Abstract

This study examined the relationship between race, laboratory-based coping strategies and anticipatory anxiety and pain intensity for cold, thermal (heat) and pressure experimental pain tasks. Participants were 123 healthy children and adolescents, including 33 African Americans (51% female; mean age =13.9 years) and 90 Caucasians (50% female; mean age = 12.6 years). Coping in response to the cold task was assessed with the Lab Coping Style interview; based on their interview responses, participants were categorized as ‘attenders’ (i.e., those who focused on the task) vs. ‘distractors’ (i.e., those who distracted themselves during the task). Analysis of covariance (ANCOVA) revealed significant interactions between race (African-American vs. Caucasian) and lab-based coping style after controlling for sex, age and socioeconomic status. African-American children classified as attenders reported less anticipatory anxiety for the cold task and lower pain intensity for the cold, heat and pressure tasks compared to those categorized as distractors. For these pain outcomes, Caucasian children classified as distractors reported less anticipatory anxiety and lower pain intensity relative to those categorized as attenders. The findings point to the moderating effect of coping in the relationship between race and experimental pain sensitivity.

Keywords: pain, coping, race, children

Introduction

Racial and ethnic differences in the experience of pain have long been noted. Numerous investigators have reported racial/ethnic disparities in adult studies of clinical pain (1–4) and laboratory pain (5–7). For the most part, these findings show that, compared to Caucasians, African Americans report higher levels of pain, including pain unpleasantness, emotional reactions to pain, higher pain intensity and lower pain threshold. In addition, it appears that African Americans evidence distinct methods of pain coping, which together with increased levels of pain-related anxiety and depression, may contribute towards marked pain sensitivity (1). However, limited research has examined the influence of race/ethnicity on children’s pain sensitivity.

The present study attempts to address the current gap in our knowledge of racial differences in pain and coping among children—a topic of clear import, given that an individual’s ideas about race/ethnicity, pain and coping are all formed early in life (8, 9). Not to preclude the possible role of biology in racial/ethnic differences in pain (7), but racial/ethnic identity reflects to a large degree sociocultural and family processes, making the relationships among race/ethnicity, pain and coping especially noteworthy early in the developmental trajectory.

Two strands of adult research show that coping is intricately linked to an individual’s experience of pain. The first documents an association between general coping style and pain, such that the tendency to use passive or external coping strategies is associated with higher pain sensitivity (10, 11), and moreover, that African Americans tend to report different coping preferences to Caucasians (1,12,13). The second strand has examined coping in response to a particular pain episode, revealing that for some populations and pain conditions, attending to pain is often less effective than distracting oneself from pain (14). Similar to the adult literature, children who use distraction to cope with acute laboratory pain are more likely to report increased pain tolerance (15), particularly when instruction to use distraction is concordant with the child’s natural coping methods (16). As yet it is unclear whether there are racial/ethnic differences in the tendency to divert or avert attention in the laboratory pain setting, and the use of coping strategies is untested in children of different racial/ethnic backgrounds.

We conducted the present study to investigate African American and Caucasian children’s laboratory-specific coping and pain in response to experimental pain tasks. The focus on laboratory specific coping is consistent with the idea that coping is likely to be situation and pain- specific (17). Racial/ethnic-coping relationships in the context of experimental pain are likely to vary depending on whether general coping versus situation-specific coping is assessed (5). Given that experimental pain situations are relatively unique in the child’s pain experience, it was deemed important to assess their lab-specific pain coping. To our knowledge, this study is the first to examine racial/ethnic differences in coping and laboratory pain in a sample of children. Three laboratory pain modalities were used: pressure, thermal heat, and cold pain.

Given the paucity of previous research, no directional hypotheses were advanced. However, based on the adult literature, it was anticipated that distinct patterns for laboratory-based coping and pain responses would emerge for African American and Caucasian children.

Methods

The current sample was drawn from a larger sample of 240 children who participated in a study on the effects of gender and puberty on laboratory pain responses described previously (18). The initial sample included five different racial/ethnic categories, including ‘Hispanic’ (n = 57), ‘Asian/Pacific Islander’ (n = 24) and ‘Other (n = 30).’ Due to the focus on African American and Caucasian participants in the previous adult literature, only African American and Caucasian participants were included in this analysis. Thus, the present study included 98 Caucasians and 34 African Americans. Nine participants who reported no coping strategy on the coping style interview (described below) were removed. One-way ANOVAs and chi square statistics revealed no significant differences in age, sex or race between the 9 participants who reported no coping strategy and the participants included in the current study. The final sample consisted of 123 healthy children (50% male): 90 Caucasians (73%) and 33 African Americans (27%). Mean age was 12.9 years (SD, 2.97 years) and mean grade in school was 7th grade. Participant demographics for each racial group are presented in Table 1.

Table 1.

Demographic and coping information by race

| African Americans | Caucasians | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age | 13.89 (3.25) | 12.60 (2.80)* | ||

| Sex | Males: 16 (49%) | Males: 45 (50%) | ||

| Females: 17 (51%) n | Females: 45 (50%) n | |||

| Parent Education Level | Partial High School | 1 | Partial High School | 0 |

| High School Graduate | 12 | High School Graduate | 8 | |

| Partial college | 9 | Partial college | 12 | |

| Bachelor’s degree | 5 | Bachelor’s degree | 38 | |

| Graduate degree | 1 | Graduate degree | 31* | |

| Parent Occupation | 51 (13.01) | 74 (13.17)* | ||

| Lab Coping Style | Attender: 24 (73%) | Attender: 54 (57%) | ||

| Distractor: 9 (27%) | Distractor: 36 (33%) | |||

Unless otherwise specified African American n = 33, Caucasian n = 90.

p < .05.

Participants were recruited from a major urban area through posted advertisements, mass mailing and classroom presentations. Recruitment was targeted at various racial/ethnic groups across sites of varied socioeconomic status. Telephone screening reduced an initial 489 interested individuals to 244 eligible participants, with four failing to complete the study due to time and constraints (n = 3) and discomfort with being attached to the electrodes (n = 1). The University of California, Los Angeles (UCLA) Institutional Review board (IRB), as well as the IRBs for recruitment sites approved all recruitment and study procedures. The pain tasks selected have been previously performed with children without adverse effects. IRB approved consent and assent forms were completed by parents and children. Participants received a $30 video store voucher and a t-shirt for their participation.

Procedure

Each participant visited the testing site once. Upon visiting the laboratory, participants completed demographic and psychosocial questionnaires with an experimenter in a room adjacent to the laboratory. Two experimenters conducted the sessions; experimenters included five females and two males. A male experimenter conducted the study with 4 participants, with female experimenters conducting the sessions on the other occasions. There were no differences between racial groups in the presence of male vs. female experimenters (X2 = .01, p>.05).

After completing the questionnaires, participants were escorted to the laboratory where they completed three pain tasks, namely cold pressor, thermal heat and cutaneous pressure tasks (described below). Prior to the administration of the pain tasks, participants were instructed on the use of a vertical sliding visual analog scale (VAS) for rating pain intensity and anticipatory anxiety (described below). More detailed descriptions of the procedure, including randomization and ordering of tasks have been reported previously(18, 19). Immediately, after the cold pressor task (CPT), the pain coping strategy interview, which assessed what subjects did or thought about to keep their hand immersed longer and which strategy was employed the most was administered to determine the primary laboratory-based coping style.

Laboratory Pain Tasks

Cold Pressor Task

Participants underwent a single trial of 10 °C water using a commercial ice chest measuring 38 cm wide, 71 cm long and 35 cm deep. A plastic mesh screen separated crushed ice from a plastic large-hole mesh armrest in the cold water. Water was circulated through the ice by a pump to prevent local warming about the hand. Participants were instructed to keep the dominant hand in cold water to a depth of 2” above the wrist for as long as they could. The task had an uninformed ceiling of 3 minutes, and participants were asked to keep their hand in for as long as they could, but were informed they may be told to take their hand out sooner.

Pressure Task

The Ugo Basile Analgesy-Meter 37215 (Ugo Basile Biological Research Apparatus, Comerio, Italy) was used to administer focal pressure through a lucite point approximately 1.5 mm in diameter to the second dorsal phalanx of the middle finger and index finger of each hand. Four trials, two at each of two levels of pressure (322.5 g and 465 g), were run with an uninformed ceiling of 3 minutes. Participants were instructed that they would experience pressure and to leave their finger in place for as long as possible, and they were free to remove the weight at any time.

Thermal Heat Task

The Ugo Basile 7360 Unit (Ugo Basile Biological Research Apparatus, Comerio, Italy) was used to administer four trials of two infrared stimulus intensities (15, 20) of radiant heat 2 inches proximal to the wrist and 3 inches distal to the elbow on both volar forearms with an uninformed ceiling of 20 seconds. Participants were informed that the task would involve heat and some discomfort, shown where to place their forearm and told they could move their arm away at any time.

Pain Outcome Measures

For each task, anticipatory anxiety and pain intensity were assessed. Participants were asked to rate pain intensity and anticipatory anxiety using a visual analog scale (VAS). The VAS was rated using a vertical slider, which was anchored with 0 at one end, and 10 at the other. The scale also included corresponding color cues, from white to dark red. The VAS is brief, easily understood and possesses excellent psychometric properties(20).

Anticipatory anxiety was obtained through participants’ visual analogue scale (VAS) ratings in response to the instruction ‘how nervous, afraid, or worried’ they were about the upcoming task. Pain intensity was assessed immediately after each trial by asking participants to use the VAS to rate the amount of pain they experienced during the task. Specifically, participants were asked ‘at its worst, how much pain did you feel?’

Psychological Measures

Pain Coping

Lab Coping Style Interview assessed the specific coping style children favored in response to cold pain. The experimenter asked the following: ‘Some kids think or do certain things while their hand is in the water; What did you do or think about to make it easier to keep your hand in the water longer?’ Children’s responses were tape-recorded and then transcribed verbatim. Participants’ responses were categorized by two independent raters as either "attenders" or "distractors" based on the primary coping strategy used. This procedure was consistent with the methodology and definitions used previously to distinguish attenders from distractors(15, 16). Interrater reliability for assignment to groups was obtained for two raters (Kappa = .96).

Attenders were classified as those who focused their attention toward the task, such as through paying attention to sensory information, focusing on the task, or focusing on any attempts to cope with discomfort. Distractors were classified as those who diverted attention away from the sensations or emotional reactions related to the task, including visual, mental and physical distraction, imagery and relaxation/breathing.

Demographic Variables

A locally developed demographic information questionnaire was given to care-givers who brought their child to the laboratory to participate in the study. The questionnaire assessed demographic information about the child, including age, sex, race/ethnicity, and demographic information about the child’s mother and father, including education attained, occupation and household income. A composite variable was computed for mother and father education, as well as a combined mother/father occupation score using the occupation code from Hollingshead Index of Social Status(21). Occupation was classified into one of nine categories (0–90). with increasingly higher numeric scores denoting increasingly higher occupational status. Codes can be used categorically to determine social class or continuously, with higher scores representing higher status employment. The education variable is representative of parents’ education level, with higher scores indicating greater education attainment. The average education score and average occupation score were used as proxy variables for socioeconomic status (SES). Due to the large number of missing data for household income (missing n = 101), this variable was not used in analyses.

Statistical Analysis

Independent samples t-tests for continuous data and chi-square tests for categorical data were used to examine mean differences between African Americans and Caucasians on demographic variables. Confirmatory analyses using 2 (race: African American vs. Caucasian) × 2 (coping style: attender vs. distractor) ANCOVAs on laboratory pan outcomes were conducted, controlling for demographic covariates that differed between the racial groups. Separate ANCOVAs were conducted for each of the pain outcomes (anticipatory anxiety; pain intensity) for each pain task (cold, pressure and heat). The ANCOVAs tested the main effects of race and of coping style as well as the interaction between race and coping style on the pain outcomes. Significant interaction effects were examined using post hoc Sidak tests on the marginal means to delineate the simple effects. General linear modeling was also used to plot significant interactions and examine simple effects.

Pain intensity ratings for the thermal and pressure tasks were highly correlated across the four trials within each task (r’s = .73 – .83. p < .001). Similarly, anticipatory anxiety ratings for the thermal and pressure tasks were highly correlated across the four trials within each task (r’s = .59 – .71, p < .001). Pain intensity ratings and anticipatory anxiety ratings for the thermal and pressure tasks were therefore averaged across the four trials within each task yielding a single mean value for pressure intensity, heat intensity, pressure anticipatory anxiety, and heat anticipatory anxiety.

Results

Racial Differences in Demographics and Coping

Table 1 shows descriptive statistics for each racial group. There were a number of significant differences on the demographic variables between African Americans and Caucasians. African American children were significantly older than Caucasians (t = 2.16. p = .03); parents of African American children were less likely to attain a higher level of formal education (X2 = 56.63, p = .00) and have higher occupation status (t = 6.65, p = .00) compared to parents of Caucasian children. There were no differences in lab coping style categories by race. Although relative percentages indicated that a higher proportion of African Americans were categorized as attenders compared to Caucasians, this difference was not significant.

Relationships between Coping and Race

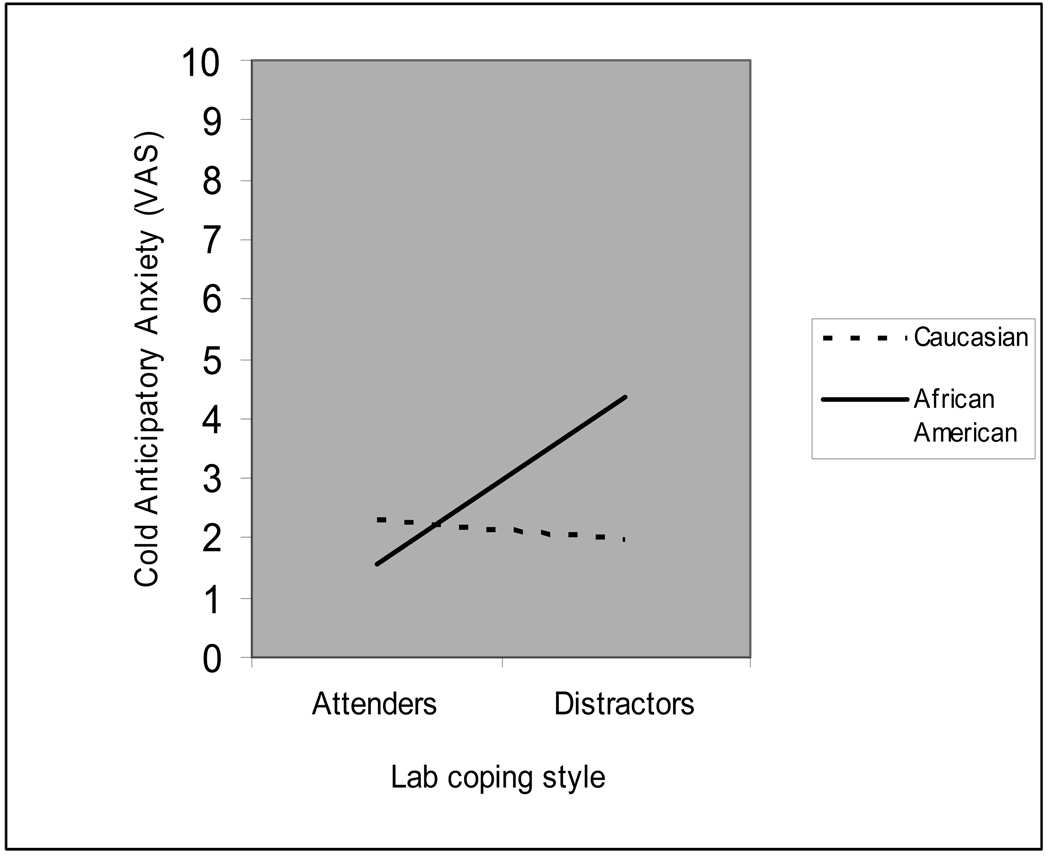

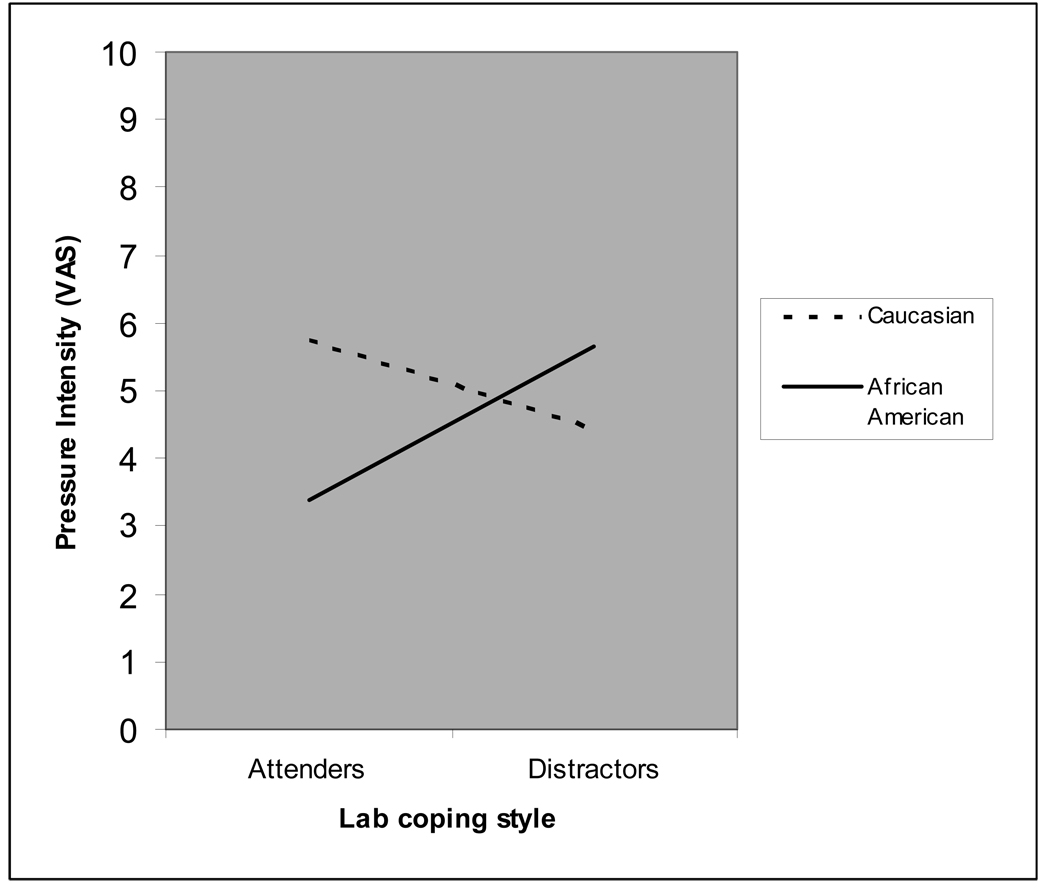

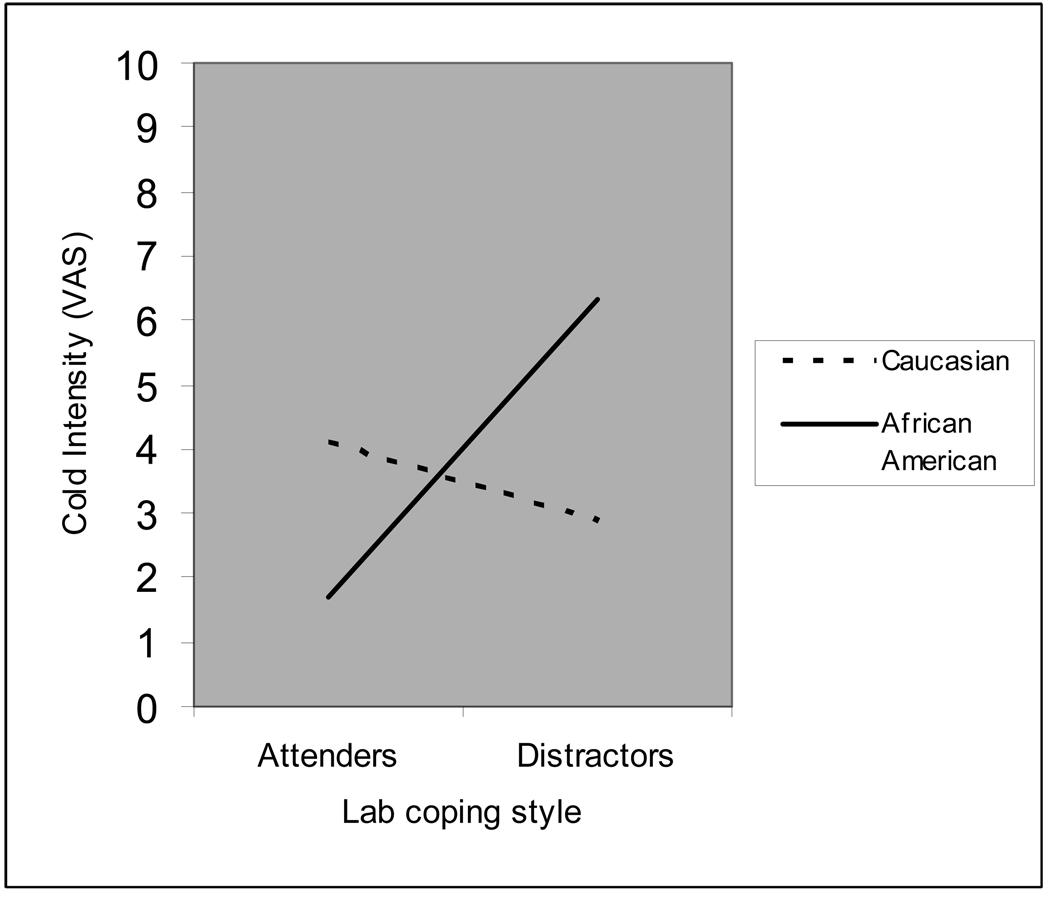

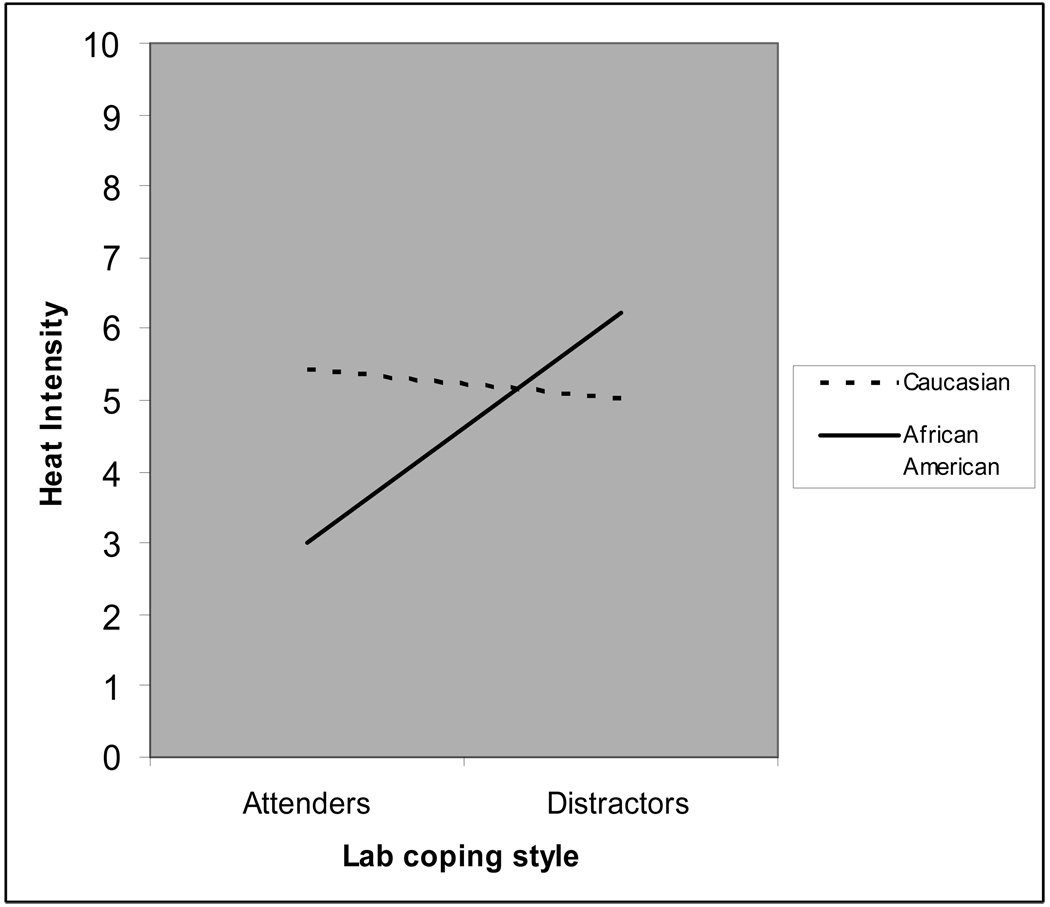

Given the demographic differences between the groups, SES, age and sex were entered as covariates in the ANCOVAs on the pain outcomes. Results of the ANCOVAs including F ratios and p values are reported in Table 3. Marginal means with results from post-hoc Sidak tests for each pain outcome are presented in table 3. The raw means for the pain outcomes by race are presented in table 2. The ANCOVAs indicated a significant main effect for coping on cold intensity only, with distracters reporting higher cold intensity compared to attenders. There were no other significant main effects. Significant race by coping interactions were found for cold anticipatory anxiety, cold intensity, heat intensity and pressure intensity (see table 3).

Table 3.

Results of the ANCOVAs on the marginal means for pain outcomes controlling for sex, age and SES

| Dependent Variables | Independent Variables | Marginal mean (SE) | F (DF) | P | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cold Anticipatory Anxiety | Race | Caucasian | 2.13 (.29) | .87 (1) | .35 |

| African Am | 2.96 (.81) | ||||

| Copying | Attender | 1.92 (.39) | 2.64 (1) | .11 | |

| Distractor | 3.17 (.69) | ||||

| Race X Copying | Caucasian Attender | 2.30 (.38) | 4.39 (1) | .04* | |

| Caucasian Distractor | 1.96 (.44) | ||||

| African Am Attender | 1.56 (.76) | ||||

| African Am Distractor | 4.37 (1.31) | ||||

| Cold Intensity | Race | Caucasian | 3.49 (.32) | .26 (1) | .43 |

| African Am | 4.02 (.90) | ||||

| Coping | Attender | 2.90 (.44) | 4.07 (1) | .04* | |

| Distractor | 4.61 (.77) | ||||

| Race X Coping | Caucasian Attender | 4.10 (.43) | 11.92 (1) | .00** | |

| Caucasian Distractor | 2.88 (.49) | ||||

| African Am Attender | 1.70 (.84) | ||||

| African Am Distractor | 6.34 (1.5) | ||||

| Heat Anticipatory Anxiety | Race | Caucasian | 4.21 (.33) | .30 | .59 |

| African Am | 3.66 (.91) | ||||

| Coping | Attender | 3.63 (.45) | .51 | .48 | |

| Distractor | 4.24 (.78) | ||||

| Race X Coping | Caucasian Attender | 4.62 (.43) | 2.83 | .09 | |

| Caucasian Distractor | 3.81 (.49) | ||||

| African Am Attender | 2.64 (.85) | ||||

| African Am Distractor | 4.67 (1.48) | ||||

| Heat Intensity | Race | Caucasian | 5.24 (.30) | .43 | .51 |

| African Am | 4.62 (.85) | ||||

| Coping | Attender | 4.22 (.41) | 3.12 | .08 | |

| Distractor | 5.63 (.72) | ||||

| Race X Coping | Caucasian Attender | 5.44 (.40) | 5.39 | .02* | |

| Caucasian Distractor | 5.03 (.46) | ||||

| African Am Attender | 3.00 (.79) | ||||

| African Am Distractor | 6.24 (1.37) | ||||

| Pressure Anticipatory Anxiety | Race | Caucasian | 3.30 (.28) | .04 | .84 |

| African Am | 3.13 (.77) | ||||

| Coping | Attender | 2.91 (.38) | .70 | .40 | |

| Distractor | 3.52 (.66) | ||||

| Race X Coping | Caucasian Attender | 3.65 (.37) | 3.39 | .07 | |

| Caucasian Distractor | 2.95 (.42) | ||||

| African Am Attender | 2.17 (.72) | ||||

| African Am Distractor | 4.09 (1.25) | ||||

| Pressure Intensity | Race | Caucasian | 5.10 (.30) | .41 | .52 |

| African Am | 4.51 (.84) | ||||

| Coping | Attender | 4.57 (.41) | .36 | .55 | |

| Distractor | 5.04 (.71) | ||||

| Race X Coping | Caucasian Attender | 5.76 (.40) | 5.28 | .02* | |

| Caucasian Distractor | 4.45 (.45) | ||||

| African Am Attender | 3.39 (.78) | ||||

| African Am Distractor | 5.65 (1.35) | ||||

(p<.05).

Table 2.

Raw mean (SD) scores for pain outcomes by race and coping style

| Pain outcome | African American | Caucasians | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Cold Anticipatory Anxiety (VAS) | |||

| Attender: | 1.44 (2.86) | 2.33 (2.46) | |

| Distractor: | 4.27 (3.26) | 1.99 (1.89) | |

| Cold Intensity (VAS) | |||

| Attender: | 1.83 (2.30) | 4.01 (3.04) | |

| Distractor: | 6.52 (3.77) | 2.94 (2.44) | |

| Heal Anticipatory Anxiety (VAS) | |||

| Attender: | 2.58 (2.19) | 4.64 (2.90) | |

| Distractor: | 4.61 (2.78) | 3.80 (2.70) | |

| Heat Intensity (VAS) | |||

| Attender: | 2.74 (1.84) | 5.54 (2.68) | |

| Distractor: | 5.93 (2.60) | 5.04 (2.59) | |

| Pressure Anticipatory Anxiety (VAS) | |||

| Attender: | 2.34 (2.29) | 3.61 (2.33) | |

| Distractor: | 4.44 (3.03) | 2.89 (2.28) | |

| Pressure Intensity (VAS) | |||

| Attender: | 3.74 (2.50) | 5.59 (2.59) | |

| Distractor: | 6.33 (2.33) | 4.45 (2.43) | |

All the interactions displayed the same pattern; attending was associated with lower levels of pain for African Americans compared to distracting, while distracting was associated with lower levels of pain for Caucasians relative to attending.

Significant Interactions between Ethnicity and Coping

General linear modeling was used to plot the significant race by coping interactions, controlling for sex, age and SES. Figure 1–Figure 4 show the interactions. The relationship between race and coping was consistent across cold anticipatory anxiety, cold intensity, heat intensity and pressure intensity. For African Americans, attending to the pain situation was associated with lower pain sensitivity compared to distraction. In contrast. Caucasians who attended to pain reported increased pain sensitivity, relative to distraction. Analysis of simple effects using general linear modeling revealed that, relative to Caucasian attenders, African Americans attenders reported significantly lower cold intensity (F(1,87)= 5.71, p <.05), pressure intensity (F(1,87)= 6.59, p <.05), and heat intensity (F(1,87)= 6.79, p <.05). In addition, African American distractors reported significantly higher cold intensity than Caucasian distractors (F(1,87)= 5.06, p <.05).

Figure 1.

Significant interaction between race and lab coping for cold anticipatory anxiety controlling for sex, age and SES.

Figure 4.

Significant interaction between race and lab coping for pressure intensity controlling for sex, age and SES.

Discussion

This study demonstrated a relationship between laboratory-based coping, race and experimental pain sensitivity in healthy children. A number of significant interaction effects were demonstrated after controlling for sex as well as age and SES differences between the groups. In African-Americans, a distracting coping style was associated with increased pain responses relative to attending, whereas in Caucasians, a distracting coping style was related to decreased pain responses compared to attending. It appears that lab-based coping style moderates the impact of race on children’s experimental cold, heat and pressure pain responses.

Previous findings relating to the efficacy of distraction versus attention for pain management in healthy individuals are mixed. While distraction appears to decrease pain intensity in adults undergoing cold pressor laboratory pain (22) and pressure pain (23), some studies have found attending to sensations is effective in reducing the pain of childbirth (24) and is superior to distraction in coping with cold pressor pain distress (25). The small number of pain coping studies focusing on children and adolescents have also produced mixed findings. Distraction may be superior in reducing cold pain in younger children, while attending and distraction appear to be equally effective for children older than 10 years of age (26). However, other research has found that children are best able to manage cold pressor pain when they are taught coping strategies consistent with their natural tendencies (16). That is, natural distractors exhibited lower pain responses when taught distraction skills but demonstrated increased pain responses when taught to attend, and vice versa for natural attenders. The results of the present study may qualify previous research. The current results indicate that different pain coping styles may be effective for children of different backgrounds. Previous studies may have produced conflicting results by not accounting for individual differences such as race or ethnicity.

Pain-coping moderators that have been considered in previous literature may shed light on the race-coping interactions found here. One such moderator includes length of task, such that distraction may be most effective in reducing laboratory pain early in the procedure with attending effective for longer trials, perhaps due to a temporary ‘blocking’ effect of pain during distraction, versus an ‘interpretation’ of the pain during attending that allows for a mitigation of sensations over time (27). It is possible that African American children develop similar ‘interpretation’ strategies regardless of pain trial length. Distraction further appears to be effective for low pain-fearful individuals, while attending to pain sensations is effective for high pain-fearful individuals, a finding that is consistent for acute laboratory pain (28) and chronic pain (29). It is possible that due to higher stress levels associated with minority status. African-American children may be more fearful of stress and pain situations, leading to the effective use of attending as a pain coping strategy. Although we found no racial differences in anticipatory anxiety, previous studies have used more general measures of health anxiety and pain-related fear rather than anxiety specific to the pain task. Future studies should explore possible mechanisms behind the interaction between race and coping, including racial differences in health-related fear.

Racial differences in general coping styles have been documented in the adult literature, with African Americans tending to use passive coping styles such as catastrophizing, a style that increases the attentional focus on pain (1,12,13) and Caucasians tending to use more active techniques including ignoring pain (12). We found no significant racial differences in coping strategy classifications and no main effects for race, indicating that African American children were no more sensitive to pain than were Caucasian children, and no more likely to use a particular coping strategy. However, when coping and race were considered together, a specific picture emerged for African Americans and Caucasians that was relatively consistent across pain tasks.

Whether such interactions are long-lasting cannot be answered without longitudinal studies following the pain and coping responses of children of different races. Research is also needed to address why and how such differences arise. What is it about being an African American child that leads to increased anxiety and greater pain sensitivity in response to acute pain stimuli when using distraction, and conversely, for Caucasian children attending to the pain experience? As mentioned, future research should examine how life experiences may lead to such relationships. The family may also prove to be an important explanatory force. Parents of different races may model specific coping styles, which could be explored in research examining how parents react to their own and their child’s laboratory pain.

It is possible that the race by coping interactions seen here represent an early unfolding of the divergent pain sensitivity found in African American and Caucasian adults. Although there were no main effects for race, our finding that African American children using attending were more likely to experience reduced pain compared to Caucasian children who used attending may provide clues as to why African American adults tend to experience greater laboratory and clinical pain than do Caucasian adults (10). In childhood, increased attention to pain may elicit greater relief for African Americans, especially during acute pain situations. Over time, attending to pain may prove less effective, with a corresponding increase in pain sensitivity in African Americans. Recently, it has been argued that the benefits of attending to pain may diminish with exposure to pain, such that attending to pain is not effective for those with previous pain experiences (14). Attending may initially be effective for African American children, but prove less so with repeated exposure to pain. Given evidence suggesting the stability of preferred coping styles developed in childhood (15), it may be difficult to adopt other coping strategies if attending to pain has previously proven rewarding.

It is possible that the interactions found here would not extend to other measures of pain sensitivity. Both lab coping and pain intensity reports are based on recall directly after the pain tasks and immediate memory of the pain could potentially influence the reports. Further, choosing to either attend to sensations or distract oneself is likely to have an impact on attentional capacity to perceive pain, and hence, the degree of intensity an individual reports. Lab coping style also showed an interaction with race in predicting anticipatory anxiety for cold pressor pain. Anticipatory anxiety is a proximal measure of the perceived aversiveness of the pain task, and is involved in the pain experience. Neuroimaging studies have shown similar brain activity during the anticipatory and processing stages of pain stimuli (30). Pain processing often involves expectations based on previous experiences of pain, and anticipatory anxiety is one way of assessing this.

A limitation of the study is the failure to include a wider range of pain variables, including threshold. The present findings demonstrate that certain aspects of pain are more likely to show a relationship to race and coping, and it is possible that pain threshold would have also demonstrated a relationship, since attention is involved in both pain coping and first reported pain. A number of other limitations temper the study’s conclusions. Primarily, the lab specific pain coping measure was only assessed in response to the cold pain task and it is possible that different strategies would have emerged for the pressure and heat tasks. Another limitation is that coping style was categorized in a dichotomous fashion. It may be that the construct of coping style is best represented by a continuum. In addition, coping was categorized based on the primary coping style whereas, coping choices may be more complex involving overlap between attending and distracting. With regards to participants, equal numbers in both racial groups and the inclusion of a wider range of races would have provided richer findings. Although the assessment of SES was a strength of the study, it is possible that other proxy measures of SES would have been more accurate. Generally, a child’s SES can only be inferred through parental variables. Family income may have provided a more global measure of SES than parental education level and occupation status.

Despite the limitations, this study addresses a significant gap in the literature. While there has been limited attention to the role of psychosocial variables in the ethnicity-pain relationship (5), the intersection of pain, ethnicity and psychosocial variables has gone entirely unexamined in children and adolescents. It appears that children’s pain coping is not ‘one size fits all.’ It is important for researchers and clinicians to consider potential moderators in the experience of pain. Variables such as race, ethnicity, coping and their interactions may contribute to varied pain responses in children and adults. The present study represents a starting point to understanding how coping strategies may serve different children in their experience of pain.

Figure 2.

Significant interaction between race and lab coping for cold intensity controlling for sex, age and SES.

Figure 3.

Significant interaction between race and lab coping for heat intensity controlling for sex, age and SES.

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by 2R01DE012754 (PI: Lonnie K. Zeltzer) awarded by the National Institute of Dental and Craniofacial Research

References

- 1.Cano A, Mayo A, Ventimiglia M. Coping, pain severity, interference, and disability: the potential mediating and moderating roles of race and education. J Pain. 2006;7(7):459–468. doi: 10.1016/j.jpain.2006.01.445. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hastic BA, Riley JL, Fillingim RB. Ethnic differences and responses to pain in healthy young adults. Pain Med. 2005;6(1):61–71. doi: 10.1111/j.1526-4637.2005.05009.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Green CR, Baker TA, Sato Y, Washington TL, Smith EM. Race and chronic pain: A comparative study of young black and white Americans presenting for management. J Pain. 2003;4(4):176–183. doi: 10.1016/s1526-5900(02)65013-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Green CR, Baker TA, Smith EM, Sato Y. The effect of race in older adults presenting for chronic pain management: a comparative study of black and white Americans. J Pain. 2003;4(2):82–90. doi: 10.1054/jpai.2003.8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Campbell CM, Edwards RR, Fillingim RB. Ethnic differences in responses to multiple experimental pain stimuli. Pain. 2005;113(1–2):20–26. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2004.08.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kim H, Neubert IK, San Miguel A, Xu K, Krishnaraju RK, Iadarola ML, et al. Genetic influence on variability in human acute experimental pain sensitivity associated with gender, ethnicity and psychological temperament. Pain. 2004;109(3):488–496. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2004.02.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Mechlin MB, Maixner W, Light KC, Fisher JM, Girdler SS. African Americans show alterations in endogenous pain regulatory mechanisms and reduced pain tolerance to experimental pain procedures. Psychosom Med. 2005;67(6):948–956. doi: 10.1097/01.psy.0000188466.14546.68. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Rahim-Williams FB, Riley JL, 3rd, Herrera D, Campbell CM, Hastie BA, Fillingim RB. Ethnic identity predicts experimental pain sensitivity in African Americans and Hispanics. Pain. 2007;129(1–2):177–184. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2006.12.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Zimmer-Gembeck MJ, Locke EM. The socialization of adolescent coping behaviours relationships with families and teachers. J Adolesc. 2007;30(1):1–16. doi: 10.1016/j.adolescence.2005.03.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Edwards RR, Moric M, Husfeldt B, Buvanendran A, Ivankovich O. Ethnic similarities and differences in the chronic pain experience: a comparison of african american, Hispanic, and white patients. Pain Med. 2005;6(1):88–98. doi: 10.1111/j.1526-4637.2005.05007.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lame IE, Peters ML, Vlaeyen JW, Kleef M, Patijn J. Quality of life in chronic pain is more associated with beliefs about pain, than with pain intensity. Eur J Pain. 2005;9(1):15–24. doi: 10.1016/j.ejpain.2004.02.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Jordan MS, Lumley MA, Leisen JC. The relationships of cognitive coping and pain control beliefs to pain and adjustment among African-American and Caucasian women with rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Care Res. 1998;11(2):80–88. doi: 10.1002/art.1790110203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Tan G, Jensen MP, Thornby J, Anderson KO. Ethnicity, control appraisal, coping, and adjustment to chronic pain among black and white Americans. Pain Med. 2005;6(1):18–28. doi: 10.1111/j.1526-4637.2005.05008.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Nouwen A, Cloutier C, Kappas A, Warbrick T, Sheffield D. Effects of focusing and distraction on cold pressor-induced pain in chronic back pain patients and control subjects. J Pain. 2006;7(1):62–71. doi: 10.1016/j.jpain.2005.08.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Tsao JC, Fanurik D, Zeltzer LK. Long-term effects of a brief distraction intervention on children’s laboratory pain reactivity. Behav Modif. 2003;27(2):217–232. doi: 10.1177/0145445503251583. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Fanurik D, Zeltzer IK, Roberts MC, Blount RL. The relationship between children’s coping styles and psychological interventions for cold prcssor pain. Pain. 1993;53(2):213–222. doi: 10.1016/0304-3959(93)90083-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Reid GJ, Chambers CT, McGrath PJ, Finley GA. Coping with pain and surgery: children’s and parents’ perspectives. Int J Behav Med. 1997;4(4):339–363. doi: 10.1207/s15327558ijbm0404_6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lu Q, Zeltzer LK, Tsao JC, Kim SC, Turk N, Naliboff BD. Heart rate mediation of sex differences in pain tolerance in children. Pain. 2005;118(1–2):185–193. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2005.08.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Tsao JC, Myers CD, Craske MG, Bursch B, Kim SC, Zelter LK. Role of anticipatory anxiety and anxiety sensitivity in children’s and adolescents’ laboratory pain responses. J Pediatr Psychol. 2004;29(5):379–388. doi: 10.1093/jpepsy/jsh041. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Gragg RA, Rapoff MA, Danovsky MB, Lindsley CB, Varni JW, Waldron SA, et al. Assessing chronic musculoskeletal pain associated with rheumatic disease: further validation of the pediatric pain questionnaire. J Pediatr Psychol. 1996;21(2):237–250. doi: 10.1093/jpepsy/21.2.237. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hollingshead A. Two factor index of social position. New Haven, CT: Yale University; 1957. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Johnson MH, Petrie SM. The effects of distraction on exercise and cold pressor tolerance for chronic low back pain sufferers. Pain. 1997;69(1–2):43–48. doi: 10.1016/s0304-3959(96)03272-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Brewer B, Karoly P. Effects of attentional focusing on pain perception. Motivation Emotion. 1989;13(3):193–203. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Leventhal EA, Leventhal H, Shacham S, Easterling DV. Active coping reduces reports of pain from childbirth. J Consult Clin Psychol. 1989;57(3):365–371. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.57.3.365. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ahles TA, Blanchard EB, Leventhal H. Cognitive control of pain: Attention to the sensory aspects of the cold pressor stimulus. Cogn Ther Res. 1983;7:159–178. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Piira T, Hayes B, Goodenough B, von Baeyer CL. Effects of attentional direction, age, and coping style on cold-pressor pain in children. Behav Res Ther. 2006;44(6):835–848. doi: 10.1016/j.brat.2005.03.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.McCaul KD, Haugtvedt C. Attention, distraction, and cold-pressor pain. J Pers Soc Psychol. 1982;43(1):154–162. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.43.1.154. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Roelofs J, Peters ML, van der Zijden M, Vlaeyen JW. Does fear of pain moderate the effects of sensory focusing and distraction on cold pressor pain in pain-free individuals? J Pain. 2004;5(5):250–256. doi: 10.1016/j.jpain.2004.04.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hadjistavropoulos HD, Hadjistavropoulos T, Quine A. Health anxiety moderates the effects of distraction versus attention to pain. Behav Res Ther. 2000;38(5):425–438. doi: 10.1016/s0005-7967(99)00044-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Fairhurst M, Wiech K, Dunckley P, Tracey I. Anticipatory brainstem activity predicts neural processing of pain in humans. Pain. 2007;128(1–2):101–110. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2006.09.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]