Abstract

Receptor tyrosine kinase (RTK) systems, such as hepatocyte growth factor (HGF) and its receptor c-Met, and EGFR, are responsible for the malignant progression of multiple solid tumors. Recent research shows that these RTK systems co-modulate overlapping and dynamically adaptable oncogenic downstream signaling pathways. This paper investigates how EGFRvIII, a constitutively active EGFR deletion mutant, alters tumor growth and signaling responses to RTK inhibition in PTEN-null/HGF+/c-Met+ glioma xenografts. We show that a neutralizing anti-HGF mAb (L2G7) potently inhibits tumor growth and the activation of Akt and MAPK in PTEN-null/HGF+/c-Met+/EGFRvIII−U87 glioma xenografts (U87wt). Isogenic EGFRvIII+ U87 xenografts (U87-EGFRvIII), which grew 5-times more rapidly than U87-wt xenografts, were unresponsive to EGFRvIII inhibition by erlotinib and were only minimally responsive to anti-HGF mAb. EGFRvIII-expression diminished the magnitude of Akt inhibition and completely prevented MAPK inhibition by L2G7. Despite the lack of response to L2G7 or erlotinib as single agents, their combination synergized to produce substantial anti-tumor effects (inhibited tumor cell proliferation, enhanced apoptosis, arrested tumor growth, prolonged animal survival), against subcutaneous and orthotopic U87-EGFRvIII xenografts. The dramatic response to combining HGF:c-Met and EGFRvIII pathway inhibitors in U87-EGFRvIII xenografts occurred in the absence of Akt and MAPK inhibition. These findings show that combining c-Met and EGFRvIII pathway inhibitors can generate potent anti-tumor effects in PTEN-null tumors. They also provide insights into how EGFRvIII and c-Met may alter signaling networks and reveal the potential limitations of certain biochemical biomarkers to predict the efficacy of RTK inhibition in genetically diverse cancers.

Keywords: Hepatocyte growth factor, c-Met, epidermal growth factor receptor, erlotinib, Akt, MAPK

INTRODUCTION

Understanding the molecular/genetic background of cancer has provided a foundation for targeted molecular therapies. Receptor tyrosine kinases (RTKs) and their cognate ligands are key modulators of intracellular signaling and have emerged as potent regulators of molecular/cellular events involved in tumor malignancy. Common oncogenic changes in RTK/ligand systems include over-expression, gene amplification, activating mutations, and activating deletions. Examples include amplification of platelet derived growth factor receptor (pdgfr), and epidermal growth factor receptor (egfr), overexpression of c-Met and/or its cognate ligand hepatocyte growth factor/scatter factor (HGF), activating c-Met and EGFR mutations, and the most common egfr gene rearrangement - EGFRvIII (an in-frame deletion of amino acids 6–273 resulting in a constitutively activated receptor) (1). Co-expression of multiple RTK aberrations can activate overlapping and/or parallel oncogenic pathways in a multitude of genetically heterogeneous solid tumors (1). These parallel and overlapping pathways have the potential to limit the efficacy of single agent targeted therapeutics and offer potential mechanisms for drug resistance. This is exemplified by recent findings that c-Met pathway activation can provide a mechanism by which lung carcinomas escape EGFR inhibitors (2, 3). Recent in vitro experiments have revealed a phenomenon termed “RTK switching” whereby distinct RTKs act as independent but redundant inputs to maintain flux through downstream oncogenic signaling pathways when the seemingly dominant RTK is inhibited (4).

The HGF:c-Met pathway is overactivated by receptor/ligand overexpression and less commonly by activating receptor mutations or c-Met gene amplification in many solid tumors including bladder, breast, colorectal, gastric, head and neck, kidney, liver, lung, pancreas, prostate, and thyroid carcinomas, gliomas, sarcomas, melanomas and leukemias (5). HGF:c-Met pathway activation is associated with malignant progression and poor prognosis in many of these cancers (Also see www.vai.org/met) (5). C-Met efficiently activates the PI3K/Akt and Ras/MAPK pathways that together contribute to the malignant phenotype of many tumor subtypes. Pre-clinical in vitro and in vivo findings show that activating tumor and stromal cell c-Met by tumor- and stromal cell-derived HGF stimulates tumor angiogenesis, cell proliferation, migration/invasion, and resistance to various cytotoxic stimuli (6–8). These clinical associations and experimental data have stimulated the development of agents to therapeutically target HGF:c-Met signaling. These include anti-HGF neutralizing monoclonal antibodies (9, 10), a one-armed anti-c-Met antibody (11) and small molecule c-Met tyrosine kinase inhibitors (4, 12–14). The relatively high frequency of redundant tumor promoting pathways makes it imperative that we understand their influence on the efficacy of HGF:c-Met pathway inhibitors.

This paper investigates whether EGFR pathway hyperactivation, which occurs in ≥40% of human glioblastoma, alters tumor responses to anti-HGF therapeutics. Using xenografts derived from isogenic cell lines, we show that EGFRvIII renders PTEN-null/HGF+/c-Met+ glioma xenografts relatively unresponsive to HGF:c-Met pathway inhibition. The diminished tumor responsiveness to HGF:c-Met pathway inhibition in the context of constitutive EGFRvIII expression was associated with a complete abrogation of MAPK pathway inhibition and only a partial abrogation of Akt inhibition. In contrast to the poor tumor response to either HGF:c-Met or EGFRvIII pathway inhibitors, their combination synergized to produce substantial anti-tumor effects against PTEN-null/HGF+/c-Met+/EGFRvIII+ tumors. The synergistic anti-tumor effects of combining EGFR and c-Met pathway inhibition have important implications for the development of effective strategies that target these signaling pathways in malignant glioma and potentially other solid malignancies.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Cell Culture and Reagents

U87MG cell lines were originally obtained from American Type Culture Collection (ATCC) and grown in Minimum Essential Medium w/Earle Salts and L-glutamine (MEM 1X; Mediatech Inc. Inc.) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS; Gemini Bioproducts Inc.), 2 mM Sodium Pyruvate (Mediatech Inc.), 0.1 mM MEM-Non-essential Amino Acids (Mediatech Inc.) and penicillin-streptomycin (Mediatech Inc.). U87-EGFRvIII cells were a kind gift of Dr. Gregory Riggins (15, 16), Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine and were grown in Dulbecco’s Modified Essential Medium high glucose with L-glutamine and sodium pyruvate- (DMEM; Mediatech Inc. Inc.) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum, 1% of 10 mM MEM-non-essential Amino Acids andpenicillin-streptomycin as previously described (17). All cells were grown at 37°C in a humidified incubator with 5% CO2.

Tumor xenografts

Glioma xenografts were generated as previously described (17). Female 6- to 8-week-old mice (National Cancer Institute, Frederick, MD) were anesthetized by i.p. injection of ketamine (100 mg/kg) and xylazine (5 mg/kg).

For subcutaneous xenografts, nu/nu mice received 4 × 106 cells in 0.05 mL of PBS s.c. in the dorsal flank. When tumors reached 200 mm3, the mice were randomly divided into groups (n = 5 per group) and received the indicated doses of either L2G7 or isotype matched control mAb (5G8) in 0.1 ml PBS i.p. as previously described (9). Tumor volumes were estimated by measuring two dimensions [length (a) and width (b)] and calculated using the equation: V = ab2/2 (9, 18). At the end of each experiment, tumors were excised, frozen in liquid nitrogen and protein was extracted for immunoblot analysis. Tumor doubling time (DT) was calculated using the formula: DT=(t2−t1)ln2/ln(V2/V1) (19).

For intracranial xenografts, Scid/beige mice received 1×105 cells/2 μl by stereotaxic injection into the right caudate/putamen (17). L2G7 or 5G8 mAb was administered i.p twice per week as described. Groups of mice (n = 5) were sacrificed by perfusion fixation at the indicated times and the brains removed for histologic studies. Tumor volumes were quantified by measuring the largest tumor cross-sectional area on H&E-stained cryostat sections using computer-assisted image analysis as previously described (17). Tumor volumes were estimated based on the formula: vol = (sq. root of maximum cross-sectional area)3 (20).

Antibodies

Antibodies were obtained from the following sources and used at the indicated dilutions: Cell Signaling Technology (Beverly, MA), p-EGFR Tyr845 (Rabbit, 1:750), cleaved caspase-3 (Rabbit, 1:150) and EGFR (Rabbit, 1:1,000), phospho-Akt-serine473 (Rabbit, 1:1000), phospho- p44/42 MAPK-threonine202/tyrosine204 (Rabbit, 1:1000), phospho-Met-tyrosine1234/1235 (Rabbit, 1:500), and total-Met (Mouse, 1:200); Santa Cruz Biotechnology (Santa Cruz, CA), actin (Rabbit, C-11; 1:1,000); BD Sciences (San Jose, CA), total Akt (Mouse, 1:500), total MAPK (Mouse, 1:1000); LI-COR Biosciences (Lincoln, NE), secondary antibodies labeled with spectrally distinct near-infrared dyes IRDye 800CW (goat anti-mouse, 1:15,000) and IRDye 680CW (goat anti-Rabbit, 1:20,000); Ventana Medical Systems (Tucson, AZ) anti-Ki67-K2, and Life Technologies/Invitrogen (Carlsbad, CA) anti-laminin (Rabbit, 1:1,000).

L2G7 Iodination

Radioiodine [125I]NaI, carrier-free, 2,125 Ci/mmol) was purchased from MP Biomedicals (Costa Mesa, CA). Purified mAb was iodinated using the IODO-GEN method from Pierce (Rockford, IL) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Conjugated mAb was subjected to Sephadex G-25 desalting column chromatography (Amersham Biosciences, Piscataway, NJ) to remove unincorporated radioiodine. Radiochemical yields were typically 30–40%. Radiochemical purity met or exceeded 95% as determined by instant thin-layer chromatography. Specific radioactivities typically ranged from 150–180 μCi/μg. Antibodies were used for biodistribution studies within 1 h of radiolabeling. Retention of HGF binding activity following radioiodination was comparable to unlabeled L2G7 as determined by ELISA.

Biodistribution of L2G7

SCID mice bearing glioma xenografts received a single tail vein injection of ~70 Becquerels (Bq) of [125I]L2G7. Three to four mice were sacrificed at each time point. Portions of ipsilateral brain hemispheres containing tumor xenograft, contralateral tumor-free hemisphere, and other organs were removed. The organs were weighed and the tissue radioactivity measured with an automated gamma counter (1282 Compugamma CS, Pharmacia/LKB Nuclear, Inc, Gaithersburg, MD). The percent-injected dose per gram of tissue (% ID/g) was calculated by comparison with samples of a standard dilution of the initial dose. All measurements were corrected for radioactive decay.

Single photon emission computerized tomography with CT scanning (SPECT-CT) was performed essentially as previously reported with minor modifications (21). Mice received ~37 MBq of [125I]L2G7 in saline by single tail vein injection. Every 48 hours, the mice were anesthetized using 3% isoflurane in oxygen and maintained using 1% isoflurane in oxygen. The mice were positioned on the X-SPECT (Gamma Medica, Northridge, CA) gantry and scanned using two low energy, high-resolution pinhole collimators (Gamma Medica) rotating through 360° in 6° increments for 60 seconds per increment. Immediately following SPECT acquisition, we scanned the mice by CT (X-SPECT) over a 4.6 cm field-of-view using a 600 μA, 50 kV beam. The SPECT and CT data were co-registered using commercially available software (Gamma Medica, Northridge, CA) and displayed using AMIDE (http://amide.sourceforge.net/).

Erlotinib tablets (Genentech, Inc., South San Francisco, CA) were crushed and suspended in Ora-Plus Oral Suspending Vehicle (Paddock Laboratories, Inc., Minneapolis, MN) and then diluted 4-fold in PBS. Animals received 0.2 ml of the erlotinib solution (150 mg/kg) by oral gavage six days/week as previously described (22).

The Johns Hopkins University Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee approved all animal protocols used in this study.

Immunohistochemistry

Cryostat sections were stained with anti-cleaved caspase-3 and anti-MIB-1 antibodies as previously described (17). Biotinylated-conjugated secondary antibodies followed by incubation with 3,3′-diaminobenzidine peroxidase substrate was used to detect primary Abs. Anti-MIB-1 and anti-cleaved caspase 3 stained sections were counterstained with Gill’s hematoxylin solution and Methyl Green, respectively. Proliferation and apoptotic indices were determined by computer-assisted quantification using ImageJ Software (rsb.info.nih.gov/ij/) essentially as previously reported (17).

Immunoblot analyses

Total protein was extracted from glioma xenografts and from cells using radioimmunoprecipitation assay (RIPA) buffer (1% Igepal, 0.5% sodium deoxycholate, and0.1% SDS in PBS) containing fresh 1X protease and 1X phosphatase inhibitors (Calbiochem) at 4°C. Tissue extracts were sonicated on ice and centrifuged at 5,000 RPM at 4°C for 5 minutes. Supernatants were assayed for protein concentrations by Coomassie protein assay(Pierce) according to the manufacturer’s recommendations. Aliquots of 40μg of total protein were combined with Laemmli loading buffer containing β-mercaptoethanol and subjected to SDS-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (PAGE) according to the method of Towbin et al. with some modifications (23, 24). For immunoblot analyses, proteins were electrophoretically transferred to nitrocellulose membranes with a semidry transfer apparatus (GE Healthcare) at 50 mA for 60 minutes. Membranes were subjected to quantitative dual wavelength infrared immunofluorescence using the methods described by Kearn et al. (25)(also see www.licor.com). This method allows the quantification of phosphorylated relative to the respective total protein species in the same samples by simultaneously staining blots with two secondary antibodies conjugated with spectrally distinct near-infrared dyes. Membranes were incubated for 1 h in Odyssey Licor Blocking Buffer at room temperature and then overnight simultaneously with both relevant primary antibodies (anti-phospho and anti-total) at 4°C in 5% BSA in Tris-buffered saline (TBS) containing 0.1% Tween 20 (TBS/T). Membranes were then washed 3 X withTBS/T, incubated simultaneously with two secondary antibodies (IRDye 800CW goat anti-mouse 1:15,000, IRDye 680CW goat anti-Rabbit 1:20,000; LI-COR Biosciences) for 1 h in TBS/T, washed 3 X with TBS/T, followed by washing 2 X with TBS. Proteins were detected and quantified using the Odyssey Infrared Imager (LI-COR Biosciences).

Statistical methods

Statistical analysis consisted of one-way ANOVA followed by the Tukey or Dunnet’s multiple-comparison-test using Prism (GraphPad software Inc., San Diego, CA). Survival data were analyzed with log-analysis of survival curves using GraphPad Software. P-values were determined for all analyses and P < 0.05 was considered significant. All experiments reported here represent at least three independent replications. Data are represented as mean values ± standard error of the mean (SEM).

RESULTS

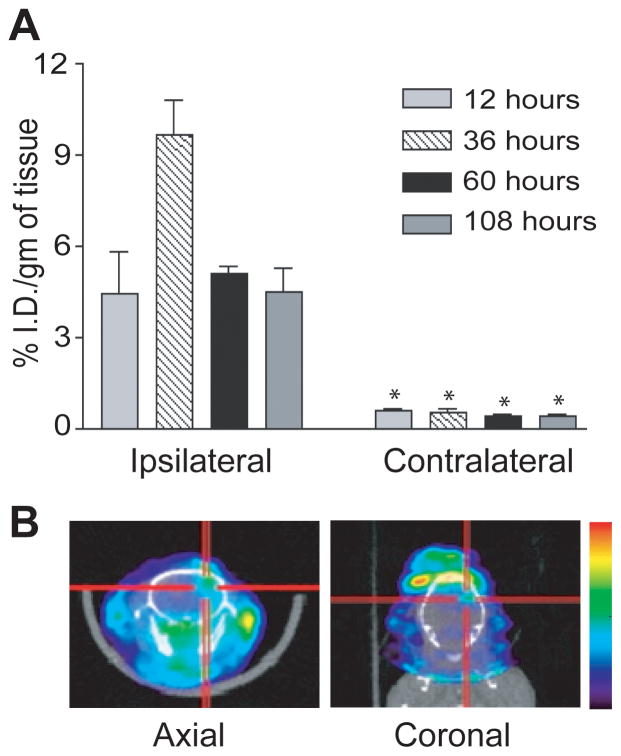

Biodistribution of [125I] anti-HGF L2G7 in mice bearing intracranial tumor xenografts

We showed previously that systemic L2G7 inhibits the growth and/or induces the regression of intracranial PTEN-null/HGF+/c-Met+ tumor xenografts (U87wt). However, the bioavailability of anti-HGF L2G7 to intracranial tumors had not been evaluated. We examined the delivery of radiolabeled L2G7 mAb to the brains of mice bearing pre-established intracranial U87wt glioma xenografts. Mice bearing U87wt xenografts in right caudate/putamen received [125I]L2G7 by a single tail vein injection and delivery to brain was quantified. [125I]L2G7 was preferentially localized to the tumor-bearing brain hemisphere as early as 12 hours and peaked 36 hours post-injection (Figure 1A). The tumor-bearing brain hemisphere showed significantly higher radioactivity (10–20-fold higher) compared to the unaffected contralateral hemisphere at every time point examined (P < 0.01). Animals received [125I]L2G7 as above and, two days later, the anesthetized mice were subjected to X-SPECT immediately followed by CT. Radioactivity localized to the right hemispheric tumor xenografts (Figure 1B). There was no selective accumulation of L2G7 in unimplanted contralateral brain hemispheres or in animals that received a control stereotactic injection of PBS without U87 tumor cells (not shown). These findings show that L2G7 accumulates in HGF-expressing tumor xenografts that contain a permeable tumor vasculature and is comparatively restricted from regions of normal brain by the intact blood-brain barrier.

Figure 1. Delivery of iodinated anti-HGF mAb L2G7 to orthotopic glioma xenografts.

(A) [125I]L2G7 was administered at time zero via tail vein to mice bearing right hemispheric U87wt glioma xenografts. Animals were sacrificed at the indicated post-injection times and the percent-injected dose per gram (% ID/g) within tumor-bearing (ipsilateral) and contralateral brain hemispheres were determined. (B) SPECT-CT performed 48 hours after a single intravenous injection of [125I]L2G7 shows localized increase of radioactivity within the right hemispheric tumor. N=4, * P < 0.01, compared to determination in ipsilateral brain at same time point. Results shown are representative of three replicate experiments.

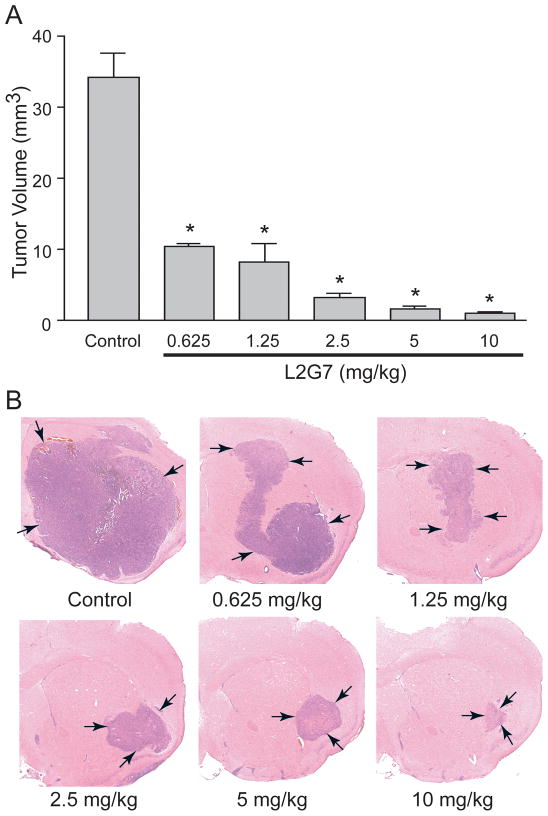

Systemic anti-HGF L2G7 inhibits growth of established intracranial xenografts in a dose dependent manner

We examined the dose response of systemic L2G7 against intracranial U87wt tumor xenografts. Murine L2G7 was administered by i.p. injection at 0.625–10.0 mg/kg twice/week to mice bearing pre-established tumors beginning on post-implantation day 5. All mice were sacrificed on post-implantation day 23 following five L2G7 doses and brains were subjected to histological analysis of tumor size. L2G7 significantly inhibited tumor growth at all doses (P <0.001) compared to animals treated with isotype control 5G8 (Figure 2). Based on these results, 1.25–5.0 mg/kg doses of L2G7 were used for subsequent experiments since these doses inhibited tumor growth by 75–90%.

Figure 2. Systemic anti-HGF mAb inhibits growth of orthotopic PTEN-null/EGFRvIII- glioma xenografts in a dose dependent manner.

Anti-HGF mAb L2G7 (0.625–10.0 mg/kg) or isotype control mAb 5G8 (10 mg/kg) was administered i.p. twice/week for five injections to mice bearing U87wt glioma xenografts. Treatment began 5 days after tumor cell implantation (PID 5). Animals were sacrificed on PID 23 and tumor volumes quantified (A). Hemotoxylin and eosin stained brain sections show representative tumor xenografts (B). N=5, * P < 0.001 compared to control.

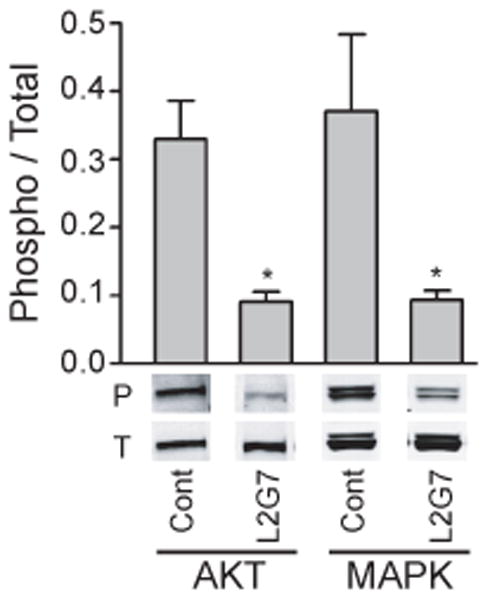

Anti-HGF L2G7 inhibits Akt and MAPK pathway activation in intracranial tumor xenografts

We hypothesized that changes in Akt and/or MAPK activation (i.e. phosphorylation) would serve as biomarkers of HGF neutralization by anti-HGF mAbs. Mice bearing pre-established orthotopic U87wt tumor xenografts that are PTEN-null/HGF+/c-Met+/EGFRvIII− were treated with three doses of either L2G7 or control 5G8 mAb every 2 days. Twenty four hours after the last treatment, total tumor tissue protein was evaluated for phospho-Akt (serine473) and phospho-p44/42 MAPK (threonine202/tyrosine204) relative to total Akt and MAPK, respectively, by dual near infrared immunoblot analysis (Figure 3). Anti-HGF therapy significantly inhibited Akt and MAPK phosphorylation by ~70% (P <0.001) compared to control mAb that had no effect. These results show that Akt and MAPK pathways in orthotopic U87wt xenografts are inhibited by systemic anti-HGF therapy.

Figure 3. Systemic anti-HGF mAb therapy inhibits Akt and MAPK activation in orthotopic PTEN-null/EGFRvIII- xenografts.

Mice bearing pre-established orthotopic U87wt xenografts were treated with anti-HGF L2G7 or control mAb (i.p. 5 mg/kg) every 2–3 days for a total of three injections. Tumors were dissected from brain 24 hours after the last dose and tumor cell lysates subjected to quantitative dual wavelength infrared immunoblot analysis for the phosphorylated (P) and total (T) forms of Akt and MAPK as described in Materials and Methods. Representative bands of triplicate determinations are shown. N=5, * P < 0.05 compared to controls. Results shown are representative of three replicate experiments.

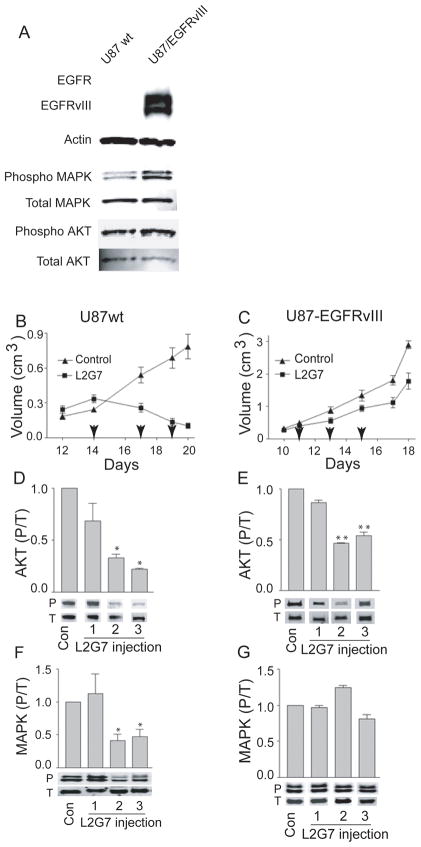

EGFRvIII partially abrogates the effects of anti-HGF therapy on the growth and oncogenic signaling of subcutaneous tumor xenografts

We compared xenografts derived from U87wt cells with xenografts derived from U87wt cells engineered to express the constitutively active EGFR deletion mutant EGFRvIII (U87-EGFRvIIII). Immunoblot analyses show that U87-EGFRvIII cells display hyperactivation of Akt and MAPK in comparison to U87wt cells (1.8-fold and 3-fold, respectively) (Figure 4A). Thus, transgenic EGFRvIII was functional and activated oncogenic pathways shared by both EGFR and c-Met. As expected, both the U87-EGFRvIII and the U87wt cells also express low levels of full length wild-type EGFR (see Supplemental Figure 1).

Figure 4. EGFRvIII expression alters tumor xenograft growth and signaling responses to anti-HGF therapy.

(A) Immunoblot analysis of whole cell protein isolated from U87wt and U87-EGFRvIII cell lines (cultured for 24 h in 0.1% serum conditions) demonstrates increased levels of Akt and MAPK activation (phosphorylation) in cells expressing EGFRvIII. Phosphorylated Akt (or MAPK) relative to total Akt (or MAPK) were quantified by dual infrared immunofluorescence imaging as described in Materials and Methods. (B and C) Growth responses of subcutaneous U87wt and U87-EGFRvIII tumor xenografts (N=5) to control mAb 5G8 or anti-HGF mAb L2G7 (5 mg/kg i.p., every alternate day). Arrows indicate days of each mAb injection. U87wt and U87-EGFRvIII were matched at the time of treatment initiation. (D–G) Tumor lysates were obtained from U87wt (D and F) and U87-EGFRvIII (E and G) xenografts 24 hours following each of the three L2G7 injections and subjected to immunoblot analysis of phospho (P) and total (T) Akt and MAPK. Immunoblots (A, D–G) were quantified using dual wavelength infrared immunofluorescence imaging as described in Materials and Methods. Levels of phospho/total (P/T) Akt and MAPK are relative to control conditions that are normalized to 1.0. Representative bands of triplicate determinations are shown. * P < 0.05, ** P < 0.001 compared to controls. Results are representative of at least three replicate experiments.

We compared the responses of pre-established subcutaneous U87wt and U87-EGFRvIII tumor xenografts to anti-HGF therapy. Tumor xenografts measured ~250 mm3 prior to initiating treatment with either control mAb 5G8 or anti-HGF L2G7 (5mg/kg, i.p. every 2–3 days). Untreated U87-EGFRvIII xenografts grew much more aggressively than untreated U87wt tumors with doubling times of 2.7 days and 3.6 days, respectively (Figures 4B and 4C, note different y-axis scales). Anti-HGF L2G7 therapy generated marked regression of U87wt xenografts at a rate of 50% every 3.5 days (Figure 4B). L2G7 therapy generated only modestly inhibited growth of U87-EGFRvIII xenografts as evidenced by a doubling time of 3.2 days (vs 2.7 days in controls) and tumors that were 40% smaller than controls (P = 0.05) at treatment day 8 (post-implantation day 18) (Figure C).

To test the hypothesis that tumor growth responses would translate to downstream cell signaling responses, the effects of anti-HGF therapy on Akt and MAPkinase activation was also examined in the two models. In U87wt xenografts, L2G7 significantly inhibited AKT phosphorylation ~70–80% (P < 0.05) and MAPK phosphorylation was inhibited ~ 50–60% (P = 0.05) (Figure 4D&F). Akt and MAPK inhibition developed ~72 hours after initiating anti-HGF therapy and coincided with the timing of tumor regression. The magnitude of Akt inhibition by anti-HGF therapy was substantially less in U87-EGFRvIII xenografts (~30%, P < 0.001) than in the U87wt tumors (compare Figures 4D&E). EGFRvIII expression completely abrogated MAPK pathway inhibition by anti-HGF (compare Figures 4F and G). These results suggested that the diminished sensitivity of U87-EGFRvIII xenografts to anti-HGF therapy is due, at least in part, to a shift from HGF:c-Met-dependent MAPkinase activation to HGF:c-Met-independent and presumably EGFRvIII-dependent MAPK pathway signaling.

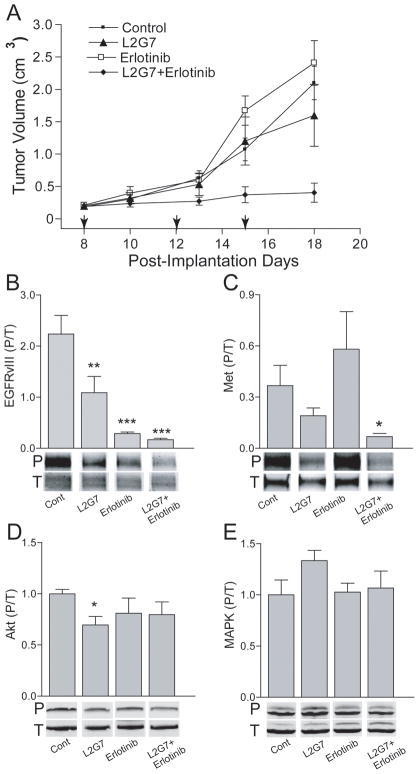

HGF:c-Met and EGFR pathway inhibitors synergistically inhibit PTEN-null/HGF+/c-Met+/EGFRvIII+ xenografts

Our results suggested that simultaneously inhibiting the HGF:c-Met and EGFRvIII pathways would have additive or potentially cooperative anti-tumor effects on EGFRvIII+ glioma xenografts. Therefore, we examined the effects of anti-HGF L2G7 in combination with the EGFRvIII kinase inhibitor erlotinib on U87-EGFRvIII tumor growth and oncogenic cell signaling pathways. Animals bearing subcutaneous U87-EGFRvIII xenografts were treated with either L2G7 or control mAb 5G8 (5mg/kg twice per week, i.p.), erlotinib (150mg/kg 6 days/week by oral gavage), or the combination of anti-HGF + erlotinib. Anti-HGF therapy alone had no significant effect on U87-EGFRvIII tumor xenograft growth (Figure 5A) even though c-Met tyr1234/35 phosphorylation was inhibited by ~50% (Figure 5C). Erlotinib alone had no effect on tumor growth (Figure 5A) despite ~85% inhibition of EGFRvIII tyr845 phosphorylation (Figure 5B). Combining L2G7 and erlotinib markedly inhibited tumor growth and increased tumor doubling time from 2.9 days to 7.7 days seemingly via a synergistic mechanism (Figure 5A). This response was consistent with a concomitant reduction in both c-Met and EGFRvIII phosphorylation (~75% and 90% inhibition, respectively) (Figure 5B and 5C). Surprisingly, the robust inhibition of U87-EGFRvIII xenograft growth in response to L2G7 + erlotinib occurred without reductions in either Akt or MAPK activation (i.e. phosphorylation). (Figure 5D and E).

Figure 5.

HGF and EGFRvIII inhibitors synergize against tumor growth but not against Akt and MAPK activation in PTEN-null/EGFRvIII+ xenografts. Mice bearing subcutaneous U87-EGFRvIII s.c glioma xenografts were treated with either control mAb (5G8) or with anti-HGF L2G7 (5 mg/kg i.p. twice/week) +/− erlotinib (150mg/kg by oral gavage, 6 days/week) or PBS from post-implantation days (PID) 8–15. Arrows (A) indicate days of mAb therapy. Tumor growth responses (N=5) (A) and immunoblot analyses of tumor lysates (N=3) obtained on PID 18 for phospho/total EGFRvIII (B), Met (C), Akt (D), and MAPK (E) are shown. Immunoblots (B–E) were quantified using dual near-infrared immunofluorescence imaging as described in Materials and Methods. Representative bands of triplicate determinations are shown. * = P < 0.05, ** = P < 0.01, *** = P < 0.001 compared to controls. Results are representative of four replicate experiments.

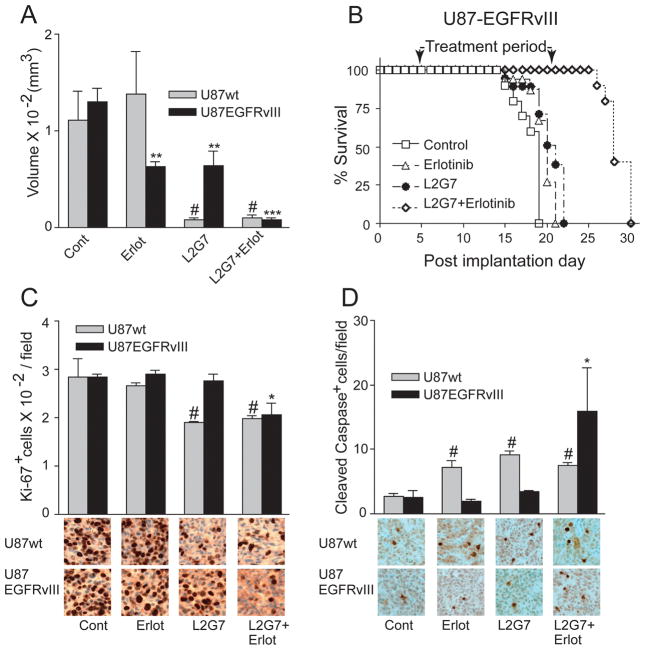

We asked if the responses in subcutaneous glioma xenografts described above would translate to orthotopic intracranial xenografts and to effects on animal survival. Pre-established intracranial U87wt and U87-EGFRvIII xenografts were treated with either control 5G8 or anti-HGF L2G7 mAb (twice per week, i.p.) +/− erlotinib beginning on post-implantation day 5. By post-implantation 5, these xenografts are established and vascularized but substantially smaller than the subcutaneous xenografts used in the previous experiments. Animals bearing U87 and U87-EGFRvIII xenografts were sacrificed on post-implantation days 30 and 16, respectively, and tumor sizes quantified by morphometric histological analysis (Figure 6A). Tumor burdens in untreated control animals were essentially the same on these post-implantation days. Erlotinib alone and L2G7 alone both reduced the size of U87-EGFRvIII tumors by ~50% compared to controls. Erlotinib + L2G7 reduced the size of U87-EGFRvIII tumors ~6-fold compared to each monotherapy and ~15-fold compared to controls. Erlotinib alone had no effect on the growth of U87wt tumors that lack EGFR pathway hyperactivation. Furthermore, L2G7 alone and L2G7 + erlotinib generated similar responses in U87wt xenografts. Thus, erlotinib (either alone or combined with anti-HGF) had no discernable effect in the EGFRvIII− U87wt xenografts.

Figure 6.

HGF and EGFRvIII inhibition cooperatively/synergistically inhibit tumor growth and tumor cell proliferation and increase apoptosis in orthotopic PTEN-null/EGFRvIII+ xenografts. (A) Mice bearing i.c. U87wt or U87-EGFRvIII xenografts were treated with either control (5G8) or anti-HGF (L2G7) mAb +/− erlotinib beginning on PID 5 using doses described in Figure 5. Tumor volumes (N=5) were determined from histological analyses of brains obtained on PID 30 (U87wt) or PID 16 (U87-EGFRvIII). (B) Mice bearing i.c. U87-EGFRvIII xenografts were treated as in (A) from PID 5–21. Anti-HGF + erlotinib therapy substantially improved animal survival in a cooperative and possibly synergistic fashion, (N=10, p<0.01). (C and D) Brains obtained as in (A) were immunohistochemically analyzed for tumor cell proliferation (Ki67) and apoptosis (anti-cleaved caspase 3) indices as described in Materials and Methods. # P < 0.05 compared to U87wt control; N=5, * P < 0.05, ** = P < 0.01, and *** = P < 0.001 compared to U87-EGFRvIII control. Shown are representative images of Ki-67 (C) and anti-cleaved caspase 3 (D) immunohistochemistry.

The cooperative effects of L2G7 and erlotinib translated to a substantial improvement in the survival of animals bearing orthotopic EGFRvIII+ xenografts (Figure 6B). Animals bearing pre-established intracranial U87-EGFRvIII glioma xenografts were treated with either control 5G8 or anti-HGF L2G7 mAb (5mg/kg twice/week) +/− erlotinib (150mg/kg i.p. six days per week) from PID 5–21. Compared to controls, L2G7 alone and erlotinib alone had essentially no effect on median survival. All animals treated with either erlotinib or L2G7 were dead by post-implantation day 21. In contrast, all animals treated with erlotinib + L2G7 survived beyond post-implantation day 21, the last day of therapy, and deaths in this treatment group only occurred after therapy was discontinued. Erlotinib + L2G7 also extended median survival to 28 days with 25% of animals surviving at 30 days, 9 days after stopping all therapy.

The cooperative/synergistic anti-tumor effects of L2G7 + erlotinib in EGFRvIII+ xenografts can be explained, at least in part, by changes in tumor cell proliferation and apoptosis (Figure 6C and D). Neither erlotinib nor L2G7 monotherapies affected tumor Ki-67 labeling (identifies cells within the cell cycle) or labeling with anti-cleaved caspase 3 (apoptosis marker) in U87-EGFRvIII+ xenografts. In contrast, erlotinib + L2G7 reduced Ki67 labeling by ~25% and increased labeling with anti-cleaved caspase-3 ~6-fold (p<0.05). The increase in U87-EGFRvIII apoptosis in response to erlotinib + L2G7 was ~ twice that induced in U87wt tumors by either L2G7 or erlotinib monotherapy or their combination (Figure 6D).

DISCUSSION

Receptor tyrosine kinase inhibitors offer promising new treatments for solid malignancies. We and others have reported that HGF:c-Met pathway inhibitors can have potent anti-tumor effects in HGF+/c-Met+ pre-clinical tumor models (9–12). However, more information on how the genetic background and overlapping signaling networks influence tumor growth is needed to reap the full potential of these new agents. The constitutively active EGFR deletion mutant EGFRvIII is common in glioblastoma and can confer tumor cell resistance to tyrosine kinase inhibitors (26). This prompted us to investigate the influence of EGFRvIII on the tumor response to anti-HGF therapeutics. We compare the anti-tumor effects of a neutralizing anti-HGF mAb on isogenic EGFRvIII− and EGFRvIII+ U87 tumor xenografts that share a PTEN-null/HGF+/c-Met+ background. Our finding that EGFRvIII expression dramatically diminishes anti-tumor responses to HGF/c-Met pathway inhibition was not unexpected because EGFRvIII can activate shared downstream oncogenic signaling pathways independent of c-Met. However, the dramatic supra-additive and synergistic effects of combining EGFR and c-Met pathway inhibitors in EGFRvIII+ tumors that were essentially insensitive to either EGFR or c-Met inhibitors used individually was unexpected. These results are particularly relevant within the context of the relative high frequency of c-Met and EGFR co-expression/hyperactivation in many solid tumors. Recent clinical observations in lung carcinomas showing that c-Met amplification and activation can function as an escape mechanism for erlotinib-responsive cancers (2, 3), further support a treatment strategy combining c-Met and EGFR pathway inhibitors for gliomas that contain EGFRvIII and possibly hyperactivated EGFR.

Current paradigms for targeted therapeutics imply that inhibiting upstream kinases, such as c-Met and EGFR, will be ineffective in the presence of mutations in downstream signaling checkpoints, such as the tumor suppressor PTEN. Clinical observations in patients with genetically heterogeneous brain tumors have led to the conclusion that PTEN loss renders gliomas unresponsive to EGFR inhibitors presumably due to the diminished dependence of Akt activity on PI3K (27). Our finding that PTEN-null U87-EGFRvIII xenografts were insensitive to erlotinib monotherapy is consistent with these clinical observations. However, our results also show that PTEN loss does not necessarily render Akt activity or tumor growth insensitive to upstream receptor tyrosine kinases (i.e. c-Met, EGFRvIII) or their inhibition. These results support the in vitro findings of Stommel et al., who conclude that when considering the targeting of multi-input signaling systems, predictors of clinical efficacy should be based on the total signal flux contributed by multiple pathways and signaling checkpoints (4). Furthermore, the unexpected synergism between anti-HGF mAb and erlotinib against the EGFRvIII+ glioma xenografts demonstrate that tumor subsets can have complex nonlinear co-dependencies on multiple receptor tyrosine kinases and presumably other molecular regulators of tumor growth and malignant progression (28). A possible example of this is described by Bonine-Summers et al. who demonstrated that EGFR inhibition can block HGF activation of c-Met, an effect not attributable to a direct inhibition of Met by EGFR inhibitors (29).

Understanding each tumor’s signaling network and the molecular consequences of targeted inhibition should make it possible to combine targeted molecular therapeutics rationally. We initially predicted that two prominent downstream constituents of receptor tyrosine kinase pathways, Akt and MAPK, would serve as biochemical markers of c-Met and EGFRvIII pathway inhibition and tumor growth response. We observed EGFRvIII− glioma regression concurrent with a substantial decline in both phospho-Akt and phospho-MAPK in response to anti-HGF monotherapy. In contrast, anti-HGF failed to induce tumor regression or diminish phospho-MAPK in EGFRvIII+ xenografts. Surprisingly, adding erlotinib to anti-HGF therapy failed to reduce Akt and MAPK activation in EGFRvIII+ xenografts below levels seen in response to anti-HGF alone. These in vivo findings differ from the in vitro findings of Stommel et al. using cultured cell lines (4). Potential explanations include differences in the kinetics and magnitudes of c-Met and EGFRvIII inhibition achieved in vitro vs in vivo. For example, our tissue sampling times might not have been optimal for detecting dynamic and transient pathway inhibition in the EGFRvIII+ xenografts. Alternatively, there may be in vivo-specific mechanisms of signaling network regulation such as stromal effects or compensatory secondary signaling responses that are not present in vitro. A careful histological review of the xenografts revealed no differences in xenograft infiltration by non-neoplastic stromal components between the control EGFRvIII+ xenografts and those treated with erlotinib + L2G7. An alternative possibility is that phospho-Akt and phospho-MAPK might not adequately reflect the flux through all relevant oncogenic signals driven by the combination of EGFRvIII and c-Met signaling thereby implicating other critical downstream mediators. Recent reports have identified over 69 proteins within the signaling networks shared by the EGFR and Met pathways (28, 30). Considerable work is needed to identify their interactive roles and clinical utility. Our finding that erlotinib had minimal or no effects on Akt and MAPK phosphorylation even under conditions that reduced EGFRvIII tyr845 phosphorylation by >80% may seem contradictory. However, this can be explained by the fact that the levels of phospho-EGFRvIII in erlotinib-treated tumors remained detectable and presumably above a critical threshold for Akt and MAPK activation (28). It is interesting that anti-HGF monotherapy reduced EGFRvIII tyr845 phosphorylation by ~50% suggesting receptor crosstalk either by direct receptor interactions or via indirect mechanisms such as src-dependent EGFR phosphorylation as observed by Tice et al. in wild-type EGFR (29, 31).

The marginal clinical efficacy observed to date for receptor tyrosine kinase inhibitor monotherapy in malignant brain tumors that commonly co-express activated c-Met and EGFRvIII, is partially explained by our current findings within the context of previous results (4). We now provide in vivo evidence that inhibiting the contributions of multiple RTKs can be profoundly more beneficial than monotherapy directed at a single RTK. This evidence further supports the application of a “personalized medicine” paradigm, combining EGFR and c-Met pathway inhibitors in patients with gliomas containing the appropriate molecular profiles (4, 32, 33). It will be important to determine if our results can be extended to other receptor tyrosine kinases that are amplified or mutated, and applied to improving clinical outcomes. The recent entry of novel c-Met pathway inhibitors into Phase I/II clinical trials, and the availability of FDA-approved EGFR inhibitors establish a therapeutic armamentarium to test these findings in the clinical setting (34–38).

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by NIH grants NS32148 (JL), CA129192 (JL), CA92871 (MGP) the United Negro College Fund/Merck Science Initiative and the American Federation for Aging Research-MSTAR Program (CRG).

We thank Charles Eberhart, M.D., Ph.D. (Department of Pathology, Johns Hopkins School of Medicine) for his assistance in assessing tumor xenograft histology.

References

- 1.Comprehensive genomic characterization defines human glioblastoma genes and core pathways. Nature. 2008;455(7216):1061–8. doi: 10.1038/nature07385. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Engelman JA, Zejnullahu K, Mitsudomi T, et al. MET amplification leads to gefitinib resistance in lung cancer by activating ERBB3 signaling. Science. 2007;316(5827):1039–43. doi: 10.1126/science.1141478. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bean J, Brennan C, Shih JY, et al. MET amplification occurs with or without T790M mutations in EGFR mutant lung tumors with acquired resistance to gefitinib or erlotinib. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2007;104(52):20932–7. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0710370104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Stommel JM, Kimmelman AC, Ying H, et al. Coactivation of receptor tyrosine kinases affects the response of tumor cells to targeted therapies. Science. 2007;318(5848):287–90. doi: 10.1126/science.1142946. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Birchmeier C, Birchmeier W, Gherardi E, Vande Woude GF. Met, metastasis, motility and more. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2003;4(12):915–25. doi: 10.1038/nrm1261. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Laterra J, Nam M, Rosen E, et al. Scatter factor/hepatocyte growth factor gene transfer enhances glioma growth and angiogenesis in vivo. Lab Invest. 1997;76(4):565–77. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lamszus K, Schmidt NO, Jin L, et al. Scatter factor promotes motility of human glioma and neuromicrovascular endothelial cells. Int J Cancer. 1998;75(1):19–28. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-0215(19980105)75:1<19::aid-ijc4>3.0.co;2-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bardelli A, Longati P, Albero D, et al. HGF receptor associates with the anti-apoptotic protein BAG-1 and prevents cell death. Embo J. 1996;15(22):6205–12. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kim KJ, Wang L, Su YC, et al. Systemic anti-hepatocyte growth factor monoclonal antibody therapy induces the regression of intracranial glioma xenografts. Clin Cancer Res. 2006;12(4):1292–8. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-05-1793. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Burgess T, Coxon A, Meyer S, et al. Fully human monoclonal antibodies to hepatocyte growth factor with therapeutic potential against hepatocyte growth factor/c-Met-dependent human tumors. Cancer Res. 2006;66(3):1721–9. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-05-3329. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Martens T, Schmidt NO, Eckerich C, et al. A novel one-armed anti-c-Met antibody inhibits glioblastoma growth in vivo. Clin Cancer Res. 2006;12(20 Pt 1):6144–52. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-05-1418. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Christensen JG, Schreck R, Burrows J, et al. A selective small molecule inhibitor of c-Met kinase inhibits c-Met-dependent phenotypes in vitro and exhibits cytoreductive antitumor activity in vivo. Cancer Res. 2003;63(21):7345–55. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Berthou S, Aebersold DM, Schmidt LS, et al. The Met kinase inhibitor SU11274 exhibits a selective inhibition pattern toward different receptor mutated variants. Oncogene. 2004;23(31):5387–93. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1207691. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ma PC, Schaefer E, Christensen JG, Salgia R. A selective small molecule c-MET Inhibitor, PHA665752, cooperates with rapamycin. Clin Cancer Res. 2005;11(6):2312–9. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-04-1708. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Nishikawa R, Ji XD, Harmon RC, et al. A mutant epidermal growth factor receptor common in human glioma confers enhanced tumorigenicity. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1994;91(16):7727–31. doi: 10.1073/pnas.91.16.7727. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lal A, Glazer CA, Martinson HM, et al. Mutant epidermal growth factor receptor up-regulates molecular effectors of tumor invasion. Cancer Res. 2002;62(12):3335–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lal B, Xia S, Abounader R, Laterra J. Targeting the c-Met pathway potentiates glioblastoma responses to gamma-radiation. Clin Cancer Res. 2005;11(12):4479–86. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-05-0166. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Tomayko MM, Reynolds CP. Determination of subcutaneous tumor size in athymic (nude) mice. Cancer Chemother Pharmacol. 1989;24(3):148–54. doi: 10.1007/BF00300234. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Mehrara E, Forssell-Aronsson E, Ahlman H, Bernhardt P. Specific growth rate versus doubling time for quantitative characterization of tumor growth rate. Cancer Res. 2007;67(8):3970–5. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-06-3822. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Abounader R, Lal B, Luddy C, et al. In vivo targeting of SF/HGF and c-met expression via U1snRNA/ribozymes inhibits glioma growth and angiogenesis and promotes apoptosis. Faseb J. 2002;16(1):108–10. doi: 10.1096/fj.01-0421fje. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Tzourio N, Joliot M, Mazoyer BM, Charlot V, Sutton D, Salamon G. Cortical region of interest definition on SPECT brain images using X-ray CT registration. Neuroradiology. 1992;34(6):510–6. doi: 10.1007/BF00598963. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Sarkaria JN, Carlson BL, Schroeder MA, et al. Use of an orthotopic xenograft model for assessing the effect of epidermal growth factor receptor amplification on glioblastoma radiation response. Clin Cancer Res. 2006;12(7 Pt 1):2264–71. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-05-2510. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Reznik TE, Sang Y, Ma Y, et al. Transcription-dependent epidermal growth factor receptor activation by hepatocyte growth factor. Mol Cancer Res. 2008;6(1):139–50. doi: 10.1158/1541-7786.MCR-07-0236. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Towbin H, Staehelin T, Gordon J. Electrophoretic transfer of proteins from polyacrylamide gels to nitrocellulose sheets: procedure and some applications. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1979;76(9):4350–4. doi: 10.1073/pnas.76.9.4350. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kearns EA, Simonson LG, Schutt RW, Johnson MJ, Neil LC. Characterization of monoclonal antibodies to two Treponema denticola serotypes by the indirect fluorescent-antibody assay. Microbios. 1991;65(264–265):147–53. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Learn CA, Hartzell TL, Wikstrand CJ, et al. Resistance to tyrosine kinase inhibition by mutant epidermal growth factor receptor variant III contributes to the neoplastic phenotype of glioblastoma multiforme. Clin Cancer Res. 2004;10(9):3216–24. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.ccr-03-0521. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Mellinghoff IK, Wang MY, Vivanco I, et al. Molecular determinants of the response of glioblastomas to EGFR kinase inhibitors. N Engl J Med. 2005;353(19):2012–24. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa051918. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Guo A, Villen J, Kornhauser J, et al. Signaling networks assembled by oncogenic EGFR and c-Met. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2008;105(2):692–7. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0707270105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Bonine-Summers AR, Aakre ME, Brown KA, et al. Epidermal growth factor receptor plays a significant role in hepatocyte growth factor mediated biological responses in mammary epithelial cells. Cancer Biol Ther. 2007;6(4):561–70. doi: 10.4161/cbt.6.4.3851. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Huang PH, Mukasa A, Bonavia R, et al. Quantitative analysis of EGFRvIII cellular signaling networks reveals a combinatorial therapeutic strategy for glioblastoma. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2007;104(31):12867–72. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0705158104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Tice DA, Biscardi JS, Nickles AL, Parsons SJ. Mechanism of biological synergy between cellular Src and epidermal growth factor receptor. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1999;96(4):1415–20. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.4.1415. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Varmus H. The new era in cancer research. Science. 2006;312(5777):1162–5. doi: 10.1126/science.1126758. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Haas-Kogan DA, Prados MD, Lamborn KR, Tihan T, Berger MS, Stokoe D. Biomarkers to predict response to epidermal growth factor receptor inhibitors. Cell Cycle. 2005;4(10):1369–72. doi: 10.4161/cc.4.10.2105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Shapiro GIHE, Malburg L, DeZube B, Miles D, Keer H, Zhu AX, Laeder T, LoRusso P. A phase I dose-escalation study of the safety, pharmacokinetics (PK), and pharmacodynamics of XL880, a VEGFR and MET kinase inhibitor, administrated daily to patients with advanced malignancies. The 2007 AACR-NCI-EORTC International Conference on Molecular Targets and Cancer Therapeutics; 2007; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Http://www.exelixis.com/pipeline_xl184.shtml. [cited; Available from: Http://www.exelixis.com/pipeline_xl184.shtml

- 36.ArQule I. A summary of the clinical findings of selective c-MET inhibitor ARQ197, providing clinical “proof of concept” for the use of a selective c-MET inhibitor. 2008 [cited; Available from: Http://phx.corporate-ir.net/phoenix.zhtml?c=82991&p=irol-presentations.

- 37.Garcia ARL, Cunningham CC, Nemunaitis J, Li C, Rulewski N, Dovholuk A, Savage R, Chan T, Bukowski R, Mekhail T. Phase I study of ARQ 197, a selective inhibitor of the c-Met RTK in patients with metastatic solid tumors reaches recommended phase 2 dose. Journal of Clinical Oncology. 2007;25:144s. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Gordon MSMD, Sweeney C, Erbeck N, Patel R, Kakkar T, Yan L, Eckhardt SG, Gore L. Interim results from a first-in-human study with AMG102, a full human monoclonal antibody that neutralizes hepatocyte growth factor (HGF), the ligand to c-Met receptor, in patients (pts) with advanced solid tumors. Journal of Clinical Oncology. 2007;25:150s. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.