Abstract

Background

Cystic fibrosis (CF) and short bowel syndrome (SBS) patients are unable to absorb vitamin D from the diet and thus are frequently found to be severely vitamin D deficient. We evaluated whether a commercial portable ultraviolet (UV) indoor tanning lamp that has a spectral output that mimics natural sunlight could raise circulating 25-hydroxyvitamin D [25(OH)D] levels in subjects with CF and SBS.

Methods

In initial pilot studies, two SBS subjects came to the outpatient clinic twice weekly for 8 weeks for UV light sessions of 6 min each. In a follow-up study, five CF subjects exposed their lower backs in a seated position to the sunlamp at a distance of 14 cm for 5–10 min depending on the skin type five times a week for 8 weeks. Blood samples for 25(OH)D and parathyroid hormone (PTH) measurements were performed at baseline and at the end of the study.

Results

In our study, with two SBS subjects, the indoor lamp increased or maintained circulating 25(OH)D levels during the winter months. We increased the UV lamp frequency and found an improved response in the CF patients. Serum 25(OH)D levels in CF subjects at baseline were 21 ± 3 ng/ml, which increased to 27 ± 4 ng/ml at the end of 8 weeks (P = 0.05). PTH concentration remained largely unchanged in both population groups.

Conclusion

A UV lamp that emits ultraviolet radiation similar to sunlight and thus produces vitamin D3 in the skin is an excellent alternative for CF, and SBS patients who suffer from vitamin D deficiency due to fat malabsorption, especially during the winter months when natural sunlight is unable to produce vitamin D3 in the skin. This UV lamp is widely available for commercial home use and could potentially be prescribed to patients with CF or SBS.

Keywords: cystic fibrosis, short bowel syndrome, tanning, ultraviolet radiation, vitamin D

Vitamin D is an important nutrient for intestinal calcium absorption for optimal skeletal health. Vitamin D can either be ingested from the diet (vitamin D2 or D3) or produced in the skin (D3). Vitamin D (vitamin D2 or D3) absorption from the diet occurs primarily in the duodenum and jejunum (1, 2). Vitamin D3 (cholecalciferol) is the form of vitamin D that can be produced endogenously in the skin following ultraviolet B (UVB) radiation (3). After production in the skin, vitamin D3 is converted to the major circulating form of vitamin D, 25-hydroxyvitamin D3 (25(OH)D3). Circulating 25(OH)D3 is then converted to 1,25-dihydroxyvitamin D3 by the kidney 1-α-hydroxylase to act as a steroid hormone to increase the efficiency of calcium absorption primarily in the duodenum to maintain proper serum calcium levels for skeletal health and other cellular signaling processes (3).

Treatment of vitamin D deficiency in most healthy individuals is accomplished by giving vitamin D2 (ergocalciferol) 50 000 IU once or twice a week for several weeks (4). However, patients with malabsorption as in short-bowel syndrome (SBS) and cystic fibrosis (CF) are not able to absorb vitamin D efficiently and thus have a high prevalence of vitamin D deficiency, leading to osteomalacia and osteoporosis. SBS patients have been given high-dose oral vitamin D supplementation without an improvement in vitamin D status due to poor intestinal absorption of vitamin D (1, 5, 6). CF patients have inefficient vitamin D absorption due to pancreatic exocrine insufficiency resulting in malabsorption of fat-soluble vitamins, including vitamin D. CF subjects absorb approximately 50% less vitamin D compared with what normal subjects absorb, depending on the degree of exocrine insufficiency (7). Current guidelines in CF patients to treat vitamin D deficiency with weekly high-dose ergocalciferol (vitamin D2) have been ineffective (8–10). Despite 50 000 IU of ergocalciferol once a week for a total of 16 weeks in vitamin D-deficient CF patients, all of the patients remained vitamin D deficient (10).

Because patients with fat malabsorption syndromes cannot efficiently absorb vitamin D from the diet, an alternative method to raise vitamin D status, especially during the winter months where vitamin D cannot be made (11), would be by exposing the skin to UVB produced by a device to produce vitamin D3 cutaneously (1, 12). Indoor tanning machines emit the same spectrum UVB radiation as sunlight (13). Studies evaluating indoor tanning beds have demonstrated that 25(OH)D levels can be raised after exposure to lamps that emit UVB (14). Cross-sectional studies have demonstrated that subjects who use an indoor tanning bed at least once a week have higher 25(OH)D levels than control subjects, which correlates with a higher bone mineral density (BMD) (13). Koutkia et al (1) successfully treated vitamin D deficiency, and associated musculoskeletal pains in a subject with SBS with the use of an indoor tanning bed.

In the current study, we sought to evaluate whether a commercially available portable desktop tanning machine could improve vitamin D status in patients with SBS and CF, disorders characterized by chronic malabsorption of fat-soluble vitamins.

Methods

Evaluation of a portable tanning machine to make vitamin D

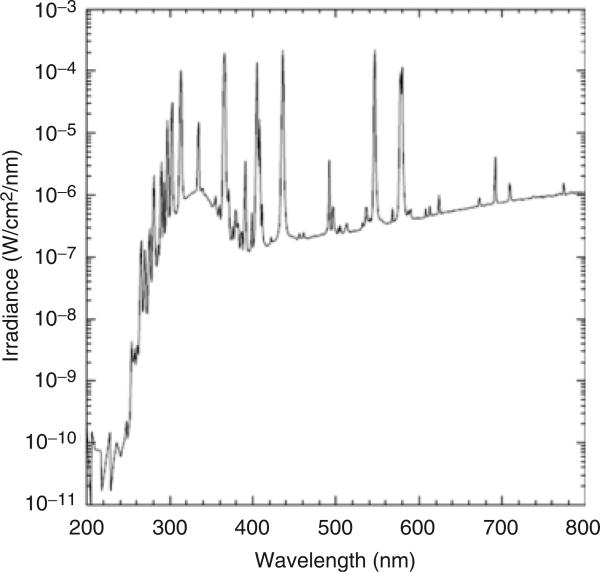

To determine whether we could use a tanning device to improve vitamin D status in patients with malabsorption, we initially tested a commercially available desktop tanning machine to determine whether the UVB radiation emitted from the machine could convert 7-dehydrocholesterol (7-DHC) (pro-vitamin D3), the compound naturally present in skin, to pre-vitamin D3. We obtained the Sperti Del Sol portable tanning machine from KBD Inc. (Crescent Springs, KY, USA). The UVB output of this machine overlaps with the region of UVB necessary for vitamin D production in the skin (290–315 nm) (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Ultraviolet spectrum output of the Sperti Del Sol sunlamp used in the study.

We exposed ampules containing a known quantity of 7-DHC to the machine at several distances and times to determine the quantity of pre-vitamin D conversion from 7-DHC. We determined the resultant amount of vitamin D3 by standard high-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC) methods, as described by Holick et al. (15).

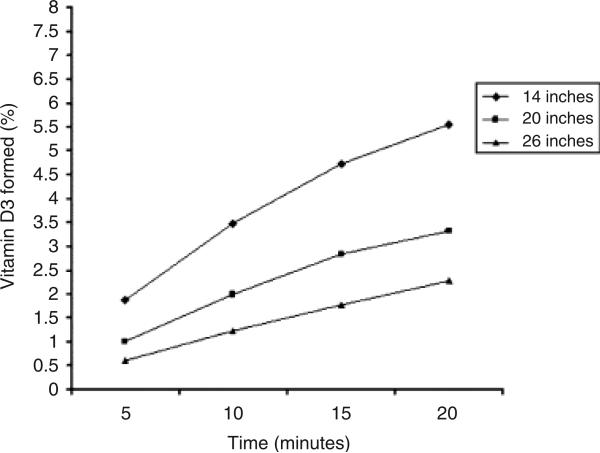

We determined that the portable tanning machine could effectively convert 7-DHC to pre-vitamin D3 (Fig. 2). At several distances and times, from 0.5% to 5.0% of pre-vitamin D3 could be detected in the ampules. Control ampules that had not been exposed to the tanning device did not demonstrate detectable pre-vitamin D3. These data provided necessary preclinical data to proceed with our pilot study to evaluate the use of the portable tanning machine in CF and SBS patients with malabsorption. Based on these data, we developed a protocol to expose patients to UVB light via the tanning machine for up to 10 min at a distance of 14 inches.

Fig. 2.

Percentage of pre-vitamin D3 formed after exposing ampules containing 7-dehydrocholesterol (7-DHC) to a portable tanning machine at several times and distances (◆, 14 inches; ■, 20 inches; ▲, 26 inches). Ampules containing 7-DHC (pro-vitamin D) were exposed to a portable tanning machine at several distances and times to determine the optimal conditions for vitamin D production in the skin. Vitamin D production was optimal at 14 cm from the device and an exposure time between 10 and 15 min.

Evaluation of a tanning machine to improve vitamin D status in two patients with severe SBS

Subjects

We obtained Emory University IRB approval to study the effect of the Sperti Del Sol sunlamp (Cresent Springs, KY, USA) in two SBS subjects with chronic, severe diarrhea and vitamin D insufficiency [25(OH)D <30 ng/ml], who both had failed oral courses of vitamin D therapy to improve vitamin D status. The first subject was a 49-year-old woman with 50 cm of the bowel remaining after massive small bowel and partial colonic resection secondary to mesenteric ischemia. The subject required parenteral nutrition (PN) solution 7 nights/week with 200 IU/day of vitamin D3 to maintain nutritional status. Her left femoral neck bone density was 2.4 standard deviations below the peak density, and she had subjective pain and malaise. The second SBS subject was a 54-year-old woman who had multiple small bowel resections for a strangulated hernia in whom the distal duodenum was anastomosed to the right transverse colon. The subject also required PN solution 7 nights/week with 200 IU/day of vitamin D3 to maintain nutritional status. Like the first subject, she suffered from severe night cramps and bone pains.

Study protocol in SBS patients

The study was conducted in the months from March to May. The two SBS subjects came to the outpatient clinic twice weekly for 8 weeks for the UV light sessions, which were administered by the study team. After baseline blood studies were obtained, both subjects started at an initial exposure time of 3 min from a distance of 14 inches to the exposed skin on the lower back in a seated position; the time was increased by 1 min to reach a target time of 6 min per UV light session in accordance with their skin type (Appendix A). The skin was inspected before and after each session to examine for any burns. Subjects gave a blood sample for 25(OH)D and parathyroid hormone (PTH) determinations every 4 weeks until the end of the study. Descriptive statistical analyses were performed in this pilot study in SBS patients.

Vitamin D status and PTH

Commercially available ELISA kits were used to measure 25(OH)D (IDS Ltd., Fountain Hills, AZ, USA), and intact PTH (Diagnostic Systems Laboratories, Webster, TX, USA) in blood samples at baseline and after 8 weeks of use of the tanning lamp.

Results

The first subject with SBS demonstrated a baseline serum 25(OH)D of 13 ng/ml that increased by 70% to 21 ng/ml at 4 weeks, and plateaued at this level after 8 weeks of UVB therapy. The serum PTH levels in this individual increased slightly from 150 to 165 pg/ml at the end of 8 weeks. There was a subjective reduction in the severity of her night cramps and bone pains. The second SBS subject demonstrated a baseline serum 25(OH)D of 17 ng/ml that increased by 40% to 24 ng/ml at 2 weeks, but then decreased to baseline levels (16 ng/ml) after 8 weeks of study. Her serum PTH levels decreased from 130 to 58 pg/ml at the end of 8 weeks.

Adverse events

Both subjects tolerated the monitored radiation sessions without any adverse events.

Evaluation of a tanning machine to improve vitamin D status during the winter months in subjects with CF Subjects

We obtained Emory University IRB approval to study the effect of the Sperti Del Sol sunlamp in CF patients with documented vitamin D insufficiency. The target population for the study was CF subjects cared for by the Emory Cystic Fibrosis Center (Atlanta, GA). Subjects were recruited by posted advertisements and referral by physicians. Subjects gave written informed consent for participation in the study. We included subjects older than 18 years of age who had documented vitamin D insufficiency [serum 25(OH)D <30 ng/ml] within the last three months, and had a history of gastrointestinal malabsorption documented by requirement of pancreatic enzyme replacement therapy or long-term PN therapy, or who had a skin sensitivity types II–VI (Appendix A). We excluded those subjects who had a history of photosensitivity, a history of active skin disease or any history of skin cancer, who were taking medications that limit sunlight exposure (such as tetracyclines or fluoroquinolones), who were taking more than 1000 IU vitamin D or vitamin D analogs daily orally, who had evidence of liver or kidney failure, who had fair skin type I (Appendix A), who were undergoing tanning sessions or subjects who were pregnant.

Study protocol

Based on the promising, but sub-optimal increase in serum 25(OH)D in these two pilot subjects with severe SBS, we increased the frequency of exposure to the tanning device to five times a week for the same time period of 8 weeks in the subsequent study in CF patients. The study period was from November to February. Subjects had a baseline 24-hour dietary recall and sunlight exposure questionnaire, and a baseline blood sample for the measurement of serum 25(OH)D and PTH. Subjects completed five UV light sessions per week for 8 weeks at home. Goggles for eye protection to be worn during the sessions were given. The target time per session was based on skin type (Appendix A). The subjects were asked to start with 3 min/session and to increase the time by 1 min/week till their target time. Subjects were instructed to expose the skin of the lower back to the tanning machine in a seated position from a distance of 14 in. Subjects came to the outpatient clinic every 2 weeks to for examination of the skin, and blood was drawn at 0 and 8 weeks for serum 25(OH)D and PTH mesurements.

Dietary history

Twenty-four hours of food recall was recorded for the day just before the first visit to the clinic. The dietary questionnaire had food portions that were visually quantified and standardized for the subject quantification. ESHA's The Food Processor SQL Version 9.8 Software was used to analyze the dietary intake.

Vitamin D status and PTH

We used the same commercially available ELISA kits that were used to measure 25(OH)D and intact PTH as in our pilot study of SBS subjects.

Statistical analysis

The results were represented as means ± SEM. The data were analyzed using Microsoft Excel (Office 2000), and Sigma Stat Version 3.0. Differences in the concentrations of serum total 25(OH)D were evaluated using a two-way paired t-test. Intention to treat was used in data analysis.

Results

Subject demographics

A total of eight CF subjects enrolled in the study. Two subjects who failed to report for the second tanning session were excluded. One subject was excluded due to non-compliance of the study protocol. Thus, five CF subjects were included in our analysis (Table 1).

Table 1.

Baseline demographics of cystic fibrosis subjects who underwent UV light therapy five times a week for 8 weeks to improve vitamin D status

| N = 5 | |

|---|---|

| Age (years) | 29.5 ± 3.4 |

| Sex (M/F) | 2/3 |

| FEV (% of predicted) at 0 weeks | 52 ± 13 |

| FEV (% of predicted) at 8 weeks | 50 ± 14 |

| Weight (kg) | 54.6 ± 2.4 |

| Height (cm) | 166 ± 3 |

| Vitamin D supplementation (pills/day)* | 1.0 ± 0.7 |

| Dietary Vitamin D intake (IU/day) | 237 ± 17 |

| Sunlight exposure (min/week) | 250 ± 68 |

One vitamin D pill = 400IU ergocalciferol.

FEV, Forced expiratory vital capacity at 1 s.

Dietary vitamin D intake and supplementation

The mean dietary vitamin D intake averaged 237 IU/day. Three subjects were taking vitamin D supplements containing 400 IU of vitamin D daily, one subject was taking supplements containing 800 IU of vitamin D daily and the last subject was not taking any vitamin D supplementation.

Vitamin D status and PTH concentrations

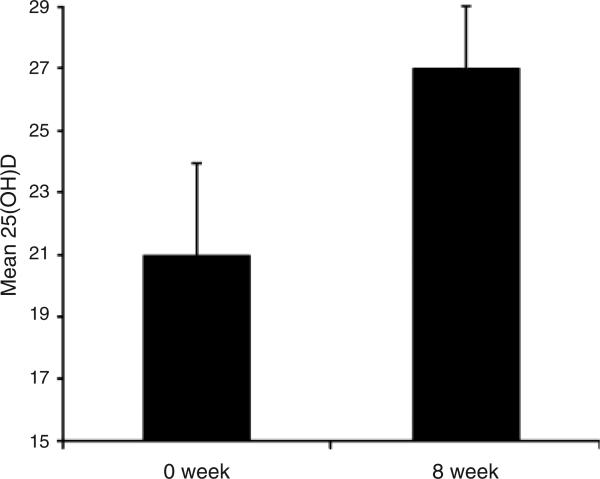

Serum 25(OH)D levels in the five CF subjects at baseline were 21 ± 3 ng/ml, which increased to 27 ± 4 ng/ml at the end of 8 weeks (P = 0.05) (Fig. 3). Four out of five CF subjects had moderate to severe vitamin D deficiency [25(OH)D <20 ng/ml] at the start of the study, while only one out of five was so at the end of 8 weeks. The PTH concentrations remained unchanged during the 8-weeks study period (45 ± 10–43 ± 12 pg/ml).

Fig. 3.

Mean (± SEM) serum 25-hydroxyvitamin D concentration (ng/mL) before and after 8 weeks of UV light to cystic fibrosis (CF) subjects. Serum 25-hydroxyvitamin D [25(OH)D] levels in the five CF subjects at baseline were 21 ± 3 ng/ml, which increased to 27 ± 4 ng/ml at the end of 8 weeks (P = 0.05).

Adverse events

Mild transient erythema occurring after the use of the tanning device was reported by all subjects, but no sunburn or discomfort was reported.

Discussion

This pilot study demonstrates that a portable tanning device emitting UVB could maintain or improve vitamin D status in patients with CF or SBS during the winter months. Studies in SBS patients helped to define the UVB dose chosen for the CF study. In CF subjects, all were vitamin D deficient, despite taking regular vitamin D supplementation, due to malabsorption. During the winter, 8 weeks of the Sperti sunlamp resulted in a 25% increase in serum 25(OH)D concentration, and the prevalence of severe vitamin D deficiency [defined as 25(OH)D <20 ng/ml] decreased from 60% to 20%. All subjects demonstrated an increase in serum 25(OH)D concentrations, which achieved statistical significance. Similar results were found in the early pilot study in two SBS subjects. The use of a desktop tanning unit was well tolerated and no significant adverse events were reported by either group.

Sunlight, in particular UVB between the wavelengths of 290 and 315 nm, is the main source for producing vitamin D in the skin and is the primary source of vitamin D for the body. It is estimated that 90% of the daily body requirements are met by sunlight exposure (16, 17). One minimal erythemal dose (MED) of UVB exposure to 6% of the body surface area is equivalent to the ingestion of 600–1000 IU of vitamin D (18). Thus, exposure of the hands, face and arms two to three times a week is sufficient to meet the daily body vitamin D requirements in most individuals during the spring, summer and fall (18). Owing to the zenith angle of the sun during the winter months, very little UVB penetrates the earth above 351 latitudes, and thus sunlight exposure at this time will not result in sufficient vitamin D production (19, 20). For example, a third of healthy adults living in Boston were demonstrated to be vitamin D deficient at the end of winter (21).

In areas where there is limited sunlight or in situations where patients cannot absorb vitamin D from the diet, phototherapy using UV light has been used to correct vitamin D deficiency. In the early 20th century, mercury arc lamps were used to treat children with rickets in Russia. Indoor beds or tanning devices have been reported to be an effective alternative method to maintain or raise vitamin D status especially during the winter months in individuals with malabsorption (1, 22). Subjects who use an indoor tanning bed at least once a week have 150% higher 25(OH)D levels at the end of winter and higher BMD than matched healthy controls (13). Several other studies have used UVB from artificial sources in raising body vitamin D status (23–28).

Vitamin D insufficiency and metabolic bone disease remains a major health problem in patients with CF. The cause for decreased bone density in CF is multifactorial; however, due to the inability to absorb fat soluble vitamins, vitamin D insufficiency is a major contributing factor (8). Serum 25(OH)D in CF patients is positively correlated with BMD (29). A recent Johns Hopkins Hospital study found 109 out of 134 CF adults in the clinic to be vitamin D deficient [serum 25(OH)D <30 ng/ml], and none of the 33 CF subjects who finished 1 200 000 IU of oral vitamin D2 over 4 months showed correction in their vitamin D status (10). The CF consensus guidelines for bone health suggest the use of UV lamps in subjects who fail to achieve optimal vitamin D status; however, no standard protocols have been established (8). A recent case–control study from Sweden demonstrated that CF subjects exposed to UV lamps one to three times weekly for 6 months showed an increase in circulating 25(OH)D from 20 to 50 ng/ml (27).

One of the weaknesses of our study is that we did not have randomized control subjects during the same months. Our small sample size also limits the power of our data analysis; however, the study subjects were exposed to the tanning light for just 8 weeks, which significantly increased their serum vitamin D levels by 25%. However, the values failed to reach the newly established levels to define vitamin D insufficiency [25(OH)D >32 ng/ml] (30). This suggests that the protocol may need to be extended for a longer time. Also, during this limited timeframe, we failed to show a significant decline in serum PTH concentration. Another limitation was that compliance could not be well assured in our second study with CF subjects because of the use of the tanning device at home.

In summary, we found that a portable tanning device used for tanning could be used to improve vitamin D status in selected individuals with intestinal malabsorption of vitamin D. Eight weeks of exposure to the sunlamp increased circulating 25(OH)D levels by 25% and reduced the prevalence of severe vitamin D deficiency. Further research is needed to determine the optimal duration of UVB exposure and to determine the long-term benefits of correcting vitamin D status by UVB on musculoskeletal health in these at-risk patients.

Acknowledgements

The authors acknowledge the assistance from the staff of the Emory University Cystic Fibrosis Center, Margaret Jenkins, Sandra Huff and Carrie Cutchins. The authors also acknowledge the technical assistance from James Shepherd in the operation of the Sperti Del Sol machine.

Appendix A.

Skin sensitivity types to UVB radiation, and the recommended target tanning time sessions

| Skin type scale* | Target (min/session) |

|---|---|

| Type I: Always burns easily, never tans | – |

| Type II: Always burns easily, tans minimally | 3 |

| Type III: Burns moderately, tans gradually | 6 |

| Type IV: Burns minimally, always tans well | 9 |

| Type V: Rarely burns, tans profusely | 12 |

| Type VI : Never burns, deeply pigmented | 15 |

FDA skin type scale, http://www.fda.gov/cdrh/consumer/tanning.html

Footnotes

Conflicts of interest

Dr. Tangpricha and Dr. Holick received grant support from the Ultraviolet (UV) Light Foundation. The remaining authors report no conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.Koutkia P, Lu Z, Chen TC, Holick MF. Treatment of vitamin D deficiency due to Crohn's disease with tanning bed ultraviolet B radiation. Gastroenterology. 2001;121:1485–1488. doi: 10.1053/gast.2001.29686. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hollander D, Truscott TC. Mechanism and site of small intestinal uptake of vitamin D3 in pharmacological concentrations. Am J Clin Nutr. 1976;29:970–975. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/29.9.970. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Holick MF. McCollum Award Lecture, 1994: vitamin D: new horizons for the 21st century. Am J Clin Nutr. 1994;60:619–630. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/60.4.619. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Malabanan A, Veronikis IE, Holick MF. Redefining vitamin D insufficiency. Lancet. 1998;351:805–806. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(05)78933-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Leichtmann GA, Bengoa JM, Bolt MJ, Sitrin MD. Intestinal absorption of cholecalciferol and 25-hydroxycholecalciferol in patients with both Crohn's disease and intestinal resection. Am J Clin Nutr. 1991;54:548–552. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/54.3.548. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Haderslev KV, Jeppesen PB, Sorensen HA, Mortensen PB, Staun M. Vitamin D status and measurements of markers of bone metabolism in patients with small intestinal resection. Gut. 2003;52:653–658. doi: 10.1136/gut.52.5.653. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lark RK, Lester GE, Ontjes DA, et al. Diminished and erratic absorption of ergocalciferol in adult cystic fibrosis patients. Am J Clin Nutr. 2001;73:602–606. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/73.3.602. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Aris RM, Merkel PA, Bachrach LK, et al. Guide to bone health and disease in cystic fibrosis. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2005;90:1888–1896. doi: 10.1210/jc.2004-1629. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Haworth CS, Jones AM, Adams JE, Selby PL, Webb AK. Randomised double blind placebo controlled trial investigating the effect of calcium and vitamin D supplementation on bone mineral density and bone metabolism in adult patients with cystic fibrosis. J Cyst Fibros. 2004;3:233–236. doi: 10.1016/j.jcf.2004.08.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Boyle MP, Noschese ML, Watts SL, Davis ME, Stenner SE, Lechtzin N. Failure of high-dose ergocalciferol to correct vitamin D deficiency in adults with cystic fibrosis. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2005;172:212–217. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200403-387OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Webb AR, Kline L, Holick MF. Influence of season and latitude on the cutaneous synthesis of vitamin D3: exposure to winter sunlight in Boston and Edmonton will not promote vitamin D3 synthesis in human skin. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 1988;67:373–378. doi: 10.1210/jcem-67-2-373. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sayre RM, Dowdy JC, Shepherd JG. Reintroduction of a classic vitamin D ultraviolet source. J Steroid Biochem Mol Biol. 2007;103:686–688. doi: 10.1016/j.jsbmb.2006.12.062. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Tangpricha V, Turner A, Spina C, Decastro S, Chen TC, Holick MF. Tanning is associated with optimal vitamin D status (serum 25-hydroxyvitamin D concentration) and higher bone mineral density. Am J Clin Nutr. 2004;80:1645–1649. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/80.6.1645. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Devgun MS, Johnson BE, Paterson CR. Tanning, protection against sunburn and vitamin D formation with a UV-A ‘sunbed’. Br J Dermatol. 1982;107:275–284. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2133.1982.tb00357.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Holick MF, MacLaughlin JA, Clark MB, et al. Photosynthesis of previtamin D3 in human skin and the physiologic consequences. Science. 1980;210:203–205. doi: 10.1126/science.6251551. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Glerup H, Mikkelsen K, Poulsen L, et al. Commonly recommended daily intake of vitamin D is not sufficient if sunlight exposure is limited. J Internal Med. 2000;247:260–268. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2796.2000.00595.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Holick MF. Vitamin D: a millenium perspective. J Cell Biochem. 2003;88:296–307. doi: 10.1002/jcb.10338. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Holick MF. Sunlight “D”ilemma: risk of skin cancer or bone disease and muscle weakness. Lancet. 2001;357:4–6. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(00)03560-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Webb AR, Kline L, Holick MF. Influence of season and latitude on the cutaneous synthesis of vitamin D3: exposure to winter sunlight in Boston and Edmonton will not promote vitamin D3 synthesis in human skin. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 1988;67:373–378. doi: 10.1210/jcem-67-2-373. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Utiger Robert D. The Need for More Vitamin D. N Engl J Med. 1998;338:828–829. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199803193381209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Tangpricha V, Pearce EN, Chen TC, Holick MF. Vitamin D insufficiency among free-living healthy young adults. Am J Med. 2002;112:659–662. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9343(02)01091-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Grant WB, Holick MF. Benefits and requirements of vitamin D for optimal health: a review. Altern Med Rev. 2005;10:94–111. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Falkenbach A, Sedlmeyer A, Unkelbach U. UVB radiation and its role in the treatment of postmenopausal women with osteoporosis. Int J Biometeorol. 1998;41:128–131. doi: 10.1007/s004840050065. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Chel VG, Ooms ME, Popp-Snijders C, et al. Ultraviolet irradiation corrects vitamin D deficiency and suppresses secondary hyperparathyroidism in the elderly. J Bone Miner Res. 1998;13:1238–1242. doi: 10.1359/jbmr.1998.13.8.1238. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Chuck A, Todd J, Diffey B. Subliminal ultraviolet-B irradiation for the prevention of vitamin D deficiency in the elderly: a feasibility study. Photodermatol Photoimmunol Photomed. 2001;17:168–171. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-0781.2001.170405.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Prystowsky JH, Muzio PJ, Sevran S, Clemens TL. Effect of UVB phototherapy and oral calcitriol (1,25-dihydroxyvitamin D3) on vitamin D photosynthesis in patients with psoriasis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1996;35(Part 1):690–695. doi: 10.1016/s0190-9622(96)90722-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Gronowitz E, Larko O, Gilljam M, et al. Ultraviolet B radiation improves serum levels of vitamin D in patients with cystic fibrosis. Acta Paediatr. 2005;94:547–552. doi: 10.1111/j.1651-2227.2005.tb01937.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Marcinowska-Suchowierska E, Lorenc R, Brzozowski R. Vitamin D deficiency in patients with chronic gastrointestinal disorders: response to UVB exposure. Mater Med Pol. 1994;26:59–63. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Donovan DS, Papadopoulos A, Staron RB, et al. Bone mass and vitamin D deficiency in adults with advanced cystic fibrosis lung disease. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 1998;157(Part 1):1892–1899. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.157.6.9712089. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hollis BW, Wagner CL. Normal serum vitamin D levels. N Engl J Med. 2005;352:515–516. doi: 10.1056/NEJM200502033520521. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]