Abstract

A qualitative exploratory study investigated the experiences and needs of family carers of persons with enduring mental illness in Ireland. The current mixed-methods secondary study used content analysis and statistical procedures in order to identify and explore the coping strategies emerging from the original interviews. The majority of family carers reported use of active behavioural coping strategies, sometimes combined with active cognitive or avoidance strategies. The percentage of cares reporting use of active cognitive strategies was the lowest among those whose ill relative lived in their home, and the highest among those whose relative lived independently. Participants with identified active cognitive strategies often reported that their relative was employed or in training. Participants who reported use of avoidance strategies were significantly younger than participants who did not report use of such strategies. The lowest percentage of avoidance strategies was among participants whose ill relative lived independently, whereas the highest was among carers whose relative lived in their home. The findings of this study highlight the importance of a contextual approach to studying coping styles and processes. Further research questions and methodological implications are discussed.

Introduction

Studies show that family carers play an important role in treatment and rehabilitation of persons with mental illness (1); (2). The participation of carers and families in coping skills and problem-solving trainings can reduce patients' hospitalization rates (3). Carers and relatives of persons with mental illness are at greater risk of psychiatric morbidity and stress-related illness than the general population (4); (5).

Research shows that the support of a family member by mental health services often helped the whole family to cope with the stresses of mental illness (6). In order to inform the design and maintenance of effective family support resources, it is helpful to study the constructive adaptation of family members to enduring illness of a relative (7).

The original study: experiences and needs of carers

An exploratory Family Support Study (8) collected qualitative data on the experiences and needs of family carers of persons with enduring mental illness of two or more years' duration. The study adopted a broad definition of a family, often used in clinical psychology and counselling (9). This definition includes one's family of origin (parents and siblings) and spouses and children, including step- and foster- parents and children (10). The main purpose of this family-related research (11) was to explore the experiences and needs of individual family members in order to inform recommendations for various stakeholders in the mental health area.

The term carers selected for the study referred to the participants who were closely related to persons with enduring mental illness. Lefley (12) argues that the terms care-givers and care-takers are mostly associated with functional aspects of caring tasks and responsibilities, and do not encompass the whole spectrum of emotional and social investments of family caring. Lefley (12) defines carers as “individuals whose own happiness is entwined with the well-being of people who are dear to them” (p. 141). The terms carers and participants are used interchangeably in this article and refer to parents, step-parents, spouses and siblings of persons with enduring mental illness. The term persons with mental illness refers to the ill relatives of the participants of the study. In this article, the terms persons with enduring mental illness and ill relatives are used interchangeably as appropriate.

In the course of the interviews participants were asked whether they considered themselves to be the main (responsible) carers, or secondary carers. This question was designed as an additional tool for the exploration of the individual needs and adaptation to mental illness of various family members.

The term enduring rather than chronic mental illness was used in the study due to the challenges of the chronicity paradigm evolving from research on rehabilitation and recovery of persons diagnosed with severe mental illness (13), (14). In this study, enduring mental illness was defined as being of two or more years' duration and requiring contacts with mental health services or professionals at least twice within one year.

The original study proposal and the final report had undergone peer reviews. The study received the ethical approval from the Research Ethics Committee of the Health Research Board (HRB) on 8 July 2005, and the ethics committee of the participating mental health services on 15 July 2005.

The majority of participants (n=26/38, 68.4%) were recruited via Schizophrenia Ireland (SI), a voluntary Irish organisation supporting persons with mental illness and their families. Nearly one-third of participants (n=12, 31.6%) were recruited via public mental health services (MHS) of an area of county Dublin, whereby the services contacted the next-of-kin of persons using their services where appropriate. Representatives of SI and MHS disseminated the HRB information letters about the study among potential participants. Volunteers contacted the researchers directly to agree on the interview date and location. Most of the interviews were carried out in the HRB office in Dublin City.

Prior to the interviews, participants were asked to sign a consent form and to fill out two socio-demographic questionnaires pertaining to them and their ill relatives. Persons with mental illness did not participate in this study; information related to the diagnosis and the use of mental health services was collected from their carers.

The participants were asked open-ended questions about their experiences of the illness in the family, encounters with mental health services, and available and needed family support resources. Interviews lasted between 45 minutes and two hours. All interviews were audio-taped and transcribed verbatim. In total, 38 carers were interviewed for the study.

During the interviews participants were asked what helped them to cope during their most difficult periods of experience. Data on the specific coping mechanisms of individual family members was used for the purposes of analysing carers' needs. Detailed analysis of self-reported coping mechanisms was not performed for the original exploratory study.

The secondary analysis: coping of carers

Many researchers (15) have emphasised coping as a key concept for the study of adaptation and health. Coping can be defined as a cognitive, affective or behavioural effort made by the individual to offset the impact of harm, threat or stress when an automatic response is not readily available (16). There are two distinct theoretical approaches to studying coping: as a relatively stable personality characteristic, and as a changing process shaped by its adaptational context (17).

Some descriptions of coping style as a personality characteristic pertain to how a person approaches a problem, i.e. making an active effort to solve it or trying to avoid it (18). Coping strategies were further categorised by response to a stressor, such as cognitive (internal) or behavioural (external) (19). The current study adapted the classification of coping often used in health research, which involves a combination of avoidance, active behavioural and active cognitive coping styles (20). Active behavioural coping style pertains to such external behaviours as problem-solving, talking or seeking professional help. Active cognitive style involves such internal processes as acceptance, positive reassessment, or finding inner strength in religious beliefs. Avoidance style includes such strategies as trying to ignore the problem, resorting to legal or illegal drugs, and keeping fears or worries to oneself without discussing them with others (21).

Several studies show that active behavioural and active cognitive strategies may be more effective for alleviating distress than passive strategies, such as avoidance. For example, a study of young adolescents coping with divorce in the family (22) showed that girls, who reported use of avoidance coping, demonstrated more psychological and physical problems than boys or girls who did not report use of such strategies.

Whereas individual coping styles can be shaped by some personal or socio-demographic factors and may remain relatively stable across the life span, the range and number of specific coping strategies can be constantly changing over the life time of individuals (15). A broader range of coping strategies may be acquired with age (23), (24); and a higher number and range of coping mechanisms may be used in response to higher levels of perceived stress or complexity of mental health problems (21), (20).

Some studies explored the process of family adaptation to mental illness holistically and identified various stages from the onset of illness to recovery (25), (26), (27), (6). Some coping mechanisms used by various kinship groups at different stages of experience were described in the original study. However, the interaction of the coping styles of carers with some contextual factors required further investigation.

In this article the term coping strategy is used to describe a specific coping behaviour or technique employed by an individual in a stressful situation, e.g. doing household chores or exercising. The term coping style refers to a broader classification of specific coping strategies into active behavioural, active cognitive or avoidance styles, as suggested by Holahan and Moos (28). For example, such strategies as exercising would fall under the definition of active behavioural coping style, trying to look at the positive side of things would be classified as active cognitive coping, whereas avoiding contact with the ill relative would fall into avoidance style.

Aims and objectives

The current research will use qualitative data collected by the previous exploratory study in order to investigate the coping strategies and styles used by the carers of persons with enduring mental illness, and the interaction of their coping strategies and styles with some personal and contextual factors.

The specific objectives of this study are to:

identify and describe the coping strategies and styles of participants as emerging from their narratives;

investigate the interaction of identified coping strategies and styles with the socio-demographic characteristics of participants;

explore the interaction of the identified coping styles with contextual factors, including duration of illness, living arrangements and occupational status of the ill relative.

Method

Design

Content analysis (29) was used in order to explore and classify the self-reported coping strategies and styles of participants as emerging from the original interviews. Statistical procedures were employed to further explore the interaction of coping styles with contextual factors. The authors were driven by pragmatism rather than an epistemological principle (30). The main reason for selecting the mixed-methods approach was the nature of the research question (31).

Combining qualitative and quantitative methods has proven to be beneficial in such multidisciplinary research areas as public health, nursing or health education (32). Mixed-methods research in such areas allows researchers to study complex phenomena which may not be fully captured by other research methods (33).

Whereas a lot of quantitative research on coping has been carried out, the relationship between its personal and contextual aspects is still not clear and warrants further research (17). The mixed-methods analysis allowed the researchers to explore the qualitative data from the perspective of well-established quantitative findings in the area of stress and coping, and to further interpret the emergent findings using qualitative data.

Data collection and participants

The secondary analysis was performed on the original narratives of 31 of the 38 participants who responded to the question: “So what helped you to cope during your most difficult periods of experience?” The rest of the participants (n=7/38) commented that they were not sure how they coped during their most difficult times.

Most of the 31 participants who provided data on how they coped were female (n=22, 71%), and nine (29%) were male. There were 18 mothers (58.1%), eight fathers (25.8%), three sisters (9.7%), one wife (3.2%) and one brother (3.2%). The majority of both female (n=20/25, 80%) and male (n=5/6, 83.3%) participants considered themselves to be main carers, and less than one-quarter of the participants (n=6/31, 19.4%) considered themselves to be secondary carers.

The age of the 31 participants ranged from 20 to 81 years old (M=61.6, SD=14.4) and was re-coded into four broad age groups: 20–54 years (n=4, 12.9%), 55–64 years (n=12, 38.7%), 65–74 years (n=10, 32.3%), and 75 years or over (n=5, 16.1%). The majority were recruited via SI (n=20/31, 64.5%) whereas over one third were recruited via MHS (n=11/31, 35.5%). Most of the participants (n=20/31, 64.5%) attended some family support groups at the time of the study.

As reported by the participants, the majority of their 31 ill relatives were male (n=24, 77.4%), and seven (22.6%) were female. Most (n=26, 83.9%) had been diagnosed with schizophrenia. The approximate duration of illness ranged from two to 49 years (M=16.7, SD=11.4). The Psychosocial Resistance to Activities of Daily Living Inventory (PRADLI) (34) scores of the independent functioning of ill relatives in the last 30 days, reported by 29 participants, ranged from 42 to 56 on a scale from seven to 56, (M=50.4, SD=11.4). These scores indicated a relatively independent level of functioning (34). Two participants were not sure about the current level of independent functioning of their relative.

The majority of participants (n=19/31, 61.3%) commented that their relative was residing outside their family home, namely in community residences (n=7/31, 22.6%), in in-patient units (n=6/31, 19.4%) or in independent accommodation (n=6/31, 19.4%). The employment status of 30 relatives (excluding one retired) was re-coded into two broad categories of occupied (n=14/30, 46.7%), including those in full-time, part-time, or sheltered employment or in training, and unoccupied, including those not in any kind of employment or training at the time of the study (n=16/30, 53.3%).

Data analysis

The current study used a combination of content analysis (29) and statistical procedures for the analysis of qualitative data. Some researchers suggest using a bespoke criteria approach to evaluation of mixed-methods studies integrating qualitative and quantitative data (35). Such criteria are based on the commonalities between quantitative and qualitative criteria, and include truth value (internal validity in quantitative studies versus credibility in qualitative studies), applicability (external validity versus transferability), consistency (reliability versus dependability), and neutrality (objectivity versus confirmability).

The research objectives, analysis, coding and quality criteria were discussed in detail and agreed upon by the authors of the article. The secondary analysis was designed and drafted by the lead researcher of the original study. The first author had previously carried out qualitative and quantitative research projects in the areas of education, sociology, drug misuse and mental health. The second author had been involved in extensive quantitative research in cognitive psychology, addiction and mental health. It may be suggested that the authors' multidisciplinary research backgrounds contributed to the neutrality, consistency and applicability of analysis.

In order to reduce potential bias associated with the original data collection and analysis, the lead researcher re-read the original transcripts of the 31 participants who responded to the question about how they coped during their difficult times. Passages containing data on coping were extracted from the original transcripts and imported to an Excel spreadsheet, together with an interview number and their page numbers in the original transcript. The lead researcher highlighted and coded the self-reported coping strategies following the guidelines of Holahan and Moos (28).

To verify and finalise the coding, the Excel data was imported into SPSS Text Analysis for Windows 1.5 with the interview number. The categories of active behavioural, active cognitive and avoidance were added on SPSS Text Analysis and linked to the relevant narratives of each participant. During categorising, an additional active behavioural strategy was identified in the narrative of one participant. SPSS Text Analysis was used to count the frequencies of occurrences of specific coping strategies within each broader coping category, and to check the total number of strategies in the extracted data.

In order to address the consistency of the coding, the second author independently highlighted self-reported coping strategies in the printed out Excel spreadsheet, and re-coded them into strategies and styles following the guidelines of Holahan and Moos (28). The two Excel sheets with the outcomes of the coding and re-coding of the two authors were compared. The second author identified one more avoidance strategy self-reported by a participant. The interpretation of ‘going on automatic’ during relative relapses was discussed by the two authors. It was agreed upon as being an avoidance strategy, similar to ‘blocking it out’ or avoiding the problem, and was added to those previously coded.

The identified and coded coping strategies and styles were imported from SPSS Text Analysis 1.5 to SPSS 14.0 and merged with socio-demographic data. Multiple response tables were used for the exploration of participants' coping strategies and styles, and cross-tabulations were used for comparison of coping styles by gender and other nominal variables. Results of Pearson's Chi-square tests were reported only for cross tabulations in which no cells had an expected count of less than five. The Mann-Whitney non-parametric test was used to explore interaction of specific coping styles with continuous variables such as age.

After the analysis and write up, two other members of the mental health research team reviewed the article, and provided comments on the credibility of the coding and re-coding (31). One of the recommendations was to insert more quotes to the results section, illustrating the allocation of the self-reported coping strategies into coping styles. Several more quotes were added to the manuscript. Another recommendation was to re-check the full interview transcripts in order to ensure that the coding matched the broader context of the interviews, and that all self-reported coping strategies were captured. The authors re-read the original transcripts in order to ensure that the truth value of the narratives was not distorted by recoding. No discrepancies between the coding and the broader context of narratives were found; no additional self-reported strategies were identified from the rest of the transcripts.

Results

The coping strategies and styles of participants

On the basis of the qualitative data emerging from 31 participants, 19 main coping strategies were identified and coded. A range of one to six coping strategies emerged from each participant, which resulted in a total of 89 reported usages of these strategies. The average number of the identified strategies per each participant was 2.9 (SD=1.5).

Table 1 presents the main identified coping strategies, by number and percentages of participants self-reporting these strategies, and by their allocation in the three coping styles.

Table 1. Numbers and percentages of participants by coping styles and by frequency of reported strategies.

| Number | % | Frequency ranking |

|

|---|---|---|---|

| Active behavioural style strategies | |||

| Seeking support from others | 10 | 32.3 | 1 |

| Talking | 9 | 29.0 | 2 |

| Trying to be in control | 8 | 25.8 | 3 |

| Exercise and relaxation | 6 | 19.4 | 4 |

| Getting professional help | 6 | 19.4 | 5 |

| Getting information | 6 | 19.4 | 6 |

| Studying | 3 | 9.7 | 12 |

| Doing household chores | 3 | 9.7 | 13 |

| Working | 3 | 9.7 | 15 |

| Being open about the illness | 2 | 6.5 | 18 |

| Active cognitive style strategies | |||

| Accepting caring as a family duty | 5 | 16.1 | 9 |

| Trying to look at the positive side of things | 4 | 12.9 | 10 |

| Applying previous experience or knowledge | 3 | 9.7 | 11 |

| Taking one day at a time | 3 | 9.7 | 16 |

| Religion | 2 | 6.5 | 17 |

| Avoidance style strategies | |||

| Avoiding discussions about illness | 6 | 19.4 | 7 |

| Avoiding contact with relative | 5 | 16.1 | 8 |

| Blocking it out | 3 | 9.7 | 14 |

| Prescribed and non-prescribed medication | 2 | 6.5 | 19 |

The three most frequently reported coping strategies were seeking support from others (n=10, 32.3%), talking (n=9, 29%) and trying to be in control (n=8, 25.8%). These strategies fell into the active behavioural coping style (Table 1).

The majority of participants reported the use of coping strategies classified as active behavioural (n=30/31, 96.8%); 15 participants reported the use of active cognitive strategies (48.4%) and 13 participants reported the use of avoidance strategies (41.9%).

Out of 31 participants, five (16.1%) reported using coping strategies which fell into the three coping styles of active behavioural, active cognitive and avoidance:

It was a struggle to work, and yet I wanted to work [working: active behavioural], had to get away from thinking of the situation [blocking it out: avoidance]. We were very active at the time, even to this day we'd bring him with us and we'd walk for two or three hours [exercise: active behavioural], and he's our friend now as well as our son, you know [trying to look at the positive side of things: active cognitive].

The reported coping strategies of nine participants fell into two coping styles of active behavioural and active cognitive (29%):

Well my religion helps me an awful lot [religion: active cognitive], and the SI group, and my husband [seeking support from others: active behavioural]. I'd say it's a combination of them all really, they're all quite different.

Eight participants used a combination of active behavioural and avoidance coping (25.8%):

I'd start cleaning, or polishing, or doing the garden [doing household chores: active behavioural]. Take other things on board [blocking it out: avoidance], and then it'll even itself out, he's calmed down and I've calmed down.

No participants reported a combination of just avoidance and active cognitive coping.

The coping strategies and styles of participants by gender, attendance at family support groups and caring responsibility

The distribution of specific coping strategies reported by male and female participants was slightly different. A slightly higher percentage of male (n=2/9, 22.2%) than female (n=3/22, 13.6%) participants reported coping by exercise and relaxation, and trying to be in control of the situation (compare n=3/9, 33.3% of males with n=5/22, 22.7% of females). Only female participants reported use of such strategies as doing household chores (n=3/22, 13.6%), ‘blocking it out’ (n=3, 13.6%), and taking one day at a time (n=3, 13.6%).

There were slight differences in the specific coping strategies reported by attendees and non-attendees at family support groups. A higher percentage of participants not attending family support groups coped by considering caring as their family duty (n=4/11, 36.4%), than that of participants attending family support groups (n=1/20, 5%). Nearly one-third of those attending family support groups reported that they coped by exercise and relaxation (n=6/20, 30%), whereas carers not attending family support groups did not report such ways of coping.

No significant gender differences in the three major coping styles were observed. Both gender groups reported a higher use of active behavioural, than of avoidance and active cognitive strategies. No significant differences in coping styles were found between the main and secondary carers, between the two recruitment subgroups of the sample (SI and MHS), and between the attendees and non-attendees at family support groups.

The coping strategies and styles of participants by age

All participants of the ‘youngest’ group aged 20–54 years (n=4) reported use of active behavioural strategies, such as getting professional help, or trying to be in control. Such strategies were combined with avoidance ones (n=4, 100%), such as ‘blocking it out’, or avoiding discussions about mental illness.

Participants who reported the use of avoidance coping strategies (n=13) were significantly younger (M = 52.7, SD = 17.2) than those who did not report the use of such strategies (n=18, M = 68.1, SD =7.1): [U (18, 13) = 42.5, p = .002].

All participants aged 75 years or over reported the use of active behavioural strategies (n=5, 100%), such as seeking support from others, or doing household chores. Such strategies were often combined with active cognitive ones (n=3, 60%), such as taking one day at a time, or trying to look at the positive side of things.

Two participants aged between 55 and 64 commented that they had gradually ‘learned’ to use such skills as taking one day at a time, or accepting the family situation: “But then I suppose you learn to live with it, and take each day as it comes [taking one day at a time: active cognitive].”

The coping strategies and styles of participants by place of residence of their ill relative

Participants whose ill relative resided in their home reported use of 18 out of the total 19 strategies. One-third of such 12 participants reported that they coped by getting involved in physical activities and relaxation exercises (n=4, 33.3%), and by avoiding discussions about mental illness in the family (n=4, 33.3%).

Participants whose relatives were in in-patient units reported a total use of 14 coping strategies out of 19. Half of such participants (n=3/6, 50%) commented that they coped by seeking support from voluntary organisations, friends or relatives.

Participants whose relatives resided in community residences (n=7) reported the use of 12 coping strategies out of 19 at least once. Such participants reported variable strategies, including applying previous knowledge or avoiding contact with the relative.

Six participants whose relative resided in independent accommodation reported the use of 11 coping strategies. Half of such participants reported that they had been coping by talking (n=3/6, 50%).

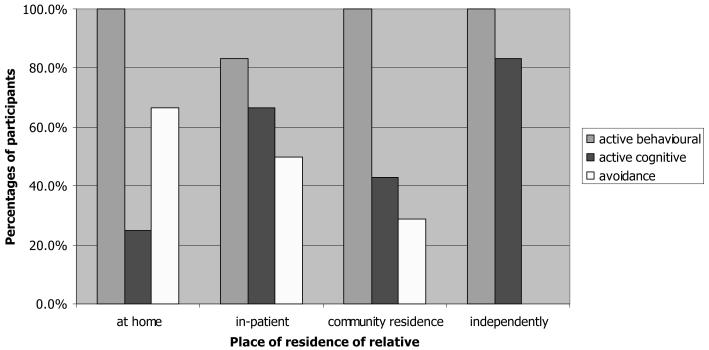

Figure 1 presents participants' coping styles by place of residence of the ill relative at the time of the study.

Figure 1. Percentages of participants by reported coping styles and by place of residence of ill relative.

As can be seen from Figure 1, all participants whose relative resided in their home (n=12, 100%), independently (n=6, 100%) or in a community residence (n=7, 100%) reported use of strategies falling into an active behavioural style. A slightly lower percentage of participants whose relative resided in an in-patient unit (n=5/6, 83.3%) reported use of active behavioural strategies, than the other residential groups.

The highest percentage of participants reporting use of active cognitive strategies was among those whose relative resided in independent accommodation (n=5/6, 83.3%) (Figure 1). The lowest percentage was among those whose relative resided in their homes (n=3/12, 25%). Differences in the identified strategies between 12 participants whose relative resided in their home and 19 of those whose relative resided elsewhere were statistically significant: [χ2 (1, N=31) = 4.3, p = .038].

One participant whose relative had recently moved to a community residence from an in-patient unit commented that though she was not fully satisfied with the quality of mental health services provided to her ill relative, it was time for her to accept the current situation:

And what could I do, up to this day, just trying, trying to help. Just that one person would listen to me and take him on one-to-one, even if it never did any good [trying to be in control: active behavioural]. In other words, I have given up on help, if you know what I am saying; I have given up looking for it. I just have to accept it, this is as good at the moment as it gets [trying to look at the positive side of things: active cognitive].

Percentages of participants reporting use of avoidance coping strategies decreased from the majority of those whose relatives resided in their household (n=8/12, 66.7%), to half of those whose relatives were in in-patient units (n=3/6, 50%), and finally, to less than one-third of those whose relatives were in community residential facilities (n=2/7, 28.6%) (Figure 1). No participants whose relative lived in independent accommodation reported use of avoidance strategies.

One participant reflected that since their relative moved to independent accommodation, he worried much less, as now he had an option of sending her back to her house, rather than confronting or avoiding her “difficult” behaviour:

Well I don't worry as much now, I know she has her own home and if she's in my house and if she's difficult I can say “Well go back to your own house now”, whereas if I said that in the past she'd say “I don't have one”. Now she has a lovely little house and that has been a tremendous help to all of us.

Differences in reporting avoidance coping between 12 participants whose relatives resided in their homes, and 19 of those whose relatives did not reside in their homes were statistically significant: [χ2 (1, N=31) = 4.92, p = .027].

The active cognitive coping of participants and the duration of illness of their relative

Participants who reported the use of active cognitive strategies (n=15) also reported a slightly longer average duration of illness of their relative (M=20.1, SD=11.7), than those who did not report use of such strategies (n =16, M =13.5, SD = 9.2): [U (16, 15) = -1.7, p = .096].

Participants whose relative resided in their homes (n=12) reported a significantly shorter duration of illness of their relative (M= 11.7, SD=7.9), than the 19 participants whose relatives resided elsewhere: [U (12, 19) = 63.0, p = .038].

The active cognitive coping of participants and the psychosocial functioning of their ill relative

Participants who used active cognitive coping strategies (n=14) reported a slightly higher average PRADLI score of psychosocial functioning of their relatives (M=52.0, SD=3.9), than participants (n=15) who did not use such strategies (M=48.9, SD=4.5): [U (15, 14) = 65.0, p = .075].

The majority of ill relatives of participants who mentioned use of active cognitive strategies (n=9/14, 64.3%) were reported to be occupied, being either in employment (n=6) or in training (n=3):

Well at the moment she is absolutely fantastic, she has a part-time job, and she's talking about getting married, but that's another day. After seven years of being in and out of hospital, it's just all about today, and that's how I cope, I just deal with today [taking one day at a time: active cognitive].

The majority of relatives of participants who did not report use of such strategies (n=16), were reported to be unoccupied, i.e. unemployed and not in training (n=11/16, 68.8%): [χ 2 (1, N = 30) = 3.3, p = .070]:

I felt family counselling was needed because I could see we were all being dragged down in the house with all that was going on [getting professional help: active behavioural]. And I mean she's not working, she's not contributing. And how long, I mean I can't see her being able to hold any job to be quite honest, certainly not at the moment.

Discussion

The finding that most of the participants of this study reported use of active behavioural coping strategies, such as seeking support from other people and talking, is not counter-intuitive and may partially explain why these carers volunteered to take part in the study interviews. However, only five participants reported a combined use of all three coping styles. Very few carers reported use of active cognitive strategies combined with avoidance. Are active cognitive and avoidance coping strategies somewhat mutually exclusive in the context of enduring mental illness? Further exploration of contextual interaction of different coping strategies among larger groups of participants is needed to answer this question.

Distributions of some specific coping strategies of male and female participants, and of attendees and non-attendees at family support groups were slightly different. However, no significant differences in the coping styles of male and female participants, main and secondary carers or attendees and non-attendees at family support groups were observed in this study. In order to make recommendations for the design of family-tailored support resources, there is a need for further exploration of specific coping strategies across gender and by attendance at various support groups or programmes.

The finding that a high proportion of older people reported use of active cognitive strategies is in line with previous research showing that acceptance of health problems may increase with age (24). The finding that a higher percentage of younger participants reported use of avoidance strategies than older participants is of some concern and warrants further research. As shown by some previous studies, avoidance coping may have a negative effect on the psychological well-being of individuals, especially females (22).

These findings pose further questions regarding the interplay of coping styles with personal and developmental factors. What roles do age and previous experience play in shaping coping styles? Comments of participants suggested that active cognitive coping developed with age and at later stages of illness in the family. Further questions are: exactly when and how does it develop, does avoidance coping decrease with age, and is it more common at the early stages of mental illness of a relative?

The finding that the highest percentage of participants reporting use of avoidance strategies was among those whose relative resided in their homes requires further investigation. The same applies to the finding that the highest percentage of participants reporting use of active cognitive strategies was among those whose relative lived independently.

There may be several interpretations of these findings. Participants whose relatives resided in their homes reported a significantly shorter duration of illness of their relatives. Such participants were at the initial stage of their encounter with enduring mental illness, were less aware on how to deal with stressful situations and thus tended to use avoidance strategies more often than other groups of participants. They had yet to develop skills in order to employ active cognitive strategies, such as reassessing or accepting the situation. Conversely, participants whose relatives moved out of their homes seemed to have had more time and experience to develop active cognitive strategies.

In addition, some family members were less worried about confronting ‘difficult’ behaviour of their relative once they had their own accommodation. With their ill relatives living independently, family carers may not need to resort to avoidance strategies as often as they do when their relatives live in their home.

On the other hand, ill relatives of the participants who were living in their homes could have had more severe symptoms of mental illness and have not progressed yet in their rehabilitation or recovery. Such participants had not yet seen any improvement in their relatives' psychosocial functioning, and could have been under more stress than participants whose relatives had improved and lived independently. In line with some previous findings (21), participants whose ill relatives lived in their homes used a higher number of coping strategies in general and of avoidance strategies in particular.

We can also hypothesise that the use of active cognitive strategies by carers may have helped their ill relatives to progress in their rehabilitation so that they could live independently and engage in meaningful occupation. More research on the interaction of the degree of symptoms, accommodation of persons with mental illness, and the coping strategies of their carers is needed in order to test this hypothesis.

These findings raise further research questions. In what ways and to what extent do contextual factors shape personal coping strategies? Are contextual factors more powerful predictors of coping styles than personal or developmental ones? To what extent and in what way are personal, developmental, and contextual factors related to individual coping?

More research involving exploration of specific coping strategies across higher numbers of participants is needed to test the reliability and validity of these findings. Ideally such research should be of longitudinal design, aimed at the investigation of the use of specific coping strategies over time.

Additional qualitative data will help to explore and interpret contextual factors that may influence personal choice of coping strategies in specific situations. An interpretative qualitative approach to studying the impact of mental illness on family members or the family as a group may also help to answer some of the research questions raised by this study.

Limitations

Self-reported coping strategies were identified and manually re-coded into coping styles by the researchers. The subjectivity of the researchers' classification of the identified strategies into coping styles may have influenced the results. The use of the guidelines of Holahan and Moos (28), independent coding performed by the two authors, and suggestions of the internal reviewers may have helped to improve consistency of coding.

The sample of this study might have been more socially active than other carers due to the high proportion of participants attending at family support groups. The use of specific coping strategies by participants recruited via SI may have been enriched via communication with other families or through educational activities offered by SI.

The results of this secondary analysis need further validation and exploration via larger samples. Due to the small number of participants it was difficult to establish whether gender, the degree of caring responsibility or participation in family support groups played significant roles in the choice of individual coping strategies. Participation in cognitive behavioural therapy or family counselling may have also influenced the coping styles of carers and needs to be explored in this context. Information on the nature and degree of symptoms of persons with mental illness could have provided further insight into the choice and development of the coping strategies of their carers.

Conclusions and implications

The results of this study highlight the importance of a contextual approach to studying coping and caring. The effects of age, duration of illness, living arrangements and other contextual factors on the coping styles of carers, and on the recovery or rehabilitation of persons with mental illness require further investigation.

The findings suggest that longitudinal designs aimed at studying coping over time may be best suited to addressing the complexities in the areas of coping and caring. In addition, qualitative data can help to clarify and enrich quantitative findings, and to provide contextual understanding of how coping strategies used by carers may influence rehabilitation or recovery of persons with enduring mental illness.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank all the participants of the original study for sharing their unique experience with the researchers. The support and help provided by Schizophrenia Ireland and the mental health services of a Dublin area during the recruitment of study participants also deserve special recognition. Special thanks are due to Ms Rosalyn Moran, Dr Dermot Walsh and Ms Antoinette Daly for the insights and advice provided during their reviews of this secondary study.

References

- 1.Hanson JG, Rapp CA. Families' perceptions of community mental health programs for their relatives with a severe mental illness. Community Ment Health J. 1992;28(3):181–197. doi: 10.1007/BF00756816. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Dixon L, McFarlane WR, Lefley H, Lucksted A, Cohen M, Faloon I, Mueser K, Milkowitz D, Solomon P, Sondheimer D. Evidence-based practices for services to families of people with psychiatric disabilities. Psychiatr Serv. 2001;59:903–910. doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.52.7.903. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Cassidy E, Hill S, O'Callaghan E. Efficacy of psychoeducational intervention in improving relatives' knowledge about schizophrenia and reducing hospitalisation. Eur Psychiatry. 2001;16(8):446–450. doi: 10.1016/s0924-9338(01)00605-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Yee J, Schultz R. Gender differences in psychiatric morbidity among family caregivers: a review and analysis. Gerontologist. 2000;40(2):147–164. doi: 10.1093/geront/40.2.147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Stengard E, Honkonen T, Koivisto A, Salokangas RK. Satisfaction of caregivers of patients with schizophrenia in Finland. Psychiatr Serv. 2000;51:1034–1039. doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.51.8.1034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gavois H, Paulsson G, Fridlund B. Mental health professional support in families with a member suffering from severe mental illness: a grounded theory model. Scand J Caring Sci. 2006;20(1):102–109. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-6712.2006.00380.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Szmuckler GI, Burgess P, Herrman H, Benson A, Colusa S, Bloch S. Caring for relatives with serious mental illness: the development of the Experience of Caregiving Inventory. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol. 1996;31:137–148. doi: 10.1007/BF00785760. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kartalova-O'Doherty Y, Tedstone Doherty D, Walsh D. Family Support Study: A study of experiences, needs, and support requirements of families with enduring mental illness in Ireland. The Health Research Board; Dublin: 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Patterson J. Family research methods. In: Heflinger CA, Nixon CT, editors. Families and the mental health system for children and adolescents. Sage Publications; Thousand Oaks: 1996. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Rothausen T. ‘Family’ in organisational research: a review and comparison of definitions and measures. Journal of Organisational Behaviour. 1999;20:817–836. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Feetham S. Conceptual and Methodological Issues in Research of Families. In: Whall A, Fawcett J, editors. Family Theory Development in Nursing: State of the Science and Art. F.A. Davis Company; Philadelphia: 1991. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lefley HP. The impact of mental disorders on families and carers. In: Thornicroft G, Szmuckler G, editors. Textbook of Community Psychiatry. University Press; Oxford: 2001. pp. 141–154. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Harding C, Zahniser JH. Empirical correction of seven myths about schizophrenia with implications for treatment. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 1994;90(384):140–146. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0447.1994.tb05903.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kelly M, Gamble C. Exploring the concept of recovery in schizophrenia. J Psychiatr Ment Health Nurs. 2005;12:245–251. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2850.2005.00828.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lazarus RS, Folkman S. Stress, appraisal, and coping. Springer; New York: 1984. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Zeidner M, Endler NS, editors. Handbook of coping: Theory, research, applications. John Wiley & Sons; Canada: 1996. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lazarus RS. Coping Theory and Research: Past, Present, and Future. Psychosom Med. 1993;55:234–247. doi: 10.1097/00006842-199305000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Folkman S. Personal control and stress and coping processes: A theoretical analysis. J Pers Soc Psychol. 1984;46:839–852. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.46.4.839. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Moos RHS JA. Coping resources and processes: Current concepts and measures. In: L. Goldberg SB, editor. Handbook of stress: Theoretical and clinical aspects. 2 ed. Free Press; New York: 1993. pp. 24–45. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Holahan CJ, Moos RH, Schaefer JA. Coping, stress, resistance, and growth: Conceptualising adaptive functioning. In: Zeidner M, Endler NS, editors. Handbook of Coping: Theory, research, applications. John Wiley & Sons; Canada: 1996. pp. 24–43. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Boschi S, Adams RE, Bromet EJ, Lavelle JE, Everett E, Galambos N. Coping with Psychotic Symptoms in the Early Phases of Schizophrenia. Am J Orthopsychiatry. 2000;70(2):242–252. doi: 10.1037/h0087710. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Armisted L, McCombs A, Forehand R, Wierson M, Long N, Fauber R. Coping With Divorce: A Study of Young Adolescents. J Clin Child Psychol. 1990;19(1):79–84. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Williams K, De Lisi-McGillicuddy A. Coping strategies in adolescents. J Appl Dev Psychol. 2000;20(4):537–549. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Martin P, Rott C, Poon LW, Courtenay B, Lehr U. A Molecular View of Coping Behaviour in Older Adults. J Aging Health. 2001;13(1):72–91. doi: 10.1177/089826430101300104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Spaniol L, Zipple A. Coping strategies for families of people who have a mental illness. In: Lefley H, Wasow M, editors. Helping Families Cope With Mental Illness. Harwood Academic; New York: 1994. pp. 131–146. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Karp DA, Tanarugsachock V. Dealing with a family member who has a mental illness was a long term, frustrating, and confusing process before acceptance occurred. Qual Health Res. 2000;10(January):6–25. doi: 10.1177/104973200129118219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Marsh DT. A family-focussed approach to servious mental illness: empirically supported interventions. Professional Resource Press; Sarasota: 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Holahan CJ, Moos RH. Personal and contextual determinants of coping strategies. J Pers Soc Psychol. 1987;52:946–954. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.52.5.946. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hansen E. Successful Qualitative Health Research: A practical introduction. Open University Press; New York: 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 30.O'Cathain A, Murphy E, Nicoll J. Why, and how, mixed methods research is undertaken in health services research in England: a mixed methods study. BMC Health Services Research [serial on the Internet] 2007. [cited 24.07.07];7:[about 85 p.]. Available from: http://www.biomedcentral.com/1472-6963/7/85. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 31.Bryman A. Paradigm Peace and the Implications for Quality. Int J Social Research Methodology. 2006;9(2):111–126. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Baum F. Researching public health: Behind the qualitative-quantitative methodological debate. Soc Sci Med. 1995;40:459–68. doi: 10.1016/0277-9536(94)e0103-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Teddlie CT A. Major issues and controversies in the use of mixed methods in the social and behavioural sciences. In: Tashakkori A, Teddlie C, editors. Handbook of mixed methods in social and behavioural research. Sage Publications; Thousand Oaks: 2003. pp. 541–556. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Clifford PA, Cipher DJ, Roper KD. Assessing resistance to activities of daily living in long-term care. J Am Med Dir Assoc. 2003;(November/December):313–319. doi: 10.1097/01.JAM.0000094180.01678.45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Sale J, Brazil K. A strategy to identify critical appraisal criteria for primary mixed-methods studies. Quality and Quantity. 2004;38:351–365. doi: 10.1023/b:ququ.0000043126.25329.85. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]