Abstract

PROBLEM

Korean American adolescents tend to experience more mental health problems than adolescents in other ethnic groups.

METHODS

The goal of this study was to examine the association between Korean American parent-adolescent relationships and adolescents’ depressive symptoms in 56 families.

FINDINGS

Thirty-nine percent of adolescents reported elevated depressive symptoms. Adolescents’ perceived low maternal warmth and higher intergenerational acculturation conflicts with fathers were significant predictors for adolescent depressive symptoms.

CONCLUSIONS

The findings can be used to develop a family intervention program, the aim of which would be to decrease adolescent depressive symptoms by promoting parental warmth and decreasing parent-adolescent acculturation conflicts.

Search Terms: Korean American, depression, parental warmth, parental control, parent-adolescent conflict

Elevated depressive symptoms are one of the most prevalent mental health problems among adolescents; they are increasing, recurring, and associated with poor school performance, delinquency, running away, substance abuse, and suicide (Hale, Van Der Valk, Engels, & Meeus, 2005; Saluja et al., 2004). Increasing evidence shows that adolescent depressive symptoms are related to the quality of relationships between adolescents and their parents. Adolescents tend to experience elevated levels of depressive symptoms when they perceive their parents to be low in warmth but high in control (Hale et al., 2005; Rapee, 1997), and when they experience more frequent conflicts with their parents (Sheeber, Hops, Alpert, Davis, & Andrews, 1997). These findings are true for both European American and Asian American adolescents (Greenberger & Chen, 1996).

Although Greenberger and Chen’s (1996) sample included both Chinese and Korean American adolescents, data from the two ethnic groups were combined for analysis. Therefore, this association is not known specifically for Korean American adolescents, who tend to experience more mental health problems than European American adolescents (Choi, Stafford, Meininger, Roberts, & Smith, 2002) or Chinese and Japanese American adolescents (Yeh, 2003). The goal of this study was to examine the associations between perceived parent-adolescent relationships and depressive symptoms in Korean American adolescents. The research questions were: (1) how are parent-adolescent relationships (i.e., parental warmth, parental control, and intergenerational acculturation conflicts) associated with adolescents’ depressive symptoms? (2) of the three factors (i.e., parental warmth, parental control, and intergenerational acculturation conflict) which one is the most significant contributing factor to adolescent depressive symptoms? and (3) how does the frequency of common parent-adolescent conflict situations contribute to adolescents’ depressive symptoms?

THEORETICAL FRAMEWORK

Parental warmth and control are considered to be important dimensions of parenting (Maccoby & Martin, 1983). According to the parental acceptance-rejection theory (Rohner, 2007; Rohner, Khaleque, & Cournoyer, 2007), parents can be placed on a continuum between acceptance and rejection based on how warm they are toward their adolescents. Warm parents are accepting and affectionate. When parents are low in warmth, they tend to be cold, hostile, indifferent, undifferentiating, and rejecting. Parental control ranges from permissiveness to strictness. Permissive parents exercise minimum control over their children and allow adolescents to do things their own way. Moderately controlling parents set a few clear limits and then allow adolescents to regulate their own activities within these constraints. Firm parents guide the adolescents’ behavior by a firm schedule and parental intervention. Restrictive parents enforce many rules on their adolescents’ behaviors, and by doing so, limit the adolescent's autonomy (Rohner, 2007).

REVIEW OF LITERATURE

Depressive Symptoms in Adolescents

Overall, 1 in 6 adolescents living in the United States reports depressive symptoms (Saluja et al., 2004). Depressive symptoms were most prevalent among American Indian adolescents (29%), followed by European American (22%), Mexican American (18%), Asian American (17%), and African American (15%) adolescents (Saluja et al.). Symptoms often include depressed mood (e.g., feelings of sadness, loneliness, and crying); unhappiness (e.g., not enjoying life, feeling unhopeful); somatic complains (e.g., being bothered, restless sleep, change in appetite); and interpersonal difficulty (e.g., feeling that people dislike them) (Bonnie, 2006; Radloff, 1991). This study defines elevated depressive symptoms as being present when adolescents score higher than 16 on the Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale (CES-D) (Radloff, 1977, 1991).

Factors related to depressive symptoms included gender and functional impairment, parental rejection, primary caretaker’s psychopathology, negative discipline, parental discord, poor parent-child attachment, poor parent-child involvement, and exposure to violence, neglect, physical abuse, sexual abuse, and assault (Gonzales-Tajera et al., 2005). Among all these factors, the importance of the quality of parent-adolescent relationships has been increasingly emphasized. Specifically, low parental warmth or care, high parental rejection, high parental control, overprotection, parental harshness, inconsistent discipline, hostility, and high family conflict are related to depressive symptoms in adolescents (Heaven, Newbury, & Mak, 2004; Zuniga de Nuncio, Nader, Sawyer, & Guire, 2003).

Cultural Contexts and Adolescent Depressive Symptoms

Adolescent depressive symptoms need to be understood within cultural contexts because factors related to these symptoms differ slightly between European American and Asian/Asian American adolescents (Choi, 2002). For example, the quality of family relationships (i.e., parental warmth and conflicts with parents) and their grades in school were significantly linked with depressive symptoms among Chinese adolescents living in China than among American adolescents (53% European, 16% Latino, 12% Asian, 11 % African, and other) living in the United States (Greenberger, Chen, Tally, & Dong, 2000). Within the United States, the ethnic differences found in connection with depressive symptoms were not evident between European and Asian (Chinese and Korean) American young adolescents (Greenberger & Chen, 1996). But in late adolescence, Asian American adolescents exhibited elevated depressive symptoms, perceived lower parental warmth, and experienced higher frequency of parent-adolescent conflicts than their European American counterparts (Greenberger & Chen, 1996). Other factors related to the depressive symptoms of predominantly Chinese American adolescents included harsh parental discipline, a lack of supervision, and low inductive reasoning (S. Y. Kim & Ge, 2000), as well as more negative peer relationships, a rejection of American culture, and immigration to the United States after age 12 (Wong, 2001). This relationship is not known for Korean American adolescents.

Korean American Parenting

Korean Americans compose one of the largest Asian American populations in the United States (H. Kim, Do, & Park, 2005). However, relatively little is known about this population. In general, Korean Americans are voluntary migrants who came to the United States seeking more political and social security, as well as better educational opportunities for their children (K. Shin & Shin, 1999). Researchers have found that Korean American parents are warm and sensitive (E. Kim, 2005b; E. Kim & Hong, in press). Korean mothers especially have been shown to interact sensitively with their children by reading and responding to their children’s subtle cues (E. Kim & Hong, in press). In spite of their warmth, however, Korean American parents are not accustomed to expressing this warmth to their children through hugs, kisses, praise, and saying, “I love you,” which are the common parenting practices in the United States (E. Kim & Hong, in press). Under Confucianism, parents are trained to suppress rather than to express their emotions, and therefore, such expression is difficult for them. Korean American parents also ask their adolescents to obey them without talking back or questioning their authority because that was how they were raised as children. Therefore, these parents tend to be described as authoritarian, characterized by a lack of affection, a lack of communication, and by their stress on absolute obedience (E. Kim, 2005a). However, it is not known how Korean American parenting (i.e., warmth and control) is linked to adolescents’ depressive symptoms.

Intergenerational Acculturation Conflicts and Depressive Symptoms

The generation gap or intergenerational conflict has often been examined to understand the nature of parent-adolescent conflict within Western culture (R. M. Lee, Choe, Kim, & Ngo, 2000). Higher conflicts with their parents tend to be related to elevated depressive symptoms in adolescents (Greenberger, Chen, Tally, & Dong, 2000). In Korean American families, parent-adolescent conflicts are more complicated than a European American intergenerational gap or conflicts. Korean American families are influenced by two cultural values (i.e., Korean culture and American culture), and adolescents generally acculturate to the majority culture at a faster rate than their parents (R. M. Lee et al.). This situation creates acculturation conflicts in families and threatens the traditional hierarchical relationships between parents and adolescents (Choi, 2002). For example, Korean American adolescents often hear their parents saying, “You are too Americanized and don’t act like a proper Korean teen,” while adolescents think, “My parents are being too traditional.” This kind of conflict needs to be understood within the framework of intergenerational acculturation conflicts.

Intergenerational acculturation conflict in Korean American families may be more critical in father-adolescent relationships than mother-adolescent relationships. E. Kim (2005b) found that Korean American adolescents and mothers were in agreement in perceiving higher control as lower maternal warmth. Korean American fathers, however, perceived higher control as a manifestation of high warmth, whereas adolescents perceived it as a sign of lower warmth. Korean American adolescents experienced higher intergenerational conflicts than Chinese and Japanese American adolescents (Yeh & Inose, 2002). In Chinese American families, the perceived acculturation disparity was related to father-child conflicts, but not to mother-child conflicts (Fu, 2002). Due to the similarities between Chinese and Korean culture, the conflicts coming from the differences in acculturation may have more impact in father-adolescent relationships than mother-adolescent relationships in Korean American families as well. However, it is not known how intergenerational acculturation conflicts are related to depressive symptoms in Korean American adolescents.

METHOD

Participants

The convenience sample consisted of 56 Korean American adolescents (25 girls and 31 boys) recruited from Korean American churches and language schools in the Pacific Northwest. Inclusion criteria were: (1) the adolescent was between the ages of 11 and 17, (2) both parents were Korean Americans, and (3) the family lived in the United States at the time of the study. Table 1 summarizes demographic characteristics of adolescents and their mothers and fathers. Overall, adolescents’ mean age was 13 and they had lived in the United States approximately 10 years. Their mothers’ average age was 43 and they had lived in the United States for 11 years, whereas fathers mean age was 47 and they had lived in the United States for 18 years.

Table 1.

Demographic characteristics of adolescents and their mothers and fathers (N = 56)

| Demographic characteristics | Adolescents M (SD)/n (%) |

Fathers M (SD) |

Mothers M (SD) |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age in years | 13.36 (1.81) | 46.98 (3.65) | 43.21 (2.67) | |||

| U.S. residency in years | 10.26 (4.39) | 18.36 (8.18) | 11.35 (9.06) | |||

| Education in years | 15.96 (2.40) | 14.91 (2.35) | ||||

| Working hours per week | 52.23 (16.54) | 27.18 (16.63) | ||||

| Ethnic identity of adolescents | Korean American | 39 (70%) | ||||

| Korean | 13 (23%) | |||||

| American | 0 (0%) | |||||

| Missing | 4 (7%) | |||||

| Family income | > $ 60,000 | 43 (76%) | ||||

Instrumentation

Adolescents filled out four self-report instruments as described in below.

Depressive symptoms

The Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale (CES-D, Radloff, 1977), developed for the general community population, was used to assess Korean American adolescent depressive symptoms. The CES-D consists of 20 items that include negative affect (i.e. blues, depressed, lonely, cry, sad); positive affect (i.e. good, hopeful, happy, enjoy); somatic complains (i.e. appetite, sleep); and interpersonal difficulty (i.e. unfriendly, dislike). It utilizes a 4-point Likert-type scale from “rarely, less than 1 day/week” to “almost or all of the time, 5–7 days/week.” Scores range from 0 to 60 with a higher score indicating elevated depressive symptoms. A score over 16 is considered being “positive” for depressive symptoms. Cronbach’s alpha for the current study sample was .89.

Parental warmth

The Parental Acceptance-Rejection portion of the Parental Acceptance-Rejection/Control Questionnaire (PARQ/Control, Rohner, 1991) was used to assess adolescents’ views of maternal and paternal warmth. It is a 60-item, 4-point Likert-type scale instrument (1 = almost always true to 4 = almost never true). Four subscales include parental warmth/affection, hostility/aggression, indifference/neglect, and undifferentiated rejection. Total PARQ scores range from 60–240; higher scores indicate lower parental warmth. Sample questions include: “My mother/father says nice things about me (warmth)”; “My mother/father is irritable with me (hostility)”; “My mother/father forgets events that I think she/he should remember (indifference)”; and “I wonder if my mother/father really loves me (undifferentiated rejection)” (Rohner, 1991). Rohner (1991) has reported evidence for convergent, discriminant, and construct validity for the PARQ. Cronbach’s alpha for the current study sample was .74 for paternal warmth and .63 for maternal warmth.

Parental control

The Control portion of the PARQ/Control (Rohner, 1991) was used to measure adolescents’ perceptions of parental control. It is a 13-item, 4-point Likert-type scale instrument (1 = almost always true to 4 = almost never true). Scores on the Control Questionnaire range from 13 to 52, with higher scores indicating higher control. Sample question item includes “My mother/father tells me exactly what time to be home when I go out.” Cronbach’s alpha for the current study sample was .71 for paternal control and .67 for maternal control.

Intergenerational acculturation conflicts

Adolescents’ perceptions of intergenerational acculturation conflicts were measured with the Asian American Family Conflict Scale (R. M. Lee et al., 2000). It is a 10-item scale that measures the frequency of Asian American parent-adolescent intergenerational and acculturation conflicts in 10 typical disagreements over values and practices. Sample items include, “I have done well in school, but my parents’ academic expectations always exceed my performance.” Respondents answer on a 5-point Likert-type scale (1 = almost never to 5 = almost always). Scores range from 10 to 50; higher scores indicate a higher frequency of parent-adolescent conflict. Cronbach’s alpha for the current study sample was .82 for father-adolescent conflict and .85 for mother-adolescent conflict.

Data Analysis

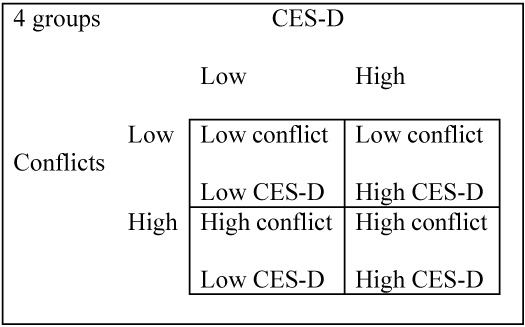

Descriptive statistics including means, standard deviations, ranges, and distributions were calculated using SPSS (Norusis, 2006). Differences between mother-adolescent relationships and father-adolescent relationships were examined using paired t-tests. Then, research questions were analyzed using Pearson correlations, regression, ANOVA, and Chi-square test as outlined in Table 2. To analyze the third question, the adolescents were divided into two groups: low (i.e., those who had a frequency of “almost never” or “once in a while”) and high (i.e., those who had frequency of conflict by answering “sometimes,” “often,” and “almost always”) conflict groups. The CES-D score was calculated for low and high group adolescents for each intergenerational acculturation conflict item. ANOVA was used to examine mean differences between low and high conflict groups. Then, to check for prevalent differences, adolescents in the low conflict group were divided into those who had CES-D scores lower than 16 and those who had scores of 16 and over. The same division was done for the high conflict adolescent group, yielding 4 groups: low conflict and low CES-D, low conflict and high CES-D, high conflict and low CES-D, and high conflict and high CES-D. The distribution of adolescents for each group was calculated and the distribution differences were tested using Chi-square.

Table 2.

Data analysis plan

| Research question | Data analysis plan |

|---|---|

| 1. Association between parent-adolescent relationships and adolescents’ depressive symptoms |

Pearson correlations |

| 2. The most important parent-adolescent relationship factor in contributing to adolescent depressive symptoms |

Regression analysis |

| 3. Association between the frequency of parent-adolescent conflicts and adolescents’ depressive symptoms |

ANOVA Chi-square test |

|

RESULTS

Table 3 shows means and standard deviations for each study variable. The paired sample t-test indicated that Korean American adolescents did not perceive a difference between maternal and paternal warmth. Adolescents perceived mothers as significantly more controlling than fathers. Means for intergenerational acculturation conflicts showed a trend of adolescents’ perceiving higher conflicts with mothers than fathers. The mean CES-D score showed 39.3% (N = 22) of adolescents scored higher than 16, the indication of being “positive” for depressive symptoms. None of the demographic variables were related to depressive symptoms.

Table 3.

Means, standard deviations, and intercorrelations among study variables (N = 56)

| Warmth | Control | Conflict | Depressive symptoms |

Father- Adolescent |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Warmth | ___ | .33* | .56*** | .34** | 110.51 (25.25) |

| Control | .30* | ___ | .38** | .20 | 34.56 (5.31) |

| Conflicts | .63*** | .51*** | ___ | .49*** | 22.65 (9.01) |

| Depressive symptoms |

.53*** | .28* | .48*** | ___ | 15.17 (10.77) |

| Mother- Adolescent |

107.06 (24.36) |

35.85 (5.13) |

23.59 (9.02) |

15.17 (10.77) |

___ |

Note. The upper right side indicates father- adolescent relationships, and the lower left side indicates mother-adolescent relationships.

p<.05,

p< .01,

p< .001 (2-tailed).

The first research question was ‘how are parent-adolescent relationships (i.e., parental warmth, parental control, and intergenerational acculturation conflicts) associated with adolescents’ depressive symptoms?’ As shown in Table 3, lower maternal warmth, higher maternal control, and higher intergenerational conflicts were positively correlated with adolescents’ elevated depressive symptoms for mother-adolescent relationships. For father-adolescent relationships, lower paternal warmth, and higher intergenerational conflict also were associated with adolescents’ elevated depressive symptoms. However, paternal control was not correlated with adolescents’ elevated depressive symptoms.

The second research question was ‘of the three factors (i.e., parental warmth, parental control, and intergenerational acculturation conflict), which one is the most significant contributing factor to adolescent depressive symptoms?’ As shown in Table 4, both the father-adolescent relationship model and mother-adolescent relationship model were significant. The father model explained 25% of the variance in adolescent depressive symptoms, and the mother model explained 32% of the variance. However, a comparison of unstandardized beta weights suggests that the magnitude of association between parent-adolescent relationships and adolescent depressive symptoms was subsequently different between the fathers’ and mothers’ models. For the fathers’ model, intergenerational conflict was the significant factor. For the mothers’ model, maternal warmth was the significant factor.

Table 4.

Unstandardized Coefficients for Regression of Depressive Symptoms on Measures of Father-Adolescent and Mother-Adolescent Relationships (N = 56)

| Variable | Father-adolescent relationships | Mother-adolescent relationships |

|---|---|---|

| B (SE) | B (SE) | |

| Warmth | .04 (.06) | .17 (.07)* |

| Control | .01 (.27) | .13 (.28) |

| Conflict | .52 (.18)** | .26 (.20) |

| ΔR² | .25 | .32 |

| ΔF | 5.72** | 8.13*** |

Note.

p<.05,

p< .01,

p< .001 (2-tailed).

The third research question was ‘how does the frequency of common parent-adolescent conflict situations contribute to adolescents’ depressive symptoms?’ It was tested with two sub-groups of adolescents using each of the 10 items on the Asian American Family Conflict Scale (R. M. Lee et al., 2000).The low conflict group included adolescents who answered “almost never” to “once in a while.” The high conflict group included adolescents who answered from “sometimes” to “almost always.” As shown in Table 5, adolescents in the high conflict group had CES-D scores over 16, compared to the low conflict group adolescents who scored below 16. Principally, the differences between the high and low conflict group adolescents were significant in 6 out of 10 items: academic expectation, sacrificing one’s interests, ways of expressing love, saving face, expressing opinions, and showing respect to the elderly. These 6 items were the same for father-adolescent conflict and mother-adolescent conflict. Next, the distribution of adolescents was examined among the four possible groups using a CES-D score of 16 as a cut-off point. Table 5 shows the same 6 items had significantly different distributions using Chi-square.

Table 5.

CES-D mean score and distribution differences according to high and low intergenerational acculturation conflict in 10 typical disagreements over values and practices (N = 56)

| Father-adolescent conflict | Mother-adolescent conflict | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ANOVA | Chi-square | ANOVA | Chi-square | ||||

| Intergenerational acculturation conflict | Conflict level |

M (SD) |

n CES-D<16 |

n CES-D≥16 |

M (SD) |

n CES-D<16 |

n CES-D≥16 |

| 1. My parent tells me what to do with my life, but I want to make my own decisions. |

Low | 12.96 (10.43) | 19 | 8 | 13.41 (10.80) | 19 | 8 |

| High | 17.81 (11.28) | 13 | 13 | 16.81 (10.66) | 15 | 14 | |

| 2. My parent tells me that a social life is not important at my age, but I think that it is. |

Low | 14.11 (10.46) | 25 | 12 | 13.43 (9.13) | 24 | 12 |

| High | 17.53 (12.24) | 7 | 8 | 18.30 (12.88) | 10 | 10 | |

| 3. I have done well in school, but my parent’s academic expectations always exceed my performance. |

Low | 10.48 (9.05) | 18 | 5 | 10.16 (8.74) | 20 | 5 |

| High | 19.07 (11.08)** | 14 | 16* | 19.21 (10.66)*** | 14 | 17** | |

| 4. My parent wants me to sacrifice personal interests for the sake of family, but I feel this is unfair. |

Low | 11.23 (8.51) | 30 | 9 | 11.53 (8.50) | 29 | 10 |

| High | 26.46 (9.39)*** | 2 | 11*** | 23.06 (11.16)*** | 5 | 11** | |

| 5. My parent always compares me with others, but I want them to accept me for being myself. |

Low | 13.47 (10.30) | 20 | 10 | 13.06 (9.61) | 18 | 8 |

| High | 17.78 (11.68) | 12 | 11 | 17.00 (11.52) | 16 | 14 | |

| 6. My parents argue that they show me love by housing, feeding, and educating me, but I wish they would show more physical and verbal signs of affection. |

Low | 12.74 (9.93) | 29 | 10 | 12.83 (9.96) | 28 | 10 |

| High | 22.57 (11.02)** | 3 | 11*** | 20.11 (11.00)* | 6 | 12** | |

| 7. My parent doesn’t want me to bring shame upon the family, but I feel that my parent is too concerned with saving face. |

Low | 12.89 (9.30) | 26 | 11 | 12.49 (9.13) | 27 | 10 |

| High | 21.00 (12.84)* | 6 | 10* | 20.40 (12.00)** | 7 | 12** | |

| 8. My parent expects me to behave like a proper Korean boy or girl, but I feel my parent is being too traditional. |

Low | 13.48 (11.34) | 21 | 10 | 14.00 (11.10) | 21 | 11 |

| High | 17.95 (10.25) | 11 | 11 | 16.73 (10.32) | 13 | 11 | |

| 9. I want to state my opinion, but my parent considers it to be disrespectful to talk back. |

Low | 11.03 (11.03) | 24 | 6 | 10.17 (8.55) | 24 | 5 |

| High | 20.96 (11.01)*** | 8 | 15*** | 20.54 (10.42)*** | 10 | 17*** | |

| 10. My parent demands that I always show respect for elders, but I believe in showing respect only if they deserve it. |

Low | 10.82 (7.67) | 25 | 8 | 10.69 (7.79) | 25 | 7 |

| High | 22.80 (11.82)*** | 7 | 13** | 21.15 (11.40)*** | 9 | 15** | |

| Total conflict score | Low | 11.33 (8.88) | 21 | 6 | 10.04 (7.81) | 19 | 4 |

| High | 18.74 (11.27)** | 13 | 16* | 18.74 (11.19)** | 15 | 18** | |

Note. Conflict level: Low conflict (“almost never” to “once in a while”), high conflict (“sometimes” to “almost always”)

p<.05,

p< .01,

p< .001 (2-tailed).

DISCUSSION

This study examined the association between perceived parent-adolescent relationships and depressive symptoms among Korean American adolescents. Overall, Korean American adolescents reported their mothers and fathers as warm and moderately controlling. In addition, adolescents perceived mothers as more controlling than fathers. This finding is consistent with previous findings among Korean American adolescents in the Midwest (E. Kim, 2005b). The mean score of adolescents’ perceived intergenerational acculturation conflicts was 23.50 (SD=9.02). This score is lower than what R. M. Lee et al. (2000) found among Asian American (i.e., Chinese, Vietnamese, Filipino, Korean, Japanese, etc) college students (age 16–52), which ranged from 27.39 (SD = 9.44) to 31.72 (SD = 7.66). The differences may be related to characteristics of the different samples used in these two studies; participants of the present study were much younger and they were all Korean Americans. In Greenberger and Chen’s (1996) study, Asian American college students reported higher scores on conflict with both mothers and fathers than junior high students did.

It is problematic that approximately 40% of Korean American adolescents experienced depressive symptoms. This is particularly of concern since previous studies showed that Korean American adolescents had the poorest mental health among all Asian American adolescents. Using Symptom Checklist 90-Revised, Korean American adolescents (55.69 ±31.40) scored significantly higher than Chinese (32.76 ± 19.70) or Japanese (46.70 ± 27.74) American adolescents (Yeh, 2003). Further, Korean American adolescents were least likely to seek social support (Yeh & Inose, 2002). A recent study found that only 23% of adolescents who met DSM-IV criteria for depressive disorder used mental health services (Essau, 2005). African American and Asian American adolescents were especially likely not to ask for mental health services (Sen, 2004). Furthermore, Korean Americans provide traditional Asian self-care practices and prolonged care within their families that leads to a delay in seeking professional mental health services (J. K. Shin, 2002). These findings suggest the necessity of educating the Korean American population of parents and adolescents about depressive symptoms and the importance of getting appropriate treatment.

Results indicate that the factors related to depressive symptoms are similar across father-adolescent and mother-adolescent relationships. This is consistent with past findings that low parental warmth is an important factor related to adolescent depression (Greenberger & Chen, 1996; Rapee, 1997; Rohner & Britner, 2000). In addition, as stated in Rapee’s review (1997), parental warmth was a more important factor than parental control.

Among three different aspects of the parent-adolescent relationship, low maternal warmth and higher intergenerational acculturation conflict with fathers were the critical factors for predicting adolescents’ depressive symptoms. This finding fits the traditional description of Korean paternal and maternal roles expressed in a popular Korean phrase, ‘om bu ja mo,’ or ‘strict father, benevolent mother’ (Rohner & Pettengill, 1985). When mothers, whose role is prescribed as benevolent, don’t provide warm caring to their offspring, adolescents tend to have elevated depressive symptoms. According to psychodynamic perspectives, when parents fail to meet the child’s psychological needs to feel accepted, it gives rise to adolescent depressive symptoms (Zahn-Waxler, Duggal, & Gruber, 2002).

For the father-adolescent relationship, however, the significant factor was intergenerational acculturation conflict. This result is specifically related to the fact that Korean American fathers hold more traditional views of parent-adolescent relationships than mothers and adolescents. Korean American fathers tend to hold the traditional belief that there should be a distance between adults and offspring in order to maintain the offspring’s respect for their parents (Oak & Martin, 2002). These fathers are not willing to listen to their offspring’s expressions of worry and anxiety (Shrake, 1996). Korean American fathers tend to resist letting go of their authority (E. Kim, 2005b), which possibly creates a greater acculturation gap between fathers and adolescents. Korean American fathers’ attitudes toward their adolescents may cause conflicts with adolescents, and increase adolescents’ depressive symptoms.

Findings indicated that overall, the high conflict group adolescents scored 16 or higher on the CES-D, indicating that they were experiencing elevated depressive symptoms. In particular, the high conflict adolescent group had significantly elevated depressive symptoms as compared to the low conflict group adolescents The situations includes conflicts in academic expectation, sacrificing one’s interests, ways of expressing love, saving face, expressing opinions, and showing respect to the elderly. All of these conflicts are related to traditional Korean Confucian culture and authoritarian parenting style. Coming from Confucian culture, which stresses the importance of education (B. Lee, 2004), 80% of Korean American mothers perceive a ‘B’ as ‘not a good grade’ (Shrake, 1996). When adolescents know the American school’s definition of B is ‘above average,’ their parents’ perception can create conflict between them. Still, adolescents who fail to satisfy their parents with good grades in school feel shamed and depressed (Choi, 2002) and may have suicidal ideation (Jones & Kaderlan-Halsey, 2003).

Korean American parents tend not to express their affection, try to save face, ask their children to obey and respect parents and elders unconditionally (E. Kim & Hong, in press; Shrake, 1996). Coming from collectivistic Confucian culture, where fulfilling obligations is important (U. Kim & Choi, 1994), parents believe that providing clothes, housing, food, and education is the best means of expressing love for their adolescents (Oak & Martin, 2000). However, adolescents who are growing up in the expressive, individualistic American society want to have parents who show more physical and verbal signs of affection (Hong, 2003).

Hierarchical Confucian culture emphasizes unidirectional communication (i.e., from parent to child rather than child to parent). Korean American parents tend to consider assertive and verbally expressive adolescents as problematic and rebellious (Choi, 2002). Stating one’s opinion, which is viewed highly in American schools, is often viewed as talking back and considered disrespectful in the Korean home culture. They get upset when adolescents talk back and tell them not to argue with their parents (Shrake, 1996). They try to impose parental values on adolescents, insist on their adolescents’ obedience, and feel hurt when adolescents don’t follow their parents’ advice (Shrake, 1996). Since normally accepted behaviors and norms in the American school setting are not favorable or acceptable at home, this would cause conflict, which is linked to elevated depressive symptoms in Korean American adolescents. These findings expand existing literature by adding valuable information that these specific conflict situations are related to adolescents’ elevated depressive symptoms.

Limitations

One of the major limitations of this study was the fact that the adolescents’ self-report questionnaires, which were used to measure all study variables and depressive symptoms, can influence various aspects of information processing (Rapee, 1997). Adolescents without depressive symptoms may tend to give positive answers to measures, while adolescents with depressive symptoms may tend to give negative answers to measures, which can induce a false correlation between any two self-reported measures (Duggal, Carlson, Sroufe, & Egeland, 2001). In addition, the adolescents may have elevated depressive symptoms due to reasons other than parent-child interactions. Because the data is not longitudinal, we cannot show that parent-adolescent relationship variables actually lead to differences in adolescents’ depressive symptoms, nor can we rule out the possibility that adolescents who are depressed may simply view the relationships with their parents as more negative than they really are. Other limitations include a small sample size and further division of sample into four groups, wider age range of sample (i.e., 11 to 17 years), and low alpha reliability for maternal warmth (.63) and for maternal control (.67).

Implications for Nursing Practice and Research

The study findings offer nurses several opportunities for reducing Korean American adolescent depressive symptoms. First, it would be important to offer parenting education on how to increase maternal and paternal warmth. Education may include how to express affection to their adolescents. Many Korean American parents are trained not to express their emotions and feelings, therefore showing behavioral and verbal affection toward adolescents is not easy or natural for them (E. Kim & Hong, in press). However, parents need to understand the importance of kisses, hugs, praise, and compliments. Parental warmth needs to be demonstrated to make a positive influence on children (Gordon, 2000). Second, it would be necessary to educate both parents and adolescents about cultural differences between Korea and America and how living in two cultures has potential for creating conflicts between them. When they understand the differences, they are more likely recognize sources and areas of conflicts and they can learn to negotiate and compromise with each other. Public health nurses can collaborate with local Korean American communities to provide this information.

Future research using a longitudinal research design and a larger sample with a narrower age range is necessary in order to observe the stability and change in associations among the study variables as adolescents mature, and must be done in order to increase the generalizability of this study’s findings. Furthermore, a family intervention program aiming to decrease adolescent depressive symptoms by promoting parental warmth and decreasing parent-adolescent conflicts needs to be developed. This intervention should include three modules: an understanding of the cultural differences between Korean and American culture, strategies to increase the expression of parental warmth, and ways to decrease parent-adolescent conflicts.

Acknowledgements

This paper was supported by RIFP and IESUS from the University of Washington and a career development award, NINR #K01 NR08333, given to the first author.

Contributor Information

Eunjung Kim, Assistant Professor, University of Washington.

Kevin C. Cain, Biostatistician, University of Washington.

REFERENCES

- Bonnie L. [Retrieved Jan 22, 2007];Depression in adolescents: Epidemiology, clinical manifestations, and diagnosis. 2006 from www.uptodateonline.com.

- Choi H. Understanding adolescent depression in ethnocultural context. Advances in Nursing Science. 2002;25(2):71–85. doi: 10.1097/00012272-200212000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Choi H, Stafford L, Meininger JC, Roberts RE, Smith DP. Psychometric properties of the DSM Scale for Depression (DSD) with Korean-American youths. Issues in Mental Health Nursing. 2002;23:735–756. doi: 10.1080/01612840260433631. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duggal S, Carlson E, Sroufe LA, Egeland B. Depressive symptomatology in childhood and adolescence. Development and Psychopathology. 2001;13:143–164. doi: 10.1017/s0954579401001109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Essau C. Frequency and patterns of mental health services utilization among adolescents with anxiety and depressive disorders. Depression and Anxiety. 2005;22(3):130–137. doi: 10.1002/da.20115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fu M. Unpublished Dissertation. Los Angeles, CA: Alliant International University; 2002. Acculturation, ethnic identity, and family conflict among first and second generation Chinese Americans. [Google Scholar]

- Gonzales-Tajera G, Canino G, Ramirez R, Chavez L, Shrout P, Bird H, et al. Examining minor and major depression in adolescents. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry. 2005;46(8):888–899. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.2005.00370.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gordon T. Parent Effectiveness Training: The proven program for raising responsible children. New York, NY: Three Rivers Press; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Greenberger E, Chen C. Perceived family relationships and depressed mood in early and late adolescence: A comparison of European and Asian Americans. Developmental Psychology. 1996;32(4):707–716. [Google Scholar]

- Greenberger E, Chen C, Tally S, Dong Q. Family, peer, and individual correlates of depressive symptomatology among U.S. and Chinese adolescents. Journal of Counseling and Clinical Psychology. 2000;68(2):209–219. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.68.2.209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hale WW, Van Der Valk I, Engels R, Meeus W. Does perceived parental rejection make adolescents sad and mad? The association of perceived parental rejection with adolescent depression and aggression. Journal of Adolescent Health. 2005;36:466–474. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2004.04.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heaven PCL, Newbury K, Mak A. The impact of adolescent and parental characteristics on adolescent levels of delinquency and depression. Personality and Individual Differences. 2004;36:173–185. [Google Scholar]

- Hong S. The identity profiles of the 2nd generation Korean Americans in Washington State. 100 Korean Immigration Celebration Conference, University of Washington; 2003. Unpublished manuscript. [Google Scholar]

- Jones SF, Kaderlan-Halsey A. Closing the gap: Research under way to address the needs of minority populations. Connections; News from the University of Washington School of Nursing. 2003;14(3):6–7. [Google Scholar]

- Kim E. Cultivating Korean American ethnicity through parenting. In: Kim H, editor. Korean American identities: A look forward. Seattle, WA: The Seattle-Washington State Korean American Association; 2005a. pp. 125–137. [Google Scholar]

- Kim E. Korean American parental control: Acceptance or rejection? ETHOS: Journal of the Society for Psychological Anthropology. 2005b;33:347–366. [Google Scholar]

- Kim E, Hong S. First generation Korean American parents' perceptions on discipline. Journal of Professional Nursing. doi: 10.1016/j.profnurs.2006.12.002. (in press) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim H, Do H, Park J. The ascendancy of second-generation Korean Americans: Socio-economic profiles of Korean American in Washington State. In: Kim H, editor. Korean American identities: A look forward. Seattle, Washington: The Seattle-Washington State Korean American Association; 2005. pp. 3–31. [Google Scholar]

- Kim SY, Ge X. Parenting practices and adolescent depressive symptoms in Chinese American families. Journal of Family Psychology. 2000;14(3):420–435. doi: 10.1037//0893-3200.14.3.420. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim U, Choi S. Individualism, collectivism, and child development: A Korean perspective. In: Greenfield PM, Cocking RR, editors. Cross-cultural roots of minority child development. Hilldale, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum; 1994. pp. 227–257. [Google Scholar]

- Lee B. Confucian ideals and American values. In: Kim IJ, editor. Korean-Americans: Past, present, and future. Elizabeth, NJ: Hollym; 2004. pp. 273–277. [Google Scholar]

- Lee RM, Choe J, Kim G, Ngo V. Construction of the Asian American Family Conflict Scale. Journal of Consulting Psychology. 2000;47(2):211–222. [Google Scholar]

- Maccoby E, Martin J. Socialization in the context of the family: Parent-child interaction. New York: John Wiley & Sons; 1983. [Google Scholar]

- Norusis MJ. SPSS 13.0 Advanced statistical procedures companion. Upper Saddle River, New Jersey: Prentice Hall; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Oak S, Martin V. American/Korean contrast: Patterns and expectations in the U.S. and Korea. Elizabeth, NJ: Hollym; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Radloff LS. The CES-D Scale: A self-report depression scale for research in the general population. Applied Psychological Measurement. 1977;1:385–401. [Google Scholar]

- Radloff LS. The use of the Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale in adolescents and young adults. Journal of Youth and Adolescence. 1991;20:149–166. doi: 10.1007/BF01537606. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rapee RM. Potential role of childrearing practices in the development of anxiety and depression. Clinical Psychology Review. 1997;17(1):47–67. doi: 10.1016/s0272-7358(96)00040-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rohner R. [Retrieved Feb 1, 2007];Glossary of significant concepts in Parental acceptance-rejection theory (PARTheory) 2007 from http://vm.uconn.edu/~rohner/

- Rohner R, Britner PA. World wide mental health correlates of parental acceptance-rejection: Review of cross-cultural and intracultural evidence. Family Focus, F5, F7. 2000 [Google Scholar]

- Rohner R, Khaleque A, Cournoyer DE. [Retrieved Feb 2, 2007];Parental acceptance-rejection theory, methods, evidence, and implications. 2007 from http://vm.uconn.edu/~rohner.

- Rohner R, Pettengill SM. Perceived parental rejection and parental control among Korean adolescents. Child Development. 1985;36:524–528. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saluja G, Iachan R, Scheidt P, Overpeck MD, Sun W, Giedd J. Prevalence of and risk factors for depressive symptoms among young adolescents. Archives in Pediatric and Adolescent Medicine. 2004;158:760–765. doi: 10.1001/archpedi.158.8.760. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sen B. Adolescent propensity for depressed mood and help seeking: Race and gender differences. Journal of Mental Health Policy. 2004;7(3):133–145. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sheeber L, Hops H, Alpert A, Davis B, Andrews J. Family support and conflict: Prospective relations to adolescent depression. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology. 1997;25(4):333–345. doi: 10.1023/a:1025768504415. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shin JK. Help-seeking behaviors by Korean immigrants for depression. Issues in Mental Health Nursing. 2002;23:461–476. doi: 10.1080/01612840290052640. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shin K, Shin C. The lived experience of Korean immigrant women acculturating into the United States. Health Care for Women International. 1999;20:603–617. doi: 10.1080/073993399245494. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shrake E. Korean American mothers' parenting styles and adolescent behavior. In: Moon A, Song Y, editors. Korean American women: From tradition to modern feminism. Westport, CT: Greenwood Press; 1996. pp. 175–192. [Google Scholar]

- Wong SL. Depression level in inner-city Asian American adolescents: The contribution of cultural orientation and interpersonal relationships. Journal of Human Behavior in the Social Environment. 2001;3:49–64. [Google Scholar]

- Yeh C. Age, acculturation, cultural adjustment, and mental health symptoms of Chinese, Korean, and Japanese immigrant youths. Cultural Diversity and Ethnic Minority Psychology. 2003;9(1):38–48. doi: 10.1037/1099-9809.9.1.34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yeh C, Inose M. Difficulties and coping strategies of Chinese, Japanese, and Korean immigrant students. Adolescence. 2002;37(145):69–82. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zahn-Waxler C, Duggal S, Gruber R. Parental psychopathology. In: Bornstein MH, editor. Handbook of parenting. Vol. 4. Mahwah, New Jersey: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates; 2002. pp. 295–327. [Google Scholar]

- Zuniga de Nuncio M, Nader P, Sawyer M, Guire Mea. A parental intervention study to improve timing of immunization initiation in Latino infants. Journal of Community Health. 2003;28:151–158. doi: 10.1023/a:1022651631448. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]