Abstract

Paradoxically, stimulation of 5-HT1B receptors (5-HT1BRs) enhances sensitivity to the reinforcing effects of cocaine but attenuates incentive motivation for cocaine as measured using the extinction/reinstatement model. We revisited this issue by examining the effects of a 5-HT1BR agonist, CP94253, on cocaine reinforcement and cocaine-primed reinstatement, predicting that CP94253would enhance cocaine-seeking behavior reinstated by a low priming dose, similar to its effect on cocaine reinforcement. Rats were trained to self-administer cocaine (0.75 mg/kg, i.v.) paired with light and tone cues. For reinstatement experiments, they then underwent daily extinction training to reduce cocaine-seeking behavior (operant responses without cocaine reinforcement). Next, they were pre-treated with CP94253 (3–10 mg/kg, s.c.) and either tested for cocaine-primed (10 or 2.5 mg/kg, i.p.) or cue-elicited reinstatement of extinguished cocaine-seeking behavior. For reinforcement, effects of CP94253 (5.6 mg/kg) across a range of self-administered cocaine doses (0–1.5 mg/kg, i.v.) were examined. Cocaine dose-dependently reinstated cocaine-seeking behavior, but contrary to our prediction, CP94253 reduced reinstatement with both priming doses. Similarly, CP94253 reduced cue-elicited reinstatement. In contrast, CP94253 shifted the self-administration dose-effect curve leftward, consistent with enhanced cocaine reinforcement. When saline was substituted for cocaine, CP94253 reduced response rates (i.e. cocaine-seeking behavior). In subsequent control experiments, CP94253 decreased open-arm exploration in an elevated plus-maze suggesting an anxiogenic effect, but had no effect on locomotion or sucrose reinforcement. These results provide strong evidence that stimulation of 5-HT1BRs produces opposite effects on cocaine reinforcement and cocaine-seeking behavior, and further suggest that 5-HT1BRs may be a novel target for developing medications for cocaine dependence.

Keywords: CP94253, extinction, motivation, reinstatement, relapse, sucrose reinforcement

INTRODUCTION

Exposure to cocaine and cocaine-associated stimuli can elicit incentive motivational effects in drug abusers that can lead to craving and relapse (Ehrman et al. 1992; Leshner & Koob 1999). Incentive motivation for cocaine is measured in animals using the extinction/reinstatement model (de Wit & Stewart 1981), whereby animals are first trained to perform an operant response reinforced with cocaine, followed by extinction training during which responses produce no consequences. Responding in the absence of drug reinforcement is defined as cocaine-seeking behavior and is thought to provide a measure of incentive motivation for cocaine. After cocaine-seeking behavior is extinguished, responding is reinstated by either cocaine-priming injections or the presentation of cocaine-paired cues, reflecting the incentive motivational effects of these respective stimuli.

Cocaine increases serotonin (5-HT) neurotransmission (Koe 1976; Li et al. 1996) and 5-HT systems play a critical role in the behavioral effects of cocaine in both animals and humans (Walsh & Cunningham 1997; Burmeister et al. 2004; Filip et al. 2005; Muller et al. 2007). In cocaine-dependent humans, acute 5-HT depletion reduces the euphorigenic effects of intranasal cocaine (Aronson et al. 1995) and self-reports of craving elicited by cocaine-associated cues when subjects are in a cocaine-free state (Satel et al. 1995). In animals, elevating 5-HT decreases cocaine self-administration (Carroll et al. 1990; Richardson & Roberts 1991; Peltier & Schenk 1993), whereas either increasing (Baker et al. 2001; Burmeister, Lungren & Neisewander 2003) or decreasing (Tran-Nguyen et al. 1999, 2001) 5-HT attenuates cue-elicited reinstatement of extinguished cocaine-seeking behavior but has inconsistent effects on cocaine-primed reinstatement. The non-linear relationship between 5-HT and motivation for cocaine, and the inconsistency of 5-HT effects on cocaine priming, are likely related to the complexity of 5-HT receptor subtypes and their differential regulation by chronic cocaine (e.g. Cunningham, Paris & Goeders 1992; Darmani, Martin & Glennon 1992; Neumaier et al. 2002).

The role of 5-HT1B receptors (5-HT1BRs) in cocaine-related behaviors is particularly complex. 5-HT1BRs are Gi-coupled receptors located on axon terminals throughout the mesocorticolimbic dopamine system, whereby they exert inhibitory control over neuronal activity through negative coupling with adenylate cyclase (Morikawa et al. 2000; Sari 2004). For example, 5-HT1BRs located on γ-aminobutyric acid (GABA)ergic neurons projecting from the nucleus accumbens (NAc) shell to the ventral tegmental area (VTA) inhibit GABA release, thereby disinhibiting dopaminergic target neurons and increasing the behavioral effects of cocaine (O’Dell & Parsons 2004;Yan, Zheng &Yan 2004). Studies examining cocaine self-administration using 5-HT1BR knockout mice (Rocha et al. 1998; Castanon et al. 2000) or that have examined amphetamine self-administration (Fletcher & Korth 1999a; Fletcher, Azampanah & Korth 2002) suggest that 5-HT1BRs may inhibit psychostimulant reinforcement. However, cocaine self-administration studies suggest that 5-HT1BRs enhance the rewarding effects of cocaine. For instance, 5-HT1BR agonists dose-dependently decrease responding on a fixed ratio (FR) schedule and increase responding on a progressive ratio schedule of reinforcement, suggesting reward enhancement (Parsons, Weiss & Koob 1998; Przegalinski et al. 2007). Consistent with this interpretation, CP94253, a 5-HT1BR agonist, enhances cocaine-conditioned place preference (CPP) even though the drug produces conditioned place aversion when given alone (Cervo et al. 2002). Furthermore, increased expression of 5-HT1BRs in the VTA shifts the cocaine-CPP dose-response curve leftward (Neumaier et al. 2002), and 5-HT1BR knockout mice fail to exhibit cocaine-CPP relative to their wild type counterparts (Belzung et al. 2000). Finally, 5-HT1BR agonists partially substitute for, and produce a leftward shift in, the dose-response curve for the discriminative stimulus effects of cocaine (Callahan & Cunningham 1995, 1997; Filip et al. 2001).

In contrast to the 5-HT1BR-induced enhancement of cocaine effects described above, the 5-HT1B/1AR agonist RU24969 elevates intracranial self-stimulation (ICSS) thresholds, yet dose-dependently attenuates cocaine-induced decreases in ICSS thresholds, suggesting a decrease in brain-stimulation reinforcement (Harrison et al. 1999). Furthermore, we have reported that the agonist RU24969 decreases cocaine-primed reinstatement of extinguished cocaine-seeking behavior (Acosta et al. 2005). These effects were reversed by the 5-HT1BR antagonist GR127935, suggesting 5-HT1BR mediation. We suggested that RU24969 may have produced a cocaine-like satiating effect when given prior to the high 10 mg/kg cocaine-priming dose, thereby decreasing cocaine-seeking behavior.

The present study sought to clarify the role of 5-HT1BRs in the motivational and rewarding effects of cocaine by examining dose-dependent effects of the selective 5-HT1BR agonist CP94253 on cocaine self-administration and cocaine-primed reinstatement of extinguished cocaine-seeking behavior. We hypothesized that 5-HT1BR stimulation enhances both the rewarding and incentive motivational effects of cocaine. Accordingly, we predicted that the former would manifest as a shift to the left of the cocaine self-administration dose-effect function and the latter would manifest as enhanced cocaine-seeking response rates at a low priming dose, but attenuated response rates at a high priming dose because of a cocaine-like satiation effect as suggested previously (Acosta et al. 2005). To examine whether the CP94253 effects observed were specific to cocaine priming and reinforcement, and to test for potential confounding effects, we also investigated the effects of CP94253 on cue-elicited reinstatement of cocaine-seeking behavior, sucrose reinforcement, locomotion and anxiety-like behavior in the elevated plus-maze (EPM).

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Animals

Male Sprague–Dawley rats weighing 250–380 g at the time of surgery were individually housed in a climate-controlled colony room with a 12-hour reversed light/dark cycle (lights off at 6 am). Animal care and housing were in adherence to the conditions set forth in the ‘Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals’ (Institute of Laboratory Animal Resources on Life Sciences, National Research Council, 1996).

Surgery

Animals were handled daily for at least 6 days prior to surgery. Rats were pre-treated with atropine sulfate (10 mg/kg, i.p.; Sigma Chemical, St. Louis, MO) and anesthetized with sodium pentobarbital (50 mg/kg, i.p.; Sigma Chemical) in order to implant intravenous catheters into the jugular vein; surgical procedures were performed as described by Neisewander et al. (2000). Following surgery, animals were returned to their home cage for at least 5 days of recovery prior to the start of self-administration training. In order to prevent infection and maintain patency, catheters were flushed daily with 0.1 ml bacteriostatic saline containing heparin sodium (10 U/ml; Elkinns-Sinn Inc., Cherry Hill, NJ), streptokinase (0.67 mg/ml; Astra USA, Inc., Westborough, MA) and ticarcillin disodium (66.7 mg/ml; Smithkline Beecham Pharmaceuticals, Philadelphia, PA). Proper catheter function was tested periodically by administering 0.05 ml methohexital sodium (16.6 mg/ml; Jones Pharma Inc., St. Louis, MO), a dose that produces brief anesthetic effects only when administered intravenously.

Drugs

Cocaine hydrochloride (RTI International, Research Triangle Park, NC) and CP94253 (Tocris Cookson Inc., Ellisville, MO) were dissolved in bacteriostatic saline and filtered through 0.2 µm filters; CP94253 was gently heated to achieve solubility.

Self-administration training

Self-administration training occurred in operant conditioning chambers (28 × 10 × 20 cm; Med Associates, St. Albans, VT) equipped with an active lever, an inactive lever, a cue light 4 cm above the active lever, a tone generator (500 Hz, 10 dB above background noise) and a house light on the top center of the wall opposite the levers. Each operant conditioning chamber was housed within a larger ventilated sound-attenuating chamber. Infusion pumps (Med Associates) were connected to liquid swivels (Instech, Plymouth Meeting, PA) located above the chambers. The swivels were fastened to the catheters via polyethylene 20 tubing encased inside a metal spring leash (Plastics One, Roanoke, VA).

Animals were trained to self-administer cocaine (0.75 mg/kg/0.1 ml, i.v.) 6 days/week during 2-hour sessions that occurred during their dark cycle. Animals tested for the effects of CP94253 on reinstatement of cocaine-seeking behavior received 16–19 training sessions; animals tested for the effects of CP94253 on cocaine reinforcement received their first test after 24 training sessions, and received 53–60 total sessions including those that occurred during the training and testing phases. During training, schedule completions on the active lever resulted in the simultaneous activation of the cue light, house light and tone generator, followed 1 second later by a 6-second cocaine infusion. All stimuli were inactivated with the termination of the infusion except the house light, which remained activated signaling a 20-second time-out period, during which lever presses were recorded but produced no consequences. Inactive lever presses were recorded throughout training but produced no consequences. No cocaine-priming infusions were administered at any point during training.

To facilitate acquisition of cocaine self-administration (Carroll, France & Meisch 1981), rats were initially restricted to 16 g of food/day beginning 2 days prior to training. Subjects were maintained on food restriction (16–22 g) until their final schedule was achieved for 2 consecutive days, after which they were given ad libitum access to food throughout the rest of self-administration, extinction and reinstatement testing. We chose to train subjects tested for either cocaine or sucrose reinforcement on a schedule that progressed from an FR1 to an FR5 based on replicating the previous findings of Parsons et al. (1998), whereas we chose to train subjects in the reinstatement experiments on a schedule that progressed from an FR1 to an FR11 based on replicating some of our previous findings (Acosta et al. 2005, 2008). An FR11 schedule produces higher reinstatement response rates relative to FR1, thereby increasing sensitivity to detect CP94253-induced decreases in cocaine-seeking behavior (Acosta et al. 2008).

Extinction training

Extinction training began the day after the last self-administration session and consisted of 1-hour exposures to the self-administration environment across 22–37 consecutive days. During extinction sessions, active and inactive lever responses were recorded but produced no consequences. Extinction training continued until response rates declined to less than 20 active lever responses/hour or to an 80% decrease in response rates compared with the highest rate observed during extinction. In order to control for effects of injection stress on responding during cue-elicited or cocaine-primed reinstatement testing, animals received a subcutaneous saline injection 15 minutes before their last two extinction sessions, which had no effect on response rates.

Effects of CP94253 on cue reinstatement

After self-administration and extinction training, rats were assigned to a CP94253 dosage group (3.0, 5.6 and 10 mg/kg, s.c.) counterbalanced for previous cocaine intake (n = 8–10/group). Cue-induced reinstatement of cocaine-seeking behavior was tested twice using a within-subjects design in which rats were pre-treated with saline or their assigned dose of CP94253 15 minutes prior to testing, with order of pre-treatment counterbalanced. Responses on the active lever during the test sessions resulted in response-contingent presentations of the same stimulus complex that had been previously paired with cocaine infusions on an FR1 schedule of reinforcement. Animals received a passive cue presentation at the start of behavioral testing. Animals received at least three additional 1-hour extinction sessions between reinstatement tests to restabilize baseline response rates.

Effects of CP94253 on 10 mg/kg, i.p. cocaine-primed reinstatement

The rats tested above received at least four additional 1-hour extinction sessions after their last cue reinstatement test to restabilize baseline response rates. They were then tested for the effects of their assigned dose of CP94253 (3.0, 5.6 and 10 mg/kg, s.c.) on cocaine-primed reinstatement (i.e. rats received the same dose as that given during cue reinstatement). Rats were tested twice using a within-subjects design, receiving pre-treatment of saline or their assigned dose of CP94253 15 minutes prior to testing, with order of pre-treatment counterbalanced (n = 10–11/group). Immediately after the 10 mg/kg, i.p. cocaine-priming injection, animals were placed into the operant conditioning chambers for a 1-hour test session, during which responses produced no consequences. Animals received at least three additional daily 1-hour extinction sessions between reinstatement tests to restabilize baseline response rates.

Effects of CP94253 on 2.5 mg/kg, i.p. cocaine-primed reinstatement

A new cohort of rats was assigned to groups (n = 12–13/group) to test the effects of CP94253 (3.0, 5.6 and 10 mg/kg, s.c.) on cocaine-primed reinstatement using a low cocaine-priming dose (2.5 mg/kg, i.p.). Except for incorporating a lower priming dose, all other training and testing procedures were identical to those described previously for the 10 mg/kg cocaine-priming reinstatement test.

Effects of CP94253 alone on reinstatement of extinguished cocaine-seeking behavior

A new cohort of rats was assigned to groups (n = 4–7/group) to test the effects of CP94253 itself (3.0, 5.6 and 10 mg/kg, s.c.) on reinstatement. These animals underwent identical training and testing conditions as described for the priming experiments above, except that they only received the CP94253 pre-treatment, and no cocaine primes, before testing.

Effects of CP94253 on cocaine reinforcement

A new cohort of rats was assigned to groups to test the effects of CP94253 (5.6 mg/kg, s.c.) on the cocaine self-administration dose-effect function using cocaine doses of 0, 0.1875, 0.375, 0.75 and 1.5 mg/kg, i.v. . The minimally effective dose of CP94253 (5.6 mg/kg) that attenuated cocaine-seeking behavior during reinstatement testing was used to determine whether this agonist would produce a shift in the cocaine dose-effect function. Training sessions were identical to those of previous experiments; however, self-administration training continued until the total number of drug infusions per session stabilized to within ± 10% for 3 consecutive days (baseline criteria). All animals were tested twice at each cocaine dose using a within-subjects experimental design, with cocaine doses presented in descending order (n = 8). Once stable responding was achieved, subjects were pre-treated with saline 15 minutes before one test, and CP94253 15 minutes prior to the other test, with order of these conditions counterbalanced. Between each test session subjects were restabilized on their training dose of cocaine (0.75 mg/kg, i.v.).

Effects of CP94253 on sucrose reinforcement

New cohorts of rats were used to test the effects of CP94253 on sucrose reinforcement. Rats were food-restricted to 16 g of food/day beginning 2 days prior to sucrose training. Animals received 14 daily, 30-minute sessions progressing from an FR1 to an FR5 schedule of reinforcement. Completion of a reinforcement schedule simultaneously activated the house light, the cue light above the active lever, and a tone (500 Hz, 10 dB above background noise), and the latter two stimuli oscillated on for 1 second and off for 1 second over a 7-second period. A sucrose pellet (45 mg, Noyes) was delivered 1 second after the onset of the stimuli. All stimuli were inactivated 6 seconds after the delivery of the reinforcer except the house light, which remained activated for a 20-second time-out period. Rats remained food-restricted until a criterion of 15 reinforcers on an FR1 schedulewas met for 2 consecutive days, afterwhich they progressed to an FR5 schedule and were given ad libitum access to food throughout the rest of the experiment. Subjects were tested twice at each dose of CP94253, receiving their assigned dose of CP94253 (0.3, 1.0, 3.0, 5.6 or 10 mg/kg, s.c.) 15 minutes prior to one test, and saline 15 minutes prior to the other test, with order counterbalanced (n = 8–12/group).

Effects of CP94253 on spontaneous locomotor activity

Following the completion of sucrose-reinforcement testing, some of this cohort of rats was used to test the effects of CP94253 on spontaneous locomotion following a 10-day washout period from their last CP94253 treatment. Animals were assigned to one of three CP94253 dosage groups (3.0, 5.6 and 10 mg/kg, s.c.) counterbalanced for CP94253 dose given during sucrose-reinforcement testing (n = 5/group). They were tested on consecutive days, receiving their assigned dose of CP94253 15 minutes prior to one test, and saline 15 minutes prior to the other test, with order counterbalanced. Rats were placed into locomotor activity chambers that were made of Plexiglas (36 × 24 × 30 cm high) and that two photobeams had located 25 cm apart and 4 cm above the floor. A computer-automated system recorded the number of times the photobeams were interrupted consecutively by the animals moving from one end of the chamber to the other during 1-hour test sessions.

Effects of CP94253 on anxiety-like behavior in the EPM

Following the completion of sucrose-reinforcement testing, some of this cohort of rats was used to test the effects of CP94253 on anxiety-like behavior in the EPM following a 10-day washout period from their last CP94253 treatment. Animals were assigned to one of three CP94253 dosage groups (0, 3 and 5.6 mg/kg, s.c.) counterbalanced for CP94253 dose given during sucrose-reinforcement testing (n = 9/group). The EPM apparatus consisted of four Plexiglas arms arranged in a cross, elevated 75 cm above the floor. Each arm was 10 cm wide and 50 cm long, and each arm was joined at the center by a 10 cm square platform. The two opposite ‘open’ arms contained no walls, while the other two ‘closed’ arms had 40 cm high sides. Subjects received their assigned dose of CP94253 25 minutes prior to testing, and then were individually placed in the center of the apparatus facing one of the two closed arms. The 5-minute test was conducted under dim lighting, and behaviors were later analyzed from videotapes by a highly trained observer blind to group assignment. The apparatus was cleaned between each test trial.

Statistical analyses

For the cue-elicited and cocaine-primed reinstatement experiments, baseline response rates were defined as the average response rates on the extinction sessions prior to saline and agonist pre-treatment tests. Reinstatement was operationally defined as a minimum of 10 active lever responses and at least a doubling of baseline response rates during either reinstatement tests. Rats that failed to reinstate were eliminated from the experiments, with the exception of rats in the low dose cocaine-priming experiment because we did not expect the 2.5 mg/kg, i.p. cocaine prime to reliably reinstate cocaine-seeking behavior in vehicle pre-treated groups. Therefore, no rats were eliminated from this experiment based on their reinstatement data. Response rates were analyzed using separate mixed factor 3 × 3 analyses of variance (ANOVAs), with test session (baseline, saline pre-treatment and CP94253 pre-treatment) as the repeated-measures factor and CP94253 dose as the between-subjects factor. For cocaine self-administration, cocaine (1.5–0.0 mg/kg, i.v.) and CP94253 (drug or saline pre-treatment) were both repeated measures in a two-way ANOVA. Locomotion was analyzed using a 2 × 3 mixed factor ANOVA, with saline or drug pre-treatment as the repeated measure and the CP94253 dose as the between-subjects factor. For sucrose reinforcement, the 10 mg/kg dosage group was run with a different cohort of rats than the other doses, so these data were analyzed using separate ANOVAs. For the 10 mg/kg dosage group the ANOVA included test session (baseline, saline pre-treatment and CP94253 pre-treatment) as a repeated measure, and for the other dosage groups both test session and drug dose were repeated measures in a 3 × 4 ANOVA. EPM data were analyzed using a oneway ANOVA, with drug dose as the between-subjects factor. Significant effects were followed by post hoc Newman–Keuls tests; α was set at 0.05 for all statistical comparisons.

RESULTS

Effects of CP94253 on cue reinstatement

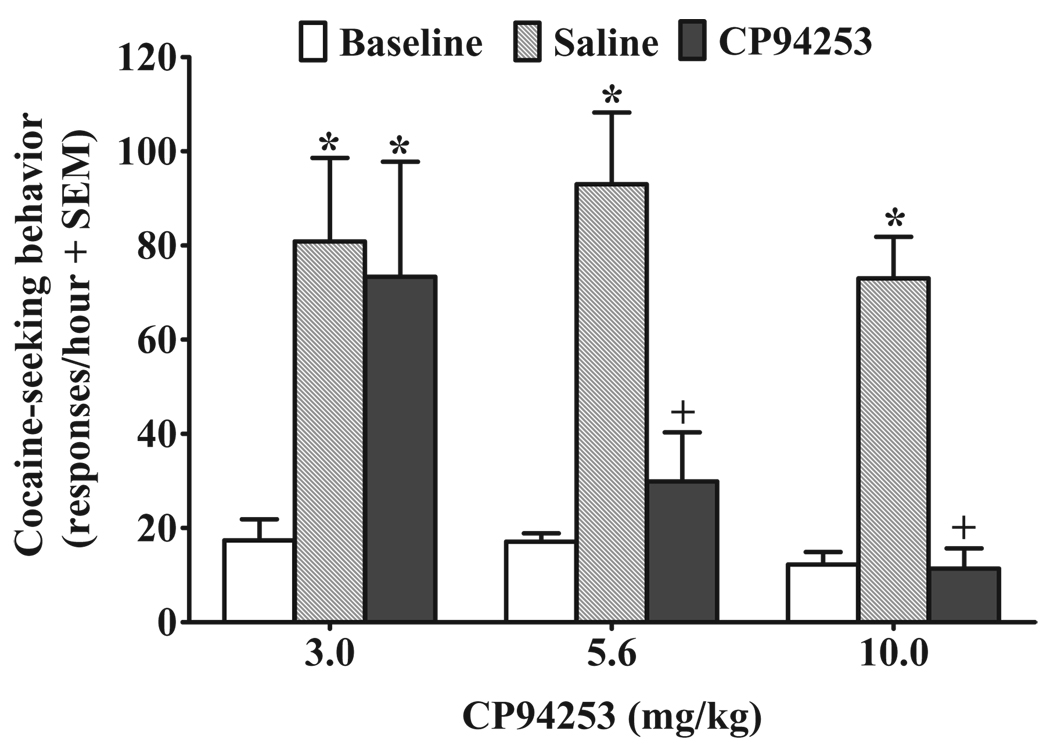

Descriptive data are reported as the mean ± standard error of the mean. The total number of infusions across the 18 self-administration sessions for the 3.0, 5.6 and 10 mg/kg groups averaged 390.25 ± 35.44, 375.20 ± 26.77 and 373.89 ± 47.59, respectively. Over the last 5 days of self-administration training, the 3.0, 5.6 and 10 mg/kg CP94253 groups averaged 282.50 ± 20.36, 293.40 ± 46.62 and 276.48 ± 42.29 active lever presses and 24.35 ± 1.38, 25.97 ± 1.60 and 25.28 ± 3.00 infusions/session, respectively. Figure 1 illustrates the effects of CP94253 on active lever responding during cue-elicited reinstatement of extinguished cocaine-seeking behavior; 2 of the 30 rats failed to reinstate and were excluded from the analysis. The ANOVA of active lever responses revealed amain effect of test session [F(2,50) = 44.7, P < 0.001] and a dosage group by test session interaction [F(4,50) = 3.9, P < 0.01]. Post hoc comparisons indicated an increase in responding on the saline pre-treatment test when response-contingent cues were available, relative to baseline when active lever responses produced no consequences (Newman–Keuls, P < 0.005 in each case), demonstrating cue-elicited reinstatement in all groups pre-treated with saline. CP94253 produced a dose-dependent decrease in cue-elicited reinstatement of extinguished cocaine-seeking behavior as animals receiving the 3 mg/kg dose of CP94253 exhibited an increase in responding relative to baseline (Newman– Keuls, P < 0.001), whereas the 5.6 and 10 mg/kg CP94253 dosage groups did not differ from their respective baselines. Additionally, pre-treatment with both 5.6 and 10 mg/kg of CP94253 attenuated active lever responses following exposure to cocaine-paired cues compared with saline pre-treatment (Newman–Keuls, P < 0.001 in each case); there was no difference between 3.0 mg/kg CP94253 and vehicle controls.

Figure 1.

Effects of CP94253 (3.0, 5.6 and 10 mg/kg, s.c.) on cue-elicited reinstatement of extinguished cocaine-seeking behavior expressed as the mean number of active lever responses during a 1-hour test session + standard error of the mean (SEM). Baselines (white bars) represent mean responses during the extinction sessions preceding each test. Animals (n = 8–10/group) were pre-treated with vehicle (gray bars) 15 minutes prior to one test, and their assigned dose of CP94253 (black bars) 15 minutes before the other test, with order of presentation counterbalanced. Cues were available response-contingently during the test session on a fixed ratio 1 schedule. * Represents a difference from baseline (Newman– Keuls, P < 0.005), and + represents a difference from vehicle pre-treatment test day (Newman–Keuls, P < 0.001)

Effects of CP94253 on 10 mg/kg, i.p. cocaine-primed reinstatement

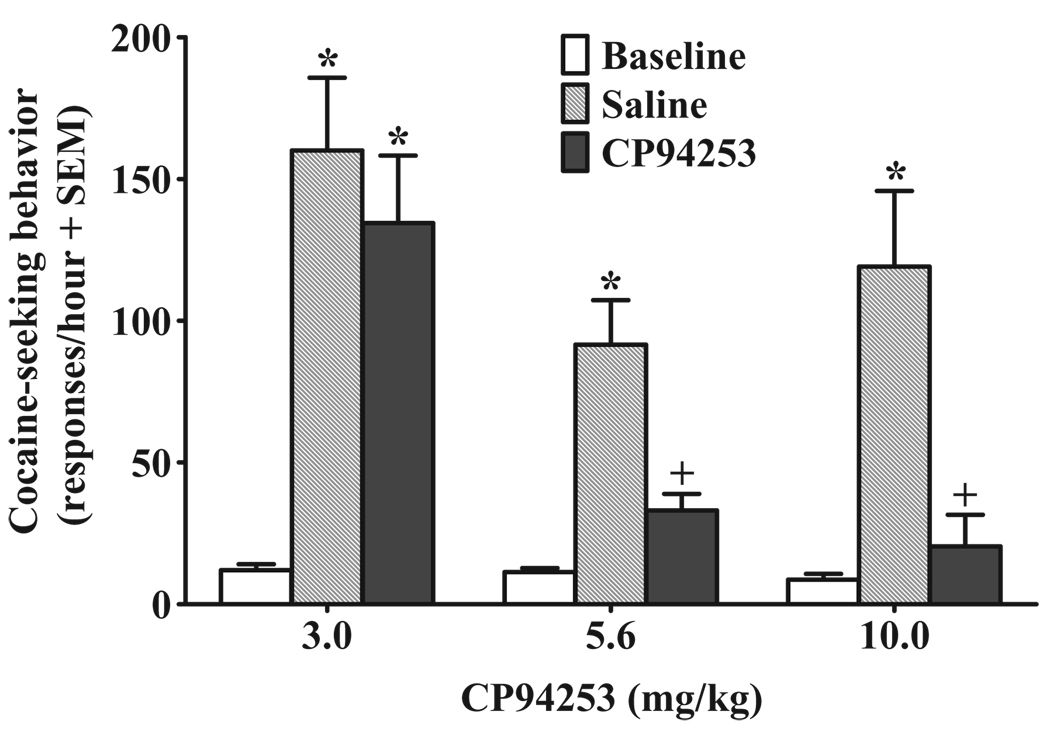

The total number of infusions across the 18 self-administration sessions for the 3.0, 5.6 and 10 mg/kg groups averaged 385.20 ± 38.98, 352.18 ± 27.03 and 375.18 ± 38.80, respectively. Over the last 5 days of self-administration training, rats in the 3.0, 5.6 and 10 mg/kg groups averaged 286.35 ± 18.25, 308.60 ± 36.42 and 253.13 ± 41.68 active lever presses and 24.55 ± 1.28, 25.98 ± 1.59 and 23.98 ± 2.99 infusions, respectively. Figure 2 illustrates the effects of CP94253 on active lever responding during the 10 mg/kg cocaine-primed reinstatement tests; 1 of the 33 rats failed to reinstate and was excluded from the analysis. The ANOVA of active lever responses revealed main effects of dose [F(2,29) = 8.5, p < 0.005] and test session [F(2,58) = 46.0, P < 0.001], and a dosage group by test session interaction [F(4,58) = 4.9, P < 0.005]. Post hoc comparisons indicated an increase in responding on the saline pre-treatment test when cocaine-priming injections were given, relative to baseline when saline-priming injections were administered (Newman–Keuls, P < 0.005 in each case), demonstrating cocaine-primed reinstatement regardless of CP94253 dosage group. CP94253 produced a dose-dependent decrease in cocaine-primed reinstatement of extinguished cocaine-seeking behavior as animals receiving the 3 mg/kg dose of CP94253 exhibited an increase in responding relative to baseline (Newman–Keuls, P < 0.001), whereas the 5.6 and 10 mg/kg CP94253 dosage groups did not differ from their respective baselines. Additionally, pre-treatment with both 5.6 and 10 mg/kg of CP94253 attenuated active lever responses following cocaine priming compared with saline pre-treatment (Newman–Keuls, P < 0.001); there was no difference between 3.0 mg/kg CP94253 and vehicle pre-treatment.

Figure 2.

Effects of CP94253 (3.0, 5.6 and 10 mg/kg, s.c.) on cocaine-primed (10 mg/kg, i.p.) reinstatement of extinguished cocaine-seeking behavior expressed as the mean number of active lever responses during a 1-hour test session + standard error of the mean (SEM). Baselines (white bars) represent mean responses during the extinction sessions preceding each test. Animals (n = 10– 11/group) were pre-treated with vehicle (gray bars) 15 minutes prior to one test, and their assigned dose of CP94253 (black bars) 15 minutes before the other test, with order of presentation counterbalanced. The cocaine prime was administered immediately before testing, and no cues were presented during the test sessions. * Represents a difference from baseline (Newman–Keuls, P < 0.005), and + represents a difference from vehicle pre-treatment test day (Newman–Keuls, P < 0.001)

Effects of CP94253 on 2.5 mg/kg, i.p. cocaine-primed reinstatement

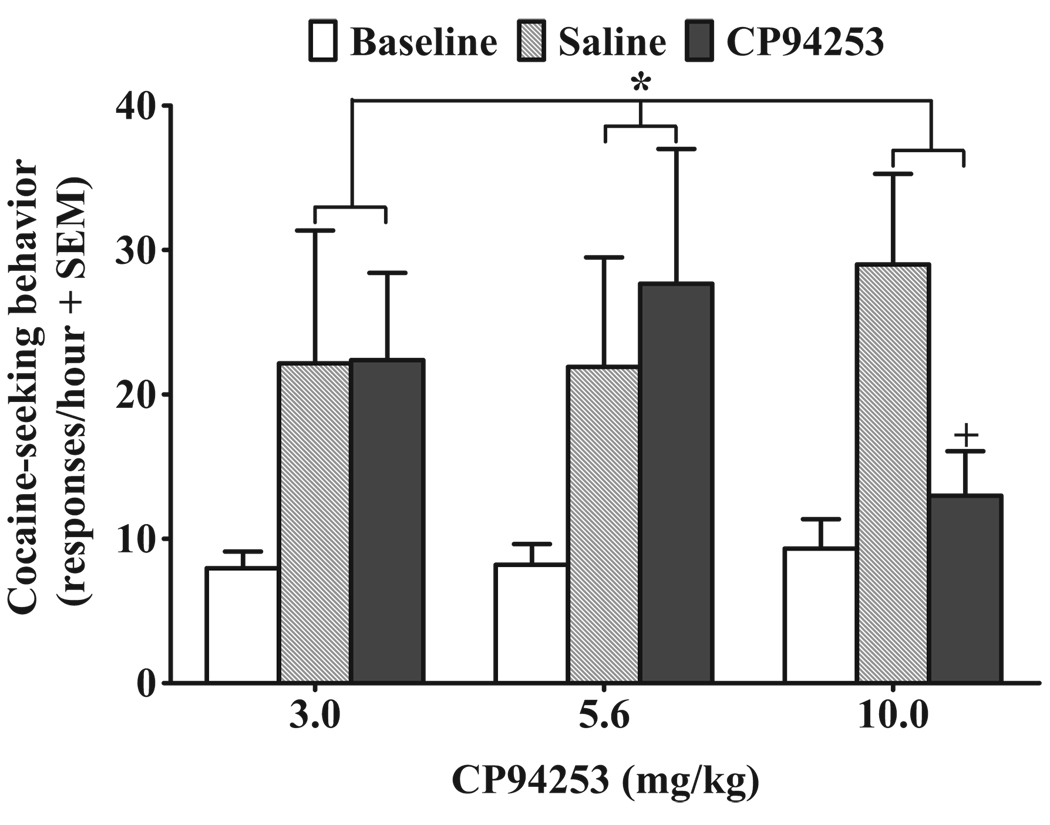

The total number of infusions across the 19 self-administration sessions for the 3.0, 5.6 and 10 mg/kg groups averaged 343.31 ± 25.35, 327.83 ± 28.97 and 345.83 ± 26.90, respectively. Over the last 5 days of self-administration training, rats in the 3.0, 5.6 and10 mg/kg groups averaged 272.85 ± 29.43, 288.50 ± 44.37 and 280.88 ± 26.21 active lever presses and 23.94 ± 2.51, 23.00 ± 2.43 and 24.30 ± 2.10 infusions, respectively. Figure 3 illustrates the effects of CP94253 on active lever responding during 2.5 mg/kg cocaine-primed reinstatement of extinguished cocaine-seeking behavior. CP94253 failed to produce a dosage group by test session interaction, but the ANOVA indicated a main effect of test session [F(2,68) = 6.1, P < 0.05]. When collapsed across CP94253 dosage groups, post hoc Newman–Keuls demonstrated an increase in responding on both the saline (P < 0.01) and drug (P < 0.05) pre-treatment tests relative to baseline, demonstrating cocaine-primed reinstatement regardless of CP94253 dosage group; there was no difference between saline and drug groups when collapsed across dose. However, planned comparisons indicated that CP94253 pre-treatment decreased responding in animals receiving 10 mg/kg CP94253 relative to saline t(11) = 2.2, P < 0.05 (two-tailed), suggesting that this dose of CP94253 decreased 2.5 mg/kg cocaine-primed reinstatement.

Figure 3.

Effects of CP94253 (3.0, 5.6 and 10 mg/kg, s.c.) on cocaine-primed (2.5 mg/kg, i.p.) reinstatement of extinguished cocaine-seeking behavior expressed as the mean number of active lever responses during a 1-hour test session + standard error of the mean (SEM). Baselines (white bars) represent mean responses during the extinction sessions preceding each test. Animals (n = 12–13/group) were pre-treated with vehicle (gray bars) 15 minutes prior to one test, and their assigned dose of CP94253 (black bars) 15 minutes before the other test, with order of presentation counterbalanced. The cocaine prime was administered immediately before testing, and no cues were presented. There was a main effect of day regardless of CP94253 dosage group indicating reinstatement on vehicle and CP94253 test days. * Represents a difference from baseline when collapsed across CP94253 dosage groups (Newman– Keuls, P < 0.05), and + represents a difference from vehicle pre-treatment test day (t-test, P < 0.05)

Effects of CP94253 alone on reinstatement of extinguished cocaine-seeking behavior

The total number of infusions across the 19 self-administration sessions for the 3.0, 5.6 and 10 mg/kg groups averaged 306.50 ± 27.66, 306.43 ± 47.27 and 306.00 ± 41.00, respectively. Over the last 5 days of self-administration training, rats in the 3.0, 5.6 and10 mg/kg groups averaged 268.10 ± 16.23, 310.46 ± 73.14 and 275.87 ± 40.54 active lever presses and 21.75 ± 2.81, 23.51 ± 3.93 and 23.90 ± 3.10 infusions, respectively. Figure 4 illustrates the effects of CP94253 on active lever responding in the absence of cocaine-paired cues or cocaine-priming injections. The ANOVA failed to demonstrate a test session by dose interaction or main effects.

Figure 4.

Effects of CP94253 (3.0, 5.6 and 10mg/kg, s.c.) alone on reinstatement of extinguished cocaine-seeking behavior expressed as the mean number of active lever responses during a 1-hour test session + standard error of the mean (SEM). Animals (n = 4, 7 and 7/group, respectively) were pre-treated with their assigned dose of CP94253 (black bars) 15 minutes before the test. Responses produced no scheduled consequences during testing nor did animals receive cocaine on the test day. Baselines (white bars) represent mean responses during the extinction sessions preceding each test

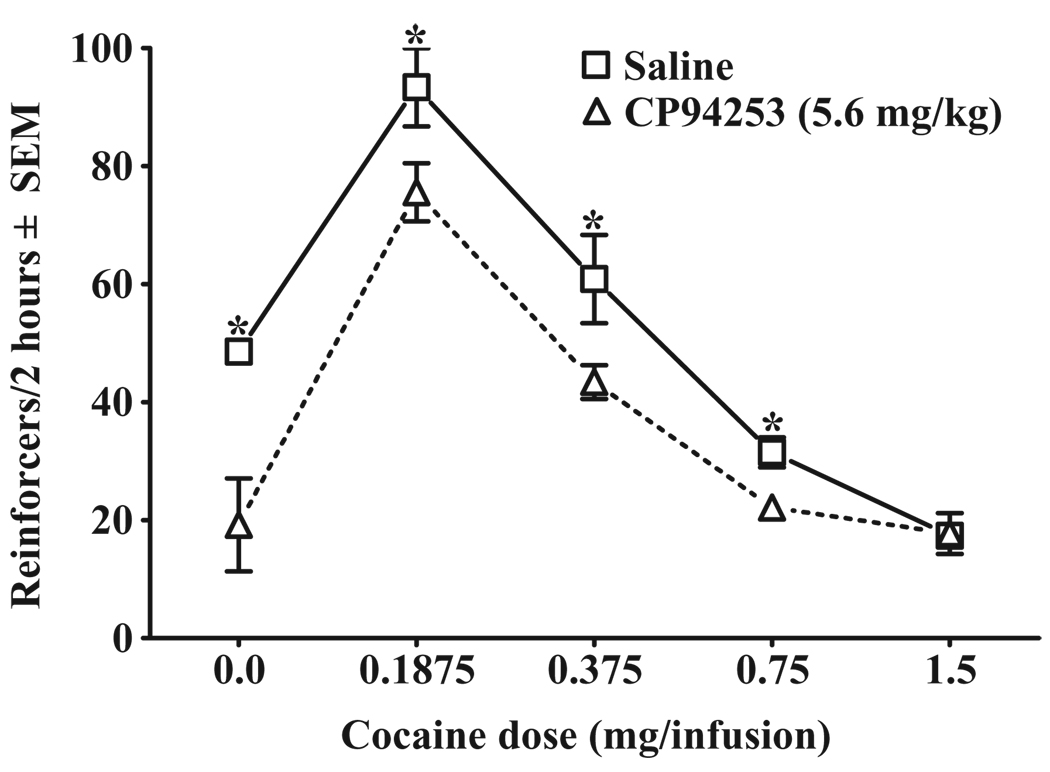

Effects of CP94253 on cocaine self-administration

Figure 5 illustrates the effects of CP94253 (5.6 mg/kg, i.p.) on the cocaine self-administration dose-effect function. Varying the unit doses of cocaine produced a characteristic inverted U-shaped dose-effect function, with the ANOVA indicating a cocaine dose effect [F(4,16) = 155.8, P < 0.001]. Post hoc Newman–Keuls revealed that increasing the unit dose of cocaine reliably decreased total intake at each dose relative to the previous dose of cocaine (P < 0.05). CP94253 pre-treatment produced an overall main effect [F(1,4) = 812.4, P < 0.001] and a cocaine dose by pre-treatment interaction [F(4,16) = 7.3, P < 0.01]. Post hoc analysis indicated that CP94253 pre-treatment dose-dependently decreased self-administration, reducing total intake at cocaine doses of 0.75, 0.375 and 0.1875 mg/kg (P < 0.01 in each case), but not at 1.5 mg/kg cocaine, compared with vehicle controls. When saline was substituted for cocaine, CP94253 pre-treatment decreased the number of infusions (P < 0.05) compared with vehicle.

Figure 5.

Effects of CP94253 (5.6 mg/kg, s.c.) on the cocaine self-administration dose-response function expressed as the mean number of reinforcers in a 2-hour test session ± standard error of the mean (SEM). Animals (n = 8/group) were tested twice at each dose of cocaine presented in descending order, receiving vehicle (squares) pre-treatment 15 minutes prior to one test, and CP94253 (triangles) 15 minutes before the other test, with order of presentation counterbalanced. * Represents a difference from CP94253 pre-treatment test day (Newman–Keuls, P < 0.01)

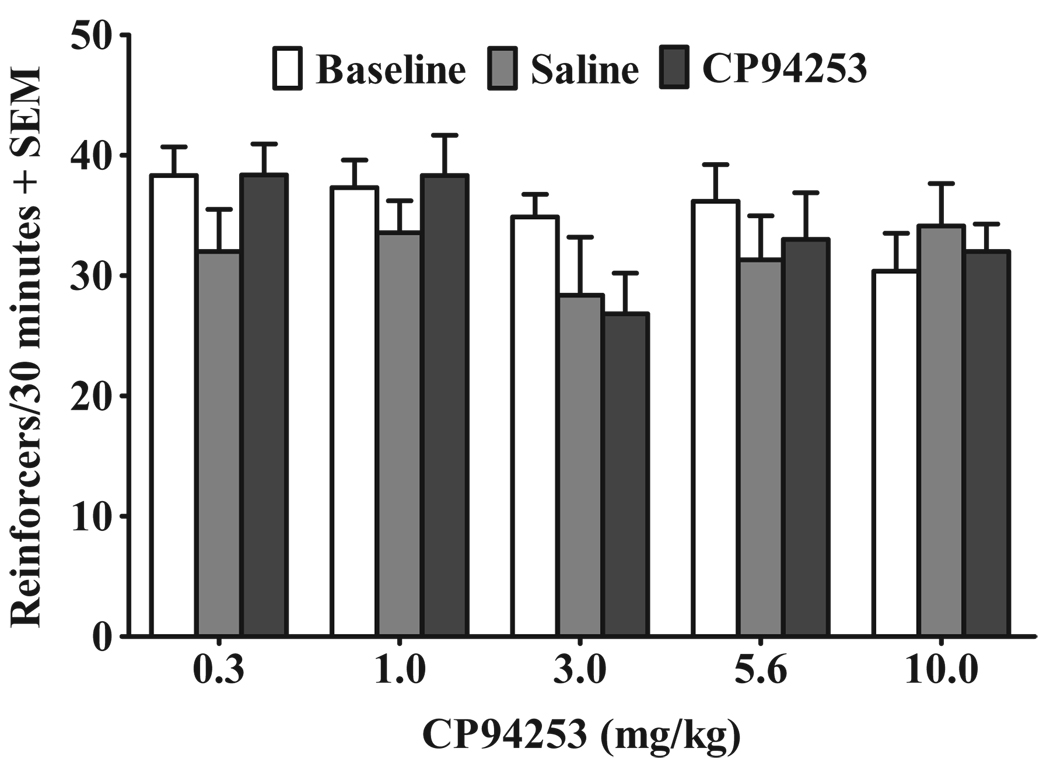

Effects of CP94253 on sucrose reinforcement

Figure 6 illustrates the effects of CP94253 on active lever responding for sucrose reinforcement. The analyses failed to demonstrate main effects or a test session by CP94253 dose interaction.

Figure 6.

Effects of CP94253 (0.3, 1.0, 3.0, 5.6 and 10 mg/kg, s.c.) on sucrose reinforcement expressed as the mean number of reinforcers during a 30-minute test session + standard error of the mean (SEM). Baselines (white bars) represent mean responses during the sessions preceding each test. Animals (n = 8–12/group) were tested twice at each dose of CP94253, receiving pre-treatment with their assigned dose of CP94253 (black bars) 15 minutes prior to one test, and saline (gray bars) 15 minutes before the other test with order of presentation counterbalanced. FR5 = fixed ratio 5

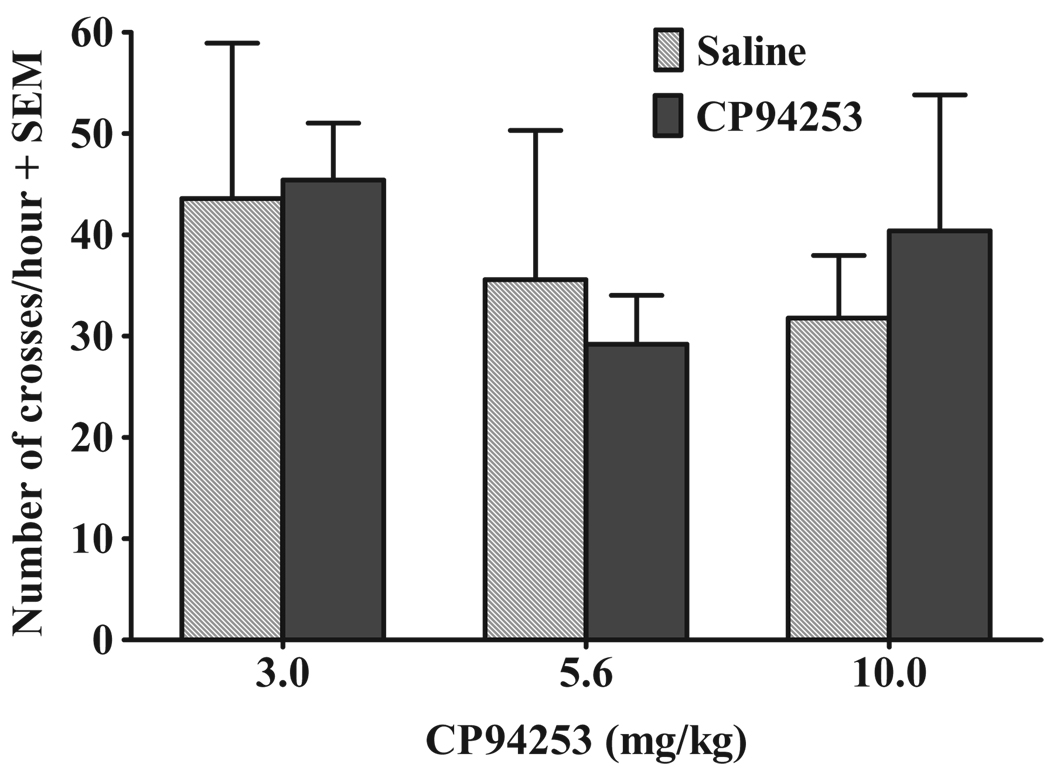

Effects of CP94253 on spontaneous locomotor activity

Figure 7 illustrates the effects of CP94253 on spontaneous locomotion. The ANOVA failed to reveal main effects or a test session by CP94253 dose interaction.

Figure 7.

Effects of CP94253 (3.0, 5.6 and 10mg/kg, s.c.) on spontaneous locomotor activity expressed as the mean number of crosses + standard error of the mean (SEM) from one side of the test chamber to the other during the 1-hour test session. Animals (n = 5/group) were tested twice on consecutive days, receiving pretreatment with their assigned dose of CP94253 (black bars) 15 minutes prior to one test, and vehicle (gray bars) 15 minutes prior to the other test with order of presentation counterbalanced

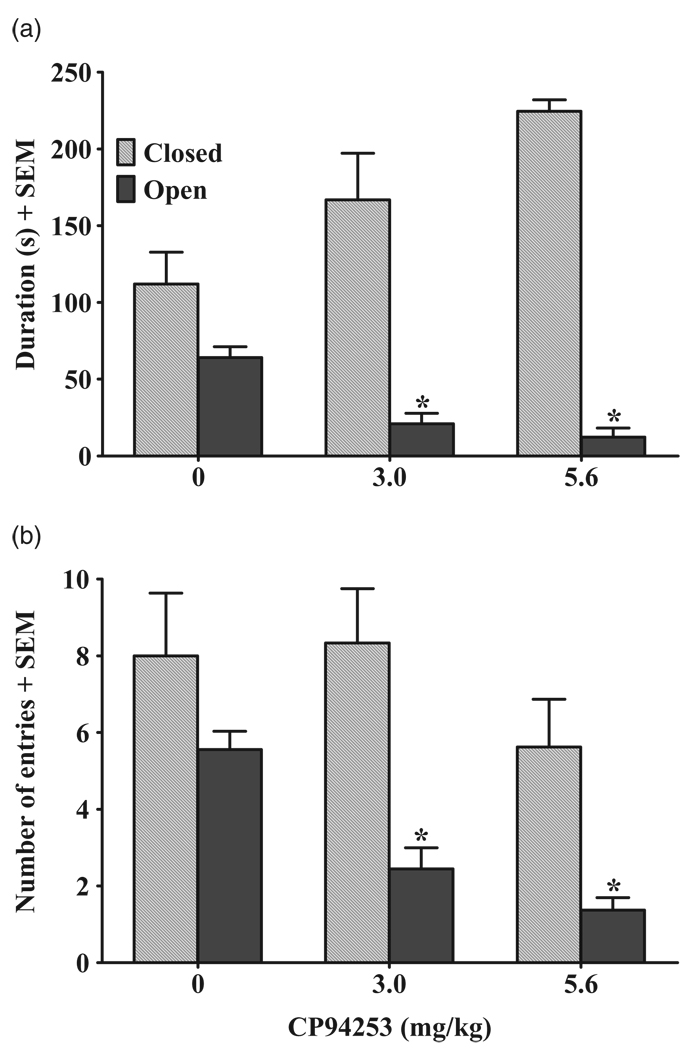

Effects of CP94253 on anxiety-like behavior in the EPM

Figure 8 illustrates the effects of CP94253 on anxiety-like behavior during the EPM test. The ANOVA indicated that CP94253 reliably decreased the duration of time spent in the open arms of the EPM [F(2, 23) = 17.2, P < 0.001], with Newman–Keuls post hoc tests revealing that both the 3 and 5.6 mg/kg groups spent less time in the open arms compared with the vehicle controls (P < 0.001); there were no differences between the two CP94253 dosage groups. The ANOVA of open-arm entries revealed a CP94253 dosage group effect [F(2,23) = 21.2, P < 0.001], with subsequent Newman– Keuls indicating that both CP94253 dosage groups exhibited fewer open-arm entries than vehicle controls (P < 0.001); there were no differences between CP94253 dosage groups.

Figure 8.

Effects of CP94253 (0.0, 3.0 and 5.6 mg/kg, s.c.) on anxiety-like behavior during the elevated plus-maze (EPM) tests expressed as the second(s) spent in (a), and number of entries into (b), the open (gray bars) and closed (black bars) arms + standard error of the mean (SEM) during a 5-minute test session. Animals (n = 9/group) were pre-treated with their assigned dose of either vehicle or CP94253 25 minutes prior to testing. * Represents a difference from vehicle controls (Newman–Keuls, P < 0.001)

DISCUSSION

The results from the present study indicate that the selective 5-HT1BR agonist, CP94253, dose-dependently attenuated cue-elicited and cocaine-primed reinstatement of extinguished cocaine-seeking behavior, similar to previous effects obtained using the non-selective 5-HT1B/1AR agonist RU24969 (Acosta et al. 2005). The results further demonstrate that the highest dose of CP94253 (10 mg/kg, s.c.) attenuated reinstatement of extinguished cocaine-seeking behavior at a low cocaine-priming dose (2.5 mg/kg, i.p.) contrary to our prediction that this selective 5-HT1BR agonist would enhance reinstatement. Paradoxically, CP94253 shifted the self-administration dose-effect function of cocaine to the left, reducing intake on the descending limb in a manner similar to increasing the unit dose of cocaine. When saline was substituted for cocaine, CP94253 again reduced response rates consistent with a decrease in motivation to seek cocaine when reinforcement is not available, as was found in the reinstatement experiments. It is unlikely that the CP94253 effects are a result of a downward shift in the self-administration dose-effect function given that the drug produced a parallel shift to the left at the cocaine doses tested. Furthermore, these results replicate and extend upon previous research that has shown that CP94253 decreases self-administration on the descending limb of the cocaine self-administration dose-effect function with low ratio schedules of reinforcement, but increases responding on a progressive ratio schedule (Parsons et al. 1998; Przegalinski et al. 2007). Moreover, CP94253 failed to alter sucrose self-administration or spontaneous locomotor activity, suggesting that 5-HT1BR activation can affect cocaine motivation and reinforcement without affecting sucrose reinforcement or general activity.

Neuroanatomically, the leftward shift in the cocaine self-administration dose-effect function produced by CP94253 could result from increased levels of dopamine in the NAc. 5-HT fibers innervate the mesocorticolimbic system (Sari 2004), modulating dopaminergic projections from the VTA to the NAc, and GABA projections from the NAc to the VTA (Yan & Yan 2001a,b; O’Dell & Parsons 2004; Yan et al. 2004). 5-HT1BRs localized on axon terminals of GABAergic neurons projecting from the NAc shell to the VTA inhibit GABA release, thereby disinhibiting dopaminergic neurons and potentiating the effects of cocaine (O’Dell & Parsons 2004; Yan et al. 2004). Indeed, viral-mediated overexpression of 5-HT1BRs in these neurons increases cocaine-induced locomotion and reward (Neumaier et al. 2002).

In light of the above findings, we hypothesized that reduced cocaine-seeking behavior produced by CP94253 following 10 mg/kg cocaine priming may have resulted from CP94253-induced satiating effects of the high cocaine-priming dose. Indeed, high cocaine-priming doses can increase response latency resulting in less reinstatement relative to lower doses (Tran-Nguyen et al. 2001). Furthermore, 5-HT1BRs are upregulated in various regions throughout the mesocorticolimbic pathway following chronic cocaine self-administration (Hoplight, Vincow & Neumaier 2007) and periods of abstinence (Przegalinski et al. 2003), which may produce sensitization to the cocaine prime. Thus, it is conceivable that under 5-HT1BR sensitized conditions, the cocaine-priming dose-effect function for reinstatement is an inverted U-shape, and that CP94253 reduced cocaine-seeking behavior at a high cocaine-priming dose (i.e. 10 mg/kg, i.p.) by increasing, rather than decreasing, cocaine-like effects on the descending part of the function. Based on this line of reasoning, we hypothesized that at a low (2.5 mg/kg) cocaine-priming dose, CP94253 would increase cocaine-seeking behavior by increasing cocaine-like effects on the ascending part of the function. In contrast to our hypothesis, CP94253 dose-dependently attenuated cocaine-primed reinstatement regardless of the cocaine-priming dose. Together with the self-administration results, our findings suggest that CP94253 produces opposite effects on cocaine reinforcement versus motivation for cocaine, suggesting a differential role of 5-HT1BRs in these processes.

An alternate explanation for the decrease in cocaine-seeking behavior is that CP94253 may produce anxiety-like behaviors that interfered with operant responding. Indeed, CP94253 decreased the duration of time spent in, and the number of entries into, the open arms of an EPM, suggesting anxiogenic-like effects (Lin & Parsons 2002). However, this explanation is somewhat mitigated by the findings that other anxiogenic events, such as foot-shock, increase rather than decrease cocaine-seeking behavior (Erb, Shaham & Stewart 1996). Nevertheless, it is still possible that specific anxiogenic states (pharmacological) and not others (footshock) will inhibit cocaine-seeking behavior, and thus, it is not clear whether the effects of CP94253 on cocaine reinforcement and motivation for cocaine are secondary to, or independent of, its anxiogenic-like effects.

A second possible explanation for the effects of CP94253 on cocaine-seeking behavior is that it may decrease motivation by producing a general satiation effect. This explanation is somewhat mitigated by previous research demonstrating that CP94253 failed to alter food reinforcement (Przegalinski et al. 2007). However, other research has shown that the 5-HT1BR agonists, RU24969 and CP94253, decrease sucrose-seeking behavior (Acosta et al. 2005) and sucrose reinforcement using a 10% solution (Lee & Simansky 1997), respectively. The present study found that CP94253 failed to alter sucrose intake at doses that significantly altered cocaine self-administration (5.6 mg/kg) and both cue-elicited and cocaine-primed reinstatement (5.6 and 10 mg/kg) of extinguished cocaine-seeking behavior. These findings suggest that the effects of CP94253 on cocaine self-administration and cocaine-seeking behavior were not because of non-specific effects on motivation/satiation.

The main strength of the present study is that the effects of CP94253 on cocaine-seeking behavior and cocaine self-administration were measured in the same laboratory under similar training conditions, thereby more firmly establishing opposite effects on reinforcement versus seeking behaviors. Nevertheless, one potential limitation to comparing results across the models is that different designs/procedures were used, resulting in different cocaine histories and abstinence periods prior to testing. Cocaine and abstinence from a cocaine regimen have been show to alter 5-HT1BR systems (Przegalinski et al. 2003; O’Dell et al. 2006; Hoplight et al. 2007), and such changes may have contributed to the differential effects of CP94253 on cocaine-related behaviors in the present study. This concern is mitigated by the fact that our results parallel those obtained by others testing the effects of CP94253 on spontaneous locomotion, (Przegalinski et al. 2007), anxiety-like behaviors (Lin & Parsons 2002), conditioned reinforcement (Fletcher & Korth 1999b), cocaine-seeking behavior (Acosta et al. 2005) and cocaine self-administration (Parsons et al. 1998), even though each of these studies involved somewhat different experimental histories and/or procedures than those used in the present study. Overall, it seems unlikely that length of cocaine history and/or abstinence accounts for the opposite effects of CP94253 across the self-administration versus extinction/reinstatement experiments.

From the above review, we favor the explanation that CP94253 produces opposite effects on cocaine self-administration and reinstatement because of opposite effects of 5-HT1BR stimulation on the mechanisms involved in reinforcement versus motivation. Consistent with this idea, previous research has shown dissociable effects of manipulations on cocaine reinforcement versus cocaine-seeking behavior. For instance, selective dopamine D3 antagonists decrease reinstatement of extinguished cocaine-seeking behavior elicited by either cocaine-associated cues or cocaine-priming injections (Vorel et al. 2002; Di Ciano et al. 2003), but have inconsistent effects on cocaine self-administration (Campiani et al. 2003; Di Ciano et al. 2003; Gal & Gyertyan 2003). Furthermore, opposing effects have been obtained with 5-HT1BR agonists using ICSS and cocaine self-administration models (Harrison et al. 1999). RU24969, a 5-HT1A/1BR agonist, elevates ICSS thresholds, results indicative of a reduction in the value of brain-stimulation reward (Markou & Koob 1991) or decreased motivation. In contrast, cocaine reduces ICSS thresholds, results indicative of cocaine enhancement of the value of the rewarding stimuli or increased motivation. RU24969 dose-dependently attenuated the effect of cocaine on ICSS behavior, an effect attributed to two opposing drug effects canceling each other out, rather than an interactive effect of the two drugs. Collectively, these findings suggest different neural mechanisms underlie motivation during tests for reinstatement of extinguished cocaine-seeking behavior and reinforcement during tests for self-administered cocaine.

Future studies are needed to examine the neural circuits underlying the role of 5-HT1BRs in cocaine self-administration and reinstatement of extinguished cocaine-seeking behavior as different pathways are likely involved in these effects. Furthermore, in addition to postsynaptic effects, 5-HT1BRs can function presynaptically as terminal autoreceptors or heteroreceptors, decreasing 5-HT or dopamine neurotransmission (Barnes & Sharp 1999). Elucidating the neural circuitry involved in the effects of 5-HT1BR agonists may aid in developing pharmacological treatments for cocaine dependence. Indeed, it is possible these agonists may decrease incentive motivational effects of cocaine and cocaine cues, and decrease cocaine intake if relapse occurs.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank Felicia Duke, Arturo Zavala, Kenneth Thiel, Peter Kufahl and Lyn Gaudet for their expert assistance. Also, the authors would like to thank NIDA (DA11064), Ford Foundation and the APA Diversity Program in Neuroscience.

References

- Acosta JI, Boynton FA, Kirschner KF, Neisewander JL. Stimulation of 5-HT1B receptors decreases cocaine- and sucrose-seeking behavior. Pharmacol Biochem Behav. 2005;80:297–307. doi: 10.1016/j.pbb.2004.12.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Acosta JI, Thiel KJ, Sanabria F, Browning JR, Neisewander JL. Effect of schedule of reinforcement on cue-elicited reinstatement of cocaine-seeking behavior. Behav Pharmacol. 2008;19:129–136. doi: 10.1097/FBP.0b013e3282f62c89. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aronson SC, Black JE, McDougle CJ, Scanley BE, Jatlow P, Kosten TR, Heninger GR, Price LH. Serotonergic mechanisms of cocaine effects in humans. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 1995;119:179–185. doi: 10.1007/BF02246159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baker DA, Tran-Nguyen TL, Fuchs RA, Neisewander JL. Influence of individual differences and chronic fluoxetine treatment on cocaine-seeking behavior in rats. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 2001;155:18–26. doi: 10.1007/s002130000676. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barnes NM, Sharp T. A review of central 5-HT receptors and their function. Neuropharmacology. 1999;38:1083–1152. doi: 10.1016/s0028-3908(99)00010-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Belzung C, Scearce-Levie K, Barreau S, Hen R. Absence of cocaine-induced place conditioning in serotonin 1B receptor knock-out mice. Pharmacol Biochem Behav. 2000;66:221–225. doi: 10.1016/s0091-3057(00)00238-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burmeister JJ, Lungren EM, Kirschner KF, Neisewander JL. Differential roles of 5-HT receptor subtypes in cue and cocaine reinstatement of cocaine-seeking behavior in rats. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2004;29:660–668. doi: 10.1038/sj.npp.1300346. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burmeister JJ, Lungren EM, Neisewander JL. Effects of fluoxetine and d-fenfluramine on cocaine-seeking behavior in rats. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 2003;168:146–154. doi: 10.1007/s00213-002-1307-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Callahan PM, Cunningham KA. Modulation of the discriminative stimulus properties of cocaine by 5-HT1B and 5-HT2C receptors. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 1995;274:1414–1424. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Callahan PM, Cunningham KA. Modulation of the discriminative stimulus properties of cocaine: comparison of the effects of fluoxetine with 5-HT1A and 5-HT1B receptor agonists. Neuropharmacology. 1997;36:373–381. doi: 10.1016/s0028-3908(97)00010-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Campiani G, Butini S, Trotta F, Fattorusso C, Catalanotti B, Aiello F, Gemma S, Nacci V, Novellino E, Stark JA, Cagnotto A, Fumagalli E, Carnovali F, Cervo L, Mennini T. Synthesis and pharmacological evaluation of potent and highly selective D3 receptor ligands: inhibition of cocaine-seeking behavior and the role of dopamine D3/D2 receptors. J Med Chem. 2003;46:3822–3839. doi: 10.1021/jm0211220. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carroll ME, France CP, Meisch RA. Intravenous self-administration of etonitazene, cocaine and phencyclidine in rats during food deprivation and satiation. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 1981;217:241–247. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carroll ME, Lac ST, Asencio M, Kragh R. Fluoxetine reduces intravenous cocaine self-administration in rats. Pharmacol Biochem Behav. 1990;35:237–244. doi: 10.1016/0091-3057(90)90232-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Castanon N, Scearce-Levie K, Lucas JJ, Rocha B, Hen R. Modulation of the effects of cocaine by 5-HT1B receptors: a comparison of knockouts and antagonists. Pharmacol Biochem Behav. 2000;67:559–566. doi: 10.1016/s0091-3057(00)00389-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cervo L, Rozio M, Ekalle-Soppo CB, Carnovali F, Santangelo E, Samanin R. Stimulation of serotonin1B receptors induces conditioned place aversion and facilitates cocaine place conditioning in rats. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 2002;163:142–150. doi: 10.1007/s00213-002-1145-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cunningham KA, Paris JM, Goeders NE. Chronic cocaine enhances serotonin autoregulation and serotonin uptake binding. Synapse. 1992;11:112–123. doi: 10.1002/syn.890110204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Darmani NA, Martin BR, Glennon RA. Repeated administration of low doses of cocaine enhances the sensitivity of 5-HT2 receptor function. Pharmacol Biochem Behav. 1992;41:519–527. doi: 10.1016/0091-3057(92)90367-o. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Di Ciano P, Underwood RJ, Hagan JJ, Everitt BJ. Attenuation of cue-controlled cocaine-seeking by a selective D3 dopamine receptor antagonist SB-277011-A. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2003;28:329–338. doi: 10.1038/sj.npp.1300148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ehrman RN, Robbins SJ, Childress AR, O’Brien CP. Conditioned responses to cocaine-related stimuli in cocaine abuse patients. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 1992;107:523–529. doi: 10.1007/BF02245266. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Erb S, Shaham Y, Stewart J. Stress reinstates cocaine-seeking behavior after prolonged extinction and a drug-free period. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 1996;128:408–412. doi: 10.1007/s002130050150. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Filip M, Frankowska M, Zaniewska M, Golda A, Przegalinski E. The serotonergic system and its role in cocaine addiction. Pharmacol Rep. 2005;57:685–700. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Filip M, Nowak E, Papla I, Przegalinski E. Role of 5-hydroxytryptamine1B receptors and 5-hydroxytryptamine uptake inhibition in the cocaine-evoked discriminative stimulus effects in rats. J Physiol Pharmacol. 2001;52:249–263. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fletcher PJ, Korth KM. Activation of 5-HT1B receptors in the nucleus accumbens reduces amphetamine-induced enhancement of responding for conditioned reward. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 1999a;142:165–174. doi: 10.1007/s002130050876. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fletcher PJ, Korth KM. RU-24969 disrupts d-amphetamine self-administration and responding for conditioned reward via stimulation of 5-HT1B receptors. Behav Pharmacol. 1999b;10:183–193. doi: 10.1097/00008877-199903000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fletcher PJ, Azampanah A, Korth KM. Activation of 5-HT(1B) receptors in the nucleus accumbens reduces self-administration of amphetamine on a progressive ratio schedule. Pharmacol Biochem Behav. 2002;71:717–725. doi: 10.1016/s0091-3057(01)00717-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gal K, Gyertyan I. Targeting the dopamine D3 receptor cannot influence continuous reinforcement cocaine self-administration in rats. Brain Res Bull. 2003;61:595–601. doi: 10.1016/s0361-9230(03)00217-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harrison AA, Parsons LH, Koob GF, Markou A. RU 24969, a 5-HT1A/1B agonist, elevates brain stimulation reward thresholds: an effect reversed by GR 127935, a 5-HT1B/1D antagonist. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 1999;141:242–250. doi: 10.1007/s002130050831. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoplight BJ, Vincow ES, Neumaier JF. Cocaine increases 5-HT1B mRNA in rat nucleus accumbens shell neurons. Neuropharmacology. 2007;52:444–449. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropharm.2006.08.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koe BK. Molecular geometry of inhibitors of the uptake of catecholamines and serotonin in synaptosomal preparations of rat brain. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 1976;199:649–661. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee MD, Simansky KJ. CP-94,253: a selective serotonin(1B) (5-HT1B) agonist that promotes satiety. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 1997;131:264–270. doi: 10.1007/s002130050292. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leshner AI, Koob GF. Drugs of abuse and the brain. Proc Assoc Am Physicians. 1999;111:99–108. doi: 10.1046/j.1525-1381.1999.09218.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li MY, Yan QS, Coffey LL, Reith ME. Extracellular dopamine, norepinephrine, and serotonin in the nucleus accumbens of freely moving rats during intracerebral dialysis with cocaine and other monoamine uptake blockers. J Neurochem. 1996;66:559–568. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.1996.66020559.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin D, Parsons LH. Anxiogenic-like effect of serotonin(1B) receptor stimulation in the rat elevated plus-maze. Pharmacol Biochem Behav. 2002;71:581–587. doi: 10.1016/s0091-3057(01)00712-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Markou A, Koob GF. Postcocaine anhedonia. An animal model of cocaine withdrawal. Neuropsychopharmacology. 1991;4:17–26. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morikawa H, Manzoni OJ, Crabbe JC, Williams JT. Regulation of central synaptic transmission by 5-HT(1B) auto- and heteroreceptors. Mol Pharmacol. 2000;58:1271–1278. doi: 10.1124/mol.58.6.1271. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muller CP, Carey RJ, Huston JP, De Souza Silva MA. Serotonin and psychostimulant addiction: focus on 5-HT1A-receptors. Prog Neurobiol. 2007;81:133–178. doi: 10.1016/j.pneurobio.2007.01.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- National Research Council. Guide for the care and use of laboratory animals. Washington D.C: National Academy Press; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Neisewander JL, Baker DA, Fuchs RA, Tran-Nguyen LT, Marshall JF. Fos protein expression and cocaine-seeking behavior in rats after exposure to a cocaine self-administration environment. J Neurosci. 2000;20:798–805. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.20-02-00798.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neumaier JF, Vincow ES, Arvanitogiannis A, Wise RA, Carlezon WA., Jr. Elevated expression of 5-HT1B receptors in nucleus accumbens efferents sensitizes animals to cocaine. J Neurosci. 2002;22:10856–10863. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.22-24-10856.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O'Dell LE, Parsons LH. Serotonin 1B receptors in the ventral tegmental area modulate cocaine-induced increases in nucleus accumbens dopamine levels. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2004;311:711–719. doi: 10.1124/jpet.104.069278. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O'Dell LE, Manzardo AM, Polis I, Stouffer DG, Parsons LH. Biphasic alterations in serotonin-1B (5-HT1B) receptor function during abstinence from extended cocaine self-administration. J Neurochem. 2006;99:1363–1376. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2006.04163.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parsons LH, Weiss F, Koob GF. Serotonin1B receptor stimulation enhances cocaine reinforcement. J Neurosci. 1998;18:10078–10089. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.18-23-10078.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peltier R, Schenk S. Effects of serotonergic manipulations on cocaine self-administration in rats. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 1993;110:390–394. doi: 10.1007/BF02244643. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Przegalinski E, Czepiel K, Nowak E, Dlaboga D, Filip M. Withdrawal from chronic cocaine up-regulates 5-HT1B receptors in the rat brain. Neurosci Lett. 2003;351:169–172. doi: 10.1016/j.neulet.2003.08.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Przegalinski E, Golda A, Frankowska M, Zaniewska M, Filip M. Effects of serotonin 5-HT1B receptor ligands on the cocaine- and food-maintained self-administration in rats. Eur J Pharmacol. 2007;559:165–172. doi: 10.1016/j.ejphar.2006.12.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Richardson NR, Roberts DC. Fluoxetine pretreatment reduces breaking points on a progressive ratio schedule reinforced by intravenous cocaine self-administration in the rat. Life Sci. 1991;49:833–840. doi: 10.1016/0024-3205(91)90248-a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rocha BA, Scearce-Levie K, Lucas JJ, Hiroi N, Castanon N, Crabbe JC, Nestler EJ, Hen R. Increased vulnerability to cocaine in mice lacking the serotonin-1B receptor. Nature. 1998;393:175–178. doi: 10.1038/30259. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sari Y. Serotonin1B receptors: from protein to physiological function and behavior. Neurosci Biobehav Rev. 2004;28:565–582. doi: 10.1016/j.neubiorev.2004.08.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Satel SL, Krystal JH, Delgado PL, Kosten TR, Charney DS. Tryptophan depletion and attenuation of cue-induced craving for cocaine. Am J Psychiatry. 1995;152:778–783. doi: 10.1176/ajp.152.5.778. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tran-Nguyen LT, Baker DA, Grote KA, Solano J, Neisewander JL. Serotonin depletion attenuates cocaine-seeking behavior in rats. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 1999;146:60–66. doi: 10.1007/s002130051088. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tran-Nguyen LT, Bellew JG, Grote KA, Neisewander JL. Serotonin depletion attenuates cocaine seeking but enhances sucrose seeking and the effects of cocaine priming on reinstatement of cocaine seeking in rats. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 2001;157:340–348. doi: 10.1007/s002130100822. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vorel SR, Ashby CR, Jr, Paul M, Liu X, Hayes R, Hagan JJ, Middle-miss DN, Stemp G, Gardner EL. Dopamine D3 receptor antagonism inhibits cocaine-seeking and cocaine-enhanced brain reward in rats. J Neurosci. 2002;22:9595–9603. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.22-21-09595.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walsh SL, Cunningham KA. Serotonergic mechanisms involved in the discriminative stimulus, reinforcing and subjective effects of cocaine. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 1997;130:41–58. doi: 10.1007/s002130050210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Wit H, Stewart J. Reinstatement of cocaine-reinforced responding in the rat. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 1981;75:134–143. doi: 10.1007/BF00432175. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yan QS, Yan SE. Activation of 5-HT(1B/1D) receptors in the mesolimbic dopamine system increases dopamine release from the nucleus accumbens: a microdialysis study. Eur J Pharmacol. 2001a;418:55–64. doi: 10.1016/s0014-2999(01)00913-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yan QS, Yan SE. Serotonin-1B receptor-mediated inhibition of [(3)H]GABA release from rat ventral tegmental area slices. J Neurochem. 2001b;79:914–922. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.2001.00643.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yan QS, Zheng SZ, Yan SE. Involvement of 5-HT1B receptors within the ventral tegmental area in regulation of mesolimbic dopaminergic neuronal activity via GABA mechanisms: a study with dual-probe microdialysis. Brain Res. 2004;1021:82–91. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2004.06.053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]