Abstract

We evaluated a modified teaching approach for improving the performance of adults with severe disabilities who were making minimal progress on teaching programs in a congregate day setting. An approach for enhancing progress was developed for implementation within the ongoing routine of the adult day setting using resources indigenous to the setting. The teaching approach, based on early intensive teaching programs, involved increasing teaching trials, adding another consequence to the reinforcement component, and reducing distractions. Improved progress accompanied the approach with each of 4 participating adults. Measures of happiness and problem behavior showed no detrimental effect on quality of life. Advantages and disadvantages of the teaching approach are discussed regarding implications for practitioners.

Descriptors: Adult services, severe disabilities, teaching programs

Despite efforts to involve adults with severe disabilities in supported work in community jobs, the majority of these individuals spend most of their weekday time in activity centers, adult education classrooms, and sheltered workshops (Conley, 2007; White & Weiner, 2004). These types of congregate day programs have had a longstanding presence across the United States and continue to increase in number (West et al., 2002).

One purpose of congregate day programs is to teach skills to adults with severe disabilities. However, providing educational services in these settings can present unique challenges. In particular, in contrast to schools, providing teaching services is not the primary responsibility expected of staff in many adult programs. Adult programs frequently are designed at least in part on a support model (Thompson et al., 2004), with the intent of providing a variety of services to promote a desirable quality of life on a day-to-day basis. In addition to teaching services, adult programs often provide leisure activities (e.g., community outings, recreational activities), relaxation time in accordance with a retirement lifestyle (cf. Heller, Miller, Hsieh, & Sterns, 2000), and various types of remunerative work opportunities. The latter services are almost always on a part-time basis (Garcia-Iriarte, Balcazar, & Taylor-Ritzler, 2007), such as when adults with severe disabilities spend some time during selected weekdays in a supported job and the rest of the time in the congregate setting (Lattimore, Parsons, & Reid, 2006).

As such, less time is devoted to teaching specified skills in these settings relative to schools for children and adolescents. Additionally, in accordance with the underlying support model, teaching of skills is often expected to take place during the naturally occurring situations in which the skills are needed in contrast to circumscribed sessions with repeated instructional trials (Sharpton & West, 2005). As a result, there are fewer teaching opportunities in adult day programs relative to school classrooms.

Although adult day programs along the lines just summarized are commonplace, the degree to which they effectively fulfill their missions, including teaching useful skills, has not received much investigatory attention (Parsons, Rollyson, & Reid, 2004). In this regard, the support model that underlies many activities within adult programs is heavily based on current values associated with that model (Thompson et al., 2004), and there is not always a research basis to substantiate the effectiveness of value-based activities (Lattimore et al., 2006). Most notably, concern exists that a support model may actually hinder skill acquisition in certain situations (Bailey, 2000). Such a concern coincides with more general reports suggesting that in many applied settings, people with severe disabilities often make slow progress on teaching programs (Sulzer-Azaroff, Pollack, Hamad, & Howley, 1998; Williams, DiVittorio, & Hausherr, 2002).

To empirically assess the contention that progress on teaching programs may be impeded in adult day settings, we administered a survey to staff responsible for supervising and/or carrying out teaching programs with adults who have severe disabilities. Respondents had to have worked with at least one adult with a severe disability for at least 1 year (respondents were attendees at training workshops on behavior analysis applications). Fifty-one staff working in congregate day programs for adults in 18 human service agencies (16 community programs, 2 state institutions) completed the survey. The survey item of concern questioned if any of the respondents' adult learners had been taught the same teaching program for periods of 3, 6, or 12 months or more before mastering the program. Eighty-two percent of the respondents reported they had adult learners who had been on the same teaching program for more than 1 year without mastering the program. These results suggest that slow progress of adults with severe disabilities on teaching programs is an issue faced by many support staff in congregate day settings.

In light of these findings, strategies are needed to better promote skill development in these settings. However, when considering changes to teaching approaches in adult day programs, it is important that the changes be practical in regard to the resources indigenous to the programs. Instructional approaches that require additional resources tend to be viewed negatively by service providers and may deter their adoption (Symes, Remington, Brown, & Hastings, 2006). Similarly, approaches that are overly complex or do not coincide with existing philosophical orientations may not be accepted by practitioners (Hieneman & Dunlap, 2000; Symes et al.).

For example, in the early history of behavior analysis, intensive or rapid teaching approaches were shown to accelerate acquisition of self-help skills among people with developmental disabilities (Azrin & Armstrong, 1973; Azrin & Foxx, 1971; Azrin, Schaeffer, & Wesolowski, 1976). However, these approaches were labor- and resource-intensive relative to traditional teaching programs, often involving a practitioner spending 5 or more hours per day teaching a skill to an individual and two staff initially working with an individual for teaching purposes (Azrin & Armstrong; Azrin et al.). The latter features likely explain why little attention has been given to intensive teaching approaches for adults since the early reports, as the features can be impractical in applied settings.

The purpose of this investigation was to evaluate a modified teaching approach for enhancing skill acquisition among adults with severe disabilities who were making minimal progress on teaching programs in a congregate day setting. The approach was designed to be applicable within the ongoing routine of the adult setting and with existing resources. In consideration of current concerns over enjoyment and overall quality of life within adult day programs as summarized earlier, evaluation of the teaching approach also included several measures related to these issues. First, measures of happiness indices (Davis, Young, Cherry, Dahman, & Rehfeldt, 2004) were included to evaluate if the teaching approach negatively impacted happiness. Second, problem behavior was measured because increased instructional trials represented one component of the modified teaching approach and problem behavior can be a concern when instructional demands are increased (cf. Miltenberger, 2006).

Method

Setting and Participants

The setting was an adult education program that was part of a large multi-service agency serving adults with severe disabilities. The adult education component of the agency employed 8 teachers and 7 teacher assistants, serving some 60 adult learners. The program provided a variety of services including classroom-based teaching and supported work. The investigation occurred within three classrooms of the program, in which adult learners were taught skills in the self-help, leisure, communication, and vocational domains. The classroom service structure was modeled after a community college schedule in which learners rotated to different classes within and across days, as well as to different supported work sites. Hence, each adult learner received teaching services on a specific program goal on a variable basis depending on his/her assignment to a respective class (usually several days per week – see Baseline for elaboration) and when the target skill was needed as part of a regularly occurring activity.

The participants were 4 adults with severe disabilities. Each adult had severe or profound cognitive disabilities as well as sensory and/or motor challenges. Ed had spastic quadriplegia, used a wheelchair for mobility, and communicated with gestures. Dot had a partial visual impairment, a history of self-injury and aggression, and communicated with a small number of words and idiosyncratic gestures. Gabe had a partial hearing impairment and spastic quadriplegia, used a wheelchair for mobility, was nonvocal, and communicated with a symbol communication board. Ron had microcephaly, used a wheelchair for mobility, and communicated with a few words and gestures.

Ed and Gabe received teaching services from the same teacher (Teacher 1), while Dot and Ron received teaching services from two other teachers (Teachers 2 and 3, respectively). Each teacher was licensed in special education and had over 25 years of teaching experience. Teacher 1 and Teacher 3 each were assisted by a teacher assistant. Both teacher assistants had a high school education and at least 11 years of experience. For Ed, the teacher and assistant typically shared teaching responsibilities on an equal basis (during the investigation, the teacher conducted 53% of Ed's teaching trials for his teaching programs and the assistant conducted 47%). Dot's teacher conducted all of her teaching trials. For Gabe, the assistant conducted most of his teaching trials (65% relative to 35% by the teacher) whereas for Ron, the teacher conducted most trials (86% relative to 14% by the assistant). Percentage of trials conducted by respective teachers and teacher assistants remained consistent across experimental conditions.

These individuals were selected for the investigation in the following manner. First, the 8 teachers in the adult education program were informed by the program director (experimenter) of the purpose of the project. Second, the teachers were asked to identify any learners in their classrooms who were making minimal or no progress on at least two teaching programs. Third, an experimenter reviewed existing data for all recommendations from the teachers to verify a lack of progress on two teaching programs. The learner participants just described represented the individuals who met the lack-of-progress criterion. Observations indicated the two programs selected for each learner were ongoing at least 2 weeks prior to initiation of the baseline condition of this investigation. Additionally, a review of available records indicated that at least one program for Ed, Gabe, and Ron had been in place for at least 37 weeks prior to baseline.

Teaching Programs

Each identified program addressed a skill acquisition goal as part of a learner's overall adult education plan and included a task analysis of the skill to be taught. Ed's programs involved learning to operate a paper cutter (6 task-analyzed steps) and stamp price tags with a store logo (6 steps). Dot's programs were ironing felt cloths to be used in making paper (22 steps) and following a picture work schedule (21 steps). Gabe's programs were getting his work apron from a wall hook to begin work (6 steps) and putting dishes in a sink (6 steps). Ron's programs were identifying two buildings by vocalizing the name of each building on request when delivering inter-agency mail to each building (2 steps) and identifying two specific classmates by name on request (2 steps). Each program was taught in a total task method according to the Teaching Skills Training Program (Parsons & Reid, 1999) that involved following the task analysis for the order of teaching each step, using a least-to-most assistive prompt sequence, quickly correcting learner errors in completing a step, and reinforcing program completion. All teachers and assistants had been trained in this approach to teaching using a performance- and competency-based staff training process (cf. Parsons, Reid, & Green, 1996).

Behavior Definitions and Observation Systems

The primary dependent variable was percentage of task-analyzed steps of a teaching program that a learner completed independently. Independent step completion was defined as performing a step as written in the task analysis without any prompting from the instructor (teacher or teacher assistant). The instructor recorded the prompt level provided to the learner for each step in the task analysis, or independent completion by the learner, every time the teaching program was conducted. Interobserver agreement checks were conducted on 24% of all sessions, including multiple times during each experimental condition for each learner, instructor, and teaching program. Interobserver agreement was assessed on a program step-by-step basis for independent completions, and calculated using the formula of number of agreements divided by number of agreements plus disagreements multiplied by 100%. Overall agreement for independent step completion averaged 97% (range, 80% to 100%), occurrence agreement averaged 93% (range, 50% to 100%), and nonoccurrence averaged 95% (range, 50% to 100%).

Two sets of secondary dependent measures were also conducted, pertaining to other learner behaviors and instructor behavior, respectively. The secondary dependent measures for learner behavior included happiness and unhappiness indices and problem behavior. Indices of happiness and unhappiness were defined as in previous research (Green & Reid, 1996; Ivancic, Barrett, Simonow, & Kimberly, 1997). Specifically, happiness was defined as any facial expression or vocalization typically considered to be an indicator of happiness among people without disabilities including smiling, laughing, and yelling while smiling. Unhappiness was defined as any facial expression or vocalization typically considered to be an indicator of unhappiness among people without disabilities such as frowning, grimacing, crying, and yelling without smiling. Problem behavior was defined as any action that could cause harm to a person or property.

Observations of happiness and unhappiness indices and problem behavior were conducted by an independent observer on a probe basis (13% of all teaching sessions), including multiple times during each experimental condition for each learner and teaching program. Data were collected using continuous, 15-s partial interval recording for each of the three behavior categories throughout the respective teaching session. Interobserver agreement checks were conducted during 57% of all observations, including for each learner and experimental condition. Interobserver agreement was calculated in the same manner described previously. Overall agreement for happiness indices averaged 96% (range, 67% to 100%), occurrence agreement averaged 87% (range, 50% to 100%) and nonoccurrence averaged 87% (range, 0% to 100%). Neither observer recorded any occurrences of unhappiness indices and problem behavior during any interobserver agreement check (see Results).

The secondary dependent measure pertaining to instructor behavior focused on teaching proficiency (i.e., treatment integrity). Teaching proficiency was probed throughout the investigation for two reasons. First, a lack of teaching proficiency could suggest a reason for slow learner progress on teaching programs. Hence, teaching proficiency was monitored initially to assess this variable in relation to learner progress. Second, a change in teaching proficiency might represent a confound when attributing possible changes in learner progress to the experimental intervention. Teaching proficiency was evaluated in accordance with previous research on effective instruction as outlined in the Teaching Skills Training Program (Parsons et al., 1996). Briefly, teacher performance was scored for each step in a program task analysis regarding whether the step was presented in the right order (i.e., as listed in the task analysis), prompting was provided if needed in a least-to-most assistive fashion, and error correction was provided appropriately. Teacher performance was also scored regarding whether reinforcement was provided appropriately. As defined in the Teaching Skills Training Program, correct reinforcement involved providing an apparently preferred consequence upon completion of the last step in the program task analysis. Each of these teaching skills was scored as correctly performed, incorrectly performed, or not applicable (e.g., no error correction was needed on a given program step). Teaching proficiency was calculated as percentage of all teaching skills performed that were performed correctly. Again based on previous research, acceptable teaching proficiency required a minimum of 80% correct skills performed during a teaching session (Parsons et al., Parsons, Reid, & Green, 1993).

Teaching proficiency was probed during 20% of teaching sessions, including during each experimental condition for each learner, instructor, and program. Interobserver agreement checks were conducted on 27% of all probes (also including each condition, learner, instructor, and program). Interobserver agreement was calculated by dividing the smaller percentage of skills performed correctly recorded by one observer by the larger percentage recorded by the other observer, multiplied by 100%. Interobserver agreement for correct teaching averaged 98% (range, 93% to 100%).

Experimental Conditions

Baseline.

During baseline, the instructors implemented the teaching programs in accordance with their usual routine and as prescribed in each learner's adult education plan. Each teaching program was implemented individually with a respective learner and began with a general cue for the learner to perform the task. The instructor then followed the total-task teaching procedures described earlier in terms of using a least-to-most assistive prompt sequence for those steps in the task analysis the learner did not perform independently, correcting learner errors on task steps by having the learner repeat the given step and providing increased assistance to prevent an error on the second attempt, and providing a positive consequence upon completion of the last step in the task analysis. The programs were designed to be taught until a given learner completed at least 80% of the task steps independently on three consecutive teaching sessions. At that point, the formal teaching program was discontinued and the learner was expected to perform the target skill during the daily routine with staff support.

As noted previously, teaching programs were conducted at different frequencies for each learner due to the varied classroom schedules of the learners and supported work placements. Typically, the learners' adult education plans called for each teaching program to be implemented once during each class session that focused on the skill area addressed by the teaching program (e.g., a vocational skill would not be taught during a leisure-skill class). Throughout baseline, all teaching programs were implemented between 2 and 3 days per week per learner on average with one exception. One of Gabe's programs was implemented between 1 and 2 days per week on average.

Modified teaching.

Modifications to the teaching programs were based on early intensive or rapid teaching approaches described previously (Azrin & Foxx, 1971; Azrin et al., 1976). The intent was to apply selected procedural components from the early approaches that seemed amenable to the routines and design of current adult day settings. As such, the modified teaching intervention involved three components drawn from the original intensive teaching approaches: (a) increasing the frequency of teaching (though not to the extent in the original approaches), (b) providing a more highly preferred stimulus as a reinforcer relative to what was currently being used, and (c) reducing possible distractions (competing stimuli) during teaching sessions. Each of these components was developed with input from each learner's teacher during an initial meeting between the respective teacher and an experimenter. Improving teaching proficiency was not targeted with the intervention because the proficiency of each teacher and assistant was consistently above the pre-established teaching criterion (see Results).

The goal of the first component was to increase the number of teaching trials per week without interfering with the teacher's other classroom responsibilities. Hence, prior to establishing a new teaching schedule, the teacher's opinion was solicited regarding how she thought teaching frequency could be increased given her other duties. A general goal of increasing teaching trials by at least 3-fold per week relative to the number of trials provided during baseline was presented as a guideline. It was further explained that teaching trials could be increased by increasing, where possible, the number of days per week during which the program was taught, and by increasing the number of trials per day that the program was taught.

Each teacher was able to increase the number of teaching days per week and the number of teaching trials per day. The frequency of teaching was increased during the modified teaching condition to between 3 and 4 days per week per learner per program on average (relative to between 2 and 3 days per week for all learners during baseline, except for Gabe whose program was taught between 1 and 2 days per week during baseline). Regarding number of teaching trials, these increased for Ed's program from an average of 1.0 per teaching day during baseline to 6.8 per day during modified teaching, from 1.1 to 1.8 for Dot, from 1.1 to 1.7 for Gabe, and from 1.0 to 2.4 for Ron.

When considering increases in number of teaching days and trials per teaching day, each teacher was able to surpass the goal of increasing teaching trials per week by at least 3-fold except for Dot (there were 2.7 times as many teaching trials per week during modified teaching relative to baseline). Number of teaching trials per week increased from baseline averages for the 4 learners of 2.3, 2.2, 1.4, and 2.4, respectively, to 22.4, 5.9, 8.5, and 9.1, respectively, during modified teaching with the target programs. Dot's program was the least practical to have its teaching frequency increased 3-fold due to the relatively extended amount of time required to carry out her program of ironing cloth felts for preparation to make paper. One trial of Dot's teaching program required between 8 and 10 min. Length of time to complete a teaching trial for Ed, Gabe, and Ron was between 1 and 2 min, 2 and 3 min, and 1 min, respectively. Length of time to complete a teaching trial did not increase from baseline to the modified teaching condition.

The second component of the modified teaching program involved use of a highly preferred consequence. During baseline and in accordance with current teaching procedures commonly used in adult day programs, teacher praise was delivered as reinforcement for task completion. During the modified teaching condition, praise was supplemented with presentation of a highly preferred consequence in an effort to increase reinforcer potency for learner completion of the teaching program. Following baseline, staff opinion regarding favorite stimuli was used to select presumably highly preferred consequences. Each teacher expressed that there was a more highly preferred item or activity than praise that could be easily incorporated within the teaching process. Although caregiver opinion has been shown to be inconsistently accurate for identifying relative preferences among individuals with severe disabilities (see Ivancic, 2000, for a summary), such opinion has been accurate in a number of cases for identifying the most highly preferred or favorite stimuli (Favell, Realon, & Sutton, 1996; Green & Reid, 1996; Green, Reid, Rollyson, & Passante, 2005; Ivancic et al., 1997). Hence, each teacher identified what she believed to be a favorite stimulus to add to the praise aspect of the teaching process. The stimuli identified and used during modified teaching for Ed, Dot, Gabe, and Ron, respectively, were a choice of listening to music or sitting outside, several potato chips and a soda, a mini candy bar, and small pieces of candy. These stimuli were provided to the respective learners upon completion of the last step in the task analysis for each teaching trial. Probe observations conducted during the modified teaching condition (i.e., during the reliability observations and observations of happiness indices) indicated that each teacher provided the new consequences consistently.

The third component of the modified teaching program involved reducing distractions that appeared to occur during teaching sessions. The teacher was asked to identify any likely events evoking behavior that competed with desired learner responses during teaching and what may be done to eliminate those events. The following changes subsequently were made upon initiation of each modified teaching session in an attempt to reduce distractions: For Ed and Dot, a note was placed on the door to their classrooms requesting people not to interrupt due to an ongoing teaching session (during baseline sessions, the door was open and various staff frequently entered the room which appeared to evoke Ed's and Dot's attention, respectively); for Gabe, a note also was placed on the classroom door and the blinds on a window that was above the sink were closed (Gabe's attention while he was taught to put dishes in the sink during baseline seemed to be distracted by events that he could see through the window); and for Ron, potential distractions were reduced by waiting until people passed by on the sidewalk outside a building before initiating a trial of asking Ron to name the building to which he was delivering mail (during baseline, a trial was initiated as soon as he arrived at the building whether there were other people on the sidewalk with Ron or not). As with use of the new consequences, probe observations indicated each teacher carried out the reduced-distraction component during each teaching session.

Each of the components just noted — increased teaching trials, use of a more preferred consequence, and reduced distractions — remained in place throughout the modified teaching condition with each learner. Additionally, with Ed, an alteration was made to the consequence and distraction components after 11 days with modified teaching (see Results). Specifically, in addition to receiving a choice of listening to music or sitting outside upon completion of a teaching session, Ed was provided a few seconds of music after each teaching trial (Ed typically received three trials per session). Also, besides putting a note on the door, potential distractions were further reduced by conducting teaching sessions at a table facing a wall in contrast to a table facing the entire classroom space as occurred during baseline and the initial modified teaching sessions.

Experimental Design

For 3 of the learners, the experimental design was an alternating treatments design embedded within a multiple baseline across learners design. Following baseline, one of each learner's two teaching programs was arbitrarily selected to be targeted with modified teaching. Selected programs for Ed, Dot, Gabe, and Ron were operating a paper cutter, ironing felts, putting dishes in the sink, and identifying buildings, respectively. The other program for each learner that was not targeted with modified teaching continued within the baseline teaching condition. The supervisor of the teachers and assistants requested that they simply continue their current procedures with the latter programs (observations of teaching proficiency indicated that the teachers and assistants continued their standard teaching procedures with these programs). This process allowed for an analysis of the effects of modified teaching on (a) each learner's level of independent step performance on that program relative to baseline and relative to other adult learners who were still in the baseline condition in accordance with typical applications of a multiple baseline design, and (b) each learner's performance on the program receiving modified teaching relative to simultaneous performance on the program still receiving baseline (standard) teaching procedures. For the fourth learner (Ron), an alternating treatments design was initiated after the 3 other learners had mastered their targeted teaching programs.

Results

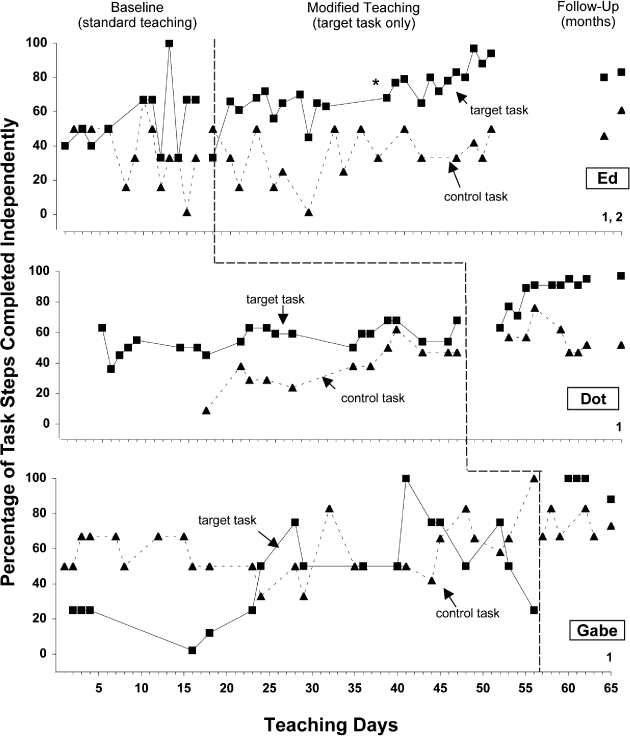

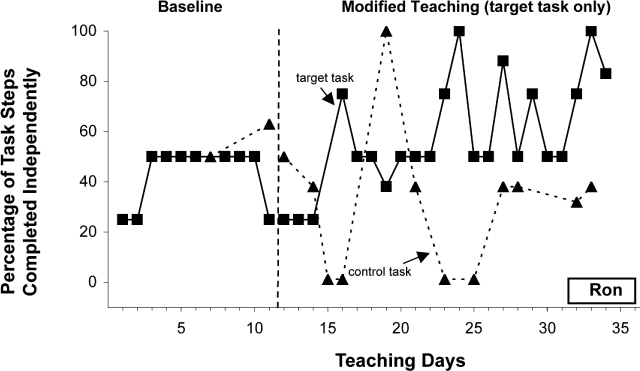

Effects of the modified teaching program on percentage of task steps of the target programs completed independently by Ed, Dot, and Gabe are shown on Figure 1. Percentage of target task steps completed independently during baseline increased in a slow and variable manner for each of these adult learners, suggesting that mastery would take many more teaching sessions. Ron (Figure 2) showed no increase in independent step completion during baseline. Overall, average percentage of steps completed independently during baseline averaged 54% (range, 33% to 100%) for Ed, 56% (range, 33% to 68%) for Dot, 47% (range, 0% to 100%) for Gabe, and 43% (range, 25% to 50%) for Ron.

Figure 1.

Percentage of program steps completed independently by each learner with the target and control tasks on each teaching day for each experimental condition. The asterisk (*) indicates where Ed's target program was revised by changing the reinforcement and distraction components.

Figure 2.

Percentage of program steps completed independently by Ron with the target and control tasks on each teaching day for both experimental conditions.

The percentage of tasks steps completed independently then increased more significantly during modified teaching for each learner's target program, with each learner except Ron reaching the agency mastery criterion of 80% independent step completion on three consecutive teaching sessions. Ron had two consecutive sessions with 80% independence, but then his teaching program had to be discontinued due to his teacher's absence from work due to a family medical situation. Increases in independent step completion occurred most rapidly for Dot and Gabe, who required only 6 and 3 days with modified teaching to reach the mastery criterion, respectively. Ed showed a mean increase in independent step completion during the first 11 days with modified teaching (average of 63%), but no increasing trend was apparent during those 11 days. Once the reinforcer and distraction components of Ed's program were further revised, he showed more notable increases in independent step completion and reached the mastery criterion in 12 days. Ron showed variable but gradual improvement during modified teaching, reaching the 80% level on the last 2 days of the condition. During 1- and/or 2-month follow-up observations (available for Ed, Dot, and Gabe), each learner maintained independent step completion at or above the 80% level.

Effects of the modified teaching on independent step completion are perhaps most apparent when comparing learner progress on the target programs versus progress on the control programs (also on Figures 1 and 2) that were taught throughout the investigation using procedures common in adult day settings. The control programs for Ed and Ron showed no improvements in terms of independent step completion while their target programs were showing improvement during modified teaching. The control programs for Dot and Gabe showed variable but gradual improvement during the baseline and modified teaching conditions with the target programs, but independent step completion on the control programs was always less than that with the target programs while the latter were receiving modified teaching. The control programs for Dot and Gabe (as well as the other 2 learners) never reached mastery.

Happiness Indices, Unhappiness Indices, and Problem Behavior

The modified teaching procedures were not accompanied by any consistent changes in indices of happiness and unhappiness or problem behavior. Ed and Dot showed relatively high levels of happiness throughout the investigation. Ed's indices of happiness averaged 68% of observation intervals during baseline and 54% during modified teaching with his target program, compared to 31% during baseline with his control program. Dot averaged 85% during baseline and 95% during modified teaching with her target program, relative to 90% during baseline with her control program. Happiness indices for Gabe and Ron were less frequent, with Gabe averaging 34% during baseline and 20% during modified teaching with his target program, relative to 21% with his control program. Ron averaged 23% and 21%, respectively, with his target program and 14% with his control program. Perhaps more notable evidence for a lack of an adverse effect of modified teaching on learner affect is reflected in a lack of unhappiness indices. Indices of unhappiness were not observed with any program for any student. Similarly, problem behavior never occurred for any learner, including during modified teaching, except on one occasion for Dot during baseline with her control program (average of 1% during baseline with the latter program).

Teaching Proficiency

Teaching proficiency remained above the pre-established 80% correct-teaching criterion (Parsons et al., 1993; 1996) throughout the investigation for the 3 teachers and 2 teacher assistants. Teaching proficiency averaged at least 96% correct teaching for each learner, target and control program, and experimental condition.

Conclusions and Implications for Practitioners

Results indicated that the modified teaching approach was accompanied by improved progress for 4 adults with severe disabilities who were previously making minimal or no progress on their respective programs. In contrast, no learner showed substantial progress nor met the mastery criterion on the programs that continued to be implemented with the standard teaching process common in adult day settings. Improved progress occurred without any consistent decreases in indices of learner happiness or increases in unhappiness indices or problem behavior.

Including several procedures in the modified program rather than relying on just one specific procedure likely enhanced the effectiveness of the intervention (Bailey & Burch, 2002, chap. 3). The teaching approach also seems straightforward in concept: When an individual is not making progress on a teaching program, consider increasing the number of teaching trials by approximately three-fold, providing a more highly preferred consequence, and reducing potential distractions. These procedures are relatively simple when compared to newer and generally more sophisticated teaching strategies (e.g., progressive time-delay prompting). Such simplicity is a likely advantage when attempting to promote adoption by practitioners who do not have extensive training in behavior analysis. In short, one seemingly practical means for practitioners to improve services in typical applied settings for adults is to reemphasize use of basic (and relatively noncomplex) behavioral procedures that currently are not used on a regular basis (Lattimore et al., 2006). The approach illustrated in this study may ensure that learners do not remain on teaching programs for extended time periods without making notable progress.

As indicated earlier, despite the success of intensive teaching programs for adult learners (e.g., Azrin & Armstrong, 1973; Azrin & Foxx, 1971; Azrin et al., 1976), little recent attention has been directed to their use. An implication for practitioners is that increased attention may be warranted on aspects of early intensive teaching formats. Modifications such as those in this investigation may help alleviate the resource- and time-investment issues associated with the typical intensive teaching protocols. For example, in contrast to the original applications involving two instructors working with a learner and teaching one skill for some 5 hours per day, only one instructor worked with a learner and teaching was carried out for a much shorter period of time. When considering the number of trials per week and the amount of time to conduct a trial, teaching time encompassed less than 1 hour per week per learner program. Hence, the modified teaching appeared applicable within the existing routine of the adult setting, with no apparent interference with other services.

Some disadvantages or limitations of the research also warrant attention. In particular, it cannot be determined which of the three modified teaching components were responsible for the behavior change. To illustrate, in Gabe's case, increased independence occurred immediately upon implementation of the intervention, and he reached criterion with the minimum number of sessions possible (three). Hence, the reduced distractions and/or change in consequence was likely responsible for the improvement in contrast to increased teaching trials. From a practical perspective, such an issue does not seem especially problematic in that the most time consuming component of modified teaching is increased teaching trials. If reduced distractions and/or change in consequence represent all that are needed for improvement, then many more teaching trials would not be needed. If the increased trials represent what is needed, then much time is not lost by changing the presumed reinforcer or reducing distractions. Nonetheless, it would still be helpful to determine when possible which component of modified teaching is needed to promote progress so that unnecessary strategies could be avoided.

An alternative to the modified teaching approach would be to train instructors to assess variables relating to the (non)effectiveness of specific instructional procedures (cf. Lerman, Vorndran, Addison, & Kuhn, 2004) and to modify the procedures accordingly. Such training, however, may prove formidable in a number of adult settings where personnel who carry out programs have minimal training in teaching procedures (Jahr, 1998).

On the other hand, it may be that simply ensuring staff use a potent reinforcer will overcome lack of progress in many cases. Hence, training more instructors to quickly assess reinforcers would appear useful (Roane, Vollmer, Ringdahl, & Marcus, 1998). Our plans were to conduct reinforcer assessments if progress did not occur with the teacher-selected, favorite stimuli. More rapid progress may have occurred if systematic assessments had been conducted. It is recommended that whenever possible, reinforcer assessments be conducted to maximize the likelihood that potent reinforcers will be incorporated within the teaching process.

In light of these results, along with the advantages and disadvantages of the modified teaching approach, and the characteristics of adult day programs, we offer the following suggestions for practitioners: Design teaching programs to include as many of the three components of the modified teaching approach as possible. From a practical perspective as well as recommended practice, the reduced-distraction and potent-reinforcer components should be a part of teaching procedures from their inception. If satisfactory progress does not result despite proficient implementation of the teaching programs, then increase the number of teaching trials at least three-fold beyond what usually occurs. If satisfactory progress still does not occur within a reasonable time period (participants in this investigation reached mastery in periods ranging from 3 to 23 teaching days), then conduct — or seek assistance to conduct — a more refined analysis of learner nonresponsiveness. The essential premise of this recommendation is that ineffective teaching programs should not continue week after week without program revisions. In this manner, adult learners will not remain on teaching programs for significantly extended time periods without making notable progress.

Footnotes

Requests for reprints should be addressed to Dennis H. Reid, Carolina Behavior Analysis and Support Center, P. O. Box 425, Morganton, NC 28680.

Contributor Information

Marsha B Parsons, J. Iverson Riddle Center, Morganton, North Carolina

Dennis H Reid, Carolina Behavior Analysis and Support Center.

Michaela Darden, J. Iverson Riddle Center

References

- Azrin N. H, Armstrong P. M. The “mini-meal” – A method for teaching eating skills to the profoundly retarded. Mental Retardation. 1973;11:9–11. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Azrin N. H, Foxx R. M. A rapid method of toilet training the institutionalized retarded. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis. 1971;4:89–99. doi: 10.1901/jaba.1971.4-89. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Azrin N. H, Schaeffer R. M, Wesolowski M. D. A rapid method of teaching profoundly retarded persons to dress by a reinforcement-guidance method. Mental Retardation. 1976;14:29–33. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bailey J. S. A futurist perspective for applied behavior analysis. In: Austin J, Carr J. E, editors. Handbook of applied behavior analysis. Reno, NV: Context Press; 2000. pp. 473–488. (Eds.) [Google Scholar]

- Bailey J. S, Burch M. R. Research methods in applied behavior analysis. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Conley R. W. Maryland issues in supported employment. Journal of Vocational Rehabilitation. 2007;24:137–144. [Google Scholar]

- Davis P. K, Young A, Cherry H, Dahman D, Rehfeldt R. A. Increasing the happiness of individuals with profound multiple disabilities: Replication and extension. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis. 2004;37:531–534. doi: 10.1901/jaba.2004.37-531. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Favell J. E, Realon R. E, Sutton K. A. Measuring and increasing the happiness of people with profound mental retardation and physical handicaps. Behavioral Interventions. 1996;11:47–58. [Google Scholar]

- Garcia-Iriarte E, Balcazar F, Taylor-Ritzler T. Analysis of case managers' support of youth with disabilities transitioning from school to work. Journal of Vocational Rehabilitation. 2007;26:129–140. [Google Scholar]

- Green C. W, Reid D. H. Defining, validating, and increasing indices of happiness among people with profound multiple disabilities. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis. 1996;29:67–78. doi: 10.1901/jaba.1996.29-67. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Green C. W, Reid D. H, Rollyson J. H, Passante S. C. An enriched teaching program for reducing resistance and indices of unhappiness among individuals with profound multiple disabilities. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis. 2005;38:221–233. doi: 10.1901/jaba.2005.4-04. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heller T, Miller A. B, Hsieh K, Sterns H. Later-life planning: Promoting knowledge of options and choice-making. Mental Retardation. 2000;38:395–406. doi: 10.1352/0047-6765(2000)038<0395:LPPKOO>2.0.CO;2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hieneman M, Dunlap G. Factors affecting the outcomes of community-based behavioral support: I. Identification and description of factor categories. Journal of Positive Behavior Interventions. 2000;2:161–169. [Google Scholar]

- Ivancic M. T. Stimulus preference and reinforcer assessment applications. In: Austin J, Carr J. E, editors. Handbook of applied behavior analysis. Reno, NV: Context Press; 2000. pp. 19–38. (Eds.) [Google Scholar]

- Ivancic M. T, Barrett G. T, Simonow A, Kimberly A. A replication to increase happiness indices among some people with profound multiple disabilities. Research in Developmental Disabilities. 1997;18:79–89. doi: 10.1016/s0891-4222(96)00039-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jahr E. Current issues in staff training. Research in Developmental Disabilities. 1998;19:73–87. doi: 10.1016/s0891-4222(97)00030-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lattimore L. P, Parsons M. B, Reid D. H. Enhancing job-site training of supported workers with autism: A reemphasis on simulation. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis. 2006;39:91–102. doi: 10.1901/jaba.2006.154-04. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lerman D. C, Vorndran C, Addison L, Kuhn S. A. C. A rapid assessment of skills in young children with autism. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis. 2004;37:11–26. doi: 10.1901/jaba.2004.37-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miltenberger R. G. Antecedent interventions for challenging behaviors maintained by escape from instructional activities. In: Luiselli J. K, editor. Antecedent assessment & intervention: Supporting children & adults with developmental disabilities in community settings. Baltimore: Brookes Publishing Company; 2006. pp. 101–124. (Ed.) [Google Scholar]

- Parsons M. B, Reid D. H. Training basic teaching skills to paraeducators of students with severe disabilities: A one-day program. Teaching Exceptional Children. 1999;31:48–54. doi: 10.1016/s0891-4222(96)00031-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parsons M. B, Reid D. H, Green C. W. Preparing direct service staff to teach people with severe disabilities: A comprehensive evaluation of an effective and acceptable training program. Behavioral Residential Treatment. 1993;8:163–186. [Google Scholar]

- Parsons M. B, Reid D. H, Green C. W. Training basic teaching skills to community and institutional support staff for people with severe disabilities: A one-day program. Research In Developmental Disabilities. 1996;17:467–485. doi: 10.1016/s0891-4222(96)00031-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parsons M. B, Rollyson J. H, Reid D. H. Improving day-treatment services for adults with severe disabilities: A norm-referenced application of outcome management. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis. 2004;37:365–377. doi: 10.1901/jaba.2004.37-365. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roane H. S, Vollmer T. R, Ringdahl J. E, Marcus B. A. Evaluation of a brief stimulus preference assessment. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis. 1998;31:605–620. doi: 10.1901/jaba.1998.31-605. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sharpton W. R, West M. D. Severe intellectual disability. In: Wehman P, McLaughlin P. J, Wehman T, editors. Intellectual and developmental disabilities: Toward full community inclusion. Austin, TX: Pro-ed; 2005. pp. 219–240. (Eds.) [Google Scholar]

- Sulzer-Azaroff B, Pollack M. J, Hamad C, Howley T. Promoting widespread, durable service quality via interlocking contingencies. Research in Developmental Disabilities. 1998;19:39–61. doi: 10.1016/s0891-4222(97)00028-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Symes M. D, Remington B, Brown T, Hastings R. P. Early intensive behavioral intervention for children with autism: Therapists' perspectives on achieving procedural fidelity. Research in Developmental Disabilities. 2006;27:30–42. doi: 10.1016/j.ridd.2004.07.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thompson J. R, Bryant B. R, Campbell E. M, Craig E. M, Hughes C. M, Rotholz D. A, et al. Supports intensity scale users manual. Washington, DC: American Association on Mental Retardation; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- West M, Hill J. W, Revell G, Smith G, Kregel J, Campbell L. Medicaid HCBS waivers and supported employment pre- and post-balanced budget act of 1997. Mental Retardation. 2002;40:142–147. doi: 10.1352/0047-6765(2002)040<0142:MHWASE>2.0.CO;2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- White J, Weiner J. S. Influence of least restrictive environment and community based training on integrated employment outcomes for transitioning students with severe disabilities. Journal of Vocational Rehabilitation. 2004;21:149–156. [Google Scholar]

- Williams W. L, DiVittorio T, Hausherr L. A description and extension of a human services management model. Journal of Organizational Behavior Management. 2002;22:47–71. [Google Scholar]