification of specific groups who are least likely to seek help when experiencing psychological distress and the factors that impact on help seeking. Failure to seek appropriate help can lead to the escalation of problems that may require more intensive interventions at a later stage for the individual. Furthermore planning and development of health services aimed at providing support for psychological distress may remain underused and underdeveloped. This will have social, health and economic consequences for the individual and their families and have negative consequences for society including unemployment, lost productivity, reduction in community participation and an increase in the use of more intensive and costly health services (World Health Organization and World Organization of Family Doctors (Wonca), 2008).

The aim of the study was to investigate gender differences in self-reported mental health problems and help seeking behaviour from the general practitioner. As the majority of individuals are treated at the primary care level it is important to investigate the factors that influence help seeking at this level. The specific objectives of the study were to;

1) examine gender differences in self-reported mental health problems in the previous year

2) examine help seeking behaviour in the previous year specifically for mental health problems

3) examine health and socio-demographic factors that are associated with seeking help from a general practitioner for psychological distress for males and females.

Method

Fieldwork for the survey was carried out over two-week intervals in December 2005, January 2006 and April 2006. Of all those who were contacted successfully and were eligible to participate (n = 5,678), 2,905 people (51%) agreed to participate and 2,711 people (48%) completed the survey. The study received ethical approval from the HRB Research Ethics Committee (REC).

The study was carried out in Ireland. The Republic operates primarily within a fee for service system paid by the patient at the point of contact. Approximately 30% of the population are entitled to free public healthcare services including GP visits (Nolan, 2008). Eligibility for free medical services is determined by an income test.

Respondents were asked if they had experienced a mental, nervous or emotional problem in the previous year. Only those who reported mental health problems in the previous year were selected for further analysis (382 / 2674).

Procedure

The target population was all persons aged 18 years and over living in private households. Telephone numbers were drawn on a random, probability basis. The completed sample was re-weighted using a minimum information loss algorithm. The weighting scheme was designed to adjust the sample distributions for a number of key variables (for more information on the survey procedure see Tedstone Doherty et al. 2007).

Socio-demographic measures

Visual binning and theoretical considerations were used to recode variables into smaller number of categories for a more parsimonious solution. Socio-demographic variables included three age categories (18-49, 40-64, 65+), gender, two marital status categories (married/cohabiting (with partner) separated/divorced/widowed/never married (without partner)), three educational levels (primary/uncertified secondary; leaving cert; third), two employment categories (unemployed/disabled versus employed/occupied/ retired), two weekly net household income categories (up to €749 per week; €750 and over per week), having access to free medical care (Yes/No), urban/rural areas recoded as population up to 1500 (rural) and 1500 and over (urban).

Limitations due to mental health problems

Respondents were asked if they had experienced limitations in social activities due to mental health problems in the previous and also if they had experienced limitations in physical activities due to mental health problems in the previous year. For both questions responses were coded into ‘no limitations’ or ‘some limitations’.

Self-perceived physical health and quality of life in the last year

Respondents were also asked to rate their physical health during the previous year on a five-point scale from ‘very poor’ to ‘very good’. Included also were the respondents' ratings of their quality of life in the last 12 months on a five-point scale from ‘very poor’ to ‘very good.’ The two variables were recoded for the analysis to a binary variable of ‘good’ or ‘less than good’.

Distress Disclosure Index

In order to measure an individual's level of distress disclosure a 12-item Likert scale, the Distress Disclosure Index (DDI; Kahn and Hessling, 2001) was used. This scale is a self-reporting measure of one's tendency to conceal versus disclose distressing personal information, which has been shown to be related to an individual's psychological well-being and a predictor of an individual's help-seeking behaviour (see Kahn and Hessling, 2001). Respondents were asked to rate 12 DDI statements (six positive and six negative) on a five-point scale from ‘strongly disagree’ to ‘strongly agree’. Scores of the six negative statements were reversed and the total DDI score was calculated for all respondents. For the analysis DDI scores were split into higher/lower willingness across the median score.

Current psychological distress (GHQ 12)

The short version of the General Health Questionnaire (GHQ12) was used as a measure of psychological distress in the last few weeks. This questionnaire has been widely used as a screening measure to assess psychological distress in community samples (e.g. Shaw et al. 1999). The Likert scoring system was used which scores items on a scale of 0-1-2-3 with a score range of 0–36.

Barriers to general practice use

Possible barriers to seeking help from GPs were explored. Respondents were asked if any of the following prevented them from seeing a GP in the past 12 months: transportation; cost of visit; it takes too much time; embarrassment / feeling awkward; it's not helpful; too ill; anything else; nothing prevented me. Responses were coded as yes or no.

Results

Descriptive statistics were used to explore gender differences in self-reported mental health problems. Cross-tabulations were used to explore relationships between seeking help for mental or emotional problems from GPs and socio-demographic, health and psychosocial variables. Logistic regression was used to explore the predictors of help seeking for males and females who self reported mental health problems.

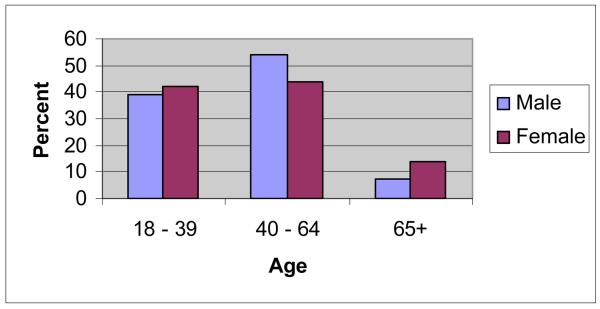

Of the 382 respondents who reported mental health problems in the previous year, 40.6% (155) were male and 59.4% (227) were female. There was a significant difference in self-reported mental heath problems in males and females across the age groups [χ2 (2) = 6.20, p < 0.04]. Figure 1 shows the gender by age pattern in self-reported mental health. The majority of the males reporting mental health problems were in the middle age group with few men over the age of 65 years reporting such problems. In contrast, while the greatest majority of females reported mental health problems in the middle age groups, a significant number of those aged 65+ years reported problems.

Figure 1.

Figure showing the percentage of males and females reporting mental health problems across age categories

The mean GHQ 12 score for the sample was 15.6 (SD 5.7). There was a significant difference in the mean GHQ 12 score for males (14.6, SD 5.1) and females (16.2, SD 6.0), with females showing a greater distress [t (369) = −2.7, p < 0.01].

Almost 60% of the sample reporting mental health problems had contacted their GP for such problems in the previous year (n=225, 59.5%) [χ2 (1) = 1275.121, p < 0.000]. A higher percentage of females (63.2%) reported speaking to the GP in previous year specifically for mental health problems than males (54.2%). This difference failed to reach significance [χ2 (1) = 3.09, p = 0.07].

Separate cross-tabulations were run for males and females. All socio-demographic, health and psychosocial variables were entered in cross-tabulations for males and females.

Table 1 below shows the results of cross-tabulations for female respondents self-reporting mental or emotional problems in the previous year.

Table 1.

Weighted numbers and percentages of female respondents self-reporting a mental, nervous or emotional problem by seeking help from a GP for such a problem in the previous year and by socio-demographic and health variables

| Socio-demographic and health variables |

Contacted GP | Did not contact GP |

Significance | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | % | N | % | X2 | P value | |

| Limitations in physical activities: |

141 | 100 | 82 | 100 | 8.121 | 0.004** |

| None | 45 | 31.9 | 42 | 51.2 | ||

| Some | 96 | 68.1 | 40 | 48.8 | ||

| Limitations in social activities: |

140 | 100 | 82 | 100 | 9.561 | 0.002** |

| None | 52 | 37.1 | 48 | 58.5 | ||

| Some | 88 | 62.9 | 34 | 41.5 | ||

| Access to free medical care: | 135 | 100 | 80 | 100 | 3.964 | 0.046* |

| No | 57 | 42.2 | 45 | 56.3 | ||

| Yes | 78 | 57.8 | 35 | 43.8 | ||

| Education level (CSO): | 132 | 100 | 75 | 100 | 2.569 | 0.277 |

| Primary | 76 | 57.6 | 41 | 54.7 | ||

| Completed secondary | 34 | 25.8 | 26 | 34.7 | ||

| Completed third | 22 | 16.7 | 8 | 10.7 | ||

| Employment status: | 139 | 100 | 78 | 100 | 0.004 | 0.948 |

| Employed/home duties/retired/training |

111 | 79.9 | 62 | 79.5 | ||

| Unemployed/sick | 28 | 20.1 | 16 | 20.5 | ||

| Marital status: | 141 | 100 | 83 | 100 | 0.301 | 0.583 |

| Married/cohabiting | 66 | 46.8 | 42 | 50.6 | ||

| Single/separated/divorced/ widowed |

75 | 53.2 | 41 | 49.4 | ||

| Self-reported physical health: | 141 | 100 | 82 | 100 | 0.862 | 0.353 |

| Good | 53 | 37.6 | 36 | 43.9 | ||

| Less than good | 88 | 62.4 | 46 | 56.1 | ||

| Self-reported quality of life: | 140 | 100 | 82 | 100 | 2.993 | 0.084 |

| Good | 55 | 39.3 | 42 | 51.2 | ||

| Less than good | 85 | 60.7 | 40 | 48.8 | ||

| Size of location of household (CSO): |

140 | 100 | 79 | 100 | 0.007 | 0.932 |

| Rural <1500 population | 40 | 28.6 | 23 | 29.1 | ||

| Urban 1500+ population | 100 | 71.4 | 56 | 70.9 | ||

| Too embarrassed to see GP | 141 | 100 | 82 | 100 | 0.226 | 0.635 |

| No | 130 | 92.2 | 77 | 93.9 | ||

| Yes | 11 | 7.8 | 5 | 6.1 | ||

| Age groups in years | 141 | 100 | 82 | 100 | 1.305 | 0.521 |

| 18-39 | 57 | 40.4 | 37 | 45.1 | ||

| 40-64 | 61 | 43.3 | 36 | 43.9 | ||

| 65+ | 23 | 16.3 | 9 | 11.0 | ||

| Weekly net household income (euros) |

127 | 100 | 73 | 100 | 2.099 | 0.147 |

| 750+ | 28 | 22.0 | 10 | 13.7 | ||

| Up to 749 | 99 | 78.0 | 63 | 86.3 | ||

| Distress Disclosure Index (DDI) median split |

141 | 100 | 82 | 100 | 0.009 | 0.926 |

| Low DDI | 61 | 43.3 | 36 | 43.9 | ||

| High DDI | 80 | 56.7 | 46 | 56.1 | ||

| Lack of transportation to see GPa |

141 | 100 | 82 | 100 | 2.369 | 0.124 |

| No | 137 | 97.2 | 82 | 100 | ||

| Yes | 4 | 2.8 | 0 | 0 | ||

| Too costly to see GP | 140 | 100 | 82 | 100 | 1.197 | 0.294 |

| No | 119 | 85.0 | 65 | 79.3 | ||

| Yes | 21 | 15.0 | 17 | 20.7 | ||

| No time to see GP | 141 | 100 | 83 | 100 | 0.155 | 0.693 |

| No | 128 | 90.8 | 74 | 89.2 | ||

| Yes | 13 | 9.2 | 9 | 10.8 | ||

| GP not helpfula | 141 | 100 | 82 | 100 | 6.089 | 0.014* |

| No | 131 | 92.9 | 82 | 100 | ||

| Yes | 10 | 7.1 | 0 | 0 | ||

| Too ill to see GPa | 141 | 100 | 82 | 100 | 3.227 | 0.072 |

| No | 132 | 93.6 | 81 | 98.8 | ||

| Yes | 9 | 6.4 | 1 | 1.2 | ||

p < 0.25

p < 0.05

cells have expected counts of less than 5.

Only four socio-demographic and psychosocial variables were found significant at 0.05 level for female respondents: self-perceived limitations in physical and social activities, having access to free medical care, and GP not perceived as helpful (Table 1). Unfortunately due to the small numbers of responses (see Table 1), whereby 25% of the cells have a count of less than 5, this variable could not be used for further analysis.

Table 2 shows the results of cross-tabulations for the male respondents.

Table 2.

Weighted numbers and percentages of male respondents self-reporting a mental, nervous or emotional problem and seeking help from a GP for such a problem in the previous year by socio-demographic and health variables

| Socio-demographic, health and psychosocial variables |

Contacted GP | Did not contact GP |

Significance | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number | % | Number | % | X2 | P value | |

| Limitations in physical activities: | 84 | 100 | 70 | 100 | 24.188 | 0.000** |

| None | 22 | 26.2 | 46 | 65.7 | ||

| Some | 62 | 73.8 | 24 | 34.3 | ||

| Limitations in social activities: | 84 | 100 | 71 | 100 | 9.085 | 0.003** |

| None | 26 | 31.0 | 39 | 54.9 | ||

| Some | 58 | 69.0 | 32 | 45.1 | ||

| Access to free medical care: | 84 | 100 | 70 | 100 | 8.486 | 0.004** |

| No | 33 | 39.3 | 26 | 37.1 | ||

| Yes | 51 | 60.7 | 44 | 62.9 | ||

| Education level (CSO): | 82 | 100 | 66 | 100 | 13.851 | 0.001** |

| Primary | 59 | 72.0 | 30 | 45.5 | ||

| Completed secondary | 12 | 14.6 | 27 | 40.9 | ||

| Completed third | 11 | 13.4 | 9 | 13.6 | ||

| Employment status: | 84 | 100 | 71 | 100 | 17.811 | 0.000** |

| Employed/home duties/retired/training |

37 | 44.0 | 55 | 77.5 | ||

| Unemployed/sick | 47 | 56.0 | 16 | 22.5 | ||

| Marital status: | 84 | 100 | 71 | 100 | 9.003 | 0.003** |

| Married/cohabiting | 59 | 70.2 | 33 | 46.5 | ||

| Single/separated/ divorced/ widowed |

25 | 29.8 | 38 | 53.5 | ||

| Self-reported physical health: | 84 | 100 | 69 | 100 | 8.224 | 0.004** |

| Good | 34 | 40.5 | 44 | 63.8 | ||

| Less than good | 50 | 59.5 | 25 | 36.2 | ||

| Self-reported quality of life: | 84 | 100 | 70 | 100 | 12.294 | 0.000** |

| Good | 29 | 34.5 | 44 | 62.9 | ||

| Less than good | 55 | 65.5 | 26 | 37.1 | ||

| Size of location of household (CSO): | 80 | 100 | 68 | 100 | 4.629 | 0.031* |

| Rural <1500 population | 28 | 35.0 | 13 | 19.1 | ||

| Urban 1500+ population | 52 | 65.0 | 55 | 80.9 | ||

| Too embarrassed to see GP | 84 | 100 | 71 | 100 | 3.570 | 0.059 |

| No | 78 | 92.9 | 59 | 83.1 | ||

| Yes | 6 | 7.1 | 12 | 16.9 | ||

| Age groups in yearsa | 85 | 100 | 70 | 100 | 0.424 | 0.809 |

| 18-39 | 31 | 36.5 | 29 | 41.4 | ||

| 40-64 | 48 | 56.5 | 36 | 51.4 | ||

| 65+ | 6 | 7.1 | 5 | 7.1 | ||

| Weekly net household income (euros) | 80 | 100 | 66 | 100 | 0.793 | 0.373 |

| 750+ | 19 | 23.8 | 20 | 30.3 | ||

| Up to 749 | 61 | 76.3 | 46 | 69.7 | ||

| Distress Disclosure Index (DDI) median split | 84 | 100 | 71 | 100 | 0.016 | 0.898 |

| Low DDI | 47 | 56.0 | 39 | 54.9 | ||

| High DDI | 37 | 44.0 | 32 | 45.1 | ||

| Lack of transportation to see GPa | 85 | 100 | 70 | 100 | 0.019 | 0.890 |

| No | 84 | 89.8 | 69 | 98.6 | ||

| Yes | 1 | 1.2 | 1 | 1.4 | ||

| Too costly to see GP | 85 | 100 | 70 | 100 | 0.145 | 0.703 |

| No | 78 | 91.8 | 63 | 90.0 | ||

| Yes | 7 | 8.2 | 7 | 10.0 | ||

| No time to see GP | 84 | 100 | 71 | 100 | 1.516 | 0.218 |

| No | 80 | 95.2 | 64 | 90.1 | ||

| Yes | 4 | 4.8 | 7 | 9.9 | ||

| GP not helpfula | 84 | 100 | 70 | 100 | 0.839 | 0.360 |

| No | 83 | 98.8 | 70 | 100 | ||

| Yes | 1 | 1.2 | 0 | 0 | ||

| Too ill to see GPa | 84 | 100 | 71 | 100 | 1.713 | 0.191 |

| No | 82 | 97.6 | 71 | 100 | ||

| Yes | 2 | 2.4 | 0 | 0 | ||

p < 0.25

p < 0.05

cells have expected counts of less than 5.

As can be seen from Table 2, nine socio-demographic, health and psychosocial variables were found significant at 0.05 level in cross-tabulations: limitations in physical and social activities, having access to free medical care, education level, employment status, marital status, self-reported physical health, self-reported quality of life, and size of location of household (urban/rural). In addition, the self-reported barrier ‘too embarrassed to see GP’ was significant at 0.059 level in cross-tabulations.

Multivariate analysis: Logistic regression for males and females

Logistic regression analysis was used to explore the influence of identified health and socio-demographic factors on female and male respondents' decision to seek help from a GP. Health, psychosocial and socio-demographic variables found statistically significant at 0.05 levels in cross tabulations for males and females were included into the multivariate logistic regression analysis.

Both automatic (forward selection and backward elimination) and manual enter model building was used for the robustness of the analysis. Likelihood ratio (LR), beta weights and significance level (Nourusis, 2006) were checked for model-building. The Hosmer and Lemeshow tests were used to evaluate the goodness of fit of the models. We tried to find the most parsimonious solutions which explained as much variance as possible, had a good fit and maintained theoretically important variables at significance level not exceeding 0.25 (Hosmer and Lemeshow, 2000).

Females

Due to the small number of variables found significant in cross-tabulations (see Table 1) manual model building by enter was used for the prediction of help-seeking among female respondents. First, all three variables found significant at 0.05 in cross-tabulations (see Table 1) were entered in the logistic regression model predicting help-seeking for emotional or mental problem for females. These variables were limitations in physical activities, limitations in social activities, and access to free medical care. None of the three variables remained significant at 0.25 level in this model. The least significant variable (p=0.329) was limitations in physical activities. After this variable was removed, limitations in social activities and access to free medical care became significant at 0.25 level.

Table 3 shows the final logistic regression model of predicting help seeking for mental and emotional problems for female respondents.

Table 3.

Logistic regression model predicting seeking help from GP for mental, nervous or emotional problems for those reporting experiencing mental health problems in the previous year on the basis of health and socio-demographic variables for female respondents

| Predictors | ß | S.E. | Odds Ratio |

95% CI | Sig. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Limitations in social activities (Reference: No limitations) |

|||||

| Some limitations | 0.707 | 0.298 | 2.029 | 1.132, 3.637 | 0.018** |

|

Access to free medical care (Reference: No) |

|||||

| Yes | 0.396 | 0.298 | 1.486 | 0.829, 2.664 | 0.184* |

| Constant | −0.050 | 0.230 | 0.951 | 0.829 |

p < 0.25

p < 0.05

Only two factors stayed in the final model determining seeking help from GP for females: perceived limitations in social activities due to mental or emotional problems, and access to free medical care. The Nagelkerke R2 value of 0.061 (Cox & Snell R2 = 0.045) indicated that around 6.1% of the variance in seeking help from a GP for a mental or emotional problem by females was explained by the combination of the two variables. The Hosmer-Lemeshow test result of 0.713 confirmed that the model had an excellent fit. Female respondents who reported some limitations in their social activities due to mental or emotional problems (OR=2.029) were twice as likely to seek help from a GP than female respondents who did not report such limitations. Females who had access to free medical care were about 1.5 times more likely (OR=1.486) to contact GP than females who did not have access to free medical care. Overall, out of 233 cases (95.9% of the total female sample self-reporting mental or emotional problem included in logistic regression analysis), membership of 62.1% cases was predicted correctly.

Males

All nine socio-demographic and psycho-social variables found significant in cross-tabulations for males (Table 2) were entered in the logistic regression model. In addition, the variable ‘too embarrassed to see GP’ was also added in the logistic regression due to its borderline significance in cross-tabulations (p=0.059) and theoretical value.

Due to a relatively high number of variables (n=10) it was decided to perform automated model building for the prediction of help-seeking among male respondents. Likelihood ratio (LR) forward selection and backward elimination with a significance level of for inclusion of 0.15 (Nourusis 2006) were used for this purpose. The outcome of forward selection and backward elimination was slightly different and it was decided to follow up the automated analysis with the manual enter model building.

Variables not adding significantly to the model at least at 0.25 level were removed from the model in the following order: limitations in social activities (p= 0.572, ß = − 0.387), and self-reported physical health (p=0.356, ß = − 0.504). The Hosmer and Lemeshow tests were used throughout the manual model building to evaluate the goodness of fit of the model. Though self-reported quality of life variable was significant at 0.25 level (p=0.194), the Hosmer and Lemeshow test showed that the model had a bad fit (p=0.008). As this variable was adding the least to the model compared to all the remaining variables (ß=0.618, Wald=1.685) and was the least significant in the model (p=0.194) it was decided to remove it from the model. After removal of the quality of life variable, Hosmer and Lemeshow test showed that the model had excellent fit (p=0.294), explained the highest percentage of the variance compared to the previous models and was accepted as final.

Table 4 presents the final model of seeking help from a GP for psychological problems for males.

Table 4.

Logistic regression model predicting seeking help from GP for mental, nervous or emotional problems on the basis of health, psychosocial and socio-demographic variables for male respondents

| Predictors | ß | S.E. | Odds Ratio |

95% CI | Sig. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Embarrassment (reference: embarrassed to seek help from GP) |

1.928 | 0.654 | 6.873 | 1.906, 24.779 | 0.003** |

| Not embarrassed | |||||

|

Limitations in physical activities (Reference: No limitations) |

|||||

| Some limitations | 1.203 | 0.453 | 3.331 | 1.370, 8.096 | 0.008** |

|

Marital status (Reference: single/separated/divorced/widowed) |

|||||

| Married/cohabiting | 1.007 | 0.477 | 2.738 | 1.075, 6.974 | 0.035** |

|

Employment status (Reference: employed/studying/domestic duties) |

|||||

| Unemployed/sickness/disability | 0.967 | 0.545 | 2.630 | 0.904, 7.650 | 0.076* |

| Access to free medical care | |||||

| (Reference: No) | |||||

| Yes | 0.929 | 0.524 | 2.533 | 0.907, 7.075 | 0.076* |

|

Educational level (Reference: third level) |

0.087* | ||||

| Primary/uncompleted secondary | −0.543 | 0.627 | 0.581 | 0.170, 1.988 | 0.387 |

| Secondary/leaving certificate | −1.516 | 0.738 | 0.220 | 0.052, 0.933 | 0.040** |

|

Size of location of household (Reference: urban 1,500+ population) |

|||||

| Rural < 1,500 population | 0.842 | 0.495 | 2.322 | 0.789, 6.133 | 0.089* |

| Constant | −3.078 | 0.900 | 0.046 | 0.001** |

p < 0.25

p < 0.05

As can be seen from Table 4, seven variables were left in the final model: embarrassment, limitations in physical activities, marital status, employment status, having access to free medical care, location/size of the household and level of education. A total of 42.5% of the variance in help-seeking behaviour for males (Nagelkerke R2 =0.425, Cox & Snell R2 = 0.318) was explained by the combination of these variables. The results of the Hosmer-Lemeshow test of 0.294 showed that the data fit the model quite well. Out of 115 cases (89.1% of the male sample included in the regression analysis), membership of 75.1% cases was predicted correctly.

The strongest predictor of help-seeking from GP for males was self-reported embarrassment associated with seeking help from GP. Male respondents who did not report that they were embarrassed to seek help from GP were nearly seven times more likely to contact their GP, compared to those who did report such embarrassment (OR=6.873).

The second strongest predictor was self-perceived limitations in physical activities, whereby male respondents who felt that their physical activities were affected were over three times more likely to seek help (OR=3.331).

Marital status was also a significant predictor for males seeking help from GP for mental or emotional problems. Male respondents who were married/cohabiting were almost three times more likely to contact the GP for emotional or mental problem (OR=2.738), than males who were without a partner (single/separated/divorced/widowed).

Males who were unemployed or with sickness/disability were over two and a half times more likely (OR=2.630) to seek help compared with employed/occupied/retired males.

Similarly to the female model, access to free medical care was a strong predictor of help-seeking for male respondents, even more so than for female (see Table 3). Male respondents were about 2.5 times more likely (OR=2.533) to contact GP for help with mental or emotional problems, than males who did not have access to free medical care.

Educational status was also a significant predictor of help-seeking for male respondents with self-reported mental health problems. Those with completed secondary education were over four times less likely (OR=0.220) to seek help from GPs, compared to those with a third level education. Interestingly, the difference in the odds for help-seeking between those with primary/uncertified secondary and those with a third level of education (OR=0.581) was not significant in this model (p=0.387).

Finally, size of location of household was found to be an important factor influencing help-seeking of male respondents in this model. Male respondents living in less populated areas (1,500 persons or less) were more than twice more likely to seek help from their GP for mental or emotional problems, compared to males living in urban areas with 1,500 or more population (OR=2.322).

Discussion

In line with previous health surveys a greater proportion of females than males self-reported mental health problems and also showed higher levels of current psychological distress (e.g. National Centre for Social Research, 2003; Northern Ireland Statistics and Research Agency, 2002). The distribution of mental heath problems across the age categories also differed by gender. The findings showed that females in the older age of 65+ years were more likely to report mental health problems than their male counterparts. Analysis of the GHQ 12 scores which measures current psychological distress showed that the sample were experiencing moderate levels of distress, and females were experiencing relatively higher levels of distress than males. Previous research has found that women are more likely to experience depression while men are more likely to report alcohol problems (Kessler et al, 1994). However there is gender bias and stereotyping evident in the diagnosis and treatment of mental health problems that limit the interpretation of gender differences in mental health. It is reported that women are more likely to be diagnosed with depression than men even when they have similar objective scores on measures of depression (Stoope et al, 1999). They are also more likely to be prescribed medication (Simoni-Wastila, 2000). Men are less likely to disclose common mental health problems such as depression due to social stigma and constrained help seeking in line with their stereotypical roles (World Health Organisation, 2009). A recent study in Ireland, using the Distress Disclosure Index, showed that females were more willing to disclose distressing information to others (Ward et al, 2007). Furthermore age can influence the willingness to disclose personal information with older people being less willing to disclose than younger age groups (Ward et al, 2007). Our findings showed that older men reported fewer mental health problems than females in the survey. We had included a measure of the willingness to disclose in this analysis and it was not a significant predictor of help-seeking for males or females. However there may be an interaction between gender and age in the willingness to disclose. Finally, studies have shown links between mental health at the individual level and deprivation at the area level (Zubrick, 2007). Therefore men who are less educated and living in more deprived condition may be even less willing to disclose distressing information due to increased self stigma in these subgroups. In fact our findings showed that males who were higher educated were more likely to seek help.

The results of this study support previous research on help seeking and add to the findings of the existing literature. Research has shown a treatment gap for those with mental illnesses (The ESEMeD / MHEDEA 2000 Investigators, 2004). These findings suggest that there is also a treatment gap for those with self reported common mental health problems. Just over 40% of respondents did not seek help from formal healthcare sources for their problems. While we have no indication of the severity of the problems or the perceived need for help, the GHQ 12 scores suggest that those reporting mental health problems are still experiencing moderate levels of distress. This finding would suggest the need for some support, although not necessarily requiring the need for formal healthcare services. People may also use families and friends as a means of supports when experiencing mental health problems (European Commission, 2006).

The findings support previously reported gender differences in factors associated with help seeking. There were many more factors, both sociodemographic and psychological, associated with seeking help from the GP in the male respondents. Furthermore variables for the male sample predicted much more of the variance than that for the female model. The model for females included only two variables, limitations in social activities and access to free healthcare. Access to free medical care was also a strong predictor of seeking help for males, even more so, than for females. In contrast, the cost of attending the GP did not influence help seeking. Thus it would appear that free health care can influence use, but that for those who have to pay for healthcare, cost did not greatly influence use. This is supported by previous research in Ireland on the impact of income on private patients' access to GP services (Nolan, 2008). This study found that the key difference in GP visiting is eligibility for free healthcare. For those who have to pay a ‘fee for service’ cost does not influence attendance. It would appear that this is the same for those accessing GP services specifically for mental health problems.

The findings showed gender differences in the impact that limitations in day to day activities can have on help seeking. Females were more likely to seek help if they experienced limitations in social activities, while for males limitations in physical activities were a more important influence. This raises the question of the benefits of seeking help earlier and the possible curtailment of problems impacting on daily activities. Previous research has shown that if delay is not sought in the first year of the onset of mental illness then delays of more than ten years are common (WHO, 2009). Literature in the area of physical disability and impairment suggest that limitations in normal physical activities can lead to loss of self-esteem and depression (Schroder et al. 2007). Research from the area of social exclusion suggests that people are less likely to participate in community activities due to mental health problems (European Commission, 2004). Limitations in social and physical activities are likely to lead to withdrawal from the community, which could in turn further exasperate mental health problems. When an individual does seek help it is important that the physician is aware that there may be social or physical limitations and that these are addressed during treatment and care.

Self-reported embarrassment influenced help seeking behaviour rather strongly for males but not females. These findings would suggest that males may be more susceptible to self stigma surrounding seeking help for mental health problems (Vogel & Wade, 2009). Males who reported embarrassment were almost seven times less likely to contact the GP than males who were not embarrassed. Mental health promotion and prevention campaigns need to educate males on the extent of distress in the population and to ‘normalise’ distress in such a way that males do not feel embarrassed about seeking help for such problems (Vogel & Wade, 2009).

Male respondents who were either married or co-habiting tended to seek help from the GP rather than those who were not with a partner. It is possible that the social and emotional support of their wives or partners mediated the male's willingness to seek help despite of the male cultural norms or self stigma associated with seeking help for mental health problems (Vogel & Wade, 2009; Rogler & Hollingshead, 1985). In a study of the Theory of Planned Behaviour, attitudes toward psychological help-seeking were found to mediate the relationships between perceived norm of behaviour and help-seeking intentions (Smith et al. 2008). Attitudes of male respondents who were married could have been mediated by the change of subjective norms of help-seeking behaviour once favourable or unfavourable evaluation was performed. Social or emotional support could have also influenced a person's conception of difficulty or ease in performing help-seeking behaviour.

Following Smith et al. (2008) further education and personal development can also meditate attitudes to help-seeking and broaden one's cultural norms. The finding that males with third level education were more likely to seek help than males with secondary level education supports previous research and at the same time requires further investigation. The benefits of education on psychological well-being are well-documented; it may be advisable to plan more specialised educational activities for males aimed at reducing self-stigma and mediating negative attitudes and embarrassment associated with help-seeking.

Male respondents who were unemployed or had a long-term sickness or disability were also more likely to consult with the GP than their employed or active male counterparts. It is possible that these people had more time or were attending the GP for physical problems and therefore had a greater opportunity of consulting with the GP for mental health problems. In addition, unemployed or disabled males were most probably entitled to free medical care which could also have stimulated their willingness to seek help from GPs.

Interestingly the men who lived in rural areas were more likely to contact their GP than the men in urban areas. This may also be related to a social support network whereby those in rural areas are more likely to know the GP and therefore feel less embarrassed about discussing mental health problems. In addition, the close network of friends and family in rural areas may have influenced the decision to seek help.

It is important to note a number of limitations with the current survey. This was a telephone survey which contacted private households only. As a result those who may be most likely to have experienced a mental health problem (e.g. homeless) may not have been included leading to an underestimation of the extent of mental health problems. It is acknowledged that many people, both males and female, are unwilling to disclose mental health problems because of the stigma surrounding such issues. Therefore undisclosure of problems may have again resulted in underestimation. Furthermore as men are less willing to disclose mental health problems they may have refused to participate in the survey resulting in a biased sample. However the authors feel that this was reduced to some extent as the survey was a telephone survey rather than a face to face survey. Potential respondents may be more willing to participate and to disclose when it is not face to face. The findings also reflect previous findings in terms of the extent of problems and patterns of help seeking, thus adding further confidence in our findings.

The findings have a number of implications. Firstly they suggest that different factors influence males and females to seek help for mental health problems. Policies need to be devised with these differences in mind so that prevention and treatment strategies are gender specific and are aimed at hard to reach groups. These may include both females and males who have to pay for healthcare, employed males, lower educated males and males who have good physical health. For whatever reasons it may be more difficult for these groups to seek help for distress even though they are aware of their mental health problems. Secondly there is a need to highlight the extent of distress in the population so as to normalise these feelings in order to combat some of the stigma surrounding mental health problems (Vogel & Wade, 2009). Distress should be seen as a continuum that may require support at some stage, but that people can experience more or less distress at various points in their life. While GPs are most often the first port of call for formal healthcare services, education should also be provided on the benefits of informal supports such as families and friends. Further research is required to examine the specific reasons why people do not attend the GP for mental health problems including psychological factors, economic factors or social factors. Having this information will allow policies to be specifically aimed at hard to reach groups. Failure to seek help for mental health problems can result in these problems escalating and requiring more intensive treatment at a later date. This not only results in psychological and economics costs for the individual, but also for society.

References

- Courtenany WH. Constructions of masculinity and their influence on men's well being: a theory of gender and health. Social Science and Health. 2000;50:1385–1401. doi: 10.1016/s0277-9536(99)00390-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Department of Health and Children . A Vision for Change. The Stationary Office; Dublin: 2006. [Google Scholar]

- European Commission. Directorate General (SANCO) Mental well-being. 2006. Full report and summary available at http://ec.europa.eu/health/ph_publication/eurobarometers_en.htm.

- European Commission . The state of mental health in the European Union. European Commission; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- ESEMeD / MHEDEA 2000 Investigators Use of mental health services in Europe: results from the European Study of the Epidemiology of Mental Disorders (ESEMeD) project. Psychiatr. Scand. 2004;109(suppl. 420):47–54. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0047.2004.00330.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hosmer D, Lemeshow S. Applied Logistic Regression. John Wiley and Sons; New York: 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Jorm AF, Korten AE, Jacomb PA, Rodgers B, Pollitt P, Christensen H, Henderson S. Helpfulness of interventions for mental disorders: beliefs of health professionals compared with the general public. British Journal of Psychiatry. 1997;171:233–237. doi: 10.1192/bjp.171.3.233. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kahn JH, Hessling RM. Measuring the tendency to conceal versus disclose psychological distress. Journal of Social and Clinical Psyhcology. 2001;20(1):41–65. [Google Scholar]

- Kessler RC, Brown RL, Broman CL. Sex differences in psychiatric help-seeking: evidence from four large scale surveys. Journal of Health and Social Behaviour. 1981;22:49–64. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kessler RC, McGonagle KA, Zhao S. Lifetime and 12 month prevalence of DSM-111-R psychiatric disorders in the United States. Archives of General Psychiatry. 1994;51:8–19. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1994.03950010008002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin E, Parikh SV. Sociodemographic, clinical and attitudinal characteristics of the untreated depressed in Ontario. Journal of Affective Disorder. 1999;53:153–162. doi: 10.1016/s0165-0327(98)00116-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- National Centre for Social Research . Health Survey for England 2003. Crown Publishing; UK: 2004. Full report and summary available at http://www.dh.gov.uk/en/Publicationsandstatistics/Publications/PublicationsStatistics/DH_4098712. [Google Scholar]

- Nolan A. The impact of income on private patients' access to GP services in Ireland. Journal of Health Services Research. 2008;13(4):222–226. doi: 10.1258/jhsrp.2008.008048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Northern Ireland Statistics and Research Agency Northern Ireland Health and Social Wellbeing Survey (2001) 2002. Bulletin No.2. Available to download at http://archive.nics.gov.uk/dfp/mentalhealth&wellbeingbulletinreport.pdf.

- Parslow R, Jorm A. Who uses mental health services in Australia? An analysis of data from the National Survey of Mental Health and Wellbeing. Australian and New Zealand Journal of Psychiatry. 2000;39:997–1008. doi: 10.1080/000486700276. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rogler LH, Cortes DE. Help-seeking Pathways: A Unifying Concept in Mental Health Care. American Journal of Psychiatry. 1993;150(4):554–561. doi: 10.1176/ajp.150.4.554. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rogler LH, Hollingshead AB. Trapped: Puerto Rican Families and Schizophrenia. 3rd ed. Waterfront Press; Maplewood, NJ: 1985. [Google Scholar]

- Schroder C, Johnson M, Morrison V, Teunissen L, Notermans N, van Meereren N. Health Condition, Impairment, Activity Limitations: Relationships With Emotions and Control Cognitions in People with Disabling Conditions. Rehabilitation Psychology. 2007;52(3):280–289. [Google Scholar]

- Shaw CM, Creed F, Tomenson B, Riste L, Cruickshank JK. Prevalence of anxiety and depressive illness and help seeking behaviour in Africa Caribbean and white Europeans: two phase general population survey. British Medical Journal. 1999;318:302–306. doi: 10.1136/bmj.318.7179.302. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simoni-Wastila L. The use of abusable prescription drugs: the role of gender. Journal of Women's Health and Gender Based Medicine. 2000;9:289–297. doi: 10.1089/152460900318470. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simon RW. Revisiting the Relationships among Gender, Marital Status, and Mental Health. American Journal of Sociology. 2002;107(4):1065–1096. doi: 10.1086/339225. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith JP, Tran GQ, Thompson RD. Can the Theory of Planned Behaviour Help Explain Men's Psychological Help-Seeking? Evidence for a Mediation Effect and Clinical Implications. Psychology of Men and Masculinity. 2008;9(3):179–192. [Google Scholar]

- Stoppe G, Sandholzer H, Huppertz C. Gender differences in the recognition of depression in old age. Maturitas. 1999;32:205–212. doi: 10.1016/s0378-5122(99)00024-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tedstone Doherty D, Moran R, Kartalova-O'Doherty Y, Walsh D. HRB National Psychological Wellbeing and Distress Survey: Baseline Results. Health Research Board; Dublin: 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Tudiver F, Talbot Y. Why don't men seek help? Family physicians' perspectives on help-seeking behaviour in men. Journal of Family practice. 1999;48:47–52. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vogel DL, Wade N. Stigma and help-seeking. The Psychologist. 2009;22(1):20–23. [Google Scholar]

- Vogal DL, Wade NG, Haake S. Measuring the self-stigma associated with seeking psychological help. Journal of Counselling psychology. 2006;53:325–337. [Google Scholar]

- Ward M, Tedstone Doherty D, Moran R. It's good to talk: distress disclosure and psychological wellbeing. Health Research Board; Dublin: 2007. [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organisation . Mental Health: A call for Action by World Health Ministers, Gender Disparities in Mental Health. World Health Organisation; Geneva: 2001. [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organisation . Gender in Mental Health Research. World Health Organisation; Geneva: 2004. [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organisation Mental Health Action plan and Declaration for Europe. 2005. http://www.euro.who.int/mentalhealth/publications/20061124_1.

- World Health Organisation and World Organisation of Family Doctors (WONCA) Integrating mental heath into primary care. A global perspective. 2008. http://www.who.int/mental_health/policy/Mental%20health%20+%20primary%20care-%20final%20low-res%20120109.pdf.

- World Health Organisation Gender disparities in mental health. 2009. Available to download at http://www.who.int/mental_health/policy/Mental%20health%20+%20primary%20care-%20final%20low-res%20120109.pdf.

- Zubrick SR. Commentary: Area social cohesion, deprivation and mental health—Does misery love company? International Journal of Epidemiology. 2007. doi:10.1093/ije/dym040. http://ije.oxfordjournals.org/cgi/content/full/dym040v1. [DOI] [PubMed]