Abstract

The development of implantable biosensors for continuous monitoring of metabolites is an area of sustained scientific and technological interest. On the other hand, nanotechnology, a discipline which deals with the properties of materials at the nanoscale, is developing as a potent tool to enhance the performance of these biosensors. This article reviews the current state of implantable biosensors, highlighting the synergy between nanotechnology and sensor performance. Emphasis is placed on the electrochemical method of detection in light of its widespread usage and substantial nanotechnology-based improvements in various aspects of electrochemical biosensor performance. Finally, issues regarding toxicity and biocompatibility of nanomaterials, along with future prospects for the application of nanotechnology in implantable biosensors, are discussed.

Keywords: implantable, biosensors, continuous monitoring, nanotechnology, biofouling, oxygen dependence, miniaturization

1. Introduction

Numerous clinical trials and intensive research efforts have indicated that continuous metabolic monitoring holds great potential to provide an early indication of various body disorders and diseases. In view of this, the development of biosensors for the measurement of metabolites has become an area of intense scientific and technological studies for various research groups across the world. These studies are driven by the need to replace existing diagnostic tools, such as glucose test strips, chromatography, mass spectroscopy and enzyme linked immunosorbent assays (ELISA), with faster and cost effective diagnostic devices that have the potential to provide an early signal of metabolic imbalances and assist in the prevention and cure of various disorders like diabetes and obesity.

1.1. Why Implantable Biosensors?

Miniaturized, implantable biosensors form an important class of biosensors in view of their ability to provide metabolite(s) level(s) continuously without the need for patient intervention and regardless of the patient’s physiological state (rest, sleep, exercise etc.). For example, implantable biosensors form a highly desirable proposition for diabetes management which at present rely on data obtained from test strips using blood drawn from finger pricking, a procedure that is not only painful but also is incapable of reflecting the overall direction, trends, and patterns associated with daily habits (Reach and Wilson 1992). This initiated wide research efforts focused on developing implantable biosensors for continuous monitoring of various biologically relevant metabolites (Wang 2001). Other classes of implantable devices that are intensively researched include sensors for nerve stimulation capable of alleviating acute pain (Schneider and Stieglitz 2004), sensors for detecting electric signals in brain (Hu and Wilson 1997a, b) and sensors for monitoring bio-analytes in brain (O'Neill 1994) together with implantable drug delivery systems for controlled delivery at the site of pain and stress (McAllister et al. 2000; Ryu et al. 2007).

The reliability of implantable systems is often undermined by factors like biofouling (Gifford et al. 2006; Wisniewski et al. 2001) and foreign body response (Wisniewski et al. 2000) in addition to sensor drifts and lack of temporal resolution (Kerner et al. 1993). In order to alleviate these issues, researchers have taken clues from the success of synergism between biosensors and nanotechnology that has led to highly reliable point of care diagnostic devices (Hahm and Lieber 2004) and biosensors for early detection of cancer. (Liu et al. 2004; Wang 2006; Yu et al. 2006b; Zheng et al. 2005) which is the subject of this review.

1.1 Scope of this Review

This review aims to survey the current status of implantable biosensors with particular emphasis on advances based on nanotechnology. Among all biosensors, the ones based on electrochemical detection have been widespread in view of their design and construction simplicity. With this in mind, we chose to include only electrochemical biosensors in this review. After a brief overview on nanotechnology, representative examples that use nanotechnology to improve various aspects of implantable biosensors are presented. The review concludes with an outlook of the challenges and future opportunities of nanotechnology based implantable biosensors.

2. Advances in Electrochemical Biosensors Based On Nanotechnology

2.1. Nanotechnology: Overview and Advantages

Nanotechnology is the understanding and control of matter at dimensions between approximately 1 and 100 nanometers, where unique phenomena enable novel applications (Kaehler 1994). As the size of a system decreases below 100 nm and in particular below 10 nm, a number of unusual physiochemical phenomena like enhanced plasticity (Koch et al. 1999), pronounced changes in thermal (Rieth et al. 2000) and optical properties (Polman and Atwater 2005), enhanced reactivity and catalytic activity (Bell 2003), faster electron/ion transport (Baetzold 1981; Kim et al. 2009), negative refractivity (Anantha Ramakrishna 2005) and novel quantum mechanical properties (Engheta et al. 2005; Loss 2009; Loss and DiVincenzo 1998) become pronounced. These properties have been demonstrated with a number of nanomaterials such as quantum dots and quantum rods, metal nanoparticles, magnetic nanoparticles, as well as nanowires and nanotubes. These unique properties of nanomaterials have also prompted many researchers to utilize them for the fabrication of implantable biosensors with enhanced performance in terms of miniaturization, biocompatibility, sensitivity and accuracy etc. which are discussed in subsequent sections.

2.1 Foreign Body Response

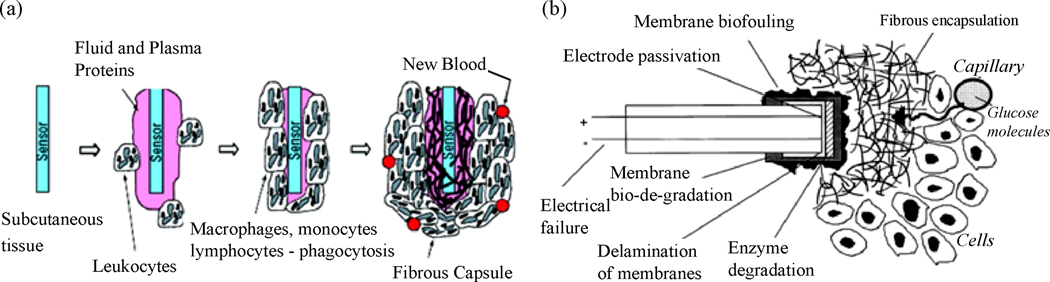

The success of any implantable device (biosensors, stents, and drug delivering devices) hinges on increasing their in vivo reliability and lifetime. The development of most implantable biosensors has been impeded since they are not capable of reliable in vivo monitoring for longer than a few hours to days (Gerritsen et al. 1999). Such bio-instability problem is considered to be a result of the in vivo environment since explanted sensors often function normally (Gifford et al. 2006). Typically, tissue inflammation and foreign body response sets in within short periods of time after sensor implantation (Onuki et al. 2008). While the former is caused by the tissue injury that results from implantation of the device as well as the continual presence of the device in the body, the latter is a result of the body’s natural response to fibrotically confine the implanted device and prevent it from interacting with the surrounding tissue (Figure 1a) (Bhardwaj et al. 2008; Onuki et al. 2008; Wisniewski and Reichert 2000). As a result of this, the implanted sensor becomes fouled with proteins and cells on the order of 10 to 100 microns in thickness within a short period of time following implantation. This cellular encapsulation forms a mass transfer barrier for analyte (glucose, lactate, etc.) diffusion to the sensing element, thereby degrading the in vivo sensor performance and long-term stability (Bhardwaj et al. 2008; Gerritsen et al. 1999; Gifford et al. 2006; Onuki et al. 2008; Wisniewski and Reichert 2000). For example, it was reported that biofouling-induced reduction in substrate (i.e. glucose) permeability could be as high as 50% for a glucose sensor, while the negative tissue reaction had a substantially higher (300 to 500%) greater impact on glucose transport reduction (Wisniewski et al. 2001). The deposition of active cells on the surface of implantable sensors can also cause a significant change in the local oxygen concentration, which also can lead to significant errors in the response of the implantable biosensor (Wu et al. 2007). In fact, for implantable biosensors the issue of foreign body response has been far more challenging than device-related issues such as electrical failure (Armour et al. 1990; Updike et al. 1994), electrode passivation (Hall et al. 1998), enzyme degradation (House et al. 2007; Updike et al. 1994), and component failure (Gilligan et al. 1994) (Figure 1b).

Figure 1.

(a) Sequence of events that are initiated around an implant leading to the formation of fibrous capsules around implantable systems (Frost and Meyerhoff 2006). (Reprinted with permission from American Chemical Society) (b) Various failure mechanisms reported for an implantable biosensor (Wisniewski and Reichert 2000). (Reprinted with permission from Elsevier)

An initial approach to enhance in vivo sensor functionality has been the use of biocompatible/anti fouling coatings (such as Nafion (Galeska et al. 2000; Galeska et al. 2002; Harrison et al. 1988; Moussy et al. 1993), hyaluronic acid (Praveen et al. 2003), humic acids (Galeska et al. 2001; Tipnis et al. 2007), phosphorylcholine (Yang et al. 2000), 2-methacryloyloxyethyl phosphorylcholine (Ishihara et al. 1994), polyurethanes with phospholipid polar groups (Ishihara et al. 1996), poly vinyl alcohol hydrogels (Onuki et al. 2008) etc.), that prevent biofouling and alleviate in part in vivo sensor degradation. These membranes are intended to: (i) maintain a desired, yet constant flux of passage of analyte molecules over long periods of time, (ii) reduce protein adsorption, and (iii) promote integration of the sensor with the surrounding tissues (Bhardwaj et al. 2008; Onuki et al. 2008). In addition, they should be thin yet porous enough in order to allow the sensor to rapidly respond to fluctuations in analyte concentration (Tipnis et al. 2007). However, even the use of biocompatible materials that have no toxic effect on the surrounding tissue is found to evoke a host of immune responses, associated with the action of implantation (Onuki et al. 2008). For this, a number of nanotechnology based approaches have been reported, which are discussed in this section. In the case of implantable biosensors, the plurality of semipermeable membranes that separate the s.c. tissue and the respective sensing element reduces analyte flux with associated decrease in sensitivity and increase in sensor’s response time (Tipnis et al. 2007; Vaddiraju et al. 2008).

While membrane composition defines biocompatibility, it has been suggested that a textured rather than a smooth sensor outer surface improves in vivo sensor performance by enhancing vascularity around the implant (Brauker et al. 1995; Sharkawy et al. 1997, 1998a, b). For example, incorporation of a textured ‘angiogenic layer’ onto the surface of implantable glucose sensor was shown to considerably improve its in vivo performance (Updike et al. 1997). While the exact mechanism beyond the enhancement is not clearly understood, it is widely believed that nanostructured membranes have a different contact angle and therefore a different degree of hydrophobicity or hydrophilicity from a regular smooth membrane which repels the adsorption of proteins onto the surface of the implant. A different school of thought has attributed the clotting process to a charge transfer theory, wherein the exchange of electrons between blood proteins and the implant surface is believed to initiate the release of fibrino peptides that cause thrombosis (Srinivasan and Sawyer 1970). Based on this, it is suggested that the time constant for electron exchange is less for nanostructured materials compared to thrombogenic metal-containing materials, thereby slowing down the clotting process. While the nature of the reported improvement from the use of nanostructured materials is still under debate, a number of implantable devices have started to employ such nanostructuring of their outer membrane surface to alleviate foreign body response (Ainslie et al. 2008). Some of the nanostructured surfaces include nanoporous titania (Popat et al. 2007; Sahlin et al. 2006), nanoporous silicon (Ainslie et al. 2008; Desai et al. 2000; Lopez et al. 2006; Striemer et al. 2007), nanoporous carbon (Narayan et al. 2008) etc. These nanostructured materials possessing high aspect ratio features, can alter cell phenotype, proliferation, and differentiation (Lopez et al. 2006; Saha et al. 2007). Methodologies to fabricate these nanostructured materials include ion-track etching, electrochemical corrosion, prolonged anodization, self assembly and a variety of other nanofabrication methods (Krishnan et al. 2008). In particular, nanofabrication allows management of shape and spacing in order to optimize drug release kinetics (Desai et al. 2004; Martin et al. 2005) and to enhance anti-fouling characteristics (Ainslie et al. 2005), besides precise control over the aspect ratio of the implantable device (Ainslie and Desai 2008). In order to achieve very thin and conformal nanostructured films (necessary for faster sensor response (Tipnis et al. 2007)) with precise control of pore size, atomic layer deposition (ALD) technique has also been used.(Adiga et al. 2008; Elam et al. 2003) ALD techniques employ alternating, self-limiting chemical reactions between gaseous precursor molecules that closely resemble an atomic layer-by-layer assembly process, thereby affording growth of ultrathin membrane structures (Xiong et al. 2005).

In an attempt to resemble the functionality of biological systems, researchers have also pursued nanoporous materials that change their permeability in response to environmental stimuli such as pH, temperature ionic/solute concentration, as well as magnetic and electric fields (Adiga et al. 2008). Most of these “smart” nanoporous membranes work on the basis of reversible expansion and collapse of responsive polymers incorporated within their pores. Such functionality can be used to impart fissures on the adsorbed protein(s) to re-establish efficient analyte transport. An extension to this approach has been the incorporation of magnetostrictive materials to induce local oscillating/vibration motions upon the application of external stimuli (Ainslie et al. 2005; Yeh et al. 2008). While these vibrations/oscillations are intended to cause protein desorption, the incorporation of such elements may prove costly and difficult, especially considering the miniaturization requirements of all implantable systems.

Polymer composite coatings where functional materials were embedded within polymeric matrices have also been reported to minimize the foreign body response (Yinghong and Chang Ming 2008). For example, proteases have been incorporated into a variety of different matrices to reduce the binding of proteins to surfaces by degrading adsorbed biomolecules (Kim et al. 2001; Mueller and Davis 1996). Recently nanocomposite coatings where nanomaterials are embedded within a polymer matrix are also being used to reduce biofouling (Asuri et al. 2007; Yinghong and Chang Ming 2008). Nanocomposite coatings based on carbon nanotubes (Asuri et al. 2007; Rege et al. 2003) and silica nanoparticles (Luckarift et al. 2006) have been used to reduce biofouling. While the exact mechanism of biofouling reduction is still under investigation, modulation in local hydrophobicity or hydrophilicity along with oxidative degradation might be at play (Yinghong and ChangMing 2008).

A recent approach to reduce inflammation and suppress fibrotic encapsulation involves the use of a variety of tissue response modifiers (TRMs). For this biodegradable microspheres containing TRMs are embedded within a biocompatible and anti-biofouling polymer (Bhardwaj et al. 2008; Onuki et al. 2008). The degradation of microspheres can be triggered either by a change in pH, ionic strength or electrical stimulus which cause a steady release of TRMs to the tissue surrounding the implant (Bhardwaj et al. 2008; Onuki et al. 2008). Poly (lactic-co-glycolic acid) (PLGA) is the commonly used materials for microspheres (Hickey et al. 2002a, b). Such microspheres have been loaded with various tissue response modifiers such as anti-inflammatory dexamethasone (Bhardwaj et al. 2007), growth factors (i.e. VEGF and PDGF (Norton et al. 2006; Patil et al. 2007)), vasodilator agents like NO (Frost et al. 2003; Frost and Meyerhoff 2004; Frost et al. 2002) and combinations thereof (Norton et al. 2006; Patil et al. 2007).

For implant coatings that are also capable of releasing TRMs, the release kinetics play an important role (Galeska et al. 2005). Fast releasing dexamethasone loaded PLGA microspheres embedded within a biocompatible matrix have been particularly useful in countering implantation induced inflammation as well as suppressing the time scale of release required to suppress inflammation and the foreign body response (Bhardwaj et al. 2007). Having said this, while dexamethasone is particularly suited to control the acute inflammatory response, once dexamethasone is exhausted from the microsphere composite, the body recognizes the implant as a foreign material and an immunogenic reaction is triggered that will eventually lead to fibrous encapsulation (Bhardwaj et al. 2007). Correspondingly this methodology is a mere suppression of acute phase of inflammation and has a finite time of efficacy so long as a continuous and sustained delivery of dexamethasone or other anti inflammatory agent(s) takes place at the vicinity of the implant. For this, zero-order release kinetics are sought to improve and prolong implant lifetime. In an attempt to achieve the much desired zero-order release profiles, variations in the size and molecular weight of the microspheres have been utilized (Onuki et al. 2008). A number of nanofabrication based techniques have also been employed to improve drug release kinetics (Desai et al. 2004; Martin et al. 2005). For example, (i) microfabricated asymmetric particles have been utilized to deliver drugs in a concentrated fashion at the device/intestinal interface (Tao and Desai 2005). Micromachining has also been employed to control the pore size of a silicon membrane and to afford zero order drug release kinetics (Desai et al. 1998; Desai et al. 1999). Similarly, systems incorporating titanium nanotubes with nano-orifices have been predicted to permit zero order kinetics (Ainslie and Desai 2008; Ainslie et al. 2008). Nano- and micro-fabrication can also be used to create single or multiple reservoirs of the drug or growth factors to be released. The release of such TRMs can be triggered using an external stimuli such as electric potential (Ainslie and Desai 2008).

A combination methodology wherein nanotextured surfaces that are also capable of drug delivery have been recently achieved using composite electrospun nanofibers as coatings for implantable devices (Abidian and Martin 2009; Hermanson et al. 2007; Kluge et al. 2008; Wang et al. 2008c). By controlling the voltage utilized during electrospinning, fibers with diameters in the nanometer size scale have been produced with precise control over the nanoscale topography (Abidian and Martin 2009; Hermanson et al. 2007; Kluge et al. 2008; Wang et al. 2008c). Moreover the porosity of these nanofiber coatings has been modulated to match that of the tissue or extracellular matrix (Sill and von Recum 2008). The high surface to volume ratio of electrospun fibers provides additional flexibility in enhancing drug loading and delivery as well as mass transfer properties (Abidian and Martin 2009; Hermanson et al. 2007; Kluge et al. 2008; Wang et al. 2008c).

Prior to concluding this section, it is worth mentioning that the extent of foreign body response (and in particular ischemia) is determined by the extent of tissue damage occurred during implantation (Kvist et al. 2006). This fact has led researchers to try hard in decreasing the implant size in order to minimize the foreign body response. For example, sensors similar in size to an acupuncture needle may considerably suppress foreign body response when compared to larger devices. In view of this, a review of nano- and micro- fabrication based miniaturization efforts are discussed in the subsequent sections.

2.2 Miniaturization

The prospects of implantable devices and in particular home-based metabolic monitoring can only be achieved if they can be readily implanted and explanted (for example, needle-assisted) without the need for complicated surgery. For this to be realized, the implantable device should be extremely small, which calls for unprecedented miniaturization of various functional components such as electrodes, power sources, signal processing units and sensory elements. Moreover, as mentioned above, miniaturized biosensors implanted through ultra fine needles (similar to the ones used in acupuncture) cause less tissue damage and therefore less inflammation and foreign body response (Kvist et al. 2006). As with all the criteria discussed in this review, nanotechnology has been a powerful force to achieve component miniaturization and integration down to the micrometer level, some of which are discussed in this section.

Miniaturization of implantable systems and in particular biosensors can be grouped under (i) miniaturization of sensing electrodes and elements and (ii) miniaturization of driving electronics for power, communication and their subsequent integration/packaging. With respect to the fabrication of miniaturized electrodes for analyte sensing, immobilization of enzymes onto an ultra-thin Pt wire (diameters less than 50 µm) or carbon nanofibers has been prominent (Crespi 1991; McMahon et al. 2005; Ward et al. 2004). The latter is well suited for fabricating nerve stimulating microelectrodes due to the possibility of ultra-fine dimensions and flexibility (Receveur et al. 2007). In order to further improve the electrocatalytic properties of carbon nanofibers, these were decorated with various metal nanoparticles without compromising their flexibility (Tamiya et al. 1993; Wu et al. 2006).

The nanoscale dimensions of single and multi-walled carbon nanotubes together with their electrocatalytic properties and high surface area has instigated researchers to utilize them as nanoelectrodes (Kim et al. 2007). For example, Lin et al.(Lin et al. 2004) have demonstrated a glucose biosensor based on aligned carbon nanotube nanoelectrode ensembles. Because of the loosely packed nature of the ensemble, each nanotube works as an individual nanoelectrode and the sufficiently larger (more than the nanotube diameter) space between nanotubes prevented diffusion layer overlap with the neighboring electrodes, rendering high signal-to-noise ratio and enhanced detection limits.

Top down micro-/nano-fabrication involving traditional semiconductor processes such as photolithography, dip-pen nanolithography and micromachining provide another facile avenue for sensor miniaturization. Kim et al (Errachid et al. 2001; Johnson et al. 1992) have reported a Si micromachined needle-shaped structure for glucose monitoring. These needle shaped biosensors along with channels for fluid flow are created by wet and dry etching processes, while the Ti/Pt working and Ag/AgCl reference electrodes located at the tip of the needle are patterned by photolithography. Even though these reports focused on glucose monitoring in situ, they can be easily extended to implantable systems and can be easily produced en masse.

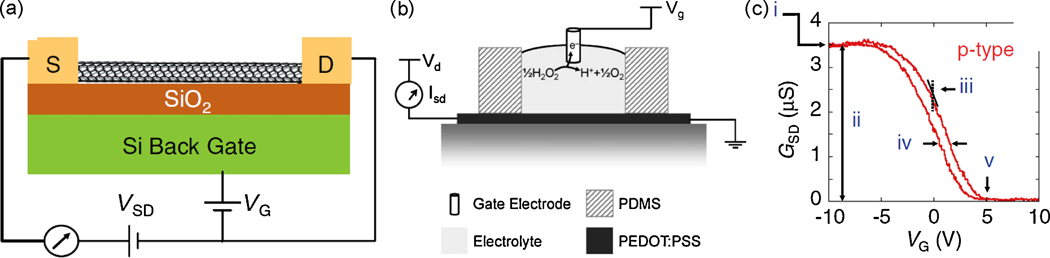

More recently, the advent of sub-micron lithography and its subsequent utilization to fabricate miniaturized transistors has instigated researchers to develop solid state electrochemical sensing devices in a transistor configuration (Figure 2a and 2b) (Bernards et al. 2008; Forzani et al. 2004). Biosensors based on traditional Si based transistors as well as the nascent organic thin film transistors are being developed for a range of analytes. The unique electrical properties of 1-D nanomaterials like carbon nanotubes (Allen et al. 2007; Besteman et al. 2003), nanorods (Kang et al. 2007; Wei et al. 2006), nanowires (Wang et al. 2008b) and semiconducting polymers (Forzani et al. 2004; Yoon et al. 2008) have led researchers to utilize them as channel materials and develop sensors based on changes induced in either gate conductance, modulation, transconduction, hysteresis or threshold voltage (Figure 2c). For example, glucose oxidase (GOx)-coated semiconducting single walled carbon nanotubes (SWNTs), are shown to be pH sensitive and their conductance alters upon addition of glucose substrate (Besteman et al. 2003). These nanojunction-based sensors whose size is only limited by the resolution of the lithography processes can revolutionize sensor miniaturization even though caution must be exerted to consider the fundamental aspects of electrochemistry that vary drastically in the nano scale regimes (Arrigan 2004)

Figure 2.

(a) Schematic representation of a nanotube field-effect transistor (NTFET) device (Allen et al. 2007); (b) Schematic of a typical organic electrochemical transistor along with a typical reaction of interest that is utilized at the gate electrode (Bernards et al. 2008); (c) Typical NTFET transfer characteristic (source–drain conductance vs gate voltage) that can be used to measure analyte concentrations. (i) Maximum conductance, (ii) modulation, (iii) transconductance, iv) hysteresis, and (v) threshold voltage (Allen et al. 2007). (Figures 2a and c are reprinted with permission from Wiley VCH from reference; Figure 2b is reprinted with permission from Royal Society of Chemistry)

With respect to miniaturization of driving electronics, the emerging field of nanofabrication together with the advent of sub-micron lithography techniques provides a powerful combination. As nanotechnology concepts continue to advance manufacturing in the semiconductor industry (Iwai 2009), so will the miniaturization of driving electronics of implantable sensors. For example, the use of inorganic nanowires and carbon nanotubes in transistor configurations (Avouris et al. 2007; Huang et al. 2007; Iwai 2009; Lu and Lieber 2007; Sharma and Ahuja 2008) together with advances in immersion lithography and maskless techniques will ultimately enable sensor miniaturization down to the micron level. Similarly, the use of nanowires for interconnects, nanocomposites for low dielectric materials and improvements in 3-D chip integration will help advance such miniaturized devices to a size that can be fitted within an acupuncture needle. This will be augmented by advances in power source components, which at the present time pose a major challenge to sensor development. Nanotechnology together with novel materials and fabrication methodologies are expected to provide advances in battery technologies and power generating circuits based on inductive coupling, variations in electromagnetic fields, electrostatic conversion of mechanical vibrations, and capacitance changes due to external vibrations etc (Mokwa and Schnakenberg 2001; Receveur et al. 2007). An easier approach could be the use of biofuel cells employing enzymatic reactions as power generating sources, though at present these have low power conversion efficiencies (Chen et al. 2001; Mano et al. 2002, 2003). The use of high surface area nanostructured anodes and cathodes together with nanomaterial-enhanced enzymatic catalysis could ultimately generate miniaturized biofuel cells with adequate power conversion efficiencies.

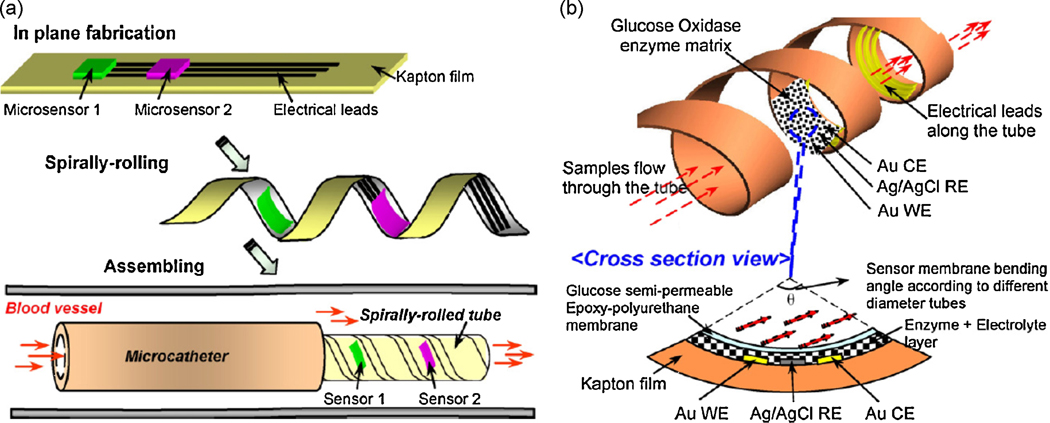

We conclude this section with a note on the use of polymeric materials for both electrode as well as electronic component miniaturization and for eventual replacement of traditional silicon based materials. The flexible nature of polymeric materials together with their low temperature processing and demonstrated biocompatibility with enzymes renders them advantageous over traditional Si- and glass-based materials. Moreover the soft and flexible nature of polymers could minimize the chance of tissue damage to the body during implantation and can be advantageous for applications where the device has to be able to adapt itself to the shape of the human anatomy. The work of Li et al. (Li et al. 2007), where sensing electrodes are patterned on a polymeric Kapton film and subsequently rolled up to form a two dimensional cylindrical electrode, presents a possible step forward. As schematically shown in Figure 3, such polymer based biosensors can be rolled to a point where they could potentially be fitted within a blood vessel as appropriate. In view of the well known corrosion resistance and antifouling nature of some polymeric substrates such as polyimides (Receveur et al. 2007; Sachs et al. 2005), this approach in combination with conventional printing techniques (such as screen/inkjet printing) has the potential for roll-to-roll large scale production of implantable devices. Plastic-compatible, low resistance, printable, gold nanoparticle-based formulations are already being used to form interconnects in functional electronic devices (Huang et al. 2003; Redinger et al. 2004). Similarly, reports on screen/inkjet printing based fabrication of various functional electronic components such as capacitors (Liu et al. 2003), photodiodes (Wojciechowski et al. 2009), RC filters (Chen et al. 2003) etc., have already started to emerge. Finally, emerging polymeric nanocomposites based on various nanomaterials can be used to alter the surface charge, hydrophilicity and tensile strength of these devices in order to ultimately enhance their antifouling properties.

Figure 3.

(a) Illustration of the proof-of-concept BioMEMS sensors based on polymeric substrates rolled up to form a catheter, wherein the sensing element is located on the inner walls of the rolled-up catheter. (b) Structure and working principle of glucose sensor showing the three electrodes and bent active region (Li et al. 2007). (Reprinted with permission from Elsevier)

2.3. Oxygen dependence

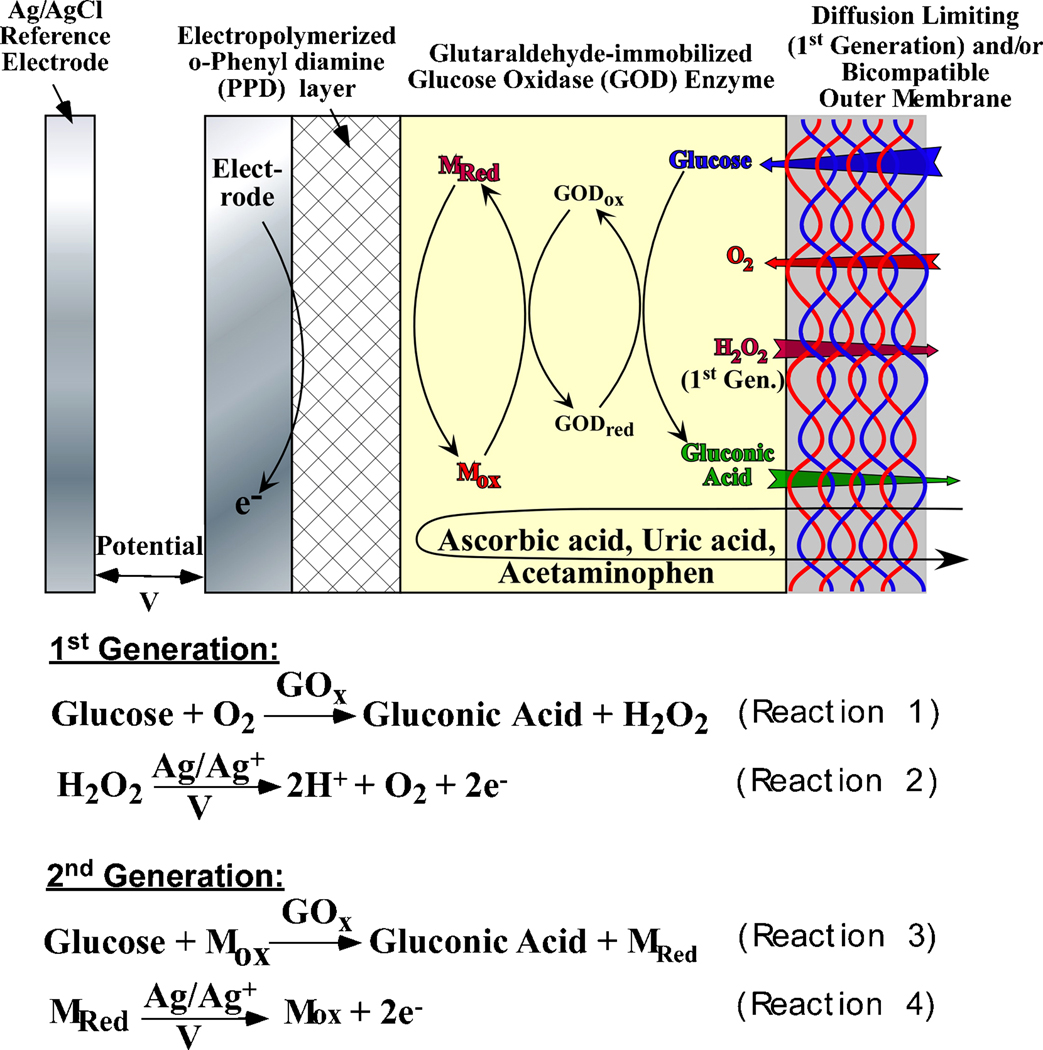

A large fraction of biosensing technologies rely on oxidase enzymes as a biorecognition element that catalyzes analyte oxidation to form hydrogen peroxide as shown specifically for GOx-driven glucose oxidation in Reaction 1 in Figure 4 (Wilson and Gifford 2005). In the case of electrochemical biosensors, the as generated hydrogen peroxide is amperometrically detected at the working electrode (Reaction 2 in Figure 4). Owing to the fact that oxygen is the cofactor for most oxidase enzymes, the response of such sensing element is subject to changes from variations in the local oxygen concentration (McMahon et al. 2005; McMahon and O'Neill 2005; Vaddiraju et al. 2008). This turns out to be a major concern for implantable biosensors since the amount of dissolved oxygen in the body can be considerably lower than the concentration of typically monitored analytes (i.e. glucose and to a lesser extent lactate). Such an oxygen imbalance can lead to a severe stoichiometric limitation of the enzymatic reaction 1 in Figure 4. The situation can be more acute upon implantation due to factors such as anesthesia which generally lower oxygen levels (Fischer et al. 1989), inflammatory host response reactions that lead to local consumption of oxygen by inflammatory cells at the vicinity of the biosensor (Lowry and Fillenz 2001) as well as physical conditions such as exercise which also lower the oxygen concentration in subcutaneous tissue (Wu et al. 2007). Such oxygen limitation leads to a saturation in sensor response at higher analyte concentrations (quantified as loss of sensor linearity) and hence, compromises the clinical accuracy necessary for proper therapeutic decisions.

Figure 4.

Schematic cross section of the first generation and second generation oxidase- based glucose biosensors, along with relevant reactions needed to afford electrochemical detection.

In order to decrease oxygen dependence a number of approaches have been employed. These can be classified into three generations of biosensors. First generation biosensors (Figure 4) typically utilize outer membranes that significantly decrease the analyte flux while impeding the oxygen influx to a lesser extent (Vaddiraju et al. 2008; Yu et al. 2006a). This approach is in accordance with the need to equip implantable devices with outer membranes that are necessary for decreasing in vivo biofouling and foreign body response. Flux limiting membranes typically employ the size and the hydrophobicity differences between analyte (e.g. glucose) and oxygen. Increasing the hydrophobicity improves O2 storage while at the same time impedes analyte passage due to the latter’s hydrophilic nature. A number of flux limiting membranes have been employed over the years such as Nafion® (Galeska et al. 2000; Moussy et al. 1993), polyurethane (Ishihara et al. 1996; Yu et al. 2006a), cellulose acetate (Kyrolainen et al. 1995) and layer-by-layer (LBL) assembled polyelectrolytes and/or multivalent cations (Tipnis et al. 2007; Vaddiraju et al. 2008) as well as other polymeric membranes (Harrison et al. 1988; Ishihara et al. 1996; Praveen et al. 2003; Wu et al. 2007; Yang et al. 2000). The presence of these flux limiting membranes together with anti-fouling membranes contributes to decreased sensor sensitivity and increased response time (Tipnis et al. 2007). Moreover, these membranes are prone to degradation for a number of reasons including oxidative degradation, calcification, delamination etc. In order to alleviate these issues and improve sensor performance, two strategies have been employed: (i) replace oxygen with synthetic mediators (2nd generation biosensors) and (ii) directly link the redox center of the enzyme with nano-sized electrodes (3rd generation biosensors).

Second generation biosensors (Figure 4) have attempted to decrease oxygen dependence by employing redox mediators that compete with oxygen in catalyzing the enzymatic reaction (Equations 3 and 4 in Figure 4). Various redox mediators have been reported (Atrash and O'Neill 1995; Cass et al. 1984; Chen et al. 1995; Kosela et al. 2002; Kulys et al. 1995; Lei et al. 1996; Scheller et al. 1991) but most of these sensors have not been tested in vivo owing to the toxicity of the mediators and their potential to leach out of the sensors. In addition, the oxidation of the reduced enzyme by oxygen can occur even in the presence of the mediator, which can lead to erroneous signal levels. To overcome some of these drawbacks, covalent coupling of mediators to flexible hydrogel polymers have been utilized (Calvo et al. 1996; Foulds and Lowe 1988; Gregg and Heller 1990, 1991; Ohara et al. 1993). This is a promising approach particularly in the case of conducting polymers that act as polymeric mediators (Gajovic et al. 1999; Hale et al. 1989; Kaku et al. 1994; Palys et al. 2007; Yu et al. 2003b). The ability of conducting polymers to intimately associate with enzymes without loss of activity provides an electrical pathway between the enzyme and the electrode that can lead to higher output currents and faster responses (Gajovic et al. 1999; Hale et al. 1989; Kaku et al. 1994; Palys et al. 2007; Yu et al. 2003b).

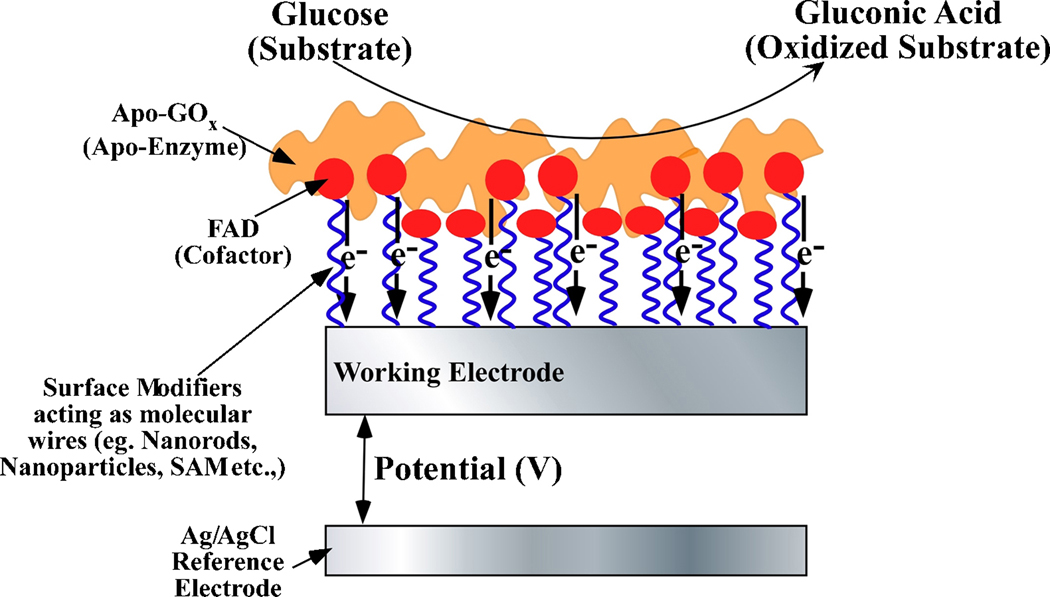

Owing to the similar size of nanomaterials and redox enzymes as an extension to second generation biosensors, various nanomaterials have been used to directly wire the redox center of enzymes to the electrode surfaces (Gilardi and Fantuzzi 2001). This can in part mitigate the oxygen dependence and render nanotechnology as a formidable contender for the development of advanced biosensing concepts. Figure 5 illustrates a typical configuration of a third generation biosensor. As can be seen from Figure 5, in the third generation biosensor the redox cofactor of the enzyme is covalently (or electrostatically) bound to the working electrode. This facilitates the re-reduction (or re-oxidation) of the enzymes after they have interacted with their substrates and assists in carrying electrons or holes to or from the working electrode. Various configurations of biosensors, wherein nanomaterials such as gold nanoparticles, carbon nanotubes, and magnetic nanoparticles serve as electrical connectors between the electrode and the enzyme redox center have been reported (Chen et al. 2007; Ferri et al. 1998; Hrapovic et al. 2004; Jia et al. 2002; Koopal et al. 1992; Kumar and Chen 2007; Li et al. 2006; Liu et al. 2007a; Liu et al. 2005; Xu and Han 2004; Yu et al. 2003a; Yu et al. 2005b; Yu et al. 2003b; Zhang et al. 2007). Extensive studies are being carried out to develop novel electrode surface functionalities, new electrode materials and new proteins that allow direct electron transfer between enzymes and electrodes (Bowden et al. 1984; Chattopadhyay and Mazumdar 2001; Fan et al. 2000; Gorton et al. 1999; Hamachi et al. 1994; House et al. 2007; Katz and Willner 2004; Stoica et al. 2006; Wang et al. 2004; Zayats et al. 2005; Zhang and Li 2004). However, it is worth mentioning that only a few of these reports were able to show no interferences from oxygen (Albery et al. 1985; Baravik et al. 2009; Khan et al. 1996; Palmisano et al. 2002) and in most cases the proof of such mediatorless, oxygen-independent analyte detection remains challenging (Ghindilis et al. 1997). In a combinatorial approach of second and third generation biosensors, Joshi et al (Joshi et al. 2005) have incorporated SWNTs within the redox hydrogels to further enhance sensor performance. The enhancement in sensor performance was based on the fact that the enzyme becomes partially unfolded when incubated with nanotubes, which allows for improved access to the FAD centers by the osmium redox centers. In addition, a reduction in the electron-transfer distance due to partial unfolding of glucose oxidase as it adsorbs onto the nanotube and penetration of nanotube closer to the FAD center is also possible.

Figure 5.

Schematic cross section of a third generation of biosensors specifically shown for glucose oxidase-based glucose detection.

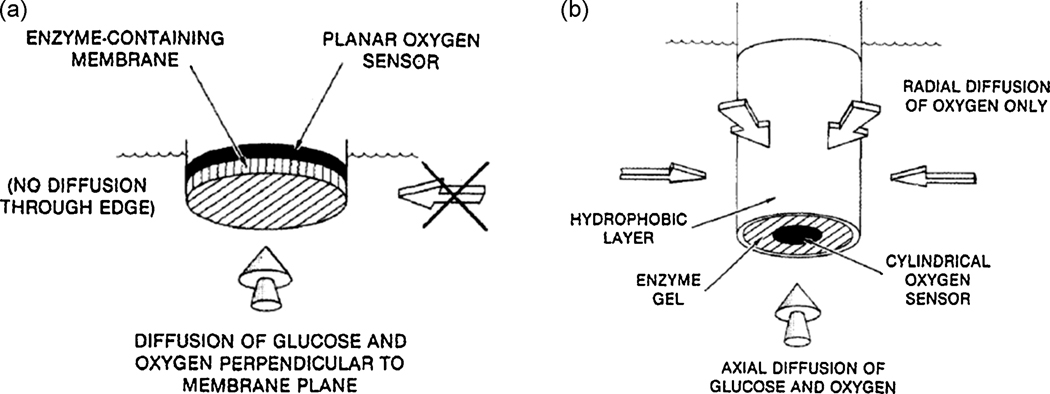

It is worth mentioning here that none of these second and third generation implantable biosensors have been tested in vivo. This is probably due to lack of comprehensive knowledge on their toxicity (Fiorito et al. 2006). Moreover, the necessity of outer membranes to avoid biofouling on these implantable sensors makes the use of first generation biosensors desirable for in vivo application. To this end, nanotechnology has been used to improve oxygen independence of first generation implantable biosensors. For example, nanotechnology can be used to improve the 2-dimensional cylindrical sensor developed by Gough’s group (Gough et al. 1985). As shown in Figure 6, these researchers have employed a 2 dimensional cylindrical working electrode with one open end. Owing to the hydrophobic nature of the cylindrical coating, oxygen diffusion is facilitated from all directions, whereas glucose diffuses only from one direction (that is the open end of the cylinder) (Gough et al. 1985). While a cylindrical shaped sensor could be difficult to miniaturize, nanofabrication techniques can be used to create high aspect ratio electrodes within a Si based working electrode wherein the oxygen path length is considerably reduced compared to the analyte path length, rendering the sensor oxygen independent. Similarly, the work of Li et al. (Li et al. 2007) discussed above (Figure 3), utilizing a polymeric Kapton film to roll up a 2 dimensional cylindrical electrode could be a promising approach. Another approach utilizing metal nanoparticle dispersed carbon paste electrode (Liu and Wang 2001) is also promising in view of its simplicity and the reports on non-toxicity of gold nanoparticles (Connor et al. 2005).

Figure 6.

Schematic cross section of (a) a typical one dimensional sensor where glucose and oxygen both diffuse in the same direction, mainly perpendicular to the plane of the electrode and (b) a two dimensional sensor, where glucose and oxygen diffuse axially into the enzyme gel but only oxygen can diffuse radially into the gel through the hydrophobic membrane (Gough et al. 1985). (Reproduced with permission from American Chemical Society)

2.4. Sensitivity and Selectivity

The term sensitivity of a biosensor refers to the magnitude of its response, while selectivity addresses its ability to respond only to changes of the intended analyte within the pool of numerous metabolites present in the body. Both sensitivity and selectivity are important criteria for an implantable biosensor. These two parameters can be considered interrelated based on fact that methodologies to improve sensitivity of a sensor usually degrade the selectivity. In addition, membrane-based improvements in selectivity typically interfere with the sensitivity of the sensors and in most cases decrease it. Methodologies to improve selectivity and sensitivity of an implantable biosensor, in particular based on nanotechnology are discussed in this section.

The sensitivity of implantable biosensor is dependent on: (i) physical design, (ii) activity of the enzyme, (iii) surface activity of the working electrode, (iv) inner polymer membranes (covering the surface of the working electrode) that are used to either immobilize enzymes or eliminate interferences (McMahon et al. 2005), and (v) the presence of an outer membrane required to alleviate oxygen dependence and/or to prevent biofouling (Vaddiraju et al. 2008; Yu et al. 2006a).

The nature of the working electrode as well as its surface activity plays an important role in defining sensor sensitivity for enzymatic sensors. Sensors based on Pt working electrodes were shown to exhibit the highest sensitivity for the oxidation of H2O2 among the typical inert electrode materials such as glassy carbon, palladium, gold and Pt. Based on this, platinization of working electrodes to impart nano scale roughness and thereby enhanced surface area and electrocatalytic activity has been a well known route to obtain significant gains in sensitivity (De Corcuera et al. 2005). Growth conditions during the platinization process have been modulated to yield various nanoscale morphologies like particles or networks as well as to vary their growth densities (De Corcuera et al. 2005; Kim and Oh 1996). Other strategies to enhance the surface activity of these working electrodes include modification of the working electrode with nanoparticles of Pt (Somasundrum et al. 1996), Ag (Welch et al. 2005), Ru (Kohma et al. 2007), Rd (Kotzian et al. 2006; Yang et al. 1998), Ir (Irhayem et al. 2002), Pd (Sakslund et al. 1996), and Au (Bharathi and Nogami 2001). Similarly, surface modification of working electrodes with nanostructured carbon (i.e. single- and multi-walled carbon nanotubes) have also been reported (Gooding 2005; Liu et al. 2007b; Luque et al. 2006; Sherigara et al. 2003; Tang et al. 2004; Wang 2005; Yang et al. 2006a; Yang et al. 2006b; Yu et al. 2003a). While the primary goal was to increase the surface area of the working electrode, research has proven that these nanostructured materials also impart substantial enhancements in electro-catalytic activity due to a large number of quinoid moieties at the tips of these nanotubes (Kim et al. 2007).

More recently, capitalizing on the nanoscale dimensions of carbon nanotubes, researchers have started to utilize them as nanoelectrodes as well as ensemble nanoelectrodes (Lin et al. 2004; Yu et al. 2003a). Numerous optimization studies on the density of the nanoelectrode ensemble have been performed so that the distance between two nanoelectrodes is larger than the diameter of each nanotube in the bundle, in order to minimize or eliminate overlap of the diffusion layer (Guiseppi-Elie et al.; Rahman and Guiseppi-Elie 2009). In this way each nanotube or nanotube bundle works as an individual nanoelectrode rendering them highly sensitive with enhanced detection limits.

One of the major concerns with electrochemical biosensors is surface poisoning of the working electrodes with the products of the electrochemical reaction which can lead to the eventual loss of sensor sensitivity. This necessitates frequent electrochemical cleaning of the working electrode which involves the application of higher potentials to desorb the electrochemical reaction products, which in turn can degrade sensor selectivity. Similarly, the electro-catalytic reduction of some analytes such as oxygen is impaired by its weak tendency to adsorb and segregate on the working electrode (Hahn 1998). Such poor kinetics also necessitated the use of higher working potentials to improve sensitivity. Surface modification of the working electrodes with platinum and gold nanoparticles (Li et al. 1998; Somasundrum et al. 1996), SWNTs (Gooding 2005; Liu et al. 2007b; Sherigara et al. 2003; Tang et al. 2004; Wang 2005; Yu et al. 2003a), multi-walled carbon nanotubes (MWNTs) (Dai and Shiu 2004; Qu et al. 2004; Salimi et al. 2007) and combinations thereof (Luque et al. 2006; Male et al. 2007; Wang and Zhang 2001) has been shown to alleviate both these issues and thus improve sensitivity at low operating potentials.

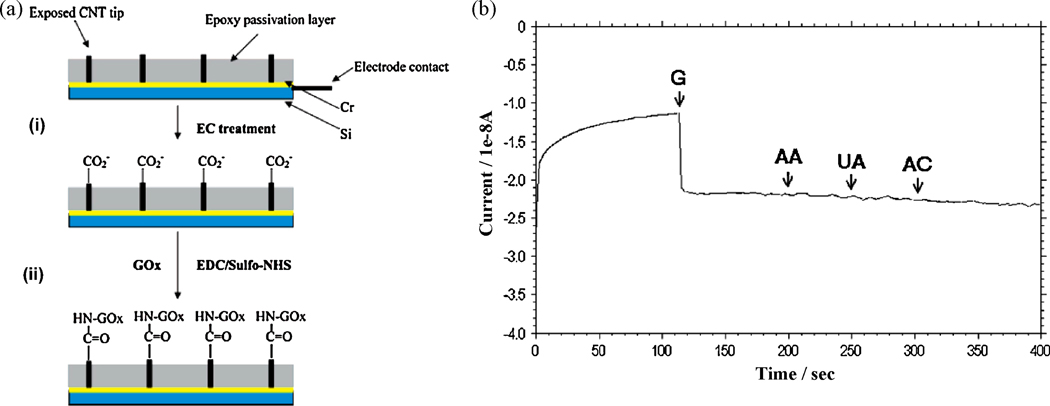

The issue of low sensor selectivity arises from the fact that the high potential (i.e. 0.6–0.7 V vs. Ag/AgCl reference electrode) required for electrochemical oxidation of enzymatically generated H2O2 in most implantable biosensors also promotes the oxidation of many endogenous species (such as ascorbic acid (AA), uric acid (UA), acetaminophen (AP), dopamine, and NO, etc.) rendering the sensor response erroneous. The use of perm-selective membranes (i.e., Nafion, polyester sulfonic acid, and cellulose acetate) on top of the working electrodes comes at the expense of sensitivity and response time. With this in mind, considerable research effort has been expended to reduce the operating potential of first generation implantable biosensors. Working electrode modification with nanostructured materials such as SWNTs and MWNTs discussed above, have also improved the selectivity of the sensors by specifically lowering the overpotential for electrochemical oxidation of H2O2 (Dai and Shiu 2004; Gooding 2005; Liu et al. 2007b; Qu et al. 2004; Salimi et al. 2007; Tang et al. 2004; Wang 2005; Yang et al. 2006a).

The use of carbon nanotubes (CNT) modified working electrodes has also facilitated the cathodic reduction of H2O2 in negative potential regimes (equation 5) which can avoid interferences from anodically (i.e. in positive voltage regimes) oxidizing species (Li et al. 1998; Lin et al. 2004; Salimi et al. 2007).

| (5) |

For example, Figure 7 illustrates the response of a SWNT-incorporated glucose sensor to sequential additions of glucose, AA, UA and AC when operated at −0.2 V (corresponding to the reduction of H2O2 produced by GOx as shown in equations 6–7).

| (6) |

| (7) |

Figure 7.

(a) Various steps in the fabrication of a glucose biosensor based on carbon nanotube nanoelectrode ensembles: (i) Electrochemical treatment of the carbon nanotube NEEs for functionalization (ii) Coupling of the glucose oxidase (GOx) enzyme to the functionalized carbon nanotube NEEs. (b) Response of the carbon nanotube based glucose biosensors to 5 mM addition of glucose (G), followed by 0.5 mM additions of each of: ascorbic acid (AA), uric acid (UA) and acetaminophen (AC) operating at −0.2 V vs Ag/AgCl reference electrode (Lin et al. 2004). (Reprinted with permission from American Chemical Society.)

where FAD is the oxidized form of the prosthetic group, flavin adenine dinucleotide. The sensor showed adequate sensitivity towards glucose additions while remaining insensitive to AA, UA and AC (Lin et al. 2004). However, further investigation is needed to address the role of electrochemical reduction of O2 (equations (8) and (9) below) during the operation of sensors at negative voltages which can also contribute to the signal.

| (8) |

| (9) |

Preliminary results in our laboratory have confirmed that the potential for the reduction of O2 and H2O2 on CNT modified electrodes do overlap with each other (unpublished work).

2.5. Enzyme Immobilization and Long Term Stability

Enzyme immobilization forms another important parameter of implantable biosensors in view of the fact that it dictates the sensitivity, selectivity and long term stability. The two common enzyme immobilization (on the working electrode) techniques involve (i) enzyme/bovine serum albumin crosslinked with glutaraldehyde (House et al. 2007) and (ii) electrochemical growth of a conductive polymer matrix that incorporates the enzyme as charge balancing anions within the growing cationic polymer chains (McMahon et al. 2005). The long term stability and activity of these immobilized enzymes is however of concern for implantable biosensors. While sensor degradation due to loss of enzyme activity is rare (Updike et al. 1994), reports have indicated that inhibition of enzyme catalysis can be caused by transition metal ions, such as Zn2+ and Fe2+ (Binyamin et al. 2001), as well by low molecular weight serum components (Gerritsen et al. 1999). Moreover, recent studies have shown that while glucose sensors loaded with excess glucose oxidase could extend the life time of the sensor (Yu et al. 2005a), any excess free (uncrosslinked) glucose oxidase originally entrapped within the glutaraldehyde crosslinked enzyme layer can slowly leach out and thereby contributing to a decline in sensitivity over time (House et al. 2007). Thus, optimization of the amount of enzyme and crosslinking agent with respect to sensitivity is critical to extend the functional in vivo life time.

Due to the intricate relationship between the catalytic activity of an enzyme and its immobilization protocol, various immobilization protocols have been reported. In particular, nanostructured supports are believed to be able to retain the catalytic activity as well as ensure the immobilization efficiency of the enzyme to a large extent (Guto et al. 2007; Kim et al. 2006). Enhanced stability (temperature, environment), and efficiency of various enzymes have been reported upon their immobilization onto electrospun nanofibers, nanoparticles and nano-forests of nanowires and nanotubes as well as nanostructured ceramics (Guto et al. 2007; Kim et al. 2008; Phadtare et al. 2004; Wang et al. 2009). While a more detailed understanding of the stability enhancement mechanism is beyond the scope of this review, several factors can be at play such as (i) the large surface areas of these nanostructures which reduce mass transfer limitations, (ii) multiple sites for interaction and attachment of the enzymes to promote stability, (iii) well defined pore size of the nanostructured supports that suit the dimensions of protein molecules. Whatever the reason might be, such nanostructured supports for enzyme immobilization could be a potential vehicle to not only enhance implantable biosensor lifetime but also modify device architecture to alleviate some of the issues discussed earlier in this review. For example, the CNT nanoelectrode ensemble described above (Figure 7) (Lin et al. 2004) can be used to immobilize enzymes to achieve both enzymatic stability as well as improve sensor sensitivity. Moreover, such nanoelectrode configuration can be overcoated with hydrogels to improve its antifouling properties. Such design considerations might not only improve the lifetime of an implantable biosensor but also facilitate extreme miniaturization and enhance signal-to-noise ratio.

We conclude this section with a note on the emergence of non-enzymatic detection of metabolites as a potent tool for continuous monitoring of metabolites. Important metabolites such as glucose have been reported to show a facile oxidation peak at nanostructured electrodes such as Pt nano forests(Yuan et al. 2005), Pt-Pb alloy nanowires (Wang et al. 2008a), gold nanoparticles (Zhou et al. 2009), alloy nanostructures (containing Pt, Pb, Au, Pd and Rh) (Myung et al. 2009) owing to their high surface area and electrocatatalytic activity. In particular, the high surface area of these electrodes has been utilized to overcome issues of sensitivity discussed above. Such highly sensitive, nonenzymatic metabolite detection is however hindered by its lack of specificity and rapid loss in sensitivity as a result of surface poisoning due to adsorbed intermediates and chloride ions. For this, nanostructured electrodes based on carbon nanotubes (Wang et al. 2007; Ye et al. 2004) and carbon nanotube/metal nanoparticle combinations (Wang and Zhang 2001; Zhou et al. 2009) have also been used not only to lower operating potentials but also alleviate surface poisoning. While the field of non enzymatic detection for implantable sensors is still nascent, such methodologies are expected to further improve the field because of the miniaturization requirements and enzymatic stability issues discussed above.

2.6. Limit of Detection

Limit of detection of an implantable sensor refers to the lowest change in analyte concentration that it can be detected. This is a critical parameter for monitoring analytes present at ultra-low levels, like glutamate in the brain (McMahon et al. 2005) and glutamic oxaloacetic transaminase in the liver (Huang et al. 2006).

Limit of detection can also be lowered by using the nano-/microelectrodes discussed earlier (Guiseppi-Elie et al. 2009; Lin et al. 2004; Rahman and Guiseppi-Elie 2009). This is because they experience hemispherical diffusional profiles, thereby imparting stir-independence to sensor responses and lowering the limit of detection (Barton et al. 2004). To alleviate the low sensitivity of individual nanoelectrodes, ensembles of nanoelectrode can be used in the form of an array to allow a cumulative and hence larger response (Lin et al. 2004). More recently, in the area of point of care immunosensors, carbon nanotube forests have been utilized to lower H2O2 limits of detection down to the pico-molar range (Yu et al. 2006b). Whether such chemical amplification techniques can be used in implantable biosensors remains to be shown. Having said this, working electrode modification with nanoparticles discussed above, is also expected to improve the limit of detection of implantable sensors. Keeping in mind the high cost involved in the design of nanoelectrodes, Karyakin et al. (Karyakin et al. 2009) have employed nanostructuring of the enzyme layer rather than the working electrodes and have achieved a two orders of magnitude lower detection limit (10−9 nM of H2O2) without a decrease of sensitivity compared to sensor with no enzyme nanostructuring. While optimization in such enzyme nanostructuring will further improve the limit of detection, a combinatorial approach involving enzyme nanostructuring on a nano-/micro-electrodes together with effective modifications in sensor architecture (McMahon et al. 2005) is expected to further reduce the limit of detection.

2.7 Toxicity and Biocompatibility of Nanomaterials and the Future of Nanotechnology in Health Care

Having discussed the diverse advantages of nanotechnology to improve the performance of implantable systems such as biosensors and stents, this section provides an overview of the toxicity of nanomaterials and the future of nanotechnology in implantable biosensors. This discussion is important not only for the completeness of this review but in view of the fact that the various nanoparticles used in these implantable devices can eventually enter the human body if particular care is not exerted to inhibit such action. While there are two extreme viewpoints on the health risk of nanomaterials namely that nanomaterials pose no health risks or that they pose extreme risk, the reality may be somewhere in between. For example, the inflammation and foreign body response of a nanotextured surface is found to be lesser than a flat surface (Ainslie and Desai 2008; Ainslie et al. 2008; Desai et al. 2000; Popat et al. 2007; Sahlin et al. 2006), but the small size of nanoparticles, similar to that of carbon aerosols, can facilitate entry into the human body through various means and could cause potential health risks (Hoet et al. 2004; Hurt et al. 2006; Lacerda et al. 2006). In the case of implantable biosensors, it can be argued that these nanomaterials are not directly in contact with the tissue but are buried deep inside the sensor and so the problem of their toxicity arise only when potential leaching is a concern. Covalent coupling of nanomaterials to other functional component of the sensor can significantly minimize their potential to leach out, thereby eliminating any potential toxicity issue. At the same time, more studies are needed to quantify the immunogenicity of nanoparticles as well as their pharmacokinetics. Investigations into the effect of nanoparticle size and surface properties on immunogenicity may also help deduce a critical size beyond which the movement of the nanoparticles in the body is significantly restricted. Unfortunately, such studies should be performed for each nanomaterial and the likelihood of universality appears remote. Similarly, improvements in the resolution of various 3D tomographic techniques are needed to ultimately decipher the fate/transport/uptake of nanomaterials at the vicinity of the implant.

3. Summary and Future Perspectives

Since their discovery 40 years ago, Clark type biosensor technologies have seen considerable growth in terms of device complexity, usability and their ability to enter the commercial market. However, over the last decade this growth has accelerated tremendously thanks to the burgeoning field of nanotechnology. In this paper, we have made an effort to provide a comprehensive overview on the emerging synergy between implantable electrochemical biosensors and nanotechnology. A major thrust of this synergy between implantable biosensors and nanotechnology has been to tackle two issues, namely miniaturization and post-implantation inflammation. Since the amount of inflammation depends on the size of the implanted device, nanotechnology has been used to not only decrease inflammation but also to considerably miniaturize the implant size. Similarly, various kinds of nanoparticles, nanotubes and nanowires have been used to improve basic biosensor parameters such as sensitivity, selectivity, etc.

Nanotechnology based advances in the implantable device field have opened up a lot of opportunities, while at the same time raised some concerns. One pressing issue to tackle is the biocompatibility of nanomaterials that are used to enhance implantable biosensor performance. Apart from regular toxicology studies, one interesting avenue is the potential incorporation of imaging capability (using fluorescent nanoparticles) onto implantable devices. This would not only track their fate as a function of time, fibrotic encapsulation and device degradation but also assist in deciphering the capacity of leached nanomaterials. Such imaging capability would also help in easy explantation of the sensor at the end of its useful lifetime. Another effort towards this end would be the realization of biodegradable implantable devices, which can be triggered to biodegrade at the end of their useful lifetime similar to biodegradable sutures used for surgery. The combination of biocompatible and biodegradable materials within the same implantable device is not trivial but not impossible considering the tremendous growth of nanotechnology in the years to come.

Finally, efforts to develop an implantable biosensor for a particular analyte (mostly glucose) should be supplemented with research on implantable biosensors for multiple analyte detection. Such a step will be the key to building sensor robustness, which is expected to increase confidence levels in analyte readings. Moreover, the availability of monitoring multiple metabolites can assist in early disease detection. Contrary to the widespread notion that this would naturally be an extension of single analyte biosensor this task is not trivial because all of the body metabolites are interdependent, and in some cases, patient (physiology) dependant. The developing area of nanotechnology together with the elegant and multi disciplinary research involving new sensing concepts is well suited to provide a combinatorial sensing motif similar to point-of-care array detection methodologies. Such capability would certainly open the door for the development of highly sensitive, multi-analyte and multi-metabolite sensing platforms. This is expected to provide the user with not only the ability to monitor common disorders but also determine which of his/her daily habits exacerbate metabolic imbalances.

Acknowledgements

Financial support for this study was obtained from US Army Medical Research Grants (#DAMD17-02-1-0713, #W81XWH-04-1-0779, #W81XWH-05-1-0539 and # W81XWH-07-10668), NIH/NHLBI 1-R21-HL090458-01, AFOSR FA9550-09-1-0201, NSF CBET-0828771/0828824, NIH ES013557, Telemedicine and Advanced Technology Research Center (TATRC) at the U.S. Army Medical Research and Materiel Command (USAMRMC) (Award No. W81XWH-09-1-0711) and National Institute of Biomedical Imaging & Bioengineering award (R43EB011886). The authors would like to thank L.L. Qiang, D. Abanulo and V. Ustach for useful discussions.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Abidian MR, Martin DC. Adv. Func. Mat. 2009;19(4):573–585. [Google Scholar]

- Adiga SP, Curtiss LA, Elam JW, Pellin MJ, Shih CC, Shih CM, Lin SJ, Su YY, Gittard SD, Zhang J, Narayan RJ. J. Minerals, Met. Materials Soc. 2008;60(3):26–32. [Google Scholar]

- Ainslie KM, Desai TA. Lab on a Chip - Miniaturization for Chemistry and Biology. 2008;8(11):1864–1878. doi: 10.1039/b806446f. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ainslie KM, Sharma G, Dyer MA, Grimes CA, Pishko MV. Nano Lett. 2005;5(9):1852–1856. doi: 10.1021/nl051117u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ainslie KM, Tao SL, Popat KC, Desai TA. ACS Nano. 2008;2(5):1076–1084. doi: 10.1021/nn800071k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Albery WJ, Bartlett PN, Craston DH. J. Electroanal. Chem. 1985;194(2):223–235. [Google Scholar]

- Allen BL, Kichambare PD, Star A. Adv. Mat. 2007;19(11):1439–1451. [Google Scholar]

- Anantha Ramakrishna S. Reports on Progress in Physics. 2005;68(2):449–521. [Google Scholar]

- Armour JC, Lucisano JY, McKean BD, Gough DA. Diabetes. 1990;39(12):1519–1526. doi: 10.2337/diab.39.12.1519. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arrigan DWM. Analyst. 2004;129(12):1157–1165. doi: 10.1039/b415395m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Asuri P, Karajanagi SS, Kane RS, Dordick JS. Small. 2007;3(1):50–53. doi: 10.1002/smll.200600312. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Atrash SSE, O'Neill RD. Electrochim. Acta. 1995;40:2791–2797. [Google Scholar]

- Avouris P, Chen Z, Perebeinos V. Nature Nanotech. 2007;2(10):605–615. doi: 10.1038/nnano.2007.300. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baetzold RC. Inorganic Chemistry. 1981;20(1):118–123. [Google Scholar]

- Baravik I, Tel-Vered R, Ovits O, Willner I. Langmuir. 2009 doi: 10.1021/la902074w. DOI:10.1021/la902074w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barton AC, Collyer SD, Davis F, Gornall DD, Law KA, Lawrence ECD, Mills DW, Myler S, Pritchard JA, Thompson M, Higson SPJ. Biosens. Bioelect. 2004;20(2):328–337. doi: 10.1016/j.bios.2004.02.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bell AT. Science. 2003;299(5613):1688–1691. doi: 10.1126/science.1083671. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bernards DA, MacAya DJ, Nikolou M, Defranco JA, Takamatsu S, Malliaras GG. J. Mat. Chem. 2008;18(1):116–120. [Google Scholar]

- Besteman K, Lee JO, Wiertz FGM, Heering HA, Dekker C. Nano Lett. 2003;3(6):727–730. [Google Scholar]

- Bharathi S, Nogami M. Analyst. 2001;126(11):1841–1946. doi: 10.1039/b105318n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bhardwaj U, Papadimitrakopoulos F, Burgess DJ. J. Diabetes Sci. Technol. 2008;2(6):1016–1029. doi: 10.1177/193229680800200611. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bhardwaj U, Sura R, Papadimitrakopoulos F, Burgess DJ. J. Diabetes Sci. Technol. 2007;1(1):8–17. doi: 10.1177/193229680700100103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Binyamin G, Chen T, Heller A. J. Electroanal. Chem. 2001;500(1–2):604–611. [Google Scholar]

- Bowden EF, Hawkridge FM, Blount HN. J. electroanal. chem. interfacial electrochem. 1984;161(2):355–376. [Google Scholar]

- Brauker JH, Carr-Brendel VE, Martinson LA, Crudele J, Johnston WD, Johnson RC. J. Biomed. Mat. Res. 1995;29(12):1517–1524. doi: 10.1002/jbm.820291208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Calvo EJ, Etchenique R, Danilowicz C, Diaz L. Anal. Chem. 1996;68:4186–4193. doi: 10.1021/ac960170n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cass AEG, Davis G, Francis GD, Hill AO, Aston W, Higgins J, Plotkin EV, Scott LDL, Turner APF. Anal. Chem. 1984;56(4):667–671. doi: 10.1021/ac00268a018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chattopadhyay K, Mazumdar S. Bioelectrochem. 2001;53(1):17–24. doi: 10.1016/s0302-4598(00)00092-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen B, Cui T, Liu Y, Varahramyan K. Solid-State Electronics. 2003;47:841–847. [Google Scholar]

- Chen Q, Pamidi PVA, Wang J, Kutner W. Anal. Chim. Acta. 1995;306(2–3):201–208. [Google Scholar]

- Chen S, Yuan R, Chai Y, Zhang L, Wang N, Li X. Biosens. Bioelectron. 2007;22(7):1268–1274. doi: 10.1016/j.bios.2006.05.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen T, Barton SC, Binyamin G, Gao Z, Zhang Y, Kim H-H, Heller A. J Amer. Chem. Soc. 2001;123(35):8630–8631. doi: 10.1021/ja0163164. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Connor EE, Mwamuka J, Gole A, Murphy CJ, Wyatt MD. Small. 2005;1(3):325–327. doi: 10.1002/smll.200400093. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crespi F. Anal. Biochem. 1991;194(1):69–76. doi: 10.1016/0003-2697(91)90152-j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dai YQ, Shiu KK. Electroanalysis. 2004;16(20):1697–1703. [Google Scholar]

- De Corcuera JIR, Cavalieri RP, Powers JR. J. Electroanal. Chem. 2005;575(2):229–241. [Google Scholar]

- Desai TA, Chu WH, Tu JK, Beattie GM, Hayek A, Ferrari M. Biotechnol. Bioengg. 1998;57(1):118–120. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-0290(19980105)57:1<118::aid-bit14>3.0.co;2-g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Desai TA, Hansford D, Ferrari M. J. Membrane Sci. 1999;159(1–2):221–231. [Google Scholar]

- Desai TA, Hansford DJ, Leoni L, Essenpreis M, Ferrari M. Biosens. Bioelectron. 2000;15(9–10):453–462. doi: 10.1016/s0956-5663(00)00088-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Desai TA, West T, Cohen M, Boiarski T, Rampersaud A. Adv. Drug Delivery Rev. 2004;56(11):1661–1673. doi: 10.1016/j.addr.2003.11.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elam JW, Routkevitch D, Mardilovich PP, George SM. Chem. Mat. 2003;15(18):3507–3517. [Google Scholar]

- Engheta N, Salandrino A, Alù A. Physical Review Letters. 2005;95(9):1–4. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevLett.95.095504. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Errachid A, Ivorra A, Aguilo J, Villa R, Zine N, Bausells J. Sensors and Actuators, B: Chemical. 2001;78(1–3):279–284. [Google Scholar]

- Fan C, Li G, Zhu J, Zhu D. Anal. Chim. Acta. 2000;423(1):95–100. [Google Scholar]

- Ferri T, Poscia A, Santucci R. Bioelectrochem. Bioener. 1998;45(2):221–226. [Google Scholar]

- Fiorito S, Serafino A, Andreola F, Togna A, Togna G. J. Nanosci. Nanotechnol. 2006;6(3):591–599. doi: 10.1166/jnn.2006.125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fischer U, Hidde A, Herrmann S, Von Woedtke T, Rebrin K, Abel P. Biomedica Biochimica Acta. 1989;48(11–12):965–968. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Forzani ES, Zhang H, Nagahara LA, Amlani I, Tsui R, Tao N. Nano Lett. 2004;4(9):1785–1788. [Google Scholar]

- Foulds NC, Lowe CR. Anal. Chem. 1988;60(22):2473–2478. doi: 10.1021/ac00173a008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frost M, Meyerhoff ME. Anal. Chem. 2006;78(21):7370–7377. doi: 10.1021/ac069475k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frost MC, Batchelor MM, Lee Y, Zhang H, Kang Y, Oh B, Wilson GS, Gifford R, Rudich SM, Meyerhoff ME. Microchemical Journal. 2003;74(3):277–288. [Google Scholar]

- Frost MC, Meyerhoff ME. Methods in Enzymology. 2004;381:704–715. doi: 10.1016/S0076-6879(04)81045-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frost MC, Rudich SM, Zhang H, Maraschio MA, Meyerhoff ME. Anal. Chem. 2002;74(23):5942–5947. doi: 10.1021/ac025944g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gajovic N, Habermuller K, Warsinke A, Schuhmann W, Scheller FW. Electroanalysis. 1999;11:1377–1383. [Google Scholar]

- Galeska I, Chattopadhyay D, Moussy F, Papadimitrakopoulos F. Biomacromolecules. 2000;1(2):202–207. doi: 10.1021/bm0002813. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Galeska I, Chattopadhyay D, Papadimitrakopoulos F. J. Macromol. Sci. Pure and Appl. Chem. A. 2002;39(10):1207–1222. [Google Scholar]

- Galeska I, Hickey T, Moussy F, Kreutzer D, Papadimitrakopoulos F. Biomacromolecules. 2001;2(4):1249–1255. doi: 10.1021/bm010112y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Galeska I, Kim TK, Patil SD, Bhardwaj U, Chatttopadhyay D, Papadimitrakopoulos F, Burgess DJ. AAPS J. 2005;07(01):E231–E240. doi: 10.1208/aapsj070122. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gerritsen M, Jansen JA, Lutterman JA. The Netherlands Journal of Medicine. 1999;54(4):167–179. doi: 10.1016/s0300-2977(99)00006-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ghindilis AL, Atanasov P, Wilkins E. Electroanalysis. 1997;9(9):661–674. [Google Scholar]

- Gifford R, Kehoea JJ, Barnesa SL, Kornilayev BA, Alterman MA, Wilson GS. Biomaterials. 2006;27:2587–2598. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2005.11.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gilardi G, Fantuzzi A. Trends in Biotechnol. 2001;19(11):468–476. doi: 10.1016/s0167-7799(01)01769-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gilligan BJ, Shults MC, Rhodes RK, Updike SJ. Diabetes Care. 1994;17(8):882–887. doi: 10.2337/diacare.17.8.882. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gooding JJ. Electrochim. Acta. 2005;50(15):3049–3060. [Google Scholar]

- Gorton L, Lindgren A, Larsson T, Munteanu FD, Ruzgas T, Gazaryan I. Anal. Chim. Acta. 1999;400(1–3):91–108. [Google Scholar]

- Gough DA, Lucisano JY, Tse PHS. Anal.Chem. 1985;57(12):2351–2357. doi: 10.1021/ac00289a042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gregg BA, Heller A. Anal. Chem. 1990;62(3):258–263. doi: 10.1021/ac00202a007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gregg BA, Heller A. J. Phys. Chem. 1991;95(15):5976–5980. [Google Scholar]

- Guiseppi-Elie A, Rahman ARA, Shukla NK. Electrochimica Acta. In Press, doi:10.1016/j.electacta. 2008 1012.1043. [Google Scholar]

- Guto PM, Kumar CV, Rusling JF. J. Phys. Chem. B. 2007;111(30):9125–9131. doi: 10.1021/jp071525h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hahm J, Lieber CM. Nano Lett. 2004;4(1):51–54. [Google Scholar]

- Hahn CEW. Analyst. 1998 June;123:57R–86R. doi: 10.1039/a708951a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hale PD, Inagaki T, Karan HI, Okamoto Y, Skotheim TA. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1989;111(9):3482–3484. [Google Scholar]

- Hall SB, Khudaish EA, Hart AL. Electrochim Acta. 1998;43(5–6):579–588. [Google Scholar]

- Hamachi I, Fujita A, Kunitake T. J Am. Chem. Soc. 1994;116(19):8811–8812. [Google Scholar]

- Harrison DJ, Turner RFB, Baltes HP. Anal. Chem. 1988;60(19):2002–2007. doi: 10.1021/ac00170a003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hermanson KD, Huemmerich D, Scheibel T, Bausch AR. Adv. Mat. 2007;19(14):1810–1815. [Google Scholar]

- Hickey T, Kreutzer D, Burgess DJ, Moussy F. Biomaterials. 2002a;23:1649–1656. doi: 10.1016/s0142-9612(01)00291-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hickey T, Kreutzer D, Burgess DJ, Moussy F. J. Biomed. Mat. Res. 2002b;61:180–187. doi: 10.1002/jbm.10016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoet PHM, Brulske-Hohlfeld I, Salata OV. J. Nanobiotechnol. 2004;2:12–22. doi: 10.1186/1477-3155-2-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- House JL, Anderson EM, Ward WK. J Diabetes Sci Technol. 2007;1(1):18–22. doi: 10.1177/193229680700100104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hrapovic S, Liu Y, Male KB, Luong JHT. Anal. Chem. 2004;76(4):1083–1088. doi: 10.1021/ac035143t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hu Y, Wilson GS. J. Neurochem. 1997a;68(4):1745–1752. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.1997.68041745.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hu Y, Wilson GS. J. Neurochem. 1997b;69(4):1484–1490. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.1997.69041484.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang D, Liao F, Molesa S, Redinger D, Subramanian V. J. Electrochem. Soc. 2003;150(7):G412–G417. [Google Scholar]

- Huang J, Momenzadeh M, Lombardi F. IEEE Design and Test of Computers. 2007;24(4):304–311. [Google Scholar]

- Huang XJ, Choi YK, Im HS, Yarimaga O, Yoon E, Kim HS. Sensors. 2006;6(7):756–782. [Google Scholar]

- Hurt RH, Monthioux M, Kane A. Carbon. 2006;44(6):1028–1033. [Google Scholar]

- Irhayem EA, Elzanowska H, Jhas AS, Skrzynecka B, Birss V. J. Electroanal. Chem. 2002;538–539:153–164. [Google Scholar]

- Ishihara K, Nakabayashi N, Nishida K, Sakakida M, Shichiri M. ACS Symposium Series (Diagnostic Biosensor Polymers) 1994;556:194–210. [Google Scholar]

- Ishihara K, Tanaka S, Furukawa N, Kurita K, Nakabayashi N. J. Biomed. Mat. Res. 1996;32(3):391–399. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-4636(199611)32:3<391::AID-JBM12>3.0.CO;2-K. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iwai H. Microelec. Engg. 2009;86(7–9):1520–1528. [Google Scholar]

- Jia J, Wang B, Wu A, Cheng G, Li Z, Dong S. Anal. Chem. 2002;74(9):2217–2223. doi: 10.1021/ac011116w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson KW, Mastrototaro JJ, Howey DC, Brunelle RL, Burden-Brady PL, Bryan NA, Andrew CC, Rowe HM, Allen DJ, Noffke BW, McMahan WC, Morff RJ, Lipson D, Nevin RS. Biosen. Bioelectron. 1992;7(10):709–714. doi: 10.1016/0956-5663(92)85053-d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Joshi PP, Merchant SA, Wang Y, Schmidtke DW. Anal. Chem. 2005;77(10):3183–3188. doi: 10.1021/ac0484169. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaehler T. Clin Chem. 1994;40(9):1797b–1799b. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaku T, Karan HI, Okamoto Y. Anal. Chem. 1994;66(8):1231–1235. doi: 10.1021/ac00080a006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kang BS, Wang HT, Ren F, Pearton SJ, Morey TE, Dennis DM, Johnson JW, Rajagopal P, Roberts JC, Piner EL, Linthicum KJ. App. Phys. Lett. 2007;91(25):252103–252104. [Google Scholar]

- Karyakin AA, Kuritsyna EA, Karyakina EE, Sukhanov VL. Electrochim. Acta. 2009;54(22):5048–5052. [Google Scholar]

- Katz I, Willner I. ChemPhysChem. 2004;5:1084–1104. doi: 10.1002/cphc.200400193. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kerner W, Kiwit M, Linke B, Keck FS, Zier H, Pfeiffer EF. Biosensors and Bioelectronics. 1993;8(9–10):473–482. doi: 10.1016/0956-5663(93)80032-k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khan GF, Ohwa M, Wemet W. Anal. Chem. 1996;68(17):2939–2945. doi: 10.1021/ac9510393. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim CS, Oh SM. Electrochim. Acta. 1996;41(15):2433–2439. [Google Scholar]

- Kim J, Grate JW, Wang P. Chem. Engg. Sci. 2006;61(3):1017–1026. [Google Scholar]

- Kim J, Grate JW, Wang P. Trends in Biotechnol. 2008;26(11):639–646. doi: 10.1016/j.tibtech.2008.07.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim SN, Rusling JF, Papadimitrakopoulos F. Adv. Mat. 2007;19(20):3214–3228. doi: 10.1002/adma.200700665. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim WY, Choi YC, Min SK, Cho Y, Kim KS. Chemical Society Reviews. 2009;38(8):2319–2333. doi: 10.1039/b820003c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim YD, Dordick JS, Clark DS. Biotechnol. Bioengg. 2001;72(4):475–482. doi: 10.1002/1097-0290(20010220)72:4<475::aid-bit1009>3.0.co;2-f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kluge JA, Rabotyagova O, Leisk GG, Kaplan DL. Trends in Biotechnol. 2008;26(5):244–251. doi: 10.1016/j.tibtech.2008.02.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koch CC, Morris DG, Lu K, Inoue A. MRS Bulletin. 1999;24(2):54–58. [Google Scholar]

- Kohma T, Oyamatsu D, Kuwabata S. Electrochem. Comm. 2007;9(5):1012–1016. [Google Scholar]

- Koopal CGJ, Feiters MC, Nolte RJM, De Ruiter B, Schasfoort RBM, Czajka R, Van Kempen H. Syn. Met. 1992;51(1–3):397–399. [Google Scholar]

- Kosela E, Elzanowska H, Kutner W. Anal. Bioanal. Chem. 2002;373(8):724–728. doi: 10.1007/s00216-002-1308-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kotzian P, Brazdilova P, Rezkova S, Kalcher K, Vytras K. Electroanalysis. 2006;18(15):1499–1504. [Google Scholar]

- Krishnan S, Weinman CJ, Ober CK. J. Mat. Chem. 2008;18(29):3405–3413. [Google Scholar]

- Kulys J, Wang L, Hansen HE, Buchrasmussen T, Wang J, Ozsoz M. Electroanalysis. 1995;7:92–94. [Google Scholar]

- Kumar SA, Chen SM. Talanta. 2007;72(2):831–838. doi: 10.1016/j.talanta.2006.10.038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kvist PH, Iburg T, Aalbaek B, Gerstenberg M, Schoier C, Kaastrup P, Buch-Rasmussen T, Hasselager E, Jensen HE. Diabetes Technol. Therapeutics. 2006;8(5):546–559. doi: 10.1089/dia.2006.8.546. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kyrolainen M, Rigsby P, Eddy S, Vadgama P. Acta Anaesthesiologica Scandinavica. 1995;104:55–60. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-6576.1995.tb04255.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lacerda L, Bianco A, Prato M, Kostarelos K. Adv. Drug Delivery Rev. 2006;58(14):1460–1470. doi: 10.1016/j.addr.2006.09.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lei C, Zhang Z, Liu H, Deng J. J. Electroanal. Chem. 1996;419(1):93–98. [Google Scholar]

- Li C, Han J, Ahn CH. Biosen. Bioelectron. 2007;22(9–10):1988–1993. doi: 10.1016/j.bios.2006.08.043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li X, Wu J, Gao N, Shen G, Yu R. Sensors and Actuators, B: Chemical. 2006;117(1):35–42. [Google Scholar]

- Li Y, Lenigk R, Wu X, Gruendig B, Dong S, Renneberg R. Electroanalysis. 1998;10(10):671–676. [Google Scholar]

- Lin Y, Lu F, Tu Y, Ren Z. Nano Lett. 2004;4(2):191–195. [Google Scholar]

- Liu G, Wang J, Kim J, Jan MR, Collins GE. Analytical Chemistry. 2004;76(23):7126–7130. doi: 10.1021/ac049107l. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu J, Wang J. Food Technol. Biotechnol. 2001;39(1):55–58. [Google Scholar]

- Liu Q, Lu X, Li J, Yao X, Li J. Biosens. Bioelectron. 2007a;22(12):3203–3209. doi: 10.1016/j.bios.2007.02.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu X, Xu Y, Ma X, Li G. Sensors and Actuators, B: Chemical. 2005;106(1):284–288. [Google Scholar]

- Liu Y, Cui T, Varahramyan K. Solid-State Electronics. 2003;47(9):1543–1547. [Google Scholar]

- Liu Y, Wu S, Ju H, Xu L. Electroanalysis. 2007b;19(9):986–992. [Google Scholar]

- Lopez CA, Fleischman AJ, Roy S, Desai TA. Biomaterials. 2006;27(16):3075–3083. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2005.12.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Loss D. Nanotechnology. 2009;20(43) doi: 10.1088/0957-4484/20/43/430205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Loss D, DiVincenzo DP. Physical Review A. 1998;57(1):120. [Google Scholar]