Abstract

Species in the Botryosphaeriaceae are common plant pathogens and saprobes found on a variety of mainly woody hosts. Teleomorphs typically have hyaline, aseptate ascospores. However, some have been reported with brown ascospores and their taxonomic status is uncertain. A multi-gene approach (SSU, ITS, LSU, EF1-α and β-tubulin) was used to resolve the correct phylogenetic position of the dark-spored ‘Botryosphaeria’ teleomorphs and related asexual species. Neodeightonia and Phaeobotryon are reinstated for species with brown ascospores that are either 1-septate (Neodeightonia) or 2-septate (Phaeobotryon). Phaeobotryosphaeria is reinstated for species with brown, aseptate ascospores that bear an apiculus at either end. The status of Sphaeropsis is clarified and shown to be the anamorph of Phaeobotryosphaeria. Two new genera, namely Barriopsis for species having brown, aseptate ascospores without apiculi and Spencermartinsia for species having brown, 1-septate ascospores with an apiculus at either end are introduced. Species of Dothiorella have brown, 1-septate ascospores and differ from Spencermartinsia in the absence of apiculi. These six genera can also be distinguished from one another based on morphological characters of their anamorphs. Although previously placed in the Botryosphaeriaceae, Dothidotthia, was shown to belong in the Pleosporales, and the new family Dothidotthiaceae is introduced to accommodate it.

Keywords: Barriopsis, Diplodia, Dothiorella, EF1-α, ITS, Lasiodiplodia, LSU, Neodeightonia, Phaeobotryon, Phaeobotryosphaeria, phylogeny, Spencermartinsia, Sphaeropsis, SSU

INTRODUCTION

The genus Botryosphaeria based on the type species, B. dothidea, typically has ascospores that are hyaline and aseptate, although they can become brown and septate with age (Saccardo 1877, von Arx & Müller 1954, 1975, Denman et al. 2000). Because some species of Botryosphaeria have ascospores that become brown with age, von Arx & Müller (1954) placed Dothidea visci with brown ascospores in Botryosphaeria as B. visci. Later, von Arx & Müller (1975) also placed the dark-spored Neodeightonia subglobosa in Botryosphaeria. Since this is the type species of Neodeightonia (1970), this genus was reduced to synonymy with Botryosphaeria (1863). In recognising these synonymies, von Arx & Müller (1954, 1975) broadened the concept of Botryosphaeria to include species with brown ascospores.

At least 18 anamorph genera have been associated with Botryosphaeria. Denman et al. (2000) recognised only two of these, namely Fusicoccum and Diplodia. However, in view of the range of morphologies found in Botryosphaeria anamorphs, the proposal by Denman et al. (2000) is probably too conservative. Although Denman et al. (2000) suggested that Lasiodiplodia could be a synonym of Diplodia, authors of recent papers accept these as distinct genera (Pavlic et al. 2004, Burgess et al. 2006, Damm et al. 2007, Alves et al. 2008).

Phillips et al. (2005) resurrected the genus Dothiorella for species with 1-septate conidia that darken at an early stage of development, and teleomorphs that have brown, 1-septate ascospores. Phylogenetically (ITS+EF1-α) these species fell within the broad morphological concept of Botryosphaeria (Phillips et al. 2005) as recognised by von Arx & Müller (1954, 1975). For these reasons, Phillips et al. (2005) described the teleomorphs of Dothiorella as two new species of Botryosphaeria with brown, 1-septate ascospores. Subsequently, Luque et al. (2005) described another dark-spored Botryosphaeria, namely B. viticola, with a Dothiorella anamorph. Crous et al. (2006) referred to the clade with Dothiorella anamorphs as Dothidotthia because of the strong resemblance of the teleomorphs to that genus. However, in a morphological study of Dothidotthia aspera from diverse hosts, Ramaley (2005) showed that the anamorph is a hyphomycete, Thyrostroma negundinis, and that this species and possibly D. symphoricarpi, type of Dothidotthia, are unrelated to the Botryosphaeriaceae (Schoch et al. 2006).

Although the teleomorphs of Botryosphaeria tend to be morphologically conserved, the anamorphs display a wide range of morphologies. Based on the morphological diversity of the anamorphs linked to species of Botryosphaeria, Crous et al. (2006) suggest that these taxa represent more than a single genus. By including teleomorphs with brown ascospores in Botryosphaeria, Phillips et al. (2005) broadened the concept of the genus even further. Through a study of partial sequences of the LSU gene, Crous et al. (2006) showed that Botryosphaeria s.l. is composed of 10 phylogenetic lineages that correspond to different anamorph genera. To avoid the unnecessary introduction of new generic names, they opted to use existing anamorph generic names for most of the lineages, and restricted the use of Botryosphaeria to B. dothidea and B. corticis. In their phylogeny, a large clade consisting of Diplodia and Lasiodiplodia species was largely unresolved. Within this clade are species known to have hyaline ascospores, e.g. B. corticola, B. stevensii, and others reported to have dark ascospores, e.g. B. subglobosa and B. visci.

The aim of the present study was to use a multigene approach to determine the correct taxonomy and phylogeny of the dark-spored Botryosphaeria-like teleomorphs and their associated anamorphs and to resolve the phylogenetic position of the genus Dothidotthia.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

DNA isolation, PCR amplification and sequencing

Genomic DNA was extracted from mycelium following the method of Alves et al. (2004). PCR reactions were carried out with Taq polymerase, nucleotides and buffers supplied by MBI Fermentas (Vilnius, Lithuania) and PCR reaction mixtures were prepared according to Alves et al. (2004), with the addition of 5 % DMSO to improve the amplification of some difficult DNA templates. All primers used were synthesised by MWG Biotech AG (Ebersberg, Germany).

A portion of the nuclear ribosomal SSU gene was amplified with primers NS1 and NS4 (White et al. 1990). The amplification conditions were as follows: initial denaturation of 5 min at 95 °C, followed by 35 cycles of 45 s at 94 °C, 45 s at 48 °C and 90 s at 72 °C, and a final extension period of 10 min at 72 °C. The nucleotide sequence of the SSU region was determined using the above primers along with the internal sequencing primers NS2 and NS3 (White et al. 1990).

Part of the nuclear rRNA cluster comprising the ITS region plus the D1/D2 variable domains of the ribosomal LSU gene was amplified using the primers ITS1 (White et al. 1990) and NL4 (O’Donnell 1993) as described by Alves et al. (2005). Nucleotide sequences of the ITS and D1/D2 regions were determined as described previously (Alves et al. 2004, 2005) using the primers ITS4 (White et al. 1990) and NL1 (O’Donnell 1993) as internal sequencing primers.

The primers EF1-688F (Alves et al. 2008) and EF1-986R (Carbone & Kohn 1999) and Bt2a and Bt2b (Glass & Donaldson 1995) were used to amplify and sequence part of the translation elongation factor 1-alpha (EF1-α) gene and part of the β-tubulin gene, respectively. Amplification and nucleotide sequencing of the EF1-α and β-tubulin genes was performed as described previously (Alves et al. 2006, 2008).

The amplified PCR fragments were purified with the JETQUICK PCR Purification Spin Kit (GENOMED, Löhne, Germany). Both strands of the PCR products were sequenced according to the procedures described previously (Alves et al. 2004), while some were sequenced by STAB Vida Lda (Portugal). The nucleotide sequences were read and edited with FinchTV 1.4.0 (Geospiza Inc. http://www.geospiza.com/finchtv). All sequences were checked manually and nucleotide arrangements at ambiguous positions were clarified using both primer direction sequences.

Phylogenetic analyses

Sequences were aligned with ClustalX v. 1.83 (Thompson et al. 1997), using the following parameters: pairwise alignment parameters (gap opening = 10, gap extension = 0.1) and multiple alignment parameters (gap opening = 10, gap extension = 0.2, transition weight = 0.5, delay divergent sequences = 25 %). Alignments were checked and manual adjustments were made where necessary. Phylogenetic information contained in indels (gaps) was incorporated into the phylogenetic analyses using simple indel coding as implemented by GapCoder (Young & Healy 2003).

Phylogenetic analyses of sequence data were done using PAUP v. 4.0b10 (Swofford 2003) for Maximum-parsimony (MP) analyses and Mr Bayes v. 3.0b4 (Ronquist & Huelsenbeck 2003) for Bayesian analyses. Trees were visualised with TreeView (Page 1996).

Maximum-parsimony analyses were performed using the heuristic search option with 1 000 random taxa addition and tree bisection and reconnection (TBR) as the branch-swapping algorithm. All characters were unordered and of equal weight and gaps were treated as missing data. Branches of zero length were collapsed and all multiple, equally parsimonious trees were saved. The robustness of the most parsimonious trees was evaluated from 1 000 bootstrap replications (Hillis & Bull 1993). Other measures used were consistency index (CI), retention index (RI) and homoplasy index (HI).

Bayesian analyses employing a Markov Chain Monte Carlo method were performed. The general time-reversible model of evolution (Rodriguez et al. 1990), including estimation of invariable sites and assuming a discrete gamma distribution with six rate categories (GTR+Γ+G) was used. Four MCMC chains were run simultaneously, starting from random trees for 1 000 000 generations. Trees were sampled every 100th generation for a total of 10 000 trees. The first 1 000 trees were discarded as the burn-in phase of each analysis. Posterior probabilities (Rannala & Yang 1996) were determined from a majority-rule consensus tree generated with the remaining 9 000 trees. This analysis was repeated three times starting from different random trees to ensure trees from the same tree space were sampled during each analysis.

In this study we assessed the possibility of combining the individual datasets by comparing highly supported clades among trees generated from the different datasets to detect conflict. High support typically refers to bootstrap support values ≥ 70 % and Bayesian posterior probabilities ≥ 95 % (Alfaro et al. 2003). If no conflict exists between the highly supported clades in trees generated from these different datasets, it is likely that the genes share similar phylogenetic histories and phylogenetic resolution and support could ultimately be increased by combining the datasets (Miller & Huhndorf 2004).

RESULTS

Phylogenetic analyses

Partial nucleotide sequences of the SSU ribosomal DNA (1134 bp), the ITS region (500–600 bp), the D1/D2 variable domains of the LSU ribosomal DNA (614 bp), β-tubulin (approx. 400 bp) and EF1-α genes (approx. 300 bp) were determined for several isolates. The other sequences used in the analyses were retrieved from GenBank (Table 1). Sequences of the five genes were aligned and analysed separately by MP and Bayesian analyses, and the resulting trees were compared. No conflicts were detected between single gene phylogenies indicating that the datasets could be combined. New sequences were deposited in GenBank (Table 1) and the alignments in TreeBASE (SN 3881).

Table 1.

Isolates studied in this paper.

| Species | Accession number1 | Host | Locality | GenBank2 |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SSU | LSU | ITS | EF1-α | β-tubulin | ||||

| Barriopsis fusca | CBS 174.26 | Citrus sp. | Cuba | EU673182 | DQ377857 | EU673330 | EU673296 | EU673109 |

| Bimuria novaezelandiae | CBS 107.79 | soil | New Zealand | AY016338 | AY016356 | – | – | – |

| Botryosphaeria corticis | CBS119047 | Vaccinium corymbosum | USA | EU673175 | EU673244 | DQ299245 | EU017539 | EU673107 |

| ATCC 22927 | Vaccinium sp. | USA | EU673176 | EU673245 | DQ299247 | EU673291 | EU673108 | |

| Botryosphaeria dothidea | CBS 115476 | Prunus sp. | Switzerland | EU673173 | AY928047 | AY236949 | AY236898 | AY236927 |

| CBS 110302 | Vitis vinifera | Portugal | EU673174 | EU673243 | AY259092 | AY573218 | EU673106 | |

| ‘Botryosphaeria’ tsugae | CBS 418.64 | Tsuga heterophylla | Canada | EU673208 | DQ377867 | DQ458888 | DQ458873 | DQ458855 |

| Byssothecium circinans | CBS 675.92 | Medicago sativa | USA | AY016339 | AY016357 | – | – | – |

| Capnodium coffeae | CBS 147.52 | Coffea robusta | Zaire | DQ247808 | DQ247800 | – | – | – |

| Cochliobolus heterostrophus | AFTOL 54 | Zea mays | Unknown | AY544727 | AY544645 | – | – | – |

| Davidiella tassiana | AFTOL 1591 | man, skin, foot | Netherlands | DQ678022 | DQ678074 | – | – | – |

| Delitschia winteri | AFTOL 1599 | dung of rabbit | Netherlands | DQ678026 | DQ678077 | – | – | – |

| Didymella cucurbitacearum | IMI 373225 | Unknown | USA | AY293779 | AY293792 | – | – | – |

| Diplodia acerina | CBS 910.73 | Acer pseudoplatanus | Germany | EU673160 | EU673234 | EU673315 | EU673282 | EU673139 |

| Diplodia corticola | CBS 112549 | Quercus suber | Portugal | EU673206 | AY928051 | AY259100 | AY573227 | DQ458853 |

| CBS 112546 | Quercus ilex | Spain | EU673207 | EU673262 | AY259090 | EU673310 | EU673117 | |

| Diplodia coryli | CBS 242.51 | Unknown | Italy | EU673162 | EU673235 | EU673317 | EU673284 | EU673105 |

| Diplodia cupressi | CBS 168.87 | Cupressus sempervirens | Israel | EU673209 | EU673263 | DQ458893 | DQ458878 | DQ458861 |

| CBS 261.85 | Cupressus sempervirens | Israel | EU673210 | EU673264 | DQ458894 | DQ458879 | DQ458862 | |

| Diplodia juglandis | CBS 188.87 | Juglans regia | France | EU673161 | DQ377891 | EU673316 | EU673283 | EU673119 |

| Diplodia mutila | CBS 112553 | Vitis vinifera | Portugal | EU673213 | AY928049 | AY259093 | AY573219 | DQ458850 |

| CBS 230.30 | Phoenix dactylifera | USA | EU673214 | EU673265 | DQ458886 | DQ458869 | DQ458849 | |

| Diplodia pinea A | CBS 393.84 | Pinus nigra | Netherlands | EU673219 | DQ377893 | DQ458895 | DQ458880 | DQ458863 |

| CBS 109727 | Pinus radiata | South Africa | EU673220 | EU673269 | DQ458897 | DQ458882 | DQ458865 | |

| Diplodia pinea C | CBS 109725 | Pinus patula | South Africa | EU673222 | EU673270 | DQ458896 | DQ458881 | DQ458864 |

| CBS 109943 | Pinus patula | Indonesia | EU673221 | EU673271 | DQ458898 | DQ458883 | DQ458866 | |

| Diplodia rosulata | CBS 116470 | Prunus africana | Ethiopia | EU673211 | DQ377896 | EU430265 | EU430267 | EU673132 |

| CBS 116472 | Prunus africana | Ethiopia | EU673212 | DQ377897 | EU430266 | EU430268 | EU673131 | |

| Diplodia scrobiculata | CBS 113423 | Pinus greggii | Mexico | EU673217 | EU673267 | DQ458900 | DQ458885 | DQ458868 |

| CBS 109944 | Pinus greggii | Mexico | EU673218 | EU673268 | DQ458899 | DQ458884 | DQ458867 | |

| Diplodia seriata | CBS 112555 | Vitis vinifera | Portugal | EU673215 | AY928050 | AY259094 | AY573220 | DQ458856 |

| CBS 119049 | Vitis sp. | Italy | EU673216 | EU673266 | DQ458889 | DQ458874 | DQ458857 | |

| Dothidea sambuci | AFTOL 274 | Unknown | Unknown | AY544722 | AY544681 | – | – | – |

| Dothidotthia sp. | CPC 12928 | Fendlera rupicola | USA | EU673225 | EU673272 | – | – | – |

| Dothidotthia sp. | CPC 12930 | Euonymus alatus | USA | EU673226 | EU673274 | – | – | – |

| Dothidotthia sp. | CPC 12932 | Acer negundis | USA | EU673227 | EU673275 | – | – | – |

| Dothidotthia sp. | CPC 12933 | Acer negundis | USA | EU673228 | EU673276 | – | – | – |

| Dothidotthia symphoricarpi | CPC 12929 | Symphoricarpos rotundifolia | USA | EU673224 | EU673273 | – | – | – |

| Dothiora cannabinae | AFTOL 1359 | Daphne cannabina | India | DQ479933 | DQ470984 | – | – | – |

| Dothiorella iberica | CBS 115041 | Quercus ilex | Spain | EU673155 | AY928053 | AY573202 | AY573222 | EU673096 |

| CBS 113188 | Quercus suber | Spain | EU673156 | EU673230 | AY573198 | EU673278 | EU673097 | |

| Dothiorella sarmentorum | IMI 63581b | Ulmus sp. | United Kingdom | EU673158 | AY928052 | AY573212 | AY573235 | EU673102 |

| CBS 115038 | Malus pumila | Netherlands | EU673159 | DQ377860 | AY573206 | AY573223 | EU673101 | |

| Dothiorella sp. | CAA 005 | Pistacia vera | USA | EU673157 | EU673231 | EU673312 | EU673279 | EU673098 |

| Dothiorella sp. | CAP 187 | Prunus dulcis | Portugal | EU673163 | EU673232 | EU673313 | EU673280 | EU673100 |

| Dothiorella sp. | JL 599 | Corylus avellana | Spain | EU673164 | EU673233 | EU673314 | EU673281 | EU673099 |

| Elsinoë veneta | AFTOL 1360 | Rubus sp. | Unknown | DQ678007 | DQ678060 | – | – | – |

| Guignardia bidwelli | CBS 111645 | Parthenocissus quinquefolia | USA | EU673223 | DQ377876 | – | – | – |

| Hysteropatella clavispora | AFTOL 1305 | Salix sp. | USA | DQ678006 | AY541493 | – | – | – |

| Lasiodiplodia crassispora | CBS 110492 | Unknown | Unknown | EU673189 | EU673251 | EF622086 | EF622066 | EU673134 |

| CBS 118741 | Santalum album | Australia | EU673190 | DQ377901 | DQ103550 | EU673303 | EU673133 | |

| Lasiodiplodia gonubiensis | CBS 115812 | Syzygium cordatum | South Africa | EU673193 | DQ377902 | DQ458892 | DQ458877 | DQ458860 |

| CBS 116355 | Syzygium cordatum | South Africa | EU673194 | EU673252 | AY639594 | DQ103567 | EU673126 | |

| Lasiodiplodia parva | CBS 356.59 | Theobroma cacao | Sri Lanka | EU673200 | EU673257 | EF622082 | EF622062 | EU673113 |

| CBS 494.78 | Cassava-field soil | Colombia | EU673201 | EU673258 | EF622084 | EF622064 | EU673114 | |

| Lasiodiplodia pseudotheobromae | CBS 447.62 | Citrus aurantium | Suriname | EU673198 | EU673255 | EF622081 | EF622060 | EU673112 |

| CBS 116459 | Gmelina arborea | Costa Rica | EU673199 | EU673256 | EF622077 | EF622057 | EU673111 | |

| Lasiodiplodia rubropurpurea | CBS 118740 | Eucalyptus grandis | Queensland | EU673191 | DQ377903 | DQ103553 | EU673304 | EU673136 |

| Lasiodiplodia theobromae | CBS 124.13 | Unknown | USA | EU673195 | AY928054 | DQ458890 | DQ458875 | DQ458858 |

| CBS 164.96 | Fruit along coral reef coast | New Guinea | EU673196 | EU673253 | AY640255 | AY640258 | EU673110 | |

| CAA 006 | Vitis vinifera | USA | EU673197 | EU673254 | DQ458891 | DQ458876 | DQ458859 | |

| Lasiodiplodia venezuelensis | CBS 118739 | Acacia mangium | Venezuela | EU673192 | DQ377904 | DQ103547 | EU673305 | EU673129 |

| Lepidosphaeria nicotiae | CBS 559.71 | sandy desert soil | Algeria | DQ384068 | DQ384106 | – | – | – |

| Leptosphaeria maculans | AFTOL 277 | Unknown | Unknown | DQ470993 | DQ470946 | – | – | – |

| Lewia eureka | AFTOL 267 | Medicago rugosa | Australia | DQ677994 | DQ678044 | – | – | – |

| Lophiostoma crenatum | AFTOL 1581 | Prunus spinosa | Switzerland | DQ678017 | DQ678069 | – | – | – |

| Massaria platani | AFTOL 1574 | Platanus occidentalis | USA | DQ678013 | DQ678065 | – | – | – |

| Massarina arundinacea | CBS 619.86 | Phragmites australis | Switzerland | DQ813513 | DQ813509 | – | – | – |

| Montagnula opulenta | AFTOL 1734 | Opuntia sp. | Unknown | AF164370 | DQ678086 | – | – | – |

| Mycosphaerella punctiformis | AFTOL 942 | Quercus robur | Netherlands | DQ471017 | DQ470968 | – | – | – |

| Myriangium duriaei | CBS 260.36 | Chrysomphalus aonidium | Argentina | AY016347 | AY016365 | – | – | – |

| Neodeightonia phoenicum | CBS 169.34 | Phoenix dactylifera | USA | EU673203 | EU673259 | EU673338 | EU673307 | EU673138 |

| CBS 123168 | Phoenix canariensis | Spain | EU673204 | EU673260 | EU673339 | EU673308 | EU673115 | |

| CBS 122528 | Phoenix dactylifera | Spain | EU673205 | EU673261 | EU673340 | EU673309 | EU673116 | |

| Neodeightonia subglobosa | CBS 448.91 | keratomycosis in eye | United Kingdom | EU673202 | DQ377866 | EU673337 | EU673306 | EU673137 |

| Neofusicoccum luteum | CBS 110299 | Vitis vinifera | Portugal | EU673148 | AY928043 | AY259091 | AY573217 | DQ458848 |

| CBS 110497 | Vitis vinifera | Portugal | EU673149 | EU673229 | EU673311 | EU673277 | EU673092 | |

| Neofusicoccum mangiferum | CBS 118531 | Mangifera indica | Australia | EU673153 | DQ377920 | AY615185 | DQ093221 | AY615172 |

| CBS 118532 | Mangifera indica | Australia | EU673154 | DQ377921 | AY615186 | DQ093220 | AY615173 | |

| Neofusicoccum parvum | CMW 9081 | Pinus nigra | New Zealand | EU673151 | AY928045 | AY236943 | AY236888 | AY236917 |

| CBS 110301 | Vitis vinifera | Portugal | EU673150 | AY928046 | AY259098 | AY573221 | EU673095 | |

| Neofusicoccum ribis | CBS115475 | Ribes sp. | USA | EU673152 | AY928044 | – | – | – |

| Phaeobotryon mamane | CPC 12264 | Sophora chrysophylla | Hawaii | EU673183 | DQ377898 | EU673331 | EU673297 | EU673125 |

| CPC 12440 | Sophora chrysophylla | Hawaii | EU673184 | EU673248 | EU673332 | EU673298 | EU673121 | |

| CPC 12442 | Sophora chrysophylla | Hawaii | EU673185 | DQ377899 | EU673333 | EU673299 | EU673124 | |

| CPC 12443 | Sophora chrysophylla | Hawaii | EU673186 | EU673249 | EU673334 | EU673300 | EU673120 | |

| CPC 12444 | Sophora chrysophylla | Hawaii | EU673187 | DQ377900 | EU673335 | EU673301 | EU673123 | |

| CPC 12445 | Sophora chrysophylla | Hawaii | EU673188 | EU673250 | EU673336 | EU673302 | EU673122 | |

| Phaeobotryosphaeria citrigena | ICMP 16812 | Citrus sinensis | New Zealand | EU673180 | EU673246 | EU673328 | EU673294 | EU673140 |

| ICMP 16818 | Citrus sinensis | New Zealand | EU673181 | EU673247 | EU673329 | EU673295 | EU673141 | |

| Phaeobotryosphaeria porosa | CBS 110496 | Vitis vinifera | South Africa | EU673179 | DQ377894 | AY343379 | AY343340 | EU673130 |

| Phaeobotryosphaeria visci | CBS 100163 | Viscum album | Luxembourg | EU673177 | DQ377870 | EU673324 | EU673292 | EU673127 |

| CBS 186.97 | Viscum album | Germany | EU673178 | DQ377868 | EU673325 | EU673293 | EU673128 | |

| CBS 122526 | Viscum album | Ukraine | – | – | EU673326 | – | – | |

| CBS 122527 | Viscum album | Ukraine | – | – | EU673327 | – | – | |

| Phaeosphaeria avenaria | AFTOL 280 | Unknown | Unknown | AY544725 | AY544684 | – | – | – |

| Phoma herbarum | AFTOL 1575 | Unknown | Unknown | DQ678014 | DQ678066 | – | – | – |

| Piedraia hortae | CBS 480.64 | man, hair | Brazil | AY016349 | AY016366 | – | – | – |

| Pleomassaria siparia | AFTOL 1600 | Betula verrucosa | Netherlands | DQ678027 | DQ678078 | – | – | – |

| Preussia terricola | AFTOL 282 | Unknown | Unknown | AY544726 | AY544686 | – | – | – |

| Pseudofusicoccum stromaticum | CBS 117448 | Eucalyptus hybrid | Venezuela | EU673146 | DQ377931 | AY693974 | AY693975 | EU673094 |

| CBS 117449 | Eucalyptus hybrid | Venezuela | EU673147 | DQ377932 | DQ436935 | DQ436936 | EU673093 | |

| Sordaria fimicola | – | Unknown | Unknown | AY545724 | AY545728 | – | – | – |

| Spencermartinsia vitícola | CBS 117009 | Vitis vinifera | Spain | EU673165 | DQ377873 | AY905554 | AY905559 | EU673104 |

| CBS 117006 | Vitis vinifera | Spain | EU673166 | EU673236 | AY905555 | AY905562 | EU673103 | |

| Spencermartinsia sp. (as Diplodia medicaginis) | CBS 500.72 | Medicago sativa | South Africa | EU673167 | EU673237 | EU673318 | EU673285 | EU673118 |

| Spencermartinsia sp. (as Diplodia spegazziniana) | CBS 302.75 | Poniciana gilliesii | France | EU673168 | EU673238 | EU673319 | EU673286 | EU673135 |

| Spencermartinsia sp. | ICMP 16827 | Citrus sinensis | New Zealand | EU673171 | EU673241 | EU673322 | EU673289 | EU673144 |

| Spencermartinsia sp. | ICMP 16828 | Citrus sinensis | New Zealand | EU673172 | EU673242 | EU673323 | EU673290 | EU673145 |

| Spencermartinsia sp. | ICMP 16819 | Citrus sinensis | New Zealand | EU673169 | EU673239 | EU673320 | EU673287 | EU673142 |

| Spencermartinsia sp. | ICMP 16824 | Citrus sinensis | New Zealand | EU673170 | EU673240 | EU673321 | EU673288 | EU673143 |

| Xylaria hypoxylon | AFTOL 51 | downed rotting wood | USA | AY544692 | AY544648 | – | – | – |

1 Acronyms of culture collections: AFTOL – Assembling the Fungal Tree of Life; CAA – A. Alves, Universidade de Aveiro, Portugal; CAP – Alan J.L. Phillips, Universidade Nova de Lisboa, Portugal; CBS – Centraalbureau voor Schimmelcultures, Utrecht, The Netherlands; CMW – M.J. Wingfield, FABI, University of Pretoria, South Africa; IMI – CABI Bioscience, Egham, U.K.; JL – J. Luque, IRTA, Spain.

2 Sequence numbers in italics were retrieved from GenBank. All others were obtained in the present study.

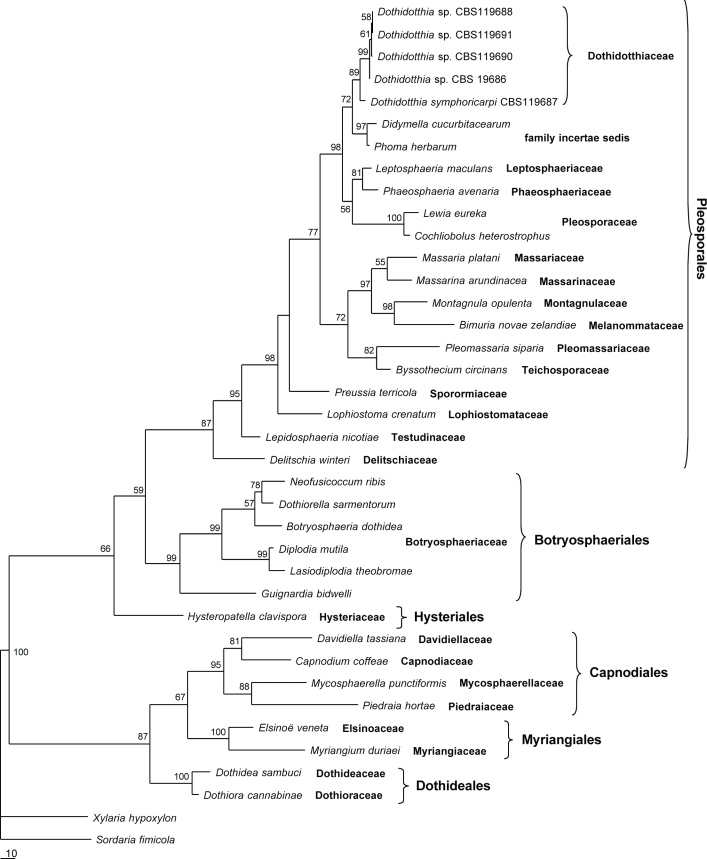

Combined SSU and LSU rDNA sequences of Dothidotthia symphoricarpi isolates were aligned with a set of sequences retrieved from GenBank (Table 1) representing several orders in the Dothideomycetes, as well as two Sordariomycetes sequences that were selected as outgroup taxa (Sordaria fimicola and Xylaria hypoxylon). The combined SSU+LSU alignment consisted of 38 taxa and contained 1742 characters including coded alignment gaps. Indels were coded separately and added to the end of the alignment as characters 1682–1742. Of the 1742 characters, 1203 were constant, while 168 were variable and parsimony uninformative. Maximum parsimony analysis of the remaining 371 parsimony informative characters resulted in a single tree with TL = 1443, CI = 0.5038, RI = 0.7056 and HI = 0.4962. The overall topology of the 50 % majority-rule consensus tree of 10 000 trees sampled during the Bayesian analysis was similar to the MP tree. The MP tree is presented in Fig. 1 with bootstrap support above the branches. The Bayesian tree is available in TreeBASE (SN 3881).

Fig. 1.

Single most parsimonious tree resulting from maximum parsimony analysis of combined SSU and LSU sequence data for 38 taxa. MP bootstrap values are given at the nodes.

Within the ingroup taxa six well-supported clades could be identified, which correspond to known orders belonging to the Dothideomycetes, namely the Dothideales, Myriangiales, Capnodiales, Hysteriales, Botryosphaeriales and Pleosporales. The isolates identified as D. symphoricarpi formed a distinct and well-supported subclade (MP bootstrap = 89 %, posterior probability = 1.00) within the Pleosporales clade. The D. symphoricarpi clade was clearly separated from all families included in the analyses. In both MP and Bayesian analyses the isolates grouped close to Didymella cucurbitacearum and Phoma herbarum (family incertae sedis; de Gruyter et al. in prep.).

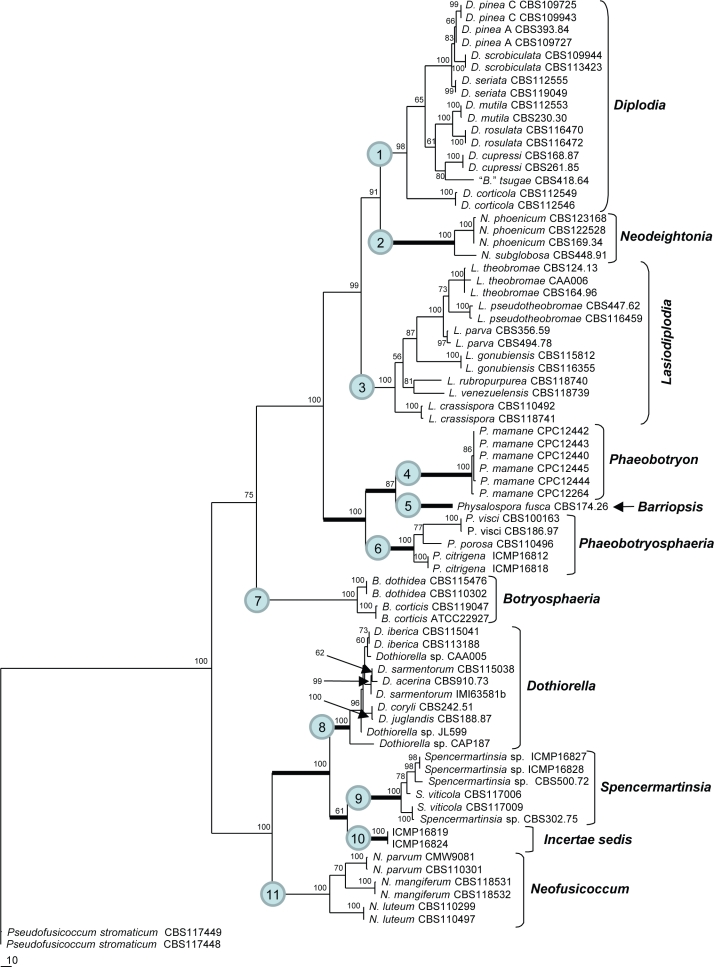

The object of the multigene dataset (SSU, LSU, ITS, β-tubulin and EF1-α) analyses was to determine the phylogenetic relationships of the species with brown ascospores. Therefore Pseudofusicoccum stromaticum was used as outgroup because it lies basal to the Botryosphaeriaceae (Crous et al. 2006). The alignment of 76 isolates consisted of 3470 characters including alignment gaps. Indels were coded separately and added to the end of the alignment as characters 3255–3470. In the analyses, alignment gaps were treated as missing data.

The combined dataset contained 3470 characters, of which 83 were variable and parsimony-uninformative and 2555 were constant. Maximum parsimony analysis of the remaining 832 parsimony-informative characters resulted in eight equal, most parsimonious trees (TL = 1966 steps, CI = 0.6175, RI = 0.9103, RC = 0.5621, HI = 0.3825). The 50 % majority-rule consensus tree of 10 000 trees sampled during the Bayesian analysis had an overall topology similar to the MP trees. One of the MP trees is shown in Fig. 2 with bootstrap support at the branches. The Bayesian tree is available in TreeBASE (SN 3881). In both analyses 11 clades were identified within the ingroup. For convenience these clades are numbered 1–11 in Fig. 2. All of the clades received high bootstrap (87–100 %) and posterior probabilities (0.99–1.00) support.

Fig. 2.

One of eight most parsimonious trees resulting from maximum parsimony analysis of combined SSU, LSU, ITS, β-tubulin and EF1-α sequence data for 76 isolates in the Botryosphaeriaceae. MP bootstrap values are given at the nodes.

TAXONOMY

Position of Dothidotthia

Until now the genus Dothidotthia has been regarded as a member of the Botryosphaeriaceae (Barr 1987). One species of Dothidotthia, D. aspera, was recently shown to have a hyphomycetous anamorph in Thyrostroma (Ramaley 2005), quite unlike the pycnidial anamorphs of members of the Botryosphaeriaceae. The type species of Dothidotthia, D. symphoricarpi, was included in an analysis of the Dothideomycetes (Fig. 1). These data show that Dothidotthia belongs in the Pleosporales, outside any of the known families, and thus a new family in the Pleosporales is introduced.

Dothidotthiaceae Crous & A.J.L. Phillips, fam. nov. — MycoBank MB511706

Ascomata aggregata, erumpescentia, globosa, atrobrunnea. Pseudoparaphyses hyalinus, septatis. Asci octisporis, bitunicati, clavati. Ascosporae brunneae, uniseptatae, ellipsoidae.

Typus. Dothidotthia Höhn.

Anamorph. Thyrostroma.

Ascomata in gregarious clusters, rarely solitary, erumpent, globose, dark brown; wall consisting of 3–6 layers of dark brown textura angularis; basal region giving rise to dark brown, thick-walled hyphae, that extend from the bottom of the ascomata into the substrate. Pseudoparaphyses hyaline, septate, branched in upper part above asci. Asci 8-spored, bitunicate, sessile, clavate, straight to curved. Ascospores brown, ellipsoid, transversely 1-septate. Anamorph hyphomycetous, Thyrostroma.

Dothidotthia Höhn., Ber. Deutsch. Bot. Ges. 36: 312. 1918

Type species. Dothidotthia symphoricarpi (Rehm) Höhn.

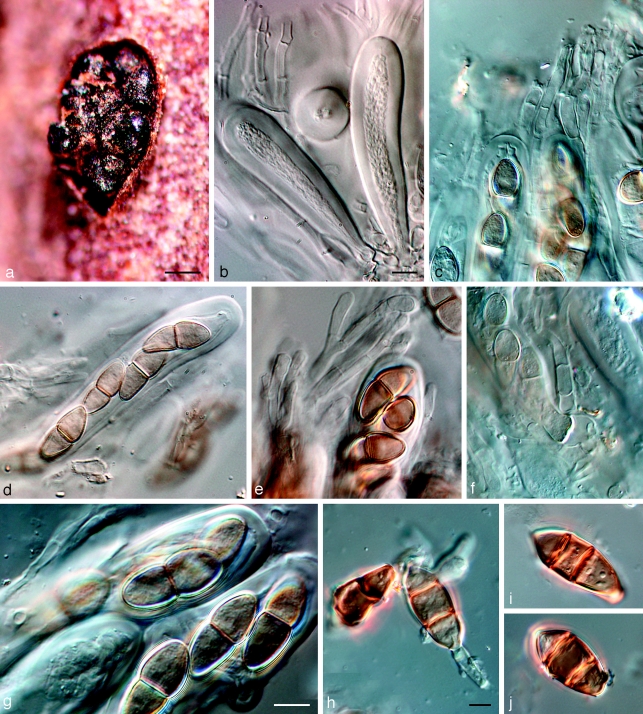

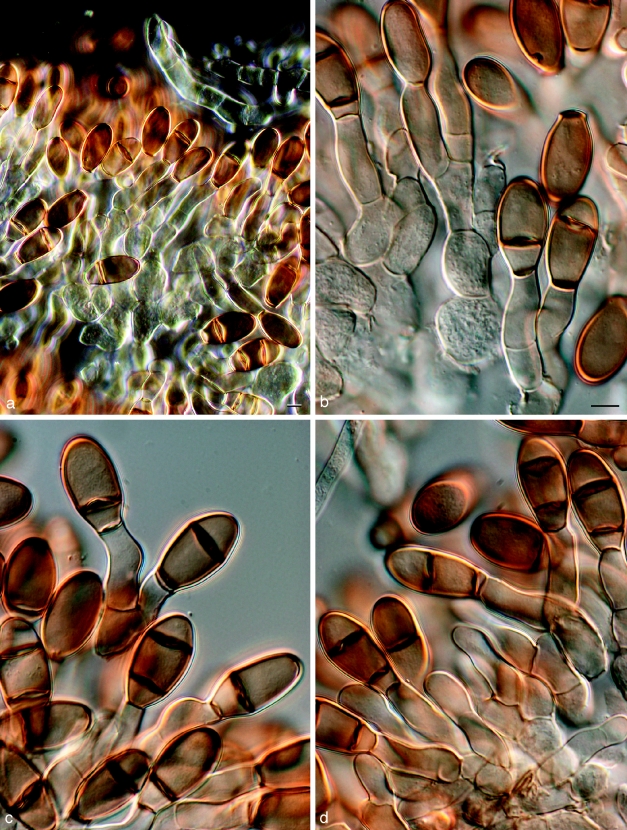

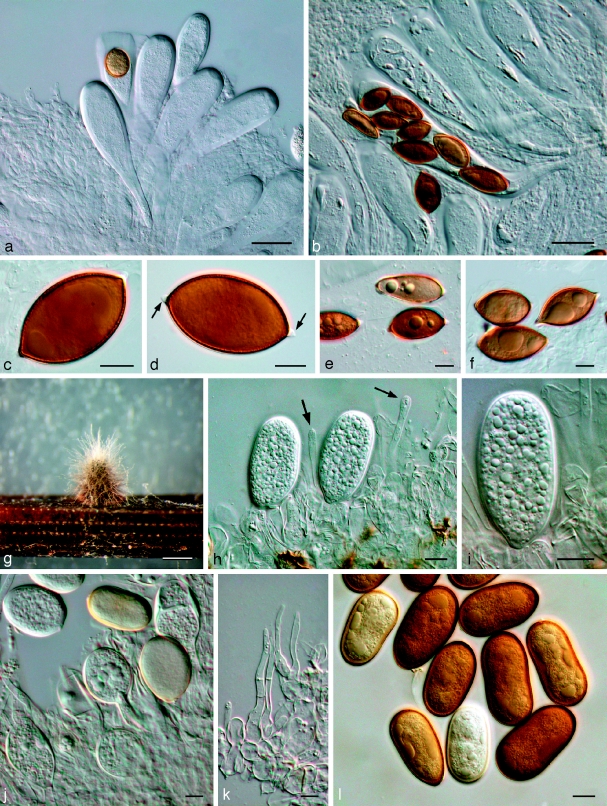

Dothidotthia symphoricarpi (Rehm) Höhn., Ber. Deutsch. Bot. Ges. 36: 312. 1918. — Fig. 3, 4, 5

Fig. 3.

Pseudotthia symphoricarpi holotype NY. a. Ascomata; b. immature asci; c. asci and pseudoparaphyses; d. mature ascus with pale brown 1-septate ascospores; e. brown 1-septate ascospores; f. base of sessile ascus; g. brown 1-septate ascospores; h–j. conidia of Thyrostroma anamorph in association with ascomata. — Scale bars: a = 500 μm; b–h = 10 μm.

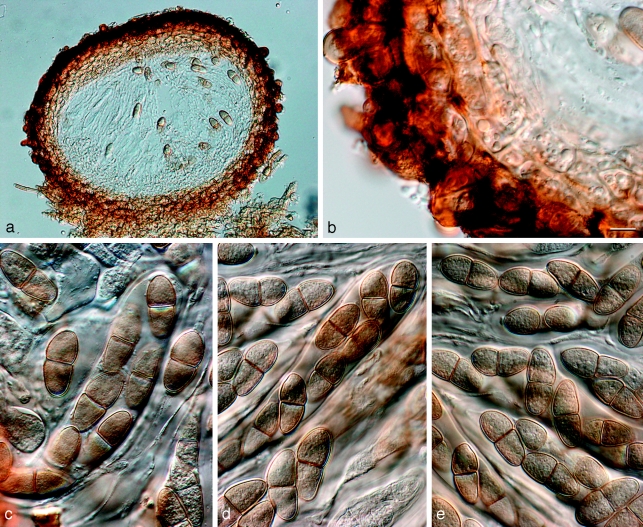

Fig. 4.

Dothidotthia symphoricarpi epitype BPI 871823. a. Longitudinal section through an ascoma; b. detail of a section through the ascoma wall; c, d. asci with pale brown, 1-septate ascospores; e. pale brown, 1-septate ascospores. — Scale bars = 10 μm.

Fig. 5.

Thyrostroma sp. CBS 119691, anamorph of Dothidotthia aspera. a–d. Conidia and conidiophores. — Scale bars = 10 μm.

Basionym. Pseudotthia symphoricarpi Rehm, Ann. Mycol. 11: 169. 1913.

≡ Dibotryon symphoricarpi (Rehm) Petr., Ann. Mycol. 25: 301. 1927.

≡ Gibbera symphoricarpi (Rehm) Arx, Acta Bot. Neerl. 3: 85. 1954.

Anamorph. Thyrostroma negundinis (Berk. & M.A. Curtis) A.W. Ramaley, Mycotaxon 94: 131. (2005) 2006.

Basionym. Coryneum negundinis Berk. & M.A. Curtis, Grevillea 2: 153. 1874.

For additional synonyms see Ramaley (2005).

Ascomata pseudothecial, in gregarious clusters, rarely solitary, erumpent, up to 550 μm diam and 500 μm high; apex somewhat papillate to depressed; wall consisting of 3–6 layers of dark brown textura angularis, 20–80 μm wide, giving rise to dark brown, thick-walled hyphae, 4–6 μm wide, that extend from the bottom of the ascomata into the substratum; reduced to short lateral projections (10–15 μm long) elsewhere on the outer ascomatal wall. Pseudoparaphyses hyaline, septate, 2–3 μm wide, generally not constricted at septa, and branched in upper part above asci. Asci 8-spored, bitunicate, sessile, clavate, 70–120 × 15–22 μm, straight to curved. Ascospores uniformly pale brown, (20–)22–23(−26) × (8–)9–10(−11) μm, ellipsoid, tapering towards subacutely rounded ends, medianly 1-septate, prominently constricted at septum, widest just above septum, smooth.

Specimens examined. Dothidotthia symphoricarpi. USA, North Dakota, on branches of Symphoricarpos occidentalis, holotype of D. symphoricarpi herb. NY; Colorado, San Juan Co, c. 0.5 mile up Engineer Mountain Trail from turnoff at mile 52.5, Hwy 550, dead twigs of Symphoricarpos rotundifolius, 24 June 2004, A.W. Ramaley 0410, epitype designated here as BPI 871823, culture ex-epitype CPC 12929 = CBS 119687.

Notes — Barr (1989) introduced the combination Dothidotthia aspera, but incorrectly listed D. symphoricarpi as synonym. Dothidotthia aspera (Fig. 6) has ascospores that are ellipsoidal with rounded ends, constricted at the medium septum, widest just above the septum, medium brown, smooth to finely verruculose, (20–)32–35(−37) × (12–)13–14(−15) μm. Ascospores of D. symphoricarpi are much smaller, namely (20–)22–23(−26) × (8–)9–10(−11) μm, ellipsoid with rounded ends, constricted at the median septum, widest above septum, finely verruculose, pale brown, and not medium brown as in D. aspera. Ramaley (2005) collected several specimens in this complex, one of which, BPI 871823, is selected to serve as epitype of D. symphoricarpi. Given the new circumscription of this species, the other specimens treated by Ramaley (2005) appear to represent D. aspera, which is morphologically and phylogenetically distinct from both D. symphoricarpi based on the larger ascospores.

Fig. 6.

Amphisphaeria aspera holotype NY. a. Ascomata; b, c. asci with ascospores; d. pseudoparaphyses and ascospores; e. ascospores; f. ascospore and two conidia; g. conidia. — Scale bars: a = 500 μm; b–g = 10 μm.

Dothidotthia aspera (Ellis & Everh.) M.E. Barr, Mycotaxon 34: 519. 1989 — Fig. 6

Basionym. Amphisphaeria aspera Ellis & Everh., Bull. Torrey Bot. Club 27: 52. 1900.

Ascomata pseudothecial, gregarious in groups, rarely solitary, erumpent, up to 600 μm diam, 500 μm high; apex rounded, short papillate to depressed; wall consisting of 3–6 layers of dark brown textura angularis, 20–80 μm wide, giving rise to dark brown, thick-walled hyphae, 4–6 μm wide, that extend from the bottom of the ascomata into the substratum; reduced to short lateral projections elsewhere on the outer ascomatal wall. Pseudoparaphyses hyaline, septate, 2–3 μm wide, not constricted at the septa, branched in the upper parts. Asci 8-spored, bitunicate, sessile, clavate, 65–140 × 10–23 μm. Ascospores medium brown, ellipsoidal with rounded ends, 1-septate, constricted at the median septum, smooth to finely verruculose, (20–)32–35(−37) × (12–)13–14(−15) μm.

Specimens examined. Dothidotthia aspera. USA, Colorado, E. Bethel 517, holotype of Amphisphaeria aspera herb. NY. – Dothidotthia spp. USA, Colorado, Durango, 7 Animas Place, dead twigs of Euonymus alatus, 29 June 2004, A.W. Ramaley 0411, BPI 871820, culture CPC 12930 = CBS 119688; Colorado, Durango, between Animas Place and Animas River, dead twigs of Acer negundo, 8 July 2004, A.W. Ramaley 0414, BPI 871819, anamorph culture CPC 12933 = CBS 119691, teleomorph CPC 12932 = CBS 119690; Colorado, La Plata Co, c. 1.75 mile up Carbon Junction Trail, dead twigs of Fendlera rupicola, 11 May 2004, A.W. Ramaley 0403, BPI 871821, culture CPC 12928 = CBS 119686.

Taxonomy of species with brown ascospores in the Botryosphaeriaceae

The multigene phylogeny revealed 11 clades within the dataset of isolates studied (Fig. 2). Valid generic names are available and currently in use for clade 1 (Diplodia), clade 3 (Lasiodiplodia), clade 7 (Botryosphaeria), clade 8 (Dothiorella) and clade 11 (Neofusicoccum). Neodeightonia and Phaeobotryon are reinstated for clades 2 and 4, respectively. Phaeobotryosphaeria is reinstated for clade 6 and shown to be the teleomorph of Sphaeropsis, the status of which is clarified. No generic names are available for the remaining clades and for this reason Barriopsis and Spencermartinsia are introduced for clades 5 and 9, respectively. The status of clade 10 remains unresolved.

Barriopsis A.J.L. Phillips, A. Alves & Crous, gen. nov. — MycoBank MB511712

Ascomata pseudothecia, brunnea vel nigra. Pseudoparaphyses hyalinae, septatae. Asci clavati, stipitati, octospori, bitunicati cum loculo apicali bene evoluto. Ascosporae ellipsoides, unicellulares, ovoidea, brunnea.

Type species. Barriopsis fusca A.J.L. Phillips, A. Alves & Crous.

Etymology. Named in honour of Margaret E. Barr, who dedicated a large part of her career to resolving the taxonomy of the Dothideomycetes.

Ascomata pseudothecial, scattered or clustered, brown to black, wall composed of several layers of textura angularis, ostiole central. Pseudoparaphyses hyaline, smooth, multiseptate, constricted at septa. Asci bitunicate, clavate, stipitate, thick-walled with thick endotunica and well-developed apical chamber. Ascospores aseptate, ellipsoid to ovoid, brown when mature, without terminal apiculi.

Note — The absence of apiculi differentiate this genus from Sphaeropsis and Phaeobotryosphaeria. The aseptate, brown ascospores without apiculi are unique in the Botryosphaeriaceae.

Barriopsis fusca (N.E. Stevens) A.J.L. Phillips, A. Alves & Crous, comb. nov. — MycoBank MB511713; Fig. 7

Fig. 7.

Barriopsis fusca BPI 599052. a. Immature asci; b. mature asci with brown ascospores; c. ascus with ascospores; d. ascospores. — Scale bars: a, b = 20 μm; c, d = 10 μm.

Basionym. Physalospora fusca N.E. Stevens, Mycologia 18: 210. 1926.

= Phaeobotryosphaeria fusca Petr., Sydowia 6: 317. 1952.

= Botryosphaeria disrupta (Berk. & Curtis) Arx & E. Müll., Beitr. Kryptogamenfl. Schweiz 2, 1: 37. 1954.

Ascomata scattered, immersed, brown to black, separate or aggregated, wall composed of textura angularis, uniloculate, ostiole single, central. Pseudoparaphyses hyaline, smooth, 3–4.5 μm wide, multiseptate with septa 14–18 μm apart. Asci bitunicate, clavate, 8-spored, stipitate, thick-walled with thick endotunica and well-developed apical chamber, 125–180 × 30–36 μm. Ascospores biseriate, aseptate, ellipsoid to oval, straight or slightly curved, apex and base obtuse, without terminal apiculi, wall externally smooth, internally finely verruculose, brown, widest in the middle, (30–)31–36.5(−38.5) × (15.5–)16–18.5(−21) μm, 95 % confidence limits = 32.6–33.4 × 17.0–17.5 μm ( ± S.D. = 33.0 ± 1.5 × 17.2 ± 1.0 μm, L/W ratio = 1.9 ± 0.15).

± S.D. = 33.0 ± 1.5 × 17.2 ± 1.0 μm, L/W ratio = 1.9 ± 0.15).

Specimens examined. Cuba, Herradura, on twigs of Citrus sp., 15 Jan. 1925, N.E. Stevens, holotype BPI 599052, culture ex-type CBS 174.26. – USA, Florida, Orlando, on twigs of Citrus sp., 20 Feb. 1923, C.L. Shear, BPI 599054.

Notes — The ex-type culture could not be induced to sporulate, no doubt because it has been in culture for more than 80 years. According to Stevens (1926) the anamorph is lasiodiplodia-like and he described it as follows: “conidia initially hyaline, aseptate and thick-walled becoming dark brown and septate with irregular longitudinal striations, (20–)23–25(−28) × (11–)12–13(−16) μm”. Stevens (1926) placed this species in Physalospora, but he was obviously hesitant to do so, judging from his statement “To place in the genus Physalospora a fungus with coloured ascospores is of course to do violence to the ideas of that genus”. On account of the bitunicate asci and brown ascospores of this species, Physalospora is clearly unsuitable. Petrak & Deighton (1952) transferred this species to Phaeobotryosphaeria as Phaeobotryosphaeria fusca, presumably on account of its dark ascospores. We examined the type species of Phaeobotryosphaeria (P. yerbae) and found it to have terminal apiculi on the ascospores. Therefore, Phaeobotryosphaeria would also appear to be unsuitable. For this reason we propose the new genus Barriopsis for this fungus. The brown, aseptate ascospores without terminal apiculi are characteristic of this new genus.

Dothiorella Sacc., Michelia 2: 5. 1880

Type species. Dothiorella pyrenophora Sacc.

Dothiorella pyrenophora Sacc., Michelia 2: 5. 1880

Notes — The genus Dothiorella has been the source of much confusion in the past and the name has been used in more than one sense. Dothiorella has been used for anamorphs with hyaline, aseptate conidia similar to those normally associated with Fusicoccum and Neofusicoccum. Presumably this confusion started when Petrak (1922) transferred F. aesculi to Dothiorella, citing the species as the conidial state of B. berengeriana (Sutton 1980). In later years, Dothiorella has been used for fusicoccum-like anamorphs with multiloculate conidiomata (Grossenbacher & Duggar 1911, Barr 1987, Rayachhetry et al. 1996). Sivanesan (1984) confused matters further by placing Dothiorella pyrenophora in synonymy with Dothichiza sorbi, which has small, hyaline, aseptate conidia and is the anamorph of Dothiora pyrenophora (Fr.) Fr. However, he was referring to Dothiorella pyrenophora Sacc. (1884), which is a later homonym of Dothiorella pyrenophora Sacc. (1880) (Sutton 1977). The taxonomic history of Dothiorella has been explained by Sutton (1977) and Crous & Palm (1999), and is illustrated by Crous & Palm (1999).

Dothiorella was reduced to synonymy under Diplodia by Crous & Palm (1999), who used a broad morphological concept for Diplodia. Phillips et al. (2005) re-examined the type of Dothiorella pyrenophora Sacc. (K 54912) and stated that it differed from Diplodia by having conidia that are brown and 1-septate early in their development, while they are still attached to the conidiogenous cells. In Diplodia conidial darkening and septation takes place after discharge from the pycnidia. Crous et al. (2006) re-examined the types of both Diplodia and Dothiorella and confirmed these morphological differences. Teleomorphs of Dothiorella have pigmented, septate ascospores.

Dothiorella sarmentorum (Fr.) A.J.L. Phillips, A. Alves & J. Luque, Mycologia 97: 522. 2005

Basionym. Sphaeria sarmentorum Fr., Kongl. Vetensk. Acad. Handl., n.s. 39: 107. 1818.

≡ Diplodia sarmentorum (Fr.) Fr., Summa Veg. Scand. 2: 417. 1849.

= Diplodia pruni Fuckel, Jahrb. Nassauischen Vereins Naturk. 23–24: 169. (1869–1870) 1870.

Teleomorph. Botryosphaeria sarmentorum A.J.L. Phillips, A. Alves & J. Luque, Mycologia 97: 522. 2005.

Specimens examined. England, Warwickshire, on Ulmus sp., Aug. 1956, E.A. Ellis, holotype of Otthia spiraeae, IMI 63581b, culture ex-holotype IMI 63581b. – Sweden, Lund, Botanical Garden, on Menispermum canadense, 1818, E.M. Fries (holotype of Sphaeria sarmentorum) Scleromyc. Suec. 18, isotype K(M) 104852.

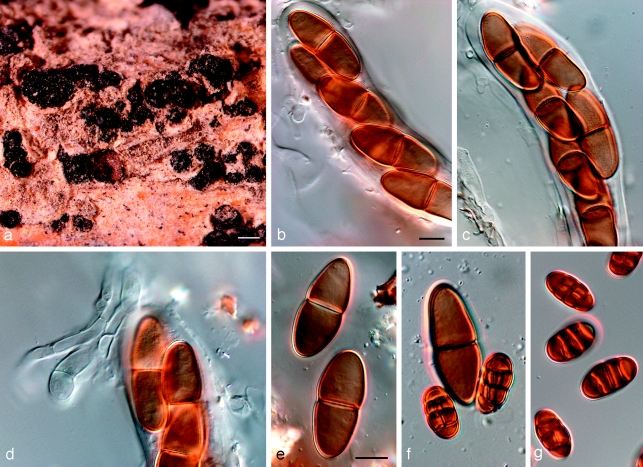

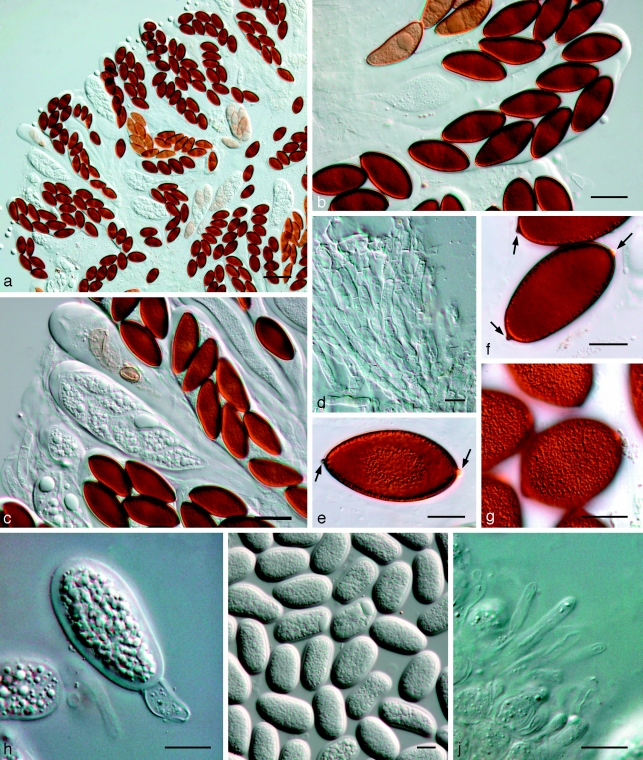

Dothiorella iberica A.J.L. Phillips, J. Luque & A. Alves, Mycologia 97: 524. 2005 — Fig. 8

Fig. 8.

Dothiorella iberica. a–g: LISE 94944; h–n: CBS 115041. a. Vertical section through an ascoma; b. ascus with brown, 1-septate ascospores; c. immature asci and one ascus with four ascospores; d. details of ascoma wall; e. pseudoparaphyses; f. ascospores; g. ascospore; h. young conidiogenous cells; i. conidiogenous cells with developing conidia; j, k conidia viewed at two different levels of focus to show internally verruculose wall; l, m. conidia; n. germinating conidia. — Scale bars: a = 50 μm; b–n: 10 μm.

Teleomorph. Botryosphaeria iberica A.J.L. Phillips, J. Luque & A. Alves, Mycologia 97: 524. 2005.

Specimens examined. Spain, Aragon, Tarazona, on dead twigs of Quercus ilex, 18 Dec. 2002, J. Luque, holotype of B. iberica LISE 94944, culture ex-type CBS 115041, LISE 94942 = CBS 115035.

Notes — This species is similar to Dothiorella sarmentorum but can be distinguished on characteristics of the asci, ascospores and conidia. Thus, in D. iberica the asci are shorter and more clavate, the ascospores characteristically taper towards the base, and on average the conidia are slightly longer.

Within the Dothiorella clade there is a subclade consisting of Diplodia coryli (CBS 242.51) and Diplodia juglandis (CBS 188.87). However, neither of these two isolates is authentic, and neither could be induced to sporulate. Thus, their identity and distinction from other species could not be determined. Two other isolates (CAP187 from Prunus dulcis in Portugal, and JL599 from Corylus avellana in Spain) identified as Dothiorella spp. formed two further clades. However, these clades are represented by single isolates and were not considered any further. Nevertheless, it is clear that Dothiorella is genetically diverse and further collections will undoubtedly yield more species.

Neodeightonia C. Booth, Mycol. Pap. 119: 17. (1969) 1970.

Type species. Neodeightonia subglobosa C. Booth.

Neodeightonia subglobosa C. Booth, Mycol. Pap. 119: 19. (1969) 1970.

Anamorph. Sphaeropsis subglobosa Cooke, Grevillea 7: 95. 1879, as ‘subglobosum’.

Specimens examined. Sierra Leone, Njala (Kori), on dead culms of Bambusa arundinacea, 17 Aug. 1954, F.C. Deighton, holotype IMI 57769 (c). – Unknown location, human, keratomycosis of eye, Aug. 1991, Kirkness, CBS 448.91.

Note — We examined the type specimen of Neodeightonia subglobosa and found only immature asci with hyaline ascospores. However, Punithalingam (1969) clearly described and illustrated the ascospores as brown and 1-septate. Von Arx & Müller (1954) transferred N. subglobosa to Botryosphaeria, and because this is the type species of the genus, they reduced Neodeightonia to synonymy under Botryosphaeria. However, morphologically (based on the dark, 1-septate ascospores) and phylogenetically, this genus is distinguishable from Botryosphaeria, and the genus is therefore reinstated here. Punithalingam (1969) referred to a germ slit in the conidia. Crous et al. (2006) suggested that this is in fact a striation on the conidial wall, and that more than one could occur per conidium, a feature confirmed in the present study (Fig. 9). Such striate walls suggest an affinity to Lasiodiplodia. Nevertheless, Neodeightonia can be distinguished from Lasiodiplodia by the absence of pycnidial paraphyses. Thus, conidial striations distinguish Neodeightonia from Diplodia, and the absence of pycnidial paraphyses distinguishes it from Lasiodiplodia.

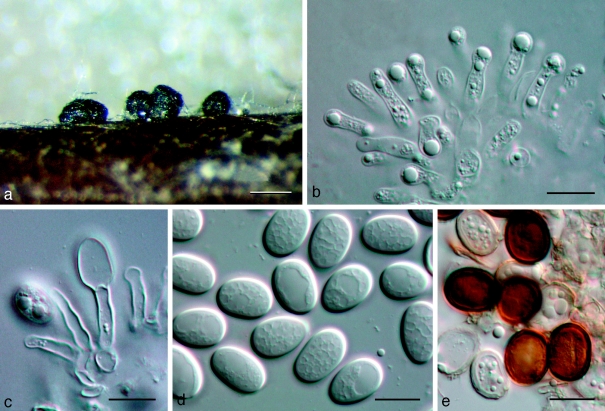

Fig. 9.

Neodeightonia subglobosa CBS 448.91. a. Globose conidiomata; b, c. conidiogenous cells; d. hyaline conidia; e. mature brown conidia. — Scale bars: a = 250 μm; b–e = 10 μm.

Neodeightonia phoenicum A.J.L. Phillips & Crous, sp. nov. — MycoBank MB511708; Fig. 10

Fig. 10.

Neodeightonia phoenicum CBS 122528. a. Conidiogenous layer; b–e. conidiogenous cells; f. hyaline, aseptate conidia; g, h. brown, 1-septate conidia with longitudinal striations. — Scale bars = 10 μm.

Conidiomata brunnea vel nigra, in contextu hospitis inclusa, multilocularia, globosa. Cellulae conidiogenae holoblasticae, hyalinae, cylindricae, percurrenter cum 1–2 proliferationibus prolificentes, vel in plano eodem periclinaliter incrassatae. Conidia (14.5–)17–21(−24) × (9–)10–12.5(−14) μm ovoidea vel ellipsoidea, apicibus rotundato, in fundo rotundato, parietibus crassis, primaria hyalinae, cum maturitate brunnea, longitudinaliter striata et unum septa formantia.

Anamorph. Macrophoma phoenicum Sacc., Annuario Reale Ist. Bot. Roma 4: 195. 1890.

≡ Diplodia phoenicum (Sacc.) H.S. Fawc. & Klotz, Bull. Calif. Agric. Exp. Station 522: 8. 1932.

≡ Strionemadiplodia phoenicum (Sacc.) Zambett., Bull. Trimestriel Soc. Mycol. France 70: 235. (1954) 1955.

Conidiomata formed on pine needles in culture pycnidial, multiloculate, dark brown to black, immersed in the host, becoming erumpent when mature. Conidiogenous cells hyaline, smooth, cylindrical, swollen at base, holoblastic, proliferating percurrently to form one or two annellations, or proliferating at same level giving rise to periclinal thickenings. Conidia ovoid to ellipsoid, apex and base broadly rounded, widest in middle to upper third, thick-walled, initially hyaline and aseptate, becoming dark brown and 1-septate some time after discharge from pycnidia, with melanin deposits on inner surface of wall arranged longitudinally giving a striate appearance to conidia, (14.5–)17–21(−24) × (9–)10–12.5(−14) μm, 95 % confidence limits = 18.6–19.5 × 11.2–11.8 μm ( ± S.D. = 19.1 ± 1.7 × 11.5 ± 1.1 μm, l/w ratio = 1.7 ± 0.2).

± S.D. = 19.1 ± 1.7 × 11.5 ± 1.1 μm, l/w ratio = 1.7 ± 0.2).

Specimens examined. Spain, Catalonia, Tarragona, Salou, on Phoenix sp., F. Garcia, holotype CBS H-20108, culture ex-type CBS 122528; Catalonia, Barcelona, Vilanova i la Geltrú, on Phoenix canariensis, 17 May 2004, M. Rojo, CBS 123168. – USA, California, on Phoenix dactylifera, Mar. 1934, H.S. Fawcett, CBS 169.34.

Notes — Zambettakis (1955) placed this species in Strionemadiplodia (based on the striate conidia). However, the teleomorphic genus Neodeightonia is available for this species. The absence of pycnidial paraphyses distinguishes Neodeightonia from Lasiodiplodia, while the striate conidia distinguish it from Diplodia. Although Punithalingam (1969) reported that the teleomorph of N. subglobosa forms in culture, our isolates of N. phoenicum failed to do so, even after long periods of incubation (> 3 mo).

Phaeobotryon Theiss. & Syd., Ann. Mycol. 13: 664. 1915

Type species. Phaeobotryon cercidis (Cooke) Theiss. & Syd.

Phaeobotryon cercidis (Cooke) Theiss. & Syd., Ann. Mycol. 13: 664. 1915. — Fig. 11

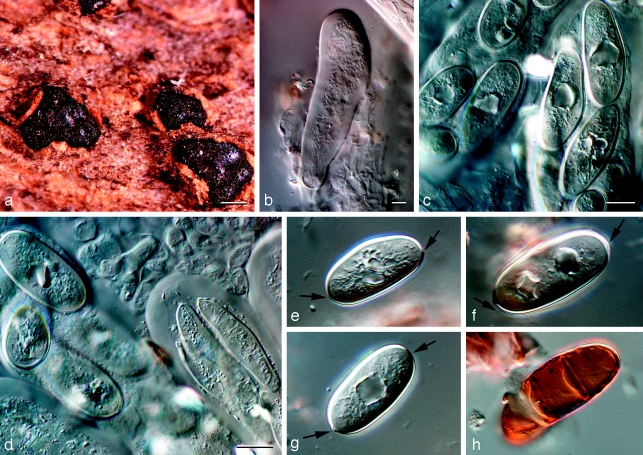

Fig. 11.

Bagnisiella cercidis K 134204. a. Ascomata; b. immature ascus; c. asci with immature ascospores; d. hyaline ascospores; e–g. hyaline, aseptate ascospores with terminal apiculi (arrows); h. broken, brown, 2-septate ascospore. — Scale bars: a = 400 μm; b–h = 10 μm.

Basionym. Dothidea cercidis Cooke, Grevillea 13: 66. 1885, as ‘Dothidea (Bagnisiella)’.

≡ Bagnisiella cercidis (Cooke) Berl. & Voglino, Add. Syll. Fung. 1–4: 223. 1886.

≡ Auerswaldia cercidis (Cooke) Theiss. & Syd., Ann. Mycol. 12: 270. 1914.

Specimen examined. USA, Carolina, on bark of Cercis canadensis, ex Herb. MC Cooke No 795, K134204.

Notes — In the original description of Dothidea cercidis, ascospores were reported as hyaline. However, Theissen & Sydow (1914) observed them to become brown with age, 32–38 × 12–13 μm. Subsequently Theissen & Sydow (1915) introduced the genus Phaeobotryon Theiss. & Syd. to accommodate this species. The asci are clavate, bitunicate, approx. 150–170 × 30–35 μm. The pseudoparaphyses are branched, septate, constricted at septa, anastomosing, 4–5 μm wide. The ascospores are ellipsoidal, initially hyaline, becoming pale brown, turning brown at maturity, 2-septate (cells equal in length), with a characteristic punctiform outgrowth (conical apiculus) at each end of the spore, (27–)30–35(−38) × (8–)12–14(−15) μm. The latter features, namely 2-septate, brown ascospores with a conical apiculus at each end, are considered characteristic for the genus.

Phaeobotryon quercicola (A.J.L. Phillips) Crous & A.J.L. Phillips, comb. nov. — MycoBank MB511711; Fig. 12

Fig. 12.

Phaeobotryon quercicola Fungi Rehnani 534 in G. a. Vertical section through an ascoma; b. immature ascus; c. mature, 2-septate brown ascospores. — Scale bars: a = 100 μm; b, c = 10 μm.

Basionym. Botryosphaeria quercicola A.J.L. Phillips, Mycologia 97: 526. 2005 (based on Otthia quercus Fuckel, Jahrb. Nassauischen Vereins Naturk., 23–24: 170. (1869–1870) 1870.

Notes — As illustrated by Phillips et al. (2005), Phaeobotryon quercicola has brown, 2-septate ascospores with a conical apiculus at each end, thus suggesting that it would be better accommodated in Phaeobotryon than Botryosphaeria.

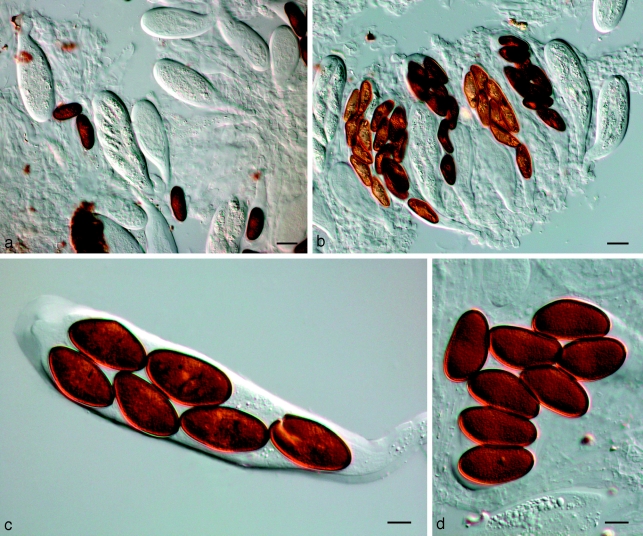

Phaeobotryon mamane Crous & A.J.L. Phillips, sp. nov. — MycoBank MB506581; Fig. 13

Fig. 13.

Phaeobotryon mamane. a–h: CBS H-20109; i–o: CBS 122980. a–c. Asci and ascospores; d–h. ascospores with terminal apiculi (arrows); i. conidiomata forming on pine needle; j–m. conidiogenous cells with developing conidia; n. aseptate and 1-septate conidia; o. 2-septate conidium. — Scale bars: a–h, j–o = 10 μm; i = 350 μm.

Phaeobotryon cercidis similis sed ascosporae majoribus, (30–)37–40(−45) × (11–)13–15(−16) μm.

Anamorph. Dothiorella-like, but with up to two transverse septa.

Etymology. Named for its host, Sophora chrysophylla, which is known as ‘mamane’ in Hawaii.

Ascomata pseudothecial, dark brown to black, stromatic, globose, aggregated in botryose clusters or separate, immersed, becoming erumpent, ostiolate, up to 350 μm diam; wall consisting of 4–6 cell layers of dark brown textura angularis. Pseudoparaphyses hyaline, smooth, multiseptate, with septa 10–23 μm apart, constricted at septa, 3–4 μm wide. Asci bitunicate, 8-spored, stipitate, thick-walled with thick endotunica and well-developed apical chamber, 120–150(−200) × 25–30 μm, with biseriate ascospores. Ascospores ellipsoid to ovate, (30–)37–40(−45) × (11–)13–15(−16) μm, 2-septate, with 3 cells of equal length, not constricted at septa, finely verruculose, widest in middle with conical apiculus at one or both ends. Spermatogonia morphologically similar to conidiomata, also formed in culture. Spermatia hyaline, rod-shaped with rounded ends, 3–5 × 2 μm. Conidiomata pycnidial, ostiolate, separate or aggregated, globose, black, immersed to erumpent, unilocular, up to 350 μm diam; wall consisting of 4–6 layers of brown textura angularis. Conidiogenous cells cylindrical to doliiform, hyaline, smooth, proliferating percurrently near apex, 10–14 × 4–8 μm. Conidia ellipsoid to oblong or subcylindrical or obovoid, brown, smooth to finely verruculose, moderately thick-walled, granular, guttulate, ends rounded, 1(−2)-septate, base with inconspicuous scar, slightly flattened, (30–)35–38(−43) × (12–)14–15(−16) μm.

Specimen examined. Hawaii, Manna Koa Park, Saddle Road, on stems of Sophora chrysophylla, July 2005, W. Gams, holotype CBS H-20109, culture ex-type–CPC 12440 = CBS 122980.

Phaeobotryosphaeria Speg., Ann. Inst. Rech. Agron. 17, 10: 120. 1908.

Type species. Phaeobotryosphaeria yerbae Speg.

Anamorph. Sphaeropsis Sacc., Michelia 2: 105. 1880, nom. cons.

Ascomata pseudothecial, brown to black, unilocular, thick-walled. Pseudoparaphyses hyaline, septate. Asci bitunicate, 8-spored, thick-walled with thick endotunica and well-developed apical chamber. Ascospores brown, aseptate with small apiculus at either end. Conidiomata pycnidial, eustromatic, immersed to erumpent, thick-walled, wall composed of several layers of dark brown textura angularis. Ostiole single, central, papillate. Paraphyses hyaline, aseptate, thin-walled. Conidiogenous cells hyaline, discrete, proliferating internally to form periclinal thickenings. Conidia oval, oblong or clavate, straight, aseptate, moderately thick-walled.

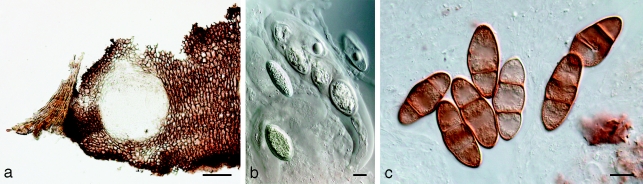

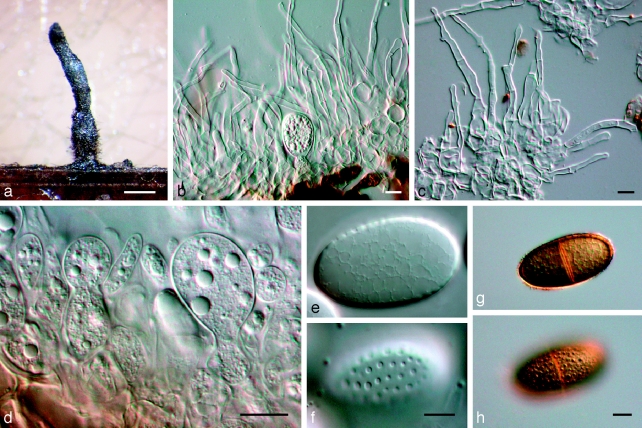

Phaeobotryosphaeria yerbae Speg., Ann. Inst. Rech. Agron. 17, 10: 120. 1908 — Fig. 14

Fig. 14.

Phaeobotryosphaeria yerbae LPS 2926. a. Immature (left) and mature (right) asci; b. mature ascus with brown, aseptate ascospores; c. septate pseudoparaphyses; d. dark brown, aseptate ascospores; e, f. dark brown, aseptate ascospores with apiculi. — Scale bars = 10 μm.

Anamorph. Not reported but presumably a Sphaeropsis species.

Ascomata pseudothecial, brown to black, multiloculate, immersed, becoming erumpent, ostiolate, papillate, up to 500 μm diam, wall composed of several layers of dark brown textura angularis. Pseudoparaphyses hyaline, smooth, 4–6 μm wide, multiseptate, with septa 10–18(−22) μm apart, constricted at septa. Asci bitunicate, clavate, 8-spored, ascospores biseriate in the ascus, stipitate, thick-walled with thick endotunica and well-developed apical chamber, 120–150 × 25–30 μm. Ascospores dark brown when mature, ovoid, (32–)34–42(−48) × (14–)16–18(−20) μm, aseptate, externally smooth, internally finely verruculose, widest in middle with a hyaline apiculus at either end.

Specimen examined. Argentina, Misiones, Campo das Cuias, y San Pedro, on branches of Ilex paraguayensis, Feb. 1907, C. Spegazzini, holotype LPS 2926.

Phaeobotryosphaeria visci (Kalchbr.) A.J.L. Phillips & Crous comb. nov. — MycoBank MB512100; Fig. 15

Fig. 15.

Phaeobotryosphaeria visci. a–f: CWU (MYC) AS 2271; g–l: CBS 122527. a. Immature asci; b. mature ascus with brown, aseptate ascospores; c–f. brown, aseptate ascospores with apiculi (arrows); g. conidioma formed in culture on a pine needle; h, i. conidia forming on conidiogenous cell between paraphyses (arrows); j. developing conidia; k. paraphyses; l. conidia. — Scale bars: a, b = 20 μm; c–f, h–l = 10 μm; g = 50 μm.

Basionym. Dothidea visci Kalchbr., Hedwigia 8: 117. 1869.

≡ Phaeobotryon visci (Kalchbr.) Höhn., Sber. Akad. Wiss. Wien, Math.-naturw. kl., Abt I 128: 591. 1919.

≡ Botryosphaeria visci (Kalchbr.) Arx & E. Müll., Beitr. Kryptogamenfl. Schweiz, Band II, Heft I: 41. 1954.

Anamorph. Sphaeropsis visci (Fr.) Sacc., Michelia 2: 105. 1880.

For synonyms see Sutton (1980).

Ascomata pseudothecial, brown to black, uni- or multiloculate, separate, immersed, ostiolate, up to 500 μm diam, wall composed of several layers of dark brown textura angularis. Pseudoparaphyses hyaline, smooth, 4–6 μm wide, multiseptate, with septa 11–19(−26) μm apart, constricted at septa. Asci bitunicate, 8-spored, ascospores biseriate in the ascus, stipitate, thick-walled with thick endotunica and well-developed apical chamber, 180–230 × 35–50 μm. Ascospores pale-brown when mature, ovoid, (27.5–)31–37.5(−38.5) × (14.5–)15–19(−19.5) μm, aseptate, externally smooth, internally finely verruculose, widest in middle with an apiculus at either end. Conidiomata immersed to erumpent and superficial, unilocular, up to 300 μm wide, wall composed of dark brown textura angularis. Paraphyses hyaline, aseptate, up to 40 μm long and 4 μm wide with a bulbous tip 5 μm diam. Conidiogenous cells hyaline, discrete proliferating internally to form periclinal thickenings, (4–)8.5–11 × 4–6.5 μm. Conidia (27–)29–33(−50) × (14.5–)15.5–19(−22) μm, oval, apex obtuse, base obtuse or truncate, moderately thick-walled, initially hyaline, becoming brown, externally smooth, internally finely verruculose.

Specimens examined. Germany, Klein Ziethen, near Angermünde, on fallen twigs of Viscum album, 22 July 1996, T. Graefenhan, CBS 186.97. – Luxembourg, Weilenbach, near Echternach, on fallen twigs of Viscum album, 14 June 1997, H.A. van der Aa, CBS 100163. – Ukraine, National Nature Park ‘Svjatie Gory’, Donetsk district, on branches of Viscum album, 10 Mar. 2007, Á. Akulov, CWU (MYC) AS 2271, cultures CBS 122526, CBS 122527.

Note — Until now the connection between Phaeobotryosphaeria and its anamorph has not been proven. On the specimen examined here there is a Botryosphaeria-like ascomycete with brown ascospores. Single ascospore isolations from this specimen resulted in cultures of S. visci, thus proving the connection between the two states. Features that distinguish this teleomorph from others with brown ascospores in the Botryosphaeriaceae are the aseptate ascospores with an apiculus at either end.

Phaeobotryosphaeria citrigena A.J.L. Phillips, P.R. Johnst. & Pennycook, sp. nov. — MycoBank MB511714; Fig. 16

Fig. 16.

Phaeobotryosphaeria citrigena. a–g: PDD 89238; h–j: ICMP 16812. a–c. Asci with brown ascospores; d. pseudoparaphyses; e–g. brown, aseptate ascospores with apiculi (arrows); h. conidium developing on a conidiogenous cell; i. hyaline, aseptate conidia; j. conidiomatal paraphyses. — Scale bars: a = 50 μm; b–d = 20 μm; e–j = 10 μm.

Phaeobotryosphaeria visci similis sed ascosporae rufus-brunneae, et conidiae minoribus, (27–)28–33(−34) × (14.5–)15–18.5(−19) μm.

Anamorph. Sphaeropsis sp.

Etymology. Named for its association with Citrus.

Ascomata pseudothecial, brown to black, separate or aggregated, immersed, becoming erumpent, ostiolate, wall composed of several layers of dark brown textura angularis. Pseudoparaphyses hyaline, smooth, 4–6 μm wide, multiseptate, with septa 11–26 μm apart; constricted at septa. Asci bitunicate, 8-spored, stipitate, thick-walled with thick endotunica and well-developed apical chamber, 180–230 × 35–43(−50) μm, with biseriate ascospores. Ascospores reddish brown when mature, ellipsoid to ovoid with both ends rounded, (27.5–)29–37.5(−38.5) × (14.5–)15.5–18(−19.5) μm, with an apiculus at either end, aseptate, externally smooth, internally finely verruculose, widest in middle to upper third. Conidiomata immersed to erumpent and superficial, unilocular, up to 500 μm wide, wall composed of several layers of dark brown textura angularis. Paraphyses hyaline, aseptate, up to 25 μm long and 3–3.5 μm wide. Conidiogenous cells hyaline, discrete, proliferating internally to form periclinal thickenings, 8–11 × 4–6.5 μm. Conidia (27–) 28–33(−34) × (14.5–)15–18.5(−19) μm, oval, apex obtuse, base obtuse or truncate, moderately thick-walled, initially hyaline, becoming brown, externally smooth, internally finely verruculose, aseptate.

Specimens examined. New Zealand, Northland, Kerikeri, Davies Orchard (#2), Inlet Road, on recently dead bark-covered twigs of Citrus sinensis, 6 Sept. 2006, S.R. Pennycook, P.R. Johnston & B.C. Paulus, holotype PDD 89238, culture ex-type ICMP 16812; Northland, Kerikeri, Davies Orchard (#3), Inlet Road, on recently dead bark-covered twigs of Citrus sinensis, 6 Sept. 2006, S.R. Pennycook, P.R. Johnston & B.C. Paulus, PDD 89239, culture ICMP 16818.

Notes — Conidia of P. citrigena remained hyaline for long periods and only rarely did we observe dark conidia. Conidial dimensions of this species are similar to S. visci, but its ascospores are reddish brown in contrast to the pale brown ones of S. visci.

Phaeobotryosphaeria porosa (Van Niekerk & Crous) Crous & A.J.L. Phillips, comb. nov. — MycoBank MB511715; Fig. 17

Fig. 17.

Phaeobotryosphaeria porosa CBS 110496. a. Pycnidium with elongated neck; b. conidium developing between paraphyses; c. paraphyses; d. conidia and conidiogenous cells; e, f. immature conidium at two different levels of focus to show pores in the conidium wall; g, h. mature conidium at two different levels of focus to show verruculose inner surface of the wall. — Scale bars: a = 500 μm, b–h = 10 μm.

Basionym. Diplodia porosum Van Niekerk & Crous, Mycologia 96: 790. 2004.

Specimen examined. South Africa, Western Cape Province, Stellenbosch, on shoots of Vitis vinifera, 2002, J.M. van Niekerk, holotype CBS H-12039, culture ex-type CBS 110496.

Notes — Van Niekerk et al. (2004) did not mention pycnidial paraphyses, but these were clearly seen when these isolates were re-examined (Fig. 17). This species is unique within the Botryosphaeriaceae because of its large, thick-walled conidia with large pores (1 μm wide) that are clearly visible by light microscopy. However, the pitted walls, although unique and distinctive, should be regarded as informative at the species level in the same way that this character was regarded in the original description.

Spencermartinsia A.J.L. Phillips, A. Alves & Crous, gen. nov. — MycoBank MB511762.

Ascomata pseudothecia, ostiolati. Asci bitunicati, octo-spori, clavati, stipitati, pseudoparaphysibus multis filiformibus, septatis, latis interspersi. Ascosporae biseriati, uniseptati cum terminali apiculi. Conidiomata stromatiformia. Cellulae conidiogenae holoblasticase, proliferatione percurrenti, ut videtur annellationibus, vel inplano eodem periclinaliter incrassate. Conidia brunnea, uniseptata.

Type species. Spencermartinsia viticola (A.J.L. Phillips & J. Luque) A.J.L. Phillips, A. Alves & Crous.

Etymology. Named in honour of Prof. dr Isabel Spencer-Martins, founder of the Centro de Recursos Microbiológicos in Portugal.

Ascomata pseudothecial, ostiolate. Pseudoparaphyses thin-walled, hyaline, septate, constricted at septa. Asci bitunicate, 8-spored, clavate, stipitate, developing amongst thin-walled, septate pseudoparaphyses, with biseriate ascospores. Ascospores hyaline when young, brown when mature, uniseptate with an apiculus at each end. Conidiomata stromatic. Conidiogenous cells lining inner surface of conidiomata, holoblastic, proliferating internally producing periclinal thickenings, or pro-liferating percurrently to form annellations. Conidia brown, 1-septate.

Note — Spencermartinsia differs from Dothiorella in having 2-celled ascospores with an apiculus at either end of the ascospores.

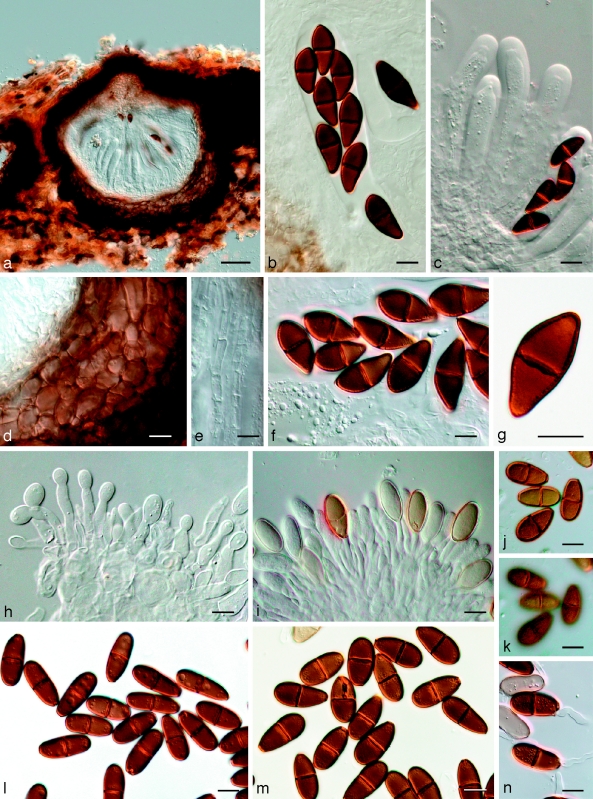

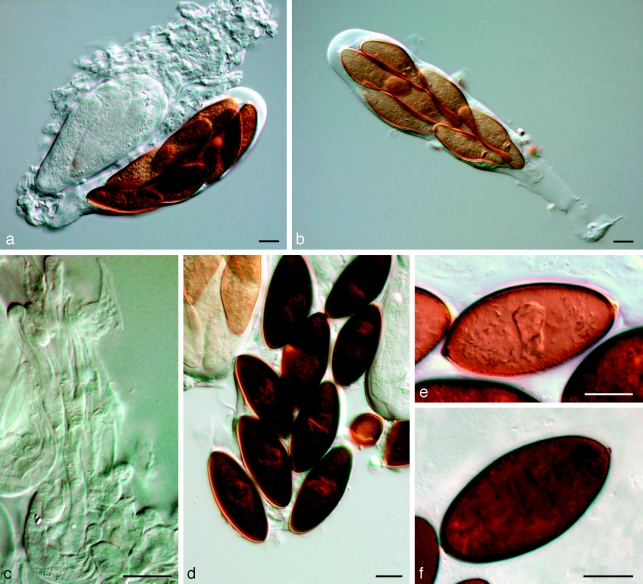

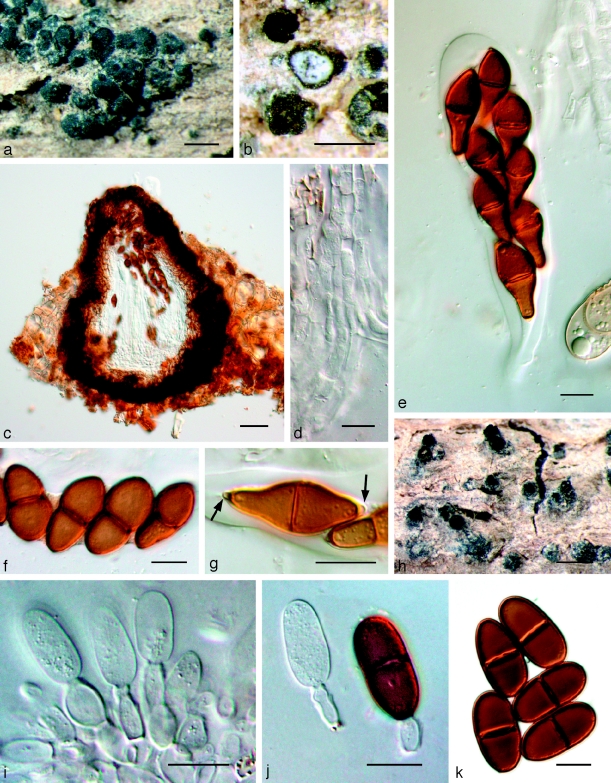

Spencermartinsia viticola (A.J.L. Phillips & J. Luque) A.J.L. Phillips, A. Alves & Crous, comb. nov. — MycoBank MB511763; Fig. 18

Fig. 18.

Spencermartinsia viticola. a–h: LISE95177; i–k: CBS 117009. a. Ascomata erumpent through host bark; b. ascoma cut through horizontally showing the white contents with dark spots corresponding to asci with ascospores; c. vertical section through an ascoma; d. septate pseudoparaphyses; e. clavate ascus containing eight biseriate, dark brown, 1-septate ascospores; f. ascospores; g. ascospores with small rounded apiculi (arrows); h. conidiomata partially erumpent through the host bark; i. conidiogenous cells; j. conidiogenous cells with annellations. The cell on the right has a dark brown, 1-septate conidium attached; k. conidia. — Scale bars: a, h = 500 μm; b = 250 μm; c = 50 μm; d–g, i–k = 10 μm.

Basionym. Botryosphaeria viticola A.J.L. Phillips & J. Luque, Mycologia 97: 1116. (2005) 2006.

Anamorph. Dothiorella viticola A.J.L. Phillips & J. Luque, Mycologia 97: 1116. (2005) 2006.

Specimens examined. Spain, Catalonia, Vimbodí, near the Monastery of Poblet, on pruned canes of Vitis vinifera cv. Garnatxa Negra, 12 Aug. 2004, J. Luque & S. Martos, holotype LISE 95177, culture ex-type CBS 117009; ditto, 28 May 2003, J. Luque & Mateu, LISE 95178, culture CBS 117006.

Notes — The ex-type isolate of Spencermartinsia viticola (CBS 117009) clustered with an isolate previously identified as Diplodia spegazziniana (CBS 302.75). The latter isolate is misidentified and is not representative of this species. An additional isolate originally identified by Luque et al. (2005) as B. viticola (CBS 117006), exhibited some differences in culture morphology from the ex-type strain and other strains (Luque et al. 2005). For example, the reverse side of cultures of CBS 117006 became red-brown after 3–5 d on PDA at 25 °C with a progressive darkening of the pigment after 6–10 d. Furthermore, there were some differences in ITS and EF1-α sequences between CBS 117006 and CBS 117009 (one substitution and one deletion in ITS and nine substitutions in EF1-α). Although these morphological and phylogenetic differences may reflect species differences, no name was applied to CBS 117006 because only one isolate was available for study.

Also contained within Spencermartinsia was a single isolate of ‘Diplodia’ medicaginis (CBS 500.72), which formed a unique clade. Again, only a single isolate was available, the name of which is unresolved. Isolates ICMP 16827 and ICMP 16828 from Citrus sinensis in New Zealand formed another subclade, and thus would be regarded as a distinct phylogenetic species. However, neither of the isolates could be induced to sporulate, and no morphological data are available. Therefore, no names will be applied until their morphology can be determined.

Isolates ICMP 16819 and ICMP 16824, also from Citrus sinensis in New Zealand, formed a sister clade to Spencermartinsia that was supported by a high MP bootstrap value (100 %). Neither of these two isolates has been induced to sporulate. In view of the lack of morphological data, the status of these two isolates remains uncertain.

DISCUSSION

In this paper the phylogenetic position and taxonomy of species of Botryosphaeriaceae with brown ascospores were studied. The taxonomic position of Dothidotthia was resolved, and within the Botryosphaeriaceae we recognise a number of genera with brown ascospores. For some of these genera we reinstate old names, while others are described as new. In keeping with the proposal to use a single name for pleomorphic fungi (Rossman & Samuels 2005) we propose a single generic name for each clade. For example, since Dothidotthia was shown to fall in the Pleosporales, this name is no longer available for the teleomorph of Dothiorella, and therefore we propose that the anamorph genus name, Dothiorella, be used for both the anamorph and the teleomorph of this clade.

Within the Botryosphaeriaceae, species with brown ascospores are found in three separate lineages, which lead to at least six genera. These lineages are dispersed randomly in different branches of the phylogenetic tree. Considering that brown ascospores are a common feature in other families in the Dothideomycetes (von Arx & Müller 1954, 1975), it is possible that this character has been retained in these lineages from the ancestors of the family, rather than being a character that has evolved at different times.

Other morphological features that were used to differentiate genera were the presence or absence of apiculi on ascospores, septation of ascospores, striations on conidia, and the presence or absence of paraphyses in conidiomata. It is interesting to note that striations are strongly developed in Lasiodiplodia, weaker in Neodeightonia and absent from Diplodia. Furthermore, conidiomatal paraphyses are found in Lasiodiplodia but are absent from Neodeightonia and Diplodia.

Two of the lineages with brown ascospores lie within a clade that was previously regarded to contain species with Lasiodiplodia and Diplodia anamorphs (Crous et al. 2006). In their phylogenetic study (Crous et al. 2006), based on LSU sequences, this clade could not be resolved. In the present study it could be resolved only by combining sequences of two protein coding genes with sequences of three ribosomal genes. In this way this clade was resolved into six genera, four of which have dark ascospores.

One lineage (clade 2, Fig. 2) clustered between Diplodia and Lasiodiplodia. The name Neodeightonia already exists for this genus and it is reinstated in this paper. This genus was introduced by Booth (in Punithalingam 1969) for a single species, namely N. subglobosa. Von Arx & Müller (1975) transferred this species to Botryosphaeria within their broad concept of the genus. When Crous et al. (2006) reassessed Botryosphaeria, reducing it to B. corticis and B. dothidea, their isolate of B. subglobosa resided in an unresolved clade consisting of Diplodia, Lasiodiplodia and Tiarosporella. From the data presented here it is clear that Neodeightonia subglobosa, type of Neodeightonia, is phylogenetically and morphologically distinct from other genera in the Botryosphaeriaceae. Diplodia phoenicum was shown to be another species in this genus. Rather than introduce a new anamorph genus to accommodate Diplodia phoenicum we followed the procedures suggested by Rossman & Samuels (2005) and used the teleomorph genus name for this species. Conidia of both N. subglobosa and N. phoenicum have striations on the conidial wall similar to those seen in Lasiodiplodia, albeit somewhat less distinct. However, anamorphs of Neodeightonia do not have paraphyses, which are typical of Lasiodiplodia, and the striate conidial wall distinguishes Neodeightonia from Diplodia.

A second lineage, basal to Diplodia, Lasiodiplodia and Neodeightonia, was resolved into three clades (clades 4–6) that could be distinguished from one another on the morphology of the teleomorphs, especially septation of the ascospores and the presence or absence of ascospore apiculi. These genera can also be differentiated on morphology of the anamorphs. Phaeobotryon is available for one of these clades, Phaeobotryosphaeria for another, but as far as we could tell, no suitable names are available for the third one, and Barriopsis is introduced to accommodate Physalospora fusca, which has aseptate ascospores without apiculi. Von Arx & Müller (1954, 1975) placed Phaeobotryon in synonymy with Botryosphaeria. However, as determined here, Phaeobotryon is morphologically and phylogenetically distinct from all the other genera we studied. For this reason we have reinstated the generic name Phaeobotryon for isolate CBS 122980, and for other isolates in the same clade. The 1–2-septate ascospores of these fungi with an apiculus at either end correspond with Bagnisiella cercidis K134204, which is the basionym of Phaeobotryon cercidis and type species of the genus Phaeobotryon. Ascospores of the isolates from Sophora chrysophylla are larger than P. cercidis and for this reason these isolates were described as a new species. Although Von Arx & Müller (1954) considered Phaeobotryosphaeria a synonym of Botryosphaeria, in this study we show that it is morphologically and phylogenetically distinct from the other two genera in this clade and the name is reinstated for species with brown, aseptate ascospores with terminal apiculi.

The anamorph of Phaeobotryosphaeria was shown to correspond to Sphaeropsis. Although we have adopted to follow the system of one name for one genus, it is important to clarify some of the controversy surrounding the genus Sphaeropsis. This genus has been the subject of considerable debate, much of which has revolved around the question of a suitable genus name for the pine pathogen sometimes referred to as Sphaeropsis sapinea. The main point of debate has been whether this species should revert to its older name of Diplodia pinea or whether it should remain in Sphaeropsis. From the literature it seems that this species has been regarded as typical of the genus Sphaeropsis, both morphologically and phylogenetically. For example, the phylogenetic studies of Jacobs & Rehner (1998) and Denman et al. (2000) placed Sphaeropsis sapinea in the Diplodia clade, which prompted Denman et al. (2000) to suggest that Sphaeropsis is a synonym of Diplodia. This decision was also supported by subsequent studies (Zhou & Stanosz 2001, Alves et al. 2004). When Sutton (1980) stated that percurrently proliferating conidiogenous cells are a feature of Sphaeropsis that are not found in Diplodia it is not clear if he was referring to S. visci or S. pinea. Nevertheless, Denman et al. (2000) referred to percurrent proliferations in Diplodia, further confirming their suggestion that Sphaeropsis is a synonym of Diplodia. Phillips (2002) and Alves et al. (2004) confirmed that this type of conidiogenesis occurs in Diplodia mutila. However, it is important to point out that when Saccardo (1880) established Sphaeropsis for species of Diplodia with dark conidia, he cited S. visci as the type species. We examined a number of strains isolated from Viscum album that correlate in all ways with the original description of S. visci and could find only internal proliferation of the conidiogenous cells, resulting in periclinal thickenings and typical phialides (sensu Sutton 1980). Moreover, this was the only type of conidiogenesis that we could detect in the other species that we consider to belong in Sphaeropsis (D. porosum and S. citrigena). As we illustrate here, the anamorphs of Sphaeropsis are morphologically (pycnidial paraphyses) and phylogenetically distinct from Diplodia. Thus, as revealed by the phylogeny presented here, Sphaeropsis, typified by S. visci, is a valid and distinct genus. Moreover, the pine pathogen often referred to as S. sapinea resides in Diplodia.

The other species in Phaeobotryosphaeria deserve some mention. Phaeobotryosphaeria porosa is distinct in the large pits in the conidial wall. When this species was described from grapevines in South Africa (van Niekerk et al. 2004) it was placed in Diplodia, although the authors suggested that its unique conidial morphology might necessitate a new genus. At that time Sphaeropsis was not clearly defined and indeed had been suggested as being a synonym of Diplodia. Despite the unique character of conidial pits, D. porosum has features that place it within the morphological concept of Phaeobotryosphaeria. These features include relatively large, thick-walled conidia, phialidic conidiogenous cells with periclinal thickenings, and pycnidial paraphyses. Phylogenetically (Fig. 2) it also falls within Phaeobotryosphaeria. Thus, it seems that conidial pits are of taxonomic significance at species level only, in the same way as they were regarded when this species was first described by van Niekerk et al. (2004). Finally, a third species is described in Phaeobotryosphaeria, namely P. citrigena from dead citrus twigs in New Zealand.

The third lineage (clades 8–10) is sister to Neofusicoccum, and the name Dothiorella has been used for the anamorphs of these species. This lineage was resolved into at least two, possibly three genera. Clades 8 and 9 could be distinguished from one another on the morphology of their ascospores. No teleomorph is yet known for clade 10. Dothiorella is already available for clade 8, and a new genus Spencermartinsia is introduced for clade 9. Dothiorella is based on D. pyrenophora, but no cultures are available for this species. When Phillips et al. (2005) reinstated Dothiorella, they determined that D. sarmentorum corresponded in all ways with the concept for this genus.

A clade sister to Dothiorella was composed of two subclades (clades 9 and 10). It is not entirely clear if these two clades represent two genera or a single genus. Spencermartinsia viticola was considered to be a species of Dothiorella by Luque et al. (2005), who pointed out that some morphological aspects of the anamorph (colony morphology) differentiated this species from others in Dothiorella. A more detailed examination of this species revealed that the ascospores bear an apiculus at either end. This feature, together with the phylogenetic difference indicates that this clade represents another genus closely related to Dothiorella, and for which we introduce the name Spencermartinsia. The distinct apiculi differentiate this genus from Dothiorella, and for this reason we propose it as a new genus. This clade (9) is phylogenetically diverse and appears to be composed of several species. The type species (S. viticola) is represented in Fig. 2 by the ex-type culture of Do. viticola (CBS 1187009). Another isolate with this name (CBS 117006) resides in a separate clade, and thus probably represents another species. Since we have only a single example of this species we decline at this stage to apply a species name to it. Similarly, CBS 500.72 (D. medicaginis) is another distinct species represented by a single isolate, which we also decline to name. The two isolates from Citrus (ICMP 16827 and ICMP 16828) did not sporulate in culture during the course of this work and thus cannot be fully characterised. Nevertheless, they too represent a third species in Spencermartinsia. The conidia from which these isolates were grown match closely those illustrated by Gure et al. (2005) from an isolate from Podocarpus falcatus seeds, which these authors referred to Dothiorella. We are continuing to study these isolates with the aim of applying species epithets.