Summary

Meiosis is an integral part of sexual reproduction in eukaryotic species. It performs the dual functions of halving the genetic content in the cell, as well as increasing genetic diversity by promoting recombination between chromosome homologs. Despite extensive studies of meiosis in model yeast, it is now apparent that both the regulation of meiosis and the machinery mediating recombination has significantly diverged, even between closely related species. To highlight this, we discuss new studies on sex in Candida species, a diverse collection of hemiascomycetes that are related to S. cerevisiae and are important human pathogens. These provide new insights into the most conserved, as well as the most plastic, aspects of meiosis, meiotic recombination, and related parasexual processes.

Introduction

Sexual reproduction is a common attribute of eukaryotic species where it provides an adaptive advantage over species that are strictly asexual. During sex, fusion of gametes results in formation of cells with higher ploidy. Completion of sexual reproduction therefore requires a reductive DNA division, typically mediated by meiosis, in which diploid cells regenerate haploid gametes. Sexual reproduction evolved once very early in evolution in the eukaryotic lineage, and thus all asexual eukaryotes presumably derived from sexual ancestors [1].

Studies in yeast have played a central role in elucidating the regulation, machinery, and significance of sexual reproduction. In particular, experiments on the model ascomycetes, Saccharomyces cerevisiae and Schizosaccharomyces pombe, have detailed the molecular steps during mating and meiosis. However, despite the wealth of information obtained from these systems, it is now recognized that a surprising plasticity exists in sexual mechanisms from different species. We will review the meiotic programs of S. cerevisiae and S. pombe, and compare meiosis in these organisms with that recently described in Candida species. The latter are a diverse collection of hemiascomyces yeast related to S. cerevisiae, and are the most common cause of opportunistic fungal infections in humans. We emphasize differences in sexual differentiation between model and pathogenic yeast, and predict that additional surprises will emerge as genomic and functional studies are completed on these fungi that have important implications for human health.

Regulation of Meiosis in Model Yeast

S. cerevisiae and S. pombe show distinct meiotic programs, both in terms of their regulation and the physical structures underpinning nuclear division and recombination. Several reviews have discussed the regulation of meiosis [2–6], the role of cohesins [7,8], and the mechanism of meiotic recombination [9–12], and we will therefore provide a simplified overview.

Meiotic Entry in Budding Yeast

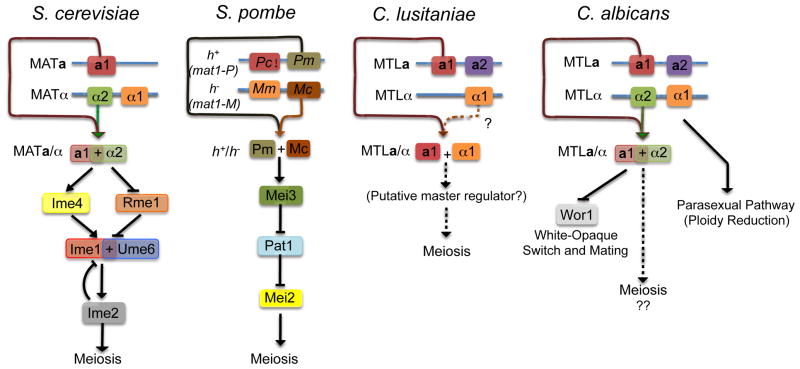

Mating in S. cerevisiae occurs between haploid a and α cells producing a/α diploids. The latter are unable to mate, but are competent to undergo meiosis and sporulation in response to environmental cues. A key transcriptional regulator mediating this cell-type specificity is the a1/α2 heterodimer that represses expression of mating genes [13,14]. In addition, a1/α2 inhibits expression of RME1, which itself encodes a negative regulator of meiosis (Table 1). RME1 plays an important role in preventing haploid a or α cells from initiating meiosis, a potentially catastrophic event [15]. The direct target of RME1 is IME1, which encodes a transcription factor that, in concert with Ume6, regulates downstream meiotic genes [16] (Figure 1). Multiple pathways converge on IME1 that are sensitive to cell type and nutritional signals. In particular, the IME4 gene is induced under starvation conditions and encodes an N6-methyladenosine activity that activates IME1, and potentially other targets, through modification of their mRNA [17,18]. More recently, it was shown that IME4 expression is also cell type regulated by a mechanism of transcriptional interference. Thus, haploid a or α cells produce an antisense RNA against IME4, whereas in a/α diploids expression of the antisense RNA is blocked by a1/α2, thereby enhancing expression of the sense RNA [19]. This demonstrates a novel mechanism by which cell type specificity in yeast is mediated by a noncoding RNA. Immediately downstream of Ime1 is Ime2, a serine-threonine kinase that positively regulates subsequent events in meiosis [2,20]. Ime2 also negatively regulates Ime1, targeting it for degradation, thereby restricting Ime1 to a narrow window of activity [22]. Profiling of synchronous meioses have revealed a cascade of sequential gene expression involving more than 1000 genes divided between seven temporal groups [23].

Table 1. List of Genes Regulating Meiosis and Sporulation in S. cerevisiae.

Genes involved in meiosis and sporulation in S. cerevisiae are listed, as well as homologous genes from C. lusitaniae and C. albicans genomes. Although a meiotic program has been identified in C. lusitaniae, functional tests of these putative meiosis genes have not been performed. In the case of C. albicans, a conventional meiosis has not been observed, and several genes that function in meiosis in S. cerevisiae have been shown to have an unrelated function in C. albicans. Homologous genes for C. albicans and C. lusitaniae were identified by the Broad Institute using reciprocal BLAST against S. cerevisiae meiotic and sporulation genes (www.broadinstitute.org). Absence of a homolog is designated as (− ) in this table.

| Genes Regulating Meiosis in S. cerevisiae | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Function of gene product in S. cerevisiae | S. cerevisiae | C. lusitaniae | C. albicans | Function of gene product in C. albicans |

| Homeodomain protein that acts with MATα2 to repress mating and permit meiotic induction in a/α diploids. | MATa1 | MTLa1 | MTLa1 | Homeodomain protein that acts with MTLα2 to repress white-phenotypic switching and mating in a/α opaque cells. |

| Homeodomain protein, promotes α–specific gene expression pattern. | MATα1 | CLUG04923 | MTLα1 | Homeodomain protein, promotes α-specific gene expression patterns. |

| Homeodomain protein, promotes α-specific gene expression and acts with MATa1 to repress mating and permit meiotic induction in a/α diploids. | MATα2 | - | MTLα2 | Homeodomain protein that acts with MTLa1 to repress white-opaque phenotypic switching and mating in a/α cells. |

| Cell type dependent meiotic repressor. | RME1 | CLUG05819 | orf19.4438 | White-phase specific gene expression. Upregulation correlates with clinical resistance to fluconazole, an antifungal. |

| Methlytransferase required for nutrient sensing and activation of IME1. | IME4 | CLUG03093 | orf19.1476 | No experimental data |

| Meiotic kinase required for sporulation and activation of IME1. | RIM11 | CLUG05114 CLUG01530 |

orf19.791 | No experimental data |

| Glucose repressed kinase, positive regulator of IME1. | RIM15 | CLUG04432 | orf19.7044 | No experimental data |

| Serine/threonine kinase important for meiotic entry and chromosome segregation. | MCK1 | CLUG01530 | orf19.3459 | No experimental data |

| Master transcription factor required for induction of the meiotic pathway. | IME1 | - | - | |

| Kinase required for activation of early meiosis genes. | IME2 | CLUG00015 | orf19.2395 | Mutants are hyper-susceptible to the antifungal Amphotericin B. |

| Transcription factor required for induction of middle-meiosis genes. | NDT80 | CLUG00404 CLUG05634 |

orf19.2119 (orf19.513) | Expression induced by antifungal treatment, required for basal level of antifungal drug tolerance in wild type cells. |

| Genes Involved in S. cerevisiae Sporulation | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Function in S. cerevisiae | S. cerevisiae | C. lusitaniae | C. albicans | Function in C. albicans. |

| Serine/threonine kinase involved with spore wall formation, expressed at the end of meiosis | SPS1 | CLUG04805 | orf19.3049 | No experimental data |

| Sporulation specific MAP kinase required for outer spore wall synthesis. | SMK1 | CLUG04129 | orf19.7208 | Putative MAP kinase, mutant produces wrinkled colonies. |

| Sporulation specific enzyme required for dityrosine synthesis, a cell wall precursor. | DIT1 | CLUG03886 | orf19.1741 | No experimental data |

| Sporulation specific enzyme required for dityrosine synthesis and cell wall maturation. | DIT2 | CLUG02306 | orf19.554 | Involved with chlamydospore (asexual spore) formation and dityrosine synthesis. |

| Sporulation specific septin. | SPR3 | CLUG04558 | orf19.1524 | Required for septin formation. |

| Non-essential protein expressed during sporulation. | SPS4 | CLUG05767 | orf19.7568 | No experimental data |

Figure 1. Regulation of Sexual Programs in Yeast.

Meiotic entry is induced by nutritional starvation and the presence of mating type alleles from both sexes for S. cerevisiae, S. pombe and C. lusitaniae. Note that meiosis in S. pombe requires all four genes encoded at the mating locus; Pm and Mc subsequently activate expression of the meiotic regulator, Mei3. Meiosis has recently been investigated in C. lusitaniae and requires the presence of a1, possibly in combination with α1, but the downstream effectors of meiosis have not been identified. C. albicans does not undergo a conventional meiosis yet efficient mating of diploid a and α strains occurs and is regulated by Wor1 and the white-opaque phenotypic switch. Tetraploid cells can undergo a parasexual program of random and concerted chromosome loss to return to the diploid state.

Meiotic Entry in Fission Yeast

Mating in S. pombe occurs under conditions of nutritional stress and generates diploid h+/h− zygotes. Co-operation of h+ and h− mating-type proteins (Mc and Pm) induces expression of the mei3 gene, initiating entry into meiosis [26]. Mc and Pm therefore provide cell-type specific regulation of meiosis analogous to that of a1/α2 in S. cerevisiae (Figure 1)[27]. Downstream of Mei3 there is a key interaction between Pat1, a serine/threonine kinase, and Mei2, an RNA-binding protein. Mei2 is a key factor for induction of meiosis, but is normally inhibited due to phosphorylation by Pat1 [28]. Inhibition is relieved upon expression of Mei3, which binds to Pat1 thereby inactivating it [29], although a Mei3-independent pathway may also exist for activation of meiosis [30]. Mei2 is essential for the initiation of meiosis and prevents the degradation of key meiosis-specific transcripts [31]. Transcriptional waves subsequently accompany progression through sporulation, and transcription factors have been identified that regulate specific stages including Rep1 (early genes), Mei4 (middle genes), and Atf21/Atf31 (late genes) [32,33]. Comparison of S. pombe and S. cerevisiae transcriptomes reveals relatively little overlap between species, although shared components include those of the anaphase-promoting complex and recombination/cohesin genes, such as REC8 and DMC1 [32].

Chromosome Pairing and Meiotic Recombination

The first DNA division in meiosis is reductional, with homologous chromosomes segregating from one another (meiosis I), while the second meiotic division is equational, with separation of sister chromatids (meiosis II). A conserved complex of cohesins holds sister chromatids together during meiosis I, possibly via a ring structure that encircles the chromatids [34]. In many eukaryotes, including S. cerevisiae and S. pombe, Rec8 provides meiosis-specific cohesin activity, and cleavage of this protein is necessary prior to separation of sister chromatids during meiosis II [35,36].

Meiotic recombination also plays an active role in pairing homologous chromosomes in yeast. Central to meiotic recombination is the formation and repair of DNA double-strand breaks (DSBs) introduced by the highly conserved Spo11 protein (Table 2) [9]. DSBs are subsequently processed by the MRX complex (Mre11-Rad50-Xrs2) into single-stranded DNA regions in preparation for strand exchange by the RecA homologs, Rad51 and Dmc1 [9,37]. Dmc1, in particular, is a meiosis-specific activity important for homologous recombination in many, but not all, eukaryotes [38]. Accessory factors act to promote DSB formation and strand exchange, although these factors tend to be poorly conserved or even species-specific [9,39].

Table 2. Meiotic Genes Involved in Homologous Recombination and Synaptonemal Complex Formation.

Homologs of S. cerevisiae genes required for homologous recombination and synaptonemal complex formation were compared across a subset of eukaryotic species. The presence of a gene homolog is designated by ( + ) and absence of a homolog by (−). Genes representing the best markers for predicting the presence of a meiotic pathway (“meiotic toolkit” genes, [52]) are also indicated ( * ). Note that S. pombe does not form synaptonemal complexes but uses linear elements that involve Rec8, Hop1, Hop2, Mek1, and Rec10 (homolog of S. cerevisiae Red1). C. lusitaniae demonstrates meiotic competence culminating in the formation of recombinant spores yet is lacking six of the eight meiotic toolkit genes, as well as homologs of most of the genes associated with synaptonemal complex/linear element formation.

| Genes Involved in Homologous Recombination | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Function of gene product in S. cerevisiae | S. cerevisiae | C. lusitaniae | C. albicans | S. pombe | M. musculus |

| Meiosis specific gene, important for processing dsDNA breaks for repair during homologous recombination. | DMC1* | − | + | + | + |

| Dmc1 cofactor; forms a complex with Sae3 for dsDNA break processing during homologous recombination. | MEI5 | − | + | + | + |

| Meiosis specific helicase. | MER3/HFM1 | − | + | − | + |

| Mismatch repair gene that is important for DNA crossover during meiosis. | MLH1 | + | + | + | + |

| Endonuclease that complexes with MUS81 to cleave branched DNA; involved in joint molecule formation/resolution during recombination. | MMS4 | + | + | + | + |

| Forms a complex with HOP1, important for chromosome pairing and repair of dsDNA breaks. | MND1* | − | + | + | + |

| Subunit of MRX complex, required for dsDNA break repair during homologous recombination. | MRE11 | + | + | + | + |

| Forms a complex with MSH5, essential for regulating crossover events during meiosis. | MSH4* | − | + | − | + |

| Forms a complex with MSH4, essential for regulating crossover events during meiosis. | MSH5* | − | + | − | + |

| Endonuclease that complexes with MMS4 to cleave branched DNA; involved in joint molecule formation/resolution during recombination. | MUS81 | + | + | + | + |

| Subunit of MRX complex, required for dsDNA break repair during homologous recombination. | RAD50 | + | + | + | + |

| Meiotic protein important for strand invasion and exchange during homologous recombination. | RAD51 | + | + | + | + |

| Meiotic protein that stimulates strand exchange during homologous recombination. | RAD52 | + | + | + | + |

| Dmc1 cofactor; forms a complex with Mei5 for dsDNA break processing during homologous recombination. | SAE3 | − | + | + | + |

| Helicase, regulates meiotic crossover formation events. | SGS1 | + | + | + | + |

| Meiosis specific protein that stimulates homologous recombination by catalyzing the formation of dsDNA breaks. | SPO11* | + | + | + | + |

| Component of the MRX complex, important for dsDNA repair during homologous recombination. | XRS2 (NBS1) | − | − | + | + |

| Synaptonemal Complex Genes. | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Function of gene product in S. cerevisiae | S. cerevisiae | C. lusitaniae | C. albicans | S. pombe | M. musculus |

| Meiosis specific protein, localizes to axial elements of the synaptonemal complex. Required for homologous recombination. | HOP1* | − | + | + | + |

| Meiosis protein that promotes recombination between homologous chromosomes and prevents recombination between non- homologous chromosomes. | HOP2* | − | + | + | + |

| Meiosis specific serine/threonine kinase that promotes recombination between homologous chromosomes. | MEK1 | − | + | + | + |

| Sister chromatid cohesin protein. | REC8* | + | + | + | + |

| Protein component of axial element in the synaptonemal complex. | RED1 | − | − | + | + |

| Structural component of synaptonemal complex, promotes recombination between homologs. | ZIP1 | − | − | − | + |

| Meiosis specific protein important for synaptonemal complex formation. | ZIP2 | − | + | − | + |

| Sumo E3 ligase, localizes to synapse initiation sites and is required for synaptonemal complex formation. | ZIP3 | − | + | − | + |

| Meiosis specific gene essential for synapsis during homologous recombination. | ZIP4 | − | − | − | − |

Higher order structures mediate meiotic chromosome segregation in both S. cerevisiae and S. pombe. In S. cerevisiae, as in most other eukaryotes, synaptonemal complexes (SC) are formed during meiosis and these proteinaceous structures facilitate pairing of homologous chromosomes [40]. A number of proteins are implicated in SC formation including the ZMM (Zip1-Zip4, Msh4/Msh5 and Mer3) family of proteins [11,40], which play a structural role in the SC (particularly Zip1) while also directing the program of genetic recombination. Thus, ZMM proteins promote the processing of meiotic DSBs into crossover events (where there is an exchange of flanking markers) rather than noncrossover events [41,42]. In contrast, meiosis in S. pombe does not involve SC formation, although minimal structures (linear elements) support pairing of homologous chromosomes. These structures share some components with the SC (Table 2), but are not essential for meiotic recombination [8,43].

Sex and Meiosis in Candida species

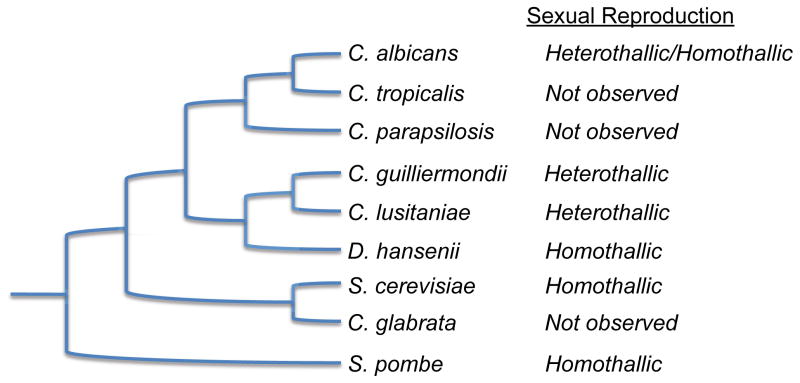

Species belonging to the Candida genus were historically classified as budding yeast that were asexual and formed either pseudohyphae or true hyphae [44]. Many of these species are human pathogens and cluster in a single clade within the hemiascomycetes (Figure 2)[45,46]. Sexual lifestyles have now been confirmed for several Candida species and these reveal a surprising diversity in their programs. Thus, C. glabrata, C. parapsilosis, and C. tropicalis have many of the genes necessary for mating and meiosis, and yet sex has never been observed in these species [45]. In contrast, C. lusitaniae and C. guilliermondii have established sexual cycles including sporulation and ascospore formation [44]. C. albicans is somewhere between these two extremes; efficient mating occurs but a conventional meiosis has yet to be demonstrated [47–50]. Molecular studies of sexual differentiation in C. lusitaniae and C. albicans have now been completed, and these will be contrasted with those in model yeast.

Figure 2. Phylogeny of Sequenced Candida Species.

Phylogenetic tree of the hemiascomycetes (S. cerevisiae and sequenced Candida species) as well as the related ascomycete, S. pombe. Heterothallic organisms are out-crossing species, whereas homothallic organisms are self-fertile. Note that C. albicans exhibits both homothallic and heterothallic modes of reproduction, but undergoes a parasexual cycle rather than a conventional meiosis. Most natural isolates of S. cerevisiae are homothallic although heterothallic isolates have also been described. Figure adapted from the Broad Institute (www.broadinstitute.org).

Sexual Reproduction in Candida lusitaniae

C. lusitaniae exhibits a surprisingly efficient program of meiosis and sporulation given that this species is lacking many ‘key’ meiotic components [51]. Missing factors include the recombinase Dmc1, synaptonemal complex proteins Zip1-Zip4, as well as activities that promote crossover formation (Msh4/Msh5 and Mer3). In fact, C. lusitaniae is missing most of the top candidate genes identified as hallmarks of meiosis and sexual reproduction in eukaryotic species (the ‘meiotic toolkit’ genes, Table 2)[52]. Despite the loss of these factors, C. lusitaniae undergoes Spo11-mediated meiotic recombination at frequencies similar to that of other sexual fungi [51]. The lack of conserved SC components suggests that meiosis may involve minimal structures for chromosome pairing similar to S. pombe. However, while a homolog of Rec8 is present in C. lusitaniae, other factors such as Hop1 and Mek1 that contribute to linear elements in S. pombe are missing [8,43,45]. It therefore appears that very rudimentary structures mediate chromosome pairing and recombination during C. lusitaniae meiosis.

Sexual differentiation in C. lusitaniae is also unusual in that, unlike the related hemiascomycete S. cerevisiae, it is no longer under control of the a1/α2 complex. C. lusitaniae has retained the a1 gene, and this gene is necessary for meiosis and sporulation, but the α2 gene is missing from the sequenced MTLα locus (Figure 1) [45,51]. Presumably, another α-specific gene is required for determining cell type as only a/α (not a/a or α/α diploids sporulate. One candidate is the α1 gene, although how a1 cooperates with α1 to specify cell type and promote meiosis is an intriguing question for the future. Furthermore, while C. lusitaniae contains homologs of many regulatory factors involved in meiosis (including IME2, IME4, RME1, and NDT80) there is no homolog of IME1, the master regulator in S. cerevisiae (Table 2) [45,51]. The transcriptional circuitry regulating meiosis has therefore diverged since S. cerevisiae and C. lusitaniae last shared a common ancestor. Similar rewiring of the mating type circuitry has also occurred between S. cerevisiae and the Candida species [53–55], again illustrating the highly plastic nature of sexual processes.

Sexual reproduction C. lusitaniae involves a haploid-diploid-haploid cycle similar to that in model yeast. Surprisingly, however, while the products of meiosis are mainly haploid, about one-third of meiotic products are diploid or aneuploid [51]. The latter may be due to inefficient chromosome segregation and meiotic nondisjunction, particularly given the limited repertoire of meiotic components present in the C. lusitaniae genome. Interestingly, similar levels of aneuploidy (7–35%) also occur during human oogenesis and can lead to miscarriage and birth defects [56], although it is not clear what consequences aneuploidy may have for C. lusitaniae biology. In addition, C. lusitaniae asci typically contain two ascospores (dyads) rather than four ascospores (tetrads) as often formed during meiosis in S. cerevisiae and S. pombe. Chromosome missegregation during C. lusitaniae meiosis could generate many non-viable forms, and reducing the number of spores may help limit investment in dead-end products [51]. A parallel exists with S. cerevisiae, as meiosis performed in limiting acetate conditions produces dyads rather than tetrads, again preserving cell resources while allowing sporulation to proceed [57–59]. In this case, unpackaged nuclei get degraded during ascus maturation leaving two intact, haploid ascospores.

Parasexual Reproduction in Candida albicans

In contrast to C. lusitaniae, which is rarely encountered in the clinic, C. albicans is a prevalent human pathogen that causes both mucosal and systemic infections [60]. Despite its clinical importance, the sexual lifestyle of C. albicans has remained an enigma. Long thought to be an obligate asexual organism, mating of diploid strains has been demonstrated both in vitro and in vivo, and is regulated by a unique mechanism of phenotypic switching [48–50,61]. MTLa and MTLα cells can switch between white and opaque forms, but only cells in the opaque state are competent for mating [50]. The key regulator of the opaque state is Wor1, as high levels of this protein are sufficient to drive cells to the opaque form, although a complex network of positive and negative feedback loops regulates heritable Wor1 expression [61]. White-opaque switching is inhibited in a/α cells as the a1/α2 complex represses expression of the WOR1 gene, locking cells in the white state (Figure 1)[50]. The white-opaque switch therefore adds an additional layer of sophistication to C. albicans mating, presumably to regulate sexual reproduction in response to environmental cues from the mammalian host or other, yet to be discovered, niches.

Despite efficient mating between opaque a and α cells, and the presence of many ‘meiosis-specific’ genes in the sequenced genome (Table 2), a conventional meiosis has yet to be uncovered in C. albicans [45,62]. In its place, a parasexual mechanism has been described involving efficient and cooperative chromosome loss [63]. Thus, culture of tetraploids on certain laboratory media causes genomic instability and loss of chromosomes from the tetraploid, resulting in the formation of diploid (and numerous aneuploid) forms of C. albicans [63,64]. One potential advantage of the parasexual program over a traditional meiosis is that it does not culminate in the production of spores. This may be significant given that spores are often highly antigenic and could therefore minimize detection of mating products by the host immune system [65].

Despite the apparent absence of a conventional meiosis in C. albicans, several meiosis-specific genes have been shown to encode functional products. For example, a homolog of Dmc1 is present in C. albicans and can successfully substitute for S. cerevisiae Dmc1 function in meiosis [66]. In addition, Spo11 is required for the initiation of meiotic recombination in many eukaryotes, and was recently implicated in mediating recombination during the parasexual cycle of C. albicans [64]. It therefore remains to be seen whether other meiosis-specific genes have also been reprogrammed to function in the parasexual program. If so, the parasexual cycle may represent a bona fide alternative to a conventional meiosis. Alternatively, the parasexual cycle may simply signify a particularly inefficient meiosis, especially given the high rates of aneuploidy now reported during meiosis in C. lusitaniae [51]. Finally, an exciting possibility is that a cryptic meiosis still exists for C. albicans, and that the appropriate conditions have not been identified to initiate this program. In this regard, it is interesting to note that a novel mode of same-sex mating has recently been demonstrated for C. albicans [67]. While the products of same-sex mating can undergo the parasexual pathway, further experimentation will determine if a conventional meiosis/sporulation can be performed by these cells.

Conclusions

An emerging theme is that programs of sexual reproduction exhibit a remarkable degree of plasticity. This is particularly true of meiosis, where recent genomic and functional studies have revealed marked differences even between closely related species. Thus, while much has been learned about sexual reproduction from studies in model yeast, it is now apparent that differences between species are likely to be almost as striking as the similarities. A striking example of this sexual diversity is provided by C. lusitaniae, which is able to undergo efficient sporulation and homologous recombination yet is apparently lacking much of the molecular machinery associated with meiosis in other organisms. Additional studies will be necessary to reveal how this is achieved with such a limited repertoire of meiotic components.

Finally, while we have focused on recent experiments in Candida, exciting developments have been made concerning sex and meiosis in other pathogenic fungi. In particular, a complete sexual cycle has now been demonstrated for Aspergillus neoformans [68], the most prevalent airbourne fungal pathogen, and novel modes of same-sex mating and meiosis have been shown to occur during ‘haploid fruiting’ in Cryptococcus neoformans [69], a causative agent of meningoencephalitis. As additional genomes are sequenced, the ability to analyze the role of putative mating and meiosis genes will accelerate, and will undoubtedly lead to a clearer picture of the evolution and consequences of sex in fungi and higher eukaryotes.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Kevin Alby for discussions and reading of the manuscript. We apologize to authors whose work could not be cited due to space restrictions. RS was supported by an F31 predoctoral fellowship (#F31 AI075607-02) from the NIH. RJB holds an investigator in the Pathogenesis of Infectious Disease Award from the Burroughs Wellcome Fund. This work was also supported by the NIH (R21 AI081560).

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Ramesh MA, Malik SB, Logsdon JM., Jr A phylogenomic inventory of meiotic genes; evidence for sex in Giardia and an early eukaryotic origin of meiosis. Curr Biol. 2005;15:185–191. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2005.01.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kassir Y, Adir N, Boger-Nadjar E, Raviv NG, Rubin-Bejerano I, Sagee S, Shenhar G. Transcriptional regulation of meiosis in budding yeast. Int Rev Cytol. 2003;224:111–171. doi: 10.1016/s0074-7696(05)24004-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Mitchell AP. Control of meiotic gene expression in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Microbiol Rev. 1994;58:56–70. doi: 10.1128/mr.58.1.56-70.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Davey J. Fusion of a fission yeast. Yeast. 1998;14:1529–1566. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-0061(199812)14:16<1529::AID-YEA357>3.0.CO;2-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Yamamoto M. The molecular control mechanisms of meiosis in fission yeast. Trends Biochem Sci. 1996;21:18–22. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Harigaya Y, Yamamoto M. Molecular mechanisms underlying the mitosis-meiosis decision. Chromosome Res. 2007;15:523–537. doi: 10.1007/s10577-007-1151-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sakuno T, Watanabe Y. Studies of meiosis disclose distinct roles of cohesion in the core centromere and pericentromeric regions. Chromosome Res. 2009;17:239–249. doi: 10.1007/s10577-008-9013-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wells JL, Pryce DW, McFarlane RJ. Homologous chromosome pairing in Schizosaccharomyces pombe. Yeast. 2006;23:977–989. doi: 10.1002/yea.1403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Keeney S. Spo11 and the formation of DNA double-strand breaks in meiosis. In: Lankenau D, editor. Recombination and Meiosis. Vol. 2 Springer; Berlin/Heidelberg: 2007. Genome Dynamics and Stability. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Symington LS. Role of RAD52 epistasis group genes in homologous recombination and double-strand break repair. Microbiol Mol Biol Rev. 2002;66:630–670. doi: 10.1128/MMBR.66.4.630-670.2002. table of contents. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lynn A, Soucek R, Borner GV. ZMM proteins during meiosis: Crossover artists at work. Chromosome Res. 2007;15:591–605. doi: 10.1007/s10577-007-1150-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Cromie GA, Smith GR. Branching out: meiotic recombination and its regulation. Trends Cell Biol. 2007;17:448–455. doi: 10.1016/j.tcb.2007.07.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Galgoczy DJ, Cassidy-Stone A, Llinas M, O’Rourke SM, Herskowitz I, DeRisi JL, Johnson AD. Genomic dissection of the cell-type-specification circuit in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2004;101:18069–18074. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0407611102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sprague GFJ, Thorner JT. Pheromone Response and Signal Transduction during the Mating Process of S. cerevisiae. In: Pringle JR, Broach JR, Jones EW, editors. Molecular and Cellular Biology of the Yeast Saccharomyces. CSH Laboratory Press; 1992. pp. 657–744. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Mitchell AP, Herskowitz I. Activation of meiosis and sporulation by repression of the RME1 product in yeast. Nature. 1986;319:738–742. doi: 10.1038/319738a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bowdish KS, Yuan HE, Mitchell AP. Positive control of yeast meiotic genes by the negative regulator UME6. Mol Cell Biol. 1995;15:2955–2961. doi: 10.1128/mcb.15.6.2955. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Clancy MJ, Shambaugh ME, Timpte CS, Bokar JA. Induction of sporulation in Saccharomyces cerevisiae leads to the formation of N6-methyladenosine in mRNA: a potential mechanism for the activity of the IME4 gene. Nucleic Acids Res. 2002;30:4509–4518. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkf573. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Shah JC, Clancy MJ. IME4, a gene that mediates MAT and nutritional control of meiosis in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Mol Cell Biol. 1992;12:1078–1086. doi: 10.1128/mcb.12.3.1078. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19*.Hongay CF, Grisafi PL, Galitski T, Fink GR. Antisense transcription controls cell fate in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Cell. 2006;127:735–745. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2006.09.038. The IME4 gene is a key regulator of entry into meiosis in S. cerevisiae. This paper shows that expression of the IME4 gene transcript is suppressed in haploid cells via an antisense transcript from the same gene. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Yoshida M, Kawaguchi H, Sakata Y, Kominami K, Hirano M, Shima H, Akada R, Yamashita I. Initiation of meiosis and sporulation in Saccharomyces cerevisiae requires a novel protein kinase homologue. Mol Gen Genet. 1990;221:176–186. doi: 10.1007/BF00261718. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Smith HE, Mitchell AP. A transcriptional cascade governs entry into meiosis in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Mol Cell Biol. 1989;9:2142–2152. doi: 10.1128/mcb.9.5.2142. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Guttmann-Raviv N, Martin S, Kassir Y. Ime2, a meiosis-specific kinase in yeast, is required for destabilization of its transcriptional activator, Ime1. Mol Cell Biol. 2002;22:2047–2056. doi: 10.1128/MCB.22.7.2047-2056.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Chu S, DeRisi J, Eisen M, Mulholland J, Botstein D, Brown PO, Herskowitz I. The transcriptional program of sporulation in budding yeast. Science. 1998;282:699–705. doi: 10.1126/science.282.5389.699. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Xu L, Ajimura M, Padmore R, Klein C, Kleckner N. NDT80, a meiosis-specific gene required for exit from pachytene in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Mol Cell Biol. 1995;15:6572–6581. doi: 10.1128/mcb.15.12.6572. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Horie S, Watanabe Y, Tanaka K, Nishiwaki S, Fujioka H, Abe H, Yamamoto M, Shimoda C. The Schizosaccharomyces pombe mei4+ gene encodes a meiosis-specific transcription factor containing a forkhead DNA-binding domain. Mol Cell Biol. 1998;18:2118–2129. doi: 10.1128/mcb.18.4.2118. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.McLeod M, Stein M, Beach D. The product of the mei3+ gene, expressed under control of the mating-type locus, induces meiosis and sporulation in fission yeast. EMBO J. 1987;6:729–736. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1987.tb04814.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Van Heeckeren WJ, Dorris DR, Struhl K. The mating-type proteins of fission yeast induce meiosis by directly activating mei3 transcription. Mol Cell Biol. 1998;18:7317–7326. doi: 10.1128/mcb.18.12.7317. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Watanabe Y, Shinozaki-Yabana S, Chikashige Y, Hiraoka Y, Yamamoto M. Phosphorylation of RNA-binding protein controls cell cycle switch from mitotic to meiotic in fission yeast. Nature. 1997;386:187–190. doi: 10.1038/386187a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.McLeod M, Beach D. A specific inhibitor of the ran1+ protein kinase regulates entry into meiosis in Schizosaccharomyces pombe. Nature. 1988;332:509–514. doi: 10.1038/332509a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kjaerulff S, Lautrup-Larsen I, Truelsen S, Pedersen M, Nielsen O. Constitutive activation of the fission yeast pheromone-responsive pathway induces ectopic meiosis and reveals ste11 as a mitogen-activated protein kinase target. Mol Cell Biol. 2005;25:2045–2059. doi: 10.1128/MCB.25.5.2045-2059.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31*.Harigaya Y, Tanaka H, Yamanaka S, Tanaka K, Watanabe Y, Tsutsumi C, Chikashige Y, Hiraoka Y, Yamashita A, Yamamoto M. Selective elimination of messenger RNA prevents an incidence of untimely meiosis. Nature. 2006;442:45–50. doi: 10.1038/nature04881. This paper reveals that MEI2, a master regulator of meiosis in S. pombe, acts by preventing the degradation of meiosis-specific transcripts by the DSR-Mmi1 system. These results provide a striking example of the surprising complexity in mechanisms regulating meiosis in eukaroytes. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Mata J, Lyne R, Burns G, Bahler J. The transcriptional program of meiosis and sporulation in fission yeast. Nat Genet. 2002;32:143–147. doi: 10.1038/ng951. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Mata J, Wilbrey A, Bahler J. Transcriptional regulatory network for sexual differentiation in fission yeast. Genome Biol. 2007;8:R217. doi: 10.1186/gb-2007-8-10-r217. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Haering CH, Farcas AM, Arumugam P, Metson J, Nasmyth K. The cohesin ring concatenates sister DNA molecules. Nature. 2008;454:297–301. doi: 10.1038/nature07098. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Klein F, Mahr P, Galova M, Buonomo SB, Michaelis C, Nairz K, Nasmyth K. A central role for cohesins in sister chromatid cohesion, formation of axial elements, and recombination during yeast meiosis. Cell. 1999;98:91–103. doi: 10.1016/S0092-8674(00)80609-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Watanabe Y, Nurse P. Cohesin Rec8 is required for reductional chromosome segregation at meiosis. Nature. 1999;400:461–464. doi: 10.1038/22774. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Gerton JL, Hawley RS. Homologous chromosome interactions in meiosis: diversity amidst conservation. Nat Rev Genet. 2005;6:477–487. doi: 10.1038/nrg1614. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Neale MJ, Keeney S. Clarifying the mechanics of DNA strand exchange in meiotic recombination. Nature. 2006;442:153–158. doi: 10.1038/nature04885. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Richard GF, Kerrest A, Lafontaine I, Dujon B. Comparative genomics of hemiascomycete yeasts: genes involved in DNA replication, repair, and recombination. Mol Biol Evol. 2005;22:1011–1023. doi: 10.1093/molbev/msi083. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Page SL, Hawley RS. The genetics and molecular biology of the synaptonemal complex. Annu Rev Cell Dev Biol. 2004;20:525–558. doi: 10.1146/annurev.cellbio.19.111301.155141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Borner GV, Kleckner N, Hunter N. Crossover/noncrossover differentiation, synaptonemal complex formation, and regulatory surveillance at the leptotene/zygotene transition of meiosis. Cell. 2004;117:29–45. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(04)00292-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Mazina OM, Mazin AV, Nakagawa T, Kolodner RD, Kowalczykowski SC. Saccharomyces cerevisiae Mer3 helicase stimulates 3′–5′ heteroduplex extension by Rad51; implications for crossover control in meiotic recombination. Cell. 2004;117:47–56. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(04)00294-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Loidl J. S. pombe linear elements: the modest cousins of synaptonemal complexes. Chromosoma. 2006;115:260–271. doi: 10.1007/s00412-006-0047-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Heitman J, Kronstad JW, Taylor JW, Casselton LA. Sex in Fungi. Washington: ASM Press; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 45**.Butler G, Rasmussen MD, Lin MF, Santos MA, Sakthikumar S, Munro CA, Rheinbay E, Grabherr M, Forche A, Reedy JL, et al. Evolution of pathogenicity and sexual reproduction in eight Candida genomes. Nature. 2009;459:657–662. doi: 10.1038/nature08064. Genomic analysis of multiple Candida species demonstrated that there is an enormous diversity between their programs of sexual reproduction. In particular, the configuration of the mating type locus is highly variable, and many of the genes necessary for meiosis in S. cerevisiae are absent from the Candida species. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Diezmann S, Cox CJ, Schonian G, Vilgalys RJ, Mitchell TG. Phylogeny and evolution of medical species of Candida and related taxa: a multigenic analysis. J Clin Microbiol. 2004;42:5624–5635. doi: 10.1128/JCM.42.12.5624-5635.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Bennett RJ, Johnson AD. Mating in Candida albicans and the Search for a Sexual Cycle. Annu Rev Microbiol. 2005;59:233–255. doi: 10.1146/annurev.micro.59.030804.121310. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Hull CM, Raisner RM, Johnson AD. Evidence for mating of the “asexual” yeast Candida albicans in a mammalian host. Science. 2000;289:307–310. doi: 10.1126/science.289.5477.307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Magee BB, Magee PT. Induction of mating in Candida albicans by construction of MTLa and MTLalpha strains. Science. 2000;289:310–313. doi: 10.1126/science.289.5477.310. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Miller MG, Johnson AD. White-opaque switching in Candida albicans is controlled by mating-type locus homeodomain proteins and allows efficient mating. Cell. 2002;110:293–302. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(02)00837-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51**.Reedy JL, Floyd AM, Heitman J. Mechanistic plasticity of sexual reproduction and meiosis in the Candida pathogenic species complex. Curr Biol. 2009;19:891–899. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2009.04.058. This paper reports the first detailed study of sexual reproduction in Candida lusitaniae. The authors demonstrate that, despite lacking many key meiosis genes, this species undergoes efficient meiosis and sporulation, and that genetic recombination is mediated by Spo11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52*.Schurko AM, Logsdon JM., Jr Using a meiosis detection toolkit to investigate ancient asexual “scandals” and the evolution of sex. Bioessays. 2008;30:579–589. doi: 10.1002/bies.20764. The presence of a core set of eight highly conserved meiosis-specific genes is proposed as evidence that a species is capable of undergoing sexual reproduction. However, several Candida species are lacking many of these ‘key’ meiotic components. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Tsong AE, Miller MG, Raisner RM, Johnson AD. Evolution of a combinatorial transcriptional circuit: a case study in yeasts. Cell. 2003;115:389–399. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(03)00885-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Tsong AE, Tuch BB, Li H, Johnson AD. Evolution of alternative transcriptional circuits with identical logic. Nature. 2006;443:415–420. doi: 10.1038/nature05099. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Butler G, Kenny C, Fagan A, Kurischko C, Gaillardin C, Wolfe KH. Evolution of the MAT locus and its Ho endonuclease in yeast species. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2004;101:1632–1637. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0304170101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Hunt PA, Hassold TJ. Human female meiosis: what makes a good egg go bad? Trends Genet. 2008;24:86–93. doi: 10.1016/j.tig.2007.11.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Knop M. Evolution of the hemiascomycete yeasts: on life styles and the importance of inbreeding. Bioessays. 2006;28:696–708. doi: 10.1002/bies.20435. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Taxis C, Keller P, Kavagiou Z, Jensen LJ, Colombelli J, Bork P, Stelzer EH, Knop M. Spore number control and breeding in Saccharomyces cerevisiae: a key role for a self-organizing system. J Cell Biol. 2005;171:627–640. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200507168. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Neiman AM. Ascospore formation in the yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Microbiol Mol Biol Rev. 2005;69:565–584. doi: 10.1128/MMBR.69.4.565-584.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Pfaller MA, Diekema DJ. Epidemiology of invasive candidiasis: a persistent public health problem. Clin Microbiol Rev. 2007;20:133–163. doi: 10.1128/CMR.00029-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61*.Zordan RE, Miller MG, Galgoczy DJ, Tuch BB, Johnson AD. Interlocking Transcriptional Feedback Loops Control White-Opaque Switching in Candida albicans. PLoS Biol. 2007;5:e256. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.0050256. The white-opaque switch regulates entry into the program of sexual reproduction in C. albicans, as only opaque cells are mating-competent. This paper reveals how a series of positive and negative feedback loops regulates bistability and inheritance of the white and opaque states. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Tzung KW, Williams RM, Scherer S, Federspiel N, Jones T, Hansen N, Bivolarevic V, Huizar L, Komp C, Surzycki R, et al. Genomic evidence for a complete sexual cycle in Candida albicans. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2001;98:3249–3253. doi: 10.1073/pnas.061628798. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Bennett RJ, Johnson AD. Completion of a parasexual cycle in Candida albicans by induced chromosome loss in tetraploid strains. Embo J. 2003;22:2505–2515. doi: 10.1093/emboj/cdg235. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64*.Forche A, Alby K, Schaefer D, Johnson AD, Berman J, Bennett RJ. The parasexual cycle in Candida albicans provides an alternative pathway to meiosis for the formation of recombinant strains. PLoS Biol. 2008;6:e110. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.0060110. This paper shows that the parasexual cycle in C. albicans generates recombinant forms of the organism, and that the Spo11 protein is implicated in these parasexual recombination events. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Nielsen K, Heitman J. Sex and virulence of human pathogenic fungi. Adv Genet. 2007;57:143–173. doi: 10.1016/S0065-2660(06)57004-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Diener AC, Fink GR. DLH1 is a functional Candida albicans homologue of the meiosis-specific gene DMC1. Genetics. 1996;143:769–776. doi: 10.1093/genetics/143.2.769. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Alby K, Schaefer D, Bennett RJ. Homothallic and Heterothallic Mating in the Opportunistic Pathogen Candida albicans. Nature. 2009;460:890–894. doi: 10.1038/nature08252. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68*.O’Gorman CM, Fuller HT, Dyer PS. Discovery of a sexual cycle in the opportunistic fungal pathogen Aspergillus fumigatus. Nature. 2009;457:471–474. doi: 10.1038/nature07528. This paper provides the first demonstration of a complete sexual cycle in this important human pathogen. These results also provide hope that sex will eventually be identified in other fungi, particularly given that almost one-fifth of all fungi have no recognized sexual stage. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Lin X, Hull CM, Heitman J. Sexual reproduction between partners of the same mating type in Cryptococcus neoformans. Nature. 2005;434:1017–1021. doi: 10.1038/nature03448. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]