A 19-year-old South African white male with a medical history of intermittent migraines, presented with a headache. The patient developed tongue paresthesias, progressive numbness, difficulty blinking, and then, complete right facial hemiparesis. Work-up at an emergency department showed a normal complete blood count, metabolic panel, sedimentation rate, a negative rapid plasma regain, and Lyme disease titer. He was diagnosed with Bell’s Palsy and was discharged with prednisone, acyclovir, and analgesics.

Over the next few weeks, the right-sided facial paralysis resolved, but his occipital headaches and posterior neck aches persisted. Three weeks after initial presentation, a brain magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) scan showed uniform enhancement and a soft tissue mass measuring 9 × 4 mm mass extending along the length of the right auditory canal consistent with a facial or acoustic neuroma. The area of enhancement extended from the porus acousticus to the apex of the internal auditory canal. No other abnormalities were noted. The patient was diagnosed with an acoustic neuroma and referred to the Radiation Oncology Department for stereotactic radiation therapy.

At that time, the patient’s main complaint was subjective residual right-sided weakness while blinking, fatigue, morning headache, and intermittent lightheadedness. His review of systems was positive only for a very mild, persistent dry cough subsequent to the development of the right-sided facial weakness. His physical examination did not reveal any localizing neurologic deficits.

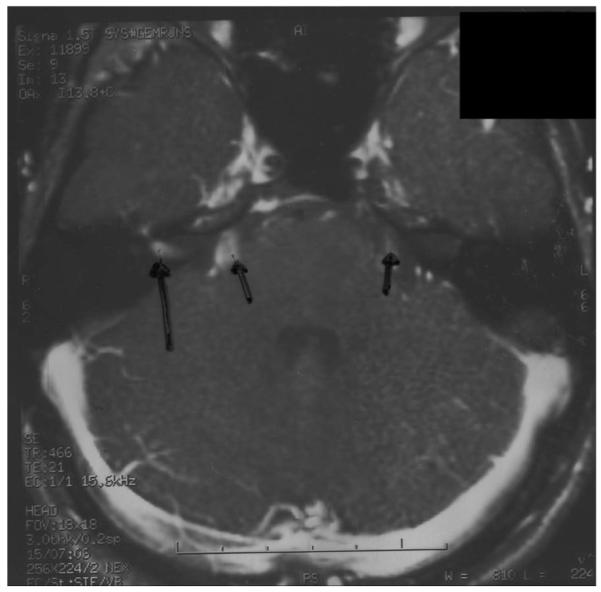

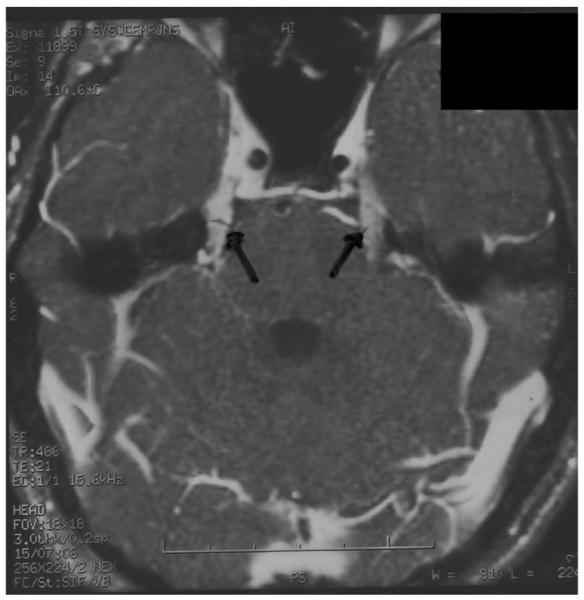

Our review of the MRI (Figs. 1 and 2) showed the mass in the area of the porus acousticus and additional enhancement of the cavernous sinus, its associated cranial nerves, and both trigeminal nerves. Given these findings, the patient was referred for a lumbar puncture. Cerebrospinal fluid analysis showed normal glucose and angiotensin converting enzyme levels, and no monoclonal paraprotein spike. These tests showed elevated immunoglobulin G percent and elevated protein. Serum testing was negative for Venereal Disease Research Laboratory, monoclonal paraprotein spike, myelin basic protein, and bacterial growth.

FIGURE 1.

MRI illustrating an abnormality in the cerebellopontine angle in the region of the seventh and eighth nerve (large arrow) and bilateral trigeminal nerve thickening (shorter arrows).

FIGURE 2.

MRI illustrating an abnormality in the cerebellopontine angle in the region of the seventh and eighth nerve (large arrow) and bilateral trigeminal nerve thickening (shorter arrows).

Bell’s Palsy is an abrupt, isolated, unilateral, peripheral nerve paralysis without an identifiable cause.1,2 Generally speaking, Bell’s Palsy can be broadly divided into 3 etiologies: oncologic, autoimmune, and infectious (Table 1).3 In our minds, the strongest diagnostic possibilities were infectious meningitis or neoplastic (facial neuroma vs. acoustic neuroma).

TABLE 1.

Causes of Bell’s Palsy

| Infectious | Autoimmune | Oncologic | Other |

|---|---|---|---|

| Lyme disease | Guillain-Barré syndrome | Parotid gland tumor | Thyroid dysfunction (both hyper- and hypo-) |

| HIV/AIDS infection | Graves’ disease | A skull base tumor | Myxedema coma |

| Aseptic meningitis | Multiple sclerosis | Leukemic meningitis | Ischemic stroke |

| Herpes simplex encephalitis | Carcinomatous meningitis | Melkersson-Rosenthal syndrome | Hemorrhagic stroke |

| Herpes zoster oticus | Sarcoidosis | ||

| Ramsey-Hunt syndrome | Middle ear surgery | ||

| Mastoiditis | Facial trauma | ||

| Ischemic syphilis | |||

| Otitis media | |||

| Osteomyelitis of the skull base | |||

| Sinusitis |

After comprehensive evaluation, we believed this patient had a resolving aseptic (viral) meningitis and his symptoms were not attributable to a neuroma, as originally thought. A repeat MRI at 3 months demonstrated complete resolution of the previous enhancing areas and the growth that originally showed as a soft tissue mass.

This interesting clinical presentation highlights the critical need by oncologists to fully consider other disease entities when evaluating these referred patients. For many patients with a presumed acoustic neuroma, biopsy is typically not done, and the patient is empirically treated with stereotactic radiation therapy based on clinical presentation and radiographic appearance. Oncologists should remember that “Therefore, go not to immediately irradiate, when the Bell’s Palsy tolls, but think carefully before treating when it does …”

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The authors thank Norman Coleman, MD, Padmini Kaushal, MD, Mary Frances McAleer, MD, PhD, Anupam Goel, MD, and Denise Roach for assistance.

REFERENCES

- 1.Gilden DH. Bell’s Palsy. New Engl J Med. 2004;351:1323–1331. doi: 10.1056/NEJMcp041120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Holland JN, Weiner GM. Recent developments in Bell’s Palsy. Br Med J. 2004;329:553–557. doi: 10.1136/bmj.329.7465.553. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Adams RD, Victor M. Diseases of the spinal cord, peripheral nerve, and muscle. In: Adams RD, Victor M, editors. Principles of Neurology. 7th ed McGraw Hill; New York: 1993. pp. 709–712.pp. 786–790. [Google Scholar]