Abstract

This study examined an ecological perspective on the development of antisocial behavior during adolescence, examining direct, additive, and interactive effects of child and both parenting and community factors in relation to youth problem behavior. To address this goal, early adolescent dispositional qualities were examined as predictors of boys' antisocial behavior within the context of parents' knowledge of adolescent activities and neighborhood dangerousness. Antisocial behavior was examined using a multi-method latent construct that included self-reported delinquency, symptoms of conduct disorder, and court petitions in a sample of 289 boys from lower socioeconomic status backgrounds who were followed longitudinally from early childhood through adolescence. Results demonstrated direct and additive findings for child prosociality, daring, and negative emotionality that were qualified by interactions between daring and neighborhood dangerousness, and between prosociality and parental knowledge. The findings have implications for preventive intervention approaches that address the interplay of dispositional and contextual factors to prevent delinquent behavior in adolescence.

Antisocial behavior (AB) in adolescence is predictive of numerous problems in adulthood including crime, mental health concerns, substance dependence, and work problems (Moffitt, Caspi, Harrington, & Milne, 2002). Due in part to the personal, economic, and social toll of AB, extensive attention has been directed toward elucidating factors that increase risk for engaging in AB during adolescence. For example, child attributes and contextual variables, including parenting and the broader family ecology, have received much support as factors in the emergence of conduct problems during middle childhood and the subsequent development of more serious AB in adolescence (Campbell, Shaw, & Gilliom, 2000; Dishion & Patterson, 2006; Lahey & Waldman, 2003). In line with a focus on child attributes and contextual mechanisms and the development of AB, the present study examined child dispositions, including sensation seeking, prosociality, and negative emotionality, and contextual factors, including parental knowledge of adolescent activities and neighborhood dangerousness, as predictors of AB from early to mid adolescence.

Furthermore, a transactional perspective suggests that deviations from normal behavior are not solely related to factors within the individual or context but rather interactions between child attributes and context (Sameroff, 2000; Sameroff & Mackenzie, 2003). Depending on the context, child attributes may serve as sources of either vulnerability or resilience in the development of psychopathology (Nigg, 2006). This interactive interplay is particularly salient for AB during the transition to adolescence because both time outside the home and the seriousness of AB increase during adolescence (Dodge, Coie, & Lynam, 2006). Child dispositions associated with AB, particularly those that may be linked to risky early child temperament and/or later adult personality traits, may be exacerbated when a young adolescent lives in a relatively dangerous neighborhood or when parents have little knowledge of their adolescent's activities and whereabouts (Lynam et al., 2000). Therefore, the central goal of the present study was to examine contextual risk factors as moderators of relations between youth dispositions and antisocial outcomes in adolescence.

Child Characteristics and Risk of Antisocial Behavior

A vast amount of research has linked child dispositional traits, including early temperamental attributes and later personality traits, with an array of outcomes including psychopathology. Temperament theories emphasize early-appearing, relatively stable differences in children's behavioral styles and regulation of emotion in response to affectively significant stimuli (Wachs & Bates, 2001; Rothbart, Posner, & Hershey, 1995; Lahey, Waldman, & McBurnett, 1999). Theories of personality similarly emphasize relatively stable global differences in behavior and response to the environment (McCrae & Costa, 1997). While temperament contributes to later personality development and many temperament traits map onto adult theories of personality (Shiner & Caspi, 2003; Wachs & Bates, 2001), most research on temperament has been confined to infancy and childhood. However, temperamental attributes also have been studied during adolescence and adulthood (John, Caspi, Robins, Moffitt, & Stouthamer-Loeber, 1994; Rothbart, Ahadi, & Evans, 2000). Dispositional characteristics during late childhood and adolescence should play a role in the development of psychopathology, but research has been lacking that links dispositions during this key transitional period to increased risk for later AB. Note that the term “disposition” will be used to refer to broad and general trait-like characteristics during late childhood and early adolescence that likely reflect earlier temperamental traits and/or later personality.

Beginning with examinations of difficult temperament as a predictor of early behavior problems (e.g., Bates, Maslin, & Frankel, 1985) and dimensions of personality as predictors of crime and delinquency (see Eysenck, 1996), extensive research has supported an association between a wide range of dispositional characteristics and externalizing problems. For example, fearlessness observed at age 2 predicted trajectories of elevated conduct problems across early and middle childhood in models controlling for other factors including parenting, maternal depression, child IQ, and family demographics (Shaw, Gilliom, Ingolsby, & Nagin, 2003). Given empirical support for the role of temperament and personality in the development and maintenance of AB, multiple theories addressing externalizing problems across the lifespan highlight temperament-related constructs as key risk factors. For example, Eisenberg and colleagues (e.g., Eisenberg, Hofer, & Vaughan, 2007) suggest that undercontrolled (externalizing) behavior is predicted by low levels of effortful control, high levels of impulsivity, and high levels of negative emotionality, as demonstrated by their longitudinal research (e.g., Eisenberg et al., 2001). Frick and Morris (2004; see also Nigg, 2006) suggest that developmental precursors to callous-unemotional traits including fearlessness and impaired conscience development may have unique associations with covert AB and psychopathy in late childhood and adolescence.

A recently proposed developmental propensity model of AB examines dispositions that fit with the theoretical perspectives described above (Lahey & Waldman, 2003). This propensity model is an attempt to integrate older propensity theories (Hirshi, 1969; Gottfredson & Hirshi, 1990; Farrington, 1995) with recent theory and empirical research on temperament, personality, and developmental theories of AB. Research on this model has yielded three factors: daring, negative emotionality, and prosociality (Lahey et al., 2008). Daring was central to Farrington and West's (1993) description of predictors of crime and encompasses high-energy activities and other risk-taking opportunities that are theoretically related to traits such as sensation seeking and novelty seeking. Furthermore, daring may be inversely related to Kagan's temperamental dimension of behavioral inhibition (see Kagan, Reznick, & Snidman, 1988). Negative emotionality is the second factor in Lahey and colleagues' model and is proposed to relate to the Big Five factor of neuroticism, as reflected in frequent and intense experience of negative emotions. Numerous forms of psychopathology are associated with high levels of negative emotionality (e.g., Clark & Watson, 1991). Furthermore, oppositional traits including irritability and defiance are indicative of high levels of negative emotionality and frequently precede more serious forms of AB (Lahey, Waldman, & McBurnett, 1999). Prosociality is the third dimension and includes empathy, dispositional sympathy, respect for rules, and guilt in response to misdeeds. Conceptually, prosociality shares some common ground with the Five-Factor Model's (McCrae & Costa, 1997) dimension of agreeableness. High levels of empathy, guilt in response to misdeeds, and other aspects of agreeableness should protect children against involvement in antisocial activities. Furthermore, prosociality is inversely related to callous/unemotional traits (Lahey & Waldman, 2003). Both callous/unemotional traits and low levels of prosociality show a similar pattern of modest yet reliable correlations with AB suggesting that prosociality and AB are similar but not synonymous constructs (Barry et al., 2000; Lahey et al., 2008).

All three factors are related to AB and associated problems in concurrent and prospective longitudinal studies (see Lahey & Waldman, 2003 for a review). For example, constructs associated with the daring dimension, such as sensation seeking, are correlated with conduct problems (e.g., Arnett, 1996; Daderman, 1999). Negative emotionality predicts AB and other forms of psychopathology in adults (e.g., Krueger, 1999), as well as externalizing problems in children and adolescents (e.g., Eisenberg, Fabes et al. 1996), although other studies have failed to find a robust association during adolescence (e.g., John et al., 1994). Negative emotionality has also been linked to internalizing problems (Eisenberg et al., 2001) and may be particularly salient in the development of comorbid pathologies. Lastly, a low level of prosociality is associated with AB across childhood and adolescence (e.g., Haemaelaeinen & Pulkkinen, 1996). Given past research linking both temperament and personality to AB and the role these dispositions should theoretically play in the development of AB during adolescence, a first goal of the present study was to examine these characteristics in early adolescence as direct and additive predictors of later AB in an ethnically diverse, at-risk sample.

Moderators of the Disposition-Antisocial Behavior Link

Although there are robust links between dispositional traits at various ages and later adjustment, the field has begun to examine the more complex moderated link between dispositions (particularly early temperament) and psychopathology (Nigg, 2006). As a result, a second goal of the present study was to test contextual factors as moderators of relations between daring, negative emotionality, and prosociality, and AB from early to middle adolescence. One key implication of a transactional approach is that risky dispositions should lead to higher levels of AB in riskier contexts (Sameroff, 2000). In examining a transactional perspective on the prediction of AB in adolescence, parental knowledge of adolescent activities and neighborhood risk are two key contextual factors that may interact with adolescent dispositional traits in predicting AB.

Parenting has held a central place in multiple developmental models of antisocial behavior (Aguilar, Sroufe, Egeland, & Carlson, 2000; Greenberg & Speltz, 1988; Patterson, Reid, & Dishion, 1992; Shaw & Bell, 1993), and parental behavior has been consistently related to early conduct problems and later AB (Owens & Shaw, 2003; Shaw et al., 2003). In early adolescence, parental knowledge of the adolescent's activities and whereabouts becomes increasingly important (Dishion & McMahon, 1998). Previously, the term “parental monitoring” was equated with parental knowledge of adolescent activities. Active parental monitoring attempts are not necessarily helpful, and adolescent disclosure of activities is a more robust correlate of adolescent behavior (Stattin & Kerr, 2000). Furthermore, adolescents may have a more accurate representation of their parent's knowledge because parents may overestimate their actual level of knowledge (Laird, Pettit, Bates, & Dodge, 2003; Smetana, 2008). As a result, the present study examined the adolescent's reports of his parent's knowledge of activities rather than active monitoring attempts.

Because parental knowledge is a robust contextual factor associated with adolescent involvement in delinquent activities (e.g., Laird et al., 2003), it is a likely candidate to moderate effects of risky dispositions on AB. Adolescents with predispositions to daring behaviors whose parents have little knowledge of their activities may have greater opportunities to engage in AB. When parents are not as aware of their adolescent's whereabouts and do not channel their adolescent's interests into prosocial expressions of their propensity toward sensation seeking, daring adolescents may spend time with deviant peers and involve themselves in high-excitement antisocial behaviors. In the scenario of low parental knowledge and low levels of prosociality, an adolescent's unempathic and callous traits would be more likely to be channeled into delinquent activities if parents are not consistently aware of their adolescent's choices regarding peer relationships and use of free time. Alternately, when parents and adolescents openly discuss information on the adolescent's whereabouts, parental involvement in their adolescent's daily life may reduce the negative consequences of low levels of prosociality. For example, parents' awareness of their young adolescent's activities might lead to discussion of the impact of AB on others following initial minor transgressions and increased attention to the adolescent's choices, thus preventing the development of future, more serious AB. Although somewhat speculative, it is also possible that more frequent parent-child communication of activities may reduce the likelihood of involvement in high-risk situations when adolescents have a tendency toward irritability and other intense negative emotions that could lead to serious conflict or violence.

Neighborhood dangerousness is a second contextual factor that has the potential to moderate the relation between dispositional traits and AB. Neighborhood environments characterized by crime and exposure to deviant peers may be powerful negative learning environments during childhood, and neighborhood risk often predicts increased AB in adolescence (Leventhal & Brooks-Gunn, 2000). For example, exposure to community violence was associated with later AB among school-age children and adolescents (McCabe, et. al., 2005; Ng-Mak, Salzinger, Feldman, & Stueve, 2004). Moreover, the association between exposure to community violence and antisocial outcomes remains after accounting for the effects of other confounding variables such as child maltreatment, socioeconomic status, and intimate partner violence (McCabe et al., 2005).

Adolescents with risky dispositions who live in dangerous neighborhoods may be especially likely to engage in AB across adolescence. For example, in two separate reports, trait impulsivity was more strongly related to delinquency in poorer or lower quality neighborhoods (Lynam et al., 2000; Meier, Slutske, Arndt, & Cadoret, 2008). Similar findings exist for the relations among neighborhood quality, temperamental traits and AB in early childhood such that low neighborhood quality was associated with increased AB in the context of temperamental risk (Colder, Lengua, Fite, Mott, & Bush, 2006). We hypothesized a similar interaction in the present study, using parental report of familial exposure to neighborhood violence as the moderator. For example, daring adolescents in high-risk neighborhoods may find an outlet for their high-excitement interests by becoming involved in gangs or other criminal activities, whereas daring adolescents in low-risk neighborhoods may have more opportunities to channel their energy into prosocial activities. Furthermore, adolescents low in prosociality may be more likely to engage in conflicts with peers or neighbors in areas where crime is more rampant, and their lack of guilt over misdeeds may lead to more serious AB in high-risk environments that reinforce delinquent behavior. Conversely, in low-risk neighborhoods the peer group culture may disapprove of callous delinquent behaviors, thus ameliorating the likelihood of peer deviancy training that might exist for adolescents in high-risk neighborhoods. Although speculative, deviant peers in a high-risk neighborhood may more likely encourage an adolescent's propensity toward negative emotions to be channeled into delinquent behaviors such as fighting and bullying. In contrast, low-risk neighborhoods offer comparatively fewer opportunities for involvement in delinquent activities as an outlet for expression of negative emotion.

The Current Study

A central goal of the present study was to examine risky dispositions measured in early adolescence as predictors of AB later in adolescence. A latent adolescent AB construct was created from court records, symptom counts of conduct disorder from a psychiatric interview, and youth reports of delinquency. Risky dispositions of negative emotionality, prosociality, and daring were expected to have direct and independent relationships with AB, and we also considered the relations between dispositions and AB while accounting for the youth's previous history of AB across middle childhood. The present study also examined interactions between child and contextual factors, exploring whether parental knowledge of the adolescent's activities and neighborhood dangerousness moderated associations between dispositional constructs and AB. High levels of daring traits and low levels of prosociality were expected to relate more strongly to AB in the context of low parental knowledge and high levels of neighborhood dangerousness. At a more exploratory level, we also examined parental knowledge and neighborhood dangerousness as moderators of relations between negative emotionality and AB. The present study was conducted using data from a study of boys from low socioeconomic status (SES) backgrounds who were followed longitudinally across childhood and adolescence. The sample increased our ability to detect significant moderators because families from low SES backgrounds residing across a large metropolitan area were likely to exhibit a broad range of parental involvement and experience wide variation in neighborhood risk. Because the sample was ethnically diverse and there was likely to be increasing variability in SES by adolescence, we also examined child race and SES variables as potential covariates.

Method

Participants

Participants in this study are part of the Pitt Mother and Child Project (PMCP), an ongoing longitudinal study of child vulnerability and resiliency in low-income families (Shaw et al., 2003). In 1991 and 1992, 310 infant boys and their mothers were recruited from Women, Infants, and Children (WIC) Nutrition Supplement Clinics in Allegheny County, PA when the boys were between 6 and 17 months old. At the time of recruitment, 53% of the target children in the sample were European-American, 36% were African-American, 5% were biracial, and 6% were of other races (e.g., Hispanic-American or Asian-American). Two-thirds of mothers in the sample had 12 years of education or less. The mean per capita income was $241 per month ($2,892 per year), and the mean Hollingshead SES score at the beginning of the study was 24.5, indicative of sample that ranged from impoverished to working class. Thus, many boys in this study were considered at elevated risk for antisocial outcomes because of their socioeconomic standing.

Retention rates have generally been high at each time point from age 1.5 through adolescence, with 90-94% of the initial 310 participants completing assessments at ages 5 and 6, some data available on 89% or 275 participants at ages 10, 11, or 12, and some data available on 89% or 276 participants at ages 15. The present study included the 289 boys with at least one measure available from the adolescent assessments at ages 11, 12, and 15 or court records that were the focus of this study.

Procedure

Target children and their mothers were seen for two- to three-hour visits at ages 1.5, 2, 3.5, 5, 5.5, 6, 8, 10, 11, 12, and 15 years old. Data were collected in the laboratory (ages 1.5, 2, 3.5, 6, 11) and/or at home (ages 2, 5, 5.5, 8, 10, 12, 15). Home and lab assessments included various structured observational tasks that are not the focus of the present report. In addition, parents and, beginning with the assessment at age 8 years, target children completed questionnaires regarding family issues (e.g., parenting, family member's relationship quality, neighborhood conditions), and child behavior. At all points, children were assessed with their “primary caregiver,” who in most cases were their mothers (at age 15, 90% of visits were with mothers), but could also be another adult who was responsible for the majority of the parenting (4% fathers, 2% step-mothers, and 2% were grandmothers at age 15). Beginning at the age 5 assessment, “alternate caregivers” were invited to participate. Most alternate caregivers identified themselves as the child's biological father (81.2% at age 5; 75.0% at age 10), but some alternate caregivers were stepfathers, the mother's boyfriend, grandparents, or other relatives (aunts, uncles). Participants were reimbursed for their time at the end of each assessment.

For the present study, assessment waves that invited the participation of a primary caregiver, alternate caregiver, and teacher during middle childhood (i.e., age 5, 6, 8, and 10 year-old assessments) provided information for the middle childhood externalizing problems covariate. The dispositional factors were measured at the age 12 assessment, and measures of the contextual factors were assessed either concurrently with the dispositional factors (parental knowledge) or at the prior assessment (neighborhood dangerousness). Lastly, the age 15 assessment provided information for two of the three elements of the AB factor (conduct disorder symptoms and self-reports of delinquency), and the third element, court records, were periodically collected throughout adolescence as documented below.

Measures

Middle childhood externalizing problems

Primary caregiver reports and, where applicable, alternate caregiver reports of boys' externalizing problems were obtained from the Child Behavior Checklist (CBCL; Achenbach, 1991). In addition, boys' teachers were invited to complete the Teacher Report Form (TRF), the version of the CBCL designed for teachers. Both the CBCL and TRF contain a broad-band externalizing problems factor. Items for the Externalizing factor on the CBCL include, “argues a lot,” “gets in many fights,” and “lying or cheating.” Similar item content exists on the TRF version, and each item is the rated on a 3-point scale ranging from 0 (not true) to 2 (very true or often true). In the current study, CBCL and TRF Externalizing factors demonstrated good internal reliability across middle childhood (αs ranged from .88 to .91 for primary caregiver reports; from .87 to .94 for alternate caregiver reports; and from .95 to .97 for teacher reports). For each informant, the Externalizing factor was standardized within assessment wave, and a mean standardized score across waves was obtained for each informant. Mean standardized scores were moderately correlated across informants, with bivariate correlations ranging from r=.35 (p < .01) for the correlation between alternate caregiver reports and teacher reports to r=.56 (p < .01) for the correlation between primary caregiver reports and alternate caregiver reports. Therefore, Externalizing scores across time for each informant were aggregated across informants so that each boy had a single score representing his level of externalizing problems across middle childhood. This approach allowed us to utilize information from multiple informants while maximizing the amount of data, particularly because missing data were somewhat more prevalent across time for teachers and alternate caregivers. More specifically, 96% of the original sample had at least one data point to create the mean standardized score for primary caregiver reports, 87% had at least one data point for teacher reports, and 81% had at least one data point for alternate caregiver reports.

Other covariates

We also examined the child's ethnicity and family-level and neighborhood-level SES factors as covariates. Child's ethnicity was coded as 0 for non-minority (50% of the sample) and 1 for ethnic minority (50% of the sample). SES factors included the family's yearly income and neighborhood-level SES disadvantage using data from the U.S. Census at the block group level (see Vanderbilt-Adriance & Shaw, 2008 for more information). Each SES variable was a composite based on the the age 11 and age 12 assessments to correspond to the assessments at which the contextual and dispositional information was collected.

Neighborhood dangerousness (age 11)

Neighborhood dangerousness was assessed via primary caregiver report when the child was age 11. Primary caregivers completed the Me and My Neighborhood (MMN) questionnaire which consists of 25 items assessing three neighborhood factors: cohesion, exposure to violence, and disorganization. The latter two factors were originally adapted from the City Stress Inventory (Ewart & Suchday, 2002) and factored similarly in the present sample. The exposure to violence factor was used as the measure of neighborhood dangerousness. This factor contains seven items that assess the perceived frequency of various dangerous events (i.e., ‘a friend was stabbed or shot’) on a four-point scale (0 = never, 1 = once, 2 = a few times, 3 = often). The exposure to violence factor had acceptable internal consistency (Cronbach's α = .79) in the present sample. Due to a large amount of skew for this scale (i.e., the majority of families reported none or very little exposure to violence), we used a natural log transformation of the exposure to violence factor for analyses.

Parental knowledge (age 12)

Using an interview developed at the Oregon Social Learning Center (Dishion, Patterson, Stoolmiller, & Skinner, 1991), interviewers asked children a series of questions about their parent's knowledge of their whereabouts and discipline practices at age 12. The knowledge factor was based on 5 items and focused on the degree to which parents were informed of boys' whereabouts, plans, and interests (Moilanen, Shaw, Criss, & Dishion, in press). Items included “How often does at least one of your parents know where you are after school?” and “How often does at least one of your parents have a pretty good idea about your plans for the coming day?” Boys responded to these items on a five-point response scale, ranging from 1 (Never or almost never) to 5 (Always or almost always). The scale demonstrated adequate internal consistency for a five-item scale (α = .60).

Adolescent dispositions (age 12)

To assess child prosociality, negative emotionality, and daring, the Child and Adolescent Disposition Scale (CADS; Lahey et al., 2008) was administered to primary caregivers and youth at the age-12 assessment. Eighty-two percent of the primary caregivers for the present sample of 289 boys provided ratings on the parental report version of the CADS, and the same percentage of boys provided self-reports on the CADS. Participants were asked to rate each of 31 items by thinking about how well the item described an emotion or behavior of the youth and how often it occurred during the last 12 months based on a four-point Likert scale, ranging from 1 (not at all) to 4 (very much/very often). In a previous study (Lahey et al., 2008), three factors were identified using both exploratory and confirmatory factor analysis in multiple samples: prosociality, negative emotionality, and daring. Moreover, these factors were shown to be internally consistent and externally valid in multiple samples, to have high test-retest reliability, and to be related to antisocial behavior both additively and interactively. Within the present sample, the same three factors were found, with similar items loading onto each factor. The prosociality factor contained 10 items for primary caregiver report and nine items for child report such as “do you (does he) feel bad for other children your (his) age when they get hurt?” The negative emotionality factor contained 10 items for primary caregiver report and seven items for child report such as “do you (does he) get upset easily?” The daring factor contained five items for both respondents such as “are you (is he) daring and adventurous?” Each factor had adequate internal consistency (Cronbach's αs ranged from .74 to .85 for primary caregiver reports and from .62 to .82 for child reports). Primary caregiver and child reports were standardized and aggregated for each factor so that each boy had a single score on each dispositional factor for use in analyses. Moderate correlations between primary caregiver and child reports for daring (r = .34, p < .01) and for prosociality (r = .29, p < .01) supported our decision to aggregate across informants. The correlation between primary caregiver and child reports for negative emotionality was also statistically significant (r = .18, p < .01), but the smaller magnitude of the correlation led to a more cautious approach for this construct (see below).

Youth-reported antisocial behavior (ages 15)

AB was assessed based on boys' reports at age 15 using an adapted version of the Self-report of Delinquency Questionnaire (SRD; Elliot, Huizinga, & Ageton, 1985). The SRD assesses the frequency with which an individual has engaged in aggressive and delinquent behavior, alcohol and drug use, and related offenses during the prior year. Using a 3-point rating scale (0 = never, 1 = once/twice, 2 = more often), adolescents rated the extent to which they engaged in different types of antisocial activities. Item content focused on behaviors such as skipping school without an excuse, taking something from a store without paying for it, hitting and physical fighting with classmates, siblings, or parents, drinking alcohol or using illegal drugs, and running away from home. Internal consistency for the measure was high at age 15 (α = .91).

Conduct disorder symptoms (age 15)

During the age 15 home visit, primary caregivers and their sons were administered the Schedule for Affective Disorders and Schizophrenia for School Aged Children (K-SADS; Kaufman et al., 1997) by a trained examiner. The K-SADS is a semi-structured interview that assesses DSM-IV child psychiatric symptoms over the last year. The same examiner privately interviewed the primary caregiver and then the adolescent about both internalizing (i.e., depression) and externalizing diagnoses (i.e., conduct disorder) and made a clinical judgment about the presence or absence of each symptom. To establish reliability, clinical interviewers participated in an intensive training program at the Western Psychiatric Institute and Clinic or were trained by doctoral-level clinical psychology students who had attended this training. All examiners were observed multiple times by experienced examiners before administering the interview. Additionally, every case in which a child approached or met diagnostic criteria was discussed at regularly held interviewing team meetings, which included all other interviewers and the third author, who is a licensed clinical psychologist with 18 years of experience using the K-SADS. For the current study, symptoms of conduct disorder (CD) were summed to create a continuous measure of CD symptomatology. There are 15 possible symptoms of CD, and they range from aggression against others to theft, destruction of property and other serious violations of laws and norms (American Psychiatric Association, 2000).

Court records (ages 15 to 18)

To assess each boy's involvement with the legal system, after receiving written permission from primary caregivers, court records were obtained from the primary county where the participants resided (Allegheny, PA) and when available, other counties where participants lived. The court records were obtained on an annual basis and were most recently collected when all boys were at least 15 years old. Given the two year range of the boys' birthdays, court records were last collected when the boys were between 15.9 and 18.0 years old (mean = 16.8 years). The number of petitions (equivalent to number of charges against the boy in this state) against each boy was summed to create a continuous measure of contact with the legal system. Given the lag in time between petition date and disposition hearing (similar to a verdict and sentencing), dispositions could not be used because many cases are still being processed. If court records could not be obtained for a boy, these data were considered missing (87% of the boys had data). Of those boys with data, 24% had at least one petition against them.

Analytic Plan

Following inspection of descriptive statistics and bivariate correlations, primary study hypotheses were examined with structural equation models (SEMs) in Mplus 5.1 using maximum likelihood estimation with robust estimators (MLR; Muthén & Muthén, 2007). The use of Mplus provided several advantages for the present data analyses. First, we were able to estimate adolescent antisocial behavior as a latent construct and examine predictors of the latent construct. The indicators of this construct were the total score on the SRD, the number of conduct disorder symptoms endorsed on the K-SADS, and the total number of court petitions. Each of these indicators of adolescent antisocial behavior demonstrated notable positive skew; therefore, the indicators were transformed with the natural log function prior to estimation in Mplus. Second, Mplus's MLR estimator provides parameter estimates adjusting for non-normality of observations (Muthén & Muthén, 2007). Because the transformed variables remained slightly skewed after the natural log transformations, MLR was the preferred approach for the data. Finally, Mplus has the capability to adjust for missing data using full information maximum likelihood (FIML) estimation. The amount of missing data was small for each individual measure, but listwise deletion would have limited the power to detect significant interactions between adolescent dispositions and contextual factors in this moderately-sized sample. Using FIML estimation, the analyses included the 289 participants with data available for at least one of the measures of adolescent dispositions, contextual factors, or antisocial behavior.

The use of Mplus permitted evaluation of multiple indices to evaluate model fit including chi-square, ratio of chi-square to degrees of freedom, the Root Mean Square Error of Approximation (RMSEA), and the Comparative Fit Index (CFI) in addition to the statistical significance of individual paths. Although we elected to examine our outcome as a latent construct, all predictors of the antisocial latent factor were manifest indicators including the Externalizing factor covariate, the early adolescent dispositions, and the contextual factors. These manifest indicators and relevant interaction terms were entered into the equations simultaneously to examine their unique and additive role as predictors of the antisocial latent factor. This approach allowed us to examine, interpret, and plot significant interaction terms in a meaningful manner that followed the procedures recommended for moderated effects (see Aiken & West, 1991; Holmbeck, 2002).

Results

Descriptive Statistics and Correlations

Table 1 presents descriptive statistics including the number of participants with data available for each measure and means, standard deviations, and ranges for covariates, predictors, and indicators of the antisocial latent construct. The untransformed versions of positively skewed variables (neighborhood dangerousness, youth-reported AB, conduct disorder symptoms, and court petitions) are presented for ease of interpretation. Table 2 presents intercorrelations between variables, including transformed versions of the skewed measures as used in subsequent analyses. Of note, the dispositional qualities appeared to be quite distinct as the correlation between daring and prosociality was non-significant, and the correlations between negative emotionality and the other two factors were relatively small in magnitude (rs = .20 to -.29). Correlations indicated that the majority of predictors from middle childhood or early adolescence were significantly correlated with the indicators of AB in the expected direction. However, the correlation between parental knowledge and youth-reported antisocial behavior was not significant. In addition, ethnicity and the SES variables were not related to youth-reported antisocial or conduct disorder symptoms, but they were correlated with the number of court petitions. As expected, the indicators of adolescent AB demonstrated moderate positive correlations with each other.

Table 1. Means and Standard Deviations.

| Variable | N | Range | M | SD |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Middle Childhood Externalizing Aggregate | 285 | -1.65 to 3.75 | .01 | .82 |

| Family Income Composite (thousands) | 258 | 0.00 to 96.00 | 30.34 | 17.26 |

| Neighborhood Census Composite | 281 | -1.53 to 3.29 | .13 | .88 |

| Daring | 236 | -2.37 to 2.00 | -.01 | .83 |

| Prosociality | 236 | -2.58 to 1.75 | .01 | .81 |

| Negative Emotionality | 236 | -1.53 to 2.43 | -.00 | .77 |

| Parental Knowledge | 232 | 1.40 to 5.00 | 4.13 | .74 |

| Neighborhood Dangerousness | 238 | 0.00 to 16.00 | 1.26 | 2.28 |

| Youth-Reported Antisocial Behavior | 257 | 0.00 to 49.00 | 8.92 | 9.59 |

| Conduct Disorder Symptoms | 247 | 0.00 to 11.00 | 1.07 | 1.97 |

| Court Petitions | 252 | 0.00 to 6.00 | .51 | 1.08 |

Table 2. Bivariate Correlations.

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Ethnicity | |||||||||||

| 2. Family Income | -.33** | ||||||||||

| 3. Neighborhood Census | .53** | -.35** | |||||||||

| 4. Externalizing- Middle Childhood | .15* | -.26** | .21** | ||||||||

| 5. Daring | -.02 | .04 | -.04 | .20** | |||||||

| 6. Prosociality | -.02 | .18** | -.24** | -.29** | .02 | ||||||

| 7. Negative Emotionality | .08 | -.19** | .14* | .46** | .17** | -.26** | |||||

| 8. Parental Knowledge | -.14* | .12 | -.21** | -.27** | -.04 | .50** | -.27** | ||||

| 9. Neighborhood Dangerousness | .27** | -.26** | .28** | .21** | .05 | .30** | .20** | -.09 | |||

| 10. Antisocial Behavior- Youth Report | .07 | -.06 | .10 | .23** | .25** | -.10 | .22** | -.11 | .20** | ||

| 11. Conduct Disorder Symptoms | .04 | -.11 | .04 | .29** | .24** | -.18** | .34** | -.24** | .18** | .58** | |

| 12. Court Petitions | .26** | -.29** | .21** | .43** | .15* | -.23** | .25** | -.32** | .23** | .37** | .44** |

p < .05.

p < .01

Predictors of the Antisocial Latent Factor

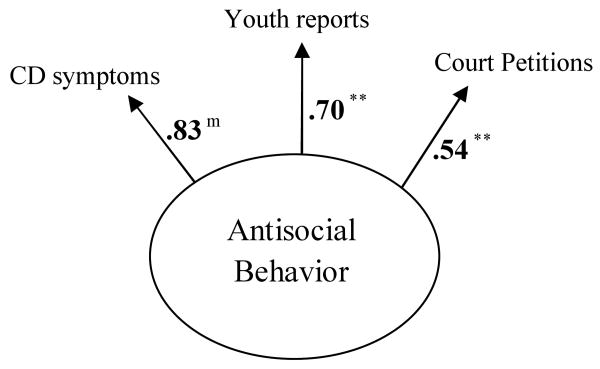

Figure 1 presents the factor loadings for a measurement model of the latent construct for adolescent AB as evaluated in Mplus; the loadings supported examining AB as a single latent construct. Preliminary analyses showed that ethnicity and the SES variables (family income and neighborhood-level SES disadvantage) did not predict the AB construct. Furthermore, inclusion of these covariates only led to poor model fit without affecting the patterns of estimates in the models. Consequently, they were excluded in the model testing described below.

Figure 1. Antisocial Behavior Latent Construct.

m = marker variable. **p < .01.

Note. Standardized factor loadings are presented in the figure.

An initial SEM model included the three adolescent dispositions as predictors of the antisocial construct to examine the unique effect of each disposition while controlling for the effects of the other dispositions. This model demonstrated excellent model fit, with χ2(6) = 4.67 (p > .05), RMSEA = .00, and CFI = 1.00. Furthermore, each adolescent disposition was a statistically significant predictor of the antisocial construct (daring: B = .17, SE = .05, p < .01; prosociality: B = -.15, SE = .04, p < .01; negative emotionality: B = .20, SE = .05, p < .01), accounting for 24% of the AB latent construct's variance. Table 3 presents results of an SEM that examined the three early adolescent dispositions as additive predictors of the AB construct while controlling for middle childhood externalizing problems. This model provided an adequate fit to the data. Although χ2(8) = 17.17 (p < .05) was statistically significant, the χ2/df ratio of 2.15 suggested adequate model fit. The RMSEA and CFI supported reasonable model fit with RMSEA = .06 and CFI = .95. Furthermore, all four individual predictors, including the middle childhood externalizing problems covariate and the three early adolescent dispositions, significantly predicted the AB latent construct at age 15. More specifically, lower levels of prosociality and higher levels of daring and negative emotionality predicted higher levels of AB later in adolescence after accounting for the effect of earlier externalizing problems on later AB1.

Table 3. Early Adolescent Dispositions as Additive Predictors of Antisocial Behavior.

| Variable | B | SE | z | Model R2 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Middle Childhood Externalizing Aggregate | .17 | .06 | 2.91** | .28** |

| Daring | .15 | .05 | 3.23** | |

| Prosociality | -.11 | .04 | -2.57* | |

| Negative Emotionality | .11 | .05 | 2.11* |

p < .05.

p < .01.

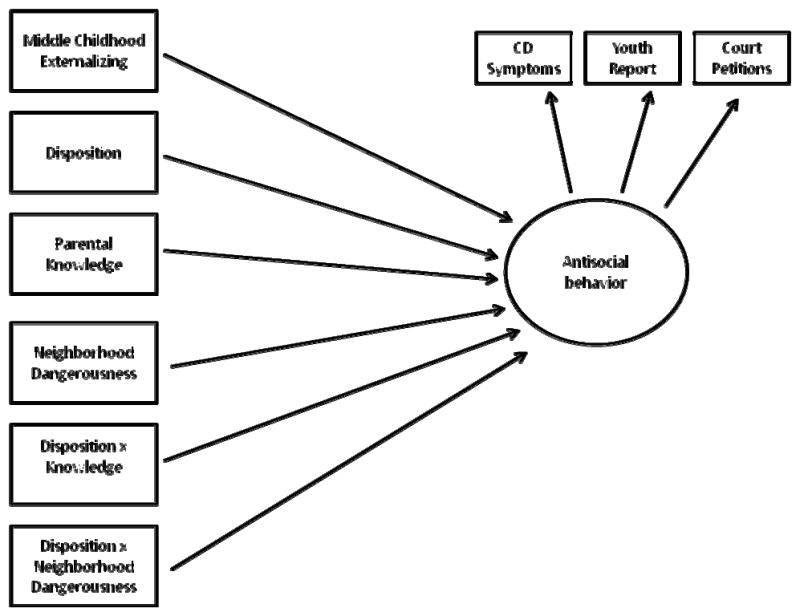

Next, separate models were examined for each dispositional factor in conjunction with the two contextual factors. For each disposition, an initial model evaluated main effects and included the middle childhood externalizing problems covariate, the disposition, and the two contextual factors. Then, follow-up models were estimated to evaluate moderation by including disposition × parental knowledge and disposition × neighborhood dangerousness interaction terms (see Table 4). Each dispositional factor and its interactions with contextual factors were examined separately to minimize multicollinearity. Thus, each follow-up model contained the following predictors: (1) the middle childhood externalizing problems covariate, (2) either daring, prosociality, or negative emotionality, (3) parental knowledge, (4) neighborhood dangerousness, (5) a disposition by parental knowledge interaction term corresponding to either daring, prosociality, or negative emotionality, and (6) a disposition by neighborhood interaction term corresponding to either daring, prosociality, or negative emotionality (see Figure 2). In addition, each model contained correlation terms to account for the association between each pair of exogenous predictors. The disposition scores and the contextual factors were centered prior to the creation of the interaction terms.

Table 4. Early Adolescent Dispositions and Interactions with Contextual Factors as Predictors of Antisocial Behavior.

| Daring | Prosociality | Negative Emotionality | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variable | B | SE | z | B | SE | z | B | SE | z |

| Middle Childhood Externalizing | .19 | .05 | 3.68** | .19 | .05 | 3.59** | .19 | .06 | 3.12** |

| Disposition | .15 | .05 | 3.21** | -.09 | .05 | -1.74a | .11 | .06 | 1.88a |

| Parental Knowledge | -.15 | .06 | -2.62** | -.17 | .06 | -2.69** | -.13 | .06 | -2.22** |

| Neighborhood Dangerousness | .12 | .05 | 2.32* | .13 | .06 | 2.20* | .09 | .06 | 1.66a |

| Disposition × Parental Knowledge | -.05 | .06 | -.73 | -.13 | .05 | -2.57** | .00 | .07 | .00 |

| Disposition × Neighborhood | .13 | .06 | 2.05* | -.10 | .06 | -1.68 a | .08 | .08 | .98 |

p < .10.

p < .05.

p < .01.

Figure 2. Model of Dispositional and Contextual Predictors of Antisocial Behavior.

Note. Correlation terms between pairs of exogenous predictors were included in the models but are not included in the Figure.

Daring

The initial model that examined main effects for daring and the contextual factors demonstrated moderate model fit, with χ2(8) = 26.02 (p < .05), RMSEA = .088, and CFI = .912. Daring and the contextual factors were statistically significant predictors of the antisocial construct while controlling for middle childhood externalizing problems (daring: B = .15, SE = .05, p < .01; parental knowledge: B = -.15, SE = .06, p < .01; neighborhood dangerousness: B = .13, SE = .05, p < .05). In the final model that added daring × parental knowledge and daring × neighborhood interaction terms, model fit was adequate with χ2(12) = 32.70 (p < .01), χ2/df ratio of 2.73, RMSEA = .077 and CFI = .903. Predictors in this model explained 33% of the variance in the AB latent construct. Furthermore, the daring × neighborhood dangerousness interaction term was a significant predictor of the AB latent construct, but the daring × parental knowledge interaction term was not a significant predictor of the AB latent construct. Figure 3 presents a plot of the interaction between daring and neighborhood dangerousness. At high levels of neighborhood dangerousness, there was a significant positive relationship between daring and antisocial behavior. On the other hand, daring was not related to AB in contexts with low levels of neighborhood dangerousness. Tests of simple slopes support this conclusion (t = 3.76, p < .05 when neighborhood dangerousness was 1 SD above the mean; t = .94, p > .05 when neighborhood dangerousness was 1 SD below the mean).

Figure 3. Daring × Neighborhood Dangerousness Interaction.

Prosociality

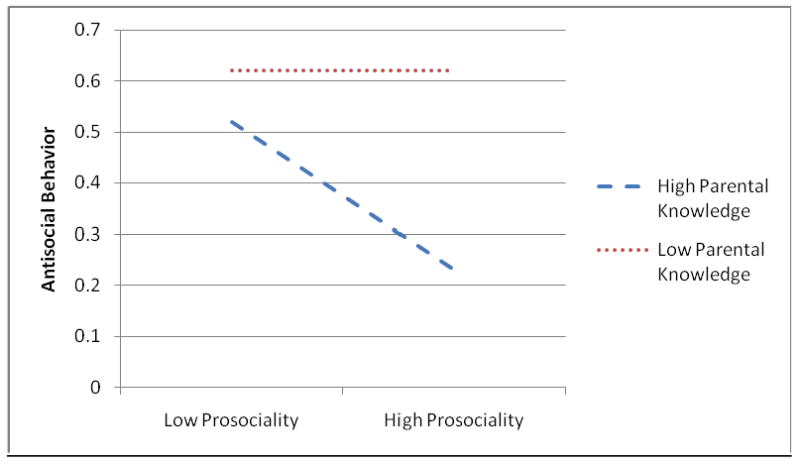

The initial model that examined main effects for prosociality and the contextual factors demonstrated moderate model fit, with χ2(8) = 25.04 (p < .05), RMSEA = .086, and CFI = .915. The contextual factors were statistically significant predictors of the antisocial construct while controlling for middle childhood externalizing problems (parental knowledge: B = -.13, SE = .06, p < .05; neighborhood dangerousness: B = .12, SE = .06, p < .05), but prosociality did not predict the AB latent construct in this model. In the final model that added prosociality × parental knowledge and prosociality × neighborhood dangerousness interaction terms, model fit was adequate with χ2(12) = 30.70 (p < .01), χ2/df ratio of 2.56, RMSEA = .073 and CFI = .911. The interaction between prosociality and parental knowledge was statistically significant, but the prosociality × neighborhood dangerousness interaction term was a non-significant predictor of the AB latent construct. Figure 4 presents a plot of the prosociality × parental knowledge interaction term. Prosociality was negatively related to antisocial behavior in contexts with high levels of parental knowledge, but antisocial behavior was consistently elevated in contexts with low levels of parental knowledge. Tests of simple slopes support this conclusion (t = -2.43, p < .05 when parental knowledge was 1 SD above the mean; t = .07, p > .05 when parental knowledge was 1 SD below the mean).

Figure 4. Prosociality × Parental Knowledge Interaction.

Negative Emotionality

Finally, the initial model that examined main effects for negative emotionality and the contextual factors demonstrated adequate model fit, with χ2(8) = 25.53 (p < .05), RMSEA = .087, and CFI = .911. Parental knowledge was a statistically significant predictor of the antisocial construct while controlling for middle childhood externalizing problems (B = -.14, SE = .06, p < .05), but negative emotionality (B = .11, SE = .06, p < .06) and neighborhood dangerousness were marginally significant predictors (B = .11, SE = .06, p < .07). In the final model that added negative emotionality × parental knowledge and negative emotionality × neighborhood dangerousness interaction terms, model fit was adequate with χ2(12) = 32.15 (p < .01), χ2/df ratio of 2.68, RMSEA = .076 and CFI = .903. However, the interaction terms were not statistically significant predictors of the AB latent construct2.

Discussion

The findings demonstrate the importance of adolescent dispositional characteristics in the development of AB and provide some support for a transactional perspective on the relations among dispositional characteristics, contextual factors, and AB in adolescence. Dispositional characteristics including sensation seeking behaviors, prosocial tendencies, and negative emotionality were additive predictors of adolescent AB. In addition, all three characteristics independently predicted adolescent AB while controlling for earlier AB. All three dispositional characteristics demonstrated modest correlations with middle childhood externalizing problems, making this test a particularly stringent evaluation of the role of the dispositional characteristics as predictors of adolescent AB. These findings add to a relatively large body of literature on temperament and personality characteristics in relation to AB, and a relatively sparse literature simultaneously examining multiple dispositional characteristics as additive predictors of AB (Lahey et al., 2008). Moreover, these relations were found in an ethnically diverse sample during early adolescence. Intercorrelations between these three dispositional characteristics ranged from non-significant to modest, further supporting these three dispositional qualities as relatively independent risk factors in the development of AB during adolescence.

In accord with a transactional perspective on the development of psychopathology (Sameroff, 2000), contextual factors appeared to moderate the relations between adolescent dispositional characteristics and antisocial outcomes. Specifically, the association between daring and AB was qualified, such that daring was associated with AB in the context of high neighborhood dangerousness. This finding is consistent with previous research that found associations between youth impulsivity and AB to be amplified in low SES neighborhoods (Lynam et al., 2000; Meier et al., 2008). The current finding suggests that boys who enjoy high-excitement activities but live in lower risk neighborhoods are somewhat protected from developing serious AB relative to peers with similar levels of daring dispositions living in more adverse contexts. Daring boys living in lower risk neighborhoods may become involved in somewhat more adaptive outlets for their sensation seeking tendencies such as high-intensity sports. However, it is important to note that involvement in organized sports is not consistently associated with positive outcomes (Eccles & Barber, 1999; Fredricks & Eccles, 2008), and research is needed on the most adaptive outlets for risk-taking tendencies during adolescence. On the other hand, the combination of interest in risk-taking activities and a relatively dangerous neighborhood context may set the stage for serious AB in adolescence. Interventions aimed at preventing AB among risk-taking males may be most beneficial if they target communities beset by high levels of crime and related neighborhood risk. Alternately, interventions that help families move into safer neighborhoods may help protect children with risky dispositions (Leventhal & Brooks-Gunn, 2003).

Also supporting the transactional perspective, prosocial tendencies were associated with lower levels of AB in the context of high parental knowledge. In family contexts characterized by low parental knowledge, there was no relationship between prosociality and AB. Although generally supportive of a transactional perspective, these findings did not entirely fit with predictions. Specifically, we expected that high levels of parental knowledge would protect boys with lower prosociality from becoming involved in deviant behavior, whereas lower levels of parental knowledge would be particularly harmful for boys with fewer prosocial tendencies. Instead, it appears that in the context of low parental knowledge, boys engaged in elevated levels of AB regardless of their level of prosociality. This finding suggests that prosocial tendencies such as friendliness and a desire to share with others may offer little protection from AB when parents are not as aware of their young adolescent's activities and whereabouts.

The current findings are particularly supportive of the assertion that parental knowledge is a key predictor of AB because variance associated with earlier externalizing problems, adolescent dispositions, and neighborhood dangerousness were accounted for in analyses. Parental knowledge was a direct predictor of AB in addition to its role as a moderator of the relation between prosociality and AB. These findings add to a growing body of literature on youth-reported parental knowledge and delinquent behavior outcomes during adolescence (e.g., Laird et al., 2003). The findings on prosociality, parental knowledge, and AB suggest that programs aimed to promote social skills and empathy in order to reduce problematic delinquent behaviors may be more beneficial for boys living in families with open communication. In families with lower levels of communication about the adolescent's activities and whereabouts, promoting prosocial tendencies may do little to protect against involvement in AB.

The relationship between prosociality, parental knowledge, and AB is also interesting when compared to the findings by Wootton and colleagues (Wootton, Frick, Shelton, & Silverthorn, 1997). In their study, ineffective parenting was associated with conduct problems only for children without elevated levels of callous/unemotional traits; children with high callousness had more conduct problems regardless of the quality of parenting. The present findings suggest that a similar relation exists among dispositional characteristics, the parenting context, and the development of AB when using a measure of parenting that is specific to the adolescent period (parental knowledge).

Although this study supported two key moderational hypotheses that fit with a transactional perspective, other hypotheses were not supported. For example, interactions between daring tendencies and parental knowledge and between prosociality and neighborhood dangerousness were not found. Furthermore, contextual moderation was not supported for negative emotionality. Also, prosociality was a non-significant predictor of the AB latent construct and negative emotionality was a marginally significant predictor of the AB latent construct in models that accounted for the contribution of contextual factors.

Limitations

The present findings are limited by several methodological characteristics involving selection of the study's sample. First, this longitudinal study focused on boys, and it is possible that an examination of girls' dispositional qualities and their interaction with contextual factors would lead to different conclusions. For example, negative emotionality may be a more sensitive predictor of AB in girls. Also, prosocial and daring tendencies may be respectively more and less normative among girls, and this variation may impact the magnitude of relations with AB and the relative influence of contextual moderators. Furthermore, the current sample was originally recruited from WIC nutrition supplement centers, meaning that families faced financial hardships and other correlates of financial adversity (e.g., living in poor neighborhoods, attending schools with limited resources) during this longitudinal study. Even with a relatively low SES sample, boys lived in a diverse range of neighborhoods as demonstrated by previous research with this sample (Vanderbilt-Adriance & Shaw, 2008). Nonetheless, findings for interactions between dispositional qualities and contextual factors may differ with a sample that is more representative of the broader United States population, with neighborhood effects on child problem behavior typically limited to lower-SES communities. Second, families were recruited from a large metropolitan area located in an urban environment; thus, it is unclear whether similar results would be found in rural or suburban contexts for boys or girls.

Although our measure selection was designed to include multiple perspectives on boys' behavior and dispositions, we were limited to primary caregiver and adolescent reports of dispositional qualities at a single time point (i.e., formal transactional models were not tested). Primary caregiver and adolescent reports were moderately correlated for two of the dispositional factors of daring and prosociality, but were relatively smaller in magnitude, although statistically significant, for the third dispositional factor of negative emotionality. Future research is needed to assess primary caregiver and adolescent agreement on assessments of dispositional traits, and the relatively modest agreement between primary caregivers and adolescent boys in the present study may have attenuated the predictive validity of dispositional qualities in relation to AB.

Future Directions and Implications

The present findings suggest that adolescent dispositional qualities are key risk factors for AB, but that these qualities are best considered in conjunction with the adolescent's context. In addition, the findings suggest that there are certain contextual characteristics (low levels of parental knowledge, lower risk neighborhoods) that may attenuate the relation between specific dispositional qualities and AB outcomes. Future research could consider a more complex interplay of dispositional characteristics and multiple contextual factors. For example, parenting appears to be an important moderator of the relation between neighborhood quality and problem behaviors (Brody et al., 2001; Supplee, Unikel, & Shaw, 2007), and research with larger samples could consider three-way interactions involving parenting, neighborhood quality, and dispositional characteristics.

The results have potential practical applications. Programs aimed at preventing or intervening on adolescent AB would benefit from tailoring interventions to specific adolescent dispositions and their parenting and neighborhood contexts. Programs that target adolescent dispositional characteristics may not be as effective in particular contextual circumstances, and efforts to alter or support adaptations to the family and neighborhood context may be particularly useful. Also, programs that target contextual systems relevant to the adolescent (e.g., Henggeler, Schoenwald, Borduin, Rowland, & Cunningham, 1998) may show benefits when the adolescent's dispositional risk is considered along with the systemic foci of the intervention.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by grant R01 MH050907 from the National Institutes of Health to Daniel S. Shaw. We thank the staff of the Pitt Mother & Child Project and the study families for making the research possible. We also extend our appreciation to Heather Gross for gathering the court records.

Footnotes

In a similar model with the same covariates but with primary caregiver and adolescent reports of negative emotionality as separate predictors, χ2(10) = 24.56 (p < .01), and the χ2/df ratio of 2.46. The RMSEA and CFI supported adequate model fit with RMSEA = .07 and CFI = .93. In this model, neither primary caregiver reports of negative emotionality nor target reports of negative emotionality significantly predicted the antisocial construct while controlling for middle childhood externalizing problems, daring, and prosociality.

When this model was run separately for primary caregiver and adolescent reports of negative emotionality, the same pattern of results emerged in each model. Specifically, parental knowledge was a significant predictor in each model, neighborhood dangerousness was marginally significant, and the interaction terms were non-significant. However, negative emotionality was not a significant predictor in either model.

Publisher's Disclaimer: The following manuscript is the final accepted manuscript. It has not been subjected to the final copyediting, fact-checking, and proofreading required for formal publication. It is not the definitive, publisher-authenticated version. The American Psychological Association and its Council of Editors disclaim any responsibility or liabilities for errors or omissions of this manuscript version, any version derived from this manuscript by NIH, or other third parties. The published version is available at www.apa.org/pubs/journals/abn.

Contributor Information

Christopher J. Trentacosta, Wayne State University

Luke W. Hyde, University of Pittsburgh

Daniel S. Shaw, University of Pittsburgh

JeeWon Cheong, University of Pittsburgh.

References

- Achenbach TM. Manual for the Child Behavior Checklist/4-18 and 1991 profiles. Burlington, VT: University of Vermont, Department of Psychiatry; 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Aguilar B, Sroufe L, Egeland B, Carlson E. Distinguishing the early-onset/persistent and adolescence-onset antisocial behavior types: From birth to 16 years. Development and Psychopathology. 2000;12:109–132. doi: 10.1017/s0954579400002017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aiken LS, West SG. Multiple regression: Testing and interpreting interactions. Newbury Park, CA: Sage; 1991. [Google Scholar]

- American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders, (Fourth Edition text revision) Arlington, VA: APA; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Arnett JJ. Sensation seeking, aggressiveness, and adolescent reckless behavior. Personality and Individual Differences. 1996;20:693–702. [Google Scholar]

- Barry CT, Frick PJ, DeShazo TM, McCoy M, Ellis M, Loney BR. The importance of callous-unemotional traits for extending the concept of psychopathy to children. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 2000;109:335–340. doi: 10.1037/0021-843X.109.2.335. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bates JE, Maslin CA, Frankel KA. Attachment security, mother-child interaction, and temperament as predictors of behavior-problem ratings at age three years. In: Bretherton I, Waters E, editors. Monographs of the Society for Research in Child Development. Vol. 50. 1985. pp. 1–2.pp. 167–193. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brody GH, Ge X, Conger R, Gibbons FX, Murry VM, Gerrard M, et al. The effect of neighborhood disadvantage, collective socialization, and parenting on African American children's affiliation with deviant peers. Child Development. 2001;72:1231–1246. doi: 10.1111/1467-8624.00344. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Campbell SB, Shaw DS, Gilliom M. Early externalizing behavior problems: Toddlers and preschoolers at risk for later maladjustment. Development and Psychopathology. 2000;12:467–488. doi: 10.1017/s0954579400003114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clark LA, Watson D. Tripartite model of anxiety and depression: Psychometric evidence and taxonomic implications. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 1991;100:316–336. doi: 10.1037//0021-843x.100.3.316. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Colder CR, Lengua LJ, Fite PJ, Mott JA, Bush NR. Temperament in context: Infant temperament moderates the relationship between perceived neighborhood quality and behavior problems. Journal of Applied Developmental Psychology. 2006;27:456–467. doi: 10.1016/j.appdev.2006.06.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dadderman AM. Differences between severely conduct-disordered juvenile males and normal juvenile males: The study of personality traits. Personality and Individual Differences. 1999;26:827–845. [Google Scholar]

- Dishion TJ, McMahon R. Parental monitoring and the prevention of child and adolescent problem behavior: A conceptual and empirical formulation. Clinical Child and Family Psychology Review. 1998;1:61–75. doi: 10.1023/a:1021800432380. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dishion TJ, Patterson GR. The development and ecology of antisocial behavior in children and adolescents. In: Cicchetti D, Cohen DJ, editors. Developmental Psychopathology, Volume 3: Risk, Disorder, and Adaptation. 2nd. Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley & Sons; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Dishion TJ, Patterson GR, Stoolmiller M, Skinner ML. Family, school, and behavioral antecedents to early adolescent involvement with antisocial peers. Developmental Psychology. 1991;27:172–180. [Google Scholar]

- Dodge KA, Coie JD, Lynam D. Aggression and antisocial behavior in youth. In: Damon W, Lerner RM, Eisenberg N, editors. Handbook of Child Psychology: Social, emotional, and personality development. Sixth. Vol. 3. New York: John Wiley and Sons; 2006. pp. 719–788. [Google Scholar]

- Eccles JS, Barber BL. Student council, volunteering, basketball, or marching band: What kind of extracurricular involvement matters? Journal of Adolescent Research. 1999;14:10–43. [Google Scholar]

- Eisenberg N, Cumberland A, Spinrad TL, Fabes RA, Shepard SA, Reiser M, et al. The relations of regulation and emotionality to children's externalizing and internalizing problem behavior. Child Development. 2001;72:1112–1134. doi: 10.1111/1467-8624.00337. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eisenberg N, Fabes RA, Guthrie IK, Murphy B, Maszk P, Holmgren R, et al. The relations of regulation and emotionality to problem behavior in elementary school children. Development and Psychopathology. 1996;8:141–162. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eisenberg N, Hofer C, Vaughan J. Effortful control and its socioemotional consequences. In: Gross JJ, editor. Handbook of emotion regulation. New York: The Guilford Press; 2007. pp. 387–306. [Google Scholar]

- Elliot DS, Huizinga D, Ageton SS. Explaining delinquency and drug use. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage; 1985. [Google Scholar]

- Ewart CK, Suchday S. Discovering how urban poverty and violence affect helath: Development and validation of a neighborhood stress index. Health Psychology. 2002;21:254–262. doi: 10.1037//0278-6133.21.3.254. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eysenck HJ. Psychology and crime: Where do we stand? Psychology, Crime, and Law. 1996;2:143–152. [Google Scholar]

- Farrington DP. The development of offending and antisocial behavior from childhood: Key findings from the Cambridge Study in Delinquent Development. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry. 1995;36:929–964. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.1995.tb01342.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Farrington DP, West DJ. Criminal, penal and life histories of chronic offenders: Risk and protective factors and early identification. Criminal Behaviour & Mental Health. 1993;3:492–523. [Google Scholar]

- Fredricks JA, Eccles JS. Participation in extracurricular activities in the middle school years: Are there developmental benefits for African American and European American youth? Journal of Youth and Adolescence. 2008;37:1029–1043. [Google Scholar]

- Frick PJ, Morris AS. Temperament and developmental pathways to conduct problems. Journal of Clinical Child and Adolescent Psychology. 2004;33:54–68. doi: 10.1207/S15374424JCCP3301_6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gottfredson M, Hirschi T. A general theory of crime. Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press; 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Greenberg MT, Speltz ML. Contributions of attachment theory to the understanding of conduct problems during the preschool years. In: Belsky J, Negworski T, editors. Clinical implications of attachment. Hillsdale, NJ: Earlbaum; 1988. pp. 177–218. [Google Scholar]

- Haemaelaeinen M, Pulkkinen L. Problem behavior as a precursor of male criminality. Development and Psychopathology. 1996;8:443–455. [Google Scholar]

- Henggeler SW, Schoenwald SK, Borduin CM, Rowland MD, Cunningham PB. Multisystemic treatment of antisocial behavior in children and adolescents. New York: The Guilford Press; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Hirschi T. Causes of Delinquency. Berkeley, CA: University of California; 1969. [Google Scholar]

- Holmbeck GN. Post-hoc probing of significant moderational and mediational effects in studies of pediatric populations. Journal of Pediatric Psychology. 2002;27:87–96. doi: 10.1093/jpepsy/27.1.87. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- John OP, Caspi A, Robins RW, Moffitt TE, Stouthamer-Loeber M. The “little five”: Exploring the nomological network of the five-factor model of personality in adolescent boys. Child Development. 1994;65:160–178. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kagan J, Reznick JS, Snidman N. Biological bases of childhood shyness. Science. 1988;240:167–171. doi: 10.1126/science.3353713. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaufman J, Birmaher B, Brent D, Rao U. Schedule for Affective Disorders and Schizophrenia for School-Age Children-Present and Lifetime version (K-SADS-PL): Initial reliability and validity data. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry. 1997;36:980–988. doi: 10.1097/00004583-199707000-00021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krueger RF. Personality traits in late adolescence predict mental disorders in early adulthood: A prospective-epidemiologic study. Journal of Personality. 1999;67:39–65. doi: 10.1111/1467-6494.00047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lahey BB, Applegate D, Chronis AM, Jones HA, Williams SH, Loney J, Waldman ID. Psychometric characteristics of a measure of emotional dispositions developed to test a developmental propensity model of conduct disorder. Journal of Child Clinical and Adolescent Psychology. 2008;37:794–807. doi: 10.1080/15374410802359635. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lahey BB, Waldman ID. A developmental propensity model of the origins of conduct problems during childhood and adolescence. In: Lahey BB, Moffitt TE, Caspi A, editors. The causes of conduct disorder and serious juvenile delinquency. New York: Guilford Press; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Lahey BB, Waldman ID, McBurnett K. Annotation: The development of antisocial behavior: An integrative causal model. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry. 1999;40:669–682. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laird RD, Pettit GS, Bates JE, Dodge K. Parents' monitoring-relevent knowledge and adolescents' delinquent behavior: Evidence of correlated developmental changes and reciprocal influences. Child Development. 2003;74:752–768. doi: 10.1111/1467-8624.00566. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leventhal T, Brooks-Gunn J. The neighborhoods they live in: The effects of neighborhood residence on child and adolescent outcomes. Psychological Bulletin. 2000;126:309–337. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.126.2.309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leventhal T, Brooks-Gunn J. Moving to Opportunity: An experimental study of neighborhood effects on mental health. American Journal of Public Health. 2003;93:1576–1582. doi: 10.2105/ajph.93.9.1576. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lynam DR, Caspi A, Moffitt TE, Wikstrom POH, Loeber R, Novak S. The interaction between impulsivity and neighborhood context on offending: The effects of impulsivity are stronger in poorer neighborhoods. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 2000;109:563–574. doi: 10.1037//0021-843x.109.4.563. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCabe KM, Lucchini SE, Hough RL, Yeh M, Hazen A. The relation between violence exposure and conduct problems among adolescents: a prospective study. American Journal of Orthopsychiatry. 2005;75:575–584. doi: 10.1037/0002-9432.75.4.575. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCrae RR, Costa PT., J Personality trait structure as a human universal. American Psychologist. 1997;52:509–516. doi: 10.1037//0003-066x.52.5.509. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meier MH, Slutske WS, Arndt S, Cadoret RJ. Impulsive and callous traits are more strongly associated with delinquent behavior in higher risk neighborhoods among boys and girls. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 2008;117:377–385. doi: 10.1037/0021-843X.117.2.377. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moffitt TE, Caspi A, Harrington H, Milne BJ. Males on the life-course-persistent and adolescence-limited antisocial pathways: Follow-up at age 26 years. Development and Psychopathology. 2002;14:179–207. doi: 10.1017/s0954579402001104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moilanen KL, Shaw DS, Criss M, Dishion TJ. Growth and predictors of parental knowledge of youth behavior during early adolescence. Journal of Early Adolescence. doi: 10.1177/0272431608325505. in press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muthén LK, Muthén BO. Mplus User's Guide. 5th. Los Angeles, CA: Muthén & Muthén; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Nigg JT. Temperament and developmental psychopathology. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry. 2006;47:395–422. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.2006.01612.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ng-Mak DS, Salzinger S, Feldman RS, Stueve CA. Pathological adaptation to community violence among inner-city youth. American Journal of Orthopsychiatry. 2004;74:196–208. doi: 10.1037/0002-9432.74.2.196. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Owens EB, Shaw DS. Predicting growth curves of externalizing behavior across the preschool years. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology. 2003;31:575–590. doi: 10.1023/a:1026254005632. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patterson GR, Reid JB, Dishion TJ. Antisocial boys. Eugene, OR: Castalia; 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Rothbart M, Ahadi S, Evans D. Temperament and personality: Origins and outcomes. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 2000;78:122–135. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.78.1.122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rothbart M, Posner M, Hershey K. Temperament, attention, and developmental psychopathology. In: Cicchetti D, Cohen D, editors. Developmental Psychopathology. New York: Wiley; 1995. pp. 315–326. [Google Scholar]

- Sameroff AJ. Developmental systems and psychopathology. Development and Psychopathology. 2000;12:297–312. doi: 10.1017/s0954579400003035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sameroff AJ, Mackenzie MJ. Research strategies for capturing transactional models of development: The limits of the possible. Development and Psychopathology. 2003;15:613–640. doi: 10.1017/s0954579403000312. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shaw DS, Bell RQ. Developmental theories of parental contributors to antisocial behavior. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology. 1993;21:493–518. doi: 10.1007/BF00916316. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shaw DS, Gilliom M, Ingoldsby EM, Nagin DN. Trajectories leading to school-age conduct problems. Developmental Psychology. 2003;39:189–200. doi: 10.1037//0012-1649.39.2.189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shiner R, Caspi A. Personality differences in childhood and adolescence: measurement, development, and consequences. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry. 2003;44:2–32. doi: 10.1111/1469-7610.00101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smetana JG. “It's 10 o'clock: Do you know where your children are?” Recent advances in understanding parental monitoring and adolescents' information management. Child Development Perspectives. 2008;2:1–52. [Google Scholar]

- Stattin H, Kerr M. Parental monitoring: A reinterpretation. Child Development. 2000;71:1072–1085. doi: 10.1111/1467-8624.00210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Supplee LH, Unikel EB, Shaw DS. Physical environment adversity and the protective role of maternal monitoring in relation to early childhood conduct problems. Journal of Applied Developmental Psychology. 2007;28:166–183. doi: 10.1016/j.appdev.2006.12.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vanderbilt-Adriance E, Shaw DS. Protective factors and the development of resilience among boys from low-income families. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology. 2008;36:887–901. doi: 10.1007/s10802-008-9220-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wachs TD, Bates JE. Temperament. In: Bremner G, Fogel A, editors. Blackwell handbook of infant development. Oxford, UK: Blackwell; 2001. pp. 465–501. [Google Scholar]

- Weintraub K, Gold M. Monitoring and delinquency. Criminal Behavior and Mental Health. 1991;1:268–281. [Google Scholar]

- Wootton JM, Frick PJ, Shelton KK, Silverthorn P. Ineffective parenting and childhood conduct problems: The moderating role of callous-unemotional traits. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 1997;65:301–308. doi: 10.1037/0022-006x.65.2.292.b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]