Abstract

Melanised fungi were isolated from rock surfaces in the Central Mountain System of Spain. Two hundred sixty six isolates were recovered from four geologically and topographically distinct sites. Microsatellite-primed PCR techniques were used to group isolates into genotypes assumed to represent species. One hundred and sixty three genotypes were characterised from the four sites. Only five genotypes were common to two or more sites. Morphological and molecular data were used to characterise and identify representative strains, but morphology rarely provided a definitive identification due to the scarce differentiation of the fungal structures or the apparent novelty of the isolates. Vegetative states of fungi prevailed in culture and in many cases could not be reliably distinguished without sequence data. Morphological characters that were widespread among the isolates included scarce micronematous conidial states, endoconidia, mycelia with dark olive-green or black hyphae, and mycelia with torulose, isodiametric or moniliform hyphae whose cells develop one or more transverse and/or oblique septa. In many of the strains, mature hyphae disarticulated, suggesting asexual reproduction by a thallic micronematous conidiogenesis or by simple fragmentation. Sequencing of the internal transcribed spacers (ITS1, ITS2) and 5.8S rDNA gene were employed to investigate the phylogenetic affinities of the isolates. According to ITS sequence alignments, the majority of the isolates could be grouped among four main orders of Pezizomycotina: Pleosporales, Dothideales, Capnodiales, and Chaetothyriales. Ubiquitous known soil and epiphytic fungi species were generally absent from the rock surfaces. In part, the mycota of the rock surfaces shared similar elements with melanised fungi from plant surfaces and fungi described from rock formations in Europe and Antarctica. The possibility that some of the fungi were lichen mycobionts or lichen parasites could not be ruled out.

Keywords: biodiversity, black fungi, Capnodiales, Chaetothyriales, Dothideomycetes, extremotolerance

INTRODUCTION

Rock substrata have been explored and analysed with increased microbiological attention because of their extreme variations in environmental factors that select strongly for colonisation by stress-tolerant fungi (Staley et al. 1982, Urzí et al. 1993, Sterflinger & Krumbein 1995, Wollenzien et al. 1995, Sterflinger & Krumbein 1997, Sterflinger 2000, Sterflinger & Prillinger 2001, Bogomolova & Minter 2003, de Leo et al. 2003). Rock surfaces have been recognised as a reservoir for highly melanised, slow-growing filamentous and yeast-like fungi of ascomycetous affinities. Darkly pigmented fungi from geological materials have been named by a variety of terms, e.g., black fungi, black yeasts, or microcolonial fungi (Staley et al. 1982), in reference to their prominent shared morphological characteristics.

The interests in melanised fungi are multiple and varied. From a clinical point of view, the anamorphs of Capronia (Herpotrichiellaceae), and many species belonging to the Exophiala-Ramichloridium-Rhinocladiella-Cladophialophora complex, constitute a group of medically significant opportunists (de Hoog et al. 1994, 1998, 2000b). Another recent trend has been to focus on these organisms as a model for astrobiological studies of eukaryotes (Gorbushina 2003). Finally, the life histories of melanised fungi from rock surfaces may intersect with other saprobic, lichenicolous, epiphytic or even phytopathogenic fungi (Untereiner & Malloch 1999, Crous et al. 2000, 2007a).

Observations of novel melanised fungi from man-made rock surfaces in arid and semi-arid regions, especially those of the Mediterranean basin, led us to test whether these fungi were a widespread component of natural rock surfaces. If such fungi were present, are they abundant and taxonomically distinct? Alternatively, rock surfaces may be primarily colonised by fungi deposited from soils, the phyllosphere, or from nascent lichen mycobionts. These questions were important for determining whether rock surfaces could harbour organisms producing secondary metabolites of relevance for the pharmaceutical industry. The fungi associated with rock surfaces present a series of characteristics that makes them a potentially attractive group for a microbial screening programme, e.g., their apparently ubiquitous habitats, their relative ease of collecting and cultivation in culture, and the fact that at least some species are related to other ascomycetous fungi known to possess multiple secondary metabolite biosynthetic pathways (Kroken et al. 2003). Dark pigmentation of the strains indicates that secondary metabolite biosynthetic pathways, e.g., those involved in melanogenesis, are operational.

Fungi isolated from rocks share macro- and micromorphological characteristics, but their phylogenetic origins appear to be diverse (Sterflinger et al. 1999). A previous study demonstrated that limestone from Mallorca was colonised by a diverse and complex assemblage of Pezizomycotina, with many representatives among the classes Dothideomycetes and Chaetothyriomycetes (Ruibal et al. 2005). However, many more of the fungi belonged to undetermined orders and families, or corresponded poorly to known families of Pezizomycotina.

In order to confirm and expand our preliminary results (Ruibal et al. 2005), we analysed the number and kinds of melanised fungi associated with the surfaces of four different types of rock in the Central Mountain System of Spain. Our first step was to explore practical methods of providing large numbers of unique fungal isolates for use in natural products discovery and to measure the biodiversity of the fungal community in order to understand the logistics of handling large numbers of fungal strains. We enumerated the different melanised fungi that were recovered from granite, black slate, limestone, and quartzite formations using a combined macromorphology and microsatellite-primed PCR technique to select unique strains, grouping isolates into genotypes assumed to represent species. A preliminary evaluation of their phylogenetic diversity based on ITS1-5.8S-ITS2 rDNA sequences is presented. Phylogenetic relationships among the isolates and possible novel groups were explored by constructing a general sequence-based framework with known genera of similar fungi. The phylogenetic framework was correlated with cultural features, attempting to recognise morphologically defined genera and species.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Study area, environmental and geological features

The Spanish Central System is an intraplate mountain range located in the central part of the Iberian Peninsula and consists, for the most part, of plutonic and metamorphic rocks belonging to the Hercynian basement and a locally preserved thin cover of Upper Cretaceous sedimentary rocks. Therefore, the area is lithologically and structurally complex and comprises a number of formations such as the Sierras of Guadarrama, Somosierra and Ayllón (García & Aparicio 1987).

The four sites were located in the province of Madrid, within an area of c. 200 km2, with distances between sites from 8 to 20 km. The zone receives c. 600–700 mm rainfall distributed irregularly during the year. Two main seasons predominate, a dry and hot summer, with temperatures fluctuating between 40 and 5 °C, and a more humid and cold winter, with temperatures ranging between 15 and -10 °C. The number of sunny days averages about 240/yr.

La Cabrera study site (40°52′30″N, 3°38′W) (Fig. 1) was located near the village of the same name, at c. 1600 m above sea level (asl). It is a pure granite formation of Plutonic origin, comprised of mixed fine to middle grained leucogranites of hernycic age (Bellido Mulas & Rodríguez Fernández 1991). The scarce vegetation consisted mostly of shrubs (dominated by Cistus ladanifer) and pasture. The site was sampled in August 2001. The Atazar site (40°57′N, 3°25′W), sampled in October 2001, was located c. 7 km northeast of the village of the same name, at c. 1300 m asl. The zone consisted of metamorphic, black slate from the Silurian period (Pérez González & Portero 1990).

Fig. 1.

General view of La Cabrera study site.

The vegetation was sparse, consisting of shrubs (dominated by Cistus species) and pasture. The Patones site (40°53′N, 3°27′W) was located c. 5 km to the east of the village of the same name along the road M-102, at c. 800 m asl, on a ridge crest that delimits the valley of the Jarama River. The area was at the southern border of the Central Mountain System and was formed of cretaceous limestone and dolomites (Pérez González & Portero 1990). The site was sampled in May 2003. The vegetation was chaparral-like and dominated by Quercus ilex, Retama sphaerocarpa, and Juniperus oxycedrus. The Puebla de la Sierra site (41°4′N, 3°29′W), sampled in October 2003, was located c. 2 km on the trail towards La Peña de Cabra at km 9 of the road M-130, between the villages of Prádena del Rincón and Puebla de la Sierra at an elevation of c. 1700 m asl. The zone was formed mainly of quartzite, with mixed small quantities of sandstone and conglomerates, from the Ordovician period (García & Aparicio 1987). The site was the only one that was tree-covered, mainly with planted Scots pine (Pinus sylvestris) and Spanish fir (Abies pinsapo).

Isolation of fungi from rock surfaces

Sample selection was determined by locating a clean and easily collectible sample. Rock samples were taken from clean, vertical, lichen-free surfaces. At each site, 2–5 rock faces separated by 20–200 m and in different orientations were sampled. A cold chisel was inserted into an existing crack, and the pieces of superficial rock were chipped off the surface with a hammer. Rock fragments were packed in sterile, clean paper bags and transported to the laboratory at ambient temperature. Samples were processed for isolation within 1 wk.

The rock surfaces were rinsed with 96 % ethanol and allowed to dry to reduce the influence of dust and airborne spores. Samples for isolation plates were prepared by chipping or scraping surfaces with a sterile knife and chisel blade to remove small superficial fragments from 10–20 cm2 area from the outer layer of the field-collected rock. Penetration into the rock was c. 0.5–3 mm, depending on the rock texture. The fragments were further pulverised in a sterile mortar. About 2–3 cm3 of pulverised rock were added to a sterile 50 mL centrifuge tube and washed once with a weak sterile detergent solution (aqueous Tween 20, Sigma -Aldrich, Inc., St. Louis, MO, USA), followed by five washes, three with distilled water and two more with sterile water. Washed samples were resuspended in 40 mL of sterile water and aliquots were spread homogenously onto isolation media plates. For each rock sample, aliquots of 500, 300, 200, 100, and 50 μL, were spread onto three plates of each of dichloran-rose bengal agar base (DRBC) (Oxoid Ltd., Basingstoke, Hampshire, GB); and dichloran-glycerol agar base (DG18) (Oxoid Ltd.). Media were supplemented with streptomycin sulfate and terramycin (50 μg/mL) to suppress bacterial growth.

Plates were incubated for 2–3 wk with 12 h fluorescent light at 22 °C. Within a few days of the first appearance of colonies on the plates, all colonies that had dark hyphae were isolated, while faster-growing hyaline mycelia were eliminated by dissection. Continual removal of rapidly extending unpigmented colonies permitted more time and space for development of slower growing pigmented colonies. Plates were examined for up to 1 mo until no more new colonies appeared.

Strain characterisation

The darkly pigmented isolates obtained from isolation plates were grown in duplicate on potato-dextrose agar (PDA, Difco Laboratories) plates at 22 °C for 2 wk. Grouping the isolates into gross morphological types by colony colour, texture, margin type, and radial extension was attempted. However, the crude grouping was inadequate to discriminate numbers of different species. To recognise numbers of unique genotypes and which isolates were genotypically identical, we used a microsatellite-primed PCR (MP-PCR) fingerprinting technique (Longato & Bonfante 1997). Band patterns of PCR products in agarose gels were used to group isolates. The groupings based on MP-PCR were further corroborated by the macroscopic morphology of isolates in PDA plates.

Once the isolates were grouped into genotypes, at least one representative member of each group was processed and analysed. Our underlying assumption was that this isolate was representative of a single species and that the rest of the isolates of the group were the same species, although it was recognised that genetically distinct individuals of the same population could belong to the same species. At least one, and sometimes more than one, isolate of each group were preserved when morphological deviants were observed, or when multiple strains were sequenced. Isolates (Table 1) were frozen as vegetative mycelia in 10 % glycerol at −80 °C at Merck Sharp & Dohme de España, S.A.

Table 1.

Numbers of melanised fungal isolates and genotypes isolated, sequenced and preserved from four stone formations in the Central Mountain System.

| Sampling sites | Isolates | Rock type | Genotypes | Isolates ITS sequenced | Preserved representative isolates |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| La Cabrera | 69 | Granite | 33 | 39 | 63 |

| Atazar | 85 | Slate | 57 | 57 | 81 |

| Patones | 47 | Limestone | 34 | 35 | 41 |

| Puebla de la Sierra | 65 | Quartzite | 39 | 40 | 57 |

| Totals | 266 | 163 | 171 | 242 |

The representative isolates were cultured in triplicate in five different media to study their macro- and microscopic characters and to attempt identification. The set of media included: potato-carrot agar (PCA) (Gams et al. 2007), malt extract agar (MEA, Difco Laboratories), Czapek-Dox agar (CZA, Difco Laboratories), oatmeal agar (OA, Difco Laboratories), and water agar supplemented with 0.2 % yeast extract (AI, Difco Laboratories). Colony diameter, texture, pigmentation, margin appearance, exudates, and colours in the descriptions were recorded after 2 wk at 22 °C.

Microscopic features were evaluated by 1) observing hyphae and other structures mounted in 5 % KOH; 2) growing fungal colonies on cover glasses immersed in cornmeal agar (Difco Laboratories) and malt agar (0.5 % malt extract, 1.5 % agar) and supported on 2 % water agar. Three-week-old colonies on cover glasses were fixed in 95 % ethanol, mounted in cotton blue-lactophenol, and photographed.

DNA extraction, PCR amplification, and DNA sequencing

DNA extraction was performed following previously described methods (Peláez et al. 1996). The MP-PCR was performed using (GTG)5 primer (Longato & Bonfante 1997). Reactions (25 μL) were carried out in the following conditions: 0.2 mM of each dNTPs (geneAmp dNTPs Perkin Elmer, Norwalk, CT, USA), primer at a final concentration of 0.4 μM, 5 μL of fungal DNA solution (1/100 dilution of the extraction solution with a concentration between 0.1 and 0.01 μg/mL) and 0.2 U of Taq polymerase (QBiogene, Inc., Carlsbad, CA, USA) in a reaction buffer. The steps of the PCR reactions were: 40 cycles of 30 s at 95 °C, 30 s at 53 °C and 2 min at 72 °C and the process was completed with a final step of 10 min at 72 °C for the polymerisation of incomplete fragments. Reactions were performed following manufacturer’s recommendations. The amplification products were checked for appropriate size by electrophoresis in 1.2 % agarose gels (Hispanlab, S.A., Alcobendas, Madrid, Spain) in a Pharmacia LKB-GPS 200 electrophoresis apparatus at 120 V (Amersham Biosciences Ltd., Buckinghamshire, UK).

To analyse and compare the band patterns from MP-PCR, fragments were separated electrophoretically in prefabricated polyacrylamide (12.5 %) gels (GeneCel Excel 12.5/24 Kit, Amersham Biosciences Ltd.) in a GenePhor unit (Amersham Biosciences Ltd.) at 600 V and visualised by silver staining (PLUS ONE DNA Silver Staining Kit, 17-6000-36, Amersham Biosciences Ltd.) following the manufacturer’s procedures. Gel band patterns were scanned and used to produce phenetic groupings with Gel Compar 4.1 software package (Applied Biomaths). The combined data of all fingerprints for each isolate were compared in a pairwise manner using Jaccard’s index (Sneath & Sokal 1973) to generate a matrix of similarities. A dendrogram showing the relative similarity among the different isolates was calculated by UPGMA (Sneath & Sokal 1973). Isolates with 97 % or greater homology were considered to be the same genotype.

The ITS1-5.8S-ITS2 fragment of the isolates was amplified with the following primers: ITS1F (Gardes & Bruns 1993), ITS4A (Larena et al. 1999), ITS5 and ITS2 (White et al. 1990), NL1R (reverse of NL1) (O’Donnell 1993), 18S-1 (Platas et al. 2004), ITS1-3: 5′-AGTTCAGCGGGTAGTCC-3′ (designed in the laboratory) and 18S-3: 5′-GATGCCCTTAGATGTTCTGGGG-3′ (designed in-house). The specific primers applied for amplification of each isolate are listed in Table 2. Some additional sequencing of the rDNA region containing the initial sequence of the 18S rDNA gene of some of the isolates was attempted to correlate isolates with previous studies (Ruibal et al. 2005). The amplifications were performed using primers NS1 and NS2 (White et al. 1990).

Table 2.

Melanised fungal isolates from rock of the Central Mountain System. Origin, primers used in the amplification of the ITS region1 and GenBank accession numbers of the sequences obtained.

| Strain(s) | Site (sample no.) | N° of isolates | ITS region primers | ITS region accession2 | Identification |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| TRN1 | La Cabrera (1) | 1 | ITS1F/ITS1-3 | AY843039 | Sterile, ‘Sarcinomyces petricola’ clade, Chaetothyriales |

| TRN3, TRN31 | La Cabrera (1) | 2 | ITS5/ITS4A | AY843040, AY616206 | Hormonema carpetanum, Dothideales (core), Dothideales |

| TRN4 | La Cabrera (3) | 1 | ITS5/ITS4A | AY843041 | Phaeococcomyces catenatus, Sacinomyces petricola clade, Chaetothyriales |

| TRN5 | La Cabrera (2) | 1 | ITS5/ITS4A | AY843042 | Sterile, Mycosphaerellaceae |

| TRN6 | La Cabrera (1) | 3 | ITS1F/ITS1-3 | AY843043 | Torula-like, Sacinomyces petricola clade, Chaetothyriales |

| TRN7 | La Cabrera (1) | 1 | ITS1F/ITS1-3 | AY843044 | Torula-like, Sacinomyces petricola clade, Chaetothyriales |

| TRN9 | La Cabrera (1) | 1 | ITS1F/ITS1-3 | AY843045 | ‘Stigmina’ sp., Dothideales (core), Dothideales |

| TRN13v | La Cabrera (1) | 1 | ITS5/ITS4A | AY843048 | Sterile, Mycosphaerellaceae |

| TRN14 | La Cabrera (4) | 1 | ITS1F/ITS4 | AY843049 | Exophiala sp., Capronia clade, Chaetothyriales |

| TRN24, TRN40 | La Cabrera (1) | 2 | ITS5/ITS4A | AY616202, AY616201 | Hormonema carpetanum, Dothideales (core), Dothideales |

| TRN25 | La Cabrera (1) | 5 | ITS5/ITS4A | AY616205 | Hormonema carpetanum, Dothideales (core), Dothideales |

| TRN30 | La Cabrera (2) | 1 | ITS5/ITS4A | AY843051 | Exophiala sp., Capronia clade, Chaetothyriales |

| TRN35 | La Cabrera (2) | 1 | ITS5/ITS4A | AY843052 | Sterile, ‘Sarcinomyces petricola’ clade, Chaetothyriales |

| TRN37 | La Cabrera (1) | 3 | ITS5/ITS4A | AY843054 | Aureobasidium pullulans, Dothideales (core), Dothideales |

| TRN41 | La Cabrera (1) | 1 | ITS5/ITS4A | AY843055 | Sterile, ‘Cryomyces’ group |

| TRN42 | La Cabrera (1) | 1 | ITS1F/ITS1-3 | AY843056 | Fusicladium-like, Mycosphaerella clade, Mycosphaerellaceae |

| TRN43 | La Cabrera (1) | 1 | ITS5/ITS4A | AY843057 | Fusicladium-like, Mycosphaerella clade, Mycosphaerellaceae |

| TRN44 | La Cabrera (1) | 1 | ITS5/ITS4A | AY843058 | Sterile, Mycosphaerella clade, Mycosphaerellaceae |

| TRN45 | La Cabrera (3) | 1 | ITS1F/ITS1-3 | AY843059 | Lecythophora sp., ‘Cryomyces’ group |

| TRN47 | La Cabrera (1) | 2 | ITS5/ITS4A | AY843060 | Pleosporales |

| TRN49 | La Cabrera (1) | 1 | ITS5/ITS4A | AY843061 | Pleosporales |

| TRN50, TRN15 | La Cabrera (1) | 18 | ITS5/ITS4A, ITS1F/ITS1-3 | AY843062, AY843050 | Hormonema sp., Dothideales (core), Dothideales |

| TRN157 | La Cabrera (1) | 1 | ITS5/ITS4A | AY843064 | Fusicladium-like, Teratosphaeriaceae clade, Capnodiales |

| TRN158 | La Cabrera (1) | 1 | ITS5/ITS4A | AY843065 | Cladophialophora sp., unknown zone 3, Chaetothyriales |

| TRN159 | La Cabrera (1) | 1 | ITS5/ITS4A | AY843066 | Sterile, Mycosphaerellaceae |

| TRN162 | La Cabrera (1) | 1 | ITS5/ITS4A | AY843068 | Exophiala sp.? |

| TRN165, TRN11, TRN13n | La Cabrera (1) | 3 | ITS5/ITS4A, ITS1F/NL1R (TRN13n) | AY843069, AY843046, AY843047 | Sterile, Dothideales (core), Dothideales |

| TRN170, TRN172 | La Cabrera (3) | 2 | ITS5/ITS4A | AY843070, AY843071 | Sclerococcum sp., ‘Cryomyces’ group |

| TRN173 | La Cabrera (1) | 1 | ITS5/ITS4A | AY843072 | Sterile, Mycosphaerellaceae |

| TRN174 | La Cabrera (1) | 3 | ITS5/ITS4A | AY843073 | Unknown zone 1, Capronia clade, Chaetothyriales |

| TRN206 | Atazar (1) | 3 | ITS1F/NL1R | AY843074 | Phaeotheca sp., Phaeotheca clade, Mycosphaerellaceae |

| TRN209 | Atazar (3) | 1 | ITS1F/NL1R | AY843075 | Phaeotheca sp., Phaeotheca clade, Mycosphaerellaceae |

| TRN210 | Atazar (1) | 1 | ITS5/ITS4A | AY843076 | Cladophialophora sp., unknown zone 3, Chaetothyriales |

| TRN211 | Atazar (1) | 1 | ITS5/NL1R | AY843077 | Phoma-like, Mycosphaerellaceae |

| TRN212 | Atazar (2) | 1 | ITS1F/NL1R | AY843078 | Phaeotheca sp., Phaeotheca clade, Mycosphaerellaceae |

| TRN213 | Atazar (1) | 1 | ITS1F/NL1R | AY843079 | Phaeococcomyces sp. |

| TRN214 | Atazar (1) | 1 | 18S-1/ITS4A | AY843080 | Cladophialophora sp.?, Chaetothyriales |

| TRN215 | Atazar (1) | 1 | ITS5/ITS4A | AY843081 | Sterile, Pleosporales |

| TRN216 | Atazar (2) | 3 | ITS5/NL1R | AY843082 | Sterile, Pleosporales |

| TRN219 | Atazar (1) | 1 | ITS5/NL1R | AY843083 | Sterile, Pleosporales |

| TRN220 | Atazar (1) | 1 | ITS5/NL1R | AY843084 | Sterile, ‘Cryomyces’ clade |

| TRN221 | Atazar (3) | 1 | ITS5/NL1R | AY843085 | Sterile, Pleosporales |

| TRN222 | Atazar (1) | 2 | ITS5/NL1R | AY843086 | Sterile, Pleosporales |

| TRN225 | Atazar (2) | 3 | ITS5/NL1R | AY843087 | Unknown zone 1, Capronia clade, Chaetothyriales |

| TRN227 | Atazar (1) | 2 | ITS5/ITS4A | AY843088 | Unknown zone 1, Capronia clade, Chaetothyriales |

| TRN230 | Atazar (2) | 2 | ITS5/ITS4A | AY843089 | Sterile, ‘Sarcinomyces petricola’ clade, Chaetothyriales |

| TRN231 | Atazar (1) | 1 | ITS5/NL1R | AY843090 | Sterile, Mycosphaerellaceae |

| TRN232 | Atazar (1) | 2 | ITS5/NL1R | AY843091 | Sterile, Teratosphaeriaceae clade, Capnodiales |

| TRN235 | Atazar (1) | 1 | 18S-3/NL1R | AY843092 | Phaeosclera sp., Dothideales (Phaeosclera clade), Dothideales |

| TRN236 | Atazar (2) | 1 | 18S-3/ITS4A | AY843093 | Phaeosclera sp., Dothideales (Phaeosclera clade), Dothideales |

| TRN237 | Atazar (3) | 3 | ITS5/ITS4A | AY843094 | Unknown zone 1, Capronia clade, Chaetothyriales |

| TRN240 | Atazar (2) | 1 | ITS5/ITS4A | AY843095 | Unknown zone 1, Capronia clade, Chaetothyriales |

| TRN242 | Atazar (1) | 1 | ITS5/ITS4A | AY843097 | Sterile, Chaetothyriales |

| TRN244 | Atazar (2) | 2 | ITS5/NL1R | AY843098 | Sterile, Mycosphaerellaceae |

| TRN245 | Atazar (1) | 1 | ITS5/NL1R | AY843099 | Sterile, Mycosphaerellaceae |

| TRN246 | Atazar (2) | 1 | ITS5/NL1R | AY843100 | Unknown zone 1, Capronia clade, Chaetothyriales |

| TRN247 | Atazar (1) | 1 | ITS5/NL1R | AY843101 | Unknown zone 1, Capronia clade, Chaetothyriales |

| TRN248 | Atazar (1) | 3 | ITS5/NL1R | AY843102 | Unknown zone 1, Capronia clade, Chaetothyriales |

| TRN252 | Atazar (3) | 2 | ITS5/NL1R | AY843103 | Unknown zone 1, Capronia clade, Chaetothyriales |

| TRN254 | Atazar (3) | 2 | 18S-3/ITS4A | AY843104 | Phaeosclera sp., Dothideales (Phaeosclera clade), Dothideales |

| TRN256 | Atazar (1) | 2 | 18S-3/ITS4A | AY843105 | Phaeosclera sp., Dothideales (Phaeosclera clade), Dothideales |

| TRN258 | Atazar (3) | 2 | ITS1F/NL1R | AY843106 | Sterile, Dothideales (core), Dothideales |

| TRN260 | Atazar (1) | 1 | ITS1F/NL1R | AY843107 | Unknown zone 1, Capronia clade, Chaetothyriales |

| TRN261 | Atazar (1) | 1 | 18S-1/ITS4A | AY843108 | Phaeosclera sp., Dothideales (Phaeosclera clade), Dothideales |

| TRN262 | Atazar (3) | 1 | ITS1F/NL1R | AY843109 | Sterile, Mycosphaerellaceae |

| TRN263 | Atazar (3) | 1 | ITS1F/NL1R | AY843110 | Phaeotheca sp., Phaeotheca clade, Mycosphaerellaceae |

| TRN264 | Atazar (1) | 1 | 18S-3/NL1R | AY843111 | Exophiala sp., Chaetothyiales |

| TRN267 | Atazar (3) | 2 | ITS1F/NL1R | AY843112 | Acrodontium crateriforme, Mycosphaerellaceae |

| TRN268 | Atazar (3) | 1 | ITS1F/NL1R | AY843113 | Hormonema sp., Dothideales (core), Dothideales |

| TRN269 | Atazar (3) | 1 | ITS1F/NL1R | AY843114 | Aureobasidium pullulans, Dothideales (core), Dothideales |

| TRN270 | Atazar (1) | 2 | ITS1F/NL1R | AY843115 | Phaeococcomyces sp., ‘black yeasts’ group |

| TRN272 | Atazar (3) | 3 | ITS1F/NL1R | AY843116 | Endoconidioma sp., Dothideales (core), Dothideales |

| TRN275 | Atazar (1) | 3 | ITS1F/NL1R | AY843117 | Endoconidioma sp., Dothideales (core), Dothideales |

| TRN278 | Atazar (2) | 1 | ITS1F/NL1R | AY616199 | Hormonema carpetanum, Dothideales (core), Dothideales |

| TRN279 | Atazar (3) | 1 | ITS1F/NL1R | AY843118 | Catenulostroma sp.?, Teratosphaeriaceae clade, Capnodiales |

| TRN280 | Atazar (3) | 1 | ITS1F/NL1R | AY843119 | Catenulostroma sp.?, Teratosphaeriaceae clade, Capnodiales |

| TRN281 | Atazar (1) | 1 | 18S-3/NL1R | AY843120 | Sterile, ‘Cryomyces’ group |

| TRN282 | Atazar (1) | 1 | 18S-3/NL1R | AY843121 | Sterile, Mycosphaerellaceae |

| TRN283 | Atazar (1) | 1 | ITS1F/NL1R | AY843122 | Sterile, Mycosphaerellaceae |

| TRN284 | Atazar (1) | 1 | ITS1F/NL1R | AY843123 | Sterile, Mycosphaerellaceae |

| TRN286 | Atazar (3) | 1 | ITS1F/NL1R | AY843124 | Sterile, Mycosphaerellaceae |

| TRN287 | Atazar (3) | 1 | ITS5/ITS4A | AY843125 | Sterile, Mycosphaerellaceae |

| TRN288 | Atazar (1) | 1 | ITS1F/NL1R | AY843126 | Sterile, Teratosphaeriaceae clade, Capnodiales |

| TRN289 | Atazar (1) | 1 | ITS5/ITS4A | AY843127 | Catenulostroma sp.?, Teratosphaeriaceae clade, Capnodiales |

| TRN290 | Atazar (1) | 1 | 18S-1/NL1R | AY843128 | Catenulostroma sp.?, Teratosphaeriaceae clade, Capnodiales |

| TRN431 | Patones (4) | 1 | 18S-3/ITS4A | AY843129 | Sterile, Mycosphaerellaceae |

| TRN432 | Patones (1) | 1 | 18S-3/ITS4A | AY843130 | Coniosporium apollinis, ‘Coniosporium apollinis’ clade |

| TRN433 | Patones (4) | 1 | 18S-3/ITS4A | AY843131 | Sterile, Mycosphaerellaceae |

| TRN434 | Patones (3) | 1 | 18S-3/ITS4A | AY843132 | Pleosporales |

| TRN436 | Patones (2) | 1 | 18S-3/ITS4A | AY843134 | Wardomyces sp.?, Chaetothyriales |

| TRN437 | Patones (4) | 1 | 18S-3/ITS4A | AY843135 | Sterile, Mycosphaerellaceae |

| TRN438 | Patones (4) | 1 | 18S-3/ITS4A | AY843136 | Sterile, Mycosphaerellaceae |

| TRN439 | Patones (1) | 1 | 18S-3/ITS4A | AY843137 | Cladosporium sp., Mycosphaerellaceae |

| TRN440 | Patones (4) | 1 | 18S-3/ITS4A | AY843138 | Sterile, Mycosphaerellaceae |

| TRN441 | Patones (1) | 1 | 18S-1/ITS4A | AY843139 | Sterile, Trimmatostroma clade, Mycosphaerellaceae |

| TRN442 | Patones (4) | 1 | 18S-1/ITS4A | AY843140 | Sterile, Mycosphaerellaceae |

| TRN443 | Patones (4) | 1 | 18S-3/ITS4A | AY843141 | Sterile, Mycosphaerellaceae |

| TRN444 | Patones (3) | 1 | 18S-3/ITS4A | AY843142 | Sterile, Dothideales |

| TRN445 | Patones (4) | 1 | 18S-3/ITS4A | AY843143 | Catenulostroma sp.?, Teratosphaeriaceae clade, Capnodiales |

| TRN446 | Patones (1) | 1 | 18S-3/ITS4A | AY843144 | Catenulostroma sp.?, Teratosphaeriaceae clade, Capnodiales |

| TRN447 | Patones (3) | 1 | 18S-3/ITS4A | AY843145 | Phaeosclera sp., Dothideales (Phaeosclera clade), Dothideales |

| TRN448 | Patones (1) | 1 | 18S-1/ITS4A | AY843146 | Phaeosclera sp., Dothideales (Phaeosclera clade), Dothideales |

| TRN449 | Patones (2) | 1 | 18S-3/ITS4A | AY843147 | Phaeococcomyces sp., ‘black yeasts’ group |

| TRN450 | Patones (2) | 1 | 18S-3/ITS4A | AY843148 | Cylindroxyphium sp., Capnodiales s.str., Mycosphaerellaceae |

| TRN451 | Patones (2) | 1 | 18S-3/ITS4A | AY843149 | Phaeococcomyces catenatus, Sacinomyces petricola clade, Chaetothyriales |

| TRN452 | Patones (1) | 1 | 18S-3/ITS4A | AY843150 | Phaeococcomyces sp., ‘black yeasts’ group |

| TRN453 | Patones (1) | 1 | 18S-3/ITS4A | AY843151 | Phaeotheca sp., Phaeotheca clade, Mycosphaerellaceae |

| TRN454 | Patones (3) | 1 | 18S-3/ITS4A | AY843152 | Phaeotheca sp., Phaeotheca clade, Mycosphaerellaceae |

| TRN455 | Patones (1) | 1 | 18S-3/ITS4A | AY843153 | Phaeococcomyces sp., ‘black yeasts’ group |

| TRN456 | Patones (4) | 1 | 18S-3/ITS4A | AY843154 | Phaeococcomyces nigricans, ‘black yeasts’ group |

| TRN458 | Patones (2) | 1 | 18S-3/ITS4A | AY843156 | Phaeococcomyces sp., ‘black yeasts’ group |

| TRN461 | Patones (4) | 4 | 18S-3/ITS4A | AY843158 | Sterile, Mycosphaerellaceae |

| TRN465 | Patones (1) | 1 | 18S-3/ITS4A | AY843160 | Coniosporium sp., ‘Coniosporium apollinis’ clade |

| TRN467 | Patones (4) | 2 | 18S-3/ITS4A | AY843161 | Sterile, Mycosphaerellaceae |

| TRN468 | Patones (4) | 1 | 18S-3/ITS4A | AY843162 | Sterile, Mycosphaerellaceae |

| TRN472 | Puebla de la Sierra | 3 | 18S-3/ITS4A | AY843164 | Sterile, Unknown zone 2, Chaetothyriales |

| TRN473 | Puebla de la Sierra | 3 | 18S-3/ITS4A | AY843165 | Sterile, Unknown zone 2, Chaetothyriales |

| TRN475 | Puebla de la Sierra | 3 | 18S-3/ITS4A | AY843166 | Sterile, Unknown zone 2, Chaetothyriales |

| TRN481 | Puebla de la Sierra | 1 | 18S-3/ITS4A | AY843167 | Sterile, Unknown zone 2, Chaetothyriales |

| TRN482 | Puebla de la Sierra | 2 | 18S-3/ITS4A | AY843168 | Sterile, Unknown zone 2, Chaetothyriales |

| TRN484 | Puebla de la Sierra | 1 | 18S-1/ITS1-3 | AY843169 | Sterile, Venturiaceae |

| TRN485 | Puebla de la Sierra | 1 | 18S-1/ITS1-3 | AY843170 | Unknown zone 2, Chaetothyriales |

| TRN486 | Puebla de la Sierra | 1 | 18S-3/NL1R | AY843171 | Sterile, Capronia clade, Chaetothyriales |

| TRN487 | Puebla de la Sierra | 1 | ITS5/ITS4A | AY843172 | Sterile, Capronia clade, Chaetothyriales |

| TRN488 | Puebla de la Sierra | 1 | ITS5/ITS4A | AY843173 | Cladophialophora sp., Chaetothyriales |

| TRN489 | Puebla de la Sierra | 1 | ITS5/ITS4A | AY843174 | Cladophialophora sp., Chaetothyriales |

| TRN491 | Puebla de la Sierra | 1 | ITS5/ITS4A | AY843175 | Sterile, Mycosphaerellaceae |

| TRN492 | Puebla de la Sierra | 1 | ITS5/ITS4A | AY843176 | Phaeococcomyces sp., ‘black yeasts’ group |

| TRN493 | Puebla de la Sierra | 3 | 18S-3/ITS4A | AY843177 | Exophiala sp., Capronia clade, Chaetothyriales |

| TRN495 | Puebla de la Sierra | 1 | 18S-3/ITS4A | AY843178 | Capronia clade, Chaetothyriales |

| TRN497 | Puebla de la Sierra | 1 | 18S-3/ITS4A | AY843179 | Exophiala sp., Capronia clade, Chaetothyriales |

| TRN498 | Puebla de la Sierra | 1 | 18S-3/ITS4A | AY843180 | Exophiala sp., Capronia clade, Chaetothyriales |

| TRN499 | Puebla de la Sierra | 2 | 18S-3/ITS4A | AY843181 | Sterile, Pleosporales |

| TRN500 | Puebla de la Sierra | 1 | 18S-3/ITS4A | AY843182 | Sterile, Phaeotheca clade, Mycosphaerellaceae |

| TRN502, TRN504 | Puebla de la Sierra | 4 | 18S-3/ITS4A | AY843183, AY843184 | Cladophialophora sp., unknown zone 3, Chaetothyriales |

| TRN506 | Puebla de la Sierra | 1 | 18S-3/ITS4A | AY843185 | Cladophialophora sp., unknown zone 3, Chaetothyriales |

| TRN507 | Puebla de la Sierra | 1 | 18S-3/ITS4A | AY843186 | Cladophialophora sp., unknown zone 3, Chaetothyriales |

| TRN508 | Puebla de la Sierra | 3 | ITS5/ITS4A | AY843187 | Cladophialophora sp., unknown zone 3, Chaetothyriales |

| TRN509 | Puebla de la Sierra | 3 | ITS5/ITS4A | AY843188 | Cladophialophora sp., unknown zone 3, Chaetothyriales |

| TRN510 | Puebla de la Sierra | 1 | ITS5/ITS4A | AY843189 | Cladophialophora sp., unknown zone 3, Chaetothyriales |

| TRN515 | Puebla de la Sierra | 5 | 18S-3/ITS4A | AY843190 | Cladophialophora sp., unknown zone 3, Chaetothyriales |

| TRN520 | Puebla de la Sierra | 1 | 18S-3/ITS4A | AY843191 | Phaeococcomyces-like, ‘black yeasts’ group |

| TRN521 | Puebla de la Sierra | 1 | 18S-3/ITS4A | AY843192 | Phaeosclera sp., Dothideales (Phaeosclera clade), Dothideales |

| TRN522 | Puebla de la Sierra | 1 | 18S-3/ITS4A | AY843193 | Cladophialophora sp., unknown zone 3, Chaetothyriales |

| TRN523 | Puebla de la Sierra | 1 | 18S-3/ITS4A | AY843194 | Phaeosclera sp., Dothideales (Phaeosclera clade), Dothideales |

| TRN524 | Puebla de la Sierra | 1 | 18S-1/ITS1-3 | AY843195 | Phaeosclera sp., Dothideales (Phaeosclera clade), Dothideales |

| TRN525 | Puebla de la Sierra | 1 | ITS1f/NL1R | AY843196 | Phaeosclera sp., Dothideales (Phaeosclera clade), Dothideales |

| TRN526 | Puebla de la Sierra | 1 | 18S-3/ITS4A | AY843197 | Sterile, Dothideales (core), Dothideales |

| TRN527 | Puebla de la Sierra | 1 | 18S-3/ITS4A | AY843198 | Sterile, unknown zone 2, Chaetothyriales |

| TRN528 | Puebla de la Sierra | 3 | 18S-3/ITS4A | AY843199 | Cladophialophora sp., unknown zone 3, Chaetothyriales |

| TRN529 | Puebla de la Sierra | 1 | 18S-3/ITS4A | AY843200 | phaeococcomyces-like, ‘black yeasts’ group |

| TRN531 | Puebla de la Sierra | 1 | 18S-3/ITS4A | AY843201 | Sterile, Capronia clade, Chaetothyriales |

| TRN533 | Puebla de la Sierra | 1 | ITS5/ITS4A | AY843202 | Sterile, Dothideales (core), Dothideales |

1 Sequences length from 455 to 568 bp.

2 ITS region accession numbers are in the same order as strain numbers, unless indicated otherwise.

PCR amplifications were performed with Taq DNA polymerase (QBiogene, Inc.) following the procedures recommended by the manufacturer (5 min at 93 °C followed by 40 cycles of 30 s at 93 °C, 30 s at 53 °C and 2 min at 72 °C). The amplification products (0.1 μg/mL) were sequenced using the Bigdye Terminator Cycle Sequencing Ready Reaction Kit with an ABI PRISM 3700 DNA Analyzer (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA, USA) following the manufacturer’s recommendations. Each strand of the amplification products was sequenced with the same primers used for the initial amplification.

Sequence analyses

Partial sequences obtained in sequencing reactions were assembled using GCG software (GCG Wisconsin Package, v. 10.3-Unix, Accelrys Inc., San Diego, CA) generating a consensus sequence for each fungal strain. Consensus sequences were aligned by CLUSTAL X (Thompson et al. 1997) and the program-generated multiple alignments were visually adjusted with GeneDoc v. 2.5 software (Nicholas & Nicholas 1997). Maximum-parsimony and neighbour-joining analyses were performed with PAUP v. 4 using the default settings (Swofford 1998). Data were resampled with 1 000 bootstrap replicates (Felsenstein 1985) by using the heuristic search option of PAUP. The percentage of bootstrap replicates that yielded greater than 50 % for each group was used as a measure of statistical confidence. Sequence matching with public or proprietary databases was performed with BLAST2N and FastA applications (GCG Wisconsin Package).

RESULTS

Number of isolates and efficiency of the isolation method

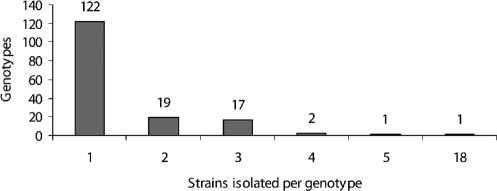

A total of 266 strains were isolated from the four locations of the Central Mountain System (Table 1). Sixty nine isolates were obtained from La Cabrera, representing 33 genotypes; from Atazar, 85 isolates were recovered, representing 57 genotypes; from Patones, 47 isolates were obtained that accounted for 34 genotypes; and finally, 65 isolates were recovered from Puebla de la Sierra, representing 39 genotypes. From the total set, only five genotypes were found to be common to two or more sites: 1) TRN156, TRN492, and TRN270; 2) TRN165 and TRN258; 3) TRN280/TRN289, and TRN173; 4) TRN4 and TRN451; and 5) TRN1, TRN230, and TRN35. Seventy five percent (122) of the genotypes established by MP-PCR were isolated only once; the rest varied in abundance (Fig. 2). Only one genotype (TRN50 group) was significantly abundant; it was isolated 18 times from granite of La Cabrera. These results were consistent with our previous studies of limestone in Mallorca, where infrequent and unique genotypes predominated (Ruibal et al. 2005). The even distribution of predominantly single and infrequent genotypes indicated that the isolation method was adequate to recover large number of genetically different strains and suggested an undersampling of high species diversity (Gotelli & Colwell 2001). Because of the high number of single genotypes and scant overlap among the four samples, no obvious pattern with respect to site or rock type was evident. The absence of cosmopolitan, airborne fungi, e.g., Penicillium and Alternaria species, among the set of isolates indicated that the whole isolation procedure, including both rock surface sterilisation and dissection of fast, hyaline mycelia, was effective.

Fig. 2.

Isolation frequencies of 162 different fungal genotypes isolated from stone. Genotypes were established based on a grouping by microsatellite-primed PCR products.

Morphology, grouping of taxonomic units and identification

The set of isolates generally exhibited a limited spectrum of morphological features. Colonies were strongly pigmented, ranging across a gradient of different tones and intensities from grey, dark-olive, olive-brown to black. Dark pigmentation was the main criterion for colony selection from isolation plates and therefore its predominance limited reliable discrimination among isolates.

Another macromorphological trend among our isolates was their slow radial growth. The mean diameter of a set of isolates selected based on an ITS-sequence similarity grouping (n = 70) on the five characterisation media was 14.1 mm, with the largest average radial growth in OTM medium (17.1 mm) and the smallest in AI medium (11 mm). The mycelia of a significant proportion of isolates (10 %) exhibited scarce or nearly imperceptible radial growth from the inoculation point. Also a significant percentage of the plates (10 %) exhibited a pattern of forming tiny punctuate colonies, probably arising from fragmented cell masses, or by forming colonies from cells accumulated in dense, irregular masses via meristematic growth.

Among the array of colony textures observed, filamentous textures with poorly developed aerial mycelia were the most common, although compact and dense colonies with a dry, granulose-crustose texture were evident in a high percentage of the isolates (mainly in CZA medium). Black yeast-like colonies in the classical sense (de Hoog & Hermanides-Njihof 1977) were infrequent among our set of isolates (see below). Mycelial exudates or soluble pigments in the agar were largely absent among the isolates.

The observation and identification of melanised rock fungi in culture was problematic due to their strong pigmentation and their often hard or granular texture which often made preparation of isolates for microscopy difficult. The microscopic morphology of the majority of the isolates revealed sterile mycelia with poorly differentiated, few or no specialised structures and tissues. Asexual sporulating states were infrequent and sexual states absent. Common microscopic features observed among isolates included hyphae with densely melanised, firm or thick-walled cells, vegetative hyphae of nearly rectangular cells that develop into torulose/moniliform hyphal pattern, cells that occasionally develop transverse and oblique septa, and that sometimes develop muriform or multicellular structures.

A hundred and fifty three isolates were selected (Table 2) based in their position in the ITS tree and examined microscopically; 64 of them (41.8 %) did not exhibit any conidial or sexual state on the media set and were considered sterile mycelia. The rest exhibited diverse modes of conidiogenesis and, in a few cases, isolates developed pycnidial conidiomata, or apparently multicellular structures that may have been primordial or aborted conidiomata. Unequivocal identification of isolates with conidial states was only possible in the cases of TRN3, TRN31, TRN25, TRN278, TRN40, TRN24 (Hormonema carpetanum), TRN37, TRN 269 (Aureobasidium pullulans), TRN432 (Coniosporium apollinis), TRN456 (Phaeococcomyces nigricans), TRN497, TRN498 (Exophiala spinifera), TRN4, TRN451 (Phaeococcomyces catenatus), and TRN267 (Acrodontium crateriforme). In other cases, we classified the isolates into anamorph form genera, such as Endoconidioma, ‘Stigmina’ (see Crous et al. 2006a), Phaeosclera, Coniosporium, Phaeococcomyces, Sclerococcum, Exophiala, Cladophialophora, Wardomyces, Catenulostroma, Trimmatostroma, Fusicladium, Phaeotheca and Cylindroxyphium (Table 2). Lastly, other isolates were assigned to morphological types coinciding with classical, polyphyletic genera, e.g., Cladosporium (Table 2). In most cases, however, unequivocal identifications were not possible; therefore more extensive studies will be necessary to determine whether the fungi could be new species or if they were vegetative states of known ascomycetous fungi.

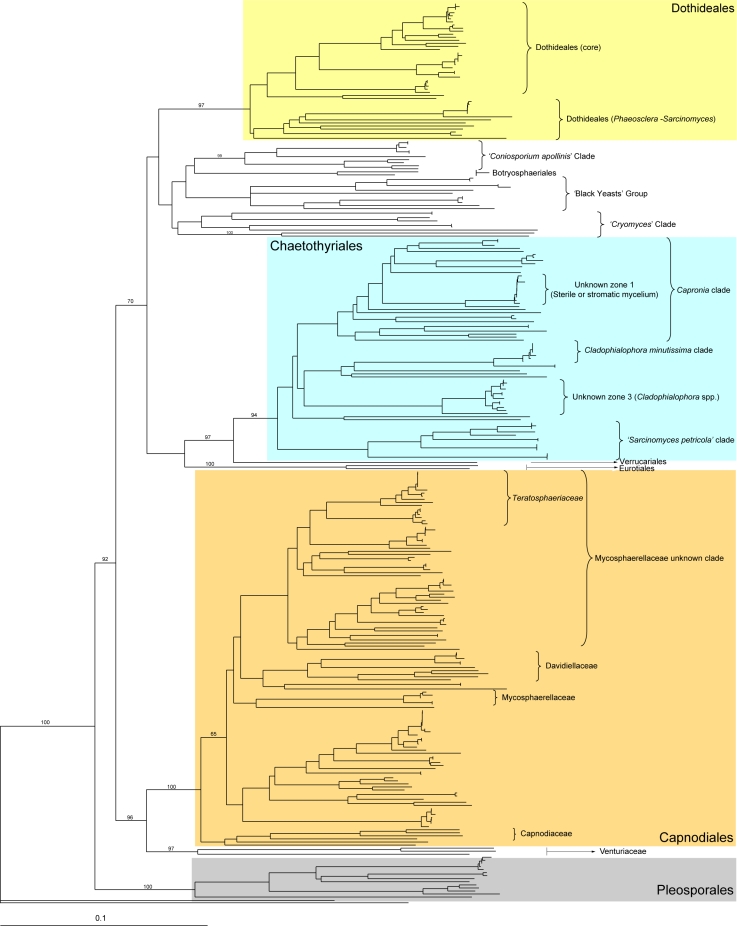

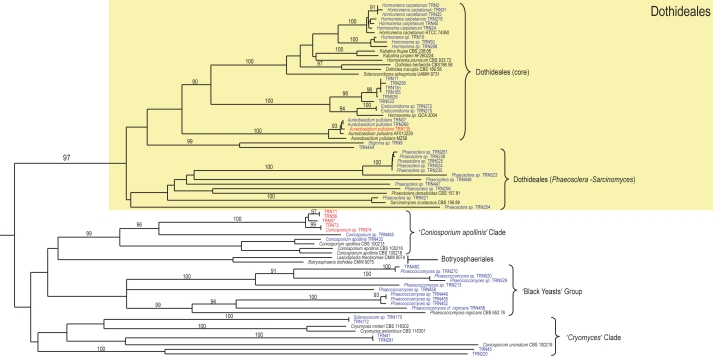

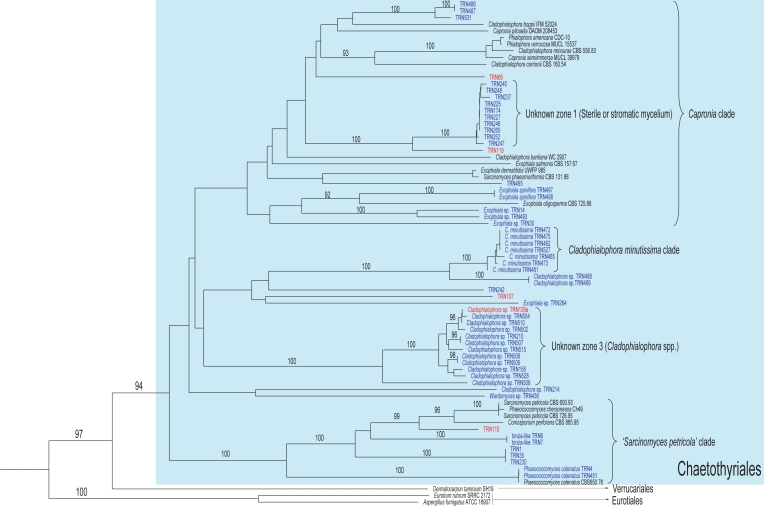

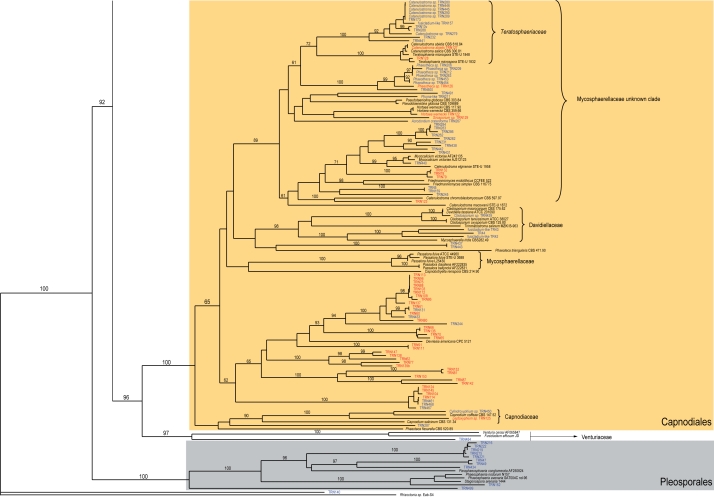

Strain grouping based on position in the ITS tree attempted to reveal correlations between morphological and molecular traits (Table 2). When morphological trends were superimposed onto a sequenced-based framework some molecular groups showed strong morphological cohesion. Clades of fungi corresponding to Catenulostroma, Cladophialophora, Exophiala, Hormonema, Phaeococcomyces, Phaeosclera, and Phaeotheca, were apparent (Fig. 3, 4, 5).

Fig. 3.

Phylogram of the neighbour-joining tree obtained from melanised rock surface isolates and selected reference strains sequences of the ITS1-5.8S-ITS2 ribosomal region. Statistical support (1 000 bootstrap replicates) values of indicated at branch points of the main branches.

Fig. 4.

Partial phylogram of the neighbour-joining tree obtained from melanised rock surface isolates and reference strains sequences of the ITS1-5.8S-ITS2 ribosomal region (Fig. 3). Branches corresponding to the Dothideales clade, ‘Coniosporium apollinis’ clade, ‘black yeasts’ group, and ‘Cryomyces’ clade.

Fig. 5.

Partial phylogram of the neighbour-joining tree obtained from melanised rock surface isolates and reference strains sequences of the ITS1-5.8S-ITS2 ribosomal region (Fig. 3). Branches corresponding to the Chaetothyriales, Eurotiales, and Verrucariales clades.

Recognition of genotypes by microsatellite-primed PCR

Cluster analysis of MP-PCR products of the 266 initial isolates identified 163 different genotypes (analysis not shown). The ITS region from at least one example of each genotype was sequenced. In several cases, the ITS region from more than one representative of each genotype was sequenced to verify the assumption that a group of isolates from a common MP-PCR pattern represented a single species (Table 1). Therefore, ITS sequences were obtained from a total of 171 isolates (Table 2). Phenetically similar isolates from different sites were also sequenced to determine if they shared common genotypes leading to the conclusion that only five genotypes occurred at multiple collection sites.

Amplification and sequencing of the ITS region of rDNA

To estimate the relative phylogenetic relationships among the isolates and the reference strains, the ITS sequences of the 159 isolates were aligned with reference sequences from GenBank that were selected based on sequence similarity, or because they were potentially related taxa. A sequence alignment was used to generate a tree by the neighbour-joining method (Fig. 3). A basidiomycete was chosen as outgroup (Rhizoctonia sp. Eab-S4) because FASTA analyses indicated the isolates spanned a broad spectrum of the Pezizomycotina. We did not intend to recreate the taxonomic frame of the phylum, but sought to quickly estimate the relative phylogenetic position and if possible arrive at an identification. Results were similar to more specific analyses of other authors in similar groups, and several main clades received strong bootstrap support, so the consistency of the tree seemed to be remarkably high considering that we had attempted to compare sequences of such different fungi. Isolate TRN140 yielded the most disparate ITS sequence and was not clearly associated with any other group of strains (Fig. 3).

ITS-tree, Dothideomycetes

The tree was divided in four main branches (Fig. 3). The first of these branches grouped together (with no relevant support), the order Dothideales and other clades of uncertain taxonomic position. The first branch in the Dothideales (Fig. 4) was the only which received strong bootstrap support (97 %). It was divided into two main sub-branches; the first comprised the reference strains of the Dothideales s.str. and a group of isolates identified as Hormonema carpetanum (Bills et al. 2004b), and other hormonema-like isolates. The second branch was referable to the reference strains Sarcinomyces crustaceus (CBS 156.89) and Phaeosclera dematioides (CBS 157.81), both ascomycetous anamorphs of uncertain affinity. All the isolates included in this branch were identified as Phaeosclera sp. Although these fungi are of unknown affinities, the branch was monophyletic with that of the Dothideales s.str., so a close relationship could be inferred among the branches.

ITS-tree, unidentified branches associated with the Dothideomycetes

In a major branch parallel to the Dothideales clade appeared a series of sub-branches with no relevant statistical support (Fig. 4). The lack of statistical confidence and the heterogeneous nature of the isolates casted doubts on the phylogenetic significance of this clade. The first among the branches was designated as the ‘Coniosporium apollinis’ clade (Fig. 4), and included two reference sequences of C. apollinis, a rock-inhabiting fungus from Greece (Sterflinger et al. 1997). This branch, strongly supported by a bootstrap value of 99 %, also contained our isolates; TRN432, identified as C. apollinis based on its sequence and its morphology, and TRN465, TRN74, designated as Coniosporium sp. The rest of the isolates (TRN71, TRN56, TRN57, and TRN73) may be congeneric with C. apollinis. Also two species of the Botryosphaeriaceae, Lasiodiplodia theobromae (Alves et al. 2008) and B. dothidea (Crous et al. 2006b), appeared associated with the ‘Coniosporium apollinis’ clade.

The next unsupported clade was designated as the ‘black yeasts’ group (Fig. 4) because all strains formed colonies consisting largely of melanised unicellular aggregates. Yeast-like forms were infrequently found among other clades of the tree. However, in this branch, the nearly exclusive yeast-like growth was distinctive and diagnostic. The only reference sequence that grouped within this clade was Phaeococcomyces nigricans (CBS 652.76). Due to their distinctive morphological characteristics and their position in the tree, the other isolates in this group were identified as Phaeococcomyces spp. The last of the unsupported clades related to the Dothideales was designated as the ‘Cryomyces’ clade, because the isolates grouped with reference sequences of Cryomyces antarcticus and C. minteri (Selbmann et al. 2005) (Fig. 4).

ITS-tree, Eurotiomycetes

Although the second main clade corresponded with the orders Chaetothyriales, Verrucariales, and Eurotiales (Fig. 3), it lacked significant support. These three orders have been proposed to belong to the class Eurotiomycetes (Lutzoni et al. 2004, Miadlikowska & Lutzoni 2004, Reeb et al. 2004). The Eurotiales branch (100 % bootstrap value) was formed only by the reference sequences and included no rock isolates (Fig. 5). Chaetothyriales and Verrucariales appeared grouped with a high bootstrap value (97 %). The order Chaetothyriales was amply represented among our isolates and received a bootstrap value of 94 % (Fig. 5). The clade was divided into a number of sub-branches. The only one with a strong support (bootstrap value of 100 %), contained several previously characterised melanised fungi found in rocks such as Sarcinomyces petricola and Coniosporium perforans, and sequences of the anamorph species Phaeococcomyces catenatus. The remaining branches of the Chaetothyriales (Capronia clade, Cladophialophora minutissima clade) did not receive relevant support and seemed to correspond to the Chaetothyriales family Herpotrichiellaceae, which includes the genus Capronia and some of its recognised or suspected anamorphs, e.g., Cladophialophora, Exophiala, and Phialophora. Also within this region appeared groups of closely related sequences (unknown zones 1 and 2) with no correspondence with any reference sequence (Fig. 5). The last branch of the Eurotiomycetes clade was formed solely by the reference sequence of the lichenised fungus Dermatocarpon taminium SH19 (Fig. 5), a member of the order Verrucariales (Heiðmarsson 2003).

ITS-tree, Capnodiales

The third main branch grouped with relatively high bootstrapping (bootstrap value 96 %) both the order Capnodiales (bootstrap support 100 %) and the family Venturiaceae of the order Pleosporales (97 % bootstrap value), (Fig. 3). The Capnodiales clade comprised a number of sub-branches grouped with a bootstrap value of 65 %, and a Capnodiaceae clade. Among the other sub-branches were a Davidiellaceae clade (Crous et al. 2007a, b) and a Mycosphaerellaceae clade, both with high bootstrap values (Schoch et al. 2006) (Fig. 6). A clade (bootstrap value of 89 %) named as ‘Mycosphaerellaceae unknown clade’, included a number of miscellaneous anamorphic ascomycetes, including the Teratosphaeriaceae (72 % bootstrap value) (Crous et al. 2007a). Finally, a clade (65 % bootstrap value) containing a number of isolates and Devriesia americana (STE-U 5121 = CBS 117726) (Crous et al. 2007c) as unique reference sequence. Finally, the Venturiaceae was represented by isolate TRN484, grouped with the reference strains Venturia cerasi and Fusicladium effusum (Fig. 6). For the most part, isolates in the Capnodiales formed only vegetative mycelia in culture. The major exceptions were fungi with endoconidia that we tentatively called Phaeosclera (Sigler et al. 1981), cladosporium-like, and catenulostroma-like fungi.

Fig. 6.

Partial phylogram of the neighbour-joining tree obtained from melanised rock surface isolates and reference strains sequences of the ITS1-5.8S-ITS2 ribosomal region (Fig. 3). Branches corresponding to the Mycosphaerellaceae, Venturiaceae, and Pleosporales clades.

ITS-tree, Pleosporales

The last of these branches was identified with the order Pleosporales (bootstrap value of 100 %) and included reference sequences belonging to the family Phaeosphaeriaceae (Pleosporales) (Fig. 3). All the isolates in the clade only formed vegetative mycelia and could not be directly related with any known reference sequences, although the high bootstrap values of all the branches show the high affinity of the isolates with the Phaeosphaeriaceae (Fig. 6).

DISCUSSION

Biogeography and diversity

The abundance and variety of isolates encountered in a previous study of fungi in Mallorcan limestone (Ruibal et al. 2005) was surprisingly high, therefore we wanted to confirm whether this pattern of taxonomic diversity was repeatable in the continental environment of central Spain. In Mallorca, limestone from two sites yielded 117 melanised isolates that were determined to represent 39 different genotypes. Anticipating that levels of diversity could be comparable, we were cautious not to sample widely or extensively until the levels of abundance of fungi in continental rock samples could be evaluated. We started with four different rock types (granite, slate, limestone, and quartzite) at four different sites. The only criteria used to select different kinds of rock samples were that rocks would be relatively clean and free from influence of soil and lichens and could be easily lifted off the rock faces with a chisel. No attempt was made to enrich the samples by choosing stained or biologically deteriorated surfaces or surfaces that were obviously colonised by black fungal structures.

Rock surfaces harboured an easily accessible reservoir of melanised ascomycetes. Even with arbitrary selection of rock substrata, a set of isolates was obtained that exhibited a combination of cryptic morphology and phylogenetic affinities agreeing with, or even surpassing, previous studies on rock-inhabiting fungi in the Mediterranean and other locations. The assemblage of isolates from central Spain resembled that recovered from limestone in the Balearic Islands (Ruibal et al. 2005) and included some genera, species or species assemblages detected by other investigators (Staley et al. 1982, de Hoog et al. 1997, Sterflinger et al. 1997, Wollenzien et al. 1997, de Leo et al. 1999, 2003, Onofri et al. 1999, Bogomolova & Minter 2003). The phylogenetic bias towards the Dothideales, Capnodiales, and Chaetothyriales was especially evident (Fig. 3, 4, 5). The high diversity observed in two different regions in Spain confirms that our isolation technique was an appropriate method for the isolation of melanised fungi on rock surfaces and that the patterns of diversity are probably common for rock surfaces in a semi-arid environment. The patterns of diversity and species assemblages of the rock surfaces contrasted sharply and had little in common with the species assemblages that would be expected from an adjacent community of soil fungi (Bills et al. 2004a).

Genotypic diversity

Because many of the isolates were macroscopically similar, even on sets of media that normally would exaggerate differences in other fungi, we could not confidently use traits such as mycelial growth rate and pigmentation or texture to group them into operational taxonomic units (Arnold et al. 2000, Bills et al. 2004a). We based our comparison and grouping strategy on MP-PCR complemented by the macromorphological appearance of the isolates. The method allowed us to more efficiently analyse fewer isolates without losing diversity information. We were able to check the usefulness of this method by verifying that sequenced isolates with the same MP-PCR pattern grouped together in the ITS tree (Table 2, Fig. 3). However, we found isolates with virtually identical ITS sequences but with different MP-PCR patterns, implying that different individuals of the same species were grouped together. On the other hand, when different strains with identical MP-PCR patterns were sequenced, they consistently had identical ITS sequences. Therefore, the strategy avoided loss of diversity when choosing isolates for sequencing. The assumption that one MP-PCR pattern was equivalent to one species was questionable in many cases. Hormonema carpetanum strains with discrete MP-PCR patterns also varied by a few base pairs in their ITS2 sequences, yet upon detailed morphological and fine-scale phylogenetic analyses strains from rocks were considered to be conspecific with plant-associated isolates from the same region (Bills et al. 2004b). Terminal branches consisting of essentially one ITS type (Fig. 2, 3, 4, 5) likely represented multiple isolates of single species, such as in the case of TRN261, TRN236, TRN525, TRN524, and TRN235 (Fig. 4), unknown zones 1 and 2 (Fig. 5), or TRN280, TRN446, TRN445, TRN290, TRN289 (Fig. 6).

Morphological data

The convergent morphological features of these fungi are thought to be related to adaptations to environmental conditions. The most obvious was the melanin pigment production, necessary for protection against desiccation and ultraviolet radiation, and possibly the binding of certain metallic ions, which, depending on their nature, may stimulate the growth and survival of melanised fungi or protect them from metal toxicity (Gorbushina 2003). It has been shown that certain metabolites, such as mycosporines, apart from their ultraviolet-protective properties, possess germination self-inhibitory functions, useful for the survival, persistence and longevity of these organisms. The slow and granular meristematic growth is thought to be related with energy conservation, necessary for survival on substrates with scarce nutrient input (Gorbushina 2003, Gorbushina et al. 2003).

Microscopically, sterile mycelia predominated among the isolates (Table 2). Lack of specialised reproductive structures could be an artefact caused by the cultural conditions; however, unspecialised reproduction would be consistent with a hypothesis of specialised organisms living in an oligotrophic, extreme environment. The lack of reproductive structures could also be considered an adaptation for energy conservation (Gorbushina 2003, Gorbushina et al. 2003). In a regime of scarce nutrients and water that exist on rock surfaces, the high energetic costs required for the growth of complex reproductive structures would select for fungi with less elaborate reproduction systems, such as simple modes of conidiogenesis, or melanised, desiccation-resistant, hyphal structures that fragment and act as propagules.

Among the isolates that formed conidial states, varied types of conidiogenesis were observed (Table 2), which was reflected in the diverse taxonomic origins of the isolates. In the rest of the isolates, conidial states were not observed, although in some, hyphal disarticulation could free cells or cells aggregates that could act as propagules. This disarticulation of melanised, torulose hyphae, whose cells could occasionally develop transverse septa, suggested a thallic micronematous conidiogenesis or simple reproduction by propagative fragmentation. Other characters observed in the sterile mycelia, such as torulose and/or moniliform hyphae, chlamydospore-like structures, hyphopodia-like branching, and muriform or meristematic development, even though relatively common, were of limited diagnostic value. Correspondence among morphological types and the groups established by the phylogenetic analysis of the ITS sequences of the isolates was evident only in some cases. Although meristematic strains with black yeast-like growth patterns have been documented in culture (de Hoog et al. 1999, Sterflinger et al. 1999), yeast-like growth forms were infrequent among the isolates.

Diagnostic value of the molecular data: ITS rDNA phylogram

Most isolates could be loosely grouped in two main classes of ascomycetes: Dothideomycetes and Eurotiomycetes, and among four orders: Pleosporales, Dothideales, Capnodiales, and Chaetothyriales. Our analyses were not able to recover monophyly in the Dothideomycetes, as in Schoch et al. (2006), but our data sampling and analyses were inappropriate for this type of resolution.

Dothideomycetes

The order Dothideales (Fig. 4) was amply represented. A diverse set of isolates within this cluster were identified as Phaeosclera spp. based primarily on their hard, granular to cerebriform colonies originating from meristematic cell division (Sigler et al. 1981), and forming cell masses disarticulating into single cells or cell aggregates.

Ambiguous clades adjacent to the Dothideales

The taxonomic affiliations of the fungi belonging to the group of ITS clades adjacent to the Dothideales clade (the ‘Coniosporium apollinis’ clade, Botryosphaeriales, the ‘black yeast’ group, and the ‘Cryomyces’ clade) were difficult to discern. In the first, ‘Coniosporium apollinis’ clade (Fig. 4), the majority of the reference sequences belonged to strains of the genus Coniosporium. This is a heterogeneous form-genus applied to some melanised meristematic fungi that cluster close to the Chaetothyriales (de Leo et al. 1999). The Coniosporium species referenced in this tree were all isolated from stone (C. apollinis in the ‘Coniosporium apollinis’ clade, C. uncinatum in the ‘Cryomyces’ clade, and C. petricola in the Chaetothyriales clade). The polyphyly of Coniosporium species in the ITS tree is an example of an artificial genus based on convergent morphologies possibly related to similar adaptations to extreme environments. Two reference strains belonging to the Botryosphaeriaceae corresponded to the recently described Botryosphaeriales (Crous et al. 2006b, Schoch et al. 2006).

The second clade of uncertain affinities, labelled ‘black yeast group’ (Fig. 4), included isolates with entirely yeast-like growth, and as the only reference strain Phaeococcomyces nigricans CBS 652.76. The genus Phaeococcomyces is employed for melanised fungi that lack filamentous growth and has been considered a synanamorph of certain species of Exophiala (Haase et al. 1995, de Hoog et al. 2000a). The clade perhaps could represent an unrecognised new genus related to the Chaetothyriales.

The last unsupported clade, ‘Cryomyces’ clade (Fig. 4), included reference sequences of Cryomyces antarcticus and C. minteri (Selbmann et al. 2005), both meristematic, melanised endolithic fungi isolated from Antarctic. The result pointed to a possible cosmopolitan distribution of melanised, meristematic, rock-inhabiting fungi, enabled by their exceptional tolerance to extreme environmental conditions, and emphasised the great unexplored diversity of this ecological group. Reference sequence Coniosporium uncinatum CBS 100219 appeared in this group, along with isolate TRN174, identified as the form-genus Sclerococcum based on its sporodochia-like colonies, consisting of masses of melanised cells organised in chains and arising from a meristematic tissue (Hawksworth 1979).

Chaetothyriales

This was the best represented order among our isolates. The clade was subdivided in three subclades (Fig. 5). In the first one, identified as the ‘S. petricola’ clade, series of isolates were grouped together with reference sequences of uncertain affiliation, e.g., Coniosporium perforans, Phaeococcomyces chersonesos, and Sarcinomyces petricola. All are species of melanised fungi isolated from rock surfaces (Sterflinger et al. 1997, Wollenzien et al. 1997, Bogomolova & Minter 2003) and were assigned to form-genera solely based on their morphologies. Placement of these heterogeneous groups in a particular order was ambiguous based only on ITS sequences analysis. For example, Sarcinomyces is a controversial form-genus almost entirely defined by being meristematic growth of cells to form asexual propagules, which may be an inadequate definition for organisms with high morphological plasticity. Note as an example the polyphyly represented in the ITS analysis by Sarcinomyces petricola, Sarcinomyces phaeomuriformis (in the Capronia clade), and Sarcinomyces crustaceus (in the Phaeosclera-Sarcinomyces branch of the Dothideales clade). These species have been associated with Phaeococcomyces catenatus in a separate clade adjacent to the Herpotrichiellaceae (Chaetothyriales) (Sterflinger et al. 1999). The strong statistical support of these associations suggested that these fungi belong to the Chaetothyriales.

The second subclade in the Chaetothyriales, identified as the Capronia clade, included reference sequences of the Herpotrichiellaceae. The subclade also included a group of very similar vegetative isolates with a high statistical support and no related reference strains. This distinctive clade structure (marked as ‘unknown zone 1′, Fig. 5) might represent individuals of a new species, or members of a species complex.

The third subclade of the Chaetothyriales group comprised two similarly structured groups of isolates. A group apparently conspecific with Cladophialophora minutissima (Davey & Currah 2007), a recently described new species from boreal bryophytes, and the unknown zone 3 (Fig. 5).

Capnodiales

The ITS Capnodiales clade (Fig. 6) was composed of five main subclades, three of them, Davidiellaceae, Mycosphaerellaceae, and Capnodiaceae, comprising the Capnodiales as defined by Schoch et al. (2006). The two remaining subclades shared some of the characteristics of other groups of uncertain affiliation that were previously mentioned. The ‘Mycosphaerellaceae unknown clade’ contained reference strains considered synonyms of Mycosphaerella (Teratosphaeria microspora) or its anamorphs, some isolated as leaf spot pathogens on Proteaceae (Taylor et al. 2003). These strains, identified initially as Trimmatostroma and Stenella, have been later renamed as Catenulostroma (Crous et al. 2007a). In particular, the Teratosphaeriaceae clade (Fig. 6) showed some morphological resemblance to Trimmatostroma species characteristic of decayed wood surfaces (Ellis 1971, 1976). Trimmatostroma, with the generic type species T. salicis, was recently treated as a genus of Leotiales, while the capnodialean species were reclassified in Catenulostroma (Crous et al. 2007a). Teleomorph connections of Catenulostroma are in Teratosphaeria.

The last subclade in the Capnodiales included several vegetative mycelial strains, mostly isolated from Mallorca. The nearest reference sequence to these series of isolates was Devriesia americana (STE-U 5121) (Crous et al. 2000, 2007b). Recently, the phylogeny of the Capnodiales has been extensively treated by Schoch et al. (2006). The resulting phylogeny differentiates two subclasses in the Dothideomycetes, Pleosporomicetidae (Pleosporales) and Dothideomycetidae (Dothideales, Myriangiales, and Capnodiales), Capnodiaceae, Mycosphaerellaceae, Davidiellaceae, and Piedraiaceae are introduced or placed within the Capnodiales. Crous et al. (2007a) have also included Teratosphaeriaceae in the Capnodiales. In our analysis, the Capnodiales was poorly delineated, especially regarding rock isolates as in previous studies (Ruibal et al. 2005).

Pleosporales

Isolates and reference sequences belonging to the order Pleosporales, were separated into two groups in the analysis. First, the Pleosporales clade comprised the majority of the isolates and reference sequences belonging to the family Phaeosphaeriaceae. The second was comprised of the Venturiaceae clade, with only one isolate from rock, TRN484 (Fig. 6). The polyphyletic character of the Pleosporales clade, supported by high bootstrappings, is in agreement with the results of other authors (Braun et al. 2003). Devriesia americana and other isolates sequences morphologically identified as fusicladium-like anamorph appeared divergent to the reference sequences of the Venturiaceae (Venturia cerasi, Fusicladium effusum). These contradictory analyses are an example of the inability of ribosomal rDNA sequences to resolve many relationships among the euascomycetes (Berbee et al. 2000), but also account for the unclear identity and classification of some of the 18S and ITS sequences deposited in GenBank.

Conclusions

The analysis, and that of Ruibal et al. (2005), revealed that a remarkable diversity of ascomycetous fungi can be found in a relatively small surface area of natural rock. Our results confirm those conclusions over a larger geographical scale. Because most isolates were rare, the question as to whether they were restricted to a particular location or rock type was not evident. Our analysis did not reveal any genotypic specificity for the types of rock or sites sampled, as evidenced by few number MP-PCR patterns common to at least two isolation sites and the apparent random distribution of isolates from different sites throughout the ITS tree. A more extensive and intensive microscale analysis emphasizing aspect, shade, waterflow, and other rock patterns possibly could have detected preferential colonisation patterns. On the other hand, rock surfaces may simply provide mechanical support, where organisms disperse at random and can compete in an ecological space with a relatively low population density, and where competitiveness for resources is much lower than in other niches. The mineral composition of rocks may only have minimal effects on fungal nutritional metabolism. Nutrient sources are likely to be exogenous and very transient. Perhaps water from rain, fog, and surface run off carry dissolved or suspended organic and inorganic nutrients to the vicinity of fungal cells. Such an oligotrophic pattern along with the extreme conditions would prevent colonisation by high nutrient-dependent, cosmopolitan organisms, while favouring the settlement and specialisation of a wide range of organisms that share a common set of morphological and physiological features. The characteristics exhibited by these organisms would not necessarily be exclusive to rock surfaces, they might also allow them to colonise other living or inert surfaces in the same ecosystems, such as bark and leaf epiphytes, plant pathogens (Mycosphaerella-related strains) or even animal pathogens (human-pathogenic strains in the Chaetothyriales). The physiological and morphological specialisation of these fungi would give them an advantage in such environments that might be also considered ‘extreme’. If this hypothesis was true, rock surfaces, with their very oligotrophic environment, could be considered the origin and reservoir of these pathogenic organisms.

Acknowledgments

The expert and steadfast technical assistance of Mrs Ana Pérez (Merck, Spain) was greatly appreciated. Portions of this work were derived from a doctoral dissertation submitted by the first author to the Faculty of Sciences of the Universidad Autónoma de Madrid.

REFERENCES

- Alves A, Crous PW, Correia A, Phillips AJL. 2008. Morphological and molecular data reveal cryptic speciation in Lasiodiplodia theobromae. Fungal Diversity 28: 1 – 13 [Google Scholar]

- Arnold AE, Maynard Z, Gilbert G, Coley PD, Kursar TA. 2000. Are tropical fungal endophytes hyperdiverse? Ecology Letters 3: 267 – 274 [Google Scholar]

- Bellido Mulas F, Rodríguez Fernández LR. Mapa Geológico de España. Instituto Tecnológico Geominero de España; Buitrago de Lozoya, Madrid, Spain: 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Berbee ML, Carmean DA, Winka K. 2000. Ribosomal DNA and resolution of branching order among the Ascomycota: How many nucleotides are enough? Molecular Phylogenetics and Evolution 17: 337 – 344 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bills GF, Christensen M, Powell M, Thorn G. 2004a. Saprobic soil fungi. In: Mueller GM, Bills GF, Foster MS. (eds), Biodiversity of fungi. Inventory and monitoring methods: 271–302 Elsevier Academic Press, Burlington, MA, USA: [Google Scholar]

- Bills GF, Collado J, Ruibal C, Peláez F, Platas G. 2004b. Hormonema carpetanum sp. nov., a new lineage of dothideaceous black yeasts from Spain. Studies in Mycology 50: 14 – 157 [Google Scholar]

- Bogomolova EV, Minter DW. 2003. A new microcolonial rock-inhabiting fungus from marble in Chersonesos (Crimea, Ukraine). Mycotaxon 86: 195 – 204 [Google Scholar]

- Braun U, Crous PW, Dugan F, Groenewald JZ, Hoog GS de. 2003. Phylogeny and taxonomy of Cladosporium-like hyphomycetes, including Davidiella gen. nov., the teleomorph of Cladosporium s.str. Mycological Progress 2: 3 – 18 [Google Scholar]

- Crous PW, Aptroot A, Kang JC, Braun U, Wingfield MJ. 2000. The genus Mycosphaerella and its anamorphs. Studies in Mycology 45: 107 – 121 [Google Scholar]

- Crous PW, Braun U, Groenewald JZ. 2007a. Mycosphaerella is polyphyletic. Studies in Mycology 58: 1 – 32 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crous PW, Braun U, Schubert K, Groenewald JZ. 2007b. Delimiting cladosporium from morphologically similar genera. Studies in Mycology 58: 33 – 56 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crous PW, Liebenberg MM, Braun U, Groenewald JZ. 2006a. Re-evaluating the taxonomic status of Phaeoisariopsis griseola, the causal agent of angular leaf spot of bean. Studies in Mycology 55: 163 – 173 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crous PW, Schubert K, Braun U, Hoog GS de, Hocking AD, Shin H-D, Groenewald JZ. 2007c. Opportunistic, human-pathogenic species in the Herpotrichiellaceae are phenotypically similar to saprobic or phytopathogenic species in the Venturiaceae. Studies in Mycology 58: 185 – 217 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crous PW, Slippers B, Wingfield MJ, Rheeder J, Marasas WFO, Philips AJL, Alves A, Burgess T, Barber P, Groenewald JZ. 2006b. Phylogenetic lineages in the Botryosphaeriaceae. Studies in Mycology 55: 235 – 253 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davey ML, Currah RS. 2007. A new species of Cladophialophora (hyphomycetes) from boreal and montane bryophytes. Mycological Research 111: 106 – 116 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ellis MB. 1971. Dematiaceous hyphomycetes Commonwealth Mycological Institute, Kew, United Kingdom: [Google Scholar]

- Ellis MB. 1976. More dematiaceous hyphomycetes. Commonwealth Mycological Institute, Kew, United Kingdom: [Google Scholar]

- Felsenstein J. 1985. Confidence intervals on phylogenies: an approach using bootstrap. Evolution 39: 783 – 791 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gams W, Verkley GJM, Crous PW. 2007. CBS course of mycology, 5th ed Centraalbureau voor Schimmelcultures, Utrecht, the Netherlands: [Google Scholar]

- García L, Aparicio A. 1987. Geología del Sistema Central Español Comunidad de Madrid, Madrid, Spain: [Google Scholar]

- Gardes M, Bruns TD. 1993. ITS primers with enhanced specificity for basidiomycetes - Application to the identification of mycorrhizae and rust. Molecular Ecology 2: 113 – 118 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gorbushina AA. 2003. Methodologies and techniques for detecting extraterrestrial (microbial) life. Microcolonial fungi: survival potential of terrestrial vegetative structures. Astrobiology 3: 543 – 554 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gorbushina AA, Whitehead K, Dornieden T, Niesse A, Schulte A, Hedges JI. 2003. Black fungal colonies as unit of survival: hyphal mycosporines synthesized by rock dwelling microcolonial fungi. Canadian Journal of Botany 81: 131 – 138 [Google Scholar]

- Gotelli NJ, Colwell RK. 2001. Quantifying biodiversity: procedures and pitfalls in the measurement and comparison of species richness. Ecology Letters 4: 379 – 391 [Google Scholar]

- Haase G, Sonntag L, Peer Y van der, Uijthof JMJ, Podbielski A, Melzerkrick M. 1995. Phylogenetic analysis of ten black yeast species using nuclear small subunit rRNA gene sequences. Antonie van Leeuwenhoek 68: 19 – 33 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hawkworth DL. 1979. The lichenicolous hyphomycetes. Bulletin of the British Museum of Natural History (Botany) 6: 183 – 300 [Google Scholar]

- Heiđmarsson S. 2003. Molecular study of Dermatocarpon miniatum (Verrucariales) and allied taxa. Mycological Research 107: 459 – 468 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoog GS de, Beguin H, Batenburg-van de Vegte WH. 1997. Phaeotheca triangularis, a new meristematic black yeast from a humidifier. Antonie van Leeuwenhoek 71: 289 – 295 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoog GS de, Bowman B, Graser Y, Haase G, El Fari M, Ende AGGH van der, Melzer-Krick B, Untereiner WA. 1998. Molecular phylogeny and taxonomy of medically important fungi. Medical Mycology 36: 52 – 56 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoog GS de, Guarro J, Gené J, Figueras MJ. 2000a. Atlas of clinical fungi. 2nd ed Centraalbureau voor Schimmelcultures/Universitat Rovira i Virgili; Utrecht, The Netherlands/Reus, Spain: [Google Scholar]

- Hoog GS de, Hermanides-Nijhof EJ. 1977. The black yeasts and allied hyphomycetes. Studies in Mycology 15: 1 – 222 [Google Scholar]

- Hoog GS de, Queiroz-Telles F, Haase G, Fernandez-Zeppenfeldt G, Attili Angelis D, Gerrits van der Ende AHG, Matos T, Peltroche-Llacsahuanga H, Pizzirani-Kleiner AA, Rainer J, Richard-Yegres N, Vicente V, Yegres F. 2000b. Black fungi: clinical and pathogenic approaches. Medical Mycology 38: 243 – 250 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoog GS de, Sigler L, Untereiner WA, Kwon-Chung KJ, Guého E, Uijthof JMJ. 1994. Changing taxonomic concepts and their impact on nomenclatural stability. Journal of Medical and Veterinary Mycology 32: 113 – 122 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoog GS de, Zalar P, Urzí C, Leo F de, Yurlova NA, Sterflinger K. 1999. Relationships of dothideaceous black yeasts and meristematic fungi based on 5.8S and ITS2 rDNA sequence comparison. Studies in Mycology 43: 31 – 37 [Google Scholar]

- Kroken S, Glass NL, Taylor J, Yoder OC, Turgeon B. 2003. Phylogenomic analysis of type I polyketide synthase genes in pathogenic and saprobic ascomycetes. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 100: 15670 – 15675 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Larena I, Salazar O, González V, Julian MC, Rubio V. 1999. Design of a primer for ribosomal DNA internal transcribed spacer with enhanced specificity for ascomycetes. Journal of Biotechnology 75: 187 – 194 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leo F de, Urzí C, Hoog GS de. 1999. Two coniosporium species from rock surfaces. Studies in Mycology 43: 70 – 79 [Google Scholar]

- Leo F de, Urzí C, Hoog GS de. 2003. A new meristematic fungus, Pseudotaeniolina globosa. Antonie van Leeuwenhoek 83: 351 – 360 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Longato S, Bonfante P. 1997. Molecular identification of mycorrhizal fungi by direct amplification of microsatellite regions. Mycological Research 101: 425 – 432 [Google Scholar]

- Lutzoni F, Kauff F, Cox CJ, McLaughlin D, Celio G, Dentinger B, Padamsee M, Hibbett D, James TY, Baloch E. et al. 2004. Assembling the fungal tree of life: progress, classification, and evolution of subcellular traits. American Journal of Botany 91: 1446 – 1480 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miadlikowska J, Lutzoni F. 2004. Phylogenetic classification of peltigeralean fungi (Peltigerales, Ascomycota) based on ribosomal RNA small and large subunits. American Journal of Botany 91: 449 – 464 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nicholas KB, Nicholas HB. 1997. GeneDoc, a tool for editing and annotating multiple sequence alignments. (Software distributed by the author.) [Google Scholar]

- O’Donnell K. 1993. Fusarium and its near relatives. In: Reynolds D, Taylor J. (eds), The fungal holomorph: mitotic, meiotic and pleomorphic speciation in fungal systematics: 225–233 C.A.B. International Wallingford; [Google Scholar]

- Onofri S, Pagano S, Zucconi L, Tosi S. 1999. Friedmanniomyces endolithicus (Fungi, Hyphomyces), anam.-gen. and sp. nov., from continental Antarctica. Nova Hedwigia 68: 175 – 181 [Google Scholar]

- Peláez F, Platas G, Collado J, Díez MT. 1996. Infraspecific variation in two species of aquatic hyphomycetes, assessed by RAPD analysis. Mycological Research 100: 831 – 837 [Google Scholar]