Abstract

Objective

This study assessed the relationship between multiple indicators of ‘real-world’ functioning and scores on a brief performance-based measure of functional capacity known as the Brief University of California San Diego (UCSD) Performance-based Skills Assessment (UPSA-B) in a sample of 205 patients with either serious bipolar disorder (n = 89) or schizophrenia (n = 116).

Methods

Participants were administered the UPSA-B and assessed on the following functional domains: (i) independent living status (e.g., residing independently as head of household, living in residential care facility); (ii) informant reports of functioning (e.g., work skills, daily living skills); (iii) educational attainment and estimated premorbid IQ as measured by years of education and Wide Range Achievement Test reading scores, respectively; and (iv) employment.

Results

Better scores on the UPSA-B were associated with greater residential independence after controlling for age, diagnosis, and symptoms of psychopathology. Among both bipolar disorder and schizophrenia patients, higher UPSA-B scores were significantly related to better informant reports of functioning in daily living skills and work skills domains. Greater estimated premorbid IQ was associated with higher scores on the UPSA-B for both schizophrenia and bipolar disorder participants. Participants who were employed scored higher on the UPSA-B when controlling for age and diagnosis, but not when controlling for symptoms of psychopathology.

Conclusions

These data suggest the UPSA-B may be useful for assessing capacity for functioning in a number of domains in both people diagnosed with schizophrenia and bipolar disorder.

Keywords: employment, functional capacity, functional outcome, independence, severe, mental illness

Severe mental illness is associated with deficits in everyday living skills that impact quality of life (1–7). Indeed, the World Health Organization (WHO) ranks schizophrenia and bipolar disorder as having a high level of impact in terms of years of life lost due to disability across the lifespan (8), most likely through disrupting the ability to maintain employment, reside independently, and to consistently manage everyday functional abilities (e.g., self-care, finances).

Despite this overall disruption, some patients manage to function well in their environments. Others achieve functional levels that are near to functional recovery through psychosocial treatments and medication regimens that allow them to maintain employment and reside independently. As a result, clinicians are faced with the difficult task of determining patients’ abilities to adequately achieve these milestones. However, literature suggests that clinician judgment alone is not adequate for determining one’s ability to function independently in the ‘real world’ (9, 10). These findings have led to the examination of other, more objective methods of assessing functional capacity in severely mentally ill people. Several studies suggest that performance-based measures of functional capacity, in which patients are asked to perform specific functional skills in controlled settings, may be particularly useful for making this determination (11, 12). For example, Mausbach et al. (13) found that the Brief University of California San Diego (UCSD) Performance-based Skills Assessment (UPSA-B) was accurate in predicting independent residential status in a sample of middle-aged and older patients with schizophrenia. In another study of middle-aged and older patients with schizophrenia, greater engagement in community responsibilities (e.g., working for pay, attending school) was associated with higher scores on the UPSA-B (14). A similar study of middle-aged and older Latinos with schizophrenia found that higher scores on the UCSD Performance-based Skills Assessment (UPSA) (15) were associated with greater involvement in community responsibilities (16). Finally, a series of studies (4, 17) found that functional capacity measures were much more substantial predictors of three different aspects of real-world outcomes (residential, social, vocational) than symptoms or even cognitive performance. These studies point to the potential usefulness of performance-based measures for predicting community functioning in the severely mentally ill and thereby offer clinicians and researchers a valid tool for assessing capacity to achieve functional milestones.

Almost all studies of performance-based measures have focused on middle-aged and elderly patients with schizophrenia. Few studies have examined the usefulness of these measures for predicting community functioning in other seriously mentally ill populations (e.g., bipolar disorder). Among the few studies of functioning in bipolar disorder, Gildengers and colleagues (18) utilized a direct observational approach to assess self-care functioning and found self-care to be associated with cognitive functioning in older patients with bipolar disorder. Later, Depp and colleagues (19) found older, community-dwelling outpatients with bipolar disorder to have substantially lower performance on the full version of the UPSA relative to a normal control sample and that UPSA performance was significantly related to subjective illness burden as measured by the Quality of Well-Being scale (20). However, both of these studies were restricted to older adults, and neither of these studies examined the relationship between functioning and factors such as employment and residential status (e.g., living independently versus with a caretaker), which may be particularly important not just for the patient (e.g., higher self-esteem) but for the broader community as a whole to reduce the financial burden to society associated with disability. As bipolar disorder can be marked by high levels of vocational, social, and residential disability (21), it would be important to examine whether the predictors of real-world outcomes with performance-based measures are similar to those observed in schizophrenia.

The purpose of this study was to examine the usefulness of the UPSA-B for prediction of ‘real-world’ functioning in a heterogeneous population of severely mentally ill patients. Specifically, we examined the concomitant relations between scores on the UPSA-B and the following measures of functional attainment in a sample of 205 subjects diagnosed with schizophrenia or bipolar I disorder: (i) residential living status, (ii) informant reports of functional abilities, (iii) histories of educational attainment, and (iv) histories of work attainment. In addition to overall relationships, secondary analyses were conducted (where possible) to determine if relations were significantly different by disease status (i.e., bipolar disorder versus schizophrenia).

Methods

Participants

Participants were 205 individuals aged 21 and over with serious mental illness: 116 were diagnosed with schizophrenia and 89 were diagnosed with bipolar I disorder. These subjects are participating in an ongoing study of clinical and neuropsychological indicators in relation to functional capacity (behaviors associated with day-to-day living skills). This manuscript, however, focuses on the validity of our performance-based measures for predicting real-world outcomes, with later work to focus on neuropsychological determinants of functional status. The subjects are participants in genetic studies of schizophrenia and bipolar I disorder conducted by the Epidemiology-Genetics Program in Psychiatry (Epigen) at the Johns Hopkins School of Medicine and have been invited to join the functional capacity study as a follow-on to previous studies. The projected size of the eventual functional capacity cohort is ~620 but may grow with additional funding.

Subjects are of full or mixed Ashkenazi Jewish (AJ) background (determined from ancestry of four grandparents) and reside largely in the United States; the focus on AJ ethnicity was adopted because of increased genetic homogeneity among this group. Subjects were initially recruited nationally through advertisements in newspapers and Jewish publications, talks given at community centers and synagogues, and through the Epigen Program Web site. Some subjects joined the Epigen studies as members of families multiplex for schizophrenia or bipolar disorder, other affected subjects joined along with their parents as case-parent triads, and still others have been recruited as the sole affected members of their families.

Details of recruitment, assessment, and consensus diagnostic procedures for the genetics studies are available in several publications (22–25). Briefly, subjects participating in the genetic studies were directly assessed (largely in their own homes) by skilled clinicians (master’s and Ph.D. level) using the Diagnostic Interview for Genetic Studies (26). Additional information from medical records, informant reports, and the Family Interview for Genetics Studies (http://zork.wustl.edu/nimh/home/m_interviews.html) was independently reviewed by at least two clinicians (Ph.D. or psychiatrist) prior to forming a consensus DSM-IV diagnosis, as well as consensus on a number of clinical indicators.

Subjects consenting to follow-up have been recruited via telephone and letter to participate in the functional capacity study; they are again being directly assessed in their own homes by members of the original team of clinical examiners using a battery of neuropsychological assessments [consistent with the Measurement and Treatment Research to Improve Cognition in Schizophrenia (MATRICS) battery (27, 28)], as well as the functional capacity, clinical, and other assessments described below.

Participants were all either outpatients or in residential treatment settings, and none were acutely hospitalized. Psychotropic medication usage was obtained by self-report. A total of 87% of the bipolar disorder group and 93% of the schizophrenia group were prescribed an atypical or typical antipsychotic, lithium or anticonvulsant, or an antidepressant. In the bipolar disorder group, a total of 50% were taking an antipsychotic, 70% lithium or anticonvulsant, and 47% an antidepressant. Among those with schizophrenia, a total of 89% were taking an antipsychotic, 36% lithium or anticonvulsant, and 47% an antidepressant. A significantly higher proportion of the schizophrenia group reported antipsychotic usage (chi-square [1] = 38.7, p < 0.001) whereas a greater number of those with bipolar disorder were taking lithium or anticonvulsants (chi-square [1] = 24.1, p < 0.001). The proportion prescribed antidepressants did not differ between diagnostic groups (chi-square [1] = 0.008, p = 0.999).

Measures

Functional abilities

Participants’ functional abilities were assessed using the UPSA-B (13). The UPSA-B is a measure of functional capacity in which patients are asked to perform everyday tasks in two areas of functioning: communication and finances. During the Communication subtest, participants are required to role-play exercises using an unplugged telephone (e.g., emergency call, dialing a number from memory, calling to reschedule a doctor’s appointment). For the Finance subtest, participants are required to count change, read a utility bill, and write and record a check for the bill. The UPSA-B requires approximately 10–15 minutes to complete, and raw scores are converted into scaled scores ranging from 0–100, with higher scores indicating better functional capacity.

Participants were rated with a modified version of the Specific Level of Functioning (SLOF) scale (29). This scale consisted of 36 items from the full version of the SLOF and assessed participants’ real-world functioning in the following five domains: (i) Physical Functioning (e.g., vision, hearing), (ii) Personal Care Skills (e.g., personal hygiene, dressing self), (iii) Interpersonal Relationships (e.g., initiates contact with others, communicates effectively), (iv) Activities (e.g., household responsibilities, shopping), and (v) Work Skills (e.g., works with minimal supervision, able to sustain work effort). Because the Physical Functioning subtest is intended for physically disabled individuals and not psychiatric populations, it was excluded from these analyses. Each of the 36 items is rated on a 5-point Likert scale indicating the frequency of the behavior and/or level of independence. We have used the SLOF in our previous studies of functional capacity and cognition in people with schizophrenia (4, 17), finding that impaired real-world functioning was related to UPSA scores for both UPSA-B and longer versions of the test. Scores were summed in each domain, with higher scores indicating better functioning. For the current study, ratings were generated in the typical manner, with raters being individuals quite familiar with the participant’s functioning (e.g., family members, friends, case managers). In the case that such individuals were unavailable (n = 27), examiners made the ratings based on their observation of the subject and his/her living conditions.

Psychopathology measures

Three scales were used to assess various psychiatric symptoms. First was the Positive and Negative Syndromes Scale (PANSS) (30), which assesses positive (e.g., delusions, hallucinations) and negative (e.g., blunted affect, poor rapport) symptoms of psychosis, as well as general symptoms of psychopathology (e.g., poor attention, lack of judgment) occurring in the previous week.

The second scale was the Beck Depression Inventory-II (BDI-II) (31), a 21-item questionnaire assessing depressive symptoms. Participants rated each of the 21 items on a scale from 0–3. A total depressive symptoms score is created by summing the 21 items. Our previous research with this scale has shown that depression severity contributes to the prediction of real-world outcomes but was minimally associated with UPSA performance.

The third scale was the Profile of Mood States–Bipolar form (POMS-Bi) (32), which consists of 72 mood adjectives assessing six mood domains: (i) Composed/Anxious (e.g., serene, shaky), (ii) Agreeable/Hostile (e.g., sympathetic, bad tempered), (iii) Elated/Depressed (e.g., lonely, joyful), (iv) Confident/Unsure (e.g., powerful, self-doubting), (v) Energetic/Tired (e.g., energetic, exhausted), and (vi) Clearheaded/Confused (e.g., attentive, perplexed). Participants rated each of the 72 items using a 4-point Likert-type scale (0 = much unlike this; 3 = much like this). Items from each domain were summed such that total scores were in the negative-mood direction (i.e., higher scores indicated greater experience of negative moods).

Substance use

All participants were asked to report the frequency with which they consumed 10 ounces of beer, 4 ounces of wine, or 1.5 ounces of spirits over the past month. Response options were on a 5-point Likert scale: 0 = never; 1 = one time or less per week; 2 = 2–3 times per week; 3 = 4–5 times per week; and 4 = 6–7 times per week. In addition, participants were asked to report the average quantity of alcohol they consumed each day they drank. Responses were also on a Likert scale: 0 = 0 drinks; 1 = 1–2 drinks; 2 = 3–4 drinks; 3 = 5–6 drinks; 4 = 7–10 drinks; 5 = 11–14 drinks; and 7 = 15 or more drinks. To estimate the number of drinks participants consumed per week, we computed the mean number of times participants consumed alcohol (e.g., 6–7 times per week was converted to 6.5) and multiplied this by the average amount consumed (e.g., 7–10 drinks was converted to 8.5 drinks). In addition to alcohol, all participants were asked whether or not they used the following substances over the past month: (i) cocaine, (ii) PCP, (iii) marijuana, (iv) sedatives/tranquilizers, (v) hallucinogens (e.g., acid, LSD), and (vi) stimulants (e.g., uppers, speed).

Results

We first examined demographic and health characteristics of our sample. Characteristics of the 205 participants are presented in Table 1. In addition, we examined the number of participants in each diagnostic group with active hallucinations and delusions. Active symptoms were defined as scoring at least moderate (≥ 4) on the Delusions and Hallucinatory Behavior questions of the PANSS. Among patients with schizophrenia, 52 reached the cutoff for delusions (44.8%) and 36 reached the cutoff for hallucinations (31.0%). Among participants with bipolar disorder, three (3.4%) reached the cutoff for delusions, and none scored at least moderate on the hallucinations item.

Table 1.

Characteristics of the sample

| Scale range | Bipolar disorder (n = 89) | Schizophrenia (n = 116) | t-value, X2 | p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age, mean (SD) | 48.7 (14.4) | 49.9 (9.0) | −0.70 | 0.487 | |

| Sex, n (%) | 1.96 | 0.162 | |||

| Male | 45 (51.6) | 70 (60.0) | |||

| Female | 44 (49.4) | 46 (40.0) | |||

| Years of education, mean (SD) | 14.9 (2.2) | 14.0 (2.4) | 3.00 | 0.003 | |

| WRAT standard score, mean (SD) | 107.4 (8.3) | 100.2 (11.8) | 4.85 | < 0.001 | |

| Employment status, n (%)a | 29.30 | < 0.001 | |||

| Not employed | 28 (32.2) | 72 (62.6) | |||

| Sheltered employment | 2 (2.3) | 11 (9.6) | |||

| Employed | 57 (65.5) | 32 (27.8) | |||

| Residential status, n (%)b | 30.72 | < 0.001 | |||

| Head of household, independent | 76 (86.4) | 59 (50.9) | |||

| Head of household, semi-independent | 2 (2.3) | 19 (16.4) | |||

| Not head of household, in community | 9 (10.2) | 24 (20.7) | |||

| Residential treatment facility | 1 (1.1) | 14 (12.7) | |||

| Age of illness onset, mean (SD) | 20.1 (8.0) | 20.5 (5.7) | −0.36 | 0.721 | |

| PANSS, mean (SD) | |||||

| Positive | 7–49 | 10.6 (3.8) | 16.2 (6.1) | −7.48 | < 0.001 |

| Negative | 7–49 | 10.1 (3.3) | 17.5 (8.0) | −8.23 | < 0.001 |

| General | 16–112 | 25.5 (7.7) | 32.4 (9.8) | −5.41 | < 0.001 |

| Total | 30–210 | 46.2 (12.1) | 66.0 (20.6) | −8.07 | < 0.001 |

| BDI total, mean (SD) | 0–63 | 8.6 (9.1) | 10.6 (9.4) | −1.52 | 0.131 |

| Alcoholic drinks per week, mean (SD) | 1.6 (3.3) | 1.0 (4.8) | 1.12 | 0.263 | |

| Substance use past month, n (%) | |||||

| Cocaine | 0 (0.0) | 1 (0.9) | 1.00d | ||

| PCP | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | – | ||

| Marijuana | 5 (5.6) | 4 (3.4) | 0.508d | ||

| Sedatives/tranquilizers | 0 (0.0) | 1 (0.9) | 1.00d | ||

| Hallucinogens | 0 (0.0) | 1 (0.9) | 1.00d | ||

| Stimulants | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | – | ||

| POMS scales, mean (SD)c | |||||

| Anxious | 0–36 | 13.0 (9.0) | 14.7 (8.1) | −1.32 | 0.188 |

| Hostile | 0–36 | 9.7 (7.5) | 10.0 (6.4) | −0.22 | 0.825 |

| Depressed | 0–36 | 13.0 (8.8) | 13.9 (7.6) | −0.74 | 0.460 |

| Unsure | 0–36 | 12.4 (7.7) | 14.9 (7.2) | −2.22 | 0.027 |

| Tired | 0–36 | 14.4 (7.8) | 15.3 (8.7) | −0.74 | 0.460 |

| Confused | 0–36 | 8.9 (8.0) | 12.5 (7.6) | −3.12 | 0.002 |

| SLOF scales, mean (SD) | |||||

| Personal care | 7–35 | 33.9 (2.3) | 31.0 (4.8) | 5.19 | < 0.001 |

| Communication | 7–35 | 31.3 (4.7) | 28.4 (6.3) | 3.55 | < 0.001 |

| Activities | 11–55 | 52.5 (5.0) | 48.5 (8.2) | 4.08 | < 0.001 |

| Work | 7–35 | 31.1 (4.8) | 26.2 (6.8) | 5.71 | < 0.001 |

| UPSA-B, mean (SD) | 0–100 | 88.7 (11.5) | 75.6 (20.8) | 5.36 | < 0.001 |

| UPSA-B Finances, mean (SD) | 0–50 | 45.7 (5.8) | 39.5 (11.1) | 4.80 | < 0.001 |

| UPSA-B Communication, mean (SD) | 0–50 | 43.0 (7.2) | 36.1 (11.1) | 5.07 | < 0.001 |

WRAT = Wide Range Achievement Test; PANSS = Positive and Negative Syndromes Scale; BDI = Beck Depression Inventory; POMS = Profile of Mood States; SLOF = Specific Level of Functioning; UPSA-B = Brief University of California San Diego (UCSD) Performance-based Skills Assessment.

Two bipolar participants and one schizophrenia participant were missing data.

One case in the bipolar sample was residing in a van and was coded as missing.

Data are for 85 participants with bipolar disorder and 101 participants with schizophrenia.

p-value for Fishers Exact Test.

Relationship between UPSA-B and residential status

We first examined UPSA-B scores by residential status. In these analyses, one participant reported residing in a van. Because of the difficulty coding this status using the criteria below, this participant was excluded from this analysis. The remaining participants were classified into one of four residential groups: Group 1: head of household, independent; Group 2: head of household, semi-independent; Group 3: not head of household, but in community; and Group 4: residential treatment facility. ‘Head of household, independent’ subjects can live alone or with others (e.g., with a partner, spouse, children, friends, or relatives) and have primary (if alone) or co-equal financial and/or logistical responsibility for the household. The ‘semi-independent’ qualification for Group 2 indicates that the subject bears only partial (and not co-equal) financial and/or logistical responsibility for the household: e.g., a person living in an apartment supervised by a treatment program, a subject holding a job but living with his parents and contributing financially or logistically to the household operation. Subjects classified as ‘not head of household, community’ are, for example, living in a group home or as a dependent in the home of their parents, children, etc. Subjects ‘in residential treatment facility’ have a degree of community exposure but require residence in a treatment environment.

Three analysis of variance (ANOVA) models were run to examine these effects. The first did not control for demographic variables. Model 2 controlled for age, psychiatric diagnosis, and symptoms of psychopathology (i.e., PANSS total scores). These particular covariates were selected because previous research suggested that age (13), psychiatric diagnosis (19, 33), and symptoms of psychopathology (13) may significantly covary with performance-based tests. Finally, Model 3 controlled for age, psychiatric diagnosis, symptoms of psychopathology, age of illness onset, and gender. For the present study, age of onset for patients with schizophrenia was defined as age at first psychosis. For patients with bipolar disorder, age of onset was defined as age at first manic, mixed, or major depressive episode.

Results of our uncontrolled model (Model 1), which accounted for 33.1% of variance, indicated there was a significant effect for residential status group (F = 32.97, df = 3,200, p < 0.001), with post-hoc tests indicating that participants who were independent heads of household (Group 1) scored significantly higher on the UPSA-B than those who were not heads of their households (Group 3; p < 0.001) and those residing in residential care facilities (Group 4; p < 0.001). Semi-independent heads of household (Group 2) scored significantly higher than those in residential treatment facilities (Group 4; p < 0.001). Finally, participants residing in the community but not head of their household (Group 3) scored significantly higher than those in residential treatment facilities (Group 4; p < 0.001).

Model 2 (R2 = 48.2%), which controlled for age, diagnosis, and symptoms of psychopathology, also found a significant effect for residential status (F =14.77, df = 3,197, p < 0.001). Post-hoc tests indicated similar residential status group differences as those in Model 1. Within this model, age was not significantly associated with UPSA-B scores (F = 2.84, df = 1, 197, p = 0.093), nor was diagnosis (F = 0.66, df = 1,197, p = 0.417). However, symptoms were significantly related to UPSA-B scores (F = 38.49, df = 1,197, p < 0.001), with more symptoms associated with worse functioning.

Table 2 presents results from our full model (Model 3) with covariate-adjusted means (M) and 95% confidence intervals (CI) for the four residential status subgroups. As seen here, a significant effect for residential status remained, with more independent groups scoring generally higher on the UPSA-B than less independent groups. For our covariates, age was negatively associated with UPSA-B scores. Diagnosis was not significant, and more severe symptoms of psychopathology were significantly associated with poorer UPSA-B scores. Although participants with a later age of onset tended to have higher UPSA-B scores, this relationship was not significant. Finally, gender was not significantly associated with UPSA-B scores. Because only two bipolar disorder participants were semi-independent (Group 2) and one was residing in a residential treatment facility, examination of these effects within diagnostic groups was not conducted.

Table 2.

Analysis of variance of UPSA-B scores by residential status

| Head of household, independent | 84.71 (82.29–87.14)a |

| Head of household, semi-independent | 82.65 (76.63–88.66)a,b |

| Not head, but in community | 76.50 (71.60–81.41)b |

| Residential treatment facility | 59.39 (51.84–66.94)c |

| Residential status | F = 13.07, p < 0.001 |

| Age | F = 4.92, p = 0.028 |

| Diagnosis | F = 1.15, p = 0.285 |

| Symptoms | F = 36.40, p < 0.001 |

| Age of onset | F = 3.71, p = 0.056 |

| Male | F = 1.03, p = 0.312 |

| R2 | 0.496 |

Values within residential status cells indicate estimated marginal (covariate adjusted) means with 95% confidence intervals. Within each model, groups with different superscripts are significantly different from one another.

Relationship between UPSA-B and SLOF scores

Our second analysis examined correlations between the UPSA-B and SLOF scales. For these, UPSA-B scores were significantly correlated with SLOF Personal Care (r205 = 0.35, p < 0.001), Communication (r205 = 0.30, p < 0.001), Activities (r205 = 0.63, p < 0.001), and Work (r205 = 0.48, p < 0.001) subscales. Secondary analyses examined partial correlations between UPSA-B and SLOF subscales while controlling for age, gender, symptoms of psychopathology, and age of onset. Results of these analyses indicated that UPSA-B scores remained significantly correlated with the SLOF Activities (partial correlation = 0.41, p < 0.001) and Work subscales (partial correlation = 0.16, p = 0.025), but the partial correlations for SLOF Personal Care (partial correlation = 0.052, p = 0.463) and Communication subscales (partial correlation = −0.122, p = 0.087) were no longer significant.

Within the schizophrenia group, the UPSA-B was significantly correlated with the SLOF Personal Care (r116 = 0.27, p = 0.003), Communication (r116 = 0.30, p = 0.001), Activities (r116 = 0.63, p < 0.001), and Work (r116 = 0.43, p < 0.001) subscales. In the bipolar disorder group, significant correlations were found between the UPSA-B and the Activities (r89 = 0.48, p < 0.001) and Work (r89 = 0.32, p = 0.003) subscales. No significant correlations were found for the Personal Care (r89 = 0.20, p = 0.07) and Communications (r89 = 0.05, p = 0.672) subscales in the bipolar disorder sample.

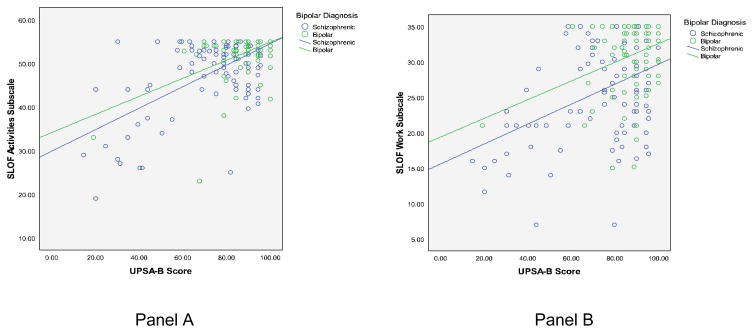

To determine if correlations were significantly different by diagnosis, we conducted r-to-z transformations and compared z-scores for the two diagnostic groups. Results of these analyses indicated that the correlations between UPSA-B and Personal Care (z = 0.51; p = 0.61), Communications (z = 1.81; p = 0.07), Activities (z = 1.53; p = 0.13), and Work (z = 0.90; p = 0.37) subscales did not differ between people with schizophrenia and bipolar disorder. Scatter plots with UPSA-B and the SLOF Activities and Work subscales are presented in Figure 1.

Fig. 1.

Correlations between Brief University of California San Diego (UCSD) Performance-based Skills Assessment (UPSA-B) scores and Specific Level of Functioning (SLOF) Activities (Panel A) and Work (Panel B) subscales by diagnostic group (bipolar versus schizophrenia).

Relationship between UPSA-B and educational and occupational attainment

We conducted several analyses examining the relationship between UPSA-B scores and both educational and occupational attainment. For educational attainment, we conducted two analyses. The first examined the correlation between years of education and UPSA-B scores. In this analysis, participants who received a General Educational Development test were assigned ‘12’ as their total years of education, and participants receiving a graduate or professional degree were coded as ‘17’. Two participants with schizophrenia were missing education data. Results of this analysis on the remaining 203 participants indicated a significant correlation between UPSA-B scores and years of education (r203 = 0.38, p < 0.001). The partial correlation, after controlling for age, gender, symptoms of psychopathology, and age of onset, was 0.26 (p < 0.001). Follow-up correlations for the schizophrenia and bipolar disorder groups indicated UPSA-B scores were significantly correlated with years of education in the schizophrenia sample (r114 = 0.43, p < 0.001), but not the bipolar disorder sample (r89 = 0.11, p = 0.30). Comparisons of these correlations using r-to-z transformations indicated the magnitude of the relationship between education and UPSA-B scores was significantly higher in the schizophrenia group (z = 2.43, p < 0.02).

A second analysis examined the correlation between scores on the UPSA-B and Standard Scores on the Wide Range Achievement Test–4th version (WRAT-4) (34), a global measure of estimated premorbid IQ. Results of this analysis indicated that higher UPSA-B scores were associated with higher estimated premorbid IQ (r205 = 0.44, p < 0.001), and the partial correlation was 0.26 (p < 0.001). Follow-up analyses for each diagnosis indicated significant correlations for both the schizophrenia (r116 = 0.40, p < 0.001) and bipolar disorder samples (r89 = 0.28, p < 0.01). These correlations were not significantly different from one another (z = 0.95, p = 0.34).

Next, we conducted analyses on occupational attainment. We first compared UPSA-B scores of participants who were currently employed versus those who were not. For our sample, one schizophrenia participant and two bipolar disorder participants were missing data, leaving 202 participants for the analysis. Examination of our data indicated that 100 participants were currently not employed, 13 were employed in work that was sheltered, and 89 were employed in nonsheltered jobs. Because of the small sample of sheltered participants, we collapsed these 13 participants into the nonemployed group to create a variable of ‘independent work’ (yes versus no). We then conducted ANOVAs comparing UPSA-B scores for these two groups. As with our analysis of residential status, we conducted three ANOVA models. Model 1 was our uncontrolled model; Model 2 controlled for age, diagnosis, and symptoms of psychopathology; and Model 3 controlled for age, diagnosis, symptoms of psychopathology, gender, and age of onset.

Results for Model 1 indicated that employed participants scored significantly higher on the UPSA-B (M = 88.3, 95% CI: 84.62–91.98) than unemployed participants (M = 75.91, 95% CI: 72.65–79.17) (F = 24.69, df = 1, 200, p < 0.001). Overall, this model accounted for 11.0% of the variance in UPSA-B scores.

In Model 2, which controlled for age, diagnosis, and symptoms of psychopathology, employment status was no longer significantly related to UPSA-B scores (F = 0.66, df = 1, 197, p = 0.419). Within this model, only symptoms of psychosis significantly predicted UPSA-B scores, with greater symptoms associated with lower UPSA-B scores (F = 60.50, df = 1, 197, p < 0.001). Overall, this model explained 36.7% of the variance in UPSA-B scores.

Results of Model 3 are presented in Table 3. A total of 39.7% of UPSA-B variance was explained using this model. As with Model 2, employment status was not significantly related to UPSA-B scores. Again, symptoms of psychopathology were significantly related to UPSA-B scores, as was age of illness onset, such that later onset was related to better functioning.

Table 3.

Analysis of UPSA-B scores by employment status

| Employed (n = 89) | 81.92 (78.36–85.27) |

| Not employed (n = 113) | 80.91 (77.91–83.91) |

| Employment status | F = 0.13, p = 0.719 |

| Age | F = 1.84, p = 0.177 |

| Diagnosis | F = 1.94, p = 0.165 |

| Symptoms | F = 59.92, p < 0.001 |

| Age of onset | F = 6.18, p = 0.014 |

| Male | F = 0.83, p = 0.365 |

| R2 | 0.397 |

Values within employment status cells indicate estimated marginal (covariate adjusted) means with 95% CI.

As a follow-up to this analysis, we conducted correlations between UPSA-B scores and hours worked per week for the 89 participants who were currently employed. Results of this analysis indicated that higher scores on the UPSA-B were associated with greater number of hours worked per week (r89 = 0.32, p = 0.002). The partial correlation between UPSA-B and hours worked, after adjusting for age, gender, symptoms of psychopathology, and age of onset, was 0.24 (p = 0.03). The correlations for the schizophrenia sample reached statistical significance (r32 = 0.39, p = 0.03), but those for the bipolar disorder sample did not (r57 = 0.19, p = 0.16), although these correlations did not significantly differ from one another (z = 0.95, p = 0.34).

Relationship between UPSA-B and clinical symptoms

Our final analyses examined correlations between symptoms of psychopathology and UPSA-B scores. For these, UPSA-B scores were significantly correlated with both positive (r205 = −0.52, p < 0.001), negative (r205 = −0.63, p < 0.001), and total (r205 = −0.60, p < 0.001) symptoms of psychopathology. However, UPSA-B scores were not significantly correlated with depressive symptoms (r205 = −0.04, p = 0.59). Within the schizophrenia sample, UPSA-B scores were significantly correlated with positive (r116 = −0.46, p < 0.001), negative (r116 = −0.61, p < 0.001), and total (r116 = −0.57, p < 0.001) symptoms of psychopathology, but not depressive symptoms (r116 = −0.05). For the bipolar disorder sample, significant correlations were also observed for positive (r89 = −0.32, p = 0.002), negative (r89 = −0.34, p = 0.001), and total (r89 = −0.30, p = 0.004) symptoms of psychopathology, but not for depressive symptoms (r89 = 0.10, p = 0.35). When comparing correlations by diagnostic group, no significant differences were observed for positive symptoms (z = −1.16, p = 0.25) or depressive symptoms (z = −1.05, p = 0.29). However, the correlation between negative symptoms and UPSA-B scores was significantly stronger in the schizophrenia sample (z = −2.48, p = 0.01), as was the correlation between total symptoms and UPSA-B scores (z = −2.36, p = 0.02).

Discussion

The current study examined the relationship between a brief performance-based measure of functional capacity and several functional outcomes in a diagnostically heterogeneous sample of severely mentally ill participants. In contrast to previous samples, this sample included a wider age range and likely a larger subset of high-functioning, community-dwelling people with bipolar disorder or schizophrenia. Findings indicated that functional capacity, as measured by the UPSA-B, provides a performance-based predictor of real-world indicators of functioning across diagnostic status and symptom severity. These findings are encouraging as they point to the utility of performance-based measures across the age range and among diagnostic groups (i.e., schizophrenia and bipolar disorder). These findings are likely important for both clinical decision making and for using these measures as potential outcomes in treatment studies across these two diagnostic groups.

In comparison to previous samples (13, 14), this sample was restricted to individuals of AJ descent. The group-level performance on the UPSA-B as well as in attainment of functional milestones (e.g., employment) was higher than in previous samples. The inclusion of younger adults also differs from previous studies with the UPSA; however, age did not account for a significant proportion of variance in the context of other variables. Collapsed across diagnostic groups, we found that greater residential independence was associated with higher scores on the UPSA-B regardless of age, diagnosis, and psychopathology. That is, participants who resided independently or semi-independently in the community scored significantly higher on the UPSA-B than less independent participants. These results confirm those reported by Mausbach et al. (13), who found higher scores to be associated with residential independence in middle-aged and older patients with schizophrenia.

Further, whereas Mausbach and colleagues examined only participants who resided independently versus those in assisted-living arrangements (e.g., board and care facilities), the current study broadened the range of residential status categories to include those who were independent or semi-independent, not independent but residing in the community, and residing in a care facility. In regard to diagnostic differences, this study highlighted differences in attainment of functional milestones between bipolar disorder and schizophrenia. However, the current sample demonstrated high performance on a number of outcomes. For example, the rate of independent living in our bipolar disorder sample was high (over 90%), and thus the utility the UPSA-B has in predicting independence as an achievement milestone in that group is limited by the base rate. Nonetheless, the fact that living independently and scoring highly on the UPSA-B converged in the bipolar disorder group, as did UPSA-B scores and SLOF scores, is encouraging, as it suggests the UPSA-B is adequate to identify individuals who are more high-functioning across psychiatric diagnostic group. Further research is encouraged in more severely impaired samples and those demonstrating greater heterogeneity in living status (such as patients with unipolar depression or schizophrenia spectrum conditions). This will help to determine whether their performance on the UPSA-B is indeed significantly lower than higher-functioning and residentially independent individuals.

We also found that UPSA-B scores were significantly correlated with informant reports of everyday functioning, suggesting that the measure accurately predicts other elements of ‘real-world’ functioning. In addition to functional capacity, real-world outcomes such as employment can be affected by a variety of social factors such as disability compensation, motivation, social support, and access to psychosocial services (35). Indeed, in the schizophrenia sample, the UPSA-B was particularly well correlated with informant ratings of impairments in participants’ personal care (r = 0.27), communication (r = 0.30), daily activities (r = 0.63), and work skills (r = 0.43). In the bipolar disorder sample, similar results were found for the daily activities (r = 0.48) and work skills (r = 0.32), suggesting the UPSA-B is useful for assessing these real-world outcomes domains regardless of diagnosis. Some of the SLOF ratings also are aimed at more basic activities of daily living such as toileting and eating, for which many, if not most, participants function at very high levels, thereby truncating the correlation coefficients for both schizophrenia and bipolar disorder samples.

A third finding from the current study was that UPSA-B scores were correlated with measures of educational/academic achievement. Specifically, higher scores on the UPSA-B were significantly associated with higher scores on the WRAT-4, an estimate of premorbid IQ in both our schizophrenia sample (r = 0.40) and our bipolar disorder sample (r = 0.28), accounting for reasonable, but not substantial, amounts of variance in UPSA-B scores. However, correlations between UPSA-B scores and years of education were not significant in our bipolar disorder sample (r = 0.11). This finding is also encouraging because the WRAT-4 is a performance-based measure of current ability, and years of education completed is another milestone variable, which can be affected by environmental factors such as the quality of education across schools. These data suggest that the UPSA-B, like other performance-based measures (i.e., neuropsychological tests), is related to academic ability but not so much that the UPSA-B is simply serving as a proxy for education.

Finally, we found that participants who were employed scored significantly higher on the UPSA-B than those who were not employed. This effect remained when controlling for diagnosis and age but was tempered when including symptoms of psychosis in our model. This finding is consistent with earlier research on the determinants of vocational outcomes, which indicates that cognitive abilities predict the ability to obtain employment, but that symptoms of psychopathology interfere with the ability to sustain employment above and beyond cognitive abilities (36).

Among those who were employed, we found that the UPSA-B was significantly correlated with the number of hours worked per week in our schizophrenia sample (r = 0.39) but not our bipolar disorder sample (r = 0.19). We anticipate that because our bipolar disorder sample was generally higher functioning than our schizophrenia sample, the type of work they were seeking was more professional in nature and more affected by social factors such as availability than the work of those with schizophrenia, a factor that could not be reflected in this analysis. Further, the median number of hours per week worked was 40 among the employed bipolar disorder group, and again, the relatively higher degree of functioning in the bipolar disorder sample indicates the UPSA-B can identify those without functional impairments. We also did not assess the variation in performance that often occurs within employed individuals For example, within groups of working individuals there are some who function well and others less so. Therefore, some may not be candidates for rehabilitation, whereas others might require ‘fine tuning’ of their skill set.

Although there were significant differences between diagnoses in severity of symptoms and functional impairment (worse in schizophrenia), the overall severity of psychopathologic symptoms was a greater predictor of the real-world impairments than was diagnostic grouping. In other words, the same relationships between functional capacity, symptoms, and real-world impairments were evident in bipolar disorder and schizophrenia, with the main difference between these diagnoses evident in the severity along these dimensions. These findings are consistent with recent work on the continuum of psychoses (37) and point toward the utility of more dimensional models versus categorical distinctions between schizophrenia and bipolar disorder.

In sum, our study suggests that the UPSA-B, a brief performance-based measure of functional capacity, is sensitive to impairments in multiple domains of everyday functioning (independent living status, daily activities and work skills, and educational attainment) in both bipolar disorder and in schizophrenia. We found that both functional capacity, as measured by the UPSA-B, and measures of everyday functioning were higher in the bipolar disorder group than in the schizophrenia group. Nevertheless, despite a more restricted range of impairments in the bipolar disorder group, we found that the UPSA-B could have a role as a proxy for multiple domains of functioning in bipolar disorder. We also found that the UPSA-B appears particularly well suited for assessing other functional domains such as personal-care skills and communication skills in patients in schizophrenia relative to those with bipolar disorder, as well as the number of hours patients with schizophrenia work per week. The ability of the UPSA-B to determine functioning in these additional areas among bipolar disorder patients requires further study, which is strongly recommended. Finally, psychiatric rehabilitation targeting functional capacity, such as skills training (38, 39), may be useful for people with bipolar disorder who have functional impairments. Our findings suggest that adaptation of models from schizophrenia would need to take into account those domains of functioning that are not impaired (e.g., independent living skills) to enable tailoring interventions to enhancing everyday functioning in bipolar disorder.

Acknowledgments

Funding for this project was provided by the National Institute of Mental Health (NIMH) through award R01MH079784 (AEP). Additional support was provided by NIMH through awards R01MH078775, K23MH077225, and R01MH078737 (PDH, CAD, and TLP).

Footnotes

PDH has received grant support from AstraZeneca, and in the past year, he has served as a consultant for Eli Lilly & Co., Johnson & Johnson, Merck & Co., Shire Pharma, and Dainippon Sumitomo America. BTM, AEP, CAD, PSW, MHT, JRL, JAM, CB and TLP have no conflicts of interest to report.

References

- 1.Depp C, Davis CE, Mittal D, Patterson TL, Jeste DV. The health related quality of life of middle aged and elderly adults with bipolar disorder. J Clin Psychiatry. 2006;67:215–221. doi: 10.4088/jcp.v67n0207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Dean BB, Gerner D, Gerner RH. A systematic review evaluating health-related quality of life, work impairment, and healthcare costs and utilization in bipolar disorder. Curr Med Res Opin. 2004;20:139–154. doi: 10.1185/030079903125002801. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Simon GE. Social and economic burden of mood disorders. Biol Psychiatry. 2003;54:208–215. doi: 10.1016/s0006-3223(03)00420-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bowie CR, Reichenberg A, Patterson TL, Heaton RK, Harvey PD. Determinants of real-world functioning performance in schizophrenia: correlations with cognition, functional capacity, and symptoms. Am J Psychiatry. 2006;163:418–425. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.163.3.418. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Liberman RP. Assessment of social skills. Schiz Bull. 1982;8:62–83. doi: 10.1093/schbul/8.1.62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Green MF. What are the functional consequences of neurocognitive deficits in schizophrenia? Am J Psychiatry. 1996;153:321–330. doi: 10.1176/ajp.153.3.321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Green MF, Kern RS, Braff DL, Mintz J. Neurocognitive deficits and functional outcome in schizophrenia: are we measuring the “right stuff”? Schiz Bull. 2000;26:119–136. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.schbul.a033430. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Murray C, Lopez A. Global Burden of Disease. Geneva: Harvard University Press; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Revheim N, Medalia A. The independent living scales as a measure of functional outcome for schizophrenia. Psychiatr Serv. 2004;55:1052–1054. doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.55.9.1052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Roy-Byrne P, Dagadakis C, Unutzer J, Ries R. Evidence for limited validity of the revised global assessment of functioning scale. Psychiatr Serv. 1996;47:864–866. doi: 10.1176/ps.47.8.864. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Moore DJ, Palmer BW, Patterson TL, Jeste DV. A review of performance-based measures of everyday functioning. J Psychiatr Res. 2007;41:97–118. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychires.2005.10.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Mausbach BT, Moore R, Bowie C, Cardenas V, Patterson TL. A review of instruments for measuring functional recovery in those diagnosed with psychosis. Schiz Bull. 2009;35:307–318. doi: 10.1093/schbul/sbn152. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Mausbach BT, Harvey PD, Goldman SR, Jeste DV, Patterson TL. Development of a brief scale of everyday functioning in persons with serious mental illness. Schiz Bull. 2007;33:1364–1372. doi: 10.1093/schbul/sbm014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Mausbach BT, Depp CA, Cardenas V, Jeste DV, Patterson TL. Relationship between functional capacity and community responsibility in patients with schizophrenia: differences between independent and assisted living settings. Commun Ment Health J. 2008;44:385–391. doi: 10.1007/s10597-008-9141-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Patterson TL, Goldman S, McKibbin CL, Hughs T, Jeste DV. UCSD Performance-based Skills Assessment: development of a new measure of everyday functioning for severly mentally ill adults. Schiz Bull. 2001;27:235–245. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.schbul.a006870. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Cardenas V, Mausbach BT, Barrio C, Bucardo J, Jeste D, Patterson TL. The relationship between functional capacity and community responsibilities in middle-aged and older Latinos of Mexican origin with chronic psychosis. Schizophr Res. 2008;98:209–216. doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2007.09.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bowie CR, Leung WW, Reichenberg A, et al. Predicting schizophrenia patients’ real-world behavior with specific neuropsychological and functional capacity measures. Biol Psychiatry. 2008;63:505–511. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2007.05.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gildengers AG, Butters MA, Chisholm D, et al. Cognitive functioning and instrumental activities of daily living in late-life bipolar disorder. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2007;15:174–179. doi: 10.1097/JGP.0b013e31802dd367. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Depp CA, Mausbach BT, Eyler LT, et al. Performance-based and subjective measures of functioning in middle-aged and older adults with bipolar disorder. J Nerv Ment Dis. 2009;197:471–475. doi: 10.1097/NMD.0b013e3181ab5c9b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kaplan RM, Anderson JP, Wu AW, Mathews WC, Kozin F, Orenstein D. The Quality of Well-being Scale. Applications in AIDS, cystic fibrosis, and arthritis. Med Care. 1989;27:S27–S43. doi: 10.1097/00005650-198903001-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Huxley N, Baldessarini RJ. Disability and its treatment in bipolar disorder patients. Bipolar Disord. 2007;9:183–196. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-5618.2007.00430.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Fallin MD, Lasseter VK, Wolyniec PS, et al. Genomewide linkage scan for schizophrenia susceptibility loci among Ashkenazi Jewish families shows evidence of linkage on chromosome 10q22. Am J Hum Genet. 2003;73:601–611. doi: 10.1086/378158. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Fallin MD, Lasseter VK, Wolyniec PS, et al. Genomewide linkage scan for bipolar-disorder susceptibility loci among Ashkenazi Jewish families. Am J Hum Genet. 2004;75:204–219. doi: 10.1086/422474. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Fallin MD, Lasseter VK, Avramopoulos D, et al. Bipolar I disorder and schizophrenia: a 440-single-nucleotide polymorphism screen of 64 candidate genes among Ashkenazi Jewish case-parent trios. Am J Hum Genet. 2005;77:918–936. doi: 10.1086/497703. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Chen PL, Avramopoulos D, Lasseter VK, et al. Fine mapping on chromosome 10q22-q23 implicates Neuregulin 3 in schizophrenia. Am J Hum Genet. 2009;84:21–34. doi: 10.1016/j.ajhg.2008.12.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Nurnberger JI, Jr, Blehar MC, Kaufmann CA, et al. Diagnostic interview for genetic studies. Rationale, unique features, and training. NIMH Genetics Initiative. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1994;51:849–859. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1994.03950110009002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Green MF, Nuechterlein KH, Gold JM, et al. Approaching a consensus cognitive battery for clinical trials in schizophrenia: the NIMH-MATRICS conference to select cognitive domains and test criteria. Biol Psychiatry. 2004;56:301–307. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2004.06.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Marder SR, Fenton W. Measurement and Treatment Research to Improve Cognition in Schizophrenia: NIMH MATRICS initiative to support the development of agents for improving cognition in schizophrenia. Schizophr Res. 2004;72:5–9. doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2004.09.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Schneider LC, Struening EL. SLOF: a behavioral rating scale for assessing the mentally ill. Soc Work Res Abstr. 1983;19:9–21. doi: 10.1093/swra/19.3.9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kay SR, Fiszbein A, Opler LA. The Positive And Negative Syndrome Scale (PANSS) for schizophrenia. Schiz Bull. 1987;13:261–276. doi: 10.1093/schbul/13.2.261. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Beck AT, Steer RA, Brown GK. Manual for the Beck Depression Inventory: II. San Antonio: Psychological Corporation; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- 32.McNair DM, Heuchert JWP, Shilony E. Profile of Mood States Bipolar Version. North Tonawanda: Multi-Health Systems Inc; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Depp CA, Cain AE, Palmer BW, et al. Assessment of medication management ability in middle-aged and older adults with bipolar disorder. J Clin Psychopharmacol. 2008;28:225–229. doi: 10.1097/JCP.0b013e318166dfed. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Wilkinson GS, Robertson GJ. Wide Range Achievement Test 4 Professional Manual. Lutz: Psychological Assessment Resources; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Rosenheck R, Leslie D, Keefe R, et al. Barriers to employment for people with schizophrenia. Am J Psychiatry. 2006;163:411–417. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.163.3.411. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.McGurk SR, Mueser KT, Harvey PD, LaPuglia R, Marder J. Cognitive and symptom predictors of work outcomes for clients with schizophrenia in supported employment. Psychiatr Serv. 2003;54:1129–1135. doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.54.8.1129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Craddock N, O’Donovan MC, Owen MJ. The genetics of schizophrenia and bipolar disorder: dissecting psychosis. J Med Genet. 2005;42:193–204. doi: 10.1136/jmg.2005.030718. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Patterson TL, Mausbach BT, McKibbin C, Goldman S, Bucardo J, Jeste DV. Functional Adaptation Skills Training (FAST): A randomized trial of a psychosocial intervention for middle-aged and older patients with chronic psychotic disorders. Schizophr Res. 2006;86:291–299. doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2006.05.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Depp CA, Lebowitz BD, Patterson TL, Lacro JP, Jeste DV. Medication adherence skills training for middle-aged and elderly adults with bipolar disorder: development and pilot study. Bipolar Disord. 2007;9:636–645. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-5618.2007.00397.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]