Abstract

Smoking is thought to produce immediate reinforcement, and subjective satisfaction with smoking is thought to influence subsequent smoking. We used Ecological Momentary Assessment to assess cigarette-by-cigarette smoking satisfaction in 394 heavy smokers who subsequently attempted to quit. Across 14,882 cigarettes rated, satisfaction averaged 7.06 (0-10 scale), but with considerable variation across cigarettes and individuals. Women and African American smokers reported higher satisfaction. More satisfied smokers were more likely to lapse after quitting (HR=1.1, p<0.03), whereas less satisfied smokers derived greater benefit from patch treatment to help them achieve abstinence (HR=1.23, p<.001). Cigarettes smoked in positive moods more satisfying, correcting for mood at the time of rating. The best predictor of subsequent smoking satisfaction was the intensity of craving prior to smoking. Understanding subjective smoking satisfaction provides insight into sources of reinforcement for smoking.

Keywords: Smoking, reinforcement, satisfaction, craving affect

At the root of most analyses of drug use and dependence is the principle that use of the drug is reinforcing (Shadel, Shiffman, Niaura, Nichter & Abrams, 2000; Glautier, 2004; Eissenberg, 2004; Brandon, Herzog & Irvin, 2004). While drug-use reinforcement does not necessarily depend on subjective hedonic responses to drug ingestion (White & Milner, 1992; Robinson & Berridge, 2003), subjective drug effects are often considered important reinforcers in themselves or at least an important “read-out” of the neurobiological systems that underlie behavioral reinforcement (Stefano et al., 2007). The fact that drugs such as cocaine and heroin induce immediate euphoric “highs” is often thought to be part of their appeal (Wise, 1996).

In this respect, tobacco smoking and nicotine use are striking contrasts, because their subjective effects appear to be relatively mild, especially in comparison to their addictive potential (Hughes, Higgins, & Bickel, 1994). While some studies (e.g., Pomerleau & Pomerleau, 1992) have suggested that smoking produces euphoria (a feeling of well-being and elation), others (e.g., Dar, Kaplan, Shahan & Frenk, 2007) have disputed this conclusion.

Whether or not it produces euphoria (which, in any case, can be difficult to define), subjective responses to smoking appear to be important indicators, if not causes, of the hold of smoking on the smoker. This is highlighted by findings that, at key turning points in individuals’ smoking history – the first cigarette (Pomerleau, Pomerleau, & Namenek, 1998; Eissenberg & Balster, 2000) and the first lapse after cessation (Shiffman et al., 2006) – smokers who experience more subjective pleasure and satisfaction are more likely to progress to further smoking. Other studies of cessation suggest that interventions that diminish subjective responses to smoking promote and predict abstinence (Rose, Behm, Westman, & Kukovich, 2006). Pharmacological treatments that reduce satisfaction with smoking may help people in part by reducing the tendency to progress to complete relapse after an initial lapse (Foulds, 2006). These findings seem to confirm the idea that subjective responses may be important for maintaining smoking, either in themselves or as read-outs of underlying processes related to reinforcement.

Laboratory studies of smoking satisfaction demonstrate that individual cigarette puffs are subjectively experienced as pleasurable (Rose, 1984; Herskovic, Rose & Jarvik, 1986; Pomerleau & Pomerleau, 1992, 1994; Baldinger, Hasenfratz & Battig, 1995). There is considerable evidence that this is due in part to the direct effects of nicotine on reward systems in the brain (Pontieri, Tanda, Orzi & DiChiara, 1996; Koob & Nestler, 1997). Additionally, there is evidence that satisfaction is related to airway sensory stimulation (Rose, Behm, Westman, & Johnson, 2000; Perkins 2008) and to other smoking stimuli that are conditioned with repeated exposure (Caggiula et al., 2002; Rose et al., 2000).

While a simple reinforcement model suggests that positive hedonic responses to smoking are important in maintaining smoking, alternative theoretical perspectives suggest otherwise. Most notably, Robinson and Berridge (1993; 2003) have suggested that, as addiction develops, subjective “liking” (i.e., positive hedonic responses to use) diminishes with time, and becomes less and less important, and de-coupled from “wanting” (craving), which they believe drives persistent use and dependence. Implicit motivational systems may also promote drug-seeking outside of conscious awareness (Baker, Piper, McCarthy, Majeskie & Fiore, 2004; Miller & Gold, 1994). On this model, subjective hedonic responses would be expected to be modest, and, in well-established smokers, unrelated to craving (an index of “wanting”).

Most studies of subjective satisfaction with smoking have either relied upon global retrospective summaries of smoking satisfaction (Nemeth-Coslett, Henningfield, O’Keeffe, & Griffiths, 1987) or have studied responses to smoking in the laboratory (Rose, 1984; Herskovic et al., 1986; Pomerleau & Pomerleau, 1992, 1994; Baldinger et al., 1995), which may not represent real-world experience, particularly as the stimulus context in the laboratory is unlikely to mirror that in the natural environment. The present study analyzes subjective responses to each cigarette during ad libitum smoking in the natural environment.

We begin with descriptive data to answer basic questions about hedonic responses to ad libitum smoking. How satisfying are cigarettes smoked during ad libitum smoking? What proportion is highly satisfying? What proportion is not satisfying at all? Even if one considers that cigarettes are smoked to replenish dropping nicotine levels, and are reinforced by the effects of restoring nicotine levels, the boundary model (Kozlowski & Herman, 1984) suggests that some cigarettes are smoked even when they are not needed, and so might be less reinforcing. We also examine individual differences in average satisfaction, and how they relate to other individual differences in smoking. For example, higher nicotine dependence could lead to decreased satisfaction, due to greater tolerance to the effects of nicotine (Peper, 2004; Soloman, 1980) or to increased automaticity in smoking (Tiffany, 1990). Conversely, higher levels of dependence might lead to increased satisfaction, as cigarettes are smoked in response to intense cravings and are more “needed.” Gender night also effect satisfaction: women have been said to find nicotine less reinforcing (Benowitz & Hatsukami, 1998; Perkins, Jacobs, Sanders & Caggiula, 2002). Individual differences in satisfaction could in turn affect cessation otcomes: more satisfied smokers might have greater difficulty quitting and staying quit, because they value and miss cigarettes more.

We also examine how satisfaction varies across individual cigarettes smoked by each smoker. For example, we assessed whether satisfaction declined as the smoking day progresses: As more cigarettes are smoked, those later in the sequence have much smaller impact on blood nicotine levels, given that they are smoked against a background of already-substantial nicotine levels (Benowitz, Zevin, & Jacob, 1997). Moreover, as more cigarettes are smoked, acute tolerance and desensitization of nicotine receptors should cause the impact of smoking to diminish over successive cigarettes (Porchet, Benowitz & Sheiner, 1987). Indeed, in a laboratory setting, Fant, Schuh & Stitzer (1995) reported that satisfaction declined as more cigarettes were smoked over a 6-hour period. It’s also been suggested that the first cigarette of the day might be particularly impactful and particularly reinforcing, given that it ends a prolonged period of overnight deprivation (Perkins et al, 1994). This effect is also thought to be moderated by individual differences, and smokers who most value the first cigarette of the day are thought to be more dependent (Heatherton, Kozlowski, Frecker, Rickert & Robinson, 1989).

Observing which cigarettes are most satisfying could give insight into sources of smoking reinforcement. For example, it has been proposed that one mechanism by which smoking provides reinforcement is by relieving negative affect (Baker, Piper, et al., 2004; Kassel, Stroud, & Paronis, 2003). Accordingly, one might expect cigarettes smoked under conditions of emotional distress to be experienced as more satisfying. Conversely, it has been suggested that nicotine may enhance reinforcement derived from other mild reinforcers (Caggiula et al., 2002), so one might also expect cigarettes smoked under positive affect to be particularly satisfying. Unlike affective states, whose association with smoking has been difficult to demonstrate (Shiffman et al, 2002), a number of situational variables, such as eating, drinking alcohol or coffee, being with others who are smoking, have been shown to increase smoking (Shiffman et al, 2002), and might also be associated with smoking satisfaction, perhaps because the reinforcing properties of such activities are enhanced by nicotine (Caggiula et al, 2002). Alcohol consumption in particular has been strongly linked to smoking (Shiffman & Balabanis, 1995) and has been shown to increase smoking satisfaction and reinforcement expectancies in laboratory settings (Kirchner & Sayette, 2007; Rose et al, 2002; Glautier, Clements, White, Taylor & Stolerman, 1996). We examine these relationships in real-world settings.

Cigarettes also vary in how strongly they are craved (Dunbar, Scharf, Shiffman & Kirchner, 2008): some cigarettes are smoked when craving is quite low, whereas others seem to be associated with and perhaps cued by intense craving (Shiffman et al, 2002). There are at least two reasons why cigarettes preceded by more intense craving would be expected to be more satisfying. First, craving may be a final common pathway for various processes that motivate smoking, and therefore a useful indicator of how much each cigarette is “needed.” Second, craving has itself been conceptualized as a drive state whose relief would be reinforcing. These considerations would lead one to expect that cigarettes smoked under high craving states would be experienced as more satisfying. On the other hand, Robinson & Berridge (1993; 2003) have asserted that craving (“wanting”) increases with use, even as satisfaction (“liking”) declines, making them two distinct processes and thus likely to be unrelated or even negatively correlated.

In summary, in this paper, we examine subjective self-reports of satisfaction during ad libitum smoking in the natural environment. Using the methods of ecological momentary assessment (EMA, Stone & Shiffman, 1994), smokers used palmtop computers to record every cigarette they smoked, providing details of the circumstances for a randomly-selected sample of cigarettes. The electronic diaries also conducted random time-sampling, prompting smokers for assessment at randomly-selected times when not smoking (“time-sampled assessments”), at which time smokers rated how pleasant and satisfying the previous cigarette had been. These data were used to assess average smoking satisfaction, individual differences in satisfaction, and situational influences on satisfaction.

Methods

Participants

Participants were 394 adult men and women between the ages of 21 and 65 years (M = 39.3, SD = 9.6) recruited through local media advertisements for a research cessation program. To qualify, participants had to meet the following criteria: smoking ≥15 cigarettes per day for ≥ 5 years, but no use of other forms of tobacco, and high motivation and confidence to quit smoking. Participants had to report good health, pass a physical examination, and be free of conditions that would make them poor candidates for high-dose nicotine patch treatment (see Shiffman et al, 2006, for details). Subjects who qualified and were interested signed a consent form. The study was approved by the University of Pittsburgh Internal Review Board.

Of the 394 participants, 194 (49.2%) were men and 200 (50.8%) were women; 332 (84.5%) were Caucasian and 46 (11.7%) were African-American (Table 1). A total of 46.9% smoked menthol cigarettes; this was higher among African-American smokers (90.2%) than others (41.1%). Mean age was 39.4 years (Table 1; SD = 9.4). Participants smoked an average of 23.7 (SD = 8.7) cigarettes per day and had smoked, on average, for 21.9 (SD = 9.5) years. At baseline, mean exhaled carbon monoxide (CO) reading was 37.5 ppm (SD = 14.4), mean Fagerstrom Test for Nicotine Dependence (FTND; (Heatherton, Kozlowski, Frecker, & Fagerstrom, 1991) score was 5.9 (SD = 2.0), and mean Nicotine Dependence Syndrome Scale (NDSS; Shiffman, Waters, & Hickcox, 2004) score was −0.06 (SD = 0.88). Data were collected between 1995 and 2000 in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania. During this time, state law prohibited smoking in government and large private work sites, but not in restaurants, or other public sites (Shelton et al., 1995). Clinical outcomes from this study are reported elsewhere (Shiffman et al., 2006).

Table 1.

Sample Characteristics and Mean Satisfaction

| Sample Characteristics |

Satisfaction Ratings | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variable | N | % | Mean † | SD (within) | SD (between) |

| Male | 194 | 49.2 | 6.7 | 1.2 | 1.7 |

| Female | 200 | 50.8 | *7.4 | 1.2 | 1.7 |

| Age: 20 ≥ 29 | 73 | 18.5 | 7.3 | 1.2 | 1.7 |

| Age: 30 ≥ 39 | 129 | 32.7 | 7.1 | 1.3 | 1.7 |

| Age: 40 ≥ 49 | 138 | 35.0 | 7.0 | 1.2 | 1.8 |

| Age : ≥ 50 | 54 | 13.7 | 7.1 | 1.1 | 1.8 |

| African-American | 46 | 11.7 | *7.8 | 1.4 | 1.8 |

| Caucasian | 332 | 84.5 | 6.9 | 1.2 | 1.7 |

| Other Ethnicity | 15 | 2.0 | 7.1 | 1.1 | 1.0 |

| Single | 105 | 26.7 | 7.1 | 1.3 | 1.8 |

| Married | 190 | 48.4 | 7.0 | 1.1 | 1.7 |

| No longer Married | 98 | 24.9 | 7.1 | 1.2 | 1.8 |

| HS Education | 136 | 34.9 | *7.4 | 1.2 | 1.9 |

| College Education | 254 | 65.1 | 6.9 | 1.2 | 1.6 |

| Smoke years: < 10 | 42 | 10.7 | 7.2 | 1.1 | 1.5 |

| Smoke years: 10 ≥ 19 | 111 | 28.2 | 7.2 | 1.2 | 1.9 |

| Smoke years: 20 ≥ 29 | 147 | 37.4 | 6.9 | 1.2 | 1.8 |

| Smoke years: 30 ≥ 39 | 71 | 18.1 | 7.0 | 1.1 | 1.5 |

| Smoke years: > 40 | 22 | 5.6 | 7.4 | 1.2 | 1.7 |

| Previous Attempt | 311 | 79.7 | 7.0 | 1.2 | 1.6 |

| No Prev Attempt | 79 | 20.3 | 7.1 | 1.2 | 1.8 |

| Motivation (Max=10) | 253 | 64.4 | 7.1 | 1.2 | 1.9 |

| Motivation (0-9) | 140 | 35.6 | 6.9 | 1.1 | 1.5 |

| CPD ≤ 15 | 95 | 24.2 | *7.3 | 1.2 | 1.8 |

| CPD 16 ≥ 25 | 145 | 36.9 | *7.3 | 1.1 | 1.5 |

| CPD 26 ≥ 35 | 93 | 23.7 | 6.7 | 1.3 | 1.7 |

| CPD 36 ≥ 45 | 50 | 12.7 | 6.5 | 1.2 | 1.9 |

| CPD > 45 | 10 | 2.5 | **7.5 | 1.0 | 1.8 |

| FTND (0-2) | 15 | 4.5 | 6.7 | 1.5 | 1.7 |

| FTND (3-5) | 123 | 36.5 | 7.3 | 1.1 | 1.8 |

| FTND (6-7) | 120 | 35.6 | 7.2 | 1.2 | 1.6 |

| FTND (8-10) | 79 | 23.4 | 6.5 | 1.2 | 1.9 |

| NDSS –Total (≤ −1) | 54 | 13.7 | 6.9 | 1.3 | 2.0 |

| NDSS –Total (−1 ≥ 0) | 156 | 39.7 | 7.0 | 1.1 | 1.8 |

| NDSS –Total (0 ≥ 1) | 133 | 33.8 | 7.1 | 1.2 | 1.6 |

| NDSS –Total (≥ 1) | 50 | 12.7 | 7.2 | 1.2 | 1.7 |

Note. p<.05

p<.01 Significance tests indicated here contrasted each category versus the others, wheras analyses reported in the text treated continuous variables (age, years smoking, motivation, CPD, FTND and NDSS) as such. Mean values correspond to regression coefficients obtained from univariate multi-level models on each sample characteristic.

Procedure

Participants reported their age, number of years of education, gender, ethnicity, and smoking rate, completed the FTND and NDSS, and provided breath samples for CO assay. Participants were instructed in how to use the electronic diary (ED). They used the ED for 16 days leading up to a target quit date. During this time, participants were instructed to continue smoking ad libitum without changing their smoking frequency or pattern. On Day 9 of monitoring, participants were instructed to abstain from smoking until noon, as described in Shiffman, Ferguson, Gwaltney, Balabanis, and Shadel, (2006). To avoid interference, we omitted data from Day 9. We also dropped the first two days, which we considered a period of acclimation to the procedures, and the last two days before the target quit date, when the impending quit might especially affect ratings. Thus, 11 days of data were eligible for inclusion, but some subjects had fewer days because they dropped out early.

During the period of monitoring, participants were directed to use the ED to record each cigarette smoked before smoking it. Records of smoking were automatically time and date-stamped by the ED. A randomly-selected subset of cigarette recordings (about 5/day) were followed by detailed assessments, completed on-screen, one item at a time. Craving was measured with a single 0- to 10-point item (Shiffman et al., 1997). Mood ratings on a 0–10 scale were made for adjectives derived from the circumplex model of affect (Russell 1980), as well as items relevant to nicotine withdrawal. Responses were used to form Positive Affect (items: happy, content, calm; Cronbach α=0.80) and Negative Affect (frustrated, irritable, miserable, sad, worried; α=0.85) scores. Participants also reported whether they had consumed food, alcohol, or coffee in the preceding 15 minutes, whether others were smoking in their presence, what activity they were engaged in, whether they were in a setting that permitted, discouraged, or forbade smoking, and whether they had changed locations in order to smoke. These assessments have been used before to study situational contexts of smoking and relapse (Shiffman et al, 2002; Shiffman, Paty, Gwaltney & Dang, 2004; Shiffman et al, 1996).

To collect time-sampling assessments, the ED also audibly prompted (“beeped”) participants four to five times daily at random times, with the constraint that no prompts were issued for 10 min after a cigarette entry. Participants had two minutes to respond, and did so for >90% of prompts. At this time, ED administered an assessment paralleling that described for smoking records. Additionally, ED asked participants to rate the cigarette they had most recently smoked as to whether it was pleasant and satisfying (each 0-10, with the extremes marked as signifying “NO!!” and YES!!”). The ED record of wake times also helped identify the first cigarette of the day. ED hardware consisted of a PalmPilot Professional palmtop computer (Version 2.0; 3Com Corporation; 7.9 cm × 12.2 cm × 1.3 cm, 5.7 oz), with the touch screen LCD used to present questions and solicit responses. Software for the study was developed specifically for this purpose (invivodata, Pittsburgh, PA).

Clinical treatment

After the baseline period, participants were randomized in a double-blind fashion to treatment with either 35 mg transdermal nicotine or matched placebo, as described in Shiffman et al (2006). Patch condition was treated as a covariate and moderator in analyses of outcomes. Participants got two sessions of cognitive-behavioral treatment during baseline, and five sessions subsequently.

Data processing

We collected qualifying satisfaction ratings during 14,882 time-sampling assessments, which were used to characterize satisfaction and individual differences in satisfaction. In a subset of 4,997 of these occasions, the immediately-preceding cigarette – the referent of the satisfaction ratings – had been assessed for situational context (having been randomly selected). This allowed us to assess how subsequent satisfaction ratings were related to conditions at the time of smoking. Additionally, we analyzed how participants’ condition at the time they made the satisfaction ratings (i.e., at time-sampling assessments) influenced their ratings.

Data analysis

Because the focus of analysis is on many repeated observations clustered within participants, we used mixed-effect regression models to examine participants’ satisfaction ratings. These models account for multiple (and varied numbers of) observations across subjects and can examine both within- and between-subject variables and their interactions. They consider two levels of data: variation among individual observations (smoking episodes) and variation among individuals. Importantly, when examining predictor variables that varied from cigarette-to-cigarette, we included each participant’s average response value as a between-subject covariate in order to further differentiate within- from between-subject effects (Begg & Parides, 2003).

We first estimated the extent to which variation in cigarette satisfaction was due to between-subject differences, and then sought to identify individual difference factors that could account for these differences. Next, we examined individual observations of particular cigarettes, assessing whether satisfaction was related to the situation in which it was smoked. Situational variables were entered as random effects, meaning that their effects were free to vary across subjects. We also examined whether observed effects could be accounted for by the influence of conditions at the time of the satisfaction assessment (as opposed to conditions reported at the time of smoking). Finally, composite models were constructed to examine joint effects and identify unique predictors.

To investigate whether subjects who differed in average cigarette satisfaction had different cessation outcomes, we used survival analyses to examine effects on three different outcome milestones (Shiffman et al., 2006), starting with a subset of 324 participants who remained in the study through the designated target quit date (TQD). Initial abstinence was defined as 24 hr without smoking after the TQD. That is, the analysis considered the time, from the start of treatment, that it took subjects to achieve 24-hr abstinence, while considering as censored subjects who never reached this milestone while under observation. Only subjects who achieved initial abstinence were eligible to be studied for lapsing. Thus, among the 305 participants who achieved 24 hrs of abstinence, we evaluated the risk of an initial lapse –the first episode of smoking after initial cessation had been achieved, and it was recorded by participants on the ED. Among the 211 participants who had an initial lapse, we evaluated the risk of progression to relapse, defined as 3 consecutive days with five or more cigarettes per day. Any participant who reported abstinence but who had an expired air CO of ≥10 ppm on a weekly assessment was considered as having smoked on the first day after the last clean CO test. Analyses of the effects of satisfaction controlled for patch treatment, and we also evaluated the interaction between baseline satisfaction and patch treatment. We report hazard ratios (HR), which express the ratio of risk per unit time accounted for by predictor variables.

Results

Overall satisfaction

Each participant rated an average of 37.8 (12.3) cigarettes over an average of 9.8 (2.4) days (out of a possible 11); 90% contributed ratings of at least 20 cigarettes. The resulting dataset consisted of ratings for 14,882 cigarettes. Average satisfaction across all rated cigarettes assessed was 7.29 (SD=2.01) on a scale of 0-10, while average pleasantness was 6.41 (SD=2.43). The two ratings were highly correlated (r=0.69), even after accounting for within-subject covariance (rwithin=0.78; rbetween=0.54). Coefficient α was estimated at 0.81, indicating that the two items formed a reliable composite. We therefore focus the present analysis on this composite, which is henceforth referred to as “satisfaction,” while reporting unique instances where the two individual ratings produced different results. Figure 1 shows the distribution of composite satisfaction ratings, which averaged 7.06 (SD=2.05). The proportion of cigarettes rated highly satisfying (9 or 10 on the 0-10 scale) was 26.8% and the proportion rated highly unsatisfying (0-2) was only 2.5%.

Figure 1.

Distribution of composite satisfaction ratings for individual cigarettes.

Individual differences in satisfaction

Two thirds of response variation in cigarette satisfaction (intraclass correlation coefficient = 0.67) was attributable to between-person differences. Accordingly, we sought to identify factors that could account for between-subject differences in cigarette satisfaction. Table 1 shows the relationship between average satisfaction and various subject characteristics. The data show that women found cigarettes more satisfying than men (Table 1), but the difference was small, amounting to less than 1 point on the 11-point scale (B = .66, p<.001), and accounting for approximately 4% of observed between-subject variation in satisfaction ratings.

We also observed a relationship between smoking rate and satisfaction. Analyses of linear association suggested that satisfaction decreased as smoking rate increased (B = −.03, p<.01), but smoking rate accounted for only about 2% of between-subject variation. The analysis also revealed curvilinear trends. When a quadratic trend was included in the model, the amount of between-subject variation accounted for by smoking rate increased from 2% to 6% (B = .07, p<.001). Satisfaction decreased as smoking rate increased up to about 45 cigarettes per day, but that satisfaction increased thereafter, with the most positive responses observed among the 10 subjects (2.5% of the sample) who reported smoking over 45 cigarettes per day (Table 1). Examination of the relative proportion of satisfying versus unsatisfying cigarettes indicated that among those smoking fewer than 45 cigarettes per day, higher rates of smoking were associated with an increasingly greater proportion of unsatisfying cigarettes, while among those smoking 45 or more cigarettes per day, the proportion of unsatisfying cigarettes remained low.

Findings regarding smoking rate were not explained by measures of nicotine dependence. Also, neither the number of years participants reported smoking or the product of smoking rate and years smoking were associated with satisfaction (Bs < .11, ps>.60). The FTND did demonstrate a positive association with satisfaction (B = .12, p<.02), but this relationship was entirely accounted for by smoking rate, which is part of this scale. The NDSS was not significantly associated with satisfaction (B = .11, p>.33). Gender did not account for the main effects of smoking rate.

Ethnicity and education level were also related to satisfaction ratings (Table 1). African American subjects reported significantly higher cigarette satisfaction than Caucasian or other ethnic groups (B= .71, p<.009). We examined whether this might be due to the propensity of African-American smokers to smoke menthol cigarettes, but we found that menthol had no effect (B= −.08, p>.60) and that controlling for menthol brands actually increased the ethnic differences (B= .91, p<.003). Those with more than a high school education reported less satisfaction than those with less education (B = −.36, p<.04). Neither of these differences were accounted for by smoking rate or gender. No other demographic or smoking history variables were related to cigarette satisfaction.

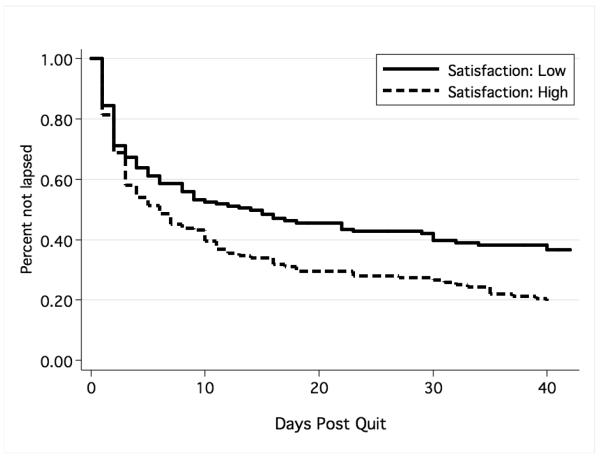

Satisfaction and smoking cessation outcomes

We evaluated the effect of individual differences in satisfaction on smoking cessation outcomes, separately examining effects on initial cessation, avoidance of lapses, and progression from lapse to relapse. Ratings of satisfaction and pleasantness were not associated with success in initial quitting (ps > .20), or with progression from lapse to relapse (ps > .60). However, after participants had achieved initial abstinence, greater average satisfaction was associated with a significantly increased risk of lapsing (Figure 3; HR=1.10, CI=1.01-1.20), such that the daily risk of lapsing increased by 10% with each 1-point increase in the satisfaction composite. Interestingly, examination of the satisfaction and pleasantness items revealed that the effect of the satisfaction composite was mostly accounted for by average pleasantness ratings (HR=1.11, CI=1.03-1.19), while average satisfaction did not significantly affect lapse risk (HR=1.06, CI=0.97-1.16). The prediction of lapse risk from pleasantness ratings remained essentially unchanged (HR=1.17, CI=1.08-1.26) after accounting for the significant covariate effects of NRT (HR=0.85, CI=0.30-2.45), female gender (HR=1.43, CI=1.07-1.92), and FTND (HR=1.16, CI=1.08-1.26) on cessation outcomes.

Figure 3.

Kaplan-Meyer survival curves for time to lapse after initial abstinence was established, for subjects above and below the median of average satisfaction.

We also assessed whether there were interactions between NRT and average baseline pleasantness. NRT did not interact with pleasantness in moderating lapse or relapse risk, but did moderate chances of initial quitting: the effect of NRT was greater among those with low pleasantness (HR=2.66, p<0.001), though still significant among those with higher pleasantness (HR=1.41, p<0.04; interaction HR=1.23, CI=1.10-1.37).

Contextual influences on satisfaction – within-subject effects

Satisfaction ratings varied considerably across particular cigarettes within subjects. Fully 60% of all subjects varied their ratings across by at least 4 points, while 18% of the sample varied their ratings by at least 7 points on our 11-point rating scale. Altogether, 33% of variation in cigarette satisfaction was due to variation among cigarettes within each subject.

Smoking satisfaction was assessed after a time lag, at the next time-sampling assessment. Satisfaction ratings were uncorrelated with the length of this interval (B < .001, p>.32). Satisfaction ratings decreased very slightly over the 2-week observation period, dropping 1/40th of a point each day (B = −.026, p<.03). All analyses controlled for this effect.

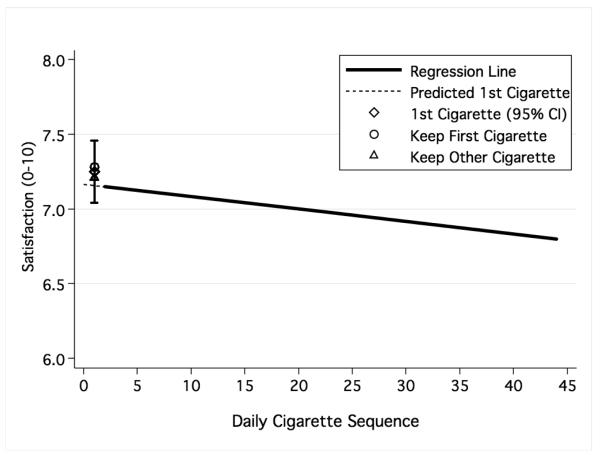

First and subsequent cigarettes of the day

Satisfaction ratings decreased slightly as additional cigarettes were smoked during each study day, dropping by 9/1,000th of a point (Figure 2; B = −.009, p<.02) for each successive cigarette in a day. There were no non-linear quadratic (B = 0.000, p>.15) or cubic (B = 0.000, p>.3) effects. The linear effect was controlled in all analyses.

Figure 2.

Satisfaction across the daily cigarette sequence. The solid line shows the trend (modeled from multi-level regression) for satisfaction to decrease over successive cigarettes (excluding the first cigarette of the day). The dashed line represents the extension of that predictive line to the first cigarette of the day. The hollow diamond represents the actual observed value of satisfaction for the first cigarette (with error bars indicating its 95% confidence interval), and the other symbols represent the observed values for subgroups that did or did not designate the first cigarette of the day as the one they would most hate to give up (confidence interval for these not shown, because they obscure the figure).

The first cigarette of the day is often cited as a uniquely important one, as it is smoked following prolonged deprivation. The satisfaction of the first cigarette of the day averaged 7.25 (SD (within) = 1.36; SD (between) = 1.52), and satisfaction with all other cigarettes averaged 7.11 (SD (within) = 1.19; SD (between) = 1.69). However, since the data had already showed that satisfaction dropped over successive cigarettes, we sought to test whether the first cigarette of the day was particularly satisfying, over and above its serial position. We first used regression to estimate the trend for satisfaction over successive cigarettes, not counting the first. This model projected that the satisfaction for the first cigarette would be 7.16. The projected value did not differ from the actual observed value (residual = 0.09, p>0.3), indicating that the first cigarette of the day provided no unique satisfaction relative to the overall trend for satisfaction to decline over cigarettes (Figure 2). Further, the projected/observed residuals were similar for those who did (M = 7.27; SD (within) = 1.38; SD (between) = 1.53) and did not (M = 7.21; SD (within) = 1.38; SD (between) = 1.53) say the first cigarette of the day was the hardest one to give up (Figure 2; residuals 0.12, 0.05, ps>0.3), and among those who smoked their first cigarette of the day within 30 minutes of waking (M = 6.97; SD (within) = 1.38; SD (between) = 1.53) or later (M = 7.28; SD (within) = 1.38; SD (between) = 1.53; residuals −0.18, 0.13, ps>0.3).

Craving

We assessed whether subjects’ satisfaction with smoking a particular cigarette was related to the intensity of craving preceding that cigarette. Analyses controlled for day in study and serial position of the cigarette within the day. Results indicate that cigarettes smoked when the smoker was experiencing more intense craving were most satisfying (Figure 4; B = .20, p<.001). To ensure that this finding was not due to a biasing influence of craving intensity at the time of the satisfaction assessment (as opposed to at the time of smoking), we controlled for the influence of craving at the time of assessment. This did not change the result (B = .20, p<.001). Craving at the time of smoking accounted for approximately 20% of between-subject variation and 10% of the within-subject variance in satisfaction.

Figure 4.

Association between satisfaction and positive affect (PA) and craving at the time of smoking (both on the 0-10 point X-axis). The figure shows the observed mean values, and the fitted line(s) from, multi-level regression models that partial out within-subject mean satisfaction.

Positive affect

In analyses that controlled for day in study and serial position of the cigarette within the day, we observed that cigarettes smoked when the smoker was experiencing more intense positive affect (PA) were more satisfying (B = .14, p<.001; see Figure 4). The influence of PA was reduced, but remained significant after accounting for the effects of PA at the time of assessment (B = .07, p<.004). Overall, PA accounted for approximately 2% of between-subject variation, and 8% of the within-subject variance in satisfaction.

Negative affect

In analyses that controlled for day in study and serial position of the cigarette within the day, cigarettes smoked when the smoker was experiencing more intense negative affect were less satisfying (B = −.10, p<.001). However, this effect disappeared when we controlled for NA reported at the time of the satisfaction ratings (B = −.03, p>.30), so it may be attributable to affective bias at the time of rating.

Other context variables

In analyses that controlled for day in study and serial position of the cigarette within the day, consumption of alcohol, coffee, or food at the time of smoking had no significant effect on subsequent ratings of satisfaction (Bs < .20, ps > .14). Likewise, cigarettes smoked in settings where smoking was restricted or after the smoker moved from a non-smoking area to be able to smoke were no more satisfying than those that were unrestricted or did not require the smoker to move (Bs <.09, ps>.26). However, cigarettes smoked when other people were smoking were rated as more satisfying (B = .12, p<.03).

Multivariate composite model

Thus far, we have separately and individually considered a range of subject-level and cigarette-level variables as influences on satisfaction. To examine their joint effects and identify unique predictors, we constructed a composite model that included the significant subject-level variables (gender, ethnicity, education, and smoking rate) and cigarette-level variables (day of rating, serial position within each day, craving, PA, and the presence of other people smoking), along with controls for craving and PA at the time of the satisfaction ratings. Results (Table 3) indicate that gender, smoking rate, craving and PA were statistically significant predictors of satisfaction in the composite model (Table 3). Ethnicity, education and the presence of other people smoking did not independently contribute to satisfaction in this model. Day of the study and seriual position of the cigarette continued to show small but significant effects. PA and craving at the time the satisfaction ratings were made also continued to be significant.

Table 3.

Mixed-Effects Model: Satisfaction Predicted from Individual Differences and Situational Context of Smoking

| Effects | B | SE | p value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Mean: Intercept | 2.420 | 0.766 | 0.002 |

| Days in Study | −0.021 | 0.005 | 0.000 |

| Daily Cigarette Number | −0.008 | 0.003 | 0.027 |

| Gender (Female) | 0.286 | 0.147 | 0.052 |

| Ethnicity (AA) | 0.216 | 0.146 | 0.139 |

| Education (Post HS) | 0.112 | 0.148 | 0.449 |

| CPD (linear) | −0.570 | 0.176 | 0.001 |

| CPD (quadratic) | 0.043 | 0.015 | 0.003 |

| Craving and affect at the time of satisfaction rating | |||

| PA | 0.141 | 0.017 | 0.000 |

| Craving | 0.037 | 0.008 | 0.000 |

| Situational context at the time of smoking | |||

| PA | 0.053 | 0.018 | 0.003 |

| Craving | 0.186 | 0.021 | 0.000 |

| Others Smoking | 0.078 | 0.047 | 0.099 |

| Variance Components | Variance | SE | p value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Mean: Intercept | 4.156 | 0.635 | 0.000 |

| Within-Subject Residual | 1.305 | 0.029 | 0.211 |

| Daily Cigarette Number | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.516 |

| PA | 0.046 | 0.009 | 0.000 |

| Craving | 0.044 | 0.009 | 0.000 |

| Others Smoking | 0.097 | 0.058 | 0.135 |

Note. B Estimates the amount of change in satisfaction for a 1-point change in the predictor. When the predictor is categorical (e.g., gender), it estimates the difference between groups. Covariance estimates not shown.

Discussion

This study examined cigarette-by-cigarette satisfaction with ad lib smoking in the natural environment. Overall, a majority of smokers found most of the cigarettes they smoked to be satisfying, with about a quarter regarded as highly satisfying. Nevertheless, we observed variation in satisfaction both among smokers and among different cigarettes within each smoker.

Subjective satisfaction was unrelated to nicotine dependence, as assessed by two different scales (FTND and NDSS). This was somewhat surprising, as there were theoretical reasons for expecting a relationship. The null result may well be the effect of two opposite effects: on the one hand, with increased dependence, growing tolerance and automaticity may diminish the satisfaction derived from cigarettes. On the other, increased dependence may make each cigarette more valuable and its effects more satisfying. These two trends may cancel each other out, resulting in no relationship. However, the lack of a relationship with satisfaction – at least within the range of dependence that we studied, seems to undermine Robinson and Berridge’s (1993) point that “liking” (satisfaction) should decrease as dependence increases.

We found that smokers who generally found smoking most satisfying, and particularly most pleasant, were at greater risk for lapsing after they had quit. The effect was not accounted for by nicotine dependence. This suggests that the memory of how pleasant smoking was may have promoted smoking, particularly in moments of temptation. Although much of the data on lapses has suggested the importance of negative reinforcement, this suggests that smokers’ seeking of positive reinforcement from smoking may also have an important role in lapses. We also found that smokers who found smoking more pleasant derived lesser benefit from nicotine patch treatment to help them achieve initial abstinence. Smoking cessation medications, including nicotine patch, do not substitute for the pleasure smokers may get from smoking, but rather protect them from withdrawal when they stop smoking. Thus, they may be of less benefit to those who derive strong pleasure from smoking. Further analyses of how satisfaction relates to quitting behavior and to cessation treatment are warranted.

We also observed that women and African-American smokers reported slightly higher satisfaction from smoking. This is striking because both groups are thought to have greater difficulty quitting smoking (Choi, Okuyemi, Kaur & Ahluwalia, 2004; Perkins, 2001). However, differences in satisfaction did not account for these demographic differences in smoking cessation outcome. We checked whether these ethnic differences might be due to African-American smokers’ preferences for methol-flavored cigarettes; it was not. It is not otherwise clear why African-American smokers or women would find smoking more satisfying, but it could help explain why African-American and female smokers develop greater dependence at lower levels of smoking.

The most striking and robust finding in our analysis was the relationship between craving preceding smoking and subsequent smoking satisfaction. Dunbar et al. (2008) documented that some cigarettes are more craved than others. These analyses show that the more intensely a smoker craved a particular cigarette, the more satisfying it was to smoke it: for every 1-point increase in antecedent craving, rated satisfaction increased about a quarter of a point. Importantly, this effect persisted even when we controlled for subject characteristics and for subjects’ craving at the time they rated their satisfaction. This highlights the importance of craving for smoking, consistent with findings from a recent EMA study of college smokers (Piasecki, Richardson & Smith, 2007) that found reduction of craving to be the single most common self-reported motive for smoking a cigarette, and reports by Shiffman et al (2002, 2004) that craving was a robust predictor of ad libitum smoking. Relief of craving itself appears to be a major source of reinforcement and satisfaction in smoking. Craving has been conceptualized by some as a state of tension, relief of which would be negatively reinforcing (Baker, Piper, et al., 2004). It is not known how craving arises or what central processes it represents, although we know that both smoking deprivation and exposure to smoking-related stimuli can increase craving (Tiffany, Cox & Elash, 2000). Subjective craving may simply be a marker for a variety of difference motivations, incentives, and potential reinforcements, a sort of final common indicator of expected reinforcement.

The finding that satisfaction is best predicted by craving seems at odds with Robinson and Berridge’s (1993, 2003) assertion that these represent two distinct and disassociated processes (“wanting” and “liking”) that develop on different trajectories in addiction. Robinson and Berridge’s theory does not explicitly require that wanting and craving are uncorrelated, but its assertion that wanting increases and liking decreases or disappears would suggest negative or no correlations. Also, the findings that most cigarettes were experienced as quite satisfying by this sample, even after decades of smoking, seems to go against Robinson and Berridge’s assertion that drug use ceases to be reinforcing or pleasant as addiction develops. Further analyses of how craving and satisfaction develop and are associated over the life course of smoking and other addictions are warranted.

We also examined the relationship between satisfaction and the situational stimuli that promote smoking. Even though Dunbar et al. (2008) found that cigarettes associated with alcohol, food, and coffee consumption were craved more intensely, they did not appear to be more satisfying. The fact that cigarettes smoked when drinking alcohol were not rated as more satisfying was particularly puzzling, for two reasons. First, laboratory studies (Kirchner & Sayette, 2007; Rose et al, 2002; Glautier et al., 1996) have reported greater smoking satisfaction when alcohol has been consumed, and one study (Rose et al, 2002) specifically attributed this to the pharmacological interaction of alcohol and nicotine. Laboratory tests of this relationship differ in several ways from our real-world assessments. The laboratory studies administered to subjects 0.5 g/kg ethanol, which may be higher or lower than the alcohol consumption by our subjects, which was not assessed. Subjects may also be more sensitive to any effect of ethanol in a laboratory study, because the drinking condition is highly salient, and the setting is otherwise sterile; the effects may not emerge in the more complex settings of real-world smoking.

Secondly, our findings discrepancy between our findings on alcohol and smoking satisfaction and those reported by Piasecki et al (2008) in a paper that appeared after the present paper was submitted. Piasecki et al (2008) used EMA methods to assess the relationship between situational variables and smoking satisfaction in a similar sample, but they report that drinking was associated with increased satisfaction (although the effect disappeared when controlling for context). The odds that a smoker would characterize a cigarette as “pleasant” increased by 31% if they had been drinking in the preceding hour, and drinking also increased endorsement of “good taste,” “relaxing,” and producing a “rush or buzz.” The differences could be due to the fact that we had subjects quantitatively rate satisfaction, whereas Piasecki et al (2008) had subjects choose among terms to characterize the effects of smoking. More intriguingly, the differences in results could be due to differences in the temporal relationship between drinking and smoking in each study. In our study, subjects reported whether or not they had been drinking in the 15 minutes prior to smoking, so our findings reflect the influence of drinking immediately before or possibly during smoking. In the Piasecki et al (2008) study, subjects reported whether they had consumed alcohol at any time in the hour preceding the assessment, and this was correlated with smoking that occurred in the 15 minutes preceding assessment. Thus, temporal resolution was limited: not only was it possible that the drinking actually followed the smoking, but the period between drinking and smoking could vary considerably, such that some subjects might be on the ascending limb of the blood-alcohol curve (associated with stimulation) and others on the descending limb (associated with sedation; Earleywine & Martin, 1993). More study is needed to determine whether the effects of alcohol on smoking satisfaction may vary by time, and on the ascending versus descending limb of the blood alcohol curve.

Consistent with Piasecki et al (2008), we found that cigarettes were considered more satisfying when others were smoking. This may be because the companionship implied makes smoking more rewarding, or because both the subject and other smokers are responding to something in the setting that makes smoking more satisfying, causing multiple people to smoke in such “rewarding” settings. It was notable that smokers who were emotionally distressed at the time they smoked (as indicated by NA) did not find smoking more satisfying – in fact, they found it less satisfying. Further analysis suggested this might have been due to confounding by mood at the time of rating (vs. the time of smoking): affective bias may negatively color all evaluations when subjects are emotionally distressed. Nevertheless, the data certainly contradict the expectation that cigarettes smoked when distressed would be more rewarding. Relief of emotional distress – whether from withdrawal or from exogenous sources – is often considered a major contributor to reinforcement from smoking (Baker, Piper, et al., 2004). We found no evidence for this perspective. Although Piasecki et al (2008) report that “relaxation” was the second most cited effect of smoking, the present study was consistent with EMA studies showing that smokers are not particularly disposed to smoke when experiencing negative affect (Shiffman et al, 2002, 2004), and that coping with negative affect is the least-cited motive for smoking (Piasecki et al, 2007). It has been suggested that the relevant aspects of emotional distress might not be subjectively discernable, or that smokers may smoke in anticipation of negative affect rather than when actually experiencing it (Baker, Piper, et al., 2004); such effects would not be picked up in our analysis, which depended on reports of experienced negative affect. However, the accumulation of negative findings on negative affect increasingly constrains explanations that rely on negative affect and affective relief as major explanations for smoking.

Conversely, we did find that smoking was experienced as more rewarding when smokers were in more positive moods (and this could not be attributed to positive rating bias at the time of rating). It’s been hypothesized (Caggiula et al., 2002) that nicotine makes other stimuli more reinforcing. Thus, smokers who are already in a positive mood may see it enhanced by smoking, making smoking seem satisfying. These data suggest that enhancing positive emotions could play a more important role in smoking satisfaction than does amelioration of negative emotions.

We had expected that satisfaction would diminish over the course of the smoking day, because of evidence that some nicotine effects diminish over time (Porchet, Benowitz & Sheiner, 1987; Fant, Schuh & Stitzer, 1995), and that nicotine satisfaction decreases with progressive nicotine intake (Perkins et al, 1994). However, we saw only an inconsequential decrease in satisfaction over successive cigarettes smoked during the day. Piasecki et al (2008) observed the opposite: satisfaction increased over the day, particularly relative to the morning hours. This might have been related to decreased reports of “rush/buzz” after the morning hours, but this is not clear. This leaves open the question of whether deactivation of nicotine receptors or acute nicotine tolerance substantially change smoking satisfaction over the course of the smoking day.

The first cigarette of the day was expected to be particularly satisfying, coming as it does after a period of deprivation and clearance of almost all circulating nicotine (Benowitz, Zevin, & Jacob, 1997). However, the first cigarette of the day, although it was numerically rated as most satisfying, lay on the overall trend-line for decreasing satisfaction over successive cigarettes across the day. In other words, it was no more satisfying than expected from the overall trend. More dependent smokers especially value the first cigarette of the day and start smoking soon after waking (Heatherington et al., 1989), but even smokers who indicated such behavior did not show any unique satisfaction (above the trend) from the first cigarette of the day. Piasecki et al’s (2008) findings suggest, however, that morning cigarettes may be particularly potent in producing the intoxication expressed as “rush/buzz” responses, which we did not assesses.

An important observation from this study is that smokers find most cigarettes at least moderately satisfying, and a substantial fraction of cigarettes very satisfying. This is contrary to some descriptions of addiction that suggests that most drug use is not rewarding, and driven solely by compulsion (e.g., Robinson and Berridges’ (1993) assertion that “liking” fades once use becomes well established). Our quantittaive satisfaction ratings cannot be compared directly to the qualitative designation of some cigarettes as “pleasant” or “unpleasant” in Piasecki et al (2008), but the findings seem consistent: 28% of cigarettes were designated as “pleasant” in Piasecki, corresponding closely to the 27% of cigarettes rated 9 or 10 on our satisfaction scale. Similarly, 2.2% of cigarettes in Piasecki were designated “unpleasant,” matching the 2.5% our subjects rated at 2 or less. What our analysis adds is that most of the remainder – all told, 60% of all cigarettes – were rated as moderately satisfying, falling between 5 and 8 on the 0-10 scale.

A broad issue in interpreting our findings (and contrasting them with Piasecki et al, 2008), is the degree to which assessment of pleasantness and satisfaction adequately capture the range of subjective effects that might be regarded as reinforcing. Although we only assessed smoking satisfaction, the literature suggests that there are several dimensions of subjective response to smoking (or nicotine dosing). In addition to a dimension of reward or positive satisfaction, researchers (e.g., Perkins et al., 2008; Cappelleri et al., 2007; Pomerleau et al., 1998; Kalman, 2002; Rose et al., 2000) have examined a variety of specific positive effects (e.g., relaxation, arousal), aversive effects (e.g., nausea), craving reduction, upper-airway sensations, and drug effects sometimes characterized as “head rush” (a subjective “buzz” or “rush”; Perkins et al., 2008). Analyses based both on ratings of smoking by large samples of smokers (Cappelleri et al., 2007), and of dose-response reactions to nicotine (Perkins et al., 2008), agree that satisfaction, or rewarding aspects of smoking, constitute a coherent factor, distinct from more specific effects, craving reduction, and rush/buzz. Consistent with the idea that ratings of satisfaction reflect reward obtained from smoking, satisfaction has been associated with progression from smoking lapses to relapse (Shiffman, Ferguson & Gwaltney, 2006) and from experimentation to regular smoking (Pomerleau et al., 1998), and satisfaction in response to nicotine dosing has been associated with smoking status (Perkins et al., 2008). This suggests that such responses are related to reinforcing effects of nicotine. In this sense, our analyses may capture core aspects of smoking’s rewarding effects, as also suggested by our finding that smokers who found ad lib smoking most rewarding were most likely to return to it after quitting, and benefitted less from nicotine treatment. Nevertheless, the meaning of subjective satisfaction is not entirely clear. What are smokers finding satisfying about smoking? The taste? The relief of craving? A specific nicotine effect they were seeking? For example, we found that smoking was judged less satisfying when smokers had been experiencing negative affect. Is this because smoking failed to improve their affect? Or because smoking improved their affect, but not as much as hoped? Further analysis of smoking satisfaction is needed to address such questions.

We only assessed smoking satisfaction, and not any of the other responses identified in the literature. It is not clear how aversive reactions influence smoking. Sherva et al (2008) report that people who report aversive responses to initial smoking are actually more likely to progress to smoking, and we have found (Shiffman, Ferguson, & Gwaltney, 2006) that aversive reactions to initial lapses (which are, in fact, largely aversive) do not deter progression to further lapses and relapse.

Investigators have been interested in head rush responses, because they are thought, on the face of it, to capture drug intoxication. Piasecki et al (2008) found that head rush responses were more common in the morning, and when smokinhg accompanied drinking. Head rush responses seem to have a different profile than positive rewarding responses, and seem to reflect low nicotine tolerance (Kalman, 2002; Perkins et al, 2003), consistent with Piasecki et al’s (2008) observation that they declined over the smoking day. There is some indication that positive evaluation of such responses is associated with smoking uptake, and may have some genetic basis (Sherva et al, 2008).

Cappelleri et al (2007) report that experiences of craving reduction as a result of smoking were distinct from rewarding responses or positive evaluation. In this study, we found that cigarettes preceded by more intense craving were experienced as more rewarding, suggesting an empirical association between the two distinct constructs. The literature provides little evidence regarding the influence of craving reduction on smoking, but the present findings, along with Piasecki et al’s (2008) report that craving reduction is the most common effect of smoking, suggest that this effect may have an important role in perpetuating smoking, consistent with many theoretical formulations of addiction (DiFranza & Wellman, 2005).

The range of potentially relevant subjective responses to smoking, and the lack of clarity about which responses are most relevant to various outcomes, certainly suggests that future studies should assess such responses multidimensionally. Perhaps a deeper conundrum is whether any set of subjective ratings, even those focused on “reward,” are adequate indices of the reinforcing effects of smoking. “Reinforcement” is ultimately defined in terms of the power of a consequential stimulus to result in repetition of the behavior that elicited it (Mazur, 2005). This does not require that the effects be pleasant or be perceived as such and, indeed, aversive stimuli can act as reinforcers under certain circumstances (Mazur, 2005). Indeed, smoking might reduce aversive states without really being perceived as pleasant at all. Thus, while the subjectively experienced reward from smoking and other behaviors is a fit subject for psychological study, such responses may not always correspond to “reinforcement,” which is defined by behavioral consequences, and, ultimately, by neurochemical events that are not yet fully understood (Kalivas & Volkow, 2005). This study examined which cigarettes were experienced as most rewarding, but may not have captured what makes cigarettes reinforcing.

An important limitation of our study was that, in common with the Piasecki et al (2008) study, our study sample was comprised of heavy smokers seeking treatment for smoking cessation. Patterns of satisfaction could be quite different in lighter smokers, whose smoking appears to be under greater stimulus control (Shiffman & Paty, 2006) and/or in smokers at earlier stages in the development of smoking careers.

Also, ratings of satisfaction were collected retrospectively, and thus might be biased due to recall bias or other factors that could change smokers’ views after the fact. Piasecki et al (2008) found that cigarettes were rated more positively when it had occurred in the preceding 15 minutes. Although we found no effect of the recall interval on rated satisfaction, our design did not include assessment of very recent cigarettes (subjects were not prompted for assessment within 10 minutes of reporting they had started a cigarette), so we may have missed effects due to very brief recall intervals. Our analysis did, however, control for participants’ state at the time of recall, potentially an important source of recall bias.

These limitations notwithstanding, the study’s strengths included the use of EMA methodology to gather near-real-time reports in smokers’ natural environments, and the analysis of very large the samples of thousands of smoking occasions reported by hundreds of smokers. Further, the fact that aggregated ratings of cigarette-by-cigarette satisfaction prospectively predicted lapse risk and moderated the effectiveness of nicotine patches provides empirical support for the validity of the ratings.

In summary, we examined smokers’ satisfaction with multiple cigarettes smoked ad libitum in real-world settings. Most cigarettes were experienced as moderately or highly satisfying. Smokers differed in how satisfying they found smoking, on average, and those who found smoking most satisfying, and particularly most pleasant, were most likely to lapse after achieving abstinence and were less helped by nicotine patch treatment. Whereas cigarettes that were smoked under more positive mood were later rated as more satisfying, those smoked in negative affect conditions were rated as less satisfying, though this may have been influenced by mood at the time of rating. The strongest predictor of satisfaction was craving intensity – cigarettes smoked when craving was higher were experienced as more satisfying, suggesting that craving is a final common pathway for incentive to smoke.

Table 2.

Univariate Mixed-Effects Models: Satisfaction Predicted from the Situational Context of Smoking

| Effects | β | SE | p value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Temporal context a | |||

| Days in Study | −0.013 | 0.005 | 0.010 |

| Daily Cigarette Number | −0.009 | 0.004 | 0.018 |

| Craving and affect at the time of satisfaction rating b | |||

| PA | 0.188 | 0.015 | 0.000 |

| NA | −0.153 | 0.015 | 0.000 |

| Craving | 0.067 | 0.009 | 0.000 |

| Situational context at the time of smoking | |||

| PA | 0.067 | 0.023 | 0.004 |

| NA | −0.025 | 0.025 | 0.300 |

| Craving | 0.197 | 0.022 | 0.000 |

| Others Smoking | 0.118 | 0.054 | 0.030 |

| Alcohol | 0.193 | 0.132 | 0.142 |

| Coffee | 0.078 | 0.067 | 0.242 |

| Eating | 0.060 | 0.061 | 0.327 |

| Smoking restrictions | 0.085 | 0.076 | 0.263 |

| Change Location | 0.010 | 0.049 | 0.838 |

Note. β Estimates the amount of change in satisfaction for a 1-point change in the predictor. Participant-level averages for each situational context variable were entered as covariates to separate within- from between-subject effects. These estimates represent with within-subject effects.

These variables were controlled in all analyses in the table and in the text. .

These variables were controlled only in analyses of the corresponding variable under “situational context”

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: The following manuscript is the final accepted manuscript. It has not been subjected to the final copyediting, fact-checking, and proofreading required for formal publication. It is not the definitive, publisher-authenticated version. The American Psychological Association and its Council of Editors disclaim any responsibility or liabilities for errors or omissions of this manuscript version, any version derived from this manuscript by NIH, or other third parties. The published version is available at www.apa.org/pubs/journals/abn.

References

- Baker TB, Brandon T, Chassin L. Motivational influences on cigarette smoking. Annual Review of Psychology. 2004;55:463–491. doi: 10.1146/annurev.psych.55.090902.142054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baker TB, Piper ME, McCarthy DE, Majeskie MR, Fiore MC. Addiction motivation reformulated: An affective processing model of negative reinforcement. Psychological Review. 2004;111:33–51. doi: 10.1037/0033-295X.111.1.33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baldinger B, Hasenfratz M, Battig K. Switching to ultralow nicotine cigarettes: Effects of different tar yields and blocking of olfactory cues. Pharmacology, Biochemistry, and Behavior. 1995;50(2):233–9. doi: 10.1016/0091-3057(94)00302-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Begg MD, Parides MK. Separation of individual-level and cluster-level covariate effects in regression analysis of correlated data. Statistics in Medicine. 2003;22:2591–2602. doi: 10.1002/sim.1524. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benowitz NL, Hatsukami DK. Gender differences in the pharmacology of nicotine addiction. Addiction Biology. 1998;3:383–404. doi: 10.1080/13556219871930. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benowitz NL, Zevin S, Jacob P. Sources of variability in nicotine and cotinine levels with use of nicotine nasal spray, transdermal nicotine, and cigarette smoking. British Journal of Clinical Pharmacology. 1997;43:259–67. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2125.1997.00566.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brandon TH, Herzog TA, Irvin JE. Cognitive and social learning models of drug dependence: Implications for the assessment of tobacco dependence in adolescents. Addiction. 2004;99(Suppl. 1):51–77. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2004.00737.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caggiula AR, Donny EC, Chaudhri N, Perkins KA, Evans-Martin FF, Sved AF. Importance of nonpharmacological factors in nicotine self-administration. Physiology and Behavior. 2002;77:683–687. doi: 10.1016/s0031-9384(02)00918-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cappelleri JC, Bushmakin AG, Baker CL, Merikle E, Olufade AO, Gilbert DG. Confirmatory factor analyses and reliability of the modified cigarette evaluation questionnaire. Addictive Behaviors. 2007;32:912–923. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2006.06.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carter B, Tiffany ST. Meta-analysis of cue-reactivity in addiction research. Addiction. 1999;94(3):327–40. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Choi WS, Okuyemi KS, Kaur H, Ahluwalia JS. Comparison of smoking relapse curves among African-American smokers. Addictive Behaviors. 2004;29:1679–1683. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2004.02.060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dar R, Kaplan R, Shahan L, Frenk H. Euphoriant effects of nicotine in smokers: Fact or artifact? Psychopharmacology. 2007;191:203–10. doi: 10.1007/s00213-006-0662-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DiFranza JR, Wellman RJ. A sensitization-homeostasis model of nicotine craving, withdrawal, and tolerance: Integrating the clinical and basic science literature. Nicotine and Tobacco Research. 2005;7:9–26. doi: 10.1080/14622200412331328538. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dunbar M, Scharf DM, Shiffman S, Kirchner TR. An examination of situational correlates of cigarette cravings. 2008. Unpublished ms.

- Earleywine M, Martin CS. Anticipated stimulant and sedative effects of alcohol vary with dosage and limb of the blood alcohol curve. Alcoholism: Clinical and Experimental Research. 1993;17:135–139. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.1993.tb00738.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eissenberg T, Balster RL. Initial tobacco use episodes in children and adolescents: Current knowledge, future directions. Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 2000;59:41–60. doi: 10.1016/s0376-8716(99)00164-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eissenberg T. Measuring the emergence of tobacco dependence: The contribution of negative reinforcement models. Addiction. 2004;99(Suppl. 1):5–29. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2004.00735.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fant RV, Schuh KJ, Stitzer ML. Response to smoking as a function of prior smoking amounts. Psychopharmacology. 1995;119:385–390. doi: 10.1007/BF02245853. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Foulds J. The neurobiological basis for partial agonist treatment of nicotine dependence: Varenicline. International Journal of Clinical Practice. 2006;60(5):571–576. doi: 10.1111/j.1368-5031.2006.00955.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glautier S, Clements K, White JA, Taylor C, Stolerman IP. Alcohol and the reward value of cigarette smoking. Behavioural Pharmacology. 1996;7(2):144–154. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glautier S. Measures and models of nicotine dependence: Positive reinforcement. Addiction. 2004;99:30–50. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2004.00736.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heatherton TF, Kozlowski LT, Frecker RC, Rickert W, Robinson J. Measuring the heaviness of smoking: Using self-reported time to the first cigarette of the day and number of cigarettes smoked per day. British Journal of Addiction. 1989;84(7):791–800. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.1989.tb03059.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heatherton TF, Kozlowski LT, Frecker RC, Fagerstrom KO. The Fagerstrom test for nicotine dependence: A revision of the Fagerstrom tolerance questionnaire. British Journal of Addiction. 1991;86(9):1119–27. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.1991.tb01879.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herskovic JE, Rose JE, Jarvic ME. Cigarette desirability and nicotine preference in smokers. Pharmacology, Biochemistry, and Behavior. 1986;24:171–5. doi: 10.1016/0091-3057(86)90333-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hughes JR, Higgins ST, Bickel WK. Nicotine withdrawal verus other drug withdrawal syndromes: Similarities and dissimilarities. Addiction. 1994;89:1461–70. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.1994.tb03744.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kalivas PW, Volkow ND. The neural basis of addiction: A pathology of motivation and choice. American Journal of Psychiatry. 2005;162:1403–1413. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.162.8.1403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kalman D. The subjective effects of nicotine: methodological issues, a review of experimental studies, and recommendations for future research. Nicotine & Tobacco Research. 2002;4:25–70. doi: 10.1080/14622200110098437. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kassel JD, Stroud LR, Paronis CA. Smoking, stress, and negative affect: Correlation, causation, and context across stages of smoking. Psychological Bulletin. 2003;129:270–304. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.129.2.270. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kirchner TR, Sayette MA. Effects of smoking abstinence and alcohol consumption on smoking-related outcome expectancies in heavy smokers and tobacco chippers. Nicotine and Tobacco Research. 2007;9(3):365–376. doi: 10.1080/14622200701188893. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koob GF, Nestler EJ. The neurobiology of drug addiction. Journal of Neuropsychology and Clinical Neuroscience. 1997;9:482–97. doi: 10.1176/jnp.9.3.482. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kozlowski LT, Herman CP. The interaction of psychosocial and biological determinants of tobacco use: More on the Boundary Model. Journal of Applied Social Psychology. 1984;14(3):244–256. [Google Scholar]

- Lamb R, Preston C, Schindler R, Meisch F, Davis J, Katz J, et al. The reinforcing and subjective effects of morphine in post-addicts: A dose-response study. Journal of Pharmacology and Experimental Therapeutics. 1991;259:1165–1173. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mazur JE. Learning and Behavior. Prentice-Hall; New Jersey: 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Miller N, Gold M. Dissociation of “conscious desire” (craving) from relapse in alcohol and cocaine dependence. Annals of Clinical Psychiatry. 1994;6:99–106. doi: 10.3109/10401239409148988. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nemeth-Coslett R, Henningfield JE, O’Keeffe MK, Griffiths RR. Nicotine gum: Dose-related effects on cigarette smoking and subjective ratings. Psychopharmacology. 1987;92:424–430. doi: 10.1007/BF00176472. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peper A. A theory of drug tolerance and dependence: A conceptual analysis. Journal of Theoretical Biology. 2004;229(4):477–90. doi: 10.1016/j.jtbi.2004.04.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perkins KA. Smoking cessation in women. CNS drugs. 2001;15(5):391–411. doi: 10.2165/00023210-200115050-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perkins KA, Ciccocioppo M, Conklin CA, Milanak M, Sayette MA. Mood influences on acute smoking responses are nicotine intake and dose expectancy. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 2008;117(1):79–93. doi: 10.1037/0021-843X.117.1.79. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perkins KA, Grobe JE, Fonte C, Goettler J, Cagguila AR, Reynolds WA, Stiller RL, Scierka A, Jacob RG. Chronic and acute tolerance to subjective, behavioral and cardiovascular effects of nicotine in humans. Journal of Pharmacology and Experimental Therapeutics. 1994;272(2):628–38. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perkins KA, Jacobs L, Sanders M, Caggiula AR. Sex differences in the subjective and reinforcing effects of cigarette nicotine dose. Psychopharmacology. 2002;163:194–201. doi: 10.1007/s00213-002-1168-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perkins KA, Jetton C, Keenan J. Common factors across acute subjective effects of nicotine. Nicotine and Tobacco Research. 2003;5:869–875. doi: 10.1080/14622200310001614629. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Piasecki TM, Richardson AE, Smith SM. Self-monitored motives for smoking among college students. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors. 2007;21(3):328–337. doi: 10.1037/0893-164X.21.3.328. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Piasecki TM, McCarthy DE, Fiore MC, Baker TB. Alcohol consumption, smoking urge, and the reinforcing effects of cigarettes: An ecological study. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors. 2008;22:230–239. doi: 10.1037/0893-164X.22.2.230. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pomerleau CS, Pomerleau OF. Euphoriant effects of nicotine in smokers. Psychopharmacology. 1992;108:460–65. doi: 10.1007/BF02247422. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pomerleau OF, Pomerleau CS. Euphoriant effects of nicotine. Tobacco Control. 1994;3:374. [Google Scholar]

- Pomerleau OF, Pomerleau CS, Namenek RJ. Early experiences with tobacco among women smokers, ex-smokers, and never-smokers. Addiction. 1998;93(4):595–599. doi: 10.1046/j.1360-0443.1998.93459515.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pontieri FE, Tanda G, Orzi F, Di Chiara G. Effects of nicotine on the nucleus accumbens and similarity to those of addictive drugs. Nature. 1996;382:255–7. doi: 10.1038/382255a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Porchet HC, Benowitz NL, Sheiner LB. Pharmocodynamic Model of Tolerance. Journal of Pharmacology and Experimental Therapeutics. 1987;244(1):231–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robinson TE, Berridge KC. The neural basis of drug craving: An incentive-sensitization theory of addiction. Brain Research Reviews. 1993;18:247–91. doi: 10.1016/0165-0173(93)90013-p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robinson TE, Berridge KC. Addiction. Annual Review of Psychology. 2003;54:25–53. doi: 10.1146/annurev.psych.54.101601.145237. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rose JE. Discriminability of nicotine in tobacco smoke: Implications for titration. Addictive Behaviors. 1984;9:189–93. doi: 10.1016/0306-4603(84)90056-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rose JE, Behm FM, Westman EC, Johnson M. Dissociating nicotine and nonnicotine components of cigarette smoking. Pharmacology, Biochemistry, and Behavior. 2000;67:71–81. doi: 10.1016/s0091-3057(00)00301-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rose JE, Behm FM, Westman EC, Kukovich P. Precessation treatment with nicotine skin patch facilitates smoking cessation. Nicotine and Tobacco Research. 2006;8(1):89–101. doi: 10.1080/14622200500431866. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rose JE, Brauer LH, Behm FM, Cramblett M, Calkins K, Lawhon D. Potentiation of nicotine reward by alcohol. Alcoholism: Clinical & Experimental Research. 2002;26(12):1930–1931. doi: 10.1097/01.ALC.0000040982.92057.52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Russell JA. A circumplex model of affect. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1980;39(6):1161–78. [Google Scholar]

- Scharf DM, Dunbar MS, Shiffman S. Smoking during the night: Prevalence and smoker characteristics. Nicotine & Tobacco Research. 2008;10(1):167–178. doi: 10.1080/14622200701767787. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shadel WG, Shiffman S, Niaura R, Nichter M, Abrams DB. Current models of nicotine dependence: What is known and what is needed to advance understanding of tobacco etiology among youth. Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 2000;59(S1):S9–S22. doi: 10.1016/s0376-8716(99)00162-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shelton DM, Alciati MH, Chang MM, Fishman JA, Fues LA, Michaels J, et al. CDC Surveillance Summaries (November) (no. SS-6) Vol. 44. MMWR; 1995. State laws on tobacco control -- United States, 1995. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sherva R, Wilhelmsen K, Pomerleau CS, Chasse SA, Rice JP, Snedecor SM, Bierut L, Neuman RJ, Pomerleau OF. Association of a single nucleotide polymorphism in neuronal acetylcholine receptor subunit alpha 5 (CHRNA5) with smoking status and with ‘pleasurable buzz’ during early experimentation with smoking. Addiction. 2008;103:1544–1552. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2008.02279.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shiffman S. Cognitive antecedents and sequelae of smoking relapse crises. Journal of Applied Social Psychology. 1984;14:296–309. [Google Scholar]

- Shiffman S. Dynamic influences on smoking relapse process. Journal of Personality. 2005;73(6):1–34. doi: 10.1111/j.0022-3506.2005.00364.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shiffman S, Balabanis M. Associations between alcohol and tobacco. In: Fertig J, Allen J, editors. Alcohol and tobacco: From basic science to public policy. National Institute on Alcoholism and Alcohol Abuse; Rockville, MD: 1995. pp. 17–36. National Institute on Alcoholism and Alcohol Abuse, Research Monograph No. 30. [Google Scholar]

- Shiffman S, Engberg J, Paty JA, Perz W, Gnys M, Kassel JD, Hickcox M. A day at a time: Predicting smoking lapse from daily urge. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 1997;106:104–116. doi: 10.1037//0021-843x.106.1.104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shiffman S, Ferguson SG, Gwaltney CJ. Immediate hedonic response to smoking lapses: Relationship to smoking relapse, and effects of nicotine replacement therapy. Psychopharmacology. 2006;184:608–614. doi: 10.1007/s00213-005-0175-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shiffman S, Ferguson SG, Gwaltney CJ, Balabanis’ MH, Shadel WG. Reduction of abstinence-induced withdrawal and craving using nicotine replacement therapy. Psychopharmacology. 2006;184:637–644. doi: 10.1007/s00213-005-0184-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shiffman S, Gwaltney CJ, Balabanis MH, Liu KS, Paty JA, Kassel JD. Immediate antecedents of cigarette smoking: An analysis from ecological assessment. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 2002;111:531–545. doi: 10.1037//0021-843x.111.4.531. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shiffman S, Hickcox M, Paty JA, Gnys M, Kassel J, Richards T. Progression from a smoking lapse to relapse: Prediction from abstinence violation effects, nicotine dependence, and lapse characteristics. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 1996;64:993–1002. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.64.5.993. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shiffman S, Paty JA. Smoking patterns of non-dependent smokers: Contrasting chippers and dependent smokers. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 2006;115:509–523. doi: 10.1037/0021-843X.115.3.509. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shiffman S, Paty JA, Gwaltney CJ, Dang Q. Immediate antecedents of cigarette smoking: An analysis of unrestricted smoking patterns. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 2004;113(1):116–171. doi: 10.1037/0021-843X.113.1.166. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shiffman S, Scharf DM, Shadel WG, Gwaltney CJ, Dang Q, Paton SM, et al. Analyzing milestones in smoking cessation: Illustration in a nicotine patch trial in adult smokers. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2006;74:276–285. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.74.2.276. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shiffman S, Waters AJ, Hickox M. The Nicotine Dependence Syndrome Scale: A multidimensional measure of nicotine dependence. Nicotine & Tobacco Research. 2004;6(2):327–48. doi: 10.1080/1462220042000202481. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]