Abstract

Neuropilin-1 (NRP1) functions as a coreceptor through interaction with plexin A1 or vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) receptor during neuronal development and angiogenesis. NRP1 potentiates the signaling pathways stimulated by semaphorin 3A and VEGF-A in neuronal and endothelial cells, respectively. In this study, we investigate the role of tumor cell-expressed NRP1 in glioma progression. Analyses of human glioma specimens (WHO grade I–IV tumors) revealed a significant correlation of NRP1 expression with glioma progression. In tumor xenografts, overexpression of NRP1 by U87MG gliomas strongly promoted tumor growth and angiogenesis. Overexpression of NRP1 by U87MG cells stimulated cell survival through the enhancement of autocrine hepatocyte growth factor/scatter factor (HGF/SF)/c-Met signaling. NRP1 not only potentiated the activity of endogenous HGF/SF on glioma cell survival but also enhanced HGF/SF-promoted cell proliferation. Inhibition of HGF/SF, c-Met and NRP1 abrogated NRP1-potentiated autocrine HGF/SF stimulation. Furthermore, increased phosphorylation of c-Met correlated with glioma progression in human glioma biopsies in which NRP1 is upregulated and in U87MG NRP1-overexpressing tumors. Together, these data suggest that tumor cell-expressed NRP1 promotes glioma progression through potentiating the activity of the HGF/SF autocrine c-Met signaling pathway, in addition to enhancing angiogenesis, suggesting a novel mechanism of NRP1 in promoting human glioma progression.

Keywords: neuropilin-1, HGF/SF, c-Met, glioma

Introduction

Neuropilin-1 (NRP1) is a type I cell surface co-receptor that plays important roles in the development of the nervous system and angiogenesis (Bagri and Tessier-Lavigne, 2002). During neuronal development, NRP1-mediated signal transduction requires the formation of a functional semaphorin (Sema) 3A-NRP1-plexin A1 complex, which inhibits axonal guidance signals to the projecting neurons (Bagri and Tessier-Lavigne, 2002). In endothelial cells, NRP1 enhances the interaction of heparin-binding vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF)165 with its receptors (VEGFRs) and modulates VEGF-stimulated angiogenesis. Elevated expression of NRP1 was also found in tumor cells in various types of human cancers (Klagsbrun et al., 2002). Overexpression of NRP1 in prostate and colon cancer cells enhances angiogenesis and tumor growth in animals (Miao et al., 2000; Parikh et al., 2004), whereas expression of an antagonist of NRP1 inhibited vessel growth and tumor expansion (Gagnon et al., 2000).

Hepatocyte growth factor/scatter factor (HGF/SF) modulates various cellular functions such as proliferation, migration and morphogenesis through its cognate surface receptor c-Met (Gao and Vande Woude, 2005). Activation of the HGF/SF/c-Met signaling pathway correlates with the malignancy of human gliomas (Abounader and Laterra, 2005). Overexpression of HGF/SF in glioma cells resulted in enhanced tumorigenicity and growth in vivo (Laterra et al., 1997). Inhibition of endogenous HGF/SF and c-Met in human cancer cells, including gliomas, reversed their malignant phenotype (Abounader et al., 2002). Additionally, the activation of signaling molecules such as extracellular signal-regulated kinase (ERK) and Bcl-2 antagonist of cell death (Bad) is involved in the HGF/SF/c-Met pathway in cancer cells (Abounader and Laterra, 2005). NRP1 was recently demonstrated to interact directly with a subset of heparin-binding growth factors, such as fibroblast growth factor-2 (FGF-2), FGF-4 and HGF/SF and potentiates FGF-2 stimulation of endothelial cells (West et al., 2005), suggesting that NRP1 expression in glioma cells may augment HGF/SF/c-Met stimulation of tumor progression through an autocrine loop.

In this study, we investigated the roles of tumor cell-expressed NRP1 in human glioma progression. We show that upregulated NRP1 is primarily expressed in tumor cells, and NRP1 expression correlates with tumor progression in clinical glioma specimens. We demonstrate that NRP1 expression promotes glioma growth and survival in vitro and in vivo through an autocrine HGF/SF/c-Met signaling pathway involving activation of c-Met, ERK and Bad, thus suggesting a novel mechanism of NRP1 expression in promoting cancer cell survival and proliferation.

Results

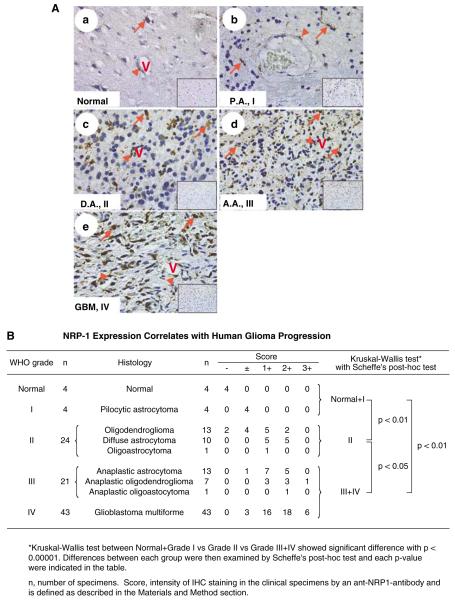

Upregulation of NRP1 is correlated with the malignancy of human astrocytic tumors

To determine the association of NRP1 expression with glioma progression, we performed immunohistochemistry (IHC) analyses on a total of 92 human glioma specimens and four normal human brain biopsies using three well-characterized anti-NRP1 antibodies (Ding et al., 2000) and isotype matched IgGs as negative controls that all showed no staining (see the insets in Figure 1A). As shown in Figure 1Aa, in all four normal brain tissues analysed, weak immunoactivity for the anti-NRP1 antibody was detected in neurons (red arrow) or cells within a blood vessel (arrowhead). In four pilocytic astrocytoma specimens (P.A., WHO grade I), NRP1 was weakly stained in a few tumor cells (Figure 1Ab, arrows) and vessels (panel b, arrowhead). In 24 WHO grade II gliomas, NRP1 protein was detected in tumor cells (panel c, arrows) and vessels (panel c, arrowhead). In 21 WHO grade III glioma biopsies, a greater intensity of NRP1 staining was detected in tumor cells (Figure 1Ad, arrows). In 43 WHO grade IV glioblastoma multiforme (GBM) specimens, high expression of NRP1 was found in tumor cells (Figure 1Ae, arrows). In general, no increase in staining for NRP1 protein was found in hypoxic/pseudopalisading regions, but heterogeneous staining for NRP1 expression was seen within the gliomas. As summarized in Figure 1B and Supplementary Table S1 (Supplementary Material), statistical analyses of our IHC data revealed a significant correlation between NRP1 expression and human glioma progression. There was a significant difference in IHC staining for NRP1 among the three groups as well as a correlation between NRP1 expression and the malignancy of human glioma (Figure 1B).

Figure 1.

NRP1 expression correlates with human glioma progression. (A) IHC of paraffin sections of normal human brain (panel a), P.A. (WHO grade I, panel b), diffuse astrocytoma (D.A., grade II, panel c), anaplastic astrocytoma (A.A., grade III, panel d) and GBM (grade IV, panel e) tissue. Insets in panels a–e are the isotype-matched IgG control staining of identical areas. Arrows indicate neurons (a) or tumor cells (b to e) that are positive for NRP1. Arrowheads indicate endothelial cells in tumor-associated vessels that express NRP1. Results are representative of three independent experiments. Original magnification: ×400. (B) Statistical analyses. A total of 92 individual primary tumor specimens (WHO grade I–IV) and four normal human brain biopsies were analysed.

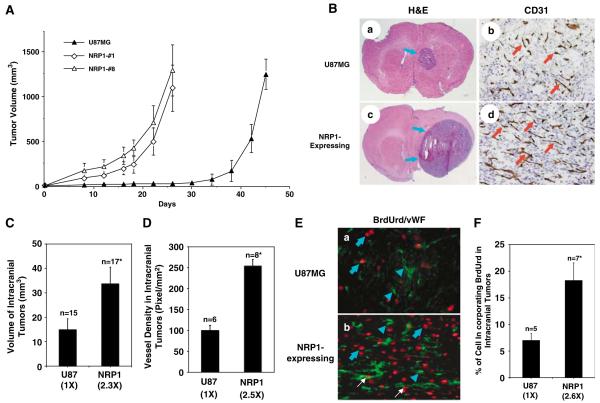

Overexpression of NRP1 in U87MG xenografts promotes tumor growth and angiogenesis in vivo

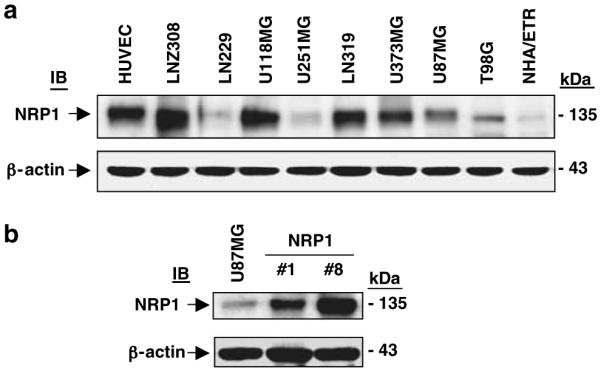

To further investigate whether upregulation of NRP1 by glioma cells promotes tumor progression, we first examined expression of NRP1 in human glioma cell lines by immunoblot (IB) analyses. As shown in Figure 2a, NRP1 protein was detected at various levels in all glioma cell lines examined. As U87MG cells express NRP1 at a relatively low level and are highly tumorigenic in mice (Hu et al., 2003), we utilized this cell line to stably overexpress NRP1. Among various U87MG cell clones that stably express NRP1, we chose two cell clones, U87MG/NRP1-no. 1 and U87MG/NRP1-no. 8, that expressed exogenous NRP1 at medium (NRP1-no. 1) or high levels (NRP1-no. 8) compared with U87MG (Figure 2b) or LacZ (see below) cells for further studies. Next, we separately implanted U87MG and NRP1 cells into the flank or the brain of nude mice. On the 26th day post-implantation, inoculation of NRP1 cells into the flank resulted in formation of tumors with an average volume of 1205±307 mm3, whereas mice that received U87MG or LacZ cells (Guo et al., 2001) developed tumors with similar volumes in 45 days (Figure 3A). In the brain, mice receiving NRP1 cells developed tumors with a volume of 34±6.8 mm3 in 25±3 days (n = 17) (Figure 3Bc, d and 3C), whereas mice inoculated with U87MG or LacZ cells developed tumors of 15±4.5 mm3 in the same period of time (n = 15) (Figure 3Ba, b and 3C). Afterwards, we stained the brain tumor tissue using anti-CD31 (Figure 3Bb and d) and anti-bromodeoxyuridine (BrdUrd) plus anti-von Willebrand factor (vWF) antibodies (Figure 3E). We found that NRP1 intracranial tumors had a 2.5-fold increase in vessel density (Figure 3D) and a 2.6-fold increase in BrdUrd incorporation in the tumor cells when compared with U87MG tumors (Figure 3F).

Figure 2.

Overexpression of NRP1 in U87MG glioma cells. IB analyses of HUVEC, NHA/ETR and various glioma cell lines (a) or U87MG and NRP1-no. 1 and NRP1-no. 8 cells (b) using a polyclonal anti-NRP1 antibody (C-18). β-Actin was used as a loading control. Similar results were also obtained using a polyclonal anti-NRP1 antibody (NP1ECD1A). Results are representative of three independent experiments.

Figure 3.

Overexpression of NRP1 in U87MG cells promotes tumor growth and angiogenesis. (A) Growth kinetics of U87MG or NRP1 tumors at subcutaneous sites. Tumor volume was estimated (volume = (a2 × b)/2, a<b) using a caliper at the indicated times. Data are shown as mean±s.d. (B) Tumorigenicity and angiogenesis of U87MG brain tumors. IHC analyses are shown for U87MG (panels a and b) or NRP1 (c and d) gliomas. Panels a and c are brain sections stained with hematoxylin and eosin (H&E). Panels b and d show CD31 staining for tumor vessels. Arrows in a and c, tumor mass. Arrows in b and d, blood vessels. Five to eight individual tumor samples of each group from each in vivo experiment were analysed. Original magnification: panels a and c, ×12.5; b and d, ×200. (C) and (D) Quantitative analyses of tumorigenesis and angiogenesis in various intracranial tumors. Data are means±s.d. Numbers in parentheses, the difference in fold between U87MG and NRP1 gliomas. (E) and (F) Cell proliferation of various intracranial gliomas. (E) IHC staining of U87MG brain tumors with a monoclonal anti-BrdUrd antibody (red) together with a polyclonal anti-vWF antibody (green). Blue arrows, proliferative nuclei in tumor cells. White arrows, proliferative nuclei of blood vessels. Blue arrowheads, vWF staining of vessels. Three to five serial sections from five to seven individual samples of each tumor type were analysed. Original magnification: ×400. (F) Quantitative analyses of cellular BrdUrd incorporation in U87MG and U87MG/NRP1 tumors. Numbers in parentheses, the difference in fold between U87MG/NRP1 and parental U87MG gliomas. Results in (A–E) are representative of three independent experiments.

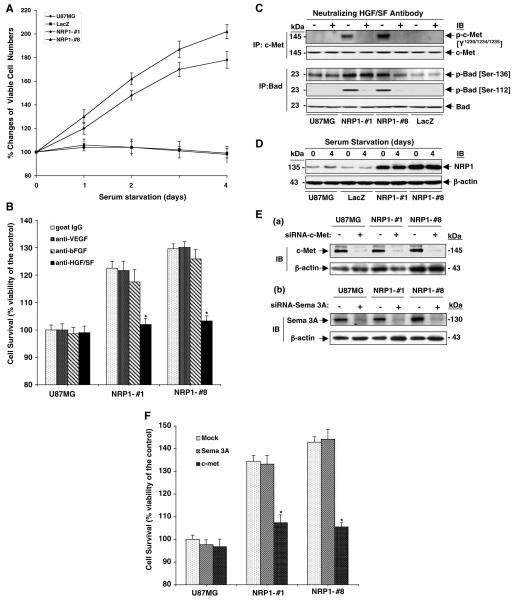

NRP1 promotes U87MG cell growth through enhancing autocrine HGF/SF/c-Met signaling

Our results show that overexpression of NRP1 by glioma cells enhances tumor cell proliferation in vivo, which could possibly be due to NPR1-modulated autocrine intracellular signaling stimulation in glioma cells or caused indirectly by an increase in angiogenesis. To distinguish these possibilities, we performed a trypan blue vital dye exclusion assay. NRP1 overexpression did not significantly affect NRP1 cell growth compared with U87MG or LacZ cells when cultured in medium containing 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS) (data not shown). However, as shown in Figure 4A, in the absence of serum, NRP1 cells showed a 1.8-fold increase in cell survival, whereas U87MG or LacZ cells demonstrated a slight decrease of cell survival in a 4-day culture, suggesting that autocrine signaling through NRP1 promotes cell survival in these glioma cells.

Figure 4.

NRP1 promotes survival of U87MG cells by enhancing autocrine HGF/SF/c-Met signaling. (A) Overexpression of NRP1 promotes U87MG cell survival. Data of cell survival assays are shown as mean±s.d. (B) Inhibition of HGF/SF, but not FGF-2 or VEGF, suppresses NRP1-promoted U87MG cell survival. Data of cell survival assays are shown as mean±s.d. (C) Inhibition of tumor cell-derived HGF/SF, but not VEGF or FGF-2, suppresses NRP1-potentiated activation of c-Met and Bad. IP and IB analyses of various U87MG cells treated with or without the HGF/SF neutralizing antibody. (D) Serum starvation did not alter NRP1 expression in U87MG, LacZ and NRP1 cells. IB analyses of various cell lysates under the same conditions as in (A). (E) and (F) Inhibition of endogenous c-Met but not Sema 3A attenuates NRP1-potentiated U87MG cell viability. (E) Suppression of endogenous c-Met and Sema 3A by siRNA. IB analyses of c-Met and Sema 3A proteins in various U87MG cells. (F) Cell survival assays of siRNA-transfected U87MG and NRP1 cells. Data are shown as mean±s.d. In (B–D), c-Met, Bad and β-actin were used as loading controls. Results in (A–F) are representative of three independent experiments.

A recent study demonstrated NRP1 also interacts with several heparin-binding growth factors, such as FGF-2, FGF-4 and HGF/SF, and potentiates the growth stimulatory activity of FGF-2 on endothelial cells (West et al., 2005). As HGF/SF and FGF-2 were shown to stimulate cell growth through receptor-mediated autocrine signaling in glioma cells (Abounader and Laterra, 2005), we performed enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) and determined whether the autocrine signaling activities of these growth factors were involved in the NRP1-stimulated U87MG cell survival and growth. In a 48-h cell culture, U87MG, LacZ and NRP1 cells secreted VEGF (30±3.6 ng/ml/106 cells), FGF-2 (14±2.1 pg/ml/106 cells) and HGF/SF (400±45 pg/ml/106 cells) into serum-free medium at similar levels. A neutralizing anti-HGF/SF antibody abolished the effect of NRP1-enhanced U87MG cell survival, whereas neutralizing anti-FGF-2 and anti-VEGF antibodies had little or no effect on cell survival of U87MG and NRP1 cells (Figure 4B).

To investigate whether the HGF/SF/c-Met signaling pathway mediates NRP1 stimulation of glioma cells, we examined the expression and tyrosine phosphorylation of c-Met in U87MG and NRP1 cells in the absence or presence of the HGF/SF neutralizing antibody. As shown in Figure 4C, in the absence of serum, expression of endogenous c-Met was not enhanced by NRP1 overexpression, but tyrosine phosphorylation of c-Met was stimulated in NRP1 but not U87MG or LacZ cells. When the HGF/SF neutralizing antibody was included in the cell culture, the NRP1-induced phosphorylation of c-Met was diminished. As U87MG, LacZ and NRP1 cells secrete low levels of endogenous HGF/SF in the serum-free CM (400±45 pg/ml/106 cells) and no inhibitory effect of the neutralizing anti-HGF/SF on U87MG parental cell survival (Figure 4B) was seen, we reasoned that the HGF/SF/c-Met autocrine signaling pathway was not activated due to low levels of the endogenous HGF/SF in U87MG or LacZ cells. Furthermore, NRP1 overexpression in U87MG cells potentiated HGF/SF/c-Met autocrine signaling by activating a downstream target, Bad, an antiapoptotic molecule (Abounader and Laterra, 2005) (Figure 4C). Phosphorylation of Bad at Ser-112 was induced by NRP1 overexpression, but only a slight enhancement occurred on the constitutively phosphorylated Ser-136 of Bad. Additionally, a 4-day culture in serum-free medium did not alter the expression levels of NRP1 in U87MG, LacZ or NRP1-expressing cells (Figure 4D).

Although U87MG cells are deficient in plexin A1 and VEGFR-2, Sema 3A, a cognate ligand for NRP1, is expressed in U87MG cells (Rieger et al., 2003). Thus, we tested a specific knockdown of Sema 3A by siRNA to examine the effects of endogenous Sema 3A on NRP1-enhanced U87MG cell growth. As shown in Figure 4E, endogenous c-Met (panel a) and Sema 3A (panel b) were considerably suppressed compared with the control siRNA-transfected cells. Reduced expression of c-Met, but not Sema 3A, in NRP1 cells significantly abolished the NRP1-enhanced U87MG cell survival (Figure 4F).

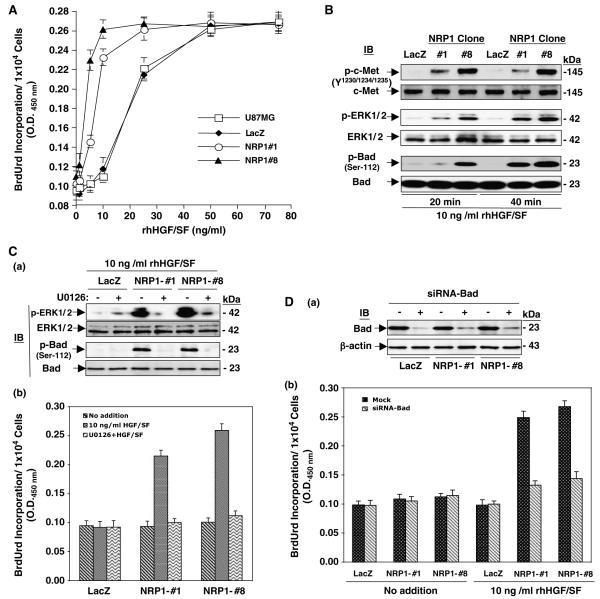

NRP1 potentiates glioma cell proliferation in response to exogenous HGF/SF

We assessed whether NRP1 overexpression could potentiate stimulation of glioma cell proliferation by exogenous HGF/SF using a BrdUrd incorporation assay. As shown in Figure 5A, in the absence of recombinant human (rh) HGF/SF, the basal level of BrdUrd incorporation in NRP1-no. 1 and -no. 8 cells was similar to that in U87MG and LacZ cells. When cells were treated with 5 or 10 ng/ml of rhHGF/SF, a significant increase in BrdUrd incorporation was found in NRP1-no. 1 and -no. 8 cells compared with U87MG and LacZ cells, whereas stimulation by 25 ng/ml rhHGF/SF markedly enhanced BrdUrd incorporation in U87MG and LacZ cells. Further increases of rhHGF/SF (50 or 75 ng/ml) had no further augmentation of BrdUrd incorporation in U87MG, LacZ and NRP1 cells. Also, NRP1-potentiated cell proliferation was proportional to the level of exogenous NRP1 expression in the glioma cells when comparing the BrdUrd incorporation level in NRP1-no. 8 cells (higher level of exogenous NRP1) to NRP1-no. 1 cells (lower level of NRP1 expression, Figure 2b).

Figure 5.

NRP1 expression potentiates HGF/SF stimulation of cell proliferation mediated by c-Met signaling. (A) Expression of NRP1 in U87MG cells potentiates cell proliferation in response to a low dose of HGF/SF stimulation. Data of BrdUrd incorporation in U87MG, LacZ, NRP1-no. 1, and NRP1-no. 8 cells are shown as mean±s.d. (B) IB analyses of NRP1-potentiated HGF/SF stimulation of phosphorylation on c-Met, ERK1/2 and Bad in various U87MG cells. (C) U0126 attenuated NRP1-potentiated HGF/SF stimulation of phosphorylation on ERK1/2 and Bad (panel a, IB analyses) and cell proliferation in various U87MG cells (panel b, BrdUrd incorporation assays; data are shown as mean±s.d.). (D) Knockdown of Bad by siRNA (panel a, IB analyses) attenuates NRP1-potentiated HGF/SF stimulation of cell proliferation in various U87MG cells (panel b, data are shown as mean±s.d.). In (B–D), c-Met, ERK1/2, Bad and β-actin were used as loading controls. Results in (A) to (D) are representative of three independent experiments.

Next, we assessed the activation of c-Met and two of its downstream effectors, ERK and Bad. As shown in Figure 5B, when cells were treated with 10 ng/ml rhHGF/SF for 20 or 40 min, phosphorylation of ERK1/2 and Bad at Ser-112 was evident in NRP1-expressing cells but not in LacZ cells. Moreover, treatment with 25 μmol/l U0126, a specific inhibitor for ERK, inhibited HGF/SF-stimulated phosphorylation of ERK and Bad as well as BrdUrd incorporation in NRP1 cells but not in LacZ cells (Figure 5Ca and b). To a similar extent, suppression of Bad protein expression in these cells by a specific siRNA (Figure 5Da) also significantly attenuated HGF/SF-stimulated BrdUrd incorporation in NRP1 cells but had no effect on LacZ cells or untreated cells (Figure 5Db).

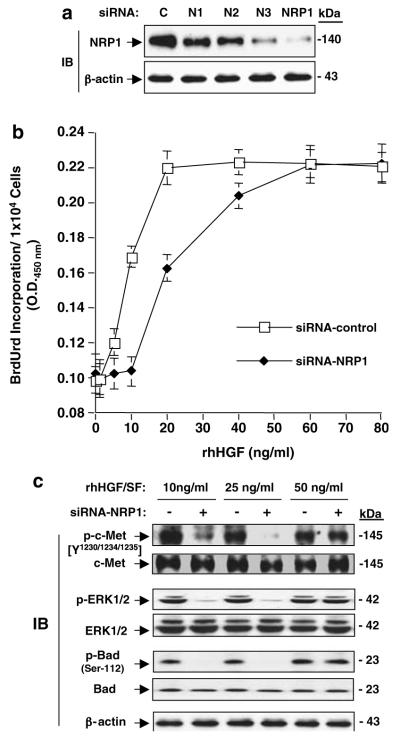

To further confirm the critical role of NRP1 expression on potentiation of HGF/SF/c-Met signaling, we determined the effects of endogenous NRP1 on cell growth in LNZ-308 glioma cells, as LNZ-308 cells express endogenous NRP1 at high levels (Figure 2a) and no endogenous HGF/SF protein was detected by ELISA in serum-free CM (data not shown). As shown in Figure 6a, three individual siRNAs for NRP1 (N1, N2 and N3) suppressed endogenous NRP1 protein at various levels in LNZ-308 cells, whereas a pool of these three siRNAs for NRP1 (N1:N2:N3 = 1:1:1) considerably suppressed endogenous NRP1 protein. When control siRNA-transfected LNZ-308 cells were stimulated with rhHGF/SF, BrdUrd incorporation increased by 1.6-fold in response to 10 ng/ml of rhHGF/SF and reached a peak when 20 ng/ml HGF/SF was used (Figure 6b). Stimulation by HGF/SF on LNZ-308 cells at higher concentrations (60 and 80 ng/ml) had no further effect (Figure 6b). Importantly, when endogenous NRP1 expression was inhibited using siRNA, HGF/SF-stimulated BrdUrd incorporation at low concentrations (10 and 20 ng/ml) was significantly attenuated.

Figure 6.

Inhibition of endogenous NRP1 attenuated HGF/SF stimulation of cell proliferation and HGF/SF/c-Met signaling in LNZ-308 glioma cells. (a) Inhibition of endogenous NRP1 by NRP1/siRNA in LNZ-308 cells detected by IB analyses. C, control siRNA. N1, N2 and N3, individual siRNAs for NRP1. NRP1, a pool of all three siRNAs of N1, N2 and N3. β-Actin was used as a loading control. (b) Inhibition of endogenous NRP1 in LNZ-308 cells using siRNA-attenuated rhHGF/SF stimulation of cell proliferation. Data of BrdUrd incorporation of siRNA-transfected LnZ-308 cells are shown as mean±s.d. (c) Inhibition of endogenous NRP1 in LNZ-308 cells using siRNA-suppressed HGF/SF stimulation of c-Met signaling detected by IB analyses. c-Met, ERK1/2 Bad and β-actin were used as loading controls. Results in (a–c) are representative of three independent experiments.

Next, we examined activation of the HGF/SF/c-Met signaling pathway in various siRNA-transfected LNZ-308 cells in response to HGF/SF stimulation. As shown in Figure 6c, HGF/SF stimulation at 10, 25 and 50 ng/ml induces phosphorylation of c-Met, Erk1/2 and Bad. When NRP1 expression was suppressed using siRNA, the activation by HGF/SF at 10 and 25 ng/ml on c-Met, ERK1/2 and Bad was diminished. No inhibitory effect on HGF/SF stimulation was seen when NRP1 siRNA-transfected LNZ-308 cells were treated with 50 ng/ml HGF/SF.

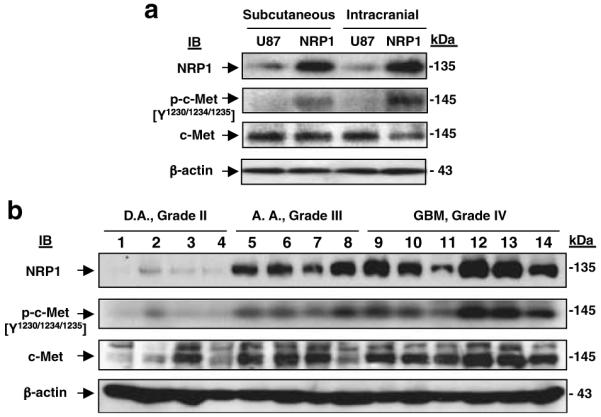

NRP1 enhances HGF/SF/Met signaling in human glioma

Next, we sought to determine whether activation of c-Met also occurred in NRP1-expressing tumors in vivo. We extracted tissue lysates from U87MG and NRP1 tumors and performed IB analysis. As shown in Figure 7a, NRP1 overexpression did not increase c-Met expression in the NRP1 tumors. However, increased phosphorylation of c-Met was detected in the tissue lysates of NRP1 tumors compared with the parental tumors established at subcutaneous and orthotopic sites. Finally, we examined whether increased expression of NRP1 and c-Met phosphorylation correlates with glioma progression in 14 primary human glioma tissue samples by IB analyses. As shown in Figure 7b, c-Met was detected at various levels in all of the glioma tissues, whereas upregulation of NRP1 expression was seen primarily in high-grade tumors (grades III and IV). Importantly, c-Met phosphorylation was also increased in high-grade gliomas, mostly in grade IV GBM specimens, correlating with the expression profile of NRP1 in these clinical samples.

Figure 7.

Upregulation of NRP1 correlates with the activation of c-Met in U87MG tumor xenografts and in high-grade human glioma specimens. (a) Overexpression of NRP1 in U87MG xenografts resulted in activation of c-Met in the established tumors. IB analyses of U87MG and NRP1 xenografted tumors. β-Actin was used as a loading control. (b) Upregulation of NRP1 expression correlates with activation of c-Met during glioma progression. IB analyses of 14 frozen primary human glioma specimens. c-Met and β-actin were used as loading controls. Results are representative of three independent experiments.

Discussion

The role of NRP1 in human tumor progression has been studied in various cancer model systems. Upregulation of NRP1 was found not only in endothelia but also in tumor cells in various types of primary human cancer specimens (Ding et al., 2000; Akagi et al., 2003). Overexpression of NRP1 in tumor cells has been shown to promote tumor growth and angiogenesis in xenograft models and cell survival in cancer cells. In these reports, NRP1 stimulation of tumor progression was primarily attributed to VEGF-dependent pathways (Miao et al., 2000; Bachelder et al., 2003). This study provides new evidence that glioma cell-expressed NRP1 promotes tumor progression through potentiating the HGF/SF/c-Met signaling pathway. We show in primary human glioma specimens that upregulation of tumor cell-expressed NRP1 correlates with glioma progression and increased activation of c-Met in these clinical tumor samples. We demonstrated that overexpression of NRP1 by U87MG glioma cells enhanced tumor growth in mice through potentiating HGF/SF/c-Met activity stimulating tumor cell proliferation in mice. NRP1 potentiated the autocrine HGF/SF/c-Met signaling pathway in response to low concentrations of HGF/SF in vitro, and NRP1 expression is also correlated with c-Met activation in U87MG tumors that overexpress NRP1. Conversely, inhibition of tumor cell-derived HGF/SF, but not FGF-2 or VEGF, by neutralizing antibodies and of endogenous c-Met, but not Sema 3A, by specific siRNAs attenuates HGF/SF/c-Met signaling and glioma cell viability. Furthermore, suppression of endogenous NRP1 in LNZ-308 cells abolishes exogenous HGF/SF stimulation of c-Met-mediated signaling in the tumor cells at lower concentrations. Our results corroborate a recent study showing that overexpression of NRP1 in human pancreatic cancer cells resulted in constitutive activation of mitogen-activated protein kinase signaling (Wey et al., 2005). A plausible mechanism of NRP1 stimulation of tumor progression in our study and the pancreatic cancer model is that NRP1 enhances endogenous signaling modulating tumor cell function independent of VEGF. Our results of NRP1 potentiation of the HGF/SF/c-Met signaling pathway in glioma cells agree with another recent study showing that that NRP1 not only interacts directly with multiple heparin-binding growth factors, such as FGF-2, FGF-4 and HGF/SF, but also potentiates stimulation of FGF-2 on endothelial cells (West et al., 2005). In addition, the increased sensitivity to HGF/SF/c-Met signaling by endogenously expressed NRP1 in glioma cells is analogous to the increase in sensitivity to FGF-2 caused by the addition of a soluble NRP1 dimer to endothelial cells in the aforementioned study. Expression of NRP1 in various cell types may sensitize the cells to their microenvironments, thereby potentiating the corresponding intracellular signaling critical for cellular function.

Increased expression of NRP1 has been detected in tumor cells in clinical glioma samples, suggesting a link between NRP1 expression and glioma malignancy (Ding et al., 2000). Our results further elaborate on these observations. By analysing a total of 92 primary human glioma specimens, we show that upregulation of NRP1 in tumor cells correlates with glioma progression. In U87MG tumor xenografts, overexpression of NRP1 markedly stimulated angiogenesis at both anatomic sites (Figure 3). Significant stimulation of vessel growth by tumor cell–expressed NRP1 in our U87MG xenografts and in prostate and colon cancer models (Miao et al., 2000) led to a hypothesis that tumor cell-expressed NRP1 stimulates vessel growth through a juxtacrine mechanism that forms a complex of NRP1 (in tumor cells), VEGF within the tumor microenvironment (intercellular) and VEGFR-2 (in endothelial cells), thus potentiating VEGF activity that enhances angiogenesis and tumor growth (Klagsbrun et al., 2002). However, it is difficult to dissect the NRP1-stimulated juxtacrine signaling in harvested tumor tissues. Nonetheless, these data and the aforementioned studies suggest a far wider spectrum of activity of NRP1 in promoting tumor progression than is currently appreciated.

In summary, this study provides a novel mechanism that expression of NRP1 in human glioma cells promotes glioma progression through potentiating the activity of HGF/SF/c-Met autocrine pathways. Upregulation of NRP1 in tumor cells correlates with the activation of HGF/SF/c-Met pathways in both primary glioma specimens and xenograft gliomas, and inhibition of endogenous c-Met or NRP1 attenuates NRP1-enhanced HGF/SF/c-Met signaling. In addition, our data demonstrating NRP1 expression patterns in primary human glioma specimens and significant enhancement of tumor angiogenesis in glioma xenografts suggest that tumor cell-derived NRP1 stimulates vessel growth in a juxtacrine manner. These pathways appear to act in concert in promoting glioma growth and angiogenesis. Thus, our studies demonstrate a necessity for simultaneously targeting NRP1/VEGF and HGF/SF/c-Met signaling pathways in the treatment of human gliomas.

Materials and methods

Cell lines and their cultures

Human glioma cell lines U87MG, U118MG and T98G were obtained from the American Type Culture Collection (Manassas, VA, USA). Human glioma cell lines U251MG, U373MG, LNZ-308, LN229 and LN319 were from our collection. The transformed normal human astrocytes that form WHO grade III-like glioma in the murine brain (NHA/ETR) were from Dr R Pieper. Human umbilical endothelial cells (HUVEC) were from Cambrex (Rockland, ME, USA). The cells were cultured as described previously (Guo et al., 2001).

siRNA transient transfection

siRNAs were synthesized by Dharmacon Inc. (Lafayette, CO, USA). The sequences of siRNA for target genes were Met, 5′-GTGCAGTATCCTCTGACAG-3′; Sema 3A, 5′-AAAGTTCATTAGTGCCCACCT-3′ and NRP1 N1, 5′-GAGAGGTCCTGAATGTTCC-3′, N2, 5′-AAGCTCTGGGCATGGAATCAG-3′, and N3, 5′-AAAGCCCCGGGTACCTTACAT-3′; and Bad, Signal Silence Bad siRNA kit (Cell Signaling, Beverly, MA, USA). Cells were transfected with 120 nm of the indicated siRNA or a control siRNA (Invitrogen) using the Oligofectamine reagent (Invitrogen Inc., Carlsbad, CA, USA). After 24 h, siRNAs were removed and the cells were maintained in medium containing 10% FBS for an additional 48 h. The inhibition of protein expression was assessed by IB analysis.

Other methods

Reagents, antibodies, analyses of primary human glioma specimens, IHC, statistics, glioma xenograft models, immunoprecipitation (IP), IB, in vivo BrdUrd labeling, generation of U87MG NRP1-expressing cell lines and cell survival and proliferation assays are described in the Supplementary Information.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

The work was supported by grants NIH CA102011 and RSG CSM-107144 (S-Y C), the Hillman Fellows Program for Innovative Cancer Research to S-Y C and B H, and grant NIH CA095809 to TM (in part).

References

- Abounader R, Lal B, Luddy C, Koe G, Davidson B, Rosen EM, et al. In vivo targeting of SF/HGF and c-met expression via U1snRNA/ribozymes inhibits glioma growth and angiogenesis and promotes apoptosis. FASEB J. 2002;16:108–110. doi: 10.1096/fj.01-0421fje. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Abounader R, Laterra J. Scatter factor/hepatocyte growth factor in brain tumor growth and angiogenesis. Neuro-oncol. 2005;7:436–451. doi: 10.1215/S1152851705000050. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Akagi M, Kawaguchi M, Liu W, McCarty MF, Takeda A, Fan F, et al. Induction of neuropilin-1 and vascular endothelial growth factor by epidermal growth factor in human gastric cancer cells. Br J Cancer. 2003;88:796–802. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6600811. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bachelder RE, Lipscomb EA, Lin X, Wendt MA, Chadborn NH, Eickholt BJ, et al. Competing autocrine pathways involving alternative neuropilin-1 ligands regulate chemotaxis of carcinoma cells. Cancer Res. 2003;63:5230–5233. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bagri A, Tessier-Lavigne M. Neuropilins as Semaphorin receptors: in vivo functions in neuronal cell migration and axon guidance. Adv Exp Med Biol. 2002;515:13–31. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ding H, Wu X, Roncari L, Lau N, Shannon P, Nagy A, et al. Expression and regulation of neuropilin-1 in human astrocytomas. Int J Cancer. 2000;88:584–592. doi: 10.1002/1097-0215(20001115)88:4<584::aid-ijc11>3.0.co;2-t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gagnon ML, Bielenberg DR, Gechtman Z, Miao HQ, Takashima S, Soker S, et al. Identification of a natural soluble neuropilin-1 that binds vascular endothelial growth factor: in vivo expression and antitumor activity. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2000;97:2573–2578. doi: 10.1073/pnas.040337597. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gao CF, Vande Woude GF. HGF/SF-Met signaling in tumor progression. Cell Res. 2005;15:49–51. doi: 10.1038/sj.cr.7290264. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guo P, Xu L, Pan S, Brekken RA, Yang ST, Whitaker GB, et al. Vascular endothelial growth factor isoforms display distinct activities in promoting tumor angiogenesis at different anatomic sites. Cancer Res. 2001;61:8569–8577. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hu B, Guo P, Fang Q, Tao HQ, Wang D, Nagane M, et al. Angiopoietin-2 induces human glioma invasion through the activation of matrix metalloprotease-2. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2003;100:8904–8909. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1533394100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klagsbrun M, Takashima S, Mamluk R. The role of neuropilin in vascular and tumor biology. Adv Exp Med Biol. 2002;515:33–48. doi: 10.1007/978-1-4615-0119-0_3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laterra J, Rosen E, Nam M, Ranganathan S, Fielding K, Johnston P. Scatter factor/hepatocyte growth factor expression enhances human glioblastoma tumorigenicity and growth. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1997;235:743–747. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.1997.6853. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miao HQ, Lee P, Lin H, Soker S, Klagsbrun M. Neuropilin-1 expression by tumor cells promotes tumor angiogenesis and progression. FASEB J. 2000;14:2532–2539. doi: 10.1096/fj.00-0250com. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parikh AA, Fan F, Liu WB, Ahmad SA, Stoeltzing O, Reinmuth N, et al. Neuropilin-1 in human colon cancer: expression, regulation, and role in induction of angiogenesis. Am J Pathol. 2004;164:2139–2151. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9440(10)63772-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rieger J, Wick W, Weller M. Human malignant glioma cells express semaphorins and their receptors, neuropilins and plexins. Glia. 2003;42:379–389. doi: 10.1002/glia.10210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- West DC, Rees CG, Duchesne L, Patey SJ, Terry CJ, Turnbull JE, et al. Interactions of multiple heparin binding growth factors with neuropilin-1 and potentiation of the activity of fibroblast growth factor-2. J Biol Chem. 2005;280:13457–13464. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M410924200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wey JS, Gray MJ, Fan F, Belcheva A, McCarty MF, Stoeltzing O, et al. Overexpression of neuropilin-1 promotes constitutive MAPK signalling and chemoresistance in pancreatic cancer cells. Br J Cancer. 2005;93:233–241. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6602663. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.