Abstract

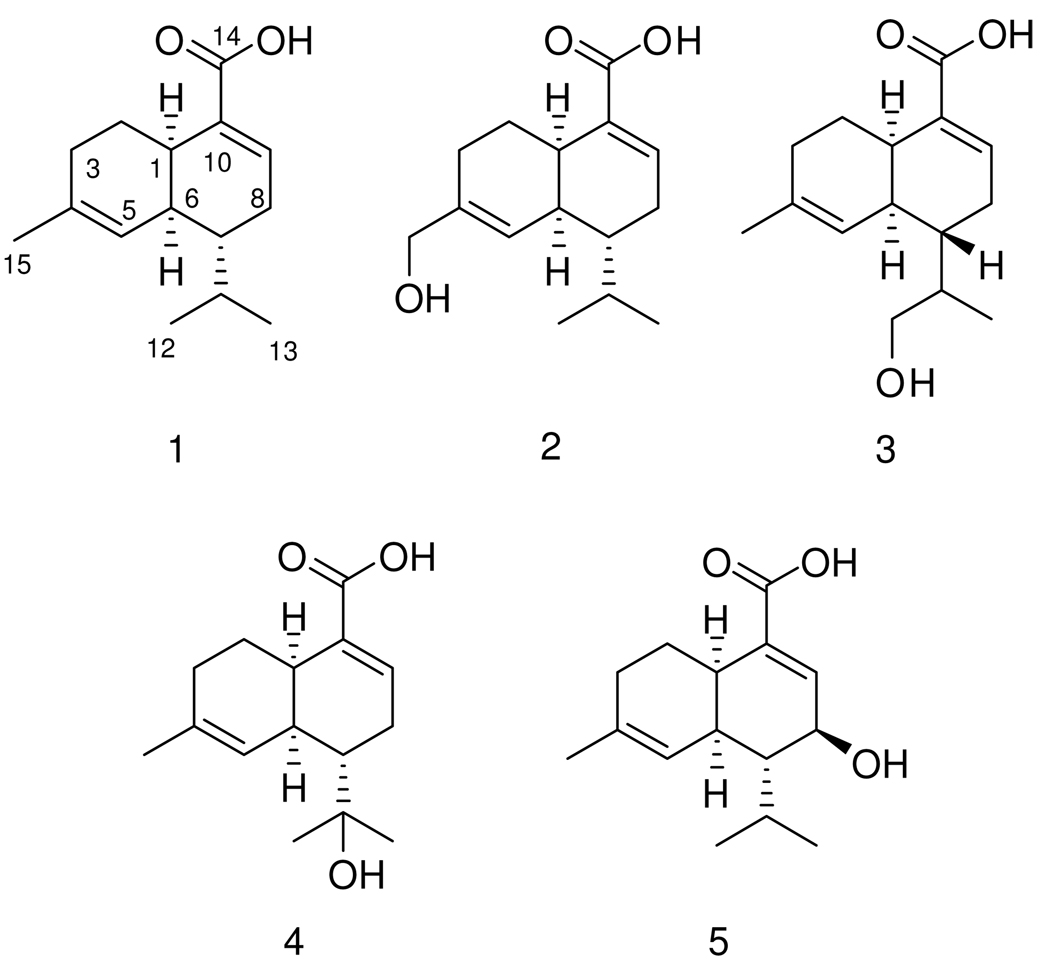

The marine-derived fungus Cadophora malorum was isolated from the green alga Enteromorpha sp. Growth on a biomalt medium supplemented with sea salt yielded an extract from which we have isolated sclerosporin and four new hydroxylated sclerosporin derivatives, namely 15-hydroxysclerosporin (2), 12-hydroxysclerosporin (3), 11-hydroxysclerosporin (4) and 8-hydroxysclerosporin (5). The compounds were evaluated in various biological activity assays. Compound 5 showed a weak fat-accumulation inhibitory activity against 3T3-L1 murine adipocytes.

In recent years, research on the chemistry of marine organisms has experienced a tremendous increase, due to the need for compounds possessing bioactivity with possible pharmaceutical application or other economically useful properties.1 From these organisms, marine fungi are recognized as a valuable source for new and bioactive secondary metabolites that have the potential to lead to innovations in drug therapy.2 Sclerosporin is a rather rare antifungal and sporogenic cadinane-type sesquiterpene.3,4 This substance, initially isolated from Sclerotinia fruticula showed an induction of asexual arthrospore formation in fungal mycelia.3,5 Interestingly, its (−)-form isolated from Diplocarpon mali did not showed sporogenic activity towards S. frutícula.5,6 During our search for new natural products produced from the marine-derived fungus Cadophora malorum, (+)-sclerosporin (1) and four new hydroxylated sclerosporin derivatives (2 – 5) were isolated from a spore culture on agar-BMS media supplemented with artificial sea salt.

The molecular formulae of compounds 2 – 5 were deduced by HREIMS to be identical, i.e. C15H22O3, indicating five degrees of unsaturation. The 13C NMR spectra for all four compounds showed 15 closely similar resonance signals, evidencing that each of the compound belonged to the same structural type. In each case a 13C NMR downfield shifted resonance signal at δ 168 – 170 was found, typical for a carboxylic acid functionality (C-14), whereas a further resonance signal at around δ 70 indicated a hydroxy substituted methylene for compounds 2 and 3, a hydroxy substituted methine for compound 5, and for compound 4 a hydroxylated quaternary carbon (see Table 1–Table 2, respectively). IR spectroscopic measurements showed a broad absorption band at 3300 cm−1 for 2 – 5, also confirming the presence of a hydroxy substituent in each case.

Table 1.

1H NMR Spectroscopic Data for Compounds 2 – 5.

| 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Position | δHa (J in Hz) | δHa (J in Hz) | δHb (J in Hz) | δHb (J in Hz) |

| 1 | 2.58, br d (11.4) | 2.58, br d (10.2) | 2.54, br d (10.6) | 2.43, br d (10.6) |

| 2 | a: 1.99, m | a: 1.91, m | a: 1.89, m | a: 1.93, m |

| b: 1.37, qd (11.4, 5.4) | b: 1.42, qd (11.7, 5.4) | b: 1.50, qd (11.7, 5.5) | b: 1.45, qd (11.7, 5.4) | |

| 3 | 2.08, m | a: 2.06, m | a: 1.98, m | a: 2.08, m |

| b: 1.88, m | b: 1.95, m | b: 1.93, m | ||

| 5 | 5.79, d (4.1) | 5.52, br s | 5.71, br d (5.1) | 5.57, br d (4.4) |

| 6 | 2.04, m | 2.10, m | 2.11, m | 2.10, m |

| 7 | 1.53, tt (10.2, 5.1) | 1.65, tt (10.2, 5.1) | 1.68, td (10.3, 5.1) | 1.52, ddd (3.2, 8.7, 10.7) |

| 8 | a: 2.15, dt (19.8, 5.1) | a: 2.27, dt (19.8, 5.1) | a: 2.38, dt (19.6, 5.1) | 4.13, br d (8.7) |

| b: 1.97, m | b: 2.02, m | b: 2.01, m | ||

| 9 | 7.14, br s | 7.10, br s | 6.95, br t (3.9) | 6.79, d (1.8) |

| 11 | 2.03, m | 2.05, m | 2.25, m | |

| 12 | 0.83, d (6.8) | a: 3.77 (dd, 4.8, 10.6) | 1.23, s | 1.00, d (7.1) |

| 13 | 0.90, d (6.8) | 1.03, d (7.0) | 1.18, s | 1.10, d (7.1) |

| 14 | ||||

| 15 | 4.03, br s | 1.68, br s | 1.66, br s | 1.68, br s |

CDCl3, 300 MHz.

Acetone-d6, 300 MHz.

Table 2.

13C NMR Spectroscopic Data for Compounds 2 – 5.

| 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Position | δC, mult.a,c | δC, mult.a,c | δC, mult.b,c | δC, mult.b,c |

| 1 | 34.0, CH | 33.8, CH | 35.6, CH | 35.2, CH |

| 2 | 25.1, CH2 | 25.4, CH2 | 26.2, CH2 | 26.0, CH2 |

| 3 | 26.2, CH2 | 30.3, CH2 | 30.8, CH2 | 31.5, CH2 |

| 4 | 138.3, qC | 135.6, qC | 133.7, qC | 134.9, qC |

| 5 | 124.3, CH | 123.0, CH | 126.6, CH | 125.1, CH |

| 6 | 35.5, CH | 35.8, CH | 36.9, CH | 36.2, CH |

| 7 | 40.0, CH | 38.6, CH | 47.2, CH | 48.8, CH |

| 8 | 25.4, CH2 | 28.0, CH2 | 29.7, CH2 | 68.7, CH |

| 9 | 142.6, CH | 142.1, CH | 140.2, CH | 143.7, CH |

| 10 | 132.9, qC | 133.1, qC | 134.3, qC | 134.3, qC |

| 11 | 26.4, CH | 35.3, CH | 72.6, qC | 27.3, CH |

| 12 | 15.0, CH3 | 64.9, CH2 | 27.4, CH3 | 18.9, CH3 |

| 13 | 21.3, CH3 | 15.4, CH3 | 28.7, CH3 | 21.1, CH3 |

| 14 | 172.2, qC | 172.0, qC | 168.0, qC | 168.0, qC |

| 15 | 67.3, CH2 | 23.9, CH3 | 23.9, CH3 | 23.9, CH3 |

CDCl3, 75.5 MHz.

Acetone-d6, 75.5 MHz.

Implied multiplicities determined by DEPT.

1H-1H COSY data for 2 revealed a spin system ranging from H2-3 via H-1 and H-6 to H2-9 and to H3-12/H3-13, thus outlining major parts of the planar structure. Protons H2-15 showed a 1H-1H long range coupling to H-5, which together with an HMBC correlation from H2-15 to C-3 and from H-5 to C-6 completed the first ring of 2. HMBC correlations from H-9 to C-14 connected the carboxylic acid moiety with C-10, which in turn had to be bound to C-1 due to a HMBC correlation from H-1 to C-10 and to C-9. The planar structure of compound 2 was thus that of sclerosporin (1) hydroxylated at C-15.

Sclerosporin itself was also obtained during this study. The molecular formula of 1 was deduced by accurate mass measurement (HREIMS) to be C15H22O2. The final structure of 1 was identified as that of the known compound (+)-sclerosporin by comparing its NMR data and optical rotation with published values.4,5

The carbon skeleton of compounds 3 – 5 and the position of the double bonds were also found to be identical to that of 1, as deduced from 1D and 2D NMR analyses. All compounds are thus cadinane type sesquiterpenes with a sclerosporin nucleus (see Table 1–Table 2) and differ merely concerning the site of hydroxylation.

The position of the hydroxy group in 3 and 4 was established making use of 1H-1H COSY and HMBC data. Thus, in 3 the 13C NMR resonance signal for C-12 (δ 64.9) was shifted downfield, and H-12 (δ 3.52) showed coupling with H-11, placing the hydroxy substituent at C-12. The 13C NMR spectrum of 4 exhibited a downfield shifted quaternary carbon (δ 72.6, C-11) along with singlet proton resonances for the methyl groups CH3-12/CH3-13 in the 1H NMR spectrum, thus the hydroxy substituent had to be placed at C-11. The 13C NMR spectrum of 5 exhibited only two resonances for methylene groups (C-2, C-3) instead of three such moieties as in 2 – 4. Instead of the methylene group CH2-8 in 2 – 4, in 5 a methine group resonating at δ 68.7 and δ 4.13 in the 13C and 1H NMR spectra respectively was found. The 1H-1H COSY spectrum revealed correlations between H-8 and H-9 as well as H-7, positioning the hydroxy substituent in 5 at C-8. The planar structures of 2 – 5 were thus established to be 15-hydroxysclerosporin (2), 12-hydroxysclerosporin (3), 11-hydroxysclerosporin (4) and 8-hydroxysclerosporin (5).

The Cotton effect in the CD spectrum of (+)-sclerosporin (1) was similar to that reported in the literature,7 confirming the absolute configuration of 1 to be that of (+)-sclerosporin (see Table 3). The absolute configurations of compounds 2 – 5 were established by analyses of CD and NOESY spectra. The CD spectra of the hydroxylated compounds 2 – 5 were closely similar to that of (+)-sclerosporin (1), thus the identical absolute configuration can be proposed for compounds 2 – 4 (see Table 3). However, the configuration at position C-11 in 3 remains unresolved. Interestingly, 5 was the only one with a negative specific rotation (see Table 3). This change on specific rotation was most probably caused by the additional stereogenic center at C-8. The configuration at C-8 was established making use of NOESY correlations and 1H-1H coupling constants. A NOESY correlation between H-1 and H-6 is in agreement with the configuration of the other sclerosporin derivatives, and further correlations between H-8 and H-6, H-11, H3-12, H3-13 indicate these protons to be in the same spatial orientation. Furthermore, a 1H-1H coupling constant of 8.7 Hz between H-7 and H-8 indicated a trans-type spatial arrangement. Knowing the absolute configuration of H-1, H-6 and H-7 from CD spectroscopic data, we can thus assign the configuration of 5 to be 1R, 6S, 7R, 8S.

Table 3.

Comparison of the CD Spectra and Specific Rotation Values for the Reported Sclerosporins (+ and −) and Compounds 1 – 5.

| Compound | Δε Maxima and Minima in the CD Spectra (c 1.6 × 10−6 mol/L, MeOH) |

Optical Rotation | |

|---|---|---|---|

| (+) | (+)-sclerosporin7 | Δε196 + 11.0a | [α]20 D + 11.4 (c 0.035, MeOH) |

| (−) | (−)-sclerosporin5 | Δε214 + 17.0a | [α]20 D − 11.1 (c 0.090, MeOH) |

| (1) | (+)-sclerosporin | Δε196 + 10.1, Δε215 − 12.4 | [α]23 D + 14 (c 0.033, MeOH) |

| (1) | (+)-sclerosporin | [α]23 D + 57 (c 0.033, CHCl3) | |

| (2) | (+)-15-hydroxy | Δε197 + 5.2, Δε214 − 14.8 | [α]23 D + 64 (c 0.033, CHCl3) |

| (3) | (+)-12-hydroxy | Δε195 + 6.1, Δε214 − 6.2 | [α]23 D + 69 (c 0.033, CHCl3) |

| (4) | (+)-11-hydroxy | Δε198 + 3.2, Δε213 − 16.3 | [α]23 D + 73 (c 0.033, CHCl3) |

| (5) | (−)-8-hydroxy | Δε193 + 8.2, Δε215 − 8.0 | [α]23 D − 62 (c 0.033, CHCl3) |

Δε minima for + and − sclerosporin not reported in the literature

We propose the trivial names (+)-15-hydroxysclerosporin, (+)-12-hydroxysclerosporin, (+)-11-hydroxysclerosporin and (−)-8-hydroxysclerosporin for compounds 2, 3, 4 and 5, respectively.

Compound 2 was evaluated in the protease elastase (HLE) inhibition assay (tested at 100 µM), in the cytotoxic activity assay against a panel of three cancer cell lines (NCI-H460, MCF7 and SF268, tested at 100 µM), in the protein kinases DYRK1A and CDK5 inhibition activity assay (tested at 10 mM), for inhibition of the viral HIV-1 and HIV-2 induced cytopathogenic effect in MT-4 cells (tested at 50 µg/mL), in the Epstein-Barr virus (EBV) assay (tested at 100 µg/mL), and in the antiplasmodial activity assay against Plasmodium berghei (tested at 25 µM), but did not show any activity. Compound 2 was further tested against a pannel of three respiratory viruses, the severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus (SARS) assay, Flu A (H5N1) and Flu B (tested at 100 µg/mL in the three tests), bud did not show any significant activity. Compound 3 was evaluated against two influenza viruses, Flu A (H5N1) and Flu B (tested at 100 µg/mL), but did not show any activity. Compound 5 was evaluated against 3-T3-L1 murine adipocytes assay and showed weak inhibitory activity on fat-accumulation with an IC50 of 212 µM for triglyceride accumulation inhibition along with an IC50 cytotoxic effect value of 304 µM (see Supp. Inf.).

All compounds were tested for sporogenic activity (concentrations from 0.005 µg/mL to 5 µg/mL in BMS-agar plates) but the results were inconclusive, i.e. sporogenesis activity was observed but not with direct correlation with increasing quantity, probably due to compound stability problems. All compounds were evaluated in antibacterial (Escherichia coli, Bacillus megaterium), antifungal (Mycotypha microspora, Eurotium rubrum, and Microbotryum violaceum), and antialgal (Chlorella fusca) assays but did not showed any activity at a dose of 50 µg/disc.

Experimental Section

General Experimental Procedures

Optical rotations were measured on a Jasco DIP 140 polarimeter. UV and IR spectra were obtained employing Perkin-Elmer Lambda 40 and Perkin-Elmer Spectrum BX instruments, respectively. CD spectra were recorded in MeOH at room temperature using a JASCO J-810-150S spectropolarimeter. All NMR spectra were recorded in CDCl3 or (CD3)2CO employing a Bruker Avance 300 DPX spectrometer. Spectra were referenced to residual solvent signals with resonances at δH/C 7.26/77.0 for CDCl3 and δH/C 2.04/29.8 for (CD3)2CO. HREIMS were recorded on a Finnigan MAT 95 spectrometer. ESIMS measurements were recorded employing an API 2000, Applied Biosystems/MDS Sciex. HPLC was carried out using a system composed of a Waters 515 pump together with a Knauer K-2300 differential refractometer. HPLC columns were from Knauer (250 × 8 mm, 5 µm, Eurospher-100 Si), flow rate 2 mL/min. Merck silica gel 60 (0.040–0.063 mm, 70–230 mesh) was used for vacuum liquid chromatography (VLC). Columns were wet-packed under vacuum using petroleum ether (PE). Before applying the sample solution, the columns were equilibrated with the first designated eluent. Standard columns for crude extract fractionation had dimensions of 13 × 4 cm.

Fungal material

The marine-derived fungus Cadophora malorum (Kidd & Beaumont) W. Gams was isolated from the green alga Enteromorpha sp. and identified by P. Massart and C. Decock, BCCM/MUCL, Catholic University of Louvain, Belgium. A specimen is deposited at the Institute for Pharmaceutical Biology, University of Bonn, isolation number “SY3-1-1MIT”.

Culture, extraction and isolation

A sporous culture of Cadophora malorum on a 10 L solid biomalt medium (biomalt 20 g/L, 15 g/L agar) supplemented with sea salt was performed during 3 months. An extraction with 5 L EtOAc yielded 890 mg of extract which was subjected to a VLC fractionation in a silica open column using a gradient solvent system from PE to acetone, namely 10:1, 5:1, 2:1, 1:1, 100 % acetone and 100 % MeOH, yielded a total of 6 fractions. Compounds 1 to 5 were isolated from VLC fraction 2 (112 mg) by HPLC fractionation using PE-acetone 5:1.

Sclerosporin (1) was collected in fraction 1 of 7 (2.7 mg, RT 6 min); (+)-15-hydroxysclerosporin (2) was collected in fraction 7 of 7 (14.0 mg, RT 22 min); (+)-12-hydroxysclerosporin (3) was collected in fraction 6 of 7 (7.1 mg) which was further purified by HPLC fractionation with PE-acetone 26:5 (fraction 1 of 2; 4.5 mg, RT 31 min); (+)-11-hydroxysclerosporin (4) was collected in fraction 3 of 7 (2.2 mg, RT 13 min); (−)-8-hydroxysclerosporin (5) was collected in fraction 2 of 7 (3.5 mg, RT 11 min).

(1R, 6S, 7R)-(+)-sclerosporin (1)

[α]23D + 57 (c 0.033, CHCl3); CD (see Table 3); HREIMS m/z 234.1623 (calcd for C15H22O2, 234.1620); spectroscopic data were identical with the previously reported data.4,5,7

(1R, 6S, 7R)-(+)-15-hydroxysclerosporin (2)

yellow amorphous solid (1.4 mg/L, 1.57 %); [α]23D + 64 (c 0.033, CHCl3); UV (MeOH) λmax (log ε) 217 nm (3.8); CD (see Table 3); IR (ATR) νmax 3397, 2927, 1682 cm−1; 1H NMR and 13C NMR (see Table 1 and Table 2); LREIMS m/z 250.1; HREIMS m/z 232.1457 [M-H2O]+ (calcd for C15H20O2, 232.1463).

(1R, 6S, 7S)-(+)-12-hydroxysclerosporin (3)

yellow amorphous solid (0.71 mg/L, 0.81 %); [α]23D + 69 (c 0.033, CHCl3); UV (MeOH) λmax (log ε) 218 nm (3.9); CD (see Table 3). IR (ATR) νmax 3397, 2923, 1682 cm−1; 1H NMR and 13C NMR (see Table 1 and Table 2); LREIMS m/z 250.1; HREIMS m/z 232.1463 [M - H2O]+ (calcd for C15H20O2, m/z 232.1463).

(1R, 6S, 7S)-(+)-11-hydroxysclerosporin (4)

yellow amorphous solid (0.22 mg/L, 0.25 %); [α]23D + 73 (c 0.033, CHCl3); UV (MeOH) λmax (log ε) 219 nm (3.8); CD (see Table 3); IR (ATR) νmax 3277, 2928, 1681 cm−1; 1H NMR and 13C NMR (see Table 1 and Table 2); LREIMS m/z 250.1; HREIMS m/z 232.1464 [M - H2O]+ (calcd for C15H20O2, m/z 232.1463).

(1R, 6S, 7R, 8S)-(−)-8-hydroxysclerosporin (5)

yellow amorphous solid (0.35 mg/L, 0.39 %); [α]23D - 62 (c 0.033, CHCl3); UV (MeOH) λmax (log ε) 220 nm (3.7); CD (see Table 3); IR (ATR) νmax 3397, 2928, 1688 cm−1;1H NMR and 13C NMR (see Table 1 and Table 2); LREIMS m/z 250.1; HREIMS m/z 232.1458 [M - H2O]+ (calcd for C15H20O2, m/z 232.1463).

Biological Assays

The referenced compounds were tested in antibacterial (Escherichia coli, Bacillus megaterium), antifungal (Mycotypha microspora, Eurotium rubrum, and Microbotryum violaceum), and antialgal (Chlorella fusca) assays,8,9 in protease elastase (HLE) inhibition assay,10 protein kinases (DYRK1A and CDK5) inhibition assay,11 3-T3-L1 murine adipocytes assay,12 cytotoxic activity assay against a panel of three cancer cell lines (NCI-H460, MCF7 and SF268),13 sporogenic activity assay,5,6 HIV-1 and HIV-2 virus assay,14 antiplasmodial activity assay against Plasmodium berghei on the liver stage,15 severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus (SARS) assay,16 Epstein-Barr virus (EBV) assay,17 and in two influenza viruses (Flu A and Flu B) assays.18

Supplementary Material

Figure 1.

Acknowledgement

We thank the kind help of H. Greve and A. Kralj for all the lab support; Dr. K. Dimas (Biomedical Research Foundation of Academy of Athens, Athens, Greece) for the cytotoxicity assays, Prof. Dr. M. Gütschow (Institute for Pharmaceutical Chemistry, University of Bonn, Germany) for performing the HLE protease inhibition assay, Dr. L. Meijer (Protein Phosphorylation & Disease, CNRS, Roscoff, France) for performing the protein kinase assays, Dr. K. Shimokawa (Department of Chemistry, Nagoya University, Japan) for performing the 3T3-L1 murine adipocytes assay, Dr. C. Pannecouque (Rega Institute for Medical Research, Leuven, Belgium) for performing the HIV-1 and HIV-2 antiviral assays and Dr. M. Prudêncio (Malaria Unit, Institute for Molecular Medicine, University of Lisbon, Portugal) for performing the antiplasmodial activity assays; we also kindly thank the U.S. National Institutes of Health for performing the Flu A, Flu B, SARS and EBV antiviral activity assays which were supported by contracts NO1-A1-30048 (Institute for Antiviral Research, IAR) and NO1-AI-15435 (IAR) from the Virology Branch, National Institute of Allergic and Infectious Diseases, NIAID; we also kindly thank the financial support from FCT (Science and Technology Foundation, Portugal), and BMBF (project No. 03F0415A ).

Footnotes

Dedicated to the late Dr. John W. Daly of NIDDK, NIH, Bethesda, Maryland and to the late Dr. Richard E. Moore of the University of Hawaii at Manoa for their pioneering work on bioactive natural products.

Supporting Information Available: 1H and 13C NMR, HREIMS, IR, CD spectra and other relevant information are included for compounds 1 – 5. This material is available free of charge via the Internet at http://pubs.acs.org.

References and Notes

- 1.Andersson RJ, Williams DE. In: Chemistry in Marine Environment. Hester RE, Harrison RM, editors. Cambridge: The Royal Society of Chemistry; 2000. p. 55. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Haefner B. Drug Discov. Today. 2003;8:536–544. doi: 10.1016/s1359-6446(03)02713-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Katayama M, Marumo S, Hattori H. Tetrahedron Lett. 1983;24:1703–1706. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Datta BK, Rahman MM, Gray AI, Nahar L, Hossein SA, Auzi AA, Sarker SD. J. Nat. Med. 2007;61:391–396. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kitahara T, Matsuoka T, Katayama M, Marumo S, Mori K. Tetrahedron Lett. 1984;25:4685–4688. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sawai K, Okuno T, Yoshkawa E. Agric. Biol. Chem. 1985;49:2501–2503. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kitahara T, Kurata H, Matsuoka T, Mori K. Tetrahedron. 1985;41:5475–5485. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Schulz B, Boyle C, Draeger S, Rommert AK, Krohn K. Mycol. Res. 2002;106:996–1004. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Schulz B, Sucker J, Aust H-J, Krohn K, Ludewig K, Jones PG, Döring D. Mycol. Res. 1995;99:1007–1015. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Neumann K, Kehraus S, Gütschow M, König GM. Nat. Prod. Commun. 2009;4:347–354. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bettayeb K, Oumata N, Echalier A, Ferandin Y, Endicott JA, Galons H, Meijer L. Oncogene. 2008;27:5797–5807. doi: 10.1038/onc.2008.191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Shimokawa K, Iwase Y, Miwa R, Yamada K, Uemura D. J. Med. Chem. 2008;51:5912–5914. doi: 10.1021/jm800741n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.a) Saroglou V, Karioti A, Demetzos C, Dimas K, Skaltsa H. J. Nat. Prod. 2005;68:1404–1407. doi: 10.1021/np058042u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Monks A, Scudiero D, Skehan P, Shomaker R, Paull K, Vistica D, Hose C. J. Natl. Cancer Inst. 1991;83:661–757. doi: 10.1093/jnci/83.11.757. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.a) Pannecouque C, Daelemans D, De Clercq E. Nat. Protocols. 2008;3:427–434. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2007.517. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Zhan P, Liu X, Fang Z, Pannecouque C, De Clercq E. Bioorg. Med. Chem. 2009;17:6374–6379. doi: 10.1016/j.bmc.2009.07.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Prudêncio M, Rodrigues CD, Ataide R, Mota MM. Cell Microbiol. 2008;10:218–224. doi: 10.1111/j.1462-5822.2007.01032.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kumaki Y, Day CW, Wandersee MK, Schow BP, Madsen JS, Grant D, Roth JP, Smee DF, Blatt LM, Barnard DL. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2008;371:110–113. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2008.04.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Smee DF, Burger RA, Warren RP, Bailey KW, Sidwell RW. Antiviral Chem. Chemother. 1997;8:573–581. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Sidwell RW, Smee DF. Antiv. Res. 2000;48:1–16. doi: 10.1016/s0166-3542(00)00125-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.