Abstract

Atomic-resolution information on the structure and dynamics of nucleic acids is essential for a better understanding of the mechanistic basis of many cellular processes. NMR spectroscopy is a powerful method for studying the structure and dynamics of nucleic acids; however, solution NMR studies are currently limited to relatively small nucleic acids at high concentrations. Thus, technological and methodological improvements that increase the experimental sensitivity and spectral resolution of NMR spectroscopy are required for studies of larger nucleic acids or protein-nucleic acid complexes. Here we introduce a series of imino-proton-detected NMR experiments that yield over a 2-fold increase in sensitivity compared to conventional pulse schemes. These methods can be applied to the detection of base pair interactions, RNA-ligand titration experiments, measurement of residual dipolar 15N-1H couplings, as well as direct measurements of conformational transitions. These NMR experiments employ longitudinal spin relaxation enhancement techniques that have proven useful in protein NMR spectroscopy. The performance of these new experiments is demonstrated for a 10 kDa TAR-TAR*GA RNA kissing complex and a 26 kDa tRNA.

Keywords: RNA, DNA, structure, dynamics, TROSY, SOFAST, hydrogen bond, longitudinal-relaxation enhancement, molecular kinetics

Introduction

Nucleic acids play key roles in many cellular processes. While the primary role of DNA is to store the organism’s genetic information, RNAs are involved in a variety of different cell functions, e. g. transfer of genetic information to the ribosomes (mRNA), translation (tRNA), catalytic ribosome activity (rRNA), and regulation of gene expression (RNAi). Similar to proteins, this functional versatility requires distinct three-dimensional structures. Multidimensional NMR spectroscopy is a well-established technique for the determination of high-resolution structures of RNAs in solution 1,2, where ~40% of the nucleic acid structures in the PDB have been solved by NMR spectroscopy. In addition, NMR spectroscopy provides unique atomic level information on local flexibility, domain motions, and anisotropic molecular tumbling. NMR is also well suited to studying interactions of RNAs with other nucleic acids, proteins, small ligands, solvent molecules, or metal ions. Furthermore, NMR spectroscopy allows real-time site-resolved studies of biologically relevant kinetic processes, such as structural rearrangements that are essential for RNA function 3.

The development of new and optimized NMR experiments has made it possible to study larger and more complex nucleic acid systems. For example, transverse-relaxation optimized NMR experiments were introduced for RNA about 10 years ago 4–7 to help reduce the sensitivity loss due to spin relaxation during the various frequency labeling and coherence transfer periods of an experiment. These developments resulted in significant improvements in spectral resolution and sensitivity, and extended the applicability of NMR spectroscopy to larger RNAs 8, 9. Recently, it has been demonstrated for proteins that NMR experiments can also be optimized by enhancing longitudinal relaxation during the time delay between scans, resulting in higher repetition rates, increased sensitivity, and shorter overall experimental times. Longitudinal 1H relaxation enhancement exploits the principle that the efficiency of 1H spin-lattice relaxation is increased if nearby 1H are not excited and therefore remain in their thermodynamic equilibrium state. This allows some of the energy put into the system to be transferred to the unexcited 1H via dipole-dipole interactions (nOe effect) or chemical exchange with solvent hydrogens. The recently introduced, longitudinal relaxation enhanced BEST-type experiments 10,11, achieve a reduction in effective longitudinal 1H relaxation times from a few seconds to a few hundred milliseconds. In HMQC-type experiments, the sensitivity of fast-pulsing experiments is further enhanced by adjusting the excitation flip angle to the so-called Ernst angle 12. Both effects, longitudinal-relaxation enhancement and Ernst-angle excitation, have been combined in the SOFAST experiment 13,14 that allows recording 2D 1H-15N (or 1H-13C) correlation spectra of proteins with high sensitivity in very short experimental time.

Here, simulations and experiments are used to investigate the potential of longitudinal-relaxation enhancement for improving NMR studies of RNA. As a first example, we focus on imino 1H based correlation experiments because they provide valuable information on the local structure and dynamics of nucleic acids. The imino 1H-15N correlation spectrum generally only contains one peak per base pair, and therefore often serves as a “fingerprint” for detecting the folding state of the RNA. We demonstrate that, despite the lower 1H density in RNA compared to proteins, large relaxation enhancement effects are observed in optimized SOFAST-HMQC and BEST-TROSY-type experiments. These methods yield over a 2-fold sensitivity increase compared to conventional experiments and allow recording of 2D correlation spectra within only a few seconds, which is a prerequisite for atom-resolved real-time NMR studies of RNA kinetics.

Materials and Methods

Sample preparation

The following RNA samples were used in this study: a 32-nucleotide 1:2 13C/15N-labelled HIV TAR-unlabelled TAR*GA kissing complex (0.4 mM TAR concentration), an unlabelled 1:1 TAR-TAR*GA complex (effective complex concentration of ~1 mM), and a 76-nucleotide 15N-labelled E. coli tRNAVal (sample concentration of 0.9 mM). Unlabeled TAR and TAR*GA molecules used for this study were synthesized on a solid phase. 13C/15N-labelled TAR and TAR*GA were prepared in vitro using T7 RNA polymerase (Silantes GmbH). RNA samples were dialyzed against 50 mM NaCl at pH 6.6 in a 0.01 mM EDTA, 10 mM sodium phosphate buffer containing 0.4 g.L−1 sodium azide. 15N-labeled native tRNAVal was overexpressed in E. coli (BL21(DE3)) from the pVALT7 plasmid in M9 minimal media containing 15NH4Cl as the sole nitrogen source and purified as previously described 15. After purification, tRNAVal samples were extensively dialyzed into NMR buffer (10 mM sodium phosphate, pH 6.8, 80 mM NaCl, 5 mM MgCl2, and 0.1 mM EDTA) by repeated centrifugation in Centricon YM-10 centrifugal filter devices (Millipore, Bedford, MA). All final NMR samples contained 10% D2O and 90% H2O.

NMR Spectroscopy

All experiments were performed on a Varian INOVA 800 MHz NMR system equipped with a cryogenically cooled triple-resonance probe, and pulsed z-field gradients. The sample temperature was set to 25°C for all experiments, except for the sensitivity curves shown in figure 2D that were performed at 10°C. The pulse sequences presented in figures 4 and 5 can be applied to natural abundance, 15N-only labeled, or doubly 13C/15N labeled RNA (or DNA). The details on the acquisition parameters are given in the figure captions. The NMRPipe software 16 was used for data processing. For 2D spectral processing, the time-domain data were typically multiplied by a cosine-squared apodization function, and zero-filled to final matrices of 1024 × 1024 real data points. All pulse sequences presented in this work are freely available from the authors upon e-mail request.

Figure 2.

(a) NMR pulse sequences used to probe the relaxation behavior of imino protons for different spin excitation conditions: non-selective excitation (open squares), water-flip-back excitation (filled squares), and imino-selective excitation (filled circles). In all cases, a watergate sequence 44 using an imino-selective 180° pulse with a REBURP shape was applied. Imino-selective excitation is achieved by a 90° PC9 pulse. 45 All imino 1H pulses are centered at 12.5 ppm, and covering a bandwidth of 4.0 ppm. For water flip-back, a sinc shape is used centered on the water frequency, and covering a bandwidth of ~1 ppm. The delay Δ was set to 1/(2JNH), and a 2-step phase cycle ϕÊ=Êϕ recÊ=Êx,−x was used, in order to detect only signals from 15N-labelled RNA. Secondary structures of the TAR- TAR*GA complex, and the tRNAVal are shown in panels (b) and (c), respectively. Experimental sensitivity curves as a function of scan time, Tscan, (sum of pulse sequence duration, acquisition time, and recovery delay), measured for (d) the TAR- TAR*GA complex at 10° C, (e) the TAR- TAR*GA complex at 25° C, and (f) tRNAVal at 25°C. Filled circles, filled squares, and open squares correspond to the results obtained from imino-selective, water-flip-back, and non-selective excitation schemes, respectively.

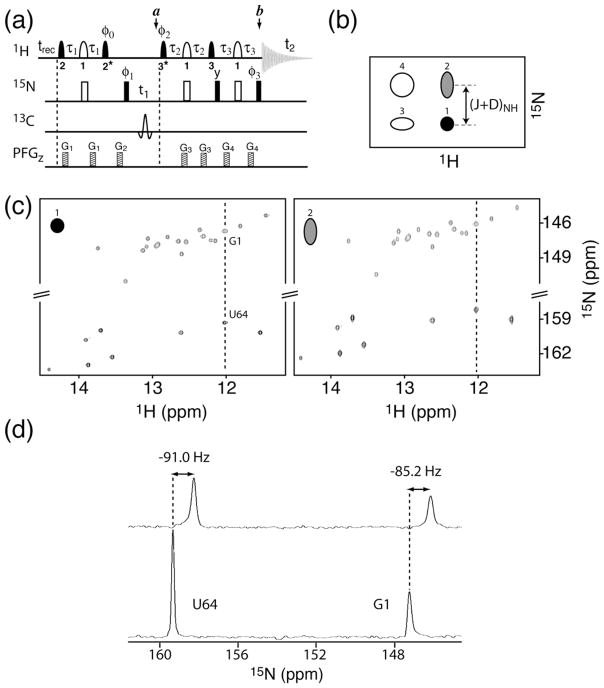

Figure 4.

(a) 2D 1H-15N BEST-TROSY pulse sequence. Filled and open symbols correspond to 90° and 180° rf pulses, respectively. The carrier frequencies are set to 12.5 ppm (1H), 150 ppm (13C), and 155 ppm (15N). 1H pulses cover a bandwidth of 4 ppm, and have the following shapes and durations (at 800 MHz): (1) REBURP 46, 1.5 ms (δ1), (2) PC9 45, 2.2 ms (δ2), and (3) EBURP-2 46, 1.4 ms (δ3). An asterisk indicates time and phase reversal of the corresponding pulse shape. For 13C and 15N labeled RNA samples a hyperbolic secant pulse covering a bandwidth of 200 ppm is used for 13C decoupling during t1 evolution. The transfer delays are adjusted to τ1 =1/(4JNH) −0.5δ1 −0.5δ2, τ2 = 1/(4JNH) −0.5δ1 −κδ3, and τ3 = 1/(4JNH) These settings account for spin evolution during the various shaped 1H pulses. The parameter κ ≈ 0.8 can be fine tuned to equilibrate the transfer amplitudes of the different coherence transfer pathways for optimal suppression of the unwanted quadruplet components in the spectrum. Pulses are applied along the x-axis unless indicated. The phase φ0 needs to be set to +y or −y, depending on the spectrometer, to add the signals originating from 1H and 15N polarization 4. Two repetitions of the experiment need to be recorded for echo/anti-echo-type quadrature detection in the 15N dimension using the following phase cycle for the TROSY component (peak 1): (I) φ1=−x,x, − y,y; φ2=y φ3=x; φacq= −x,x,y,−y; and (I) φ1=−x,x,− y,y; φ 2=−y φ3=−x; φacq=−x,x,−y,y. The semi-TROSY (peak 2) components of the peak quadruplet depicted in panel (b) can be selected using the same phase cycles, but adding 180° to phase φ2 for both quadrature components. (b) Schematic representation of the peak quadruplet observed in a 1H-15N correlation spectrum recorded without 15N decoupling in t1 and t2. (c) 2D BEST-TROSY (left) and BEST-semi-TROSY (right) spectra of tRNAVal recorded at 25°C and 800 MHz. The data were acquired using the pulse scheme shown in (a) with a recycle delay of 200 ms. A total of 200 complex points were acquired in the t1 dimension for a 15N spectral width of 30 ppm, resulting in acquisition times of 15 minutes per spectrum. (d) 1D traces extracted at the 1H chemical shift of residues G1 and U64 from the 2D spectra shown in (c), where the 1H-15N coupling constants extracted from the relative peak positions measured in the 2 spectra are shown.

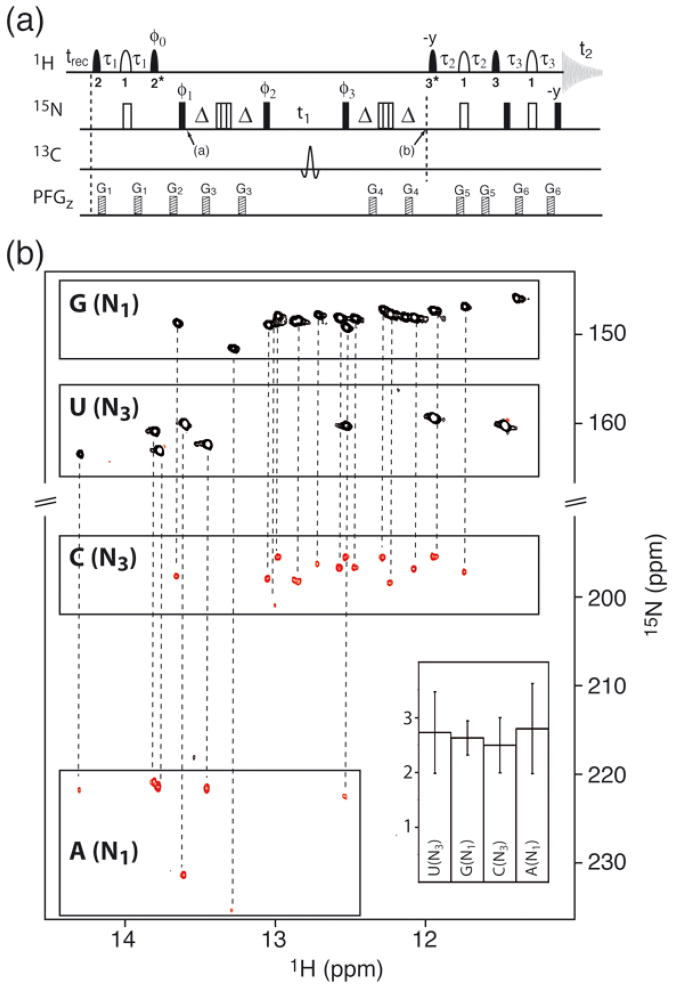

Figure 5.

BEST-HNN-COSY pulse sequence (a) for the detection of N-H···N hydrogen bonds in RNA. The same 1H pulse shapes, transfer delays τ1, τ2, and τ3, and carrier frequencies presented in figure 4 are used here, with the exception that the 15N carrier is switched from 155 ppm to 185 ppm between time points a and b. A trans-hydrogen-bond transfer delay 2Δ =Ê30 ms was used. A composite 59.4°x−298°−x−59.4°x pulse 47 is applied for 15N refocusing in the middle of each transfer period 2Δ. The following 4-step phase cycle is used: φ1=x,y,−x,−y; φ2=y,−x,−y,x; φ3=−y,x, y,−x;φacq=x,−y,−x,y. States-type quadrature detection in t1 is achieved by 90° phase incrementation of φ1 and φ2. (b) BEST-HNN-COSY spectrum of tRNAVal, acquired at 25°C and 800 MHz with a recycle delay of 200 ms. A total of 200 complex points were recorded in the t1 dimension for a 15N spectral width of 10000 Hz recorded in 20 min. For each hydrogen-bonded imino 1H, a pair of correlations is detected (dashed lines). A histogram shows the average sensitivity gain (and standard deviation) for individual peak groups obtained by comparing the BEST-HNN-COSY with the conventional HNN-COSY experiment of Dingley et al. 39, performed with a recycle delay of 1.5 s for optimal sensitivity.

Results and Discussion

Longitudinal spin relaxation of imino protons in RNA is governed by dipolar interactions with surrounding protons, and hydrogen exchange with water. Given the relatively low, and non-uniform, proton density in nucleic acids, it is not obvious that 1H-1H spin diffusion is efficient enough to yield fast energy dissipation within the 1H-1H spin network of the RNA. To address this question, we first performed numerical simulations for the Watson-Crick A-U and G-C base pairs. The predictions from these simulations were then validated by NMR experiments using two different sized RNAs.

Numerical simulations of longitudinal spin relaxation of imino protons in RNA

Figures 1a and 1b show imino 1H spin polarization recovery, and polarization uptake curves calculated for several different experimental conditions in Watson-Crick A-U and G-C base pairs. These curves were obtained by numerical integration of the Solomon equations describing the time dependence of spin polarization in a coupled 1H spin network, and included hydrogen exchange effects. All proton-proton distances for these calculations were obtained from the HIV TAR-TAR*GA kissing complex 17 (PDB accession number 2rn1). The spin polarization of individual protons was computed as a function of relaxation (recovery) time after a 90° excitation of only the imino 1H spins (selective excitation), or all 1H spins (non-selective excitation) in the RNA. The water proton polarization was assumed to be unaffected by the two excitation schemes.

Figure 1.

Numerical simulations of the longitudinal relaxation behavior of the imino proton spin system in A-U (left hand figures), and G-C (right hand figures) Watson-Crick base pairs using coordinates from the TAR-TAR*GA complex (PDB accession number 2rn1). The relaxation behavior was simulated by numerical integration of the Solomon equations for all protons of the TAR-TAR*GA complex, and by taking into account stochastic exchange processes between the labile 1H in the RNA and the water 1H that was assumed to remain in thermodynamic equilibrium throughout the calculation. For all simulations, an overall tumbling correlation time of τc = 8 ns was assumed, and internal dynamics were neglected. The 1H resonance frequency was set to 800 MHz. The simulations are representative of a single transient of a one-pulse NMR experiment. They do not take into account partial saturation of non-imino protons in a multi-scan experiment. (a) Chemical structure of A-U (left), and G-C (right) RNA base pairs. (b) Time evolution of the 1H polarization for the non-imino protons, illustrating the response of those protons after selective excitation of the imino protons. The color code used for these curves corresponds to the color of the proton sites in the chemical structures of the RNA base pairs. All water-exchange rate constants were set to zero for these calculations to better visualize the relative importance of individual non-imino protons for the energy uptake from the imino protons. (c) Recovery of imino proton polarization as a function of relaxation time after selective (solid lines) or non-selective (dashed lines) 1H excitation. Three calculations were performed in both cases assuming the following exchange rates with water hydrogens: τex = 0.5 s−1 for iminos, τex = 1.0 s−1 for hydroxyls (HO2’), and τex = 1.0 s−1, 5.0 s−1, and 10.0 s−1 for aminos. (d) Typical chemical shift ranges for different 1H types in RNA.

To evaluate the contributions of individual proton spins on longitudinal relaxation of the imino protons for a Watson-Crick base pair, we calculated polarization uptake curves (upper graphs of figures 1a and 1b). These calculations assumed selective imino 1H excitation and used exchange rates of imino and amino protons with the solvent of 0.5 and 0 s−1, respectively. For a G-C base pair the 4 amino protons account for more than 50% of the spin polarization uptake with a 200 ms recovery time. A similar result is obtained for an A-U base pair where, in addition to the adenine amino protons, the adenine H2 proton is important for polarization uptake. The imino proton polarization as a function of recovery delay is shown in the lower panels of figures 1a and 1b. To investigate the relative importance of hydrogen exchange effects and 1H-1H dipolar interactions, the hydrogen exchange rates of amino protons were also varied from 1 to 10 s−1 for these calculations 18. For non-selective 1H excitation, the polarization recovery of the imino protons strongly depends on the amino hydrogen exchange rates, while for selective excitation the imino 1H polarization recovery is fast, and essentially independent of the amino exchange rates for the tested values. These results predict that the dipolar interactions between imino and amino protons provide an efficient mechanism for energy dissipation for the imino proton spin whenever the amino proton spin polarization is close to equilibrium. These results also demonstrate that for stable base pairs (imino 1H exchange rates < 0.5 s−1 and amino 1H exchange rates < 10 s−1) hydrogen exchange does not represent the major relaxation pathway for imino protons. Overall, similar relaxation behavior is predicted for imino proton spins in G-C and A-U Watson-Crick base pairs.

Note that the simulations shown in figure 1 do not take into account partial saturation of protons after multiple repetitions of the NMR experiment. If longitudinal relaxation is not efficient enough for a proton to relax back to equilibrium during the inter-scan (recovery) delay, it will become increasingly saturated via 1H dipole-dipole interactions until reaching a steady state. This will slightly reduce the expected relaxation enhancement, notably for very fast repetition rates.

Longitudinal imino proton relaxation enhancement - Experimental results

To test the predictions of the simulations, longitudinal relaxation experiments were performed on two RNA samples: a 32-nucleotide 1:2 13C/15N-labelled TAR-unlabelled TAR*GA complex, and a 76-nucleotide 15N-labelled E. coli tRNAVal. The average longitudinal relaxation behavior of imino 1H in the TAR-TAR*GA complex and the tRNAVal was investigated by recording a series of 1D NMR spectra as a function of a relaxation (recovery) time after 1H excitation using one of the pulse schemes depicted in figure 2a. The three experimental schemes correspond to (i) non-selective excitation of all proton spins, (ii) a water-flip-back (wfb) scheme where all proton spins are excited except for water proton spins and proton spins resonating within the ~1 ppm bandwidth of the wfb pulse, and (iii) selective excitation of only the imino protons. The sensitivity curves of figures 2d-f show the intensity integrated over the imino region of the 1H spectra, normalized for equal experimental times, and plotted as a function of the scan time, Tscan, for TAR-TAR*GA (10° C), TAR-TAR*GA (25° C), and tRNAVal (25° C). In all 3 cases the maximum of the sensitivity curve is shifted towards shorter scan times when going from non-selective to water-flip-back to imino-selective excitation. This shift is accompanied by a significant sensitivity gain (~2-fold) when comparing optimized imino-selective and water-flip-back schemes. The sensitivity gain observed for selective imino excitation appears relatively independent of the size and structural fold of the RNA. Comparison of these experimental results with the numerical simulations shown in figure 1, indicates that the amino-solvent hydrogen exchange rates in these RNAs are well below 10 s−1 under the experimental conditions of the NMR studies. As expected, hydrogen exchange processes are accelerated at higher temperature resulting in a stronger relaxation-enhancement effect when using a water-flip-back scheme, due to higher hydrogen exchange rates for both the imino and amino 1H.

Thus, both the numerical simulations and the experiments indicate that longitudinal relaxation enhancement of imino protons in RNAs by selective excitation provides a promising new tool for dramatically reducing the time of an NMR experiment, while also increasing its intrinsic sensitivity. More generally, these results demonstrate that for Watson-Crick base pairs a small number (3 to 4) of unexcited closely spaced proton spins provide an efficient mechanism for fast energy dissipation, and thus accelerated longitudinal spin relaxation of imino proton spins. Given that only a small number of closely spaced proton spins dominate the relaxation behavior, similar results are expected for imino protons in Hoogsteen and other non-canonical base-pair interactions.

In the remaining of this article we will discuss the implementation of longitudinal imino 1H relaxation enhancement schemes in various types of 1H-15N correlation experiments.

Longitudinal-relaxation-enhanced 1H-15N correlation experiments

Two-dimensional 1H-15N correlation spectroscopy of imino groups is useful for rapid characterization of RNA secondary structure, where both the imino 1H and 15N chemical shifts and 1H -15N residual dipolar coupling constants yield valuable structural restraints. These experiments also provide a powerful tool for the detailed investigations of molecular interaction surfaces and binding affinities using NMR titrations, and chemical shift mapping. Finally, very rapid 1H-15N correlation spectroscopy experiments allow site-resolved studies of reaction kinetics by real-time 2D NMR. Therefore it is important to develop optimized 2D 1H-15N correlation experiments for RNAs. In the following sections we will discuss 2 experiments, SOFAST-HMQC and BEST –TROSY that present complementary features and advantages for the study of imino groups in RNA or DNA.

Imino SOFAST-HMQC

The SOFAST-HMQC experiment, which was recently developed for protein NMR spectroscopy 13,14, combines the advantages of longitudinal relaxation enhancement 19 and Ernst-angle excitation 12 and was applied here to studies of the imino protons in RNAs. Figure 3a shows the effect of flip angle and scan time on the SOFAST-HMQC experiment on tRNAVal at 25° C. A linear interpolation of the experimentally determined optimal (Ernst) flip angle as a function of the scan time is shown in the bottom panel. The relative sensitivity of SOFAST-HMQC using an optimized flip angle for each scan time is plotted in the center panel, and a sensitivity comparison with a conventional water-flip-back HMQC sequence is given in the top panel. Highest sensitivity is achieved when for a 200 ms scan time, and a flip angle of 130°. In this optimal sensitivity regime, SOFAST-HMQC yields a ~2.2 fold higher sensitivity compared to a conventional water-flip-back pulse scheme acquired with an optimized recycle delay of ~1 s. Some interesting applications of this optimized SOFAST-HMQC are 1H-15N imino spectra for low-concentration RNAs, or RNAs at natural abundance. Figure 3b shows a 12 hr SOFAST-HMQC spectrum on a 1 mM TAR-TAR*GA complex at natural 15N abundance (equivalent to a ~ 2 μM 15N-labelled sample). A similar spectrum using a conventional pulse scheme would require an acquisition time of ~2.5 days. Imino SOFAST HMQC therefore provides a powerful new method for the screening low-concentration 15N-labelled, or natural abundance, RNAs for probing structure, molecular interactions, or drug binding.

Figure 3.

(a) Experimental evaluation of the performance of the 1H-15N SOFAST-HMQC 13,14 optimized for imino groups in tRNAVal as a function of scan time. The lower curve shows a linear interpolation of the optimal 1H excitation flip angle for a given scan time as determined from a series of 1D SOFAST-HMQC spectra recorded with the flip angle varied from 90° to 150° (in 5° steps). The middle curve displays the SOFAST-HMQC intensity obtained using an optimized flip angle for each scan time. The upper curve shows the sensitivity gain observed for SOFAST-HMQC when compared to a standard water-flip-back HMQC experiment. (b) 2D SOFAST-HMQC spectrum of 1mM unlabeled (equivalent to 2 μM 15N-labelled) TAR- TAR*GA at 10°C recorded in 12 hrs. The recycle delay between scans has been set to 180 ms, and the flip angle to 120°, corresponding to the conditions yielding maximal sensitivity for this RNA. (c) 2D SOFAST-HMQC spectrum of 15N-labeled tRNAVal acquired in 3 s. A recycle delay of 1 ms, and a flip angle of 140° was used. Only 10 complex t1 points were recorded with a reduced 15N spectral width of 550 Hz, resulting in extensive spectral aliasing but no additional peak overlap. Low-power 15N decoupling using an adiabatic WURST40 sequence (γB1/2π ≈ 650Hz) was applied during an acquisition time of 40 ms to limit the radiofrequency load of the cryogenic probe.

Another interesting recent application of the imino SOFAST-HMQC experiment is the site-resolved real-time investigation of fast kinetic molecular processes, such as protein folding and amide hydrogen exchange 20,21. Many noncoding RNAs undergo conformational transitions while performing their diverse functions in living organisms 22,23. To monitor real-time kinetic processes by simultaneously following many different atomic level probes in the RNA, requires recording a single 2D spectrum with a few second acquisition time. Figure 3c shows the 1H-15N imino SOFAST-HMQC spectrum of tRNAVal, recorded in only 3 s. The high sensitivity of this SOFAST-HMQC yields a high-quality spectrum that contains all the observable 1H-15N imino correlation peaks. As shown in figure 3a (top panel) the sensitivity of SOFAST-HMQC in this fast-pulsing regime is about one order of magnitude higher than that obtained with a conventional pulse scheme. The aptamer and expression domains of many riboswitches are of similar size to tRNA (< 100 nucleotides) 22, and show conformational transitions in the seconds to minutes time scale under appropriately chosen experimental conditions 24,25. Thus this imino SOFAST-based real-time 2D NMR method could be used to study changes in hydrogen bonding during the conformational transitions in riboswitches.

Imino BEST-TROSY

Imino-optimized transverse-relaxation-optimized (TROSY) correlation experiments in nucleic acids provide increased spectral resolution compared to HSQC or HMQC-type experiments 26. Significant line narrowing is observed in both spectral dimensions at high magnetic field strength because of the large chemical shift anisotropy (CSA) of 1H and 15N in imino groups 27. This TROSY enhancement is expected to increase with the magnetic field strength up to a maximum that is well beyond the limit of currently available NMR magnets (≤ 22 T). In contrast to protein NMR, where TROSY experiments are preferably performed on highly deuterated samples to reduce the effects of 1H-1H dipolar interactions, deuteration of the non-exchangeable proton sites in nucleic acids is not a prerequisite to obtain significant TROSY effects for the imino protons. We have developed a new BEST-TROSY experiment that combines transverse- and longitudinal-relaxation optimization to achieve optimal sensitivity and spectral resolution. The pulse sequence of the 1H-15N BEST-TROSY experiment is depicted in figure 4a, and an application to tRNAVal is shown in figure 4c (left panel). The sensitivity gain achieved by BEST-TROSY compared to a conventional water-flip-back TROSY-type 1H-15N correlation experiment (data not shown) is very similar to the results reported in figures 2d-f for different single-excitation experiments, indicating that the additional band-selective 1H pulses required for the BEST-TROSY sequence do not induce a significant signal loss. The BEST-TROSY experiment also shows excellent performance with respect to unwanted peak suppression (see figure 4d),

TROSY-type experiments are ideally suited for the measurement of residual dipolar 1H-15N coupling constants in RNA. Residual dipolar couplings (RDC) provide particularly valuable information on both local and global structure of the RNA 9,17,28,29, as well as on dynamics arising from local flexibility or domain motions 30–32. A particular advantage of imino RDCs is that this information provides important long-range structural information for large, or elongated RNA molecules9. RDCs are most commonly measured by dissolving the RNA in an appropriate “alignment medium” such as filamentous phage 33 that leads to an anisotropic molecular environment and, as a consequence, measurable RDCs. 1H-15N coupling measurements in both isotropic and anisotropic solution conditions are generally required to separate the contributions of scalar and residual dipolar couplings. Alternatively, a weak magnetic-field induced alignment can be observed at high fields due to the molecular magnetic susceptibility anisotropy of the RNA34,35. This effect increases with the square of the magnetic field strength, and thus becomes more attractive with the availability of higher magnetic fields. Generally, measurements at several (at least 2) different magnetic field strengths are required to separate the scalar and dipolar couplings. Recently, it has been shown that the zero-field splitting (scalar coupling) can be conveniently inferred from the measured imino 1H chemical shift 36, allowing the extraction of RDC values from 1H-15N coupling measurements at a single magnetic field strength.

To accurately measure the 1H-15N coupling constants in RNA, a second BEST-semi-TROSY experiment is performed that selects the broader downfield component in the 15N dimension (peak 2 of the quadruplet in figure 4b). This is achieved by a simple change of the phase cycle in the pulse sequence in figure 4a. The coupling constant is then obtained from the difference in 15N chemical shifts measured in the TROSY and semi-TROSY spectra, respectively, as illustrated for tRNAVal in figures 4c-d. High quality TROSY and semi-TROSY spectra are obtained for this 76-nucleotide RNA in only 15 min acquisition time per spectrum using this BEST-type sensitivity-optimized pulse sequence.

We expect that the considerable sensitivity gain (more than a factor of 2) brought about by the new BEST-type TROSY sequences will further enhance the applicability of 1H-15N RDC measurements to RNA and RNA-protein complexes of increasing size and complexity, as well as for studies of low-concentrated RNA samples, thus providing valuable information on the structure and dynamics of such systems.

Application to trans-hydrogen-bond correlation experiments

The BEST-TROSY pulse scheme can also be implemented in HNN-COSY correlation experiments, 26,37 which represent powerful tools for resonance assignment and structure determination of nucleic acids. The HNN-COSY technique is used for the direct detection of H-N···N-type H-bonds as well as the quantification of the trans-hydrogen scalar coupling constants 2hJNN. The detection of an H-bond provides direct information on base-pairing partners and the 2hJNN coupling constant can be related to the geometry and dynamics of a particular H-bond 38. Therefore the HNN-COSY experiment has been established as a standard tool for structural investigations of 15N-labelled RNA and DNA. Because of transverse spin relaxation during the long 15N-15N transfer delays required for this experiment (typically 2-times 30 to 40 ms), the sensitivity drops quickly for slower tumbling molecules and can limit the application to larger molecules.

Here we present a BEST-HNN-COSY pulse sequence (figure 5a) that yields greatly improved sensitivity, and therefore will allow direct detection of H-bonds in larger nucleic acids and/or for molecules at lower concentrations. Figure 5b shows the 2D 1H-15N correlation spectrum on tRNAVal recorded in 20 minutes, where all the expected 1H-15N imino correlation peaks are observed. This spectrum shows an average sensitivity gain of ~2.7, compared to the conventional HNN-COSY experiment of Grzesiek and coworkers 39, independent of the base-pair type (G-C or A-U). This sensitivity gain is even larger than expected from the sensitivity curves plotted in figure 2f, most likely because the BEST-HNN-COSY does a better job of leaving the water 1H magnetization unperturbed. These results indicate that by using longer experimental times (1 day instead of 20 min), BEST-HNN-COSY could be used to obtain base pairing information on much larger nucleic acids than tRNA. Note that this experiment is equally useful for detection of H-N···N hydrogen bonds in Hoogsteen and reversed Hoogsteen base pairs 40,41, with similar sensitivity gains expected to those obtained for Watson-Crick base pairs. Furthermore, the sensitivity of HNCO-type experiments 42,43 used to probe H-N···CO-type hydrogen bonds in G:U or G:C Wobble and reverse Wobble base pairs could also be enhanced by the BEST-TROSY-type sequence.

Conclusions and perspectives

We have demonstrated by simulation and experiment that longitudinal-relaxation-enhancement techniques, which have proven so powerful in protein NMR spectroscopy, are equally useful for NMR studies of RNA and DNA. The longitudinal-relaxation-enhanced 1H-15N correlation experiments introduced here yield sensitivity gains of more than a factor of 2 compared to conventional pulse schemes. This level of sensitivity gain is similar to that obtained for aqueous samples when replacing the standard room-temperature probe of a high-field NMR spectrometer, e.g. 800 MHz, with an expensive cryogenic probe, or when increasing the magnetic field strength by ~60%, e.g. from 800 MHz to ~1.3 GHz. This comparison highlights the importance of pulse sequence optimization in parallel to ongoing improvements of the NMR instrumentation in order to overcome one of the major limitations of liquid-state NMR spectroscopy: experimental sensitivity. We have shown here that the exchangeable amino protons in nucleic acids provide very efficient longitudinal relaxation of the imino protons in a base pair. Therefore, for nucleic acids the advantages of longitudinal- and transverse relaxation-optimization can be combined in a single experiment yielding both high sensitivity and spectral resolution. This is in contrast to NMR studies on larger proteins, which normally require samples where most of the protons have been replaced by deuterons. A high level of deuteration, however, means that little benefit is derived from longitudinal-relaxation enhancement techniques. Here we have focused on imino groups in RNA, and developed new pulse schemes that should have a major impact on studies of RNA structure and dynamics. For example, we have shown that these methods could be readily applied to a variety of NMR characterizations of nucleic acids including: NMR titrations, chemical shift mappings, measurement of RDCs, and direct detection of H-bonds. Finally, the imino SOFAST-HMQC pulse sequence described here can also be used in real-time investigation of the formation and disruption of individual H-bonds and H-bond networks during conformational transitions in regulatory RNAs such as riboswitches or thermosensors. The applications are not limited to the specific sequences employed here, but many other NMR experiments used for the investigation of nucleic acids will likely equally benefit from these longitudinal-relaxation optimization techniques.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the Commissariat à l’Energie Atomique, the Centre National de la Recherche Scientifique, the University Grenoble1, the French research agency by a grant to B.B. (ANR JCJC05-0077), and National Institutes of Health grant AI33098 to A. P. We also thank Lea Witkowsky for preparation of the 15N-labeled tRNAVal.

References

- 1.Fürtig B, Richter C, Wöhnert J, Schwalbe H. Chembiochem. 2003;4:936–962. doi: 10.1002/cbic.200300700. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Zidek L, Stefl R, Sklenar V. Curr Opin Struct Biol. 2001;11:275–281. doi: 10.1016/s0959-440x(00)00218-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Fürtig B, Buck J, Manoharan V, Bermel W, Jaschke A, Wenter P, Pitsch S, Schwalbe H. Biopolymers. 2007;86:360–383. doi: 10.1002/bip.20761. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Brutscher B, Boisbouvier J, Pardi A, Marion D, Simorre JP. J Am Chem Soc. 1998;120:11845–11851. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Fiala R, Czernek J, Sklenar V. J Biomol NMR. 2000;16:291–302. doi: 10.1023/a:1008388400601. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Riek R, Pervushin K, Fernandez C, Kainosho M, Wüthrich K. J Am Chem Soc. 2001;123:658–664. doi: 10.1021/ja9938276. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Brutscher B, Simorre JP. J Biomol NMR. 2001;21:367–372. doi: 10.1023/a:1013398728535. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.D’Souza V, Summers MF. Nature. 2004;431:586–590. doi: 10.1038/nature02944. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lukavsky PJ, Kim I, Otto GA, Puglisi JD. Nat Struct Biol. 2003;10:1033–1038. doi: 10.1038/nsb1004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Schanda P, Van Melckebeke H, Brutscher B. J Am Chem Soc. 2006;128:9042–9043. doi: 10.1021/ja062025p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lescop E, Schanda P, Brutscher B. J Magn Reson. 2007;187:163–169. doi: 10.1016/j.jmr.2007.04.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ernst R, Bodenhausen G, Wokaun G. Principles of Nuclear Magnetic Resonance in One and Two Dimensions. Oxford University Press; Oxford: 1987. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Schanda P, Brutscher B. J Am Chem Soc. 2005;127:8014–8015. doi: 10.1021/ja051306e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Schanda P, Kupce E, Brutscher B. J Biomol NMR. 2005;33:199–211. doi: 10.1007/s10858-005-4425-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Vermeulen A. Determining Nucleic Acid Global Structure by Application of NMR Residual Dipolar Couplings. University of Boulder; Boulder, CO: 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Delaglio F, Grzesiek S, Vuister GW, Zhu G, Pfeifer J, Bax A. J Biomol NMR. 1995;6:277–293. doi: 10.1007/BF00197809. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Van Melckebeke H, Devany M, Di Primo C, Beaurain F, Toulme JJ, Bryce DL, Boisbouvier J. Proc Natl Acad Sci, USA. 2008;105:9210–9215. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0712121105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gueron M, Leroy JL. Studies of base pair kinetics by NMR measurement of proton exchange. Nuclear Magnetic Resonance and Nucleic Acids. 1995;261:383–413. doi: 10.1016/s0076-6879(95)61018-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Pervushin K, Vögeli B, Eletsky A. J Am Chem Soc. 2002;124:12898–12902. doi: 10.1021/ja027149q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Schanda P, Brutscher B, Konrat R, Tollinger M. J Mol Biol. 2008;380:726–741. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2008.05.040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Schanda P, Forge V, Brutscher B. Proc Natl Acad Sci, USA. 2007;104:11257–11262. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0702069104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Serganov A, Patel DJ. Nature Reviews Genetics. 2007;8:776–790. doi: 10.1038/nrg2172. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Al-Hashimi HM, Walter NG. Curr Opin Struct Biol. 2008;18:321–329. doi: 10.1016/j.sbi.2008.04.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Wickiser JK, Winkler WC, Breaker RR, Crothers DM. Mol Cell. 2005;18:49–60. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2005.02.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Greenleaf WJ, Frieda KL, Foster DAN, Woodside MT, Block SM. Science. 2008;319:630–633. doi: 10.1126/science.1151298. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Pervushin K, Ono A, Fernandez C, Szyperski T, Kainosho M, Wuthrich K. Proc Natl Acad Sci, USA. 1998;95:14147–14151. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.24.14147. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hu JZ, Facelli JC, Alderman DW, Pugmire RJ, Grant DM. J Am Chem Soc. 1998;120:9863–9869. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Mollova ET, Hansen MR, Pardi A. J Am Chem Soc. 2000;122:11561–11562. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Sibille N, Pardi A, Simorre JP, Blackledge M. J Am Chem Soc. 2001;123:12135–12146. doi: 10.1021/ja011646+. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Blackledge M. Prog Nucl Magn Reson Spectrosc. 2005;46:23–61. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Getz M, Sun XY, Casiano-Negroni A, Zhang Q, Al-Hashimi HM. Biopolymers. 2007;86:384–402. doi: 10.1002/bip.20765. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Bailor MH, Musselman C, Hansen AL, Gulati K, Patel DJ, Al-Hashimi HM. Nature Protocols. 2007;2:1536–1546. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2007.221. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Hansen MR, Mueller L, Pardi A. Nat Struct Biol. 1998;5:1065–1074. doi: 10.1038/4176. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Tolman JR, Flanagan JM, Kennedy MA, Prestegard JH. Proc Natl Acad Sci, USA. 1995;92:9279–9283. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.20.9279. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Tjandra N, Omichinski JG, Gronenborn AM, Clore GM, Bax A. Nat Struct Biol. 1997;4:732–738. doi: 10.1038/nsb0997-732. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Ying JF, Grishaev A, Latham MP, Pardi A, Bax A. J Biomol NMR. 2007;39:91–96. doi: 10.1007/s10858-007-9181-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Dingley AJ, Grzesiek S. J Am Chem Soc. 1998;120:8293–8297. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Grzesiek S, Cordier F, Jaravine V, Barfield M. Prog Nucl Magn Reson Spectrosc. 2004;45:275–300. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Dingley AJ, Nisius L, Cordier F, Grzesiek S. Nature Protocols. 2008;3:242–248. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2007.497. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Wöhnert J, Dingley AJ, Stoldt M, Gorlach M, Grzesiek S, Brown LR. Nucleic Acids Res. 1999;27:3104–3110. doi: 10.1093/nar/27.15.3104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Dingley AJ, Masse JE, Peterson RD, Barfield M, Feigon J, Grzesiek S. J Am Chem Soc. 1999;121:6019–6027. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Liu AZ, Majumdar A, Hu WD, Kettani A, Skripkin E, Patel DJ. J Am Chem Soc. 2000;122:3206–3210. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Dingley AJ, Masse JE, Feigon J, Grzesiek S. J Biomol NMR. 2000;16:279–289. doi: 10.1023/a:1008307115641. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Piotto M, Saudek V, Sklenar V. J Biomol NMR. 1992;2:661–665. doi: 10.1007/BF02192855. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Kupce E, Freeman R. J Magn Reson A. 1994;108:268–273. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Geen H, Freeman R. J Magn Reson. 1991;93:93–141. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Shaka AJ, Pines A. J Magn Reson. 1987;71:495–503. [Google Scholar]