Abstract

We report the development of CoMFA analysis models that correlate the 3D chemical structures of 80 compounds with 6-5 fused ring system synthesized in our laboratory and their inhibitory potencies against tgDHFR and rlDHFR. In addition to conventional CoMFA analysis, we used two routines available in the literature aimed at the optimization of CoMFA: all-orientation search (AOS) and cross-validated r2-guided region selection (q2-GRS) to further optimize the models. During this process, we identified a problem associated with q2-GRS routine and modified using two strategies. Thus, for the inhibitory activity against each enzyme (tgDHFR and rlDHFR), five CoMFA models were developed using the conventional CoMFA, AOS optimized CoMFA, the original q2-GRS optimized CoMFA and the modified q2-GRS optimized CoMFA using the first and the second strategy. In this study, we demonstrate that the modified q2-GRS routines are superior to the original routine. On the basis of the steric contour maps of the models, we designed four new compounds in the 2,4-diamino-5-methyl-6-phenylsulfanyl-substituted pyrrolo[2,3-d]pyrimidine series. As predicted, the new compounds were potent and selective inhibitors of tgDHFR. One of them, 2,4-Diamino-5-methyl-6-(2′,6′-dimethylphenylthio)pyrrolo[2,3-d]pyrimidine, is the first 6-5 fused ring system compound with nanomolar tgDHFR inhibitory activity. The HCl salt of this compound was also prepared to increase solubity. Both forms of the drug were tested in vivo in a T. gondii infection mouse model. The results indicate that both forms were active with the HCl salt significantly more potent than the free base.

Keywords: Antifolates, Dihydrofolate Reductase, CoMFA Analysis, Selective Inhibitors

Introduction

Infections caused by opportunistic pathogens Pneumocystis carinii (pc) and Toxoplasma gondii (tg) are the leading cause of morbidity and mortality in immunocompromised patients such as those with AIDS.1 Dihydrofolate reductase (DHFR) inhibitors are the current drugs of choice for the treatment of these infections. Ideally, these drugs should efficiently inhibit the growth of pathogenic cells via DHFR inhibition without affecting the mammalian DHFR. Unfortunately, due to their lack of potency and/or selectivity, combinations of current DHFR inhibitors with other agents such as sulfa drugs are often required for synergistic effects or to decrease host toxicity, which leads to high costs. Discontinuation of therapy is necessary in many cases as a result of severe side effects. Therefore, efforts continue to be directed toward the development of single agents which not only display high potency but are also selective against DHFR from P. carinii and/or T. gondii over mammalian DHFR, such as rat liver (rl) DHFR.1 In recent reports, DHFR inhibitors with a 6-5 fused ring system including furo[2,3-d]pyrimidine, pyrro[2,3-d]pyrimidine and purine derivatives have shown good activity and selectivity against these pathogenic organisms, especially T. gondii.2-15 Computational techniques such as QSAR models can be used to assist the rational design of more potent and selective DHFR inhibitors with 6-5 fused ring system.

Most models for predicting DHFR inhibition in the literature16-46 published to-date use homologous data sets of DHFR inhibitors with a specific heterocyclic core (e.g., quinazolines, pyrimidines). Mattioni et al.47 recently developed QSAR models that correlated chemical structure and inhibition potency for three types of DHFR: rlDHFR, pcDHFR, and tgDHFR. The results, however, did not give structural information about the binding sites.

More recently, Sutherland et al.48 generated comparative molecular similarity indices analysis (CoMSIA) three-dimensional quantitative structure-activity relationship (3D-QSAR) models for the inhibitory activities against pcDHFR and rlDHFR using a data set of 406 structurally diverse DHFR inhibitors. Gangjee and Lin49 also reported comparative molecular field analysis (CoMFA) and CoMSIA analysis of pcDHFR, tgDHFR and rlDHFR based on the biological data of 179 compounds synthesized in our laboratory.49 These are general models for pcDHFR, tgDHFR and rlDHFR inhibitors. Even though some compounds with 6-5 fused ring system were included in the training set and/or test set, the majority of the drugs used in the development of these models were compounds with 6-6 fused ring system, such as quinazolines and pridopyrimidines. In addition, certain monocyclic, tricyclic and tetracyclic compounds were also included in the data sets.

As a continuation of our previous work and the importance of both potency and selectivity associated with the 6-5 fused ring systems, we report the development of CoMFA analysis models that correlate the 3D chemical structures of 80 compounds2, 3, 5-8, 11, 13, 14 with 6-5 fused ring system synthesized in our laboratory and their inhibitory potencies for tgDHFR and rlDHFR. In addition to conventional CoMFA analysis, we used two routines available in the literature aimed at the optimization of CoMFA: all-orientation search (AOS)50 and cross-validated r2-guided region selection (q2-GRS)51 to further optimize the models. During this process, we identified a problem associated with q2-GRS routine and modified it with two different strategies. Thus, for the inhibitory activity against each enzyme (tgDHFR and rlDHFR), five CoMFA models were developed using the conventional CoMFA, AOS optimized CoMFA, the original q2-GRS optimized CoMFA and the modified q2-GRS optimized CoMFA with strategy one and two.

Computational Details

1. Data Set and Biology Activity

The structures of the compounds used to develop the CoMFA model along with their DHFR inhibitory activities are listed in table 1.

Table 1.

Structures and IC50 Values (μM) of the Compounds Used in Developing the Models

| ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cmpd | R | tgDHFR | rlDHFR | Ref. |

| 3 | 3,4,5-(OCH3)3 | 8.1 | 56.3 | 3 |

| 4 | 3,4-(OCH3)2 | 4.3 | 116.0 | 3 |

| 5 | 4-OCH3 | 6.0 | 63.0 | 3 |

| 6 | 2,5-(OCH3)2 | 1.7 | 156.0 | 3 |

| 7 | 2,5-(OC2H5)2 | 5.3 | 70.0 | 3 |

| 8 | 3,4-Cl2 | 1.4 | 14.4 | 3 |

| 9 | 2,3-(CH)4 | 1.1 | 59.3 | 3 |

| 10 | H | 3.9 | >252 | 3 |

| |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cmpd | X | R | tgDHFR | rlDHFR | Ref. |

| 11 | N(CH3) | 2,5-(OCH3)2 | 3.40 | >12.0 | 5 |

| 12 | N(CH3) | 3,4-Cl2 | 1.00 | 3.00 | 5 |

| 13 | N(CH3) | 2,3-(CH)4 | 0.87 | 8.20 | 5 |

| 14 | S | 3,4-(OCH3)2 | 2.60 | 16.7 | 5 |

| 15 | S | 3,4-Cl2 | 11.6 | 5.3 | 5 |

| 16 | S | 2,3-(CH)4 | 0.81 | 3.0 | 5 |

| 17 | S | 3,4-(CH)4 | 9.20 | 82.9 | 5 |

| |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cmpd | n | Ar | tgDHFR | rlDHFR | Ref. |

| 18 | 0 | C6H5 | 28 | 59.9 | 6 |

| 19 | 0 | 3,4,5-(OCH3)3C6H2 | 2.2 | 13 | 6 |

| 20 | 0 | 2,3,4-(OCH3)3C6H2 | 1.8 | 3.7 | 6 |

| 21 | 0 | 2,4,6-(OCH3)3C6H2 | 0.84 | 1.88 | 6 |

| 22 | 0 | 2,4,5-(OCH3)3C6H2 | 1.5 | 7 | 6 |

| 23 | 0 | 2,5-(OCH3)2C6H3 | 1.7 | 3.5 | 6 |

| 24 | 0 | 3,5-(OCH3)2C6H3 | 3.0 | 32.4 | 6 |

| 25 | 0 | 3,4-(OCH3)2C6H3 | 14.2 | 52.3 | 6 |

| 26 | 0 | 2,4-(OCH3)2C6H3 | 2.4 | 0.9 | 6 |

| 27 | 0 | 3,4-Cl2C6H3 | 6.7 | 252 | 6 |

| 28 | 0 | 3,5-(OCH3)2-4-OHC6H2 | 1 | 15.3 | 6 |

| 29 | 0 | 2-NO2-3,4-(OCH3)2C6H2 | 16.8 | >25 | 6 |

| 30 | 0 | 4-C6H5C6H4 | 32.9 | 30.1 | 6 |

| 31 | 0 | 2-naphthyl | 27 | 280 | 6 |

| 32 | 0 | 9-fluorenyl | 30.5 | 29.8 | 6 |

| 33 | 1 | C6H5 | 0.5 | 1.6 | 6 |

| 34 | 1 | NH-2,5-OCH3C6H3 | 49 | >29 | 6 |

| 35 | 1 | S-2-naphtyl | 45 | 107 | 6 |

| |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cmpd | X | Ar | tgDHFR | rlDHFR | Ref. |

| 36 | S | C6H5 | >26 | 252 | 7 |

| 37 | S | 1-naphthyl | 19 | 23 | 7 |

| 38 | S | 2-naphthyl | 11.6 | 12.3 | 7 |

| 39 | NH | 1-naphthyl | 37 | 12 | 7 |

| 40 | NH | 2-naphthyl | 38 | 36.5 | 7 |

| 41 | O | 2-naphthyl | >42 | 60.3 | 7 |

| 42 | NH | 4-C6H5OC6H4 | 32.4 | 16.2 | 7 |

| 43 | NH | 2-C6H5C6H4 | 45.4 | 137 | 7 |

| 44 | N(CH3) | 2-naphthyl | 23.6 | 14.6 | 7 |

| 45 | NH | 2,5-Cl2C6H3 | >47 | 71.9 | 7 |

| 46 | N(CH3) | 3,4,5-Cl3C6H2 | 21.5 | 34.3 | 7 |

| 47 | NH | 1-anthracene | 15.4 | >51 | 8 |

| 48 | NH | 2-fluorene | 27.7 | >10 | 8 |

| 49 | NH | 3-(N-ethylcarbazole) | 4.5 | 12.6 | 8 |

| 50 | NH | 2-(9-hydroxyfluorene) | 63 | >13 | 8 |

| 51 | N(CH3) | 3-(2-methoxydibenzofuran) | 392 | 241 | 8 |

| 52 | N(CH3) | 3-(N-ethylcarbazole) | 22.6 | 24.7 | 8 |

| 53 | S | 2-biphenyl | 105 | 49 | 8 |

| 54 | S | 3-biphenyl | 23 | 31 | 8 |

| 55 | S | 4-biphenyl | 79 | 351 | 8 |

| 56 | S | 2-C6H5OC6H5 | 38 | 18 | 8 |

| 57 | S | 3-C6H5OC6H5 | 19 | 39 | 8 |

| 58 | S | 4-C6H5OC6H5 | 259 | 65 | 8 |

| ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cmpd | R | tgDHFR | rlDHFR | Ref. |

| 59 | 2,3-(CH)4 | 0.16 | 4.57 | 11 |

| 60 | 3-Cl | 6.94 | 47.7 | 11 |

| 61 | 4-Cl | 8.93 | 19 | 11 |

| 62 | 2-OCH3 | 1.02 | 2.32 | 11 |

| 63 | 3-OCH3 | 4.76 | 2.06 | 11 |

| 64 | 4-OCH3 | 2.69 | 31.3 | 11 |

| 65 | 2,4-Cl2 | 20 | 110 | 11 |

| 66 | 2,5-(OCH3)2 | 0.17 | 7.8 | 11 |

| ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cmpd | R | tgDHFR | rlDHFR | Ref. |

| 67 | 2,3-(CH)4 | 18.8 | 40 | 13 |

| 68 | 4-Cl | 31.8 | 37.4 | 13 |

| 69 | 3,4-(CH)4 | 31 | 31 | 13 |

| 70 | 3-Cl | 76.8 | 64 | 13 |

| 71 | 2,4-Cl2 | 28.2 | 34.6 | 13 |

| 72 | 2,5-(OCH3)2 | 87 | >46 | 13 |

| 73 | H | 81 | >33 | 13 |

2. Structure Alignment

The pcDHFR bound structures of 81 (PDB 1daj)52 (Figure 1) was used as the template. For each class of compounds only the structure with the plain phenyl side chain was flexibly fit to the template in MMFF94 force field using the Flexible Align module implemented in MOE 2004.0353 with the default options followed by the addition of the substituents on the phenyl in a consistent fashion, with preference for the solvent-exposed edge of the phenyl ring: the 2′-position was occupied before the 6′-position and the 3′-position before the 5′-position, with the ortho position taking precedence over the meta position when both are substituted. The newly added substituents were then relaxed in MOE with the rest of the molecule being fixed using MMFF94 force field with default option. The resulting structures were exported as MOL2 files and were subsequently imported into Sybyl 7.0,54 followed by the calculation of Gasteiger-Hückel charges. The hydrogen atoms of each molecule were further optimized, while the heavy atoms were held still, with a gradient convergence of 0.05 kcal/Å and up to 1000 iterations using the Powell method in the TRIPOS force field. The final compound aggregate is shown in Figure 2.

Figure 1.

The structure and pcDHFR bound conformation of 81

Figure 2.

The compound aggregate. (A) front view; (B) top view.

3. Training set and test set

Among the 80 compounds listed in Table 1, 76 compounds were active (had detectable IC50 values) against tgDHFR and 71 compounds were active against rlDHFR. A dataset containing only the active compounds against a particular enzyme were used to develop the CoMFA model. A diversity subset55 which contained approximately 20% of the compounds (14 for rlDHFR and 15 for tgDHFR) with the farthest distance from the least active compound based on the 2-D fingerprints (MACCS Structural Keys bit packed version) using Tanimoto coefficient55 as the similarity metric were extracted using MOE and was used as the test set. The remaining compounds were used as the training set. This was carried out to make sure that the test set is diverse enough to justify the models. Instead of the least active compound, any compound within the dataset could have be chosen to calculate the diversity subset, however, we used the least active compound here in all cases just to be consistent.

4.1 Conventional CoMFA

CoMFA was performed using the QSAR module in Sybyl 7.0. For each training set compound, the CoMFA descriptors, steric (Lennard-Jones 6-12 potential) and electrostatic (Coulombic potential) field energies were calculated using the SYBYL default parameters. The CoMFA region was defined to extend beyond the van der Waals envelopes of all molecules by 4.0 Å along the principal axes of the Cartesian coordinate system. A distance dependent dielectric constant was used. An sp3 carbon atom with +1.0 charge was used as the probe atom to calculate steric and electrostatic fields. The steric and electrostatic contributions were truncated at 30 kcal/mol, and electrostatic contributions were dropped at lattice intersections with maximum steric interactions. The CoMFA steric and electrostatic fields generated were scaled by the CoMFA standard option in SYBYL. In order to improve the cross-validated q2 to an acceptable level, a small number of outliers were dropped from the training set.

4.2 All-Orientation Search (AOS) CoMFA

As first reported by Cho et. al,51 the cross-validated r2 (q2) value of CoMFA analysis, which serves as a quantitative measure of the predictivity, fluctuates with the orientation of the aligned molecular aggregate on the computer screen by up to 0.5 q2 unit. The reason for this fluctuation in q2 values lies in the fact that conventional CoMFA samples the continuous molecular field at discrete lattice points and calculates the steric and electrostatic field energies at each lattice point with distance-sensitive functions, such as the Lennard-Jones 6-12 potential. When the molecular aggregate rotates, so does the molecular field surrounding the aggregate. The lattice box in CoMFA, however, is always axis-aligned and does not rotate along with the field. Thus, different points in the same molecular field are mapped onto the lattice points resulting in different field energy values. These values, when processed subsequently by partial least squares (PLS) to produce the final model causes a variation in the q2 value and, consequently, the predictivity of the model.

The AOS routine50 optimizes the field sampling by rotating the molecular aggregate systematically and picking the orientation that produces the highest q2 value. The details of the AOS routine were described previously elsewhere.50 Briefly, the compounds aggregate was rotated about the x, y, and z axes systematically with an increment of 30° using the STATIC ROTATE command in Sybyl. For each orientation, a conventional CoMFA was performed as described above and the predictive value of the model was evaluated using leave-one-out (LOO) cross-validation with sample-distance partial least squares (SAMPLS). The orientation that gave the highest q2 value was selected to produce the final model. A Sybyl Programming Language (SPL) script was written to perform the AOS routine as described50 automatically. For the inhibitory activity against each enzyme, a new model was obtained by optimizing the model generated with the conventional CoMFA using the AOS routine.

4.3 The Original q2-GRS CoMFA

The q2-GRS routine was developed by Cho et al.51 to overcome the deficiency of CoMFA analysis mentioned above. The q2-GRS routine first subdivides the rectangular box obtained initially with conventional CoMFA, which, as mentioned above, extends beyond the van der Waals envelopes of all molecules by 4.0 Å along the principal axes of the Cartesian coordinate system, into 125 small boxes and perform 125 independent analyses using probe atoms placed within each box with the step size of 1.0 Å. Followed by the selection of only those small boxes for which a q2 is higher than a specified optimal cutoff value (default 0.1). Finally, CoMFA analysis is repeated with the combined region of small boxes selected at the previous step to generate the final model.

Cho et al.51 argued that it is contradictory for the conventional CoMFA routine to emphasize the limited areas of three-dimensional space as important for biological activity in the final result even though it assumes equal importance of all lattice points during the PLS analysis, which happens to be the calculation that leads to the final result. Thus q2-GRS was designed to eliminate those areas of three-dimensional space where changes in steric and electronic fields do not correlate with changes in biological activity from the analyses. For the inhibitory activity against each enzyme, a new model was obtained by optimizing the model generated with the conventional CoMFA using the original q2-GRS routine.

4.4 The Modified q2-GRS CoMFA

A close inspection of the final combined region file generated by the original q2-GRS routine revealed a potential problem. For the training set of tgDHFR, the region box generated by conventional CoMFA has a dimension of 19.95 Å × 20.49 Å × 18.66 Å. If this region were to be defined using 1 Å as step size, there would be 20 × 21 × 19 = 7980 lattice points. In the final combined region generated by q2-GRS using the default parameters, 74 boxes or subregions (59.2%) of the total 125 were selected and the rest 51 boxes (40.8%) were eliminated. Each of the subregions had the dimension of one fifth of the region box generated by conventional CoMFA. In this case, it is 3.99 Å × 4.10 Å × 3.73 Å. Thus, each box contained 5 × 5 × 4 = 100 grid points. Thus the total number of grid points in the combined region is 74 × 100 = 7400 grid points, which is 96.5% of the total 7980 lattice points found in the conventional CoMFA region box. Apparently, the original q2-GRS routine forced 92.7% of the lattice points into 59.2% of the space. In the conventional CoMFA region, the distance between any given pair of immediately adjacent grid points is 1 Å. In the combined region generated by the original routine of q2-GRS, in order to fit more grid points into the space, the distance between some of the lattice points must be less than 1 Å. Since within each subregion, the distance of any given pair of immediately adjacent to each other is also 1 Å, the shorter distances could only occur between grid points from adjacent boxes.

To understand this behavior of the original q2-GRS routine, let us consider a putative cubic region box, whose lowest corner is at (0, 0, 0) in the Cartesian space, with the dimension of 21.5 Å × 21.5 Å × 21.5 Å. From our observation, CoMFA normally rounds the dimensions down to the nearest integers. If the decimal part of a dimension is equal to or greater than 0.99, however, CoMFA treats this dimension as the rounded up integer, for example, 21.99 will be rounded up to 22 whereas 21.989 will still be rounded down to 21. Thus, the dimension of the conventional CoMFA grid in our example would be 21 Å × 21 Å × 21 Å and the number of grid points would be 223 = 10648.

The q2-GRS routine divides the region box into 125 subregions. As in our example, the size of each subregion box is 4.3 Å × 4.3 Å × 4.3 Å. CoMFA treats each individual subregion the same way as the conventional region box. In our example, the size of the grid within each subregion is rounded down to 4 Å × 4 Å × 4 Å. The number of grid points within each subregion is 53 = 125. Assuming that all the subregions are selected in the final combined region, there would be a total of 1252 = 15625 grid points. That is 47% more than the 10648 grid points in the conventional CoMFA grid. As shown in Figure 3, the closest distance occurs between the grid points at the opposite side of the border of two adjacent subregions. This distance is the decimal part of the dimension of the subregion, as in our example, it is 0.3 Å. Apparently, in the worst case scenario, this distance could be 0 Å, and in this extreme scenario some of the grid points would be counted twice, thrice or more (up to eight times).

Figure 3.

Front view of the q2-GRS grids (black), Apparently, these grids do not coincide with that of the conventional CoMFA, and the distances between the grid points at the opposite side of the border (purple) of two adjacent subregions can be much less then 1.0 Å.

Thus, in the final combined region, this uneven distribution of grid points will always be present, unless in the unlikely scenario where none of the selected subregions are adjacent to each other. The original q2-GRS introduces unnecessary weight on the three-dimensional space near the borders of the adjacent subregions by putting more grid points at these sites.

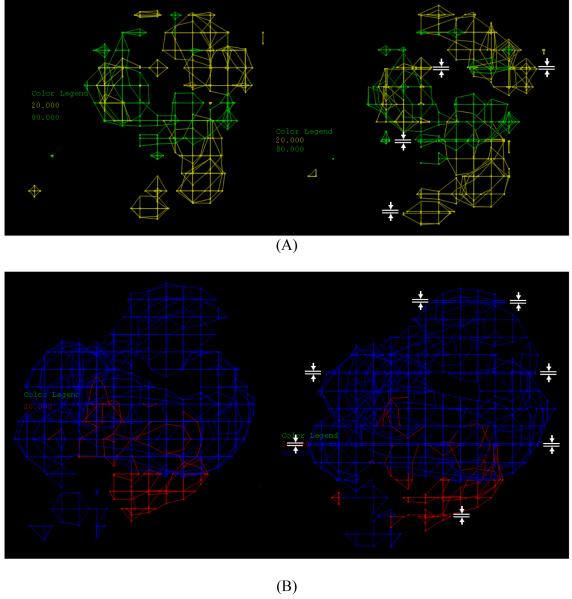

To further illustrate the shortcoming of the original q2-GRS routine, we first conducted a conventional CoMFA analysis of the tgDHFR training set. For this analysis, the step size of the region file was set to 1.0 Å instead of the default 2.0 Å. The q2 of this analysis was 0.627. Next, we did the analysis using the original q2-GRS routine, with the cutoff set to −1000.0 instead of the default 0.1, so that all of the 125 regions were selected in the final region. At only 6.06, the q2 of this analysis was significantly lower than that of the conventional CoMFA analysis. The steric and electrostatic stdev*coefficient contour maps derived from these two analyses were compared in Figure 4. There were areas in the q2-GRS contour maps where the grid points were in close vicinity to each other.

Figure 4.

A comparison of the contour maps of the tgDHFR training set generated with the conventional CoMFA (left) and with the original q2-GRS with the cutoff set at −1000 .0 (so that all subregions are selected) (right). The areas of the q2-GRS contour maps where the grid points are very close to each other (These areas are not present in the conventional CoMFA maps) are highlighted with the white symbols. (A) The steric contour maps, (B) The electrostatic contour maps.

To overcome this problem, we modified the original q2-GRS routine with two different strategies.

In the first strategy, the lowest corner of each modified subregion is the lowest grid point of the conventional CoMFA grid enclosed by the original q2-GRS subregion, and the highest corner of each modified subregion is the highest grid point of the conventional CoMFA grid enclosed within the subregion of the original q2-GRS routine (Figure 5). The advantage of this strategy is that only the grid points of the conventional CoMFA grid would be included in the final combined region.

Figure 5.

Front view of the modified q2-GRS grids using the first strategy (blue), which coincide with that of the conventional CoMFA (green)

We tested this modified routine on the tgDHFR training set by lowering the q2 cutoff to −1000.0 so that all the 125 subregions were included in the final combined region, which gave exactly the same q2 (0.627) as that of the conventional CoMFA (with 1.0 Å as the step size instead of the default 2.0 Å). As shown in Figure 6, except for those gaps between subregions, the stdev*coefficient contour maps derived from this analysis were exactly the same as that of the original CoMFA analysis.

Figure 6.

A comparison of the contour maps of the tgDHFR training set generated with the conventional CoMFA (left) and with the first strategy modified original q2-GRS with the cutoff set at −1000 .0 (so that all subregions are selected) (right). superimposed on their respective region box(es) (cyan) (A) The steric contour maps, (B) The electrostatic contour maps.

The drawback of this strategy is that the size of the subregions varies. In our putative example illustrated in Figure 5, the number of grid points in each subregion varies from 64 to 125, making the subregions less comparable to each other. Therefore, a modification using a second strategy was devised. In this second strategy, the region box is divided into 125 equal-sized subregions and the distance between the adjacent subregions is 1 Å (Figure 7), whereas in the original routine, the adjacent subregions touch each other. In this case, even though the grid points do not match that of the conventional region, the size of the subregions and the number of grid points within these subregions are the same, much like the original routine.

Figure 7.

Front view of the modified q2-GRS subregions (purple) and grids (green) using the second strategy.

This second modified routine was also tested on the tgDHFR training set by lowering the q2 cutoff to −1000.0, which gave a q2 of 0.631; this was slightly higher than that of the conventional CoMFA using step size 1.0 Å (0.627). The stdev*coefficient contour maps from this analysis was compared with the conventional CoMFA in Figure 8.

Figure 8.

Comparison of the contour maps of the tgDHFR training set generated with the conventional CoMFA (left) and with the second strategy modified original q2-GRS with the cutoff set at −1000 .0 (so that all subregions are selected) (right) (A) The steric contour maps, (B) The electrostatic contour maps.

For the inhibitory activity against each enzyme, models were obtained by using both modified q2-GRS routine.

5. PLS Analysis

The CoMFA, descriptors derived above were used as explanatory variables, and pIC50 (−log IC50) values were used as the target variable in PLS regression analyses to derive 3D QSAR models using the implementation in the SYBYL package. The predictive value of the models was evaluated by leave-one-out (LOO) cross-validation with SAMPLS. The cross-validated coefficient, q2, was calculated using eq 1,

| (1) |

where Ypred, Yactual, and Ymean are predicted, actual, and mean values of the target property (pIC50), respectively. is the predictive sum of squares (PRESS). The number of components giving the lowest PRESS value or the optimal number of components (ONC) was used to generate the final PLS regression models. To prevent overfitting, no more than 7 components were allowed. The conventional correlation coefficient r2 and its standard error, s, were subsequently computed for the final PLS models using the following formulae respectively.

| (2) |

| (3) |

Where Y’pred is the predicted value of the target proterty (pIC50) using the final model. The statistical F-test was also performed and the results indicated that all models were statistically significant.

CoMFA coefficient maps were generated by interpolation of the pairwise products between the PLS coefficients and the standard deviations of the corresponding CoMFA descriptor values.

6. Results and Validation

The tgDHFR training set has a total of 61 compounds, which include 2-12, 14-27, 30, 31, 33, 37-39, 42-44, 46-50, 53-55, 57-64, 67-73, 76, 78-80 (Table 1). The tgDHFR test set contains 15 compounds, which are 13, 28, 29, 32, 34, 35, 40, 51, 52, 56, 65, 66, 74, 75 and 77 (Table 1). A total of five models were generated using the conventional CoMFA, AOS optimized CoMFA, the original q2-GRS optimized CoMFA and the modified q2-GRS optimized CoMFA using the first and the second strategy. The key statistical parameters associated with these models are shown in Table 2. The graph the actual pIC50 versus the predicted pIC50 values for the training set and the test set by the five CoMFA models are shown in Figure 9(A)-(E) respectively. The predicted pIC50 values of the training set compounds using the five models as well as the residual values are given in Appendix Table 1, 3, 5, 7, 9 respectively. The predicted pIC50 values of the test set compounds and the residual values using the five models are given in Appendix Table 2, 4, 6, 8, 10 respectively.

Table 2.

Statistical Data for tgDHFR CoMFA Results

| Conventional | AOS | q2-GRS (original) |

q2-GRS (modified 1) |

q2-GRS (modified 2) |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CV-r2 (q2) | 0.639 | 0.699 | 0.622 | 0.639 | 0.647 |

| Opt. no. of comp. | 5 | 7 | 3 | 3 | 3 |

| Std. error of estimate | 0.236 | 0.141 | 0.322 | 0.291 | 0.311 |

| Non-CV-r2 | 0.897 | 0.964 | 0.800 | 0.837 | 0.814 |

| F value | 95.613 | 204.900 | 76.108 | 97.300 | 83.198 |

| Predictive r2 | 0.422 | 0.365 | 0.465 | 0.447 | 0.499 |

Figure 9.

Predictions for the training (●) and test (○) sets for tgDHFR inhibitory activities. The solid line is the regression line for the training set predictions whereas the dotted lines indicate the ±1.0 log margins.

Though, AOS CoMFA gave the best internal cross-validated q2 value 0.699 (ONC =7) among the five models, this q2 value was only obtained with the maximum allowed seven components. Furthermore, the AOS CoMFA model only gave the lowest external predictive r2 (0.365), which was worse than that of the conventional CoMFA (0.422). In contrast, the original q2-GRS CoMFA model showed the lowest internal cross-validated q2 value 0.622 (ONC = 3), lower than that of the conventional CoMFA model (0.639, ONC = 5), it however had the second best external predictive r2 (0.465), whereas the modified q2-GRS model using the first strategy had a q2 value of 0.639 (ONC = 3), which was the same as that of the conventional CoMFA, and its external predictive r2 value (0.447) was only slightly better than that of the conventional model.

Finally, the q2-GRS model modified with the second strategy afforded the best external predictive r2 (0.499) and also gave a satisfactory internal cross-validated q2 at 0.647 (ONC = 3), which was the second best among the five models only after the AOS CoMFA. The stdev*coefficient contour maps generated using this model is further discussed in the next section.

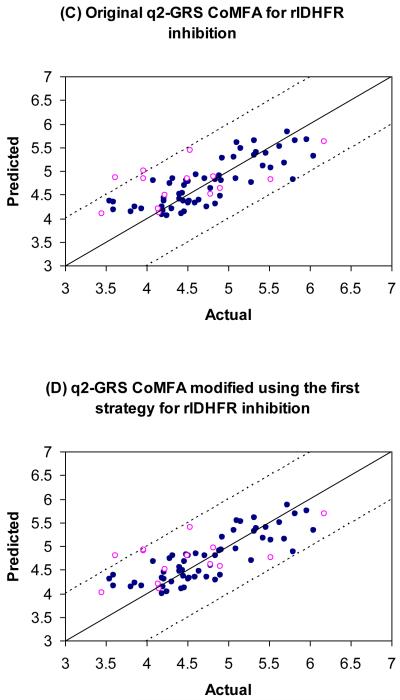

The rlDHFR training set has a total of 57 compounds, which include 1-6, 8, 13-27, 30, 31, 33, 36-41, 43, 44, 52-54, 56-63, 66-71, 74-76, 78-80 (Table 1). The rlDHFR test set contains 14 compounds, which are 7, 9, 12, 28, 32, 35, 42, 45, 49, 51, 55, 64, 65 and 77 (Table 1). A total of five models were generated using the conventional CoMFA, AOS optimized CoMFA, the original q2-GRS optimized CoMFA and the modified q2-GRS optimized CoMFA using the first and the second strategy. The key statistical parameters associated with these models are shown in Table 3. The graph of the actual pIC50 versus the predicted pIC50 versus the predicted pIC50 for the training set and test set by the five CoMFA models are shown in Figure 10(A)-(E) respectively. The predicted pIC50 values of the training set compounds using the five models as well as the residual values are given in Table 11, 13, 15, 17, 19 in the Appendix respectively. The predicted pIC50 values of the test set compounds and the residual values using the five models are given in Table 12, 14, 16, 18, 20 in the Appendix respectively.

Table 3.

Statistical Data for rlDHFR CoMFA (value from original training set/value from the training set after dropping three outliers)

| Conventional | AOS | q2-GRS (original) |

q2-GRS (modified 1) |

q2-GRS (modified 2) |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CV-r2 (q2) | 0.367/0.465 | 0.478/0.536 | 0.375/0.452 | 0.415/0.468 | 0.419/0.431 |

| Opt. no. of comp. |

3/3 | 3/3 | 3/3 | 3/3 | 3/3 |

| Std. error of estimate |

0.348/0.317 | 0.338/0.294 | 0.380/0.334 | 0.366/0.329 | 0.367/0.339 |

| Non-CV- r2 |

0.703/0.715 | 0.720/0.755 | 0.646/0.682 | 0.672/0.692 | 0.671/0.673 |

| F value | 41.822/41.812 | 45.837/51.373 | 32.246/35.810 | 36.150/37.454 | 36.003/34.252 |

| Predictive r2 |

−0.025/0.267 | 0.163/0.281 | 0.171/0.296 | 0.233/0.326 | 0.188/0.320 |

Figure 10.

Predictions for the training (●) and test (○) sets for rlDHFR inhibitory activities. The solid line is the regression line for the training set predictions whereas the dotted lines indicate the ±1.0 log margins.

A q2 ≥ 0.5 is generally considered as an indication that the model is internally predictive. In this case, however, none of the models afforded a q2 greater than 0.5. However, it was evident that both modified q2-GRS routines gave better q2 values than that of the original routine. AOS CoMFA continued to give the highest q2 values among the five models and the first strategy modified q2-GRS model afforded the best predictive r2.

In order to obtain a reasonable CoMFA model for rlDHFR, three outliers 21, 26 and 33, which had an absolute residual value greater than 1.0 during the cross-validation of the conventional CoMFA model, were dropped from the previous rlDHFR training set, while the test set compounds remained the same. A total of five models were again generated using the conventional CoMFA, AOS optimized CoMFA, the original q2-GRS optimized CoMFA and the modified q2-GRS optimized CoMFA using the first and the second strategy. The key statistical parameters associated with these models are shown in Table 3. The graph of the actual pIC50 versus the predicted pIC50 values for the training set and test set by the five CoMFA models are shown in Figure 11(A)-(E) respectively. The predicted pIC50 values of the training set compounds using the five models as well as the residual values are given in Table 21, 23, 25, 27, 29 in the Appendix respectively. The predicted pIC50 values of the test set compounds and the residual values using the five models are given in Table 22, 24, 26, 28, 30 in the Appendix respectively.

Figure 11.

Predictions for the training (●) and test (○) sets for rlDHFR inhibitory activities (Three outliers were dropped from the training set). The solid line is the regression line for the training set predictions whereas the dotted lines indicate the ±1.0 log margins.

In this case, only AOS CoMFA model gave a q2 value greater than 0.5 (0.536, ONC = 3). The modified q2-GRS model using the first strategy gave the second best q2 value (0.468, ONC = 3) and the best predictive r2 (0.326). The stdev*coefficient contour maps of the AOS CoMFA is further discussed in the following section.

7. The Stdev*coefficient Contour Maps

7.1 tgDHFR

The second strategy modified q2-GRS CoMFA model was used to construct the stdev*coefficient contour maps for the tgDHFR (Figure 12).

Figure 12.

(A) Orthogonal view of the steric fields generated with the second strategy modified q2-GRS CoMFA model of tgDHFR: yellow indicates regions where bulky groups decrease activity, whereas green indicates regions where bulky groups increase activity. (B) Orthogonal view of the electrostatic fields generated with the second strategy modified q2-GRS CoMFA model of tgDHFR: red indicates regions where more negatively charged groups increase activity, whereas blue indicates regions where more positively charged groups increase activity.

In the CoMFA steric field (Figure 12A), the green (sterically favorable) and yellow (sterically unfavorable) contours represent 80% and 20% level contributions, respectively.

The 2′-substituent (on the phenyl ring) of 5-substituted pyrrolo[2,3-d]pyrimidines and furo[2,3-d]pyrimidines such as compounds 6, 11, 45, 72 and 74 (Table 1) lies between a yellow region and a green region. A cluster of several small green regions which includes the aforementioned green region is found near the 3′-substituent of 5-substituted pyrrolo[2,3-d]pyrimidines and furo[2,3-d]pyrimidines such as compounds 2, 4, 14, 46, 70 and 76. (Table 1). Yellow regions are found near 4′-substituent and 5′-substituent of the same classes of compounds. The 1-naphthyl moiety, attached to the 5-position of a pyrro[2,3-d]pyrimidine or furo[2,3-d]pyrimidine including compounds 9, 13, 16, 37, 39, 67 and 78 has more contact with green regions than yellow regions. However, the reversed can be said for the 2-naphthyl moiety (compounds 17, 31, 38, 40, 44 and 79). This is evident because compounds 16, 37, 39, 78 that contain the 1-naphthyl moiety all have greater predicted activities than their 2-naphthyl analogs 17, 38, 40 and 79 respectively. A small green region is also found near the bridge atom of all 5-substituted compounds that is directly attached to the 5-position of pyrrolo[2,3-d]pyrimidines or furo[2,3-d]pyrimidines. A green region is also located near the 9-methyl group of compounds 11, 12, 13, 44, 46, 51 and 52 (Table 1). The 6-methyl group of compounds 67-73 (Table 1) lies within a yellow region.

For the 5-methyl-6-phenylsulfanyl-substituted pyrro[2,3-d]pyrimidines including compounds 59-66 (Table 1), both 2′- and 3′-substituents are surrounded by a number of small green regions. The 6-S bridge is also close to a yellow region. There are two green regions also near the 5′ and 6′-substituent position. Some small green regions are found near the 5-methyl group.

For the purine analogs (compounds 18-35, Table 1), green regions are found near the 2′-, 3′- and 5′-substituents and yellow regions near 4′- and 6′-substituents.

Some yellow regions are found near the 7-position of the ring systems indicating that the furo[2,3-d]pyrimidine is more sterically conducive to the activity than pyrrolo[2,3-d]pyrimidines, whose 7-NH is slightly bulkier than the oxygen. The ring of the purine compounds is slightly tilted as compared to the other analogs, positioning it further away from these yellow regions, indicating that the purine ring is probably better than the other two ring systems in terms of steric effect for the inhibitory activity against tgDHFR.

The CoMFA electrostatic contour map for tgDHFR inhibitory activity is depicted in Figure 12B. The red (negative charge favorable) and blue (negative charge unfavorable) contours in the CoMFA electrostatic field represent 80% and 20% level contributions, respectively. The molecules are enveloped by blue regions. Some patches of red regions are also present.

Large blue regions are found on top of the bridge atoms. Blue regions are also found near the amino protons. Red regions are present in the vicinity of the 7-NH and 7-O of the pyrrolo[2,3-d]pyrimidine and furo[2,3-d]pyrimidines, respectively. The 6-methyl group of compounds 67-73 (Table 1) lies near a red region.

For the purine analogs (compounds 18-35, Table 1), two red regions and one blue region are found near the 2′-methoxy oxygen (e.g. compound 21, Table 1) and one red region near the 2′-methoxy methyl. A few blue regions are close to the 3′-methoxy methyl group. Some blue regions are found near the 4′-methoxy methyl of the purine analogs. One blue region is found near 5′-methoxy methyl of the purine analogs.

For the 5-methyl-6-phenylsulfanyl-substituted pyrro[2,3-d]pyrimidines including compounds 59-66 (Table 1), a red region is near the 2′-methoxy oxygen. The 3′-, 4′-, 5′- and 6′-substituents are surrounded by blue regions. A blue region is located near the 5-methyl group. Some red regions are found near the 6-sulfur bridge.

7.2 rlDHFR

The AOS CoMFA model was used to construct the stdev*coefficient contour maps for the rlDHFR (Figure 13). In the CoMFA steric field (Figure 13A), the green (sterically favorable) and yellow (sterically unfavorable) contours represent 80% and 20% level contributions, respectively.

Figure 13.

(A) Orthogonal view of the steric fields generated with AOS CoMFA model of rlDHFR (after dropping three outliers from the training set): yellow indicates regions where bulky groups decrease activity, whereas green indicates regions where bulky groups increase activity. (B) Orthogonal view of the electrostatic fields generated with the AOS CoMFA model of rlDHFR (after dropping three outliers from the training set): red indicates regions where more negatively charged groups increase activity, whereas blue indicates regions where more positively charged groups increase activity.

The 1-naphthyl moiety of 5-substitued pyrrolo[2,3-d]pyrimidines and furo[2,3-d]pyrimidines with a -CH2-NH- bridge is in contact only with the yellow region whereas the 2-naphthyl contacts both the green and the yellow regions. In contrast, the 2-naphthyl moiety of 5-substitued pyrrolo[2,3-d]pyrimidines and furo[2,3-d]pyrimidines with a - CH2-S-bridge is in contact only with the yellow region whereas the 1-naphthyl contacts both the green and the yellow regions. For the 3-carbon bridge at the 5-position of pyrrolo[2,3-d]pyrimidines and furo[2,3-d]pyrimidines, both the 1- and 2-naphthyl contact both the green and yellow regions, but 2-naphthyl seems to have more contact with the green region. A green region is found near the 9-methyl group of compounds 11, 12, 13, 44, 46, 51 and 52 (Table 1).

The 2′-substituents of the purines lie in the green region, part of 3′-substituent lies inside the green region, but it is also in contact with the yellow region. The 4′-OCH3 is found inside the yellow region and the 5′-OCH3 hardly touches that yellow region. The 2-biphenyl contacts some small yellow regions, however, 3-biphenyl is in the previously mentioned green area. The 2-naphthyl of the purine analogs lies in a yellow region.

For the 5-methyl-6-substituted pyrrolo[2,3-d]pyrimidines, the 1-naphthyl is in contact with the green region. 2′-OCH3 and 3′-OCH3 lie within the green region.

The CoMFA electrostatic contour map for rlDHFR inhibitory activity is depicted in Figure 13B. The red (negative charge favorable) and blue (negative charge unfavorable) contours in the CoMFA electrostatic field represent 80% and 20% level contributions, respectively.

For the 5-substituted pyrrolo[2,3-d]pyrimidines and furo[2,3-d]pyrimidines, one relatively large blue region is found near the 2′- and 3′-substituents along with two small red regions located near the 2′-substituent alone. The 4′-substituent overlaps with a red region. A moderately sized blue region is found between the 5′- and 6′-substituents. A small blue region is near the 6′-substituent alone. This small blue region is also close to the sulfur atom of the -CH2-S-bridge in compounds 14-17, 36-38 and 53-58 (Table 1) and the nitrogen atom of the -CH2-NH- or –CH2-N(CH3)-bridge of compounds 1-13, 39, 40 and 42-52 (Table 1). One blue region is found near the bridge carbon atom which is directly attached to the 5-position of the furo[2,3-d]pyrimidines or pyrrolo[2,3-d]pyrimidines. Three large red regions are located near the 7-position –NH- or –O- for the pyrrolo[2,3-d]pyrimidine and furo[2,3-d]pyrimidine respectively.

For the purine analogs (compounds 18-35, Table 1), one relatively large blue region is found near the 2′- and 3′-substituents with two small red regions overlapping with the 2-substituents and a red region near the 3′-substituent. One small blue region is found near the oxygen of the 5′-methoxy group.

In the case of 5-methyl-6-substituted pyrro[2,3-d]pyrimidines including compounds 59-66 (Table 1), the 2′- and 3′-substituent each overlaps with a red region and a small blue region is located near the 5′-region. The sulfur bridge is sandwiched between a large red region and a relatively small blue region.

Application of the Model

As an intial application we elected to use the steric contour maps of the tgDHFR and rlDHFR CoMFA (Figure 14 (A) and (B) respectively), which indicated that selective tgDHFR inhibitory activity over rlDHFR activity may be possible for the 2,4-diamino-5-methyl-6-phenylsulfanyl-substituted pyrrolo[2,3-d]pyrimidines, if both sides of the phenyl ring are substituted (i.e. any combination of 2′, 3′ and 5′, 6′). Indeed, among the eight previously reported 5-methyl-6-phenylsulfanyl-substituted pyrrolo[2,3-d]pyrimidines 59-66,11 the only compound that fits this criteria was 66 (2′,5′-diOMePhenyl), which was the most potent tgDHFR inhibitor among the series (59-66) with an IC50 value of 0.17 μM similar to 59 (1-naphthyl, IC50=0.16 μM) and was also the most selective tgDHFR inhibitor as compared to rlDHFR with a selectivity ratio of 45.9 in contrast to 28.6 for 59.

Figure 14.

(A) Stereo view of the steric fields of the tgDHFR CoMFA model with the structure of compound 62, there are green (steric favorable) regions near both sides of the phenyl moiety (B) Stereo view of the steric fields of the rlDHFR CoMFA model with the structure of compound 60, only one side of the phenyl moiety is close to a green (steric favorable) region.

Thus it was of interest to synthesize additional analogs with disubstitution on either side of the phenyl ring as suggested by the steric contour maps. We synthesized and evaluated compounds 90-94 (Scheme 1). Four of these compounds (91-94) had substituents on both sides of the phenyl ring. The 2-naphthyl compound 90 was designed on the basis of the excellent activity and selectivity of the closely related 1-naphtyl compound 59 described above.

Scheme 1.

These compounds were obtained via a previously reported an oxidative thiolation by Gangjee et al.11 of the known compound 8456 (Scheme 1) with appropriately substituted thiols 85-89 in the presence of iodine as shown in Scheme 1.11

The thiol 89 was the only one that was not commercially available and was synthesized from the corresponding aniline.57 Compounds 90-94 were evaluated as inhibitors of tgDHFR and rlDHFR, and the results (IC50) are reported in Table 4.

Table 4.

Inhibition Concentrations (IC50, in μM) Dihydrofolate Reductases from T. gondii and Rat Liver and Selectivity Ratiosa

| Cmpd. | tgDHFR | rlDHFR | rl/tg |

|---|---|---|---|

| 90 | 1.6 | 8.1 | 5.1 |

| 91 | 0.00511 | 0.388 | 75.9 |

| 92 | 0.572 | 7.6 | 13.3 |

| 93 | 0.212 | 3 | 14.2 |

| 94 | 0.686 | 24.6 (12%) | ND |

These assays were carried out at 37 °C under conditions of substrate (90 μM dihydrofolic acid) and cofactor (119 μM NADPH) in the presence of 150 mM KCl.

Numbers in parentheses are percent inhibition at the given concentration.

All four compounds designed on the basis of the CoMFA models (91-94) were sub-micromolar inhibitors of tgDHFR and had selectivity ratios of more than 10-fold against tgDHFR as compared to the mammalian standard rlDHFR. Compound 91 was remarkable in terms of both its IC50 value and selectivity ratio (5.11 nM and 75.9-fold respectively) and is the first nanomolar inhibitor of tgDHFR with a 6-5 fused ring system. In contrast, the analog 90 was a micromolar inhibitor (IC50 = 1.6 μM) of tgDHFR with a selectivity ratio of only 5-fold.

The promising result for compound 91 against isolated tgDHFR prompted us to further investigate this compound in cell culture and in vivo. However, 91 had poor solubility properties. To improve the solubility characteristics, 91 was converted to its more soluble hydrochloride salt 95 (Scheme 1) by carefully adding 1N hydrochloric acid to a suspension of 91 in methanol under sonication until all the compound went into solution. Filtration and evaporation of the filtrate to dryness afforded the HCl salt as a white powder.

Compounds 91 and 95 were initially evaluated in vitro as inhibitors of the growth of T. gondii cells in culture along with the standard compound pyrimethamine and the IC50 values are tabulated in Table 5. These results suggest that the free base 91 and the HCl salt 95 do not differ in the inhibiton of T. gondii cells in culture, and both are potent inhibitors of T. gondii cell growth in vitro.

Table 5.

IC50 of cell growth of 91, 95 and Pyrimethamine in culture from T. gondiia

| Cmpd. | IC50 (μM) |

|---|---|

| 91 | 1.92 |

| 95 | 2.15 |

| Pyrimethamine | 0.7 |

T. gondii cell culture inhibition was assessed by measuring the incorporation of [3H]uracil by T. gondii cells.

Cytotoxicity of compound 91 was then evaluated against human embryonic lung fibroblast. Compound 91 inhibited these fibroblast cells only 9% at 260 μM indicating that compound 91 is relatively nontoxic against human fibroblast cells compared to T. gondii cells in culture.

On the basis of the results in isolated tgDHFR and the cell culture inhibitory data compound 91 was evaluated in a T. gondii infection mouse model. The HCl salt 95 was also evaluated in a side-by-side evaluation with 91 and the data are presented in Table 6. Compound 91 has been studied in two acute infection mouse models of RH strain of T. gondii. The intraperitoneal route was chosen, based on past experience showing activity by this route with other antifolates and on the knowledge that 91 lacked adequate solubility to administer appropriate doses intravenously. The dose of 50 mg/kg/day reflects the amount of compound injected but upon harvest of the mice in the first study, we observed drug deposits in the peritoneal cavity for many of the animals; therefore, the actual available dose was below 50 mg/kg/day for many mice. In the first study, folic acid was given to one treated group to offset any potential toxicity due to antifolate activity in mammalian cells; in fact, we saw no gross evidence of toxicity and folic acid had little effect on the activity of the compound. Hence, folic acid was not used in the second study.

Table 6.

Statistical analysis of two studies in T. gondii mouse model

| Group | Route | Dose (mg/kg/day) |

Median | Mean | SEM | P value* |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Control | N/A | N/A | 14.0 | 17.9 | 3.3 | N/A |

| 91 | i.p. | 50 | 7.0 | 12.5 | 2.5 | 0.055 |

| 91 + FA | i.p. | 50 | 6.0 | 9.8 | 2.0 | 0.019 |

| Control | N/A | N/A | 13.5 | 12.6 | 2.0 | N/A |

| 91 | i.p. | 50 | 5.0 | 8.9 | 1.5 | 0.035 |

| 95 | i.p. | 50 | 1.0 | 2.4 | 0.4 | <0.0001 |

FA = folic acid, which was administered in drinking water at 10 microgram/ml

The data analyzed are counts of T. gondii per 1000x field in total harvested peritoneal, the 10 microliters sampled onto a 1cm2 area of a microscope slide for analysis.

Relative to the control within each experiment. The nono-parametric Mann-Whitney test was used to compare two groups and the non-parametric Kruskal-Wallis ANOVA was used to compare several groups within one experiment.

The rationale for the second study was to determine if the HCl salt 95 was more effective than the parent compound. Control levels of infection and the results with 91 alone were comparable to the first study, in that 91 reduced the median counts per 1000x field by more than two-fold; the drop was statistically significant (P < 0.035). The group treated with 95 showed even more effective lowering of the counts of surviving organisms; the difference in counts for this group was statistically different from both the control and 91 alone, with P values of < 0.0001. Furthermore, there was 100% survival of the mice for 91 and 95 compared to 25% for control on the 5th day. The mice were harvested on the 6th day. Clindamycin was used as the positive control and also provided a 100% survival of mice.

In summary, CoMFA analysis models that correlate the 3D chemical structures of 80 compounds with 6-5 fused ring system synthesized in our laboratory and their inhibitory potencies for tgDHFR and rlDHFR were developed. In addition to conventional CoMFA analysis, two routines available in the literature aimed at the optimization of CoMFA: all-orientation search (AOS) and cross-validated r2-guided region selection (q2-GRS) were used to further optimize the models. During this process, a potential problem associated with q2-GRS routine was identified and corrected by modifications using two strategies. Thus for the inhibitory activity against each enzyme (tgDHFR and rlDHFR), five CoMFA models were developed using the conventional CoMFA, AOS optimized CoMFA, the original q2-GRS optimized CoMFA and the modified q2-GRS optimized CoMFA using the first and the second strategy. This work demonstrated that the modified q2-GRS routines are superior to the original routine.

On the basis of the steric contour maps, four new compounds (91-94) were designed, synthesized and biologically evaluated. All of the compounds had IC50 values that were at least sub-micromolar against tgDHFR inhibitors with 10-fold or better selectivity ratios as compared to rlDHFR. In particular, compound 91 was identified as the first nanomolar 6-5 fused ring system inhibitor of tgDHFR.

Compound 91 and its HCl salt 95 were potent inhibitors of T. gondii cell growth in culture with similar activities. On the basis of the cell culture inhibitory data, both compounds were evaluated in a T. gondii infection mouse model. The in vivo results confirmed that compound 91 has demonstrable activity against T. gondii in an acute in vivo model, and the HCl salt 95 is significantly more active than the parent compound 91, a result likely due to increased solubility and better uptake from the peritoneal cavity.

Experimental Section

All evaporations were carried out in vacuo with a rotary evaporator. Analytical samples were dried in vacuo (0.2 mmHg) in an Abderhalden drying apparatus over P2O5 at 70 °C. Thin-layer chromatography (TLC) was performed on silica gel plates with fluorescent indicator. Spots were visualized by UV light (254 and 365 nm). All analytical samples were homogeneous on TLC in at least two different solvent systems. Purification by column and flash chromatography was carried out using Merck silica gel 60 (200-400 mesh). The amount (weight) of silica gel for column chromatography was in the range of 50-100 times the amount (weight) of the crude compounds being separated. Columns were dry-packed unless specified otherwise. Solvent systems are reported as volume percent of mixture. Melting points were determined on a Mel-Temp II melting point apparatus and are uncorrected. Proton nuclear magnetic resonance (1H NMR) spectra were recorded on a Bruker WH-300 (300 MHz) spectrometer. The chemical shift (δ) values are reported as parts per million (ppm) relative to tetramethylsilane as internal standard; s = singlet, d = doublet, t = triplet, q = quartet, m = multiplet, br = broad singlet. Elemental analyses were performed by Atlantic Microlab, Inc., Norcross, GA. Elemental compositions were within ±0.4% of the calculated values. Fractional moles of water or organic solvents frequently found in some analytical samples of antifolates could not be removed despite 24 h of drying in vacuo and were confirmed, where possible, by their presence in the 1H NMR spectrum. All solvents and chemicals were purchased from Aldrich Chemical Co. and Fisher Scientific and were used as received.

2,4-Diamino-5-methyl-6-(2-naphthylthio)pyrrolo[2,3-d]pyrimidine (90)

To a solution of 84 (0.10g, 0.61 mmol) in a mixture of ethanol/water (2:1, 50 mL) was added 2-naphthylthiol 85 (0.20 g, 1.22 mmol) and the reaction mixture was heated to reflux for 4 hrs. The mixture was cooled to room temperature and concentrated under reduced pressure. After evaporation of the solvent under reduced pressure, the residue was washed with ethyl acetate followed by the addition of 200 mL of methanol and the pH adjusted to 10 with concentrated NH4OH. The suspension was left at room temperature for 30 min and filtered. The residue was washed well with methanol and air dried to give compound 90 (0.077g, 39%): mp 276.2-282.2 °C (decomp.); TLC Rf 0.50 (CHCl3/MeOH, 5:1, silica gel); 1H NMR (Me2SO-d6) δ2.35 (s, 3H, 5-CH3), 5.68 (s, 2H, 2-NH2), 6.33 (s, 2H, 4-NH2), 7.15-7.84 (m, 7H, C10H7), 11.06(s, 1H, 7-H). HRMS (EI) m/e Calcd for C17H15N5S 321.104817, Found (M+) 321.105293.

2,4-Diamino-5-methyl-6-(2′,6′-dimethylphenylthio)pyrrolo[2,3-d]pyrimidine (91)

Compound 91 (0.94 g, 51%) was obtained from 84 (1.0 g, 6.1 mmol), 2,6-dimethyl-benzenethiol 86 (1.7 g, 12.3 mmol), and iodine (3.1 g, 12.3 mmol): mp 286.8-288.4 °C (decomp.); TLC Rf 0.70 (CHCl3/MeOH, 5:1, silica gel); 1H NMR (Me2SO-d6) δ2.20 (s, 3H, 5-CH3), 2.33 (s, 6H, 2′,6′-diMe), 5.44 (s, 2H, 2-NH2), 6.07 (s, 2H, 4-NH2) 7.07 (s, 3H, aromatic), 10.62 (s, 1H, 7-H). Anal. (C15H17N5S · 0.20 H2O) C, H, N, S.

2,4-Diamino-5-methyl-6-(3′,5′-dimethylphenylthio)pyrrolo[2,3-d]pyrimidine (92)

Compound 92 (0.065 g, 7.0%) was obtained from 84 (0.50 g, 3.06 mmol), 3′,5′-dimethyl-benzenethiol 87 (0.85 g, 6.13 mmol) and iodine (1.56 g, 6.13 mmol). mp 285.5-288.9 °C (decomp.); TLC Rf 0.67 (CHCl3/MeOH, 5:1, silica gel); 1H NMR (Me2SO-d6) δ2,17 (s, 6H, 3,5-(CH3)2), 2.32 (s, 3H, 5-CH3), 5.63 (s, 2H, 2-NH2), 6.29 (s, 2H, 4-NH2), 6.62 (s, 2H, 2′,6′-H2), 6.75 (s, 2H, 4′-H), 10.93(s, 1H, 7-H). Anal. (C15H17N5S) C, H, N, S.

2,4-Diamino-5-methyl-6-(2′,4′,5′-trichlorophenylthio)pyrrolo[2,3-d]pyrimidine (93)

Compound 93 (0.036 g, 8.4%) was obtained from 84 (0.20 g, 1.23 mmol), 2′,4′,5′-trichloro-benzenethiol 88 (0.52 g, 2.45 mmol) and iodine (0.62 g, 2.45 mmol). mp > 300 °C (decomp.); TLC Rf 0.65 (CHCl3/MeOH, 5:1, silica gel); 1H NMR (Me2SO-d6) δ2.30 (s, 3H, 5-CH3), 5.72 (s, 2H, 2-NH2), 6.36 (s, 2H, 4-NH2), 6.53 (d, 1H, aromatic), 7.90 (s, 1H, aromatic), 11.10 (s, 1H, 7-H). Anal. (C13H10Cl3N5S) C, H, N, Cl, S.

2,4-Diamino-5-methyl-6-(3′,4′,5′-trimethoxyphenylthio)pyrrolo[2,3-d]pyrimidine (94)

Compound 94 (0.023 g, 5.4%) was obtained from 84 (0.20 g, 1.23 mmol), 3′,4′,5′-trimethoxy-benzenethiol 89 (0.49 g, 2.45 mmol) and iodine (0.62 g, 2.45 mmol). 230.5-233.1 °C (decomp.); TLC Rf 0.55 (CHCl3/MeOH, 5:1, silica gel); 1H NMR (Me2SO-d6) δ2.34 (s, 3H, 5-CH3), 3.59 (s, 3H, 4′-OCH3),3,66(s, 6H, 3′,5′-(OCH3)2), 5.60 (s, 2H, 2-NH2), 6.25 (s, 2H, 4-NH2), 6.38 (s, 2H, 2′,6′-H2), 7.04 (d, 2H, 2′, 6′-2H), 10.94 (s, 1H, 7-H). HRMS (EI) m/e Calcd for C16H19N5O3S 361.120862, Found (M+) 361.120657.

2,4-Diamino-5-methyl-6-(2′,6′-dimethylphenylthio)pyrrolo[2,3-d]pyrimidine hydrochloride salt (95)

0.8 g of compound 91 suspended in 100 mL of methanol was submerged in water inside of a sonicator. 1N hydrochloric acid was added drop-wise to the suspension until a clear solution was obtained, which was filtered and the filtrate evaporated to dryness under reduced pressure to afford the salt as a white powder: 1H NMR (Me2SO-d6) δ2.26 (s, 3H, 5-CH3), 2.34 (s, 6H, 2′,6′-diMe), 7.12 (s, 3H, aromatic), 7.28 (s, 2H, 2-NH2), 8.02 (s, 2H, 4-NH2), 11.76 (s, 1H, 7-H), 12.01 (s, 1H, 1-H). Anal. (C15H17N5S · 1.0 HCl · 0.50 H2O) C, H, N, S. Cl.

Dihydrofolate Reductase (DHFR) Assay

The spectrophotometric assay for DHFR was modified to optimize for temperature, substrate concentration, and cofactor concentration for each enzyme form assayed. The standard assay contained sodium phosphate buffer pH 7.4 (40.7 mM), 2-mercaptoethanol (8.9 mM), NADPH (0.117 mM), 1 to 3.7 IU of enzyme activity (1 IU = 0.005 OD units/min), and dihydrofolic acid (0.092 mM). KCl(150 mM) was included in the assay for T. gondii and rat liver DHFR, because it stimulated the enzymes 1.4- and 2.63-fold, respectively. The first three reagents were combined in a disposable cuvette and brought to 37 °C. Drug dilutions were added at this stage. The enzyme was added 30 s before the reaction was initiated with dihydrofolic acid. The reaction was followed for 5 min with continuous recording. Activity under these conditions of assay was linear with enzyme concentration over at least a 4-fold range. Background activity measured with no added dihydrofolic acid was zero with the enzyme obtained from cultured T. gondii and near zero for other forms of DHFR. All DHFR inhibitors were tested against rat liver DHFR as well as against pathogen DHFR to allow assessment of selectivity.

Determination of IC50 Values

DHFR was assayed without inhibitor and with a series of concentrations of inhibitors to produce 10 to 90% inhibition. At least three concentrations were required for calculation. Semilogarithmic plots of the data yielded normal sigmoidal curves for most inhibitors. The 50% inhibitory concentration (IC50) was calculated from these curves using Prism 3.0.

Source of T. gondii

A clinical isolate of T. gondii was obtained from the Department of Pathology, Indiana University School of Medicine, after a single passage in a female BALB/c mouse (Harlan Industries, Indianapolis). The organisms were passaged in mice twice more, increasing the number of mice at each passage. After the final passage, the peritoneal exudate was pooled and centrifuged, and the organisms were resuspended in RPMI medium containing 10% fetal calf serum. Frozen stocks were prepared by adding 5% DMSO to the medium and freezing slowly over 8 to 15 h. Stocks were stored in liquid nitrogen.

Culture of T. gondii for Enzyme Production

By using a chinese hamster ovary cell line that lacks DHFR (American Type Culture Collection, 3952 CL, CHO/dhfr-), T. gondii cells were grown and maintained in Iscove’s Modified Eagle’s Medium with 10% fetal calf serum, 1% penicillin/streptomycin, 100 mM hypoxanthine, and 10 mM thymidine. To each 75 cm2 tissue culture flask containing the monolayer of cells was added an inoculum of approximately 107 organisms. Organisms (4 × 108) were harvested from each flask, within 6 to 8 days.

Preparation of Enzymes from T. gondii

T. gondii organisms are minimally contaminated with mammalian host cells when harvested from tissue culture, without detectable mammalian DHFR activity.57 When prepared as noted above, DHFR from cultured T. gondii has been shown to yield IC50 values similar to those reported in the literature.57 The kinetics for cofactor and substrate are also similar to reported values in the literature.57

Uracil Incorporation by Cultured T. gondii

For T. gondii grown in culture, uracil is incorporated into nucleic acid, but mammalian cells do not. Thus incorporation of uracil is used as an index of growth of T. gondii on host cells.57 T. gondii is grown on HEL (human embryonic lung) cells with Minimum Essential Medium (MEM) supplemented with glutamine (2mM), penicillin/streptomycin (100 units/mL and 100 μg/mL, respectively), and fetal bovine serum (10%). The experiment was carried out as described previously.57

In Vivo Testing of Drugs against T. gondii

Female BALB/c mice (18-20 g) were injected intraperitoneally with 5 × 103 trophozoites of T. gondii from culture. Drug treatment started immediately if the drugs were given in drinking water of food; if the drugs were injected, treatment started 4 h after inoculation. Survival or counts of T. gondii present in peritoneal exudates or liver were monitored as an index of drug efficacy.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgement

This work was supported in part by the National Institutes of Health, National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases AI047759 (A.G.) and NCI CA98850 (A.G.).

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Presented in part at the 231st ACS National Meeting, Atlanta, GA, March 26-30, 2006; MEDI-349.

References

- 1.Klepser ME, Klepser TB. Drugs. 1997;53:40–73. doi: 10.2165/00003495-199753010-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Gangjee A, Devraj R, McGuire JJ, Kisliuk RL, Queener SF, Barrows LR. J. Med. Chem. 1994;34:1169–1176. doi: 10.1021/jm00034a015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gangjee A, Mavandadi F, Queener SF, McGuire JJ. J. Med. Chem. 1995;38:2158–2165. doi: 10.1021/jm00012a016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gangjee A, Mavandadi F, Kisliuk RL, McGuire JJ, Queener SF. J. Med. Chem. 1996;39:4563–4568. doi: 10.1021/jm960097t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gangjee A, Mavandadi F, Queener SF. J. Med. Chem. 1997;40:1173–1177. doi: 10.1021/jm960717q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gangjee A, Vasudevan A, Queener SF. J. Med. Chem. 1997;40:3032–3039. doi: 10.1021/jm970271t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gangjee A, Guo X, Queener SF, Cody V, Galitsky N, Luft JR, Pangborn W. J. Med. Chem. 1998;41:1263–1271. doi: 10.1021/jm970537w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gangjee A, Dubash NP, Queener SF. J. Heterocyclic. Chem. 2000;37:935–942. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gangjee A, Vidwans A, Elzein E, McGuire JJ, Queener SF, Kisliuk RL. J. Med. Chem. 2001;44:1993–2003. doi: 10.1021/jm0100382. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gangjee A, Yu J, Kisliuk RL. J. Heterocyclic. Chem. 2002;39:833–840. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gangjee A, Lin X, Queener SF. J. Med. Chem. 2004;47:3689–3692. doi: 10.1021/jm0306327. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gangjee A, Zeng Y, McGuire JJ, Mehraein F, Kisliuk RL. J. Med. Chem. 2004;47:6893–6901. doi: 10.1021/jm040123k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gangjee A, Jain HD, Queener SF. J. Heterocyclic. Chem. 2005;42:589–594. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gangjee A, Ye Z, Queener SF. J. Heterocyclic. Chem. 2005;42:1127–1133. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gangjee A, Zeng Y, Ihnat M, Warnke LA, Green DW, Kisliuk RL, Lin F-T. Bioorg. Med. Chem. 2005;13:5475–5491. doi: 10.1016/j.bmc.2005.04.087. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ivanciuc O, Ivanciuc T, Cabrol-Bass D. Theochem. J. Mol. Struct. 2002;582:39–51. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Burbidge R, Trotter M, Buxton B, Holden S. Comput. Chem. 2001;26:5–14. doi: 10.1016/s0097-8485(01)00094-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Garg S, Achenie LEK. Biotechnol. Prog. 2001;17:412–418. doi: 10.1021/bp010034q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Zheng W, Tropsha A. J. Chem. Inf. Comput. Sci. 2000;40:185–194. doi: 10.1021/ci980033m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Selassie CD, Gan W-X, Kallander LS, Klein TE. J. Med. Chem. 1998;41:4261–4272. doi: 10.1021/jm970776j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Burden FR, Rosewarne BS, Winkler DA. Chemom. Intell. Lab. Syst. 1997;38:127–137. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ivanciuc O. Rev. Roum. Chim. 1996;41:645–652. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Marlowe CK, Selassie CK, Santi DV. J. Med. Chem. 1995;38:967–972. doi: 10.1021/jm00006a016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hirst JD, King RD, Sternberg MJE. J. Comput.-Aided Mol. Des. 1994;8:421–432. doi: 10.1007/BF00125376. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hirst JD, King RD, Sternberg MJE. J. Comput.-Aided Mol. Des. 1994;8:405–420. doi: 10.1007/BF00125375. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Stanton DT, Murray WJ, Jurs PC. Quant. Struct.-Act. Relat. 1993;12:239–245. [Google Scholar]

- 27.So S-S, Richards WG. J. Med. Chem. 1992;35:3201–3207. doi: 10.1021/jm00095a016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Selassie CD, Li R-L, Poe M, Hansch C. J. Med. Chem. 1991;34:46–54. doi: 10.1021/jm00105a008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Debnath AK, Lopez de Compadre RL, Debnath G, Shusterman AJ, Hansch C. J. Med. Chem. 1991;34:786–797. doi: 10.1021/jm00106a046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Andrea TA, Kalayeh H. J. Med. Chem. 1991;34:2824–2836. doi: 10.1021/jm00113a022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Selassie CD, Fang Z-X, Li R-L, Hansch C, Debnath G, Klein TE, Langridge R, Kaufman BT. J. Med. Chem. 1989;32:1895–1905. doi: 10.1021/jm00128a035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Li R-L, Poe M. J. Med. Chem. 1988;31:366–370. doi: 10.1021/jm00397a017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Booth RG, Selassie CD, Hansch C, Santi DV. J. Med. Chem. 1987;30:1218–1224. doi: 10.1021/jm00390a017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Selassie CD, Fang Z-X, Li R-L, Hansch C, Klein TE, Langridge R, Kaufman BT. J. Med. Chem. 1986;29:621–626. doi: 10.1021/jm00155a006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Ghose AK, Crippen GM. J. Med. Chem. 1985;28:333–346. doi: 10.1021/jm00381a013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Hansch C, Hathaway BA, Guo Z-R, Selassie CD, Dietrich SW, Blaney JM, Langridge R, Volz KW, Kaufman BT. J. Med. Chem. 1984;27:129–143. doi: 10.1021/jm00368a006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Hathaway BA, Guo Z-R, H C, Delcamp TJ, Susten SS, Freisheim JH. J. Med. Chem. 1984;27:144–149. doi: 10.1021/jm00368a007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Hopfinger AJ. J. Med. Chem. 1983;26:990–996. doi: 10.1021/jm00361a011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Khwaja TA, Pentecost S, Selassie CD, Guo Z-R, Hansch C. J. Med. Chem. 1982;25:153–156. doi: 10.1021/jm00344a012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Hansch C, Li R-L, Blaney JM, Langridge R. J. Med. Chem. 1982;25:777–784. doi: 10.1021/jm00349a003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Ghose AK, Crippen GM. J. Med. Chem. 1982;25:892–899. doi: 10.1021/jm00350a003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Li R-L, Dietrich SW, Hansch C. J. Med. Chem. 1981;24:538–544. doi: 10.1021/jm00137a012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Coats EA, Genther CS, Dietrich SW, Guo Z-R, Hansch C. J. Med. Chem. 1981;24:1422–1429. doi: 10.1021/jm00144a010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Crippen GM. J. Med. Chem. 1980;23:599–606. doi: 10.1021/jm00180a004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Dietrich SW, Blaney JM, Reynolds MA, Jow PYC, Hansch C. J. Med. Chem. 1980;23:1205–1212. doi: 10.1021/jm00185a011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Blaney JM, Hansch C, Silipo C, Vittoria A. Chem. Rev. 1984;84:333–407. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Mattioni BE, C JP. J. Mol. Graphics Modell. 2003;21:391–419. doi: 10.1016/s1093-3263(02)00187-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Sutherland JJ, Weaverb DF. J. Comput.-Aided Mol. Des. 2004;18:309–331. doi: 10.1023/b:jcam.0000047814.85293.da. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Gangjee A, Lin X. J. Med. Chem. 2005;48:1448–1469. doi: 10.1021/jm040153n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Wang R, Gao Y, L L, Lai L. J. Mol. Model. 1998;4:276–283. [Google Scholar]

- 51.Cho SJ, Tropsha A. J. Med. Chem. 1995;38:1060–1066. doi: 10.1021/jm00007a003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Cody V, Galitsky N, Luft JR, Pangborn W, Gangjee A, Devraj R, Queener SF, Blakley RL. Acta Crystallogr., Sect. D. 1997;53:638. doi: 10.1107/S090744499700509X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Molecular Operating Environment (MOE 2004.03) C. C. G., Inc, 1255 University St., Suite 1600; Montreal, Quebec, Canada, H3B 3X3: [Google Scholar]

- 54.SYBYL Version 7.0. Tripos Associates; St. Louis, M: [Google Scholar]

- 55.Godden JW, Xue L, Bajorath J. J. Chem. Inf. Comput. Sci. 2000;40:163–166. doi: 10.1021/ci990316u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Taylor EC, Patel HH, Jun J-G. J. Org. Chem. 1995;60:6684–6687. [Google Scholar]

- 57.Offer J, Boddy CNC, Dawson PE. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2002;124:4642–4646. doi: 10.1021/ja016731w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Chio LC, Queener SF. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 1993;37:1914–1923. doi: 10.1128/aac.37.9.1914. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.