Abstract

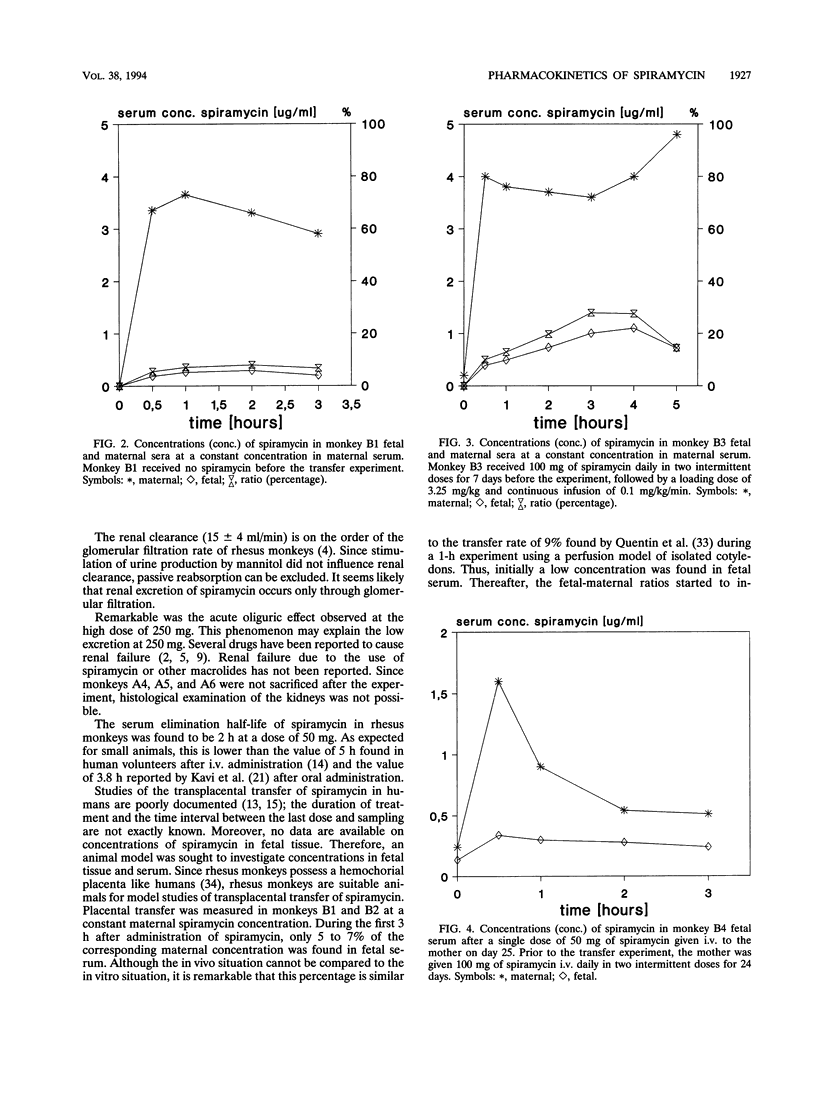

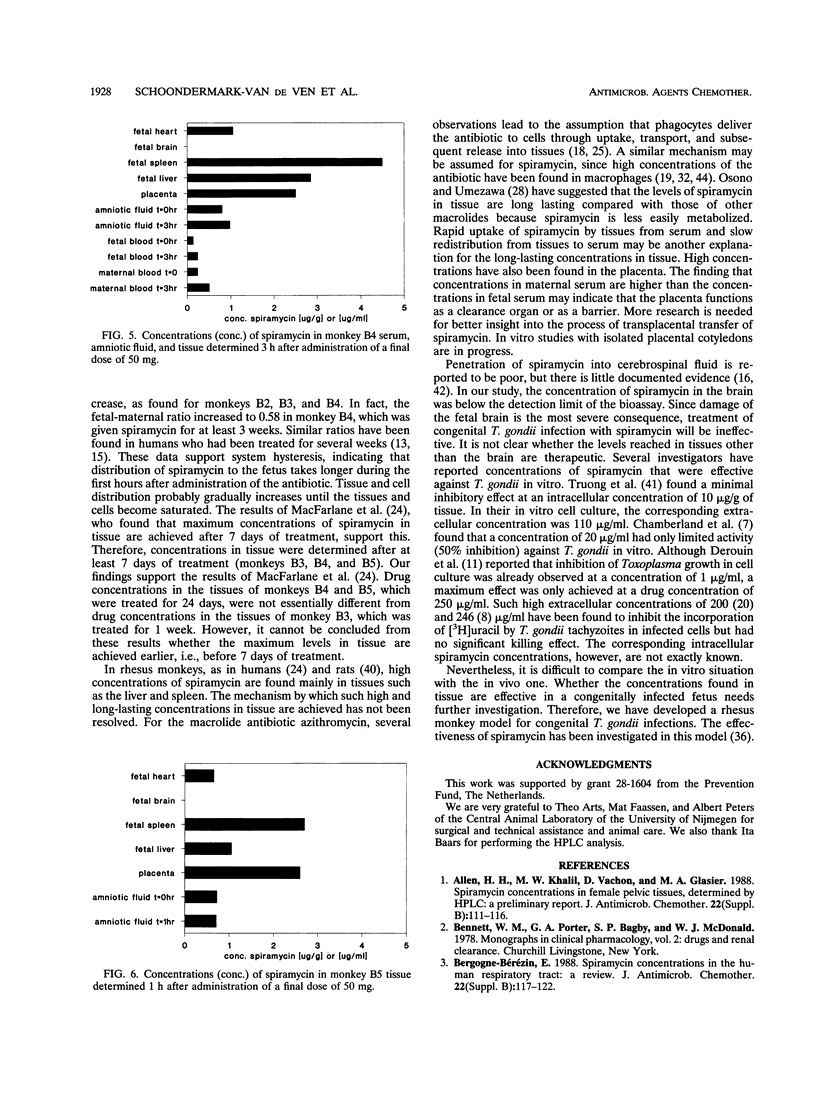

Transplacental transfer of spiramycin was investigated in a rhesus monkey model to study whether the antibiotic reaches therapeutic levels in the fetus. Spiramycin concentrations were measured by bioassay and high-performance liquid chromatography. Pharmacokinetic parameters were determined for bioactive spiramycin as measured by the bioassay. Pharmacokinetic pilot studies showed that spiramycin distribution follows a two-compartment model in rhesus monkeys. Following a single intravenous dose of 50 or 250 mg, dose-dependent kinetics were observed. At a dose of 50 mg, 10% of the dose was excreted unchanged in the urine. At the higher dose of 250 mg, an oliguric effect was observed. Spiramycin concentrations in fetal serum were measured over time while the maternal concentration was maintained at a constant level. During a 5-h experiment, a maximum fetal-maternal serum ratio of 0.27 was found. In three fetuses, concentrations in serum and tissue were measured following intravenous administration of 50 mg of spiramycin twice daily to the mother for at least 7 days. The fetal-maternal serum ratios were found to be 0.4 to 0.58 after intravenous administration of the final dose of 50 mg to the mother. It appeared that spiramycin accumulated in the soft tissues, especially in the liver and spleen, of both the mother and the fetus. The concentration in placental tissue appeared to be 10 to 20 times that of the concentration in fetal serum. The concentration of spiramycin in amniotic fluid was about five times higher than the concentration in fetal serum. Another important observation was that absolutely no spiramycin was found in the brain.

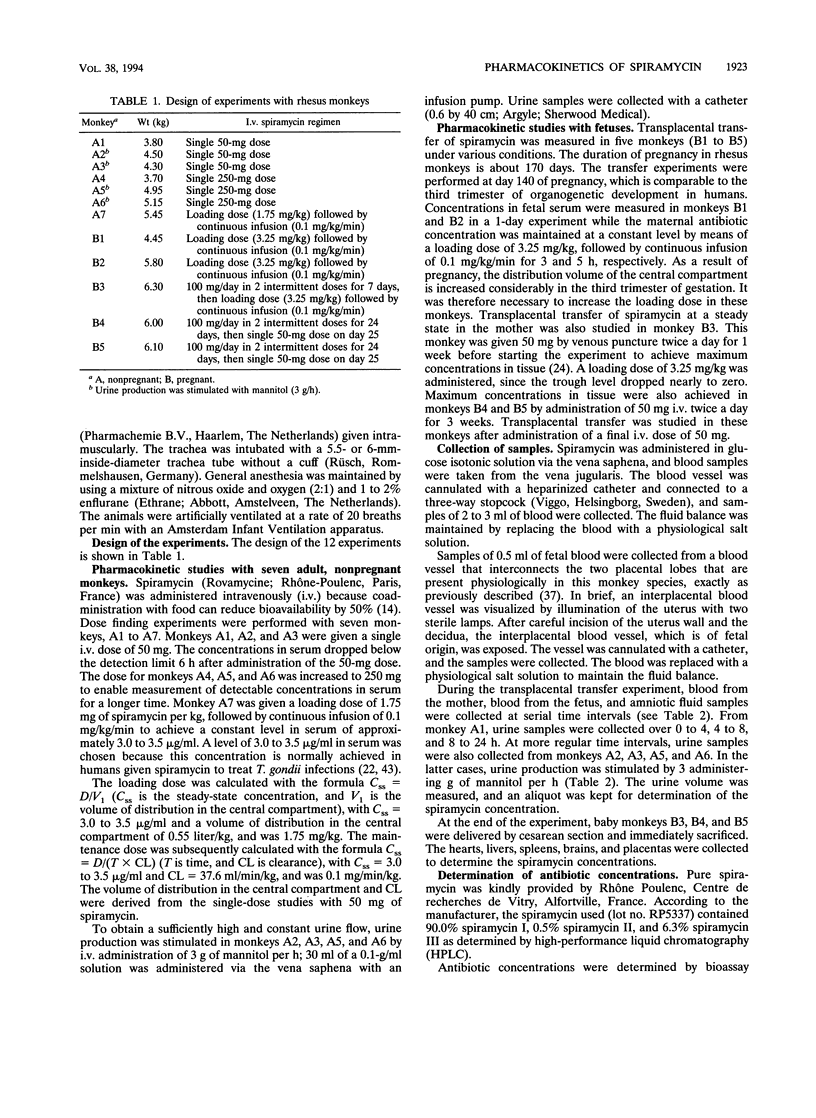

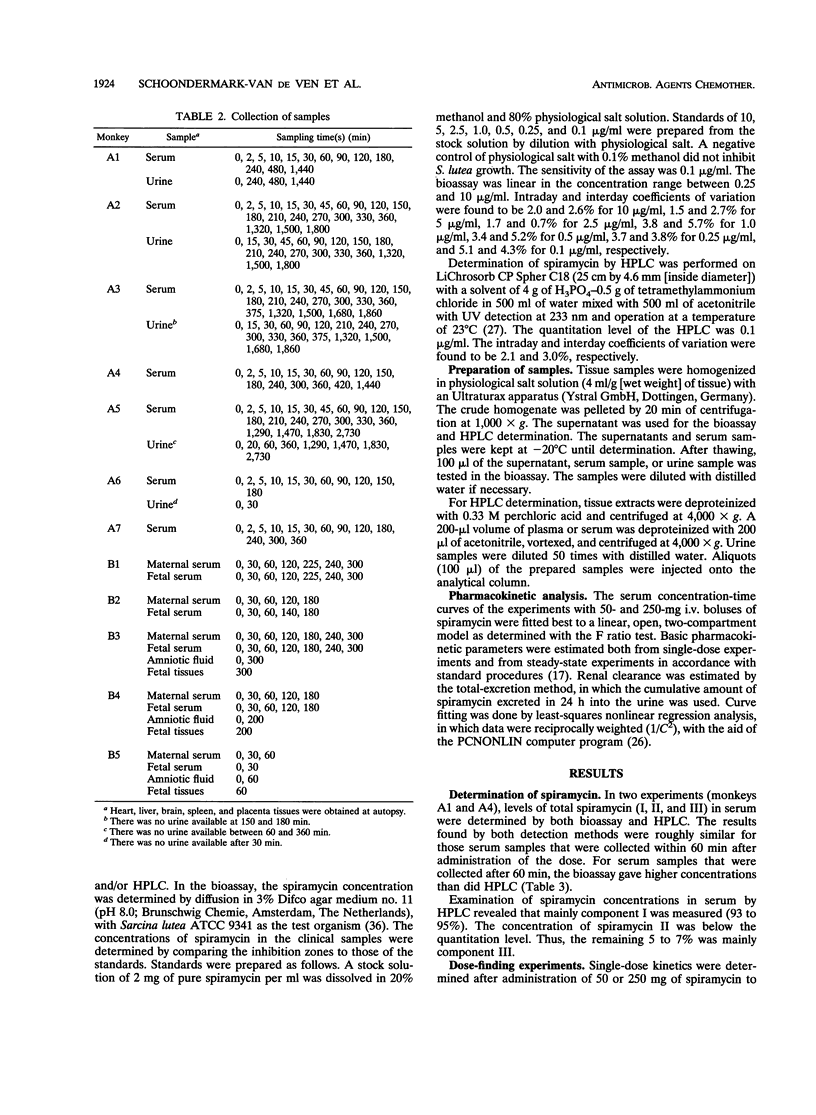

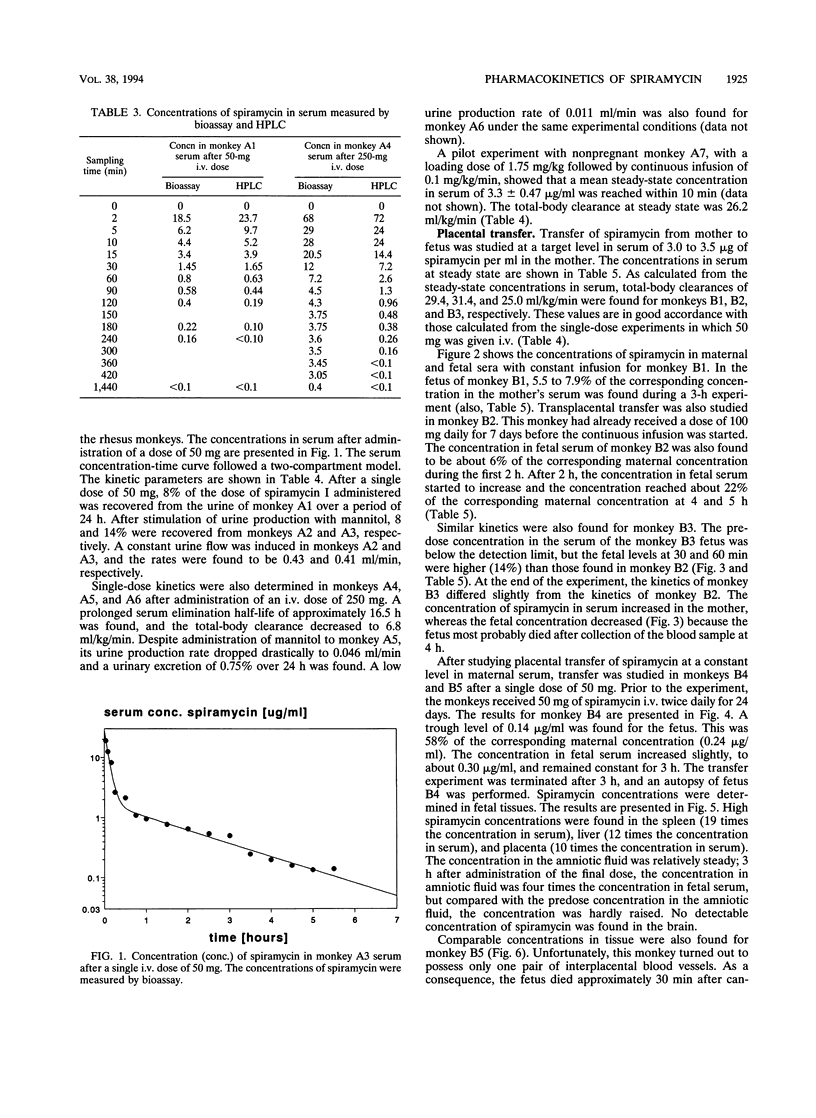

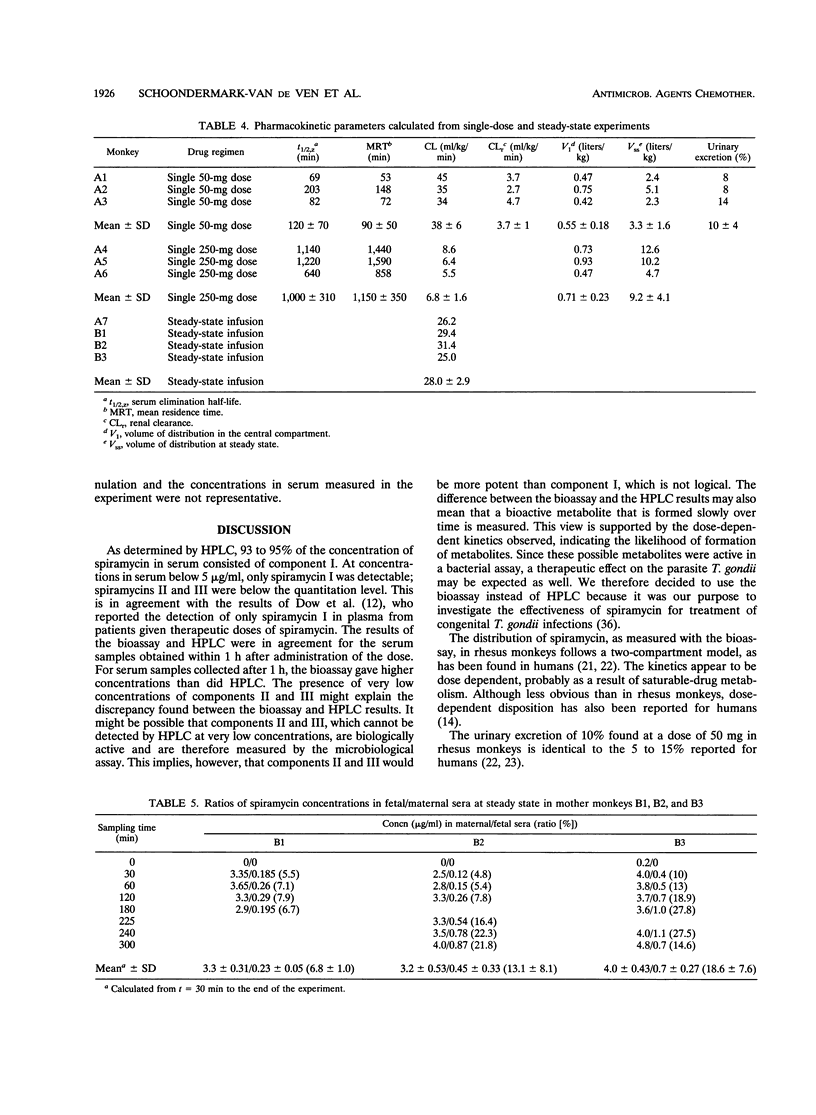

Full text

PDF

Selected References

These references are in PubMed. This may not be the complete list of references from this article.

- Allen H. H., Khalil M. W., Vachon D., Glasier M. A. Spiramycin concentrations in female pelvic tissues, determined by HPLC: a preliminary report. J Antimicrob Chemother. 1988 Jul;22 (Suppl B):111–116. doi: 10.1093/jac/22.supplement_b.111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bergogne-Bérézin E. Spiramycin concentrations in the human respiratory tract: a review. J Antimicrob Chemother. 1988 Jul;22 (Suppl B):117–122. doi: 10.1093/jac/22.supplement_b.117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brisson-Noël A., Trieu-Cuot P., Courvalin P. Mechanism of action of spiramycin and other macrolides. J Antimicrob Chemother. 1988 Jul;22 (Suppl B):13–23. doi: 10.1093/jac/22.supplement_b.13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chamberland S., Kirst H. A., Current W. L. Comparative activity of macrolides against Toxoplasma gondii demonstrating utility of an in vitro microassay. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1991 May;35(5):903–909. doi: 10.1128/aac.35.5.903. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chang H. R., Pechère J. C. In vitro effects of four macrolides (roxithromycin, spiramycin, azithromycin [CP-62,993], and A-56268) on Toxoplasma gondii. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1988 Apr;32(4):524–529. doi: 10.1128/aac.32.4.524. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davila D., Kolacny-Babić L., Plavsić F. Pharmacokinetics of azithromycin after single oral dosing of experimental animals. Biopharm Drug Dispos. 1991 Oct;12(7):505–514. doi: 10.1002/bdd.2510120704. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Derouin F., Nalpas J., Chastang C. Mesure in vitro de l'effet inhibiteur de macrolides, lincosamides et synergestines sur la croissance de Toxoplasma gondii. Pathol Biol (Paris) 1988 Dec;36(10):1204–1210. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dow J., Lemar M., Frydman A., Gaillot J. Automated high-performance liquid chromatographic determination of spiramycin by direct injection of plasma, using column-switching for sample clean-up. J Chromatogr. 1985 Nov 8;344:275–283. doi: 10.1016/s0378-4347(00)82028-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Forestier F., Daffos F., Rainaut M., Desnottes J. F., Gaschard J. C. Suivi thérapeutique foetomaternel de la spiramycine en cours de grossesse. Arch Fr Pediatr. 1987 Aug-Sep;44(7):539–544. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frydman A. M., Le Roux Y., Desnottes J. F., Kaplan P., Djebbar F., Cournot A., Duchier J., Gaillot J. Pharmacokinetics of spiramycin in man. J Antimicrob Chemother. 1988 Jul;22 (Suppl B):93–103. doi: 10.1093/jac/22.supplement_b.93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- GARTNER H. Recherches sur l'action de la spiramycine in vitro comparée à celle d'autres antibiotiques. Ann Inst Pasteur (Paris) 1956 Sep;91(3):312–322. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garin J. P., Pellerat J., Maillard, Woehrle R., Hezez Bases théoriques de la prévention par la spiramycine de la toxoplasmose congénitale chez la femme enceinte. Presse Med. 1968 Dec 7;76(48):2266–2266. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gladue R. P., Bright G. M., Isaacson R. E., Newborg M. F. In vitro and in vivo uptake of azithromycin (CP-62,993) by phagocytic cells: possible mechanism of delivery and release at sites of infection. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1989 Mar;33(3):277–282. doi: 10.1128/aac.33.3.277. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harf R., Panteix G., Desnottes J. F., Diallo N., Leclercq M. Spiramycin uptake by alveolar macrophages. J Antimicrob Chemother. 1988 Jul;22 (Suppl B):135–140. doi: 10.1093/jac/22.supplement_b.135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harris C., Salgo M. P., Tanowitz H. B., Wittner M. In vitro assessment of antimicrobial agents against Toxoplasma gondii. J Infect Dis. 1988 Jan;157(1):14–22. doi: 10.1093/infdis/157.1.14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kavi J., Webberley J. M., Andrews J. M., Wise R. A comparison of the pharmacokinetics and tissue penetration of spiramycin and erythromycin. J Antimicrob Chemother. 1988 Jul;22 (Suppl B):105–110. doi: 10.1093/jac/22.supplement_b.105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kernbaum S. La spiramycine. Utilisation en thérapeutique humaine. Sem Hop. 1982 Feb 4;58(5):289–297. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Macfarlane J. A., Mitchell A. A., Walsh J. M., Robertson J. J. Spiramycin the the prevention of postoperative staphylococcal infection. Lancet. 1968 Jan 6;1(7532):1–4. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(68)90001-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McDonald P. J., Pruul H. Phagocyte uptake and transport of azithromycin. Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis. 1991 Oct;10(10):828–833. doi: 10.1007/BF01975835. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Osono T., Umezawa H. Pharmacokinetics of macrolides, lincosamides and streptogramins. J Antimicrob Chemother. 1985 Jul;16 (Suppl A):151–166. doi: 10.1093/jac/16.suppl_a.151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- PELLERAT J., MAILLARD M. A. Fixation tissulaire de la spiramycine chez le cobaye; comparaison avec d'autres antibiotiques. C R Hebd Seances Acad Sci. 1958 Sep 22;247(12):894–896. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pechère J. C. The activity of azithromycin in animal models of infection. Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis. 1991 Oct;10(10):821–827. doi: 10.1007/BF01975834. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pocidalo J. J., Albert F., Desnottes J. F., Kernbaum S. Intraphagocytic penetration of macrolides: in-vivo comparison of erythromycin and spiramycin. J Antimicrob Chemother. 1985 Jul;16 (Suppl A):167–173. doi: 10.1093/jac/16.suppl_a.167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Quentin C. F., Besnard R. M., Bonnard O., Akbaraly R., Brachet-Liermain A., Leng J. J., Bebear C. Etude préliminaire in vitro du passage transplacentaire de la spiramycine. Pathol Biol (Paris) 1983 May;31(5):425–428. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schentag J. J., Ballow C. H. Tissue-directed pharmacokinetics. Am J Med. 1991 Sep 12;91(3A):5S–11S. doi: 10.1016/0002-9343(91)90394-d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schoondermark-Van de Ven E., Melchers W., Camps W., Eskes T., Meuwissen J., Galama J. Effectiveness of spiramycin for treatment of congenital Toxoplasma gondii infection in rhesus monkeys. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1994 Sep;38(9):1930–1936. doi: 10.1128/aac.38.9.1930. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schoondermark-Van de Ven E., Melchers W., Galama J., Camps W., Eskes T., Meuwissen J. Congenital toxoplasmosis: an experimental study in rhesus monkeys for transmission and prenatal diagnosis. Exp Parasitol. 1993 Sep;77(2):200–211. doi: 10.1006/expr.1993.1077. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith C. R. The spiramycin paradox. J Antimicrob Chemother. 1988 Jul;22 (Suppl B):141–144. doi: 10.1093/jac/22.supplement_b.141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- WALTER A. M. Neue Antibiotika. Dtsch Med Wochenschr. 1956 Dec 14;81(50):1992–1997. doi: 10.1055/s-0028-1115276. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zenebergh A., Trouet A. Cellular pharmacokinetics of spiramycin in cultured macrophages. Ann Immunol (Paris) 1982 Nov-Dec;133D(3):235–244. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]