Abstract

Background/Aim

We hypothesized that limited information is given to patients on the risks and benefits of individual therapy, and feedback is lacking to verify if patients correctly interpreted the given information. We assessed the perspectives of patients with inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) concerning the treatment-associated risks/benefits of infliximab.

Methods

Patients were asked to complete a survey regarding the benefits and risks of infliximab. Results are reported as descriptive statistics. Comparisons between groups were analyzed using independent t tests and the Kruskal-Wallis test.

Results

In total, 152 IBD patients completed the questionnaire. Fifty-seven percent (78/138) estimated the 1-year remission rate from infliximab to be >50%. Seventy-one percent (104/146) indicated they would not take a drug with risks reflecting those estimated for infliximab if the 1-year remission rate was <75%. Crohn’s disease patients and those recalling a discussion regarding the risks/benefits of infliximab treatment had higher estimates of the 1-year remission rate with infliximab than ulcerative colitis patients (p = 0.03) and patients who did not recall previous information (p = 0.03). Perceptions were independent of age and disease duration.

Conclusion

IBD patients misperceive the risks and benefits of infliximab. The majority of patients would not accept treatment-related risks if the 1-year remission rate was <75%. Counseling on treatment-associated risks and benefits should be ameliorated.

Keywords: Inflammatory bowel disease, Patients’ perspectives, Infliximab

Introduction

Inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) is the heading for two major chronic gastrointestinal diseases of unknown origin: ulcerative colitis (UC) and Crohn’s disease (CD). Several therapeutic strategies have been advocated in the treatment of IBD, each with its own risks and benefits. However, conventional treatments have not been able to change the natural course of the disease [1]. Increasing use of immunosuppressants in CD did not significantly decrease the number of intestinal complications of CD or the need for surgery [2]. It is unknown whether earlier implementation of immunosuppressants in the disease course (referred to as early aggressive treatment) will prevent this disabling disease course.

Infliximab is a chimeric monoclonal IgG1 antibody directed against tumor necrosis factor alpha, which is conventionally (i.e. step-up therapy) reserved for patients who have failed both corticosteroids and immunomodulators. Large randomized trials have confirmed the efficacy of infliximab in the treatment of both CD and UC [3–5]. A recent open randomised trial investigated the benefit of early combined immunosuppression compared to conventional management in patients with newly diagnosed CD [6]. Combined immunosuppression consisted of infliximab and azathioprine, and conventional treatment consisted of corticosteroids, followed, in sequence, by azathioprine and infliximab. In patients that were recently diagnosed with CD, combined immunosuppression early in the disease course was more effective than conventional therapy for the induction of remission and reduction of corticosteroid use [6].

Serious side effects of infliximab are rare, but can include serum sickness-like reaction, sepsis and opportunistic infection, and autoimmune disorders [7]. The risk of lymphoma in IBD patients while taking infliximab has been a controversial topic. A systematic analysis of the literature on the treatment-associated risks of infliximab calculated a 0.2% risk of lymphoma and a 0.4% risk of dying from sepsis [8]. Although the risk has not been clearly quantified, there appears to be a small, but real, increased risk of lymphoma in IBD patients who are treated with anti-TNF [9, 10].

There are limited data about how patients feel about these risks and the possible benefits of early aggressive therapy and what risks they are willing to take for a potential benefit of remission. Shared decision-making is increasingly advocated as an ideal model of treatment decision-making [11]. In this model, the physician has the responsibility of informing the patients and to give them advice, whereas the actual decisions how to act on this information are made in collaboration between the patient and physician. A critical step in this decision making process is the communication towards the patients, especially concerning the possible risks and benefits of a given treatment and the availability of other treatment options. In order to be able to make a well-based decision, patients should be aware of the chance of responding to the therapy and the risk of side effects. We hypothesized that, although shared decision-making is gaining favor, limited information is given to the patients on the risks and benefits of anti-TNF in clinical practice and that patients misinterpret the given information. Feedback is lacking to see if the patients have interpreted the information correctly. Our aim of this study was therefore to assess IBD patients’ perspectives of the treatment-associated risks and benefits of infliximab.

Methods

A questionnaire was developed based on an English questionnaire which was recently developed in the USA [12]. The questionnaire was translated to Dutch and pilot-tested in a sample of patients from our outpatient IBD clinic. Ten patients were interviewed to ensure full comprehension of the survey. Results and comments from the interviews were used to optimize the questionnaire. The final questionnaire consisted of fifteen closed-ended multiple-choice responses. Between September 1st and October 1st 2006, all patients from the outpatient IBD clinic in our referral center were asked to anonymously complete the survey. The survey consisted of questions concerning respondent characteristics, current and past use of infliximab, estimations of the initial response rate to infliximab at 2 weeks and 1 year, and estimations of serious side effects of infliximab. Finally, patients were given the description of a hypothetical new drug for the treatment of IBD, which unbeknown to the patient, mirrored the estimated risks for infliximab. Patients were asked for the minimal demanded benefit in order to accept this high-risk medication. The results are reported as descriptive statistics. Ordinal survey items were compared between more than 2 groups using the Kruskal-Wallis test and between two groups using an independent t test. Groups were compared based on age, gender, duration of disease, type of IBD, minimal demanded benefit for a hypothetical new drug and current or past use of infliximab. Duration of disease was subdivided into 5 different groups (<1 year, 2–5 years, 6–10 years, 11–19 years and >20 years of disease).

Results

Patient Characteristics

One hundred and sixty-five questionnaires were completed. Thirteen questionnaires were excluded since these patients had only answered the demographic questions of the survey and 1 patient claimed not to have IBD. Patient characteristics are shown in table 1. Of the 152 patients, 118 had CD (78%), 22 had UC (15%), and 12 had indeterminate colitis (8%). The mean age of the patients was 38.26 years (SD 13.5), and 61% was female.

Table 1.

Patients’ characteristics

| Crohn’s disease | Ulcerative colitis | Indeterminate colitis | Total | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | 118 | 22 | 12 | 152 |

| Female (%) | 75 (64) | 11 (50) | 7 (58) | 93 (61) |

| Mean age, years (SD) | 38.42±12.8 | 30.82±13.5 | 50.25±12.9 | 38.26±13.5 |

| Duration of disease >10 years, n (%) | 70 (59) | 5 (23) | 6 (50) | 82 (54) |

| Infliximab users, n (%) | 66 (56) | 8 (36) | 6 (50) | 80 (53) |

The questionnaire and number of respondents to the questions are listed in table 2. Seventy-seven percent of the patients (117/152) had heard of infliximab prior to this survey and 53% (80/165) were currently receiving infliximab or had received infliximab in the past.

Table 2.

Questionnaire with number of respondents

| Yes | No | Not sure | Total | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Have you heard of infliximab? | 117 (77%) | 28 (18%) | 7 (5%) | 152 |

| Are you currently using infliximab? | 42 (28%) | 106 (70%) | 4 (3%) | 152 |

| Have you used infliximab in the past? | 60 (40%) | 81 (53%) | 11 (7%) | 152 |

| Have you ever had a discussion about the risks and benefits of infliximab with a health care provider? | 76 (50%) | 59 (40%) | 17 (11%) | 152 |

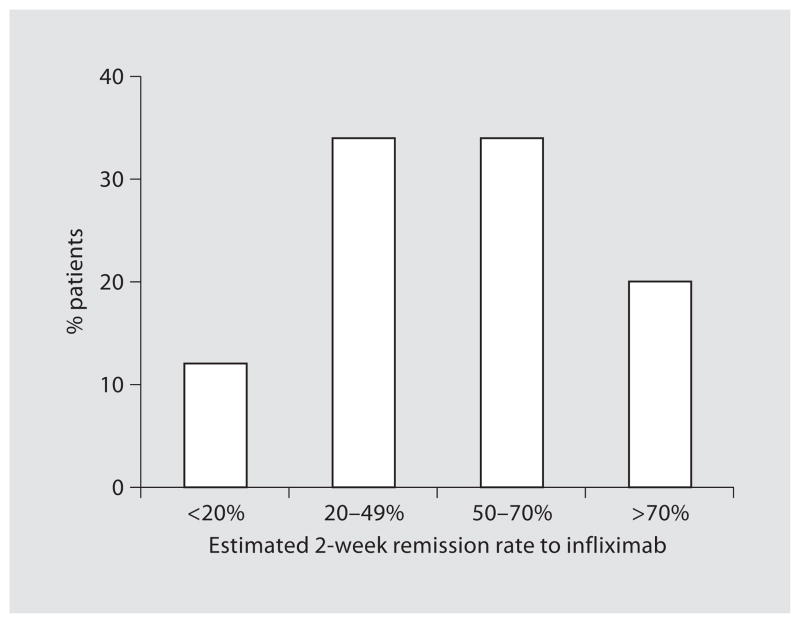

| Patients’ estimates of the chance of remission from infliximab after 2 weeks | figure 1 | 137 | ||

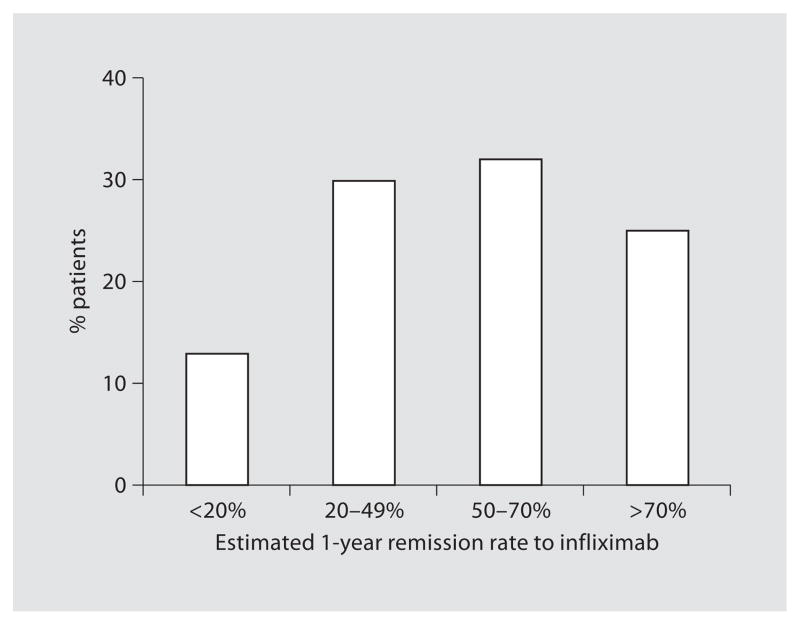

| Patients’ estimates of the chance of remission from infliximab after 1 year | figure 2 | 138 | ||

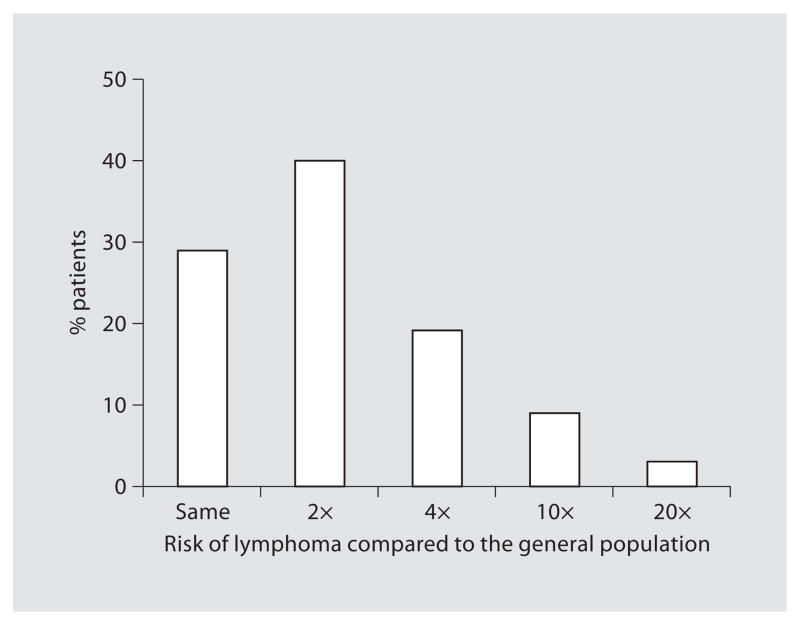

| Patients’ estimates of the risk of lymphoma associated with infliximab compared to the general population | figure 3 | 135 | ||

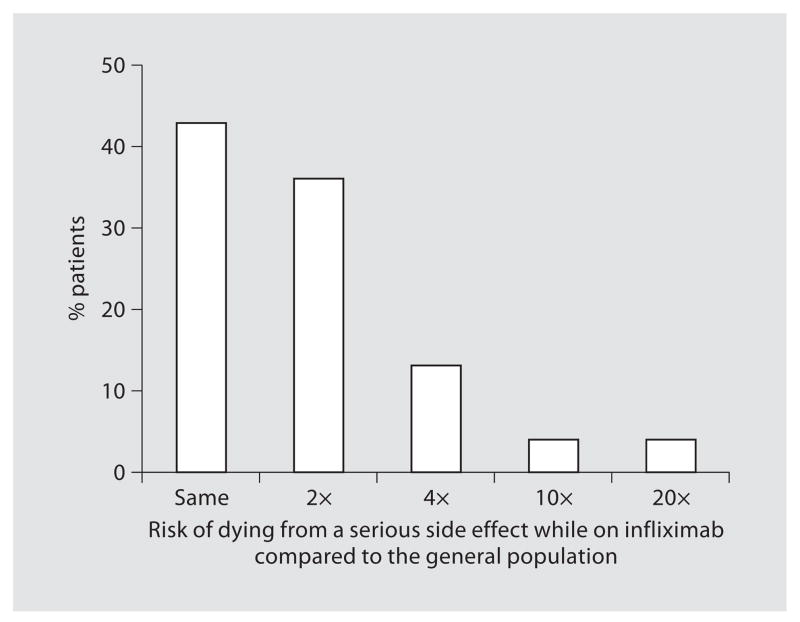

| Patients’ estimates of the risk of dying from a serious side effect of infliximab as compared to the general population | figure 4 | 138 | ||

| Patients’ minimal demanded benefit of a drug with a death rate of 1/250 | figure 5 | 146 |

Limited Information is Shared on Risks and Benefits of Infliximab

In total, 40% of patients recalled having spoken about the risks and benefits of infliximab with their treating physician or nurse practitioner. Fifty-three percent (81/152) could not remember such a conversation and 7% (11/152) were not sure if this discussion had ever taken place. Of the 80 past or current infliximab users 61 patients (76%) could remember having spoken about the risks and benefits of infliximab, 8 patients (10%) were not sure, and 11 patients (14%) did not recall such a conversation.

High Perceived Remission Rates of Infliximab

Patients’ estimates of clinical remission after 2 weeks and 1 year of treatment with infliximab are demonstrated in figures 1 and 2. Fifty-four percent of patients (74/137) estimated the remission rate to be greater than 50% after 2 weeks of infliximab and 57% (78/138) estimated a remission rate greater than 50% after 1 year.

Fig. 1.

Patients’ estimates of the chance of remission from infliximab after 2 weeks (n = 137).

Fig. 2.

Patients’ estimates of the chance of remission from infliximab after 1 year (n = 138).

Low Perceived Treatment-Associated Risks of Infliximab

The estimated chances of serious side effects like lymphoma and dying of a serious infection are shown in figures 3 and 4. Sixty-nine percent of patients that answered this question (93/135) assessed the infliximab-associated risk of lymphoma to be the same or no higher than twice that of the general population. Concerning the risk of dying from a serious side effect of infliximab, 43% (60/138) answered that infliximab-use was not associated with a higher mortality risk and 36% of patients (49/138) estimated that this chance of dying was not more than twice the mortality risk of the general population.

Fig. 3.

Patients’ estimates of the risk of lymphoma associated with infliximab compared to the general population (n = 135).

Fig. 4.

Patients’ estimates of the risk of dying from a serious side effect of infliximab as compared to the general population (n = 138).

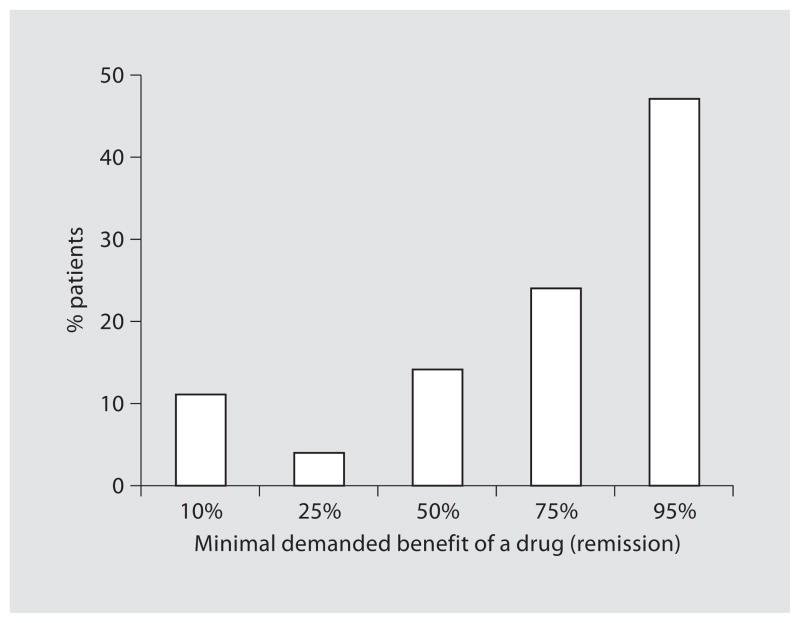

Minimal Demanded Benefit Is a 75% Remission-Rate

Seventy-one percent of patients (104/146) would demand at least a 75% chance of remission before considering taking such a high-risk drug. Forty-seven percent of these patients (69/146) would even demand at least a 95% remission rate (fig. 5). Fifty percent (52/104) of the patients demanding at least a 75% remission rate and 45% (31/69) of the patients demanding a 95% remission rate were currently using infliximab or had used infliximab in the past. Patients demanding at least a 75% remission rate estimated the 2-week remission rate higher than patients that demanded a remission rate <75% (p = 0.006). Of the patients demanding a 75% remission rate, 69% (76/111) assessed the infliximab-associated risk of lymphoma to be the same or no higher than twice that of the general population and 77% (86/112) perceived the mortality risk to be the same or not higher than twice that of the general population. There was no significant difference in estimates of risks and benefits of infliximab among the different categories of minimal demanded benefits of a hypothetical drug.

Fig. 5.

Patients’ minimal demanded benefit of a drug with a death rate of 1/250 (n = 146).

Past or Current Infliximab Use Significantly Influences Patients’ Perceptions

Ever use of infliximab, either in the past or at present, significantly influenced the perception of the 2-week remission rates due to infliximab (p = 0.011). Eighteen percent of ever users of infliximab (11/62) compared to 7% of non-users (5/75) estimated the 2-week remission rate to be <20%. Current users of infliximab gave higher perceptions of the 2-week remission rate (p = 0.016) and the 1-year remission rate (p = 0.008) than those who were not currently treated with infliximab (p = 0.016). Forty-eight of 97 non-users (49%) compared with 28 of 37 users (76%), estimated remission rate >50% (p = 0.04). This estimation of the 1-year remission rate was also higher in current users compared to past users (p = 0.05). There was no significant difference between past and current users of infliximab with regard to the other estimations of benefits/risks.

CD and Prior Counseling Lead to Higher Perceptions of Benefits

Patients with CD estimated the 1-year remission rate due to infliximab higher than patients with UC (p = 0.03). Patients that recalled a discussion regarding the risks and benefits of infliximab also estimated this 1-year remission rate higher than those who did not recall such a discussion (p = 0.03).

Males Estimate Treatment-Associated Risks of Infliximab Higher than Females

With regard to the risks of lymphoma while taking infliximab, 80% of the females (67/84) compared with 51% of the males (26/51) predicted this chance to be the same or not higher than twice that of the general population (p < 0.001). Concerning the mortality risk, 89% of females (67/85) compared with 62% of the males (33/53) estimated the mortality risk of infliximab to be the same or not more than twice the baseline risk (p = 0.001). Patients’ estimates were not significantly different when comparing groups of respondents based on age or duration of disease.

Discussion

This study demonstrates a wide range of estimates of the risks and benefits of infliximab. As compared to the large randomized maintenance trials for CD and UC [3, 4] and a systematic risk analysis [8], the majority of patients are overestimating the remission rates and may be underestimating the risks of infliximab. This optimistic view may be explained by various reasons. Firstly, patients that recalled having spoken with their physician about the risks of infliximab had higher estimates of the 1-year remission rate compared with people who did not recall such a conversation. This suggests that treating physicians may have conveyed an optimistic view, possibly due to the physicians’ own positive perception of the available data, lack of time to adequately discuss the benefits and risks, or because physicians wanted to encourage the patient to accept the treatment. A second reason for patients’ optimism may be that they discount concerning news and want to stay hopeful for their future.

In addition to the high estimations of the remission rates, patients also demand a high remission rate before willing to accept treatment-associated risks. Seventy-one percent of the patients would only consider taking a high-risk drug when associated with a 1-year remission rate of at least 75% and almost half of them would even demand at least a 95% remission rate. Long-term remission rates approaching 75% have only been achieved using infliximab early in the disease course (early aggressive treatment) [6]. Conventional therapies have not been able to prevent complications or surgery in IBD, nor did the implementation of immunosuppressants change the course of disease. In addition to the Belgian and Dutch open randomized trial on early combined immunosuppression, a group of French investigators also demonstrated that treatment with infliximab plus azathioprine led to better response in CD patients not treated previously with azathioprine/6-MP compared with those who had previously received azathioprine/6-MP [6, 13]. Therefore, changing the course of disease might only be feasible early in the disease. Our study demonstrates that patients are willing to accept treatment-associated risks as long as the remission rates are high, which up till today have solely been achieved with early aggressive treatment.

Of our patients demanding such a high remission rate of >75% before willing to accept the associated risks, 50% were currently using infliximab or had used it in the past. Since these risks were in fact mirroring the risks associated to the use of infliximab, these results suggest a lack of proper understanding of risks and benefits of infliximab. A possible explanation is that the precise risks are lacking due to controversy in literature, or that patients are not informed correctly. Another possibility is that the patients have problems interpreting the information accurately and cannot put them in perspective. To interpret available information accurately, patients should be able to comprehend percentages and very small numbers and should in addition have an understanding of probabilities. Furthermore, patients were put in a hypothetical scenario. This is in fact an effective method for standardization, but it is still possible that patients would answer differently when put in an actual situation in which they are suffering from a severe disease and have to decide on their therapy. However, our results are indeed based on patients from a referral center, reflecting those with a chronic severe disease that are often difficult to treat.

Our study confirms the results of a similar questionnaire distributed to 165 IBD patients and parents of IBD patients in the United States [12]. Other data concerning IBD patients’ perceptions of treatment-associated risks and benefits as well as the minimal demanded benefit of therapy are lacking.

In summary, this study firstly demonstrates that IBD patients misperceive the effectiveness of infliximab and may misunderstand its risks. In addition, patients are making treatment choices without adequate information. Better communication to patients concerning the risks and benefits of treatment is necessary in order to appropriately involve patients in the decision-making process. Secondly, this study demonstrates that patients demand a high remission rate before they are willing to accept treatment related risks. Early aggressive treatment is the only treatment strategy that approaches patients’ minimal demands of treatment-related benefits in exchange for the risks of side effects. Therefore, based on its high response rate, early aggressive treatment may be more acceptable to patients than other treatment algorithms.

References

- 1.Vermeire S, Van Assche G, Rutgeerts P. Review article: Altering the natural history of Crohn’s disease: evidence for and against current therapies. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2007;25:3–12. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2036.2006.03134.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Cosnes J, Nion-Larmurier I, Beaugerie L, Afchain P, Tiret E, Gendre JP. Impact of the increasing use of immunosuppressants in Crohn’s disease on the need for intestinal surgery. Gut. 2005;54:237–241. doi: 10.1136/gut.2004.045294. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hanauer SB, Feagan BG, Lichtenstein GR, Mayer LF, Schreiber S, Colombel JF, Rachmilewitz D, Wolf DC, Olson A, Bao W, Rutgeerts P. Maintenance infliximab for Crohn’s disease: the ACCENT I randomised trial. Lancet. 2002;359:1541–1549. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(02)08512-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Rutgeerts P, Sandborn WJ, Feagan BG, Reinisch W, Olson A, Johanns J, Travers S, Rachmilewitz D, Hanauer SB, Lichtenstein GR, de Villiers WJ, Present D, Sands BE, Colombel JF. Infliximab for induction and maintenance therapy for ulcerative colitis. N Engl J Med. 2005;353:2462–2476. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa050516. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sands BE, Anderson FH, Bernstein CN, Chey WY, Feagan BG, Fedorak RN, Kamm MA, Korzenik JR, Lashner BA, Onken JE, Rachmilewitz D, Rutgeerts P, Wild G, Wolf DC, Marsters PA, Travers SB, Blank MA, Van Deventer SJ. Infliximab maintenance therapy for fistulizing Crohn’s disease. N Engl J Med. 2004;350:876–885. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa030815. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.D’Haens G, Baert F, Van Assche G, Caenepeel P, Vergauwe P, Tuynman H, De Vos M, van Deventer S, Stitt L, Donner A, Vermeire S, Van de Mierop FJ, Coche JC, van der Woude J, Ochsenkühn T, van Bodegraven AA, Van Hootegem PP, Lambrecht GL, Mana F, Rutgeerts P, Feagan BG, Hommes D. Early combined immunosuppression or conventional management in patients with newly diagnosed Crohn’s disease: an open randomised trial. Lancet. 2008;371:660–667. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(08)60304-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Colombel JF, Loftus EV, Jr, Tremaine WJ, Egan LJ, Harmsen WS, Schleck CD, Zinsmeister AR, Sandborn WJ. The safety profile of infliximab in patients with Crohn’s disease: the Mayo clinic experience in 500 patients. Gastroenterology. 2004;126:19–31. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2003.10.047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Siegel CA, Hur C, Korzenik JR, Gazelle GS, Sands BE. Risks and benefits of infliximab for the treatment of Crohn’s disease. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2006;4:1017–1024. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2006.05.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Jones JL, Loftus EV., Jr Lymphoma risk in inflammatory bowel disease: is it the disease or its treatment? Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2007;13:1299–1307. doi: 10.1002/ibd.20211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Siegel CA, Marden SM, Persing SM, Larson RJ, Sands BE. Risk of lymphoma associated with anti-TNF agents for the treatment of Crohn’s disease: a meta-analysis. Gastroenterology. 2008;134:A14. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2009.01.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Charles C, Gafni A, Whelan T. Shared decision-making in the medical encounter: what does it mean? (or it takes at least two to tango) Soc Sci Med. 1997;44:681–692. doi: 10.1016/s0277-9536(96)00221-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Siegel CA, Levy LC, Mackenzie TA, Sands BE. Patient perceptions of the risks and benefits of infliximab for the treatment of inflammatory bowel disease. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2008;14:1–6. doi: 10.1002/ibd.20283. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lemann M, Mary JY, Duclos B, Veyrac M, Dupas JL, Delchier JC, Laharie D, Moreau J, Cadiot G, Picon L, Bourreille A, Sobahni I, Colombel JF. Infliximab plus azathioprine for steroid-dependent Crohn’s disease patients: a randomized placebo-controlled trial. Gastroenterology. 2006;130:1054–1061. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2006.02.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]