Abstract

Objective: To describe factors related to underdiagnosis of asthma in adolescence.

Design: Subgroup analysis in a population based cohort study.

Setting: Odense municipality, Denmark.

Subjects: 495 schoolchildren aged 12 to 15 years were selected from a cohort of 1369 children investigated 3 years earlier. Selection was done by randomisation (n=292) and by a history indicating allergy or asthma-like symptoms in subject or family (n=203).

Main outcome measures: Undiagnosed asthma defined as coexistence of asthma-like symptoms and one or more obstructive airway abnormalities (low ratio of forced expiratory volume in 1 second to forced vital capacity, hyperresponsiveness to methacholine or exercise, or peak flow hypervariability) in the absence of physician diagnosed asthma. Risk factors (odds ratios) for underdiagnosis.

Results: Undiagnosed asthma comprised about one third of all asthma identified. Underdiagnosis was independently associated with low physical activity, high body mass, serious family problems, passive smoking, and the absence of rhinitis. Girls were overrepresented among undiagnosed patients with asthma (69%) and underrepresented among diagnosed patients (33%). Among the risk factors identified, low physical activity and problems in the family were independently associated with female sex. The major symptom among those undiagnosed was cough (58%), whereas wheezing (35%) or breathing trouble (50%) was reported less frequently than among those diagnosed. Less than one third of those undiagnosed had reported their symptoms to a doctor.

Conclusions: Asthma, as defined by combined symptoms and test criteria, was seriously underdiagnosed among adolescents. Underdiagnosis was most prevalent among girls and was associated with a low tendency to report symptoms and with several independent risk factors that may help identification of previously undiagnosed asthmatic patients.

Key messages

One third of young people with asthma are not diagnosed; most are girls

Undiagnosed asthma is associated with low physical activity, high body mass index, serious family problems, passive smoking, and the absence of symptoms of rhinitis

Cough is the most common symptom among those with undiagnosed asthma

Two thirds of those with undiagnosed asthma do not report their symptoms to a doctor, suggesting a need for targeted asthma campaigns

Introduction

Epidemiological surveys have shown asthma-like symptoms to be far more prevalent than physician diagnosed asthma,1 and underdiagnosis of asthma has repeatedly been suspected during the past two decades, especially in children and young adults.2,3 Screening studies that used a combination of symptoms and objective indicators of asthma have confirmed this view.4–6 In the present cohort children who reported asthma-like symptoms but not asthma at age 10 had impaired lung function.7

Some risk factors for the underdiagnosis of asthma have recently been proposed, including female sex,6,8 low socioeconomic status,9 or belonging to an ethnic minority,10 whereas the diagnostic process seems to be facilitated if previous episodes of acute bronchitis or a family history of asthma are reported.6

This population based study examined a broad selection of potential risk factors for underdiagnosis of asthma among adolescents with coexisting asthma-like symptoms and obstructive airway abnormalities.

Subjects and methods

The Odense schoolchild study is a prospective multidisciplinary epidemiological study in a community based cohort of 1369 schoolchildren first investigated during their third school year in 1985-6.11 The present analysis is based on data from 495 children aged 12 to 15 years and of Danish origin recruited from the original cohort for an extensive asthma and allergy screening programme. Subjects were selected either at random (n=292) or on the basis of a history indicating asthma, allergy, or related symptoms or a family history of asthma or allergic rhinitis (n=203).12 Subjects completed a comprehensive questionnaire and monitored their peak expiratory flow twice daily for 2 weeks. Laboratory examinations included anthropometric measurements, puberty staging, spirometry, treadmill exercise testing, and provocation with inhaled methacholine. Subjects were asked to stop taking bronchodilators (but not inhaled steroids) before testing. Informed consent was obtained from all children and parents or guardians before participation. The study was approved by the local research ethics committee, the local school board, and the Danish Data Surveillance Authority.

For the present analysis, currently symptomatic subjects were grouped according to the presence or absence of physician diagnosed asthma and positive test results. The variables analysed are listed in the box. Current asthma-like symptoms (ongoing or within the previous year) were identified by questionnaire as previously reported.12 Symptoms accepted included non-infectious cough, wheezing, and trouble breathing. Physician diagnosed asthma was identified by an affirmative answer to the question, “Is it your doctor’s opinion, that you have asthma?” or the use of prescribed asthma medication, or both. Subjects with no previous diagnosis of asthma but asthma-like symptoms and at least one positive test result (hypervariability in peak expiratory flow, hyperresponsiveness to exercise or inhaled methacholine, or low ratio of forced expiratory volume in 1 second (FEV1) to forced vital capacity (FVC)) were labelled as having undiagnosed asthma.

Variables analysed

Anthropometric and related measurements

• Sex

• Puberty stage

• Standing height

• Sitting height/standing height

• Body mass index

• Diastolic blood pressure

• Systolic blood pressure

Questionnaire information at age 10

• Birth weight

• Dyspnoea (nights or mornings)

• Wheezing or cough on exertion

• Bronchitis (explained)

• Eczema at elbows or knees (explained)

Questionnaire information at age 13

• Family and home environment: Number of subjects sharing home Number of children <15 years Serious family problems Living with father/male guardian Passive smoking (hours/day) Active smoking Type of home (house or apartment) Size of home Age of building Pet in bedroom Carpets in bedroom Signs of high humidity in home

• School environment: Inner city school Distance to school Absence with illness (days) Happy with school Bad indoor environment

• Activities: Physical activity (hours per week) Sitting down more than half of spare time Given up job due to health problem Given up sport due to health problem Biking to school

• Allergy: history and test: Predisposition for asthma, hay fever, or eczema Colic in first year of life Frequent diarrhoea in first year of life Passive smoking in first year of life Pets at home in first year of life Breast feeding time (months) Eye itching Serial sneezing (⩾3) Watery nasal secretion Eczema ever (explained) Urticaria (explained) Diet restrictions (allergy/intolerance)

• Frequency of extrarespiratory symptoms: Headache General indisposition Unprovoked articular pain Stomach ache Diarrhoea

Details of test procedures have been reported previously.12 The body mass index (weight (kg)/(height (m)2)) was also calculated. Puberty staging was done according to Tanner and Whitehouse13 and corrected for age by sex. Forced expiratory volumes were measured according to European recommendations.14 For the 6 minute treadmill provocation test results were expressed as the lowest FEV1 obtained during the first 10 minutes after exercise in percentage of the best value before exercise. Bronchoprovocation with methacholine was performed according to Yan et al15 and expressed as the methacholine dose response slope.16 It was ensured that all subjects regained their baseline FEV1 (within 10%) either spontaneously or aided by inhaled terbutaline (Bricanyl Turbohaler). Peak expiratory flow was recorded twice daily for 14 consecutive days with a Mini-Wright adult type peak flow meter. Variability in peak expiratory flow was expressed as the average of the two lowest values as a percentage of the period mean, after the first three recording days were discarded (the two lowest % mean index).17 Test results were considered abnormal if they were beyond the value delimiting the 5% “most asthmatic” part of the test distribution in 150 asymptomatic, non-smoking, and non-asthmatic reference subjects from the randomly selected part of the present cohort. The association of a range of medical, environmental, social, school, and activity related factors (see box) with undiagnosed versus diagnosed asthma and with asthma versus asthma-like symptoms only was assessed by logistic regression with spss.18

Variables that seemed to be differently distributed (P<0.15) between the groups compared were included in the logistic regression analysis by using backward selection (final removal criterion P>0.05). Questionnaire information and test results directly related to grouping criteria were not included in the regression models but were analysed separately. The Medstat program (Astra Denmark, Copenhagen) was used to calculate 95% confidence intervals on proportions. Proportions were compared with χ2 statistics with Yates’s correction.

Results

Among 495 subjects investigated, 128 had current asthma-like symptoms. Of these, 15 (12%) were excluded from analysis because of missing data for group allocation. Forty five had physician diagnosed asthma, and 26 were considered as having undiagnosed asthma. The 42 remaining subjects had “symptoms only” (negative test results and not diagnosed with asthma). Despite the “normalising” effect of treatment with inhaled steroids on test results,12 the sensitivity of the test battery for symptomatic physician diagnosed asthma was high (87%). The proportion of undiagnosed asthmatic subjects among all asthmatic subjects (36.6%) did not differ significantly between subjects selected randomly or by history. The prevalence of any positive test result among 256 non-asthmatic subjects in the random group was 16.0% (not significantly different from the expected value 1−(0.95)4=18.5% for four independent tests), and the symptom prevalence was 12.1%. Thus, about eight subjects (16% of 12% (1.9%) of 435 subjects with no previous diagnosis of asthma) may have been misclassified as having asthma by chance. After correction for this the proportion of asthmatic patients not previously diagnosed was 29% (18/(18+45)).

Undiagnosed versus diagnosed asthma

Individual regression data for the 21 variables selected for logistic regression are shown in table 1. Adjusted odds ratios for independently contributing risk factors are given in table 2. Undiagnosed asthma was independently associated with self reported problems in the family (“we have very stressful problems in our family” (highest of three levels)), daily exposure to environmental tobacco smoke (“for how many hours a day are you usually exposed to indoor tobacco smoking”), low physical activity (“state average number of hours a week spent with physical activities”), high body mass index, and the absence of serial sneezing (“attacks of more than three consecutive sneezes”)). No significant interactions between these factors were found.

Table 1.

Unadjusted associations of selected risk factors with undiagnosed asthma as opposed to asthma diagnosed by doctor

| Risk factor and categories | Mean* or proportion in subjects with asthma | Odds ratio | P value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sex (female v male) | 33/71 | 4.50 | 0.005 |

| Body mass index† (per kg/m2) | 19.9* | 1.24 | 0.03 |

| Systolic blood pressure (per mm Hg) | 116* | 1.04 | 0.07 |

| Symptoms on exercise at 10 years (any v none) | 22/61 | 0.12 | 0.008 |

| Problems in family† (severe v trivial) | 6/70 | 3.82 | 0.14 |

| Living with father (yes v no) | 56/70 | 0.36 | 0.09 |

| Passive smoking† (per hours/day) | 2.3* | 1.46 | 0.005 |

| Type of home (apartment v house) | 11/70 | 3.68 | 0.06 |

| Pet in bedroom (yes v no) | 30/71 | 2.11 | 0.14 |

| Carpets in bedroom (yes v no) | 46/71 | 7.33 | 0.004 |

| Physical activity† (per hours/week) | 9.0* | 0.86 | 0.004 |

| Spare time spent sitting (more v less than half) | 18/71 | 5.57 | 0.004 |

| Given up sport (yes v no) | 21/64 | 0.39 | 0.12 |

| Biking to school (yes v no) | 53/69 | 12.4 | 0.02 |

| Diarrhoea before age 1 (frequent v none) | 12/69 | 0.12 | 0.05 |

| Itching eyes (yes v no) | 39/70 | 0.25 | 0.008 |

| Serial sneezing† (yes v no) | 33/70 | 0.14 | 0.0007 |

| Watery nasal secretion (yes v no) | 26/70 | 0.12 | 0.002 |

| Diet restrictions (yes v no) | 26/70 | 0.36 | 0.07 |

| Headache (monthly) (yes v no) | 24/71 | 2.36 | 0.10 |

| Stomach ache (monthly) (yes v no) | 21/71 | 2.57 | 0.08 |

N=62 for passive smoking, ⩾69 for other continuous variables.

Included in final model (see table 2).

Table 2.

Associations of independent risk factors with undiagnosed asthma as opposed to asthma diagnosed by doctor

| Risk factor and categories | No of subjects | Odds ratio (95% CI)* | χ2 (df=1) | P value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Body mass index (per kg/m2) | 59 | 3.01 (1.16 to 7.83) | 5.12 | 0.02 |

| Problems in family (serious v trivial) | 59 | 846 (2.22 to ∞) | 4.94 | 0.03 |

| Passive smoking (per hours/day) | 59 | 2.39 (1.16 to 4.92) | 5.59 | 0.02 |

| Physical activity (per hours/week) | 59 | 0.60 (0.41 to 0.87) | 7.24 | 0.01 |

| Serial sneezing (any v none) | 59 | 0.005 (0.00 to 0.34) | 5.99 | 0.01 |

Adjusted for all factors included in model.

Among those with diagnosed asthma only 33% (95% confidence interval 20% to 49%) were girls compared with 69% (48% to 86%) among those undiagnosed (P=0.007). The sex distribution was about neutral in the “symptoms only” group (52% (36% to 68%) girls) and in the reference group (45% (37% to 54%) girls). A negative association was found between female sex and physical activity (odds ratio 0.91 (0.84 to 1.00) per hours/week, χ2=4.12, df=1, P=0.04, n=59), whereas female sex and problems in the family were positively associated (14.8 (1.0 to 220), χ2=3.97, df=1, P=0.05, n=59).

Cough was equally prevalent among diagnosed (58%) and undiagnosed subjects (58%), but the latter group reported less breathing trouble (50% v 100%, P<0.001) and wheezing (35% v 96%, P<0.001). Among undiagnosed subjects only 31% had reported any asthma-like symptom to a doctor. Subjects with diagnosed asthma had a significantly higher response to inhaled methacholine than did undiagnosed subjects with asthma (median methacholine dose response slope 12.0 v 4.8 μmol/l, P=0.02), whereas the results of baseline spirometry, exercise provocation, and peak flow monitoring did not differ between groups. No significant differences in test results were found between those subjects without asthma who had symptoms but negative test results and the reference group.

Undiagnosed asthma versus symptoms only

Among symptomatic subjects not previously diagnosed with asthma, independent risk factors (see box) for having undiagnosed asthma as opposed to asthma-like “symptoms only” were bronchitis at age 10 (odds ratio 7.35 (1.52 to 35.4), χ2=6.2, df=1, P=0.01), signs of humidity in home (0.28 (0.08 to 1.00), χ2=3.81, df=1, P=0.05), and physical activity (0.89 (0.79 to 1.00), χ2=3.80, df=1, P=0.05). The odds ratios stated were adjusted for all contributing variables (n=66, two missing). No significant interactions were found between the variables contributing to model.

Discussion

Few studies have investigated the characteristics of previously undiagnosed asthmatic patients, probably in part because of the lack of an accepted definition of this condition and the need for objective measurements to confirm the diagnosis to avoid overestimation.19 For epidemiology a pragmatic definition of asthma as the coexistence of recent wheeze and methacholine hyperresponsiveness has been proposed.20 Cough, however, may be the sole expression of asthma,21 and various tests of airway responsiveness may identify different types of abnormalities of the airways.12 Therefore, we extended our definition of asthma to comprise non-infectious cough or any breathing trouble, or both, in combination with any test result confirming abnormal variations in airway calibre including monitoring of peak expiratory flow, airway responsiveness to methacholine or exercise, and resting spirometry. By this definition subjects with previously undiagnosed asthma made up about one third of all asthmatic patients identified. True asthmatic patients were unlikely to hide in the “symptoms only” group because test results did not differ between those with symptoms but negative test results and reference subjects without symptoms.

Undiagnosed versus diagnosed asthma

Independent risk factors for undiagnosed as opposed to previously diagnosed asthma were serious family problems, low physical activity, high body mass index, high exposure to environmental tobacco smoke, and no history of serial sneezing, a characteristic symptom of allergic rhinitis. The first two of these risk factors were significantly associated with female sex, which, in accordance with previous reports,6,8 comprised two thirds of the undiagnosed but only one third of the diagnosed patients with asthma.

The logistic regression analysis was based on a relatively large number of potential risk factors (n=51) compared with the number of asthmatic subjects identified (n=71). Thus, mass significance could not be excluded. The relevance of the five independent risk factors, however, was supported by the presence of several associated factors competing for entry in the final model (see table 1).

Why is asthma overlooked?

The presence of one or more of the five independent risk factors could in several ways lead to misinterpretation or neglect of asthma-like symptoms by patients, parents, or medical professionals. A low level of physical activity is relatively unlikely to provoke symptoms of asthma induced by exercise and may serve as a means of self “treatment” in childhood asthma. Furthermore, low activity promotes weight gain (high body mass index) which in turn may lead to misinterpretation of asthma symptoms as due to lack of physical fitness. Social status, previously associated with underdiagnosis of asthma,9 was not directly measured but may be related to parents’ smoking habits as well as problems in the family. Family problems may reduce focus on a child’s symptoms, and parents who smoke may be disinclined to get a doctor’s advice regarding symptoms related to smoking in the family. Environmental tobacco smoke has previously been shown to be a risk factor for childhood wheeze22 and is likely to be strongly advised against and thus probably reduced when a child is diagnosed with asthma.

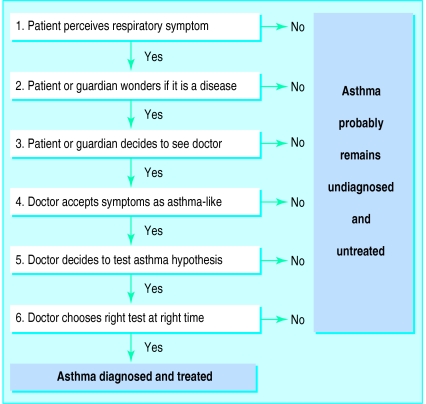

In accordance with previous reports,6 symptoms were rarely reported to a physician by undiagnosed subjects with asthma, who thereby effectively avoided getting diagnosed and properly treated. Cough seemed to be particularly overlooked as an expression of asthma. Even though the more severely affected patients with asthma (in terms of airway responsiveness and symptoms) were also the most likely to get diagnosed, several moderately to severely affected subjects were first identified as a result of the present study.

The role of atopy as a risk factor for asthma has been established by population based studies with physician independent markers of asthma such as lung function impairment, bronchial responsiveness to methacholine, or typical asthma symptoms.23–25 We speculate, however, that the traditional emphasis on two associated risk factors26 for asthma—namely, atopy and male sex—may have led to the underrecognition of non-atopic girls with asthma suggested by our data. It seems likely that allergy affecting nose or eyes facilitates a diagnosis of asthma, both by promoting contact with a doctor and by increasing the doctor’s awareness towards this diagnosis.

Undiagnosed asthma versus symptoms only

Undiagnosed patients with asthma also differed from those with symptoms but with no evidence of asthma. In this context, previously undiagnosed asthma at age 13 was positively associated with symptoms of bronchitis—that is, periodic cough for many days or weeks—at age 10, confirming earlier reports on misclassification of asthma as bronchitis4 and suggesting that the asthma had been unrecognised for several years. The negative association between undiagnosed asthma and the level of physical activity suggests that exercise induced symptoms limit the activity level in undiagnosed subjects more than in subjects with respiratory symptoms unrelated to asthma. The independent association of indicators of high humidity in the home with non-asthmatic respiratory symptoms was unexpected but may be related to indoor microbial factors.27

Summary

Substantial underdiagnosis of asthma in the adolescent population was confirmed by combined subjective and objective criteria. Underdiagnosis was independently associated with low physical activity, high body mass, serious family problems, passive smoking, and the absence of rhinitis symptoms. Girls were overrepresented among subjects with undiagnosed asthma and equally underrepresented among those with diagnosed asthma, indicating sex bias in the diagnostic process. Most patients with undiagnosed asthma had not reported their symptoms to a physician, suggesting a need for targeted asthma campaigns in the community.

Acknowledgments

We thank the participants, their parents, and the schools involved for their cooperation, and Ellen Møhl, Birgitte Pedersen, and Susanne Berntsen for skilful technical help.

Footnotes

Funding: Danish Medical Research Council, Danish National Association against Lung Diseases, Danish Asthma and Allergy Association, the Højbjerg Foundation, and Odense University.

Conflict of interest: None.

References

- 1.Sears MR. Epidemiological trends in bronchial asthma. In: Kaliner MA, Barnes PJ, Persson CGA, editors. Asthma: its pathology and treatment. New York: Marcel Dekker; 1991. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Speight AN. Is childhood asthma being underdiagnosed and undertreated? BMJ. 1978;29:331–332. doi: 10.1136/bmj.2.6133.331. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Nish WA, Schwietz LA. Underdiagnosis of asthma in young adults presenting for USAF basic training. Ann Allergy. 1992;69:239–242. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Speight AN, Lee DA, Hey EN. Underdiagnosis and undertreatment of asthma in childhood. BMJ. 1983;286:1253–1256. doi: 10.1136/bmj.286.6373.1253. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cuijpers C, Wesseling GJ, Swaen GMH, Sturmans F, Wouters EFM. Asthma-related symptoms and lung function in primary school children. J Asthma. 1994;31:301–312. doi: 10.3109/02770909409089477. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kolnaar BGM, Beissel E, van den Bosch WJHM, Folgering H, van den Hoogen HJM, van Weel C. Asthma in adolescents and young adults: screening outcome versus diagnosis in general practice. Fam Pract. 1994;11:133–140. doi: 10.1093/fampra/11.2.133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Mostgaard G, Siersted HC, Hansen HS, Hyldebrandt N, Oxhøj H. Reduced forced expiratory flow in schoolchildren with respiratory symptoms: the Odense schoolchild study. Resp Med. 1997;91:443–448. doi: 10.1016/s0954-6111(97)90108-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kuhni CE, Sennhauser FH. The Yentl syndrome in childhood asthma: risk factors for undertreatment in Swiss children. Pediatr Pulmonol. 1995;19:156–160. doi: 10.1002/ppul.1950190303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Baumann A, Young L, Peat JK, Hunt J, Larkin P. Asthma underrecognition and undertreatment in an Australian community. Aust NZ J Med. 1992;22:36–40. doi: 10.1111/j.1445-5994.1992.tb01706.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Duran-Tauleria E, Rona RJ, Chinn S, Burney P. Influence of ethnic group on asthma treatment in children in 1990-1: national cross sectional study. BMJ. 1996;313:148–152. doi: 10.1136/bmj.313.7050.148. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hansen HS, Hyldebrandt N, Nielsen JR, Froberg K. Blood pressure distribution in a school-age population aged 8-10 years: the Odense schoolchild study. J Hypertens. 1990;8:641–646. doi: 10.1097/00004872-199007000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Siersted HC, Mostgaard G, Hyldebrandt N, Hansen HS, Boldsen J, Oxhøj H. Interrelationships between diagnosed asthma, asthma-like symptoms, and abnormal airway behaviour in adolescence: the Odense schoolchild study. Thorax. 1996;51:503–509. doi: 10.1136/thx.51.5.503. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Tanner JM, Whitehouse RH. Clinical longitudinal standards for height, weight, height velocity, weight velocity, and stages of puberty. Arch Dis Childhood. 1976;51:170–179. doi: 10.1136/adc.51.3.170. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Quanjer PhH, ed. Standardized lung function testing. Report of the working party on standardization of lung function tests, European Community for Coal and Steel. Bull Europ Physiopath Respir 1983;19 (suppl 5):1-95. [PubMed]

- 15.Yan K, Salome C, Woolcock AJ. Rapid method for measurement of bronchial responsiveness. Thorax. 1983;38:760–765. doi: 10.1136/thx.38.10.760. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.O’Connor G, Sparrow D, Taylor D, Segal M, Weiss S. Analysis of dose-response curves to methacholine. An approach suitable for population studies. Am Rev Respir Dis. 1987;136:1412–1417. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm/136.6.1412. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Siersted HC, Hansen HS, Hansen N-CG, Hyldebrandt N, Mostgaard G, Oxhøj H. Evaluation of peak expiratory flow variability in an adolescent population sample. The Odense schoolchild study. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 1994;149:598–603. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.149.3.8118624. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Norusis MJ. SPSS/PC+ advanced statistics version 4.0. Chicago: SPSS; 1990. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Joyce DP, Chapman KR, Kesten S. Prior diagnosis and treatment of patients with normal results of methacholine challenge and unexplained respiratory symptoms. Chest. 1996;109:697–701. doi: 10.1378/chest.109.3.697. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Toelle BG, Peat JK, Salome CM, Mellis CM, Woolcock AJ. Toward a definition of asthma for epidemiology. Am Rev Respir Dis. 1992;146:633–637. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm/146.3.633. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hannaway PJ, Hopper GD. Cough variant asthma in children. JAMA. 1982;247:206–208. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Cunningham J, O’Connor GT, Dockery DW, Speizer FE. Environmental tobacco smoke, wheezing, and asthma in children in 24 communities. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 1996;153:218–224. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.153.1.8542119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Peat JK, Britton WJ, Salome CM, Woolcock AJ. Bronchial hyperresponsiveness in two populations of Australian schoolchildren. II. Relative importance of associated factors. Clin Allergy. 1987;17:283–290. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2222.1987.tb02016.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Clough JB, Williams JD, Holgate ST. Effect of atopy on the natural history of symptoms, peak expiratory flow, and bronchial responsiveness in 7- and 8-year-old children with cough and wheeze. Am Rev Respir Dis. 1991;143:755–760. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm/143.4_Pt_1.755. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Sears MR, Burrows B, Herbison GP, Flannery EM, Holdaway MD. Atopy in childhood. III. Relationship with pulmonary function and airway responsiveness. Clin Exp Allergy. 1993;23:957–963. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2222.1993.tb00281.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Sears MR, Burrows B, Flannery EM, Herbison GP, Holdaway MD. Atopy in childhood. I. Gender and allergen related risks for development of hay fever and asthma. Clin Exp Allergy. 1993;23:941–948. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2222.1993.tb00279.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Husman T. Health effects of indoor-air microorganisms. Scand J Work Environ Health. 1996;22:5–13. doi: 10.5271/sjweh.103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]