Background

Although life expectancy is increasing in Scotland,1 the nation still has the highest rates of coronary heart disease (CHD) and selected malignancies in the UK and higher rates than most countries in Western Europe.2,3 The Scottish Health Surveys (SHeSs)—conducted in 1995, 1998 and 2003––were established to provide detailed, contemporary health information on a large, representative sample of the Scottish population. By capturing a range of behavioural, biological, psychological and social characteristics, their purpose was to monitor health in order to assist in policy formulation and the development of new health initiatives across the whole of Scotland.

How did the study come about?

Commissioned by the former Scottish Executive Health Department, the cross-sectional SHeSs took place in 1995/1996 (hereafter termed ‘1995’),4 1998/1999 (‘1998’)5 and 2003/2004 (‘2003’).6 Similar in content to the Health Surveys for England, the SHeSs are principally focused on cardiovascular disease (CVD) and related risk factors.7 All three have been conducted by the Joint Health Surveys Unit of the National Centre for Social Research and the Department of Epidemiology and Public Health, Royal Free and University College Medical School, London; in 2003, the MRC Social and Public Health Sciences Unit and the Scottish Centre for Social Research were also partners in the survey.

What does it cover?

Data were gathered in two stages: a face-to-face interview was followed by a nurse visit for the collection of biological material. Each survey consists of information on somatic and psychological health with dedicated modules on specific conditions and risk factors, such as asthma, dental health, physical activity, eating habits, smoking and drinking.8 Additionally, anthropometric and, for a subsample, biological measurements such as blood pressure and blood and saliva specimens have been taken (Table 1). Early and current socio-economic information is available, with a range of measures of socio-economic status at the time of the survey as well as a measure of parental occupational social class.

Table 1.

Baseline SHeS data

| Health measures |

| CVD |

| Diabetes |

| Respiratory health |

| Accidents |

| Food poisoning |

| Self-assessed general health |

| Longstanding illness |

| Acute sickness |

| Psychiatric morbidity |

| Health-related quality of lifea |

| Dental health |

| Use of health services |

| Use of dental services |

| Health-related behaviours |

| Alcohol consumption |

| Cigarette smoking |

| Dietary characteristics |

| Physical activity |

| Use of prescribed drugs and supplementsa |

| Immunizationsa |

| Infant feedinga |

| Exposure to environmental tobacco smoke |

| Biological measurements |

| Anthropometrya |

| Respiratory function |

| Blood pressure |

| Blood analytesa |

| Urine measurementsa |

| Biochemical measurement of smoking |

| Electrocardiograma |

| Individual socio-demographic characteristics |

| Economic activity status |

| Occupational social class |

| Education |

| Ethnicity |

| Religiona |

| Parental social classa |

| Household characteristics |

| Composition |

| Relationships of householdersa |

| Tenure |

| Car ownership |

| Receipt of state benefits |

| Incomea |

| Economic status/occupation of household reference persona |

| Area deprivation |

a2003 only; bprescribed drugs, contraceptive pills, vitamin supplements and nicotine replacement therapy; cheight (length, demispan), weight, waist, hip and mid-upper arm circumference (1998 and 2003); dtotal cholesterol, high-density lipid cholesterol, C-reactive protein (1998 and 2003), γ-glutamyl transferase (1995 only), fibrinogen, glycated haemoglobin, blood lead (1995 only) (for adults) and ferritin, total and house dust mite-specific immunoglobulin E (1998 and 2003) and haemoglobin (for children 11–15 years); sodium, potassium and creatinine (for 2003 adults).

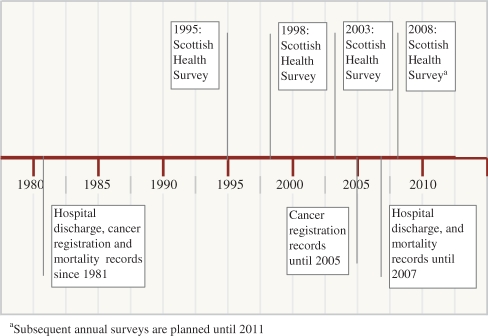

A prospective element of the surveys is provided by linkage to data on hospitalizations and mortality. The Information Services Division (ISD) of National Health Service (NHS) Scotland maintains a database of deaths and Scottish Morbidity Records (SMRs) of cancer registrations and discharges from NHS hospitals in Scotland, linked to each other for individual patients (Table 2). The latter hold information including the reason for the visit, length of stay and waiting time. Emergency, transferred and elective admissions are included in total hospital admission; audits have shown that these data are ∼90% accurate in identifying the correct diagnosis,9 and completeness of SMR data is ∼99%.10 During the original survey interview, participants were asked to consent to their (or their child's) name, address and date of birth being sent to the ISD for confidential linkage to their health records. Over 90% of SHeS participants consented at each survey. Since 2004, they have been followed up with regular mortality and hospital discharge data linkage from 1981 to December 2007, and cancer registrations (also from 1981) to December 2005 (Figure 1); ongoing linkage is planned for the surveys being conducted from 2008 to 2011.11 Retrospective data from 1981 until conduct of survey interview provides information on hospital diagnoses of any pre-existing morbidity. Similar linkage had previously been carried out in a randomly selected sample of individuals admitted to Scottish general hospitals in the late 1960–1970s12 and registered users of general practices in the mid-1980s.13

Table 2.

Data available according to each SMR scheme

| Code | Record type |

|---|---|

| SMR00 | Outpatient |

| SMR01a | General/acute inpatient/day case |

| SMR02 | Maternity |

| SMR04a | Mental health inpatient/day case |

| SMR06a | Cancer register |

| SMR11 | Neonatal discharge |

| SMR50 | Geriatric (long stay) |

aAvailable in the minimum SHeS–SMR.

Figure 1.

Linkage of study members of the SHeSs to hospital discharge, cancer registry and mortality records

The current frequencies of SMR events and deaths in the Scottish Health Surveys Cohort are shown in Table 3. Additionally, matching of maternity (SMR02),14 and neonatal (SMR11)14,15 discharge records (separate systems from those of the SMR01 and SMR04 hospital discharges) is also possible (Table 2), providing an intergenerational component.15

Table 3.

Frequencies of deaths and hospital discharges from CVD to December 2007, and cancer registrations to December 2005, by baseline survey year

| 1995 | 1998 | 2003 | Total | Percentage | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number at risk | 7363 | 8305 | 10 470 | 26 138 | |

| CHD | 313 | 370 | 167 | 850 | 3.3 |

| Acute myocardial infarction | 120 | 156 | 62 | 338 | 1.3 |

| Cerebrovascular disease | 130 | 182 | 74 | 386 | 1.5 |

| Lung cancer | 52 | 80 | 19 | 151 | 0.6 |

| Bowel cancer | 36 | 38 | 10 | 84 | 0.3 |

| Prostate cancer | 14 | 25 | 12 | 51 | 0.2 |

| Breast cancer | 52 | 70 | 16 | 138 | 0.5 |

| All cancers combined | 443 | 541 | 150 | 1134 | 4.3 |

| All deaths | 504 | 736 | 331 | 1571 | 6.0 |

Who is in the sample?

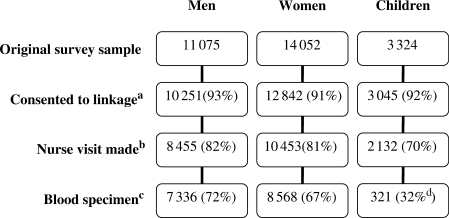

The surveys are based on a stratified, clustered random probability sample of individuals living in private households across the whole of mainland Scotland plus the larger inhabited islands, with one in three—over 300—postcode sectors (average population of 5000) in Scotland selected at each wave. Over time, the range of ages included in the surveys has widened. The survey in 1995 only included adults up to the age of 65 years; in 1998, children over 2 years of age and adults up to the age of 75 years were sampled, and, in 2003, the full age range was surveyed. The health surveys have been designed to provide data at both the regional as well as national level, allowing geographical as well as socio-economic comparisons.16 Weighting has been applied to take account of disproportionate sampling within health regions, differing probabilities of selection within households of different sizes and within multi-occupied addresses, and differential response. SHeS interview response has generally been high, varying from 81% in 1995 and 76% in 1998 to 60% in 2003. Overall, 91–93% of adult survey participants in 1995–2003 consented to their records being linked to NHS administrative data and parental consent was given for 92% of the participating children in 2003 (parental consent was not requested in 1998) (Figure 2), yielding a combined data-set of 26 138 individuals (Table 4). Nurse visits were made to around three-quarters of adults and children who consented to such a visit (Figure 2). Whereas blood samples were taken for only one in three of 11–15-year-old children, they were provided by most adults.

Figure 2.

Respondent composition by linkage, nurse visit and provision of blood specimen in the linked SHeS–SMRs data. aPercentages: percentage who consented to linkage of those in the original survey sample. bPercentages: percentage who had a nurse visit of those who consented to linkage. cPercentages: percentage who gave a blood sample of those who consented to linkage. dBased on a target sample of 1002 children aged 11–15 years

Table 4.

SHeS respondents providing consent to linkage according to sex and age

| Survey year (% target population) | Survey participants | Consenting to follow-up | Percentage |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1995 (81) | |||

| 16–24 | 1022 | 957 | 94 |

| 25–34 | 2000 | 1881 | 94 |

| 35–44 | 1803 | 1677 | 93 |

| 45–54 | 1534 | 1411 | 92 |

| 55–64 | 1573 | 1437 | 91 |

| Total | 7932 | 7363 | 93 |

| Total men | 3524 | 3304 | 94 |

| Total women | 4408 | 4059 | 92 |

| 1998 (76)a | |||

| 16–24 | 927 | 866 | 93 |

| 25–34 | 1738 | 1621 | 93 |

| 35–44 | 1836 | 1703 | 93 |

| 45–54 | 1590 | 1469 | 92 |

| 55–64 | 1492 | 1351 | 91 |

| 65–74 | 1464 | 1295 | 88 |

| Total | 9047 | 8305 | 92 |

| Total men | 3941 | 3664 | 93 |

| Total women | 5106 | 4641 | 91 |

| 2003 (67) | |||

| 0–15 | 3324 | 3045 | 92 |

| 16–24 | 740 | 668 | 90 |

| 25–34 | 1055 | 956 | 91 |

| 35–44 | 1620 | 1486 | 92 |

| 45–54 | 1411 | 1300 | 92 |

| 55–64 | 1411 | 1299 | 92 |

| 65–74 | 1091 | 994 | 91 |

| 75+ | 820 | 722 | 88 |

| Total | 11 472 | 10 470 | 91 |

| Total men | 3610 | 3283 | 91 |

| Total women | 4538 | 4142 | 91 |

| All surveys | |||

| Total men | 11 075 | 10 251 | 93 |

| Total women | 14 052 | 12 842 | 91 |

| Total adults | 25 127 | 23 093 | 92 |

| Total children | 3324 | 3045 | 92 |

| Total | 28 451 | 26 138 | 92 |

aConsent for linkage of 3892 surveyed children aged 2–15 years in 1998 was not sought.

What is attrition like?

Since the population of Scotland is relatively stable, with low emigration,17 follow-up is available on the vast majority of consenting SHeS respondents. The SHeS data have been linked to the Community Health Index18 as at January 2008, providing details on whether respondents have been registered with a Scottish general practice at the end of 2007. This allows identification of a small number (∼4 and 7% for 1995 and 1998 surveys, respectively19) of emigrants for whom follow-up morbidity records in the linked datasets may be incomplete.

What has it found? Key findings and key publications

As the linkage for the most recent (2003) survey only took place in 2007, publications using data from the combined surveys are few and currently largely limited to a series of conference presentations. Earlier work, based on linkage of the 1995 and 1998 survey data, found smoking, forced expiratory volume, C-reactive protein, fibrinogen and blood pressure at survey baseline to be significant predictors of morbidity and mortality.19,20 A separate analysis investigating factors associated with mortality and CHD events found that not being married, being physically inactive, being underweight and heavy smoking were significantly associated with higher risk of all-cause mortality; CHD risk increased with the number of cigarettes smoked per day, and decreased with increasing alcohol consumption, with the lowest risk in the most physically active.21 Selection bias assessment comparing the characteristics of the study participants with those in the general population of Scotland, showed that men in the study had lower CHD mortality than the general population. However, CHD incidence was the same, and although women in the study had a higher rate of hospitalization for CHD, there was no difference in female mortality.17 An investigation of the relationship between self-reported general health and subsequent all-cause mortality in Scotland, accounting for a history of CHD and geographical clustering found self-reported general health to be associated with all-cause mortality.22

Linkage of 1995 and 1998 SHeS data to the SMR04 system of psychiatric admissions and death records has allowed investigation of the association between psychological distress and first psychiatric hospital admission, with 0.9% of the survey population experiencing such admissions.23 Accounting for geographical clustering, multi-level survival analysis showed a highly significant increasing trend in the risk of first psychiatric admission with increasing psychological distress, which persisted following adjustment for a range of demographic, socio-economic and lifestyle risk factors. In addition, not being married, being in receipt of benefits, being a current smoker, being unemployed and self-assessing general health as poorer than ‘very good’ were also independently associated with psychiatric admission.23

By linking women with data on CVD and its risk factors in the 1995 and 1998 SHeSs to their offspring's birth characteristics in the SMR02 system, a transgenerational analysis examined birth weight of offspring in relation to maternal CVD and its risk factors.15 Lower offspring birth weight was found to be independently associated with higher incidence of psychiatric morbidity and lower incidence of diabetes but not CVD in the mother.

The full potential of the data from the SHeSs being linked to Scottish hospitalization and mortality as a research resource has yet to be realized24 and there are a number of projects currently underway. These include investigation of psychological distress as a predictor of future CVD and mortality;25 examination of the relationship between dietary characteristics and CVD;26 and several studies on self-reported alcohol consumption and alcohol-related deaths and hospital admissions.18 Other work aims to uncover the individual and combined contribution of different lifestyle factors to the excess burden of ill-health, and model CVD risk in relation to different treatment protocols.

The extensive data available from this study offer further scope for future work, such as examining: the association between socio-economic status and CVD separately in men and women, while controlling for preventable risk factors (smoking, physical inactivity and raised blood pressure); links between binge drinking and CVD; assessing the possibility of differential relationships between health behaviours and disease by socio-economic status; the relative effects of area and individual socio-economic status on health endpoints; and the role of emerging biological risk factors for CVD.

What are the main strengths and weaknesses?

The linkage of pooled data from these three large surveys with follow-up for hospitalizations and mortality has generated a large prospective cohort study that facilitates the examination of the role of a range of social, psychological, lifestyle and biological factors in the development of a range of important chronic diseases in a representative sample of the Scottish nation.19,20,27 With an additional survey underway and others planned, this resource will increase in size with continued follow-up through record linkage. As such, it is distinct from the Health Survey for England where linkage to morbidity records is not currently possible.

The surveys are representative of individuals living in private households and thus exclude those living in communal establishments, such as residential care and prisons or those in the armed forces. There are potential sources of bias including that arising from response to the original interview and agreement to linkage of records.24 The assumption that individuals are alive, if there is no trace of a death record, leads to the possible misclassification of those who have emigrated and subsequently died or had an event. However, low emigration levels mean such an occurrence will be infrequent and the additional linkage to the Community Health Index allows identification of the small number of potential emigrants with incomplete morbidity records. Retrospective data on pre-existing hospital-diagnosed morbidity prior to the conduct of survey interview will be incomplete for survey participants immigrating to Scotland after 1981. With only up to 13 years of follow-up since the baseline surveys, and with the age restrictions that were applied to the early surveys, the number of outcomes is currently modest. This does, however, represent a total of almost 200 000 person-years of follow-up and the power of the study will of course increase as the cohort matures.

Can I get hold of the data? Where can I find out more?

For each of the three surveys, data on consenting respondents are available in two distinct formats: the ‘minimum’ datasets and the ‘full’ datasets. The minimum datasets contain a set of summary variables derived from the linked SMR data (Table 2) [e.g. causes of death, incidence of acute myocardial infarction, stroke, cancer and psychiatric admissions (SMR04),28 with corresponding dates] along with the complete health survey record. The full datasets contain fields from individual, anonymized patient SMR records. The minimum datasets are freely available to the wider research community by request from Catherine.storey@isd.csa.scot.nhs.uk or David.clark@isd.csa.scot.nhs.uk at ISD. Those who wish to access the full data files may request permission from the Privacy Advisory Committee at the ISD by contacting pac@isd.csa.scot.nhs.uk.11

Funding

MRC and National Centre for Social Research (WBS Code U.1300.00.001.00013.01); Wellcome Trust fellowship grant (WBS Code U.1300.00.006.00012.01). The MRC SPHSU is jointly funded by the MRC and the Chief Scientist Office of the Scottish Government Health Directorates.

Conflict of interest: None declared.

References

- 1.Hanlon P, Walsh D, Buchanan D, et al. Chasing the Scottish Effect. Why Scotland Needs a Step-change in Health if it is to Catch up with the Rest of Europe. 2001. Glasgow: Public Health Institute of Scotland and Information and Statistics Division of the Common Services Agency. [Google Scholar]

- 2.CHD. mortality in Scotland. [23 January 2009, date last accessed]. http://heartstats.org.

- 3.Cancer: overview. http://www.scotpho.org.uk/home/Healthwell-beinganddisease/HealthWellBeingAndDisease.asp.

- 4.Dong W, Erens B, editors. Scottish Health Survey 1995. 2 Vols. Edinburgh: The Stationery Office; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Shaw A, McMunn A, Field J, editors. The 1998 Scottish Health Survey. 2 Vols. Edinburgh: The Stationery Office; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bromley C, Sproston K, Shelton N, editors. The 2003 Scottish Health Survey. 4 Vols. Edinburgh: The Stationery Office; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sprogston K, Primatesta P, editors. Health Survey for England 2003. 3 Vols. London: The Stationery Office; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Craig R, Deverill C, Pickering K, Prescott A. Methodology and response. In: Bromley S, Sproston K, Shelton N, editors. The Scottish Health Survey 2003, Technical Report, Ch. 1. Vol. 4. Edinburgh: The Scottish Executive Department of Health; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Harley K, Jones C. Quality of Scottish Morbidity Record (SMR) data. Health Bull (Edinb) 1996;54:410–17. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Managing Data Quality: SMR Completeness. [30 October 2008, date last accessed]. http://isd.scot.nhs.uk/isd/1607.html. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kendrick S, Clarke J. The Scottish record linkage system. Health Bull (Edinb) 1993;51:72–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ryan DH. A Scottish record linkage study of risk factors in medical history and dementia outcome in hospital patients. Dementia. 1994;5:339–47. doi: 10.1159/000106744. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Tunstall-Pedoe H, Woodward M, Tavendale R, A'Brook R, McCluskey MK. Comparison of the prediction by 27 different factors of coronary heart disease and death in men and women of the Scottish Heart Health Study: cohort study. Br Med J. 1997;315:722–29. doi: 10.1136/bmj.315.7110.722. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Cole SK. Scottish maternity and neonatal records. In: Chalmers I, McIlwaine GM, editors. Perinatal Audit and Surveilance. London: Royal College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists; 1980. pp. 39–51. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Leyland AH. Making an Impact: The Importance of Routine Data Sources for Population Health Research. Plenary presentation at Annual Scientific Meeting of the Australasian Epidemiological Association. Hobart, Australia: Australasian Epidemiologist; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gray L. Comparisons of Health-related Behaviours and Health Measures Between GLASGOW and the Rest of Scotland. Glasgow: Glasgow Centre for Population Health; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Smith BH, Campbell H, Blackwood D, et al. Generation Scotland: the Scottish Family Health Study; a new resource for researching genes and heritability. BMC Med Genet. 2006;7:74. doi: 10.1186/1471-2350-7-74. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.McDonald SA, Hutchinson SJ, Bird SM, et al. Association of self-reported alcohol use and hospitalisation for an alcohol-related cause in Scotland: a record-linkage study of 23 183 individuals (in press) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lawder R, Elders A, Clark D. Using the Linked Scottish Health Survey to Predict Hospitalisation & Death. An Analysis of the Link Between Behavioural, Biological and Social Risk Factors and Subsequent Hospital Admission and Death in Scotland. 2007. Main Report. Edinburgh: NHS Health Scotland & Information Services NHS NSS. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hanlon P, Lawder R, Elders A, et al. An analysis of the link between behavioural, biological and social risk factors and subsequent hospital admission in Scotland. J Public Health (Oxf) 2007;29:405–12. doi: 10.1093/pubmed/fdm062. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Leyland AH, Whyte B, Finlayson A, Clark D, Craig P. Linking Health Survey Data to Routine Data: Factors Associated with IHD First Events and Mortality in Scotland. 2004. Society for Social Medicine Annual Scientific Meeting; 15–17 September 2004. University of Birmingham, Birmingham, UK: Journal of Epidemiology and Community Health. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Gray L, Leyland A. Self-reported General Health and Subsequent Mortality. 2005. pp. 218–25. 13th Annual EUPHA meeting: Promoting the Public's Health: reorienting health policies, linking health promotion and health care; 10–12 November 2005; Graz, Austria: Journal of Epidemiology and Community Health. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Stewart C, Titterington DM, Leyland AH. The Association Between the GHQ-12 and Psychiatric Hospital Admission in Scotland [Poster] 2007. Society for Social Medicine Annual Scientific Meeting/International Epidemiological Association European Group Meeting, 2007; Cork, Republic of Ireland. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Leyland AH, Finlayson A, Clark D, Dundas R, Whyte B, Craig P. Assessing the Representativeness of Health Surveys. European Public Health Association Conference. Oslo: EJPH; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Gray L, Batty GD, Der G, Hunt K, Leyland AH. Psychological Distress as a Predictor of Future Cardiovascular Disease and Mortality: Pooled Analyses of Three Large Scottish Cohort Studies. 2008. (1995 to 2006). The European Public Health Association conference; 5–8 November 2008. Lisbon, Portugal. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Uses of the Scottish Health Survey. [30 October 2008, date last accessed]. http://openscotland.gov.uk/Topics/Statistics/Browse/Health/scottish-health-survey/Uses.

- 27.Lawder R, Elders A, Clark D. Using the Linked Scottish Health Survey to Predict Hospitalisation & Death. An Analysis of the Link Between Behavioural, Biological and Social risk Factors and Subsequent Hospital Admission and Death in Scotland. 2007. Technical Report. Edinburgh: NHS Health Scotland & Information Services NHS NSS. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Stewart C. Risk Factors for Psychiatric Hospital Admissions in Scotland. 2006. [Master of Public Health Degree]. Glasgow: University of Glasgow. [Google Scholar]