Abstract

The development of T cell tolerance directed toward tumor-associated Ags can limit the repertoire of functional tumor-reactive T cells, thus impairing the ability of vaccines to elicit effective antitumor immunity. Adoptive immunotherapy strategies using ex vivo expanded tumor-reactive effector T cells can bypass this problem; however, the susceptibility of effector T cells to undergoing tolerization suggests that tolerance might also negatively impact adoptive immunotherapy. Nonetheless, adoptive immunotherapy strategies can be effective, particularly those utilizing the drug cyclophosphamide (CY) and/or exogenous IL-2. In the current study, we used a TCR-transgenic mouse adoptive transfer system to assess whether CY plus IL-2 treatment rescues effector CD4 cell function in the face of tolerizing Ag (i.e., cognate parenchymal self-Ag). CY plus IL-2 treatment not only enhances proliferation and accumulation of effector CD4 cells, but also preserves the ability of these cells to express the effector cytokine IFN-γ (and to a lesser extent TNF-α) in proportion to the level of parenchymal self-Ag expression. When administered individually, CY but not IL-2 can markedly impede tolerization, although their combination is the most effective. Although effector CD4 cells in CY plus IL-2-treated self-Ag-expressing mice eventually succumb to tolerization, this delay results in an increased level of in situ IFN-γ expression in cognate Ag-expressing parenchymal tissues as well as death via a mechanism that requires direct parenchymal Ag presentation. These results suggest that one potential mechanism by which CY and IL-2 augment adoptive immunotherapy strategies to treat cancer is by impeding the tolerization of tumor-reactive effector T cells.

One of the major impediments in the design of vaccines that prime T cells to neutralize tumors is the development of T cell tolerance toward the targeted tumor-Ags (reviewed in Ref. 1). Adoptive immunotherapy strategies in which tumor-reactive effector T cells are expanded ex vivo and subsequently injected into cancer patients (2) can circumvent the problem that tumor-reactive T cells can undergo tolerization before the administration of tumor vaccines (3–8). Nonetheless, it has recently been demonstrated that effector/memory T cells are equally susceptible to undergoing peripheral tolerization as are naive counterparts (9–11), thus raising the possibility that tolerization might also negatively impact antitumor adoptive immunotherapy. Despite this potential problem, recent clinical trials have demonstrated that adoptive immunotherapy can induce significant tumor regression (12, 13). Interestingly, these trials used the cytotoxic drug cyclophosphamide (Cytoxan or CY3) to condition patients before receiving tumor-reactive effector T cells and/or exogenous IL-2 administered thereafter. Similar regimens also enhance the efficacy of antitumor adoptive immunotherapy in mouse models (6, 14, 15).

The mechanism by which CY and IL-2 enhance antitumor adoptive immunotherapy has not been precisely established, but is of considerable interest since it should provide insights into the parameters that regulate tumor immunity. Some studies have suggested that CY can eliminate tumor-specific regulatory T cells (14, 16) or elicit the expression of T cell growth factors (17) or type I IFNs (18). Given CY’s cytotoxic activity, it might also enhance the engraftment of adoptively transferred tumor-reactive effector T cells (15) by creating space (19–21). None of these potential mechanisms are mutually exclusive and, in fact, they might be synergistic.

Given the potential for tumor Ags to be presented in a tolerogenic manner (3–5) and the susceptibility of effector/memory T cells to undergoing peripheral tolerization (9–11), we speculated that CY and IL-2 might augment adoptive immunotherapy by impeding the tolerization of adoptively transferred tumor-reactive effector T cells. To assess the effect of CY and IL-2 on peripheral tolerization of effector T cells, we used our previously established murine model in which naive clonotypic TCR-transgenic CD4 cells specific for influenza hemagglutinin (HA) are adoptively transferred into nontransgenic (NT) recipients and primed with a recombinant vaccinia virus expressing HA (vacc-HA) to differentiate into Th1 effectors and are then induced to undergo tolerization following retransfer into secondary recipients that express HA as a parenchymal self-Ag (9, 11). We chose to use a system in which effector CD4 cell tolerization is induced by Ag deriving from healthy tissues rather than from tumors for several reasons. First, adoptive immunotherapy strategies generally target differentiation Ags that are expressed not only on tumors but also on the normal tissues from which the tumors derive (12, 13), and therefore the bulk of potentially tolerogenic Ag likely derives from normal tissues. Furthermore, the pathways by which normal self-Ags and tumor Ags are presented to induce T cell tolerance appear to be similar (cf Ref. 22 to Ref. 23). Finally, in our system the model self-Ag HA is expressed at high levels in several organs, leading to rapid and efficient tolerization of adoptively transferred HA-specific effector CD4 cells (9, 11), and thus this system represents a stringent test for the potential of CY plus IL-2 to impede the tolerization of adoptively transferred effector T cells.

We found that CY plus IL-2 treatment not only increases the proliferation and accumulation of adoptively transferred HA-specific clonotypic effector CD4 cells encountering self-HA, but also delays their loss of function on a per cell basis. Furthermore, this delay in tolerization allows these effector CD4 cells to express the effector cytokine IFN-γ in HA-expressing organs and ultimately induce death. These data are consistent with the possibility that one mechanism by which CY and IL-2 augment antitumor adoptive immunotherapy is by delaying the tolerization of adoptively transferred tumor-reactive effector T cells.

Materials and Methods

Mice

Adoptive transfer recipients were on the B10.D2 (H-2d), Thy1.2+ background (except for bone marrow chimeras, see below). C3-HAlow- and C3-HAhigh-transgenic mice both express the influenza HA gene (A/PR/ 8/34 Mount Sinai strain) under the control of the rat C3(1) promoter, which directs HA expression to a variety of nonlymphoid organs. Although both transgenic founder lines express HA in the same subset of organs, HA protein expression in the C3-HAhigh mice appears to be at least 1000-fold higher than in the C3-HAlow mice (22, 24). The 6.5 TCR-transgenic mice express a clonotypic TCR that recognizes an I-Ed-restricted HA epitope (110SFERFEIFPKE120) (25) and were backcrossed to a B10.D2, Thy1.1+ congenic background.

Bone marrow chimeras

Bone marrow chimeras were generated as previously described (26). In short, C3-HAhigh hosts backcrossed to a B6 (H-2b, Thy1.2+) background were depleted of NK cells by i.p. injection of 15 μl of rabbit anti-asialo GM1 γ-globulin (Wako Chemicals, Richmond, VA) 1 day before receiving 1000 rad of ionizing radiation followed by 4 × 106 T cell-depleted bone marrow cells prepared from NT B10.D2, Thy1.2+ donors. Chimeras were allowed a minimum of 6 wk recovery before experimentation.

Adoptive transfers

Adoptive transfers of naive (26) and resting Th1 effector (9) CFSE-labeled Thy1.1+ 6.5 clonotypic CD4 cells into Thy1.2+ recipients were performed as previously described. As indicated, some recipients were infected i.p. with 106 PFU of a recombinant vaccinia virus expressing HA (vacc-HA) 1 day before adoptive transfer.

CY and IL-2 treatments

Some adoptive retransfer recipients were treated with CY (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO) given i.p. at 180 mg/kg 1 day before receiving clonotypic effector CD4 cells and/or received daily i.p. injections of 104 U of recombinant human IL-2 (National Cancer Institute Biological Resources Branch, Frederick, MD) beginning the day of adoptive retransfer.

Flow cytometry

FACS analysis was performed as previously described (9, 11, 26). In short, clonotypic CD4 cells were identified as Thy1.1+ (using PerCP-conjugated anti-Thy1.1; BD PharMingen, San Diego, CA) and CFSEdim. For intracellular cytokine staining following in vitro restimulation with HA peptide-pulsed APCs, 107 splenocytes were cultured for 6 h with 100 μg/ml HA peptide and 5 μg/ml brefeldin A (Sigma-Aldrich) before surface staining with PerCP-conjugated anti-Thy1.1, fixation, and permeabilization, and finally staining with PE- and APC-conjugated anti-cytokine mAbs (or isotype controls to determine background staining; BD PharMingen). For ex vivo cytokine staining of clonotypic CD4 cells recovered from the lung, adoptive retransfer recipients were perfused before dissection and lymphocyte extraction as previously described (9), except that all buffers contained 1 μg/ml brefeldin A to prevent cytokine secretion (27). All quantitative FACS data are expressed as the mean ± SEM. Total IFN-γ and TNF-α expression was calculated as a product of the percentage of cytokine-positive cells and the level of cytokine expression (mean fluorescence intensity) and expressed in arbitrary units as previously described (26). To allow direct comparison of data collected from separate experiments, all samples were analyzed on the same flow cytometer (FACSCalibur; BD Biosciences, San Jose, CA) using identical settings.

Results

CY and IL-2 impede effector CD4 cell tolerization

To assess the effect of CY and IL-2 on peripheral tolerization of effector T cells, we used our previously established model in which naive CFSE-labeled clonotypic TCR-transgenic CD4 cells specific for influenza HA are adoptively transferred into NT recipients and primed with a recombinant vaccinia virus that expresses HA (vacc-HA), and on day 6 when they have differentiated into resting Th1 effectors they are recovered from spleens, relabeled with CFSE, and retransferred into secondary recipients that express HA as a parenchymal self-Ag. Upon encountering self-HA, the clonotypic effector CD4 cells undergo a vigorous proliferative response of several days’ duration, after which they become impaired in their ability to both undergo further rounds of division and to express IL-2. Interestingly, although several days of self-HA exposure are required to impair IL-2 expression and proliferative capacities, the potential of the clonotypic effector CD4 cells to express the effector cytokines TNF-α and IFN-γ is impaired following only 24 h (9, 11). In the current study, we repeated this basic experimental paradigm but treated the adoptive retransfer recipients with CY (180 mg/kg) the day before adoptive retransfer, and rIL-2 (104 U) was given daily following retransfer. This treatment regimen was based on previous murine adoptive immunotherapy studies (6, 15, 28).

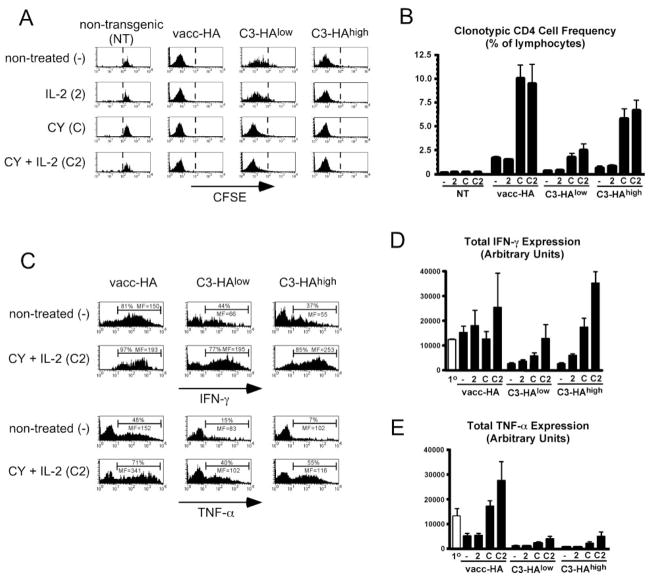

Consistent with our previous studies (9, 11), when the clonotypic effector CD4 cells were retransferred into nontreated transgenic secondary recipients that expressed either low (C3-HAlow) or high (C3-HAhigh) levels of parenchymal HA and were recovered from spleens 4 days later, they were found to have undergone significant proliferative responses as measured by CFSE dilution (Fig. 1A) and accumulation relative to control NT secondary recipients (Fig. 1B) (albeit proliferation was stronger in C3-HAhigh than in C3-HAlow recipients). Furthermore, the ability of retransferred clonotypic effector CD4 cells to express the effector cytokines IFN-γ and TNF-α following in vitro restimulation with HA peptide-pulsed APCs (as measured by intracellular staining, Fig. 1, C–E) were considerably reduced compared with their activity before retransfer. When C3-HAlow/high secondary recipients were treated with CY plus IL-2, the response of the adoptively retransferred clonotypic effector CD4 cells was dramatically altered; both CFSE dilution as well as accumulation increased in C3-HAlow recipients and accumulation also increased severalfold in C3-HAhigh recipients (although CFSE dilution was not altered, in all probability because CFSE had already been diluted to background levels in nontreated counterparts). Importantly, IFN-γ expression potential was restored to pre-retransfer levels in C3-HAlow recipients and even more remarkably was 3-fold higher in C3-HAhigh recipients (Fig. 1, C and D). CY plus IL-2 treatment also rescued TNF-α expression potential in both C3-HAlow and C3-HAhigh secondary recipients, albeit not as well as it rescued IFN-γ expression potential (Fig. 1, C and E). Interestingly, CY plus IL-2 treatment also augmented the accumulation (Fig. 1B) and effector cytokine expression potentials (Fig. 1, C–E) of clonotypic effector CD4 cells retransferred into vacc-HA-infected NT secondary recipients. Although CY plus IL-2 augmented clonotypic effector CD4 cell proliferative responses in HA-expressing secondary recipients, it did not induce proliferation in control NT recipients (Fig. 1, A and B). Thus, Ag is required for CY plus IL-2 to modify the response of adoptively retransferred clonotypic effector CD4 cells.

FIGURE 1.

CY and IL-2 treatment impedes self-Ag-induced effector CD4 cell tolerization. A total of 5 × 105 resting effector clonotypic CD4 cells was relabeled with CFSE and adoptively retransferred into the indicated secondary adoptive transfer recipients that were either nontreated (−), treated daily with 104 U of IL-2 (2), treated once the day before adoptive transfer with 180 mg/kg CY (C) or with CY plus IL-2 (C2). Four days after retransfer, the clonotypic CD4 cells were recovered from spleens for analysis. A, Representative histograms showing CFSE dilution (i.e., proliferative response), with a dotted line placed directly to the left of undivided cells. B, Frequencies of clonotypic CD4 cells. C, Representative histograms showing clonotypic CD4 cell intracellular IFN-γ and TNF-α expression following in vitro restimulation with HA peptide-pulsed APCs for untreated and CY plus IL-2-treated recipients. The percentage of clonotypic CD4 cells expressing cytokines as well as the level of cytokine expression (mean fluorescence (MF)) are shown. The cutoff for positive cytokine express was determined using an isotype control Ab (data not shown). D and E, Total IFN-γ and TNF-α expression, respectively, is shown for the indicated adoptive retransfer recipient groups in comparison to the primary effectors before retransfer (1o). B–D, n = 4 for C3-HAlow and high recipients groups, and n = 3 for NT and NT plus vacc-HA recipient groups.

In assessing the individual abilities of CY and IL-2 to modify the response of the retransferred clonotypic effector CD4 cells in HA-expressing secondary recipients, we found that CY by itself generally enhanced both proliferation and accumulation (Fig. 1, A and B) as well as effector cytokine expression potentials (Fig. 1, D and E) (albeit cytokine expression potential was less with CY alone than with CY plus IL-2). IL-2 by itself had a negligible effect on proliferation and accumulation (Fig. 1, A and B), but mediated partial rescue of IFN-γ expression potential in C3-HAhigh recipients (Fig. 1D). Thus, to varying extents both CY and IL-2 administered individually were able to impede effector CD4 cell tolerization in response to self-Ag, but their combination was the most effective.

CY and IL-2 impede naive CD4 cell tolerization

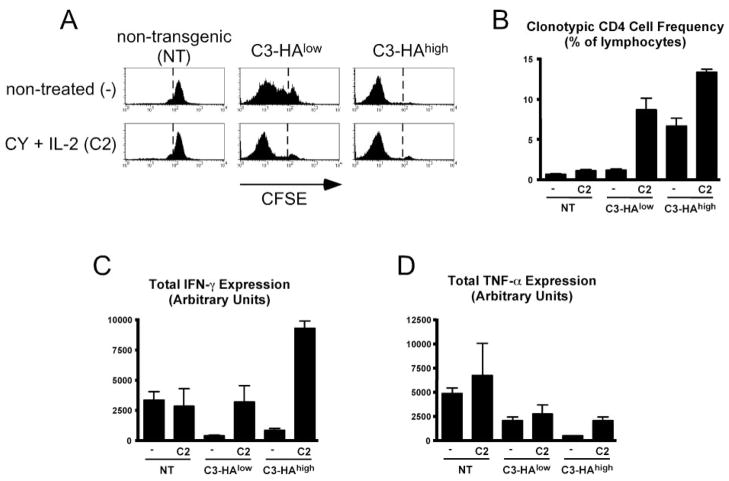

Given the ability of CY plus IL-2 to impede the tolerization of effector CD4 cells encountering self-Ag, we asked whether the same would also be true for naive CD4 cells. Thus, naive CFSE-labeled clonotypic CD4 cells were adoptively transferred into C3-HAlow, C3-HAhigh, and NT (control) secondary recipients that were either treated with CY plus IL-2 or not treated and subsequently recovered from spleens 4 days posttransfer for analysis. Overall, the response of naive clonotypic CD4 cells in CY plus IL-2-treated self-HA-expressing recipients was similar to that of clonotypic effector CD4 cells. More specifically, CY plus IL-2 enhanced both CFSE dilution (Fig. 2A) and accumulation (Fig. 2B) of naive clonotypic CD4 cells in C3-HAlow/high recipients, but had no effect in NT (i.e., non-HA-expressing) recipients. Additionally, CY plus IL-2 also allowed naive clonotypic effector CD4 cells to acquire the potential to express IFN-γ in C3-HAhigh recipients (Fig. 2C). Additionally, CY plus IL-2 partially prevented the loss of TNF-α expression potential that normally occurs in response to self-HA, although this effect was more pronounced in C3-HAhigh than in C3-HAlow recipients (Fig. 2D).

FIGURE 2.

CY and IL-2 treatment impedes self-Ag-induced naive CD4 cell tolerization. A total of 2.5 × 106 naive CFSE-labeled clonotypic CD4 cells was adoptively transferred into the indicated recipients that were either treated with CY plus IL-2 or not treated and recovered from spleens 4 days posttransfer. A, Representative CFSE dilution profiles. B, Frequency of clonotypic CD4 cells. C and D, Total intracellular IFN-γ and TNF-α expression, respectively, following in vitro restimulation. B and C, n = 3 for all groups.

CY and IL-2 cannot permanently block effector CD4 cell tolerization

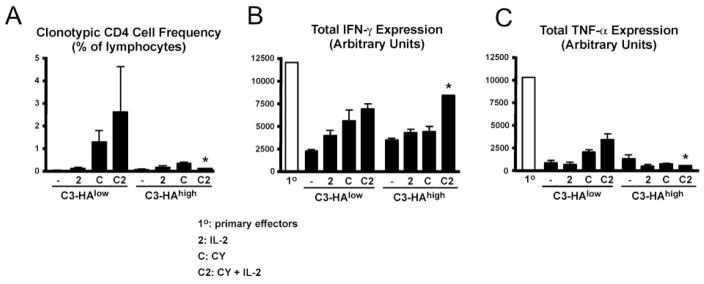

To assess whether the ability of CY plus IL-2 to impede effector CD4 cell tolerization was long-lived, we measured the function of clonotypic effector CD4 cells 8 days after retransfer into C3-HAlow/high secondary recipients. In CY plus IL-2-treated C3-HAhigh recipients, the frequency of clonotypic CD4 cells in the spleen at day 8 was 0.2% (Fig. 3A) compared with 7% on day 4 (Fig. 1B), whereas in CY plus IL-2-treated C3-HAlow recipients the frequency was ~3% at both time points. Functionally, it appeared that the clonotypic effector CD4 cells in CY plus IL-2-treated self-HA-expressing mice eventually succumbed to tolerization by day 8. For example, in C3-HAhigh recipients, IFN-γ expression potential that had increased 3-fold relative to the primary effectors at day 4 (Fig. 1D) became lower than the primary effectors by day 8 (Fig. 3B). Similarly, TNF-α expression potential was also lower on day 8 (Fig. 3C) than on day 4 (Fig. 1E). A similar trend was also observed in C3-HAlow recipients, although the relative differences in cytokine expression potentials between days 4 and 8 were less pronounced.

FIGURE 3.

CY and IL-2 blockade of effector CD4 cell tolerization is transient. A total of 5 × 105 resting effector clonotypic CD4 cells was retransferred into C3-HAlow/high secondary recipients and processed as in Fig. 1, but were analyzed 8 days after retransfer. A, Frequency of clonotypic CD4 cells. B and C, Total intracellular IFN-γ and TNF-α expression, respectively, following in vitro restimulation in the indicated adoptive retransfer recipient groups compared with primary effectors. n = 4 for each group, except for the CY plus IL-2-treated C3-HAhigh group in which n = 1 (*, refer to text).

The ability of CY and IL-2 to delay effector CD4 cell tolerization results in autoimmunity

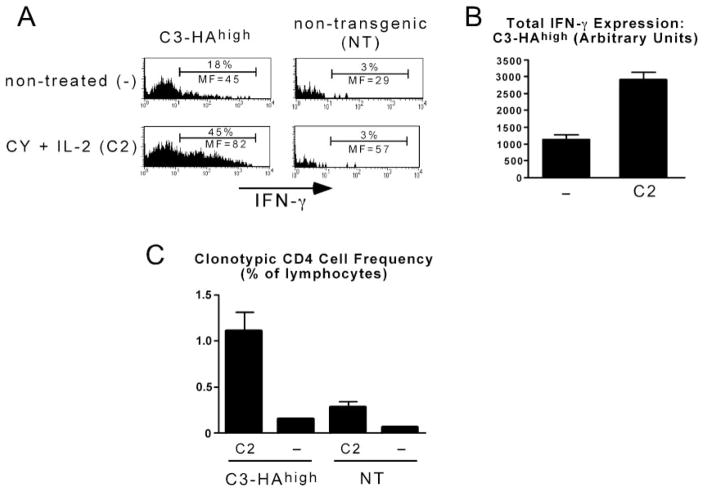

The preceding experiments indicated that CY plus IL-2 treatment delays rather than prevents self-Ag-induced effector CD4 cell tolerization. Nonetheless, we wanted to assess whether this delay had a physiological consequence. First, we asked whether CY plus IL-2 treatment could increase the level of in situ effector cytokine expression in HA-expressing nonlymphoid organs. Thus, ex vivo cytokine expression (i.e., in the absence of in vitro restimulation) was measured at a time point before tolerization (day 4) in the lungs of C3-HAhigh recipients (which express high levels of HA (24)). Overall, in situ IFN-γ expression on a per cell basis was ~3-fold higher in the lungs of CY plus IL-2-treated compared with nontreated C3-HAhigh recipients (Fig. 4, A and B; TNF-α expression was not altered, data not shown). CY plus IL-2 treatment also increased the frequency of clonotypic CD4 cells in the lungs of C3-HAhigh recipients by ~7-fold (Fig. 4C), which was similar to the increase observed in the spleen (Fig. 1B). The ability of CY plus IL-2 treatment to increase in situ clonotypic CD4 cell IFN-γ expression in the lung was Ag dependent, as fewer clonotypic effector CD4 cells were recovered from the lungs of CY plus IL-2-treated NT recipients (Fig. 4C), and these cells expressed negligible levels of IFN-γ (Fig. 4A). Thus, CY plus IL-2 treatment enhances the ability of effector CD4 cells to express effector function in nonlymphoid organs expressing cognate Ag.

FIGURE 4.

CY plus IL-2 treatment enhances self-Ag-induced effector CD4 cell IFN-γ expression in nonlymphoid tissues. A total of 1 × 106 clonotypic effector CD4 cells was retransferred into CY plus IL-2-treated or nontreated C3-HAhigh or NT recipients and recovered from lungs following perfusion 4 days later to assess accumulation and in situ IFN-γ expression. A, Representative histograms of IFN-γ expression. B, Total IFN-γ expression in treated (n = 4) and nontreated (n = 3) C3-HAhigh recipients. C, Frequency of clonotypic CD4 cells. n = 4 for treated C3-HAhigh recipients, n = 3 for nontreated C3-HAhigh recipients, n = 2 for treated NT recipients, and n = 3 for nontreated NT recipients. MF, Mean fluorescence.

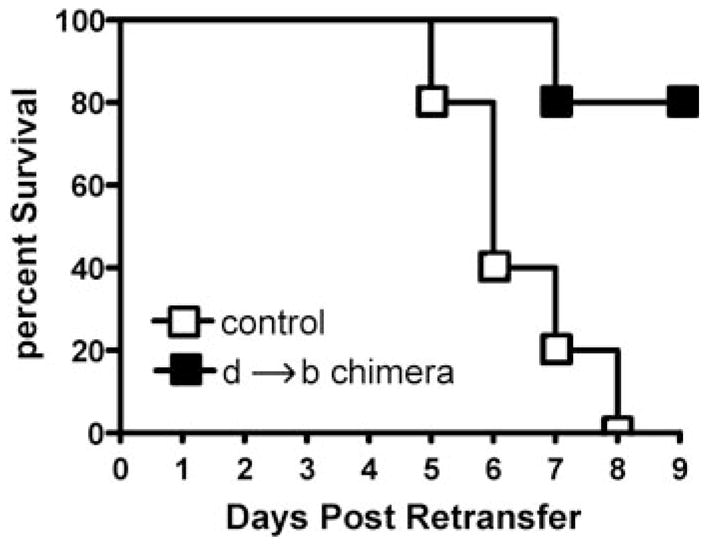

In assessing the effect of CY plus IL-2 treatment on the response of 5 × 105 adoptively retransferred clonotypic effector CD4 cells in C3-HAhigh recipients over the course of 8 days, we found that three of four mice died between days 5 and 8 (data not shown). In the one that did survive until day 8, the retransferred clonotypic effector CD4 cells became nonfunctional (Fig. 3). Taken together, these results raised the possibility that the delay in tolerization induced by CY plus IL-2 was of sufficient duration to mediate a significant level of pathology. Death might have been mediated by a systemic toxic shock-like mechanism in which clonotypic effector CD4 cells located in secondary lymphoid organs are stimulated, by APCs presenting parenchymally derived HA, to secrete large amounts of effectors cytokines such as TNF-α (29–31). An alternate possibility was that the delay in tolerization allowed clonotypic effector CD4 cells located in HA-expressing parenchymal organs to mediate autoimmune pathology in response to parenchymal cells presenting the class II-restricted HA epitope (as suggested from the preceding experiment). We thought that it was important to distinguish between these two possibilities, because in the context of adoptive immunotherapy scenarios to treat cancer, pathology specifically directed toward cognate Ag-expressing tissues (but not systemic shock) would be desirable. It seemed unlikely that systemic shock was the cause of death because shock generally induces death within 1–2 days, in contrast to our result in which death occurred between days 5 and 8. Nonetheless, to directly address this question, we retransferred 1.6 × 106 clonotypic effector CD4 cells into CY plus IL-2-treatd H-2d → H-2b C3-HAhigh bone marrow chimeras in which bone marrow-derived APCs can present parenchymally derived HA, but HA-expressing parenchymal cells are genetically incapable of directly presenting the class II-restricted HA epitope (26). In contrast to native C3-HAhigh control recipients in which 100% of the mice died between days 5 and 8, only one of five chimeric recipients died on day 7 (Fig. 5). This result indicates that the ability of adoptively retransferred clonotypic CD4 cells to induce death in CY plus IL-2-treated C3-HAhigh recipients is dependent on parenchymal presentation of the class II-restricted HA epitope. Furthermore, these data are consistent with organ-specific autoimmunity as the cause of death rather than a more systemic mechanism.

FIGURE 5.

The ability of adoptively retransferred clonotypic effector CD4 cells to induce death in CY plus IL-2-treated self-HA-expressing recipients requires parenchymal Ag presentation. Native C3-HAhigh and d → b C3-HAhigh bone marrow chimeras treated with CY plus IL-2 received adoptive retransfers of 1.6 × 106 resting effector clonotypic CD4 cells (n = 5 for each group). The percentage of surviving mice in each group over a 9-day period is shown in a Kapler-Meier plot.

CY can impede effector CD4 cell tolerization independently of its ability to induce lymphopenia

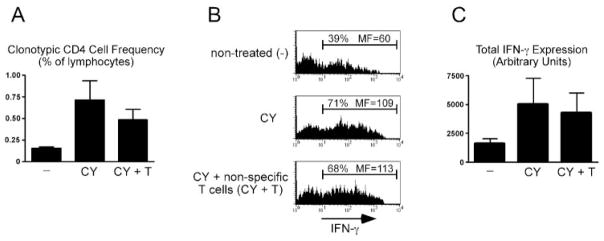

One potential mechanism to explain how CY impedes effector CD4 cell tolerization is through its cytotoxic activity that creates a lymphopenic environment (CY treatment induces a 5-fold decrease in total splenic T cell numbers; data not shown). Lymphopenia might in turn qualitatively alter the response of effector CD4 cells encountering cognate self-Ag. To test this possibility, clonotypic effector CD4 cells were retransferred into CY-treated C3-HAhigh recipients along with 2.5 × 107 Ag-nonspecific T cells (a quantity sufficient to prevent T cell homeostatic proliferation in lymphopenic hosts (32)). Thus, if lymphopenia was the critical factor that allows CY to impede effector CD4 cell tolerization, cotransfer of Ag-nonspecific T cells should mitigate this effect by filling up the space created by CY. Interestingly, cotransfer of Ag-nonspecific T cells did not markedly block the ability of CY to enhance either clonotypic effector CD4 cell accumulation (Fig. 6A) or IFN-γ expression potential (Fig. 6, B and C) at 4 days after retransfer into C3-HAhigh recipients.

FIGURE 6.

CY can impede effector CD4 cell tolerization independently of its ability to induce lymphopenia. A total of 5 × 105 resting effector clonotypic CD4 cells was relabeled with CFSE and adoptively retransferred into C3-HAhigh secondary adoptive transfer recipients that were either nontreated (−), treated once the day before adoptive retransfer with 180 mg/kg CY, or were treated with CY and also received pooled lymph node and spleen single-cell suspensions containing 2.5 × 107 T cells (CY + T). Four days after retransfer, the clonotypic CD4 cells were recovered from spleens for analysis. A, Frequency of clonotypic CD4 cells. B, Representative histograms showing clonotypic CD4 cell intracellular IFN-γ expression following in vitro restimulation with HA peptide-pulsed APCs, and C, total IFN-γ expression is presented as in Fig. 1. n = 4 for each recipient group. MF, Mean fluorescence.

Discussion

This study examined the effect of CY and IL-2 treatment on the response of effector CD4 cells encountering cognate tolerizing Ag, and thus modeled certain dynamics associated with adoptive immunotherapy strategies to treat cancer where tumor-reactive effector T cells are adoptively transferred into cancer patients in which cognate tumor-associated Ags are likely presented in a tolerogenic manner. It has previously been thought that CY’s cytotoxic properties might enhance the efficacy of adoptively transferred immunotherapy by augmenting the engraftment of adoptively transferred tumor-reactive effector T cells (15), possibly by creating space (19). Our results support this notion by documenting that CY enhances the proliferation and accumulation of effector CD4 cells encountering cognate self-Ag. Importantly, our data also indicate that CY can preserve the ability of these effector CD4 cells to express IFN-γ (and to a lesser extent TNF-α) on a per cell basis. This result is likely important physiologically, since both IFN-γ and TNF-α can play a role in mediating antitumor immunity (33–37). The inclusion of IL-2 enhanced the ability of CY to preserve effector CD4 cell function in the face of self-Ag. CY and IL-2 can also impede the tolerization of naive CD4 cells encountering self-Ag.

The ability of CY and IL-2 to impede the tolerization of effector CD4 cells encountering cognate self-Ag is not long-lived, however, as tolerance eventually develops within a period of 8 days. This might in part explain why it is generally necessary to give multiple transfers of tumor-reactive effector T cells to completely eliminate tumors (38). Nonetheless, two separate lines of evidence suggest that this delay in tolerization has a physiological impact. First, at a time point before tolerization CY plus IL-2 treatment leads to increased IFN-γ expression by effector CD4 cells in a nonlymphoid organ expressing cognate self-Ag. Additionally, CY plus IL-2-treated effector CD4 cell adoptive transfer recipients expressing high levels of cognate self-Ag are prone to death via a mechanism that requires direct parenchymal presentation of the relevant class II-restricted self-epitope. Presumably, in adoptive immunotherapy settings these effects would promote the destruction of tumor cells. Consistent with this possibility, human adoptive immunotherapy studies using CY and/or IL-2 have shown that adoptively transferred effector T cells specific for tumor-associated Ags can destroy both tumor and healthy cells that express the relevant Ags (13, 39). Although our current study focused on the response of effector CD4 cells, CY and IL-2 might also impede the tolerization of effector CD8 cells since memory CD8 cells are also susceptible to undergoing peripheral tolerization under normal conditions (10).

The immune system might have evolved the ability to tolerize effector T cells to limit the extent of autoimmune pathology that develops when self-reactive T cells that have not yet undergone peripheral tolerization are primed by pathogens that express cross-reactive Ags (i.e., molecular mimicry (40–45)). Whether molecular mimicry scenarios ultimately result in significant autoimmune pathology might depend upon the rate at which autoreactive effectors inflict damage relative to their rate of tolerization. Thus, autoimmune pathology might be more likely to develop when expression of the relevant self-Ags are confined to discrete anatomical locations (e.g., the pancreatic islets (46, 47)) where tolerogenic presentation is more limited (48, 49) in comparison to situations such as in our C3-HA-transgenic system in which the relevant self-Ags are widely expressed and presented tolerogenically. Consistent with this hypothesis, C3-HAhigh mice die when the rate of effector CD4 cell tolerization is delayed by CY plus IL-2 treatment.

One potential mechanism to explain how CY impedes effector CD4 cell tolerization is through its cytotoxic activity that might create a lymphopenic environment that qualitatively alters the response of effector CD4 cells encountering cognate self-Ag. This may not be the case, however, as cotransfer of 2.5 × 107 Ag-nonspecific T cells (a quantity sufficient to prevent T cell homeostatic proliferation in lymphopenic hosts (32)) did not prevent CY from impeding clonotypic effector CD4 cell tolerization in C3-HAhigh recipients. An alternate possibility is that CY impedes effector CD4 cell tolerization through its ability to induce type I IFNs (18), which can program immunogenic T cell responses (50). It may also be possible that both mechanisms play a redundant role in impeding tolerization. In addition to augmenting antitumor adoptive immunotherapy, CY can also enhance antitumor immunity elicited through vaccination (51–53). Although the mechanisms by which CY augments adoptive immunotherapy and vaccination may not be identical, it is plausible that both impede effector T cell tolerization. Exogenous IL-2 can augment antiviral T cell responses (54, 55) and appears to have an analogous effect in impeding effector CD4 cell tolerization in conjunction with CY. Regardless of the mechanisms employed by CY and IL-2 to impede effector CD4 cell tolerization, it is interesting that their effect is greater in mice expressing higher levels of self-Ag. This effect is in contrast to normal conditions in which greater levels of self-Ag lead to more rapid and profound T cell tolerization (56) and could be beneficial in the context of adoptive immunotherapy to treat cancer since patients presenting higher levels of the tolerizing/targeted tumor-associated Ags will likely experience the greatest level of T cell expansion and rescue of function.

Acknowledgments

We thank Charles Drake for helpful discussions.

Footnotes

This work was supported by National Institutes of Health Grant AI49813 and Research Scholar Grant RSG-02-235-01-LIB from the American Cancer Society (to A.J.A.) and U.S. Public Health Service Training Grant T32-AI07080 (to E.C.N.).

Abbreviations used in this paper: CY, cyclophosphamide or Cytoxan; HA, hemagglutinin; NT, nontransgenic; vacc-HA, recombinant vaccinia expressing HA.

References

- 1.Pardoll D. Does the immune system see tumors as foreign or self? Annu Rev Immunol. 2003;21:807. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.21.120601.141135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Yee C, Riddell SR, Greenberg PD. Prospects for adoptive T cell therapy. Curr Opin Immunol. 1997;9:702. doi: 10.1016/s0952-7915(97)80052-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bogen B. Peripheral T cell tolerance as a tumor escape mechanism: deletion of CD4+ T cells specific for a monoclonal immunoglobulin idiotype secreted by a plasmacytoma. Eur J Immunol. 1996;26:2671. doi: 10.1002/eji.1830261119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Stavely-O’Carroll K, Sotomayor E, Montgomery J, Borrello I, Hwang L, Fein S, Pardoll D, Levitsky H. Induction of antigen-specific T cell anergy: an early event in the course of tumor progression. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1998;95:1178. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.3.1178. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Shrikant P, Khoruts A, Mescher MF. CTLA-4 blockade reverses CD8+ T cell tolerance to tumor by a CD4+ T cell- and IL-2-dependent mechanism. Immunity. 1999;11:483. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(00)80123-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hu J, Kindsvogel W, Busby S, Bailey MC, Shi Y, Greenberg PD. An evaluation of the potential to use tumor-associated antigens as targets for antitumor T cell therapy using transgenic mice expressing a retroviral tumor antigen in normal lymphoid tissues. J Exp Med. 1993;177:1681. doi: 10.1084/jem.177.6.1681. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Morgan DJ, Kreuwel HT, Fleck S, Levitsky HI, Pardoll DM, Sherman LA. Activation of low avidity CTL specific for a self-epitope results in tumor rejection but not autoimmunity. J Immunol. 1998;160:643. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Reilly RT, Gottlieb MB, Ercolini AM, Machiels JP, Kane CE, Okoye FI, Muller WJ, Dixon KH, Jaffee EM. HER-2/neu is a tumor rejection target in tolerized HER-2/neu transgenic mice. Cancer Res. 2000;60:3569. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Higgins AD, Mihalyo MA, Adler AJ. Effector CD4 cells are tolerized upon exposure to parenchymal self-antigen. J Immunol. 2002;169:3622. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.169.7.3622. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kreuwel HT, Aung S, Silao C, Sherman LA. Memory CD8+ T cells undergo peripheral tolerance. Immunity. 2002;17:73. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(02)00337-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Long M, Higgins AD, Mihalyo MA, Adler AJ. Effector CD4 cell tolerization is mediated through functional inactivation and involves preferential impairment of TNF-α and IFN-γ expression potentials. Cell Immunol. 2003;224:114. doi: 10.1016/j.cellimm.2003.08.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Yee C, Thompson JA, Byrd D, Riddell SR, Roche P, Celis E, Greenberg PD. Adoptive T cell therapy using antigen-specific CD8+ T cell clones for the treatment of patients with metastatic melanoma: in vivo persistence, migration, and antitumor effect of transferred T cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2002;99:16168. doi: 10.1073/pnas.242600099. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Dudley ME, Wunderlich JR, Robbins PF, Yang JC, Hwu P, Schwartzentruber DJ, Topalian SL, Sherry R, Restifo NP, Hubicki AM, et al. Cancer regression and autoimmunity in patients after clonal repopulation with antitumor lymphocytes. Science. 2002;298:850. doi: 10.1126/science.1076514. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.North RJ. Cyclophosphamide-facilitated adoptive immunotherapy of an established tumor depends on elimination of tumor-induced suppressor T cells. J Exp Med. 1982;155:1063. doi: 10.1084/jem.155.4.1063. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Greenberg PD, Cheever MA. Treatment of disseminated leukemia with cyclophosphamide and immune cells: tumor immunity reflects long-term persistence of tumor-specific donor T cells. J Immunol. 1984;133:3401. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hoover SK, Barrett SK, Turk TM, Lee TC, Bear HD. Cyclophosphamide and abrogation of tumor-induced suppressor T cell activity. Cancer Immunol Immunother. 1990;31:121. doi: 10.1007/BF01742376. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Proietti E, Greco G, Garrone B, Baccarini S, Mauri C, Venditti M, Carlei D, Belardelli F. Importance of cyclophosphamide-induced bystander effect on T cells for a successful tumor eradication in response to adoptive immunotherapy in mice. J Clin Invest. 1998;101:429. doi: 10.1172/JCI1348. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Schiavoni G, Mattei F, Di Pucchio T, Santini SM, Bracci L, Belardelli F, Proietti E. Cyclophosphamide induces type I interferon and augments the number of CD44high T lymphocytes in mice: implications for strategies of chemoimmunotherapy of cancer. Blood. 2000;95:2024. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Maine GN, Mule JJ. Making room for T cells. J Clin Invest. 2002;110:157. doi: 10.1172/JCI16166. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Dummer W, Niethammer AG, Baccala R, Lawson BR, Wagner N, Reisfeld RA, Theofilopoulos AN. T cell homeostatic proliferation elicits effective antitumor autoimmunity. J Clin Invest. 2002;110:185. doi: 10.1172/JCI15175. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hu HM, Poehlein CH, Urba WJ, Fox BA. Development of antitumor immune responses in reconstituted lymphopenic hosts. Cancer Res. 2002;62:3914. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Adler AJ, Marsh DW, Yochum GS, Guzzo JL, Nigam A, Nelson WG, Pardoll DM. CD4+ T cell tolerance to parenchymal self-antigens requires presentation by bone marrow-derived antigen presenting cells. J Exp Med. 1998;187:1555. doi: 10.1084/jem.187.10.1555. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Sotomayor EM, Borrello I, Rattis FM, Cuenca AG, Abrams J, Staveley-O’Carroll K, Levitsky HI. Cross-presentation of tumor antigens by bone marrow-derived antigen-presenting cells is the dominant mechanism in the induction of T-cell tolerance during B-cell lymphoma progression. Blood. 2001;98:1070. doi: 10.1182/blood.v98.4.1070. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Adler AJ, Huang CT, Yochum GS, Marsh DW, Pardoll DM. In vivo CD4+ T cell tolerance induction versus priming is independent of the rate and number of cell divisions. J Immunol. 2000;164:649. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.164.2.649. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kirberg J, Baron A, Jakob S, Rolink A, Karjalainen K, von Boehmer H. Thymic selection of CD8+ single positive cells with a class II major histocompatibility complex-restricted receptor. J Exp Med. 1994;180:25. doi: 10.1084/jem.180.1.25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Higgins AD, Mihalyo MA, McGary PW, Adler AJ. CD4 cell priming and tolerization are differentially programmed by APCs upon initial engagement. J Immunol. 2002;168:5573. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.168.11.5573. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Reinhardt RL, Khoruts A, Merica R, Zell T, Jenkins MK. Visualizing the generation of memory CD4 T cells in the whole body. Nature. 2001;410:101. doi: 10.1038/35065111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ohlen C, Kalos M, Hong DJ, Shur AC, Greenberg PD. Expression of a tolerizing tumor antigen in peripheral tissue does not preclude recovery of high-affinity CD8+ T cells or CTL immunotherapy of tumors expressing the antigen. J Immunol. 2001;166:2863. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.166.4.2863. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Marrack P, Kappler J. The staphylococcal enterotoxins and their relatives. Science. 1990;248:705. doi: 10.1126/science.2185544. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Beutler B, Cerami A. Cachectin: more than a tumor necrosis factor. N Engl J Med. 1987;316:379. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198702123160705. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Alegre M, Vandenabeele P, Flamand V, Moser M, Leo O, Abramowicz D, Urbain J, Fiers W, Goldman M. Hypothermia and hypoglycemia induced by anti-CD3 monoclonal antibody in mice: role of tumor necrosis factor. Eur J Immunol. 1990;20:707. doi: 10.1002/eji.1830200337. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Dummer W, Ernst B, LeRoy E, Lee D, Surh C. Autologous regulation of naive T cell homeostasis within the T cell compartment. J Immunol. 2001;166:2460. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.166.4.2460. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Hung K, Hayashi R, Lafond-Walker A, Lowenstein C, Pardoll D, Levitsky H. The central role of CD4+ T cells in the antitumor immune response. J Exp Med. 1998;188:2357. doi: 10.1084/jem.188.12.2357. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Qin Z, Blankenstein T. CD4+ T cell–mediated tumor rejection involves inhibition of angiogenesis that is dependent on IFN γ receptor expression by nonhematopoietic cells. Immunity. 2000;12:677. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(00)80218-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Ikeda H, Old LJ, Schreiber RD. The roles of IFN γ in protection against tumor development and cancer immunoediting. Cytokine Growth Factor Rev. 2002;13:95. doi: 10.1016/s1359-6101(01)00038-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Poehlein CH, Hu HM, Yamada J, Assmann I, Alvord WG, Urba WJ, Fox BA. TNF plays an essential role in tumor regression after adoptive transfer of perforin/IFN-γ double knockout effector T cells. J Immunol. 2003;170:2004. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.170.4.2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Winter H, Hu HM, McClain K, Urba WJ, Fox BA. Immunotherapy of melanoma: a dichotomy in the requirement for IFN-γ in vaccine-induced antitumor immunity versus adoptive immunotherapy. J Immunol. 2001;166:7370. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.166.12.7370. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Matsui K, O’Mara LA, Allen PM. Successful elimination of large established tumors and avoidance of antigen-loss variants by aggressive adoptive T cell immunotherapy. Int Immunol. 2003;15:797. doi: 10.1093/intimm/dxg078. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Yee C, Thompson JA, Roche P, Byrd DR, Lee PP, Piepkorn M, Kenyon K, Davis MM, Riddell SR, Greenberg PD. Melanocyte destruction after antigen-specific immunotherapy of melanoma: direct evidence of T cell-mediated vitiligo. J Exp Med. 2000;192:1637. doi: 10.1084/jem.192.11.1637. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Wucherpfennig KW, Strominger JL. Molecular mimicry in T cell-mediated autoimmunity: viral peptides activate human T cell clones specific for myelin basic protein. Cell. 1995;80:695. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(95)90348-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Gross DM, Forsthuber T, Tary-Lehmann M, Etling C, Ito K, Nagy ZA, Field JA, Steere AC, Huber BT. Identification of LFA-1 as a candidate autoantigen in treatment-resistant Lyme arthritis. Science. 1998;281:703. doi: 10.1126/science.281.5377.703. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Bachmaier K, Neu N, de la Maza LM, Pal S, Hessel A, Penninger JM. Chlamydia infections and heart disease linked through antigenic mimicry. Science. 1999;283:1335. doi: 10.1126/science.283.5406.1335. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Ohteki T, Hessel A, Bachmann MF, Zakarian A, Sebzda E, Tsao MS, McKall-Faienza K, Odermatt B, Ohashi PS. Identification of a cross-reactive self ligand in virus-mediated autoimmunity. Eur J Immunol. 1999;29:2886. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1521-4141(199909)29:09<2886::AID-IMMU2886>3.0.CO;2-A. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Panoutsakopoulou V, Sanchirico ME, Huster KM, Jansson M, Granucci F, Shim DJ, Wucherpfennig KW, Cantor H. Analysis of the relationship between viral infection and autoimmune disease. Immunity. 2001;15:137. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(01)00172-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Lang HL, Jacobsen H, Ikemizu S, Andersson C, Harlos K, Madsen L, Hjorth P, Sondergaard L, Svejgaard A, Wucherpfennig K, et al. A functional and structural basis for TCR cross-reactivity in multiple sclerosis. Nat Immunol. 2002;3:940. doi: 10.1038/ni835. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Ohashi PS, Oehen S, Buerki K, Pircher H, Ohashi CT, Odermatt B, Malissen B, Zinkernagel RM, Hengartner H. Ablation of “tolerance” and induction of diabetes by virus infection in viral antigen transgenic mice. Cell. 1991;65:305. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(91)90164-t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Oldstone MB, Nerenberg M, Southern P, Price J, Lewicki H. Virus infection triggers insulin-dependent diabetes mellitus in a transgenic model: role of anti-self (virus) immune response. Cell. 1991;65:319. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(91)90165-u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Kurts C, Heath WR, Carbone FR, Allison J, Miller JF, Kosaka H. Constitutive class I-restricted exogenous presentation of self antigens in vivo. J Exp Med. 1996;184:923. doi: 10.1084/jem.184.3.923. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Morgan DJ, Kurts C, Kreuwel HT, Holst KL, Heath WR, Sherman LA. Ontogeny of T cell tolerance to peripherally expressed antigens. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1999;96:3854. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.7.3854. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Le Bon A, Etchart N, Rossmann C, Ashton M, Hou S, Gewert D, Borrow P, Tough DF. Cross-priming of CD8+ T cells stimulated by virus-induced type I interferon. Nat Immunol. 2003;4:1009. doi: 10.1038/ni978. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Berd D, Maguire HC, Jr, Mastrangelo MJ. Induction of cell-mediated immunity to autologous melanoma cells and regression of metastases after treatment with a melanoma cell vaccine preceded by cyclophosphamide. Cancer Res. 1986;46:2572. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Li L, Okino T, Sugie T, Yamasaki S, Ichinose Y, Kanaoka S, Kan N, Imamura M. Cyclophosphamide given after active specific immunization augments antitumor immunity by modulation of Th1 commitment of CD4+ T cells. J Surg Oncol. 1998;67:221. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1096-9098(199804)67:4<221::aid-jso3>3.0.co;2-a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Machiels JP, Reilly RT, Emens LA, Ercolini AM, Lei RY, Weintraub D, Okoye FI, Jaffee EM. Cyclophosphamide, doxoru-bicin, and paclitaxel enhance the antitumor immune response of granulocyte/ macrophage-colony stimulating factor-secreting whole-cell vaccines in HER-2/ neu tolerized mice. Cancer Res. 2001;61:3689. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Blattman JN, Grayson JM, Wherry EJ, Kaech SM, Smith KA, Ahmed R. Therapeutic use of IL-2 to enhance antiviral T-cell responses in vivo. Nat Med. 2003;9:540. doi: 10.1038/nm866. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.D’Souza WN, Lefrancois L. IL-2 is not required for the initiation of CD8 T cell cycling but sustains expansion. J Immunol. 2003;171:5727. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.171.11.5727. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Singh NJ, Schwartz RH. The strength of persistent antigenic stimulation modulates adaptive tolerance in peripheral CD4+ T cells. J Exp Med. 2003;198:1107. doi: 10.1084/jem.20030913. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]