Abstract

Background

Health-related quality of life (HRQOL) is difficult to efficiently measure in the clinic setting. Our aim was to develop and test a simple tool to measure the burden of Crohn's disease (CD) and its treatment and to compare how patients and their physicians perceive the impact of CD on HRQOL.

Methods

A cross-sectional, self-administered questionnaire was distributed to patients with CD. The questionnaire included a feeling thermometer to measure disease and treatment burden, which was compared to the Short Inflammatory Bowel Disease Questionnaire (SIBDQ). At that visit, the patient's physician completed a questionnaire containing the feeling thermometer and the Harvey Bradshaw index (HBI). Nonparametric tests were use to report results.

Results

In all, 113 surveys were completed. The median age of respondents was 40 years and 68% were female. Using the feeling thermometer (scale 0–100), patients reported their current health as a median of 70 (interquartile range [IQR] 50–80) and their disease specific burden as 20 (IQR 10–40). Treatment-specific burden was 6.9 (IQR 1.3–20). Physicians perceived their patients’ current health as a median of 71.3 (IQR 57.5–90) with a disease burden of 12.5 (IQR 5–30). Spearman's rho between the burden of symptoms measured by the feeling thermometer and the SIBDQ was –0.71. The correlation between patient and physician perception of current health was 0.73.

Conclusions

Two questions using the feeling thermometer provide a quick and accurate assessment of the burden of CD on patients. Physicians’ perception of the burden of disease was similar to their patients.

Keywords: Crohn's disease, inflammatory bowel disease, health related quality of life

Crohn's disease (CD) is a chronic illness that significantly impacts health-related quality of life (HRQOL).1–3 In the short period of time of an office visit, HRQOL may not be readily evident to physicians since it encompasses a complex interplay of emotional, social, and physical factors.4 To better deliver patient-centered care, it would be helpful to have a tool to efficiently measure the impact of a patient's disease on daily life.5,6

A number of inflammatory bowel disease (IBD)-specific HRQOL surveys have been developed.7–11 While informative and used commonly in clinical trials, these surveys have not become a routine part of daily clinical practice. In addition, while most of these instruments have focused domains that clearly define the components affecting quality of life, none specifically measure the disease or treatment burden (e.g., medications, frequent testing, office visits, colonoscopy, etc.). Since overall disease burden may differ from disease activity or symptoms, it may be a better compass to direct patient care and thus is important to measure.12 A tool that is simple to use, quickly performed, and easily translatable to physicians may increase the regular use of quality of life measures in longitudinal patient care.

The feeling thermometer is a simple visual analog scale that looks like a thermometer and has been developed and validated for other disease processes including gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD) to directly measure the burden of symptoms and treatment on quality of life.13 The thermometer can be completed in very little time and is easily interpreted. In this study, we aimed to 1) develop and test the feeling thermometer to measure the burden of CD and its treatment on our patients’ lives and 2) study if physicians accurately perceive the impact of CD on their patients.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Design and Survey Development

This study was a cross-sectional, self-administered written questionnaire. The questionnaire was developed, revised, and tested for understanding using cognitive interviews in 10 patients with CD at the Dartmouth-Hitchcock Medical Center. The final 29-item questionnaire was composed of closed response answers including the feeling thermometer to measure disease and treatment burden, and the Short Form Inflammatory Bowel Disease Questionnaire (SIBDQ) for comparison to the feeling thermometer responses. The feeling thermometer is a visual analog scale that looks like a thermometer with a graduation from 0 (death) to 100 (perfect health) that can be used to determine health status. In this study, the feeling thermometer was used to assess the burden of symptoms and treatment of CD.13 The SIBDQ is a 10-item HRQOL questionnaire validated for use in CD patients. It assesses 4 domains: physical, social, emotional, and systemic and is scored on a 7-point Likert scale from 1 (severe problem) to 7 (no problems at all). The absolute score ranges from 10 (poor HRQOL) to 70 (optimum HRQOL).7

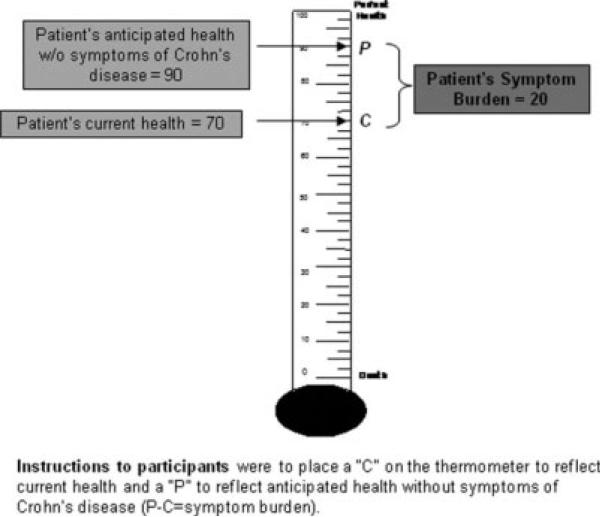

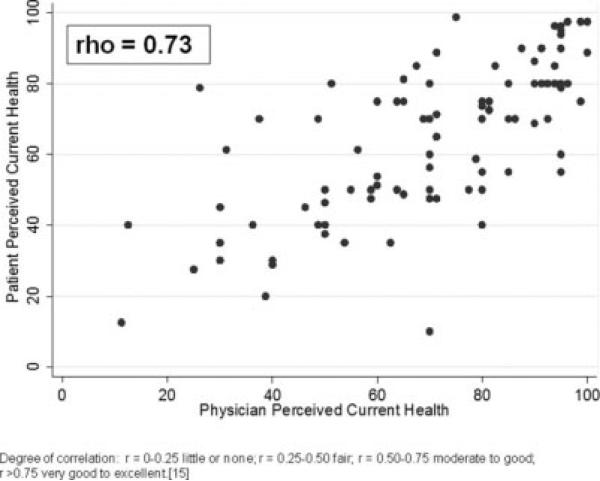

To assess symptom burden, patients were asked to place a “C” on the feeling thermometer to represent current health and a “P” to represent their anticipated health without symptoms of CD. The difference between C and P represented the symptom burden. A sample response is shown in Figure 1. To assess treatment burden, patients were asked to place a “C” on a second thermometer to represent current health and a “P” to represent how they would feel if they could stop all of the things related to their treatment for CD (e.g., medicines, lab tests, doctor visits, colonoscopy, diet, lifestyle changes) and maintain their current health. The difference between C and P represented the treatment burden. The feeling thermometers and associated questions used in this study are shown in the Appendix.

FIGURE 1.

Sample patient response for the feeling thermometer used to measure disease burden.

A separate physician questionnaire was developed that contained a feeling thermometer to assess perceived patient symptom burden in addition to the Harvey–Bradshaw index (HBI). The HBI is a 5-item index used to assess disease activity. Lower scores indicate less disease activity with a score ≤4 indicating remission.14

Participants

Adult patients (18 years old or older) with CD and their physicians at the Dartmouth-Hitchcock IBD clinic were asked to participate in the study. The majority of physician surveys were completed by gastroenterologists; however, a small number were completed by a nurse practitioner who specializes in IBD patient care. The diagnosis of CD was determined by the patient's physician.

Survey Administration

The questionnaire was distributed to consecutive patients presenting for a clinic appointment. At the time of that visit, the patient's physician was asked to complete the physician questionnaire with a matching study patient number to allow for comparison. All surveys were anonymous and physicians did not have access to the results of their patient's questionnaire. The study was performed only after institutional internal review board approval. A licensing agreement from McMaster University was obtained for use of the SIBDQ.

Statistical Analysis

Simple descriptive statistics were used to report results. Since the results were not normally distributed, medians with interquartile range (IQR) are reported and the Wilcoxon signed-rank test used to compare differences. Spearman's rank correlation coefficients (Spearman's rho) were calculated to compare responses from the thermometer questions to the SIBDQ or HBI and to compare responses between patients and their physicians. The strength of correlation was described as according to Colton.15

RESULTS

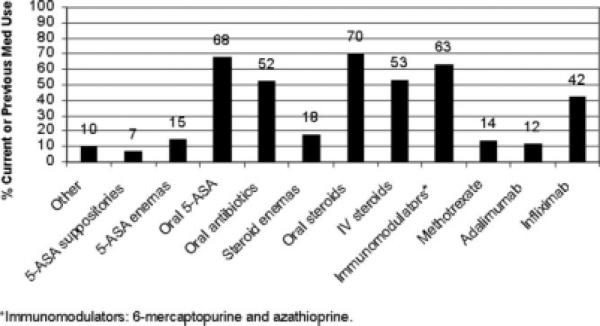

One hundred thirteen surveys were completed. The median age of patients was 40 years (IQR 30–54) and 68% were female. Further details of their demographic and clinical characteristics are shown in Table 1. Patients were on a broad range of treatments as shown in Figure 2.

TABLE 1.

Patient Characteristics (n = 113)

| Characteristic | n (%) | n (%) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age median (IQR) | 40 (30–54) | Extent of disease | |

| Gender (female) | 68 (63.6) | Small bowel | 33 (33.3) |

| Education level | Colonic | 16 (16.2) | |

| Some high school | 3 (2.8) | lleocolonic | 50 (50.5) |

| High school diploma | 52 (49.1) | Flares per year | |

| College degree | 39 (36.8) | 0 | 14 (13.9) |

| Graduate degree | 12 (11.3) | 1–2 | 27 (26.7) |

| SIBDQ* median (IQR) | 47.5 (37–57) | 3–5 | 32 (31.7) |

| HBI^ median (IQR) | 1 (0–5) | >5 | 28 (27.7) |

| Crohn's duration | Previous hospitalization | ||

| <2 years | 12 (11.2) | No | 29 (27.1) |

| 2–5 years | 27 (25.2) | Yes | 78 (72.9) |

| 6–10 years | 20 (18.7) | Previous surgery | |

| >10 years | 48 (44.86) | No | 50 (47.2) |

| Yes | 56 (52.8) |

FIGURE 2.

Current and previous medication use among study participants.

Burden of Symptoms and Treatment

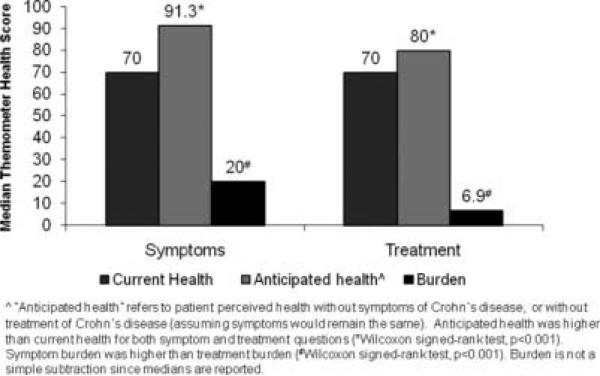

On the feeling thermometer used to measure symptom burden, the median of patients’ reported current health was 70 (IQR 50–80) with projected improvement to 91.3 (IQR 82.5–96.3) without symptoms of CD (P < 0.001). The median burden of CD-related symptoms was 20 (IQR 10–40). On the feeling thermometer used to measure treatment burden, the median of patients’ reported current health was 70 (IQR 50–80) with projected improvement to 80 (IQR 70–90.6) with maintenance of their current health but without all of the things related to their treatment (P < 0.001). This resulted in a median burden of treatment of 6.9 (IQR 1.3–20). Symptom burden was significantly higher than treatment burden (P < 0.001). These results are displayed in Figure 3.

FIGURE 3.

Patients’ perceived current health, anticipated health, and burden of symptoms and treatment as measured with the feeling thermometer.

The feeling thermometer demonstrated internal validity (repeatability) with patients showing an excellent correlation (rho = 0.99) between the 2 current health status questions. We excluded 1 response from the burden of symptoms thermometer question and 20 responses from the burden of treatment thermometer question where results did not follow logic (e.g., when “perfect health” was recorded as lower than “current health”). One response was excluded from the physician questionnaire for the same reason.

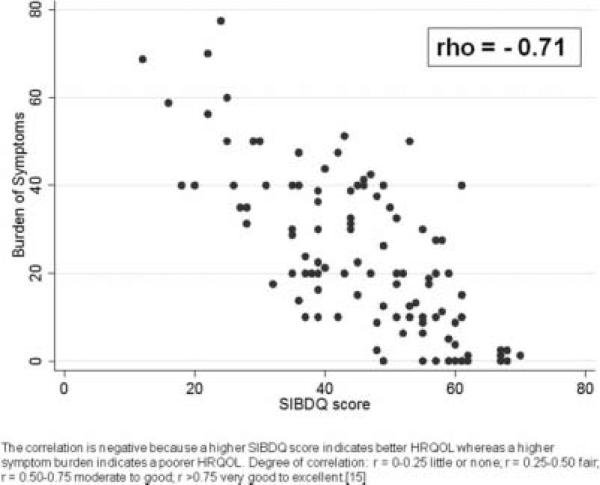

Performance of the Feeling Thermometer Compared to the SIBDQ and HBI

Spearman's correlation coefficients were performed to compare the feeling thermometer, SIBDQ, HBI, and physician responses. The current health of patients and the SIBDQ had a moderate to good degree of correlation (rho = 0.71). The correlation between the symptom burden measured by the feeling thermometer and the SIBDQ was also moderate to good (rho = –0.71) as shown in Figure 4. The correlation is negative because a higher SIBDQ score and lower symptom burden reflect greater quality of life. Treatment burden correlated with SIBDQ score to a fair degree (rho = –0.3). Physician perception of patient current health versus the HBI had a moderate to good degree of correlation (rho = –0.68) as did physician perceived symptom burden versus the HBI (rho = 0.67).

FIGURE 4.

Correlation between patients’ burden of symptoms and their SIBDQ score.

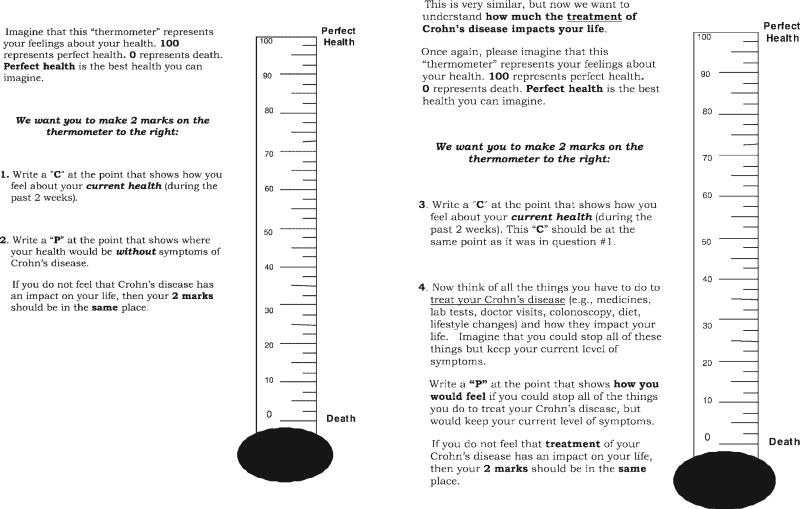

Physician Versus Patient Perception of Disease Burden

The median of physicians’ perception of their patients’ current health was 71.3 (IQR 57.5–90) with projected improvement to 93.8 (IQR 86.3–97.5) without symptoms resulting in a median disease burden of 12.5 (IQR 5–30). The correlation between patient and physician perception of current health using the feeling thermometer was moderate to good (rho = 0.73) as shown in Figure 5. There was a lower degree or correlation (but still moderate to good) between patient and physician perceived symptom burden (r = 0.69).

FIGURE 5.

Correlation between patients’ and their physicians’ perception of current health using the feeling thermometer.

DISCUSSION

We developed and tested a feeling thermometer to measure the burden of CD symptoms and treatment. We have shown that just 2 questions using the feeling thermometer provides a comparable assessment of HRQOL to the SIBDQ. This is supported by the excellent internal validity and the moderate to good degree correlation between the burden of symptoms measured using the feeling thermometer and the SIBDQ. Using the feeling thermometer, physicians had a moderate to good correlation with their patients’ perception of disease burden.

There was a lower degree of correlation with the HBI, which may appear to be a limitation, but this is not unexpected since the HBI is a marker of disease activity, not HRQOL. Similarly, there was only a fair correlation between treatment burden and SIBDQ, as anticipated since the SIBDQ does not specifically measure quality of life pertaining to treatment. One limitation of the generalizability of this study is that the population tested was fairly homogeneous and at a single center, which may not be representative of all IBD patients. In addition, the feeling thermometer and survey questions may require a certain degree of literacy and numeracy for accurate performance. However, the feeling thermometer has been externally validated in a broad population of patients with GERD.13 Furthermore, before surveys were distributed for our study, the thermometer questions were revised using cognitive interviews with patients and tested for comprehension. During the study, although patients answered the feeling thermometer question for symptom burden appropriately in all but 1 instance, the treatment burden responses were against logic in 20 patients. Therefore, we feel more confident in patients’ ability to accurately use this tool to measure symptom burden than the treatment burden. The internal validity was remarkably high, which could suggest a degree of questionnaire redundancy; however, we feel it shows understanding of the tool to further confirm its validity. A strength of the feeling thermometer is its brevity, but this simple 2-question tool does not have the ability to capture how different domains of health influence quality of life, as can be done with more extensive HRQOL instruments.

In addition to the 10-item SIBDQ, the Short Health Scale (SHS) is another abbreviated HRQOL instrument.8 The SHS was developed by Stjernman et al8 and is a 4-item self-administered questionnaire composed of 4 subjective health domains: symptoms, functional status, worry, and general well-being graded on visual analog scales creating a profile with 4 distinct scores for each patient. The SHS is validated for use in CD and promoted for clinic use. The SHS is less time-consuming than many other HRQOL surveys, but it is still longer than the feeling thermometer and does not measure the overall burden of disease and treatment like the feeling thermometer does. The SHS does have the advantage of defining particular domains that influence HRQOL.

The finding that patients have a higher burden of disease than treatment suggests that patients are willing to accept more treatment (and treatment-associated risks) to improve their overall health. A study by Johnson et al16 came to similar conclusions. They found that as CD patients had more severe disease, they were willing to accept higher risks of serious adverse events including lymphoma, progressive multifocal leukoencephalopathy, and life-threatening infections. Perhaps the feeling thermometer can be used to help patients establish their personal treatment thresholds based on their current disease burden and treatment goals.

Using the feeling thermometer, we found that physicians fairly accurately perceive their patient's health status. In the study that developed the Crohn's Disease Activity Index (CDAI), the physician's overall rating of patient health was compared to the CDAI score. Inconsistencies were observed between physician determination of health and the CDAI. The authors reported that this could reflect the “softness in the physician's ability to make these judgments.”17 This supports the use of a tool to assist physicians in assessing HRQOL. In addition, when surveyed, patients generally feel that physicians do not adequately understand their experiences and want a more interactive approach to care.18,19 Incorporating the feeling thermometer into daily clinical practice may help patients feel better about their care and help physicians better gauge overall HRQOL.

In conclusion, we have shown that the feeling thermometer is a practical tool to use in clinical practice to quickly assess the overall burden of symptoms and treatment in patients with CD. With this tool physicians (by either reviewing patient responses or completing the instrument themselves) can fairly accurately measure the impact of CD on the lives of their patients. Future research should be performed to study the feeling thermometer for use in ulcerative colitis and the pediatric population, and to assess the tool's responsiveness in different disease activity states.

Acknowledgments

Dr. Siegel is supported by a Crohn's and Colitis Foundation Career Development Award and Grant Number K23DK078678 from the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases or the National Institutes of Health.

APPENDIX

REFERENCES

- 1.Cohen RD. The quality of life in patients with Crohn's disease. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2002;16(9):1603–1609. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2036.2002.01323.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Drossman DA. Measuring quality of life in inflammatory bowel disease. Pharmacoeconomics. 1994;6(6):578–580. doi: 10.2165/00019053-199406060-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Pizzi LT, Weston CM, Goldfarb NI, et al. Impact of chronic conditions on quality of life in patients with inflammatory bowel disease. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2006;12(1):47–52. doi: 10.1097/01.mib.0000191670.04605.e7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Irvine EJ. A quality of life index for inflammatory bowel disease. Can J Gastroenterol. 1993;7:155–159. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Irvine EJ. Quality of life—measurement in inflammatory bowel disease. Scand J Gastroenterol Suppl. 1993;199:36–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Guyatt GH, Feeny DH, Patrick DL. Measuring health-related quality of life. Ann Intern Med. 1993;118(8):622–629. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-118-8-199304150-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Irvine EJ, Zhou Q, Thompson AK. The Short Inflammatory Bowel Disease Questionnaire: a quality of life instrument for community physicians managing inflammatory bowel disease. CCRPT Investigators. Canadian Crohn's Relapse Prevention Trial. Am J Gastroenterol. 1996;91(8):1571–1578. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Stjernman H, Granno C, Jarnerot G, et al. Short health scale: a valid, reliable, and responsive instrument for subjective health assessment in Crohn's disease. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2008;141:47–52. doi: 10.1002/ibd.20255. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Drossman DA, Leserman J, Li ZM, et al. The rating form of IBD patient concerns: a new measure of health status. Psychosom Med. 1991;53(6):701–712. doi: 10.1097/00006842-199111000-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Guyatt G, Mitchell A, Irvine EJ, et al. A new measure of health status for clinical trials in inflammatory bowel disease. Gastroenterology. 1989;96(3):804–810. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Pallis AG, Mouzas IA. Instruments for quality of life assessment in patients with inflammatory bowel disease. Dig Liver Dis. 2000;32(8):682–8. doi: 10.1016/s1590-8658(00)80330-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kane SV, Loftus EV, Jr., Dubinsky MC, et al. Disease perceptions among people with Crohn's disease. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2008;14(8):1097–1101. doi: 10.1002/ibd.20418. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Liu JY, Woloshin S, Laycock WS, et al. Symptoms and treatment burden of gastroesophageal reflux disease: validating the GERD assessment scales. Arch Intern Med. 2004;164(18):2058–2064. doi: 10.1001/archinte.164.18.2058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Harvey RF, Bradshaw JM. A simple index of Crohn's-disease activity. Lancet. 1980;1(8167):514. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(80)92767-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Colton T. Statistics in medicine. 1st ed. Little, Brown; Boston: 1974. p. xii.p. 372. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Johnson FR, Ozdemir S, Mansfield C, et al. Crohn's disease patients’ risk-benefit preferences: serious adverse event risks versus treatment efficacy. Gastroenterology. 2007;133(3):769–779. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2007.04.075. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Best WR, Becktel JM, Singleton JW, et al. Development of a Crohn's Disease Activity Index. National Cooperative Crohn's Disease Study. Gastroenterology. 1976;70(3):439–444. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Westwood N, Travis SP. Review article: what do patients with inflammatory bowel disease want for their clinical management? Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2008;27(Suppl 1):1–8. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2036.2008.03605.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wolfe BJ, Sirois FM. Beyond standard quality of life measures: the subjective experiences of living with inflammatory bowel disease. Qual Life Res. 2008;17(6):877–886. doi: 10.1007/s11136-008-9362-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]